Introduction

Delirium is an acute neurocognitive disorder in medically ill patients, characterized by disturbances in consciousness or attention and cognition, caused by different underlying etiologies. Typically, delirium is characterized by an abrupt onset and fluctuating course (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Maclullich and Laurila2008).

The etiology of delirium is complex and usually multifactorial, resulting from a combination of risk factors, typically termed either “predisposing” or “precipitation factors” (Inouye et al., Reference Inouye, Westendorp and Saczynski2014). Predisposing factors refer to medical conditions and comorbidities that pre-exist in a patient — like male gender, older age, as well as hearing, visual, and cognitive impairment — and increase a patient's risk of developing delirium. In contrast, precipitating factors are contributing risk factors that are critical in the activation of a delirium episode (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lawlor and Ryan2018). Precipitating factors affect neurotransmitter, neuroendocrine, and/or neuroinflammatory pathways and cause endocrine, metabolic, and electrolyte derangements that contribute to delirium (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Shin and Bruera2013; Bush et al., Reference Bush, Tierney and Lawlor2017). The most common precipitating risk factors for delirium can be roughly categorized into environmental factors, iatrogenic factors, medications (e.g., polypharmacy, psychoactive drugs, sedatives, and hypnotics), neurological disease, comorbid illness, organ failure, metabolic syndromes, including electrolyte and endocrine abnormalities, and surgery (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Tierney and Lawlor2017, Reference Bush, Lawlor and Ryan2018).

Delirium is prevalent in palliative care patients and can cause high levels of distress among patients, caregivers, and clinicians (Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Gagnon and Mancini2000; Finucane et al., Reference Finucane, Lugton and Kennedy2017; Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Rutkowski and MacDonald2019). Incidence and prevalence rates for delirium in palliative care patients are high, ranging from 13% to 85% and from 3% to 45%, respectively (Hosie et al., Reference Hosie, Davidson and Agar2013; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, O'Regan, Caoimh, Clare, O'Connor, Leonard, McFarland, Tighe, O'Sullivan, Trzepacz, Meagher and Timmons2013; Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Davis and Ansari2014; de la Cruz et al., Reference de la Cruz, Ransing and Yennu2015; Mercadante et al., Reference Mercadante, Adile and Ferrera2017), depending on the diagnostic tool used, health care environment and disease stage. Moreover, the prevalence of delirium in terminally ill patients can increase up to 90% (Casarett and Inouye, Reference Casarett and Inouye2001; Hosie et al., Reference Hosie, Davidson and Agar2013). Delirium is associated with an unfavorable short- and long-term prognosis, including prolonged hospital length of stay (LOS), cognitive decline, and increased morbidity, need for long-term care institutionalization, and mortality (Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Davis and Ansari2014; Boettger et al., Reference Boettger, Jenewein and Breitbart2015; Dani et al., Reference Dani, Owen and Jackson2017; Diwell et al., Reference Diwell, Davis and Vickerstaff2018; Tosun Tasar et al., Reference Tosun Tasar, Sahin and Akcam2018; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Brovman and Urman2019). In addition, delirium in palliative care patients is associated with a lower median overall survival relative to those without delirium (de la Cruz et al., Reference de la Cruz, Ransing and Yennu2015). Furthermore, delirium in the medically ill is highly correlated with increased healthcare requirements and cost (Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Schurch and Boettger2018). For the purposes of this study, the term “palliative care patients” refers to patients with terminal diseases that are unlikely to be cured or controlled with treatment and are likely to cause death (with a prognosis of weeks to 6 months) (Hui et al., Reference Hui, Nooruddin and Didwaniya2014; National Cancer Institute, 2019).

Despite the high prevalence of delirium in palliative care patients and its prognostic importance, little is known about risk factors, early detection, prevention, management, and prognostic outcomes of delirium in this vulnerable patient population. In view of the adverse impact of delirium on the quality of life of the patients and the substantial burden for caregivers, as well as the severe economic consequences, it is necessary to understand palliative care patients' risk factors for and outcomes of delirium to improve prevention, detection, and management of hospital-acquired delirium at the end of life. Identifying predisposing and precipitating risk factors for delirium in palliative care patients is an important step for the development of more effective delirium treatments and preventative strategies in palliative care patients.

This study sought (1) to examine the prevalence of delirium in palliative care patients; (2) to assess for differences with respect to predisposing and precipitating factors in delirious vs. non-delirious palliative care patients; and (3) to identify the most relevant predisposing and precipitating risk factors as predictors of delirium in palliative care patients.

Methods

Study design, patients, and procedures

The present study is a sub-analysis of the Delir-Path, a large prospective observational project which aimed to improve the prevention and facilitate the early detection and management of hospital-acquired delirium in surgical and intensive care patients (Schubert, Reference Schubert2013–2015). In the Delir-Path project, patients were recruited across 43 departments at the University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland, a tertiary care center with 900 beds. During the period between January 2014 and December 2014, 39,432 patients with clinical evidence of incident delirium were considered eligible for inclusion. The following exclusion criteria — i.e., (1) age <18 years; (2) LOS <1 day; and (3) missing Delirium Observation Screening (DOS) scores — resulted in a total of 29,278 eligible patients [results published elsewhere (Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Schurch and Boettger2018)]. Out of these, 410 patients were managed at the Competence Center for Palliative Care (Figure 1). Demographic and medical information was retrieved via the electronic medical chart (Klinikinformationssystem, KISIM, CisTec AG, Zurich).

Fig. 1. Screening algorithm for the Delir-Path.

The DOS tool was used to screen patients for delirium and was routinely administered thrice daily by trained study nurses during the first three days of admission to all patients ≥65 years and to patients younger than 65 years on clinical suspicion of incident delirium. Once delirium was detected, DOS was continued three times daily until delirium remission. The training of nursing staff was conducted within a 4-h session with mandatory preceding eLearning and literature research, with an assessment of training success. The nurses were educated with case-reports and state-of-the-art lectures on epidemiology, as well in the diagnostic criteria for delirium, and trained to obtain delirium scores.

All study procedures performed were in accordance with the World Health Organization's Declaration of Helsinki. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Canton Zurich (KEK), Switzerland (KEK-ZH-Nr. 2012-0263). A waver of informed consent was obtained from the KEK. Data were collected and reported in accordance with guidelines set by the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement (STROBE, 2009).

Characterization of predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in palliative care patients

A number of predisposing and precipitating factors have been described for palliative care patients (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Shin and Bruera2013; Inouye et al., Reference Inouye, Westendorp and Saczynski2014; Hosker and Bennett, Reference Hosker and Bennett2016; Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lawlor and Ryan2018; Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Schurch and Boettger2018; Zipser et al., Reference Zipser, Deuel and Ernst2019). For the purpose of this study, characterization of the predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in palliative care patients was based upon the formation of diagnostic clusters, according to the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) (World Health Organization, 1992) and related health problems (Table 1). Frailty is a common syndrome in palliative care patients and characterized by a decline in physiological functioning, reduced strength and endurance, and impaired mobility (Moorhouse and Rockwood, Reference Moorhouse and Rockwood2012). For the purposes of this study, frailty was assessed across the component “mobility” (impaired vs. not impaired).

Table 1. Diagnostic clusters with their respective included diagnoses according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10)

Determination of delirium

The assessment of delirium was based on the DOS scale and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5) delirium construct “disturbances in alertness and attention” (European Delirium and American Delirium, 2014). Indebted to the screening algorithm, only 10,906 out of 28,806 patients were screened, and the DOS detected 91% of patients diagnosed with delirium by psychiatrists. For the unscreened patients, a DSM-5-based construct — alertness or inattention and cognitive impairment — was created from the respective daily nursing assessment ePA-AC (Hunstein et al., Reference Hunstein, Sippel and Rode2012). This construct was added to the DOS and accurately identified 97% of the patients diagnosed with delirium according to DSM-IV-TR.

Measures

DOS scale

For the purposes of this study, the 13-item Delirium Observation Screening (DOS-13) scale was used (Schuurmans et al., Reference Schuurmans, Shortridge-Baggett and Duursma2003). The scale was originally designed to facilitate the early recognition of delirium, according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Items include disturbances of consciousness (1), attention (2–4), thought processes (5 and 6), orientation (7 and 8), memory (9), psychomotor behavior (10, 11, and 13), and affect (12). Each item is rated as normal (0) or abnormal (1). Items were aggregated throughout recordings. Any score ≥3 indicates delirium.

Charlson Comorbidity Index

To assess multimorbidity and frailty, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was applied (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, Pompei and Ales1987). The CCI aggregates multiple medical conditions, including age, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatic disease, peptic ulcer disease, liver disease, diabetes mellitus, hemiplegia or paraplegia, renal disease, malignancy, and AIDS/HIV. The medical conditions are weighted on a scale from 1 to 6 with total scores ranging from 0 to 37. A total comorbidity score can be computed from the weighted conditions. The CCI shows good reliability and is strongly correlated with mortality and progression-free survival (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Mackenzie and Magnuson2016).

Statistical methods

All analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences SPSS 25.0 software (IBM Corp., Released 2017) and R. All tests were two-tailed, and the significance level α was set at <0.05. Descriptive statistics were reported as means/standard deviations or medians, interquartile ranges or as counts and percentages, as appropriate. Dichotomizations were chosen for age (<65 vs. ≥65 years), the CCI (<2 vs. ≥2), frailty (mobility impaired vs. not impaired), and residence status prior to admission (institution vs. home). All continuous data were tested for normality using Shapiro–Wilk's test. Continuous outcomes were compared using Student's t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests for parametric and non-parametric data, respectively, and categorical variables with Pearson's χ2 or Fisher's exact test, where appropriate.

For the purpose of analysis evaluating the predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium, the data were dichotomized according to the presence or absence of delirium. Subsequently, simple logistic regression models were used to determine effect sizes of socio-demographic and medical characteristics, as well as the prevalence rates for delirium among palliative care patients expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). As the last step, multiple logistic regression models were used to determine associations between predisposing and precipitating risk factors and delirium in palliative care patients. Multiple regression models were computed with their respective ORs and CIs, based on the results of the simple logistic regressions models, by entering variables with a p-value <0.15. The model was verified with its Cox–Snell's and Nagelkerke's r 2.

Results

Demographics and medical characteristics

Detailed patient demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The majority of the palliative care patients were cancer patients with predominantly gynecological or lung cancers. In this palliative care patient cohort, the prevalence rate of delirium was 55.9%. Palliative care patients with delirium were primarily males (two-thirds of the sample), who had a twofold increase in risk for delirium. The delirious patients were significantly more commonly admitted as emergencies (OR = 2.14) and less likely to be discharged home (OR = 0.11), and had a hospitalization time twice as long as those who were not delirious. Patients with intracranial neoplasms had a 3.5-fold higher risk of developing delirium. Generally insured patients developed delirium almost twice as often as semi-privately and privately insured patients. Palliative care patients with delirium had twice the care needs and accounted for twice the health care cost per case. Importantly, delirious patients had a substantial increase in their risk of in-hospital mortality (OR = 18.29). Of those who died in the hospital, 92.6% suffered from terminal delirium. The median time to death did not differ significantly between the groups of delirious and non-delirious patients. No group differences were found for age, number of comorbidities, stay prior to admission, type of facility following hospital discharge, or time to death.

Table 2. Socio-demographic, medical, and neurological characteristics of the delirious vs. non-delirious palliative care patients

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; M, mean; SD, standard deviation; Md, median; IQR, interquartile range.

a Mean, standard deviation; median, interquartile range.

Determination of predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in palliative care patients

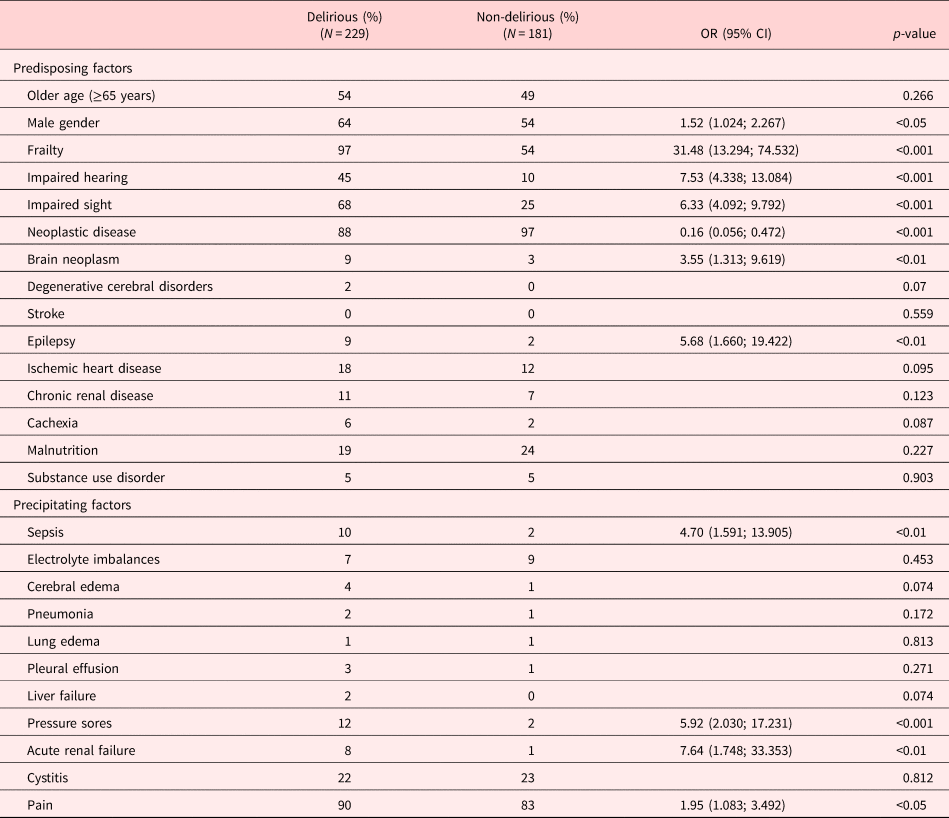

Simple logistic regression identified the following predisposing factors as relevant for delirium: frailty (OR = 31.48), impaired hearing and vision (OR = 7.53 and 6.33, respectively), suffering from epilepsy (OR = 5.68), the presence of brain metastases (OR = 3.55), and male gender (OR = 1.52). No significant group differences were found in terms of older age and the prevalence of degenerative cerebral disorders, stroke, ischemic heart disease, chronic renal failure, cachexia, malnutrition, or substance use disorder.

The most relevant precipitating factors identified by simple logistic regression were acute renal failure (OR = 7.64), pressure sores (OR = 5.92), sepsis (OR = 4.70), and experiencing pain (OR = 1.95). No intergroup differences were found for electrolyte imbalances, cerebral edema, pneumonia, lung edema, pleural effusion, or liver failure. Details on group differences in predisposing and precipitating factors between delirious and non-delirious patients are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Predisposing and precipitating factors in delirious vs. non-delirious palliative care patients

OR, Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval.

Multiple regressions analysis for predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium

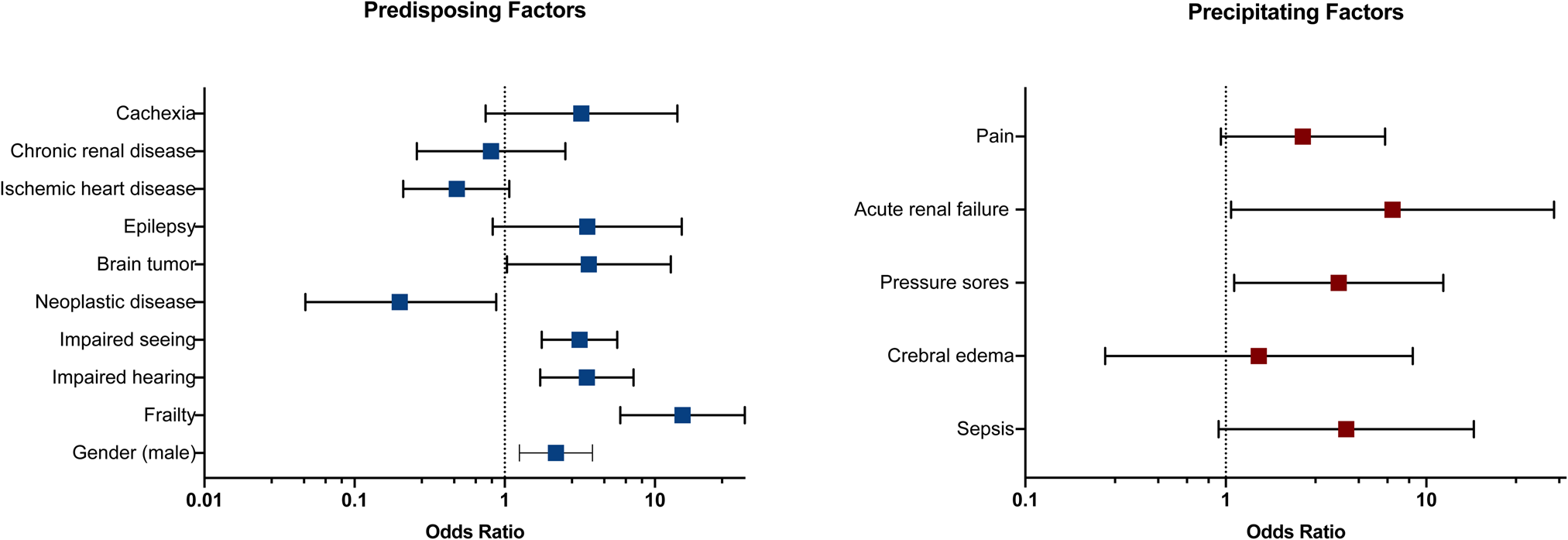

Table 4 summarizes the multiple regression analyses examining the relationship between predisposing and precipitating risk factors and delirium in palliative care patients. On multivariate regression, the most relevant predisposing risk factor was frailty, with a 15-fold increased risk of delirium. Impaired hearing and the presence of brain neoplasms increased the risk for delirium by a factor of four and impaired vision by a factor of three. Male gender increased the risk of delirium by a factor two. Contrarily, the neoplastic disease was not associated with an increased risk for delirium, although most patients had cancer. No significant associations with delirium in palliative care patients were identified for epilepsy, ischemic heart disease, chronic renal disease, or cachexia.

Table 4. Summary of a multiple regression model for the predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in palliative care patients with estimated coefficients (B, SE), 95% CIs, and p-values

Cox–Snell and Nagelkerke r 2 = 0.238 and 0.357. SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval.

The most relevant precipitating factors for developing delirium were acute renal failure, increasing the risk of developing delirium by a factor of seven, and pressure sores, increasing the risk of delirium fourfold. Sepsis, cerebral edema, and pain were not predictive of delirium in palliative care patients. Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium are depicted in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Forest plots of predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium. ORs and 95% CIs are reported for each delirium risk factor. The edges of the polygon represent the 95% CI. The graphical representation in the figure refers to the statistics in Table 4.

Discussion

This prospective observational study sought to identify predisposing and precipitating risk factors for delirium in palliative care patients that can be targeted early and either modified or eliminated. The prevalence of delirium in palliative care patients was 55.9%, which is consistent with other prevalence rates reported in the current literature (Hosie et al., Reference Hosie, Davidson and Agar2013; de la Cruz et al., Reference de la Cruz, Ransing and Yennu2015; Bush et al., Reference Bush, Tierney and Lawlor2017). This finding underscores the need for systematic delirium screening in palliative care patients. The development of delirium is particularly prevalent in patients near the end of life and considered a poor prognostic sign (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Tierney and Lawlor2017). In this study, 93% of patients had terminal delirium in their last days of life. Our results corroborate the previous research, including palliative care patients, for which a delirium rated of up to 88% in the terminal phase of life has been reported (Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Gagnon and Mancini2000). Overall, delirium in palliative care patients was associated with increased healthcare requirements, prolonged hospital stays, increased health care costs, the need for specialized care homes, and increased mortality, reflecting outcomes in the acute hospital setting (Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Schurch and Boettger2018). Contradicting to the current literature, in which age and comorbidities have been claimed as significant risk factors for delirium (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lawlor and Ryan2018), we were unable to identify older age (≥65 years) or comorbidities as contributory. Notably, the palliative care patients had multiple terminal medical conditions more relevant to the outcome than either age or comorbidities. It is reasonable to assume that, in terminally ill patients, factors other than older age have a greater impact on the development of delirium, due to the high degree of systemic inflammation and/or organ dysfunction.

The etiology of the delirium syndrome in terminally ill patients is complex and multidimensional, involving many potentially contributing predisposing and precipitating factors (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lawlor and Ryan2018). Of note, palliative care patients are at particular risk of delirium due to a number of contributing factors in the pathogenesis of delirium, like the advanced disease (e.g., malignancy) itself, the presence of metastases, hematological conditions (e.g., anemia), high-level systemic inflammation, organ dysfunction, infections/sepsis, impaired functional status, poor nutritional status, adverse effects of radiation/chemotherapy, and treatment with certain medications (e.g., opioids, corticosteroids, and benzodiazepines) (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Shin and Bruera2013; Hosker and Bennett, Reference Hosker and Bennett2016; Bush et al., Reference Bush, Tierney and Lawlor2017, Reference Bush, Lawlor and Ryan2018). In the current palliative care literature, there is limited evidence about socio-demographic or disease-related predictive factors for delirium in palliative care patients (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lawlor and Ryan2018). In addition, studies, including palliative care patients, have traditionally focused predominantly on delirium prevalence, delirium management, and outcomes rather than investigating risk factors predicting delirium in this vulnerable population (Maltoni et al., Reference Maltoni, Scarpi and Pittureri2012; de la Cruz et al., Reference de la Cruz, Ransing and Yennu2015; Boettger and Jenewein, Reference Boettger and Jenewein2017; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Frisbee-Hume and Wilson2017; Hosie et al., Reference Hosie, Phillips and Lam2019; Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Rutkowski and MacDonald2019).

Considering these findings, in a second analytical step, we sought to identify differences between delirious and non-delirious palliative care patients including a number of delirium risk factors that have been identified in medically ill patients (Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Schurch and Boettger2018; Zipser et al., Reference Zipser, Deuel and Ernst2019). Contributory predisposing factors for delirium in palliative care patients included male gender, frailty, hearing and visual impairment, and epilepsy, as well as brain metastases. Contributory precipitating factors included sepsis, pressure sores, acute renal failure, and pain. Neoplastic disease by itself was not associated with an increased delirium risk but even with an 80% decrease. It is notable that cancer itself might not be as relevant to delirium as complications caused by the terminal illness.

Lastly, we explored potential predictors of delirium in palliative care patients. On multivariate analysis, the most relevant predisposing risk factors for delirium were male gender, frailty, hearing and visual impairment, and brain neoplasms, while the most important precipitating risk factors were the presence of pressure sores and acute renal failure. There is scant literature that has systematically investigated predisposing and/or precipitating risk factors for delirium in palliative care patients. One study found that delirium was precipitated by opioids and other psychoactive medications, dehydration, hypoxic encephalopathy, metabolic factors, and non-respiratory infection (Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Gagnon and Mancini2000). Another study explored predisposing risk factors for delirium in terminally ill patients and identified hepatic failure, medications, prerenal azotemia, hyperosmolality, hypoxia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, organic damage to the central nervous system, infections, and hypercalcemia as the main contributing predisposing risk factors for delirium (Morita et al., Reference Morita, Tei and Tsunoda2001). In a prospective observational study, including oncological patients with different cancer stages, factors significantly associated with the occurrence of delirium were advanced age, cognitive impairment on admission, hypoalbuminemia, the presence of bone metastases, and the diagnosis of a hematological malignancy (Ljubisavljevic and Kelly, Reference Ljubisavljevic and Kelly2003). These inconsistent findings might be best explained by methodological differences. Furthermore, a number of studies suggest that underlying pathologies of delirium in palliative care patients are usually multifactorial and commonly unspecified (Stiefel et al., Reference Stiefel, Fainsinger and Bruera1992; Bush et al., Reference Bush, Tierney and Lawlor2017; de la Cruz et al., Reference de la Cruz, Yennu and Liu2017; Diwell et al., Reference Diwell, Davis and Vickerstaff2018). Moreover, the identification of risk factors for delirium in palliative care patients may be complicated by high systemic inflammation and iatrogenic conditions. Furthermore, the distinction between predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in palliative care patients can be fairly arbitrary, due to the complex and multifactorial etiology of delirium and considerable multimorbidity in terminally ill patients (Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Gagnon and Mancini2000; Ljubisavljevic and Kelly, Reference Ljubisavljevic and Kelly2003).

A multifactorial model of delirium has been proposed for hospitalized patients age ≥70 years (Inouye et al., Reference Inouye, Westendorp and Saczynski2014), assuming that patients with multiple predisposing conditions for delirium (high baseline vulnerability) seem to be more vulnerable to precipitating factors or noxious insults than patients with only one predisposing factor. Thus, the accumulation and synergy of predisposing and precipitating factors may potentiate the severity of delirium (Laurila et al., Reference Laurila, Laakkonen and Tilvis2008). Correspondingly, in older, frail patients with less advanced disease, relatively little comorbidity is often sufficient to promote delirium, whereas in younger individuals, multiple comorbidities and more severe illness might be necessary (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lawlor and Ryan2018).

Typically, delirium in palliative care patients is an indicator of some acute change in the patient's medical condition (Hosie et al., Reference Hosie, Davidson and Agar2013). In particular, hyperactive delirium — commonly referred to as “terminal agitation” or “terminal restlessness” — can cause high distress among family members (Namba et al., Reference Namba, Morita and Imura2007). Given the substantial burden of delirium for palliative care patients and their caregivers, it is clinically important to prevent, recognize, and manage early the symptoms of delirium and identify contributory causes. One key strategy to prevent delirium is the treatment of potentially reversible predisposing and acute precipitating factors (e.g., providing hearing and vision aids, treating pain, infections and electrolyte abnormalities, reducing polypharmacy, and regulating the sleep–wake cycle) (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lawlor and Ryan2018).

In many acute care hospital settings, delirium is frequently underdiagnosed (Elsayem et al., Reference Elsayem, Bruera and Valentine2016). The early detection of clinical signs of delirium in palliative care patients can be improved by the routine use of screening tools and monitoring by the nursing staff (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lawlor and Ryan2018). In this study, a combined approach using the DOS tool and the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for delirium achieved diagnostic sensitivity of 97%, and thus, proved to be superior to using the DOS instrument alone or the combined DOS/Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) (Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Schurch and Boettger2018). A similar approach has been utilized to diagnose delirium among elderly medical inpatients, in whom applying the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for delirium exhibited high sensitivity and specificity (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Dendukuri and McCusker2003).

Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments are available for delirium management. However, most of these guidelines are based on the knowledge of delirious symptom management in medically ill patients (Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Schurch and Boettger2018) or elderly individuals (Inouye et al., Reference Inouye, Westendorp and Saczynski2014). Although delirium in palliative care patients can potentially be reversed in approximately 50% of cases, the decision to initiate pharmacological treatment depends on the estimated prognosis and objectives of care (e.g., management of delirium to reduce morbidity and improve the quality of life vs. palliative sedation for refractory delirium and expected survival of hours to days) (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Shin and Bruera2013; Bush et al., Reference Bush, Tierney and Lawlor2017). Although eliminating delirium is not always feasible, symptomatic management of potentially reversible causes of delirium, particularly multicomponent non-pharmacological strategies (e.g., training nursing staff and improving the patients' environment) should be provided to all palliative care patients and complemented with pharmacological interventions, where indicated (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lawlor and Ryan2018).

Strengths and limitations

Important strengths of our study include its rigorous methodology, utilization of an innovative delirium-screening approach, combining the DOS score and the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for delirium, and systematic assessment of precipitating and predisposing risk factors for delirium in a select group of palliative care patients known to be extremely vulnerable to delirium. On the other hand, the study had several limitations. First, data collection was limited to a single center, which may limit the generalizability of results. Second, certain uncommon factors for delirium, like endocrine disorders, were not investigated, and brain imaging was not routinely performed. Third, clinical features of delirium were assessed only cross-sectionally. Finally, conducting research in delirious patients at the end of life includes many ethical challenges (e.g., decision-making capacity in delirious patients at the end of life) (Casarett, Reference Casarett2005). In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Article 29, a waiver of consent was granted by the ethics committee because the majority of our studied population was physically and mentally unable to give consent (delirious patients), and the condition (delirium) that causes this inability was a necessary characteristic of our research population (World Medical Association, 2013). This prospective observational study was considered to produce not more than a minimal risk to the study subjects and involved no procedure for which written informed consent was required. Proxy assessments were conducted by well-trained and experienced nurses, and medical information was retrieved through medical record retrieval. Finally, this study sought to improve the quality of delirium assessments in an acute hospital setting by proposing a novel delirium-screening construct, an effort that should be of benefit for future patients.

Conclusions

Delirium is a prevalent complication in palliative care patients, especially in the end-of-life context. Combining the DOS instrument and the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for delirium appeared to screen for delirium with high sensitivity and specificity. Our study also identified several predisposing and precipitating risk factors for delirium in palliative care patients, some of which can be targeted early and either modified or eliminated to reduce symptom burden and improve clinical outcomes. At present, limited evidence exists with respect to predisposing and precipitating risk factors for delirium in palliative care patients. Continued research is warranted to strengthen the reliability of our findings and to better understand risk factors for delirium and their potential reversibility with the ultimate aim of improving the management of delirium in palliative care patients (Hui, Reference Hui2019).

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.