Introduction

Gazetting and maintaining protected areas (PAs) are political processes and, as such, depend on wider society’s support in order to achieve their goals (Hirschnitz-Garbers & Stoll-Kleemann Reference Hirschnitz-Garbers and Stoll-Kleemann2011). Public support is required from multiple stakeholders through all steps of the political process that lead to the legal recognition and establishment of a PA (Silva & Chennault Reference Silva, Chennault, Dellasala and Goldstein2018). For instance, without support from people living in urban centres, politicians would not be able to set aside PAs or, most importantly, allocate scarce public funds to maintain them (Dias et al. Reference Dias, Cunha and Silva2016). Furthermore, without support from people living in or around PAs, conflicts can arise and, as a result, jeopardize conservation efforts (e.g., Struhsaker et al. Reference Struhsaker, Struhsaker and Kirstin2005). Because politicians often view PAs as an opportunity cost, especially where competition with other land uses is high, public support for PAs acts as a safeguard against the influence of special interest groups (i.e., the agricultural and mining lobbies) on the fate of natural ecosystems.

Public support for PAs can be influenced by several factors, but, among the factors described in the literature, education, income, age, gender, place of residence and place of origin seem to be the most influential on individual attitudes regarding environmental protection (e.g., Gelissen Reference Gelissen2007, Nastran & Istenic Reference Nastran and Istenic2015, Bragagnolo et al. Reference Bragagnolo, Malhado, Jepson and Ladle2016). For instance, education and income, respectively, are the first and second most significant predictors of positive attitudes towards PAs (Bragagnolo et al. Reference Bragagnolo, Malhado, Jepson and Ladle2016). In contrast, age often has a negative association with support for environmental protection (Shibia Reference Shibia2010). Gender seems to matter as well: for instance, Allendorf and Allendorf (Reference Allendorf and Allendorf2013) found that, among rural populations in Myanmar, women are less likely to have a positive attitude towards PAs than men, possibly because they are less informed about wildlife, the non-economic benefits that PAs can provide and PA management. Place of residence has been found to be relevant because the livelihoods of people living inside or near PAs are usually affected by regulations set by state agencies (Holmes Reference Holmes2013), so they are expected to show less support for environmental conservation than people living in other rural areas or in urban areas (Triguero-Mas et al. Reference Triguero-Mas, Olomí-Solà, Jha, Zorondo-Rodríguez and Reyes-García2010, Bragagnolo et al. Reference Bragagnolo, Malhado, Jepson and Ladle2016, Byrka et al. Reference Byrka, Kaiser and Olko2017). Finally, cultural factors, such as place attachment (i.e., the existence of emotional and cognitive bonds with a place), can also play a role. In general, people who are born in the region where a PA has been gazetted will show more support for nature conservation than outsiders if they have strong place attachment (Carrus et al. Reference Carrus, Bonaiuto and Bonnes2005).

Wide public support for PA systems is essential everywhere, but it is more important in new tropical forest frontiers – regions that have high forest cover, low deforestation, low population density and low human development standards and that are experiencing periods of rapid agriculture expansion due to policy shifts and infrastructure improvements (Dias et al. Reference Dias, Cunha and Silva2016). New tropical forest frontiers are globally relevant because they harbour most of the planet’s terrestrial biodiversity and forest carbon stocks (Fonseca et al. Reference Fonseca, Rodriguez, Midgley, Busch, Hannah and Mittermeier2007) and are home to unique indigenous cultures (Garnett et al. Reference Garnett, Burgess, Fa, Fernández-Llamazares, Molnár and Robinson2018). In addition, they are the places where conflicts could emerge in the near future if combined conservation and development programmes are not implemented at an appropriate pace (Angelsen & Rudel Reference Angelsen and Rudel2013).

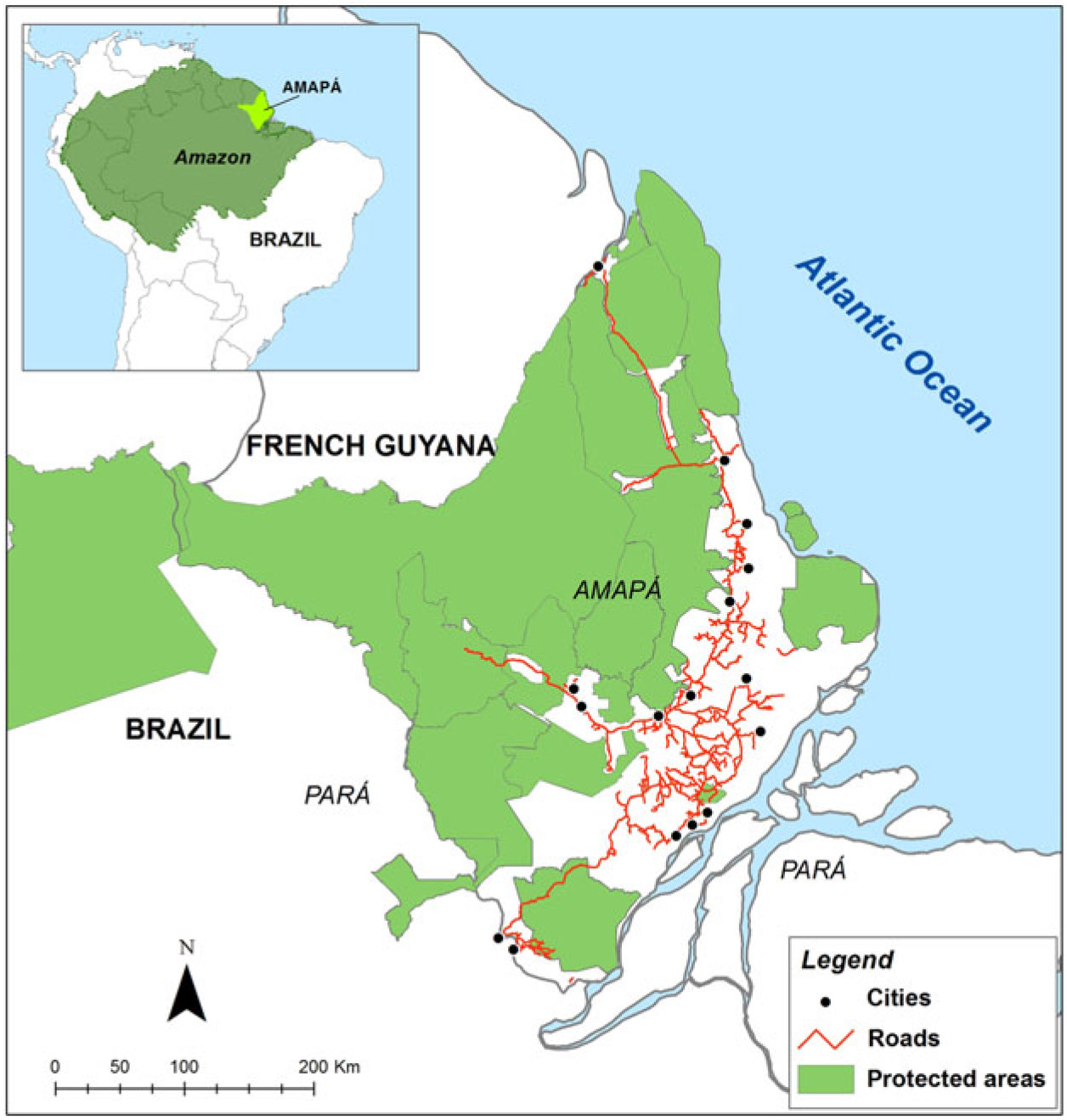

In this paper, we assess the public support for PAs in a new forest frontier in northern South America, one of the world’s most protected tropical forest regions (Mittermeier et al. Reference Mittermeier, Mittermeier, Brooks, Pilgrim, Konstant, da Fonseca and Kormos2003). Specifically, we evaluate whether public support for PAs is influenced by age, gender, education, income, place of residence and place of origin. We selected the Brazilian state of Amapá as the study area. This state has adopted an ambitious conservation strategy since 1985. As a result, it has set aside 72% of its area in PAs and achieved the country’s lowest deforestation rates (Dias et al. Reference Dias, Cunha and Silva2016). Yet recent infrastructure development and policy changes have triggered a rapid process of commercial agriculture expansion in the state, which, over time, could undermine some of the conservation gains (Carvalho & Mustin Reference Carvalho and Mustin2017). This negative trend could be accelerated with the recent election of a new federal government that has a strong anti-conservation position (Darby Reference Darby2018). Because of that, Amapá can be considered a natural laboratory for monitoring and understanding the conservation challenges in new forest frontiers.

Methods

Study area

Amapá has an area of 142 828 km2 and an estimated population of 829 494 people in 2018 (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística 2018). It harbours a diverse combination of ecosystems. Along the Atlantic coast, Amapá has the best-preserved mangroves in the Americas. In the south and along the Amazon River, mangroves are replaced by seasonally flooded grasslands and forests. Moving inland, there is a narrow belt of upland savannas that harbours distinctive fauna and flora (Mustin et al. Reference Mustin, Carvalho, Hilário, Costa-Neto, Silva, Vasconcelos and Toledo2017). The savannas, in turn, are replaced by different types of terra firme forests, the state’s dominant vegetation (Instituto de Pesquisas Científicas e Tecnológicas do Estado do Amapá 2008). Amapá’s society is mostly urban (90%), with 74% of the population living in two major adjacent cities: Macapá, the capital, and Santana (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística 2018).

Amapá’s society has followed a conservation-centred development model whose principles remain intact despite the alternation of two dominant and rival parties (Brazilian Socialist Party and Democratic Labor Party) in the state government over the last 30 years (see reviews in Ruellan & Ruellan Reference Ruellan, Ruellan, Ruellan, Cabral and Moulin2007, Drummond et al. Reference Drummond, Dias and Brito2008). The adoption of a conservation-centred development model in Amapá was partially facilitated because the state has no road connections to the rest of Brazil and has limited connections with neighbouring French Guyana. In addition, both national and state governments have been very active in establishing PAs and indigenous lands, which together cover 72% of the state, making Amapá Brazil’s most protected state (Fig. 1). The Amapá PA system is anchored by the Montanhas do Tumucumaque National Park, a mega-reserve of 3.4 million ha surrounded by 18 PAs with different management categories, ranging from strict PAs to multiple-use reserves and indigenous lands. However, in the last 10 years, Amapá has experienced a rapid transformation in its economic profile, moving from the stage of a core forest to the stage of a frontier forest (sensu Angelsen & Rudel Reference Angelsen and Rudel2013). New hydroelectric facilities have been built, increasing the installed power generation capacity in the state (Santos et al. Reference Santos, Cunha and Cunha2017). In addition, the state has been connected to the national energy grid, ensuring a stable and relatively cheap energy supply compared with the past. Roads have been paved and the primary port has been improved. Low-cost land and a shorter maritime distance to China (via the Panamá Canal) and Europe, when compared to central-south Brazil, have made Amapá an attractive place for commercial farmers from other parts of Brazil. Soybean plantations are increasing exponentially in the state, generating large-scale land-use changes along the savanna belt (Hilário et al. Reference Hilário, Toledo, Mustin, Castro, Costa-Neto and Kauano2017). There is concern that the agriculture expansion in Amapá will lead to land conflicts between farmers and local populations (Gallazzi Reference Gallazzi, Lomba, Rangel, Silva and Silva2016), water and soil pollution via the introduction of chemicals and fertilizers (Gomes & Barizon Reference Gomes and Barizon2014) and loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services (Mustin et al. Reference Mustin, Carvalho, Hilário, Costa-Neto, Silva, Vasconcelos and Toledo2017).

Fig. 1. Most of the state of Amapá, Brazil, is covered by protected areas.

Data collection

Because we were interested in understanding the public support of the whole population of Amapá for PAs, we used proportionate stratified random sampling considering the distribution of the population in urban and rural settings. Hence, from the 740 interviews we conducted for this study, 600 were conducted in urban settings and 140 were conducted in rural settings. The number of people who were approached and did not want to participate of the study was 1 in rural settings and 25 in urban settings. To represent urban areas, we selected Macapá, the state’s most densely populated city, where 59.5% of the state’s population lives. To represent rural areas, we chose a group of villages and settlements inside and outside (but under the influence of) the State Forest of Amapá (FLOTA Amapá) and the Rio Cajari Extractive Reserve (RESEX Rio Cajari). These two large PAs altogether cover 20.3% of Amapá and include 12 out of 16 municipalities. We sampled four groups of rural localities: (1) inside the FLOTA Amapá (Água Nova, São Sebastião do Cachaço and Torrão); (2) outside the FLOTA Amapá (Arrependido, Base Aérea, Perpétuo Socorro, São Benedito, Terra Preta and Vila Nova); (3) inside the RESEX Rio Cajari (Marinho, Martins, São Pedro and Santa Clara); and (4) outside the RESEX Rio Cajari (Camaipi, França Rocha, Igarapé das Pacas, Padaria, Retiro and Santo Antônio da Cachoeira).

Interviews were conducted by HC, AS and seven trained research assistants in both urban and rural areas from June 2016 to March 2017. In each locality, we randomly approached the participants in their homes (choosing every other home in rural settings) or in public places (in urban settings; e.g., shopping malls, on the street). We began each interview by explaining the overall goals of the research and affirming the anonymous nature of the survey. We spent more time explaining our research to rural participants in order to gain their confidence so that they would share their deeply held views about PAs with us. Although we cannot eliminate the uncertainties associated with the participants’ responses, it was clear through our interactions that participants did not recognize us as members of the agencies that are responsible for managing PAs. The first part of the survey was composed of closed questions about five variables: two categorical (gender and place of origin) and three continuous (age, education and income). To identify the origin of the participants, we asked them the exact name of the place where they were born. Later, we coded the birthplaces of the participants into two groups: Amazonians (if the participant was born in one of the states that comprise the Brazilian Amazon: Roraima, Amazonas, Acre, Rondônia, Pará and Amapá) and non-Amazonians (if the participant was born in any other Brazilian state). Education was measured as years of schooling and income as the estimated annual income. The information about annual income was collected in Brazilian reals (R$) and converted to US dollars (US$) using the conversion rate of US$1 = R$3.25 (as of December 2016).

We continued our interviews with a sequence of four questions to appraise each participant’s understanding and perception of PAs. First, we asked participants to define ‘protected area’ and describe at least one of the goals of PAs. If participants defined ‘protected area’ as a place set apart by the government to protect nature (or fauna, flora, natural beauty or related descriptors) and/or to promote the sustainable development of natural resources, we considered the response as correct; otherwise, the response was incorrect (e.g., a place for future urban expansion). Second, we asked participants to name at least one of the PAs in Amapá. We used this question to make sure that participants were able to connect the concept of PAs with an actual PA. Third, we asked participants whether they supported the existing PAs in Amapá. This last question was closed and had three options: (1) yes, indicating the participant’s support for PAs; (2) neutral, indicating the participant having no defined position on PAs; and (3) no, indicating the participant’s lack of support for PAs. Finally, we ask participants an open question on the reasons of their support or lack of support for PAs. We grouped the reasons provided into categories defined posteriorly in order to facilitate the description of the results. Because of time constraints and due to logistical reasons, we did not replace those participants who failed to answer all of the questions in our interview.

Statistical analysis

Only the participants who responded to all of the socioeconomic questions and the first three questions about PAs were included in the statistical analyses. As a consequence, our final sample decreased from 740 to 615 interviews because 107 urban and 18 rural participants were excluded. Urban participants were excluded because they could not name a PA (42) and/or did not provide information about annual income (65). In contrast, rural participants were excluded only because they could not name a PA.

We used the χ 2 test of independence to assess whether there is an association between some categorical variables. Thus, we evaluated: (1) the independence between gender (males and females) and place of residence (urban area, rural outside PA and rural inside PA); and (2) the independence between place of origin (Amazonian and non-Amazonian) and place of residence. If the χ 2 test for independence was significant, then we tested the statistical significance of the difference between the observed and expected values in each cell to identify where the significance came from. In this analysis, we estimated the exact probability for each cell and its statistical significance with the Holm–Bonferroni correction method using the procedures described by Shan and Gerstenberger (Reference Shan and Gerstenberger2017). To compare the variation in the continuous variables (age, education and income) across places of residence, we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). If the ANOVA was significant, then we compared the means of pairs of places of residence using Tukey’s test. Finally, to simultaneously assess the effects of age, gender, education, income, place of origin and place of residence on the participants’ level of support for PAs, we used ordered probit regression. Because we had more urban participants than rural participants, we tested whether the results of the regression were affected by such differences. To do so, we selected randomly from our urban sample 122 urban participants and ran the regression again with only 244 participants (122 rural + 122 urban). Random selection of urban participants was done by using Microsoft Excel. We first generated random numbers for each participant, sorted the participants by the random number and then selected the first 122 cases. Stata 15 (StataCorp 2017) and Minitab 18 (Minitab 18 Statistical Software 2018) were used for all statistical tests.

Results

Among the 615 participants, 493 lived in Macapá and 122 lived in rural areas. Among the rural participants, 47 lived inside PAs and 75 lived outside of them. There is a statistically significant association between place of residence and gender (χ 2 = 25.2, df = 2, p < 0.0001), as well as between place of residence and place of origin (χ 2 = 16.8, df = 2, p < 0.001). In rural areas, we interviewed proportionately fewer females than males, but in urban areas, we interviewed significantly fewer males than females (Fig. 2). In rural areas outside of PAs, we interviewed more non-Amazonians and fewer Amazonians than expected (Fig. 2). On the other hand, more Amazonians and fewer non-Amazonians were interviewed in Macapá (Fig. 2). There were significant differences in the profiles of the participants when the continuous variables are compared across places of residence (Table 1). In general, participants from rural areas were older and had fewer years of schooling than urban participants (Table 1). The average annual income was higher in urban areas than outside of PAs (Table 1). No significant statistical difference in annual income was found when comparing participants living in Macapá with those living inside PAs or when comparing participants living inside and outside of PAs (Table 1).

Fig. 2. The percentage of participants by place of origin (Amazonian versus non-Amazonian) and by sex (male versus female) varied significantly across place of residence in Amapá, Brazil. PA = protected area.

Table 1. Age, years of schooling and annual income (in US$) of the participants who responded to all of the questions about support for protected areas (PAs) in Amapá, Brazil, vary significantly across place of residence.

Values for means that share a superscript letter are not statistically different (p > 0.05) according to the post hoc Tukey test.

ANOVA = analysis of variance.

Most participants (90.5%) supported PAs (Fig. 3), with a few participants showing no support or a neutral position (χ 2 = 908.0, n = 615, df = 2, p < 0.0001). Neutral participants were recorded only in rural areas (Fig. 3). The ordered probit regression model was statistically significant (χ 2 = 128.6, df = 7, p < 0.0001). When considering all of the explanatory variables simultaneously, only place of residence was statistically significant (Table 2). The negative coefficients for groups inside and outside of PAs mean that rural participants are significantly less likely to support PAs than urban participants. This general qualitative result holds when the ordered probit regression (χ 2 = 64.6, n = 244, df = 2, p < 0.0001) was run with the same number of urban and rural participants (Table S1, available online).

Fig. 3. Urban populations show a higher level of support for protected areas than rural populations in Amapá, Brazil. PA = protected area.

Table 2. Ordered probit regression shows that public support for protected areas in Amapá, Brazil, is explained by respondents’ place of residence, but not by age, gender, income, education or place of origin.

a Gender is for males compared to females.

b Income is the annual income in US dollars.

c Education is measured by the number of years of schooling.

d Origin is for people born in the Amazon compared to people not born in the Amazon.

e Place of residence is for rural outside protected areas and rural inside protected areas compared to urban areas.

The number of respondents who explained the reasons for their support or lack of support for PAs is 555, with 536 living in Macapá and 19 in rural areas. A total of 103 participants pointed out two or more reasons for supporting PAs. Biodiversity conservation is the major factor driving support for PAs in Amapá in both urban and rural areas, followed by providing goods and services to everyone, as well as control of deforestation and degradation (Table 3). Respondents who did not support PAs justified their position by stating that, in their views, PAs did not benefit people, they constrained the state’s economic development or they are not an effective policy to contain deforestation (Table 3).

Table 3. Major reasons pointed out by urban and rural respondents to justify their support or lack of support for protected areas in Amapá, Brazil.

Discussion

Our study provides a snapshot of the public support for PAs in new frontier regions in the Brazilian Amazon. We found that most of the participants (90.5%) support PAs, but such support varies according to place of residence. In general, support (>90%) is higher among people living in urban areas than among people living in rural areas (c. 50%). In contrast to previous studies, we did not find evidence that education, gender, age, income and place of origin have any influence on public support for PAs when analysed simultaneously. Biodiversity conservation and protection of natural ecosystems against deforestation and degradation are the major reasons why people supported PAs. In contrast, most participants who did not support PAs saw them as providing no benefit to people.

The only factor that significantly predicted the likelihood of a person supporting PAs in Amapá was place of residence, despite the profile differences found between our rural and urban populations. The difference between urban and rural populations regarding public support for PAs has been reported in the literature (e.g., Carrus et al. Reference Carrus, Bonaiuto and Bonnes2005, Triguero-Mas et al. Reference Triguero-Mas, Olomí-Solà, Jha, Zorondo-Rodríguez and Reyes-García2010, Byrka et al. Reference Byrka, Kaiser and Olko2017). The most common explanation for this pattern is that urban populations, on average, have more education and better incomes; thus, they are more aware of global environmental problems and are more likely to exhibit pro-environmental attitudes (Huddart-Kennedy et al. Reference Huddart-Kennedy, Beckley, McFarlane and Nadeau2009, Lo Reference Lo2014). In Amapá, urban participants had, on average, more years of schooling than rural participants, but the differences in income were not as sharp. However, when considered together with other variables in our regression model, education and annual income had no significant influence on public support for PAs. Bragagnolo et al. (Reference Bragagnolo, Malhado, Jepson and Ladle2016) suggested that the spatial variation in support for PAs is driven mainly by unequal distribution of the costs and benefits arising from conservation activities, with people living inside or near PAs paying most of the conservation costs while receiving fewer benefits. Unfair distribution of a policy’s costs, benefits and risks across population subgroups is an equity problem that seems to be common among countries where authoritarian governments set PAs using top-down approaches with limited participation from local rural populations (e.g., Dawson et al. Reference Dawson, Martin and Danielsen2018, Friedman et al. Reference Friedman, Law, Bennett, Ives, Thorn and Wilson2018, Martin et al. Reference Martin, Myers and Dawson2018). In contrast, the Brazilian legislation requires a consultation process to gazette new PAs, except for ecological stations and biological reserves. During the consultation process, the potential benefits of a PA to local and generally impoverished populations are explained and trade-offs are discussed (Palmieri & Veríssimo Reference Palmieri and Veríssimo2009). If the PA belongs to the sustainable use category, local populations receive benefits such as land-use rights, protection against land-grabbers and access to social programmes provided by governments, such as cash transfer mechanisms (Kasecker et al. Reference Kasecker, Ramos-Neto, Silva and Scarano2018). In addition, local communities continue to be engaged with management of a PA after gazettement. For instance, local communities can help design the management plans that will guide the PA’s management, as well as become regular members of the multi-stakeholder committees that oversee all of the activities in the PA (Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade 2014). Hence, if PA agencies had all of the resources required to implement PAs according to the legislation, conflicts with local populations would not be expected in the Brazil’s new forest frontiers. However, Dias et al. (Reference Dias, Cunha and Silva2016) demonstrated that the financial gap for implementing Amapá’s PAs is wide, indicating that both national and state governments have failed to invest sufficient resources for implementing the state’s PAs and thus fulfilling their obligations with local populations. It is possible that rural participants have a more nuanced perspective on PAs than urban participants, as indicated by their neutral and negative attitudes towards PAs, because their lives are more influenced by the decisions made by PA agencies. However, failure of the state to fulfil its commitments to local populations can exacerbate the notion that PAs do not benefit people in rural areas. Local-scale ethnographic studies could possibly uncover the social processes that explain the pattern that we have identified.

Because the urban population comprises 90% of the population of Amapá and because we found that most of the urban participants supported PAs, we can conclude that most of the population of Amapá considers PAs to be an important policy. We propose that such support is a consequence of the ambitious conservation agenda that has protected 72% of the state. The continuity of the public message that PAs are an important element of state prosperity by all dominant and rival political parties has possibly acted as a homogenizing factor, helping to shape a pro-conservation society in which people of different ages, genders, income levels, education levels and birthplaces share a positive view regarding PAs. Because political contexts are generally seldom evaluated in studies about public support for PAs (Bragagnolo et al. Reference Bragagnolo, Malhado, Jepson and Ladle2016, Martin et al. Reference Martin, Myers and Dawson2018), we suggest that they should be included in future studies.

Political context matters, and it can define the fate of the natural resources in new tropical forest frontiers. In these regions, decision-makers can broadly opt for two conservation strategies: proactive or reactive. A proactive strategy sets aside PAs before the expansion of human activities in a region. Thus, PAs face less opposition from local stakeholders, conservation costs are low and governments have enough time to foster a conservation-based economy that benefits and empowers local populations while directing the efforts and resources of the newcomers towards economic activities that are not detrimental to biodiversity conservation (Dias et al. Reference Dias, Cunha and Silva2016). In contrast, a conservation strategy is reactive when PAs are gazetted as a late response to human expansion in a region. Under such conditions, PAs are more expensive to establish and manage because they face strong opposition from stakeholders who benefit from forest degradation and exploitation and who usually control local governments and have a powerful influence on the national government. The Amapá experience shows that a proactive conservation strategy can lead to high public support for PAs at least among urban populations, even during an intense process of frontier expansion. This hypothesis can be tested by comparing public attitudes towards PAs across forest frontier regions that implement different conservation strategies. However, such a comparison needs a standardized research methodology, something that currently does not exist (Bragagnolo et al. Reference Bragagnolo, Malhado, Jepson and Ladle2016).

As with any study covering a relatively large area with low population density and limited logistics, our study has some limitations. First, we have not addressed all of the factors that can explain the variation of the population’s attitudes. Factors such as equitable management, trust in state agencies, governance models and benefits derived from PAs are some of the variables that can influence public perceptions regarding PAs. Second, our sample from the rural population was restricted to areas inside or around sustainable use PAs and has not included populations living near strict PAs and other rural settings not influenced by PAs. Finally, our sampling strategy was designed to provide greater understanding of public support for PAs across the whole population of Amapá. As a consequence, our methods are not suitable to providing a more nuanced perspective on the conflicts happening at the local scale within or around specific PAs. However, we believe that our study provides useful information on public attitudes towards PAs in a new forest frontier and that its results are solid enough to motivate further research.

We found that public support among the urban population is high for PAs in Amapá, a new forest frontier in the Brazilian Amazon, despite the recent and accelerated process of expansion in land-intensive economic activities and the fragility of the conservation agencies operating in the state. However, in spite of all of the conservation efforts of recent decades, Amapá is still far from becoming a conservation utopia in which synergy between human prosperity and biodiversity conservation fostered by effective governance leads to high levels of social inclusion and equity. In fact, we found that rural populations are less likely than urban populations to support PAs, possibly signalling that expectations regarding the benefits and rights associated with conservation have yet to be met by the underfunded PA agencies. We suggest that monitoring the attitudes of rural populations living inside and near PAs is the most effective way to track changes in levels of public support for this type of conservation policy during periods of accelerated frontier expansion in tropical forests.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892919000262

Acknowledgements

We thank our research assistants (Elivânia de Abreu, Evellyn Façanha, José Neto, Geison da Silva, Paulo Gibson, Rafael Furtado and Wellinson Severino) for their help with collecting all of the information for this paper, as well as all of the people who shared their views on PAs with us. We are grateful to Luis Barbosa for his help with the map and Liza Khmara for her comments. Helenilza Ferreira Albuquerque Cunha thanks the University of Miami for the support of her post-doctoral training. We thank the editors (Nicholas Polunin and Johan Oldekop) and three anonymous reviewers for all of their comments and insights on the previous versions of the manuscript.

Financial support

José Maria Cardoso da Silva was supported by the University of Miami and the Swift Action Fund.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal do Amapá.