Introduction

The Portuguese Pliocene marine fossil assemblage from the Mondego Basin, and the one from the Vale de Freixo site in particular, which is the sole Pliocene assemblage known between the Atlantic Guadalquivir Basin (southwestern Spain) and the Loir Basin (northwestern France), is key for understanding of biodiversity and biogeography of the northeastern marine Pliocene Franco-Iberian Atlantic mollusks (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Landau, Domènech and Martinell2006, Reference Silva, Landau, Domènech and Martinell2010; Silva and Landau, Reference Silva and Landau2007, Landau et al., Reference Landau, Silva, Van Dingenen and Ceulemans2020). The chiton paleobiodiversity from Vale de Freixo was initially studied by Dell'Angelo and Silva (Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003), who reported five species, including the endemic Ischnochiton zbyi Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003, based on the scant material then available. Prior to Dell'Angelo and Silva (Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003), the sole reference to the presence of Polyplacophora in the Pliocene of Portugal was that of Morais (Reference Morais1941), who reported Chaetopleura fulva (Wood, Reference Wood1815), a junior synonym of Chaetopleura angulata (Spengler, Reference Spengler1797), from the Pliocene of Marinha Grande (Fig.1).

Whereas the biogeography of Neogene northeastern Atlantic and Mediterranean gastropod mollusks has been extensively analyzed in the last three decades by several authors (e.g., Raffi and Monegatti, Reference Raffi and Monegatti1993; Monegatti and Raffi, Reference Monegatti and Raffi2007; Silva and Landau, Reference Silva and Landau2007; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Landau and La Perna2011; Vermeij, Reference Vermeij2012; Lozouet, Reference Lozouet2014; Ávila et al., Reference Ávila, Melo, Bernig, Cordeiro, Landau and Silva2016; Landau et al., Reference Landau, Silva, Van Dingenen and Ceulemans2020), the biogeography of northeastern Atlantic Polyplacophora has not been studied. In this paper, based on extensive new material, the chiton assemblage of Vale de Freixo is revisited, and new taxa are added to the Pliocene Atlantic fauna of western Iberia. Moreover, two new species of Atlantic Pliocene chitons are described. Based on the novel data obtained, an original approach to the Pliocene to present biogeographical evolution of the group in the northeastern Atlantic is presented and discussed.

Geological and paleoecological setting

Vale de Freixo is situated in central-west Portugal, near Pombal, 20 km east of the present-day coastline, with the geographical coordinates 39°53′02.1″N, 8°43′52.9″W (Fig. 1). The Neogene sequence exposed at this locality (Fig. 2) is part of the Cenozoic Mondego Basin, the fossiliferous Pliocene sediments corresponding to the basal beds of the Carnide Formation (Cachão, Reference Cachão1990; Diniz et al., Reference Diniz, Silva and Cachão2016). The calcareous nannofossil assemblage in them indicates placement in biozone CN12a of Okada and Bukry (Reference Okada and Bukry1980). Based on calcareous nannofossils and gastropods, these beds have been assigned to the uppermost Zanclean to lower Piacenzian (Cachão, Reference Cachão1990; Silva, Reference Silva2001; Diniz et al., Reference Diniz, Silva and Cachão2016). The marine molluscan assemblage of Vale de Freixo, as well as all the remaining marine Pliocene Atlantic assemblages of the Mondego Basin, correlate to the Mediterranean Pliocene Molluscan Unit 1 (MPMU1) of Monegatti and Raffi (Reference Monegatti and Raffi2001) for the Mediterranean (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Landau, Domènech and Martinell2010). For more information on the general geological setting and the stratigraphy of the Vale de Freixo site, as well as additional references, please refer to Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Landau, Domènech and Martinell2006, Reference Silva, Landau, Domènech and Martinell2010) and Diniz et al. (Reference Diniz, Silva and Cachão2016).

Figure 1. Location of the Pliocene Vale de Freixo site in the Pombal region of central-west Portugal.

Figure 2. Stratigraphic column of the Vale de Freixo Neogene section in the Pombal region of central-west Portugal.

During the very end of the Zanclean and the beginning of the Piacenzian, in times of global high sea level (Dowsett and Cronin, Reference Dowsett and Cronin1990; Chandan and Peltier, Reference Chandan and Peltier2017), the area of present-day Caldas da Rainha-Pombal region of western Portugal was inundated and partially occupied by shallow marine environments of normal salinity, somehow protected from direct influence of the open Atlantic Ocean (Nolf and Silva, Reference Nolf and Silva1997; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Landau, Domènech and Martinell2010). Based on the Pliocene gastropod assemblage, the mid-Pliocene Sea Surface Temperatures (SST) along the western Iberian coast at that latitude were subtropical, akin to those recorded today off western Africa at the latitude of Cape Blanc (northern Mauritania, 21° N), with maximum Mean Monthly SST (MSST) of ~23.5°C in September and minimum MMSST of 19°C in January–March (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Landau, Domènech and Martinell2010). The gastropod fauna was part of the Pliocene French-Iberian subtropical Province of Silva and Landau (Reference Silva and Landau2007) and Landau et al. (Reference Landau, Silva, Van Dingenen and Ceulemans2020).

The fossil assemblage of Vale de Feixo indicates a local infralittoral environment in which the gastropods were the most diverse molluscan group (Silva, Reference Silva2001, Reference Silva2002), followed by bivalves (Pimentel, Reference Pimentel2018) and polyplacophorans (Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003). Other benthic invertebrate groups (e.g., bryozoans [Carvalho, Reference Carvalho1961], echinoids [Silva, Reference Silva2001; Pereira, Reference Pereira2010], and barnacles [Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Pereira. and Silva2019]) were also well represented in the local ecosystem. In the assemblage the vertebrates are represented by bony fish otoliths and rare shark teeth (Nolf and Silva, Reference Nolf and Silva1997; Silva, Reference Silva2001). Frequent terrestrial plant remains—plant debris, poorly preserved pine needles, and the occasional small conifer cone—are also present in the assemblage, confirming the proximity to emerged land (Silva, Reference Silva2001). The palynoflora was studied by Diniz (Reference Diniz1984), Vieira et al. (Reference Vieira, Castro, Pais and Pereira2006), and Diniz et al. (Reference Diniz, Silva and Cachão2016).

Material and methods

The recent sampling of the Pliocene of Vale de Freixo (“bed 3” in Gili et al., Reference Gili, Silva and Martinell1995, and Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003) yielded 2088 chiton valves. In this extensive sample, seven genera and 12 species are represented, two of which are described as new. The new material herein discussed was obtained by means of search sampling under a binocular microscope from extensive wet sieving of ~500 kg of fine sandy sediment using a 1 mm mesh sieve, primarily intended for collecting microgastropod fossils. For comparison, for the Dell'Angelo and Silva (Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003) paper, 37 valves were collected from a 10 kg bulk sample using a 1 mm mesh sieve.

The maximum width (maximum left-right dimension perpendicular to the longitudinal body axis) of complete valves (head, intermediate, and tail, presented as: Maximum width: 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 mm) of each species is given, as well has the width/length ratio (W/L). The type materials of the new taxa, Ischnochiton loureiroi n. sp. and Lepidochitona rochae n. sp., were deposited in the Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Fossil Mollusca collection, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Usually, non-scientific circumstances are irrelevant when it comes to publishing paleontological works. Unfortunately, this is not the case here. This work was prepared at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020. Part of the material photographed was sent from the Netherlands to Italy by registered post. Regrettably, regardless of registration, part the material was lost in the chaos and the Dutch Post Office was unable to trace the material despite numerous attempts. Material lost was replaced in museum collections by similar specimens of the same species and locality. This unusual circumstance is explained on the museum label attached to each replacement specimen. Thankfully, all type material illustrated here is deposited safely at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center. In the text and in the plate captions, the figured lost specimens are identified as such and a replacement museum number is given for the substitute specimen.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Types, figured, and other specimens examined in this study are part of the following collections and/or deposited in the following institutions: Department of Geology of the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Lisbon, Portugal (GeoFCUL), Carlos Marques da Silva, Vale de Freixo (VFX) PhD Collection; The Linnean Society of London (LSL), London, UK; Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (MNHN), Paris, France; Museu Nacional de História Natural da Universidade de Lisboa (MNHN/UL), Lisbon, Portugal; Museo di Zoologia dell'Università di Bologna (MZB), Bologna, Italy; The Natural History Museum [formerly British Museum (Natural History)] (NHMUK), London, UK; Natural History Museum Wien (NHMW), Austria; Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Fossil Mollusca collection (RGM), Leiden, The Netherlands; Royal Scottish Museum of Natural History (RSMNH), Edinburgh, UK; United States National Museum of Natural History (USNM), Washington, D.C., USA; Zoologisches Museum an der Humboldt Universität (ZMHU), Berlin, Germany; Bruno Dell'Angelo Collection (BD), these specimens will be deposited in the Museo di Zoologia dell'Università di Bologna, Italy.

Systematic paleontology

In this paper, the taxonomy of Sirenko (Reference Sirenko2006) is followed. Many of the chiton species represented in the study assemblage are well known from Mediterranean Neogene deposits and have been previously illustrated and discussed in detail (e.g., Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo and Zavodnik2004, Reference Dell'Angelo, Garilli, Germanà, Reitano, Sosso and Bonfitto2012, Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013, Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2015, Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016, Reference Dell'Angelo, Lesport, Cluzaud and Sosso2018a, Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau, Van Dingenen and Ceulemansb, Reference Dell'Angelo, Lesport, Cluzaud and Sosso2020; Garilli et al., Reference Garilli, Dell'Angelo and Vardala-Theodorou2005). For these species, only a short chresonymy, some comments, and stratigraphic ranges are given. The geographic ranges and habitats of extant species were compiled based on Kaas and Van Belle (Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985a, Reference Kaas and Van Belleb, Reference Kaas and Van Belle1988, Reference Kaas and Van Belle1990, Reference Kaas and Van Belle1994), Dell'Angelo and Smriglio (Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999), and Kaas et al. (Reference Kaas, Van Belle and Strack2006).

Class Polyplacophora Gray, Reference Gray1821

Subclass Loricata Schumacher, Reference Schumacher1817

Order Lepidopleurida Thiele, Reference Thiele1909

Family Leptochitonidae Dall, Reference Dall1889

Genus Leptochiton Gray, Reference Gray1847

Type species

Chiton cinereus Montagu, Reference Montagu1803 (non Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1767, = Chiton asellus Gmelin, Reference Gmelin and Gmelin1791), by subsequent designation (Gray, Reference Gray1847).

Occurrence

Known from the Triassic of Italy, L. davolii (Laghi, Reference Laghi2005). Today, it has a worldwide distribution, being common in the northeastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea (Kaas and Van Belle, Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985a).

Leptochiton cancellatus (Sowerby, Reference Sowerby1840)

Figure 3.1–3.9

- Reference Sowerby1840

Chiton cancellatus Sowerby, figs. 104, 104a, b, 105.

- Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985a

Leptochiton (Leptochiton) cancellatus; Kaas and Van Belle, p. 43, fig. 16.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Palazzi1986

Leptochiton (Leptochiton) cancellatus; Dell'Angelo and Palazzi, p. 10, figs. 6–8, 41, 51, 65, 67, 69.

- Reference Cesari1987

Leptochiton (Leptochiton) cancellatus; Cesari, p. 6, pl. 1, figs. 1–7.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999

Lepidopleurus (Leptochiton) cancellatus; Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, p. 48, pl. 10, 11, figs. 18, 19.

- Reference Marquet2002

Lepidopleurus (Leptochiton) cancellatus; Marquet, p. 12, pl. 2, fig. 1.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003

Lepidopleurus (Leptochiton) cancellatus; Dell'Angelo and Silva, p. 9, figs. 3, 4.

- Reference Studencka and Dulai2010

Leptochiton cancellatus; Studencka and Dulai, p. 260, text-fig. 2A–D.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013

Leptochiton cancellatus; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 70, pl. 1, figs. N–T.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2015

Leptochiton cancellatus; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 226, pl. 3, figs. 1–6.

Figure 3. (1–9) Leptochiton cancellatus (Sowerby, Reference Sowerby1840) from the Carnide Formation, Pliocene, Portugal: (1–3) RGM.1363997, (1) head valve in dorsal, (2) ventral, and (3) lateral views; width 2.2 mm; (4–6) intermediate valve (4) in dorsal view, (5) close-up of ornamentation of central area, and (6) frontal view; width 3 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.349); (7–9) GeoFCUL VFX.03.339, (7) tail valve in dorsal, (8) ventral, and (9) lateral views; width 2.2 mm. (10–15) Leptochiton scabridus (Jeffreys, Reference Jeffreys1880) from the Carnide Formation, Pliocene, Portugal: (10–12) RGM.1363999, (10) head valve in dorsal view and (11, 12) close-up of ornamentation width 1.4 mm; (13–15) intermediate valve (13) in dorsal view, (14) close-up of ornamentation of central and lateral areas, and (15) frontal view; width 2.1 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.350). Scale bars = 0.5 mm (1–4, 6–10, 12, 13, 15), or 100 μm (5, 11, 14).

Holotype

Unknown, probably lost. Northeastern Atlantic, Great Britain, probably from Oban, Scotland (Kaas and Van Belle, Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985a).

Occurrence

Middle Miocene: Paratethys in Poland (Macioszczyk, Reference Macioszczyk1988; Studencka and Studencki, Reference Studencka and Studencki1988) and Ukraine (Studencka and Dulai, Reference Studencka and Dulai2010). Upper Miocene: Proto-Mediterranean in Italy, Po Basin (Tortonian, Dell'Angelo and Palazzi, Reference Dell'Angelo and Palazzi1989; Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2015). Lower Pliocene: North Sea Basin in Belgium (Marquet, Reference Marquet1984, Reference Marquet2002); Mediterranean, Italy, Liguria (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013), Tuscany (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Forli and Lombardi2001; Chirli, Reference Chirli2004). Lower to Upper Pliocene: northeastern Atlantic in Portugal, Mondego Basin (MPMU1, Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003); Mediterranean in Italy, Sicilia (MPMU1, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Garilli, Germanà, Reitano, Sosso and Bonfitto2012). Pleistocene: North Atlantic in Sweden and Norway (Brogger, Reference Brogger1901; Antevs, Reference Antevs1917); Mediterranean in Italy, Calabria, and Sicilia (BD unpublished data). Present: Atlantic Ocean, from Great Britain and Ireland (Light and Baxter, Reference Light and Baxter1990) to France, Spain, Portugal, and Madeira archipelago (Kaas, Reference Kaas1979; Rolán Mosquera et al., Reference Rolán Mosquera, Otero-Schmitt and Rolán Álvarez1990; Macedo et al., Reference Macedo, Macedo and Borges1999; Segers et al., Reference Segers, Swinnen and De Prins2009; Urgorri et al., Reference Urgorri, Díaz-Agras, García-Álvarez, Señarís and Banón2017); Mediterranean Sea in Spain (Moreno and Gofas, Reference Moreno and Gofas2011), Italy (Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999), Malta, Greece; and Aegean Sea (Mifsud et al., Reference Mifsud, Cachia and Sammut1990; Zenetos and Van Aartsen, Reference Zenetos and Van Aartsen1995; Koukouras and Karachle, Reference Koukouras and Karachle2005), Turkey (Öztürk et al., Reference Öztürk, Doğan, Bitlis-Bakir and Salman2014), Tunisia (Cecalupo et al., Reference Cecalupo, Buzzurro and Mariani2008), and Israel (Barash and Danin, Reference Barash and Danin1977).

Materials

265 valves (37 head, 159 intermediate and 69 tail). One intermediate valve lost (Fig. 3.4–3.6) and replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.349, RGM.1363997 (1 valve) (Fig. 3.1–3.3), GeoFCUL VFX.03.339 (1 valve) (Fig. 3.7–3.9), RGM.1363998 (40 valves), GeoFCUL VFX.03.346 (40 valves), MNHN.F.A81981 (40 valves), BD 237 (142 valves). Maximum width: 2.5 | 3.2 | 3.8 mm.

Remarks

This species is characterized by having rounded intermediate valves, and the tegmentum sculptured with very dense granules arranged in radial series on the head valve, the lateral areas of the intermediate valves, and the postmucronal area of the tail valve, in longitudinal series on the central area of the intermediate valves, and the antemucronal area of the tail valve, with reduced intercostal spaces. Detailed description and discussion of L. cancellatus were given by Kaas and Van Belle (Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985a) and Dell'Angelo and Smriglio (Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999).

Dell'Angelo and Silva (Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003) reported two valves (one intermediate and one tail) from Vale de Freixo. In the material now available, there are hundreds of small and fragile valves, most of which are incomplete and poorly preserved. The shape and the sculpture of the valves are consistent with the diagnostic characters of this species.

The Middle Miocene (lower Badenian) Paratethys (Korytnica, Poland) specimens assigned to Leptochiton sulci (Bałuk, Reference Bałuk1971) were considered conspecific with L. cancellatus by Laghi (Reference Laghi1977), Dell'Angelo and Palazzi (Reference Dell'Angelo and Palazzi1989), Dell'Angelo and Smriglio (Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999), and Dell'Angelo and Silva (Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003). However, as reported by Dell'Angelo et al. (Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013), these Paratethian specimens represent a distinct species, following Bałuk (Reference Bałuk1971, Reference Bałuk1984) and Studencka and Dulai (Reference Studencka and Dulai2010).

Leptochiton cancellatus was reported from Scandinavian coasts and from the northern Pacific (Kaas and Van Belle, Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985a). However, the European records were assigned by Kaas (Reference Kaas1981) to L. sarsi Kaas, Reference Kaas1981, occurring from the Swedish coasts of the Skagerrak arm of the North Sea (Bohuslän) to Finmark in northern Norway (Kaas, Reference Kaas1981). Ferreira (Reference Ferreira1979) recognized two separate species on the west coast of North America: L. rugatus (Carpenter in Pilsbry, Reference Pilsbry and Tryon1892), restricted to California and Mexico, and the northern ‘L. cancellatus.’ The Pacific specimens of ‘L. cancellatus’ have been assigned to a recently described northeastern Atlantic species, L. cascadiensis Sigwart and Chen, Reference Sigwart and Chen2018, occurring along the coasts of North America, from Oregon to Alaska (Sigwart and Chen, Reference Sigwart and Chen2018).

Leptochiton scabridus (Jeffreys, Reference Jeffreys1880)

Figure 3.10–3.15

- Reference Jeffreys1880

Chiton scabridus Jeffreys, p. 33.

- Reference Sykes1894

Lepidopleurus scabridus; Sykes, p. 35, pl. 3, figs. 4, 7.

- Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985a

Leptochiton (Leptochiton) scabridus; Kaas and Van Belle, p. 49, fig. 19.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Palazzi1986

Leptochiton (Leptochiton) scabridus; Dell'Angelo and Palazzi, p. 11, figs. 11–14, 19–22, 32–34, 45–48, 54, 55, 60.

- Reference Cesari1987

Leptochiton (Leptochiton) scabridus; Cesari, p. 7, pl. 2, figs. 1–8, pl. 3, figs. 1–10, pl. 4, figs. 1–6, pl. 5, figs. 1–11, pl. 11, figs. 4–6.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Palazzi1989

Lepidopleurus (Leptochiton) scabridus; Dell'Angelo and Palazzi, p. 65, pl. 16, 17.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999

Lepidopleurus (Leptochiton) scabridus; Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, p. 63, pl. 16, 17, figs. 25, 26.

- Reference Garilli, Dell'Angelo and Vardala-Theodorou2005

Lepidopleurus (Leptochiton) scabridus; Garilli et al., p. 130, pl. 2, figs. 1–4.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013

Leptochiton scabridus; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 71, pl. 2, figs. E–G.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2015

Leptochiton scabridus; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 226, pl. 3, figs. 7–11.

Holotype

Unknown, probably lost.

Syntypes

Known type material, syntypes: one specimen (USNM 177391) from Goodrington, Torbay (England); 15 specimens (USNM 177392) from Jersey (Channel Islands) (Warén, Reference Warén1980).

Occurrence

Upper Miocene: Proto-Mediterranean Sea in Italy, Po Basin (Tortonian, Dell'Angelo and Palazzi, Reference Dell'Angelo and Palazzi1989; Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2015). Lower Pliocene: central Mediterranean in Italy (Dell'Angelo and Palazzi, Reference Dell'Angelo and Palazzi1989; Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013). Lower to Upper Pliocene: northeastern Atlantic in Portugal, Mondego Basin (MPMU1, Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003). Middle to Upper Pleistocene: central Mediterranean in Greece (Garilli et al., Reference Garilli, Dell'Angelo and Vardala-Theodorou2005). Present: Atlantic Ocean from southwestern Great Britain and the English Channel (Light and Baxter, Reference Light and Baxter1990) to France, Bretagne (Van Belle, Reference Van Belle1972), northern Spain (Urgorri et al., Reference Urgorri, Díaz-Agras, García-Álvarez, Señarís and Banón2017), Portugal (Macedo et al., Reference Macedo, Macedo and Borges1999), Canary Islands (Hernández and Rolán, Reference Hernández, Rolán and Rolán2011), Cape Verde Islands (Kaas, Reference Kaas1991), and Angola (Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999); Mediterranean Sea in Italy (Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999), Greece and Aegean Sea islands (Strack, Reference Strack1988; Koukouras and Karachle, Reference Koukouras and Karachle2005), Malta (Mifsud et al., Reference Mifsud, Cachia and Sammut1990), and Turkey (Öztürk et al., Reference Öztürk, Doğan, Bitlis-Bakir and Salman2014).

Materials

Fourteen valves (1 head, 10 intermediate and 3 tail): one intermediate valve lost (Fig. 3.13–3.15) and replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.350, RGM.1363999 (1 valve) (Fig. 3.10–3.12), RGM.1364000 (1 valve), GeoFCUL VFX.03.333 (1 valve), MNHN.F.A81982 (1 valve), BD 238 (9 valves). Maximum width: 1.4 | 3.7 | 2 mm.

Remarks

Detailed descriptions and discussion of specimens of this species were given by Kaas and Van Belle (Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985a) and Dell'Angelo and Smriglio (Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999). The tegmentum surface is rough, the sculpture granules are extended into a body that usually is formed by two or three longitudinal varices that merge into one along the external margin of the valve (Dell'Angelo and Palazzi, Reference Dell'Angelo and Palazzi1986, fig. 34; Garilli et al., Reference Garilli, Dell'Angelo and Vardala-Theodorou2005, pl. 2, figs. 2, 4). This characteristic feature is well preserved in the study material.

Family Hanleyidae Bergenhayn, Reference Bergenhayn1955

Genus Hanleya Gray, Reference Gray1857

Type species

Hanleya debilis Gray, Reference Gray1857 (= Chiton hanleyi Bean in Thorpe, Reference Thorpe1844), by monotypy.

Occurrence

Known from the Lower Oligocene to present. Today, it is represented by H. hanleyi (Bean in Thorpe, Reference Thorpe1844), occurring in the northern and central Atlantic and the Mediterranean, and by H. mediterranea Sirenko, Reference Sirenko2014, circumscribed to the Mediterranean Sea (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2015, Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau, Van Dingenen and Ceulemans2018b, Reference Dell'Angelo, Renda, Sirenko, Sosso and Giacobbe2021; Sirenko et al., Reference Sirenko, Sigwart and Dell'Angelo2016).

Hanleya hanleyi (Bean in Thorpe, Reference Thorpe1844)

Figure 4

- Reference Thorpe1844

Chiton hanleyi Bean in Thorpe, p. 263, fig. 57.

- Reference Lovén1846

Chiton nagelfar Lovén, p. 158.

- Reference Malatesta1962

Hanleya hanleyi; Malatesta, p. 153, figs. 9, 10.

- Reference Laghi1977

Hanleya hanleyi; Laghi, p. 99, figs. 5–9.

- Reference Marquet1984

Hanleya hanleyi; Marquet, p. 336, pl. 1, fig. 3.

- Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985a

Hanleya hanleyi; Kaas and Van Belle, p. 193, fig. 91, map 18.

- Reference Bellomo and Sabelli1995

Hanleya nagelfar; Bellomo and Sabelli, p. 201, text-fig. 1.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Giusti1997

Hanleya hanleyi; Dell'Angelo and Giusti, p. 51, fig. 2.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Lombardi and Taviani1998

Hanleya nagelfar; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 244, pl. 1, fig. 10.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999

Hanleya hanleyi; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 262, pl. 1, fig. 1 (part).

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999

Hanleya hanleyi; Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, p. 85, pl. 25–26, figs. 34–36 (part).

- Reference Marquet2002

Hanleya hanleyi; Marquet, p. 13, pl. 2, fig. 2.

- Reference Sirenko2014

Hanleya nagelfar; Sirenko, p. 2931, figs. 9–19.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2015

Hanleya nagelfar; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 231, pl. 4, figs. 10–12.

- Reference Sirenko, Sigwart and Dell'Angelo2016

Hanleya hanleyi; Sirenko et al., p. 58, figs. 1–10.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau, Van Dingenen and Ceulemans2018b

Hanleya hanleyi; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 20, fig. 10.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Renda, Sirenko, Sosso and Giacobbe2021

Hanleya hanleyi; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 125, fig. 1.

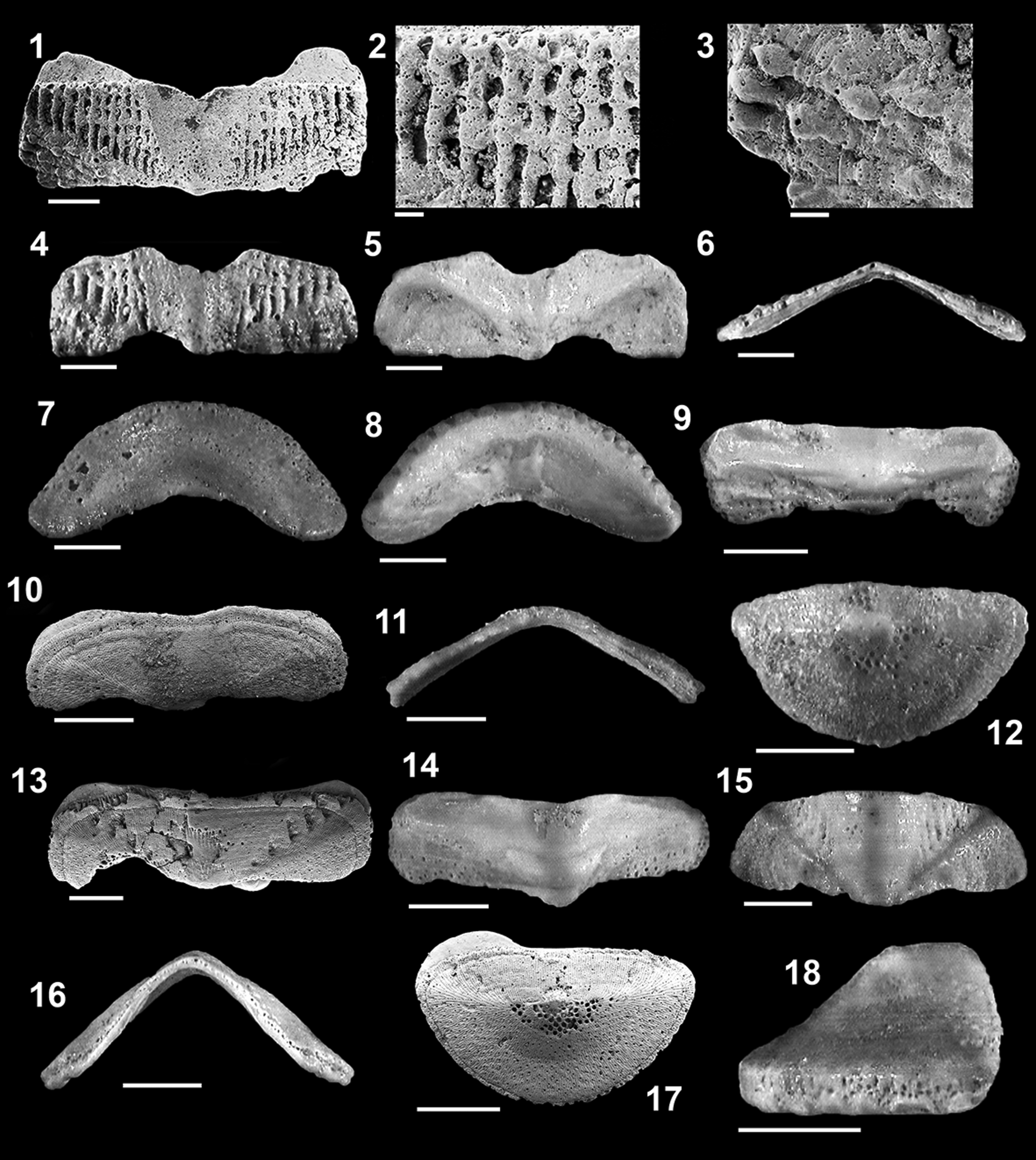

Figure 4. Hanleya hanleyi (Bean in Thorpe, Reference Thorpe1844) from the Carnide Formation, Pliocene, Portugal: (1–4) RGM.1364001, (1) intermediate valve in dorsal view, (2) close-up of ornamentation of central area, (3) ventral, and (4) frontal view; width 2.4 mm; (5, 6) GeoFCUL VFX.03.364, intermediate valve (5) in dorsal and (6) frontal views; width 2 mm. Scale bars = 0.5 mm (1, 3–6), or 100 μm (2).

Holotype

Scarborough Museums Trust, Scarborough, England (Sirenko et al., Reference Sirenko, Sigwart and Dell'Angelo2016).

Occurrence

Upper Miocene: northeastern Atlantic in France (Tortonian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau, Van Dingenen and Ceulemans2018b). Proto-Mediterranean Sea in Italy, Po Basin (Tortonian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999, Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2015). Lower to Upper Pliocene: northeastern Atlantic in England (Wood, Reference Wood1848; Reid, Reference Reid1890), Belgium (Marquet, Reference Marquet1984, Reference Marquet2002), Portugal, Mondego Basin (MPMU1, this paper); central Mediterranean in Italy, Liguria (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013). Upper Pliocene to Lower Pleistocene: northeastern Atlantic in France, Anjou (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau, Van Dingenen and Ceulemans2018b). Pleistocene: central Mediterranean in Italy (questionable, many reports in need of revision). Present: Atlantic Ocean from southern Greenland (Hansson, Reference Hansson1998; Sneli and Gudmundsson, Reference Sneli and Gudmundsson2018) to North America, Europe (Kaas, Reference Kaas1979; McKay and Smith, Reference McKay and Smith1979; Macedo et al., Reference Macedo, Macedo and Borges1999; Urgorri et al., Reference Urgorri, Díaz-Agras, García-Álvarez, Señarís and Banón2017), Madeira (Kaas, Reference Kaas1991; Segers et al., Reference Segers, Swinnen and De Prins2009), the Canary Islands (Kaas, Reference Kaas1991; Hernández and Rolán, Reference Hernández, Rolán and Rolán2011), and northern Africa; Mediterranean Sea in Italy (Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999), Aegean Sea islands (Zenetos and Van Aartsen, Reference Zenetos and Van Aartsen1995), and Turkey (Öztürk et al., Reference Öztürk, Doğan, Bitlis-Bakir and Salman2014).

Materials

Two intermediate valves, RGM.1364001 (Fig. 4.1–4.4), and GeoFCUL VFX.03.364 (Fig. 4.5, 4.6). Maximum width: 2.4 mm.

Remarks

Detailed descriptions and discussion of specimens of this species were given by Kaas and Van Belle (Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985a) and Sirenko et al. (Reference Sirenko, Sigwart and Dell'Angelo2016). This species has an intricate taxonomic history, with several accepted synonyms (Sirenko et al., Reference Sirenko, Sigwart and Dell'Angelo2016). Recently, H. mediterranea Sirenko, Reference Sirenko2014, has been described from the Mediterranean Sea. Hanleya hanleyi is characterized by the sculpture of pleural areas of intermediate valves and antemucronal area of the tail valve consisting of longitudinal series of small, roundish to oval granules, while H. mediterranea is distinguished by the lack of longitudinal series of granules across the entire pleural area, and by the presence of large granules comprising two or more small granules. Both species are represented in the Italian Neogene fossil record, sometimes occurring simultaneously, as in the Upper Miocene of Borelli (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2015). Hanleya was not reported by Dell'Angelo and Silva (Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003), being an addition to the Pliocene chiton biodiversity of western Iberia.

Order Chitonida Thiele, Reference Thiele1909

Suborder Chitonina Thiele, Reference Thiele1909

Superfamily Chitonoidea Rafinesque, Reference Rafinesque1815

Family Ischnochitonidae Dall, Reference Dall1889

Genus Ischnochiton Gray, Reference Gray1847

Type species

Chiton textilis Gray, Reference Gray1828, by subsequent designation (Gray, Reference Gray1847).

Occurrence

Known from Eocene to present. Today it has a worldwide distribution, except for the northern Atlantic and Arctic oceans (Kaas and Van Belle, Reference Kaas and Van Belle1990).

Ischnochiton zbyi Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003

Figures 5, 6

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003

Ischnochiton zbyi Dell'Angelo and Silva, p. 10, figs. 5–11.

- Reference Schwabe2005

Ischnochiton zbyi; Schwabe Reference Schwabe2005, p. 105.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Garilli, Germanà, Reitano, Sosso and Bonfitto2012

Ischnochiton zbyi; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 60.

- Reference Cherns and Schwabe2019

Ischnochiton zbyi; Cherns and Schwabe, p. 688.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso and Bonfitto2019

Ischnochiton zbyi; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 48.

Paratypes

MNHN/UL.II.407-408 (head valve, width 3.4 mm, Fig. 5.3, 5.4, and tail valve, width 3.6 mm, Fig. 5.5, 5.6); MZB 12692 (3 valves); BD (3 valves); GeoFCUL VFX.03.312-332 (21 valves). Vale de Freixo, near the village of Carnide, Pombal municipality, central-west Portugal (Fig. 1). Pliocene, upper Zanclean to lower Piacenzian, Carnide Formation, basal fossiliferous gray sands, “Bed 3” in Gili et al. (Reference Gili, Silva and Martinell1995), Dell'Angelo and Silva (Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003), and herein (Fig. 2). Equivalent to the Mediterranean MPMU1 of Monegatti and Raffi (Reference Monegatti and Raffi2001).

Occurrence

Pliocene: northeastern Atlantic in Portugal, Mondego Basin (MPMU1, Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003; this paper).

Revised description

Head valve semi-circular, posterior margin widely V-shaped, notched in middle, slope straight to slightly concave; tegmentum with microgranulose sculpture showing random roundish/squarish granules up to 30–40 μm, with 3–5 aesthetes of equal size on surface, and 19–24 granulose radiating ribs, not starting from apex, but from mid-valve, concentrically crossed by numerous growth lines, some ribs splitting towards anterior margin, ribs formed by larger granules (up to 100 μm, with 10–15 or more aesthetes of equal size), with microgranules present in all rib interspaces, surface between microgranules rough.

Intermediate valves broadly rectangular, three times wider than long or more (W/L = 3.0–3.5), moderately elevated (H/W = 026–0.36), anterior profile carinate, anterior margin straight, slightly concave in jugum, side margins straight to slightly rounded, posterior margin straight, with apex not evident, lateral areas moderately elevated, with microgranulose sculpture and 2–8 radiating granulose ribs starting from apex, with microgranules always present between ribs and structure of granules same as head valve, pleural areas with longitudinal granulose ribs (10–26 on either side), with granules coalescent forming uninterrupted ribs, interstices narrower than ribs with subobsolete microgranulose sculpture, jugal area triangular with longitudinal striae converging towards center on both sides in wider valves, forming larger, irregular granules; not arranged in longitudinal striae in smaller valves.

Tail valve depressed, wider than long (W/L = 1.9–2.1), anterior margin straight or slightly concave in jugal tract, mucro subcentral, slightly raised; antemucronal slope straight, postmucronal slope slightly concave directly behind mucro, antemucronal area sculptured like central area of intermediate valves, postmucronal area sculptured like head valve.

Articulamentum whitish, apophyses wide, triangular in intermediate valves, trapezoidal in tail valve, jugal sinus narrow, slit formula 10–11/1/7–11, slits inequidistant.

Materials

Type material and 505 valves (100 head, 346 intermediate and 59 tail): Four valves lost (Figs. 5.7–5.10, 6.1–6.3, 6.9, 6.10–6.12) and replaced by specimens GeoFCUL VFX.03.351–354, RGM.1364002–1364005 (Figs. 5.11, 5.12, 5.16–5.18, 6.4, 6.5, 6.6), GeoFCUL VFX.03.334, VFX.03.335 (Figs. 5.13, 5.14, 6.7), MNHN.F.A81983, MNHN.F.A81984 (Figs. 5.15, 6.8), RGM.1364006 (50 valves), GeoFCUL VFX.03.336 (50 valves), MNHN.F.A81985 (50 valves), BD 240 (343 valves). Maximum width: 5.8 | 6.5 | 4.3 mm.

Figure 5. Ischnochiton zbyi Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003 from the Carnide Formation, Pliocene, Portugal: (1, 2) holotype, MNHN/UL.II.406, (1) intermediate valve in dorsal view and (2) close-up of ornamentation of longitudinal ribs; width 5.8 mm (Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003, figs. 5, 6); (3, 4) paratype, MNHN/UL.II.407, (3) head valve in dorsal view and (4) close–up of ornamentation; width 3.4 mm (Dell'Angelo and Silva, 2003, figs. 7, 8); (5, 6) paratype MNHN/UL.II.408, (5) tail valve in dorsal and (6) lateral views; width 3.6 mm (Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003, figs. 9, 10); (7–10) head valve (7) in dorsal view, (8) close-up of ornamentation of microgranules and granules, (9) close-up of radiating ribs, and (10) ventral view; width 3.6 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.351); (11, 12) RGM.1364002, (11) intermediate valve in dorsal view and (12) close–up of ornamentation of jugal area; width 6.5 mm; (13, 14) GeoFCUL VFX.03.334, intermediate valve (13) in dorsal and (14) frontal views; width 4.4 mm; (15) MNHN.F.A81983, intermediate valve in dorsal view; width 3.6 mm; (16–18) RGM.1364003, tail valve in (16) dorsal, (17) ventral, and (18) lateral views; width 4.2 mm. Scale bars = 0.5 mm (1, 3, 5–7, 10–18), or 100 μm (2, 4, 8, 9).

Figure 6. Ischnochiton zbyi Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003, from the Carnide Formation, Pliocene, Portugal: (1–3) intermediate valve (1) in dorsal view, (2) close-up of ornamentation, and (3) ventral view; width 3.1 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.352); (4) RGM.1364004, intermediate valve in dorsal view; width 1.7 mm (estimated width just over 3 mm); (5, 6) RGM.1364005, intermediate valve in (5) dorsal and (6) frontal views; width 2.6 mm; (7) GeoFCUL VFX.03.335, intermediate valve in dorsal view; width 3.2 mm; (8) MNHN.F.A81984, intermediate valve in dorsal view; width 2.5 mm; (9) intermediate valve (estimated width ~2.5 mm), dorsal view; width 1.2 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.353); (10–12) tail valve (10) in dorsal view, (11) close-up of ornamentation of longitudinal ribs of antemucronal area, and (12) microgranules of postmucronal area; width 3 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.354). Scale bars = 0.5 mm (1, 3–10), or 100 μm (2, 11, 12).

Remarks

We provide a revised description of I. zbyi, because the abundant material now at hand, representing the complete growth series from juvenile to adult, allows a more detailed description of some shell features and a better understanding of intraspecific variability. The number of granulose ribs in the lateral areas of the intermediate valves is variable, from 5–8 in the larger valves (Fig. 5.11, 5.13) to 2–3 in smaller valves (Fig. 6.1, 6.4, 6.5, 6.7, 6.9), with microgranules always present in the rib interspaces. The number of longitudinal ribs in the pleural areas of the intermediate valves is also variable, from 22–26 on either side in the larger valves (Fig. 5.11, 5.13) to 10–15 in juveniles (e.g., 12 in Fig. 6.1).

Taken individually, the intermediate valves shown in Figures 5 and 6 (shown sequentially in decreasing width to illustrate valve variability) could give the impression of belonging to two distinct species, but the intraspecific variability in I. zbyi is very high and the variations occur continuously without clear separation between the characters examined.

Ischnochiton loureiroi new species

Figure 7.1–7.6

Holotype

Holotype RGM.1364007, intermediate valve (Fig. 7.1–7.3).

Figure 7. (1–6) Ischnochiton loureiroi n. sp. from the Carnide Formation, Pliocene, Portugal: (1–3) holotype, RGM.1364007, intermediate valve (1) in dorsal view and (2) close-up of ornamentation of central and (3) lateral area; width 3.4 mm; (4–6) paratype, RGM.1364008, intermediate valve in (4) dorsal, (5) ventral, and (6) frontal views; width 2.4 mm. (7–12) Callochiton septemvalvis (Montagu, Reference Montagu1803) from the Carnide Formation, Pliocene, Portugal: (7, 8) RGM.1364009, head valve in (7) dorsal and (8) ventral views; width 2.3 mm; (9) RGM.1364010, intermediate valve in dorsal view; width 1.9 mm; (10, 11) intermediate valve in (10) dorsal and (11) frontal views; width 2 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.355); (12) GeoFCUL VFX.03.337, tail valve in dorsal view; width 1.5 mm. (13–18) Callochiton doriae (Capellini, Reference Capellini1859) from the Carnide Formation, Pliocene, Portugal: (13) intermediate valve in dorsal view; width 3 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.356); (14) RGM.1364012, intermediate valve in ventral view; width 2 mm; (15, 16) GeoFCUL VFX.03.340, intermediate valve in (15) dorsal and (16) frontal views; width 2 mm; (17, 18) tail valve in (17) dorsal and (18) lateral views; width 1.7 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.357). Scale bars = 0.5 mm (1, 4–18), or 100 μm (2, 3).

Paratype

Paratype RGM.1364008, intermediate valve (Fig. 7.4–7.6). Maximum width: 3.4 mm. Vale de Freixo site, near the village of Carnide, Pombal municipality, central-west Portugal (Fig. 1). Pliocene, upper Zanclean to lower Piacenzian, Carnide Formation, basal fossiliferous gray sands, “Bed 3” in Gili et al. (Reference Gili, Silva and Martinell1995), Dell'Angelo and Silva (Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003), and herein (Fig. 2). Equivalent to the Mediterranean MPMU1 of Monegatti and Raffi (Reference Monegatti and Raffi2001).

Diagnosis

Intermediate valves broadly rectangular, elongated, slightly elevated, carinate, posterior margin straight with prominent apex, lateral areas poorly elevated, with microgranulose sculpture and three radiating irregular granulose ribs, with scattered elevated granules irregularly distributed on striae, pleural areas with longitudinal irregular granulose ribs (9–11 on either side), interstices smooth, large smooth triangular jugal area, weak growth lines. Articulamentum with large, triangular apophyses, insertion plate short with a single slit.

Occurrence

Pliocene: northeastern Atlantic in Portugal, Mondego Basin (MPMU1, this paper).

Description

Intermediate valves broadly rectangular, width four times length or a little less, slightly elevated (H/W = 0.20–0.24), anterior profile carinate, anterior margin straight, side margins rounded, posterior margin straight on both sides of prominent apex, lateral areas poorly elevated, sharply delimited, with microgranulose sculpture and three radiating irregular granulose ribs originating at apex, some ribs splitting towards anterior margin, with scattered elevated granules irregularly distributed on striae, pleural areas with longitudinal irregular granulose ribs (9–11 on either side), with granules coalescent forming uninterrupted ribs, interstices smooth, equal in width to ribs, ribs not reaching anterior margin in jugal area, large smooth triangular jugal area, weak growth lines.

Articulamentum with large, triangular apophyses, insertion plate short with a single slit, slit rays scarcely visible.

Etymology

Named after João de Loureiro (1717–1791), a Portuguese Jesuit missionary in the Far East and botanist, author of the “Flora Cochinchinensis.” He published what is considered the first Portuguese paleontological paper on “a kind of animal petrification,” discussing petrified crabs from present-day Vietnam (Loureiro, Reference Loureiro1799). According to the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) norm, the word loureiro (meaning laurel tree in Portuguese, also a surname) is pronounced /low.'ɾɐj.ɾu/.

Other materials

One intermediate valve, width 2.7 mm (specimen lost).

Paleoecology

Epibenthic vagile mollusks living in coastal, infralittoral, subtropical marine environments (estimated maximum mean monthly SST, MMSST, of ~23.5°C in September and minimum MMSST of 19°C in January–March; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Landau, Domènech and Martinell2010) of normal salinity and sand-pebble shelly substrates.

Remarks

The material at hand is quite worn and some morphological features are not preserved, but the sculpture of the valves is different from that of any other Ischnochiton species known from the European Neogene and distinct enough to warrant description as a new species. Ischnochiton loureiroi n. sp. (Fig. 7.1) markedly differs from I. zbyi (Figs. 5.11, 6.1) by the shape of the intermediate valves, being more elongated (width about four times the length or slightly less, versus W/L = 3.0–3.5 in I. zbyi) and less elevated (H/W = 0.20–0.24 versus 0.26–0.36 in I. zbyi), the different sculpture of the central area (9–11 very irregular granulose ribs on both sides and a large smooth triangular jugal area versus 10–26 granulose ribs and a striated jugal area in I. zbyi) and the lateral areas of the valves (three radiating irregular granulose ribs with some elevated granules irregularly distributed on striae versus 2–8 in I. zbyi).

Family Callochitonidae Plate, Reference Plate1901

Genus Callochiton Gray, Reference Gray1847

Type species

Chiton laevis Montagu, Reference Montagu1803, non Pennant, Reference Pennant1777 [= Callochiton septemvalvis (Montagu, Reference Montagu1803)], by subsequent designation (Gray, Reference Gray1847).

Occurrence

Known from lower Oligocene to present. Today it occurs in the Indo-Pacific (including Japan, but is absent from the northeastern Pacific) and in the eastern and sub-Antarctic Atlantic Ocean (Kaas and Van Belle, Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985b).

Callochiton septemvalvis (Montagu, Reference Montagu1803)

Figure 7.7–7.12

- Reference Montagu1803

Chiton laevis Montagu, p. 2 (non Pennant, Reference Pennant1777).

- Reference Montagu1803

Chiton septemvalvis Montagu, p. 3.

- Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985b

Callochiton septemvalvis septemvalvis; Kaas and Van Belle, p. 11, fig. 2.1, 2.4–2.6, 2.8–2.15, part (non fig. 2.2, 2.3, 2.7 = Callochiton doriae).

- non Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999

Callochiton septemvalvis (non Montagu); Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, p. 125, pl. 40, figs. A–H, pl. 41 figs. I–P, color figs. 61–63 (= Callochiton doriae).

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003

Callochiton septemvalvis; Dell'Angelo and Silva, p. 11, part (only one of the two intermediate valves).

- non Reference Dell'Angelo, Garilli, Germanà, Reitano, Sosso and Bonfitto2012

Callochiton septemvalvis (non Montagu); Dell'Angelo et al., p. 60, fig. 4L (= Callochiton doriae).

- non Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013

Callochiton septemvalvis (non Montagu); Dell'Angelo et al., p. 83, pl. 5, figs. N–P (= Callochiton doriae).

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016

Callochiton septemvalvis; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 73, pl. 1, figs. 1–4.

Holotype

Holotype NHMUK (Kaas and Van Belle, Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985b). Northeastern Atlantic, English Channel, Salcomb Bay, Great Britain.

Occurrence

Upper Miocene: Proto-Mediterranean Sea in Italy, Po Basin, (Tortonian, Laghi, Reference Laghi1977; Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016). Lower to Upper Pliocene: northeastern Atlantic in Portugal, Mondego Basin (MPMU1, Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003); western Mediterranean in Spain, Estepona Basin (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau and Marquet2004). Upper Pliocene to Lower Pleistocene: Mediterranean in Greece, Rhodes (Koskeridou et al., Reference Koskeridou, Vardala-Theodorou and Moissette2009). Pleistocene: North Atlantic in Sweden and Norway (Brogger, Reference Brogger1901; Antevs, Reference Antevs1917, Reference Antevs1928). Present: northeastern Atlantic, from northern Norway (Dons, Reference Dons1934; Hansson, Reference Hansson1998) to the Iberian Peninsula (McKay and Smith, Reference McKay and Smith1979; Rolán Mosquera et al., Reference Rolán Mosquera, Otero-Schmitt and Rolán Álvarez1990; Macedo et al., Reference Macedo, Macedo and Borges1999; Urgorri et al., Reference Urgorri, Díaz-Agras, García-Álvarez, Señarís and Banón2017) and the Canary Islands (Hernández and Rolán, Reference Hernández, Rolán and Rolán2011; Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999).

Materials

269 valves (216 intermediate and 53 tail): one intermediate valve lost (Fig. 7.10, 7.11) and replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.355, RGM.1364009, 1364010 (2 valves) (Fig. 7.7–7.9), GeoFCUL VFX.03.337 (Fig. 7.12), RGM.1364011 (30 valves), GeoFCUL VFX.03.338 (30 valves), MNHN.F.A81986 (30 valves), BD 241 (175 valves). Maximum width: 2.3 | 2.8 | 1.5 mm.

Remarks

Detailed description and discussion of C. septemvalvis was given by Kaas and Van Belle (Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985b). Its complicated taxonomic history was discussed by Dell'Angelo and Smriglio (Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999) and Dell'Angelo et al. (Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016, Reference Dell'Angelo, Renda, Sosso, Sigwart and Giacobbe2017). Herein, following Dell'Angelo et al. (Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016, Reference Dell'Angelo, Renda, Sosso, Sigwart and Giacobbe2017), Callochiton valves without longitudinal grooves on the pleural areas are assigned to Callochiton septemvalvis, and the ones with longitudinal grooves to Callochiton doriae (Capellini, Reference Capellini1859).

The material at hand consists of small, incomplete, and abraded valves, in which diagnostic characters are often difficult to discern (e.g., the incisions in the articulamentum), sometimes making specific attribution (to C. septemvalvis or C. doriae) difficult, particularly for the head valves. That is why head valves were not included in the study material.

Callochiton doriae (Capellini, Reference Capellini1859)

Figure 7.13–7.18

- Reference Costa1829

Chiton euplaeae O.-G. Costa, p. i, iv, pl. 1, fig. 3 (nomen dubium).

- Reference Capellini1859

Chiton doriae Capellini, p. 325, pl. 12, fig. 2.

- Reference Monterosato1879

Chiton laevis var. doriae; Monterosato, p. 26.

- Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985b

Callochiton septemvalvis euplaeae; Kaas and Van Belle, p. 11, fig. 2.2, 2.3, 2.7, part (non fig. 2.1, 2.4–2.6, 2.8–2.15 = Callochiton septemvalvis).

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999

Callochiton septemvalvis (non Montagu); Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, p. 125, pl. 40, figs. A–H, pl. 41, figs. I–P, color figs. 61–63.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003

Callochiton septemvalvis (non Montagu); Dell'Angelo and Silva, p. 11, part (only one of the two intermediate valves).

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Garilli, Germanà, Reitano, Sosso and Bonfitto2012

Callochiton septemvalvis (non Montagu); Dell'Angelo et al., p. 60, fig. 4L.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013

Callochiton septemvalvis (non Montagu); Dell'Angelo et al., p. 83, pl. 5, figs. N–P.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016

Callochiton doriae; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 74, pl. 1, figs. 5–9.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Renda, Sosso, Sigwart and Giacobbe2017

Callochiton doriae; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 243, fig. 5A–C.

Holotype

Unknown, probably lost. Mediterranean, northern Ligurian Sea, Gulf of La Spezia, Italy (Capellini, Reference Capellini1859).

Occurrence

Lower Miocene: Proto-Mediterranean Sea in Italy, Sciolze (Burdigalian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016). Middle Miocene: Proto-Mediterranean Sea in Italy, Po Basin (Langhian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016); Paratethys in Slovakia (Ruman and Hudáčková, Reference Ruman and Hudácková2015), Czech Republic (Šulc, Reference Šulc1934), Poland (Bałuk, Reference Bałuk1971, Reference Bałuk1984; Studencka and Studencki, Reference Studencka and Studencki1988), and Austria (Šulc, 1934). Upper Miocene: northeastern Atlantic in France, Anjou (Tortonian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau, Van Dingenen and Ceulemans2018b); Proto-Mediterranean Sea in Italy, Po Basin (Tortonian, Laghi, Reference Laghi1977; Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016). Lower Pliocene: central Mediterranean in Italy, Liguria (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013), and Tuscany (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Forli and Lombardi2001). Lower to Upper Pliocene: northeastern Atlantic in Portugal, Mondego Basin (MPMU1, Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003); central Mediterranean in Italy, Sicily (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Garilli, Germanà, Reitano, Sosso and Bonfitto2012), western Mediterranean in Spain, Estepona Basin (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau and Marquet2004). Upper Pliocene to Lower Pleistocene in the central Mediterranean, Greece, Rhodes (Koskeridou et al., Reference Koskeridou, Vardala-Theodorou and Moissette2009). Lower Pleistocene: central Mediterranean in Italy (Sabelli and Taviani, Reference Sabelli and Taviani1979; Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Forli and Lombardi2001). Middle to Upper Pleistocene: central Mediterranean in Greece (Garilli et al., Reference Garilli, Dell'Angelo and Vardala-Theodorou2005). Pleistocene: central Mediterranean in Italy (Dell'Angelo and Giusti, Reference Dell'Angelo and Giusti1997). Present: Atlantic Ocean, from Spain, Galicia (Carmona Zalvide et al., Reference Carmona Zalvide, García and Urgorri2002), south to Madeira (Segers et al., Reference Segers, Swinnen and De Prins2009), Morocco (Kaas, Reference Kaas1991), and Canary Islands (Kaas, Reference Kaas1991); Mediterranean Sea in France, Italy (Leloup, Reference Leloup1934; Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999), Croatia (Dell'Angelo and Zavodnik, Reference Dell'Angelo and Zavodnik2004), Greece and Aegean Sea islands (Strack, Reference Strack1988, Reference Strack1990; Koukouras and Karachle, Reference Koukouras and Karachle2005), Lebanon (Crocetta et al., Reference Crocetta, Bitar, Zibrowius, Capua, Dell'Angelo and Oliverio2014), Israel (Barash and Danin, Reference Barash and Danin1977), Algeria (Pallary, Reference Pallary1900), and Tunisia (Kaas, Reference Kaas1989; Cecalupo et al., Reference Cecalupo, Buzzurro and Mariani2008).

Materials

213 valves (154 intermediate and 59 tail): one intermediate and one tail valve lost (Fig. 7.13, 7.17, 7.18) and replaced by specimens GeoFCUL VFX.03.356, VFX.03.357, RGM.1364012 (one valve) (Fig. 7.14), GeoFCUL VFX.03.340 (one valve) (Fig. 7.15, 7.16), RGM.1364013 (20 valves), GeoFCUL VFX.03.341 (20 valves), MNHN.F.A81987 (20 valves), BD 242 (149 valves). Maximum width: – | 3 | 1.8 mm.

Remarks

Prior to Sigwart et al. (Reference Sigwart, Stoeger, Knebelsberger and Schwabe2013) a single Callochiton species was recognized along the eastern Atlantic coast and in the Mediterranean Sea. However, based on molecular data, those authors separated the European Callochiton septemvalvis specimens into a Mediterranean species (C. doriae) with grooves on the valves, and an Atlantic species (C. septemvalvis) without grooves. The Vale de Freixo material is imperfectly preserved, but the material considered C. doriae herein clearly shows longitudinal grooves (4–8, with short grooves along the diagonal ridge) on the pleural areas of intermediate valves (Fig. 7.13) and on the antemucronal area of the tail valve.

Family Chitonidae Rafinesque, Reference Rafinesque1815

Subfamily Chitoninae Rafinesque, Reference Rafinesque1815

Genus Rhyssoplax Thiele, Reference Thiele1893

Type species

Chiton affinis Issel, Reference Issel1869, by subsequent designation (International Committee of Zoological Nomenclature, 1971, as proposed by Beu et al., Reference Beu, Dell and Fleming1969).

Occurrence

Known from Oligocene to present. Today it is mostly tropical to subtropical, occurring from the eastern Atlantic and South Africa and throughout the Indo-Pacific to the central Pacific, including northern New Zealand to Hawaii (Schwabe et al., Reference Schwabe, Sirenko and Seeto2008).

Rhyssoplax corallina (Risso, Reference Risso1826)

Figure 8.1–8.9

- Reference Risso1826

Lepidopleurus corallinus Risso, p. 268.

- Reference Arnaud1977

Lepidopleurus corallinus; Arnaud, p. 112.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999

Chiton (Rhyssoplax) corallinus; Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, p. 174, pl. 58–59, color figs. 97–107.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003

Chiton (Rhyssoplax) corallinus; Dell'Angelo and Silva, p. 14, fig. 12.

- Reference Kaas, Van Belle and Strack2006

Chiton (Rhyssoplax) corallinus; Kaas et al., p. 154, fig. 56.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016

Chiton corallinus; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 78, pl. 2, figs. 1–15.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau, Van Dingenen and Ceulemans2018b

Rhyssoplax corallinus; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 35, fig. 18.

Figure 8. (1–9) Rhyssoplax corallina (Risso, Reference Risso1826) from the Carnide Formation, Pliocene, Portugal: (1–3) RGM.1364014, head valve in (1) dorsal, (2) ventral, and (3) lateral views; width 2.2 mm; (4–6) GeoFCUL VFX.03.342, intermediate valve in (4) dorsal, (5) ventral, and (6) lateral views; width 2.6 mm; (7–9) MNHN.F.A81988, tail valve in (7) dorsal, (8) ventral, and (9) lateral views; width 2.5 mm. (10–15) Lepidochitona cinerea (Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1767) from the Carnide Formation, Pliocene, Portugal: (10, 11) head valve (10) in dorsal view and (11) close-up of ornamentation; width 1.9 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.358); (12) tail valve in dorsal view; width 1.9 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.359); (13–15) intermediate valve (13) in dorsal view, (14) close–up of ornamentation, and (15) frontal view; width 3.3 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.360). Scale bars = 0.5 mm (1–10, 12, 13, 15), or 100 μm (11, 14).

Holotype

Presumed lost, not present in the Risso collection, MNHN (Arnaud, Reference Arnaud1977). Western Mediterranean Sea, France, Nice.

Occurrence

Upper Oligocene: northeastern Atlantic in France, Aquitaine Basin (Chattian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Lesport, Cluzaud and Sosso2018a). Lower Miocene: northeastern Atlantic in France, Aquitaine Basin (Aquitanian–Burdigalian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Lesport, Cluzaud and Sosso2018a); Proto-Mediterranean Sea in Italy, Po Basin (Burdigalian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016). Middle Miocene: northeastern Atlantic in France, Aquitaine Basin (Serravalian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Lesport, Cluzaud and Sosso2018a); Proto-Mediterranean in Italy, Po Basin (Langhian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016); Paratethys, in Slovakia (Ruman and Hudáčková, Reference Ruman and Hudácková2015), Czech Republic (Šulc, Reference Šulc1934), Poland (Bałuk, Reference Bałuk1971, Reference Bałuk1984; Macioszczyk, Reference Macioszczyk1988; Studencka and Studencki, Reference Studencka and Studencki1988), Austria (Šulc, Reference Šulc1934; Kroh, Reference Kroh2003), Hungary (Dulai, Reference Dulai2005), Romania (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Grigis and Bonfitto2007), and Ukraine (Studencka and Dulai, Reference Studencka and Dulai2010). Upper Miocene: northeastern Atlantic in France, Anjou (Tortonian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau, Van Dingenen and Ceulemans2018b), Loire Basin (Messinian?, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Lesport, Cluzaud and Sosso2018a); Proto-Mediterranean in Italy, Po Basin (Tortonian, Laghi, Reference Laghi1977; Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999, 2016). Lower Pliocene: central Mediterranean in Italy, Liguria (Chirli, Reference Chirli2004; Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013), and Tuscany (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Forli and Lombardi2001). Lower to Upper Pliocene: northeastern Atlantic in Portugal, Mondego Basin (MPMU1, Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003); western Mediterranean, Spain, Estepona Basin (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau and Marquet2004); central Mediterranean, Italy (Laghi, Reference Laghi1977). Upper Pliocene to Lower Pleistocene: central Mediterranean in Greece, Rhodes (Koskeridou et al., Reference Koskeridou, Vardala-Theodorou and Moissette2009). Lower Pleistocene: central Mediterranean in Italy (Sabelli and Taviani, Reference Sabelli and Taviani1979; Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Forli and Lombardi2001). Middle to Upper Pleistocene: central Mediterranean in Greece, Kyllini (Garilli et al., Reference Garilli, Dell'Angelo and Vardala-Theodorou2005). Upper Pleistocene: central Mediterranean in Italy (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Forli and Lombardi2001). Present: Atlantic Ocean, from Spain and Portugal (Macedo et al., Reference Macedo, Macedo and Borges1999; Carmona Zalvide et al., Reference Carmona Zalvide, García and Urgorri2000), to Morocco (Pallary, Reference Pallary1920), and the Ampère and Gettysburg seamounts (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Metzger and Freiwald2006); Mediterranean Sea in Spain, Alboran (Salas and Luque, Reference Salas and Luque1986), France (Marion, Reference Marion1883; Pruvot, Reference Pruvot1897), Italy (Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999), Croatia (Leloup and Volz, Reference Leloup and Volz1938; Dell'Angelo and Zavodnik, Reference Dell'Angelo and Zavodnik2004), Greece and Aegean Sea islands (Strack, Reference Strack1988, Reference Strack1990; Koukouras and Karachle, Reference Koukouras and Karachle2005), Turkey (Öztürk et al., Reference Öztürk, Doğan, Bitlis-Bakir and Salman2014), Algeria (Mars, Reference Mars1957), Tunisia (Kaas, Reference Kaas1989; Cecalupo et al., Reference Cecalupo, Buzzurro and Mariani2008), Israel (Barash and Danin, Reference Barash and Danin1977), and Lebanon (Crocetta et al., Reference Crocetta, Bitar, Zibrowius, Capua, Dell'Angelo and Oliverio2014).

Materials

664 valves (30 head, 416 intermediate and 218 tail valves): RGM.1364014 (Fig. 8.1–8.3), GeoFCUL VFX.03.342 (Fig. 8.4–8.6), MNHN.F.A81988 (Fig. 8.7–8.9), RGM.1364015 (50 valves), GeoFCUL VFX.03.343 (50 valves), MNHN.F.A81989 (50 valves), BD 243 (511 valves). Maximum width: 2.2 | 3.5 | 2.5 mm.

Remarks

Detailed description and discussion of R. corallina were given by Dell'Angelo and Smriglio (Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999) and Kaas et al. (Reference Kaas, Van Belle and Strack2006). The study material is represented by small, incomplete, and abraded valves, in which diagnostic characters are often not clearly distinguishable.

Suborder Acanthochitonina Bergenhayn, Reference Bergenhayn1930

Superfamily Mopalioidea Dall, Reference Dall1889

Family Lepidochitonidae Iredale, Reference Iredale1914

Genus Lepidochitona Gray, Reference Gray1821

Type species

Chiton marginatus Pennant, Reference Pennant1777 (= Chiton cinereus Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1767), by monotypy.

Occurrence

Known from Paleocene to present. Today, it occurs in five disjunct areas: (1) Black and Mediterranean seas, and northeastern Atlantic, from northern Norway to Morocco; (2) Red Sea and northern Arabian Sea; (3) off South Africa; (4) Caribbean Sea and adjacent waters of the Atlantic Ocean; and (5) the eastern Pacific Ocean from the Gulf of Alaska to Peru (Kaas and Van Belle, Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985b; Sirenko et al., Reference Sirenko, Abramson and Yagapov2013).

Lepidochitona cinerea (Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1767)

Figure 8.10–8.15

- Reference Linnaeus1767

Chiton cinereus Linnaeus, p. 1107.

- Reference Dodge1952

Chiton cinereus; Dodge, p. 23.

- Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985b

Lepidochitona (L.) cinerea; Kaas and Van Belle, p. 84, fig. 39.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999

Lepidochitona (L.) cinerea; Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, p. 138, pl. 44–45, color figs. 67–72.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003

Lepidochitona (L.) cinerea; Dell'Angelo and Silva, p. 12, figs. 13, 14.

- Reference Garilli, Dell'Angelo and Vardala-Theodorou2005

Lepidochitona (L.) cinerea; Garilli et al., p. 136, pl. 3, figs. 1–3.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013

Lepidochitona cinerea; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 89, pl. 8, figs. A–E.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016

Lepidochitona cinerea; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 83, pl. 3, figs. 13–18.

Holotype

LSL (Dodge, Reference Dodge1952). “In O. Norvegico.” (Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1767).

Occurrence

Upper Miocene: Proto-Mediterranean Sea in Italy, Po Basin (Tortonian, Sacco, Reference Sacco1897; Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999; Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016). Lower Pliocene: central Mediterranean in Italy, Liguria (Sosso and Dell'Angelo, Reference Sosso and Dell'Angelo2010; Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013), Tuscany (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Forli and Lombardi2001). Lower to Upper Pliocene: northeastern Atlantic in Portugal, Mondego Basin (MPMU1, Dell'Angelo and Silva, Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003); central Mediterranean in Italy, Tuscany (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Forli and Lombardi2001; Chirli, Reference Chirli2004). Upper Pliocene to Lower Pleistocene: Mediterranean in Greece, Rhodes (Koskeridou et al., Reference Koskeridou, Vardala-Theodorou and Moissette2009). Pleistocene: Mediterranean in Italy (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Forli and Lombardi2001), and Greece (Garilli et al., Reference Garilli, Dell'Angelo and Vardala-Theodorou2005). Present: Atlantic Ocean, from Iceland and Norway, Tromsö (Sneli and Gudmundsson, Reference Sneli and Gudmundsson2018), along the European coast (Leloup, Reference Leloup1934; Kaas and Van Belle, Reference Kaas1981; Hansson, Reference Hansson1998) to France, Spain, Portugal (Macedo et al., Reference Macedo, Macedo and Borges1999; Carmona Zalvide and García García, Reference Carmona Zalvide and García García2000; Urgorri et al., Reference Urgorri, Díaz-Agras, García-Álvarez, Señarís and Banón2017), Morocco, and Senegal (Kaas, Reference Kaas1991); Mediterranean Sea, in Spain and France (Giribet and Penas, Reference Giribet and Penas1997), Italy (Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999), Malta (Mifsud et al., Reference Mifsud, Cachia and Sammut1990), Greece and the Aegean Sea islands (Strack, Reference Strack1988, Reference Strack1990; Koukouras and Karachle, Reference Koukouras and Karachle2005), Turkey (Öztürk et al., Reference Öztürk, Doğan, Bitlis-Bakir and Salman2014), Israel (Barash and Danin, Reference Barash and Danin1977, Reference Barash and Danin1992), Algeria (Pallary, Reference Pallary1900), Tunisia (Kaas, Reference Kaas1989; Cecalupo et al., Reference Cecalupo, Buzzurro and Mariani2008), and in the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara (Strack, Reference Strack1988).

Materials

93 valves (60 head, 26 intermediate, and 7 tail): one head valve, one tail, and one intermediate lost (Fig. 8.10–8.12, 8.13–8.15) and replaced by specimens GeoFCUL VFX.03.358– VFX.03.360, RGM.1364016 (5 valves), GeoFCUL VFX.03.348 (5 valves), MNHN.F.A81990 (5 valves), BD 244 (75 valves). Maximum width: 3 | 3.3 | 2.4 mm.

Remarks

Detailed descriptions and discussion of specimens of the species were given by Kaas and Van Belle (Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985b) and Dell'Angelo and Smriglio (Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999).

Lepidochitona canariensis (Thiele, Reference Thiele1909)

- Reference Thiele1909

Trachydermon canariensis Thiele, p. 15, pl. 2, figs. 14–25.

- Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985b

Lepidochitona (L.) canariensis; Kaas and Van Belle, p. 95, fig. 44.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999

Lepidochitona (Lepidochitona) canariensis; Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, p. 154, pl. 51, fig. 78.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Tringali2000

Lepidochitona canariensis; Dell'Angelo and Tringali, p. 51, fig. 1.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau and Marquet2004

Lepidochitona (L.) canariensis; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 36, pl. 3, fig. 3.

- Reference Anseeuw and Verstraeten2009

Lepidochitona canariensis; Anseeuw and Verstraeten, p. 30, pl. 1, figs. 1–3.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013

Lepidochitona canariensis; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 91, pl. 8, figs. L–Q.

- Reference Dell'Angelo and Tringali2020

Lepidochitona canariensis; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 29, fig. 19.

Holotype

ZMHU 101918a (Kilias, Reference Kilias1995, p. 158). Eastern Atlantic, Canary Islands, Tenerife, Puerto.

Occurrence

Lower Miocene: northeastern Atlantic in France, Aquitaine Basin (Burdigalian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Lesport, Cluzaud and Sosso2020). Upper Miocene: northeastern Atlantic in France, Loire Basin (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Lesport, Cluzaud and Sosso2020). Lower Pliocene: central Mediterranean in Italy, Liguria (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013). Lower to Upper Pliocene: northeastern Atlantic, Portugal, Mondego Basin (MPMU1, this paper); western Mediterranean, Spain, Estepona Basin (Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau and Marquet2004). Upper Pliocene to Lower Pleistocene: central Mediterranean, Greece, Rhodes (Koskeridou et al., Reference Koskeridou, Vardala-Theodorou and Moissette2009). Present: Atlantic Ocean, from southern Portugal and southwestern Spain (Carmona Zalvide and García García, Reference Carmona Zalvide and García García2000) to Mauritania (Anseeuw and Verstraeten, Reference Anseeuw and Verstraeten2009), Madeira (Van Belle, Reference Van Belle1985; Kaas, Reference Kaas1991) and Selvagens islands (Segers et al., Reference Segers, Swinnen and De Prins2009), Canaries (Kaas, Reference Kaas1991; Hernández and Rolán, Reference Hernández, Rolán and Rolán2011), and Cape Verde islands (Strack, Reference Strack and Rolán2005); Mediterranean in the Alboran Sea, and Morocco (Dell'Angelo and Tringali, Reference Carmona Zalvide and García García2000).

Materials

Two valves lost during photography. Maximum width: 1.6 mm.

Remarks

Detailed descriptions and discussion of specimens of this species were given by Kaas and Van Belle (Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985b) and Dell'Angelo and Smriglio (Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999). The valves are characterized by diamond-shaped granules uniformly covering the tegmentum, with a tendency to form longitudinal striae converging in the pleural areas. The valves are similar to those of L. cinerea (see above), from which they differ in being smaller, intermediate valves with a more clearly delimited apex and a coarser granulation of the tegmentum. The material examined exhibits sculpture formed by less-numerous and larger granules than those of L. cinerea. Despite the scarcity and the poor preservation of the material, the shape and the sculpture of the two specimens examined allow attribution to L. canariensis.

Lepidochitona rochae new species

Figure 9

Holotype

Holotype RGM.1364017, intermediate valve (width 2.3 mm, Fig. 9.1–9.3).

Figure 9. Lepidochitona rochae n. sp. from the Carnide Formation, Pliocene, Portugal: (1–3) holotype, RGM.1364017, intermediate valve in (1) dorsal, (2) ventral, and (3) frontal views; width 2.3 mm; (4, 5) paratype, RGM.1364018, intermediate valve in (4) dorsal view and (5) close-up of ornamentation; width 4.8 mm; (6) GeoFCUL VFX.03.344, intermediate valve in frontal view; width 2.4 mm; (7–9) intermediate valve in (7) dorsal view and (8, 9) close-up of ornamentation; width 2.4 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.361). Scale bars = 0.5 mm (1–4, 6, 7), or 100 μm (5, 8, 9).

Paratype

Paratype RGM.1364018, intermediate valve (width 4.8 mm, Fig. 9.4, 9.5). Vale de Freixo site, near the village of Carnide, Pombal municipality, central-west Portugal (Fig. 1). Pliocene, upper Zanclean to lower Piacenzian, Carnide Formation, basal fossiliferous gray sands, “Bed 3” in Gili et al. (Reference Gili, Silva and Martinell1995), Dell'Angelo and Silva (Reference Dell'Angelo and Silva2003), and herein (Fig. 2). Equivalent to the Mediterranean MPMU1 of Monegatti and Raffi (Reference Monegatti and Raffi2001).

Diagnosis

Intermediate valves broadly rectangular, elevated, carinate, showing lateral areas sculptured with fine elongate granules, coalescing into continuous, radially oriented lines. Central area covered for ~60% of valve width by roundish irregular granules, the remaining surface, continuing towards side margins, covered by obliquely oriented and widely spaced concentric growth lines.

Occurrence

Pliocene: northeastern Atlantic, Mondego Basin, Portugal (MPMU1, this paper).

Description

Intermediate valves broadly rectangular, W/L = 2.70–2.90, elevated (H/W = 0.40–0.50), anterior profile carinate, anterior margin convex with jugal part almost straight, side margins slightly rounded, posterior margin straight or slightly concave on both sides of large and prominent apex, lateral areas slightly raised, sharply delimited, sculptured with fine elongate granules, coalescing into continuous, radially oriented lines; few concentric growth lines more evident towards side margins, central area covered for ~60% of valve width by roundish irregular granules, almost all separated, but some coalescent, with up to eight aesthetes of equal size, 40% continuing towards side margins by obliquely oriented and few concentric growth lines joined with those present on lateral areas. Articulamentum with poorly preserved apophyses, round, apical area triangular, insertion plate short with a single slit, slit ray well visible (a second slit ray lies close to posterior margin on intermediate valves).

Etymology

Named after Rogério Bordalo da Rocha (1941–2018), Portuguese Jurassic ammonite paleontologist at the Department of Earth Sciences of the Faculty of Sciences and Technology of the Nova University of Lisbon, Portugal, and President of the Portuguese Geological Society from 1987–2006 to 2010–2014. According to the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) norm, the word rocha (meaning rock in Portuguese, also a surname) is pronounced /'Rɔ.ʃɐ/.

Other materials

Fourteen intermediate valves: one valve lost (Fig. 9.7–9.9) and replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.361, GeoFCUL VFX.03.344 (one valve) (Fig. 9.6), RGM.1364019 (2 valves), GeoFCUL VFX.03.345 (2 valves), MNHN.F.A81991 (2 valves), BD 245 (6 valves). Maximum width 4.8 mm.

Paleoecology

Epibenthic vagile mollusks living in coastal infralittoral subtropical marine environments (estimated maximum mean monthly SST, MMSST, of ~23.5°C in September and minimum MMSST of 19°C in January–March; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Landau, Domènech and Martinell2010) of normal salinity and sand-pebble shelly substrates.

Remarks

Only a few incomplete and poorly preserved intermediate valves are present in the study material, nevertheless the unique character of their sculpture warrants description as a new species. The generic attribution, however, is problematic. The granules of the tegmental sculpture of the material at hand are closer to those of Lepidochitona than to those of any other genus. Nevertheless, in specimens of Lepidochitona, the granules normally cover the entire tegmentum, not only part of it, as seen in the valves of L. rochae n. sp. The sculpture of the lateral areas (fine elongate granules coalescing into continuous, radially oriented lines) is similar to that observed in numerous species of Callochiton (e.g., C. septemvalvis and C. doriae, see above). However, Callochiton is characterized by unique features (e.g., apophyses connected across the jugal sinus, and presence of extra-pigmentary eyes) that are not present in L. rochae n. sp. specimens. Therefore, the new species is assigned to Lepidochitona, mainly on the basis of the similarity of the granules in the central area of the valves with the sculpture typical of this genus.

Lepidochitona is a speciose genus in the Mediterranean Sea (Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, Reference Dell'Angelo and Smriglio1999) and five species are known along the Atlantic coasts of the Iberian Peninsula: L. cinerea, L. caprearum (Scacchi, Reference Scacchi1836), L. simrothi (Thiele, Reference Thiele1902), L. canariensis, and L. monterosatoi Kaas and Van Belle, Reference Kaas1981 (Kaas and Van Belle, Reference Kaas and Van Belle1985b; Carmona Zalvide and García García, Reference Carmona Zalvide and García García2000). All these species show a uniformly granulose sculpture, very different from the sculpture of L. rochae n. sp., in which the granules cover only part of the central area.

Superfamily Cryptoplacoidea H. and A. Adams, Reference Adams and Adams1858

Family Acanthochitonidae Pilsbry, Reference Pilsbry and Tryon1893

Genus Acanthochitona Gray, Reference Gray1821

Type species

Chiton fascicularis Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1767, by monotypy.

Occurrence

Known from the Oligocene of France, Aquitaine Basin (Chattian, Dell'Angelo et al., Reference Dell'Angelo, Lesport, Cluzaud and Sosso2020) to the present. Today, the genus has an almost worldwide distribution, except for polar waters.

Acanthochitona crinita (Pennant, Reference Pennant1777)

Figure 10

- Reference Pennant1777

Chiton crinitus Pennant, p. 71, pl. 36, figs. 1, A1.

- Reference Kaas1985

Acanthochitona crinita; Kaas, p. 588, figs. 7–50.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999

Acanthochitona crinita; Dell'Angelo and Smriglio, p. 198, pl. 66–68, color figs. 124–130.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Palazzi and Pavia1999

Acanthochitona crinita; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 275, pl. 5, figs. 2, 6.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Forli and Lombardi2001

Acanthochitona crinita; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 153, fig. 32.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau and Marquet2004

Acanthochitona crinita; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 40, pl. 4, figs. 2, 5.

- Reference Koskeridou, Vardala-Theodorou and Moissette2009

Acanthochitona crinita; Koskeridou et al., p. 322, figs. 11.1, 11.2.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Sosso, Prudenza and Bonfitto2013

Acanthochitona crinita; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 96, pl. 10, figs. H–M.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Giuntelli, Sosso and Zunino2016

Acanthochitona crinita; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 88, pl. 5, figs. 12–18, pl. 6, figs. 1, 2.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Landau, Van Dingenen and Ceulemans2018b

Acanthochitona crinita; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 41, table 14.

- Reference Dell'Angelo, Lesport, Cluzaud and Sosso2020

Acanthochitona crinita; Dell'Angelo et al., p. 39, fig. 25.

Figure 10. Acanthochitona crinita (Pennant, Reference Pennant1777) from the Carnide Formation, Pliocene, Portugal: (1–3) RGM.1364020, head valve in (1) dorsal, (2) ventral, and (3) lateral views, width 1.7 mm; (4–6) intermediate valve in (4) dorsal view, (5) close-up of ornamentation, and (6) frontal view; width 2.5 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.362); (7–9) tail valve in (7) dorsal view, (8) close-up of ornamentation, and (9) lateral view; width 2.1 mm (valve lost, replaced by specimen GeoFCUL VFX.03.363). Scale bars = 0.5 mm (1–4, 6, 7, 9), or 100 μm (5, 8).

Holotype

Neotype RSMNH 1978.052.02601, designated and figured by Kaas (Reference Kaas1985, p. 591, fig. 27). Northern Atlantic, Hebrides Islands, Monach Island, North Uist, Great Britain.

Occurrence