Introduction

Parasites have long been known to affect many aspects of their host's life history, including survival, growth, reproduction and behaviour (Park, Reference Park1948; Read, Reference Read1988; Poulin, Reference Poulin1995; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Renaud, Demee and Poulin1998; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Redak and Wang2001; Bollache et al., Reference Bollache, Rigaud and Cézilly2002; Lefèvre et al., Reference Lefèvre, Lebarbenchon, Gauthier-Clerc, Missé, Poulin and Thomas2009), consequently impacting key ecological interactions such as predation and competition (Kunz and Pung, Reference Kunz and Pung2004; Mikheev et al., Reference Mikheev, Pasternak, Taskinen and Valtonen2010; Reisinger et al., Reference Reisinger, Petersen, Hing, Davila and Lodge2015; Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2018). Furthermore, impacts on individual hosts can in turn have community-wide repercussions (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Renaud, Demee and Poulin1998; Lefèvre et al., Reference Lefèvre, Lebarbenchon, Gauthier-Clerc, Missé, Poulin and Thomas2009); direct and indirect impacts of parasites can play a key role in determining species distributions, biodiversity, trophic interactions and, ultimately, community structure in many ecosystems (Price et al., Reference Price, Westoby, Rice, Atsatt, Fritz, Thompson and Mobley1986; Schall, Reference Schall1992; Kiesecker and Blaustein, Reference Kiesecker and Blaustein1999; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Poulin, De Meeüs, Guégan and Renaud1999; Fredensborg et al., Reference Fredensborg, Mouritsen and Poulin2004; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Byers, Cottingham, Altman, Donahue and Blakeslee2007; Weinstein et al., Reference Weinstein, Titcomb, Agwanda, Riginos and Young2017).

In ecosystems where two or more host species share the same parasites, one may be more tolerant to infections and become both a reservoir host and superior competitor (Greenman and Hudson, Reference Greenman and Hudson2000; Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2017), resulting in the eventual exclusion of the less tolerant host species (Park, Reference Park1948; Greenman and Hudson, Reference Greenman and Hudson2000). On the other hand, parasites may weaken the stronger competitor and facilitate the coexistence of alternative hosts (Kiesecker and Blaustein, Reference Kiesecker and Blaustein1999; Hatcher and Dunn, Reference Hatcher and Dunn2011). Apparent competition may also occur between species that share a parasite, creating indirect competition between the two hosts (Holt, Reference Holt1977; Hudson and Greenman, Reference Hudson and Greenman1998). Although the presence of shared parasites may allow one species to out-compete another, both species may still be at a disadvantage when interacting with additional non-host species or when avoiding unaffected predators, including intra-guild ones.

Predation, particularly intra-guild predation, can also be altered by parasites thus affecting predator–prey dynamics within a community (MacNeil et al., Reference MacNeil, Fielding, Dick, Briffa, Prenter, Hatcher and Dunn2003). Many infected hosts will also display behavioural changes that increase the parasite's probability of transmission to the next host (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Huntingford and Crompton1995; Poulin, Reference Poulin1995; Klein, Reference Klein2005; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Adamo and Moore2005; Sparkes et al., Reference Sparkes, Weil, Renwick and Talkington2006; Lagrue et al., Reference Lagrue, Kaldonski, Perrot-Minnot, Motreuil and Bollache2007). However, parasite-induced behavioural modifications can also increase host vulnerability to other predators that are unsuitable as hosts (i.e. ‘dead-end’ hosts; Mouritsen and Poulin, Reference Mouritsen and Poulin2003; Seppälä and Jokela, Reference Seppälä and Jokela2008; Seppälä et al., Reference Seppälä, Valtonen and Benesh2008). The importance of parasite-mediated predation remains poorly understood in many cases, let alone at the community or ecosystem level.

In addition, multispecies infections (i.e. simultaneous infections by different parasite species) in a single host are very common in natural systems, further complicating relationships among hosts, parasites and ecosystems (Hughes and Boomsma, Reference Hughes and Boomsma2004; Pedersen and Fenton, Reference Pedersen and Fenton2007; Lagrue and Poulin, Reference Lagrue and Poulin2008; Alizon et al., Reference Alizon, de Roode and Michalakis2013; Thumbi et al., Reference Thumbi, Bronsvoort, Poole, Kiara, Toye, Mbole-Kariuki, Conradie, Jennings, Handel, Coetzer, Steyl, Hanotte and Woolhouse2014; Lange et al., Reference Lange, Reuter, Ebert, Muylaert and Decaestecker2014). Although each infection may be independent, the presence of diverse parasite assemblages can result in synergistic or antagonistic effects (Lagrue and Poulin, Reference Lagrue and Poulin2008; Alizon et al., Reference Alizon, de Roode and Michalakis2013; Lange et al., Reference Lange, Reuter, Ebert, Muylaert and Decaestecker2014; Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2017), and the potential consequences are often very difficult to forecast (Alizon, Reference Alizon2013). Interactions among parasites found in the same host may shape their respective behavioural modification of the host, and ultimately its survival (de Roode et al., Reference de Roode, Culleton, Cheesman, Carter and Read2004; Balmer et al., Reference Balmer, Stearns, Schötzau and Brun2009; Alizon, Reference Alizon2013; Lange et al., Reference Lange, Reuter, Ebert, Muylaert and Decaestecker2014). Generally, and despite their common occurrence and potential importance, we still understand little about how shared parasites and multispecies infections shape host communities.

In spite of increasing evidence of direct and indirect effects of parasite-induced modifications of host interactions (Park, Reference Park1948; Holt and Lawton, Reference Holt and Lawton1994; Jaenike, Reference Jaenike1995; Tompkins et al., Reference Tompkins, Draycott and Hudson2000, Reference Tompkins, Greenman and Hudson2001; Bollache et al., Reference Bollache, Gambade and Cézilly2001; Rivero and Ferguson, Reference Rivero and Ferguson2003; Reisinger and Lodge, Reference Reisinger and Lodge2016; Vivas Muñoz et al., Reference Vivas Muñoz, Staaks and Knopf2017; Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2018), most have been studied on a smaller scale, focusing on two host species with one shared parasite. Host–parasite–community dynamics in natural ecosystems are far more complex and difficult to predict. The strength of host inter- and intraspecific competition, the variability in host vulnerability to infections by multiple parasites and the intensity of parasite transmission all affect the outcome of parasite-mediated competition (Hatcher and Dunn, Reference Hatcher and Dunn2011). The interplay of competition with other factors, such as reproduction and predation, may lead to outcomes other than those predicted by studying these impacts alone. For example, Hymenolepis diminuta (cestode) reduces the fitness of the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum, under high but not low intraspecific competition (Yan and Stevens, Reference Yan and Stevens1995). Despite extensive modelling of the role of parasites in structuring and shaping ecosystems (Anderson and May, Reference Anderson and May1981; Holt and Pickering, Reference Holt and Pickering1985; Begon et al., Reference Begon, Bowers, Kadianakis and Hodgkinson1992; Begon and Bowers, Reference Begon and Bowers1994; Yan, Reference Yan1996; Greenman and Hudson, Reference Greenman and Hudson1999, Reference Greenman and Hudson2000; Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, Allesina, Arim, Briggs, De Leo, Dobson, Dunne, Johnson, Kuris, Marcogliese, Martinez, Memmott, Marquet, McLaughlin, Mordecai, Pascual, Poulin and Thieltges2008; Hatcher and Dunn, Reference Hatcher and Dunn2011; Thieltges et al., Reference Thieltges, Amundsen, Hechinger, Johnson, Lafferty, Mouritsen, Preston, Reise, Zander and Poulin2013; Sieber et al., Reference Sieber, Malchow and Hilker2013; Rabajante et al., Reference Rabajante, Tubay, Uehara, Morita, Ebert and Yoshimura2015; Vannatta and Minchella, Reference Vannatta and Minchella2018), empirical studies examining both multi-species infections and how parasites modify interactions among hosts are still rare. Thus, there is a strong need for empirically controlled multi-species, multigenerational experiments to properly understand the role parasites play from a community perspective. We investigated how parasites affect community structure and dynamics using multiple mesocosms with four host species and four parasite species from a well-studied benthic lake community, controlling for the relative exposure to parasites. The relatively short life spans of the host species in this system provided an opportunity to examine the role of parasite mediation across multiple generations. The host species are also important food sources for many consumers within the ecosystem and serve as intermediate hosts to a variety of parasites. In addition, all four host species compete for resources and may consume each other (intra-guild predation), which made the selected community ideal for studying parasite-mediated interspecific interactions (Chadderton et al., Reference Chadderton, Ryan and Winterbourn2003; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Lewis and Winterboum2011). All parasites and their hosts in this system are well studied (Poulin, Reference Poulin2001; Lefèbvre et al., Reference Lefèbvre, Fredensborg, Armstrong, Hansen and Poulin2005; Lagrue and Poulin, Reference Lagrue and Poulin2008, Reference Lagrue and Poulin2015; Luque et al., Reference Luque, Vieira, Herrmann, King, Poulin and Lagrue2010; Rauque et al., Reference Rauque, Paterson, Poulin and Tompkins2011), which allowed us to integrate prior research with this current study. If parasites modulate community dynamics, we expected to see species-specific differences in host fecundity, recruitment and especially in host relative abundances over time.

Materials and methods

Study system and sample collection

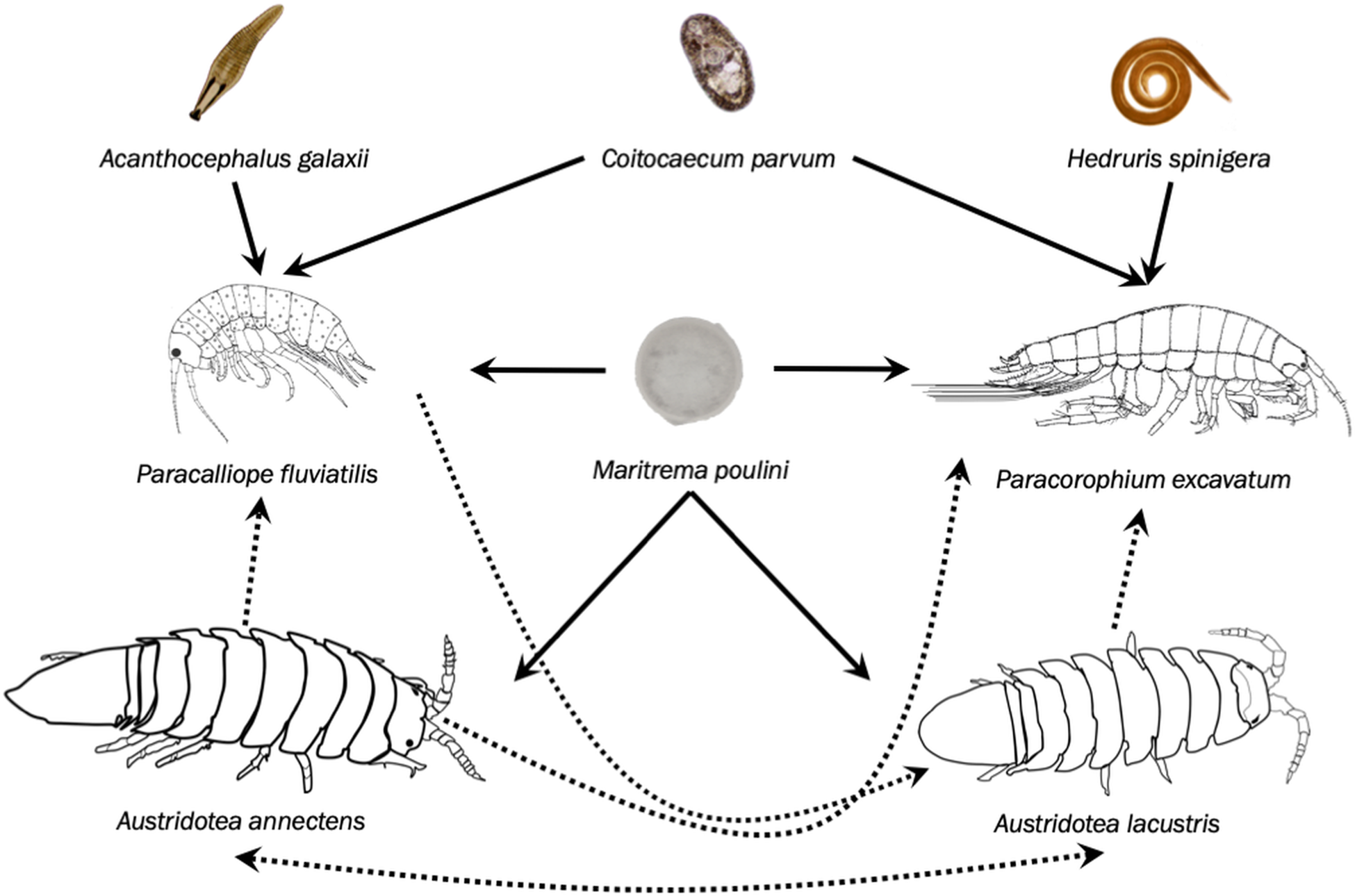

Two amphipod species (Paracalliope fluviatilis and Paracorophium excavatum) and two isopod species (Austridotea annectens and Austridotea lacustris) are commonly found in New Zealand lake ecosystems. All four species compete with each other for resources, share a variety of macroparasites in different combinations, and the two isopods may prey on the two amphipods (Holton, Reference Holton1984; Lagrue and Poulin, Reference Lagrue and Poulin2007; Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2017). Two trematode species are present in the system: Coitocaecum parvum infects both amphipod species and Maritrema poulini infects both amphipods as well as A. annectens. Paracalliope fluviatilis also serves as an intermediate host to the fish acanthocephalan, Acanthocephalus galaxii, whereas P. excavatum is the sole intermediate host of the fish nematode Hedruris spinigera. Note that M. poulini has also been found in A. lacustris but at extremely low prevalence (Presswell et al., Reference Presswell, Blasco-Costa and Kostadinova2014; Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2018). The overall structure of this study system is outlined in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Structure of the freshwater crustacean community showing the four larval parasite species and which of the four crustacean hosts they infect. Amphipod images (Paracalliope fluviatilis and Paracorophium excavatum) modified from Chapman et al. (Reference Chapman, Lewis and Winterboum2011). Solid lines represent parasite–host relationships and dotted lines represent competitive/predatory relationships.

Maritrema poulini (Microphallidae) uses waterfowl (definitive hosts), the New Zealand mudsnail, Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray 1843; first intermediate host) and isopods (A. annectens or A. lacustris) or amphipods (P. excavatum or P. fluviatilis) (second intermediate hosts; Presswell et al., Reference Presswell, Blasco-Costa and Kostadinova2014). The latter are infected by transmission stages known as cercariae that penetrate through their exoskeleton after being released from the snail host. Coitocaecum parvum (Opecoelidae) has a similar life cycle although it uses fish as definitive hosts (Lagrue and Poulin, Reference Lagrue and Poulin2007). As all four invertebrates serve as intermediate hosts to M. poulini and it is possible to successfully replicate the parasite transmission process in a mesocosm setting, this trematode was the focal parasite in our low and high exposure treatments.

Hedruris spinigera is a nematode parasite found exclusively in the amphipod P. excavatum; it is transmitted to fish definitive hosts through predation of infected amphipods (Luque et al., Reference Luque, Vieira, Herrmann, King, Poulin and Lagrue2010; Ruiz-Daniels et al., Reference Ruiz-Daniels, Beltran, Poulin and Lagrue2012). Similarly, the acanthocephalan A. galaxii uses fish as definitive hosts. In both parasite species, reproduction occurs in the fish digestive tract and eggs are passed out in host feces (Hine, Reference Hine1977). Amphipods become infected when accidentally ingesting parasite eggs (Hine, Reference Hine1977; Rauque et al., Reference Rauque, Paterson, Poulin and Tompkins2011). Both of these species are found in very low prevalence in their natural habitat (Lagrue and Poulin, Reference Lagrue and Poulin2008; Ruiz-Daniels et al., Reference Ruiz-Daniels, Beltran, Poulin and Lagrue2012; Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2017). Their life histories make it difficult to successfully replicate natural transmission in the laboratory. We also could not manipulate exposure to C. parvum due to seasonal unavailability of infected snails.

We collected samples of amphipods, isopods and snails (P. antipodarum, as the source of the parasite M. poulini) from the littoral zone of Lake Waihola, South Island, New Zealand (46°01′14S, 170°05′05E) between April and May 2017. No permits were required for this work. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guides on the care and use of laboratory animals. Amphipods and A. annectens isopods were caught using dip-nets (net width 2 mm), sieved to isolate animals and transported to the laboratory in lake water. Austridotea lacustris isopods were collected by hand underneath large rocks near the shoreline. Due to the nature of sampling, no amphipod or isopod smaller than 2 mm in total body length was collected. Mud snails P. antipodarum were also collected from macrophytes, sediment and stones along the shoreline of Lake Waihola using a dip net and by hand. Amphipods and isopods were maintained separately by species in 10 L tanks containing aerated water. Animals were kept in the same room (T = 15 ± 3 °C), they were housed with aquatic plants (Myriophyllum triphyllum and Elodea canadensis) as a food source and maintained under a controlled photoperiod (12 h dark and light).

Snail infections

Infected snails were used as a source of parasites that were introduced into experimental mesocosms. To determine the infection status of the snails, individuals were separated into 12-well tissue culture plates with ten individuals per well filled with approximately 2 mL of filtered lake water. Snails were then incubated for 3 h at 20 °C under constant light to trigger the emergence of cercariae (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Fredensborg and Poulin2005). Cercariae are infective free-living larval stages that are released into water from the snail host which then locate and infect a suitable second intermediate host. Cercariae were identified based on morphological features (Hechinger, Reference Hechinger2012; Presswell et al., Reference Presswell, Blasco-Costa and Kostadinova2014). Wells were screened for the presence of cercariae and snails from wells that contained cercariae were further separated and screened individually. All snails shedding M. poulini cercariae were isolated and maintained in 250 mL plastic containers until needed. A subsample of uninfected snails was haphazardly chosen and isolated for use in the low exposure tanks (i.e. low parasite prevalence). These individuals were screened one more time pre-experiment to confirm their uninfected status. All snails were screened and dissected post-experiment for further verification of infection status.

Mesocosm experiment

We manipulated the exposure of hosts to parasites in an array of experimental mesocosms to explore their effects on the composition of communities with four species of crustaceans. High exposure tanks contained a single snail infected with M. poulini, as a source of infection for crustaceans, low exposure tanks received an uninfected snail to control for the presence of snails. All study species were collected from natural settings where parasites are present, and thus may have some pre-existing parasite burden. The important distinction between the two treatments was differential exposure to the additional source of M. poulini. Each mesocosm, in both treatment types, initially contained 20 P. fluviatilis individuals (approximately 50% female and 50% male based on visual identification, Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2017), ten P. excavatum (sex initially unknown as it is impossible to differentiate sexes without dissection), ten A. annectens (near identical mixture of large and small individuals in each replicate to include a mixture of ages and sexes), five A. lacustris (with at least one very large, therefore mature, male per replicate) and an infected or uninfected New Zealand mudsnail, P. antipodarum. These relative abundances and densities of crustacean hosts roughly match those observed in nature (Lagrue et al., Reference Lagrue, Poulin and Cohen2015). Each mesocosm was a 14 L aquarium (AquaOne© Starter Kit, 315 length × 185.5 width × 245 mm height, glass sides with plastic base and lid). All tanks were filled with continuously aerated and aged lake water collected at least a week before the start of the experiment to ensure any parasite infective stages (cercariae) present in the water had died before the mesocosms were set up (Morley, Reference Morley2012). The bottom of each mesocosm was covered with a mixture of fine sand substrate, small rocks (each approximately 10 × 5 × 2 mm), and two large rocks (approximately 80–150 × 40–100 × 30–60 mm). Each mesocosm contained the same volume of the substrate material. All substrates were fully cleaned and sanitized prior to the experiment. Aquatic plants (M. triphyllum and E. canadensis) were added to provide food (40–60 g per week). Plants were weighed to ensure equal amounts of food were added to each replicate. Prior to transfer to mesocosm replicates, all plants were rinsed with water and frozen for 24 h to ensure that no additional animals or parasite infective stages were transferred.

Mesocosms ran for 9 weeks, with a total of 36 experimental units (18 in each treatment group, low and high parasite exposure). A subsample of six mesocosms per treatment was destructively sampled every 3 weeks to monitor changes in parasite and host population levels. Each mesocosm was supplied with weekly input of aquatic plants for food (as described above). Mesocosms were housed in the same room. Twenty P. fluviatilis amphipods were added weekly and two P. excavatum every 3 weeks to every mesocosm (regardless of treatment) to simulate the migration of fresh individuals to the community that would be observed in natural conditions. While all four host species live within the littoral zone and interact, P. fluviatilis lives among aquatic macrophytes, whereas the other three species spend most of their time in the benthos, often buried in the substrate (Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2018). Although these species may exhibit movement in search of resources or mates, they consistently re-settle on or very near their prior location (Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2018). All individuals added came from the same location as the original crustaceans. The temperature of the room and water were recorded throughout the experiment. All tanks were under a controlled photoperiod (12 h dark and light).

During each sampling, mesocosms were disassembled by carefully removing small aliquots of water and sand substrate (250 mL), which were subsequently screened by two observers (the same throughout the experiment) with the naked eye to remove any live individuals. The few carcasses of dead crustaceans found during the process were not included in the dataset as we could not determine when or why they died (<1 carcass/tank on average was found). This process continued until the entire tank had been emptied and screened. Each live crustacean individual was placed in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube with lake water until dissection. All amphipods were placed in the refrigerator (4 ± 1 °C) after collection to reduce oxygen usage and minimize mortality, and dissections took place within 72 h of collection. Ethanol was added to the tubes containing isopods for preservation and isopods were dissected within one week; unlike the amphipods, ethanol does not affect dissections and parasite identification in isopods. Each individual crustacean was measured, sexed and dissected to record numbers of parasites of each species (including those acquired naturally before the experiment and those acquired during the experiment). The total body length of each individual was determined by measuring from the anterior tip of the cephalic capsule to the posterior end of the uropods. Isopods shorter than 7–8 mm in body length were impossible to sex due to the lack of secondary sexual characters and thus considered juveniles (Chadderton et al., Reference Chadderton, Ryan and Winterbourn2003; Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2017). For the same reasons, amphipods smaller than 1.5 mm were considered juveniles. Individuals smaller than 2 mm were considered to have hatched in the mesocosm during the experiment as individuals selected at the beginning exceeded this size threshold. Egg presence and numbers were also recorded in gravid females. The presence of precopulatory pairs, where a male is clasping a female, was also recorded (Sutcliffe, Reference Sutcliffe1992). We defined prevalence as the percentage of infected hosts, abundance as the number of parasites per host including zeroes (i.e. uninfected hosts) and mean abundance as the mean number of parasites per host among a sample of hosts. For crustacean hosts, relative abundance was defined as the percentage of the total number of recovered crustacean individuals in each mesocosm belonging to each of the four species.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in JMP® 12 (SAS Institute Inc, 2015) and R statistical software (http://www.R-project.org). We analysed differences in host species population sizes between treatments using a MANOVA (with treatment type and time the main predictors), with ANOVA as a post-hoc analysis. To correct for the inflated Type 1 error rate by using this method, a Bonferroni correction has been added. With this addition, the adjusted α-value = 0.0125. Best-fit lines were added to Figs 2 and 3 to illustrate the direction of relationship between host/relative abundance over time but do not correspond to the actual statistical analysis. Differences in sex ratios between treatments were examined using contingency analysis (with treatment type as main predictor variable). Differences in the number of eggs per female host species between treatment groups were analysed using an ANOVA. The differences in the proportion of females carrying young and the proportion of pairs between treatment groups were analysed using contingency analysis. Host species were analysed separately.

Fig. 2. Comparison of amphipod and isopod species abundance per treatment group (mean ± s.e.) over three sampling periods, (a) Paracalliope fluviatilis, (b) Paracorophium excavatum, (c) Austridotea annectens and (d) Austridotea lacustris. Values at week 0 represent the number of individuals added to the mesocosm at the beginning of the experiment. Regression lines represent the direction of relationships (best-fit lines) but not statistical relationship.

Fig. 3. Relative species abundance (as a percentage of the total community) of (a) the amphipods, Paracalliope fluviatilis and Paracorophium excavatum, and (b) the isopods, Austridotea annectens and A. lacustris, in both low and high exposure treatments over the 9-week trial period, with replicates sampled every 3 weeks. Sample size of six mesocosm replicates per treatment in each sampling period. Regression lines represent the direction of relationships (best-fit lines) but not statistical relationship.

The differences in the relative abundance of the three-host species (P. fluviatilis, P. excavatum and A. annectens) were analysed using MANOVA (with treatment type and time the main predictors), using Pillai's Trace, as it is the most powerful and robust MANOVA statistic for general use (Gotelli and Ellison, Reference Gotelli and Ellison2004). As relative abundances add up to 100%, the rarest of the four crustaceans (A. lacustris) was not used in this analysis. Follow-up ANOVAs were used to determine which species accounted for observed differences. The parasite prevalence was compared between treatments using a contingency analysis, with treatment type the main predictor variable. A relationship was considered significant if the P value was ⩽0.05, unless a Bonferroni correction was added (as described above) and considered a trend if the P value was 0.05–0.10. Normality of the data was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk Test and equal variance was checked with residual plots. All tests showed a P value >0.05 and the samples were independent, therefore all assumptions were met in each test.

Results

We introduced a total of 4320 P. fluviatilis, 504 P. excavatum, 360 A. annectens, 180 A. lacustris and 60 P. antipodarum during the experiment. Overall, when disassembling the mesocosms, we recovered 3878 P. fluviatilis, 176 P. excavatum, 227 A. annectens and 156 A. lacustris. Five species of parasites, M. poulini, C. parvum, H. spinigera, A. galaxii and a single individual of an unidentified cestode (Family Hymenolepididae), were found in invertebrate hosts.

Host population dynamics

The absolute abundance of the four host species differed between treatments throughout all three sampling periods (MANOVA, Pillai's Trace, week: Pillai's Trace = 0.77, F 4,29 = 24.1, P < 0.0001, treatment: Pillai's Trace = 0.83, F 4,29 = 34.6, P < 0.0001).

The amphipod P. fluviatilis was consistently more abundant in low parasite exposure mesocosms on all three sample dates (ANOVA, week: F 1,32 = 104.2, P < 0.0001, treatment: F 1,32 = 133.0, P < 0.0001, with a significant interactive effect, F 1,32 = 52.3, P < 0.0001; Fig. 2a). Experimental populations of P. fluviatilis grew at an exponential rate in the low exposure treatment compared to almost no growth in the high exposure treatment (Fig. 2). The total number of P. fluviatilis increased beyond the number of individuals we initially introduced and added weekly in the low exposure treatment at each sampling period, indicating that recruitment occurred (i.e. 200 individuals added to each mesocosm, and a mean of 287 ± 19 individuals retrieved at week 9; Fig. 2a). In two tanks sampled at week 9 in the low exposure treatment, the number of adults exceeded 200 individuals, strongly suggesting a second generation was produced in the mesocosms. The number of juveniles differed between each treatment type throughout all sampling periods, indicating higher recruitment in the low exposure treatment (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of sex ratios between low and high exposure treatments throughout the three sampling periods (using contingency analysis, test statistic – χ 2, d.f. = 1)

Abundance of juveniles, or individuals with indeterminate sex due to immaturity (combined), were compared between treatments throughout sampling periods (using analysis of variance, test statistic and d.f. – F 1,10). Proportion of juveniles in each treatment type. Significant differences are bolded.

Paracorophium excavatum populations did not differ between high and low parasite exposure treatments throughout the experiment (ANOVA, week: F 1,32 = 0.95, P = 0.34, treatment: F 1,32 = 0.02, P = 0.90, with no interactive effect, F 1,32 = 1.3, P = 0.27; Fig. 2b). Although there was considerable variation between sampling dates in the same treatment, mean number per mesocosm replicate was not different between sampling dates.

Abundance of both species of isopods appears to decrease over time in low and high exposure treatments with the isopods in the high exposure tanks increasing at a faster rate, but with a Bonferroni correction, there are no significant differences. The number of A. annectens per tank was consistent between treatments (ANOVA, week: F 1,32 = 6.2, P = 0.018, treatment: F 1,32 = 6.7, P = 0.015, interactive effect, F 1,32 = 1.3, P = 0.26; Fig. 2c). The populations of A. lacustris stayed consistent over the three sampling dates, and did not differ between treatments (ANOVA, week: F 1,32 = 5.6, P = 0.025, treatment: F 1,32 = 4.5, P = 0.042, but with no interactive effect, F 1,32 = 0.22, P = 0.64; Fig. 2d).

Host community structure

The relative abundance of both amphipod species and A. annectens in the invertebrate community differed between the low and high parasite exposure treatments throughout the experiment (MANOVA, Pillai's Trace, week: Pillai's Trace = 0.59, F 3,30 = 14.4, P < 0.0001, treatment: Pillai's Trace = 0.70, F 3,30 = 23.4, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3a). The relative abundance of P. fluviatilis was higher in low exposure mesocosms in all three sampling periods (ANOVA, week: F 1,32 = 33.7, P < 0.0001, treatment: F 1,32 = 49.9, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3a). Conversely, the relative abundance of P. excavatum was higher in the high exposure mesocosms in all three sampling periods (ANOVA, week: F 1,32 = 2.1, P = 0.16, treatment: F 1,32 = 15.2, P = 0.0004; Fig. 3a), but did not differ by week. Austridotea annectens relative abundance was higher in the high exposure treatment in week three samples (ANOVA, week: F 1,32 = 33.6, P < 0.0001, treatment: F 1,32 = 16.4, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3b).

The relative abundances of A. lacustris decreased over time and in both treatments (Fig. 3b). Austridotea lacustris showed the same relationship between high and low exposure treatments, with their relative abundance being higher in high exposure mesocosms throughout all three sampling periods (week 3, F 1,10 = 15.1, P = 0.003; week 6, F 1,10 = 38.7, P < 0.0001; week 9, F 1,10 = 30.5, P = 0.0003; Fig. 3b).

Parasite infection patterns

The highest number of individuals of M. poulini per host was 53 (in P. excavatum), ten for C. parvum (in P. excavatum) and one for both A. galaxii (in P. fluviatilis) and H. spinigera (in P. excavatum). The prevalence of M. poulini was higher in P. fluviatilis from the high exposure treatment throughout all sampling periods (Table 2). Consistently, the mean abundance of M. poulini was higher in individuals from the high exposure treatment throughout all the sampling periods (Fig. 4; Table 2). The prevalence of C. parvum in P. fluviatilis was highest in the high exposure tanks in week 3 and 6, but there was no difference by week 9 (Table 2). The mean abundance of C. parvum was also higher in the high exposure tanks in week 3, but there was no difference in week 6 or 9 (Supplementary Information Fig. S1; Table 2).

Fig. 4. Mean abundance of Maritrema poulini in three host species, Paracalliope fluviatilis, Paracorophium excavatum and Austridotea annectens, in both low and high treatments through the sampling periods (a) week 3, (b) week 6, and (c) week 9. Sample size of 6 mesocosms per treatment per sampling period.

Table 2. Differences in reproductive measures and parasite infections between low and high exposure treatments throughout the three sampling periods

Differences in the presence of eggs, pairing and parasite prevalence were examined using contingency analysis (d.f. = 1). Variation in the mean number of eggs per female and parasite abundance were examined using analysis of variance. Significant differences are bolded, and trends marked with *.

Paracorophium excavatum showed similar M. poulini prevalence in both treatments and all sampling dates (Table 2). However, the mean abundance of M. poulini was higher in high exposure treatments during the week 3 sampling, but did not differ in week 6 or 9, although the difference was greater in week 6 (Fig. 4; Table 2). The prevalence of C. parvum in P. excavatum was similar between low and high exposure treatments throughout all three sampling periods (Table 2). The mean abundance followed a similar pattern in the last two sampling periods, however, the mean abundance of C. parvum tended to be higher in the high exposure treatment in week 3 (Supplementary Information Fig. S1; Table 2).

Co-infections by M. poulini and C. parvum occurred in both amphipod species, but usually at low prevalence; they were more common in P. fluviatilis in the high exposure treatment during week 3 and 6, but they did not differ from the low exposure treatment in week 9 (Table 2). Further details are provided in the online Supplementary Information.

The prevalence of M. poulini in A. annectens was higher in the high exposure treatments in week 3 and 9, but not in week 6 (Table 2). The mean abundance of M. poulini followed the same trends, with the abundance being higher in the high exposure treatments in week 3 and 9, but only tended to be higher in week 6 (Fig. 4; Table 2). Maritrema poulini was found in only one A. lacustris from a high exposure treatment, sampled during week 3.

Host reproduction

Fecundity, assessed as the mean number of eggs per female in each treatment (mesocosm replicates pooled), did not differ between high and low exposure treatments in P. fluviatilis on any of the three sampling dates (Table 2). The number of paired P. fluviatilis did not differ between treatments in week 3, but there were more pairs in the low exposure treatment than in the high treatment mesocosms in week 6 and 9 (Table 2). Further analyses are provided in the online Supplementary Information.

Discussion

Elucidating the role of parasites in the structure of entire communities, and eventually ecosystems, is key to a greater understanding of the functioning and structure of ecosystems. Empirical, carefully controlled, multigenerational experiments are fundamental to reveal the impact of parasites in shaping natural systems. Our mesocosm experiment demonstrated that parasites can indeed shape their host community, impacting recruitment and relative abundance of hosts and non-host species. Throughout the experiment, the differences in both relative abundance and recruitment between low and high parasite exposure treatments were large, indicating our focal parasite, M. poulini, influenced community structure. Parasites can have indirect impacts on a community, through modified competitive or predatory interactions. It is very likely that modifications to these interactions also played a role in the differences observed in the communities experiencing different parasite exposure.

Both M. poulini and C. parvum appeared to have fitness consequences on the amphipod P. fluviatilis, based upon the results of this study. Previous work has also shown that M. poulini reduces the survival of this amphipod host (Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2017). Consistently, we saw fewer P. fluviatilis amphipods surviving in the high exposure treatments. Interestingly, there appeared to be no difference in the mean number of eggs per female or the number of females with eggs between treatments, although previous studies have indicated P. fluviatilis with higher parasite abundance (C. parvum or M. poulini) were more likely to have eggs (Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2017). This relationship was only consistently present in the low exposure treatment, suggesting other factors may be at play in the high exposure treatments. Pairing was also found to be more frequent in the low exposure mesocosms. Parasites may be mediating this relationship and affect the successful reproduction of their host (Bollache et al., Reference Bollache, Gambade and Cézilly2001). Parasites can interfere with male–male competition, and reduce the ability of males to form precopulatory pairs (Bollache et al., Reference Bollache, Gambade and Cézilly2001; Rauque et al., Reference Rauque, Paterson, Poulin and Tompkins2011). The energetic consequences and behavioural impacts of infection may also reduce the frequency of pairing (Zohar and Holmes, Reference Zohar and Holmes1998; Bierbower and Sparkes, Reference Bierbower and Sparkes2007; Rauque et al., Reference Rauque, Paterson, Poulin and Tompkins2011). Finally, we also saw a difference in recruitment between low and high exposure treatments. Although, we were unable to examine the impact of parasites in driving selection on the genotypes of their host (Roitberg et al., Reference Roitberg, Boivin and Vet2001), their ability to affect the survival, reproduction and recruitment of P. fluviatilis strongly suggests that M. poulini impacts the amphipod's fitness, which likely has ramifications across the community.

The shifts in parasite abundance and prevalence within treatments over time were likely due to a number of factors, including variation in M. poulini cercarial output, host density and mainly differential survival rates of infected vs uninfected hosts. The decrease in M. poulini abundance and prevalence in P. fluviatilis over time in both treatments may be due to parasite-induced mortality in combination with a higher number of hosts, diluting the actual number of parasites reaching each host. In the low exposure treatment, recruitment and immigration (20 P. fluviatilis added weekly per tank of both exposures) were high enough to continue to increase the overall host abundance, but in the high exposure treatment, P. fluviatilis populations did not increase in size over time despite recruitment and immigration. Interestingly, in the other amphipod, P. excavatum, the difference in M. poulini abundance between low and high exposure treatments decreased over time, with mean parasite abundance nearly identical in the last sampling period, yet host population size remained roughly constant. The relationship is not consistent with what we would expect from greater parasite infections in the high exposure treatment mesocosms, but no additional mortality between treatments was observed. Absence of parasite-induced mortality in this larger-bodied host is the most likely explanation (Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2017).

The differential parasite virulence between the two amphipod host species was accentuated within these communities. The population of P. excavatum did not fluctuate with parasite exposure, while the population of P. fluviatilis was strongly impacted by higher exposure to the same parasite species (Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2017). The classical study by Park (Reference Park1948) demonstrated that infection by a shared parasite, Adelina tribolii, reversed the outcome of competition between two host species (T. castaneum and T. confusum). Our amphipods showed a parallel association (Fig. 2a), where higher exposure to a shared parasite altered the relative abundance of each species, with the abundance of P. fluviatilis decreasing, while P. excavatum increased.

Impacts of parasites on the isopod A. annectens were subtler than the dramatic differences seen in the amphipod P. fluviatilis. The absolute abundance of A. annectens initially was similar between the two treatments, but overtime populations decreased in the higher exposure treatments. Although we have not previously been able to measure an energetic cost to infection in A. annectens, a higher abundance of M. poulini in this isopod increases their activity levels (Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2017). The combination of dietary stress, possibly due to decreasing availability of P. fluviatilis, with higher parasite abundance may have eventually led to higher mortality of A. annectens (Esch et al., Reference Esch, Whitfield Gibbosn, Bourque, Gibbons and Bourque1975; Lafferty and Kuris, Reference Lafferty and Kuris1999; Coors and De Meester, Reference Coors and De Meester2008; Goulson et al., Reference Goulson, Nicholls, Botías and Rotheray2015). Conversely, the abundance of the other isopod, A. lacustris, became higher in the high exposure treatments. The higher abundance of this isopod in the higher exposure treatments may be linked to competitive release as populations of its competitor, A. annectens start to decrease.

Parasite-mediation of pairing success occurred in two of our host species, A. lacustris and P. fluviatilis. The direct role of parasites in altering pairing success has been previously documented in other systems (e.g. Zohar and Holmes, Reference Zohar and Holmes1998; Bollache et al., Reference Bollache, Gambade and Cézilly2001), and may play a role in reduced pairing by P. fluviatilis. However, as A. lacustris is a very rare host (<1%; Goellner et al., Reference Goellner, Selbach and Friesen2018), the difference in pairing success in this species may be due to indirect effects of infected competitors. Past studies have suggested that M. poulini in A. annectens affects the distribution of A. lacustris, and mediates the competition between these species (Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2018). Behavioural alterations in A. annectens, when infected by M. poulini, including increased activity levels and possible changes to their aggressiveness, are likely behind the altered microhabitat preferences of A. lacustris (Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2017, Reference Friesen, Poulin and Lagrue2018). It is possible that the same changes in behaviour may reduce pairing frequency in A. lacustris, eventually having longer-term consequences in terms of reduced mating success and recruitment in communities with high parasite abundance, although this may be balanced by high survival rates of this non-host species.

The relative abundance of species within our mesocosms fluctuated between the two treatments, showing that the relative abundance of host species was altered by parasite mediation within the system. Differences between communities were already evident on the first sampling date and became much more pronounced as the experiment continued. Both isopod species and P. excavatum achieved a higher proportion of the community when the exposure to parasites was higher. The asymmetrical impacts of M. poulini on the different crustacean hosts had consequences for the structuring of the entire community. In the long run, as the amphipod P. fluviatilis is numerically more abundant, parasites may well promote host co-existence (Hatcher and Dunn, Reference Hatcher and Dunn2011).

Seasonal and temporal fluctuations in M. poulini prevalence in its natural host community may in turn have cascading effects on host community composition and dynamics. Direct and indirect consequences of parasite mediation will vary in time, possibly leading to large fluctuations in host populations. Temporal variations in parasite communities have been shown to impact host demographics in other systems (Grunberg and Sukhdeo, Reference Grunberg and Sukhdeo2017). It is thus likely that they will affect top-down and bottom-up trophic interactions within this community (Hunter and Price, Reference Hunter and Price1992). Changes in invertebrate host populations have implications for other species such as fish and birds that use crustaceans as important food resources but are also definitive hosts to many parasites. These changes likely will also have consequences on bottom-up interactions, such as nutrient cycling and aquatic primary production (Hunter and Price, Reference Hunter and Price1992).

The experimental manipulation of a single focal parasite in our study system altered community structure, through a multitude of both direct and indirect effects as well as interactions between hosts. Variable exposure to the trematode M. poulini influenced the relative abundance of these hosts. Although we were able to examine the role parasites played in the ecology of these specific intermediate hosts, in natural systems they do not occur alone. The presence of predators, and many other abiotic factors, such as temperature and salinity, add complexity to these relationships (Kunz and Pung, Reference Kunz and Pung2004; Médoc et al., Reference Médoc, Rigaud, Bollache and Beisel2009; Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Jensen and Mouritsen2011).

Parasites play a vital role in community ecology, yet their role is often ignored or oversimplified (Hatcher et al., Reference Hatcher, Dick and Dunn2012). Although parasites may be responsible for negative impacts on their hosts, they also have the ability to affect interspecific interactions and community dynamics, ultimately increasing biodiversity, network stability and mediating species coexistence (Mouritsen and Poulin, Reference Mouritsen and Poulin2005; Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Dobson and Lafferty2006; Hatcher et al., Reference Hatcher, Dick and Dunn2012, Reference Hatcher, Dick and Dunn2014; Médoc et al., Reference Médoc, Firmat, Sheath, Pegg, Andreou and Britton2017). The role of parasites in a system can be similar to that of regulating predators; parasites can shape and regulate community structure. Overall, just like producers and free-living consumers, parasites are an integral part of any ecosystem, and as this study clearly demonstrates, omitting parasites from ecosystem studies results in an incomplete picture of community dynamics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182019001483.

Acknowledgements

Field and laboratory assistance was provided by Bronwen Presswell, Jerusha Bennett, Christian Selbach and Brandon Ruehle. Special thanks to Rita Grunberg, Peter Morin, Kelsey O'Brien, Bronwen Presswell and Christian Selbach for comments and advice on drafts of this manuscript. We are also grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions on previous versions of the manuscript.

Financial support

Financial support for this project was provided by the Department of Zoology, University of Otago.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guides on the care and use of laboratory animals.