A substantial proportion of the mass public endorses at least one specific conspiracy theory,Footnote 1 and many of these conspiratorial attitudes appear to be politically motivated. For example, Republicans are more likely to believe both that Barack Obama was born outside of the USFootnote 2 and that global warming is a hoax,Footnote 3 despite the release of a birth certificate and widespread scientific consensus, respectively. The intimate connection between partisanship and conspiratorial thinking highlights problems with the conceptual and empirical distinctions between partisan motivated reasoning and the tendency to subscribe to conspiracy theories. Are, for example, all conspiracy theorists partisan motivated reasoners? Or is it possible to be a ‘birther’ or a 9/11 ‘truther’ without being partisan?

We contend that much of conceptual and empirical opacity that gives rise to these questions is due to the measurement strategy most frequently employed to investigate these topics: survey questions about beliefs in specific conspiracy theories.Footnote 4 Inferences about the psychological characteristics of conspiracy theorists from stated beliefs in specific conspiracy theories are severely complicated by the influence of partisan or ideological motivated reasoning. In light of this problem, we argue that to understand better the nature, frequency and influence of conspiratorial thinking when it comes to the American mass public, we must first separate conspiratorial thinking conceptually and empirically from other known psychological states and identities – in particular, left/right political orientations.

In this article, we theorize about the relationship between these conceptual antecedents of specific conspiracy beliefs, in particular the conditions under which a general tendency toward conspiratorial thinking impacts specific conspiracy beliefs more than left/right political orientations do and vice versa. Though previous research has separately acknowledged the effects of conspiratorial tendencies and partisan and ideological orientations, very little work has specifically considered theoretically or empirically the dynamics between these constructs when it comes to specific conspiracy beliefs. As political conspiracy theories – those conspiracy theories that implicate or malign salient political figures and groups, or that are employed strategically by political actors for political ends – become common fixtures in modern political culture, a nuanced understanding of the relationship between the psychological state that is conspiratorial thinking and salient political orientations and identities becomes all the more necessary.

We demonstrate below that responses to questions about beliefs in specific conspiracy theories found on the 2012 American National Election Study (ANES) are the simultaneous – though, differential – products of both a general tendency toward conspiratorial thinking and partisanship. We use latent variable modeling techniques to estimate the effect of these two constructs on stated beliefs in specific conspiracy theories. Although beliefs in such overtly partisan conspiracies as ‘birtherism’ are found to be heavily influenced by partisanship, a more general conspiracy theory trait also substantively affects responses to each of the specific conspiracy theory questions employed. Furthermore, we find, using unique data gathered via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk crowdsourcing platform and an independent measure of conspiratorial thinking, that left/right political orientations are considerably more predictive of ‘birther’ beliefs than they are of conspiracy beliefs regarding the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The latter beliefs are much better explained by conspiratorial predispositions. These observations lend clarity to the substantive interpretation of specific conspiracy beliefs in the American political context, and suggest a nuanced relationship between two potential sources of such beliefs: left/right political orientations and conspiracism.

BACKGROUND

Recent research into conspiratorial thinking in the mass public reveals that partisans increasingly assent to conspiracy beliefs. Miller, Saunders and Farhart,Footnote 5 for instance, find that conspiratorial beliefs about topics and events such as the birthplace of Barack Obama, the inclusion of a ‘death panels’ provision in the 2010 Affordable Care Act, and misstatements on the part of the Bush administration regarding the existence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq are all substantially driven by ideological motivated reasoning. In a similar vein, Pasek, Stark, Krosnick and TompsonFootnote 6 find that ‘birther’ beliefs that Barack Obama was born outside of the US are informed by partisan motivated reasoning. They demonstrate that partisanship, ideological self-identifications, racial resentment toward blacks and negative feelings toward Barack Obama all significantly and substantively relate to ‘birther’ beliefs. Finally, Hartman and NewmarkFootnote 7 find – via Implicit Association Testing – that conservatives, Republicans, and those who simply did not like Barack Obama are more likely than others (particularly liberals and Democrats) to register erroneous beliefs that Obama is a Muslim.

One reason left/right political orientationsFootnote 8 may be driving conspiracy beliefs is that partisanship is largely a process of ‘motivated reasoning.’ Motivated reasoning is a subconscious psychological mechanism by which individuals differentially process and integrate information based on their prior beliefs, attitudes and emotions, and it pervades the psychology of citizens’ reasoning about political phenomena and stimuli.Footnote 9 The effects of partisan motivations in attitude formation and expression have been extensively documented with respect to many different phenomena.Footnote 10 Kraft, Lodge and TaberFootnote 11 and Blank and ShawFootnote 12 even demonstrate that partisan motivations extend to the (mis)interpretation of facts produced by non-partisan/ideological figures, namely scientists and other types of experts.

There is an alternative explanation for the existence of seemingly partisan conspiracies: a general inflammation of what Richard Hofstadter called the ‘paranoid style’.Footnote 13 Following Hofstadter’s ‘paranoid style’, conspiratorial thinking is best understood as a style of reasoning about the political world and our place in it.Footnote 14 Numerous empirical studies on conspiratorial thinking largely agree that a conspiracy theory is an interpretation of an event or public action centering on a secret plan of a small group of individuals or groups, whose goals and intentions are partially hidden, though usually directed at assuming power.Footnote 15 Like partisanship, conspiratorial thinking is a ‘perceptual screen’ through which information is filtered and the world is interpreted.Footnote 16 According to Goertzel,Footnote 17 conspiratorial thinking is a ‘monological’ belief system, where an individual differentially assesses (or ignores) evidence that counters prior beliefs. A monological belief system is one containing consistent and coherent beliefs, but at the expense of maintaining them against countervailing evidence. Empirical studies on conspiracism present a general psychological profile of individuals who practice such conspiratorial thinking: these individuals are more authoritarian, less trusting in government, less educated and politically sophisticated, more religious, and oftentimes belong to socio-economic and socio-demographic minority groups.Footnote 18

This type of thinking is largely a sign of dis-identification with mainstream politics, which makes it a prime candidate for an alternative explanation to the political motivated reasoning view. It could, in other words, be the case that the influx of conspiracies today is due to the rise in the paranoid style, or conspiracism, and not simply partisan or ideological polarization. Perhaps the most important aspect of the paranoid style is that conspiratorial thinking directly relates to a feeling of being branded a political outsider.Footnote 19 While the specific conspiracy theories employed in previous studies have varied widely in their content and socio-political context,Footnote 20 none of them have uncovered a relationship between partisan attachments and a tendency toward conspiratorial thought.Footnote 21 This is not to say that partisans cannot subscribe to a specific conspiracy theory (as Miller, Saunders and Farhart,Footnote 22 for instance, show), but it does raise the important question as to the primary psychological motivation behind that belief: partisan affect or conspiracism?

Of course, neither view necessarily entails denying the other: an individual may hold a conspiracy belief because of left/right political orientations and conspiracism. More specifically, it could be the case that even mainstream political conspiracy theories – those for which a salient, highly visible partisan figure or group is implicated or maligned – require some non-trivial level of individual conspiratorial tendencies beyond merely a congruent political orientation or identity. For example, Republicans who subscribe to ‘birtherism’ likely do so not merely due to the fact that a partisan out-group member – Barack Obama – is maligned by the conspiracy, but because they also tend to interpret the world around them through the lens of conspiracy. Yet, while this perspective that both conspiratorial and political orientations matter strikes us as more likely than a situation in which either one of the orientations operates in a vacuum, current models of conspiracy beliefs exclude one or the other.

Put simply, the careful first step of empirically differentiating, and subsequently modeling, the sources of beliefs in specific conspiracy theories has not been made. Without this differentiation, we lose valuable insight into the relationship between conspiratorial thinking and left/right political orientations, and promote confusion about the psycho-political sources of stated conspiracy beliefs. In the two studies that follow, we use two different datasets and analytic techniques to investigate the foundations of specific conspiracy endorsement, and consider the distinct, heterogenous effects of conspiratorial and left/right political orientations on conspiracy beliefs.

STUDY 1

In order to examine the dynamic relationship between partisanship and conspiratorial thinking, we use the four conspiracy items included on the 2012 ANES post-election survey. These questions ask about the extent to which respondents believe in conspiracies about the birthplace of Barack Obama (henceforth referred to as the ‘birther’ theory), the inclusion of a provision authorizing the creation of panels to make end-of-life decisions for people on Medicare in the 2010 Affordable Care Act (henceforth referred to as the ‘death panel’ theory), the amount of related knowledge the federal government possessed prior to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 (henceforth referred to as the ‘truther’ theory), and the role of the federal government in breaching the flood levees in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina (henceforth referred to as the ‘levee breach’ theory).Footnote 23 The responses to these questions are coded such that higher values denote more conspiratorial attitudes.

We note that even though two of these conspiracy theories are, on their face, much more likely to be believed by Republicans and/or conservatives than Democrats/liberals, we do not propose that Republicans/conservatives are more conspiratorial than Democrats/liberals. The 2012 ANES survey was fielded during the presidency of a Democratic president, and, as such, there were simply more conspiracies implicating Obama and Democrats than there were implicating Republicans. Thus, even though the conspiracy belief questions we employ in this study are representative of the salient conspiracies of the time, they are not necessarily representative of all conspiracies at any given time. We do not view this as a flaw in our design, but a necessary condition of our analyses.

Analysis and Results

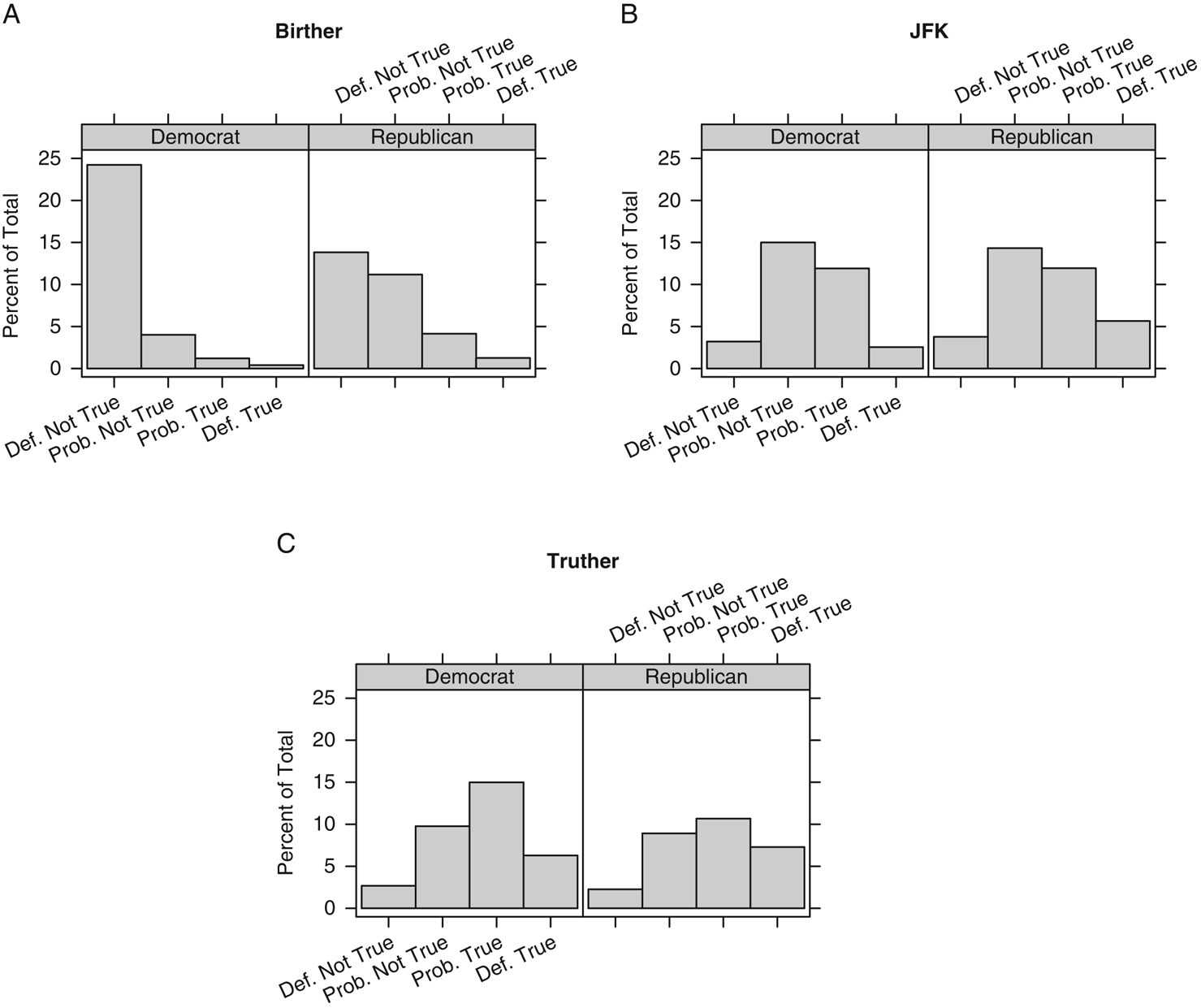

The distributions of responses to these questions, stratified by Democratic and Republican partisanship, are presented in Figure 1.Footnote 24 Though the exact shape of these distributions varies, each of the distributions, on average (across partisan orientations, that is), exhibits some degree of negative skew, effectively communicating that less than half of individuals believe any of these specific conspiracy theories. Even so, however, the degree of support for these conspiracy theories varies tremendously, with non-trivial proportions of individuals either fully supporting or exhibiting uncertainty about a given conspiracy.

Fig. 1 Distributions of responses to ANES specific conspiracy items

The shape of the distributions also vary by partisanship. Although Democrats may be slightly more likely to ascribe to beliefs in the ‘truther’ and ‘levee breach’ conspiracy theories, we observe stark differences between partisans when it comes to the ‘birther’ and ‘death panel’ conspiracy theories. More specifically, Republicans are significantly more likely than Democrats to ascribe to conspiracy beliefs regarding the birthplace of Obama and death panels. This is a first piece of evidence suggesting the partisan nature of some specific conspiracy theories, but with the added nuance that the strength of the partisan content can vary across conspiracy theories.

We continue our analysis by using factor analysis to examine the extent to which the observed responses to the four ANES conspiracy items are simultaneously the product of two latent traits: conspiratorial thinking and partisanship.Footnote 25 Such an analysis could produce several different results. On the one hand, if the registered beliefs in these specific conspiracy theories really are the products of only a ‘monological’ belief system, as some conspiracy research theorizes, then we would expect that a single factor captures most of the shared variance in the responses to the items.Footnote 26 On the other hand, if responses to the conspiracy items are strictly partisan or ideological in nature, then we might expect a single factor with both positive and negative factor loadings, assuming, as others haveFootnote 27, that both Democratic and Republican conspiracies are represented in this set.Footnote 28 Finally, the factor analysis could produce a solution where more than one factor is required to accurately describe the underlying structure in the specific conspiracy data.

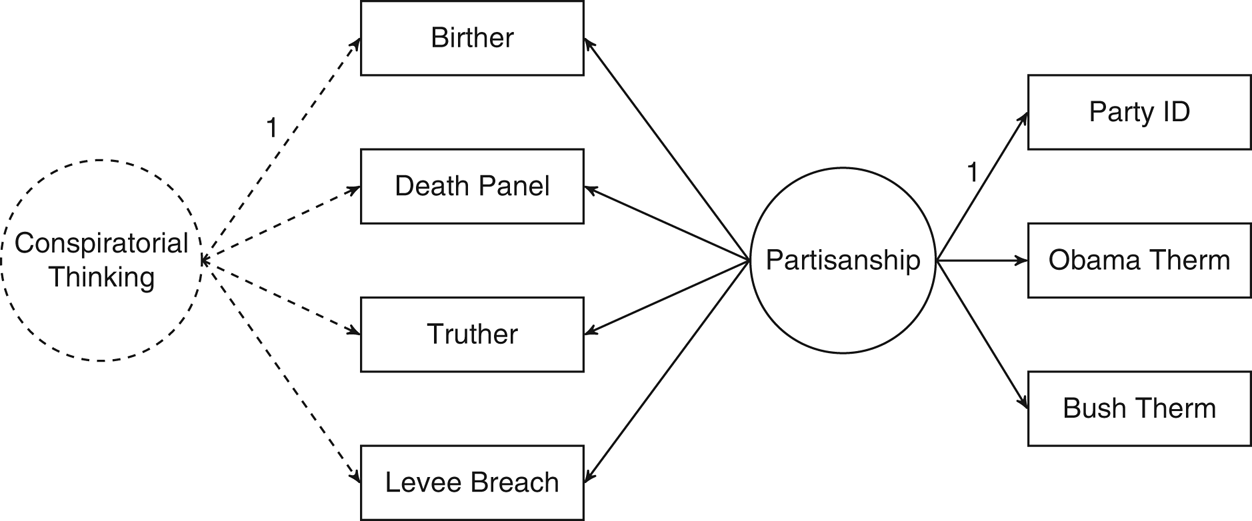

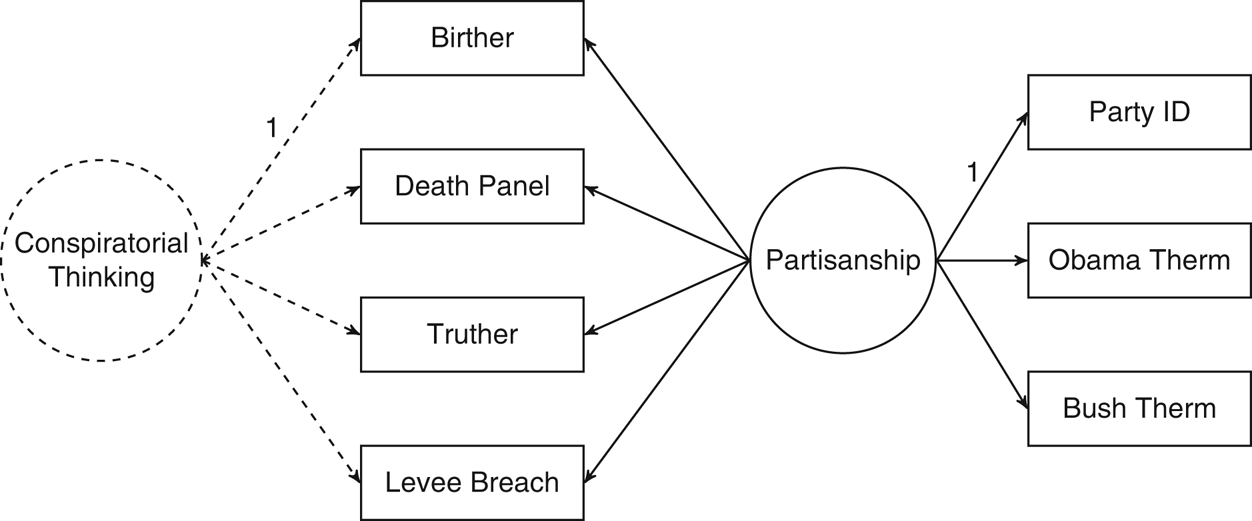

We find this final possibility most plausible. Our theoretical model of the sources of variation in the responses to the conspiracy items might look something like the path diagram in Figure 2. According to both our theoretical expectations, two latent variables produce beliefs in all four of the specific conspiracy theories: conspiratorial thinking and partisanship. More than merely exhibiting a two-factor structure, however, we expect conspiratorial thinking and partisanship to differentially affect the specific conspiracy beliefs we employ. On the one hand, the ‘birther’ and ‘death panel’ conspiracies are about highly salient political figures and policies at the time the survey was fielded. Though we expect the general tendency toward conspiratorial thinking to affect beliefs about these specific conspiracies, we also expect partisanship to have a substantially larger effect. Indeed, partisan motivated reasoning should be activated much more easily when the conspiracies specifically implicate members of the partisan out-group. These differences should manifest themselves in the magnitudes of the standardized factor loadings (more below). On the other hand, we might expect conspiratorial orientations to have a larger effect on ‘truther’ and ‘levee breach’ conspiracy beliefs since only ‘the government’ or ‘senior officials’ are referenced in the questions about these conspiracies. Although George W. Bush presided over the 9/11 terrorist attacks and Hurricane Katrina, neither he, nor the Republican Party, is specifically implicated in the conspiracy theories constructed around these events. Therefore, we expect general conspiratorial orientations to play a larger role in explaining variation in beliefs about these conspiracy theories than partisanship.

Fig. 2 Two-factor model of the competing sources of variation in specific conspiracy beliefs

All effects associated with the conspiratorial thinking factor are dashed, while those associated with partisanship are solid. In addition to the four specific conspiracy items, we include three additional items related to partisanship in the partisanship factor only: partisan identification (measured via the standard seven-point scale), feelings toward Barack Obama, and feelings toward George W. Bush (both of which are measured via the familiar feeling thermometer items).Footnote 29 The primary purpose for including these indicators is to be able to identify the partisanship factor. By including overwhelmingly partisan items in this component of the model, we can be sure that we know which factor should be interpreted as partisanship, and which, therefore, can be interpreted as conspiratorial thinking. Provided that one of the influences on beliefs in specific conspiracy theories truly is partisanship, the inclusion of these items will be statistically innocuous while providing useful inferential leverage with respect to interpretation of estimates. Of course, if partisanship is not really a source of variation in specific conspiracy beliefs, then the model should fit the structure of the data very poorly and the fit indices should reflect that the model is incorrect and should be respecified.

We chose the partisan identification item because it is the most widely accepted single indicator of partisanship. We employ the Obama and Bush feeling thermometers because they provide measures of affect toward highly visible partisan figures from both major political parties.Footnote 30 We elected to include affective evaluations of George W. Bush rather than Mitt Romney, for instance, because while we certainly wanted some counterbalance to the Obama thermometer, we also wanted to take into account feelings toward (a) a recent president, who (b) presided over two of the specific conspiracy theories included in our model – the ‘truther’ and ‘levee breach’ conspiracy theories. Since Bush’s legacy is intimately colored by the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the administration’s handling of the fallout from Hurricane Katrina, we believe that individual feelings toward him help provide a strong test of our theory that partisan orientations are an important antecedent to (some) specific conspiracy beliefs. The ‘1’s by the ‘Birther’ and ‘Party ID’ paths indicate that the associated factor loadings should be constrained to 1, effectively scaling the respective latent factors to those variables. Finally, the two factors – conspiratorial thinking and partisanship – are constrained to be orthogonal, or uncorrelated, per recent research that employs unique measures of latent conspiracism.Footnote 31

The estimates of the model in Figure 2 are presented in Table 1.Footnote 32 Every factor loading for both the conspiratorial thinking and partisanship factors is statistically significant at the p<0.001 level (assuming a two-tailed test). Traditional measures of fit suggest that this model accounts for the underlying structure in the data very well. The Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is 0.052 and the large p-value associated with this estimate (0.345) suggests that we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the true RMSEA is equal to or less than 0.05. Since RMSEAs of 0.05 or less are most desirable,Footnote 33 we have a first piece of promising evidence for an appropriate model.Footnote 34 Both the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) provide confirmatory evidence of a superior model fit as well. The rule of thumb regarding these fit indices is that values greater than 0.95 suggest very good model fit.Footnote 35 The values for both indices surpass this cutoff. Although the chi-squared test for equivalence of the observed and model-implied covariance matrices is statistically significant, the chi-squared test is known to be particularly sensitive to sample size (among other peculiarities of the data), and we employ an unusually large sample here (4,790 individuals). Thus, we are not worried that this measure of fit does not fully comport with the other indicators.

Table 1 Structural Equation Model Estimates and Fit Statistics

Standardized MLE coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. All estimates statistically significant at the p<0.001 level with respect to a two-tailed test.

Though fit indices suggest a well-performing statistical model and all factor loadings are statistically significant, there is variation in the magnitude of the standardized loadings that can aid our interpretation of the relationships between conspiratorial thinking, partisanship, and specific conspiracy beliefs. Consider first the loadings associated with the ‘birther’ and ‘death panel’ conspiracies. In both cases the loadings on the partisanship factor are larger than the loadings on the conspiratorial thinking factor. Larger loadings denote stronger correlations between observed indicators (conspiracy beliefs) and latent factors (partisanship and conspiratorial thinking). Put another way, variation in beliefs about these two conspiracy theories are more the product of partisanship than conspiratorial thinking, though both constructs are non-trivially predictive.Footnote 36 This comports with our earlier examination of the distributions of response to questions about these two conspiracy theories. In both cases we could see variation in responses by partisanship. The opposite case was true for the ‘truther’ and ‘levee breach’ conspiracy theories. With respect to those conspiracy theories, there is a great deal of overlap in conspiratorial beliefs by partisan affiliation. As with the ‘birther’ and ‘death panel’ conspiracy theories, these basic univariate patterns are reflected in the factor loadings. Indeed, the loadings for both the ‘truther’ and ‘levee breach’ conspiracy theories are much larger with respect to the conspiratorial thinking factor than the partisanship factor. Note also that the loadings of these two conspiracy theories on the partisanship factor are negative, suggesting that they are associated more with the Democratic Party than the Republican Party, opposite of the ‘birther’ and ‘death panel’ conspiracy theories.

We do not intend to suggest that because the loadings which point in the Republican direction are larger than those that point in the Democratic direction Republicans should be viewed as more conspiratorial than Democrats. Indeed, we are not concerned here with the direction of the loadings, but the differential strength of the loadings across specific conspiracy theories. It is likely the case that partisanship is so strongly related to the Republican conspiracy theories just as much because of their salience at the time (especially in 2012 when the survey was conducted) as their partisan direction. Indeed, Uscinski and ParentFootnote 37 propose in their ‘losers hypothesis’ just such a socio-political context effect when it comes to the relationship between partisanship and conspiracy beliefs.

Taken together, we have strong evidence that responses to questions about beliefs in specific conspiracy theories are influenced not only by conspiratorial thinking, but partisanship. This poses a problem for researchers seeking to understand the nature of conspiratorial thought in American mass opinion, as our indicators of conspiracism non-trivially evoke partisanship rather than merely conspiracism. Should, then, researchers interested in studying conspiratorial thinking employ questions about the birthplace of Barack Obama to that end? Our observations from this study suggest that they should not. Indeed, our results demonstrate that conspiracism has far less to do with such beliefs than does partisanship – an orthogonal, and completely distinct psycho-political orientation. In the next study, we further unpack the relationships between conspiratorial thinking, left/right political orientations and beliefs in specific conspiracy theories by employing measures of left/right orientations and conspiratorial thinking that are estimated independently from specific conspiracy beliefs.

STUDY 2

In this second study, we use use Amazon’s Mechanical Turk crowdsourcing platform to gather data about specific conspiracy beliefs and general conspiratorial orientations in order to further investigate the differential roles of conspiratorial thinking and partisan or ideological motivating reasoning in explaining conspiracy beliefs. Using a distinct measure of conspiratorial thinking that is not determined by the specific conspiracy belief questions, as was the case in Study 1, provides us the analytical leverage to more fully consider the differential effects of conspiratorial and political orientations on different types of specific conspiracy beliefs, in the face of controls for other types of orientations, attitudes, and demographic characteristics.

We employ a measure of conspiratorial thinking similar to those developed and validated by Uscinski and colleaguesFootnote 38 and Bruder and colleagues,Footnote 39 along with multivariate statistical methods, to examine where and to what extent latent conspiracism explains specific conspiracy beliefs.Footnote 40 We are particularly focused on comparing the effects of conspiratorial thinking to those of partisan and ideological self-identifications.

The statements we use to estimate general conspiratorial orientations are as follows:

In national politics, events never occur by accident.

Politicians rarely lie.

Unseen patterns and secret activities can be found everywhere in politics.

Government institutions are largely controlled by elite outside interests.

Respondents were asked to rate the extent to which they (dis)agreed with each of the preceding statements on a five-point Likert-type scale with a middle category labeled ‘neither agree nor disagree’. The scale is strongly unidimensional; indeed, the first factor of an exploratory factor analysis accounts for approximately 85 per cent of the total variance in the items. And, as previous work employing similar measures has found and the factor model we estimated above suggests, conspiratorial thinking is uncorrelated with partisan (r=0.021) or ideological (r=−0.007) self-identifications at the p<0.05 level.Footnote 41

The data employed in this study come from a sample of 1,543 US adults gathered via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (heretofore ‘MTurk’) platform from 19 to 29 April 2016. Individuals where offered $0.80 to complete a six to eight-minute survey in which they would be asked their ‘opinions about politics and the news’. As is customary with MTurk samples, individuals in this study tended to be a bit more liberal, have slightly higher levels of educational attainment, and be younger than the average adult American. Table 2 below lists the codings/ranges, means, and standard deviations of a couple of key demographic characteristics of the individuals in this sample, in addition to the other substantive variables that will be employed in the analyses below.

Table 2 Demographic Composition and Variables of Interest in MTurk Sample

Total n=1,543.

Regardless of the MTurk sample, we have little reason to believe that these individuals think about conspiracy theories fundamentally differently than a more representative sample might. Furthermore, we have no reason to believe that the partisans in this sample would behave significantly differently than more ‘average’ partisans. As a check on this claim, we display in Figure 3 the distributions of responses to the three specific conspiracy belief questions queried in this survey – two of which overlap with those on the 2012 ANES – stratified by partisanship. The question wording and response categories for the ‘birther’ and ‘truther’ conspiracy questions are nearly identical to those employed in the 2012 ANES, and the JFK conspiracy question was constructed in the image of former conspiracy questions (e.g. the structure of the question and response options is the same). Full question wordings are presented in the Supplemental Appendix.

Fig. 3 Distributions of responses to MTurk specific conspiracy items

The distributions of responses in the MTurk sample are extremely similar to those in the 2012 ANES sample; indeed, the shapes of the distributions, for the whole sample and by partisanship, are nearly identical. The distribution of responses to the question about ‘birther’ beliefs is strongly positively skewed, with Democrats being much less likely to express belief in the theory. As with the ANES sample, the distribution of beliefs in the ‘truther’ theory are slightly negatively skewed for all individuals, with only minor differences between members of partisan groups. We take these similarities to indicate that neither the results presented below nor the conclusions we make from them would differ substantially in a more representative sample. Finally, individuals were slightly more likely to express belief in the JFK conspiracy than they were with regard to the ‘truther’ theory, and only extremely minor partisan divisions emerged.

Analysis and Results

In order to investigate the differential roles of conspiratorial thinking and partisan and ideological self-identifications on specific conspiracy beliefs, we specified a set of ordered logistic regression models with beliefs in specific conspiracy theories as the dependent variables. In each of thee models we expect conspiratorial thinking to be a statistically significant, and substantively strong (at least with respect to other variables in the model), predictor of specific conspiracy beliefs. As we observed in Study 1, however, partisan or ideological self-identifications should be a statistically significant and substantively meaningful predictor of ‘birther’ beliefs. That same may be true of ‘truther’ beliefs, though this relationship is more tenuous given the relatively weak loading of the ‘truther’ conspiracy on the partisanship factor compared to the conspiratorial thinking factor. We are agnostic about the role of partisan or ideological self-identifications in predicting JFK conspiracy beliefs. On the one hand, JFK was a Democrat, so Democrats may be more likely to believe in conspiracies surrounding his assassination. On the other hand, the JFK conspiracy is likely not a particularly salient one in 2016, and many younger individuals may even be unaware of the partisan affiliation of JFK. Regardless of the effect of partisanship or ideological self-identifications, we expect conspiratorial thinking to predict JFK conspiracy beliefs.

In addition to the measures of conspiratorial thinking, partisanship, and ideological self-identifications, we included measures of authoritarianism, political knowledge, educational attainment, age, gender, and race.Footnote 42 We have few specific hypotheses regarding these control variables. Previous literature has found a relationship between authoritarianism and conspiracy belief,Footnote 43 but – to our knowledge – only one instance also accounted for partisan or ideological self-identifications.Footnote 44 Thus, we might observe a positive relationship between authoritarianism and specific conspiracy beliefs, or the relationship may be a spurious one dominated by partisanship and ideological self-identifications. As for political knowledge and educational attainment, we might expect that more knowledgable and educated individuals express less conspiratorial beliefs – either because they know that holding conspiracy beliefs is frowned upon and, therefore, choose to eschew them, or because they have the knowledge necessary to navigate the confusing sea of political information that may cause others to give up and assume the worst. On the other hand, true conspiracy theorists oftentimes appear to be relatively well informed about the everyday goings on of governmental authorities. We remain agnostic on this point, as does the literature as we understand it. We are also agnostic about the remaining demographic controls.

The regression models appear in Table 3.Footnote 45 The first, third, and fifth columns of Table 3 feature the logit coefficients along with standard errors and markers for statistical significance. In order to facilitate the interpretation of the relative magnitude of effects, we include odds ratios in the second, fourth, and sixth columns. The first notable feature of each of the models is that the estimate associated with conspiratorial thinking is statistically significant (at the p<0.05 level) and positive, denoting that as an individual’s level of conspiratorial thinking increases, so too does their beliefs in the ‘birther’, ‘truther’, and JFK conspiracies, on average. Neither partisanship nor ideological self-identifications are statistically significant predictors of the ‘truther’ or JFK conspiracy beliefs, though both partisan and ideological self-identifications statistically significantly predict ‘birther’ beliefs. Since both partisanship and ideological self-identifications are coded such that higher positive values denote increasingly Republican/conservative identifications and lower negative values denote increasingly Democratic/liberal identifications, the positive coefficient associated with the partisan and ideological self-identification variables suggests – precisely as we expected – that conservatives are more likely than liberals to express ‘birther’ beliefs.

Table 3 Ordered Logistic Regressions of Specific Conspiratorial Beliefs on Conspiratorial Orientations, Political Self-Identifications, and Controls (MTurk)

Logit coefficients with standard errors in parentheses in odd columns.

Odds ratios in even columns.*p<0.05 w/ respect to a two-tailed test.

That conspiratorial thinking is statistically significant in each of the models lends some credence to our speculation that such a general orientation may operate as a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for some specific conspiracy beliefs.Footnote 46 When it comes to less-partisan theories like the JFK and ‘truther’ conspiracy theories, general conspiratorial orientations are necessary and sufficient. When it comes to overtly partisan theories like the ‘birther’ conspiracy theory, conspiratorial thinking serves as a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for conspiracy belief. In this case, the individual must possess the directionally congruent political orientation or identity – Republicanism and/or conservatism – beyond some non-trivial level of conspiratorial thinking.

Neither authoritarianism nor race are significantly related to beliefs in any of the conspiracy theories, controlling for other factors. Knowledge is significantly negatively related to ‘truther’ and ‘birther’ beliefs and educational attainment is negatively related to ‘truther’ beliefs, providing partial support for the idea that more knowledgeable and educated individuals have the tools to appropriately interpret the political world and circumvent the confusion that may promote conspiracy beliefs. Finally, we observe that younger individuals are more likely to believe in the ‘truther’ conspiracy, while older individuals are more likely to believe in the JFK conspiracy theory. This pattern reveals an interesting generational effect of conspiracy beliefs – individuals may be more likely to believe in conspiracy theories surrounding events that they personally remember and are integral parts of the political history that characterizes their generation.Footnote 47

Discussion of statistical significance and directionality aside, how much predictive power do the aforementioned variables hold when it comes to specific conspiracy beliefs? An inspection of the odds ratios reveals that conspiratorial thinking is the strongest predictor of ‘truther’ and JFK conspiracy beliefs, and third strongest predictor of ‘birther’ beliefs next next to ideological and partisan self-identifications.Footnote 48 The odds ratio of conspiratorial thinking in the ‘truther’ model tells us that, on average, for a one unit increase in conspiratorial thinking, the odds of the respondent registering the most conspiratorial response (coded a 4) are 1.234 times greater than those associated with registering a less conspiratorial response (those coded 3, 2, or 1), holding other variables constant. This odds ratio is nearly double that associated with either of the other two statistically significant predictors of ‘truther’ beliefs, knowledge and education. Carrying this interpretation forward, conspiratorial thinking is the strongest predictor of JFK conspiracy beliefs, and partisan and ideological self-identifications edge out conspiratorial thinking as the strongest predictors of ‘birther’ beliefs, as we expected.

Since odds can be unintuitive for some readers, we provide an alternative method of effect interpretation in Table 4. The quantities in the table are first differences. They represent the average change in the probability of respondents selecting the most conspiratorial response (coded a 4) when varying each of the three key independent variables from their minimum value to their maximum value, holding all other variables at their mean (for continuous and ordinal variables) or mode (for dichotomous variables). Consider, for example, the first column. The average probability of respondents registering the most conspiratorial response to the ‘truther’ question (that senior officials definitely knew about the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 before they happened) increases by 0.154 when we vary conspiratorial thinking from its minimum value to its maximum value, holding other variables at their means/modes. As we might expect, this is the only significant change in probability in this column since neither partisan nor ideological self-identifications were statistically significant predictors of ‘truther’ beliefs in the model presented in Table 3.

Table 4 Change in Probability of Providing Most Conspiratorial Response Varying Conspiratorial Thinking, Partisanship, and Ideological Self-Identifications from Minimum to Maximum Values

*Denotes P<0.05 w/ respect to a two-tailed test.

Conspiratorial thinking has an even larger effect for JFK conspiracy beliefs. In this case, the average probability of respondents registering the most conspiratorial response to the JFK question (that Lee Harvey Oswald definitely didn’t act alone in assassinating JFK) increases by 0.264 when we vary conspiratorial thinking from its minimum value to its maximum value, holding other variables at their means/modes. This is quite a large effect. Indeed, it is striking that a relatively parsimonious model of data comprised of self-reports is able to account for any variance in what many consider to be a relatively radical belief. Yet, we see that there is a 26 per cent increase in the likelihood of registering the most conspiratorial response to the JFK question as individuals become more conspiratorial, according to the measure of conspiratorial orientations that we employ here. Finally, all three variables of interest significantly increase the probability of registering the most conspiratorial response to the ‘birther’ question (that Barack Obama was definitely born outside of the US). More specifically, average probability of respondents registering the most conspiratorial response increases by 0.011, 0.016 and 0.037 when conspiratorial thinking, partisan self-identifications and ideological self-identifications, respectively, are varied from their minimum to maximum values.

CONCLUSION

Given the empirical patterns observed in both studies, we have strong evidence for the statistically simultaneous, though substantively differential, effects of latent conspiracism and partisan and ideological self-identifications on specific conspiracy beliefs. In Study 1, we decomposed beliefs in specific conspiracy theories in order to explore the sources of variance in these beliefs. The two-factor model including partisanship and conspiratorial thinking serving as sources of variation across all conspiracies fitted the data well. Though all factor loadings were statistically significant, ‘birther’ and ‘death panel’ conspiracy beliefs loaded more strongly on the partisanship factor than the conspiratorial thinking factor, and ‘truther’ and ‘levee breach’ conspiracy beliefs loaded more strongly on the conspiratorial thinking factor than the partisanship factor. In Study 2, we employed independent measures of partisanship and conspiratorial thinking, and found latent conspiracism to be a significant predictor of ‘truther’, ‘birther’ and JFK conspiracy theories. Beyond statistical significance, we found that while conspiratorial thinking was the strongest predictor or ‘truther’ and JFK conspiracy beliefs, partisan and ideological self-identifications were stronger predictors of ‘birther’ beliefs than was conspiratorial thinking. The findings across studies – i.e. across samples, measurement strategies, and modeling techniques – are congruent.

That beliefs in specific conspiracy theories are significantly the product of latent orientations beyond the assumed conspiracism should cause conspiracy researchers to consider strongly which measurement strategies they utilize and how they employ them. Indeed, previous work has either assumed the domineering effect of partisanship over conspiratorial thinking,Footnote 49 or just the opposite – not even including it in the various models of conspiracy belief (e.g. nearly all work on the topic conducted by social psychologists). More than any statistical problems associated with this measurement strategy, we wish to emphasize that the resultant theoretical opacity is of much greater consequence.

Labeling someone who ascribes to a particular conspiracy theory either a ‘conspiracy theorist’, suffering from a heated paranoid psychopathology, or a ‘partisan’, driven by group-based partisan affect, is to miss the nuance of the relationship between the general psychological orientation that is conspiratorial thinking and political motivated reasoning. But, labels matter. So, too, does this distinction between orientations and observable indicators of such orientations. We have demonstrated that specific conspiracy beliefs may be heterogeneously indicative of latent conspiracism, and in some instances – such as with ‘birther’ beliefs – nearly devoid of it altogether. As such, future research should, minimally, both theoretically and empirically provide for the effects of non-conspiratorial attitudes, traits and orientations on beliefs in specific conspiracy theories, and, maximally, employ alternate measurement strategies. It is this later goal that conspiracy researchers have begun to advance, particularly through the use of questions designed to uncover a general conspiratorial thinking trait.Footnote 50