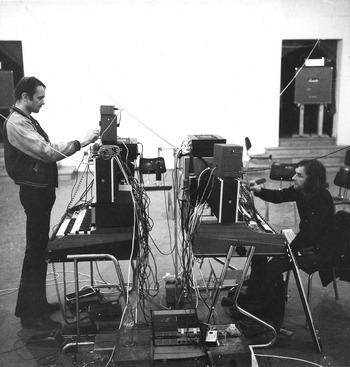

Kraftwerk are a special case indeed. Founded in 1970 by Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider, the Düsseldorf-based group were the most artistically significant German music group of the 1970s. They exerted a formative influence on global pop music with their innovative approach to transpose academic, or ‘new’ electronic music into the realm of pop music. The defining characteristic of Kraftwerk’s work is the prominent incorporation of artistic concepts to which Hütter and Schneider had been exposed at the Düsseldorf Art Academy and within the local art scene. Accordingly, they saw themselves as performance artists rather than musicians.

Both musicians, and in particular Schneider, came from wealthy backgrounds. They had the financial means to purchase expensive synthesisers and other technical equipment for their Kling-Klang studio. Also, ownership of their label released Kraftwerk from the commercial restraints of a record company. Their strategic use of artistic autonomy was inspired by Andy Warhol and, like Warhol’s operation, Kraftwerk constituted a ‘myth machine’.

According to Dirk Matejovski, from Autobahn (1974) onwards, Kraftwerk formulated ‘an aesthetic concept that became ever more perfectly developed’. Initially Hütter and Schneider issued enigmatic interview statements of their artistic intentions to steer reception, but then ‘ceased all self-commentary in the 1980s’. The resulting ‘mystification through communication breakdown’ enabled the Kraftwerk myth to emerge.Footnote 1 Johannes Ullmaier proposes an alternative to the self-created mythologies and tendencies towards monumentalisation that originate especially from the Anglosphere: he proposes a more sober view of the band that undermines hero-worshipping narratives. In his view, the development of Kraftwerk’s oeuvre is perceived ‘as a gradual, … situational niche creation via clever, international, trial-and-error market analysis and adaptation’.Footnote 2

This chapter opens an overview of key Krautrock bands. Yet the extent to which Kraftwerk can be strictly classified as Krautrock requires critical evaluation. Such a subsumption is certainly unproblematic regarding their first three albums alone, Kraftwerk (1970), Kraftwerk 2 (1972), and Ralf & Florian (1973). But it was precisely this trio of albums that Kraftwerk – in a move no other band discussed in this volume ever did – disavowed and exorcised from their œuvre. Instead, they made their next album, Autobahn (1974), the official starting point of their discography. Whereas its B-side is still strongly influenced by the Krautrock sound of the first three albums, the title track, which takes up the entire A-side, heralded no less than a paradigm shift in the history of German popular music: the advent of electronic pop music.

Kraftwerk’s claim to autonomy in the field of pop music is based on their definition of their artistic production as a pop-cultural Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) and a ‘work in progress’. Not only can their output be divided into phases but also into two opposing modes of production: a conventional mode characterised by their ground-breaking concept albums (from 1974 to 1981) and then, from the 1990s onwards, a mode of curation. In the latter, they subjected their work to a permanent process of technical revision, stylistic adaptation, and intermedial expansion, which turned it into a transmedial, ‘open work of art’ (in Umberto Eco’s sense).

Finally, the most remarkable feature of Kraftwerk may well be that, more than fifty years after first emerging, they continue to give live performances, now under the sole artistic leadership of founding member Ralf Hütter. In addition to regular tours and festival appearances, Kraftwerk play concerts at prestigious venues such as symphony halls, world-class museums, and prestigious theatres. Their Gesamtkunstwerk approach, which unites sound and vision, has led to an immersive stage show with continuous 3D video projection and a multi-channel sound system based on wave field synthesis technology that creates sculptural sound effects.Footnote 3

Formative Influences

Hütter and Schneider were inspired to develop the concept of electronic pop music in the 1970s by local Rhineland musicians such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, Mauricio Kagel, Pierre Boulez, Pierre Schaeffer, and György Ligeti. These avant-garde composers worked at the famous Studio for Electronic Music, which was founded in 1951 at the WDR public radio station. Equally significant for Kraftwerk were the technical experiments in electronic sound synthesis by the physicist Werner Meyer-Eppler, who was the first person to use the term electronic music in German in 1949.Footnote 4 Hütter and Schneider paid their homage with ‘Die Stimme der Energie’ (The Voice of Energy, 1975), a variant on a speech synthesis experiment conducted by Meyer-Eppler in 1949.

Via the Düsseldorf Art Academy and the local gallery and museum scene, Kraftwerk were influenced by the modernist avant-garde and contemporary Pop Art. Hütter and Schneider also adopted the strategy to subordinate their artistic project to conceptual principles. The latter encompasses far more than the mere fact that their œuvre consists of concept albums only. The band name itself, which translates as ‘power station’, has a conceptual function, since the electricity electronic music requires is generated in a power station. The conceptual approach is also evident in the artistic tactic of disappearing as private individuals behind the uniform group identity. This allowed Hütter and Schneider to reject the myth of authenticity surrounding rock musicians and style themselves as an artistic collective of ‘sound researchers’Footnote 5 and ‘music workers’.Footnote 6

Warhol’s influence, as already explained, looms large over the early work of Kraftwerk. The recurring use of pylons on the minimalist sleeves of the first two, untitled albums was evidently a nod to his serial art. Another important model was local Düsseldorf artist Joseph Beuys, whose conceptual art strategies were adapted by Kraftwerk in various ways. An important link to Beuys’s conceptual approach was provided by his student Emil Schult, who assumed the role of an unofficial band member. Schult guided Hütter and Schneider on how to align their artistic output to overarching conceptual ideas. Furthermore, he not only wrote most of the lyrics but also designed many record covers. Similarly, many ideas for Kraftwerk’s stage presentation stemmed from Schult. For instance, he devised the neon signs featuring the first names of the musicians that can be seen on the back sleeve of Ralf & Florian.

Industrielle Volksmusik from Germany (1970–1974)

Music journalists have made various attempts to label Kraftwerk’s electronic style of pop music. In addition to ‘synth pop’, Kraftwerk themselves suggested labels such as ‘electro pop’, ‘robo pop’, and ‘techno pop’ – the latter being one of the tracks on the album Electric Cafe (1986). Asked about the original artistic idea behind Kraftwerk’s music, Hütter told an interviewer: ‘To create music that reflects the moods and sentiments of modern Germany. That’s why we named our studio Kling-Klang [literally ding-dong], because those are typical German onomatopoetic words. We call our music industrielle Volksmusik from Germany.’Footnote 7

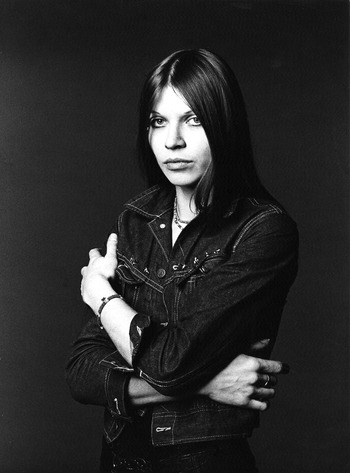

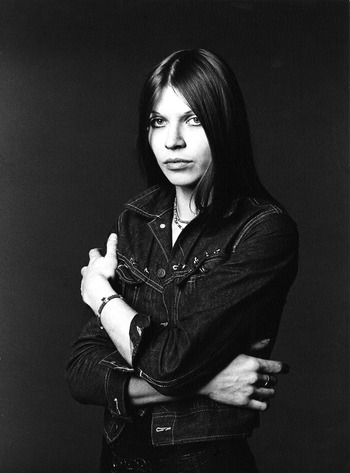

Illustration 6.1 Kraftwerk dolls.

This odd concept name, which literally means ‘industrial folk music’, requires critical analysis since it neither regards industrial music nor folk music in the received sense. The emphatic qualification ‘German’ is easier to comprehend: it reflects Krautrock’s impetus to create an alternative to the dominant, cultural imperialist model of Anglo-American rock/pop music. Kraftwerk, however, did not search for inspiration in cosmic expanses (like ‘Berlin School’ bands such as Tangerine Dream or Ash Ra Tempel), in the music of foreign cultures (like Can, Agitation Free, Popol Vuh etc.), in modernist aesthetics like the cut-up technique (like Faust), or in jazz (like Embryo). Rather, Hütter and Schneider decided to focus on forgotten German cultural traditions (such as the Gesamtkunstwerk, Bauhaus, or Expressionism) and often emphasised their Germanness, especially to anglophone interviewers. Thus, according to Melanie Schiller, ‘not least because of their German band name, they were an exception’Footnote 8 among the important Krautrock bands.

Kraftwerk also gave their songs exclusively German titles. The tracks on the first four albums can be categorised as follows: firstly, terms from electrical engineering, such as ‘Strom’ (Current), ‘Wellenlänge’ (Wavelength), or ‘Spule 4’ (Coil 4); secondly, German onomatopoetic or compound words such as ‘Kling-Klang’ (ding-dong), ‘Ruckzuck’ (in a jiffy), or ‘Tongebirge’ (Mountains of Sound); thirdly, programmatic terms from the field of music: ‘Tanzmusik’ (Dance Music) or ‘Heimatklänge’ (Sounds of Home). Therefore, the ‘industrial’ in industrielle Volksmusik does not primarily refer to factories – although the modernist redefinition of noise as music played a role in Kraftwerk’s work, along with their self-designation as ‘music workers’ – but rather to modern technology, in particular electronic machines that allow a new type of music to be made.

Kraftwerk understand this electronic music – against the background of the industrialisation and modernisation of post-war Germany – as constituting ‘Heimatmusik’ (ethnic/homeland music). As the band once proudly stated in a press release: ‘We make Heimatmusik from the Rhine-Ruhr area.’Footnote 9 Kraftwerk’s key work ‘Autobahn’, a homage to the extensive network of motorways in their home federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia, is a case in point. This piece of music is ‘industrial’ not only by virtue of its electronic nature but also in view of sound effects such as a car door slamming, engine noises, and vehicle horns. These noises, which Kraftwerk simply took from a library record, evoke the sonic presence of the Volkswagen engine that, as it were, drives the very motorikFootnote 10 of the track.

The meaning of the polyvalent concept of ‘Volksmusik’ becomes more apparent if we consider instrumental pieces like ‘Heimatklänge’ or ‘Tanzmusik’. The romantic simplicity of their melodies is striking. They are clearly alluding to the German folk song tradition but, at the same time, they highlight the electronic instrumentation that makes them modern versions of traditional folk songs. Autobahn, as an album, unites both properties in the contrast between the monotony of the ‘industrial’ title track and a ‘folk’ composition like ‘Morgenspaziergang’ (Morning Walk), which features electronic birdsong and gentle flute sounds. Kraftwerk’s Volksmusik, though harking back to folk tradition, must hence be understood as the ‘music of the people (Volk)’, that is, the populus; ultimately, it is a literal translation of the English term ‘pop music’ into German. The seemingly opaque expression industrielle Volksmusik could thus be simply rendered as ‘electronic pop music’ in English.

Although Autobahn was not completely electronically recorded, the album steered pop music into hitherto unexplored realms. This quantum leap, however, went largely unnoticed at first. As of the release, there was only one review in the German music press. It rated the title track as a ‘a car ride with whimsical music and a lot of drive’ but found that ‘the vocals, which are used for the first time, as yet lacked their own style’.Footnote 11

The initial reception in Britain – inevitably riddled with Germanophobic clichés – was similarly disparaging. ‘Odd noises, from percussion and synthesiser drift out from the speakers without any comprehensible order while a few words are muttered from time to time in a strange tongue. … Miss,’Footnote 12 rated one reviewer, while another opined, ‘Synthesizer-tweakers Hutter and Schneider try for a concept – a drive down the motorway – and convincingly blow the few avant-garde credentials fans of their earlier work awarded them. … Simple minds only.’Footnote 13

In the United States, however, Autobahn became a surprise success; the magazine Cash Box, for example, had only praise: ‘Ethereal, inspired and well-conceived, Kraftwerk relates through electronic wizardry and soaring synthesizer tracks the moody feeling of motoring along the road. … Lovely and interesting.’Footnote 14 A heavily cut single version of the title track soared to number twenty-five on the Billboard charts, subsequently catapulting the album to number five on the album charts, where it remained for more than four months. Kraftwerk were now a force to be reckoned with.

Retro-Futurism (1975–1977)

Autobahn indeed marks the inauguration of Kraftwerk’s core œuvre in that – at least as far as the title track is concerned – it represents their first attempt to achieve a pop-cultural Gesamtkunstwerk aesthetic: musical style, car noises, lyrics, cover image, and stage presentation merge seamlessly to form a coherent concept. Radio-Aktivität (Radio-Activity, 1975), then became Kraftwerk’s first complete concept album. The record was also fully self-produced in the band’s own Kling-Klang studio and recorded entirely electronically. With a playing time of thirty-eight minutes, the album resembles an experimental radio play as it emulates a radio broadcast, forming a continuous collage of sound effects, instrumentals, spoken word sections, and pop songs.

The play on words in the title is a fundamental aspect of the album: Radio-Aktivität refers both to nuclear energy, a controversial topic in Germany at the time, and the radio as a medium for transmitting political propaganda as well as musical entertainment. This ambivalent neutrality was implied by the album sleeve, which replicated the front and back of a National Socialist Volksempfänger radio. What emerged out of this ‘radio set’, however, was avant-garde electronic pop music. Radio-Aktivität thus undertook a merger of opposites that proved to be one Kraftwerk’s core artistic strategies. This constitutive ambivalence was reflected in the hyphen of the title and the bright yellow Trefoil radioactivity warning sticker that adorned each cover.

This unprejudiced treatment of the topic of nuclear energy caused disgruntlement in left-wing ecological circles, especially since Kraftwerk had themselves been photographed in white protective suits in a Dutch nuclear power plant. The Chernobyl nuclear disaster in April 1986 led Hütter and Schneider, however, to abandon their ambivalent stance on nuclear energy: the demand ‘Stop radioactivity!’ was added to the new recording of ‘Radioactivity’ for the compilation The Mix (1991); also, the line ‘Wenn’s um uns’re Zukunft geht’ (When our future is at stake) was replaced by the unequivocal ‘Weil’s um uns’re Zukunft geht’ (Because our future is at stake). For their June 1992 performance at the Greenpeace-organised anti-Sellafield benefit in Manchester, Kraftwerk also presented a new robot voice intro with a warning about radiation exposure from the Sellafield nuclear facility, which was later supplemented by other places associated with radiation accidents (Chernobyl, Harrisburg, and Hiroshima).

This modification demonstrates paradigmatically Kraftwerk’s understanding of their œuvre as an open work of art subject to a constant process of adaptation and updating. Their sensitivity to political considerations, however, resulted in a loss of ambivalence since it was precisely the tension between diverse thematic interpretations and a neutral presentation that had comprised Radio-Aktivität’s aesthetic value. The musician John Foxx (Ultravox) had described the original version of the title song to be ‘as neutral a Warhol statement as all their songs tend to be’.Footnote 15

This quality of neutrality, in turn, can be linked to Warhol’s artistic ideal of acting as a machine,Footnote 16 and forms a bridge to the man-machine concept because in ‘Kraftwerk there is no individual, experiential emotional language. They reject all emotionality and sensibility. The band members try to present themselves as emotionless musicians.’Footnote 17 Marcus Kleiner therefore considers Radio-Aktivität to embody Kraftwerk’s trademark ‘coldness’ that stands in direct contrast to the Anglo-American tradition. The latter can be described as a ‘narrative of heat and sweat and a history of excitement and sensuality’, which Kraftwerk countered with an ‘electronic coolness that has influenced the history of pop music history to the present’.Footnote 18

Today, the Radio-Aktivität sequence – performed in a mix of German, English, and Japanese and consisting of the tracks ‘Nachrichten’ (News), ‘Geigerzähler’ (Geiger Counter), and ‘Radioaktivität’ (Radioactivity) – is a highlight of every live concert. Visually, the performance is accompanied by video projections of animated warning symbols, excerpts from the original 1975 Expressionist video, and graphics showing nuclear reaction processes, while, musically, there is the shrill beeping of a Geiger counter, earth-shaking bass beats, and a beautifully simple melody – the whole, in total, constituting a magnificent pop-musical work of art.

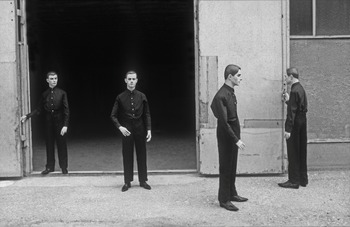

Trans Europa Express (1977), released at the height of the punk explosion, most strikingly embodies Kraftwerk’s important stylistic principle of retro-futurism. Thus, the band’s nostalgic black-and-white cover photo marks a striking contrast to the zeitgeist of the time: the conservatively dressed musicians look like a group portrait from the 1930s or 1940s. While resembling a string quartet, on Trans Europa Express Kraftwerk defined a futuristic sound that made the album an electronic music blueprint that ‘inspire[ed] a new generation of electronic music producers to make sense of a developing post-industrial techno-world based on acceleration and electronics’.Footnote 19

Contrary to the gloomy urban realism of British punk, Kraftwerk evoked nostalgic images of the ‘elegance and decadence’ of the European continent on ‘Europa endlos’ (Europe Endless) and referred to the romantic tradition with the instrumental ‘Franz Schubert’.Footnote 20 Pertti Grönholm argues that such references to the past in combination with innovative electronic music aim to merge utopian ideas with melancholy images to create an aesthetic tension that confronts the present with unfulfilled promises of a better future:

Kraftwerk constructed a cultural and historical space that worked as an imaginary utopian/nostalgic refuge in the cultural situation of 1970s West Germany. … It excludes sentimentality and rejects the idea of a Golden Age but, instead, re-imagines the past as a continuum of progressive development and as a source of inspiration and ideas.Footnote 21

Trans Europa Express also exposes, as already implied in Autobahn, the ambivalent connotation of a means of transportation – in this case rail – in the historical context of Nazi Germany. While the project to build a national network of highways – the Reichsautobahn – was a propaganda tool of Hitler’s regime, the European rail network was used for the deportation of Jews to the extermination camps in the East. After the war, a transnational railway system was introduced to foster the idea of European integration: the Trans Europ Express (TEE) network was in operation from the late 1950s to the early 1990s. In its heyday, it connected 130 cities across Western Europe with regular services every two hours.

Kraftwerk’s ‘Trans Europa Express’, often considered one of their masterpieces, proved crucial to the development of electronic music. David Buckley considers it ‘the most influential possibly in their entire career’.Footnote 22 It consists of a sequence of three tracks that merge seamlessly into one another: the song ‘Trans Europa Express’ is followed by the instrumental ‘Metall auf Metall’ (Metal on Metal), which was originally followed by the short outro ‘Abzug’ (the sound of a train departing) as a separate track.

The thirteen-minute suite is based on relentlessly propulsive repetitions that imitate the velocity of a train. In this musical simulation of a train journey, the hammering sound of the railway wheels on the rails is transferred into music instead of translating the movement of the car journey into a motorik beat, as on ‘Autobahn’. Kraftwerk thus succeeded in converting industrial sounds into machine-generated music. Following in the footsteps of similar efforts by Dadaists and Futurists in the 1920s and 1930s to bring industrial modernism into art, Kraftwerk’s machine music allowed electronic pop music to become a perfect, danceable synthesis of avant-garde and pop.

This is especially true of ‘Metall auf Metall’, the central piece of the ‘Trans Europa Express’ suite. According to David Stubbs, it is ‘one of a handful of the most influential tracks in the entire canon of popular music’, while Simon Reynolds described it as ‘a funky iron foundry that sounded like a Luigi Russolo Art of Noises megamix for a futurist discotheque’.Footnote 23 The repercussions of the furious, dissonant metal machine sound was used throughout British pop music in the 1980s: by Peter Gabriel (‘I Have the Touch’), Depeche Mode (‘Master and Servant’), Visage (‘The Anvil’), as well as by the left-wing industrial collective Test Dept, but also the Düsseldorf industrial pioneers Die Krupps (‘Stahlwerksynfonie’, i.e. Steelworks Symphony) or Einstürzende Neubauten in Berlin, who took the title of the Kraftwerk piece literally.

However, the futuristic sounds from Germany with which Kraftwerk sought to express their ‘cultural identity as Europeans’Footnote 24 had a most decisive influence on African American minorities in urban centres such as New York and Detroit. There, they were adapted into new music styles such as electro or techno and re-contextualised as a means of expressing minority identity concepts. In the early 1980s, the New York DJ Afrika Bambaataa used the ‘Trans Europa Express’ suite for its uplifting hypnotic effect as a musical background to inflammatory speeches by activist Malcolm X.Footnote 25 According to Bambaataa, Kraftwerk never knew ‘how big they were among the black masses in ‘77 when they came out with Trans-Europe Express. When that came out, I thought that was one of the weirdest records I ever heard in my life.’Footnote 26

On the epoch-making track ‘Planet Rock’ (1982), Bambaataa fed the sonic exoticism of industrielle Volksmusik into the energy stream of the Afro-futurist tradition. By doing so, he unwittingly set in motion transatlantic electronic music feedback loops that have been operating ever since: ‘European art music’, according to Robert Fink, ‘is cast, consciously or not, in the role of an ancient, alien power source’.Footnote 27 Martyn Ware (Human League/Heaven 17) summed up the artistic merit of the album as follows: ‘Trans-Europe Express had everything: it was retro yet futuristic, melancholic yet timeless, technical, modern and forward-looking yet also traditional. You name it, it had it all.’Footnote 28

Post-humanism in the Computer Age (1978–1981)

Mensch-Maschine (Man-Machine, 1978) is Kraftwerk’s key work, since the concept of the man-machine lies at the core of their Gesamtkunstwerk aesthetics. ‘Strictly speaking, rather than the LP being a concept, the group themselves were now the concept, and the LP was merely a vehicle to further it’,Footnote 29 Pascal Bussy concludes. The term ‘man-machine’ has appeared in Kraftwerk’s promo statements since 1975 and remains an integral part of live performances today, with a robot voice explicitly announcing the band as ‘the man-machine Kraftwerk’ at each concert.

In addition to ‘Das Modell’ (The Model), Kraftwerk’s biggest pop hit, Mensch-Maschine contains the conceptually significant song ‘Die Roboter’ (The Robots). This signature tune is linked to the doppelgänger mannequins of the four musicians that have replaced the real group members on album covers and promotional photos since 1981. Even more conceptually significant, these puppets appear on stage as substitutes for the ‘music workers’ at every live performance. Their proud statement ‘Wir sind die Roboter’ (We are the robots) can hence be related to the dummy lookalikes as well as the band members. In this respect, the mechanical doubles embody a concretisation or personification of the abstract concept of the man-machine.

The highly influential cover, devised by the Düsseldorf graphic designer Karl Klefisch, shows the real, heavily made-up musicians appearing as artificial robot beings with pale faces. The distinct colour scheme of red, white, and black refers to the colours of the German imperial war flag as well as the National Socialist swastika flag while the (typo)graphic design of the cover directly refers to Bauhaus and Soviet constructivism. Accordingly, Mensch-Maschine can be linked to the attempt made in constructivism to establish a connection between revolutionary art and revolutionary politics; in Kraftwerk’s case, the band presents the pop-revolutionary concept of electronic future music. That is to say, the politically encoded hope for a better future is artistically imagined as a futuristic vision of a post-human synthesis of man and machine.

This technological eschatology is clearly celebrated by Kraftwerk. Yet, the Nazi experience does undermine the optimism of an invariably better future. Kraftwerk, as it were, remain mindful of the danger that the next paradigm shift in the evolution of humanity might easily lead to a relapse into totalitarian rule. The title of the instrumental ‘Metropolis’, which refers to the Fritz Lang’s Expressionist film of the same name – featuring the first robot in film history – also invites such a dystopian reading. After all, Lang’s prophetic vision was of a society that was deeply divided, both socially and politically; the critic Siegfried Kracauer famously condemned the film as proto-fascist in his influential book Von Caligari zu Hitler (From Caligari to Hitler, 1947). As ever so often, Kraftwerk’s retro-futuristic recourse to the German cultural tradition reveals a profound ambivalence.

The album mirrors the pronounced futurism of Mensch-Maschine and, at the same time, refers to a time before modernity. The fact that the cover gives ‘L’Homme Machine’ as the French translation of the album title creates a link to the 1748 treatise of the same name by the early Enlightenment philosopher Julien Offray de La Mettrie. His polemical book offered a radically materialistic view of the unity of body and soul and had a large influence on philosophers from ‘Hobbes and Pascal to Spinoza, Malebranche and Leibniz’. Subsequently, in Enlightenment discourse, ‘the ‘automaton’ became a contemporary cipher for the most diverse aspects in the anthropological and socio-political discussions’Footnote 30 of the true nature of man.Footnote 31

Mensch-Maschine thus positions itself in a broad, cultural-historical net of references and allusions. Despite its clearly futuristic orientation, the album simultaneously incorporates retro elements; one need only look critically at the doppelgänger dummies on stage during their performance of ‘Die Roboter’. As David Pattie soberly observes: ‘The robots do not look like the incarnations of a cyborgian future – if anything, they seem to hark back to a mechanical past.’Footnote 32 Once again, we encounter a deep-rooted ambivalence.

And it is such complexity that keeps Kraftwerk’s album relevant to today’s discussions about post-humanism. Leading experts in the field define objective post-humanist thought as follows: ‘The predominant concept of the “human being” is questioned by thinking through the human being’s engagement and interaction with technology.’Footnote 33 As hardly need be highlighted, this sounds like a summary of Kraftwerk’s artistic project.

With Computerwelt (Computer World, 1981), Kraftwerk released another decidedly futuristic album, which in retrospect proved quite prophetic. A key musical merit of Computerwelt is that Kraftwerk recorded the album almost entirely in analogue, which only underlines its visionary character. This time, Kraftwerk ‘do not predict a robotised, sci-fi future. However, they do predict, with complete accuracy, that our modern-day lives will be revolutionised’Footnote 34 by computer technology: console games, pocket calculators, and online dating, on the one hand, and computer-assisted surveillance, digital finance, and the total digitalisation of society, on the other, are the topics of the album.

Hard to miss on Computerwelt is its warning against social alienation and the political misuse of technology. The original German lyrics of the title track contain lines missing from its English-language version: ‘Interpol und Deutsche Bank / FBI und Scotland Yard / Finanzamt und das BKA / haben unsre Daten da’ (Interpol and Deutsche Bank / FBI and Scotland Yard / tax office and the BKA / have our data at their disposal). In an interview with Melody Maker, Ralf Hütter explained the aim of the album as ‘making transparent certain structures and bringing them to the forefront … so you can change them. I think we make things transparent, and with this transparency reactionary structures must fall.’Footnote 35

This explicitly political statement must be understood against the contemporary historical background. The BKA (Bundeskriminalamt – federal criminal police agency) conducted computer-assisted ‘dragnet searches’ to apprehend terrorists of the Red Army Faction, also known as the Baader–Meinhof Gang. ‘Computerwelt’s’ lyrics state that the BKA is part of an international network of financial organisations and law enforcement agencies, correctly predicting that such institutions would be conducting their daily business digitally today. Similarly, it is hardly an exaggeration to claim that Kraftwerk anticipated the surveillance of digital privacy by state agencies such as the NSA or the British GCHQ.

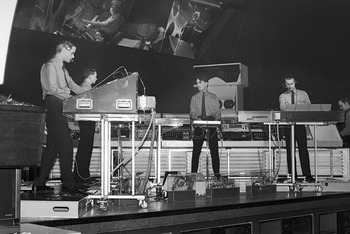

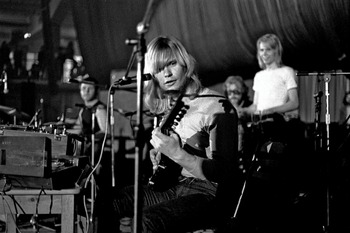

Illustration 6.2 Kraftwerk live, 1981.

With its obsessively repeated sequences of numerals in various languages, Computerwelt’s key track ‘Nummern’ (Numbers) fits perfectly into this context, simulating, as it were, the automated stock exchange deals and transnational financial transactions that characterise today’s digital economy. The track foresaw the proliferating flow of numerical data that has replaced traditional language-based communication and cultural exchange.

In ‘Nummern’, even more importantly, Kraftwerk also found a new musical form, a radically minimalist aesthetic that combined a modernist approach with strict functionality inspired by the Bauhaus: a hypnotic piece of music that was almost brutal in its reduction to a mercilessly hammering beat, audibly anticipating techno. ‘Numbers’, according to Joseph Toltz, ‘is a striking work, not only in the general context of Kraftwerk’s output, but also because it seems so different and more experimental than their other tracks’.Footnote 36 ‘Nummern’ encapsulates the radically new sound aesthetic of Computerwelt, which Kraftwerk had worked on for three years – longer than any previous album. It was true Zukunftsmusik (future music), considering its clinically pure sound and perfect musical realisation of an electronic aesthetic that proved eminently influential transnationally.

Computerwelt concludes and artistically crowns the sequence of five pioneering albums Kraftwerk had released in the seven years since Autobahn. In the 1980s, their electronic music inspired both British synth-pop musicians and African American producers who developed synth pop, disco, new wave, and funk into techno and house. Likewise, Kraftwerk’s use of speech synthesis and electronic processing of vocals, for which Florian Schneider was primarily responsible, became a staple of music production today. With Computerwelt, Kraftwerk’s mission as the avant-garde of electronic pop music had come to an end; from now on, they were competing with the multitude of musicians who pushed their industrielle Volksmusik in new directions.

Digitisation (1983–2003)

After Computerwelt, a paradigm shift set in. With the acquisition of a New England Digital Synclavier, Kraftwerk ushered in the era of digital music production. This, in turn, heralded a new modus operandi: a shift from the production of new tracks to the curation of existing work. Under the aegis of sound engineer Fritz Hilpert, all analogue tapes were painstakingly digitised. This groundwork not only laid the foundation for the 1991 compilation The Mix, on which new versions of Kraftwerk’s most important songs were digitally reconstructed, but also for the transition to digital sound production at live performances.

The follow-up to Computerwelt was announced in 1983 under the title Techno Pop but then withdrawn, only to finally appear in 1986 as Electric Cafe. As the change of title indicates, the conceptual nature of the album was not particularly pronounced: Electric Cafe can be understood as a record about communication or as a self-reflective album about electronic pop music.Footnote 37 The use of several, mostly European languages, explored for the first time in ‘Numbers’, also characterises the erstwhile title track ‘Techno Pop’, which celebrates the transnational omnipresence of ‘synthetic electronic sounds / industrial rhythms all around’ – in large part due to Kraftwerk – in German, French, English, and Spanish lyrics.

‘Tour de France’, which mirrored Hütter and Schneider’s obsession with cyclingFootnote 38 and was to have appeared on the withdrawn Techno Pop, was released as a single in 1983. Some twenty years later, this celebration of cycling turned out to be the basis for Tour de France Soundtracks (2003), Kraftwerk’s final studio album. This often-underrated record features a clear concept and various thematic links to prior albums: it shares not only the motifs of movement und propulsion with Autobahn and Trans Europa Express but also the principle to musicalise sounds produced by modes of transportation, this time cycling. Furthermore, the pairing of cyclist and bicycle, in Hütter’s view, also represents a configuration of a man-machine.Footnote 39 While the concept album Autobahn, which praised an ambivalent national symbol and featured German lyrics for the first time, served as their official debut, Kraftwerk’s remarkable run of studio albums is concluded by a concept album sung (almost) entirely in French that celebrates the most sustainable way to travel.

This reflects a notion that already characterised Trans Europa Express and became increasingly manifest using multilingual lyrics on their albums during the 1980s. Given the country’s fascist history, German identity in the post-war period involved a commitment to the idea of a European community of countries sharing the same culture and common values. Or to put it another way: Kraftwerk were always advocating a political utopia still unfulfilled today, namely, to move from a violent Nazi past into a European future characterised by peace, freedom of movement, and cooperation. On the occasion of seeing Kraftwerk in June 2017 at the Royal Albert Hall, Luke Turner succinctly remarked that ‘an idealised sense of the European is distilled in every vibration of every note and tonight feels like another world’; and considering Brexit, Turner added the valid question: ‘Do we Brits no longer deserve their European futurism?’Footnote 40

A Pop-Cultural Gesamtkunstwerk?

During the band’s fifty-year existence, Kraftwerk’s orientation towards a concept-based aesthetic led to a process in which image, sound, and text were increasingly synthesised to form a unified body of artistic work. This process, however, took place as a successive reaction to external circumstances along conceptual lines, some of which emerged only during the development process. It is further noteworthy that Kraftwerk’s overall multimedia aesthetic not only concerns the audio-visual core of the œuvre (i.e. the officially released music and stage performances) but also such related marketing paraphernalia such as concert posters, tickets, the Kraftwerk website, and merchandise.

Following the release of Tour de France Soundtracks, the artistic activities of the project, now solely led by Hütter, shifted more and more towards the curation of the core work as well as the musealisation of Kraftwerk. With the help of the renowned Sprüth Magers gallery, Hütter moved Kraftwerk successfully from the context of pop music into the field of art. An important prerequisite for this undertaking was the remastered edition of the eight albums from Autobahn to Tour de France in the box set called Der Katalog (The Catalogue), released in 2009.

The now officially sanctioned corpus of albums formed the basis for the concert series Retrospective 12345678 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in April 2012. Further performances of musical retrospectives, each spanning eight evenings, took place at other symbolic venues such as the Sydney Opera House, Vienna’s Burgtheater, the Tate Modern in London, the Arena in Verona, and Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie. In autumn 2011, the stage visuals, which have been presented in 3D technology since 2009 and are billed by Kraftwerk as ‘musical paintings’,Footnote 41 were exhibited at Munich’s renowned Lenbachhaus museum. Increasing recognition of Kraftwerk by the art scene as a performance art collective (rather than a mundane pop band) closed a circle insofar as many of the band’s first public appearances had taken place in Düsseldorf galleries due to a lack of music venues in the early 1970s.

Hütter’s curation activities in the twenty-first century have focused on updating and extending the visual component of the core works. In addition to the introduction of continuous 3D live projections, this involved the revision of all cover designs and a radical revision of the œuvre in the 3-D Der Katalog boxset released in 2017. The first version of Der Katalog already featured some noticeable changes in the album artwork. For example, the Nazi Volksempfänger on the sleeve of Radio-Aktivität was replaced by an intense yellow cover with the nuclear Trefoil symbol in bright red, and the photographs of the real musicians disappeared from the artwork of Trans Europa Express and Mensch-Maschine.

In the radical design overhaul of the 2017 version of Der Katalog, however, all cover designs have been replaced by monochrome record sleeves. This move towards abstraction was accentuated by substituting the numbers one to eight for the album titles, which made the records appear as segments of a coherent, eight-part work. Finally, all the tracks were re-recorded with current equipment – ostensibly during live performances from 2012 to 2016, but possibly in the Kling-Klang studio – and in several cases the original track sequence was altered.

Given the decidedly inter- as well as transmedial nature of the œuvre, one can argue that Kraftwerk firmly belong in the tradition of the modernist Gesamtkunstwerk. Many of their formative stylistic influences, especially Bauhaus and the theatre reform movement, point to modernist updates of Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk model. For example, Erwin Piscator’s vision of a ‘total theatre’ – in which he sought to unite the stage with the cinema – bears an evident resemblance to Kraftwerk’s conceptual notion of moving, three-dimensional ‘musical paintings’; similarly, Piscator’s goal of an ‘ecstatic overcoming of the “only-individual” in a communal experience’Footnote 42 in the theatre audience finds its counterpart in the immersive, audio-visual experience of a Kraftwerk concert. Anke Finger sees ‘teleology as the central tenet’ of the Gesamtkunstwerk aesthetics of modernism, which is why every Gesamtkunstwerk ‘represents something which is in the process of emerging, something which may be perfectly conceived but is not perfectly executed and perhaps never can be’.Footnote 43

Kraftwerk’s astounding fifty-year body of work is a pop-cultural Gesamtkunstwerk that confirms Finger’s theoretical assessment and, in accordance with the pop musical core strategy of ‘re-make, re-model’,Footnote 44 Kraftwerk’s œuvre remains in flux. Their live performances deliver an unprecedentedly immersive experience that fuses art, technology, and music and are a true ‘Kunstwerk der Zukunft‘ (future work of art), to borrow a term from Wagner, which one should experience while it is still possible.

Essential Listening

Kraftwerk, Ralf & Florian (Philips, 1973)

Kraftwerk, Expo Remix (EMI, 2001)

Kraftwerk, Minimum–Maximum (EMI, 2005)

Kraftwerk, Der Katalog (EMI, 2009)

Kraftwerk, 3–D Der Katalog (EMI, 2017)

This chapter focuses on Can, a band who formed in Cologne around 1968 and remained active until 1979 – reforming to record a final album in 1986 and then a single song in 1999. It first considers the formation of the group, and contextualises their position in post-war West German culture as well as West German and international networks of music making. The chapter then surveys and analyses Can’s musical practice, releases, tours, and relationship with the press and public in sections divided by who undertook lead vocals: Malcolm Mooney, Kenji ‘Damo’ Suzuki, and finally a revolving vocalist system (typically Michael Karoli and sometimes Irmin Schmidt). It concludes by providing an overview of Can’s legacy in global music making since the 1970s.

Can and their collaborators fostered a remarkable camaraderie that lasted despite the pressures of the music industry, touring, and negotiating the politics of personalities, individual musical expression, and meaningful collective music-making. They made use of varied approaches to and styles of music, and developed connections and collaborations that left a mark enduring on modern music across the world. Ulrich Adelt noted that the band were uncommonly outward-looking, going ‘beyond Germany’s borders for musical influences’, which enabled them to comment upon and distinguish themselves from ‘the Nazi past and the influx of Anglo-American music into West Germany’.Footnote 1 This search for new influences – sometimes documented in their ironically-named ‘ethnological forgery series’ – extended to collaborating with musicians from different racial and cultural backgrounds. They worked with Malcolm Mooney, an African American sculptor, Damo Suzuki, a Japanese hippie found singing improvised tunes on the street in Munich when travelling through Europe, and, during the late 1970s, Rosko Gee, a bassist from Jamaica, and Anthony ‘Rebop’ Kwaku Baah, a Ghanaian percussionist.

As Beate Kutschke argued, Can represented an international network of ‘politically engaged, New-Leftist’ musicians who ‘shuttled between cities in different countries and continents and exchanged knowledge of musical styles, aesthetics and socio-political issues’.Footnote 2 Can performed across Britain extensively, where they charmed music journalists and enraptured members of the emerging punk, post-punk, and electronic music scenes, and had enough of a following in France to play sporadic concerts and occasional short tours. The band even scored hits: ‘Spoon’ reached number six in the German charts in 1971 and the band skirted the British mainstream with a performance of their number twenty-eight hit ‘I Want More’ on Top of the Pops, a Friday night television institution. However, they are better remembered as a group who cultivated a devoted international cult audience, which included numerous musicians from a diverse range of genres.

Can before Can

Considering the musical training of two of Can’s so-called founders, their place in the rock scene and on the margins of pop success is curious – perhaps only comparable to John Cale of the Velvet Underground, who was taught by the minimalist composer La Monte Young as a postgraduate student. Czukay and Schmidt were conservatoire-trained and studied under Karlheinz Stockhausen, Germany’s most notable post-war composer and a pioneer of electronic music. This brought them into contact with several luminaries of post-1945 Western modern composition, including John Cage, the American composer known for his explorations of chance composition. In interviews, Czukay and Schmidt often characterised themselves as too playful and outward-looking towards the 1960s pop and counter-culture scenes for the rarefied world of composition. Czukay advocated a method that encouraged spontaneity over technique, and Stockhausen had been one of few in the academy who tolerated this approach. Speaking to Richard Cook in the New Musical Express in 1982, Czukay reminisced: ‘I was always being thrown out of music colleges. Stockhausen took me in – he asked me if I was a composer and I had to reply I don’t know. If you are an “artist” you can lie the music away in professionalism.’Footnote 3

Liebezeit, on the other hand, was a jazz drummer before joining Can. He explained his pre-Can career to Jono Podmore, who has edited a book on Liebezeit’s life and approach to drumming.Footnote 4 Liebezeit began performing in high school bands but was picked up by semi-professional rock ’n’ roll bands in Kassel. He soon became aware of American jazz, and jazz drummers Max Roach, Art Blakey, and Elvin Jones caught his ear. This led him to performing with Manfred Schoof’s group. Liebezeit played with an impressive list of jazz stars during his twenties, which were spent between Cologne and Barcelona, including Art Blakey, Don Cherry (they shared a flat in Cologne), and Chet Baker. However, from 1964, Manfred Schoof’s group had moved towards atonal and arrhythmic free jazz, whereas Liebezeit had developed an interest in ‘Spanish, Arabic, Gypsy, North African and Afro-Cuban music’.Footnote 5 In 1968, Liebezeit began to work with Can as they were fellow devotees of his ‘cyclical approach to rhythm’.Footnote 6

Michael Karoli, Can’s guitarist, was ten years younger than his bandmates – Holger Czukay was born in 1937, both Schmidt and Liebezeit were born in 1938. He had moved from Bavaria to St. Gallen in Switzerland as a schoolboy; Czukay had been his guitar teacher in high school. After Karoli had graduated and accepted a place to study law at the University of Lausanne (where he played in several amateur jazz and dance bands), Czukay convinced him to join Can instead. Wickström, Lücke, and Jóri have noted that most West German musicians in the post-1945 period were self-taught and generally first learnt from American GIs and catered to their tastes – few were schooled in the Western art music tradition like Can.Footnote 7 Indeed, even fewer were able to integrate aspects of the emerging pop sounds of the 1960s and free jazz into their approach.

As has been documented in Rob Young and Irmin Schmidt’s comprehensive autobiography/biography, Can: All Gates Open, the band’s initial successes were related to composing film soundtracks.Footnote 8 Schmidt had made waves as a solo film score composer alone but moved towards a collaborative approach when commissioned to provide accompaniment to Peter F. Schneider’s film Agilok & Blubbo (released in 1969) in 1968 – a year of student uprisings, and social and political unrest in Germany and the wider world. They named the new band The Inner Space; it featured Schmidt alongside Czukay, Karoli, and Liebezeit, with a vocal turn from Rosemarie Heinikel, an actor and counter-cultural figure, and accompaniment from David C. Johnson, an American composer who had assisted Stockhausen at Westdeutscher Rundfunk’s (WDR) electronic studio in Cologne. The film attempted to capture and lampoon the politics of the moment; it was a satire of West German politics and the counter-culture that followed two young revolutionaries who conspired to kill an establishment figure until their plan was disrupted by a co-conspirator, Michaela, whom both of the film’s protagonists fall for. Between 1968 and 1979, Can were credited with creating seventeen original film and television soundtracks – a selection of their early soundtrack recordings was released on the compilation Soundtracks (1970).

Can’s success in the film industry was not universally well received. In what may be a case of envious revisionism, Chris Karrer, a member of Amon Düül II and labelmate on United Artists, claimed to Edwin Pouncey in the Wire that Can had knowingly undercut other bands competing for soundtrack work.Footnote 9 This animosity might stem from how, unlike Amon Düül and Amon Düül II, Can shied away from direct political commentary and tended not to play radical squats or communes – although they were generally of the left and anti-authoritarian. Can made their political points and represented the struggles of their generation through musical practice and sound.

The Malcolm Mooney Era: 1968–1969

Soundtrack composition paid for Can’s equipment and recording space. Christoph Vohwinkel, an art collector with aspirations to host an artistic commune, rented them rooms within a castle near Cologne, Schloss Nörvenich. There they practiced in a group that included Malcolm Mooney, and recorded and made their initial live appearances – playing spontaneously composed music – in June 1968. Their first concert was later released as a tape in 1984 entitled Prehistoric Future. The band, as is documented on Prehistoric Future, improvised together extensively, developing, refining, and combining their own approach(es) to musical practice. During Mooney’s time in the band, Can developed a distinctive sound as their rhythm section, Czukay and Liebezeit, played ostensibly simple but intricate, repetitive rhythms. The drums and bass complimented Schmidt’s novel electronic approaches, which incorporated ambient textures and more abrasive sounds in tandem with Karoli’s overdriven and expressive guitar lines and Mooney’s impassioned vocals. Les Gillon suggests that Can’s egalitarian football-based metaphor for improvisation – ‘the collective and non-hierarchical nature of the band as a team’ – could illustrate a broader point about social freedoms that diverged from concepts of freedom in a ‘rational’ capitalist society.Footnote 10 Till Krause and David Stubbs have each argued that the social meanings associated with this approach and the resulting music were powerful in creating new ideas of national identity in West Germany.Footnote 11

Can’s approach to musical practice was innovative and has been explored by journalists and authors both during and after the band effectively disbanded in 1979. They were keen listeners and drew from a broad array of reference points beyond their musical training. Each has spoken about the influence of American bands such as the Velvet Underground and the Mothers of Invention (Karoli is claimed to have introduced his older counterparts to Jimi Hendrix, the Beatles, and the Rolling Stones as well); Liebezeit introduced Czukay to the propulsive rhythm of James Brown’s funk, and they shared enthusiasm for non-Western approaches to rhythm.Footnote 12 Can, in general, were open to non-Western music as documented in their ‘ethnological forgeries’ series, which set to tape their attempts to emulate a range of non-Western musics. Liebezeit and Czukay developed a system based upon painstakingly accurate repetitions and minor variations of drum and bass patterns, which was often understood as a reaction to Liebezeit’s aversion to the unstructured clang and clatter of free jazz.

The band privileged intuition alongside repetition. Schmidt and Karoli often described this approach as telepathy, with Karoli going so far to claim a telepathic relationship with ‘the green eye of the reverb machine’.Footnote 13 The intensity of their approach was described by Mooney when he recalled the recording of their first released album Monster Movie (1969):

Our first record, Monster Movie, to give an example, the A-side is completely controlled, planned. The B-side, ‘You Doo Right’, is a first take in the vocals. There were overdubs added, but the recording, which started at about 11 AM, ended around 11 PM. It was quite a session. I left the studio at one time for lunch, when I returned the band was still playing the tune and I resumed where I had left off and that is how we did ‘You Doo Right’.Footnote 14

What Mooney fails to mention is that the lengthy improvisations that made ‘You Doo Right’ were recorded to two tracks of tape later edited into pieces by Czukay. Throughout the existence of Can, Czukay would edit, cut, and recut two-track tape recordings of their sessions into coherent pieces, only moving to more conventional multi-track recording from the recording of Soon Over Babaluma (1974) onwards. Adelt argues that Can, and particularly Holger Czukay, used recording technology as a means to experiment with recorded sounds ‘long before it became common practice’.Footnote 15 Kai Fikentscher similarly noted that Czukay was, like Phil Spector, George Martin, and Trevor Horn, a pioneer in using the studio as an instrument, demonstrating that ‘recorded music could now be a product of illusionary performance’.Footnote 16 This approach had a bearing on the work of Brian Eno and Kraftwerk, among others, in their Kling-Klang studio.

Can independently released only 500 copies of Monster Movie at first. The first pressing was hoped to attract major label interest, and ultimately led to them signing a record deal with the American label United Artists. The album could be seen as one of the first templates for what would be deemed ‘Krautrock’ as it was codified and adapted into a recognisable sub-genre. Even though Krautrock is frequently questioned by its supposed creators, and its derogatory name misrepresents the work of musicians who were as outward-looking and aware of international music making as possible at the time, Monster Movie contains its hallmarks of repetitive, subtle rhythms and a free approach to guitar, synthesiser, and vocal embellishments. Mooney’s lyrics were existential and surreal. He explored motifs from gospel songs and nursery rhymes, and vented thinly veiled anguish about relationships, sex, desire, reproductive anxiety, and hedonism. The album led to Can’s first mention in the influential British music press (which was distributed across parts of Western Europe and the United States), when Richard Williams gave Monster Movie a positive review in Melody Maker.Footnote 17 The album’s opening track, ‘Father Cannot Yell’, was played twice to a nationwide British audience on John Peel’s BBC Radio One show ‘Top Gear’ on 16 May and 26 June 1970. Several tracks from this time were later rediscovered and released as The Lost Tapes (2012) – they are a testament to Mooney’s importance to Can’s early music.

Mooney left Can and West Germany in December 1969, having experienced heightened anxiety due to the possibility, as an American citizen, of being drafted into the Vietnam War or accused of avoiding the draft. A psychiatrist advised Mooney to return to the Untied States, where he used his experiences as a sculptor to teach art to socially and economically disadvantaged children in ethnically diverse neighbourhoods of New York City.

The Damo Suzuki Era: 1969–1973

Between 1969 and 1971, Can toured across West Germany despite losing Mooney. In 1970, as well as releasing their collection of film soundtracks, Can played numerous Stadthallen (municipal halls), youth centres, a few festivals, and Munich’s trendy Beat Club. In 1970 their concerts were, however, predominantly clustered around Cologne, Essen, and Dortmund within the Rhine–Ruhr area, their home region. During their travels, Can met Damo Suzuki singing improvised songs outside a café in Munich for spare change. They asked him if he would like to perform in their band that evening and he agreed because he had nothing better to do.Footnote 18 Damo Suzuki was born in 1950 near Tokyo in the town of Ōiso. Teenage Kenji – before he was known as Damo, an affectation in honour of his favourite comic book character that he adopted in Europe – became enraptured with the post-war American trope of the romance of the open road, which inspired him to move to Europe. He certainly sought a free approach to lyrics and vocal delivery: Suzuki broadly continued the style pioneered by Mooney, but Can’s new singer was more abstract lyrically and slightly less informed by the blues and rock ’n’ roll canon.

The first album that Suzuki recorded with Can was Tago Mago (1971). The album’s title refers to the Mediterranean island of Tagomago, which is near Ibiza and had putative links – arguably contrived by Can members to impishly mislead the British music press – with Aleister Crowley, the English writer and occultist who was a practitioner of ‘magick’ and libertinism. Crowley, often reduced to his adage ‘do as thou wilt’, had provided inspiration to numerous hedonistic and sexually adventurous, if not rapist, rock musicians and their entourages during the late 1960s and 1970s. The album is remarkable on a sonic level as the lack of separation between each instrument when recording – only three microphones were used – caused sounds to bleed into each other creating unplanned harmonic characteristics and sounds to arise.

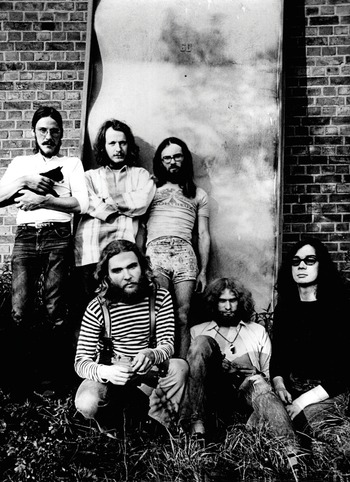

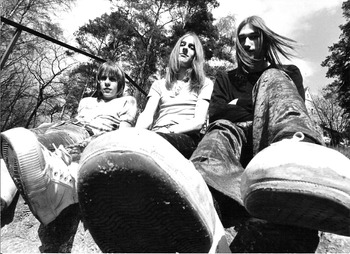

Illustration 7.1 Irmin Schmidt, Holger Czukay, Damo Suzuki, Jaki Liebezeit, and Michael Karoli of Can, early 1970s.

Typically, by the 1970s, when multi-track recording had become well established in the music industry, each instrument could be recorded with its own microphone or direct input cable and heard separately, even when recorded simultaneously (i.e. live). In a conventional recording, these multiple tracks could then be brought together as a balanced multi-instrumental whole once the volume levels were mixed and frequencies blended during mastering. In another departure from conventional recording techniques, Czukay also captured on tape what he termed ‘in-between-recordings’ – the sound of the band jamming but unaware that they were being recorded – and used them in the final mix.Footnote 19 The resulting sounds are darker, and although some of the lyrical content shares themes with Monster Movie there are moments of greater intensity, such as ‘Mushroom’, which interprets the atomic bomb as a moment of symbolic rebirth.

By 1971, assisted by their manager Hildegard Schmidt and accompanied by Damo Suzuki, buoyed by an appearance on WDR Television in January, and with their new album Tago Mago ready for release in August, Can were booked to play most major West German cities and larger towns between March and the album’s release date. At the same time, the band’s appeal in Britain was beginning to grow. In January 1972, for instance, Mike Watts of Melody Maker wrote an effusive – if strewn with casual assumptions about Germans – review of Tago Mago. He teased the prospect of Can’s forthcoming British tour: ‘Can are coming to Britain soon. I’m looking forward to their visit with guarded interest. They sound a weird bunch of geezers.’Footnote 20 After a German tour in February and March, Can indeed toured Britain for the first time. They started at Imperial College on 28 April 1972, then played the university circuit and a few other small-to-medium-sized venues for a month, before returning to the continent to play festivals in France and Germany. They visited later in the year as well, to play a one-off headline concert at The Rainbow in Finsbury Park, London on 22 July, which was impressive considering the venue had a capacity of nearly 3,000 people, much larger and more prestigious than the stops on their tour earlier in the year.

Can’s tours around Germany and Britain demonstrate a willingness to play venues large and small in both the usual cities on the touring circuit and smaller less frequently visited towns. In 1973, taking advantage of Britain’s widespread infrastructure for live rock performances and entry into the Common Market, Can made a somewhat unusual move (for a non-British band of their profile) by visiting smaller towns including Penzance, Plymouth, Westcliffe-on-Sea, and Chatham as part of a concert tour with nineteen stops across Scotland, Wales, and England. They then played their longest French tour (six stops), which included concerts in Paris, Rennes, and Bordeaux. This persistence, alongside the release of two of their most well-loved albums, Ege Bamyasi (1972) and Future Days (1973), meant that despite Damo Suzuki’s departure from the band in late 1973 the band was in a strong position commercially. Suzuki had left Can to become a Jehovah’s Witness like his new wife, and saw life in a band as incompatible with his new faith and lifestyle (Liebezeit recalled that Suzuki ‘left with no warning’ and claimed that he was ‘brainwashed’).Footnote 21 Gitta Suzuki-Mouret, his then wife, has rejected Liebezeit’s account; she claimed that the internal politics of the group left Suzuki feeling isolated and keen to move on.Footnote 22

Thanks to Ege Bamyasi and Future Days, Suzuki’s remaining time in Can was well documented. Ege Bamyasi was the first Can album recorded in a former cinema, soundproofed with army-issue mattresses in the town of Weilerswist (some fifteen miles south of Cologne), which they named Inner Space. The album included ‘Spoon’ which was Can’s biggest hit in West Germany, reaching number six in the charts. Its success was mostly due to being the theme of Das Messer (The Knife), a West German crime thriller that appeared on television from November 1971. The album, which is less intense and more immediately alluring than Tago Mago, received critical acclaim. The lyrics are again existential and often not always clearly meaningful but evocative and filled with imagery.

Future Days was also well-received by critics (the New Musical Express’s eleventh best album of the year). It is punctuated by more prominent electronic sounds, ambient stretches, and Liebezeit’s polyrhythmic drumming than its predecessor. If Ege Bamyasi provided a template for experimental rock, post-punk, and indie musicians, Future Days is perhaps more aligned with Can’s contribution to electronic music – particularly the way that the album’s final track ‘Bel Air’ cleverly progresses through different movements and variations. Suzuki’s vocal approach is more understated, even marginal, but – when heard – he questions the meaning of life in a modern consumer society and interrogates the possibilities of personal freedom within such a society’s constraints.

Can after Suzuki: 1974–1979 (and Beyond)

After Suzuki left, Karoli and Schmidt slightly reluctantly shared vocals. The change did not upset the band’s popular momentum, and Can’s growing profile on the British rock scene allowed them to undertake a twenty-two date tour, with two live sessions on BBC Radio 1 and a television appearance on The Old Grey Whistle Test to play ‘Vernal Equinox’ in 1974. With each of the four Can founders born either just before or just after World War II in Germany, an interesting dynamic emerged, as music fans in Britain, a society often obsessed with the war and prone to seeing Germany and Germans through the lens of Nazism during the 1960s and 1970s, adopted Can most eagerly.Footnote 23 Can tended to get on with British journalists, particularly Sounds’ Vivian Goldman, the daughter of German-Jewish refugees who had escaped the Holocaust to London, and were typically presented as disarmingly funny eccentrics.Footnote 24 Nevertheless, during interviews, the band often seemed compelled (and it is not clear if it was a personal compulsion or at the request of journalists) to describe moments of their youth in post-war West Germany in a way that constructed them as inherently predisposed to anti-fascism – few British or American artists were pressed on their political affiliations in the music press during the early and mid-1970s.

Can recorded six further albums after Damo Suzuki left. The first was Soon Over Babaluma (1974). Perhaps due to capriciousness of the British music press, the album had become somewhat of a joke. However, it has been reappraised since the 1970s and is now viewed as a development of Future Days that informed electronic music styles of the 1980s and 1990s. The line-up of Czukay, Karoli, Liebezeit, and Schmidt alone made two more albums, Landed (1975) and Flow Motion (1976), their first records recorded with a full sixteen-track recording set-up – a distinct move away from their sometimes muddy, if alluring and often unique-sounding, two-track records. Flow Motion is a more pop and disco influenced album in comparison to the more experimental sounds of Landed. It delivered Can’s biggest hit in Britain when ‘I Want More’ reached number twenty-six in the singles chart. This gained them an invitation to Top of the Pops, with Karoli, who was on a safari holiday at the time, replaced by a friend for the performance. The song caught the public’s ear and gained radio play, and between 1974 and 1977 Can seemed to have played almost every town in Britain, in addition to cities where they had a large following – like London and Manchester – where they performed on multiple occasions.

Can’s later albums saw Holger Czukay take a lesser role, and this is often seen as precipitating the band’s split. Czukay moved from bass to manipulating electronics such as transistor radios and tape recorders. He met his replacement on bass, Rosko Gee, when performing on the The Old Grey Whistle Test in 1974, when Gee had appeared backing Jim Capaldi, his former Traffic bandmate.Footnote 25 Can had also taken on an engineer, René Tinner, which marginalised Czukay’s contribution even more. Rebop Kwaku Baah, another former member of Traffic and an accomplished percussionist, was brought in to enhance and embellish Liebezeit’s polyrhythms; however, he ultimately clashed with Czukay.Footnote 26 Notwithstanding an enhanced level of creative tension (Czukay did not contribute to Out of Reach and only edited tape on Can), their final (non-reunion) albums Saw Delight (1977), Out of Reach (1978), and Can (1979) have their merits even if they are less well appreciated than their predecessors by fans and journalists. On these albums, Can warped and explored pop sounds in a way that could be seen as a precursor to the approach taken in scenes such as the 1980s New York underground.

The band disbanded on good terms in 1979. However, in the summer of 1986, Malcolm Mooney temporarily returned to Can for a ‘reunion’ album entitled Rite Time (1989), which was recorded in the south of France. From 1979 onwards, Hildegard and Irmin Schmidt curated Can’s re-releases, box sets, and remix albums through their label Spoon Records. On the band’s thirtieth anniversary, Spoon also promoted the Can-Solo-Projects tour. The showcase exemplified the richness of the original Can members’ solo work and collaborations: Holger Czukay and U-She performed alongside Jaki Liebezeit’s Club Off Chaos; Irmin Schmidt played (with Jono Podmore); and Michael Karoli’s Sofortkontakt! appeared. Many Can solo albums and remasters were released through a collaboration between Spoon and Mute Records – the latter label founded by Daniel Miller, one of the British post-punk musicians influenced by Can and other German musicians of the 1970s that used electronic instruments and employed studio-as-instrument techniques. Czukay’s music arguably gained the most acclaim, perhaps due to high-profile collaborations with Jah Wobble of Public Image Limited, David Sylvian, formerly of the British group Japan, and the Edge, the guitarist in U2. Czukay released much of his later solo work and moments from his back catalogue on Grönland Records.

Can’s Legacy

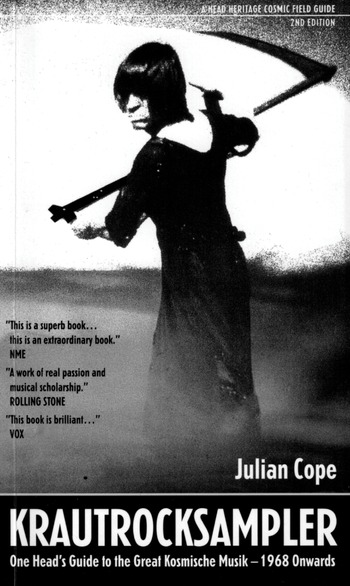

Can have been often cited by post-punk, indie, and electronic musicians as a key influence on their taste and musical practice. Perhaps their most prominent early advocates were British post-punk musicians like Julian Cope of The Teardrop Explodes (author of Krautrocksampler), Mark E. Smith of the Fall, Genesis P-Orridge of Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV, and John Lydon of Public Image Ltd. Alex Carpenter’s essay in this collection notes the influence of Krautrock – and to varying extents Can – on Siouxsie and the Banshees, Bauhaus, Killing Joke, Cabaret Voltaire, and Simple Minds as well. Smith wrote the song ‘I am Damo Suzuki’, which appeared on the This Nation’s Saving Grace (1985), in homage to Can. The lyric refers to aspects of Suzuki’s life and the band’s history, and bemoans the later Can albums that were released on Virgin Records in Britain; the song’s descending bassline has similarities with the Can track ‘Oh Yeah’ from Tago Mago and ‘Cool in the Pool’, a track from Holger Czukay solo album Movies (1979). The band’s appeal to musicians from the north-west of England was also clear in the amalgamation of electronic and avant-garde rock found in bands on the Factory Records label based in Manchester.

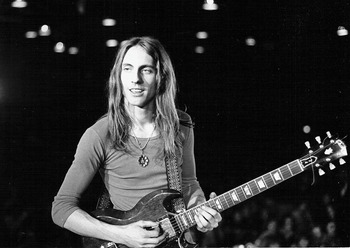

Illustration 7.2 Can live in Hamburg, 1972.

Despite Can never visiting the United States, American musicians from the 1980s and 1990s alternative underground, such as Pavement’s Stephen Malkmus and the members of Sonic Youth, have declared Can’s influence on their music making. In 2012, as part of a celebration of the album’s fortieth anniversary celebrations, Malkmus performed Ege Bamyasi in full with Von Spar – appropriately a band that came from Cologne with a singer from elsewhere. Several post-rock musicians and even mainstream rock artists such as the Red Hot Chilli Peppers and Radiohead have paid their respects. Local musicians from the underground, post-punk, indie, and alternative rock tradition, alongside improvisers and electronic musicians, have typically made up the nightly changing ‘sound carriers’ that accompany Suzuki’s (almost) continual international tours since 1997.

The link between Can, other Krautrock artists, and the development of electronic music may be overplayed, considering the roots of electronic music can be drawn as far back as the 1920s and 1930s, but a certain form of ‘danceable’ electronic music has certainly taken cues. Simon Reynolds has argued that Can anticipated and inspired ‘dance genres like trip hop, ethno-techno and ambient jungle’.Footnote 27 On a local level, Hans Nieswandt has argued that they popularised electronic music in Cologne by bringing the approaches and sounds pioneered by Stockhausen to a wider public.Footnote 28 Rob Young has noted that the band’s legacy is kept intact by the Kompakt record label in Cologne, artists such as Mouse on Mars, and those involved with the Basic Channel/Chain Reaction/Rhythm and Sound labels in Berlin.Footnote 29 Can’s position as forerunners of ambient music has been recognised by their peers, not least Brian Eno. Furthermore, Can’s enticing beats and sounds have also been sampled by hip-hop producers. Kanye West, for instance, sampled ‘Sing Swan Song’ on his track ‘Drunk & Hot Girls’ (Graduation, 2007), on which he collaborated with Yasiin Bey (then known as Mos Def), and Q-Tip sampled ‘A Spectacle’ to create a backing for ‘Manwomanboogie’ (The Renaissance, 2008). There are few bands that could claim to have caught the ear of such diverse communities of musicians and compelled them to try to incorporate the sounds and approaches into their own work, with so many varied effects. To borrow a pun from Malcolm Mooney, it’s all about a ‘CAN DO’ attitude.

Essential Listening

Can, Monster Movie (Music Factory, 1969)

Can, Tago Mago (United Artists, 1971)

Can, Ege Bamyasi (United Artists, 1972)

Can, Future Days (United Artists, 1973)

Tangerine Dream has long held an exceptional dual status as one of the most popular and productive bands to have emerged from the Krautrock scenes of the 1970s. With over 100 live or studio albums and over 60 soundtracks to its name, the task of covering Tangerine Dream’s influence and legacy is formidable.Footnote 1 Initially part of the arts scene of West Berlin, the band were formed by Edgar Froese in 1967; their founding thus preceded the student revolutions by a year. However, Tangerine Dream’s musical productivity has been unceasing since then, moving far beyond the classic 1970s era of Krautrock. After a turbulent and experimental early period, the band managed by the late 1970s to attain heights of popular status that stretched from Hollywood films to world tours. With respect to Krautrock’s experimental aesthetics and countercultural ideals, this commercial success and the band’s resulting shifts in musical approach have repeatedly drawn criticism.Footnote 2 And yet, as an originator of the ‘Berlin School’ of electronic music, Tangerine Dream have garnered high praise and a devoted fan following to this day.

Froese remained the bandleader until his passing in 2015, leaving an extraordinary legacy in his solo work and as the driving force behind Tangerine Dream. The band have also continued to perform, curating Froese’s legacy as managed by Thorsten Quaeschning, with the guidance of Froese’s widow, Bianca Froese-Acquaye.Footnote 3 Still, given such productivity in terms of musical releases and media presence, a critical ambivalence regarding Tangerine Dream is practically unavoidable. A tension resides within Tangerine Dream between such distinctions as Krautrock and New Age, ambient and cosmic rock, synthwave and trance, and electronic live-act and soundtrack. Listening for that tension, whether in terms of cultural status, media, or musical style, can arguably be the most fruitful way of appreciating their achievements. The band’s influence on these genres and practices has resulted in a unique cultural constellation that other Krautrock bands did not touch in the same way – with the exception of Kraftwerk.

In this over-arching respect, this chapter provides an account of Tangerine Dream that expands beyond the traditional focus of the Krautrock 1970s. To be sure, Tangerine Dream made their most compelling leaps in audio experimentation and production during this time, with four classic albums released by Ohr between 1970 and 1973, followed by Phaedra (1974) and Rubycon (1975) with the band’s move to Virgin Records. We will first address Tangerine Dream’s musical transformation in the context of the 1970s. Our account then moves beyond this classic Krautrock study in the following respects. First, Tangerine Dream’s live career through the 1980s will be highlighted, involving multiple ground-breaking performances that had both geographic and political consequences: from iconic events at European cathedrals to concert spectacles across the United States, and landmark tours in the Eastern Bloc during the 1980s. A parallel tradition of live albums, inaugurated by the classic Ricochet (1975), demonstrates that the band maintained some of their better experimental traditions in the live context.

The final sections continue with this expanded frame by addressing Tangerine Dream’s legacy in music for visual media. Tangerine Dream’s numerous film scores, especially during the 1980s, have been as consequential as their live and studio albums. Far beyond a commercial footnote, this Hollywood career has helped to solidify the band’s legacy while reaching new audiences. Such a perspective, which highlights the 1980s as much as the 1970s, requires a leap beyond orthodoxies that focus primarily on the early albums as the band’s Golden Age. This original view was arguably cemented in Julian Cope’s landmark Krautrocksampler, where he focused almost exclusively on the early albums. Indeed, Cope even omitted Phaedra, long seen as a definitive album, from his list of the top 50 Krautrock albums. He finished with Atem from 1973Footnote 4 – although in fairness, he gave some praise for the later albums of the 1970s. Regardless, the critical tension between freeform Krautrock and the sequenced future of Tangerine Dream’s later albums is implied here.

To a certain extent, this desire to focus on early Tangerine Dream is related to the band’s overwhelming productivity, which is matched only by Conrad Schnitzler and Klaus Schulze, coincidentally the original members on the debut album from 1970.Footnote 5 Indeed, Tangerine Dream’s prolific discography can seem daunting, as though one is climbing a cosmic Mont Blanc. Reasonable concerns about a dilution of quality are also evident here. In this sense, if Kraftwerk achieved cult status on account of their minimalist approach, Tangerine Dream occupy the other extreme of abundant overload. And yet, this dive into discographic oceans of sound might also yield its own benefits, and not just for the most committed Tangerine Dream fans. While a canon of landmark albums exists for legitimate reasons, especially between 1972 and 1977 when the band established their definitive sound,Footnote 6 this wider discography should also be revisited. Some surprising outcomes can result, from the spectacle of live performances to a world of visual media.

The Ohr Years and kosmische Musik

This multi-decade career of Tangerine Dream was not foreseeable at the band’s inception. With their initial years in the late 1960s as part of the Zodiak club scene in West Berlin, involving related bands such as Ash Ra Tempel and Kluster, Tangerine Dream initially had a constant turnover of members – It was a feat that Edgar Froese managed to keep the band active. Still, practices of professionalisation and productivity were established for the band early on by Froese. He was older than the other band members, as he was born on D-Day in 1944. Froese grew up in West Berlin playing piano as a teenager and initially focusing on sculpture and painting. His talents eventually led to a brief period of study at the Academy of Arts in Berlin. He experienced the 1960s Beat era and toured with his first band, The Ones, which resulted in a life-changing experience. In Spain, Froese met Salvador Dali and was inspired to devote his artistic efforts to the experimental Berlin scene, with a kind of sonic surrealism that combined psychedelic rock and Dali.Footnote 7