Introduction

Population decline and regional abandonment are often associated with migrations, warfare and environmental change (Cameron & Tomka Reference Cameron and Tomka1993; Faust & Ashkenazy Reference Faust and Ashkenazy2009; Barberena et al. Reference Barberena, McDonald, Mitchell and Veth2017; Middleton Reference Middleton2017). Archaeologists studying regions such as the U.S. Southwest during European colonisation, the Circum-Alpine Late Neolithic and the Greek mainland at the end of the Late Bronze Age have relied heavily on intensive absolute dating to demonstrate extensive population decline across entire regions (Shennan Reference Shennan2000; Middleton Reference Middleton2015; Liebmann et al. Reference Liebmann, Farella, Roos, Stack, Martini and Swetnam2016). A variety of site types, however, need to be radiocarbon-dated to establish accurately whether, and to what extent, a region underwent population decline. On that basis, this article challenges the evidence for population decline during the Bronze Age of the Great Hungarian Plain.

Towards the end of the Early Bronze Age on the Great Hungarian Plain—c. 2000 cal BC in most chronologies, although this varies by region—a portion of the region's population lived in densely packed houses on fortified tells. During this time, regional populations grew, fortified tell settlements expanded horizontally and many other surrounding non-tell settlements were established (Duffy Reference Duffy2014, Reference Duffy2015). The surge in the occupation of this region was accompanied by intensification in metallurgy and craft production (Bóna Reference Bóna, Bóna and Raczky1994; Michelaki Reference Michelaki2008; Fischl et al. Reference Fischl, Kiss, Kulcsár, Szeverényi, Meller, Bertemes, Bork and Risch2013; Duffy Reference Duffy2014; Nicodemus Reference Nicodemus2014). This population expansion did not last, however. In the current chronology for the Great Hungarian Plain, the end of the Middle Bronze Age saw the abandonment of tells (most by 1500/1450 cal BC), followed by a substantial drop in the number of non-tell sites during the first centuries of the Late Bronze Age (Jankovich et al. Reference Jankovich, Medgyesi, Nikolin, Szatmári and Torma1998; Earle & Kolb Reference Earle, Kolb, Earle and Kristiansen2010; Fischl et al. Reference Fischl, Kiss, Kulcsár, Szeverényi, Meller, Bertemes, Bork and Risch2013: 360; Gogâltan Reference Gogâltan, Németh and Rezi2015). Many other cultures around Europe and the Mediterranean also experienced drastic change at this time.

Some archaeologists have assumed that social collapse prompted high rates of migration across Europe (Risch & Meller Reference Risch and Meller2015). Yet, in the case of the Great Hungarian Plain, the argument for outmigration is based exclusively on radiocarbon dating of the abandonment of tell settlements, assuming that they are representative of all sites, but this ignores the evidence from non-tell sites. In this article, we present the results of radiocarbon dating of mortuary ceramics from a recently excavated Middle Bronze Age cemetery in eastern Hungary, finding little evidence for regional mass depopulation at the beginning of the Late Bronze Age. We then build a chronology for the non-tell site of Békés 103—the first Middle Bronze Age cemetery to be excavated and dated absolutely in the Lower Körös Basin of eastern Hungary and western Romania. The resulting chronology suggests that depopulation at the end of the Middle Bronze Age in this part of the Great Hungarian Plain may be a misconception resulting from previously inadequate dating of non-tell contexts. The result in eastern Hungary, and perhaps for other regions, is that a radical change in settlement pattern took place around 1500/1450 BC, but with no corresponding drop in local population. The implication is that people left the population aggregations at the tells, and dispersed across the surrounding landscape to ‘flat’ sites.

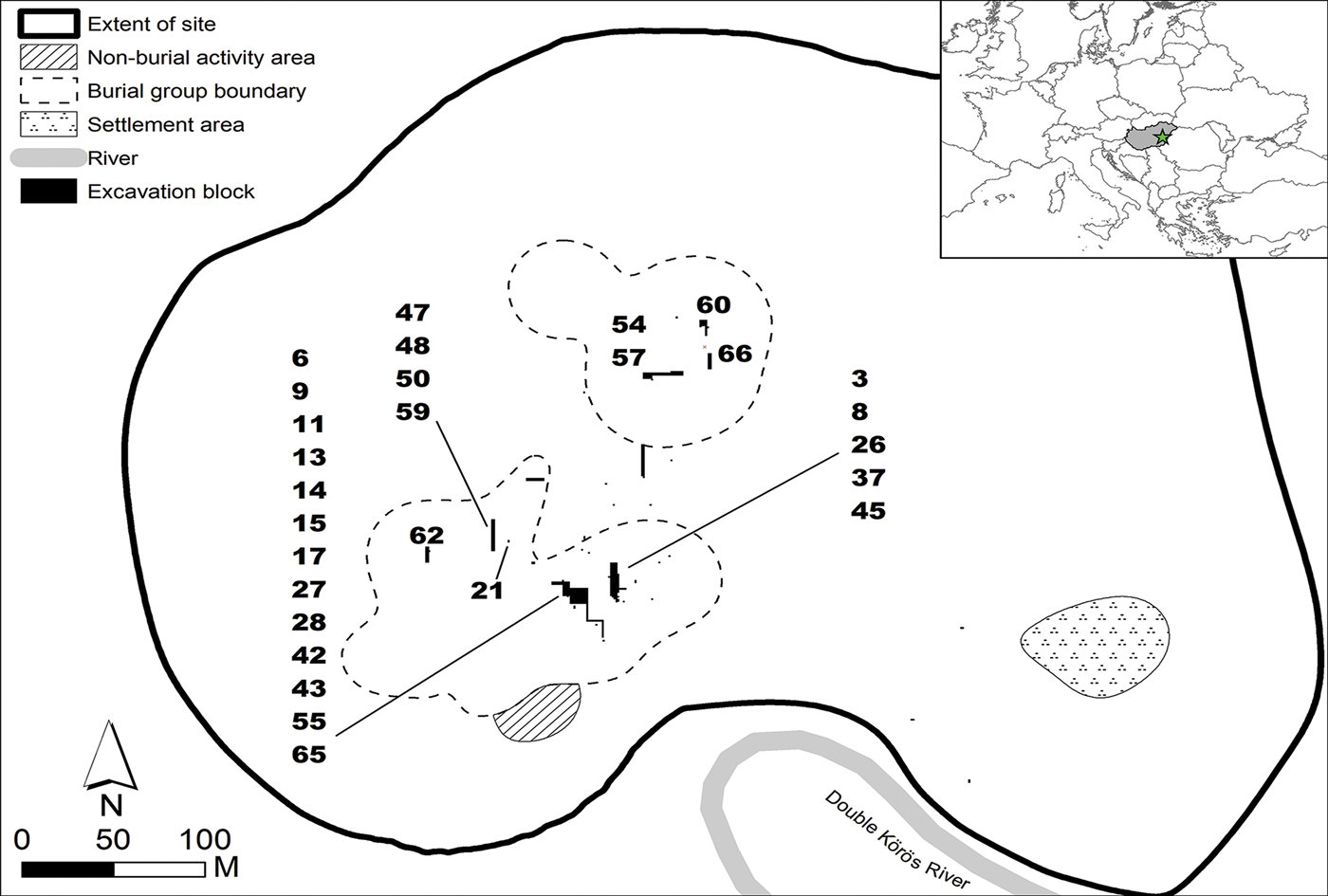

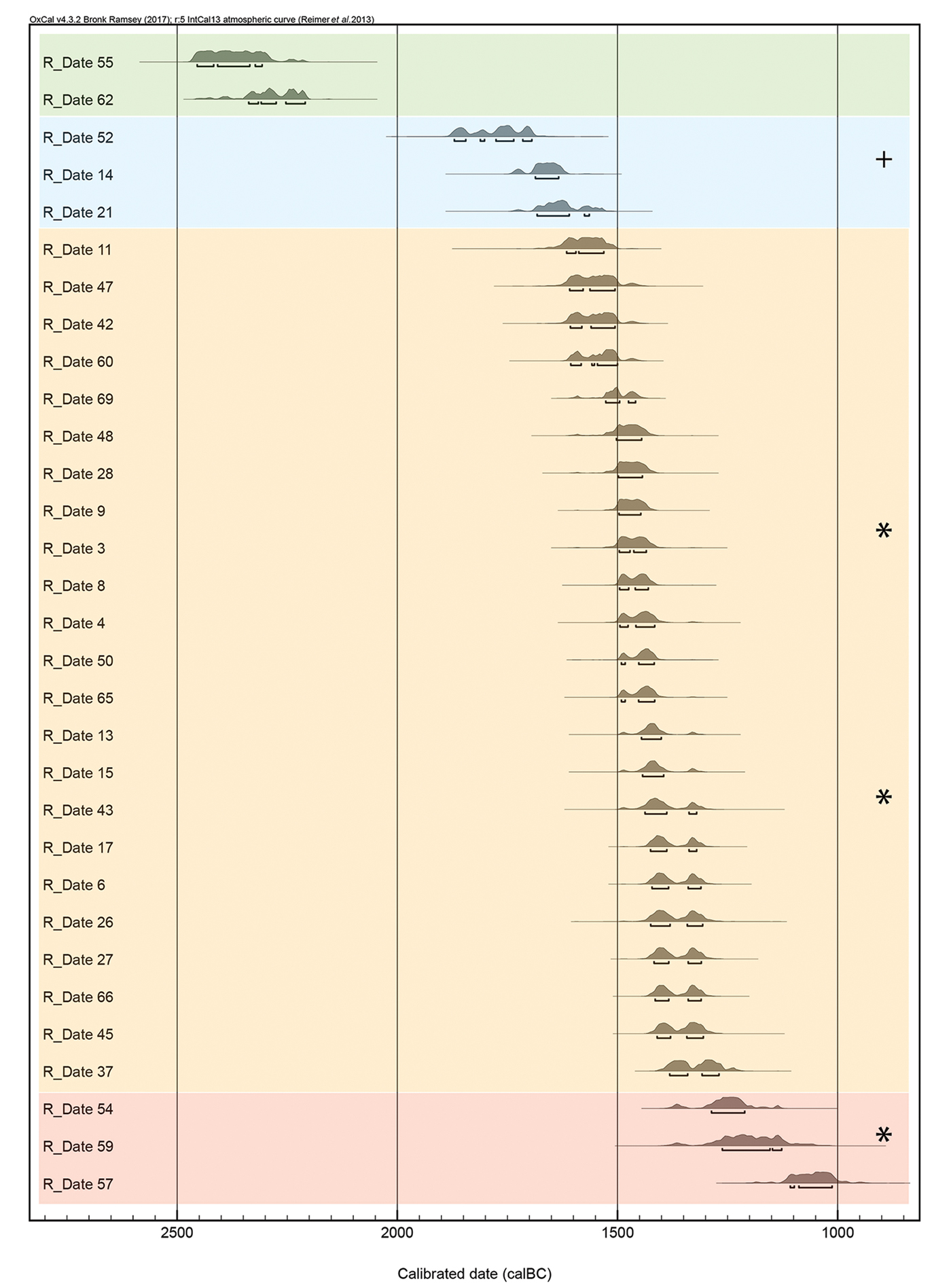

We used OxCal 4.3.2 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and the IntCal 13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards and Friedrich2013) to plot the stylistic attributes of 95 vessels from 31 graves with radiocarbon dates from the Békés 103 (Jégvermi-kert, Lipcsei-tanya) site in eastern Hungary, near the modern town of Békés (Figure 1). We find that many Middle Bronze Age motifs continued to be used long after people had left the tells. Consequently, we argue that many of the non-tell sites—known only from surface collections—are probably of later date than currently believed. Furthermore, we argue that in the Lower Körös Basin, the Middle Bronze Age saw a shift in settlement away from tells c. 1500/1450 cal BC, with no corresponding change in material culture; ceramic stylistic traditions probably continued to c. 1300 cal BC. People living at flat settlements therefore probably represent the seed population for the numerous settlements known from the Late Bronze Age. In short, there is no Middle Bronze Age depopulation to be explained.

Figure 1. The Békés 103 site displaying the approximate location of human burials (numbers) with analysed radiocarbon samples. The location of Békés 103 is marked on the inset map with a star (figure by P.R. Duffy).

Style and the end of the Middle Bronze Age

The iconic spirals and lugs of the Middle Bronze Age in the Lower Körös Basin are well-known decorations found in discussions of pan-continental symbolism, contact and trade; archaeologists have long used such stylistic features of Bronze Age ceramics for relative dating (Childe Reference Childe1929; Bóna Reference Bóna1975; David Reference David and Roman1997; Kristiansen & Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005). Hungarian and Romanian traditions use slightly different chronological terminology for the Bronze Age, but most agree on the basic stylistic changes of ceramics during the second millennium BC (Sz. Máthé Reference Sz. Máthé, Kovács and Stanczik1988; Bader Reference Bader1998; Gogâltan Reference Gogâltan1999; Németi & Molnár Reference Németi and Molnár2002; Michelaki Reference Michelaki2008; Nicodemus & O'Shea Reference Nicodemus and O'Shea2015). In the Lower Körös Basin, the Early to Middle Bronze Age transition falls a little later than in most of the Great Hungarian Plain. In the Early Bronze Age Ottomány/Otomani I group (2150–1650 cal BC), decorative elements on fine wares are mostly geometric, including incised lines and chevrons (Duffy Reference Duffy2014: 95–100). In the Middle Bronze Age Gyulavarsánd/Otomani II–III group (1750–1450 cal BC), forms become elaborate; flared rims appear on pitchers, cup handles rise high above the rim and smoothed, uniform surfaces become sculpted bas-relief. Ceramic styles across the Carpathian Basin during the Middle Bronze Age are well known for their enormous variety of forms, techniques and combinations of elements, including a vast array of lugs, spirals, chevrons, channels and other motifs and appliqués (Bóna Reference Bóna1975; Sz. Máthé Reference Sz. Máthé, Kovács and Stanczik1988; Duffy Reference Duffy2014; Sofaer Reference Sofaer2015). Most of these diagnostic motifs and forms, however, fell out of use by the Late Bronze Age.

Our current understanding of changes in Bronze Age ceramic styles associated with radiocarbon dates in the Körös region comes almost exclusively through the chronologies built from tell sequences. Focusing on the tells is intuitive, as they appear to be the longest-lived settlements in the landscape, accumulating deposits—and height—generation after generation. Yet tells were not all abandoned at the same time—some were deserted well before 1600 cal BC (Raczky et al. Reference Raczky, Hertelendi, Veres, Bóna and Raczky1994) (see Table S1 & Figure S1 in the online supplementary material (OSM)). The latest dates for tell abandonment in the Lower Körös Basin are from Berettyóújfalu-Herpály (1614–1496 cal BC, at 68 per cent confidence) and Esztár-Fenyvesdomb (1496–1323 cal BC, at 68 per cent confidence) (Raczky et al. Reference Raczky, Hertelendi, Veres, Bóna and Raczky1994; Duffy Reference Duffy2014). Similar dates for final tell abandonment can be found in the Maros region to the south, at Pecica Şanţul Mare (c. 1545 cal BC) and Klárafalva-Hajdova (c. 1450 cal BC) (Nicodemus & O'Shea Reference Nicodemus and O'Shea2015).

The reasons for collapse of the tell system and the transition to the Late Bronze Age on the eastern Great Hungarian Plain are unclear, although this lack of clarity is not due to a dearth of Bronze Age sites available for study. Hungarian archaeologists have systematically surveyed 3800km2 of Békés County, identifying thousands of archaeological sites from surface scatters (Ecsedy et al. Reference Ecsedy, Kovács, Maráz and Torma1982; Jankovich et al. Reference Jankovich, Makkay and Szőke1989, Reference Jankovich, Medgyesi, Nikolin, Szatmári and Torma1998; Szatmári n.d.). When we tally the number of sites with diagnostic Bronze Age sherds by culture group and time frame, we can calculate site density across the duration of the Bronze Age (Table 1, with specific numbers by culture group described in Table S2). The visual representation of these densities shows a striking decrease in Late Bronze Age I (1450–1200 cal BC) sites—a pattern similarly suspected for parts of the Great Hungarian Plain that lack systematic survey data (Figure 2). The first substantial Late Bronze Age occupation in the Lower Körös Basin is the Gáva group (in Late Bronze Age II, 1200–900 cal BC)—contemporaneous with the Urnfield culture in Central Europe and Transdanubia—when large numbers of settlements appear once again (V. Szabó Reference V. Szabó and Visy2003).

Figure 2. A chronology of Bronze Age occupation in Békés County according to the current typo-chronology (see Table S2 for period definitions) (figure by P.R. Duffy).

Table 1. Site density in Békés County by major Bronze Age phase. Early Bronze Age I includes sites described as culture group ‘Makó, Nyírség’; Early Bronze Age II includes sites described as ‘Hatvan, Ottomány’; Middle Bronze Age includes sites described as ‘Gyulavarsánd, Koszider, Hajdúsámson’; Late Bronze Age I includes ‘Hajdúbagos, Tumulus’; and Late Bronze Age II includes ‘Pre-Gáva, Gáva’ (Ecsedy et al. Reference Ecsedy, Kovács, Maráz and Torma1982; Jankovich et al. Reference Jankovich, Makkay and Szőke1989, Reference Jankovich, Medgyesi, Nikolin, Szatmári and Torma1998; Szatmári Reference Szatmárin.d.). Site numbers also include unpublished sites in the Mihály Munkácsy Museum database, identified since publication of the systematic surveys.

Unless the density of villages and the sizes of sites varied radically between each period of the Bronze Age, it is straightforward to interpret declining site numbers as evidence for the depopulation of, and possible outward migration from, the Great Hungarian Plain at the end of the Middle Bronze Age. The problem with this conclusion, however, is that radiocarbon dates from the Körös region come exclusively from tells; there are no radiocarbon dates from non-tell sites, and, consequently, the surface ceramics found at the latter are attributed dates by comparison with the material from the tells. In other words, this approach makes it impossible to recognise activity at non-tell sites independently of the tells.

The Békés 103 site

The Békés 103 cemetery is located at the confluence of the Black (Fekete-) and White (Fehér-) Körös Rivers in an area of dense Middle Bronze Age settlement (Duffy et al. Reference Duffy, Parditka, Giblin, Paja and Salisbury2014). These rivers drain the Apuseni Mountains in Transylvania to the east, the home of the contemporaneous Wietenberg group (Ciugudean & Quinn Reference Ciugudean, Quinn, Németh and Rezi2015). The Apuseni Mountains were probably a source of gold, copper and salt for Körös Bronze Age people (Ardeleanu et al. Reference Ardeleanu, Pascu and Pandele1983; Földessy & Szebényi Reference Földessy and Szebényi2002; Harding & Kavruk Reference Harding and Kavruk2013).

The site of Békés 103 was initially discovered through systematic fieldwalking by Hungarian archaeologists (Jankovich et al. Reference Jankovich, Medgyesi, Nikolin, Szatmári and Torma1998), although the Bronze Age cemetery was not discovered at this time (Duffy et al. Reference Duffy, Parditka, Giblin, Paja and Salisbury2014). In 2011, we identified burnt human bone on the ground surface; since then, we have systematically collected cremated bone from across 3.2ha of the site (Figure 1). In the west of the site, there are two large areas of burnt human bone on the surface, and one small area of ceramics and animal bone, with no associated cremated human remains. There is no human bone on the surface in the eastern half of the site, although there is a small area of Bronze Age settlement debris, including burnt daub.

Most areas of the site where bone was found on the surface were sampled via excavation. Overall, the density of the burials discovered by excavation was very low, with an average 1 × 20m excavation block containing only 1–2 graves. Given the distribution of surface bone, however, we estimate that the cemetery was large and used by several communities within at least 8km of the site (Duffy et al. Reference Duffy, Paja, Parditka and Giblinin press). Between 2011 and 2015, excavations at the Békés 103 cemetery recovered 68 human burials. Of these, five were inhumations and 58 were cremations in urns; two graves were represented by scattered cremains next to whole pots and/or liquid containers. In three very disturbed graves, the burial type was not obvious, although two involved cremations (Paja et al. Reference Paja, Duffy, Parditka and Giblin2016).

Analysis of the dates for Békés 103

A radiocarbon analysis of mortuary contexts is an ideal method of tracking stylistic changes that occurred over the course of the Bronze Age. Graves are closed contexts and allow confident study of the relationship between restorable ceramics and datable bone. Nonetheless, most of the dated bone from Békés 103 was calcined during cremation, and therefore requires careful screening due to the calcification of other environmental carbon during combustion and the precipitation of carbon-based salts from the burial environment (for further details, see the OSM). Although alternative sources of carbon dating are rare at Békés 103, we attempted to assess the potential impact of these diagenetic processes by double dating one burial (human burial 14)—comparing results between charcoal and burnt bone—and acquiring dates from three inhumation (i.e. non-cremated) burials. Ceramics from Békés 103 exhibit several of the most common stylistic elements of the Middle Bronze Age. In selecting graves for radiocarbon dating, we made sure to include samples associated with these common elements, as well as the rare forms and decorations that may date to the earliest and latest phases of cemetery use. We also attempted to mitigate against spatial bias by dating several parts of the site, as different areas of long-lived cemeteries may have diverse use-histories. Ceramics from the 68 burials excavated include approximately 124 restorable vessels, comprising mostly urns, jugs, cups and bowls. We described these vessels according to form, colour, surface treatment and decorative elements. Examples and descriptions of the latter are given in Figure 3 and Table 2, and the dated graves, vessel and ceramic attributes are listed in Table S3. The decorations included in this study are common to the Gyulavarsánd/Otomani II–III group, although many are also found in other parts of the Great Hungarian Plain. We did not attempt Bayesian modelling of the dates, as none of the graves intercut. Instead, we used the upper and lower extents of one standard deviation to bracket the use-life for different stylistic elements. Although further excavation and dating of the site will probably alter the phasing provided below, we argue that our attempts to overcome potential biases, combined with the sizeable sample of dated graves, means that the overall pattern should nonetheless hold.

Figure 3. Visual depiction of decorative elements from grave ceramics (drawings by D. Kékegyi & K. Gillikin, arrangement by P.R. Duffy).

Table 2. Description of decorative elements used in the study.

Chronology for Békés 103

We present the uncalibrated radiocarbon age BP and ± values for the 31 human burials (HB) in Table 3, and we list the calibrated dates in Table S4. Although cemetery use does not seem to have been continuous, it lasted about 1350 years from beginning to end. According to the earliest calibrated date, the cemetery was first used as a burial ground between 2460 and 2300 cal BC (68 per cent confidence), with final use between 1110 and 1010 cal BC (68 per cent confidence).

Table 3. Uncalibrated radiocarbon samples from Békés 103. (UG CAIS is the University of Georgia Center for Applied Isotope Studies; UA AMSL is the University of Arizona Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory.)

Both charcoal and cremated bone from HB 14 were dated, and the results suggest that cremated bone at Békés 103 is not differentially affected by diagenesis. While we would like to support this with additional paired datings, charcoal associated with calcined bone is exceedingly rare in the graves. Nonetheless, the correspondence in date between unburnt and cremated bone (Figure 4) suggests that there is no systematic distortion of dates from cremations.

Figure 4. Calibrated data showing phases 1, 3, 4 and 5 (duplicate data for HB 14 and 52 not shown); phase 2 is a period of no mortuary features; * represents radiocarbon dates from unburnt bone in inhumation graves; and + represents a grave with both dated charcoal and calcined bone providing identical dates (output by OxCal 4.3, coloured by P.R. Duffy).

Table 4 presents the ceramic decoration dates, allowing immediate comparison with ceramics from other sites—especially sherds from surface collection and settlement excavations, from which information on full ceramic form is not usually available. The absence of certain motifs in different time frames is not chronologically meaningful. The absence of the chevron before 1500 cal BC, for example, or the gap in incised decoration between 2300 and 1900 cal BC, is not particularly important in a regional sense, as these motifs have been radiocarbon dated in other contexts (Raczky et al. Reference Raczky, Hertelendi, Veres, Bóna and Raczky1994; Duffy Reference Duffy2014). But some of the ceramic decorations common to the Middle Bronze Age, such as the tick, begin surprisingly early and persist for a long time (about 1000 years). More surprising, however, is the lateness of some of the decorative elements, such as the boss and the spiral, which may have lasted into the thirteenth or twelfth century cal BC.

Table 4. Calibrated data for Békés 103 individual decorations, and the number of graves containing the decorative element.

Table 5 and Figures 4–6 provide phasing for the Békés 103 cemetery. Phase 1 (2460–2200 cal BC) is the initial period of Early Bronze Age use, during which the Makó ceramic style was common across large stretches of Hungary and Romania (Kulcsár & Szeverényi Reference Kulcsár, Szeverényi, Heyd, Kulcsár and Szeverényi2013). The earliest graves—HB 55 and HB 62—contain vessel forms unlike any other in the cemetery (Figure 6). The vessel from HB 55 is typologically comparable to Early Bronze Age forms dated to the mid third millennium from Berettyóújfalu-Nagy-Bocs (Dani & Kisjuhász Reference Dani, Kisjuhász, Anders and Kulcsár2013: pl. 6, 1), and radiocarbon dated to c. 2500 cal BC. The urn from HB 62 is similar to grave 4 from Sárrétudvari-Őrhalom, which is radiocarbon dated to c. 2700 cal BC (Dani & Nepper Reference Dani and Nepper2006: fig. 4). Both phase 1 Early Bronze Age graves at Békés 103 belong to the Makó group, which precedes the Ottomány culture. Phase 1 cemetery use may have lasted only about 50 years and probably reflects a low regional population that left very few traces on the landscape—a pattern also seen in other parts of the Great Hungarian Plain. This is followed by phase 2 (2200–1880 cal BC), an approximately 320-year period during which there is no evidence of cemetery use. Given our attempt at spatial sampling, it seems very unlikely that if burials dating to this period were eventually to be found that they would represent a large proportion of the total number.

Figure 5. Mortuary ceramics falling within phases at Békés 103 (restoration and photographs by L. Gucsi, arrangement by P.R. Duffy).

Figure 6. Simplified illustration of phases at Békés 103 (bottom), with individual attributes displayed using 68 per cent confidence for the calibrated burial dates (top). Attributes are overlaid with existing Early, Middle and Late Bronze Age sub-phase boundaries for the Körös region (figure by P.R. Duffy).

Table 5. Phases assigned to Békés 103.

The cemetery was re-used in phase 3 (1880–1600 cal BC) during the Ottomány and Ottomány–Gyulavarsánd transition, when both styles are present in the Lower Körös Basin (Duffy Reference Duffy2014: 98). This phase has only three burials, one of which (HB 21) has a recognisably early ceramic style; the urn from this grave is unique in the excavated assemblage, displaying an early spiral decoration on a double-handled biconical form—similar to vessels in the Otomani III group in north-western Romania (Németi & Molnár Reference Németi and Molnár2012: pls 7, 90–93). The other two graves, inhumation HB 52 and cremation HB 14, contain ceramics that would generally be considered to be of Middle Bronze Age date. Phase 4 (1600–1280 cal BC) represents the most intensive use of the cemetery—a period of around 320 years—and the ceramics seem characteristically Middle Bronze Age. The majority of the unexcavated burials at Békés 103 probably fall within this period, straddling the Middle–Late Bronze Age transition.

Phase 5 (1280–1010 cal BC) is the final phase, and contains ceramic forms plausibly attributed to either the Middle Bronze Age or Late Bronze Age (Kemenczei Reference Kemenczei1979: pl. XVIII:9; Furmánek et al. Reference Furmánek, Veliačik and Vladár1999: pl. 41.1). The cup in HB 57 has a high-handle and vertical channelling found in the Middle Bronze Age of the Lower Körös Basin, while the cup shape in HB 59 resembles known Late Bronze Age forms. The radiocarbon date for HB 54 clearly falls in this phase too, although its urn form and style are less diagnostic.

Implications of the chronology for settlement history

The first aim of this paper was to build a plausible chronological model for Békés 103, a large, newly discovered Bronze Age cemetery in an area where no other such examples were known. Based on the radiocarbon data and the stylistic range of ceramic material, we distinguished five phases. Our second goal was to attempt to address the putative drop in population size at the end of the Middle Bronze Age in Békés County. Our data suggest that Middle Bronze Age ceramic attributes, such as spirals and bossing, persisted for much longer than previously thought. In the current typo-chronology, for example, most of the identified Békés 103 ceramics belonging to phase 4 would be dated routinely to 1750–1500 cal BC—during the height of the tell site occupation; our data place them between 1600 and 1280 cal BC. Given our new dates for these ceramics, we can redraw the changes in site density (Figure 3) using 1300 cal BC as the boundary between the Middle and Late Bronze Ages. This reduces the sites per 100 years in the Middle Bronze Age from 52 to 29, and raises the sites per 100 years in the Late Bronze Age I from 13 to 38 (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Bronze Age site density in Békés County (black line) according to revised chronology. Current typo-chronology shown via the dashed line (figure by P.R. Duffy).

Our findings suggest that many of the hundreds of ‘Middle Bronze Age’ sites known from surface collection in Békés County are probably younger than expected. Hence, the population increase between the Early and Middle Bronze Age would be less dramatic than previously proposed (Duffy Reference Duffy2014: 226–27). Consequently, the substantial depopulation of the area—thought to have taken place at the end of the Middle Bronze Age—may be an erroneous conclusion based on survey data and an inaccurate relative chronology (see similar warnings by Fischl et al. (Reference Fischl, Kiss, Kulcsár, Szeverényi, Meller, Arz, Jung and Risch2013: 358–59, 2015)). We suggest that ideological changes in Europe around 1600 cal BC—at least initially—may have corresponded only with the abandonment of tell settlements, and not non-tell sites. While archaeologists still need to explain the local transformation that took place when the Lower Körös Basin tells were abandoned, we hope that our results encourage others to study the numerous Middle Bronze Age non-tell sites that post-date them, in order to build a complete picture of the region's social dynamics.

Our results also question the migration narrative for the Great Hungarian Plain at the end of the Middle Bronze Age. Over 50 years ago, Mozsolics (Reference Mozsolics1957) and Bóna (Reference Bóna1958) attributed depopulation of the Great Hungarian Plain to invasion by the Tumulus people migrating from Central Europe. This group occupied the entire Carpathian Basin and is named after their distinctive practice of burial under artificial mounds. They are still widely considered to represent a mass west-to-east migration with significant associated cultural impact, including displacement and depopulation (Csányi Reference Csányi and Visy2003). Yet more recent studies do not support catastrophic invasion scenarios (e.g. Kreiter Reference Kreiter2005); although the movement of the Tumulus group into the Carpathian Basin certainly had consequences, depopulation in eastern Hungary was not one of them.

Finally, our results indicate that reconstructions of demographic change in antiquity—even when founded on radiocarbon dates—are only as strong as the variety of contexts dated. We argue that discontinuities in the archaeological record should be investigated using different kinds of sites (c.f. Barberena et al. Reference Barberena, McDonald, Mitchell and Veth2017). Many archaeological regions rely primarily on the radiocarbon dating of the largest stratified sites to establish ceramic chronologies, which are then used to date surrounding sites located through pedestrian survey. We hope that this article demonstrates that even small temporal shifts in the use of material culture styles (e.g. 150 years later than expected) can have significant impacts on our understanding of regional demographic histories.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge research funding by the University of Pittsburgh Center for Comparative Archaeology, the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (756-2011-0060), the National Science Foundation (BCS-1460820, BCS-1226439) and the Central European Institute at Quinnipiac University. Thanks also go to the following: William Parkinson, Attila Gyucha and Richard Yerkes for supplying a previously unpublished radiocarbon date from Vésztő-Mágor to include here; the Pecica project for providing a template for ceramic coding; and to Jennifer Carpenter for improvements to the manuscript.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2018.179