In the post-1945 era, extensive welfare systems developed on both sides of the Iron Curtain, with welfare states taking on a number of key roles related to regulating the labor market, distributing goods, imposing social order, stimulating the economy and ensuring support for the ruling class.Footnote 1 In eastern Europe, the shared experiences of economic underdevelopment, occupation, destruction, and death called for efficient and comprehensive welfare-state solutions. While eastern and western Europe shared these experiences to some extent, the new communist states that emerged in eastern Europe after World War II confronted additional problems related to their agriculture-based economies, war-ravaged infrastructure, and the fabric of society, which suffered far greater damage than their western counterparts.Footnote 2

The aim of this article is to stress the key significance of the welfare state to the communist vision of social development, which—irrespective of its actual realization—included equal access to welfare benefits and equal rights for women by definition. Poles often raised the issue of state welfare, using the same term and demanding various benefits such as employment, housing, consumer goods, leaves and holidays, and medical and institutional care. This was the case both before and after 1989, with people in power frequently invoking the welfare state to pursue their own agenda, well aware of the persistence of societal desires for welfare policies, state protection, and intervention. In this article, I would like to illustrate the complexity of the welfare state project using Poland as an example, and indicate the various types of compensation offered and the civilizing- and reproduction-related roles played by the communist state. My analysis of the communist welfare state focuses in particular on benefits for working mothers such as extended paid leave and institutional care for children. This area of policy—centered to a large extent on addressing the problem of the “double burden” of work inside and outside the household—provides unique insight into the advantages and disadvantages of communist social policies. I will discuss the obvious advantages of such benefits, but also address the issue of the natalist goals of welfare policies, which did little to help working mothers.

It is worth pointing out that one of the chief motivations for implementing an extended welfare state in the 20th century was to implement a natalist policy. As David L. Hoffman shows, in interwar Europe and the USSR, the authorities’ attention was focused on depopulation, which resembled the 19th century policies prompted by falling fertility rates and worries about national decline.Footnote 3 One widely adopted assumption was that an increased income and a greater presence of women on the job market resulting from industrialization must lead to a decrease in birth rates.Footnote 4 In the case of communist Poland, the post-Stalinist state authorities, focusing on fertility rates, expanded maternity benefits and extended leave for women, while failing to take serious measures to improve institutional childcare.

I argue that the welfare state in eastern Europe was a central factor that legitimized and delegitimized communism, becoming in fact a social contract based on the remarkable expansion of benefits. Calling for industrialization and equality at the outset, Stalinist authorities introduced welfare policies that increased the workforce by enabling women to work outside the household. However, due to the poor operation and shortages in welfare programs such as underdeveloped institutional childcare, in the last two decades of communism the other welfare benefits—paid leave, for example—became very popular, considerably decreasing the number of women working outside the home, a fact that contradicted the officially-proclaimed policy of gender equality. Fully aware of the restrictions of post-Stalinist consumerist policies and shortages, mothers—both blue and white-collars—eagerly awaited institutional help, even the kind that could considerably weaken their position in the labor market. As the example of Poland shows, women benefited from the communist welfare state to a certain extent, but at the same time, they became its hostages.

In recent years, scholars working on post-war history of eastern Europe and the Soviet Union directed much attention to the quality of life under communism. Few of them, however, addressed issues related to the welfare state, focusing instead on “socialist consumption,” understood as one of the effects of de-Stalinization.Footnote 5 Until the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, the Soviet regime under Nikita Khrushchev followed a policy of peaceful coexistence, centered on competition between east and west for the best social and economic solutions. Susan E. Reid argues that “the domestic realm was crucial to this exchange of global political significance, for a third front had joined the arms race and the space race—the living-standards race.”Footnote 6 The western model of modernization represented a challenge to Soviet society and the material component in the fight for supremacy, which became clearly evident during the American National Exhibition in Moscow of 1959. According to Anne Gorsuch, who analyzed Soviet films about tourism, the communists, torn between approval and fear of new behaviors, responded to the western economic miracle by domesticating selected elements of the western lifestyle.Footnote 7 As a result of this “consumerist turn,” demands for consumer goods and affluent lifestyles started to be voiced in east European communist states, giving rise to new aspirations and consumer behavior, as well as to new definitions of “modern men” and “modern women.”Footnote 8

Once the welfare state became one of the foundations of communism, welfare services, representing the basis of a social contract between society and the authorities, should have been considered a basic, common good rather than a “luxury” consumer good. The importance of legitimization by the welfare state was evidenced by the fact that all basic benefits were provided through the workplace, with their quality and availability closely dependent on the importance of a given employer to the communist economy and—consequently—on its current standing in the hierarchy of distribution. Given the structural defects of central planning and the rampant shortage economy, that meant that such services were often desperately sought after or available only to the chosen few employees and companies, and basically considered no different than other luxury consumer goods.Footnote 9 The relationship between welfare benefits and consumption became even stronger when rare goods, such as foreign alcohol, cigarettes, sweets, or western clothes started to be used as means for jumping the queue and gaining access to state welfare—hospital beds, holidays, flat allotments, and kindergartens. This article seeks to present the thesis that communism became delegitimized not only because of the deficit in consumer goods, but above all as a result of the poor operation and resulting shortages of the communist welfare state.

Sources

Communist officials encountered a number of difficulties in their efforts to formulate welfare policies. These included cultural assumptions about women and mothers, political exigencies, postwar social and cultural shifts, and a struggling economy. To analyze the specific meaning of welfare policies that targeted women, I look at contemporary sociological research on female employment, childcare facilities, and maternity leave.Footnote 10 Apart from providing opinions and diagnoses toeing the party line, sociologists tended to challenge a number of established norms and solutions, and often exposed weaknesses of the communist gender-equality project as it unfolded in workplaces and welfare-state institutions.

In addition to sociological research, I use press sources that explore the roles of women within the welfare state.Footnote 11 The contemporary press provides unexpected insights into our understanding of state welfare under communism as it exposes attempts to redefine the welfare state, conditioned by the “demographic panic” of the late 1960s and early 1970s that was prevalent throughout eastern Europe. It is worth noting that demographers, journalists, and state dignitaries were not unanimous in approaching questions of demography, taking sides in a heated debate between the followers of a liberal approach, similar to that used in France or Sweden, and proponents of solutions modeled after Bulgaria and Romania. The press debates of the day reflected the cultural and generational changes of the 1960s, which—despite preventive censorship—could still surface in the communist press. Before the 1970s, gender equality (and its limits) in Poland was a welcome topic to discuss in public. After the emergence of the feminist movements and the sexual revolution in the west, however, it became clear that the communist states no longer represented the forefront of “gender equality.”

In addition to studying influential press titles such as the weekly Polityka, I also looked at women's magazines, including Przyjaciółka, Kobieta i Życie and Zwierciadło, all of which played a unique role in communist Poland, not unlike the role of national women's organizations.Footnote 12 These magazines had circulations of millions of readers and enjoyed great success. They acted both as a conduit for the Party's policy towards women and a voice of women themselves—the female editors and readers. As suggested by an extensive review of issues published in the 1960s, the opinions of the contributors cannot be reduced to the state agenda. The views expressed in women's magazines were very diverse; they often contradicted the official party line and criticized systemic solutions that did not take into account women's interests. Though there were exceptions, I believe that these popular periodicals could be considered vehicles for the opinions of many active women advocating gender equality. As working women themselves, the female editors of these popular magazines were more familiar with the challenges and obstacles facing professionally-active mothers than their male colleagues writing for the mainstream “male media.”

Combining different points of view, presented in sociological papers, works of male journalists, demographers and politicians, as well as contributions from female journalists printed in women's magazines, allows me to address the state welfare issue from multiple angles and illuminate a range of perspectives on the domestic and professional roles of women.

Communist Welfare

The Second World War and post-war economic development contributed to the success of the welfare state model, adopted first in the United Kingdom, then in other European states. Its most rapid expansion was recorded in the 1960s and 1970s, with Scandinavian countries seen as model exemplars. After 1945, different components of the welfare state were implemented on both sides of the Iron Curtain—in the Federal Republic of Germany, Sweden and the UK, but also in the Soviet Union, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), Poland, and Hungary. The same term “welfare state” (państwo dobrobytu), coined by the British, was challenged by the communist agenda, as it invoked the much-criticized capitalist social and economic system that, according to the communist ideology, gave rise to substantial social inequality. At the same time, the sternest opponents of the western model admitted that the communist state had to offset the negative effects of industrialization, including difficulties experienced by new industrial workers and their families. Consequently, post-war publications often used the term państwo socjalne or państwo opiekuńcze (“social state” or “protective state”) which borrowed from the German notion of Sozialstaat and allowed socialist authors to differentiate between the positive communist model and the dysfunctional capitalist welfare state.Footnote 13

Despite the efforts undertaken in communist countries to differentiate the eastern welfare model from its western counterpart, it seems that there were more commonalities than differences between them. First and foremost, welfare was an important component of what is called “modernity.” As the Soviet example shows, modernity was by no means a strictly western phenomenon, connected only with capitalism and liberal democracy.Footnote 14 In present-day discussions on the historical meaning of the term, scholars suggest that non-western countries not so much aspired to or copied modernity as co-produced it, mainly by reinforcing the nation-state, implementing social shifts, and insisting on (at least rhetorically) political participation.Footnote 15 It is worth adding here that in post-1945 eastern Europe, the term “modernity” signified both top-down efforts of state and Party, such as investments in industry or housing, but also bottom-up developments, like the wish to “be modern” rooted in mass culture and manifesting itself in everyday life in style and consumption.Footnote 16 Arguably, the convenient use of new goods and benefits provided within the welfare framework, such as organized holidays, department stores, and kindergartens, which were supposed to be equally accessible, counted as “being modern.”

In trying to identify the specifics of communist welfare, one should point to the dynamics of change characteristic of countries such as Poland, Hungary, or Czechoslovakia, which in the 20th century experienced a number of political and socio-economic transformations. According to Tomasz Inglot, a distinctive feature of the east European countries was the “emergency welfare state,” understood as an instant reconfiguration and adjustment to internal crises and external circumstances. In comparison to western governments, the communists perfected and deepened the practice of implementing social benefits as tools of policing societies, which could be seen in alternating expansion and retrenchment of welfare policies.Footnote 17 “Emergency welfare” was especially apparent in Poland, a country that had been experiencing frequent and violent changes.

Periodization

Given the nature of the “emergency welfare state” as described above, the evolution of communist welfare in Poland can be divided into four phases corresponding to major socio-economic crises: Stalinist welfare, the post-Stalinist years, the 1970s, and the 1980s. They represent four distinctive periods separated by important watershed moments: the end of WWII, the Thaw of 1956, the December 1970 revolt, and the creation of Solidarity in 1980. Each of these breakthroughs led to short-lived attempts to legitimize the system. Lasting for up several years, such efforts mostly focused on reforming welfare, usually through the introduction of new benefits for selected groups, though often to the detriment of working mothers.

The first phase of communist welfare should be associated with the end of war and the implementation of pre-war Soviet Stalinism in the realities of eastern Europe.Footnote 18 During the Stalinist era (1947–1954), official slogans advocated full employment, social advancement of the working class, and improved quality of life for workers. Fearing the social aftermath of an industrial action in the course of the Six-Year Plan (1950–1955), the Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza (Polish United Workers’ Party, or PUWP, established in 1948) turned their attention to welfare at state-run heavy industry plants, focusing on topics such as the organization of the workday, remuneration and job guarantees, worker safety, mass leisure, and health insurance. In countries such as Poland, Hungary, or Czechoslovakia, the Stalinist authorities used inequalities in welfare access as an instrument of class politics, with substantial privileges for certain categories of employees, especially heavy-industry workers.Footnote 19 That was often at the expense of female workers, who were employed in extremely difficult conditions and left without the protection of adequate welfare services.

Initiated by multiple events such as the secret speech condemning Stalinism by Nikita Khrushchev, the sudden death of Bolesław Bierut, the Secretary General of the PUWP, and the tumultuous workers’ protests in Poznań, the year 1956 and the period known as the Thaw was the beginning of the second phase of welfare in Poland.Footnote 20 Because of the “consumerist turn,” the Thaw inspired hopes that lasted several years—hopes that the daily lives of ordinary people could change through improved welfare and consumption. A newly appointed leader, Secretary General Władysław Gomułka, announced a series of welfare reforms to complement de-Stalinization, including common housing (mostly for families) and a pension reform (for industrial workers). Selective welfare dominated in the period after 1956, pushing other topics, including benefits for working mothers, childcare, and family benefits, to the background.Footnote 21 By the early 1960s, as Inglot suggests, social policy “fell short of a major breakthrough that would indicate a permanent shift toward a more generous socialist welfare state, as expected and demanded by many social policy experts, labor groups, and the growing masses of benefit recipients.”Footnote 22 The shortages in state welfare corresponded with the official rhetoric in the post-Stalinist era, which contrasted socialist “rational consumption” with exuberant “western consumption.”Footnote 23

The focus on social needs was more evident during “Gierek's Decade” (1970–1980), the third phase of Polish state welfare named after Secretary General of the PUWP Edward Gierek. In the first half of this decade, the demands for better living standards, improved consumption, and more extensive social benefits were met to a large extent, chiefly thanks to substantial loans contracted from capitalist states. The Five-Year Plan (1971–1975) prioritized access to consumer goods and services, better housing, job guarantees for young workers, and shorter workweeks in the future.Footnote 24 All of these goals could be considered part of an official response to the protests in December 1970, which—after the Poznań protests of 1956—became the next wave of social discontent, this time inspired by the port towns of Gdańsk, Gdynia, and Szczecin.Footnote 25 Once the revolt had been thwarted, the new government, led by new Secretary General Gierek, who had been appointed because of Gomułka's lack of popularity following the December 1970 events, announced that the transition from post-war communism to consumption-based communism would finally be realized.Footnote 26 Unlike with previous central planning of the 1950s and 1960s in Poland, economic growth was primarily supposed to reflect improved standards of living, as proven by new goods such as foreign products, holidays abroad, or improved availability of housing and cars. For working mothers, this meant chiefly expanded leave and family benefits. It became increasingly evident that welfare was the basis of the social contract that made peaceful communist rule possible.

Consumption and credit were the final straw, causing the inefficient communist economy to struggle even more and inaugurating in the 1980s the last phase of communist welfare. The growing inequality sparked discontent, which culminated in August 1980, subsequently leading to the creation of the Solidarity movement. During the strikes, workers had several demands (including the famous 21 demands issued by the workers of the Gdańsk Shipyard), the majority of which addressed the poor operation of the welfare state, in particular, the unequal access to welfare benefits.Footnote 27 Signing the Gdańsk Agreement and establishing Solidarity as an independent trade union provided only a short respite. One concession made to the workers involved the demand for the extension of paid maternity leave. In the end, the authorities decided to use force, knowing all too well that they could not meet all of the August demands. The declaration by the communists of martial law in Poland (1981–1983) was a violent reaction intended to pacify the growing movement of social disobedience, which secured relative order for a while. By the mid-1980s, however, the communist authorities faced a protracted and deep crisis that could not be alleviated in any way. Constant supply shortages, rationing of basic foodstuffs (including the much-hated food stamp system), lines forming in front of shops, high prices, poor investments, and growing foreign debt that forced Poland to export goods in short supply on the domestic market, all drove down the quality of life and caused the general social sentiment to plummet.Footnote 28 In particular, elements of the welfare system that had developed since the 1950s—including mass employment, pensions, healthcare, public housing, and leisure—malfunctioned in the struggling economy as an apparent side-effect of ineffective industry, trade, and agriculture. Given that Poles traveled more and more often to countries behind the Iron Curtain, the communist authorities could no longer maintain the illusion that the Polish welfare state was better than the western one.Footnote 29

Contradictions of Stalinist Policies

The Stalinist regime made efforts aimed at a greater inclusion of women in the workforce, a quest often paired with a call for institutionalized childcare. Undoubtedly, such calls represented a response to a genuine need present in society. Many mothers and wives lost their partners and breadwinners during the war. Left to fend for themselves, these women had to take up temporary jobs or take their work home, while simultaneously bringing up children. After the war, when many mothers found themselves in need of state aid, European societies started to consider them “wedded to welfare.”Footnote 30

The Six-Year Plan called for collectivization and industrialization, but also for equal rights for women. Unlike in the interwar period, communist authorities pursued a well-publicized, top-down gender policy of “equality through protection,” to borrow a phrase from Małgorzata Fidelis, with the state actively supporting female employment, career advancement, and access to new professions—a solution that made communist states stand out in Europe.Footnote 31 Fidelis notes that the Stalinist slogan that women can do men's work was not really intended to fight gender stereotypes.Footnote 32 Therefore, Stalinist gender policy was not meant to renegotiate traditional roles—and if such renegotiation occurred in families in which women worked outside of home, it was unintentional rather than driven by state gender policies. At the same time, the official state position was that female employment and housework were difficult to reconcile, and that the state should secure welfare services for working women, making their lives easier than before the war (or better than in the capitalist states). This would allow them to combine their new identities as qualified industrial workers, in alternating shifts, with their traditional roles as mothers, wives, and homemakers.

In 1949, one year before the official launch of the Six-Year Plan, the women's weekly Kobieta published the following text, conjuring visions for the coming years: “The [Plan's] watchword is freeing women from unnecessary burdens. … in the morning, women will lead their children to daycare or kindergartens located in the center of their housing colonies, and shop in cooperatives and department stores … just around the corner; local bathhouses, laundries, and canteens will relieve them of the burden of housework.”Footnote 33 The text suggested that the position of working mothers had already changed or was about to change in the near future. Nothing could be further from the truth. The deficit was even more pronounced in newly built urban districts, where working mothers were a common sight and care facilities had not been built yet. Nowa Huta, the flagship communist project, was affected by a shortage of kindergarten and daycare centers, meaning that mothers had to leave their children at home unattended, once again witnessing “the gap between socialism's welfarist vision and its Stalinist reality,” as Katherine Lebow described it.Footnote 34

However, the legacy of Stalinism cannot be judged using unambiguous quantifiers. There is no doubt that the industrialization under the Six-Year Plan changed the lives of many women, producing both clear benefits and numerous negative side effects. For many young women, the prospect of employment was a possibility to make their own choices and advance up the social ladder. This change was reflected in social behaviors and expectations, including new demands upon the state.Footnote 35 Migration to urbanized areas provided new opportunities for women from small towns and villages, including improved living conditions and longer life expectancy.Footnote 36 The compensatory, charitable role of welfare in times of Stalinist industrialization was the most evident in healthcare. The system of obligatory and costless medical checkups kept working women substantially healthier.Footnote 37 On the other hand, the negative side effects of Stalinist policies were numerous, including overwork, severed social bonds, fear related to frequent persecution and surveillance at the workplace, and, more importantly, substitution of traditional working-class values and hierarchies with the new ethics of “exceeding production targets” and “work competition.”Footnote 38 Some adverse effects of Stalinist industrialization affected women more than men. Given the division between the dominant heavy industry (which was well financed, on the assumption that such work was more difficult and more valuable to the state) and the less important light industry (employing mostly a female workforce), women were deprived of better working conditions, as most improvements were allocated to “masculine” priority companies.

Status of Female Waged Work

What started during the Six-Year Plan continued later on, during the second phase of Polish welfare, when consumption and living conditions started to feature more often in the public discourse. The low priority of light industry in time led to deficits in clothing and food sectors, and forever defined the vast gap between the financial status of working women (textile workers) and men (miners, steelworkers).Footnote 39 Małgorzata Mazurek notes that in the beginning of the 1970s working conditions in underfinanced “light industry” factories, staffed mostly by women, were not unlike those in 19th century factories, with workers enjoying no social benefits.Footnote 40

With its roots in Stalinist ideology, the structure of expenses and investments favored men and masculine-dominated industries—and women felt the consequences in their private lives. In the 1960s, men (both white-collar and blue-collar workers) earned the highest salaries, followed by female white-collar workers. The lowest-paid group was blue-collar working women, even though they needed state aid the most. In this way, the social outcome of the growing female workforce was partially neutralized by the common assumption that careers of wives and mothers were supplemental.Footnote 41 Even though women earned wages, they were usually more economically motivated to resign from work. Contrary to the official propaganda, these experiences were quite similar to those of women in capitalist states, no matter how much the communist state tried to distance itself from such comparisons.

The image of women at work was driven not only by state propaganda, but also by the way both the Stalinist and post-Stalinist political elites saw working women. Despite official statements on gender equality, communist decision makers—almost exclusively men—considered women-centered issues secondary and only important in the context of industrialization and improved work efficiency.Footnote 42 This was especially evident during International Women's Day, when simple workers received flowers and gifts during the staged, state-organized celebrations, which were supposed to mask welfare shortages and mobilize women to continue working efficiently.Footnote 43 The beginning of the second phase of communist welfare, when the social role of women was considerably redefined, serves as another example of state-socialist policy. A careful analysis of Polish archival data and women's press suggests that in 1956–1957, both the communist Party and the League of Women saw a temporary reduction in female employment as a solution to unemployment, an idea that found its way to the new economic plan of 1956–1960.Footnote 44 The above example is evidence to the fact that female organizations sought to control and monitor the implementation of gender equality, but because their role in eastern Europe remained ambiguous, they sometimes passed over or openly supported solutions that disadvantaged professionally active women.Footnote 45 Judging from this example, the role of the League of Women was similar to that of the women's press—both sought to influence public opinion and could offer suggestions to the authorities, but were also incapable of effectively opposing “male-oriented” solutions unfavorable to state-professed gender equality.

Challenges of the “Double Burden”

Despite the discrepancies of the political elite, the new urban generation in the second phase of communist welfare saw female employment as a norm.Footnote 46 The development of secondary and tertiary schools, in particular in the 1960s, made educational advancement more feasible for women. Improved education, paired with high employment in industry, led to a sudden and unprecedented surge in the number of working women. According to official data, only a dozen or so percent of married women (outside of agriculture) worked for wages in the early 1950s. By the end of the decade, the figure increased to one in three. In the mid-1970s, three-fourths of these women worked outside the home.Footnote 47 In the context of these changes, the problem of reconciling housework with work obligations affected women from different social backgrounds, not only young, unmarried, working-class girls. The combination of increased female participation in work outside the home and women's active involvement in homemaking resulted in what contemporary specialists referred to as the “double burden.” Young women from the cities were in a particularly difficult position, as they usually did not give up their traditional roles as wives and mothers while simultaneously taking on new challenges. Evidence suggests that while women went into employment for financial reasons, they were commonly expected to work “two shifts” and juggle their work obligations and home lives, irrespective of whether they were professionals or blue-collar workers.Footnote 48 Apart from new professional groups, dissatisfaction was also common among Polish female blue-collar workers, who were not only poor, but also—as the studies suggested—almost entirely deprived of free time.Footnote 49

According to source materials from the 1960s, new technologies introduced into the household by means of “socialist consumption” were the official answer to the problem of the “double burden.” Commentators, including contributors to the women's press, argued that modern household appliances would free women from excessive household duties. Technology, however, was a double-edged sword, because as its complexity increased, women had to spend more time using and servicing it. Susan Reid raises another important point on the ambiguous role of technology. She argues that post-Stalinist communist states gained new ways of controlling the population by introducing new consumption models, a departure from the Stalinist management style and a “dispersal of authority to a range of discourses, institutions, and regimes of daily life and personal conduct.”Footnote 50 I am not entirely convinced that the expansion of new technologies and professional advice should be interpreted directly as a new means of imposing discipline on the private lives of east European citizens. If so, such “disciplining” affected society only to a limited extent comparable to that in the west, which also became increasingly dependent on household technology. The pleasant private life based on technology, enhanced consumption, and modernization of the household in the 1960s and 1970s was supposed to stimulate the individual towards personal fulfillment while simultaneously discouraging citizens from taking part in public and political actions.Footnote 51 This was especially important for working women, whose double burden was a major source of frustration. That, coupled with poor welfare services for mothers, was a truly explosive combination.

From Women's Issues to Mothers’ Issues

The technological change coincided with a mental shift that depreciated the value of professional female work in favor of the more traditional roles of mothers and housewives. In selected media of east European communist states, public debates about gender identity, women's roles and rights within the welfare state continued to be rich and diverse throughout the 1960s. In the context of the technical, consumption-oriented turn to privacy, however, the calls for gender equality at work, though expressed as recently as in the 1960s in Poland and Czechoslovakia, faded into the background in the early 1970s. The post-revolutionary communist regimes, as Padraic Kenney points out, left “the private or social sphere alone, and in women's hands.”Footnote 52 The modern woman of the early 1970s was no longer a blue-collar worker or a teacher—she was first and foremost a housewife, devoting most of her attention to the family.

The shift overlapped with the beginning of the third welfare phase in Poland. The role of women in society and the economy was discussed in detail in a resolution adopted by the 6th Congress of the PUWP in December 1971, according to which “welfare institutions should be better tailored to women's specific positions.” The resolution also stressed that paid and unpaid maternity leave should be extended, and that the new social policy should commit to “helping families.”Footnote 53 This meant that for the first time since the end of Stalinism, the Party made women's issues a matter of top importance, simultaneously announcing a shift of focus, as housework dominated over waged work. From now on, critical studies of gender roles, common in the 1960s, were rarely published and, as Fidelis rightly observes, women's issues were discussed “primarily in the context of family.”Footnote 54 In tandem with these trends, in early 1973, Trybuna Ludu, the main Party daily, renamed its regular column that discussed women's issues from Sprawy kobiece (“Women's issues”) to Portret matki (“Portrait of a mother”), further illustrating the shift in the public discourse about women's role in society.Footnote 55

It is important to address the reasons why communist authorities redefined women's issues. It seems that the workers’ rebellion of December 1970 had no direct impact on the conservative turn in gender discourse—the change, however, may have been triggered partially by the Łódź strikes of female textile workers, which took place in February 1971 within months of the crucial 6th Congress of the PUWP.Footnote 56 The female textile workers, who prevailed in the city's workforce, were desperate, suffering from 19th-century working conditions, low salaries, while being additionally burdened with household work and near-daily lines for food. The Łódź strikes were mass protests, a consequence of the welfare shortages in light industry, with dramatic negotiations accompanied by frequent public addresses. Even though they never took to the streets, the female workers made a strong impression on government representatives. The communists, as Kenney argues, did not know how to deal with the fact that striking textile workers took advantage of their public image as mothers and breadwinners, and were afraid to fight “female protests” with tactics employed against the “male strikes” of December 1970.Footnote 57 Backed into a corner, the authorities soon announced that food prices would not go up—something even the December protesters had failed to achieve.

The female rebellion of February 1971 and the 6th PUWP Congress brought to light a salient feature of communist gender equality policy. At the very moment women gained a foothold in the workplace and tried to reclaim power through an effective strike, the state-sanctioned pressure to return women to traditional gender roles intensified. The textile workers’ strike took place against a backdrop of developments that confirmed women's growing status in the public sphere. For the male authorities, however, there was no need to encourage Polish women to sacrifice their status at home for the sake of a job, as was the case in the Six-Year Plan. New jobs in the public sector meant that the number of employed women continued to increase in the early 1970s, but the labor market simply had no more use for as many new employees as in the Stalinist years. Another important factor was male anxiety about losing the dominant role in society. Men and women competing for the same jobs, as well as traditional expectations related to housework, triggered the sentiment. The Secretary General Gierek himself had little understanding for changing social roles and emancipation, promoting the traditional idea of a male as the head of the family—an image he adopted for himself in the media.Footnote 58 Mieczysław F. Rakowski, editor-in-chief of the weekly Polityka (and the last Secretary General of the PUWP in the late 1980s) noted in his diary that Gierek was a man raised by a coal miners’ family, who idolized the local, traditional, petty bourgeois families.Footnote 59

Boosting Birthrates

Social anxieties were exacerbated by the gravest of arguments—that of declining birthrates. Although Poland had the highest national post-war birthrate in eastern Europe after Albania and the USSR, this rate declined in the late 1960s. According to the 1970 census, 57% of married women living in cities and 36% of married women from rural areas had no more than two children, making the 2+2 or even 2+1 family the new urban standard. In response, Polish male demographers and journalists called for reintroducing of the 2+3 model through extraordinary measures that they proposed to borrow from communist neighbors.Footnote 60

By the mid-1960s the drive to control reproduction became a salient feature of communist regimes in such countries as Romania, GDR, Hungary, Bulgaria and Poland.Footnote 61 The debate also raged on the streets.Footnote 62 Using the falling birthrates as an excuse, in 1966–1973 Romanian, Bulgarian, and Hungarian communists restricted female reproductive rights.Footnote 63 In Poland, where no substantial changes were introduced to the abortion legislation, a peculiar shift took place in the official rhetoric, with some commentators revealing their nationalist anxieties. It appears that the “demographic panic” in Poland resulted partly from the increasingly nationalist rhetoric observable in the 1960s, with its culmination in the anti-Semitic party propaganda of 1968.Footnote 64 Furthermore, the dominant moods stemmed from society's rather conservative views on the role of women and the meaning of family, reinforced by the highly influential Catholic Church. It is also noteworthy that the gender aspect of the media message was highly visible. A large number of male feature writers—both communist and Catholic—wanted to stimulate birthrates by taking jobs away from young women of reproductive age and mothers with several children.Footnote 65 Working women were right to note that men in power lacked empathy.Footnote 66

The anxieties surrounding deteriorating birthrates led to renewed discussion about welfare services for women, now targeted at improving fertility rates rather than at workforce efficiency, as was the case in the Stalinist period. Turned into crude instruments, the welfare services were no longer supposed to raise the quality of women's lives. The communist state's backtracking on the issue of gender equality, including the pressure on women to become mothers and housewives, directly affected the welfare model of late communism, chiefly through extension and popularization of maternity leave at the expense of childcare policies.

Daycare: Welfare or Luxury?

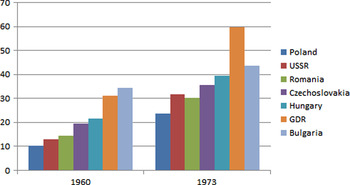

The very availability of care facilities slightly improved at the beginning of Gierek's decade, but the economic crisis of mid-1970s halted this positive trend. The baby boom of the late 1970s additionally contributed to the childcare deficit, and the demand for kindergarten and daycare places was never met in full during communist times, barring a few cities with somewhat adequate kindergarten facilities.Footnote 67 Demographers and social policy experts were aware of this shortage—when comparing Poland to other communist states, they couldn't help but notice that Polish working mothers that wanted their children to attend a kindergarten or a daycare were worse off than their counterparts in other countries of eastern Europe. In 1960, the percentage of Polish children in daycares and kindergartens was at an abysmal rate of 10% of all children, nearly three times lower than in Bulgaria and the German Democratic Republic, who were at the top of the classification, with 34% and 31%, respectively. In 1973, the absolute number of children in care facilities increased, but Poland was still last among east European countries included in the ranking (with 23%). GDR, the leader, boasted a rate of nearly 60% of all children in care facilities (Figure 1).Footnote 68

Figure 1. Percentage of children in kindergarten and daycare in eastern Europe.

As the supply of available spaces at child care facilities never met the demand of urban dwellers, every now and then, the press would issue an appeal posing a dramatic question: “What am I supposed to do with my child?”Footnote 69 Przyjaciółka suggested that Polish families often had to take over the duties of the communist welfare state: “… We women are constantly juggling our ‘double shifts’ at work and at home. … I shudder to think what my life with my three kids would be like without my dear granny. …”Footnote 70 The lack of adequate services stimulated a second economy of sorts, as women from wealthy families hired expensive nannies to continue to work professionally.Footnote 71 Other mothers used the “daycare underground,” a network of unregistered, costly facilities run by unqualified staff. Newspapers were full of classified ads offering such services.Footnote 72 In 1975, the daily Życie Warszawy reported that desperate mothers brought their children to work, and explained themselves to their administrative staff by saying: “Do as you please, I have nowhere to take them.” Some employers, understanding the realities of raising a child in Poland, allowed the kids to stay—illegally—in company clubs.Footnote 73

In rural areas, the lack of child care facilities was seemingly less problematic, as village women tended to be less professionally active than their urban counterparts and did not want to let their children venture outside the boundary of the family plot.Footnote 74 Given the ongoing economic, social and cultural changes affecting the Polish countryside, however, calls for universal kindergarten education were heard increasingly often. Rural kindergartens worked half-days and were understaffed, often with underqualified personnel. The most popular care facilities in such areas included temporary daycares open during periods of intensive fieldwork. Partially because of the shortage in childcare facilities, the number of fatal accidents involving children (related to drowning, road accidents, and fires) was much higher in rural areas than in the cities.Footnote 75 In addition, welfare-state services for mothers and children fitted into the more general idea that “civilized” behavior (tidiness of dress, personal hygiene, pleasant interior decoration, or reading habits) could be somehow cultivated—a rhetoric that was not unlike the Soviet propaganda of the 1930s or post-war Stalinism.Footnote 76 The housewives themselves were also more open to modernization, being often portrayed in female press as more enlightened than their farmer husbands or—as Sheila Fitzpatrick noted in her studies of Stalinist Russia—as the forefront of social change.Footnote 77 Since they took care of their children, they interacted with the change-making welfare institutions on a daily basis.Footnote 78 Communism, therefore, had potentially strong reasons for wanting to expand institutionalized childcare in rural areas, as it would represent a positive driver of change in conservative behaviors. But, for reasons discussed above, the authorities saw it differently, believing that maternity leave was the answer to all problems of working mothers.

Mothers on Leave

In late 1960s, unpaid leave was extended to 12 months for women raising small children, and in the first half of the next decade, to 36 months. Apart from the three-year unpaid leave, which was exceptionally long compared to other east European states, working mothers—both white- and blue-collar—had the right to go on a fully-paid maternity leave lasting from 16 (first child) to 28 weeks (multiple birth). They could also be excused from work if their children fell ill and—as of mid-1970s—were entitled to modest family benefits (in the best-case scenario, equal to about half of the salary for a mother of three on unpaid leave) or could elect to work part-time.Footnote 79 Given the above changes in labor law, Polish women who chose to take advantage of the long leave could stay out of work for as long as 40 months. In my research, I did not encounter any overt criticism of this solution—it seems that in the context of other problems the leave attracted neither positive nor negative sentiment, being considered an extra loophole to be used in certain circumstances.Footnote 80

In light of other, more passionate debates, such as those concerning alimony collection, retirement, disability payments, youth education, social aid for poor women, adoption, orphanages, the need for additional places in kindergartens and daycares, housing conditions, and availability of service points such as laundries and sewing houses, the issue of maternity leave seemed to be of secondary importance. Female blue-collar workers, who were usually less well off, were more interested in lowering the retirement age and introducing the same benefit rules for blue- and white-collar workers, as the latter enjoyed much privilege in this respect. A more favorable reception and more comments awaited the mother-centric reform of 1974, which introduced changes in family benefits and the much-praised Alimony Fund, designed to facilitate collection of child support from fathers and improve the difficult financial situation of single mothers.Footnote 81

Official support for a welfare state that reinforced traditional gender roles in the workforce can be seen as an attempt to deal with women's demands from below—including specific calls for more kindergartens and daycares and demands of striking workers fighting for improved benefits and better working conditions. According to Mazurek, strikes of the poor, underfinanced Łódź textile workers “should be analyzed not only as a call for a better politics of consumption, but more broadly, as a demand for implementation of the socialist ‘welfare state’ in their private and professional lives.”Footnote 82 It seems that the introduction of extended leave policies allowed the state to boost its positive image as an entity striving for a welfare system that benefited women and improved the living standards of Polish families, simultaneously neutralizing the more threatening demands of striking female workers. In this context, the 6th PUWP Congress announcement of extended maternity leave served as a means to reconcile women's roles as mothers and workers.

In the early 1970s, contrary to the assumption that women would overwhelmingly approve and support the new solutions, textile workers could not afford unpaid leave, as poor families simply could not do without a female breadwinner.Footnote 83 By promoting the image of vigorous consumption in households led by resourceful wives on maternity leave, however, the authorities gave the impression that they were responsive to the demands of the female working class, fully acceptant of their aspirations. This message was paired with the overused propaganda representation of the Secretary General as the “father of the nation” who celebrated Women's Day with due respect to mothers and wives: “We would like to thank you wholeheartedly for carrying out the difficult task of raising Polish children … . The nation's future is—to a great extent—in your hands,” said Gierek in his address to Polish women on March 8, 1973, several months after the 6th PUWP Congress.Footnote 84 The authorities benefited from the introduction of the leave measures in two ways. First, they presented themselves as those who listened to women's demands and fulfilled the conditions of the social contract that called for an expanding welfare state. Second, their actions were in line with natalist policies, which shifted the responsibility for Poland's future onto young mothers.

In August 1980, the Interfactory Strike Committee (Międzyzakładowy Komitet Strajkowy, MKS) of the Gdańsk Shipyard formulated the famous Twenty-one Demands, subsequently included in the Gdańsk Agreement. Few scholars recall, however, that one of the demands concerned improving the kindergarten and daycare situation (“Item 17: Ensure an adequate amount of places in kindergartens and daycares for children of working women”). Another one called for the extension of paid maternity leave (“Item 18: Introduce a three-year paid maternity leave”).Footnote 85 As it soon became evident, only a small part of the demands were met by the authorities. Despite a declaration incorporated into the Gdańsk Agreement, the availability of daycare facilities (Item 17 of the Agreement) remained unchanged by the end of the 1980s, and was by no means “adequate.”

On the other hand, the regulation of July 1981, passed several months before the introduction of martial law in Poland, was a significant change that met the demands of Item 18 by expanding paid maternity leave.Footnote 86 The adopted measures were further proof that the state, in the fourth phase of communist welfare, continued to focus on maternity leave at the expense of care facilities. Despite some reservations and no clear enthusiasm in the women's press, more and more Polish women took advantage of the three-year paid leave, particularly given low availability of kindergartens and daycares. In 1969, nearly 50,000 Polish women decided to go on leave, with the number exceeding 200,000 by the mid-1970s. After a decision had been made to extend paid leave, the number of mothers on leave reached a whopping 800,000, which represented an overwhelming majority of the “mother workforce.”Footnote 87 It seems that in the face of inadequate institutional care, working mothers found the financial incentive to be the decisive factor. One year before the fall of communism, a Party report read as follows: “Young mothers on maternity leave have become a familiar sight. Since 1984, the number of women on maternity leave has fluctuated around 800,000. There is no doubt that this trend is related to the underdevelopment of care facilities for children. With this respect, our country ranks among the worst socialist states.” The document assumed that by 1990, nearly 60% of children would be in care, which would still mean that the childcare problem had not been solved.Footnote 88 No one expected communism to fall.

Revisiting “Wedded to Welfare”

Yet there was another reason why each year thousands of Polish women chose to stay on maternity leave. When contemplating the frustration of 1980s Polish society, we must not forget that women—mothers and homemakers—often experienced shortages that were commonly referred to as “catastrophic.” Consequently, the first factor that contributed to the dramatic increase in the number of women on leave was how they themselves saw their situation. As testified by numerous women's voices published in women's magazines, whether journalists or readers, they saw the reality of their everyday life as being “deep in crisis.”Footnote 89 In the 1980s, women of reproductive age could not possibly remember the war, but continued to compare their experiences with the stories told by their mothers and grandmothers. Food shortages, people demanding “bread and butter” and looking for ways to stave off hunger were, for instance, the running theme of “hunger strikes” in the summer of 1981, with similar calls appearing in the media.Footnote 90 Though it was still uncertain whether the high birthrate recorded in the late 1970s and the early 1980s was a result of natalist state policies or a simple echo of the post-war baby boom, population growth generally bred discontent. In the eyes of the average Polish family, it could potentially become a factor lowering the already poor living standards or even exposing families to risks of hunger.

Practical considerations were also an important factor. Women worked less important jobs with poor pay, which could contribute to their decision to go on leave. Families in communist states put much stock in the resourcefulness of its members, who were always ready to help track down goods in short supply, queue in front of a store for hours, trade ration stamps, or trade on the black market.Footnote 91 Because the availability of deficit goods was as important as salaries, many families thought that women's time could be put to more efficient use at home rather than at work. Mothers on leave enjoyed more flexibility, could acquire rare goods by frequently visiting the local market or could stand in line for hours, compensating for their low earnings. Furthermore, by remaining on leave they became involved in the second economy, which constituted an important center of trade in communist Poland.Footnote 92 Such forced choices, paired with the need to “chase” after goods or participate in the second economy was frustrating, especially for educated women who saw their work as more than a means to economic survival. On the pages of the women's weekly Zwierciadło, authors reacted to crisis-generation women with restraint aware that maternity leave, while helpful in the short term to women who found themselves in difficult circumstances, in the long term created a risk that women could lose contact with the job market. The fact that some women went on leave to escape being made redundant was also significant. At the same time, the public continued to hope that consumer goods would become more available and that the number of kindergartens and daycares would increase. Thus, Zwierciadło contributors openly called maternity leave a temporary solution that would remain popular only as long as the supply and childcare facilities problems persisted.Footnote 93

It was clear that some women treated maternity leave as a poor substitute for a state welfare, less helpful than kindergartens and daycares. Just as commentators writing about household product availability often invoked the post-war argument of “avoiding hunger,” those assessing female benefits often stressed their compensatory nature. In time, some social ambitions were abandoned and people started limiting their aspirations, not unlike in the post-war period. I see it as history having had gone full circle, with 1980s mothers finding common ground with their mothers, who remembered the harsh post-war realities and Stalinist austerity, poles apart from the period of consumerist expectations that followed.Footnote 94 As we can see, both periods bear strong similarities—after the war and in the last years of communism, state welfare was meant to mitigate the numerous problems faced by women; to “relieve them of excessive burdens,” rather than guarantee high standards of living and stabilization.

Was a Communist Welfare State Necessary?

According to David Crowley and Susan E. Reid, communist states were forced to constantly balance between the demand for consumer products and the fear of falling into sinful western consumerism. Communists had to simultaneously meet and limit consumer expectations.Footnote 95 With this in mind, the issue of post-Stalinist consumption in the USSR and eastern Europe, which has in recent years attracted much interest from scholars, could be—somewhat controversially—construed as a key change which conserved and extended the lifespan of the system, while simultaneously forcing its representatives to balance precariously between conflicting ideas. One could even hypothesize that the existence of late communist state welfare was the basis of a fragile social contract that bought communists several more years in power. Social benefits such as paid maternity leave, daycare, and kindergartens, inscribed in the Constitution of 1952 as a “guarantee of women's equality,” seemed to cause less controversy than consumption, as they were less at odds with the expectation of what communism should represent. Unlike in the case of luxury goods, people commonly expected to have equal and fair access to welfare benefits, which meant that any limits in this area led to gradual delegitimization of the system. This was particularly evident in 1980 in the Twenty-one Demands, many of which in fact called for efficient state-welfare services, such as maternity leave, disability, retirement payments, medical care, and institutionalized childcare.

After 1989, the Polish political elite—this time elected by democratic process—made a sudden decision to dismantle the welfare state, acting neither in line with the original demands of Solidarity, nor with the expectations of the majority of Poles. At the time, free-market proponents associated welfare services directly with inefficiency, blaming them for the collapse of communism.Footnote 96 Benefits for mothers were reduced. The length of maternity leave remained unchanged, but fewer women were interested in taking it, as the amount of payment was reduced. Women were also less eager to go on leave because of new social realities, such as stronger fears of unemployment, which could drastically reduce the family's income. The state also renounced its obligations related to providing kindergarten and daycare places for children, placing their burden on local governments. As the number of facilities fell (by a stunning 60%) and fees increased, few families could take advantage of institutional childcare.Footnote 97

The new market economy in Poland saw the rapid decline of the welfare state, with debates, pressures, and demands of 1980 quickly becoming forgotten and losing impact. In the late 20th century, Poland experienced high unemployment rates, low income, and growing social inequality. Some Poles started to associate the former communist state with a range of social benefits that it provided—job guarantees, organized holidays, free healthcare, and cheap housing.Footnote 98 Obviously, such connotations were tainted with presentism and arose in relation to the specific experiences of the post-1989 transformation. As such, they did not account for the historical process which led to the creation of the communist welfare state, including the post-war struggle with its establishment, and especially the unequal access to benefits and the common practice of snubbing the needs of working women. This line of thought was not entirely irrational, however; given the drastic reduction of monetary benefits and care facilities, some working mothers remembered even the 1980s as a time when families had better lives.

Welfare state benefits for women in communist-era in Poland were affected by a wide variety of factors, including Stalinist industrialization, post-1956 communist consumerism, early 1960s demographic anxieties, the 1980 political crisis, and the deep economic crisis of the decade that followed. From the perspective of working women's interest, the breakthrough came in the 1970s, when the welfare state started to detach itself from gender equality policies, and gender equality in general became an area of interest chiefly for rich western countries. In eastern Europe, the idea faded, even though some rhetorical rituals were still being followed in state propaganda. Afterwards, the role of the communist welfare state continued to decline; it became, first and foremost, a tool designed to control the population and female fertility. The benefits, however, were still an important component of social order. As the economic crisis progressed and shortages increased, state welfare continued to play a vital role in the lives of women, mitigating the growing problems encountered by the economy of shortage in the final decade of communist rule.