Introduction

Depression and anxiety are highly prevalent (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas and Walters, Reference Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas and Walters2005; McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington and Jenkins, Reference McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington and Jenkins2009), have substantial impacts on quality of life and functioning for the individual (Haslam, Atkinson, Brown and Haslam, Reference Haslam, Atkinson, Brown and Haslam2005; Paul and Moser, Reference Paul and Moser2009) and are associated with substantial economic costs (Das-Munshi et al., Reference Das-Munshi, Goldberg, Bebbington, Bhugra, Brugha and Dewey2008; Health and Safety Executive, 2012). Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for a range of depressive (Butler, Chapman, Forman and Beck, Reference Butler, Chapman, Forman and Beck2006; Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer and Fang, Reference Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer and Fang2012) and anxiety conditions (Olatunji, Cisler and Deacon, Reference Olatunji, Cisler and Deacon2010; Otte, Reference Otte2011), but the vast majority of evidence for the effectiveness of this approach is based on highly differentiated treatment protocols for specific diagnoses (NICE, 2011). An alternative approach, termed transdiagnostic CBT (tCBT), aims to identify a small number of cognitive and behavioural processes that are common across a range of depressive and anxiety conditions. These core processes are then used to develop a single treatment that can be applied across a range of presentations.

Proponents of tCBT have put forward a number of potential advantages to this approach. These include the possibility of offering more effective, efficient treatment of co-morbid presentations (Borkovec, Abel and Newman, Reference Borkovec, Abel and Newman1995), something that is common in depression and anxiety presentations (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas and Walters2005). Furthermore, tCBT may reduce the training needs of therapists (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Buckner, Pusser, Woolaway-Bickel, Preston and Norr2012). Since tCBT by definition should be effective for a variety of different presentations, formation of ideally sized groups for group-delivered CBT should be simplified (Norton and Philipp, Reference Norton and Philipp2008).

There are potential disadvantages to tCBT, not as widely discussed in the literature. Clinical effectiveness may be diluted compared to diagnosis-specific treatments, because treatments are designed to treat a wide variety of disorders (Craske et al., Reference Craske, Farchione, Allen, Barrios, Stoyanova and Rose2007). It is unclear whether tCBT treatment is as acceptable to clients as disorder-specific CBT. When delivered in groups with a mixture of presentations, it may be difficult for clients to empathize with and learn as much from each other compared to groups in which clients have similar presentations (McEvoy, Nathan and Norton, Reference McEvoy, Nathan and Norton2009).

Three previous reviews have examined the effectiveness of tCBT. The first, Norton and Philipp (Reference Norton and Philipp2008), was limited to anxiety studies. Of the nine studies reviewed, two were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Erickson, Janeck and Tallman, Reference Erickson, Janeck and Tallman2007; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Buckner, Pusser, Woolaway-Bickel, Preston and Norr2012) and one used a quasi-randomized design (Norton and Hope, Reference Norton and Hope2005); the remainder used uncontrolled designs. The review calculated a large overall within-group effect size of transdiagnostic anxiety treatments (d = 1.29, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.93), compared to a small within-group effect size for control conditions (d = 0.14, 95% CI −0.21 to 0.49). The authors concluded that tCBT had considerable clinical utility, the preliminary data supporting the efficacy of the interventions.

The second review, McEvoy et al. (Reference McEvoy, Nathan and Norton2009), included 10 studies, with one RCT (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Janeck and Tallman2007). The same quasi-randomized study was included, cited as two separate studies (Norton, Hayes and Hope, Reference Norton, Hayes and Hope2004; Norton and Hope, Reference Norton and Hope2005). The remainder were uncontrolled studies. No meta-analysis of results was performed but a narrative synthesis concluded that tCBT protocols were highly promising, although additional research was required.

The third review, Reinholt and Krogh (Reference Reinholt and Krogh2014), included five RCTs (Erickson, Janeck and Tallman, Reference Erickson, Janeck and Tallman2007; Farchione et al., Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands and Carl2012; Norton and Barrera, Reference Norton and Barrera2012; Roy-Byrne et al., Reference Roy-Byrne, Craske, Sullivan, Rose, Edlund and Lang2010; and Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Buckner, Pusser, Woolaway-Bickel, Preston and Norr2012), the quasi-randomized Norton and Hope (Reference Norton and Hope2005) and six uncontrolled studies. They reported a moderate combined effect size for all studies (SMD = -0.681, 95% CI -0.903 to -0.458) favouring tCBT. The authors were more cautious in their conclusions than the previous reviewers.

Although the reviews were broadly positive about the effectiveness of tCBT approaches, caution is needed before accepting these conclusions. The reviews identified only a small number of RCTs; the majority of studies were based on uncontrolled designs. The RCTs all compared tCBT to non-active control conditions, with the exception of Norton and Barrera (Reference Norton and Barrera2012). There were a number of methodological limitations of the reviews when evaluated against standard guidelines for the conduct of systematic reviews (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and The PRISMA Group, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). There was limited description of search strategies, and two reviews were limited to peer-reviewed publications, which may lead to an overestimate of effects because of publication bias (Dwan et al., Reference Dwan, Altman, Arnaiz, Bloom, Chan and Cronin2008; Song, Eastwood, Gilbody, Duley and Sutton, Reference Song, Eastwood, Gilbody, Duley and Sutton2000). There was limited evaluation of the methodological quality of included studies. Two reviews were conducted by researchers involved in tCBT protocol development. There is evidence that researcher allegiance can lead to inflated effect estimates in RCTs of psychological treatments (Luborsky et al., Reference Luborsky, Diguer, Seligman, Rosenthal, Krause and Johnson1999). The case for tCBT would be strengthened by an additional independent review of the current evidence base.

Method

We adhered to the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2009) guidelines in the conduct of the review and PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009) in the reporting of the review.

Search strategy

The following databases were searched to cover peer-review and grey literature sources: PsycINFO, Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, ASSIA, Web of Knowledge, OAIster, Open Grey, Trip Database and ZETOC. Additional searches were conducted in NHS EED, HTA Database, CEA Registry and RePEc health economic databases to identify relevant cost-effectiveness data. Databases were searched from inception to June 2013, with no publication status or language restrictions imposed.

Reference lists of included studies were examined, reverse-citation searches of included studies were conducted and websites of researchers and study groups in the field of tCBT were accessed to identify additional studies.

Search terms

Search terms, including free text and thesauri terms, were developed for PsycINFO and adapted for other databases (Appendix A). Terms covered two broad constructs, CBT and transdiagnostic treatment, combined using the Boolean AND. Search terms for CBT were adapted, with permission, from a systematic review of low-intensity psychological interventions (Rodgers et al., Reference Rodgers, Asaria, Walker, McMillan, Lucock and Harden2012). Search terms designed to capture the “transdiagnostic” construct were derived from searches of books, studies and articles uncovered during scoping searches. Thesauri available within the Ovid SP database were used to further inform search terms related to CBT.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

A priori inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed around standard criteria.

Participants

Adults (aged 16 years or over). Participants at baseline met diagnostic criteria for an anxiety or depressive disorder established by gold standard structured clinical interviews or scored above a clinical cut-off point on a standardized severity measure. To ensure treatment was transdiagnostic, participants within studies must not have had uniform diagnoses.

Intervention

The intervention had to be described as tCBT (or use related terms such as Unified Protocol, mixed-diagnosis CBT, broad-spectrum CBT)

Comparator

Any comparison condition, including control or other active treatments.

Outcomes

Depression, anxiety or generic psychological wellbeing measured as a severity score or a dichotomous outcome (e.g. depressed, not depressed) and health economic data.

Study design

Randomized controlled trials. Quasi-randomized and uncontrolled trials were excluded.

Selection of studies

Two reviewers (PA, PT) used a pre-piloted eligibility form to assess studies. Disagreements were resolved through consensus and, where necessary, discussion with a third reviewer (DMcM). Titles and abstracts were first examined, and full papers obtained for studies passing this initial sift. Full papers were then re-examined using the eligibility form to determine final inclusion.

Data extraction

Data were extracted to a pre-piloted data extraction form by the primary reviewer (PA) and checked by the secondary reviewer (PT). Extracted data included study name, year and type of publication, authors, study location and setting, design, study sample characteristics, inclusion and exclusion criteria, description of interventions and controls, follow-up length, outcomes reported and data necessary to calculate effect sizes (e.g. means, standard deviations, sample size).

Quality assessment

Methodological quality and sources of bias were assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Altman, Gøtzsche, Jüni, Moher and Oxman2011) and an additional quality tool specifically tailored to assess the quality of psychological RCTs (Yates, Morley, Eccleston and Williams, Reference Yates, Morley, Eccleston and Williams2005).

Data synthesis

Standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95 percent confidence intervals using Hedges's adjusted g (Hedges, Reference Hedges1981) were calculated for anxiety, depression and general psychological wellbeing severity measures.

Pre-planned comparisons

Results were grouped first by intervention type (individual or group), second by comparator (control condition or active treatment) and finally by outcome measure (anxiety, depression, general psychological wellbeing). If two or more studies were similar in terms of the intervention, comparator and outcome type, a meta-analysis was conducted. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, with values over 50% taken to indicate substantial heterogeneity. Analyses were conducted in Review Manager 5 (Cochrane Collaboration, 2012).

Results

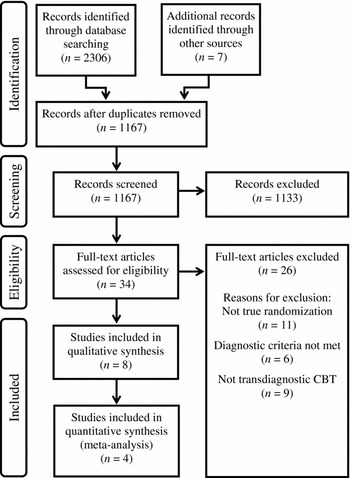

Electronic database searches identified 2306 citations. Seven additional unique records were identified through other sources. After removing duplicates, 1167 unique citations remained. Screening titles and abstracts excluded 1133 citations, leaving 34 full-text articles to be assessed. Of these, eight were judged eligible for inclusion in the review. Four studies were meta-analysed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Search results and study selection flowchart

Of 34 full-text articles assessed, 26 were excluded for the following reasons: 11 studies did not use randomization or used quasi-random methods of assigning participants to treatment; nine studies were excluded for not using recognizable tCBT treatment protocols; participants in six studies did not meet diagnostic inclusion criteria (Appendix B).

Description of included studies

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive characteristics of the eight studies that met inclusion criteria for the review (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Janeck and Tallman2007; Farchione et al., Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands and Carl2012; Johnston, Titov, Andrews, Spence and Dear, Reference Johnston, Titov, Andrews, Spence and Dear2011; Norton, Reference Norton2012; Norton and Barrera, Reference Norton and Barrera2012; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Buckner, Pusser, Woolaway-Bickel, Preston and Norr2012; Titov, Andrews, Johnston, Robinson and Spence, Reference Titov, Andrews, Johnston, Robinson and Spence2010; Titov et al., Reference Titov, Dear, Schwencke, Andrews, Johnston and Craske2011).

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies

Notes: * Calculated using pooled variance; ADIS-IV = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for the DSM-IV; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory (1996 revision); CBT = cognitive behavior therapy; CGI-S = Clinical Global Impressions - Severity scale; DASS-21 = Depression Anxiety Stress Scales - short-form version; F-SET = False Safety Behavior Elimination Therapy; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; iCBT = internet CBT; MINI = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Version 5.0.0; N = number of participants; N/A = not available; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire - 9; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders; SD = standard deviation; HARS = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HRSD = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; SPRAS = Sheehan Patient-Rated Anxiety Scale; STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

Table 2 summarizes the principal diagnosis of the total sample. Social phobia (32.3%), panic disorder (25.2%) and generalized anxiety disorder (29%) comprised the overwhelming majority of diagnoses. Depression was the principal diagnosis in only 5.2% of the entire sample.

Table 2. Principal diagnosis of included participants

Quality assessment of included studies

Table 3 summarizes the quality assessment of included studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. All studies were deemed at high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel, because this is typically inevitable in a trial of a psychological intervention. All studies were judged at high risk of bias in “other sources of bias” because of potential for research allegiance effects (treatment developers were the researchers evaluating their effectiveness). Unclear random sequence generation prompted an unknown risk of bias for this criterion in four studies (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Janeck and Tallman2007; Farchione et al., Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands and Carl2012; Norton, Reference Norton2012; Norton and Barrera, Reference Norton and Barrera2012). Erickson et al. (Reference Erickson, Janeck and Tallman2007) had an unknown risk of bias because of unclear information concerning blinding of assessors. This study was also assessed to be at high risk of bias due to selective reporting; two further were rated as having an unknown risk of bias on this quality item (Norton, Reference Norton2012; Norton and Barrera, Reference Norton and Barrera2012).

Table 3. Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool summary

Notes: + low risk of bias; − high risk of bias; ? unknown risk of bias

Assessment of treatment quality within included studies

The Yates assessment tool (Yates et al., Reference Yates, Morley, Eccleston and Williams2005) was used to assess quality of treatment administered in source studies. Items assessing description of treatment content and setting, description of treatment duration and manualization of treatment protocols were rated as present in all source studies. One study did not assess clinician adherence to the manual (Farchione et al., Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands and Carl2012). One study provided no information concerning therapist training (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Janeck and Tallman2007). Evidence of a lack of client engagement was identified in two studies (Norton, Reference Norton2012; Norton and Barrera, Reference Norton and Barrera2012) (Table 4).

Table 4. Yates et al. (Reference Yates, Morley, Eccleston and Williams2005) treatment quality assessment tool

Notes: Maximum total score is 9; higher scores denote lower bias

Clinical effectiveness

Clinical effectiveness results are grouped by type of comparator and mode of treatment delivery. Results are reported separately for each of the three main classes of primary outcome.

Individual tCBT versus control conditions

Anxiety severity measures

Four studies provided posttreatment data from anxiety scales for individual tCBT versus waitlist control conditions (Farchione et al., Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands and Carl2012; Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Titov, Andrews, Spence and Dear2011; Titov et al., Reference Titov, Andrews, Johnston, Robinson and Spence2010, Reference Titov, Dear, Schwencke, Andrews, Johnston and Craske2011) (see Figure 2). Farchione et al. (Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands and Carl2012) used the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (M. Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1959) while the remaining studies utilized GAD-7 (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe, Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006). The data were re-analysed excluding Titov et al. (Reference Titov, Dear, Schwencke, Andrews, Johnston and Craske2011), a potential outlier (see Figure 3). To assess any difference between internet versus face to face treatment we excluded the single face to face study, Farchione et al. (Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands and Carl2012) (see Figure 4).

Figure 2. Individual transdiagnostic CBT vs. control conditions, anxiety measures

Figure 3. Individual transdiagnostic CBT vs. control conditions, anxiety measures, excluding Titov et al. (Reference Titov, Dear, Schwencke, Andrews, Johnston and Craske2011)

Figure 4. Individual transdiagnostic CBT vs. control conditions, anxiety measures, excluding Farchione et al. (Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands and Carl2012)

Depression severity measures

The same four studies provided posttreatment data from depression scales (Figure 5). Farchione et al. (Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands and Carl2012) utilized the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1960) while the remaining studies used the PHQ-9 (Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams, Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001). For comparison, Farchione et al. (Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands and Carl2012) was again excluded (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Individual transdiagnostic CBT vs. control conditions, depression measures

Figure 6. Individual transdiagnostic CBT vs. control conditions, depression measures, excluding Farchione et al. (Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands and Carl2012)

Generic severity measures

Three studies provided posttreatment data from generic scales for mental health (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Titov, Andrews, Spence and Dear2011; Titov et al., Reference Titov, Andrews, Johnston, Robinson and Spence2010, Reference Titov, Dear, Schwencke, Andrews, Johnston and Craske2011) (see Figure 7). Each used the DASS-21 (Lovibond and Lovibond, Reference Lovibond and Lovibond1995).

Figure 7. Individual transdiagnostic CBT vs. control conditions, generic measures

Group tCBT versus control conditions

Anxiety severity measures

Two studies provided posttreatment anxiety data for group tCBT versus a control condition (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Janeck and Tallman2007; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Buckner, Pusser, Woolaway-Bickel, Preston and Norr2012). Erickson et al. (Reference Erickson, Janeck and Tallman2007) used the BAI (Beck and Steer, Reference Beck and Steer1990) while Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Buckner, Pusser, Woolaway-Bickel, Preston and Norr2012) used the SPRAS (Sheehan, Reference Sheehan1983). Results are not meta-analysed because of substantial heterogeneity (I2=80%, p = 0.03). Individual effect sizes are summarized in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Group transdiagnostic CBT vs. control conditions, anxiety measures

Depression severity measures

Only Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Buckner, Pusser, Woolaway-Bickel, Preston and Norr2012) provided posttreatment depression-specific severity data, using the BDI-II (Beck, Steer and Brown, Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996). The SMD was −0.38, favouring tCBT (95% CI −0.80 to 0.04).

Generic severity measures

Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Buckner, Pusser, Woolaway-Bickel, Preston and Norr2012) alone provided posttreatment generic mental health severity data. They used the CGI (Guy, Reference Guy1976). The SMD was −0.99, favouring tCBT (95% CI −1.43 to −0.55).

Individual tCBT versus other active treatments

No studies compared individual tCBT to another active treatment.

Group tCBT versus other active treatments

Anxiety severity measures

Two studies provided posttreatment data from anxiety scales for group tCBT versus active treatment (Norton, Reference Norton2012; Norton and Barrera, Reference Norton and Barrera2012). Norton (Reference Norton2012) used the BAI while Norton and Barrera (Reference Norton and Barrera2012) used the STAI (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg and Jacobs, Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg and Jacobs1983). The studies were not meta-analysed because treatments, relaxation and disorder-specific CBT, were not considered similar enough that combining them would be meaningful. For Norton (Reference Norton2012) the SMD was −0.24 (95% CI −0.73 to 0.24), a non-significant difference favouring group tCBT over relaxation. The SMD for Norton and Barrera (Reference Norton and Barrera2012) was 0.06 (95% CI −0.51 to 0.64), a non-significant difference favouring diagnosis-specific group CBT over group tCBT.

Depression severity measures

Norton and Barrera (Reference Norton and Barrera2012) provided posttreatment depression-specific severity data using the BDI-II. The SMD was −0.25 (95% CI −0.83 to 0.33).

Generic severity measures

Both Norton (Reference Norton2012) and Norton and Barrera (Reference Norton and Barrera2012) provided posttreatment generic mental health severity using the severity scale of the CGI (CGI-S). The SMD for Norton (Reference Norton2012) was −0.24 (95% CI −1.56 to 1.08). The SMD for Norton and Barrera (Reference Norton and Barrera2012) was −0.22 (95% CI −1.35 to 0.92).

Cost-effectiveness

There were no studies identified that examined the cost-effectiveness of tCBT.

Discussion

The aim of the review was to assess the effectiveness of tCBT as evaluated in RCTs for depression and anxiety in adults. We identified eight studies, the majority of which were small (total N = 732). One RCT included in the Reinholt and Krogh (Reference Reinholt and Krogh2014) review was excluded because the intervention was a tailored CBT treatment rather than a single transdiagnostic protocol (Roy-Byrne et al., Reference Roy-Byrne, Craske, Sullivan, Rose, Edlund and Lang2010). Four studies were of individual tCBT versus control conditions. These found evidence of significant effects in the moderate to large range for the outcomes of anxiety, depression and measures of generic mental health symptomatology. Two studies compared group tCBT with control conditions. Of the two studies, Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Buckner, Pusser, Woolaway-Bickel, Preston and Norr2012) found some evidence of the effectiveness of tCBT, with significant effects ranging from small to large, though the effect reported for anxiety in Erickson et al. (Reference Erickson, Janeck and Tallman2007) was non-significant. Only two studies compared tCBT to other active treatments, both of which used a group format of delivery. A meta-analysis was not conducted because of differences in the active treatment conditions. There was no indication of significant differences between tCBT and the other active treatment conditions. We found no data on the cost-effectiveness of tCBT treatment.

Limitations

These results must be considered in the light of both the limitations of the current review method and the primary studies themselves. Although we developed a systematic review protocol at an early stage of the review, we did not publish this on a database such as PROSPERO. Alternative definitions of transdiagnostic CBT, such as that offered by McEvoy et al. (Reference McEvoy, Nathan and Norton2009), may be preferable to the operational definition we used because of the greater level of specificity offered.

Our review identified only eight RCTs involving tCBT. Although we made efforts to search grey literature, it cannot be ruled out that unpublished trials were missed, especially if descriptive terms used for treatments differed greatly from that found in scoping searches for this review. We found too few studies to formally assess the possibility of publication bias.

Allocation concealment is considered a key methodological standard of RCTs because there is evidence that absence of allocation concealment is associated with increased effect sizes (Schulz and Grimes, Reference Schulz and Grimes2002; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Egger, Gluud, Schulz, Jüni and Altman2008). Four studies had unclear risk of bias for this item on the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Janeck and Tallman2007; Farchione et al., Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands and Carl2012; Norton, Reference Norton2012; Norton and Barrera, Reference Norton and Barrera2012). It is possible that estimates of effectiveness are overestimated in these studies. All studies were conducted by researchers who developed the transdiagnostic treatment protocols, a risk for researcher allegiance effects (Munder, Brütsch, Leonhart, Gerger and Barth, Reference Munder, Brütsch, Leonhart, Gerger and Barth2013). This may also be associated with inflated effect sizes. Three studies were rated as either unclear or high risk of bias for selective reporting of outcome data (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Janeck and Tallman2007; Norton, Reference Norton2012; Norton and Barrera, Reference Norton and Barrera2012). This form of bias typically inflates treatment effects, because results that are not positive may be less likely to be reported. Of concern was the absence of clear statements regarding primary outcome measures. This is a particular concern for the evaluation of transdiagnostic treatment, because it may not be clear what the most relevant outcome measure should be.

In summary, there are a number of methodological limitations of the primary studies, each of which may artificially increase observed effect sizes. This places an important caveat around the generally positive findings. Additional caveats include the small number of trials identified. Studies comparing tCBT to an active comparator were particularly scarce. The review found no transdiagnostic treatment cost-effectiveness evidence.

Research implications

The limitations of the primary studies suggest a number of implications for future research. First, future RCTs should adhere to accepted methodological standards for RCTs to minimize the possibility of bias. Adherence to the CONSORT statement in trial reporting would substantially improve this situation (Schulz, Altman and Moher, Reference Schulz, Altman and Moher2010). Researchers should publish trial protocols in which all proposed outcomes are stated and primary outcomes identified a priori. There is as yet an absence of independent evaluation of transdiagnostic treatments; trials to date have been conducted by researchers who developed the transdiagnostic protocols and are therefore at risk of researcher allegiance effects. Future research teams should consist of, in the words of Leykin and DeRubeis (Reference Leykin and DeRubeis2009), researchers “who possess complementary areas of expertise, and correspondingly opposite allegiances.”

While a number of studies provided follow-up data beyond the end of treatment it was not possible to calculate between-group effect sizes because, at the end of the treatment phase, control condition participants were immediately offered treatment. There is substantial evidence that disorder-specific CBT has an effect that continues beyond the end of treatment (Hollon, Stewart and Strunk, Reference Hollon, Stewart and Strunk2006; Steinert, Hofmann, Kruse and Leichsenring, Reference Steinert, Hofmann, Kruse and Leichsenring2014). Future trials should seek to use designs in which the ability of tCBT to reduce relapse relative to other conditions is examined. Future studies comparing tCBT to disorder-specific treatments should follow accepted standards for the design and analysis of non-inferiority RCTs (Fleming, Odem-Davis, Rothmann and Shen, Reference Fleming, Odem-Davis, Rothmann and Shen2011; Piaggio et al., Reference Piaggio, Elbourne, Pocock, Evans and Altman2012).

There are surprisingly few RCTs of transdiagnostic approaches covering both depression and anxiety presentations. There may be value in future studies examining the effectiveness of treatments designed for both anxiety and depressive presentations, particularly given the high degree of co-morbidity between these.

Future studies should incorporate concurrent economic evaluations, as this has not yet been formally evaluated. There would be value in adding qualitative components into future trials to establish the acceptability of tCBT interventions for both clinicians and clients.

Conclusions

The evidence base for tCBT as applied to anxiety and depression is at an early stage of development. While there are encouraging signs that the approach may be effective, it is important to consider the methodological limitations of the primary studies, many of which may serve to artificially inflate the observed effect of the intervention. There is very limited evidence on the comparative effectiveness of disorder-specific and transdiagnostic CBT approaches and an absence of cost-effectiveness evidence. Despite the encouraging signs, there is as yet insufficient evidence to recommend the use of tCBT in place of disorder-specific CBT approaches.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jan Böhnke for language assistance with several German language papers.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication. The authors received no funding for this project.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1352465816000229

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.