On May 7, 2011, city leaders in Wichita, Kansas, celebrated the official opening of the Nomar International Market at 21st Street and Broadway Avenue. Designed in Spanish Mission Style, the structure and surrounding parking area, with space for local merchants and food trucks, replaced a series of moribund storefronts. Getting the market established had been a long undertaking, a topic of discussion since the city council endorsed the project in 2004. A few years of delays, however, had dampened initial enthusiasm and locals were starting to wonder if it would ever come to fruition or if it was just one more ambitious idea for the area that would end up unraveling. Efforts on the part of the city and community leaders, including the 21st Street Business Association and the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, however, finally made the plans a reality. It was to be a cornerstone of a larger plan to redevelop a business corridor along what had once been a vibrant part of the city that had long since fallen on hard times. Footnote 1

The Nomar International Market was just one facet of a larger plan for 21st Street that came out in 2004. The eastern end of the study zone focused on the city’s African American community as well as areas that once included an oil refinery and the long-gone stockyards. On the western edge, at 21st Street near Amidon Street, the plan envisioned an Asian cultural district centered on the Thai Binh supermarket complex. In the 1990s, Thai Binh had relocated to that area from its founding location on Broadway, a corridor that, like 21st Street, had its own diverse mix of Latino and Asian businesses. Footnote 2

Once the northern end of the city’s industrial district, 21st and Broadway had become part of a growing Latino core. The market’s Latino theme, its other name—The Mercado—as well as the timing of the grand opening to coincide with Cinco de Mayo commemorated this shift. That said, the market was not just a Hispanic institution. Its official name, Nomar International Market, reflected the presence of other populations that also had businesses in the area, most notably the Vietnamese.

The market stood at the intersection of 21st Street and Broadway Avenue, the hub of the city known for its numerous ethnic businesses. A focus of considerable attention and development, 21st Street had been completed with outside consultants, focus groups, public–private partnerships, and community grants. Studying business trends on that busy thoroughfare was intertwined with complicated relations involving city hall and various incentive programs.

Broadway, by contrast, developed in a quieter, perhaps more organic fashion. Out of the spotlight of focus groups and media scrutiny, its businesses emerged, expanded, moved, and closed with far less fanfare and far less public dollar support. As such, it offers perhaps a more representative picture of ethnic entrepreneurship in Wichita.

This study explores the patterns of ethnic, immigrant, and minority entrepreneurship along a stretch of Broadway, from 21st Street to 9th Street, a corridor with a large concentration of Latino and Asian businesses. The goal here is to see what patterns have emerged in recent decades among entrepreneurs of these groups. Over the years, there have been considerable shifts among buildings that might, for example, house a Vietnamese storefront in one decade and a Latino restaurant the next. These trends have raised a number of questions. Was the area equally Latino and Vietnamese? Did the two groups coexist peacefully? Did they organize themselves into distinct sections? Did the boundaries of those sections change? Did the types of businesses change over time? Ultimately, what lessons do these patterns from a medium-sized city in the American heartland suggest about larger conversations the nature of entrepreneurship? The Broadway story, therefore, presents a small microcosm of a truly global conversation that is emerging where immigration, ethnicity, entrepreneurship, and urbanization all meet.

Ethnic Entrepreneurship

Although entrepreneurship is often thought of as a solitary endeavor, businesses along Broadway often represented the efforts of whole families that included spouses, children, in-laws, and other relatives. Moreover, both Asian and Latino businesses functioned within the context of specific immigrant communities. Therefore, a particularly relevant lens to understand entrepreneurship on Broadway in recent decades comes from those who study ethnic, immigrant, and minority entrepreneurs. Works such as Ethnic Entrepreneurs, by Roger Waldinger and colleagues, have shown that entrepreneurship in recent decades has involved significant contributions from groups whose backgrounds differed from the larger society, noting “the revival of small business has been widely accompanied by the infusion of new ethnic owners into the ranks of petty proprietorship.” Footnote 3 Whether Cubans in Miami, Moroccans in Paris, or South Asians in London, varied ethnic groups have become important parts of local business economies, at first developing unique niche markets that catered to specific populations and needs but later transitioning to other areas, even replacing the older native-born business community in several cases.

Other scholars have worked to identify specific typologies of these business owners. Radha Chaganti and Patricia Green, for example, suggest three definitions:

Ethnic Entrepreneurs: “A set of connections and regular patterns of interaction among people sharing common national background or migration experiences.” Footnote 4

Immigrant Entrepreneurs: “Individuals who, as recent arrivals in the country start a business as a means of economic survival. This group may involve a migration network linking migrants, former migrants, and non-migrants with a common origin and destination.” Footnote 5

Minority Entrepreneurs: “Business owners who are not of the majority population. U.S. Federal categories include Black, Hispanic or Latin American, Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, or Alaska native descent. This group occasionally includes women. Footnote 6

Although the categories are straightforward, determining whether a business falls into one or another is less clear. Some ventures are the work specifically of foreign-born migrants, who may or may not be of recognized minority groups. In other cases, a business may include several generations of family members, including those foreign- and native-born, as well as partners and in-laws who may be neither minority nor immigrant. Ivan Light and Roger Waldinger, among other scholars, tend to use the term “ethnic” entrepreneurship as the larger term that includes the other two parameters. Footnote 7

The complicated interplay between ethnic, immigrant, and minority entrepreneurship has been a subject of historical and sociological studies ever since the first works on these topics emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. Among them was Light’s Ethnic Enterprise in America, which appeared in 1972. As the country reeled from a decade of race riots, Light reflected on why certain groups, such as the Chinese and Japanese, developed extensive businesses and entrepreneurial traditions in the United States while African Americans did not. In contrast to a common view that entrepreneurship was the result of certain attributes or practices on the part of individuals, such as tolerance for risk or openness to innovation, Light concluded that for all three groups, small-business creation and practice was shaped by cultural values and the experience of integration (or lack thereof) in the United States. He found, for example, that Chinese and Japanese families created businesses both as a response to discrimination to them and to address the specific needs of their immigrant communities that the larger commercial networks could not address. Moreover, Asian immigrants developed networks and associations to assist with capital and advocacy that African Americans did not have, although Afro-Caribbean immigrants did. Footnote 8

Light was part of a group of scholars that explored, for example, the concept of “middleman minority” groups. These groups seem especially prone to engage in small business. Based in part on the work of sociologists such as Hubert Blalock and Edna Bonacich, Footnote 9 the middleman theory looks at groups whose cultural and ethnic backgrounds are different from that of the larger society. Serving as a buffer between elites and the masses, these groups often consist of small-business owners and function as go-betweens in the economic power structure. Sometimes bearing the brunt of tensions over race and power, these groups are also able to carve out a niche in which they function, and even prosper.

Historical work on ethnic entrepreneurs has often concentrated on the nineteenth and early-twentieth-century stories of certain groups that seemed especially representative of the middleman approach, most notably the Jewish business experience. From peddlers in the cities, to the owners of major downtown stores, to the founders of major companies such as Levi Strauss, Jewish entrepreneurship has been among the best-studied cases. Looking at the topic globally, Bonacich and Modell, for example, observed that almost without exception, these middleman groups were sojourners, migrants whose ancestors came from somewhere else and who maintained distinctive identity from the host society. Footnote 10

Like the Jews, Chinese, and Japanese, other specific populations of middleman groups have developed significant traditions of self-employment, founding businesses, and entrepreneurship. Among these were the Syrians and Lebanese, initially Arab Christians who came to North America as peddlers and, in a story similar to that of the Jews, transitioned into operating small businesses and grocery stores. In Wichita, for example, the Syrian–Lebanese community has been one of the most dramatic examples of middleman-style entrepreneurship. It was a story that began with peddlers who arrived in the late 1800s, transitioned to small-shop ownership in the early twentieth century, and continues in the present day as younger generations venture out to establish their own businesses. The Lebanese have maintained a sense of entrepreneurship as an important cultural value. Although extended family ties have been a central feature of Lebanese business community, they also bore the hallmarks of middleman entrepreneurship in that their customer base was not limited just to Arab Christians. Instead, the Lebanese were able to negotiate Wichita’s complicated racial divisions by serving, for example, both whites and African Americans in what has been considered one of the most segregated cities in the country.

A number of Asian populations also reflect middleman group entrepreneurship dynamics. Light, Waldinger, and others noted how the Chinese and Japanese, for example, have developed patterns of business development similar to those of Jews. Footnote 11 In recent years, Asian Indians, Koreans, and Vietnamese have come to reflect a similar dynamic. Studies of these groups highlight the businesses found in ethnic enclaves like those named Chinatown or Koreatown: those areas where Asian small businesses operate in the midst of the inner city. In some cases, the businesses catered to a specialized market consisting of customers from other established immigrant communities. “Unlike American blacks,” Light observed, “foreign-born peoples had special consumer demands which outside tradesmen were unable to satisfy.” Footnote 12 In other cases, they branched out to operate businesses in the larger society. In some cases, these broader customer bases became the seeds of integration and even assimilation into the larger society. In other instances, they highlighted painful social cleavages based on race and class. The complicated relationships among ethnic and immigrant business owners with African Americans, both as consumers and as employees, has been a topic ever since Light reflected on the Watts race riots in the introduction to his 1972 work. That said, the experiences of groups such as the Vietnamese also challenge what can be an oversimplified middleman model. In places like Wichita, the Vietnamese founded businesses initially to serve the needs of their own immigrant community. Only later did they branch out to serve larger markets. Unlike the Lebanese, however, who served non-Arab clientele from the very beginning, over time the Vietnamese broadened their customer base in part because of the growing popularity of Southeast Asian food in the larger society. Young Vietnamese entrepreneurs have started to venture out of “ethnic” businesses to become part of a larger Wichita business fabric, but whether subsequent generations continue this trend remains to be seen. Footnote 13

Exploring ethnic, immigrant, and minority entrepreneurship in groups outside of distinct middleman groups, however, presents a much greater challenge. African Americans, for example, appear in the early works of Light, Waldinger, and others, but more as a contrast to the small-business story of Asian or Jewish immigrants. Light suggested that African American entrepreneurship was limited in part because African Americans did not have the same cultural networks as did immigrant groups. Footnote 14 Waldinger and Howard Aldrich later took issue with that view, arguing that structural elements in society hampered African American business growth, including lack of capital, restrictive policies, and the presence of government services as the preferred alternative to social advancement for African American men as opposed to business ownership. Footnote 15 Thanks to the recent efforts of scholars such as Robert E. Weems, as well as others such as Juliet E. K. Walker, Kilolo Kijakazi, W. Sherman Rogers, Shennette Garrett-Scott, and David M. Tucker, African American business history is now receiving the attention that such a rich and varied topic deserves, which is one that stands on its own rather than just as a contrast to experiences of other populations. Footnote 16

African Americans are just one example of a population that tends to be discussed in the literature as a labor and working-class story to the exclusion of entrepreneurship. For these groups, entrepreneurs are mentioned in passing, if at all, and when so, are the supporting cast members to a drama in which major labor unions are much bigger actors. The Latino story is a particularly revealing example. Literature on Latin American entrepreneurship looks at topics as diverse as from indigenous craftspeople who make items for the tourist trade, to Jewish and other immigrant business traditions, to the challenges of business owners to function in the face of political and ethnic instabilities. However, discussions of Latinos in the United States in general and Mexican Americans in particular have often overlooked entrepreneurship and concentrated on the larger discussions of worker and labor issues. From community histories and studies of the Bracero Program, to scholarship on the United Farm Workers and on the employment of Mexicans on railroads, and to research on maquiladores (foreign-owned manufacturing plants located in Mexico) and on the North American Free Trade Agreement, the economic story of Mexican Americans has largely been that of workers and labor, not business creation. In Kansas, too, the story of Mexican American and Latino demographics is connected directly to laborers working for the railroads and the meat packing plants. In Wichita, for example, the first Mexican families lived in barrios (Latino neighborhoods) along the sides of the railroads and stockyards where they worked. The Mexican presence on North Broadway began among clusters of converted boxcars and simple dwellings along the track to form communities such as El Huarache (the sandal), located literally between two parallel railroad lines. For this population, entrepreneurship was a later development as younger generations sought to serve the needs of Latinos who became more established in the north part of Wichita. Since the 1980s, however, a new wave of Mexican immigrants has brought a new, larger population, one that patronized a significant number of businesses that grew alongside this expanding base of new immigrants.

Recently, scholars have started to look at how Latino businesses initially developed in the context of an “ethnic enclave” that “emphasized bilingualism and biculturalism, and the small business character of the environment mandated an adherence to a small market strategy reliant on strong local patronage.” Footnote 17 In contrast to the middleman theory, these entrepreneurs came from backgrounds different from the larger society and could function within the limits of an enclave, although they lacked the resources and credit to expand or bridge social and cultural cleavages. David Diaz has argued, for example, that urban policies that encouraged downtown business districts and government-funded urban renewal projects may have benefited the elites of a city, but Latino entrepreneurs had fewer opportunities to participate in those efforts. The exceptions, when successful Latino business districts emerged, often did so with the support of Latino community leaders who could mediate between local businesses and the Anglo-American business and political establishments. The activities that created the first major development of a nationwide Latino market and business climate have struggled since the 1970s, but a new wave of small-scale and flexible businesses have started to emerge that are engaged mainly in community services and with women as a growing presence. In the early twentieth century, an ethnic or immigrant storeowner or grocer might have struggled to maintain specific foodways in the face of limited access to specific products. Today’s proprietor of an Asian grocery or Latino supermercado (supermarket) can use global networks to make what were once exotic and rare foodstuffs commonplace in locations far distant from the country of origin. Footnote 18

These trends have not been limited to the big populations in coastal cities such as New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, where groups often had the numbers to create self-contained enclaves. Rowena Olegario’s work on Jewish entrepreneurship, for example, noted that German Jews were even more likely than German Gentiles to settle in the West, with some nine hundred small towns in the western United States supporting Jewish businesses in the late nineteenth century. Even locales once seen as the embodiment of “white bread America” are now seeing significant changes as immigration and migration bring in significant cultural shifts. In several areas of the Great Plains, for example, Latinos and Asians are coming to represent the majority population. Once “meat and potatoes” centers now sport abundant Mexican restaurants while futbol is challenging football as the high school sport of choice. Footnote 19

Regarding larger scholarship on ethnic entrepreneurs, therefore, this study of ethnic entrepreneurship along Broadway Avenue in Wichita, Kansas, moves the discussion past the middleman theory. It allows for a comparison of businesses for two different populations. Asians, specifically Vietnamese and Asian Indians, correspond more to the classic middleman ethnic entrepreneur group. The Latino community, by contrast, is a much more numerous group, with a business presence that ranges from mid-century restaurants to current services to meet the needs of a new immigrant population. Although a single window about two miles long, Broadway provides insights for a local history as well as a vibrant and a growing literature.

Methodology

For the businesses being discussed here, the concept of “ethnic entrepreneurship” is perhaps most relevant because it identifies a specific segment of the business community tied to particular groups without having to make incomplete decisions from data that may not always determine minority or immigration status of the founders. This study uses three techniques to understand the story. The first is historical scholarship based on newspapers, census data, city directories, interviews, and other sources. This provides background and context, as well as highlights individual stories. The primary objective of this research, however, was to create a database of Asian and Latino businesses along Broadway. One of the main concentrations has been between 21st Street and 9th Street, so that segment was selected as the most relevant portion to study, particularly because it contains both Asian and Latino populations, making it especially suitable to explore the relations between these two groups. To make the sample manageable, marking changes at ten-year intervals seemed to provide appropriate benchmarks. City directories from 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2015 provided the basic information. Care had to be taken to make sure the addresses had not changed and to handle the fact that several businesses might be located in the same building.

The next step involved filtering out which of those businesses was Latino or Asian owned. Business names were a starting point, but they could be misleading. A café with a Spanish name or that catered to a Latino immigrant clientele could have an owner of German extraction. A particularly useful resource was the Kansas Business Center’s Business Entity Search Station, which provided information on incorporation specifics, the names of owners, and other relevant information. Searching for mentions of businesses in The Wichita Eagle and the Wichita Business Journal, as well as other sources, such as obituaries and crime reports, also provided valuable clues about business ownership. Periodic visits to the area helped clarify details and provided additional insights. For example, during the fifteen months it took to compile the data, one business at Broadway and 11th Street went through several different incarnations, from a diner with a long-time legacy to one that was short-lived, to a Mexican restaurant, to being vacant. It was a reminder that even detailed samples are snapshots of more complicated dynamics. The resulting database identified 101 Latino and Asian businesses for mapping and analysis.

The information from this database was then subjected to two additional techniques. The first was mapping using a geographical information system (GIS), a powerful tool now available to faculty across Wichita State University, thanks to an institution-wide site license. The key figure in helping the university obtain that license was David Hughes, in the Anthropology department. Hughes teaches GIS courses and provided the maps included in this article. The maps provide a visual depiction of the trends discussed, and show how Latino and Asian business concentrations have changed over time and how they relate to larger demographic patterns across the city. As Waldinger, McEvoy, and Aldrich have noted, ethnic entrepreneurship often functions in a spatial relationship to a given population and to the larger community. “Neighborhoods may be the starting point of ethnic business and remain an important magnet for ethnically oriented services and customers,” they suggest. However, “expansion beyond the neighborhood or the ethnic market is critical if businesses are to grow.” Footnote 20 Mapping Latino and Asian establishments shows the growth of both sectors, whether one sector grew and the other shrank, as well as the degree to which they mixed or remained separate. Doing so also illustrates the degree to which these businesses are reflections of ethnic neighborhoods and how these populations may have shifted. Mapping works as markers of the growth and migration of these two distinct populations in north Wichita. It also shows the overall demographics of the city and adds an additional dimension; namely, the extent to which entrepreneurs from these two populations have made the shift that Waldinger, McEvoy, and Aldrich have discussed: the transition from serving a limited ethnic customer base concentrated in a specific part of the city to a community-wide clientele. Footnote 21

The other tool involved the use of the National Establishment Times-Series (NETS) database, a time-series data set that uses Duns & Bradstreet’s annual cross-sectional files as its base. The Duns & Bradstreet cross-sectional files, which start in 1990, contain sales, employment, geographic, and industry sector data for each individual establishment within the state each year. Dun & Bradstreet attempts to contact every firm annually, as well as uses information from newspapers, public utilities, government databases, and court filings; it also uses advanced estimation techniques to fill in any missing data.

The NETS database, with very few exceptions, contains the full universe of business establishments in Kansas. Since it is a time series, it captures the changes in business dynamics over the twenty-three-year period of data, from 1990 to 2012, for each of these establishments, including both establishment start and (as appropriate) closing dates. It also captures any establishment relocation and sectoral shifts by establishment. Therefore, historical research reveals the larger story, mapping illustrates the spatial relationship of entrepreneurship, and the NETS database highlights the nature of the entrepreneurship. Through the use of these three techniques—data analysis, mapping, and historical research—a picture of ethnic entrepreneurship along one thoroughfare in Wichita, Kansas, began to emerge.

Broadway Avenue

In the 1930s, the route originally platted as Lawrence Avenue became Broadway Avenue. It was also Highway 81, a section of the great Meridian Highway that supporters once hoped would link Canada with Patagonia. The great two-continent thoroughfare never materialized, but efforts did create an important corridor in Kansas. From the 1930s through the 1950s, motorists traveling south on Broadway would have encountered the tourist court (and roadhouse) of Rock Court before arriving at the packing plants, stockyards, and grain elevators on the city’s northern edge. Footnote 22 Broadway had elegant Victorian homes that in a prior century had been among the most prestigious addresses in the city. At Central Avenue, drivers could have turned onto the main route east to leave town or continue past the Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception into the heart of the downtown area, past the Orpheum and Miller theaters, and the main business district intersection of Douglas Avenue and Kellogg Avenue. After crossing Kellogg, not yet the east–west artery through the city that it later became, motorists would have continued south on Broadway through more residential and industrial areas. Crossing the Arkansas River on the concrete spans of the John Mack Bridge, Broadway/U.S. 81 ran on south of town, down toward the Oklahoma border.

Broadway was both an important thoroughfare and a local artery. At various points, it housed neighborhood businesses. Near its intersection with 21st Street, for example, stood several businesses that served the people who worked in the nearby packinghouses, stockyards, grain elevators, and refinery. At the southeast corner of 21st Street and Broadway, for example, stood a two-story, wedge-shaped building, known locally as the Flatiron Building, which housed the Stockyards Bank. Nearby were grocery stores, a local lodge of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, and a post office, all serving the residents of North Wichita. Given Broadway’s ties to automobile travel, it was fitting that many of the businesses along its route catered to cars or the traveler passing through. A 1956 city directory indicated that between 9th Street and 21st Street, Broadway contained eight service stations, eighteen car lots and automotive supply businesses, and four motels, most of these being north of 13th Street. Motels were initially small mom-and-pop ventures such as the Uptown Motel, but in late 1963, the substantial Holiday Inn Midtown complex opened. Cafés and restaurants were common as well, catering to both local patrons and travelers. Examples range from modest grills connected to the motels to local icons such as Doc’s Steakhouse, which opened in 1952. Footnote 23

By the late 1960s and 1970s, however, the character of Broadway changed. The stockyards and packinghouses closed as the meat processing industry relocated near the feedlots of western Kansas. Neighborhoods aged and the stores and other businesses that once served working-class families closed. The postwar craze for supper clubs passed and venerable restaurants such as Abe’s Steak House and Ken’s Steak House closed. Along with an ageing customer base, the proprietors of local businesses along Broadway also aged, facing challenges in passing their ventures onto the next generation. Sometimes they did, as when “Doc” Husted sold his steak house to his neighbors, the Scotts, who then passed it on to their son, who sold it to his nephew. By the 2000s, however, the Scott family found it difficult to get the financing to update the restaurant for a new generation; they were ready to move on, so they closed the establishment in 2014. All along Broadway, business families that thrived in the 1950s found themselves struggling with aging infrastructures and changing consumer patterns. Footnote 24

For the Broadway business corridor, the most significant initial change was the development of the interstate highway system that included I-135. Known as the Canal Route because it followed the drainage canal that had once been Chisholm Creek, I-135 carried cars and trucks on an elevated highway that went through the center of the city. By 1974 the route transformed life in Wichita. For drivers, going north and south through Wichita had never been easier. For residents, however, there were challenges. For African Americans, the Canal Route divided the heart of the city’s predominantly black neighborhoods that ran from Broadway to Hillside Avenue and beyond. For motorist-based businesses along Broadway, meanwhile, I-135 was a death sentence. Almost immediately, the gas stations, motels, and cafés that once catered to local families, traveling salesmen, and truckers passing through started closing. In their place came modest shops. By 1980 Broadway’s real estate had declined in value, property values were low, and rents were cheap. For some, such as the residents who came to make up the Historic Midtown Citizens Association, it was a call to arms to preserve historic buildings and maintain infrastructure and property values. That same dynamic made the street attractive to new businesses that catered to a very different customer base. The strip malls that appeared on Broadway in the 1980s were, to the Midtown Citizens Association, a cause for alarm and the symbol of an area in decline. For other populations, especially those from the Asian and Latino communities, these same facilities were a new start, a chance to establish a presence in the city. Footnote 25

Hispanics and Latinos in Wichita

Although it may appear as if we use Hispanic and Latino interchangeably, the terms refer to distinct yet overlapping populations. Hispanic refers to populations including Mexicans, Spaniards, Filipinos, and other people of Spanish-speaking groups who live in the United States. Latino describes people with a heritage from Latin America and includes, for example, Mayan, Quechua, and other Native American peoples. Given that the project did not distinguish between Spaniard-run businesses, which would be Hispanic but not Latino, and ones run by Mayan-speaking families, which would be Latino but not Hispanic, the populations discussed here are, to a great extent, part of both groups.

Latinos have been part of Wichita’s story since the cattle drive years of the 1870s, although the first major community did not develop until the early 1900s, when the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway brought in Mexican workers. These workers brought their families, and by the 1910s a string of barrios extended along the Santa Fe tracks. These families were spread across a series of barrios and communities, including, El Norte (the North) on the northwest of 21st Street and Broadway and El Huarache to the southeast. Most Mexican families were laborers, working for the railroad or the meatpacking plants along 21st Street.

In the decades after World War II, some of the children of these families found jobs in the same plants in which their parents worked. Others ventured out on their own, such as Jesse Cornejo, the son of immigrants who first worked the sugar beet fields of western Kansas and then came to work for the railroad in Wellington. Jesse, however, went into construction, eventually starting his own business in 1952. At first, his business was in hauling and demolition, but, by the 1970s and 1980s, Cornejo had been able to tap into a number of Small Business Administration programs and gained contracts for construction projects across the area. Footnote 26

North Market, or Nomar, became a critical hub of the Latino community. By the 1950s and 1960s, a handful of Latino-run businesses began to emerge, particularly restaurants, including Tony Oropresa’s El Patio Restaurant and Anthony’s Fine Foods. Some of this reflected the role of women entrepreneurs transitioning from cooking at home or at community events into restaurant work. Many, if not most, Mexican restaurants along Broadway featured women as co-owners, co-founders, patrons, or key figures in operations, as in the story of Connie’s Mexico Café, located at 2227 North Broadway, north of 21st Street. Its story began with Rafael and Connie Lopez. Rafael had come to Wichita after the Korean conflict, where he served as a barber at McConnell Air Force Base. Connie was famous for her cooking, especially at functions at St. Margaret Mary Catholic Church. In time, her food became so popular that in 1963 she opened one of the best-known restaurants. Connie’s Mexico Café was located at the site of the former bar called Chata’s, and it was next door to El Patio. When El Patio moved in the 1970s, the Lopezes acquired the entire building; their restaurant remains the oldest surviving family-owned Mexican restaurant in Kansas. Footnote 27

Connie’s was not the only Mexican restaurant to emerge in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1976 Don and Marta Norton acquired an existing Mexican restaurant at 1451 North Broadway, and renamed it La Chinita. Although Don was not Latino, his wife was, and La Chinita became another example of Latino entrepreneurship along Broadway. Footnote 28 Meanwhile, Mexican immigrant Felipe Lujano formed his own restaurant, Felipe’s, on West Central, employing other family members who often worked in the restaurant. One brother opened a second Felipe’s on the east side, and a nephew opened one on the city’s southeast edge. Another nephew, Enrique Cortez grew up in the business, worked for a time at Excel meatpacking, and then opened his own restaurant at the former Ken’s Steak House on 29th Street, just west of Broadway. In 1985 Felipe and his wife, Mary, renamed the venture the Cortez Mexican Restaurant. These restaurants, among others, have become well known, and are popular among Anglo and Latino patrons alike. Footnote 29

The Lujanos were from Jalisco, in central Mexico, indicative of a changing and diverse Mexican population in Wichita. Early twentieth-century families tended to be norteno, from northern Mexico. While norteno immigration continued from Durango, Chihuahua, and Nuevo Leon, there were also growing numbers of migrants from central Mexico such as Jalisco, Michoacan, and Aguascallientes. Together, they represented a significant growth in the Latino population, especially after 1970. From 1990 to 2000, for example, the Mexican community in Wichita increased 124 percent, from around 16,000 to 36,000 people. By 2010 Hispanics and/or Latinos comprised 15 percent of the population. Many came to work in the aircraft plants or other industries. Others, however, came with a more entrepreneurial spirit. The number of Latino-owned businesses in Sedgwick County more than doubled between 1992 and 1997, from 360 to 791. Most of these businesses were in the areas of services, retail, transportation, and communications. Footnote 30

With more than a quarter of Wichita’s Hispanic population living in the North Midtown areas along 21st Street and Broadway, that area began to serve as a key market and customer base for Hispanic businesses, with 21st Street, even more than Broadway, as the main business artery. A local Spanish-language newspaper, Mi Jente Hoy (My People Today), grew from an initial circulation of 5,000 in 2001 to 35,000 by 2003. In 2003 Wichita’s Hispanic community gained even more visibility when Cuban-born Carlos Mayans was elected mayor. The business side of the community had gained a voice in 2002 with the creation of a local branch of the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, which operated out of the Midtown Community Center at 1150 North Broadway, the site of a former Safeway food market. One major effort of the organization, guided by Charles Rivera as its president, was to help revitalize the North Broadway area, clean up the vicinity, provide security, and establish the area with a distinctive Latin American identity. Another effort was to help business owners, themselves often immigrants, navigate an often confusing set of rules and regulations that guide American business practices, in contrast to the more informal approach found back in Mexico.

Waldinger, McEvoy, and Aldrich refer to these figures as “adjustment entrepreneurs,” whose main purpose is to help immigrants adapt to life in a new society. Footnote 31 The lack of business literacy has been a major challenge for Latino entrepreneurship, with individuals wary of taking advantage of official programs like those of the Small Business Administration. Footnote 32

Several of these businesses were restaurants. Unlike the eateries of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, however, these establishments went beyond the standard tacos and fried foods familiar to Anglo patrons, Footnote 33 but instead offered foods more targeted to Mexican palates, such as nopales (cactus) or menudo (tripe soup). Dining areas resonated with televised futbol games.

Other businesses also catered to the needs of Mexican immigrant patronage. Among them were markets that sold products from Mexico, clothing stores such as La Favorita, venues that provided dresses and other items for quinceañeras (coming-of-age celebrations that take place when a girl turns fifteen), clubs related to regional or state associations in Mexico, and places to wire money back to family. Transactions took place in Spanish, and in the Mexican preference of doing business with cash rather than credit. Meanwhile, rules and issues related to immigration status governed nuances of everyday life.

Several businesses sold imported foodstuffs and specialized grocery items. One of the oldest was Del Pueblo, formed in 1989 at 2437 North Broadway. During the 1990s and 2000s, other Latino grocery stores emerged. Some were on far North Broadway. Others were on the city’s south side, near the aircraft workers’ neighborhood of Planeview. Initially, small enterprises scattered wherever there were pockets of Latino customers; some stores, as they grew, relocated to a corridor along North Broadway. One was Super del Centro, originally established at 2128 North Broadway, adjacent to the Flatiron Building at 21st Street. Within a few years, however, it moved further south to a facility at Broadway and 17th Street. By the 2000s and 2010s, North Broadway was gaining a reputation as a place for Latino stores, especially grocery stores that attracted immigrants who wanted foods from their home areas, as well as Anglo “foodies” looking for unique ingredients not found in more mainstream stores. Footnote 34

Asians in Wichita

From the city’s earliest days, there had been small numbers of Asian immigrants. Most were Chinese, including men such as Wayne Wong, a “paper son” who bypassed anti-Chinese immigration laws by taking on the persona of his adopted family. The paper son was a practice that emerged after the 1906 earthquake and fire destroyed immigration and citizenship records in San Francisco. The paper son concept was an arrangement to get around the restrictions of the Chinese Exclusion Act: an American citizen of Chinese background sponsored an immigrant by claiming, falsely, that the person was a relative. Although not all of the Chinese in Wichita were paper sons, in the middle of the twentieth century, the city’s Asian population remained Chinese and consisted of only a handful of families or bachelors. They were entrepreneurial in nature, operating, for example, a number of small businesses such as the Fairland Café, the Holly Café, and the Pan-American Café. Footnote 35

In the 1970s, unrest in Southeast Asia dramatically changed the Asian population of Wichita. Soldiers connected to McConnell Air Force Base and who served in Southeast Asia resulted in war brides and families relocating to the area. Even more significant was the fact that Wichita became a refugee city. The first major arrival of Vietnamese into the United States came with the fall of Saigon in 1975, resulting in more than 128,000 Vietnamese fleeing the communist takeover of the south. Many were military figures, government officials, and professionals, as well as those with ties to the French and U.S. presence in the region. Most went to California, although refugee aid networks did find opportunities for 1,902 refugees to come to Kansas that year, mainly to work in the meatpacking industries in southeast Kansas. By the end of 1975, approximately 150 Vietnamese had arrived in Wichita, and January 1976 saw the first community celebration of Tet (the Vietnamese lunar New Year). The emergence of the communist Khmer Rouge in Cambodia and Pathet Lao in Laos resulted in migration from those countries as well. The next major influx came in 1979 and 1980, when the United Nations’ Orderly Departure program and the United States’ 1980 Refugee Act created a system for refugees to leave Southeast Asia to come to the United States. Catholic Charities, Lutheran Social Services, Southern Baptist mission efforts, and other religious and civic efforts worked to settle a new wave of Southeast Asians to Wichita. By the early 1980s, estimates for the number of “Indochinese,” which included Laotians, Vietnamese, Cambodians, and ethnic Chinese from Southeast Asia, stood at about 2,100. During the 1980s and 1990s, this initial core formed the basis of chain migration from Vietnam as well as from other cities in the United States. By 1990, there were an estimated 3,600 Vietnamese in Wichita. By the early 2000s, the Vietnamese community in Wichita stood at about 7,300, with a total Asian population of about 10,000. Footnote 36

Initially, the Vietnamese settled wherever the religious refugee aid organizations could find them available housing, often in older, less prosperous parts of the city where the rents were cheaper. One area was Planeview, in South Wichita. Another was near or along Broadway. For a time, refugees could work in the meatpacking plants; that is, before those businesses closed and relocated operations to southwest Kansas. Those interested in providing services to immigrants from Southeast Asia established facilities nearby. One was an effort in 1983 by the local Asian Association, Wichita Social and Rehabilitation Services, and English language teachers to create a social service and education center, the Wichita Indochinese Center, located at 121 East 21st Street. During the 1980s, human services organizations helping refugee families started to give way to groups from the community itself, including the Vietnamese Mutual Association, which offered training in aircraft metal work; a Vietnamese student group at Wichita State University; the former South Vietnamese Military Association, the Vietnamese Community Association; and Buddhist and Catholic groups. Footnote 37

By the 1980s and 1990s, various Southeast Asian groups started to form clusters, with Lao community organizations and businesses concentrated along South Hillside Avenue, and Vietnamese ones along North Broadway. Although many Southeast Asians worked in the aircraft plants and other industries, a significant number were engaged in entrepreneurship. In 2007 Hispanics/Latinos were approaching 15 percent of the population and 2.7 percent of businesses were Hispanic/Latino owned. Asians, by contrast, made up nearly 4.8 percent of the population, and Asian-owned businesses represented 3.8 percent of total firms. This data shows that the Asian population was less than a third of the Latino/Hispanic population but it comprised a larger share of the city’s business owners.

Anh Tran, a professor of Education at Wichita State University, did her dissertation on the Vietnamese of Wichita. She suggests that several factors were at play. Some refugees, especially from the first wave, were professionals back in Vietnam and worked to reestablish those or similar careers in the United States. For others, the loss of a career or other status as a result of the communist takeover of South Vietnam was a major source of shame and, “thus, self employment is the peace of mind for those who lost social status.” Footnote 38 Moreover, many immigrants lacked the technical skills or language skills to find jobs in the city at large.

[By contrast,] under the family-owned status, the owners have flexibility on their decisions. Many of them have used one business building for as many odd jobs as they wish. For example, an owner of one small size Vietnamese grocery store can add an income tax service provided by his son to earn additional income for the family during the tax season. The owner can also have assembly orders from an apparel company done right in his building whenever there is a slow flow of customers to his grocery business. Footnote 39

Entrepreneurship gave families a chance to pool their efforts, perhaps in a way that did not require strong English skills. Business loans from mutual benefit associations provided the capital. Footnote 40

Tran’s dissertation noted that, as of 2002, the community supported six physicians, five of whom owned their own practices; five insurance agencies; six supermarkets; two real estate offices; four jewelry stores; five legal assistance service providers; one liquor store; eight beauty salons; five video shops; one bookstore; one flower shop; one publishing/printing business; six alteration shops; eight restaurants; and one store that sold traditional herbal medicines. Footnote 41 To a large extent, these businesses served a Southeast Asian clientele. They either provided specialty services and products for the community or were adjustment entrepreneurs for immigrant families.

An example was that of the Thai Binh Supermarket, incorporated by Nuot “Jimmy” Van Nguyen and his wife, Ly Ngoc Thi Nguyen. Jimmy had come from Vietnam to Odessa, Texas. When an accident at a machine shop caused the amputation of his arm, Jimmy relocated to Wichita, Kansas, where a friend who ran the Oriental Wholesale on Broadway got him started in the grocery business. Although Oriental went bankrupt soon after Nguyen arrived, the Nguyens persisted, founding Thai Binh Supermarket, at 2128 North Broadway. By 1995 their store had grown to a seven-thousand-square-foot space, and the Nguyens acquired the Riverbend Shopping Center, at 21st Street and Broadway, establishing an expanded Thai Binh at the long-closed Ardan Jewelry Store. The center had already undergone a number of changes, having once housed a Mr. Steak that became an Indian restaurant. Similar to Mexican entrepreneurship, the Vietnamese launched a number of restaurants, including the Saigon Café at 1103 North Broadway in 1996. In more recent years, Broadway, from 9th Street to 17th Street, has been the location of other Vietnamese restaurants and businesses. Among the more recent businesses have been nail salons, which have come to represent an especially visible part of Vietnamese women entrepreneurship. Footnote 42

Another Asian population, from the Indian subcontinent, had a markedly different story and was tied especially to Wichita State University rather than a refugee settlement. In the late 1960s, a handful of Asian Indians families come to Wichita. Several individuals, such as Prem Bajaj, Ph.D., arrived to teach at Wichita State University. Others were doctors and physicians who arrived in the 1970s, as Wichita was developing a regional medical hub with several hospitals, the Wichita Clinic, and a University of Kansas Medical Center. By the 1980s, there were several hundred Asian Indians in Wichita, which was enough to form organizations such as the Indian Association of Greater Wichita, now the Cultural Association of India; support student organizations at Wichita State; and rent out the Century II Civic Center to host Diwali events. In 2002 the Hindu Indian community celebrated the opening of its temple in East Wichita. Muslim Indians, Bangladeshis, and Pakistanis, meanwhile, were active in Wichita’s Islamic Center, founded in 1976, and the Masjid al Noor next to Wichita State University. Footnote 43

The Asian Indian presence on Broadway consisted primarily of families that operated motels. Paralleling national trends, those motels owners tended to be Gujaratis in background and Jain in religion. These families, with family names such as Bhakta and Patel, represented a South Asian presence in Wichita’s entrepreneurship scene that was distinct from the professional, engineering, and medical families tied to Wichita State. Among them was, for example, Someshver “Sam” Bhakta, of Bhakta’s Rising Sun Inc., formed in 1997 and located at 1421 North Broadway. Footnote 44

Analysis

Asian and Latino entrepreneurship along Broadway has grown considerably since the 1980s. Understanding the broader patterns beyond individual stories and anecdotes, however, required using two different techniques. As noted above, maps reveal where clusters of Latino and Asian businesses existed over time, and databases allow for a deeper drilling down of specific issues. A powerful one is the NETS database, with data from 1990 to 2012 and to which the Center for Economic Development and Business Research at Wichita State University has access.

There were challenges in preparing a single data set consistent with the three sources we used in this article: historical scholarship, GIS, and the NETS database. After a few attempts, the best approach was to use latitude and longitude in both the GIS and the NETS database. This provided the most accurate results and the maximum number of matches. From a data set of 110 records, nine records were eliminated because of inconsistencies. The net number of businesses used in both GIS and NETS analysis was 101, of which 66 were Asian and 35 were Latino.

The businesses in the decades from the 1970s through the 2010s are plotted in Map 1. Diamond shapes refer to Asian businesses and triangle shapes indicate Latino ones. For ease of understanding, the decision was made to base the information on addresses so that when multiple businesses existed for the same address, only one mark was created. It also meant that in some cases, there were locations that had both Latino and Asian indicators, usually referring to strip malls that had more than one storefront.

Map 1 Ethnic businesses, by decade (1970s–2010s), on North Broadway, Wichita, Kansas.

Note: All maps in this article consist of background map courtesy of ESRI, which cites Service Layer Credits: Delorme, MapmyIndia, ©OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS user community. Business information and addresses by Jay Price from research in the city directories of Wichita, Kansas. Other information was derived from U.S. Census data. Business locations were plotted with the aid of an address locator built and maintained by the Sedgwick County GIS Department. Final cartography and assembly by David Hughes at Wichita State University.

Several trends appear in this map. In the 1970s, there was just one ethnic business listed, La Chinita, which is the triangle in the center of the each map. For Latino businesses, growth was modest at first, with only a handful of new additions by the 1990s. The main growth took place after 2000, and has been especially striking since 2010. In comparison, Asian businesses grew steadily from the 1980s to the 2010s.

Urban demographic patterns may not be readily apparent in Map 1, yet they are significant. For the Vietnamese of Wichita, Broadway is the main commercial corridor, with few establishments to the east or west. By contrast, Wichita’s Latino population is especially concentrated to the west of Broadway, extending now across the Arkansas River to Meridian, Kansas. As such, the main commercial corridor for the neighborhood is 21st Street, on which are several restaurants, clothing stores, and, most recently, the Nomar International Market, which tends to be Latino in nature. Broadway, therefore, is a secondary corridor, and is the eastern edge of Latino commercial activity rather than its hub. The dominance of 21st Street, located on the upper edge of each decade’s map, explains the cluster of triangles at the top of the map for the 2010s.

The other cluster of triangles, located just south of 17th Street, currently includes the Super del Centro at its core. In the 1980s and 1990s, that area was the location of several Asian establishments and included an Asian market, a used car lot, and a noodle shop. By the 2000s, more Asian businesses developed, some in strip malls located between 13th Street and 17th Street, with jewelry stores and nail salons nearby. Another pocket was between 9th Street and 13th Street, consisting especially of restaurants such as Saigon and Little Saigon, and was close to a string of motels as well as St. Francis Hospital. By the 2010s, the stretch around 17th Street had shifted from Asian to Latino. Asian businesses were more concentrated around 13th Street; the lower Broadway restaurant corridor remained, even if the establishments had changed names.

While the maps show changing locations of Asian and Latino business areas, the NETS material revealed more detailed information about the types of businesses located along Broadway. Among the statistics that were revealing were the years a business opened and closed (if it went out of business), type of industry, average number of employees, and average sales.

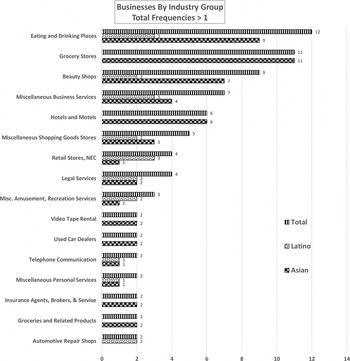

One area of analysis involved the type of business each ethnicity pursued. Figure 1 shows some sharp differences, but it shows even more similarities.

Figure 1 Business by industry group, total frequencies, >1.

Note: All figures in this article were based on business information and addresses identified from research in the city directories of Wichita, Kansas, and analyzed based on data from the National Establishment Times-Series database.

Food has played a large role in ethnic entrepreneurship, with restaurants and grocery stores being the largest categories. Initially, these were formed in the context of what Gabbacia has called “food enclaves,” which served the needs of specific ethnic and immigrant groups. Footnote 45 Groceries offer unique food products, especially ones imported from abroad. This is true for both Asians and Latinos. Asians are more present in that sector, but that is likely due to the fact that Broadway has an especially large number of Vietnamese restaurants as compared to the rest of the city, while Latino and Mexican restaurants are more widely spread across Wichita, not concentrated in one section. However, both areas have expanded beyond those enclaves with the rising national popularity of Mexican and Vietnamese food. Today, “foodies” from across the city know to come to Broadway and 21st Street to get good Mexican food and ingredients. Meanwhile, Vietnamese restaurants offer foods ranging from pho soup to bánh mì sandwiches; they have gained a citywide following, even participating in the city’s annual Asian Festival that packs the Century II auditorium each fall. Footnote 46

Asian entrepreneurs are either the majority or exclusive presence in the areas of video rental stores, insurance, and beauty and jewelry shops. The other major category that is exclusively Asian is that of motel operators, which research confirmed were Asian Indians. Latino entrepreneurs appeared exclusively among auto repair shops and retail stores.

Asians and Latinos are roughly equal in certain areas, including telecommunications, especially cell phone sales and repair; legal services, given that both face immigration issues; and general merchandise. Therefore, both Asian and Latino entrepreneurs are found in sectors that relate to the practical needs of an immigrant-based population. In both cases, adjustment entrepreneurship is a prominent presence. The nature of the business pursued in terms of size of venture and duration of operation reveal other patterns.

The number of businesses that opened in a given year is shown in Figure 2. There was an increase in the early 1990s for both Asian and Latino establishments, consisting of six businesses in total. The 1990s saw no new Latino businesses created, and Asian entrepreneurs founded between two to four. There was a second growth spurt in the early 2000s in which Latino entrepreneurs became more active, culminating in a noticeable spike about 2010. As with the maps, the increased presence of Latino establishments corresponds with the continued immigration from Latin America.

Figure 2 The year Asian, Latino, or total businesses opened.

Source: National Establishment Times-Series database.

The groups of businesses compared by years of operation are shown in Figure 3. The largest single group is the one in which ventures are open between one and five years. The question remains whether the tendency toward short lifespans points to establishments not closing after a time or simply being new. Moreover, the breakdown by ethnicity initially shows that Asian ventures outnumber Latino ones in every category, but additional analysis also shows that there is more to the story.

Figure 3 Range of years Asian, Latino, and total businesses opened.

Source: National Establishment Times-Series database.

Business closings have remained largely constant from 1990 through 2012, with a slight increase in Asian venture closings around 2000 (Figure 4). There is an understandably visible jump in the wake of the 2008 recession, although for reasons not quite clear, that jump was especially evident for Latinos and markedly less so for Asians. More research is needed to determine if, for example, the discrepancy points to Asian businesses being better able to weather an economic downturn or whether their customers came from a stable Asian community, in contrast to Latinos who saw a decline in Mexican immigration circa 2010. For Latinos, newness seems a contributing factor for the short business lifespans, although how significant that factor is will require a future study several years from now to see how long the current cohort remains open. Latino ventures did not start to emerge significantly until the 2000s, and especially so in the 2010s. Most businesses older than eleven years likely existed in the 1990s, which was a period of low growth for Latino ventures. Like Latinos, Asian businesses also fell largely in the short one- to five-year lifespan category. Unlike Latinos, however, that trend cannot be tied to a wave of recent openings, given the relatively constant rate of business founding across this time period.

Figure 4 Range of years Asian, Latino, and total businesses closed.

Source: National Establishment Times-Series database.

Comparing Latino and Asian business employment highlights how these two groups differ. The differences in scale are illustrated in Figures 5 and 6.

Figure 5 Percentage of average number of Asian employees.

Source: National Establishment Times-Series database.

Figure 6 Percentage of average number of Latino employees.

Source: National Establishment Times-Series database.

Ethnic entrepreneurship lends itself to family businesses in general, and Latino ventures were significantly more likely to consist of small establishments. Nearly two-thirds had one or two employees, and 90 percent had fewer than four employees. Stores such as Super del Centro or restaurants such as La Chinta were visible examples of businesses with large numbers of employees, but they were not typical. Asian businesses, by contrast, had more variety in terms of numbers of employees. Although small ventures were by far the norm, nearly 50 percent had between three and six employees. This may be a reflection of the type of business taking place, with beauty salons, for example, being a common venture. It may also indicate extended families working together. More research needs to be conducted to delve into these matters, but even raw numbers point to larger differences between the two groups. As with number of employees, sales figures also illustrate differences (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7 Percentage of average sales (in the 1,000s) for Asian businesses.

Source: National Establishment Times-Series database.

Figure 8 Percentage of average sales (in the 1,000s) for Latino businesses.

Source: National Establishment Times-Series database.

Again, Latino entrepreneurship tends to be small in scale, with almost half reporting income of under $100,000. For Asians, the largest single cohort is between $101,000–$200,000, with the $201,000–$300,000 cohort being nearly 20 percent of the total. This may be related to the number of Latino businesses just starting out. It may result also from differences in the type of businesses, with jewelry being a component of the Asian story but not the Latino one. Moreover, the Asian figure is even more striking in light of the fact that in the 1990s, several businesses, like Thai Binh, left Broadway as they grew.

What emerges immediately is that most long-term businesses, those at least ten years old, tend to be Asian businesses, again reflecting in part the newness of the Latino business presence on Broadway (Map 2). Among this group is the handful at the northern end of the study area; the remnants of a once larger Asian presence that was especially visible in the 1990s. Thus, the north end of the study area indicates a region that, at least in terms of business activity, had once been Asian but has since become more Latino in character. A concentration of Asian ventures in the middle and lower ends of the study area include both established enterprises and new ones.

Map 2 Latin and Asian businesses at least ten years old as of 2010 Census, showing Asian and Hispanic populations from the 2010 Census.

When correlated with the residential census data, as illustrated in Maps 2, 3, and 4, an even more striking pattern emerges. Map 4 shows the significant Hispanic and Latino population in the northern part of Wichita, a population with a substantial immigrant component. Broadway is an important artery of a larger neighborhood—or set of neighborhoods—that also contains Hispanic cultural organizations, such as the La Familia Senior Center, as well as religious ones, such as the parishes of St. Patrick’s and Our Lady of Perpetual Help and their Spanish-language Protestant congregations. Nearby are the stores on 21st Street, such Rodriguez Fashions, which caters to the quinceañera businesses. There is a long-established farmer’s market on 28th Street and Broadway. Also nearby are clubs that support the needs of migrants from specific parts of Mexico, such as Sinaloa. Having Latino businesses on Broadway, therefore, is a logical extension of a growing Hispanic community.

Map 3 Asian population in Wichita, Kansas, 2010.

Map 4 Hispanic population in Wichita, Kansas, 2010.

This contrasts markedly with the low Asian residential population in the Broadway area (see Map 3). One segment, the Asian Indians, are small in number and are spread out among the motels along the route. The larger Asian population, the Vietnamese, represent a more complicated story. Although Broadway had some Southeast Asian residents in the 1970s and 1980s as part of refugee resettlement programs, that population did not stay in the area to form the nucleus of a Vietnamese neighborhood that would have frequented local stores and restaurants. By the late 1990s, Vietnamese families that had established themselves beyond the immediate needs of a refugee and immigrant experience had moved to other areas of the city and were not concentrated in one neighborhood. Thai Binh moved to 21st Street in the 1990s, and therefore it was part of a shift away from Broadway toward a more dispersed pattern. Using automobiles to travel to and from work, religious events, and other activities made the Vietnamese function as any other suburban population. While Broadway is close to established Hispanic organizations such as the La Familia Senior Center, the parish of St. Patrick’s, and numerous Spanish-language Protestant congregations, the main Vietnamese Catholic parish is that of St. Anthony, located on Second Street and Ohio Avenue. The main Vietnamese Buddhist temples include the Phap Hoa Temple on Arkansas Avenue, north of 45th Street, and the Buu-Quang Temple, on south Hydraulic Avenue, near the Kansas Turnpike. As part of local resettlement efforts, the Vietnamese were initially concentrated along North Broadway. As Map 3 indicates, Asians, of whom the Vietnamese are one of the most significant components, are now most notably concentrated in the city’s southeastern quadrant. Little Saigon, as some locals have called the section of Broadway between 9th Street and 13th Street, is now simply a commercial concentration instead of a traditional ethnic neighborhood.

Conclusions, Findings, and Future Research

This study used three techniques to analyze two major groups of ethnic entrepreneurs, Latino and Asian, along Broadway, a key historical corridor in Wichita, Kansas. The three techniques were historical scholarship using city directories, interviews, and census data; geographical mapping of a time-series data; and business data analysis using the Dun and Bradstreet NETS database. Taken together, the three techniques reveal several patterns regarding Latino and Asian ethnic entrepreneurship. We focused on ethnic entrepreneurs on Broadway, as opposed to immigrant entrepreneurs (recent arrivals to the United States to start a business) or minority entrepreneurs (for example, women and African Americans). All three types of entrepreneurs followed the definitions given by Chaganti and Green, as noted earlier. Footnote 47

Historical research revealed the similarities and differences of the Latino and Asian entrepreneurial practices, when compared with each other and when compared with other groups, such as Jews, Syrian–Lebanese, Chinese, and Japanese. It also highlighted some differences between ethnic, immigrant, and minority entrepreneurs. For several populations, the literature has focused on labor and working classes of these groups, and less so on entrepreneurs and small-business owners. The geographical mapping of the time-series data every ten years, from 1970 through 2010, illustrates that the ethnic entrepreneurial presence along Broadway was initially Asian in nature, with Latinos arriving later in the 2010s.

After 2000 the distribution of enterprises is especially telling, with Latinos emerging initially in the midst of a collection of Asian establishments. The 2010s saw the appearance of several Latino businesses north of 17th Street. This growth of Latino entrepreneurship is related to the overall expansion of the Latino population in the north part of Wichita, and it represents a segment of an even greater business presence along 21st Street. Further south on Broadway, a particularly Vietnamese business presence emerged between 9th Street and 17th Street, but as the mapping suggests, it was not tied to a concentrated Vietnamese population base. For Asians, Broadway’s growth began in the wake of early refugee settlement activities; it has now become a centrally located commercial district that serves a population spread out across the city.

From business data analysis using both the NETS database and the census data, it is evident that entrepreneurs from both populations share many common features. Their businesses tend to support the needs of immigrant populations and to provide specific services to those groups. Food service, including grocery stores, markets, and restaurants, are important sectors, as are those that relate to legal matters, particularly in areas of immigration status. There are differences, such as auto repair among Latinos and health and beauty services among Asians.

Many times, ethnic businesses tend to operate in the midst of a neighborhood inhabited by people with the same ethnic background. Examples include general Chinatowns and Koreatowns, the specific Jewish diamond district in New York on 47th Street between 5th and 6th Avenues, downtown East Dearborn on Michigan Avenue between Evergreen Street and the Ford Freeway (I-94), or the Cuban immigrant business community that has transformed Miami into what some have called the “Capital of Latin America.” Footnote 48 In Wichita, by contrast, along Broadway between 9th Street and 21st Street, two ethnic entrepreneurial groups coexisted and conducted business side by side without competing against each other for customers or suppliers. The Latino community developed elements of an ethnic neighborhood but the Asian population has not. The two groups have different networks of suppliers, so price wars that existed among suppliers serving the same group of businesses did not exist in this case. Similarly, the two ethnic groups served different pools of customers (Latino or Asian) with a common pool (mainly whites) that went to Broadway to eat in ethnic restaurants or buy ethnic groceries simply because they have a taste for ethnic foods. Both groups of businesses followed their respective target markets. The expansion of the Latino business presence related to the influx of Mexican immigration, and Asian businesses moved following shifts in the Vietnamese and other groups.

Although the stories are different, they both share a common feature: they represent the future of entrepreneurship in Wichita, which has had a long tradition of entrepreneurial innovation. It is the birthplace of companies, from Coleman and Mentholatum; to White Castle Hamburgers and Pizza Hut; to Cessna, Stearman, Beechcraft, and Learjet; to Rent-a-Center; to the varied activities of the Garvey and Koch families. While cities across the United States have fostered local companies that became nationwide brands, Wichita has been particularly proud of its entrepreneurial heritage. Wichitans have long felt a sense of pride from being in a city that encouraged and supported small business development. Entrepreneurship has even been the focus of local Convention and Visitors Bureau events. One promotional booklet from 1992 explained that “a diverse mix of entrepreneurs brought a stabilized economy, and today, the modern clean city of Wichita is a far cry from the village that drew Jesse Chisholm and ‘Buffalo Bill’ Matthewson.” Moreover, “Wichita was the birthplace of many original companies that continue to define its economic profile.” Footnote 49 Even for the Midwest, a region long known for its aggressive pro-business boosterism, Wichita has been especially proud of its entrepreneurial heritage. Footnote 50

That pride received a major blow in recent years when research, including that of Wichita-raised predictive analyst James Chung, thought that the city was losing its entrepreneurial edge. Chung sent shockwaves through the community when he suggested that Wichita was not creating new businesses at a favorable rate, even when compared to its neighboring cities, noting: “It strikes at the heart of what made Wichita. With fewer of the people who would be entrepreneurs, entrepreneurship no longer drives Wichita.” Footnote 51 Of the 366 metropolitan communities that Chung rated as “start-up density” areas, Oklahoma City was 59th; Kansas City, 81st; Des Moines, 116th; and Wichita, 227th. In contrast stood Kansas City, which the Global Entrepreneurship Congress’ Cities Challenge named as among the world’s most entrepreneurial cities for its support of small business creation. Wichita, the city that was once a model for business development, was falling behind. Footnote 52

Analysts like Chung have suggested several directions forward, including coming to terms with diversity in local entrepreneurship and moving beyond a business story that tends to be dominated by white, native-born individuals. The city’s increasingly diverse populations means that if entrepreneurship is to continue, it has to do so among the ranks of ethnic, minority, and immigrant business creators. Among them are those on Broadway, where ethnic businesses exist next to Anglo-American ventures as well as franchises from national chains.

Wichita is not alone in these trends, given the significant growth of ethnic entrepreneurship across the world. John Logan, a sociology professor at Brown University and the director of the 2010 U.S. Census Project, said that in Kansas, “the youth of the state is becoming much more rapidly Asian and Hispanic.” Footnote 53 The 2010 census showed that the Kansas population grew by 6.1 percent from the 2000 census. The white resident population went down, the Hispanic population went up by 59 percent, and the Asian population went up by 45 percent. For the first time in the history of the state, the Hispanic population overtook the non-Hispanic black population.

For Wichita in particular, non-Hispanic whites and blacks grew by about the same number (8,000). The Hispanic population almost doubled (from 33,000 to 58,000), and the Asian population went up by 33 percent (from 15,000 to 21,000). The 2010 census also showed increased integration of non-Hispanic whites with non-Hispanic blacks in Wichita in the metropolitan area, but that Hispanics and Asians are not integrating as much but instead are moving into neighborhoods that have more concentration of people with similar race or ethnicity. Adrienne Foster, chairwoman of the Wichita Hispanic Chamber of Commerce Board of Directors said, “The growth trend in the Hispanic demographic in the state, and in Wichita, is changing the economic landscape” and that “a few years ago, it wasn’t cool to be Latino, but now it is. People are realizing our buying power as consumers and our voting power.” Footnote 54 It is an educated estimate to say that with such high growth of the Hispanic population in the last ten years, in Wichita and Kansas, this trend will continue into the future. It even extends across national boundaries. Marco Alcocer, a Mexican-born entrepreneur who runs the bilingual journal El Perico (unconnected to the restaurant on Broadway), recently observed that Mexico was Kansas’s second biggest export market, accounting for US$1.8 billion in 2014, with a total trade between Mexico and Kansas being US$2.7 billion. Footnote 55

There is a usually a thin line separating ethnic and immigrant entrepreneurs. Over time, immigrant entrepreneurs may breed ethnic entrepreneurs or vice versa. As Roger Waldinger and colleagues have noted, in the United States, for example, “self-employment accounted for a substantial share of the employment of these newcomers who moved to the United States since the renewal of large-scale immigration in 1965.” Footnote 56 This is a key reason to discuss the topic of immigrant entrepreneurship. A study by the National Foundation for American Policy (NFAP) focused on studying startup companies that are fast growing. Footnote 57 The study gathered information from eighty-seven U.S. private startup companies valued at $1 billion (as of January 1, 2016) and tracked by The Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones Venture Sources. These companies are sometimes called “unicorns” because they are private and have not yet been listed on the stock market but may be in the future. Their research found that 51 percent of these companies had at least one immigrant founder. Also, 71 percent of the companies had at least one immigrant in a key management or product development position, such as chief executive officer, chief technology officer, and vice president of engineering. These billion-dollar companies excel at job creation. SpaceX, started by South African Elon Musk, is valued at $12 billion and employs 4,000 people. Uber, started by Garrett Camp, an immigrant from Canada, employs 900 direct employees and more than 162,000 drivers. India (with fourteen entrepreneurs on the list) was the leading country of origin for immigrant founders of these billion-dollar companies, followed by Canada and the United Kingdom with eight each. In almost half of the billion-dollar companies, the founder was an immigrant who first came to the United States as an international student. The NFAP study clearly shows that immigrant entrepreneurs make important contributions to entrepreneurship in America. They are innovative and bring new ideas to start new companies on their own or join forces with native-born cofounders. Footnote 58