Introduction

DNA sequence variation in the neuregulin-1 (NRG1) gene has a notable history of association with schizophrenia, particularly in the 5-prime Icelandic haplotype (HapICE) region (Mostaid et al. Reference Mostaid, Lloyd, Liberg, Sundram, Pereira, Pantelis, Karl, Weickert, Everall and Bousman2016) with recent meta-analytic evidence showing renewed support for NRG1 as a candidate gene for schizophrenia (Mostaid et al. Reference Mostaid, Mancuso, Liu, Sundram, Pantelis, Everall and Bousman2017) despite limited support from genome-wide association studies (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2014). Evidence from three independent cohorts suggests that the HapICE region may also harbor single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) capable of identifying high-risk individuals with the greatest likelihood for transition to psychosis (Hall et al. Reference Hall, Whalley, Job, Baig, Mcintosh, Evans, Thomson, Porteous, Cunningham-Owens, Johnstone and Lawrie2006; Keri et al. Reference Keri, Kiss and Kelemen2009; Bousman et al. Reference Bousman, Yung, Pantelis, Ellis, Chavez, Nelson, Lin, Wood, Amminger, Velakoulis, Mcgorry, Everall and Foley2013). Hall et al. (Reference Hall, Whalley, Job, Baig, Mcintosh, Evans, Thomson, Porteous, Cunningham-Owens, Johnstone and Lawrie2006) and Keri et al. (Reference Keri, Kiss and Kelemen2009) reported that the T/T genotype of the HapICE SNP8NRG243177 (rs6994992) SNP was associated with a 100% psychosis transition rate in their two high-risk cohorts; the first a genetic high-risk (e.g. family history of schizophrenia) cohort and the second a clinical high-risk (e.g. sub-clinical positive symptoms) cohort. In contrast, the largest study of NRG1 genotype in a high-risk cohort to date (Bousman et al. Reference Bousman, Yung, Pantelis, Ellis, Chavez, Nelson, Lin, Wood, Amminger, Velakoulis, Mcgorry, Everall and Foley2013) did not replicate this association, but it did identify two other SNPs/alleles (i.e. rs4281084-A and rs12155594-T) within the HapICE region that independently and in combination increased the risk for psychosis transition. Nearly half (46%) of rs4281084-AA genotype carriers and 44% of rs12155594-T allele carriers transitioned to psychosis. When these two SNPs were combined, 71% carrying three or more of the rs4281084-A and rs12155594-T risk alleles transitioned to psychosis. However, unlike the relatively well-characterized SNP8NRG243177 SNP, the neurobiological changes associated with these two NRG1 SNPs have not been described.

Previous investigations have linked multiple variants within the HapICE region with structural brain abnormalities; particularly lateral ventricle volume (Mata et al. Reference Mata, Perez-Iglesias, Roiz-Santianez, Tordesillas-Gutierrez, Gonzalez-Mandly, Vazquez-Barquero and Crespo-Facorro2009; Suarez-Pinilla et al. Reference Suarez-Pinilla, Roiz-Santianez, Mata, Ortiz-Garcia De La Foz, Brambilla, Fananas, Valle-San Roman and Crespo-Facorro2015) and white matter density and integrity (McIntosh et al. Reference Mcintosh, Moorhead, Job, Lymer, Munoz Maniega, Mckirdy, Sussmann, Baig, Bastin, Porteous, Evans, Johnstone, Lawrie and Hall2008; Winterer et al. Reference Winterer, Konrad, Vucurevic, Musso, Stoeter and Dahmen2008; Nickl-Jockschat et al. Reference Nickl-Jockschat, Stocker, Krug, Markov, Huang, Schneider, Habel, Eickhoff, Zerres, Nothen, Treutlein, Rietschel, Shah and Kircher2014). Enlarged lateral ventricular volumes and decreased white matter integrity (i.e. fractional anisotropy, FA) are two of the most consistent structural brain characteristics in schizophrenia (for reviews see: Alba-Ferrara & de Erausquin, Reference Alba-Ferrara and de Erausquin2013; Fusar-Poli et al. Reference Fusar-Poli, Smieskova, Kempton, Ho, Andreasen and Borgwardt2013). Thus, we hypothesized that the rs4281084 and rs12155594 SNPs would be associated with lateral ventricular volume and white matter abnormalities. To test our hypotheses, we used neuroimaging data from a larger cohort of individuals with and without a diagnosis of schizophrenia to determine what relationship these SNPs have with brain structure.

Methods and materials

Participants

Imaging and genetic data were obtained from individuals predominantly of European descent registered in the Australian Schizophrenia Research Bank (ASRB) (Table 1). The ASRB is an Australian resource and storage facility of schizophrenia and healthy control-related research data collected across five Australian states and territories. Full details related to recruitment and assessment procedures have been published elsewhere (Loughland et al. Reference Loughland, Draganic, Mccabe, Richards, Nasir, Allen, Catts, Jablensky, Henskens, Michie, Mowry, Pantelis, Schall, Scott, Tooney and Carr2011). Briefly, cases had a confirmed diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria using the Diagnostic Interview for Psychosis (Castle et al. Reference Castle, Jablensky, Mcgrath, Carr, Morgan, Waterreus, Valuri, Stain, Mcguffin and Farmer2006) and were excluded if they had: a history of organic brain disorder; were younger than 16 or older than 65 years; a serious brain injury resulting in post-traumatic amnesia for more than 24 h; an intelligence quotient <70; movement disorder; current diagnosis of drug or alcohol dependence; or history of electroconvulsive therapy. Healthy controls with a family history of psychosis or bipolar I disorder were also excluded. European ancestry was estimated by comparing the minor allele frequencies (MAFs) for rs4281084 and rs12155594 from the 27 populations included in the 1000 Genomes Project (Phase 3, May 2013 call set) with observed MAFs in the ASRB using a two-sample z-test (online Supplementary Table S1). All procedures were conducted in accord with principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki and approval was obtained from appropriate ethics committees (see online Supplementary Methods).

Table 1. Australian Schizophrenia Research Bank cohort by NRG1 genotypes and combined allelic load

Candidate SNP genotyping, characterization, and linkage disequilibrium

The rs4281084 and rs12155594 SNPs were genotyped using standard procedures described in the online Supplementary Material. Each SNP was mapped using the human genome reference assembly (GRCh37/hg19). Regional linkage disequilibrium (LD) plots for both SNPs were constructed from 1000 Genomes Pilot 1 Northern and Western European (CEU) genotype data using Haploview (Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Fry, Maller and Daly2005). Prior to analysis, the combined allelic load for our two candidate SNPs was calculated using the following formula:

where rs4281084(A) represented the number of A alleles and rs12155594(T) the number of T alleles an individual carried (online Supplementary Table S2). Individuals with a combined allelic load of three or more were pooled to preserve sample size and statistical power.

Lateral ventricular volume analysis

Structural (T1-weighted) images of brain anatomy from 370 (156 controls and 214 cases) individuals were processed using Freesurfer (v.5.0.1) automated neuroanatomical segmentation software. This automatically generated white matter, gray matter, and pial surfaces for each subject that were spherically inflated and registered to the manually delineated Desikan–Kiliany brain atlas (Desikan et al. Reference Desikan, Ségonne, Fischl, Quinn, Dickerson, Blacker, Buckner, Dale, Maguire, Hyman, Albert and Killiany2006). All boundaries were reviewed for accuracy and manually corrected by trained raters to increase the accuracy of the volume and surface estimates. Images were then reprocessed to produce final thickness, surface area, and volume estimates (Fischl et al. Reference Fischl, Salat, Busa, Albert, Dieterich, Haselgrove, van der Kouwe, Killiany, Kennedy, Klaveness, Montillo, Makris, Rosen and Dale2002). Further details on T1 image acquisition, Freesurfer processing, and reliability of estimates can be found in the online supplementary material. General linear models were used to test rs4281084, rs12155594, and their combined allelic load effects on lateral ventricular volume.

Post-hoc we also fitted general linear models accounting for age of onset among all cases using a continuous measure (n = 214) and by restricting the case sample to those with an age of onset ⩽25 years (n = 177). The 25-year onset threshold was selected to reflect the population (i.e. young people at ultra-high risk for psychosis) from which the original association between the rs4281084 and rs12155594 SNPs and psychosis transition were identified (Bousman et al. Reference Bousman, Yung, Pantelis, Ellis, Chavez, Nelson, Lin, Wood, Amminger, Velakoulis, Mcgorry, Everall and Foley2013).

Exploratory gray matter volume, surface area, and thickness analysis

Exploratory general linear models were also constructed to test for gray matter volume, surface area, and thickness throughout the brain. Fixed effects in each model included genotype/allelic load, case–control status, and the interaction between these two factors. Covariates included age, sex, intracranial volume, and scanner location. A Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was used to adjust for the multiple comparisons (288 volumetric, 204 thickness, 204 surface area tests).

Diffusion-weighted imaging analysis

A FA image was generated for 465 (175 controls and 290 cases) individuals with diffusion-weighted imaging data by fitting a diffusion tensor to each brain voxel using least-squares estimation. Details on image normalization, registration, and smoothing are described in the online Supplementary Methods. Cluster-based statistics were used to correct for multiple comparisons across the set of all voxels and thus identify clusters of voxels where the main effect of genotype/allelic load was significant adjusting for age, sex, and scanner location. A corrected p value was computed for each cluster using permutation testing (cluster size option, cluster forming threshold: t > 3.5), as implemented in the FSL Randomize tool. Clusters with a corrected p value <0.05 were considered significant. FA averaged across all voxels associated with a significant cluster was examined post-hoc using a general linear model in which the fixed effects of genotype/allelic load, case–control status, and the interaction between these two factors were examined. We also estimated axial (AD) and radial (RD) diffusivity maps using the eigenvalues associated with the fitted tensor model and extracted AD and RD measures for each cluster showing FA differences by genotype/allelic load. Similar to the structural magnetic resonance imaging analysis, we also conducted post-hoc general linear models to explore potential effects of age of onset. Effect sizes were calculated using the Hedges’ g method (Hedges & Olkin, Reference Hedges and Olkin1985).

Results

Candidate NRG1 SNPs characterization and LD

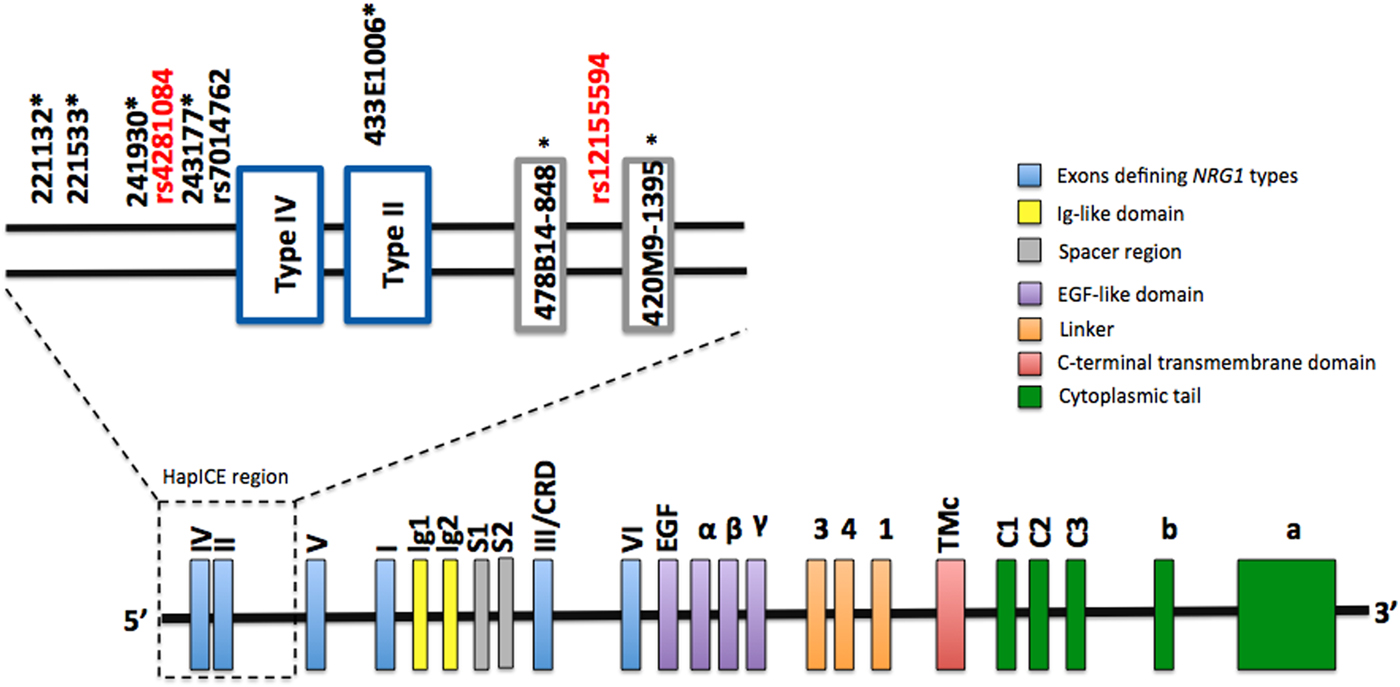

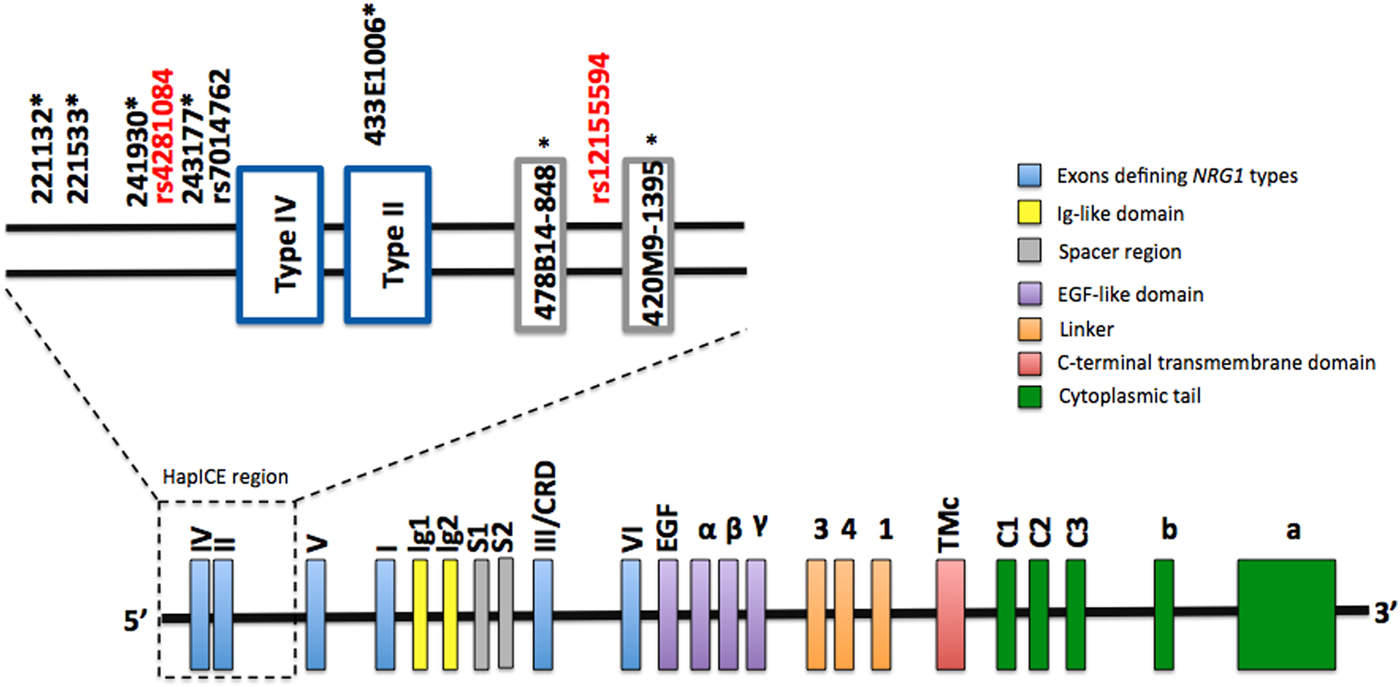

The genomic location of rs4281084 and rs12155594 is shown in Fig. 1. The rs4281084 SNP is located 207 and 294 base pairs upstream of two putative expression quantitative trait loci, SNP8NRG243177 (Law et al. Reference Law, Lipska, Weickert, Hyde, Straub, Hashimoto, Harrison, Kleinman and Weinberger2006) and rs7014762 (Weickert et al. Reference Weickert, Tiwari, Schofield, Mowry and Fullerton2012), respectively. The rs12155594 SNP is located between two microsatellites (478B14-848 and 420M9-1395) that are part of the seven-marker HapICE haplotype and sit between the type II and type V promoters. LD analysis revealed strong LD (D′ > 0.80) between the rs4281084 major (non-risk) allele (G) and four of the five HapICE SNPs but weak LD (D′ < 0.80) between the rs12155594 major (non-risk) allele (C) allele and all five HapICE SNPs. LD between rs4281084 and rs12155594 was also weak (D′ = 0.11) (online Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 1. NRG1 genomic structure and approximate location of rs4281084 and rs12155594 polymorphisms. HapICE markers are denoted by an asterisk (*).

NRG1 SNPs are associated with enlarged lateral ventricles

Neither SNP nor their combined allelic load had a main or interaction effect on lateral ventricle volumes in the full ASRB sample. However, restriction of the case sample to those with an age of onset ⩽25 years revealed an interaction between combined allelic load and case–control status for lateral ventricular volume in the right (F 2,323 = 4.28, p adj = 0.03) but not left (F 2,323 = 2.74, p adj = 0.13) hemisphere. Stratified analysis showed that individuals with schizophrenia (age of onset ⩽25) and a combined allelic load of three or more NRG1 risk alleles had significantly larger right (up to 50%, F 2,170 = 6.83, p adj = 0.01) and left (up to 45%, F 2,170 = 5.21, p adj = 0.05) lateral ventricle volumes compared with those with allelic loads of less than three (Fig. 2). Examination of age of onset as a continuous measure within the case sample did not reveal a significant correlation with left (R 2 = 0.004, p = 0.362) or right (R 2 = 0.002, p = 0.447) lateral ventricular volumes. Furthermore, sex and substance use (e.g. cannabis, alcohol) did not differ between cases with an age of onset ⩽25 and those with a later onset. IQ was slightly lower in the earlier onset group (mean = 104, s.d. = 15) compared with the later onset group (mean = 108, s.d. = 14), but both groups were within the normal range (online Supplementary Table S3).

Fig. 2. Lateral ventricle volume by allelic load and case–control status. Among individuals with schizophrenia, but not controls, an allelic load of three or more was associated with significantly greater left and right lateral ventricle volumes compared with those with an allelic load of 0 (left: p 3+ v. 0 = 0.026, Hedges g = 0.72; right: p 3+ v. 0 = 0.01, g = 0.85) or 1–2 (left: p 3+ v. 1–2 = 0.005, g = 1.40; right: p 3+ v. 1–2 = 0.001, g = 1.55). Marginal mean volume (±s.e.) among schizophrenia subjects (n) with genotype 0 (n = 84), 1–2 (n = 89), and 3+ (n = 4) allelic load were left: 9206±538, 7727±523, and 14 895±2482; right: 8402±503, 6849±489, and 14 580±2322, respectively. Marginal mean volume (±s.e.) among control subjects (n) with genotype 0 (n = 76), 1–2 (n = 75), and 3+ (n = 5) allelic load were left: 7122±499, 7687±503, and 8327±1935; right: 6403±487, 7420±490, and 8908±1885, respectively. Covariates included in marginal mean calculations were age, sex, recruitment site, and intracranial volume.

NRG1 SNPs are not associated with gray matter volumes, thickness, or surface area

Exploratory whole-brain T1-weighted analyses revealed no main or interaction effects after correction for multiple testing for either SNP or their combined allelic load on brain volumes (smallest p adj = 0.28, right superior parietal lobule), thickness (smallest p adj = 0.41, right superior parietal lobule), or surface area (smallest p adj = 0.44, left supramarginal gyrus) (online Supplementary Tables S4–S6).

NRG1 SNPs are associated with decreased FA and increased RD

Analysis of diffusion-weighted images did not detect main or interaction effects for rs4281084 or rs12155594 but did identify a main effect for their combined allelic load on FA in a left middle frontal cluster (max t value = 5.21, p FWE = 0.019; Fig. 3). Cases and controls with an allelic load of three or more had 10% [95% confidence interval (CI) 7–13%] lower FA compared with those with an allelic load of zero. No interaction between combined allelic load and case–control status was detected. Examination of RD and AD measures within this left middle frontal cluster showed that individuals with an allelic load of three or more had 5% (95% CI 3–7%) higher RD but no difference in AD compared with those with an allelic load of zero (Fig. 3). Additional post-hoc analysis excluding cases with an age of onset >25 showed a similar pattern of results but examination of age of onset as a continuous variable among all cases was not associated with FA (R 2 = 0.001, p = 0.854).

Fig. 3. Combined allelic load and fractional anisotropy (FA) in a left middle frontal cluster. Individuals with an allelic load of zero had significantly greater FA compared with those with an allelic load of 1–2 (p 0 v. 1–2 = 1.2 × 10−5, Hedges g = 0.41) or 3+ (p 0 v. 3+ = 0.001, g = 0.88). Individuals with an allelic load of 1–2 and 3+ did not statistically differ (p 1–2 v. 3+ = 0.066, g = 0.57). Covariate-adjusted FA (±s.e.) among individuals (n) with zero (n = 219), 1–2 (n = 233), and 3+ (n = 13) allelic load were 0.35±0.04, 0.34±0.03, and 0.32±0.03, respectively. Post-hoc assessment of radial diffusivity (RD) and axial diffusivity (AD) showed individuals with an allelic load of 3+ had significantly greater RD compared with those with an allelic load of 1–2 (p 3+ v. 1–2 = 0.038, g = 0.49) or zero (p 3+ v. 0 = 0.009, g = 1.11). Individuals with an allelic load of zero and 1–2 did not statistically differ (p 0 v. 1–2 = 0.111, g = 0.26). AD did not statistically differ by allelic load. Covariates were age, sex, and recruitment site. The cluster shown in red contained 121 voxels and the peak voxel coordinates (x, y, z) were −26, 0, 37.

Discussion

We previously identified two NRG1 SNPs (rs4280184 and rs12155594) that independently, and in combination, increased the likelihood of psychosis transition in those at ultra-high risk for psychosis (Bousman et al. Reference Bousman, Yung, Pantelis, Ellis, Chavez, Nelson, Lin, Wood, Amminger, Velakoulis, Mcgorry, Everall and Foley2013). However, the mechanisms by which these SNPs conferred risk for developing psychosis were unclear. From our current findings, we speculate that these NRG1 SNPs may contribute to this risk, in part, via effects on lateral ventricular volume and white matter integrity.

We were particularly interested in testing for associations between our candidate NRG1 risk SNPs and lateral ventricular volume based on meta-analytical evidence suggesting antipsychotic-independent enlargement of lateral ventricles among individuals with first episode and chronic schizophrenia (Fusar-Poli et al. Reference Fusar-Poli, Smieskova, Kempton, Ho, Andreasen and Borgwardt2013) as well as preclinical (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Johnson, Lieberman, Goodchild, Schobel, Lewandowski, Rosoklija, Liu, Gingrich, Small, Moore, Dwork, Talmage and Role2008; Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Zhang, Trembak-Duff, Unterbarnscheidt, Radyushkin, Dibaj, Martins De Souza, Boretius, Brzozka, Steffens, Berning, Teng, Gummert, Tantra, Guest, Willig, Frahm, Hell, Bahn, Rossner, Nave, Ehrenreich, Zhang and Schwab2014) and clinical evidence (Mata et al. Reference Mata, Perez-Iglesias, Roiz-Santianez, Tordesillas-Gutierrez, Gonzalez-Mandly, Vazquez-Barquero and Crespo-Facorro2009; Suarez-Pinilla et al. Reference Suarez-Pinilla, Roiz-Santianez, Mata, Ortiz-Garcia De La Foz, Brambilla, Fananas, Valle-San Roman and Crespo-Facorro2015) suggesting a more direct genetic link of lateral ventricle size to NRG1. We showed a combined allelic load of three or more risk alleles was associated with greater lateral ventricular volume in schizophrenia but not healthy controls. The absence of an effect in controls implies that the increases we observed in ventricular volume cannot be attributed fully to the SNPs we examined and suggests interaction with other biological processes and/or environmental factors. Furthermore, the effect was only observable in those with an age of onset ⩽25. These results complement our previous work that showed youth at ultra-high risk for psychosis with a combined allelic load of three or more were nearly six times more likely to transition to psychosis (Bousman et al. Reference Bousman, Yung, Pantelis, Ellis, Chavez, Nelson, Lin, Wood, Amminger, Velakoulis, Mcgorry, Everall and Foley2013). However, two recent studies in first-episode schizophrenia reported increased lateral ventricular volumes among carriers of the HapICE risk alleles at the rs6994992 (SNP8NRG243177) (Mata et al. Reference Mata, Perez-Iglesias, Roiz-Santianez, Tordesillas-Gutierrez, Gonzalez-Mandly, Vazquez-Barquero and Crespo-Facorro2009) and rs35753505 (SNP8NRG221533) (Suarez-Pinilla et al. Reference Suarez-Pinilla, Roiz-Santianez, Mata, Ortiz-Garcia De La Foz, Brambilla, Fananas, Valle-San Roman and Crespo-Facorro2015) loci – neither of which are in phase with the alleles we identified for psychosis onset risk (rs4281084-A and rs12155594-T, online Supplementary Fig. S1). This discrepancy suggests the association between NRG1 genetic variation and lateral ventricle enlargement may be mediated by other factors. One such factor could be type III NRG1 expression. Previous preclinical work has showed that mice with genetic backgrounds predisposing to either increased (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Zhang, Trembak-Duff, Unterbarnscheidt, Radyushkin, Dibaj, Martins De Souza, Boretius, Brzozka, Steffens, Berning, Teng, Gummert, Tantra, Guest, Willig, Frahm, Hell, Bahn, Rossner, Nave, Ehrenreich, Zhang and Schwab2014) or decreased (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Johnson, Lieberman, Goodchild, Schobel, Lewandowski, Rosoklija, Liu, Gingrich, Small, Moore, Dwork, Talmage and Role2008) type III NRG1 expression had enlarged lateral ventricles. Furthermore, alleles in phase or located in the HapICE risk haplotype have been associated with increased type III expression (Nicodemus et al. Reference Nicodemus, Law, Luna, Vakkalanka, Straub, Kleinman and Weinberger2009; Weickert et al. Reference Weickert, Tiwari, Schofield, Mowry and Fullerton2012), suggesting alleles not in phase, such as our two risk alleles, may be associated with decreased expression. However, neither central nor peripheral type III NRG1 expression levels were available for individuals in our neuroimaging cohort and as such we cannot more clearly link combined allelic load of our two SNPs and type III NRG1 expression levels with lateral ventricular volume. Nonetheless, our results provide additional support for an association between 5-prime NRG1 genetic variation and lateral ventricular volumes and speculate that maintaining a balance of type III NRG1 mRNA could be important for human brain health.

We also determined that the combined allelic load of our two NRG1 candidate SNPs were associated with white matter abnormalities. We used FA given its sensitivity to alterations in fiber density, axonal diameter, and myelination in white matter, the latter of which is regulated, in part, by NRG1 (Taveggia et al. Reference Taveggia, Thaker, Petrylak, Caporaso, Toews, Falls, Einheber and Salzer2008). We showed in our full sample (cases and controls) that as combined allelic load increased, FA decreased and RD increased while AD remained stable in a left middle frontal cluster. This pattern of results is aligned with the notion that FA and RD are under stronger genetic control than AD (Kochunov et al. Reference Kochunov, Glahn, Lancaster, Winkler, Smith, Thompson, Almasy, Duggirala, Fox and Blangero2010) and suggests that individuals with greater allelic loads have a greater degree of dys- or de-myelination in this left middle frontal cluster (Song et al. Reference Song, Sun, Ju, Lin, Cross and Neufeld2003; Song et al. Reference Song, Yoshino, Le, Lin, Sun, Cross and Armstrong2005; Alba-Ferrara & de Erausquin, Reference Alba-Ferrara and de Erausquin2013). This implicated cluster, in part, overlapped with the superior longitudinal fibers from an anterior–posterior orientation and from an inferior–superior orientation, overlapped in part with the corona radiata and cortico-spinal tract. Interestingly, abnormalities along these white matter tracts have been associated with intellectual ability (Goh et al. Reference Goh, Bansal, Xu, Hao, Liu and Peterson2011) as well as emotion and reward processing (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Kober, Carroll, Rounsaville, Pearlson and Potenza2012), which are also intermediate phenotypes impaired in schizophrenia. However, future analyses that incorporate tractography methods will be required to further illuminate the precise location of the identified cluster and its association with these intermediate phenotypes. Notably, our identified cluster also partially overlapped with a recent reported left frontal cluster (x = −30, y = −7, z = 39) of reduced FA in relation to the HapICE SNPs rs35753505 (SNP8NRG221533) (Nickl-Jockschat et al. Reference Nickl-Jockschat, Stocker, Krug, Markov, Huang, Schneider, Habel, Eickhoff, Zerres, Nothen, Treutlein, Rietschel, Shah and Kircher2014), which is 21 kbp upstream of rs4281084. To our knowledge, this is the first independently validated cluster of FA reduction related to NRG1 genetic variation and is aligned with meta-analytic evidence that suggests there are consistent disturbances in frontal lobe white matter integrity schizophrenia (Ellison-Wright & Bullmore, Reference Ellison-Wright and Bullmore2009; Bora et al. Reference Desikan, Ségonne, Fischl, Quinn, Dickerson, Blacker, Buckner, Dale, Maguire, Hyman, Albert and Killiany2011). However, as previously noted, the risk alleles that comprise the combined allelic load are not in phase with the HapICE risk haplotype and as such we have not replicated the direction of the association reported between SNP8NRG221533 and reduced FA (Nickl-Jockschat et al. Reference Nickl-Jockschat, Stocker, Krug, Markov, Huang, Schneider, Habel, Eickhoff, Zerres, Nothen, Treutlein, Rietschel, Shah and Kircher2014) but rather independently identified a cluster that appears to be sensitive to NRG1 genetic variation. In addition, we failed to replicate other clusters of reduced FA previously associated with NRG1 genetic variation including, the medial frontal white matter (Winterer et al. Reference Winterer, Konrad, Vucurevic, Musso, Stoeter and Dahmen2008), anterior limb of the internal capsule (McIntosh et al. Reference Mcintosh, Moorhead, Job, Lymer, Munoz Maniega, Mckirdy, Sussmann, Baig, Bastin, Porteous, Evans, Johnstone, Lawrie and Hall2008), left superior parietal region (Nickl-Jockschat et al. Reference Nickl-Jockschat, Stocker, Krug, Markov, Huang, Schneider, Habel, Eickhoff, Zerres, Nothen, Treutlein, Rietschel, Shah and Kircher2014), and right prefrontal white matter (Nickl-Jockschat et al. Reference Nickl-Jockschat, Stocker, Krug, Markov, Huang, Schneider, Habel, Eickhoff, Zerres, Nothen, Treutlein, Rietschel, Shah and Kircher2014) as well as clusters of elevated FA such as the right perihippocampal region (Nickl-Jockschat et al. Reference Nickl-Jockschat, Stocker, Krug, Markov, Huang, Schneider, Habel, Eickhoff, Zerres, Nothen, Treutlein, Rietschel, Shah and Kircher2014) and the right hemisphere of the cerebellum (Nickl-Jockschat et al. Reference Nickl-Jockschat, Stocker, Krug, Markov, Huang, Schneider, Habel, Eickhoff, Zerres, Nothen, Treutlein, Rietschel, Shah and Kircher2014). However, differences in the SNPs examined, variation in environmental factors, and cohort characteristics (the inclusion of only healthy controls in previous studies) may explain in part the failure to replicate many of these previously identified clusters.

In summary, we found enlargement of the lateral ventricles as well as reduced FA and elevated RD in a left middle frontal cluster among individuals with a combined three or more rs4281084 and rs12155594 ‘risk’ alleles. Collectively, our findings build on a growing body of research supporting the functional importance of genetic variation within the HapICE region of the NRG1 gene and complement our recent findings implicating the rs4281084 and rs12155594 SNPs as markers for psychosis transition (Bousman et al. Reference Bousman, Yung, Pantelis, Ellis, Chavez, Nelson, Lin, Wood, Amminger, Velakoulis, Mcgorry, Everall and Foley2013). Our results further demonstrate the great degree of complexity in the associations between NRG1 genetic variation and intermediate phenotypes and suggest future work will need to determine how best to evaluate this genomic region in a variety of contexts to determine which SNPs may be informative.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002173.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Chief Investigators and ASRB Manager: Carr V, Schall U, Scott R, Jablensky A, Mowry B, Michie P, Catts S, Henskens F, Pantelis C, Loughland C. The authors acknowledge the help of Jason Bridge for ASRB database queries. Data for this study were provided, in part, by the Australian Schizophrenia Research Bank (ASRB), which is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Enabling Grant No. 386500), the Pratt Foundation, Ramsay Health Care, the Viertel Charitable Foundation, and the Schizophrenia Research Institute. CAB was supported by a University of Melbourne Ronald Phillip Griffith Fellowship and Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (NARSAD) Young Investigator Award (20526). VC was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Fellowship (628880) and NARSAD Young Investigator Award (21660). PK was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Swiss Society for Medicine and Biology Scholarships (148384). SJG and JLH were supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health, the Gerber Foundation, the Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation, and The Behavioral and Brain Research Foundation (NARSAD). SS, RI, and AP were supported by One-in-Five Association Incorporated. MSM was supported by a Cooperative Research Centre for Mental Health Top-up Scholarship. CSW is funded by the NSW Ministry of Health, Office of Health and Medical Research. CSW is a recipient of a National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) Principal Research Fellowship (PRF) (#1117079). CP was supported by an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (628386 and 1105825), and a Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (NARSAD) Distinguished Investigator Award. None of the Funding Sources played any role in the study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Declaration of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.