1. Introduction

1.1 Status of the transport field

Membrane transport, the vectorial movement of molecules across biological membranes, is a subject which like many other fields within the biological sciences has thrived in the latter half of the 20th century. During this period, the properties of a multitude of membrane transporters have been subjected to close study to reveal their properties such as their kinetic features, substrate specificity and the nature of the transport mechanism. This has entailed detailed investigations on the energetic basis of membrane transporters as well, be it either their status as primary active transporters supported by the chemical energy derived from the hydrolysis of ATP, or as secondary cotransport or antiport systems driven by the ion gradients and/or the membrane potential, created by the active transport systems. Dominant roles in this regard are played by the Na+, K+-ATPase in animal cells and by proton ATPases in the outer membranes of plants and yeast cells and in bacteria that provide the driving force for the concentrative uptake of nutrients and other essential cell constituents by a wealth of secondary transport systems.

Early on the physical nature of membrane transporters, with a few notable exceptions (like the Na+, K+-ATPase, the sarcoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase, the lactose permease and bacterial rhodopsin) had to be treated like a ‘black-box’, as proteinaceous entities of unknown nature that only are expressed by cells in minute amounts. Even though this situation has changed as the result of subsequent cloning and genomic analysis, the fact remains that until recently the understanding of membrane transport in structural terms has mainly been based on theoretical concepts and models. In early ideas, it was realized that membrane transporters which in their kinetic behavior and substrate specificity show many similarities with ordinary enzymes, also exhibit features such as transport-induced counter transport which suggested that the transporter is capable of literally ferrying the transported substrate molecules in a carrier–transport complex across the membrane according to the so-called mobile carrier hypothesis (Patlak, Reference Patlak1957; Wilbrandt & Rosenberg, Reference Wilbrandt and Rosenberg1961). But realizing that cellular membranes present formidable hydrophobic barriers with their protein transporters firmly anchored in a lipid environment, models of membrane transport have subsequently focused on the passage through waterfilled pores or channels in proteins, equipped with internal and external gates with allosteric properties (Jardetzky, Reference Jardetzky1966; Vidaver, Reference Vidaver1966). In many ways, these gates are, in the modern view, considered analogous to those present in channel proteins (Accardi & Miller, Reference Accardi and Miller2004; Gadsby et al. Reference Gadsby, Rakowski and De Weer1993, Reference Gadsby2009), but coordinated in such a way that they lead to the formation of ‘occluded’ and ‘alternating access’ states, making transport against electrochemical gradients feasible. On this background with information on kinetic aspects, but a lack of detailed information on the structures and mechanisms of membrane transporters, it is significant that the situation has changed significantly during the past few years, which have witnessed the clarification of the three-dimensional (3D) structure of a large number of especially procaryotic membrane transporters and channel proteins by X-ray diffraction analysis. As a result, we are now entering a new era where many of the structural underpinnings of the transport process can be identified. Primary ATPase transporters, coupled to the hydrolysis (or synthesis) of ATP, can be categorized as P-, F-, V-ATPases and ABC-transporters (Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2007). Among these, P-type ATPases comprise a family of cation transporters where the formation of an aspartylphosphorylated intermediate drives the active transport of cations. In addition to SERCA and other Ca2+-ATPases, the P-type ATPase family comprises major primary transporters like the Na+, K+-ATPase and gastric H+, K+-ATPase in animals, H+-ATPase in plants, yeasts and heavy metal (e.g. Cu+) ATPases, (Axelsen & Palmgren, Reference Axelsen and Palmgren1998; Lutsenko & Kaplan, Reference Lutsenko and Kaplan1995; Møller et al. Reference Møller, Juul and Le Maire1996). The F-type ATPases consist of a cytosolic (F1) ADP phosphorylating and a membraneous (Fo) proton transporting part, leading to a proton gradient-dependent synthesis of ATP that are present in mitochondria, chloroplasts and bacterial membranes. The structure of the cytosolic F1 part has been obtained at atomic resolution from bovine (Abrahams et al. Reference Abrahams, Leslie, Lutter and Walker1994) and yeast (Kabaleeswaran et al. Reference Kabaleeswaran, Puri, Walker, Leslie and Mueller2006) mitochondria in many different functional states which in conjunction with other biophysical investigations have led to the formulation of rotary mechanisms for the proton transport and ATP synthesis by these proteins (reviewed by Junge et al. Reference Junge, Sielaff and Engelbrecht2009). Less is known about the structure of the V-(vacuolar) ATPases; however, they are probably built on the same principles as the F-synthetases, but in contrast to these their physiological function is to hydrolyze ATP to energize the transport of protons across the plasma membranes and membranes of intracellular organelles, to assist the membrane trafficking of proteins by endo/exocytotic processes (Hinton et al. Reference Hinton, Bond and Forgac2009; Saroussi & Nelson, Reference Saroussi and Nelson2009). ABC transporters are involved in the ATP-dependent import or export of a wide range of organic substrates like cholesterol, fatty acids, carbohydrates, drugs and peptides (Hinton et al. Reference Hinton, Bond and Forgac2009; Saroussi & Nelson, Reference Saroussi and Nelson2009). Insights into their structure and function as alternating access transporters have been acquired from prokaryotic homologues such as the multidrug resistant Sav1866 transporter (Dawson & Locher, Reference Dawson and Locher2006), a putative molybdate transporter (Hollenstein et al. Reference Hollenstein, Dawson and Locher2007) and a maltose transporter (Khare et al. Reference Khare, Oldham, Orelle, Davidson and Chen2009).

Within P-type ATPases, the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase was the first transporter for which the 3D structure was clarified (Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Nakasako, Nomura and Ogawa2000; Toyoshima & Nomura, Reference Toyoshima and Nomura2002). This Ca2+ transporter, also denoted as SERCA isoform 1a, is the subject of the present review. It is present in large amounts in skeletal muscle, especially in the longitudinal tubules of sarcoplasmic reticulum of fast twitch muscles, where the protein, as part of the excitation–contraction coupling machinery, plays a vital role in the contractile behavior of skeletal muscles. Generally, the diverse isoforms of SERCA, present in other tissues than skeletal muscle together with the plasma membrane- and Golgi (secretory pathway) Ca2+-ATPases play indispensable roles for proper cell function and for maintaining the low cytosolar concentrations of Ca2+ that are necessary for Ca2+ signaling processes, not only in the excitation–contraction coupling of the skeletal muscle, but also for a multitude of other cellular processes such as neurotransmission, neurosecretion, antibody formation, egg fertilization, etc. (Carafoli, Reference Carafoli2002). They are all structurally alike and their transport is dependent on the formation of an ‘energy rich’ aspartylphosphorylated intermediate formed by reaction with ATP that drives the transport of Ca2+ across their resident intracellular or extracellular membranes.

With respect to the sarcoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase, we have to realize at the outset that such a vast amount has been published on the properties of this particular membrane protein that it would defy any attempt to cover this subject fully in a succinct manner. Instead, our review focuses on the developments that have taken place after the appearance of the detailed X-ray-based structures published at the onset of the new millennium (Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Nakasako, Nomura and Ogawa2000; Toyoshima & Nomura, Reference Toyoshima and Nomura2002). But before dealing with these issues, we give, by way of introduction, in the following subsections of section 1 first an updated scheme for the intermediary reactions associated with the Ca2+ transport, based mainly on kinetic and other biochemical investigations of the partial reactions of the transport cycle. This is followed by a short account of earlier studies pertaining to the spatial structure of the ATPase up to the point when crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis became available. Finally, we present in the last subsection of section 1 an overview of the crystal structures deposited in the PDB database, with an account of the procedures by which they have been produced. Sections 2–4 then consider in detail our views on what has been learned from these structures, both with regard to the structure, mechanism and regulation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. These aspects are considered in relation to data obtained by mutational, biochemical and other studies. Finally, in section 5 we give an overview of the reaction mechanism in connection with a discussion of the energetic aspects and briefly consider future directions for exploration.

The importance of the P-type ATPase field is reflected by a large number of both specialized and general reviews. Among the more recent ones and pertinent for the various aspects and methodologies used for the investigation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase, we can refer to the following: spectroscopic studies Bigelow & Inesi (Reference Bigelow and Inesi1992); mutational studies: Andersen (Reference Andersen1995a), MacLennan et al. (Reference Maclennan, Rice and Green1997); kinetics and Ca2+ binding: Mintz & Guillain (Reference Mintz and Guillain1997); structure and function: Lee & East (Reference Lee and East2001), Stokes & Green (Reference Stokes and Green2003), 3D crystals: Toyoshima & Inesi (Reference Toyoshima and Inesi2004), Møller et al. (Reference Moller, Nissen, Sorensen and Le Maire2005), Møller et al. (Reference Møller, Olesen, Jensen and Nissen2005), Toyoshima (Reference Toyoshima2008). Among general aspects of the P-type ATPase structure, function and family tree we can mention reviews by Läuger (Reference Läuger1991), Lutsenko & Kaplan (Reference Lutsenko and Kaplan1995), Møller et al. (Reference Møller, Juul and Le Maire1996), Axelsen & Palmgren (Reference Axelsen and Palmgren1998), Jørgensen et al. (Reference Jørgensen, Hakansson and Karlish2003), Kühlbrandt (Reference Kühlbrandt2004). In addition to SERCA 1a detailed X-ray-based structures of P-type ATPases are available for Na+, K+- ATPase from the pig kidney (Morth et al. Reference Morth, Pedersen, Toustrup-Jensen, Sorensen, Petersen, Andersen, Vilsen and Nissen2007) and the rectal shark gland (Shinoda et al. Reference Shinoda, Ogawa, Cornelius and Toyoshima2009) and for the Arabidopsis thaliana H+-ATPase from the yeast-expressed protein (Pedersen et al. Reference Pedersen, Buch-Pedersen, Morth, Palmgren and Nissen2007). However, it is expected that in the coming years the field will become enriched by the clarification of many new structures of other P-type ATPases that based on their individual properties will enable the unraveling of details of the P-type ATPase mechanism and regulation.

1.2 The Ca2+ transport cycle

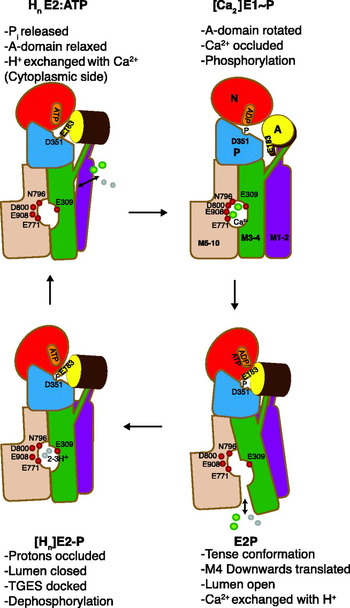

In terms of mechanism, P-type ATPases can be referred to as chemi-osmotic pumps, driving transformation of the chemical energy of an aspartylphosphorylated intermediate into an active transport of cations. In the case of SERCA, each ATP hydrolytic event results in the transport of two Ca2+ ions in antiport with 2–3 protons (Cornelius & Moller, Reference Cornelius and Moller1991; Levy et al. Reference Levy, Seigneuret, Bluzat and Rigaud1990; Yü et al. Reference Yu, Carroll, Rigaud and Inesi1993). The coupling between Ca2+ transport and ATP hydrolysis is tight, leading to high accumulation ratios, which in the case of the SERCA 1a isoform present in the skeletal muscle can attain Ca2+ concentrations 20–40 000 times higher inside the vesicles. In Fig. 1 the ATP-dependent Ca2+ transport and H+ countertransport by the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase is depicted in terms of six steps where phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated E1 and E2 intermediates alternate in a cyclical manner: in step 1, two cytosolic Ca2+ ions react with the transporter in a non-phosphorylated E2 state with bound ATP to form a Ca2E1:ATP intermediate. The binding of Ca2+ is accompanied by the release of 2–3 protons to the cytosol. The conformational change of the ATPase from the E2 to the E1 states in step 1, induced by the binding of Ca2+, is followed by the rapid autophosphorylation of Asp 351 from the bound ATP in step 2. The result is the formation of a ‘high-energy’ phosphorylated [Ca2]E1~P:ADP intermediate with occluded Ca2+. In step 3, the conformation of the ATPase is changed back to the E2 state, with the formation of a [Ca2]E2P:ATP intermediate, representing a ‘low-energy’ phosphorylated form of the ATPase, but still with occluded Ca2+ (Danko et al. Reference Danko, Daiho, Yamasaki, Liu and Suzuki2009). Simultaneously ADP, the product of the preceding autophosphorylation reaction, is exchanged by ATP. In step 4, the luminal part of the ATPase transmembrane domain opens, accompanied by deocclusion and release of Ca2+ to the luminal space. This occurs in exchange with n protons (n=2–3) and leads to the formation of the HnE2P:ATP intermediate, where the bound protons partially restore electrostatic balance inside the transmembrane domain after the debinding of Ca2+. After closure of the luminal channel, these protons are occluded inside the membrane segment in the [Hn]E2-P:ATP transition state (step 5). Finally, the latter intermediate becomes dephosphorylated step 6, and the transport cycle is completed with the formation of HnE2:ATP state.

Fig. 1. SERCA 1a structures representing key states of the transport cycle with bound nucleotide in terms of the following reactions: (1) The exchange of n protons (n=2–3) for 2 Ca2+ ions. (2) The phosphorylation reaction with ATP with the formation of the [Ca2]E1~P:ADP intermediate with occluded Ca2+. (3) The conversion of [Ca2]E1~P:ADP to [Ca2]E2P:ATP after ADP/ATP exchange with occluded Ca2+ (still unknown structure). (4) The E2P ground state after luminal opening and the exchange of Ca2+ with luminal protons. (5) The formation of the proton occluded E2P transition state. (6) Dephosphorylation of the E2P transition to the E2 state with bound protons and ATP. The structures are shown in gray transparent surface and in cartoon, with the A-domain in yellow, N-domain in red, P-domain in blue, helix M1–2 in purple, M3–4 in green, M5–6 in wheat and M7–10 in gray. The TGES motif in pink spacefilling, Ca2+ liganding residues 309, 771 and 796 in sticks and Ca2+ ions in green spacefilling. [ ] represents an occluded state.

The intermediates and partial reactions assembled in Fig. 1 summarize a large body of both functional and structural studies on the Ca2+-ATPase, many of which are based on considerations that were already formulated in a concise manner by de Meis & Vianna (Reference De Meis and Vianna1979). As can be seen from the vignettes of Fig. 1, X-ray-based structures of the representative for almost all the relevant intermediates have been obtained. As we shall see from the detailed analysis in the following chapters, these give striking support to the scheme and emphasize the fundamental difference between the E1 and E2 conformations as arising from changes in the interactions among the cytosolic nucleotide binding (N-), phosphorylation (P-) and N-terminal (A- or actuator) domains, (colored red, blue and yellow, respectively, in Fig. 1). This includes events, whereby ATP-phosphorylating interactions between the N- and P-domains in the E1 state are shifted towards dephosphorylating interactions between the P- and A-domains in the E2 state. These changes are accompanied by concerted changes in the disposition of the helices in the transmembrane domain by which the intramembranous cation binding sites are changed from a configuration with high affinity for Ca2+ in the E1 state to a proton-preferring state in the E2 state with a release of the bound Ca2+. In this way, the catalytic events in the cytosolar part are coordinated with the translocation events in the transmembrane domain. As emphasized by Tanford (Reference Tanford1983), the scheme implies that Ca2+ translocation takes place on the basis of an alternating access mechanism where the intramembranous binding sites are open either towards the cytosolic space or towards the lumen, and separated by an intervening occluded state.

To sum up, Ca2+/H+ exchange is dependent on the existence of Ca2+-ATPase in two main conformational states, E1 and E2, among which E1 represents the forms that bind Ca2+ with high affinity and is phosphorylated by ATP with the formation of an ‘energy rich’ [Ca2]E1~P intermediate; whereas E2 represents the forms with a preference for the binding of protons that can be reversibly phosphorylated and dephosphorylated by inorganic phosphate. Compared to the usual schemes presented for Ca2+ transport by SERCA-type ATPase the present version emphasizes the fact that under physiological conditions the predominant form of all intermediates have nucleotide attached, either as ADP arising from the phosphorylation reaction with ATP (reaction 2) or as ATP that, although not enzymatically active, remains bound to the ATPase at the high concentration prevailing in the cell and exerts significant modulatory effects on all steps. As we shall see, this has a number of important consequences for the structural analysis of transport, but on the other hand, it should also be realized that the nucleotide bound forms are not a sine qua non for function: thus, in the test tube, the enzyme can be phosphorylated by low (μmolar) concentrations of ATP and can pass through all the subsequent intermediary steps without bound nucleotide, although with slower conversion rates. Finally, it should be noted that the terms E1 and E2 forms do not, as can be seen from Fig. 1, define the binding sites that are open towards either the cytosolic or luminal sides, a quite frequent misunderstanding; rather they refer to two distinctly different conformational states of the protein with high affinities for Ca2+ and protons, respectively.

1.3 Evolution of structural studies of Ca2+-ATPase

Being an important representative of a primary transporter, from the beginning it has been an important goal for investigators of the study of the sarcoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase to get hold of the detailed 3D structures of the protein as could be obtained by the X-ray diffraction analysis of well-ordered 3D crystals. In this section, we give a short account of structural studies leading up to the fulfilment of this goal. Early electron microscope (EM) pictures of the surface profile of isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum or Ca2+-ATPase purified membranes, made visible by negative staining, such as shown in Fig. 2a, revealed the presence of round and contrast-rich objects with a diameter of about 30–40 Å, connected to the membrane by a thin stalk (Greaser et al. Reference Greaser, Cassens, Hoekstra and Briskey1969; Ikemoto et al. Reference Ikemoto, Kitagawa, Nakamura and Gergely1968; Stewart & MacLennan, Reference Stewart and Maclennan1974; Thorley-Lawson & Green, Reference Thorley-Lawson and Green1973). The appearance of these objects were similar to the ‘lollipops’ that had previously been described for the ATP synthetase (Kagawa & Racker, Reference Kagawa and Racker1966a, Reference Kagawa and Rackerb); their proteinaceous nature was indicated by the fact that they could be removed by protease treatment or highlighted by labeling with Hg-phenyl azoferritin (Hasselbach & Elfvin, Reference Hasselbach and Elfvin1967). An asymmetric and preponderant cytoplasmic orientation of ATPase in the membrane was inferred from the diffraction analysis of stacked and partially ordered Ca2+-ATPase membranes by X-ray diffraction (Dupont & Hasselbach, Reference Dupont and Hasselbach1973) and by combined X-ray and neutron diffraction analysis, reviewed by Herbette et al. (Reference Herbette, Defoor, Fleischer, Pascolini, Scarpa and Blasie1985), whereas freeze fracturing of the membranes indicated that the intramembranous particles attributable to the membrane-inserted part of Ca2+-ATPase was mainly localized to the cytoplasmic bilayer leaflet (Deamer & Baskin, Reference Deamer and Baskin1969; Packer et al. Reference Packer, Mehard, Meissner, Zahler and Fleischer1974; Scales & Inesi, Reference Scales and Inesi1976). From these as well as related functional studies arose the notion of a clear segregation of catalytic and translocation events, the ATPase activity being localized in a hydrophilic head and separated from the intramembraneous Ca2+-binding sites in the membrane by an intervening stalk segment.

Fig. 2. Various approaches towards the structural characterization of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. (a) Vesicles of purified Ca2+-ATPase negatively stained with phosphotungstate, X217000. Reproduced from Stewart & Maclennan (Reference Stewart and Maclennan1974) Fig. 1d. (b) Model of Ca2+-ATPase based on X-ray and sedimentation equilibrium analysis of the deoxycholate solubilized monomer of Ca2+-ATPase. Reproduced from Fig. 10 of le Maire et al. (Reference Le Maire, Møller and Tardieu1981). (c) Membrane topology of Ca2+-ATPase based on predicted domain structure and hydrophobicity plots of the amino acid sequence. Reproduced from Fig. 5 of Brandl et al. (Reference Brandl, Green, Korczak and Maclennan1986). (d) 3D structure of Ca2+-ATPase, based on cryo-electron microscopy of 2D tubular crystals of Ca2+-ATPase. Reproduced with slight changes from Fig. 4 of Toyoshima et al. (Reference Toyoshima, Sasabe and Stokes1993).

In another line of investigation, the properties of the Ca2+-ATPase were investigated after isolation from the membraneous environment by solubilization with detergent. From analytical ultracentrifuge experiments, the protein molecular mass was determined to be 110–115 kDa after solubilization in a monomeric state with SDS (Rizzolo et al. Reference Rizzolo, Maire, Reynolds and Tanford1976) and deoxycholate (Jorgensen et al. Reference Jorgensen, Lind, Roigaard-Petersen and Moller1978; le Maire et al. Reference Le Maire, Jorgensen, Roigaard-Petersen and Møller1976). In conjunction with small angle X-ray scattering analysis, the structure of the deoxycholate solubilized monomer was found to have a length of 110 Å with a scattering profile, which as shown in Fig. 2b could be resolved in terms of a head and a long shaft considered to comprise both the stalk and the membrane-inserted part (le Maire et al. Reference Le Maire, Møller and Tardieu1981). Further studies on the C12E8 solubilized and enzymatically active monomer (Andersen et al. Reference Andersen, Lassen and Moller1985b) and reconstituted Ca2+-ATPase (Heegaard et al. Reference Heegaard, Le Maire, Gulik-Krzywicki and Moller1990) established the monomer as the basic Ca2+ transporting unit. However, these studies also indicated that at high protein concentrations oligomerization or aggregation of the C12E8 solubilized Ca2+-ATPase is likely to occur in detergent solubilized and consequently also membraneous Ca2+-ATPase (Andersen et al. Reference Andersen, Vilsen, Nielsen and Moller1986), a circumstance that may be the background for the nonlinear kinetics of a regulatory nature reported for the Ca2+-ATPase in the native membrane (Mahaney et al. Reference Mahaney, Albers, Waggoner, Kutchai and Froehlich2005).

A new era of EM investigation of membraneous Ca2+-ATPase was initiated with the discovery that 2D crystals of Na+, K+-ATPase could be formed in the presence of vanadate (Skriver et al. Reference Skriver, Maunsbach and Jorgensen1981), a methodology that was subsequently applied to Ca2+-ATPase where incubation of the protein in the E2 state with vanadate gave rise to tubular structures with Ca2+-ATPase assembled in dimeric helical rows (ribbons) with opposite polarity (Dux & Martonosi, Reference Dux and Martonosi1983). From the electron diffraction analysis of negatively stained specimens, it was possible to obtain a 3D low-resolution reconstruction map (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Dux and Martonosi1986), which showed the ATPase structure to be composed of two cytosolic domains, the larger one extending 60 Å up from the transmembrane plane, whereas the second and smaller one appeared as a lobe attached to the larger domain and separated approximately 18 Å from the membrane (Castellani et al. Reference Castellani, Hardwicke and Vibert1985; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Dux and Martonosi1986). Meanwhile, with the publication of the complete primary structure of Ca2+-ATPase (MacLennan et al. Reference Maclennan, Brandl, Korczak and Green1985) a topological map of the ATPase was proposed (Brandl et al. Reference Brandl, Green, Korczak and Maclennan1986) based on ten transmembrane helices and an organization of the cytoplasmic part in terms of a central phosphorylation- and a nucleotide-binding domain, flanked by an N-terminal domain, tentatively assumed to be important for coupling ATP hydrolysis to Ca2+ translocation (Fig. 2c). As shown in the schematic Fig. 2c the cytoplasmic domains were proposed to be connected to the membrane by cytosolic extensions of the five N-terminal transmembrane helices. In the following years, this model was substantiated by a number of proteolytic and immunochemical experiments, and subsequently applied to Na+, K+-ATPase where for a long time only models based on eight transmembrane segments had been considered (reviewed by Møller et al. (Reference Møller, Juul and Le Maire1996)). With respect to the ultrastructural data, a major challenge at the end of the 1980s was to find out how the incomplete spatial model that had been obtained from negatively stained specimens of E2-vanadate crystals could become integrated with the topological map, arising from the primary structure and functional data. This was first tackled, by preparing Ca2+-ATPase stacked in planar bilayers in the E1 conformation (Stokes & Green, Reference Stokes and Green1990).This was done by the relipidation of C12E8-solubilized ATPase, in the presence of a high (10 mM) concentration of Ca2+, according to a recipe that had previously been described by Pikula et al. (Reference Pikula, Mullner, Dux and Martonosi1988). In fact, the protocol for producing these preparations was basically very similar to the procedure that with subtle refinements led to the 3D crystals from which the first structure of the ATPase at atomic resolution was obtained (Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Nakasako, Nomura and Ogawa2000). Compared to the present standards, the diffraction properties of these initial crystallization attempts were poor, but nevertheless by the electron diffraction analysis of the frozen-hydrated and non-stained specimens, a projection structure of the whole ATPase could be obtained at 6 Å resolution from which the intramembranous domain was deduced to have a half-moon-shaped structure with a sufficient trans-sectional area to accommodate ten transmembrane helices (Stokes & Green, Reference Stokes and Green1990). A subsequent analysis of tubular samples, prepared according to the usual recipe with EGTA and vanadate, but improved by the electron diffraction analysis of frozen hydrated tubular specimens, resulted in an image of the complete E2 cytoplasmic and membrane-embedded ATPase at 14 Å resolution (Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Sasabe and Stokes1993). The structure indicated a more compact organization of the cytoplasmic part than previously computed, with a shape which now resembled the beak of a bird, and suggested a three- or four-partite construction of the transmembrane helices (Fig. 2d). More detailed images of the shape were provided in two following studies where the resolution had been reduced to 8 Å (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Toyoshima, Yonekura, Green and Stokes1998) and to 6 Å resolution (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Rice, He and Stokes2002) after stabilization of the E2 form of the ATPase structure with bound thapsigargin. Further attempts to produce Ca2E1-ordered specimens by C12E8 treatment and relipidation indicated a less compact cytoplasmic organization than in the tubular crystals, suggestive of a fundamentally different conformation of the ATPase in the E1 and E2 conformations (Cheong et al. Reference Cheong, Young, Ogawa, Toyoshima and Stokes1996; Ogawa et al. Reference Ogawa, Stokes, Sasabe and Toyoshima1998). Together with a wealth of data obtained during this period on the role of particular amino acid residues, provided by mutagenesis, e.g. of the Ca2+-binding and phosphorylation sites (Andersen, Reference Andersen1995a; MacLennan et al. Reference Maclennan, Rice and Green1997), chemical modification and fluorescence energy transfer (Bigelow & Inesi, Reference Bigelow and Inesi1992; Møller et al. Reference Møller, Juul and Le Maire1996) they allowed fairly accurate, although unproven ideas about the construction and function of the ATPase to be proposed, which later could be verified and elaborated at the time when X-ray structures of Ca2+-ATPase at atomic resolution took over. The most noticeable flaw of the 2D reconstructions was the absence of unambiguously identifiable landmarks in the structure. Thus, it was a complete surprise when it turned out that the beak of the cytoplasmic bird profile was occupied by the N-terminal domain rather than being the location for nucleotide binding as had been postulated from 2D reconstructions of Ca2+-ATPase with CrATP and other non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs (Yonekura et al. Reference Yonekura, Stokes, Sasabe and Toyoshima1997). The reason for this failure was that the resolution simply was not good enough to unambiguously identify neither the location of small ligands nor of helical segments and their connectivity in the 2D-reconstructed images. These problems were immediately resolved when it became possible to prepare crystals of Ca2+-ATPase suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis.

1.4 Crystals of Ca2+-ATPase

In this section, we consider some methodological aspects that are important for the preparation of well-diffracting crystals of Ca2+-ATPase. As mentioned above the approach is in principle very similar to that previously used for obtaining stacked Ca2+-ATPase specimens for the 2D analysis by electron diffraction analysis: in both cases, the embedment of the Ca2+-ATPase into a detergent-saturated phospholipid bilayer is required, and so far C12E8 has turned out to be the detergent of choice for solubilization of Ca2+-ATPase. Table 1 summarizes which we consider as the most essential among the SERCA 1a structures that have been deposited in the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank, representative of the ATPase during the various stages of transport and in combination with specific ligands and inhibitors. Most of these are present at a sufficiently high resolution (2·3–3·1 Å) such that they not only reveal the course and secondary structure of the polypeptide mainchain, but also enable the assignment of the amino acid side chains and bound ligands As can be seen from Table 1, most of the functionally relevant forms have been obtained by the use of structural analogs of ATP (AMPPCP and AMPPNP) and of phosphate (AlF4−, BeF3−, MgF42−), in a similar way as these compounds have served to characterize phosphorylated intermediates of, e.g. transducin (Antonny & Chabre, Reference Antonny and Chabre1992; Chabre, Reference Chabre1990), myosin ATPase (Park et al. Reference Park, Ajtai and Burghardt1999), G-proteins (Sondek et al. Reference Sondek, Lambright, Noel, Hamm and Sigler1994), phosphotransferases (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cho, Kim, Jancarik, Yokota, Nguyen, Grigoriev, Wemmer and Kim2002) and ATP synthetase (Abrahams et al. Reference Abrahams, Leslie, Lutter and Walker1994). In our standard procedure, (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Olesen, Jensen, Møller and Nissen2006) the purified Ca2+-ATPase is prepared from SR vesicles by the extraction of extrinsic proteins (calsequestrin, M55 glycoprotein) with a low concentration of deoxycholate (Andersen et al. Reference Andersen, Lassen and Moller1985b). The purified membranes resulting from this treatment are used directly for crystallization after solubilization of the Ca2+-ATPase and lipids by a minimal amount of C12E8 in the presence of salt (KCl), buffer (Mops, pH 6·8) and activity preserving cryoprotectants like sucrose or glycerol. After the removal of insoluble and inactive ATPase residues by repeated centrifugation, screens are set up for crystallization by the hanging drop procedure, using polyethyleneglycol as the main precipitant (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Olesen, Jensen, Møller and Nissen2006). Three-dimensional crystals usually develop from appropriate incubations over a period of 1–10 days. Optimization of the crytallization process requires the use of additives like tert-butanol, dimethylsulfoxide or 3-methyl-5-pentanediol (MPD) and second detergents have also proven helpful (Laursen et al. Reference Laursen, Bublitz, Moncoq, Olesen, Møller, Young, Nissen and Morth2009). The crystals formed are typically very fragile and their diffractive properties upon mounting and flash cooling in liquid nitrogen are typically dependent on the slow evaporation of mother liquor until cryoprotecting conditions are reached which we regulate by the concentration of, e.g. cryoprotectant or salt in the reservoir fluid (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Møller and Nissen2004b). In a few cases, rapid soaking with cryoprotecting buffer has been possible (Laursen et al. Reference Laursen, Bublitz, Moncoq, Olesen, Møller, Young, Nissen and Morth2009). The procedure for cooling of the crystals at liquid nitrogen temperature is also important for the preservation of their structure and in certain cases has required precooling to 4°C before flash coling (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Møller and Nissen2004b).

Table 1. Important 3D structures of Ca2+-ATPase representative of well defined transport intermediates

* 10 mM Ca2+. ** EGTA.

In the procedure employed by Toyoshima's group, the Ca2+-ATPase is purified in a delipidated state from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of rabbit skeletal muscle after solubilization with C12E8 and affinity chromatography on a Reactive Red column (Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Nakasako, Nomura and Ogawa2000; Toyoshima & Nomura, Reference Toyoshima and Nomura2002). Crystallization proceeds after relipidation and dialysis against the media of appropriate composition, including the presence of ligands and stabilizers. We also in our repertoire employ affinity chromatography for the purpose of purifying Ca2+-ATPase produced by heterologous expression in yeast (Jidenko et al. Reference Jidenko, Nielsen, Sorensen, Moller, Le Maire, Nissen and Jaxel2005). In this case, the Ca2+-ATPase, with an added thrombin sensitive linker and biotin acceptor domain is bound to a streptavidin column, from which it is released by cleavage with thrombin. Then the Ca2+-ATPase, freed from its biotin acceptor domain, is further purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and finally relipidated after Amicon filter concentration by an addition of dioleoylphosphatidylcholine (DOPC). This procedure, by which up to two milligram quantities of Ca2+-ATPase can be purified after heterologous expression in 12-liter-yeast culture, has opened the way to study functional aspects in combination with crystallization of Ca2+-ATPase mutants (Marchand et al. Reference Marchand, Lund Winther, Holm, Olesen, Montigny, Arnou, Champeil, Clausen, Vilsen, Andersen, Nissen, Jaxel, Moller and Le Maire2008).

Following the lead of the early studies of Martonosi (Dux et al. Reference Dux, Pikula, Mullner and Martonosi1987) crystallization of E1 forms usually is performed in the presence of a high Ca2+ concentration (⩾10 mM), which is far above that required to saturate the Ca2+ transport sites, but which probably serves to stabilize nucleotide-binding (Picard et al. Reference Picard, Toyoshima and Champeil2006) or protein–protein contacts at the cytosolic domains in the crystal (Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Nakasako, Nomura and Ogawa2000 and pdb entries 1SU4 and 2C9M); while to obtain E2 conformations thapsigargin or other transmembrane-stabilizing inhibitors such as cyclopiazonic acid (Laursen et al. Reference Laursen, Bublitz, Moncoq, Olesen, Møller, Young, Nissen and Morth2009; Moncoq et al. Reference Moncoq, Trieber and Young2007; Takahashi et al. Reference Takahashi, Kondou and Toyoshima2007) or bistertiaryhydroquinone (BHQ) (Obara et al. Reference Obara, Miyashita, Xu, Toyoshima, Sugita, Inesi and Toyoshima2005), are often present together with EGTA to complex Ca2+. To obtain well-diffracting crystals, C12E8 is the detergent of choice, aided as mentioned above by the presence of small organic molecules as additives. In all crystallizations, membrane lipid is present, added either after delipidation of the sample or as native lipids preserved with the protein in the purified Ca2+-ATPase preparation after detergent solubilization. In contrast to most membrane proteins, the presence of lipid is an absolute requirement for the crystallization of Ca2+-ATPase, as it is in the formation of 2D crystals. Thus, Ca2+-ATPase crystallizes as a type-1 membrane protein (Michel, Reference Michel1990). In all likelihood, the phospholipid and detergent form a mixed detergent/lipid bilayer phase that embeds the Ca2+-ATPase transmembrane sector (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Olesen, Jensen, Møller and Nissen2006). This results in the formation of 3D crystals by the stacking of several bilayers on top of each other. An analysis of the crystal composition has indicated the presence of about 30 phospholipid molecules and 80 molecules C12E8 per ATPase monomer, which gives a hydrocarbon content similar to that of the lipid in the native membrane (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Olesen, Jensen, Møller and Nissen2006). Usually, neighboring layers of Ca2+-ATPase molecules are present in opposite orientation, resulting in the formation of alternating head-to-head and tail-to-tail contacts between the different layers, an organization favorable for avoiding steric interference among individual ATPase molecules and neutralizing asymmetric distribution of charges. Occasionally, we have detected a dimeric unit cell with the same polarity of the ATPase molecules; these are characterized by a slight angle between the axes of each monomer in the dimeric unit cell. Evidently, this arrangement is needed to avoid a steric clash between the more bulky cytosolic domains. From the rather peripheral contacts between the ATPase molecules that are characteristic of the crystals, artefacts arising from packing constraints are not likely to be of major concern. As with many other membrane proteins most problems in modeling arise from the difficulties to obtain an ordered and isotropic arrangement of the transmembrane region, which in our case is located within a lipid/detergent bilayer with fluidic properties. Nevertheless, the outline of the transmembrane amino acid residues can usually be deduced from the electron density maps, and in some cases the resolution of this region has been excellent, e.g. for Ca2+-ATPase stabilized by thapsigargin and BHQ (Obara et al. Reference Obara, Miyashita, Xu, Toyoshima, Sugita, Inesi and Toyoshima2005) and the E2-BeF3− structure (corresponding to the E2P ground state) (Olesen et al. Reference Olesen, Picard, Winther, Gyrup, Morth, Oxvig, Møller and Nissen2007).

2. The Ca2+-ATPase domain structures

We now turn to a descripton of the Ca2+-ATPase structure as it has emerged from the X-ray diffraction analysis. This has confirmed the previous evidence for a modular composition in terms of a number of domains with precisely defined functions whose interrelationships are coordinated by linkers between the cytosolic and membranous domains (Green & Stokes, Reference Green and Stokes1992; MacLennan et al. Reference Maclennan, Brandl, Korczak and Green1985; Møller et al. Reference Møller, Juul and Le Maire1996). The cytosolic domains are constituted by the nucleotide-binding (N) domain, the phosphorylation (P) domain, and an actuator (A) transduction domain. These are most clearly depicted in the open Ca2E1 form of the Ca2+-ATPase (pdb code 1SU4, Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Nakasako, Nomura and Ogawa2000), cf. Fig. 3. Via the S1–S6 linkers the cytosolic domains are connected with the membraneous (M-) domain, constituted by ten transmembrane segments (M1–M10) that harbor the two Ca2+ transport-binding sites.

Fig. 3. The first atomic resolution structure of SERCA (pdb code 1SU4) by Toyoshima et al. (Reference Toyoshima, Nakasako, Nomura and Ogawa2000) in the Ca2E1 open conformation with no ATP bound. Shown in transparent surface and cartoon with the A-domain in yellow, N-domain in red, P-domain in blue, helix M1–2 in purple, M3–4 in green, M5–6 in wheat and M7–10 in gray. The TGES motif is shown in spacefilling with C atoms in yellow, N atoms in blue and O atoms in red. The Ca2+ ions are shown in green spacefilling. The approximate position of the lipid bilayer membrane, surrounding the Ca2+-ATPase, is indicated in yellow.

Considering the Ca2+-ATPase as a pumping device, our review is built up in the following way: First, we review in this section the structure and function of each of its components (i.e. the domains) of the pump. In Section 3, we examine how the components of the pump are assembled to bring about the active transport of Ca2+ across the membrane. In Section 4, we review data related to the fine tuning (regulation) of the pump within a membraneous environment. Finally, in Section 5 we consider the energetic aspects of coupling of Ca2+ transport and ATP hydrolysis by the pump.

2.1 The nucleotide-binding domain

The nucleotide-binding N domain is located in the upper, cytoplasmic part of the Ca2+-ATPase molecule, further removed from the lipid membrane than the P-domain, with which it is closely connected via a hinge region, formed by residues 358–360 and 600–605 (with the DPPR motif present in the primary structure). The overall arrangement represents a Rossman fold formed by six α-helical segments and 13 antiparallel β-segments (Fig. 4a). The overall shape of the domain resembles that of a tophat, with the central portion formed by two of the helical segments (α2 and α4) and seven of the β-segments that line a halfbarrel structure, whereas the remaining helices and a number of loops and short antiparallel β-segments form a major part of the solvent exposed structure. The autonomous nature of the N-domain is indicated by the fact that it can be isolated as a watersoluble fragment by proteolytic cleavage, with the retention of both nucleotide-binding capacity (Champeil et al. Reference Champeil, Menguy, Soulie, Juul, De Gracia, Rusconi, Falson, Denoroy, Henao, Le Maire and Moller1998; Moutin et al. Reference Moutin, Rapin, Miras, Vincon, Dupont and Mcintosh1998) and, according to nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis (Abu-Abed et al. Reference Abu-Abed, Mal, Kainosho, Maclennan and Ikura2002), with a structural fold similar to that seen in the crystal structure. Similar findings have been obtained with the N-domain of Na+, K+-ATPase where the structure of the isolated fragment has been studied both by NMR (Hilge et al. Reference Hilge, Siegal, Vuister, Guntert, Gloor and Abrahams2003) and X-ray diffraction of crystals of the isolated N-domain (Håkansson, Reference Håkansson2003) or of the whole ATPase (Morth et al. Reference Morth, Pedersen, Toustrup-Jensen, Sorensen, Petersen, Andersen, Vilsen and Nissen2007; Shinoda et al. Reference Shinoda, Ogawa, Cornelius and Toyoshima2009). Despite appreciable differences in sequence and length of the solvent-exposed part, there is a surprising degree of similarity of the core structure among the N-domains of Ca2+-ATPase and Na+, K+-ATPase. The crystal structures of the N-domain of the whole ATPase molecule with bound AMPPCP (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Møller and Nissen2004b; Toyoshima & Mizutani, Reference Toyoshima and Mizutani2004), or with bound ATP by the non-phosphorylating D351A mutant (Marchand et al. Reference Marchand, Lund Winther, Holm, Olesen, Montigny, Arnou, Champeil, Clausen, Vilsen, Andersen, Nissen, Jaxel, Moller and Le Maire2008) shows that the nucleotide moiety of ATP is bound in a groove located at the lower end of the N-domain tophat, with the triphosphate part of the nucleotide located outside the groove, in the interphase between the N- and P-domains (Fig. 4b). Among the structural folds the α2 and α4-helix, together with the β7–β9 segments, are involved in the binding site of ATP which takes place by sandwiching of the adenine ring between the conserved Phe 487 and Lys 492 side chains against the Lys 515 and Thr 440/Glu 442 (α2) residues (Fig. 4b). The involvement of π–π contacts with Phe 487 is suggested by the staggered position of the phenyl ring with the adenine ring. The binding pocket is preformed and somewhat wider in the absence of bound nucleotide in the Ca2E1 form, while in the E2 form only side chain rotamers changes upon nucleotide binding, most notably Glu 439 (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Sorensen, Olesen, Moller and Nissen2006). Thus, only small conformational changes are required for adenosyl binding. The Lys 515 residue marks the start of a conserved KGAPE519 motif, which as a β-strand stretches from the upper part of the N-domain to the binding site; Lys 515 has been known for many years to be specifically modified by fluorescein isothiocyanate FITC (Mitchinson et al. Reference Mitchinson, Wilderspin, Trinnaman and Green1982), resulting in the disruption of nucleotide binding. Lys 515, interacts with the 6-amino group of the adenine ring and is close to Glu 442 with which it probably forms a strong ionic or hydrogen bond in the hydrophobic interior of the domain. Remarkably, all the residues involved in adenosine binding in the Ca2+-ATPase crystals are also conserved among other P-type ATPases, and their important roles in nucleotide binding and enzyme turnover is directly documented in site directed mutagenesis experiments (Clausen et al. Reference Clausen, Mcintosh, Vilsen, Woolley and Andersen2003).

Fig. 4. The N-domain, represented by the Ca2E1-AMPPCP structure (pdb code 1T5S). (a) Overall ‘tophat’ representation in cartoon showing the central core of seven β -strands surrounded by 6 α helices, peripheral β-strands, and loops. The AMPPCP molecule is shown in sticks. (b) close-up view of the nucleotide-binding site and the interactions of AMPPCP with Arg 560 and Phe 487 ring stacking with AMPPCP, together with other residues engaged in the formation of the adenosyl binding cavity.

The triphosphate part of the bound nucleotide, located at the border of the N-domain, forms a bent conformation, different from the elongated (energy minimized) equilibrium conformation of the nucleotide in solution. The structure of the Ca2E1:AMPPCP and E2:AMPPCP (Tg) crystals suggests that the bend is dependent on electrostatic interactions with Arg 560 (β12), a conserved and functionally important residue (Clausen & Andersen, Reference Clausen and Andersen2003) exposed on the lower surface of the N-domain, assisted by Leu 562 by the formation of a hydrogen bond with the 3OH′ hydroxyl group of ribose, according to IR spectral studies (Liu & Barth, Reference Liu and Barth2004). In addition, Glu 439 (α2), which is a predilection point for oxidative Fe2+ cleavage (Hua et al. Reference Hua, Inesi, Nomura and Toyoshima2002; Montigny et al. Reference Montigny, Jaxel, Shainskaya, Vinh, Labas, Moller, Karlish and Le Maire2004), has also been implicated in nucleotide binding, via a water coordinated Mg2+ binding site invoked during phosphorylation (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Møller and Nissen2004b). As a result of these interactions, the γ-phosphate is located rather close to the N-domain, but by the bending of the whole N-domain towards the P-domain it is also capable of interacting with the phosphorylatable Asp 351 residue in the Ca2+ bound E1 form via direct coordination of both to a Mg2+ ion further coordinated by Asp 703 and the carbonyl of Thr 353. In fact, the N- and the P-domains can be considered to be glued together or ‘cross-linked’ as a result of the ATP molecule interacting intimately with both domains (see the following section 2.2).

2.2 The phosphorylation domain

The phosphorylation (P) domain is composed of two different, but closely interacting parts of the Ca2+-ATPase polypeptide chain: An N-terminal and central part, comprising residues 330–357, a continuation of the cytosolar extension of the fourth membrane segment (S4) that is wrapped up in polypeptide from a more C-terminal part, comprised by residues 605–738. As shown in Fig. 5, with the Ca2+-ATPase molecule placed en face as in Fig. 3, the N-terminal peptide (green part) starts at the bottom of the P-domain, runs forward to the front of the domain to make a 90° bend followed by a short α-helical stretch around Glu-340 (P-α1). Then the chain submerges into the domain to form a central β-strand of the P-domain ending with the phosphorylation motif (349CSDKTGTLT357). The larger C-terminal part of the P-domain (sequence 605–738) is formed by polypeptide that follows after the interposed N-domain (sequence 361–600), which is linked to the P-domain with two short hinges (358TNQ and 601DPPR). The C-terminal part of the P-domain surrounds the phosphorylation motif as two hemispherical α, β-structured Rossman folds (comprising residues 605–679 and 680–738), which we shall refer to as subdomains P-I (yellow) and P-II (blue), respectively. Among these, P-I has the more irregular α3β3 Rossman fold, starting with a helical segment that stretches forward from the hinge region with the N-domain, followed by a short loop and a β-strand (residues 620–624), which ends at the 625TGD motif that forms an integral part of the phosphorylation site. The 601–624 residues are highly conserved, and together with the 601DPPR motif of the hinge region probably important for the proper coordination of events in the N- and P-domains during the ATP phosphorylation process. As another important feature, the P-β2 strand 620–624 is engaged in close contact with the P-β1 strand of the phosphorylation motif (residues 347–351), which on the contralateral side is engaged in similar contacts with the P-β5 strand of P-II. This three-stranded β-pleated structure is probably important for stabilization of the central P domain structure that at the upper end contains the phosphorylation site that is located in a cavity between a number of important residues for the phosphorylation reaction, as shown in Fig. 5 and discussed below.

Fig. 5. The phosphorylation domain with the central β-stranded core, formed by the N-terminal 330–357 P-αβ peptide shown in cartoon (green) with the phosphorylatable Asp 351 at the top of the domain, shown in sticks, and the two C-terminal P-I (605–679) and P-II (680–738) subdomains, also shown in cartoon and colored in yellow and blue, respectively, together with some of the residues important for phosphorylation (the 625TGD motif, Asp 703, and Asn 706 shown in sticks). The representation is based on the 1T5S structure.

In P-II, the polypeptide forms a regular Rossman fold, neatly arranged side by side as three consecutive αβ parallel running folds. This part of the ATPase contains the long and extremely well-conserved signature motif of P-type ATPases, starting with 699AM(V)TGDVN and ending with GIAMG721. Like the phosphorylation motif, this sequence is diagnostic of P-type ATPases and, as part of a central core (Section 2.5), vitally important for energy transduction; it contains two aspartic acid residues (Asp 703 and Asp 707) of which the former is coordinated with Mg2+ during the phosphorylation process. P-II also contains the catalytically active Lys 684, which in conjunction with Mg2+ is required to abstract negative charge during the phosphorylation process (see below).

Compelling evidence has been presented to include P-type ATPases as a member of the HAD (haloacid dehalogenase) superfamily (Aravind et al. Reference Aravind, Galperin and Koonin1998; Stokes & Green, Reference Stokes and Green2000). In addition to the structurally well-characterized archaetype member, Pseudomonas L-2 haloacid dehalogenase, from which the family derives its name, this group of proteins includes a number of prokaryotic and watersoluble phosphatases and phosphotransferases (Collet et al. Reference Collet, Gerin, Rider, Veiga-Da-cunha and Van Schaftingen1997; Koonin & Tatusov, Reference Koonin and Tatusov1994). The family also includes a group of bacterial chemotaxic protein regulators like CheY (Bellsolell et al. Reference Bellsolell, Prieto, Serrano and Coll1994; Stock et al. Reference Stock, Martinez-Hackert, Rasmussen, West, Stock, Ringe and Petsko1993). Most of these proteins (although not the haloacid-dehalogenase that has given the family its name) are characterized by the formation of covalently bonded aspartylphosphate intermediates during the reaction cycle. With respect to the catalytic mechanism, despite an overall low degree of homology, sequence comparisons have suggested that the active site in all cases is constituted by conserved residues originating from three different parts of the polypeptide chain (Aravind et al. Reference Aravind, Galperin and Koonin1998; Ridder & Dijkstra, Reference Ridder and Dijkstra1999), and these assignments are supported by the available 3D structures of CheY (Bellsolell et al. Reference Bellsolell, Prieto, Serrano and Coll1994; Stock et al. Reference Stock, Martinez-Hackert, Rasmussen, West, Stock, Ringe and Petsko1993) and phosphoserine phosphatase (Peeraer et al. Reference Peeraer, Rabijns, Verboven, Collet, Van Schaftingen and De Ranter2003; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Kim, Jancarik, Yokota and Kim2001). These common features include: in Domain I, a phosphorylation motif like the ATP phosphorylatable aspartate residue (Asp 351 in Ca2+-ATPase); in Domain II, a catalytically active serine or threonine residue (represented by the threonine residue in the 625TGD motif in P-I of Ca2+-ATPase and other P-type ATPases); and in Domain III, a lysine residue (Lys 684 in P-II and homologous lysine residues in other P-type ATPases) together with two aspartate residues in the C-terminal half of P-II, at least one of which is implicated in the binding of Mg2+ and represented by Asp 703 in Ca2+-ATPase (Ridder & Dijkstra, Reference Ridder and Dijkstra1999; Stock et al. Reference Stock, Martinez-Hackert, Rasmussen, West, Stock, Ringe and Petsko1993). The reaction leading to the formation of the aspartylphosphorylated intermediate involves a nucleophilic association mechanism between the γ-phosphate of ATP and the susceptible aspartate residue, a reaction that is assisted by the above-mentioned conserved residues in Domains II and III and by Mg2+ (Ridder & Dijkstra, Reference Ridder and Dijkstra1999). With respect to Ca2+-ATPase, the phosphorylation reaction can be described by the following steps: (1) Docking of the γ-phosphate from the ATP bound in the E2 conformation into the cavity forming the phosphorylation site between P-I and P-II. This reaction is dependent on a concomitant change in the conformation of ATPase to E1 caused by the binding of Ca2+ to the membrane domain and withdrawal of the A-domain from its interaction with the phosphorylation site (Section 3.1). (2) Interaction of the γ-phosphate with Asp 351, forming first a phosphorylation transition state intermediate and then a covalent bond with carboxylate Asp 351 concomitant with cleavage of the β, γ phosphate bond of ATP. For these crucial reactions, four crystal structures are available: (i) E2:AMPPCP, with stabilization by thapsigargin (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Sorensen, Olesen, Moller and Nissen2006); (ii) Ca2E1:AMPPCP, representing the nucleotide bound state prior to phosphorylation activated by Ca2+ binding at the transport sites (Picard et al. Reference Picard, Toyoshima and Champeil2006; Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Møller and Nissen2004b; Toyoshima & Mizutani, Reference Toyoshima and Mizutani2004); (iii) the Ca2E1–ADP–AlF4− structure, representing the phosphorylated transition state (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Møller and Nissen2004b) and (iv) the structure of Ca2E1–P:AMPPN, representative of the genuine [Ca2]E1~P phosphoenzyme with bound ADP (Olesen et al. Reference Olesen, Picard, Winther, Gyrup, Morth, Oxvig, Møller and Nissen2007). Figure 6 shows the details of the phosphorylation reaction as they can be described on the basis of these structures. In Fig. 6 a, AMPPCP, as an analog of ATP, loosely interacts with the periphery of the P-domain, corresponding to the TGD motif and Arg 678. In Fig. 6b the negatively charged γ-phosphate residue, after the Ca2+-induced change in conformational state from E2 to E1, has moved close to the carboxylate group of Asp 351, stabilized by electrostatic and hydrogen bond interactions with the side chains of Lys 684 and Thr 625. Furthermore, divalent cation mediates contact between the carboxylate group of Asp 351 and γ-phosphate; but note that in the crystal structure it is Ca2+ which replaces the physiologically relevant Mg2+, due to the high Ca2+ concentration used in crystallization of E1 forms (Picard et al. Reference Picard, Jensen, Sorensen, Champeil, Moller and Nissen2007). The divalent metal ion is octahedrally coordinated by further ligation with the carbonyl backbone of Thr 353, the carboxylate group of Asp 703, and a water molecule. All these interactions are retained in the Ca2E1–ADP–AlF4− structure (Fig. 6c), where the central Al3+, surrounded by the planar arranged F- groups functions as a mimick of phosphoryl transfer in the transition state, as evidenced by the fact that it is linearly and equidistantly (~2 Å) interposed between the β-phosphate of ADP and the carboxyl group of Asp 351. Thus, the structure can be taken to represent an intermediate stage in the transfer of γ-phosphate from ATP to the accepting Asp 351 carboxylate group, according to an SN-2 associative nucleophilic reaction mechanism (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Møller and Nissen2004b). The structure reveals how the opposing electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged nucleotide and Asp 351 carboxylate are partially overcome by an abstraction of negative charge by the closely positioned Lys 684 residue, and by divalent cation (in which structure Mg2+ replaces Ca2+) that coordinates with both the Asp 351 carboxylate and the γ-phosphate group. This structure of the environment for the transfer of the covalent phosphate bond from nucleotide to Asp 351 is in good agreement with deductions previously drawn from studies involving mutation of residues critical for the ATP phosphorylation reaction (Andersen, Reference Andersen1995a; Clausen et al. Reference Clausen, Mcintosh, Woolley and Andersen2001; McIntosh et al. Reference Mcintosh, Clausen, Woolley, Maclennan, Vilsen and Andersen2004). Additionally, Lys 352, while not directly involved will support a favorable electrostatic environment for the phosphorylation reaction. It has also been suggested that Lys 352, by inducing a single helix at the end of the phosphorylation motif (353TGTLT) exposes the main chain carbonyl Thr 353 for ligation with Mg2+ (Jørgensen et al. Reference Jørgensen, Hakansson and Karlish2003).

Fig. 6. Changes in the phosphorylation P-site and nucleotide-binding N-site during phosphorylation with ATP. (a) E2:ATP represented by the E2:AMPPCP structure (pdb 2C88); (b) Ca2E1:ATP represented by the Ca2E1:AMPPCP structure with Ca2+ replacing the physiologically bound Mg2+; (c) Phosphorylation transition state, [Ca2]E1-P-ADP, represented by the [Ca2]E1-AlF4−-ADP structure, (pdb 1T5T); (d) [Ca2]E1~P:ADP, represented by the [Ca2]E1~P:AMPPN structure (pdb 3BA6) with Ca2+ replacing the physiologically relevant Mg2+. ATPase residues are shown in white sticks with N and O atoms colored blue and red, respectively. AMPPCP, ADP and AMPPN are shown in sticks colored as in Fig. 3. Water molecules are shown in red spacefilling and Mg2+ and Ca2+ in green spacefilling.

Other unique features of the transition state are that in this state the side chains of Thr 353 and Thr 625 stabilize the β- and γ-phosphates as they arrange ATP for phosphorylation of Asp 351. Furthermore, an additional Mg2+ cation is found in the [Ca2]E1–AlF4−-ADP structure, bound to the α, β-phosphate of ADP, Arg 678 and Asp 627 of the TGD motif. It can be noted that in the [Hn]E2:AMPPCP form a Mg2+ ion also interacts with the α, β-phosphate of the bound trinucleotide, although with different residues on the ATPase due to movements of the cytosolic domains associated with the E2→Ca2E1 transition (see the previous section on the N-domain). The role of the second bound divalent cation, which during phosphorylation is only associated with the transition state, will further aid to lower the activation energy required for the transfer of the phosphate from ATP to Asp 351 the ADP leaving group. Finally, Fig. 6d shows the structure of the fully phosphorylated Ca2+-ATPase, obtained by the use of the slowly hydrolyzed nucleotide analog, AMPPNP which stabilized the Ca2+-ATPase in the Ca2E1~P:AMPPN nucleotide bound form (Olesen et al. Reference Olesen, Picard, Winther, Gyrup, Morth, Oxvig, Møller and Nissen2007). In this structure, the formation of a covalent phosphoaspartyl bond was documented by mass spectrometry of a proteolytic fragment. The difference Fourier maps were consistent with a further shift in the electron density of the γ-phosphate towards the Asp 351 side chain, compared with the aluminium fluoride mimic of the transition state. Otherwise there were only slight changes in the topology of the phosphorylation site, except for the disappearance of the second bound Mg2+, and a slight removal of Arg 560, with the bound dinucleotide (AMPPN), relieved from the interaction with Arg 678.

Of further interest for the understanding of the phosphorylation reaction we have found in studies of the D351A mutant (which does not hydrolyze ATP) that ATP is bound with the same characteristic bend of the triphosphate moiety as AMPPCP (Marchand et al. Reference Marchand, Lund Winther, Holm, Olesen, Montigny, Arnou, Champeil, Clausen, Vilsen, Andersen, Nissen, Jaxel, Moller and Le Maire2008). The presence of a carbon atom bridging the β- and γ-phosphate in AMPPCP thus does not affect the conformation of bound ATP. The binding region was indistinguishable from that of the wild-type, except for the replacement of Asp 351 with alanine. Furthermore, in agreement with previous studies (McIntosh et al. Reference Mcintosh, Woolley, Maclennan, Vilsen and Andersen1999; Pedersen et al. Reference Pedersen, Rasmussen and Jorgensen1996), we confirmed that the mutant binds ATP with a considerably higher affinity than the wild type, consistent with the disappearance in the mutant of opposing negative electrostatic interactions imparted by the negatively charged nucleotide phosphate and phosphorylation site in the wild-type ATPase (Marchand et al. Reference Marchand, Lund Winther, Holm, Olesen, Montigny, Arnou, Champeil, Clausen, Vilsen, Andersen, Nissen, Jaxel, Moller and Le Maire2008).

Despite the pronounced similarities in the overall structure of ATPase with bound nucleotide (Fig. 6b) and the transition state (Fig. 6c) there are distinct differences in the biochemical properties of these complexes in the native membraneous states: while the [Ca2]E1-AlF4−-ADP form stably occludes Ca2+, this is not the case for ATPase with bound AMPPCP which also, in contrast to the [Ca2]E1-AlF4−-ADP form, is susceptible to proteolytic degradation and sulfhydryl modification (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Møller and Nissen2004b) and to reaction with surface-bound antibodies. Thus, while the ATPase with bound MgAMPPCP appears to be present in the native membranes in a dynamically fluctuating state, this is not the case for the [Ca2]E1-AlF4− MgADP intermediate. As we have noted previously, global immobilization of the whole ATPase molecule is probably a necessary requirement to maintain the stringent requirements for exact positioning of the bonds in these transition state complexes (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Møller and Nissen2004b). However, it has been pointed out that at least part of these differences may be related to the differences in the properties of Ca2+-ATPase, arising from the high concentration of Ca2+ used for crystallization (Picard et al. Reference Picard, Toyoshima and Champeil2005) that result in the binding of Ca2+ instead of Mg2+ at the phosphorylation site (Picard et al. Reference Picard, Jensen, Sorensen, Champeil, Moller and Nissen2007). Nevertheless, the Ca2+-occlusion of ATPase imparted by complexation with ADP-AlF4− (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Møller and Nissen2004b; Troullier et al. Reference Troullier, Girardet and Dupont1992) or CrATP (Coan et al. Reference Coan, Ji and Amaral1994; Vilsen & Andersen, Reference Vilsen and Andersen1992) clearly single out these intermediates as stable structures where Ca2+ is not in communication with the solutions on either the cytosolic or the luminal side of the membrane.

2.3 The A domain

The N-terminal A- or actuator domain has been described as having a jelly-roll appearance, made up of a central part (comprising amino acid residues 122–232) and capped by the N-terminal 1–37 residues (Inesi et al. Reference Inesi, Ma, Lewis and Xu2004; Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Nakasako, Nomura and Ogawa2000). The intervening part of the sequence (residues 38–121) forms the M1/M2 spans and their cytosolic A-M1 and A-M2 extensions. In the older literature, the A-domain is often referred to as the β- or translocation domain, due to a high predicted content of β-structure (Green & Stokes, Reference Green and Stokes1992; MacLennan et al. Reference Maclennan, Brandl, Korczak and Green1985) and suspected essential role in translocation, mainly based on proteolytic evidence (Imamura & Kawakita, Reference Imamura and Kawakita1989; le Maire et al. Reference Le Maire, Lund, Viel, Champeil and Møller1990; Møller et al. Reference Møller, Lenoir, Marchand, Montigny, Le Maire, Toyoshima, Juul and Champeil2002). As we shall see, all these designations aptly describe the structure and function of the domain. Nine, mostly antiparallel small- and medium-length β-stretches are distributed evenly over the whole central part of the domain, joined by loops and with an almost complete absence of helical structure. Conversely, the N-terminal cap (the existence of which was unknown before it was revealed by the X-ray structures) contains two helices, joined by loops, – and no β structure (Fig. 7a).

Fig. 7. The A-domain. (a) Schematic representation showing the 9 β-strands, formed by residues 122–232 of the central part, capped by the 1–35 N-terminal residues (colored in red) with 2 helical segments. The central part is composed of an outer subdomain (green colored), and an inner (blue colored) well-conserved subdomain, with an appendage (yellow colored), carrying the catalytically important 181TGES loop. (b) The three dimensional structure of the A-domain, shown in cartoon in the E2-P transition state (pdb code 3B9R) (c) close-up view of the interaction of the TGES loop with the phosphorylation site with AlF4− mimicking the phosphate (pdb code 3B9R), coordinated by Mg2+ and a water molecule activated for SN-2 base catalysis by coordination with Glu 183 and Thr 181.

Probably, the predominant β-structure configuration combines an overall sturdy and stable structure of the A domain with local flexibility imparted by the loops and sparse helical regions for interactions of functional importance. A close inspection of the 3D structure (Fig. 7b) indicates a bipartite constitution of the domain in an inner and outer subdomain along different lines than suggested by the primary and secondary structure. The inner part starts with a 160PAD turn motif and ends at Ile 232 at a well-characterized V8 proteolytic cleavage site (le Maire et al. Reference Le Maire, Lund, Viel, Champeil and Møller1990) while the outer part is made up of residues 122–159 in addition to the N-terminal cap. The division between the outer and inner subdomains is demarcated by the last β-strand of the domain (219ALGIVAT), which like a string around a parcel slings around and demarcates the border between the outer and the inner subdomains. The inner subdomain contains the 181TGES motif essential for hydrolysis of E2P and other residues important for modulatory regulation of the dephosphorylation reaction (Section 4.2). The outer subdomain is connected with the M1 and M2 membrane pairs via the A-M1 and A-M2 linkers which, as discussed in Section 3.2, together with the C-terminal A-M3 linker are of crucial importance for the organization and open/closed state of the two intramembraneous Ca2+/H+ binding sites towards the lumen or the cytosol.

A characteristic feature of the Ca2E1 structure seems to be that the A-domain in this state only weakly interacts with the P-domain. This is unlike the situation in any nucleotide bound or phosphorylated states where the A-domain interacts with the P- and N-domain in ways that are critically important for ATP phosphorylation and dephosphorylation as well as for ion translocation. Changes in the interactions between the cytosolic domains of these forms are dependent on rotatory movements that the A domain perform during the functional cycle along the periphery of the P-domain in directions parallel and normal to the membrane. Thus, in the transition from E2 to the E1 states the A-domain rotates counterclockwise away from the phosphorylation site (Toyoshima & Nomura, Reference Toyoshima and Nomura2002) where it blocks for ATP phosphorylation of the P-domain (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Sorensen, Olesen, Moller and Nissen2006). The details of these processes are most appropriately postponed until section 3 for a description of the structural changes that the ATPase as a whole undergoes in relation to Ca2+ translocation and proton exchange. Instead, we consider here the involvement of the A-domain in the dephosphorylation of the ATPase in the E2P state. This occurs via an appendage (knob) on the inner subdomain of the A-domain that carries the catalytically active 181TGES motif which interacts with the phosphorylated Asp 351 residue during E2P dephosphorylation. The motif is present as a loop on top of the appendage, stabilized by two short antiparallel β-sheets (A-β5 (174–176) and A-β6 (187–188)). The details of the dephosphorylation reaction have been studied with the aid of two structures, one in which AlF4− has been complexed with ATPase in the E2 state, as a mimick of the E2P transition state (Olesen et al. Reference Olesen, Sørensen, Nielsen, Møller and Nissen2004), and another one with the ATPase complexed with MgF42−, as a mimick of the E2⋅Pi product state with non-covalent bound phosphate (Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Nomura and Tsuda2004). As can be seen from Fig. 7c with the E2P transition state analog the TGES motif of the A-domain has moved in close apposition to the phosphorylation site. Here, the Glu 183 residue of the motif with the aid of a bridging water molecule interacts with the AlF4− group. The bridging water molecule is in position for an in-line attack by an associative SN-2 mechanism where Glu 183 acts as a general base catalyst by an abstraction of proton from the bound water molecule. This role of Glu 183 in hydrolytic dephosphorylation of E2P was confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis (Clausen et al. Reference Clausen, Vilsen, Mcintosh, Einholm and Andersen2004). Additional mutagenesis studies have also supported the decisive role of the other residues of the motif, in particular those of Thr 181 and Gly 182, in supporting the dephosphorylation reaction (Anthonisen et al. Reference Anthonisen, Clausen and Andersen2006).

In the concomitantly published studies with MgF42− as a mimick of the E2-Pi product state, the central Mg2+ ion was also found to interact with Asp 351 and Glu 183 in a similar way as AlF4− (Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Nomura and Tsuda2004). In both cases, thapsigargin was present as a stabilizing ligand, but subsequent E2 structures of E2-AlF4− (Olesen et al. Reference Olesen, Picard, Winther, Gyrup, Morth, Oxvig, Møller and Nissen2007) and E2⋅MgF42− (Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Norimatsu, Iwasawa, Tsuda and Ogawa2007) without thapsigargin indicates that this ligand is bound without any appreciable effect on the ATPase crystal structure.

2.4 The membraneous domain

The lipid-embedded membrane domain consists of ten helical transmembrane segments (M1–M10) that together form an ellipsoidal cylindrical structure, with cross-sectional diameters ranging from about 35–40 Å and with a height of around 25–30 Å, corresponding to the distance between the cytosolic and intraluminal lipid interphases, as estimated from the location of weak electron density attributable to the phospholipid head groups, and of the tryptophan- and arginine residues clustering at the phospholipid/water interphase. The transmembrane helices can be subdivided into three subdomains: of which two are N-terminal, formed by the M1/M2 and M3/M4 transmembrane pairs, respectively, whereas the third one, M5–M10, is C-terminal and forms a closely knitted and intertwined helical bundle (Fig. 8a). In the E1 conformation, Ca2+ is bound to the ATPase at two binding sites located between the centrally located M4, M5, M6 and M8 transmembrane segments (Obara et al. Reference Obara, Miyashita, Xu, Toyoshima, Sugita, Inesi and Toyoshima2005; Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Nakasako, Nomura and Ogawa2000). Ca2+ binding occurs by coordination with carboxylic amino acid side chains and main chain carbonyl groups (Fig. 8c), in a similar way as in watersoluble Ca2+-binding proteins such as calmodulin, troponin C and parvalbumin. At site I, Ca2+ is heptacoordinated with the carboxylic groups of Glu 771 (M5), Asp 800 (M6) and Glu-908 (M8), and with main chain carbonyl groups, located at Asp 768 (M5) and Thr 799 (M6), plus 2 H2O; and at site II with Glu 309 (bidentate coordination) and main chain carbonyl groups at Val 304, Ala 305 and Ile 307 (all located on M4) together with the carboxyl group of Asp 800 carboxyl and main chain carbonyl Asn 796 (both on M6). Here they are placed in two cavities surrounded in a cage-like structure by a network of hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues and some bound water molecules, and cooperating via Asp 800 that is bound to both Ca2+ ions (Obara et al. Reference Obara, Miyashita, Xu, Toyoshima, Sugita, Inesi and Toyoshima2005; Toyoshima et al. Reference Toyoshima, Nakasako, Nomura and Ogawa2000). Overall, the two bound Ca2+ ions, coordinated with four carboxyl groups in their unprotonated state can be considered to form an electroneutral complex inside the membrane environment, before translocation to the other side of the membrane.

Fig. 8. The Central Core and the intramembranous Ca2+ binding sites. (a) Overall representation of SERCA in cartoon and ribbon, with the central core ‘domain’ shown in surface representation, with M4 and M5 (the spine) colored in blue and orange, respectively, and the C-terminal part of the phosphorylation domain in yellow. M1–M2 colored purple, M3–M4 green and M6–10 in wheat. The Ca2+ ions are shown in green spacefilling. AMPPCP and the TGES motif are shown in spacefilling. (b) The isolated Central Core-domain as shown in (a) emphasizing the closed structure formed by the three components and clear connection between the cation binding sites and the phosphorylation site. (c) Close-up view of the Ca2+ binding sites between M4, M5, M6 and M8 helices and with key coordinating side chain residues shown in sticks. Water molecules are shown in red spacefilling. Figs 8a–c are based on the [Ca2]E1:AMPPCP structure (pdb code 1T5S).

The close topological relation between the two bound Ca2+, and their interconnection via a common coordinating carboxylate residue (Asp 800) raise intriguing questions concerning cooperativity (Forge et al. Reference Forge, Mintz and Guillain1993; de Foresta et al. Reference De Foresta, Henao and Champeil1994; Inesi et al. Reference Inesi, Kurzmack, Coan and Lewis1980), as well as their sequential binding (Orlowski & Champeil, Reference Orlowski and Champeil1991a), and their release on the other side of the membrane as discussed in section 3.2. For accurate positioning of the liganding residues with respect to the binding of Ca2+ the helical structure of the involved transmembrane segments is unwound, corresponding to the location of the liganding residues around the Glu 309, Glu 771 and Asp 800 residues. In particular, M4 is kinked at a conserved proline residue found in all P-type ATPases (Axelsen & Palmgren, Reference Axelsen and Palmgren1998; Møller et al. Reference Møller, Juul and Le Maire1996). These helical interruptions, so-called Schellman motifs and their dynamic properties were first detected by NMR structural analysis of synthetic transmembrane peptides of M6 (Soulie et al. Reference Soulie, Neumann, Berthomieu, Moller, Le Maire and Forge1999) and M5 (Nielsen et al. Reference Nielsen, Malmendal, Meissner, Moller and Nielsen2003). As a result of the possibilities for bending and rotation of the amino acid chains provided by these motifs they easily adjust the position of ligating groups to optimize Ca2+ binding, a process with profound consequences for the conformational changes and energetic aspects associated with ion translocation across the membrane (sections 3 and 5).

2.5 Central core: the ‘Fifth’ ATPase domain