BACKGROUND

Delirium is a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by disturbances of consciousness, attention, cognition. and perception. It has an abrupt onset, a fluctuating course, and an underlying etiology (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Other frequent symptoms of delirium include various mood changes, sleep/wake cycle disturbances, psychomotor abnormalities, and language abnormalities (Trzepacz et al., Reference Trzepacz, Breitbart and Franklin1999).

Since the presentation of delirium varies clinically, subtypes based on psychomotor alterations have been designated. These subtypes are considered relevant to the detection, etiology, phenomenology, management, and prognosis of delirium (Camus et al., Reference Camus, Gonthier and Dubos2000; Marcantonio et al., Reference Marcantonio, Ta and Duthie2002; Meagher, Reference Meagher2009; Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Leonard and Donnelly2011; O'Keeffe & Lavan, Reference O'Keeffe and Lavan1999; Stransky et al., Reference Stransky, Schmidt and Ganslmeier2011). However, divergences have appeared with different approaches to determining these subtypes. While some studies based their determination of subtypes on clinical impressions (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008b ), others implemented psychomotor items from delirium rating scales (de Rooij et al., Reference de Rooij, van Munster and Korevaar2006; Marcantonio et al., Reference Marcantonio, Ta and Duthie2002)—namely, the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Roth1997) or the Delirium Rating Scale–Revised-98 (DRS–R-98) (Trzepacz et al., Reference Trzepacz, Mittal and Torres2001); motor items; or symptom checklists (Liptzin & Levkoff, Reference Liptzin and Levkoff1992; O'Keeffe & Lavan, Reference O'Keeffe and Lavan1999). With these different approaches, concordance reached only 34% in the same sample of delirious patients (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008b ). A number of instruments have been created in the hope of improving the characterization of subtypes (Lipowski, Reference Lipowski1989; Liptzin & Levkoff, Reference Liptzin and Levkoff1992; O'Keeffe & Lavan, Reference O'Keeffe and Lavan1999).

One of the first methodologically evaluated instruments is the Delirium Motoric Checklist (DMC) (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008b ), which includes 30 items, 21 of which describe the hyperactive and 9 the hypoactive subtype. By means of a simplification process, this scale was reduced to the 11-item Delirium Motor Subtype Scale (DMSS) (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008a ). This scale presents four motor subtypes: hypoactive, hyperactive, mixed, or no-motor subtype. An amended version of this scale was later introduced that included 13 items (Grover et al., Reference Grover, Mattoo and Aarya2013). In the search for a briefer assessment tool, the DMSS was further abbreviated with the introduction of the DMSS–4 (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Adamis and Leonard2014), which includes only two hyperactive and hypoactive items, requiring one each for the specific behavior. The DMSS–4 has also been validated in a number of studies (Adamis et al., Reference Adamis, Scholtens and de Jonghe2016; Fitzgerald et al., Reference Fitzgerald, O'Regan and Adamis2016).

However, further research with respect to the subtypes of delirium is required. Our understanding of the subtypes of delirium affect the management and prognosis of patients. Subtyping of delirium has evolved over recent years, but brief instruments remain in demand. The DMSS–4 allows for rapid assessment of motor alterations, but it has not yet been evaluated in an intensive care setting.

METHODS

Patients

All patients in our prospective descriptive cohort study were recruited from the University Hospital of Zurich, a level one trauma center with 39,000 admissions yearly. They were recruited from a 12-bed cardiovascular intensive care unit between May of 2013 and April of 2015. The inclusion criteria were: (1) being adult, (2) being able to provide written consent, and (3) having been under intensive care management for more than 18 hours. The exclusion criteria were: (1) an inability to provide informed consent and (2) a history of substance abuse disorder, aiming to preclude delirium caused by withdrawal.

Procedures

The included patients were informed of the rationale and procedures of our study, and an initial attempt to obtain written informed consent was made. In those patients unable to provide written consent at this time—either due to more severe delirium, their medical condition and sedation, or frailty—proxy assent from next of kin or a responsible caregiver was obtained instead. After their medical condition improved, consent from these patients was obtained. If patients refused participation and consent at the initial attempt or after improvement, they were excluded.

Assessment of delirium was performed by four raters trained in the use of the DRS–R-98 (Trzepacz et al., Reference Trzepacz, Mittal and Torres2001) and DMSS (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008a ), and interrater reliability was achieved by including the DSM–IV–TR diagnosis of delirium and relevant items from the DMSS–4.

The baseline assessment included several steps. The patients were first interviewed. The presence of delirium was then determined according to the DSM–IV–TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Once delirium was determined to be present, the DRS–R-98 was completed. Then the DMSS was completed for assessment of motor subtype presentation, where delirium was categorized as either hyperactive, mixed, hypoactive, or no-motor subtype (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008a ). If required, the assessment was completed by obtaining collateral information from nursing, medical, or surgical staff, the electronic medical record system (Klinikinformationssystem, KISIM, CisTec AG, Zurich), family members, or caregivers.

Measurements

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM–IV–TR)

A diagnosis of delirium was determined by four DSM–IV–TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000): (1) disturbance of consciousness (i.e., reduced clarity of awareness of the environment) with reduced ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention; (2) a change in cognition (such as memory deficit, disorientation, language disturbance) or the development of a perceptual disturbance that is not better accounted for by a preexisting, established, or evolving dementia; (3) the disturbance develops over a short period of time (usually hours to days) and tends to fluctuate during the course of the day; and (4) there is evidence from the history, physical examination, and laboratory findings that: (a) the disturbance was caused by the direct physiological consequences of a general medical condition, (b) the symptoms in criterion (a) developed during substance intoxication or during or shortly after a withdrawal syndrome, or (c) the delirium had more than one etiology.

Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 (DRS–R-98)

The DRS–R-98 (Trzepacz et al., Reference Trzepacz, Mittal and Torres2001) is a 16-item scale with 13 items describing severity, in addition to 3 diagnostic items, rated on a 4-point scale: absent (0), mild (1), moderate (2), and severe impairment (3). The severity rating is clearly specified in the description of the scale. A diagnosis of delirium requires scores of more than 15 points on the severity scale or 18 points on the severity plus diagnostic scales. Motor activity is rated with items 7 (increased) and 8 (decreased motor behaviors). The hyperactive subtype requires a score of 1 and more on item 7, increased motor behavior, in the absence of hypoactivity. The hypoactive subtype requires a score of 1 and more on item 8, decreased motor behavior, in the absence of hyperactivity. The mixed subtype requires the presence of both hypo- and hyperactivity. The no-motor subtype requires the absence of hyper- or hypoactivity as evidenced by the corresponding items. This scale was employed as the reference for the motor subtypes.

The Delirium Motor Subtyping Scale (DMSS)

The original DMSS (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008a ) includes 11 items on a 2-point scale: absent or present (Appendix A). Each of the 11 items (4 hyperactive and 7 hypoactive) are dichotomized as “present” or “absent” (Appendix A). A designation of the hyperactive subtype requires a score of “present” on two or more of items 1–4, while the hypoactive subtype requires a “present” on either item 5 or 6 and a “present” on at least one of items 7–11. The presence of both hyperactivity and hypoactivity as defined above is classified as mixed subtype, while not meeting the criteria for either hyper- or hypoactivity is designated as the no-motor subtype. The items are rated according to observed motor activity over the previous 24 hours. The DMSS classifies delirium into four subtypes: hyperactive, hypoactive, mixed, and no-motor (Trzepacz et al., Reference Trzepacz, Breitbart and Franklin1999).

The Delirium Motor Subtyping Scale–4 (DMSS–4)

The DMSS–4 (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Adamis and Leonard2014) includes four items, two describing hyperactive and two describing hypoactive behavior on a dichotomized scale: absent (0) or present (1). Items 1 and 2 reflect the same items of the DMSS and items 3 and 4 represent items 6 and 8, respectively (Fitzgerald et al., Reference Fitzgerald, O'Regan and Adamis2016). Item 1 describes increased activity levels, as evidenced by more activity or hyperactivity, and item 2 describes loss of control of activity (as evidenced by unproductive movements or movements lacking in purpose). Item 3 describes decreased speed in actions as evidenced by moving more slowly or taking longer to perform simple tasks, while item 4 indicates a decreased amount of speech (as evidenced by less or a lack of spontaneous speech).

Using the same approach as the DMSS, this scale also aims to subclassify delirium into four subtypes: (1) hyperactive, (2) hypoactive, (3) mixed, and (4) no-motor. The hyperactive (1) and hypoactive (2) subtypes require the presence of only one item from either 1 or 2 and 3 or 4. The presence of both hyperactive and hypoactive criteria is classified as “3” (mixed subtype), while not meeting the criteria for either hyper- or hypoactivity is classified as “4” (no-motor subtype). The items reflect observed motor activity over the previous 24 hours.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical procedures were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS; v. 22). Descriptive statistics were implemented for characterization of the patient sample by means of sociodemographic and clinical variables. Patients with delirium were compared to those without delirium using the same procedures. For determination of differences between those with and without delirium, Student's t test was employed for variables on a continuous scale (e.g., patient age). Pearson's χ2 test was performed for items on categorical scales (e.g., the presence of items on the DRS–R-98 or DMSS–4).

For validation of the internal consistency of DMSS–4 items, the value of Cronbach's α was determined and checked. The internal consistency of the DMSS–4 was defined as acceptable if α > 0.7 and good if α > 0.8 (DeVellis, Reference DeVellis2012).

In order to establish the concurrent validity of the DMSS–4, items 1 and 2 of the original DMSS representing hyperactivity and items 6 and 8 representing hypoactivity were recoded into items 1 and 2 (hyperactivity) or 3 and 4 (hypoactivity) of the DMSS–4, respectively. The concurrent validity of the DMSS–4 items (and its defined subtypes) was determined against the DRS–R-98 motor subtypes, as well as against the original DMSS. The motor subitems of the DRS–R-98 were collapsed into two levels: “absent” (0) and “present” (≥1). Cramer's V and Cohen's κ were determined as measures of concordance. Agreement was defined as substantial (0.61–0.80) or perfect (>0.80) (Landis & Koch, Reference Landis and Koch1977). Further, sensitivity and specificity, as well as corresponding positive and negative predictive values (PPVs and NPVs), were calculated and their confidence intervals determined as exact Clopper–Pearson intervals. Interrater reliability was determined by the corresponding values of Fleiss's κ, with agreement defined as substantial (0.61–0.80) and perfect (>0.80) (Landis & Koch, Reference Landis and Koch1977).

A correspondence analysis was performed for graphic representation of the subtypes between scales with a cumulative proportion of inertia set at 95%. For all implemented tests, the significance level of α was set at < 0.05.

RESULTS

Description of the Patient Sample

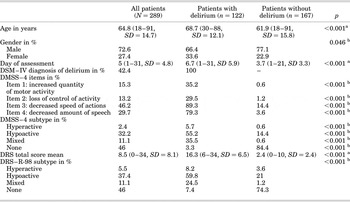

As shown in Table 1, the 289 patients in our study were elderly and predominantly male, and the baseline assessment occurred on day 5 of hospitalization. They scored higher on the hypoactive items of the DMSS–4, and the prevalences of the no-motor and hypoactive subtypes were higher.

Table 1. Sociodemograhic, medical, and psychiatric variables of all patients and those with and without delirium

SD = standard deviation; DMSS = Delirium Motor Subtyping Scale; DRS–R-98 = Delirium Rating Scale, Revised 1998.

a Student's t test. b Pearson's χ2.

Description of Patients with Delirium in Contrast to Those Without

Patients with delirium were older (69 vs. 62 years), predominantly male, and assessed later on in hospitalization (7th vs. 4th day). They achieved higher scores on the hypoactive items than on the hyperactive items, and their total scores were higher than in those without delirium. In those with delirium, according to the DMSS–4 and DRS–R-98, the hypoactive subtype was the most common (55.2 and 59.8%), followed by the mixed subtype (35.5 and 24.5%). In patients with delirium, the hypoactive, mixed, and hyperactive subtypes were documented at higher rates, while the no-motor subtype was most common in patients without delirium.

Internal Consistency and Reliability of DMSS–4 Items

The internal consistency of the DMSS–4 was acceptable (α = 0.75). None of the four featured items exceeded the value of α for the scale, ranging from 0.67 to 0.73 if items were deleted, suggesting a potential for omission.

The reliability between raters was tested with Fleiss's κ, and the DMSS–4 proved to be a reliable instrument. The agreement between raters was substantial (Fleiss's κ = 0.75, 95% confidence interval [CI 95%] = [0.6–0.9], p < 0.001).

Concurrent Validity

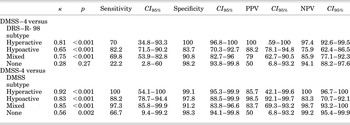

DMSS–4 versus DRS–R-98

In most instances, the DMSS–4 attained substantial agreement with the DRS–R-98 and the original DMSS (Table 3). Agreement with the DRS–R-98 was substantial (Cramer's V = 0.71, p < 0.001) among all subtypes (hyperactive, hypoactive, mixed, none). Agreement was also substantial among the individual subtypes with respect to the hypoactive and mixed subtypes, and it reached “perfect” for the hyperactive subtype. However, agreement was poor when no subtype was present. Similarly, sensitivity ranged from 69.8 to 82.2% when alterations in motor behavior were present, whereas it reached only 22.2% when motor behavior was normal. In contrast, specificity was high and ranged from 83.7 to 100%. For the motor subtypes, the PPV ranged between 79 and 100%, whereas the no-motor subtype reached only 50%. With respect to the NPV, all subtypes exceeded 75% and reached a peak at 98%.

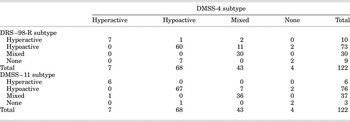

As evidenced by the allocation of subtypes between scales (Table 2), the DMSS–4 items were more sensitive with respect to motor alterations. When the DRS–R-98 indicated no motor alterations, with the DMSS–4 items, those were detected as the hypoactive subtype, and the DRS–R-98 hypoactive subtype as the DMSS–4 mixed subtype, respectively.

Table 2. Allocation of motor subtypes based on DMSS–4 versus DRS–R-98 and original DMSS

DMSS = Delirium Motor Subtype Scale (DMSS), DRS-R-98 = Delirium Rating Scale, Revised 1998.

DMSS–4 versus Original DMSS

Not surprisingly, the agreement between the DMSS–4 and the original DMSS exceeded that with the DRS–R-98 (see Table 3). Agreement was almost perfect between both scales (Cramer's V = 0.90, p < 0.001). Agreement was perfect between motor subtypes (hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed), though to a lesser degree than that found with the DRS–R-98. In contrast, agreement was only moderate when the no-motor subtype was included, Similarly, in contrast to the motor subtypes (88.2–100%), the sensitivity of the no-motor subtype was 66.7%. The PPV was high across all motor subtypes (83.7–98.5%) and only 50% in the no-motor subtype. The NPV remained high across all subtypes (83.3–100%).

Table 3. Agreement, sensitivity, and specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV's and NPV's) of the DMSS–4 versus the DRS–R-98 and original DMSS

DMSS = Delirium Motor Subtyping Scale; DRS–R-98 = Delirium Rating Scale, Revised 1998; CI 95% = 95% confidence interval; PPVs and NPVs = positive and negative predictive values.

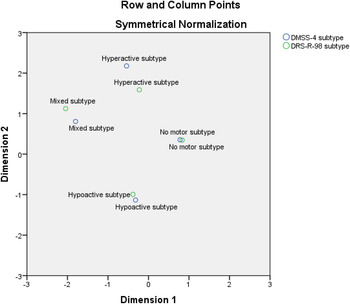

Correspondence Analysis

A two-dimensional reduction indicated the relationship between the subtypes of the DMSS–4 and DRS–R-98, as well as among those of the DMSS. The proximity of points represents their similarity (Figures 1 and 2), and all three scales identified the subtypes correctly (p < 0.001).

Fig. 1. Correspondence analysis representing the relationship between the DMSS–4 items and the motor subtype categories as defined by the DRS–R-98.

Fig. 2. Correspondence analysis representing the relationship between the DMSS–4 and motor subtype categories as defined by the original DMSS.

DISCUSSION

Summary of the Main Findings

Our results demonstrate the fact that the abbreviated DMSS–4 is most reliable and valid in the detection of the motor alterations of delirium and has proved its usefulness in the brief assessment of delirium subtypes in an intensive care setting. In addition, its internal consistency and interrater agreement as a measure of reliability were substantial.

The overall agreement between the DMSS–4 and the DRS–R-98 was substantial, as well as for the motor subtypes (hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed). Agreement was only poor with respect to the no-motor subtype. Similarly, sensitivity was high for the motor subtypes and low for the no-motor subtype, whereas specificity was high across all subtypes. The PPV was lower for the no-motor subtype, while the NPV remained high across all subtypes. The DMSS–4 rated hyper- and hypoactivity more sensitively, which prompted relabeling of the “hypoactive” subtypes as “mixed” and “no-motor” as “hypoactive.” Agreement between the DMSS–4 and original DMSS was perfect with respect to the total for all subtypes, and with respect to the motor subtypes (hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed).

Comparison with the Existing Literature

Two studies validating and replicating the original DMSS arrived at different conclusions. Whereas the Dutch validation study concluded that an abbreviation of the DMSS–11 was recommended (Slor et al., Reference Slor, Adamis and Jansen2014), the replication study increased the DMSS–11 items to 13 (Grover et al., Reference Grover, Mattoo and Aarya2013). Then, using a multisite database, the initial DMSS–4 validation study reduced these items to four and stressed the rapid assessment and high concordance of the scale compared to the original DMSS (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Adamis and Leonard2014). The hyperactive subtype was the most common in that study, followed by the hypoactive and mixed subtypes. Few patients with delirium were included in the no-motor subtype. For the original DMSS and the DMSS–4, there was high-level agreement for the hyperactive and hypoactive subtypes, while agreement for the mixed and no-motor subtypes was lower.

A validation study conducted by Fitzgerald et al. (Reference Fitzgerald, O'Regan and Adamis2016) found agreement between the DMSS and DMSS–4 and high interrater reliability for the DMSS and moderate agreement for the DMSS–4. Some 42.2% of their total sample (N = 143) were delirious at some point in the study. The attribution of motor subtypes was described in the full sample and was comparable between the DMSS and DMSS–4. The most prevalent were the hypoactive and no-motor subtypes, accounting for ~95% of all patients, while the hyperactive and mixed subtypes comprised the remaining 5%.

In another evaluation of the DMSS–4 compared to the original DMSS and the Delirium Severity Index (DSI), the DMSS–4 demonstrated a high internal consistency and concordance with both the DMSS and DSI (Adamis et al., Reference Adamis, Scholtens and de Jonghe2016). The higher sensitivity of the DMSS–4 for motor behavior abnormalities was particularly noted. Its brevity and accuracy in assessment of motor subtypes were also noteworthy.

The DMSS–4 produced similar results in a different patient setting—intensive care management. The rates of hypoactive delirium are generally higher in the intensive care setting (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Pun and Dittus2006), which could explain the high rate of hypoactive delirium found in this study. No differences with respect to internal consistency were found, and the remaining four items remained essential. Interrater reliability attained the same level as that of the other validation studies (Fitzgerald et al., Reference Fitzgerald, O'Regan and Adamis2016). Moreover, agreement as measured by the values of κ was similar, if not superior. In particular, the low sensitivity and PPV in the mixed and no-motor subtypes were already described in the developmental study and were confirmed versus the DRS–R-98, and to a lesser degree against the original DMSS.

Surprisingly, a lowering of Cronbach's α (<0.75) upon deletion suggested a potential for omission of items. This approach did not appear meaningful and might have been caused by the presence of more hypoactive than mixed motor subtypes in the sample, along with the corresponding scores for hyper- or hypoactivity.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Although our study has its strengths, a number of limitations should be noted. Almost 300 patients were prospectively screened and rated for delirium using DSM–IV criteria, the DRS–R-98, and the DMSS. A total of 122 patients with delirium were eventually included. Our approach allowed for comparison of the delirious and nondelirious samples. As one of the first studies, DMSS–4 items were evaluated in a critical care setting, which established its interrater reliability. There was a high prevalence of hypoactive delirium, probably due to the critical care population that we studied and the absence of baseline cognitive recording. Therefore, preexisting cognitive disorders could not be excluded despite prescreening of the medical records. Further studies of the motor subtypes of delirium are required, particularly with respect to their relevance, their impact on hospitalization, and their effect on level of functioning.

CONCLUSIONS

The DMSS–4 is a most reliable and valid instrument in the assessment of the motor subtypes of delirium, particularly with respect to the hyperactive and hypoactive subtypes, and to a lesser extent with regard to the mixed subtype, with shortcomings in the no-motor subtype compared to the DRS–R-98. The limitations in the latter subtypes were caused by the increased precision in recording particular aspects of motor activity, which led to an underestimation of hypoactive behavior with the DRS–R-98. In the end, the DMSS–4 may be superior in assessing the motor alterations of delirium. Agreement was higher between the original DMSS and the DMSS–4. Overall, the DMSS–4 appeared to be more sensitive than the original DMSS with respect to hyperactive motor behavior.

In conclusion, the DMSS–4 is a brief, accurate, reliable, and valid instrument that allows for rapid assessment of the subtypes of delirium.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors hereby state that they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

APPENDIX A

Delirium Motor Subtype Scale (DMSS)

Hyperactive Subtype if definite evidence in the previous 24 hours of (and this should be a deviation from the pre-delirious baseline) at least two of the following:

-

• Increased quantity of motor activity

-

• Loss of control of activity

-

• Restlessness

-

• Wandering

Hypoactive Subtype if definite evidence in the previous 24 hours of (and this should be a deviation from pre-delirious baseline) two or more of the following:*

-

• Decreased amount of activity

-

• Decreased speed of actions

-

• Reduced awareness of surroundings

-

• Decreased amount of speech

-

• Decreased speed of speech

-

• Listlessness

-

• Reduced alertness/withdrawal

* Where at least one of either decreased amount of activity or speed of actions is present.

Mixed Motor Subtype if evidence of both hyperactive and hypoactive subtype in the previous 24 hours

No Motor Subtype if evidence of neither hyperactive or hypoactive subtype in the previous 24 hours

Items from the DMSS–4 are in bold type.