On Good Friday of 1973, members of San Francisco's homosexual community staged a public demonstration amidst the skyscrapers in the business district.Footnote 1 Shen Hayes, described as a “frail nineteen-year-old,” claimed to embody the suffering of the city's gay population. Hayes dragged a telephone pole “cross” on his back while throngs of protesters cheered and chanted. The local minister leading the action likened gays’ lack of rights to murder, and the caption accompanying Hayes’ photo in the newspaper claimed that he and other gay Californians had been “crucified.”Footnote 2 Despite, despite the protest's religious intensity, its objective was secular. Activists had convened to oppose discrimination against those workers whom Pacific Telephone & Telegraph (PT&T) had labeled “manifest homosexuals”: employees and job applicants who either claimed or seemed to be gay.Footnote 3

Despite facing such activist pressure, PT&T did not recognize its workers’ right to enact or imply a gay identity on the job. Whereas its parent AT&T had reached a landmark $38,000,000 settlement with women and minorities alleging systemic sex and race discrimination that same year, the company openly defended its policy of denying employment to workers who did not fit heterosexual norms.Footnote 4 A PT&T executive who witnessed the Good Friday demonstration said that the protestors he saw in “unisex dress…looked like maniacs.” By contrast, he observed, the “more conventionally dressed participants…looked like human beings.”Footnote 5 When questioned by the Advocate, PT&T official Jack Fiorito acknowledged that the company likely employed many gays who successfully hid their sexual orientation; PT&T's policy was aimed at overt expressions of homosexuality and gender nonconformity. He explained, “If an applicant tells me, ‘I am a homosexual,’ he is saying, ‘Well, here I am. What are you going to do about it?’ We judge that as a behavior characteristic that does not meet our employment standards. Why does he have to say that? We don't ask that question.” Further, although the simultaneous women's lawsuit successfully pressured the company to stop treating sex as a relevant employment characteristic, PT&T officials claimed that the company would be similarly vulnerable to costly legal struggles if disgruntled customers encountered open or suspected gay workers. Fiorito explained, “All it takes is one screaming liberal to go to a customer's home and to in any way offend that customer and the lawsuits would never stop.”Footnote 6 To PT&T, outward expressions of gender nonconformity and homosexuality signaled deviance, irresponsibility, political radicalism, and unfitness for employment, creating a legal liability for the company.Footnote 7

The 1973 Good Friday protest against PT&T was a single moment in activists’ decades-long campaign to expand gender and sexual diversity in the American workplace. Starting in the 1950s, homosexuals waged a multifront struggle for the right to express a gay identity at work. Their activism was coterminous with similar workplace rights campaigns fought by women and racial minorities; however, it necessarily diverged from those struggles. Women and minorities who faced discrimination because of race or biological sex won explicit new protections under Title VII in 1964. Therefore, challenging discrimination against women and minorities increasingly required leveraging existing abstract legal rights into the kinds of substantive gains women and minorities had won from AT&T.Footnote 8 By contrast, gay rights advocates had to convince courts, legislators, and employers of their right to be open and themselves. Further, whereas gay men and lesbians alike prioritized fighting workplace discrimination, they held different conceptions of the problem and its solution. The contemporary flourishing of lesbian feminism, lesbians’ simultaneous experience of sexism and homophobia, and the diverse priorities of lesbians’ law-oriented organizations put gay men at the front lines of struggles for workplace integration.Footnote 9

In California, the epicenter of the gay employment rights movement, activists conceived of sexual orientation discrimination as a new legal and social harm. They created job training and placement services, built coalitions with labor unions, staged public protests to embarrass businesses and shape consumer behavior, lobbied government agencies to add sexual orientation clauses to existing workplace equality laws, and argued in court that the sex discrimination provisions of state and federal laws should be reinterpreted to include sexual orientation. Their fundamental claim was that a worker's gender and sexual orientation were irrelevant to his or her ability to perform a job, but that the freedom to signal those identities was an essential element of workplace equality.Footnote 10 Therefore, whereas gay rights activists sought the substantive equality—removal of barriers to jobs as well as more representation therein—pursued by women and racial minorities, they also framed a more tolerant workplace culture in which they could safely come out as a state-protected entitlement. In so doing, they sought to capitalize on the political climate of expanding popular rights to social welfare, freedom of expression, and self-determination.Footnote 11 They found some local success against city governments and individual employers and in state courts. However, by the early 1980s, the combination of defeated state and federal campaigns, homophobic grassroots conservatism, and the burgeoning AIDS crisis stymied and shifted the focus of the movement for gay rights at work.Footnote 12

An examination of struggles for gay workplace rights in California challenges existing narratives that divide the postwar gay rights movement into distinct and dissimilar eras animated by the tension between activists who prioritized integration and state-protected rights and those who fought for liberation from societal norms and institutions. According to scholars, liberationist activists displaced their more moderate counterparts at the vanguard of gay politics in the late 1960s until their energy dissipated and the civil rights impulse recaptured the movement in the mid-1970s.Footnote 13 However, gay workplace rights campaigns illuminate bedrock consistencies among gay activists across those tumultuous and transformative years. For whereas liberation infused gay politics with innovative claims and tactics, the fight for workplace rights took new forms, but remained central to gay activism. Even liberationists who saw themselves as part of the radical counterculture channeled the street politics and cultural objectives of gay liberation into viable workplace rights claims, perceived the state as a potential ally, and collaborated with more moderate law-oriented groups toward that objective. Further, although the liberationist impulse weakened after several years, gay plaintiffs wove liberationists’ demands for freer gender expression into their workplace rights claims before state and federal courts in the later 1970s. Gay rights activists adopted a range of tactics, but they shared the objective of a more open workplace, and their arguments were successive rather than isolated. Therefore, DeSantis v. PT&T and Gay Law Students Association v. PT&T, the era's most significant court cases to challenge gay workers’ exclusion from workplace protections—both decided in California in 1979—represented not the spontaneous complaints of a few disgruntled workers, but the culmination of years of grassroots activism, collaboration, and legal strategizing that embodied some of the most universal and consistent claims at the heart of the modern gay rights movement.Footnote 14

Further, analysis of the movement for gay rights at work illuminates the challenges of breathing life into new sex equality laws. In the mid-1960s, a wave of federal provisions banned discrimination on the basis of a worker's sex, race, religion, and national origin.Footnote 15 Studies of this era tend to emphasize workers’ successful identity-based rights claims, landmark legal victories that gave force and teeth to antidiscrimination provisions, and the resulting spread of workplace equality. Such accounts tend to blame the swelling grassroots conservatism of the late 1970s and the Reagan revolution of the 1980s for setting the outer limit of workers’ progress.Footnote 16 Gay rights claims and their outcomes bring this narrative into question. Like women and minorities, gay workers sought to capitalize on the climate of expanding identity-based rights in the aftermath of new laws.Footnote 17 They attempted to stretch nascent workplace discrimination provisions such as Title VII to fit their specific needs, arguing that sexual orientation was like sex: an immutable identity rather than an element of personal style or behavior that could be forcibly concealed in the interest of conformity or employer preference. In claiming the right to be openly gay at work, these activists reframed access, substantive inclusion, and workplace culture that welcomed and affirmed sexual diversity as equally significant rights that merited state enforcement. Therefore, the promise and applicability of Title VII were contested questions, not foregone conclusions.Footnote 18

However, the law proved to be more of a stumbling block than a stepping stone to equality, because gay attempts to reach beyond isolated local protections and win workplace rights from courts and state legislatures were largely unsuccessful. Judges evaluated gay workplace rights claims within frameworks already defined and interpreted in terms of women, and ultimately rejected gay workers’ varied attempts to prove that sexual orientation discrimination was a kind of discrimination based on sex. Therefore, gay activists’ attempts to gain new protections yielded the devastating unintended outcome of strong new legal precedents articulating profound differences between gay rights and women's rights. In so doing, courts effectively severed sex from gender and sexual orientation before the law and reinforced notions of sex as biological and natural, unlike gender and sexual orientation, which—akin to political speech—were enacted rather than essential, and, therefore, involved some element of deliberateness and choice.Footnote 19

This outcome yielded profound consequences for the gay rights movement and the American workforce. Certainly, such defeats helped gay activists to remain a coherent minority and spared gay workers the frustrating “hollow hopes” of courtroom victories that failed to yield substantive change.Footnote 20 However, by denying to gays and lesbians the legal protections that provided women and racial minorities a path to good jobs, such court decisions shifted the terrain of gay rights activism to battles for local gains and cultural change and accelerated the divergence between the movement for gay rights and those of other minorities.Footnote 21 Further, this result also enabled conservative arguments that homosexuality was an issue of immorality rather than identity—and could therefore be suppressed or even eradicated—as well as contributed to the continuing subordination of workers embodying feminine characteristics, whether male or female. An examination of the growth, aspirations, and outcomes of the movement for gay employment rights reveals that the 1970s was a turning point in the legal status of female, racial minority, and gay workers alike, but with increasingly different, although intertwined, results.Footnote 22

* * *

In the first half of the twentieth century, self-aware gay communities formed in cities throughout the United States even as the growing federal state penalized homosexuality.Footnote 23 By mid-century, gay men and women increasingly found each other, conceived of themselves as a distinct social group, and began to advocate for change. Organizations such as the Mattachine Society, founded in Los Angeles in 1950, and the Daughters of Bilitis, founded in San Francisco in 1955, embodied this new perspective of the gay community as a proud and coherent minority group with its own distinct needs. They stressed gays’ respectability and sought integration and inclusion. Opposing employment discrimination became a key tenet of homophile organizing, and such activists attempted to persuade businesses and public officials to end discrimination against workers whose homosexuality was discovered. However, detecting and rooting out instances of discrimination proved difficult, for those who were found to be gay by one employer typically avoided publicity that might disqualify them from another job.Footnote 24

Workers who took great pains to conceal their homosexuality from employers were not being overly paranoid. At mid-century, employers widely regarded open or suspected homosexuality to be a relevant factor when evaluating current or potential workers. Many employers, including the military and civilian government agencies, perceived all gays to be unsuitable for any employment. A 1950 special U.S. Senate subcommittee declared homosexuality among federal employees to be “immoral and scandalous,” arguing that gay workers would discredit the government.Footnote 25 Government officials similarly justified their postwar purges of suspected gays from federal employment by deeming them “security risks” who were morally corrupt and easily blackmailed.Footnote 26 Similarly, private employers claimed that gays’ willingness to violate sodomy laws indicated their general immorality. Employers often went to great lengths to determine an employee's sexual proclivities, checking military records, observing workers’ behavior, and obtaining statements from other employees. An American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) publication warned, “Any of the various forms that applicants and employees are required to fill out may disclose information that leads to evidence of homosexual conduct.”Footnote 27 One man who was denied a job in 1964 was told, “You are 30 years old, unmarried, and live in San Francisco. Don't you get the point? We don't want your kind.”Footnote 28 Even hinting at gender nonconformity could prove costly, as a male teacher learned when he wore an earring to a job interview. At mid-century, a worker courted unemployment in revealing that he or she did not conform to dominant sexual norms, even in leisure time.Footnote 29

However, even as employers articulated sweeping condemnations of homosexual employees, the changing legal and social climate opened new possibilities. A string of U.S. Supreme Court decisions asserted individuals’ right to privacy, particularly when matters of sexuality and reproduction were at stake.Footnote 30 Advocates followed suit, as the ACLU reversed its earlier stance and broadened its conception of the relationship between civil liberties and sexual freedom in the mid-1960s.Footnote 31 A 1967 ACLU position paper on homosexuality called for “the end of criminal sanctions for homosexual practices conducted in private between consenting adults” because sexual orientation involved a sacred entity that should be protected from state encroachment: “a person's inner most feelings and desires.” The same position paper also urged government officials to ignore employees’ sexual preferences. “There have been, and undoubtedly are today, in the vast stretches of government service, men and women who perform their duties competently, and in their private hours engage in different kinds of sexual activity—without any harmful impact on the agency that employs them…the burden of proof should be placed on the government to show that a homosexual is not suited for a particular job because of the nature of that job.”Footnote 32 The ACLU also joined advocates in Washington, D.C., where gay federal employees used such arguments to win job protections in court. In 1965 and 1969, respectively, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled that workers could not be disqualified or dismissed from federal employment solely because of their homosexuality. Therefore, arguments that framed gay workers’ rights in terms of sexual privacy and the irrelevance of homosexuality to effective job performance began to gain legal traction.Footnote 33

In tandem with these legal developments, the late 1960s saw an expanded movement for gay workplace rights that was embedded within an explicitly radical gay politics. Gay liberation, which mirrored the more militant style of protest adopted by contemporary social movements, demanded cultural expression and freedom from shame. Whereas gay liberationists were deeply suspicious of many of the institutions that ordered heteronormative society, rallying around such phrases as “Smash the church! Smash the state!” they did not universally eschew capitalism or participation in the workforce; rather, many sought inclusion on their own terms.Footnote 34 Therefore, gay liberationists rejected arguments for workplace rights that were rooted in homophile concerns about sexual privacy, which assumed that people could—or should—leave their sexual identity behind at the office door. They asked for the same rights and privileges held by other workers, proclaiming that one's sexual orientation was irrelevant to his or her ability to perform a job. However, they also argued that sexuality was an essential element of one's personhood that should therefore be acknowledged and respected at work. The liberationist impulse energized and sharpened the focus of gay workplace rights campaigns on workers’ freedom to come out at work rather than protecting their sexual privacy. From grassroots organizing to advancing claims upon corporations, legislators, and courts, gay workplace rights advocates used formal and informal channels of protest to advocate for reforms in the law and employment practices that would free gay employees from pressures to conceal their homosexuality or face persecution.Footnote 35

Gay men and lesbians alike experienced the pressures to muffle their sexual identities, and both groups opposed discrimination against homosexuals.Footnote 36 However, their divergent relationships to power in the workplace caused many lesbians to conceive of that problem differently than did gay men. Lesbians understood sexual orientation discrimination to be of a piece with their exploitation as working women. The contemporary assumptions about women's attachment to wage-earning men—used to justify the low pay and dead-end nature of most female-dominated jobs—seemed especially egregious to women who did not couple up with men.Footnote 37 Further, by the early 1970s, the tenets of radical feminism began to color much of lesbians’ activism. Even members of the homophile group Daughters of Bilitis who had strategized with and demonstrated alongside of gay men in the 1960s increasingly wondered whether men could be trusted allies.Footnote 38 Historian Lillian Faderman argues that many lesbians “became aware of the need for lesbian-feminist political goals that were far more radical than those of gay revolutionaries whose aim was equality with heterosexuals.”Footnote 39 Lesbian feminists were increasingly suspicious of hierarchy in all forms—including that between workers and employers—and they doubted that integration alone could ever create meaningful equality between men and women, gays and straights.Footnote 40

Further, whereas not all lesbians offered a critique of capitalism or advocated separatism, lesbians’ law-related efforts in the 1970s focused on a wider variety of targets than those of gay men. Like gay men, lesbians protested discriminatory city codes and state laws that penalized homosexuality.Footnote 41 The Lesbian Rights Project (LRP) was founded in San Francisco in 1977 to fight for lesbians’ legal rights. Although LRP took on a variety of challenges, including defending a woman denied employment as a deputy sheriff in Contra Costa County, California because of her homosexuality, the organization focused primarily on protecting lesbian families: particularly helping mothers maintain custody rights after they came out and left their heterosexual marriages. Therefore, lesbians and gay men held distinct relationships to the law and the workplace. Whereas lesbians critiqued the power and hierarchy in capitalist institutions and sexist assumptions about family composition and women's dependency, gay men offered a more consistent push for workplace integration and advocated more single-mindedly for the freedom to be out at work.Footnote 42

* * *

California, home to some of the nation's earliest and most vibrant gay populations, saw fervent and sustained gay workplace rights organizing at the local, city, and state levels.Footnote 43 In theorizing about California's rich gay heritage, scholars often point to the military bases that drew thousands of unattached men and women to the West Coast during World War II. There they encountered dozens of gay bars, a bohemian atmosphere, and a prosperous economy. Los Angeles also had burgeoning film and cultural industries, whereas in San Francisco, gays found an international port city that contained what scholar Nan Alamilla Boyd has termed “a legacy of sex and lawlessness” and a “live and let live sensibility.”Footnote 44 Other scholarship explains California's unique gay enclaves in terms of the history of tourism, the moral laxity of frontier life, and the sexual practices of nineteenth century soldiers and missionaries.Footnote 45 Although grassroots conservatives decried homosexuality and vice squads targeted and punished gays and lesbians—particularly in Los Angeles—this oppression seems to have helped the gay community to cohere and strategize for its survival.Footnote 46 California was home to the first gay-oriented periodical—first published in 1947—as well as some of the nation's earliest and most sustained homophile activity and organizing for gay rights at work.Footnote 47 California also saw the first courtroom victory for gay rights in the United States when, in 1951, the state Supreme Court ruled that a state agency could not suspend the liquor licenses of bars and restaurants because they catered to open homosexuals.Footnote 48

In Los Angeles, gay employment activism was driven by local political, direct-service, and religious groups. In 1965, the ACLU of Southern California became the first ACLU affiliate to adopt a policy statement affirming the civil rights of gays. The chapter began defending local workers who were fired or denied employment on account of alleged homosexuality.Footnote 49 In 1973, the chapter organized the ACLU's first Rights of Homosexuals Committee, which quickly renamed itself the ACLU of Southern California Gay Rights Chapter (GRC). The GRC dedicated itself to aiding gays in “their struggle for first-class citizenship” by “helping to ensure their civil liberties.” Freedom from job discrimination was one crucial such right, and the GRC especially decried existing federal employment practices. “The nation's largest employer, the federal government, has been unswervingly consistent…[and] has continued to accept the tax revenues of the homosexual minority. It has continued to rip them off in a variety of ways, most notably by refusing employment and by labeling significant portions of the minority as unfit for many types of employment.”Footnote 50 Led by the GRC, gay rights activists in Los Angeles filed test cases with city job rights agencies and initiated a decade-long fight to add nondiscrimination provisions to city employment codes. Local activists achieved that objective in 1979, when the Los Angeles City Council passed a civil rights ordinance prohibiting discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and public accommodation.Footnote 51

Whereas the ACLU fought legal battles on behalf of the local gay community, other organizations sought to meet the practical needs of gay job seekers. The Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Center provided job counseling and training for the underemployed, even matching gay inmates with job opportunities, clothing, and transportation to help expedite their release from prison.Footnote 52 The types of advertised jobs varied widely, suggesting the range of skills and backgrounds of gay applicants. One monthly job bulletin advertised available employment in a variety of fields: “professional, general clerical, restaurant/bar/hotel, clerk/cashier, domestic, building/construction/trades, adult services, accountants and bookkeepers, maintenance, house cleaning, yard work, construction, painting, moving, odd jobs.”Footnote 53 The Center also helped individual employees to maintain their jobs and credentials and worked to convince reluctant employers to hire gay applicants.Footnote 54

Members of the local religious community were also on the front lines of this struggle. The Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) provided crucial job-related support and assistance to Los Angeles gays. The church, founded in Los Angeles by gay pastor Troy Perry in 1968, regarded social activism as a cornerstone of its ministry. In March 1970, Perry led a gay rights march of 250 protestors advocating legal reform and announced his intent to fast until discriminatory federal laws were repealed.Footnote 55 Like the ACLU, the MCC protested laws that penalized homosexuality. The MCC also helped its members to find employment and to exercise their rights on the job. MCC Director of Personnel Services Bob Richards told The Advocate in 1971, “We are more than just a referral agency. When a person comes to us, they are going to get the help they need. We are not going to shuffle them off to some agency. It's time the gay community dealt with the social needs of its own.”Footnote 56 Toward that end, the church hosted weekly meetings of the Greater Los Angeles Coalition to Guarantee Fair Employment Practices and held legal workshops on job rights issues. The MCC also coordinated a full service job placement agency, attempting to convince employers to hire openly gay applicants and training and placing the unemployed.Footnote 57 In Los Angeles, gay workplace rights activists sought pragmatic gains through community organizing and local legal reform.

Hundreds of miles to the northwest, the San Francisco fight for gay rights at work was equally tenacious, yet more confrontational. San Francisco was home to a strong culture of dissent and, like Los Angeles, a vibrant gay community.Footnote 58 There, gay employment rights advocates organized through pre-existing homophile organizations and formed new liberationist groups that articulated demands, pressured local employers and politicians, and built alliances with labor movement leaders. Further, well-established homophile and liberationist activists collaborated and cross-pollinated: homophile groups adopted some of the tactics of more vanguard groups whereas new liberationist organizations directed their attention-grabbing methods toward the longstanding homophile goal of workplace integration.

Fighting for gay employment rights was a key focus of the Society for Individual Rights (SIR), founded in San Francisco in 1964. With a mailing list of 3000, SIR was the nation's largest homophile organization prior to the Stonewall rebellion of 1969.Footnote 59 SIR viewed the state as a powerful potential ally for gays and fought many of its hallmark battles in the legal arena. In the 1960s, SIR held public forums on gay issues for local political candidates, retained attorneys to fight police raids of gay gatherings, and distributed to members a pamphlet entitled “In Case of Arrest: The Pocket Lawyer.” SIR also organized a successful 1970 petition that compelled the San Francisco Human Rights Commission to condemn discrimination against homosexuals.Footnote 60 SIR also provided financial and legal support to workplace discrimination plaintiffs. In a 1973 federal suit filed in the Northern District of California, SIR charged the Department of Agriculture with discriminating against gay workers. SIR's political chairman Jim Foster told reporters that the group filed the suit because “As taxpayers ourselves, gay people very much resent being asked to subsidize the discrimination practiced against them.” Foster accused the federal government of “foreclos[ing] peaceful avenues” and “driving gays into militant action.” He reasoned, “When you have restricted or limited a person's right to livelihood, you have fairly well destroyed the individual.”Footnote 61

Gay liberation had introduced just such militant tactics to the fight for gay rights in San Francisco. The divergence between homophile and liberationist approaches were embodied by the gay activist and journalist Leo Laurence. He began his journalism career as a political moderate whose supervisor at ABC-KGO radio in San Francisco knew he was gay. However, Laurence was “radicalized” when he covered the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Thereupon, he was more forthcoming about his homosexuality with all of his coworkers and confronted the station's sports director after he called Laurence “sissy” and “fairy” on the air.Footnote 62 However, it was Laurence who lost his job in the fallout. SIR immediately hired him to edit Vector, the group's official publication.Footnote 63 In 1969, several months into his tenure there, Laurence published an editorial challenging SIR members to be more forthcoming about their sexuality. He disavowed the tactics of polite advocacy for incremental change. Rather, he argued, gays should not hesitate to come out to their families and their employers. Further, when a worker was fired for being openly gay, other homosexuals had a moral imperative to fight for his or her job reinstatement.Footnote 64 SIR leadership declared the editorial to be too radical and ousted him from the Vector editorship. Laurence told the underground newspaper the Berkeley Barb, “Vector was beginning to show our gay leadership for what it really is: a bunch of middle class, uptight, bitchy old queens.”Footnote 65 Laurence severed his ties with SIR and fought to regain his job at ABC-KGO through labor arbitration, ultimately succeeding in 1970.Footnote 66

Laurence's desire to initiate more radical workplace rights politics proved infectious. In the spring of 1969, his friend Gale Whittington, described by the Berkeley Barb as “an attractive, 21 year old blond accounting clerk,” had just finished modeling for a fashion photo shoot for that newspaper. Laurence attended the photo shoot, and on a whim, embraced Whittington from behind when both men were bare-chested. Another friend captured the hug on camera. The photograph was published in the Barb and accompanied by the taglines “Don't Hide It” and “Homo Revolt.” Although Whittington was not a highly skilled worker, he had received one promotion and two pay raises within his year of employment at States Lines Steamships. However, he began to fear for his job security when he saw one of his bosses with the photo from the Barb.Footnote 67 Whether or not Whittington's coworkers were aware of his homosexuality, the photo publicly outed him, and Whittington was fired immediately. Whittington went to the ACLU for guidance, where he was told that no current laws protected him.Footnote 68

The two men decided to pursue Whittington's reinstatement through a more confrontational and assertive gay politics. They vowed to “remove our masks and engage in direct action” and to “fight in the streets.”Footnote 69 Through their new organization, the Committee for Homosexual Freedom (CHF), Laurence and Whittington began a daily noontime protest at the States Lines headquarters in downtown San Francisco. Approximately thirty protesters attended the first day.Footnote 70 Only a week later, more than 100 protesters attended daily. A CHF publication proclaimed that the attendees “sing freedom songs and songs of joy and love, while they enjoy the sun, hold hands and do what comes naturally. In fact, the pickets on California Street are acting in public just as all homosexuals have been saying for years that we should be able to act in public.’”Footnote 71 Whittington himself seized the opportunity to be more forthcoming about his sexual orientation in the workplace, wearing his “Gay-Is-Good” button to job interviews.Footnote 72 Whittington's dismissal thus galvanized the organizers of CHF to express their sexuality in ways employers could not ignore.Footnote 73

CHF marshaled the direct-action tactics of gay liberation toward the goal of workplace inclusion. A CHF publication listed the “vital and basic human rights” that were at stake for gay workers: “the right to fully and openly express our needs, without fear of intimidation or reprisal; the right not to be judged by some inaccurate stereotype, but as individuals; and the right to enter fully, without concealing our homosexuality, the political, social and economic fabric of America.”Footnote 74 CHF also described the fear that compelled gay workers to downplay aspects of their identities to avoid Gale's fate at States Lines; Gale was “a human being who has lost his livelihood just for being himself.”Footnote 75 CHF publications also framed the objectives of the gay workplace rights movement as distinct from other contemporary rights struggles. “Our militancy is in our openness, our pride in gayness, rather than the violence that some associate with militancy.”Footnote 76 However, displaying this openness might require CHF members to be more confrontational in order to “prove that all homosexuals are not the scared, limp-wristed types typical of the stereotypical homosexuals.” Laurence cautioned CHF members that they should prepare “to face the realities of a sit-in situation. Thinking about handcuffs, bookings, jail, courtrooms etc gives me jitters. But other militant minorities have gone through it… . So can we, if it's necessary!”Footnote 77

CHF initially worked solely on Whittington's behalf. The group presented States Lines with a formal list of demands, which included Whittington's immediate reinstatement with back pay, a fair employment pledge to protect gay employees and applicants, amnesty for employees who joined the picket lines, and a promise to encourage other steamship companies to sign similar pledges. They proclaimed that if their demands were not met, CHF members would picket executives’ homes and stage a sit-in in company offices, remaining in the building until States Lines negotiated.Footnote 78 CHF also encouraged sympathizers to jam States Lines phones by calling the switchboard each day. When States Lines personnel answered, they advised, “Rap with them if you wish, but maybe you'll not feel like saying anything at all. If they hang up, wait a couple minutes, and dial again. ‘Keep them calls coming in.’ It will show them our numbers (even greater than those on the picket line); it will lose them business; [and] they will have to explain the whole situation to customers who call and get a busy signal.”Footnote 79 CHF's confrontational strategy was designed to pressure States Lines into hiring and retaining openly gay workers.

Despite months of CHF protesting, States Lines never reinstated Whittington. The group found more success in another direct action campaign against a local retailer, Tower Records. Frank Denero was a salesclerk who was fired when managers learned that he had winked at a customer. After witnessing the gesture, a private security guard asked Denero whether he was gay. He responded, “I'm not gay or straight. I'm bi if anything.”Footnote 80 When managers dismissed Denero, they told him that they did not “tolerate that free spirit around here.”Footnote 81 CHF organized a daily protest and boycott of the store. A CHF publication declared, “Those of you who believe, with us, that job performance, not sexual orientation, [should] be the criteria for employment please support the boycott of Tower Records. Don't buy at Tower until they agree to our fair and just demands,” which included reinstating Denero with full back pay and pledging not to discriminate against homosexual workers and applicants.Footnote 82 A CHF publication encouraged its members to consider their own precarious employment situations and to rally to Denero's side. “One of our brothers was fired from his position at this store because it was suspected that he may have been a homosexual. This sort of thing has been happening far too long and we will not tolerate such mindless bigotry any longer. Help us show this company and their owners in Sacramento that the people of San Francisco not only disagree with such harassment, but that they will stand with those of us who are fighting for our freedom.”Footnote 83 Whereas a grassroots consumer boycott against States Lines would have been impossible, a retailer such as Tower Records was more sensitive to customer behavior.

CHF justified the Tower boycott by pointing out the hypocrisy of businesses that peddled a liberal spirit but were run by conservatives. “Tower is a store which hires clerks who look hip, caters to hip customers, and sells hip records. Why? Because they're hip to the movement? Hell no! They do it only because it's good business. The managers are purely ‘pigs with mustaches.’ It's a beautiful example of how the uptight monied class capitalizes on serious social trends for their own profit.” CHF decried Tower's attempt to cash in on current trends while embodying outdated homophobic values. “Tower's sign advertises a Joan Baez album. While Joan sings of love, freedom and brotherhood, the management says, ‘we don't tolerate that free spirit around here.’ They don't tolerate it from Frank but they make money from it with Joan. These kinds of capitalist pigs would—and do—sell human flesh for a profit.”Footnote 84 Despite such militant rhetoric, CHF did not advocate the dismantling of capitalism or the destruction of the store, but fought to help Denero regain employment. CHF estimated that the activism turned away approximately 30% of Tower business. After 2 weeks of demonstrations, CHF attained a complete victory for Denero. He was reinstated in his job, an independent arbitrator was appointed to set back pay, and Tower management promised to end sexual orientation discrimination in hiring.Footnote 85

Therefore, even as CHF leaders critiqued capitalism as exploitative, pursuing gays’ right to be out at work was one of their group's bedrock principles. CHF directed its radical rhetoric toward obtaining legal reform and state-protected civil rights. Leaders hoped that voters, and, ultimately, courts, would support their efforts to ban employment discrimination against homosexuals. They drafted and circulated a petition for a ballot measure to ban employment discrimination against homosexuals in San Francisco city and county, a provision that they claimed was “our most ambitious and, we feel, meaningful undertaking.”Footnote 86 The press release announcing the signature-gathering drive for the petition stated, “As homosexuals are becoming aware of their inherent right to constitutionally guaranteed liberties, so are established groups and governmental bodies become aware. The courts have recently upheld the right of homosexuals to employment in civil service, and it was recently reported that restrictions on the employment of homosexuals by civil service are being changed.”Footnote 87 Therefore, even as Laurence proclaimed that “The people of Viet Nam are being oppressed by the same system, the same America spelled with a triple ‘k’ that is oppressing me right here,” he sought a revolution in sexual openness and tolerance rather than a systemic political or economic overhaul.Footnote 88

Although SIR and Laurence had parted ways, SIR was influenced by CHF's tactics and began to combine methods of levying formal claims upon state agencies with more confrontational pressure tactics.Footnote 89 In July 1970, SIR and the Gay Activist Alliance cosponsored a “work-in” in a San Francisco federal building. Early one workday, twenty demonstrators entered the building, wearing badges that labeled them “homosexual[s] working for the government.” They operated building elevators and swept hallways. When they were ousted from the building, they declared themselves “fired” and set up a makeshift “unemployment office” on the building steps.Footnote 90

Further, liberationist, homophile, and civil rights groups fought for local workplace rights protections. Activists collaborated starting in the late 1960s to add a ban on sexual orientation discrimination to city hiring provisions.Footnote 91 In 1970, SIR organized a hearing before the Employment Committee of the San Francisco Human Rights Commission, and SIR's president Larry Littlejohn asked Laurence to testify. Laurence agreed when Littlejohn promised that SIR would support his struggle to be rehired by ABC.Footnote 92 Political candidate Harvey Milk worked simultaneously to convince gay people to be forthcoming about their sexual orientation, and to implement nondiscrimination provisions to help those who did. He reasoned that although the homosexual “can melt into society,…open avowal of homosexuality is necessary for gays in every walk of life” to enable gays to attain full citizenship.Footnote 93 In 1978, as a San Francisco City Supervisor, Milk introduced and helped to pass a gay rights ordinance in the City Council.Footnote 94 Fellow supervisor Gordon Lau framed the ordinance in terms of human rights and fundamental fairness. “All this says is that gay people are OK. It says, ‘If gay people can do the job, hire them; if they can pay the rent, rent to them.’ It affirms a basic right to be treated as a human being.”Footnote 95 After years of concerted and coordinated effort, activists in San Francisco and Los Angeles won gay workplace rights provisions at the city level in the late 1970s.

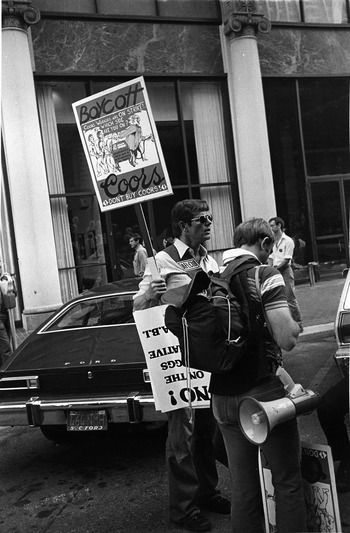

The San Francisco gay community also forged connections with the local labor movement. In the mid-1970s, Allan Baird, a Teamster representative for Beer Drivers Local 888, asked Harvey Milk for help with the Teamsters boycott of Coors beer (see Figure 1). Milk agreed when Baird promised to find jobs for openly gay people within the union.Footnote 96 The movement to combine gay rights and labor rights was at times embodied by the same individuals. Howard Wallace, an organizer with the California American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), founded Bay Area Gay Liberation (BAGL) in the mid-1970s. To Wallace and other members of BAGL, gay rights and workers’ rights were mutually constitutive. “The crude and lurid stereotypes of gay people are just as false as the bumbling ‘Archie Bunker’ image of this country's workers,” wrote Wallace.Footnote 97 He also encouraged gay workers to hone their labor consciousness. Wallace observed, “Being gay and working for a gay boss is obviously not enough” to protect gay workers from exploitation, for wages on Castro Street were as low, and labor conditions as exploitative, as elsewhere in San Francisco.Footnote 98 Toward that objective, Wallace facilitated a meeting among twenty-two Bay area labor leaders and gay rights leaders. The labor officials promised to fight for gay rights clauses in future union contracts, while BAGL promised to oppose eight antilabor ballot initiatives. Jack Crowley, secretary–treasurer of the San Francisco Labor Council, pledged his support, calling the provision “a matter of simple justice.”Footnote 99 Teamster Allan Baird helped facilitate an affirmative action program for gay truckers. Wallace himself was the first driver hired.Footnote 100

Figure 1. Howard Wallace and other gay and labor rights activists collaborated to boycott Coors beer.

Another organization, the Committee on Rights Within the Gay Community, drafted and publicized its “Bill of Rights for Patrons and Employees of Gay Establishments.” The statement proclaimed that workers in gay establishments should have certain labor protections, including “the right to job security and to organize and bargain collectively over wages, job conditions and other issues.” It condemned the sexual abuse of workers by customers and discrimination based on gender presentation. Local gay rights groups described sexual autonomy, expression, and dignity as fundamental workplace rights.Footnote 101

Gay rights activists across California also sought statewide workplace protections. They recruited allies in state government who advocated extending state employment discrimination provisions to include sexual orientation. State Senator Art Agnos first introduced a gay rights bill to the California Senate in 1977. Agnos had been a long-time advocate for disempowered minorities, from homosexuals to the homeless and the mentally ill. His bill addressed sexual orientation along with myriad other aspects of gender presentation and personal style. Assembly Bill 1302 proposed to amend the state labor code to outlaw employment discrimination based on sexual orientation, as well as pregnancy, “a person's refusal to grant sexual favors,” and “the outward appearance of any person with regard to manner of dress, hair style, facial hair, facial features, [and] disproportion of weight to height.” Agnos argued that categorizing or dividing workers based on any of these characteristics should be considered forms of unlawful sex discrimination. These explicit amendments were necessary, he claimed, because “Currently, the California Fair Employment Practice Act makes it unlawful to discriminate in employment on the basis of ‘sex,’ but does not define what such discrimination is.” To Agnos, the category of ‘sex’ reached far beyond one's anatomy and should protect gay workers from persecution.Footnote 102

Gays were heartened by Agnos’ attempt to stretch existing sex discrimination laws to include them. They reasoned that the bill would pass easily “if the opposition considers it to be merely a women's rights issue.”Footnote 103 However, the bill did not advance out of committee that year, and the GRC urged its members to find inspiration to redouble their efforts by reflecting on their own work situations. “How do you know you haven't been discriminated against? What promotions have you missed? How closeted do you have to be at work to protect yourself? Wouldn't you like to know the law says you're safe even if the boss finds out you're gay? When times are tough, old prejudices revive. We're entitled to our right to work and entitled to a law that guarantees it.”Footnote 104 In January 1978, more than 100 gay rights activists lobbied state legislators in Sacramento, but the bill still did not pass. Therefore, although the struggle for gay workplace rights inspired concerted and diverse activism throughout California, campaigns before employers and elected officials left gay workers with only inconsistent protection from discrimination.Footnote 105

* * *

Gay workers across California lobbied legislators to add sexual orientation to existing workplace rights provisions, and activist groups such as the CHF adopted confrontational tactics to attack workplace discrimination; a practice they condemned as a manifestation of society's disdain for homosexuality. However, the workers who fought discrimination in court used well-established tactics to fight for workplace protections within pre-existing legal channels even as the arguments they offered were controversial. In state and federal lawsuits against PT&T, they sought to prove that sexual orientation discrimination was a kind of sex discrimination that was already outlawed by state and federal law.

The California subsidiary of AT&T was one of the largest employers in the state. PT&T operated 80% of California's telephones and employed 93,000 people statewide. A protected monopoly, PT&T was regulated by the California Public Utilities Commission (PUC).Footnote 106 Targeting PT&T at the state level made sense to activists because its parent company gave each of its twenty-two individual operating companies significant flexibility. One operating company president remarked, “We are pretty much left to our own devices…in the end, a lot flows back to earnings; if your earnings are good, AT&T is very permissive; if not, it isn't.”’Footnote 107 The New York AT&T subsidiary claimed not to “differentiate among employees based on their sexual preferences,” and a 1976 publication claimed that AT&T welcomed gay employees nationwide. In reality, however, personnel policies varied by locality.Footnote 108

If the gay employment rights movement in California was at the leading edge of antidiscrimination struggles, PT&T was at the vanguard of explicit homophobia. Advocate groups such as SIR and city employment agencies in Los Angeles and San Francisco had received numerous complaints about PT&T's treatment of homosexual employees and applicants by the early 1970s (see Figure 2). SIR had already sparred with PT&T in 1968, when the company rejected as offensive a proposed telephone book advertisement that read, “Homosexuals, know and protect your rights. If over twenty-one write or visit the Society for Individual Rights.” SIR appealed before the PUC and lost in early 1971. SIR vowed to appeal to the state Supreme Court, and PT&T agreed to print the advertisement several months later.Footnote 109

Figure 2. Pacific Telephone and Telegraph employees took to the streets to demand the right to be openly gay at work.

PT&T made no similar concessions to gay employees. Although AT&T agreed to a $38,000,000 settlement for female and minority employees in 1973, PT&T did not fear similar court involvement on behalf of gay employees.Footnote 110 Instead, officials declared their refusal to employ workers “whose reputation, performance, or behavior would impose a risk to our customers, other employees, or the reputation of the company.” Citing the objections of a fictional homophobic customer, they explained that telephone companies held significant “responsibilities to the community at large” and required “tremendous amounts of public contact.” Therefore, PT&T was “not in a position to ignore commonly accepted standards of conduct, morality or lifestyles.”Footnote 111 Company hiring officials routinely probed applicants’ personal and military records for signs of homosexuality, and interviewers were trained to spot homosexual applicants by asking questions about marital status, living arrangements, and military discharges. PT&T flagged the applications of admitted or suspected gay applicants with “Code 48-Homosexual.” Although company officials assumed that PT&T already employed many homosexuals who successfully hid their sexual orientation, they summarized PT&T's policy thus: “If you're known to be gay, please stay away.”Footnote 112

Gay workplace rights activists found some initial success against PT&T at the local level in San Francisco. In 1972, a new clause in the San Francisco city code prohibited employment discrimination based on sexual orientation, and at first, PT&T refused to comply.Footnote 113 PT&T held contracts with the San Francisco Department of Public Works to install and maintain telephone booths on city sidewalks. In 1973, the city Human Rights Commission claimed that the sidewalk telephones served an “essential public need,” and that PT&T was, therefore, exempt from the nondiscrimination provision.Footnote 114 Gay rights advocates, led by the Pride Foundation, demonstrated that the pay phones produced an annual revenue of $250,000 for PT&T.Footnote 115 After 5 years of continued haggling, gay rights advocates triumphed, forcing PT&T's San Francisco operation to cease sexual orientation discrimination. However, the ruling was unenforceable beyond that city, and PT&T had proved to be an intransigent foe.Footnote 116

In 1973, activists’ campaign against PT&T hit a roadblock, and they began to contemplate a court-centered strategy. The ACLU tried to lodge an official employment discrimination complaint against PT&T before the state Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC), but was rebuffed.Footnote 117 Similarly, members of the PUC told advocates that although they were personally supportive of gay rights, gay workers had no standing under current state nondiscrimination provisions, which did not apply to sexual orientation.Footnote 118 Thereupon, San Francisco gay activists set up test cases against PT&T to force judges to weigh in on the constitutionality of sex discrimination provisions that excluded sexual orientation discrimination claims.Footnote 119 Such a move was inherently risky. Activists acknowledged that “the phone company will undoubtedly resist more than someone else.” However, a positive outcome would yield unprecedented rewards. One activist reasoned, “They are the largest business in the state. If we defeat them and their high priced lawyers, it will have an important psychological impact.” Such an outcome would force smaller firms to yield; therefore, it seemed “better to go after the big one and settle the issue once and for all.”Footnote 120 In 1974, advocates began to organize state and federal lawsuits against PT&T to test the legitimacy of workplace equality laws that excluded sexual orientation.

The plaintiffs in the federal suit, DeSantis v. PT&T, included unsuccessful applicants and former employees of PT&T. The lead plaintiff was Robert DeSantis, a clerical worker and pastor. DeSantis had held a variety of low-level office jobs by the time he sought a position at PT&T in 1974.Footnote 121 His stint as a seminarian at the MCC in Los Angeles seems to have galvanized his sense of social justice. In a church newsletter, DeSantis wrote that religious faith could “build up the egos of each individual gay person by showing each person that they are worth something to themselves, others, and God.”Footnote 122 DeSantis sought employment at PT&T while he worked as a part-time minister, but his application was tossed out when the interviewer told him she knew “what the MCC is.” A second plaintiff had been harassed, then fired from PT&T and refused assistance from the state FEPC; a third plaintiff had faced sexual orientation-based harassment at PT&T and quit under duress, then learned that notes in his personnel file marked him as ineligible for rehire. The DeSantis plaintiffs argued that they were victims of sex discrimination and entitled to relief under Title VII.Footnote 123

Gays’ attempts to analogize sexual orientation discrimination to sex discrimination engaged some of feminists’ most innovative legal arguments.Footnote 124 The plaintiffs offered three arguments to support their right to enact a gay identity at work: that Congress had intended the sex discrimination provision of Title VII to include sexual orientation; that PT&T engaged in sex discrimination by penalizing men, but not women, who preferred male sexual partners; and that sexual orientation discrimination disproportionately affected men because there were more gay men than gay women in society. Both the District Court and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected all three arguments, but the Ninth Circuit consolidated two other cases under DeSantis and offered a lengthier opinion. To answer the question of Congressional intent, the Court referenced a 1977 opinion addressing the rights of transsexuals that declared that Title VII was only intended to refer to “traditional notions of sex.”Footnote 125 The Court also cited two 1976 published Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) opinions stating that Congress used the word “sex” to refer to “a person's gender, an immutable characteristic with which a person is born.” By contrast, the EEOC framed sexuality as “a condition which relates to a person's sexual proclivities or practices, not his or her gender; these two concepts are in no way synonymous.”Footnote 126 To the allegation of sex discrimination based on the sex of one's partner, the Court stated, “whether dealing with men or women the employer is using the same criterion: it will not hire or promote a person who prefers sexual partners of the same sex.”Footnote 127 Finally, the Court rejected the disparate impact argument because unlike women, gay men were not a protected group. The Ninth Circuit thus drew a bright new line between sex and sexual orientation in employment law.Footnote 128

The plaintiffs in the state-level action were only moderately more successful, and as in DeSantis, the court refused to analogize sex and sexual orientation. The plaintiffs in Gay Law Students v. PT&T were a handful of law students from the University of California at Hastings and Boalt Hall who claimed that they were gay and that they had sought or would seek employment at PT&T.Footnote 129 The students were assisted by attorneys from the Neighborhood Legal Assistance Foundation and SIR, and they created a new brief bank that they hoped would help deepen their legal research on gay issues. They filed suit against PT&T for alleged sex discrimination and against the state FEPC for dismissing their claims. The plaintiffs lost in trial court and district court, and they appealed to the state Supreme Court in 1977. In 1979, the Court rejected the students’ argument that sexual orientation discrimination was a form of sex discrimination and refused the plaintiffs’ assertion that the state FEPC should add sexual orientation to existing nondiscrimination codes.Footnote 130

However, in explicitly differentiating sexual orientation from sex, the majority opinion offered a concession to gay rights advocates by framing “coming out of the closet” as a protected activity.Footnote 131 Judge Matthew Tobriner wrote, “A principal barrier to homosexual equality is the common feeling that homosexuality is an affliction which the homosexual worker must conceal from his employer and his fellow workers. Consequently one important aspect of the struggle for equal rights is to induce homosexual individuals to ‘come out of the closet,’ acknowledge their sexual preferences, and to associate with others in working for equal rights.”Footnote 132 Thus, the California Supreme Court outlined protections for sexual orientation in terms of free speech rather than a fixed, essential status. By contrast, gay workplace rights advocates had framed their claims in terms of their inherent identities—in whatever form they were enacted—rather than choices that they made about how to express them. Through the language of the “manifest homosexual,” the court implied that homosexual status was unprotected; what was protected was the act of making it known.Footnote 133 Following that decision, members of the Gay Law Students Association turned the case over to the newly founded National Gay Rights Advocates—a public interest law firm dedicated to assisting gays and lesbians—to challenge PT&T under the free speech provisions of state labor and utility codes. In the parties’ 1987 settlement, PT&T established a $3,000,000 fund for gay employees, but maintained its innocence.Footnote 134

In refusing to define sexual orientation discrimination as a form of sex discrimination prohibited by Title VII, the District Court judges in DeSantis were in line with contemporary federal courts that denied Title VII applicability to gender nonconformity and transsexuality.Footnote 135 Law professor Rhonda R. Rivera, writing in 1985, declared that attempting to use Title VII to pursue remedies for sexual orientation discrimination against private employers was a “dead end route.”Footnote 136 By contrast, advocates hailed the decision in Gay Law Student Association as “groundbreaking,” if narrow; the decision marked the first time any court held sexual orientation discrimination unconstitutional when practiced by an employer apart from the federal or state government. Advocates hoped it would spur similar suits against “any discriminating employer who enjoys substantial market power or who can be characterized as a ‘public service enterprise,’” including newspapers, labor unions, and universities.Footnote 137 However, other state courts did not follow suit, and lower California state courts and agencies reached conflicting interpretations of the decision. In the early 1980s, although the Civil Service Commission of Contra Costa County found in favor of a lesbian whose application for a deputy sheriff position was rejected solely because of her homosexuality, relief was denied to a Disneyland employee who was fired in part because he insisted on wearing a button identifying himself as gay when he interacted with customers.Footnote 138

For gay rights activists in the late 1970s, asking courts to compare sexual orientation discrimination with sex and race discrimination was a sensible move. Title VII protections had yielded stunning victories for working women and minorities.Footnote 139 However, judges did not accept gays’ analogy between sex and sexual orientation, and gay advocates had thus unwittingly compelled jurists to articulate differences between those categories before the law. Judges’ reasoning left gays vulnerable to the conservative arguments, already gaining steam, that homosexuality was an immoral expression that could and should be contained or even eradicated. DeSantis and Gay Law Students Association thus set the course for future gay rights jurisprudence and activism.

* * *

The outcome of the gay workplace rights campaigns of the 1970s was a piecemeal set of provisions that substituted voluntary corporate action, interest group pressure, and scattered local laws and court decisions in place of strong, uniform protections from discrimination. In California and nationwide, activists’ battles for state-enforced gay workplace rights produced heated struggles at the local level, unlike the situation with women and racial minorities, whose discrimination claims could be fielded by the EEOC and adjudicated by federal courts.Footnote 140 Starting in the 1970s, city governments began to amend employment discrimination provisions to include gays and lesbians.Footnote 141 In California, a decade of grassroots organizing yielded significant local victories. Within a 3 year span in the early 1980s, the San Francisco Police Department held a recruiting drive to attract gay police officers, the University of California system extended nondiscrimination provisions to protect homosexual employees, and California's governor issued an executive order to prohibit discrimination against gays and lesbians employed by state agencies.Footnote 142

However, gay rights provisions often generated fierce debate, even among proximate communities. Voters in San Jose, California, rejected a proposed nondiscrimination city ordinance. Dean Wycoff, executive director of Moral Majority, proclaimed that San Jose voters did not share their neighbors’ permissive attitudes: ‘“We don't want the cancer of homosexuality spreading from San Francisco down to Santa Clara County.’”Footnote 143 Further, AB 1, the proposed addition of nondiscrimination provisions for gay workers to public and private employment codes, remained bitterly divisive in the California legislature into the 1990s.Footnote 144 In the absence of state or federal protection, activists replicating these campaigns in different states and localities felt they were reinventing the wheel by fighting the same battles over and over to mixed results.Footnote 145

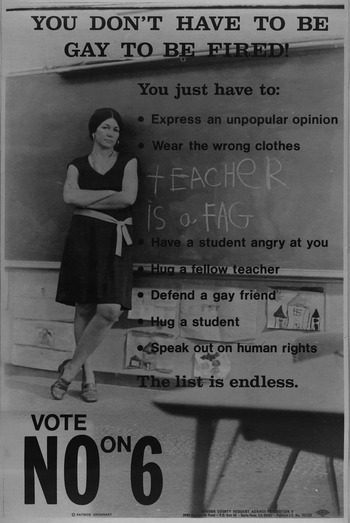

Further, the growing visibility of gay rights struggles mobilized the New Right, indicating that the politics of homophobia could yield political gold. Gay members of certain professions faced systematic campaigns to oust them from their positions. In 1978, conservative state legislator John Briggs introduced Proposition 6 (also called the Briggs Initiative), a ballot measure designed to restrict teachers from “advocating, imposing, encouraging or promoting homosexual activity.”Footnote 146 In the statewide “No on 6” campaign, gay men and lesbians revealed themselves to friends, family, and coworkers to let them know that gay people included those they knew and cared about. Gay and lesbian activists framed Proposition 6 as an attempt to interfere with free speech, disrupt gay teachers’ ability to make a living, and undermine job security and collective bargaining (see Figure 3).Footnote 147 “Proposition 6 would be the first law to require job discrimination against all members of a minority group,” claimed “No on 6” literature.Footnote 148 In a debate with John Briggs, lesbian and public health advocate Josette Mondanaro disputed the contention that gay and gay-friendly teachers would corrupt children. She claimed, “Lord knows we have been raised in a heterosexual society, watching heterosexual television, reading heterosexual magazines and books, and it never rubbed off on us. You don't have to like us, but you don't have to beat on us either.”Footnote 149 After a highly organized campaign, Proposition 6 was soundly defeated in November 1978, even in conservative sections of the state.Footnote 150

Figure 3. In 1978, California gay rights activists came together to defeat Proposition 6, which would have banned workers in California public schools from signaling a gay identity or “promoting” homosexuality.

Amidst fierce local battles for workplace rights, gay and lesbian workers and their advocates found some success courting corporate favor. Workers lobbied their employers for such benefits as bereavement leave and spousal medical benefits.Footnote 151 By 1978, major corporations including Bank of America, IBM, NBC, and Honeywell publicly claimed to be equal opportunity employers (though no government office tracked or verified these claims).Footnote 152 Such corporations as Quaker Oats and American Express claimed to follow local laws pertaining to gay workplace rights; however, in 1990, only 16% of American Express operations were in areas with gay workplace rights provisions.Footnote 153 Organizations such as the National Gay Task Force and Human Rights Campaign have successfully pressured employers to voluntarily change their policies.Footnote 154 Publications such as The Advocate have surveyed employers about employment practices, and interest groups monitor and publish businesses’ treatment of gay and lesbian employees.Footnote 155 Further, throughout the 1990s, gay, lesbian, and bisexual employee groups won domestic partner benefits from their corporate employers. By 2004, 42% of Fortune 500 companies provided equal partner benefits.Footnote 156

Another method of advocating for gay workplace rights has been to mobilize as consumers. Many corporations have discovered that courting gay customers can be good for business. In 1994, American Airlines launched a campaign to re-brand itself as gay-friendly. “Gay men and lesbian women are some of our most loyal and frequent customers,” lectured a staff sensitivity-training video. American Airlines promoted special gay-friendly flights from San Francisco to New York in anticipation of Gay Games IV and the twenty-fifth anniversary of Stonewall.Footnote 157 A rival business, United Airlines, felt the anger of the gay community when it filed suit in court to oppose a San Francisco equal benefits ordinance in 1997. Gay activists launched a nationwide boycott, distributing buttons, stickers, and flyers bearing the slogan “United Against United,” and gathered to burn their United frequent flyer cards outside the company's San Francisco offices. In 1999, the San Francisco Gay Men's Chorus publicly returned to United a $15,000 sponsorship check. After 2 years in court, United dropped its suit and extended benefits to domestic partners of its employees and retirees.Footnote 158 Some prominent corporations sensing a business advantage or facing targeted activist pressure have taken steps to accommodate gay workers and customers.Footnote 159

Because gay workers have not obtained protection under Title VII and other antidiscrimination provisions, employment rights activists have relied on isolated and local struggles and the tactics of persuasion and protest rather than the protections of state-backed rights. However, the emergence of AIDS in the 1980s also shifted and refocused gay activists’ own workplace efforts. In the 1980s, activist organizations that had been at the forefront of the workplace discrimination struggle pursued acceptance of HIV-positive coworkers and the inclusion of HIV/AIDS within state and federal disability provisions.Footnote 160 Discriminatory employers cited contagion metaphors and healthy coworkers’ fears in firing both the HIV-positive and gay employees, who were assumed to be infected.Footnote 161 In a 1990 ACLU survey of 260 employment discrimination reporting agencies, 30% of complainants reported discrimination because they were perceived to be HIV-positive.Footnote 162 Cities including Los Angeles began to focus on education to keep the disease from spreading, promote tolerance, and reduce panic, rather than upon protecting all gay employees from discrimination.Footnote 163 AIDS spurred the collaboration and the formation of stronger, coordinated national institutions, which replaced previously local, targeted activism. Additionally, the ACLU and other civil rights advocates took on AIDS discrimination cases, rather than continuing campaigns to expand employment provisions for all gay workers. Responding to the challenges of the 1980s—the AIDS crisis, anti-gay conservative mobilization, and legislative defeats—consolidated and refocused the gay rights movement.Footnote 164

* * *

The gay workplace rights movement of the 1970s struggled against the pressures of gender conformity and sex typing that still structure the American workplace. These activists framed their rights claims not in the terms of freedom from persecution for a set of private behaviors, but in terms of freedom to express an immutable identity.Footnote 165 They argued that gender and sexual orientation were not essential to the performance of any job, and they demanded the right not to conceal their homosexual status. But they did not want that status to define them. This strategy could have been a powerful aid to another group simultaneously fighting to boost its workplace status in the 1970s: women. Unlike gay rights activists, the workplace-focused feminists of the 1970s did not have the choice to conceal what made them different, but they could downplay and de-emphasize their sex. Liberal feminists fought to both open male-dominated jobs to women and to enable women to perform a less restrictive gender identity at work. However, feminist activism tended to prioritize gaining women's access to all-male enclaves of the workforce. Such campaigns often denied or downplayed difference in order to strengthen claims for equality. By contrast, gays stressed only respect for attributes that allegedly made them different, and thus, they levied a more focused attack upon the assumptions of inferiority and pressures for conformity that have historically faced workers who were not male, white, able-bodied or heterosexual.Footnote 166

The framing of homosexuality as enacted rather than essential crippled gay workers’ campaigns to expand workplace diversity and to liberalize workplace culture. The legally protected freedom of workplace gender expression envisioned by activists in the 1970s has not come to pass. Since then, working women have found that they must downplay their femininity to compete with men for elite jobs, yet avoid seeming unfeminine.Footnote 167 Judges still struggle to untangle the intersections of sex, gender, and sexual orientation in the workplace, as the United States Supreme Court has interpreted Title VII to protect masculine women, but the rights of effeminate men remain unclear.Footnote 168 Many gay employees experience explicit or implicit pressure to closet or downplay their sexual identities. A 2008 survey revealed that whereas 90% of sexual minorities were out to friends and family, only 25% were out to all of their coworkers.Footnote 169 Economists identify workers’ persistent biases against gay coworkers and the consistent financial penalties facing gay and lesbian workers, regardless of their race, education, age or occupation.Footnote 170 Gay rights advocates must frame and position test cases carefully, weighing judges’ personal opinions on homosexuality, even in campaigns to equalize their civil rights with others’.Footnote 171 Despite its mixed outcomes, the grassroots movement for gay workplace rights in the 1970s represented a profound challenge to the regime of gender conformity and masculine privilege that still structures the typical American workplace.