Introduction

The modern medication treatment of schizophrenia appeared in the 1950s and had a profound impact on the lives of millions of patients and their families worldwide. The ability of these medications to both alleviate the acute episodes but also to prevent relapses made them a class of successful treatment options in the medical landscape.Reference Kane and Correll 1

In the early 1960s, the antipsychotic treatment led Arvid Carlsson (1923-2018), who later received the Nobel Prize in 2000, to identify dopamine as a neurotransmitter, which in turn led to the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. 2 –Reference Carlsson 5 In the 1990s, the second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) or atypical antipsychotics appeared. Their main advantage was that they had a significantly lower frequency of extrapyramidal adverse effects and related conditions (eg, tardive dyskinesia or neuroleptic malignant syndrome). 6 –Reference Carbon, Hsieh, Kane and Correll 10

Thus, treatment with antipsychotics is currently considered to be the basis of the treatment of schizophrenia, and therapeutic approaches without the administration of these agents are definitely considered to be inappropriate.Reference Kahn, Sommer and Murray 11 , Reference Correll, Rubio and Kane 12 Both for the acute and the maintenance phase, long-term antipsychotic treatment over years is accepted as the standard for patients with schizophrenia. While criticism on the methodology of research is always present and leads to improvement of the methodology itself,Reference Leucht, Heres, Hamann and Kane 13 recently it stopped being merely such a criticism. The core belief on the usefulness of antipsychotics has been challenged, and a series of publications argued that long-term antipsychotic treatment could not only be useless but also harmful, because it might worsen the long-term outcome of patients. 14 –Reference Whitaker 17

In this frame, a number of issues have been raised, including the return of the dopamine sensitization hypothesis and tardive psychosis as well as the possibility antipsychotics to cause brain atrophy. These arguments emerged after the publication of several more recent studies, which revived an old debate and suggested a more favorable outcome for those patients who discontinued antipsychotic medication soon after the resolution of the acute phase. 18 –Reference Calton, Ferriter, Huband and Spandler 20 Additionally, many authors insist on the possible harmful effects of long-term antipsychotic treatment.Reference Moncrieff 16 , Reference Moncrieff 21 , Reference Murray, Quattrone and Natesan 22

It is a fact that the literature lacks properly designed and conducted studies concerning the long-term effects of antipsychotics. Long-term studies of more than 2 to 3 years are naturalistic, and our knowledge beyond 3 years follow-up is limited.Reference Leucht, Tardy, Komossa, Heres, Kissling and Davis 23 However, the concern is so big that the possible harmful effect of antipsychotics on the brain has been included as a warning in the 2014 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines (CG178), albeit being mostly based on weak evidence.

Aim of the Paper

The aim of the current paper was to review the relevant literature and arrive at a consensus paper concerning the use and usefulness of antipsychotics as well as the limitations and potential dangers of their use in the treatment of schizophrenia. This document could serve as a guide for clinicians and also for patients and their families in the design of the long-term treatment approach as well as in the making of informed decisions.

Methods

The method followed for the writing of the current paper was

-

a. An analysis of arguments already published in the literature;

-

b. A selective review of the literature also in parallel with the analysis of these arguments. This literature review was not exhaustive; however, it was targeted at two main objectives:

-

• To establish a list of issues that have been raised during the last few years in the frame of the debate on antipsychotic use in people with schizophrenia and

-

• To find pro and con arguments to support or refute these issues.

The authors kept an open mind concerning what the actual conclusions from this endeavor could be and tried to cope with the literature in an as free of bias way as possible. The pro and con arguments had been processed according to the rules of evidence-based medicine.

Applying the methodology mentioned above, this report sought to address 10 clinically research questions detailed below.

Results

Question 1: Are antipsychotics efficacious and sufficiently safe during the acute psychotic phase?

There is a wide agreement on the efficacy of antipsychotics during the acute phase, and this is based on an abundance of hard data and among others a bulk of placebo-controlled studies, accompanied by a series of reliable meta-analyses. 24 –Reference Haddad and Correll 28 However, the chance of achieving a treatment response to antipsychotics is greater in first-episode patientsReference Leucht, Leucht and Huhn 8 , Reference Zhu, Krause and Huhn 29 , Reference Samara, Nikolakopoulou, Salanti and Leucht 30 than in multi-episode patients. The favorable efficacy of antipsychotics extends also into the early maintenance phase and up to 3 years after the acute episode with numbers-needed-to-treat vs placebo for relapse prevention being as low as 3.Reference Leucht, Tardy, Komossa, Heres, Kissling and Davis 23 , Reference Leucht, Hierl, Kissling, Dold and Davis 31 , Reference Kishimoto, Hagi, Nitta, Kane and Correll 32

The data on antipsychotic efficacy are strong concerning total and positive symptoms, but equivocal concerning primary negative symptoms and neurocognitive deficits, 33 –Reference Nielsen, Levander, Kjaersdam Telleus, Jensen, Ostergaard Christensen and Leucht 36 and this is particularly problematic since the progression of the disorder is characterized by the deterioration in these two particular domains of the clinical picture.

There are two main reservations against the acute use of antipsychotics: (1) that adverse effects of antipsychotics are too severe/that they are not safe and (2) that some patients might not necessarily need such treatment.Reference Moncrieff 21

It is clear that the acute treatment with antipsychotics can have a host of adverse effects, including neuromotor, endocrine, cardiovascular, and so on. 37 –Reference Solmi, Murru and Pacchiarotti 40 The same is true for longer term adverse effects, including diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and tardive dyskinesia.Reference Carbon, Kane, Leucht and Correll 9 , Reference Carbon, Hsieh, Kane and Correll 10 , 41 –Reference Vancampfort, Stubbs and Mitchell 43 It remains unclear, however, whether antipsychotics really increase the risk for cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac deathReference Ray, Chung, Murray, Hall and Stein 44 or whether the increased mortality is due to increased medical morbidity 45 –Reference Stubbs, Koyanagi and Veronese 49 related to poor healthy lifestyleReference Firth, Siddiqi and Koyanagi 46 , Reference Stubbs, Vancampfort and Hallgren 50 and, possibly, underlying genetic/illness-related risk,Reference Firth, Siddiqi and Koyanagi 46 as well as underdiagnosis and undertreatment of cardiovascular risk factorsReference Firth, Siddiqi and Koyanagi 46 (complicating the propensity score adjustment vs control groups). Moreover, increased risk of serious somatic adverse events and of mortality associated with antipsychotics is mostly driven by elderly patients not diagnosed with schizophreniaReference Schneider-Thoma, Efthimiou and Bighelli 39 , Reference Papola, Ostuzzi and Gastaldon 51 , Reference Yang, Hao and Tian 52 who may also be treated with other psychotropic medications.

Despite adverse effects of antipsychotics, it is clear that only subgroups of patients have adverse effects both acutely and long-term, while the “adverse effect” of an untreated schizophrenia illness pertains to all patients with this diagnosis, creating an overall positive risk–benefit ratio. This beneficial overall risk–benefit assessment is supported long-term by decreased overall mortality and, even, decreased cardiovascular mortality in nationwide samples of patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics vs those not treated with antipsychotics. 53 –Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan 57

The second reservation, that is, that some patients may not need antipsychotic treatment, as they may stabilize even without antipsychotics, or not have any further psychotic episodes, is covered when addressing question 5.

Question 2: Should antipsychotics be used in first-episode patients?

There are a number of randomized controlled trials as well as meta-analysesReference Haddad and Correll 28 , Reference Zhu, Krause and Huhn 29 , Reference Zhang, Gallego, Robinson, Malhotra, Kane and Correll 58 supporting the efficacy of antipsychotics in first-episode patients. In fact, the chance of achieving a treatment response to antipsychotics defined as at least minimal or defined as much/very much improvement is greater in first-episode patients, that is, 81% and 52% respectivelyReference Zhu, Krause and Huhn 29 than in multi-episode patients, that is, 51% and 23% respectively.Reference Leucht, Leucht and Huhn 8 , Reference Samara, Nikolakopoulou, Salanti and Leucht 30 However, there exists a subgroup of first-episode patients who have primary treatment resistance to currently available antipsychotics, with a frequency possibly of up to 25%.Reference Lally, Ajnakina and Di Forti 59 , Reference Kane, Agid and Baldwin 60 Despite the overall positive treatment effects in first-episode patients, currently it is unclear what proportion of individual patients experiencing a first episode of non-affective psychosis will remit without medication, who they may be, and how long the remission will last.Reference Bola, Lehtinen, Aaltonen, Rakkolainen, Syvalahti and Lehtinen 61 , Reference Huber, Gross, Schuttler and Linz 62 Additionally, after taking into consideration the high relapse rate and related biopsychosocial consequences in first-episode patients,Reference Correll, Rubio and Kane 12 , 63 –Reference Zipursky, Menezes and Streiner 66 the use of antipsychotic treatment in this group of patients seems necessary.

There is significant discussion recently concerning high-risk individuals and treatment options, especially antipsychotics, to prevent them from developing psychosis. The issue is far from resolved, partially because there are huge methodological problems; it seems most at–high risk individuals never progress to develop psychosis.Reference Addington, Cornblatt and Cadenhead 67 Those who do eventually develop psychosis seem to manifest neurocognitive deficits long before their first episode, and medication is not efficacious against these symptoms.Reference Rabinowitz, Reichenberg, Weiser, Mark, Kaplan and Davidson 68 , Reference Reichenberg, Weiser and Rapp 69

The literature provides with some negative results concerning the efficacy of antipsychotic medication in the prevention of the first psychotic episode in high-risk persons 70-72 but also encouraging results do exist. 73-75 However, the quality of data is problematic and precludes definite conclusions.Reference Bosnjak Kuharic, Kekin, Hew, Rojnic Kuzman and Puljak 71

Question 3: Is there an antipsychotic discontinuation/withdrawal effect? What about the dopamine super-sensitivity hypothesis?

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the hyperdopaminergic theory of schizophrenia was developed and it was based on the empirical discovery of antipsychotics and the theory that they produce their therapeutic effect by blocking post-synaptic D2 dopamine receptors. 76 –Reference Carlsson, Waters, Holm-Waters, Tedroff, Nilsson and Carlsson 78 Subsequently, a refined dopamine hypothesis was developed in the 1990s suggesting a subcortical hyperdopaminergic activity, being secondary to cortical hypodopaminergic activity, in particular in the frontal regions.Reference Davis, Kahn, Ko and Davidson 76 , Reference Grace 79

It has been shown that there is no linear relationship between the D2 occupancy, clinical response, and side effects. Response appears with occupancy above 50% and extrapyramidal side effects when occupancy reaches 75% or more. 80 –Reference Nordstrom, Farde and Wiesel 82 However, this idea has been challenged by the European First Episode Schizophrenia Trial (EUFEST) study which showed that with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) extrapyramidal adverse events might appear even at lower occupancy than the therapeutic threshold.Reference Boter, Peuskens and Libiger 83

Overall, the development of postsynaptic dopamine receptors supersensitivity has been documented in animals after repeated exposure to antipsychotics. 84-88 This led to concerns about possible long-term harmful effects in treated patients. A number of early naturalistic studies reported a favorable outcome and fewer relapses in patients with schizophrenia in direct negative correlation with the dosage of antipsychotics they were receiving. Furthermore, medication-free patients at endpoint seemed to have an even better outcome. 89-92 Although these were naturalistic studies and the outcome could well have been the result of the design rather than the intervention, with less severely ill or non-schizophrenia patients being off antipsychotics, the term “supersensitivity psychosis” was quickly coined to denote both the need for increasing dosages in order to maintain the therapeutic effect (tachyphylaxis) and the emergence of rebound psychosis after discontinuation of medication. 93 –Reference Chouinard, Jones and Annable 95 Supersensitivity psychosis predicts that relapse would be abrupt, and relapses will accumulate during the first couple of months after treatment discontinuation.

However, both after antipsychotic discontinuationReference Gitlin, Nuechterlein and Subotnik 96 and on continued antipsychotic treatment,Reference Takeuchi, Kantor, Sanches, Fervaha, Agid and Remington 97 gradual worsening of symptoms and slowly increasing relapse rated were observed, rather than an early peak of relapses, as would be expected with “dopamine supersensitivity psychosis.”

The first meta-analysis to tackle this issue reported that there was no significant overall difference in the resulting survival functions for those patients who discontinued treatment abruptly vs gradually (N = 1006 and N = 204, respectively; P > .10).Reference Viguera, Baldessarini, Hegarty, van Kammen and Tohen 98

A more recent and more technically advanced meta-analysis also reported no difference between abrupt vs gradual discontinuation of either FGA or SGA medication.Reference Leucht, Tardy and Komossa 99 A recent analysis of registry data from Finland did not support the supersensitivity psychosis theory either.Reference Tiihonen, Tanskanen and Taipale 100 Moreover, two recent studies examining breakthrough psychosis during assured antipsychotic treatment with long-acting injectable antipsychotics were unable to find an association with either cumulative antipsychotic exposureReference Rubio, Taipale, Correll, Tanskanen, Kane and Tiihonen 101 or increased antipsychotic doses.Reference Emsley, Asmal, Rubio, Correll and Kane 102

Overall, there seems to be some sensitization of dopamine receptors, at least in some patients who may also be sensitive to developing tardive dyskinesia and not respond as well to currently available antipsychotic medications, but this upregulation does not seem to cause a rebound psychotic exacerbation if antipsychotics are stopped either abruptly or gradually and does not seem to contribute to a worse global outcome in patients with schizophrenia, whose outcome is worst when not receiving antipsychotics. 53-55 , Reference Tiihonen, Tanskanen and Taipale 100

A special case of withdrawal is clozapine withdrawal syndrome, which is solidly proven concerning a variety of adverse events.Reference Chiappini, Schifano, Corkery and Guirguis 103 It has been reported that when discontinuation is abrupt, it could involve rebound psychosis,Reference Bastiampillai, Juneja and Nance 104 delirium,Reference Stanilla, de Leon and Simpson 105 serotonin syndrome,Reference Stevenson, Schembri, Green and Burns 106 catatonia, 107-109 extrapyramidal adverse events, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. 110 –Reference Sarma, Chetia, Raha and Agarwal 114 While the adverse events could be explained in terms of the pharmacodynamic profile of the substance, the rebound psychosis is far from proven since the hypothesis is based on a few case-reports only.

Question 4: Does initial treatment with antipsychotics worsen the long-term outcome?

The question whether initial treatment with antipsychotics might worsen the long-term outcome emerged soon after their discovery and their wide application in the treatment of psychosisReference Carpenter, McGlashan and Strauss 115 was recently supported by a narrative review.Reference Moncrieff 116

Nine relevant publications from the era when maintenance treatment was not utilized were identified in a recent paperReference Goff, Falkai and Fleischhacker 117 and come from three systematic reviews. 118-120 These papers followed first-episode psychotic patients long-term after their allocation during the acute episode to antipsychotics vs no pharmacotherapy. One of them was not published in a peer-reviewed journal. Their characteristics are shown in Table 1. These papers do not suggest a negative impact of initial treatment; on the contrary, they support a better outcome of patients on antipsychotic treatment.

Table 1. Studies on the long term effect of initial treatment during the acute phase

Abbreviations: HI, historical data; LOCF, last observation carried forward; MI, mirror image; NR, not reported; NS, not significant; PLC, placebo; PR, prospective design.

a Calculated by the authors.

b 42.9% males in the medication group.

c Range.

d Concern the original sample before removal of dropouts.

As mentioned above, historical data from the era before the introduction of antipsychotics suggest that up to 30% of patients experiencing their first psychotic episode will recover spontaneously with remission being sustained in about 15% of them. The development of antipsychotics drastically improved the overall outcome by increasing remission rates twofold, but the effect on full recovery is less clear. 127 –Reference Jaaskelainen, Juola and Hirvonen 129 Statistics from Europe and North America show that antipsychotic treatment led to the dramatic decrease of asylum populations, but had a less impressive effect on the restoration of function. Similar results were produced by more recent studies from Ethiopia,Reference Alem, Kebede and Fekadu 130 Indonesia,Reference Kurihara, Kato, Reverger, Tirta and Kashima 131 and China.Reference Ran, Weng and Chan 132 All these studies reported that overtime the condition of untreated patients worsens more than in treated patients. A confounding variable could be that untreated patients today constitute the more severely ill and uncooperative subgroup of patients.Reference Padmavathi, Rajkumar and Srinivasan 133 On the contrary, increased relapses, hospitalizations, and even mortality have been observed in untreated patients in meta-analyses and in generalizable nationwide samples. 53 –Reference Tiihonen, Mittendorfer-Rutz, Torniainen, Alexanderson and Tanskanen 55 , Reference Zipursky, Menezes and Streiner 66 , Reference Tiihonen, Tanskanen and Taipale 100

Taken all the above studies together, the data do not seem to suggest a deleterious effect of initial antipsychotic treatment; on the contrary there are at least some data suggesting a long-term beneficial effect and increased relapses, hospitalizations and even mortality in untreated patients. The studies reporting superiority of no treatment rely on placebo samples super-selected for benign outcome.

Question 5: Does maintenance treatment with antipsychotics worsen the long-term outcome?

Τhe efficacy of maintenance treatment up to 1 year after the acute episode was confirmed by a meta-analysis of 65 trials.Reference Leucht, Tardy, Komossa, Heres, Kissling and Davis 23 , Reference Leucht, Tardy and Komossa 99 Overall, it was reported that after 1-year follow-up, antipsychotic maintenance treatment was superior to placebo in terms of relapse rates (27% vs 64%) and rehospitalization (10% vs 26%). Furthermore, antipsychotic maintenance treatment was associated with lower likelihood of aggressive and violent behavior (2% vs 12%) and better quality of life. Total dropouts were fewer in the medication than placebo withdrawal arms (30% vs 54%). The beneficial effect of medication was unrelated to illness duration, previous discontinuations of medication, and duration of previous periods of stability, while FGAs and SGAs were equally efficacious. There was no difference between the active drug and the placebo in terms of employment, deaths, or dropout because of adverse events, although patients in the medication arm manifested significantly more extrapyramidal adverse events (16% vs 9%), sedation (13% vs 9%), and weight gain (10% vs 6%). The beneficial effect was similar in first-episode patients vs older/multi-episode patients.

The next milestone is treatment outcome at 3 years. The usefulness of maintenance treatment up until this period is again solidly established, although on the basis of far fewer data. The most recent study was a randomized trial in 128 first-episode patients who were stabilized on antipsychotics for 6 months. They were then randomized, to either a “drug discontinuation/drug reduction” group or a “standard drug maintenance” group. This was the first randomized study on the topic, but although the sample was drawn from an epidemiological cohort, only 50% of the first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients agreed to participate in the study. In only approximately 20% of patients, complete discontinuation was possible. The results suggested that discontinuing (or aggressively lowering) antipsychotic treatment during the maintenance phase led to a higher relapse rate (43% vs 21%) during the first 18 months.Reference Wunderink, Nienhuis, Sytema, Slooff, Knegtering and Wiersma 134 These conclusions have been confirmed by later studies.Reference Gaebel, Riesbeck and Wolwer 135 , Reference Gaebel, Riesbeck and Wolwer 136

The next question is whether further maintenance treatment could be beneficial or whether the risk of relapse tends to attenuate after a certain period of time. The data are insufficient but still suggest that the relapse rate was not different in patients who had been stable for up to 3 to 6 years. In other words, no matter how long the patient is doing well, the risk for relapse still exists and is uncovered after medication discontinuation. Thus, continuous treatment is necessary irrespective of current clinical status.Reference Cheung 137 , Reference Sampath, Shah, Krska and Soni 138

The evidence for the effect of maintenance treatment with antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia from observational and naturalistic studies is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Studies on maintenance treatment beyond 3 years duration with antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia

Abbreviations: FEP, first-episode psychosis; IPSS, International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia; WHO, World Health Organization.

a For several studies, it is only indicative or approximate calculations by the authors.

Overall, small-scale observational studies suggest that patients currently off antipsychotics manifest a more favorable outcome.Reference Wunderink, Nieboer, Wiersma, Sytema and Nienhuis 18 , 141 –Reference Harrow, Jobe, Faull and Yang 144 , Reference Moilanen, Haapea and Miettunen 148 The results from intermediate size studies are mixed.Reference Hui, Honer and Lee 145 , Reference Wils, Gotfredsen and Hjorthoj 153

One particular study worth discussing is that of Wunderink et alReference Wunderink, Nieboer, Wiersma, Sytema and Nienhuis 18 since it is the one considered to be strongly suggestive against the long-term use of antipsychotics that has stimulated the conduct of ongoing antipsychotic discontinuation and intermittent treatment studies that have produced significantly worse outcomes than maintenance studies.Reference Sampson, Mansour, Maayan, Soares-Weiser and Adams 154 After their initial 3-year follow-up study,Reference Wunderink, Nienhuis, Sytema, Slooff, Knegtering and Wiersma 134 which concerned the randomization of patients to a dose-reduction (DR) or dose maintenance (MT) groups, the authors went on to naturalistically follow-up patients for an additional 5 years. At the end of that period, they reported (in 103 patients of the original 128) that there was no difference between the original group that was initially randomized to receive regular antipsychotic dose maintenance treatment and the group initially randomized to reducing the antipsychotic dose with an attempt to potentially discontinue the antipsychotic regarding relapse (68.6% vs 61.5%) or symptomatic remission (66.7% vs 69.2%). Additionally, there were no differences in number of relapses (1.13 ± 1.22 vs 1.35 ± 1.51), but the number of relapses was very low for the period of 7 years and thus it is suggestive of a very benign study sample, likely due to the fact that only 50% of the epidemiological sample had agreed to be randomized originally and, importantly, only 43.7% of the sample followed at 7 years had been diagnosed with schizophrenia 7 years ago. The reported greater likelihood of functional remission (46.2% vs 19.6%) and recovery (40.4% vs 17.6%; P = .004) in the antipsychotic DR/discontinuation group, but, again, the rate is unexpectedly high and suggestive of a very benign study sample. While there was a significantly lower antipsychotic dosage in the DR group (2.2 ± 2.27 vs 3.6 ± 4.01 mg haloperidol; P = .03), there was no difference in the months with zero intake of antipsychotics (6.38 ± 10.28 vs 4.35 ± 8.49; <7% of total time). The relapse rate was equal after year 3, being >60% and at the end of 7 years. This study manifests a number of problems. The major misleading feature of the study is that it discusses the results in terms of “medication discontinuation,” while this is not the case. The original definition of the group was “dose reduction” (DR), and this indeed resulted in a significantly lower antipsychotic dosage in the DR group even at 7 years follow-up, but only 11 patients (11%) of the entire sample (DR: N = 8; MT: N = 3) were off antipsychotics for at least the last 2 years. The second problem is that only 43.7% of the patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, whereas the remainder had a non-schizophrenia and more benign form of psychosis, and that outcomes were assessed only via the phone and that diagnoses at endpoint were not confirmed. Another issue is that while they started as a randomized sample, this stopped at month 18 and from which point on the study sample followed a fully naturalistic course concerning treatment. Possible confounding factors could be that more patients with schizophrenia were randomly assigned to MT (51.0%) in comparison to DR group (36.5%), numerically more patients in the DR group were working at baseline (54% vs 36%; P = 0.07). Interestingly, the results do suggest a significant correlation between duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and worse outcome (odds ratio [OR] = 0.62; P = 0.02).Reference Wunderink, Nieboer, Wiersma, Sytema and Nienhuis 18 These factors make it entirely unclear to what degree these data can be applied to the long-term outcome of patients with a confirmed schizophrenia diagnosis, and they do not sufficiently contribute to the question whether and in whom antipsychotics can be discontinued safely.

On the contrary, all large studies including epidemiological as well as nationwide registry-based data favor continuous maintenance treatment.Reference Torniainen, Mittendorfer-Rutz and Tanskanen 56 , Reference Tiihonen, Tanskanen and Taipale 100 , Reference Ran, Weng and Chan 132 , Reference Tiihonen, Wahlbeck and Lonnqvist 151 , Reference Tiihonen, Lonnqvist and Wahlbeck 152 The harder the data, the more they favor continuous maintenance treatment, which strongly suggests the presence of significant confounding factors for the conclusions in observational and naturalistic studies, especially if no advanced propensity score matching or within subjects designs are employed to mitigate against relevant selection biases.

In the literature, there are several impressive studies with strange results. One such example is the World Health Organization International Study of Schizophrenia, which among other things reported that schizophrenia had a more favorable outcome in developing countries.Reference Harrison, Hopper and Craig 140 , Reference Leff, Sartorius, Jablensky, Korten and Ernberg 147 , 155 This would indirectly imply that treatment-naïve patients might do better long-term, but subsequent publications rejected this more favorable outcome. 156 –Reference Padma 159 Maybe, the most important finding of that study was that the time spent in episodes of psychosis during the early illness stages is a strong determinant of later adverse outcomes, thus supporting the long-term beneficial effect of early and sufficient medication treatment.Reference Harrison, Hopper and Craig 140

A number of projects, including the AESOP-10,Reference Morgan, Lappin and Heslin 149 , Reference Revier, Reininghaus and Dutta 150 the Suffolk County Mental Health Project,Reference Kotov, Fochtmann and Li 146 and the Chicago Follow-up studies, 141 –Reference Harrow, Jobe, Faull and Yang 144 failed to provide data and conclusions free of the well-known biases of naturalistic and observational studies. One recent, large registry study with up to 20-year follow-up (median = 14 years) showed a significantly lower mortality rate for patients during any vs no antipsychotic treatment (25.7% vs 46.2%).Reference Taipale, Tanskanen, Mehtala, Vattulainen, Correll and Tiihonen 54

The conclusions from the review of the above studies by several authors are conflicting.Reference Correll, Rubio and Kane 12 , Reference Moncrieff 16 , Reference Goff, Falkai and Fleischhacker 117 , Reference Harrow and Jobe 160 Taken together, the above simply confirm the known properties of observational and naturalistic design, which is characterized by a number of inherent biases and a number of confounding factors since no adequate control group is included,Reference De Hert, Correll and Cohen 161 while the direction of the cause-and-effect relationship is impossible to determine. A minority of patients probably around 10% to 15% could do well with very low dosages and possibly intermittent administration of antipsychotic treatment with prolonged periods without any antipsychotic medication; however, it is yet impossible to identify a priori these patients.Reference Correll, Rubio and Kane 12 The argument that a relevant minority of patients with a confirmed diagnosis of schizophrenia will do well long-term without any medication everReference Steingard 162 , Reference Whitaker 163 is not supported by the data.

Inconsistencies in the data and interpretation most likely depend a lot on the selection of patients with different psychotic disorders, which must be taken into consideration when attempting to make judgments about risk and benefits of antipsychotic treatment in patients with schizophrenia.

Finally, as mentioned above, long-term adverse effects of antipsychotics clearly exist,Reference Carbon, Kane, Leucht and Correll 9 , Reference Carbon, Hsieh, Kane and Correll 10 , Reference Kishimoto, Hagi, Nitta, Kane and Correll 32 , 41 –Reference Vancampfort, Stubbs and Mitchell 43 including diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and tardive dyskinesia. Moreover, patients with schizophrenia have a 1.5 to >2-fold increased risk of mortality compared to the general population.Reference Correll, Solmi and Veronese 45 , Reference Firth, Siddiqi and Koyanagi 46 However, the mortality risk is significantly higher/elevated in patients not receiving antipsychotic treatment compared to those undergoing long-term antipsychotic treatment. 53 –Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan 57 Importantly, both for hospitalization risk and all-cause mortality, there does not appear to be a safe time when to discontinue antipsychotic treatment after a first episode of schizophrenia.Reference Tiihonen, Tanskanen and Taipale 100

This, in conclusion, the currently available data support the positive risk–benefit ratio of long-term antipsychotic treatment in people with schizophrenia.

Question 6: Does the relapse rate level off after 3 years irrespective of treatment?

This suggestion is based mainly on the results of the second naturalistic phase of the Wunderink et al study.Reference Wunderink, Nieboer, Wiersma, Sytema and Nienhuis 18 As discussed previously, that study sample was unusually benign in terms of diagnosis and illness course, with no more than half of its study sample suffering from schizophrenia, and it is an antipsychotic dose reduction rather than a discontinuation study with the two arms being similar in terms of treatment after a certain period of time and at endpoint. This is expected because of the naturalistic design since after some time, the maintenance treatment was adjusted to the individual needs of each patient, independent of initial randomization up to 7 years prior to endpoint, resulting in the flattening of differences between the two relatively benign outcome groups.

A number of other studies, including a meta-analysisReference Menezes, Arenovich and Zipursky 164 and primary data studies,Reference Kotov, Fochtmann and Li 146 , Reference Morgan, Lappin and Heslin 149 , Reference Austin, Mors and Budtz-Jorgensen 165 also utilized mixed samples and therefore unfortunately add little to the effort to answer the question on the longitudinal course of relapse rates in people with diagnosed schizophrenia (as opposed to a mix of psychotic conditions). The overall picture that these studies provide is that “schizophrenia” (although defined in an overinclusive way) is characterized by a chronic and deteriorating course. It is important to note that a chronic illness course and poor functionality may occur despite less frequent exacerbations and episodicity of the illness.

In summary, the authors are not aware of high-quality data to support the claim that the relapse rates level off after 3 years, but clearly more research is needed on this topic.

Question 7: Is long DUP a negative predictor for the outcome?

Although it is common belief that a long DUP could constitute a negative predictor, this belief has been challenged recently especially in the frame of care of psychotic patients without the use of medication.

In general, mostly older meta-analyses 166 –Reference Perkins, Gu, Boteva and Lieberman 168 and individual studies converge on a consensus that longer DUP is modestly related to positive and negative symptoms as well as several indices reflecting worse functioning and poor remission both at baseline and after treatment and follow-up but not with neurocognitive function (Table 3). Only 2 out of the 14 studies of Table 3 suggest no negative effect for DUP.Reference Wunderink, Nieboer, Wiersma, Sytema and Nienhuis 18 , 169 –Reference Sullivan, Carroll and Peters 181It is interesting that even the second phase study by Wunderink et al, which is the only study that utilized a randomized study sample at baseline, reported that shorter DUP was in essence the only variable that was significantly related to symptomatic remission (OR = 0.62; P = .02).Reference Wunderink, Nieboer, Wiersma, Sytema and Nienhuis 18

Table 3. Studies on the effect of DUP on the long term outcome in patients with schizophrenia

Abbreviations: FEP, first-episode psychosis; DUP, duration of untreated psychosis; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NR, not reported.

a For several studies, it is only indicative or approximate calculations by the authors.

Criticism concerning three specific papersReference Penttila, Jaaskelainen, Hirvonen, Isohanni and Miettunen 167 , Reference Perkins, Gu, Boteva and Lieberman 168 , Reference Melle, Larsen and Haahr 177 argues that treatment is not synonymous with antipsychotic treatment, and therefore the only point that the literature suggests is that if patients are identified early, they tend to be less impaired and they remain so over time, but this does not necessarily mean that an earlier intervention of any kind has much effect.Reference Steingard 162 However, this shifts the attention from the importance of DUP to the efficacy of acute and long-term treatment, which are quite different issues. Criticism for the conclusions of the Norwegian Early Detection (TIPS) studyReference Hegelstad, Larsen and Auestad 175 , Reference Melle, Larsen and Haahr 177 argues that results are mediated by the patients’ premorbid status.Reference Moncrieff 21 An additional concern was expressed on the unexpectedly high death rate in this young patient sample,Reference Gøtzsche 182 but this was related to longer DUP and substance abuse, although there was also an unusually high 1% death rate because of cardiovascular problems.Reference Melle, Olav Johannesen and Haahr 183

There are a number of meta-analyses on the topic. The first of them identified 43 publications and reported that shorter DUP was associated with negative symptoms alone at treatment initiation and with greater response to treatment, global psychopathology, positive and negative symptoms, and functional outcomes. There was no correlation with neurocognitive deficits, and the findings remained significant after controlling for variables known to influence prognosis.Reference Perkins, Gu, Boteva and Lieberman 168

The second included 26 studies involving 4490 patients; it showed a significant association between longer DUP and several poorer outcomes at 6 and 12 months (including total symptoms, depression/anxiety, negative symptoms, overall functioning, positive symptoms, and social functioning). Additionally, patients with a long DUP were significantly less likely to achieve remission and controlling for premorbid adjustment did not influence the findings.Reference Marshall, Lewis, Lockwood, Drake, Jones and Croudace 166

Another meta-analysis of 33 studies reported that long DUP was associated with more severe outcome in general symptomatology, positive and negative symptoms, social functioning, and remission but not in hospitalization, quality of life, or employment. Longer follow-up resulted in stronger associations between DUP and negative symptoms (P = .035), hospital treatment (P = .046), and global outcome (P = .035). Higher national income level resulted in a stronger correlation between DUP and general symptomatic outcome (P = .008) and positive symptoms (P = .016).Reference Penttila, Jaaskelainen, Hirvonen, Isohanni and Miettunen 167

A more recent meta-analysis of 27 studies and 3127 patients with FEP that focused exclusively on neurocognition reported that, overall, DUP and neurocognitive abilities were not significantly related, with the exception of evidence for a weak relationship with planning/problem-solving ability which will probably not survive correction for multiple comparisons.Reference Bora, Yalincetin, Akdede and Alptekin 184 The last meta-analysis focused on the possible relationship of DUP and brain structure. It identified 48 studies and reported that only a small minority of them reported a statistically significant finding.Reference Anderson, Rodrigues and Mann 185

It is interesting to mention a recent study which suggests that the frequently reported association between DUP and psychosocial function may be an artifact of early detection, creating the illusion that early intervention is associated with improved outcomes. In other words, according to these authors, DUP may be better understood as an indicator of illness stage than a predictor of course.Reference Jonas, Fochtmann and Perlman 186

In conclusion, the literature suggests that longer DUP is modestly related to positive and negative symptoms as well as several indices reflecting poor functioning and reduced proportion of remission both at baseline and after treatment and follow-up, but the effect on neurocognitive functioning is equivocal. The data on the possible neurotoxic effect are less robust, and they seem to depend on the imaging methodology and probably concern specific brain regions rather than the whole brain, but more data are needed. One reason why the literature fails to define the role of DUP is that the progression of schizophrenia is slow and it takes many years for worsening to appear.Reference Fountoulakis, Dragioti and Theofilidis 187

Question 8: Are relapses detrimental to illness trajectories and outcomes?

Overall, the classical concept of schizophrenia is that of a chronic illness with frequent relapses leading to significant disability.Reference Robinson, Woerner and Alvir 188 Relapses are considered to exert a neurotoxic effect with patients never returning to their previous functioning status.Reference Wyatt 120 , 189-191

There is no reliable way to predict which patients will relapse with the use of either clinical or neurobiological indicesReference Emsley, Oosthuizen, Koen, Niehaus and Martinez 192 and, as mentioned above, longer duration of treatment does not reduce the risk of relapse upon antipsychotic discontinuation.Reference Emsley, Oosthuizen, Koen, Niehaus and Martinez 192

The suggestion that the accumulation of relapses leads to disease progression is supported by the following findings:

-

• First episodes respond better to treatment and have better prognosis in comparison to later episodes.Reference Lieberman, Jody and Geisler 189

-

• First episodes require lower dosages of antipsychotics.Reference McEvoy, Hogarty and Steingard 193

-

• Time to remission increases for each subsequent episode.Reference Lieberman, Alvir and Koreen 190

-

• With accumulation of relapses, a rather abrupt way of relapsing seems to emerge, which probably is suggestive of the development of a reduced threshold for psychotic decompensation.Reference Birchwood, Smith and Macmillan 194

-

• Refractoriness accumulates at a rate of 16% for each subsequent episode,Reference Wiersma, Nienhuis, Slooff and Giel 195 with recent studies confirming loss of antipsychotic response after a relapse in a subgroup of patients.Reference Takeuchi, Siu and Remington 65 , Reference Emsley, Nuamah, Hough and Gopal 196

-

• The development of an abrupt way of relapse in combination with the accumulation of refractoriness over timeReference Lally, Ajnakina and Di Forti 59 , Reference Carbon and Correll 197 is consistent with the development of sensitization and a “kindling” model.

-

• Long-term disability correlates with the number of relapses.Reference Curson, Barnes, Bamber, Platt, Hirsch and Duffy 198

-

• Reduced gray matter volume is related to total episode duration, but not to the number of relapses.Reference Andreasen, Liu, Ziebell, Vora and Ho 199

-

• The observation that the rate of deterioration is higher at the early phase of the disorder is in accord with a recent model, which suggests that mainly the early phase of schizophrenia is characterized by psychotic symptoms.Reference Fountoulakis, Dragioti and Theofilidis 187

Conversely, the following arguments are against such a suggestion:

-

• Deterioration has begun already before the onset of florid psychotic symptoms, during the premorbid period.Reference Cannon, Jones and Huttunen 200 , Reference Fuller, Nopoulos, Arndt, O'Leary, Ho and Andreasen 201

-

• The deterioration accumulates rapidly during the early years, but tends to reach a plateau later in the illness course,Reference McGlashan 202 although there are no convincing data to support a leveling-off of the relapse rate. As discussed above, this could be the result of the predominance of psychotic symptoms early in the course of the disease while after several years they tend to attenuate.Reference Fountoulakis, Dragioti and Theofilidis 187 Another explanation could be that the accumulation of the deficit is not linear and will level off at some point.

-

• The difference in response rates between first and later episode patients with schizophrenia is likely small. 203 –Reference Emsley, Rabinowitz and Medori 206 One meta-analysis in first-episode psychotic patients reported an overall response rate (50% reduction in scale score) of 81.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 77%-85%),Reference Zhu, Li and Huhn 207 while another one in chronic schizophrenia patients with a solid diagnosis of schizophrenia reported a similarly defined response rate being at 51% (95% CI = 45%-57%).Reference Leucht, Leucht and Huhn 8 The biggest problem for the interpretation of these results is that the majority of patients of the FEP samples do not seem to suffer from schizophrenia defined according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria (ie, 6 months requirement of the overall illness), making a valid direct comparison impossible.

Overall, the literature supports the concept that relapses correlate with worse long-term outcome. Continuous antipsychotic treatment is necessary in order to avoid relapses since their way of appearance usually precludes early intervention and immediate resolution of symptoms.Reference Correll, Rubio and Kane 12 Probably, relapses are not the only reason of disease progression and their effect is not linear, but instead it is stronger during the first few years after the disease onset. Unfortunately, this is the period when both patients and their therapists are usually inclined to stop long-term maintenance treatment.

Question 9: Is there a brain volume loss in patients with schizophrenia and what are its causes?

Cross-sectional findings

The first reports with the use of brain CT on possible brain structural change in patients with schizophreniaReference Johnstone, Crow, Frith, Husband and Kreel 208 faced negativistic criticism and rejection on the basis of circular logic and theoretical–ideological arguments.Reference Hill 209 The psychiatric community of the time found it difficult to accept that patients manifested observable brain damage.

Some imaging studies report strong significant differences between patients and controls, 210 –Reference Kubota, van Haren and Haijma 213 while others do report significant differences but those would not survive correction for multiple comparisons.Reference Guo, Li and Wei 174 , 214 –Reference Toulopoulou, Grech and Morris 216 There are also some data in at-risk subjects indicating that brain imaging could be of prognostic usefulness for the identification of those persons at high risk that will eventually develop psychosis.Reference Koutsouleris, Borgwardt, Meisenzahl, Bottlender, Moller and Riecher-Rossler 217 , Reference Koutsouleris, Kambeitz-Ilankovic and Ruhrmann 218 A meta-analysis on cross-sectional volumetric brain alterations in both medicated and antipsychotic-naive patients included 317 studies comprising over 9000 patients. In the 33 studies, which included antipsychotic-naive patients (Ν = 771), volume reductions in caudate nucleus and thalamus were more pronounced than in medicated patients. White matter volume was decreased to a similar extent in both groups, while gray matter loss was less extensive in antipsychotic-naive patients. Gray matter reduction was associated with longer duration of illness. According to these findings, brain loss in schizophrenia is related to a combination of (early) neurodevelopmental processes—reflected in intracranial volume reduction—as well as illness progression. Most of the observed significant results would survive correction for multiple comparisons.Reference Haijma, Van Haren, Cahn, Koolschijn, Hulshoff Pol and Kahn 219

Overall, the imaging data are strong in suggesting that schizophrenia is characterized by loss of total gray matter volume which is probably more pronounced in the temporal lobes. Data concerning other brain regions and structures are relatively weak. It seems that a reduction in interneuronal neuropil in the prefrontal cortex is a prominent feature of the cortical pathology in schizophrenia which is characterized by subtle changes in cellular architecture and brain circuitry that nonetheless have a devastating impact on cortical function. Most volume changes that occur appear to be the result of reduction in neuropil related to less dendritic branching, lower spine density, and smaller cell body size.Reference Selemon and Goldman-Rakic 220 Representative studies are shown in detail in Table 4.

Table 4. Studies on Structural Brain Changes in Patients with Schizophrenia vs Controls

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; DZ, dizygotic; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MZ, monozygotic; PFC, prefrontal cortex; PM, postmortem.

These brain abnormalities seem to be present already at illness onset. This was the conclusion of the Edinburgh High Risk Study (though of doubtful strength because of the presence of multiple comparisons).Reference McIntosh, Owens and Moorhead 231 However, these data were solidly supported by a more recent study, which found that the left hippocampal volumetric integrity was lower in the FEP group (P = .001) at baseline.Reference Goff, Zeng and Ardekani 173 This conclusion is supported by a meta-analysis of 43 studies and MRI data from 965 FEP patients matched with 1040 controls which reported the presence of gray matter volume loss in the temporal lobe of patients with schizophrenia already at disease onset.Reference Radua, Borgwardt and Crescini 232

The data from postmortem neuropathological studies are equivocal. Some studies definitely report no significant difference between patients with schizophrenia and controls,Reference Arnold, Trojanowski, Gur, Blackwell, Han and Choi 221 , Reference Pakkenberg 226 , Reference Thune, Uylings and Pakkenberg 230 others definitely report significant reduction in the number and density of neurons and maybe of glia in the neocortex,Reference Chana, Landau, Beasley, Everall and Cotter 224 , Reference Hof, Haroutunian and Friedrich 225 , 227-229 while some other studies reported significant differences, but these were of questionable strength.Reference Bogerts, Meertz and Schonfeldt-Bausch 222 , Reference Bogerts, Falkai and Haupts 223 Overall, these data suggest that there is no strong histopathological evidence to support the presence of a neurodegenerative or neurotoxic process, including neuronal loss, ubiquitination, dystrophic neurites, astrocytosis, or microglial infiltrates.

Longitudinal findings

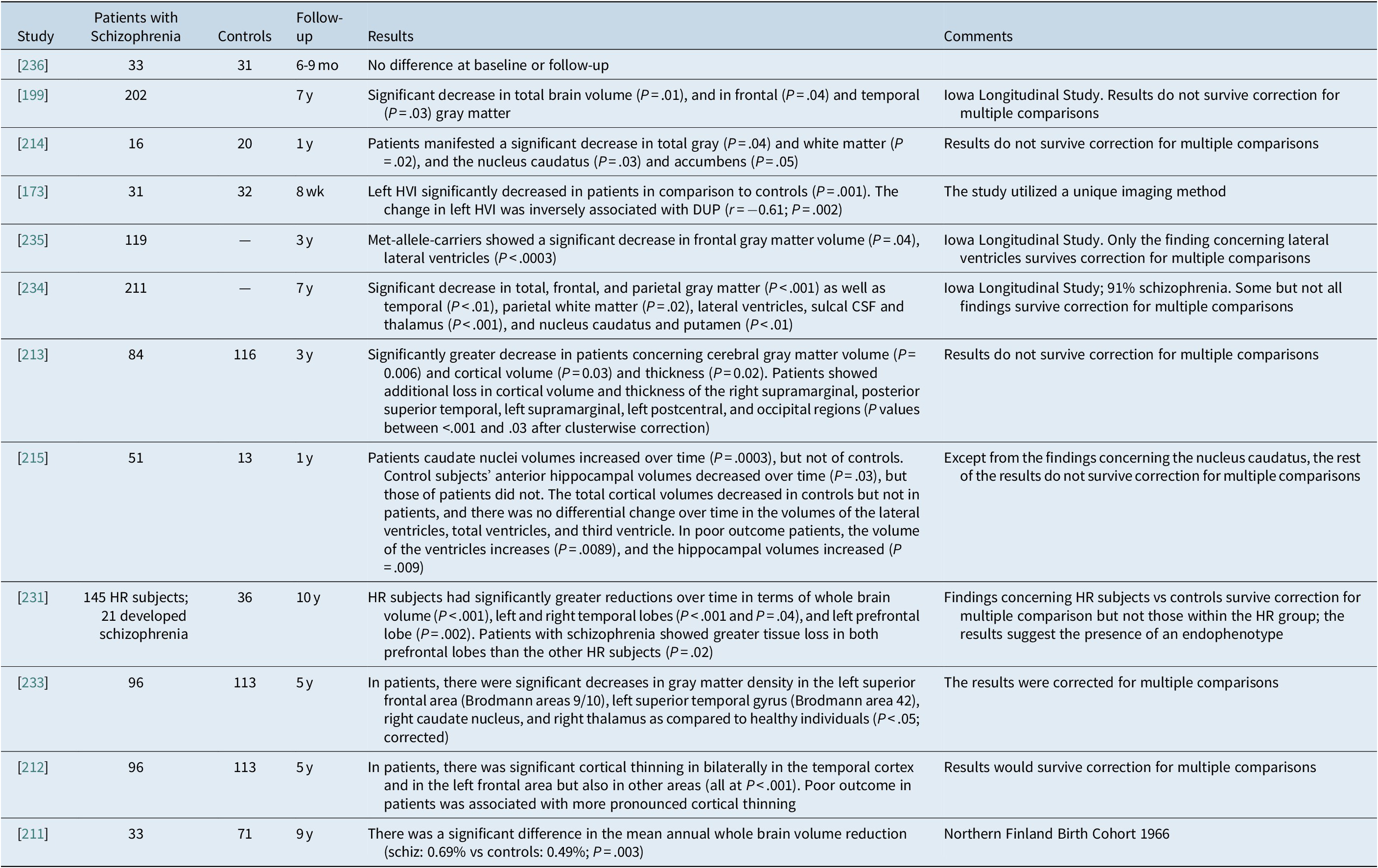

Most studies on the longitudinal course of schizophrenia suggest the progressive loss of brain volume.Reference Goff, Zeng and Ardekani 173 , Reference Veijola, Guo and Moilanen 211 , Reference van Haren, Schnack and Cahn 212 , Reference Lieberman, Chakos and Wu 215 , Reference McIntosh, Owens and Moorhead 231 , 233 –Reference Ho, Andreasen, Dawson and Wassink 235 Some authors do not report such a finding,Reference Ahmed, Cannon and Scanlon 236 while others lose their power after correction for multiple comparisons.Reference Andreasen, Liu, Ziebell, Vora and Ho 199 , Reference Kubota, van Haren and Haijma 213 , Reference Boonstra, van Haren and Schnack 214 The most frequent and reliable findings concerned total brain volume, ventricular enlargement, frontal and temporal gray matter, and the nucleus caudatus. Some data also implicate the thalamus and the hippocampus. The studies in first-episode patients argue that the findings exist before the initiation of antipsychotic treatment and progress semi-independently of treatment. Representative studies are shown in detail in Table 5.

Table 5A. Studies on the Long-Term Progression of Structural Brain Changes in Patients with Schizophrenia vs Controls

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; DUP, duration of untreated psychosis; HR, high risk; HVI, hippocampal volumetric integrity.

A meta-analysis identified 19 studies, analyzing 813 patients with schizophrenia and 718 healthy controls and reported that over time, patients with schizophrenia showed a significantly higher volume loss of total cortical gray matter, left superior temporal gyrus (STG), left anterior STG, left Heschl gyrus, left planum temporale, and posterior STG bilaterally. Meta-analysis of FEP patients showed a more significant pattern of progressive loss of whole cerebral gray matter volume involving the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes and left Heschl gyrus compared with healthy controls. Progressive cortical gray matter changes in schizophrenia occur with regional and temporal specificity, and the underlying pathological process appears to be especially active in the first stages of the disease, and affects the left hemisphere and the superior temporal structures more.Reference Vita, De Peri, Deste and Sacchetti 237

Data suggest associations between reduced total and regional brain volume and poorer outcomes,Reference Van Haren, Cahn, Hulshoff Pol and Kahn 238 including greater negative symptoms and cognitive performance.Reference Ho, Andreasen, Nopoulos, Arndt, Magnotta and Flaum 239

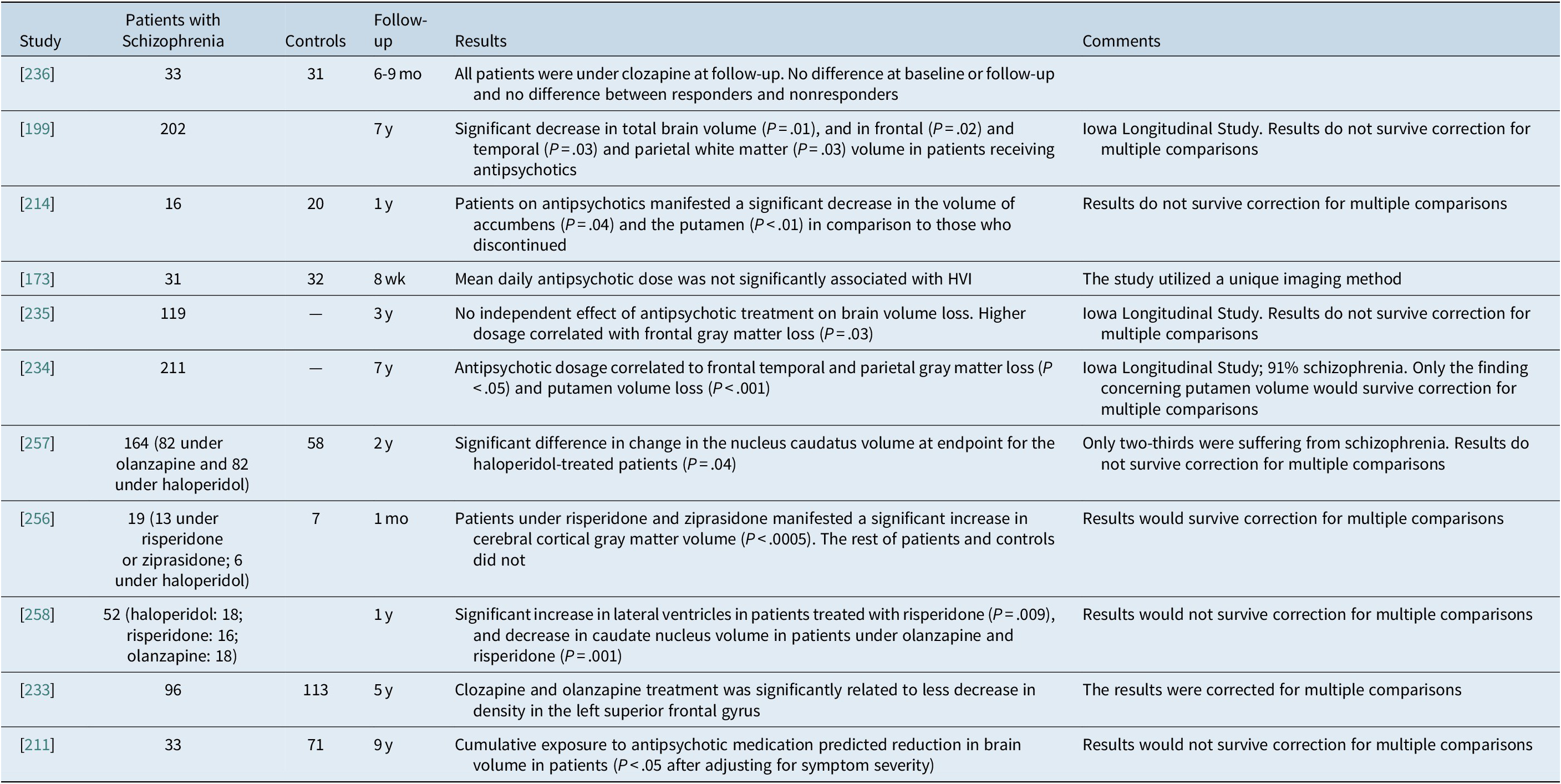

Question 10: Does antipsychotic treatment cause brain volume loss?

As soon as the first reports on ventricular enlargement in patients with schizophrenia were published,Reference Johnstone, Crow, Frith, Husband and Kreel 208 one of the first comments was that this was a consequence of antipsychotic medication treatment.Reference Marsden 91 Since then several authors have attributed these findings to treatment with antipsychotics, cannabis use, diabetes, and hypertension. 239 –Reference Murray 242

Animal studies definitely suggest that exposure to antipsychotics leads to 6% to 15% brain volume reduction. 243 –Reference Vernon, Natesan, Modo and Kapur 245 The biggest problem in the interpretation of these results is that experimental animals do not suffer from schizophrenia; at best, they correspond to a model that tries to mimic some aspects of schizophrenia but otherwise they are “healthy.”Reference Dean 246 Furthermore, the effect of antipsychotics on the brain of non-schizophrenic animals is too strong and beyond doubt, while on the contrary the progressive brain volume reduction after FEP is very small.Reference Zipursky, Reilly and Murray 241 The effect size for the only index which was found in human studies to be significant, that is, whole brain gray matter, ranges approximately from 0.14 (not significant after correction)Reference Vita, De Peri, Deste, Barlati and Sacchetti 240 to 0.36,Reference Haijma, Van Haren, Cahn, Koolschijn, Hulshoff Pol and Kahn 219 while in animal studies the findings are strongly significant and for the total number of cells the effect size was 0.89Reference Konopaske, Dorph-Petersen, Pierri, Wu, Sampson and Lewis 244 or >10% loss.Reference Dean 246 , Reference Harrison 247 If brain volume reduction was due to antipsychotic medication, it should have been much more pronounced, global, and much more clearly correlated with medication, which is not the case. Moreover, there is only regionally circumscribed cell loss in humans supported by stereological cell number estimations. These findings support a loss of oligodendrocytes in the prefrontal cortex (area BA9)Reference Hof, Haroutunian and Friedrich 225 and CA4 subregion of the hippocampus.Reference Schmitt, Steyskal and Bernstein 248 , Reference Falkai, Malchow and Wetzestein 249 Additionally, a recent meta-analysis showed increased microglia density with focus in the temporal cortex.Reference van Kesteren, Gremmels and de Witte 250 Hence, because this cell loss is minimal and localized, the change in brain volume is attributed mainly to neuropil volume loss.Reference Harrison 251 There is no similarity between the findings from the brains of patients with schizophrenia and animal studies neither in terms of quantity nor in terms of quality in contrast to what some authors insist on.Reference Whitaker 163

There is no “creationist creed” in this interpretation; it is the difference between normal and abnormal physiology. In the wider field of medicine, there are several treatments that protect the patient from the harmful effects of the disease process, but if they are given to healthy individuals (or individuals without the specific pathophysiology of the specific disease) they can cause harm, often in the same direction of the disease itself. Such an example is insulin, which protects diabetic patients from developing vascular dementia, but if given to normal people it could cause brain damage because of hypoglycaemia 252 –Reference Rhee 254 especially if occurring abruptly.Reference Puente, Silverstein and Bree 255 Antihypertensive agents, hormone supplements, anticancer medication, and cortisol are among other examples with a similar effect.

Concerning human studies, some authors suggest a clear correlation after controlling for possible confounders between exposure to antipsychotics and brain volume loss,Reference Ho, Andreasen, Ziebell, Pierson and Magnotta 234 others suggest correlations with increased or less decreased brain volume,Reference van Haren, Hulshoff Pol and Schnack 233 , Reference Garver, Holcomb and Christensen 256 some studies did not find any relationship at all,Reference Goff, Zeng and Ardekani 173 , Reference Ahmed, Cannon and Scanlon 236 while others lose their strength after correction for multiple comparisons.Reference Andreasen, Liu, Ziebell, Vora and Ho 199 , Reference Veijola, Guo and Moilanen 211 , Reference Boonstra, van Haren and Schnack 214 , Reference Ho, Andreasen, Dawson and Wassink 235 , Reference Lieberman, Tollefson and Charles 257 , Reference Crespo-Facorro, Roiz-Santianez and Perez-Iglesias 258

A meta-analysis included 43 studies and structural data from 965 FEP subjects matched with 1040 controls and identified conjoint structural and functional differences in the insula/STG and the medial frontal/anterior cingulate cortex bilaterally, and related to antipsychotic exposure.Reference Radua, Borgwardt and Crescini 232 Another meta-analysis of 317 cross-sectional studies (N=9098) on volumetric brain alterations in both medicated and antipsychotic-naive patients included over 9000 patients and 33 of these studies were in antipsychotic-naive patients. In the medicated schizophrenia patients (N=8327)a decreased intracranial and total brain volume was found by 2.0% and 2.6%, respectively. Largest effect sizes were observed for gray matter structures, with effect sizes ranging from −0.22 to −0.58. These authors argue that the main difference between medicated and antipsychotic-naïve patients in comparison to controls concerned the caudate nucleus and the thalamus. However, in the sample of antipsychotic-naive patients, with reference to controls there were significant volume reductions in the caudate nucleus (patients N = 299 vs controls N = 422; d = −0.38, 95% CI = –0.54 to −0.23; P < .001) and thalamus (patients N = 152 vs controls N = 260; d = −0.68, 95% CI = –1.08 to −0.28; P < .001). In contrast, medicated patients did not differ from controls concerning the volume of the caudate nucleus (patients N = 1101 vs controls N = 1154; d = −0.03, 95% CI = –0.14 to 0.07; P > .05) or the volume of the thalamus (patients N = 1168 vs controls N = 1350; d = −0.31, 95% CI = –0.40 to −0.22; P < .001). In fact, the authors are correct only concerning the caudate nucleus since the 95% CIs of the thalamus results overlap. Antipsychotic-naïve patients had significantly smaller caudate nucleus volumes. White matter volume was decreased to a similar extent in both groups, while gray matter loss was less extensive in antipsychotic-naive patients. Gray matter reduction was associated with longer duration of illness and higher dose of antipsychotic medication at time of scanning. Therefore, brain loss in schizophrenia is related to a combination of (early) neurodevelopmental processes—reflected in intracranial volume reduction—as well as illness progression. Most of the observed significant results would survive correction for multiple comparisons.Reference Haijma, Van Haren, Cahn, Koolschijn, Hulshoff Pol and Kahn 219

A recent meta-analysis that has received much attentionReference Vita, De Peri, Deste, Barlati and Sacchetti 240 reported that antipsychotics are responsible for brain volume loss, but it identified only three randomized controlled trials comparing FGA and SGA treatment. These studies are included in Table 5. 256 –Reference Crespo-Facorro, Roiz-Santianez and Perez-Iglesias 258 The meta-analysis reported that for the 56 patients treated with FGAs, there was a significant change from baseline (g = −0.34, CI = –0.60 to −0.08, P = 0.009) while there was no such a difference concerning the 90 patients treated with SGAs (g = −0.19, CI = –0.39 to 0.05; P > .05). Thus, these authors concluded that FGAs are responsible for brain atrophy while SGAs are not.Reference Vita, De Peri, Deste, Barlati and Sacchetti 240 Unfortunately, this conclusion is erroneous, because this analysis in pairs is not an appropriate way to analyze three groups; the correct way would be to analyze all three groups simultaneously and in that case no significant difference would emerge since the confidence intervals overlap.

Table 5B. Studies on the Long-Term Effect of Antipsychotic Treatment on the Progression of Structural Brain Changes in Patients with Schizophrenia

Abbreviation: HVI, hippocampal volumetric integrity.

Thus, although several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported that antipsychotic-treated patients with schizophrenia have smaller brain volumes than untreated patients,Reference Vita, De Peri, Deste, Barlati and Sacchetti 240 , 259 –Reference Torres, Portela-Oliveira, Borgwardt and Busatto 262 this morphological difference cannot be taken as a proof of functional relevance. For example, gray matter reductions in first-episode patients receiving antipsychotics sometimes were associated with poorer outcome,Reference Cahn, Hulshoff Pol and Lems 263 but also sometimes were not associated with poorer outcome,Reference Emsley, Asmal, du Plessis, Chiliza, Phahladira and Kilian 264 and limited longitudinal data suggested that patients stopping antipsychotics have gray matter volume loss, whereas increases were found in patients continuing their antipsychotics.Reference Boonstra, van Haren and Schnack 214 Importantly, comparing a first-episode sample on antipsychotics vs off antipsychotics, patients on antipsychotics, consistently with the structural results of the meta-analyses, had lower gray matter volumes, but better cognition and better functional connectivity between the brain areas.Reference Lesh, Tanase and Geib 265 These data underscore that multimodal assessments are needed that combine structural and functional brain imaging as well as symptomatic, cognitive, and functional clinical outcomes in order to understand better the relationship between antipsychotic treatment and adverse or beneficial effects on the brain and its functions.

Taken together both animal and human studies, it is highly unlikely that antipsychotics cause loss of brain volume in patients with schizophrenia, and the correlation of such changes to antipsychotic exposure in naturalistic studies, when present, is most likely to be the result of confounding factors that determine the treatment strategy and lead to patient selection. Brain volume loss probably occurs in a subgroup of patients who are at a greater need for treatment and is not the consequence of treatment with antipsychotics. On the other hand, the data do imply the possible presence of a protective effect of antipsychotic treatment against brain volume loss (Table 5A,B).

Discussion

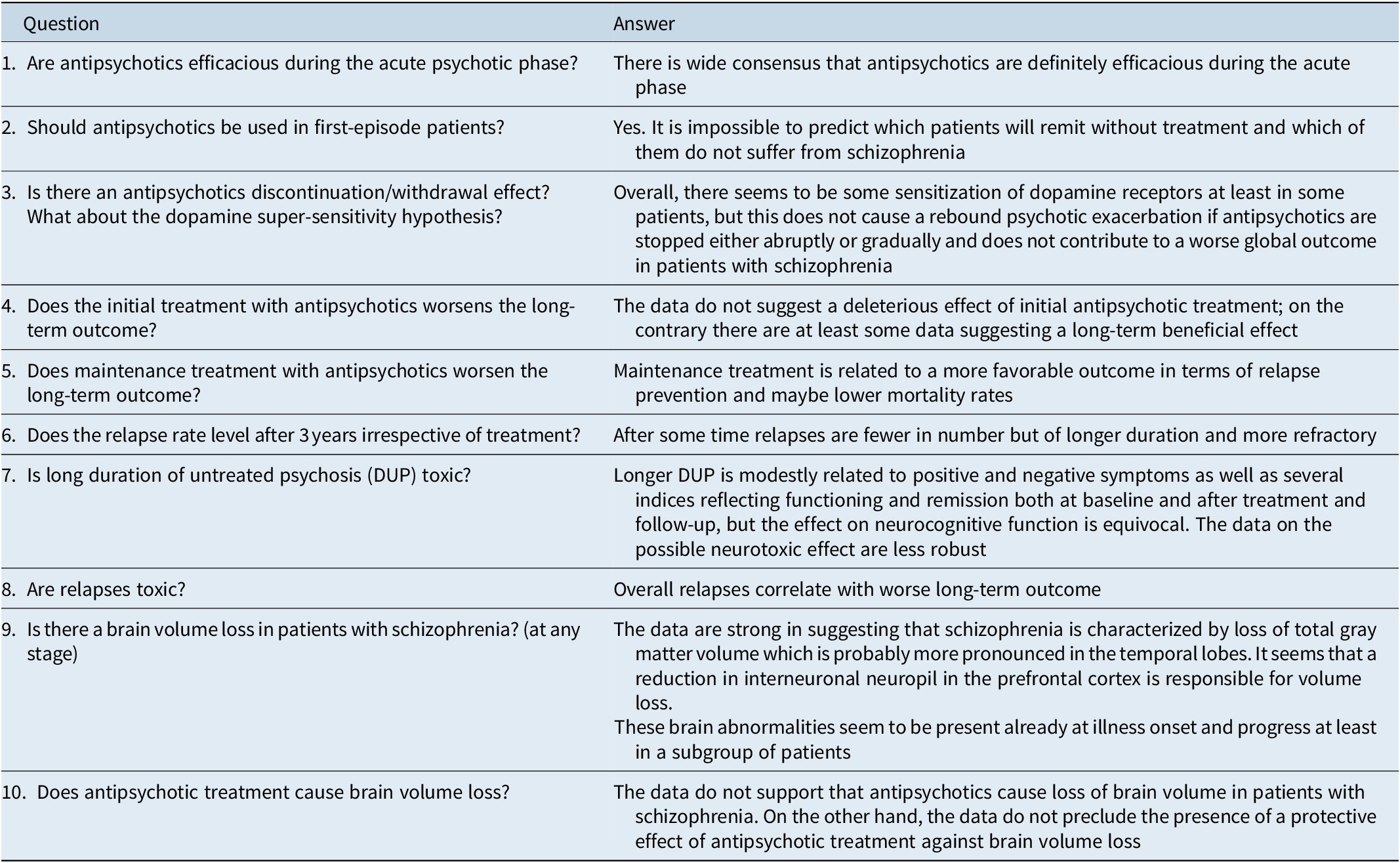

The current paper utilized a selective but comprehensive review of the literature and took into consideration the most relevant arguments developed during the last few years for or against the acute and long-term use of antipsychotics in people with schizophrenia. It is essential to evaluate these arguments into the frame of evidence-based medicine. More specifically, although the current paper did not utilize a systematic review as a proper evidence-based approach would do,Reference Rosenberg, Deeks, Lusher, Snowball, Dooley and Sackett 266 it articulated specific questions and tried to identify pro and con arguments in the literature,Reference Richardson, Wilson, Nishikawa and Hayward 267 utilizing a critical appraisal of the published evidence to identify potential errors, biases, and confounders. 268-270

Eventually, this review arrived at a number of conclusions (Table 6) including that brain volume loss probably occurs in a subgroup of patients who are at greater need for treatment and is not the direct or adverse consequence of treatment with antipsychotics.

Table 6. List of Questions and Answers

Abbreviation: DUP, duration of untreated psychosis.

Overall, the data indicate that antipsychotic treatment is the only definitely proven method for the acute treatment and long-term prevention of psychotic episodes, and especially of schizophrenia. Antipsychotic use includes a number of dangers including tardive dyskinesia and the development of metabolic syndrome.Reference Carbon, Kane, Leucht and Correll 9 , Reference Carbon, Hsieh, Kane and Correll 10 , Reference Galling, Roldan and Nielsen 41 , Reference Vancampfort, Correll and Galling 42 , 271 –Reference Kasper, Lowry, Hodge, Bitter and Dossenbach 274 However, one need not take this risk into consideration and chose lowest-risk antipsychotics whenever possible,Reference Correll, Detraux, De Lepeleire and De Hert 37 , Reference Huhn, Nikolakopoulou and Schneider-Thoma 38 , Reference Solmi, Murru and Pacchiarotti 40 but also put these adverse effects into the context of the risk on untreated illness. In this context, nationwide data are consistent and strong, suggesting that treatment with antipsychotics is related to lower mortality in comparison to no-medication treatment. 53 –Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan 57

As an aid to clinicians, expert opinion and guidelines offer specific advice on how best to treat patients with schizophrenia. Only the Canadian guidelines suggest that patients in symptomatic remission and functional recovery on antipsychotic medication for at least 1 to 2 years should be offered the option to discontinue antipsychotic treatment; the remaining 10 of 11 guidelines did not recommend discontinuation of antipsychotics within 5 years,Reference Takeuchi, Suzuki, Uchida, Watanabe and Mimura 275 and this is in accord with the data reviewed above. Most likely, only patients with a psychotic episode who remitted symptomatically and recovered functionally and who do not fulfill the criteria for schizophrenia should be considered as candidates for medication discontinuation,Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, O'Donoghue and Thompson 276 and some authors propose a shift to a low dosage especially after FEPReference McGorry, Alvarez-Jimenez and Killackey 277 but others insist that prolonged maintenance treatment is essential for FEPReference Tiihonen, Tanskanen and Taipale 100 and life-long maintenance treatment is absolutely necessary for definite schizophrenia.Reference Emsley 278

The presence of brain structural abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia has been positioned at the center of the debate on antipsychotics. It is clear today that neurodevelopmentally related abnormalities do exist, and the causes include among others adverse obstetric events, 279 –Reference Jones and Murray 286 but some authors suggest that additional insults, which trigger stress-related mechanisms of response, are necessary.Reference Howes and Murray 287 , Reference Birley and Brown 288 These additional insults probably involve a dopamine dysregulation mechanismReference Howes and Murray 287 , Reference Howes, McCutcheon, Owen and Murray 289 as well as/including substance, especially cannabis abuse.Reference Van Haren, Cahn, Hulshoff Pol and Kahn 238 All these theories and proposals are open to discussion, and the available data are not conclusive concerning the etiopathogenesis of schizophrenia. The data are conclusive, however, concerning the answer to the question whether brain alterations exist independently of medication treatment. The data are less clear concerning the possible progressive nature of these changes, which seem to be present in a subgroup of patients and, based on the current evidence, appear to be unrelated to antipsychotic treatment in a causal way.

The review of the literature suggests that radically opposing opinions are frequently published in scientific journals, in spite of their weak background. One interesting and potentially dangerous feature of the ongoing debate on the usefulness or potential dangers of antipsychotic treatment for people with schizophrenia is that lay persons publish in scientific medical journals,Reference Whitaker 17 while on the other hand, letters by scholars not accepted for publication by scientific journals are published with an accusatory attitude in lay web sites.Reference Whitaker 163 , Reference Gøtzsche 182 This situation is not entirely new since it had happened in the 1940s and 1950s in the frame of the attack against electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) by William Menninger (1899-1966) and the later critics of ECT,Reference Shorter 290 relating also to the stigma of psychiatric disorders and their treatments.

The results of this review have to be interpreted within its limitations. These include the selective and narrative nature of this review and consensus statement. Additional limitations of the data include lack of long-term randomized controlled trials lasting >3 years, the long list of selection factors in RCTs, lack of long-term studies with state-of-the-art biological marker and outcome tracking, and the current inability to parse patients with schizophrenia into meaningful biological and/or clinical subgroups, including the identification first-episode schizophrenia patients who will not suffer from a second psychotic episode. Furthermore, the effects of DUP on illness status at baseline and on longer term outcomes are related to confounders that need to be understood better. Finally, animal models for schizophrenia are insufficient, and brain morphological studies are influenced by often unmeasured confounders and largely lacked the assessment of brain functioning in the imaging and clinical outcome domains.

In summary, in this review concerning the risk/benefit ratio of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia, the joint WPA/CINP workgroup members conclude that the currently available data strongly support the use of antipsychotics both during the acute and the maintenance phase without suggesting that it is wise to discontinue antipsychotics after a certain period of time, and that antipsychotic treatment improves long-term outcomes and lowers overall and specific-cause mortality.

Disclosures

Dr. Fountoulakis has received grants and served as consultant, advisor, or CME speaker for the following entities: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, the Pfizer Foundation, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Shire, and others. Dr. Moeller received honoraria for lectures or for advisory activities or received grants by the following pharmaceutical companies: Lundbeck, Servier, Schwabe, and Bayer. He was president or in the Executive Board of the following organizations: CINP, ECNP, WFSBP, EPA, and chairman of the WPA section on Pharmacopsychiatry. Dr. Kasper within the last 3 years received grants/research support, consulting fees, and honoraria from Angelini, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals AG, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Janssen, KRKA-Pharma, Lundbeck, Neuraxpharm, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Schwabe, and Servier. Dr. Tamminga received an investigator-initiated grant by Sunovion, has acted as AdHoc advisor to Astellas, and participated as member to advisory boards for Karuna and Kynexis. Dr. Yamawaki has no conflict of interest pertaining to the current paper. Dr. Kahn acts as consultant for Alkermes, Luye Pharma, Otsuka, Merck, and Sunovion. Dr. Tandon has no conflict of interest pertaining to the current paper. Dr. Correll has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Sumitomo Dainippon, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva. He has provided expert testimony for Janssen and Otsuka. He served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck, Rovi, Supernus, and Teva. He received royalties from UpToDate and grant support from Janssen and Takeda. He is also a stock option holder of LB Pharma. Dr. Javed has no conflict of interest pertaining to the current paper.