Dvorˇák and America

Kevin Deas narr and bass-bar, Edmund Battersby pf, Benjamin Pasternack pf

University of Texas Chamber Singers, James Morrow cond

PostClassical Ensemble, Angel Gil-Ordóñez cond

Naxos 8.559777, 2014 (1 CD: 76 minutes), $11

‘While America has been thus far able to do the chief things for the dignity of man’, grumbled composer George Frederick Bristow in 1854, ‘forsooth she must be denied the brains for original Art, and must stand like a beggar, deferentially cap in hand, when she comes to compete with the ability of any dirty German village’. Fresh off the premiere of his Second Symphony given by Louis Antoine Jullien’s virtuosic orchestra, Bristow (1825–98) was livid that the New York Philharmonic had consistently neglected to perform his music. The snub was especially grievous because he had also been a professional member of the orchestra for over ten seasons. Blaming the orchestra’s German contingent for the whole affair, he asked, ‘Is there a Philharmonic Society in Germany for the encouragement solely of American music?’Footnote 1 A public argument with critics and other orchestra members raged over the course of several weeks, and Bristow became so disgusted that he resigned his position.

Not long after Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) arrived in the United States in 1892, he offered a few controversial remarks of his own. ‘I am now satisfied’, he told a reporter for the New York Herald, ‘that the future music of this country must be founded upon what are called negro melodies. This must be the real foundation of any serious and original school of composition to be developed in the United States’.Footnote 2 He reasoned that if Americans wanted to break away from German compositional models, they should try to find inspiration in folk music sources – ‘products of the soil’, as he called them. Boston composer John Knowles Paine (1839–1906) would have none of it: ‘The works of Mozart, Mendelssohn, Berlioz, Liszt, Rubinstein and others are far less national than individual and universal in character and style’. Since the United States was a fusion of immigrant cultures, he thought, ‘American music more than any other should be all-embracing and universal’.Footnote 3 As in Bristow’s case, the exchange launched a firestorm of commentary across the ideological spectrum.

Separated by 40 years, these episodes illustrate the two chief concerns of American symphonic composers throughout the nineteenth century: how to get a piece of music performed and how it should ultimately sound. The two items under review here – recordings that feature Bristow’s music from the mid-1850s and Dvořák’s from the mid-1890s – offer exceptionally clear snapshots of classical music culture in the United States across a span of nearly half a century. But the two periods are not as distinct as they may seem at first, for Bristow was still actively composing when Dvořák arrived in the United States. Taken together, these two recordings allow us to consider that Bristow’s concerns about finding performance outlets and Dvořák’s about musical style were really two sides of the same coin.

The recorded legacy of nineteenth-century American orchestral music is spotty at best. (And here, of course, I include Dvořák in the category ‘American’, since he wrote the music in question while living in the United States.) Conductor Karl Krueger (1894–1979) and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra released several LP records of symphonic works by Bristow, Paine, George Whitfield Chadwick (1854–1931) and Amy Beach (1867–1944) as part of the Society for the Preservation of the American Musical Heritage series from the 1960s. This project was the first concerted effort to bring older American works before the public. Outside of Krueger’s endeavour, Zubin Mehta and the New York Philharmonic (New World Records), Neeme Järvi and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra (Chandos) and JoAnn Falletta and the Ulster Orchestra (Naxos) have all released a small handful of noteworthy recordings that feature symphonic works by nineteenth-century Americans.

The dearth of recordings of this music – to say nothing of live performances – is due in part to the lack of reliable (or even accessible) editions. Krueger tended to use scores and parts derived from unedited manuscript copies in the Free Library of Philadelphia’s Edwin A. Fleisher Collection of Orchestral Music. He also made cuts and other alterations that suited the demands of his hurried enterprise.Footnote 4 Mehta, Järvi and Falletta chose works that were published commercially around the turn of twentieth century but were not available in critical editions when the recordings were made. Fortunately, scholarly interest in this repertoire has grown substantially over the last decade or so, leading to new critical editions of symphonies by Bristow, Paine and Leopold Damrosch (1832–1885), overtures by Chadwick, and the surviving orchestral works of Charles Hommann (1803–c. 1872) – all appearing in the Recent Researches in American Music series published by A-R Editions. It is now possible that the recorded legacy of this music (and public interest, one hopes) will continue to grow in tandem with the scholarly appetite for it.

The repertoire’s precariousness, however, is as old as the music itself. Consider the situation of three prolific composers who converged on New York City in 1853: Bristow, William Henry Fry (1813–1864) and Anthony Philip Heinrich (1781–1861). Their compositional styles could not have been more different. Bristow preferred to write from within the classical tradition. Fry and Heinrich, by contrast, wrote dramatic pieces with idiosyncratic formal designs. But all three ran into difficulties with the New York Philharmonic, suggesting that musical style was only a secondary consideration when the directors filled the orchestra’s programmes. After all, its core repertoire crossed the stylistic spectrum from Haydn and Mozart to Spohr and Berlioz: all Europeans, and mostly Germans. As Bristow argued just before his resignation, national prejudice directed at Americans was unquestionably a decisive factor.Footnote 5 The collection of pieces on the Bristow CD is especially compelling, therefore, because they were all written during this trying period: Symphony No. 2 in D minor op. 24 (‘Jullien’) (1853) and overtures to Rip Van Winkle (1855) and A Winter’s Tale (1856).

Louis Antoine Jullien (1812–1860), a London-based conductor known for his theatrical manner on the podium, arrived in the United States in the autumn of 1853 with a world-class orchestra and quickly began to champion Bristow’s music, including a symphony that the Philharmonic had performed only reluctantly after bowing to external pressure from critics. The young composer understandably found new inspiration upon Jullien’s arrival and provided the conductor with fresh material from a new symphony, his second. Jullien premiered selections from the piece in New York just before year’s end and then took the music on an extensive tour across the eastern seaboard. The response was so favourable throughout the tour that Jullien continued to programme the piece in Great Britain after his return in 1855, and audiences greeted it there with similar enthusiasm.Footnote 6

Conductor Rebecca Miller and the Royal Northern Sinfonia should be commended for choosing to perform from Katherine K. Preston’s magisterial critical edition of Bristow’s symphony, published as part of the Music in the United States of America series, which I have reviewed elsewhere.Footnote 7 Unlike the old Krueger record, Miller’s performance is simply stunning and gives the work the fair trial that Bristow and his compatriots argued they deserved. Miller and the orchestra scrupulously follow tempo instructions, dynamic markings and articulations, while finding sufficient breathing room for artistic interpretation. The string players in particular perform with a spiritedness that translates into succulent resonance during tender moments and gritty (but most welcome) sounds of committed bow strokes in fast passages. My experience was marred only by a condensed volume range seemingly added at later stages of editing. This small quibble aside, the combination of a masterful critical edition with diligent, passionate musicians is a model for this type of collaborative endeavour.

The disc opens with an aggressively brisk interpretation of the first movement’s Allegro appassionato tempo marking – a distinct departure from the Royal Philharmonic’s plodding. Cast in the standard sonata form (minus a slow introduction), the movement contains a mysterious opening theme stated first in the cellos and bassoons and a tender, more lyrical secondary theme. Articulating the form well, the players change character abruptly at the onset of the second theme (bar 82, 1:36), displaying the score’s delicate colouration. Miller follows the standard repeat of the exposition. The movement’s development section marked a significant maturation for Bristow, who literally notated each local tonic with new key signatures in the development of his previous symphony. In the new work, by contrast, Bristow reworked several thematic areas of the exposition, including both main melodies as well as transitional passages, with greater skill and creativity. The atmospheric rendering of the motivic material at 8:42 of the recording is especially noteworthy, as is the trombone solo (bars 245–253) – an unusual timbre. The trombone returns at the onset of the recapitulation, providing a countermelody to the primary theme, given again here by the cellos. The secondary theme returns in D major before the movement closes with the aggressive character of the opening.

Excellent musicianship – from composer, conductor and players alike – continues in the symphony’s later movements: a polka-like dance, a succulent theme and variations and a brooding finale in ![]() . As a veteran orchestral player himself, Bristow had a keen ear for instrumentation and texture that is especially noticeable in the middle movements. The third ‘strain’ of the polka (rehearsal C, pickup to bar 73, 1:33), for example, begins with full woodwind choir but is soon followed by interesting imitative string counterpoint accompanied by pulsating clarinets. Likewise, in the middle of the third movement (bar 88ff, 5:05ff), Bristow created kaleidoscopic changes of texture by rescoring rhythmically dense layers of accompaniment, usually in the strings. This passage is highly reminiscent of moments in the slow movement of Mendelssohn’s Third Symphony (‘Scottish’), but Bristow’s facility and creativity with orchestral colour is abundantly evident. Finally, it is worth noting that Bristow attempted to forge a place in the symphonic tradition with techniques that include cyclic integration (a solo trombone appears through the work, as do reminiscences of the first movement’s opening theme) and the use of a mock ‘choral’ finale – here with a coda marked Grandioso that follows an extended ‘grand pause’.Footnote

8

Miller and the orchestra communicate these fundamental structural components of the work with exceptional clarity.

. As a veteran orchestral player himself, Bristow had a keen ear for instrumentation and texture that is especially noticeable in the middle movements. The third ‘strain’ of the polka (rehearsal C, pickup to bar 73, 1:33), for example, begins with full woodwind choir but is soon followed by interesting imitative string counterpoint accompanied by pulsating clarinets. Likewise, in the middle of the third movement (bar 88ff, 5:05ff), Bristow created kaleidoscopic changes of texture by rescoring rhythmically dense layers of accompaniment, usually in the strings. This passage is highly reminiscent of moments in the slow movement of Mendelssohn’s Third Symphony (‘Scottish’), but Bristow’s facility and creativity with orchestral colour is abundantly evident. Finally, it is worth noting that Bristow attempted to forge a place in the symphonic tradition with techniques that include cyclic integration (a solo trombone appears through the work, as do reminiscences of the first movement’s opening theme) and the use of a mock ‘choral’ finale – here with a coda marked Grandioso that follows an extended ‘grand pause’.Footnote

8

Miller and the orchestra communicate these fundamental structural components of the work with exceptional clarity.

Bristow directed his attention toward music for the stage in the years just following Jullien’s departure. Both of the overtures on the recording were in fact functional numbers rather than standalone pieces. The Rip Van Winkle overture opened Bristow’s grand opera, which he based loosely on the story written by Washington Irving. The Pyne and Harrison troupe, known for its performances of operas in English, premiered the opera in 1855. Likewise, as Preston explains in her liner notes, The Winter’s Tale overture served as the ‘curtain-raiser for a new production of Shakespeare’s play, mounted at Burton’s Theatre on Broadway in February 1856’ (p. 9). Bristow had developed his chops as a violinist playing in theatre orchestras alongside his father, a clarinettist, and these two works demonstrate Bristow’s flexibility as a musician within the diversified environment of New York City at mid-century.

Both pieces are suitably dramatic, and Miller again finds the right character for each. The Rip Van Winkle Overture has a slow three-part introduction followed by a rollicking sonata-allegro in ![]() . Bristow’s scoring tends to be heavier here, with tremolo strings and full brass choirs adding a level of sonic depth not found in the symphony. The Winter’s Tale Overture, by contrast, is sectional in form and suggests various scenes in Shakespeare’s play. The solo woodwinds and brass of the Royal Northern Sinfonia are on target in the recording and offer the vividness of colouration that these theatrical pieces require. A march-like section featuring the piccolo and side drum in The Winter’s Tale Overture (c. 5:50) is especially effective. The orchestra convinces me that either work could be a programme opener in today’s concert halls in place of more famous overtures by Rossini and Berlioz, such as those to Semiramide or Benvenuto Cellini.Footnote

9

. Bristow’s scoring tends to be heavier here, with tremolo strings and full brass choirs adding a level of sonic depth not found in the symphony. The Winter’s Tale Overture, by contrast, is sectional in form and suggests various scenes in Shakespeare’s play. The solo woodwinds and brass of the Royal Northern Sinfonia are on target in the recording and offer the vividness of colouration that these theatrical pieces require. A march-like section featuring the piccolo and side drum in The Winter’s Tale Overture (c. 5:50) is especially effective. The orchestra convinces me that either work could be a programme opener in today’s concert halls in place of more famous overtures by Rossini and Berlioz, such as those to Semiramide or Benvenuto Cellini.Footnote

9

Although Bristow lived until 1898, three years after Dvořák left the United States, the three pieces featured on the recording did not live beyond the 1850s. Bristow nevertheless remained active as a composer throughout his life and found willing performers for several other major works, including three more symphonies. Paine and Chadwick, both of whom had studied in Germany during their formative years, also attained prominence as symphonic composers during this same period. They were active primarily in Boston but succeeded elsewhere with the help of conductor Theodore Thomas (1835–1905), who performed their music on tour and occasionally with the New York Philharmonic, which he directed between 1877 and 1891. All told, Bristow, Paine and Chadwick were easily the country’s three leading symphonists when Dvořák set foot on American shores in 1892 and launched a firestorm with his remarks about compositional style a few months later.

Taking Dvořák’s remarks out of context, later commentators on his ‘American’ period have tended to paint composers like Bristow, Paine and Chadwick with an unfairly broad brush as too stylistically conservative or else unconcerned with issues of national musical identity. As recently as 2004, one German musicologist has written,

Until the 1880s, music was, without exception, from Europe. … And when one of the few American composers wanted to write a symphony, string quartet or other instrumental music, he did not get beyond imitations of German models. Above all, the Leipzig sound of Mendelssohn was popular in America, as in [the music of] George F. Bristow, John Knowles Paine and George Chadwick. No wonder: they had all studied in Leipzig or Berlin.Footnote 10

Bristow, of course, did no such thing. And composers like William Henry Fry, Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829–1869) and Ellsworth Phelps (1827–1913) had strayed far afield from the German tradition. But the broader point is that this author knew very little about Bristow’s later music (or that of his contemporaries) and felt confident making such generalizations precisely because US composers faced such difficulty getting their music in front of the public in the first place. No wonder Dvořák’s comments have always seemed so revolutionary: we don’t generally know what the symphonic ancien régime actually was.

Seeing the problem from a different angle still, the masterminds behind the other recording under review here, musicologists Joseph Horowitz and Michael Beckerman, are attempting to counteract the pervasive belief that the United States did not have much of an effect on Dvořák himself and his music. This notion emerged quite quickly after the 1893 premiere of Dvořák’s ‘New World’ Symphony as certain critics denied any American influence, noted its (supposedly) distinct Czechness or else claimed that its folksy elements transcended any one locale and rose to the level of universal expression. Beckerman has gone to great lengths to show that these attitudes have no basis in fact and that Dvořák was profoundly affected by the music and culture that surrounded him in the places he visited throughout the country.Footnote 11 As Horowitz explains in the liner notes, ‘Beckerman and I are true believers for whom Dvořák figures vitally in late nineteenth-century American culture; and we hear in Dvořák an ‘American style’ transcending the superficial exoticism of Rimsky-Korsakov in Italy or a Glinka in Spain’ (p. 5).

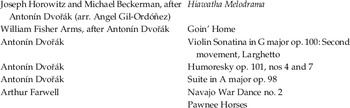

The focal point of the recording is unquestionably the piece called Hiawatha Melodrama, a work created by Horowitz, Beckerman and PostClassical Ensemble director Angel Gil-Ordóñez. The melodrama is a patchwork quilt of passages from Dvořák’s ‘New World’ Symphony, Violin Sonatina (1893), and ‘American’ Suite (1894–95). Each of the six movements also includes the spoken narration of verses from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha (1855), the epic poem that, as Beckerman has shown in exacting detail, proved to be a deep source of personal and musical inspiration for Dvořák. The PostClassical Ensemble and Gil-Ordóñez premiered the piece in Washington, DC in 2013, and it appears on recording here for the first time.

The Hiawatha Melodrama is artfully crafted to blend the drama of the poem with the various characters in the ‘borrowed’ music. Framed on the front end with an unaccompanied recitation from the prologue, the piece comprises Hiawatha’s wooing of Minnehaha, their wedding feast, Minnehaha’s tragic death, the hunt for Pau-Puk-Keewis along with his own cataclysmic death and Hiawatha’s final departure. The liner notes clearly explain the relationships between the source music and the poem, as well as the rationales behind the pairings (drawn primarily from Beckerman’s scholarship). But it will nevertheless be useful here to walk through one example in order to give a sense of how the piece works.

‘Part One: Hiawatha’s Wooing’ opens with the mysterious brass chorale that introduces the Largo from the ‘New World’ Symphony. The narrator then enters unaccompanied but is soon joined by the orchestra, which plays material taken principally from the sonatina. In order to make the transition musically seamless, the compositional team transposed the original key of the symphony to a tonal space better suited to the sonatina movement. The tender character of the sonatina then mates well with the text of the poem, which describes Hiawatha’s first love pangs. An especially touching moment occurs at 2:58 in the recording, where the ‘B’ section of the sonatina is scored for flute, harp and pizzicato strings in order to represent the waterfall that inspires the name Minnehaha, or ‘Laughing Water’. As in the sonatina, a reprise of the ‘A’ material follows this passage but is interrupted by a lyrical, flowing theme from the symphony’s first movement as Hiawatha sets out to find Minnehaha in earnest (6:00). The symphony’s teleological character fits this moment better than the placid sonatina. After Minnehaha decides that she will marry Hiawatha, the music shifts again to the famous Largo melody from the symphony, stated first by an English horn (7:26). The opening line of the accompanying stanza, ‘Pleasant was the journey homeward’, creates a strong connection to the nostalgic associations that the melody has accrued since the symphony was written. As Hiawatha and Minnehaha conclude their journey, the movement ends with solo violin passages recalling both the symphony and the sonatina. Throughout the movement, and the work more generally, the pairings of music and text are truly compelling and ingenious.

The Hiawatha Melodrama also dazzles in areas outside of its composerly charm. First and foremost, it is a melodrama in the truest nineteenth-century sense (though Horowitz says nothing about this in the liner notes). Aside from the fact that The Song of Hiawatha itself was recited on stages for many years after it was first published, the ebbs and flows of emotion here recall similar ‘art music’ melodramas like Richard Strauss’s Enoch Arden (1897), a cathartic musical rendering of the Lord Tennyson poem.Footnote 12 Kevin Deas’s narration is utterly superb, and his liquid baritone is captivating. The narration, in fact, can probably be executed only by a trained musician since the rhythmic elements of the text go hand-in-hand with the musical accompaniment. In certain movements, for example, the composers paired musically diegetic moments in the poem with a melodic style of recitation that could easily fall flat in the hands of a less sensitive performer (track 3, 1:26ff; and track 4, 3:20ff). Deas succeeds spectacularly. Finally, I should note that Gil-Ordóñez’s orchestration of the non-symphonic works is equally impressive. Fully immersed in the soundscape of the ‘New World’ Symphony, he borrowed liberally from Dvořák’s fondness for melodic double reeds (often doubled with strings or other woodwinds) and rich brass groupings. A novice would have trouble noticing the differences between the original and Gil-Ordóñez’s imaginings.

The rest of the disc includes a healthy number of selections that provide a broader context for understanding Dvořák’s American period and his supposed creation of an ‘American style’, including the sonatina and suite previously mentioned as well as excerpts from his Humoresky (1894). Looking beyond Dvořák’s own music, the disc also includes ‘Goin’ Home’ (1922), the ‘ersatz spiritual’ that Dvořák’s student William Arms Fisher (1861–1948) adapted from the Largo movement of the ‘New World’ Symphony, and three pieces by Arthur Farwell (1872–1952), a leader of the so-called ‘Indianist’ movement: Navajo War Dance no. 2 (1904), Pawnee Horses (1905), and a 1937 revision of Pawnee Horses for chorus.Footnote 13 All of the performances of these works are first-rate renditions. Pianist Benjamin Pasternack, in particular, captures the palette of emotions and the rhythmic nuance of the suite and the humoresques.

These inclusions reflect Horowitz’s ongoing efforts to present Dvořák to the public in a multidisciplinary humanistic light. Over the past several years – and with the aid of the National Endowment for the Humanities – he has partnered with local orchestras, universities, grade schools and other community organizations in order to host multiday festivals that bring Dvořák’s American experiences to life and connect them to the present. On the campus of DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, for example, at a festival held in October 2014, Horowitz led a discussion called ‘Dvořák and the NFL’ that drew parallels between Dvořák’s appropriation of Native American music and the ongoing controversy surrounding the Washington Redskins football team. More recently, Horowitz visited the Lake Traverse Indian Reservation (home of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate) for a collaboration with the South Dakota Symphony. The orchestra performed Dvořák’s Ninth Symphony and Black Hills Olawan, a work by Native American composer Brent Michael Davids (b. 1959). The interactive components of these festivals bring a level of nuance to the tricky issues of race, national identity and cultural appropriation raised by Dvořák’s American residency.Footnote 14

Despite the high quality of the music and performances on Naxos’s Dvořák and America, the sensitivity of Horowitz’s festivals is lost in the fixed medium of a recording. The liner notes are relatively terse and tend to valorize Dvořák to the exclusion of the other cultural voices in the conversation. Horowitz explains that ‘the third movement [of the suite] is a jaunty dance not far removed from the world of stride piano’. What will this vague statement imply to a novice listener? That Dvořák somehow inspired the development of jazz piano styles in 1920s Harlem? And what do we gain by hearing Farwell’s voice rather than those of Native Americans themselves (or African Americans, as the case may be)? As in his treatment of Dvořák, Horowitz emphasizes Farwell’s efforts to ‘create a singular American concert style’ rather than grapple with the complexity of the cultural moment.

The multicultural fabric of the United States unquestionably had a profound impact on Dvořák, from the grand design of several works to their most minute details. The ‘B’ section of the sonatina, for example, ends with a series of colourful chords that land on a dominant seventh with a lowered fifth (spelled as a French augmented sixth), lending the passage a certifiably ‘jazzy’ character. This unconventional harmonic language (for the idiom) also pervades the suite and the fourth humoresque. But is Dvořák really the hero of the story for making these sounds, as the disc would lead us to believe? What would Bristow think? He was a septuagenarian by the time Dvořák left the United States and had spent his whole career fighting against American musical dependence on Europe. Was Dvořák telling them something they had really never heard before? Probably not. But to do our part to secure the full legacy of nineteenth-century American classical music, I recommend buying both outstanding discs.