INTRODUCTION

Radiocarbon (14C) dating is traditionally applied to archaeological and (palaeo) environmental studies, but atmospheric nuclear bomb testing in the 1950s and 1960s doubled the concentration of 14C in the atmosphere, resulting in a spike of atmospheric 14C (the “bomb-pulse”) that provides a unique period from the mid-1950s onwards during which biological materials can be dated to within just a few calendar years, especially if additional information is available to identify with which side of the bomb curve the calibrated date range is associated (e.g. Tuniz et al. Reference Tuniz, Zoppi and Hotchkis2004; Zoppi et al. Reference Zoppi, Skopec, Skopec, Jones, Fink, Hua, Jacobsen, Tuniz and Williams2004; Hua Reference Hua2009).

Bomb-pulse dating has been applied to a range of forensic investigations, including estimating the year of birth and/or date of death for human skeletal remains (e.g. Wild et al. Reference Wild, Arlamovsky, Golser, Kutschera, Priller, Puchegger, Rom, Steier and Vycudilik2000; Spalding et al. Reference Spalding, Buchholz, Bergman and Druid2005; Cook et al. Reference Cook, Ainscough and Dunbar2015) and the turnover of bodily tissues for medical applications (e.g. Spalding et al. Reference Spalding, Arner, Westermark, Bernard, Buchholz, Bergmann, Blomqvist, Hoffstedt, Näslund, Britton, Concha, Hassan, Rydén, Frisén and Arner2008), as well as analysis of wine and whisky vintages (e.g. Schönhofer Reference Schönhofer1989; Tuniz et al. Reference Tuniz, Zoppi and Hotchkis2004), the biological composition of hydrocarbon fuels (e.g. Dijs et al. Reference Dijs, van der Windt, Kaihola and van der Borg2006) and the time of harvest of illicit drugs (e.g. Tuniz et al. Reference Tuniz, Zoppi and Hotchkis2004; Zoppi et al. Reference Zoppi, Skopec, Skopec, Jones, Fink, Hua, Jacobsen, Tuniz and Williams2004).

The application of 14C dating to 20th century artworks has generally focused on the potential of the technique for detecting modern forgeries (e.g. Keisch and Miller Reference Keisch and Miller1972; Caforio et al. Reference Caforio, Fedi, Mandò, Minarelli, Peccenini, Pellicori, Petrucci, Schwartzbaum and Taccetti2014). Fedi et al. (Reference Fedi, Caforio, Mandò, Petrucci and Taccetti2013) and Hendriks et al. (Reference Hendriks, Hajdas, McIntyre, Küffner, Scherrer and Ferreira2016, Reference Hendriks, Hajdas, Ferreira, Scherrer, Zumbühl, Küffner, Wacker, Synal and Günther2018) investigated whether 14C could be used to date contemporary art, with the latter two studies dating both canvas and binder. However, these studies dated works from the start of the 20th century to the 1960s: to our knowledge, no published studies investigate any more recent works with firm dates of use for the canvas used by the artist.

One issue relating to the dating of modern artworks is the identification of the material most likely to provide a reliable date corresponding to the completion of the painting. The wooden stretchers to which canvases are attached are less likely than the canvas itself to be contaminated with carbon of different ages from priming, paint, binders and other organic substances applied by artists, but they may have an “in-built” age, or the whole stretcher might have been constructed from older, repurposed wood, or they may be later replacements. Many modern artists’ and commercial paints have a shelf life that varies from years to decades, and even if the binder is exclusively plant-based (linseed or safflower oil) its manufacture could predate the time of painting by some years. The most commonly explored material for 14C dating of paintings is the canvas support (or paper for watercolors; Keisch and Miller Reference Keisch and Miller1972), but its 14C age will relate to the harvesting of the short-lived plants used to make linen from flax or cotton duck from cotton bolls (with a one-year growth cycle), rather than the completion of the painting, resulting in a time lag of several years (Fedi et al. Reference Fedi, Caforio, Mandò, Petrucci and Taccetti2013; Caforio et al. Reference Caforio, Fedi, Mandò, Minarelli, Peccenini, Pellicori, Petrucci, Schwartzbaum and Taccetti2014; Hendriks et al. Reference Hendriks, Hajdas, McIntyre, Küffner, Scherrer and Ferreira2016). Care is also required to sample canvas that is not contaminated with sizing, priming, paint, varnish, conservation materials, or other organic materials which could affect the date and which might be difficult to remove during pretreatment processes.

Keisch and Miller (Reference Keisch and Miller1972) and Hendriks et al. (Reference Hendriks, Hajdas, McIntyre, Küffner, Scherrer and Ferreira2016) also dated linseed oil—a commonly used basic ingredient of the binder in historic tube paints—recovered from canvas samples and paints. However, dating of linseed oil and other binders requires detailed chemical analysis of adjacent paint samples to ensure no other carbon sources are present, such as organic pigments, varnishes, etc. (Hendriks et al. Reference Hendriks, Hajdas, McIntyre, Küffner, Scherrer and Ferreira2016, Reference Hendriks, Hajdas, Ferreira, Scherrer, Zumbühl, Küffner, Wacker, Synal and Günther2018), and samples that could be removed from an artwork are likely to be extremely small, making it currently an unsuitable substance for many 14C laboratories to date. It is also possible that, although it is often considered to have a relatively short shelf life, linseed oil that is several years old could be added to tube paint by the artist, resulting in an erroneous date for an artwork.

Regardless of the choice of material for dating, additional information is often required, such as the periods of activity or date of death of the artist, known dates of acquisition (and confirmed retention) of the artwork by trusted sources, or known exhibition and photography of the painting in question, to identify whether calibrated 14C dates are associated with the ascending or descending slope of the bomb curve.

This project was established with the aim of investigating two key questions. Firstly, how long is the time lag between the growth and harvesting of fibers later used to make a canvas, and its use by an artist? Secondly, how could 14C dating inform on an individual artist’s mode of work? Could it aid the establishment of a chronology of an artist’s work (especially during the rapid evolution that can take place in an artist’s early style, which is often accompanied with poor historical documentation)? Could questions be answered about an artist’s practice in respect to the length of time over which a specific supply of canvas may have been used and whether paintings may have been reworked over extended periods of time?

Samples of canvas were collected from 18 mid-twentieth-century artworks from the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo, Norway. Of these, two were pre-bomb artworks dating to 1948 and 1951, and the remainder dated to regular intervals throughout the bomb pulse period from 1959 to 1991. Confidence in the dates of painting was supported by known dates of acquisition by the museum, with many works bought directly from the artist (Table 1). Care was taken to choose only canvas made of natural fibers and likely to be artists’ quality linen canvas, as any synthetic fiber content would have resulted in an artificially older 14C age. Fibers heavily contaminated with paint and other materials were avoided, and all samples were prescreened with FTIR and polarized light microscopy (PLM) to identify potential contaminants before 14C pretreatment.

Table 1 Artworks sampled for this study from the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo, including the dates of birth and death of the artist, date of completion of the painting and the date of acquisition by the museum.

1 Acquired directly from artist.

2 Acquired from Foundation Bergmann.

3 Acquired from artist’s exhibition.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Samples were collected from 18 different paintings, details of which are provided in Table 1. Samples were selected from the paintings’ turnover edges, and where possible, from clean and unprimed areas. This was undertaken in order to reduce the risk of contamination with the carbon content of paints. Individual weft-fiber strands were either carefully pulled off or cut off with clean micro-dissecting scissors from the loose and frayed turnover edges. These measured between 8–30 mm in length with a weight range between 8.2 to 98.9 mg (on average weighing less than 20 mg).

FTIR

The instrument used was a Bruker Vertex 70 equipped with a mid-infra-red source, a potassium bromide (KBr) beamsplitter, a HeNe laser and a deuterated triglycine sulfate detector. The spectrometer was equipped with Pike GladiATR accessory. IR spectra were collected between 4000 and 600 cm–1 using 64, 128, and 256 sample scans and a spectral resolution of 4 cm–1.

Fiber Identification by Polarizing Light Microscopy (PLM)

Fiber samples were dispersed in Cargille Meltmount© of refractive index 1.66 and examined on a Leica DMRX polarising light microscope at magnifications of 100× to 400×. Fiber identification was performed according to standard procedural methods for longitudinal thread samples, including the modified Herzog test to differentiate bast fibers (Bergfjord and Holst Reference Bergfjord and Holst2010; Haugan and Holst Reference Haugan and Holst2013).

Radiocarbon Dating

Samples were pretreated and dated at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU). Canvas samples were inspected visually, and any surface contaminant was avoided when sampling for dating where possible. If samples were too small to completely avoid surface coatings, as much of the coating as possible was removed mechanically with a clean scalpel. Any woven samples were separated into individual fibers prior to treatment. Samples for dating ranged in size from 4.5 to 21.0 mg.

Unless FTIR and PLM analysis prior to pretreatment had identified any specific contaminants, all samples were subject to a routine organic solvent sequence consisting of acetone (45°C, 60–90 min), methanol (45°C, 60–70 min), and chloroform (room temperature, 60–80 min). Three separate aliquots of sample MS-03926 were treated, two with this aforementioned solvent wash as part of routine in-house quality assurance procedures, and one without the solvent sequence to determine whether it affected the date at all. Sample MS-02190 was also dated twice for quality assurance purposes, undergoing the same solvent sequence in both cases.

Several potential contaminants, including PVA, were detected by FTIR on two samples (MS-02871 and MS-02577), and the solvent wash was adapted to include the routine ORAU in-house procedure for PVA removal as follows: ultrapure Milli-Q™ water (50°C, 105 min for MS-02871, 4 hr for MS-02577); acetone (45°C, two separate washes of 2 hr and 75 min each for MS-02871, 2×2 hr washes for MS-02577); methanol (45°C, 2 hr 45 min); 1:1 methanol: chloroform (room temperature, 70 min).

After thorough drying for a minimum of overnight, each sample then underwent routine ABA (acid-base-acid) pretreatment (lab code UV* in Brock et al. Reference Brock, Higham, Ditchfield and Bronk Ramsey2010) as follows: hydrochloric acid (1M, 80°C, 20 min); sodium hydroxide (0.2M, 80°C, 20 min); hydrochloric acid (1M, 80°C, 1 hr); 2.5% wt/vol sodium chlorite at pH3 (80°C, 5–15 min depending on the integrity of the sample). The samples underwent thorough washing with ultrapure water after each step. After pretreatment, samples were freeze-dried, combusted, CO2 cryogenically distilled prior to graphitization and accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) 14C dated as described by Brock et al. (Reference Brock, Higham, Ditchfield and Bronk Ramsey2010).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

It was important to ensure that the samples dated in this study were natural fibers, as any synthetic content would likely be petroleum-based (and hence 14C-dead) and would result in an erroneously old date. Visual inspection established that the canvases were all of artists’ quality, and hence likely to be linen made from flax fibers. FTIR and PLM analysis demonstrated that all 18 samples in this study were natural cellulose-based, although one was identified to be linen/hemp (MS-02871) and two cotton (MS-01635, MS-02577). Full fiber identifications will be discussed further in Eastaugh et al. (Reference Eastaugh, Brock, Ford and Townsendforthcoming).

FTIR analysis detected potential contaminants in 12 of the samples. Calcite was detected on 4 (MS-02190, MS-02548, MS-02948, MS-02953) and aragonite on sample MS-02577. Traces of oil were detected in samples MS-02948, MS-02548, MS-02953, MS-02577, MS-02190, MS-03926, MS-00418, MS-02115, MS-01635 and MS-02663. Polyvinyl acetate (PVA) was detected on MS-02575, MS-02577 and MS-02871, a protein (probably an animal glue) on MS-02663, metal soaps on MS-02948, MS-02953, MS-02190, MS-00418, MS-02115, MS-02663, MS-02548 and MS-01635, and pigments including lead carbonate (on MS-02190 and MS-02663) and goethite, probably from an earth pigment (on MS-02948 and MS-02577). No contaminants were detected on MS-04056, MS-02876, MS-03595, MS-02883, MS-02781, and MS-00415.

For all samples, any visible contaminant was avoided when sampling prior to 14C pretreatment, or removed mechanically with a clean scalpel if necessary. Traces of calcite or aragonite, as well as lead carbonates, would have been removed during the acid stage of the pretreatment. The chloroform (or methanol/chloroform mix) stages of pretreatment should have removed any oil or grease, including human fingerprints. It is extremely difficult to remove PVA completely due to cross-linking with the canvas fibers (Brock et al. Reference Brock, Dee, Hughes, Snoeck, Staff and Bronk Ramsey2018), but ORAU’s in-house PVA-removal solvent extraction protocol involving water and acetone washes was employed for MS-02577 and MS-02871 (although not for MS-02575, where PVA was not detected until re-analysis of remaining untreated canvas by FTIR and PLM after dating). Metal soaps which form through interaction between pigment and paint medium as paint ages and degrades, have the same 14C origin as the paint medium. Goethite is an iron oxyhydroxide mineral that does not contain carbon, and so its removal was not vital prior to 14C dating. Any particulate matter loosely attached to the surface of the painting, such as skin flakes or other dirt, would most likely have been dislodged and decanted off during the multiple organic and aqueous washes during pretreatment, although no such materials were observed by PLM. It should be noted that, as all 18 artworks were framed and sampling was undertaken from the turnover edges of each canvas, the material dated had a degree of protection from excessive human contact and hence contamination.

14C dates were calibrated using OxCal v4.2.4. (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and calibrated date ranges are given in Table 2. All samples that gave F14C results (i.e. post 1950AD) were calibrated using the Bomb 13 NH1 curve (Hua et al. Reference Hua, Barbetti and Rakowski2013). Those with pre-bomb dates were calibrated using IntCal13 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffman, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). For all post-bomb samples except those from the apex of the bomb-peak (ca. 1963–1965 AD), a minimum of 2 calibrated date ranges are given, corresponding to the ascending and descending slopes of the curve. For many samples, the date of acquisition of the new painting directly from the artist, by the museum, excludes one of these date ranges.

Table 2 Radiocarbon dates, δ13C measurements, and calibrated date ranges for each sample. All dates were calibrated using OxCal v.4.2.4 and the IntCal13 dataset for pre-bomb dates (Reimer et al. 2103) and Bomb13 NH1 curve (Hua et al. Reference Hua, Barbetti and Rakowski2013) for F14C dates. Struck-through calibrated date ranges are not possible, dating to after the time of acquisition by the museum.

* Sample dated without initial solvent pretreatment.

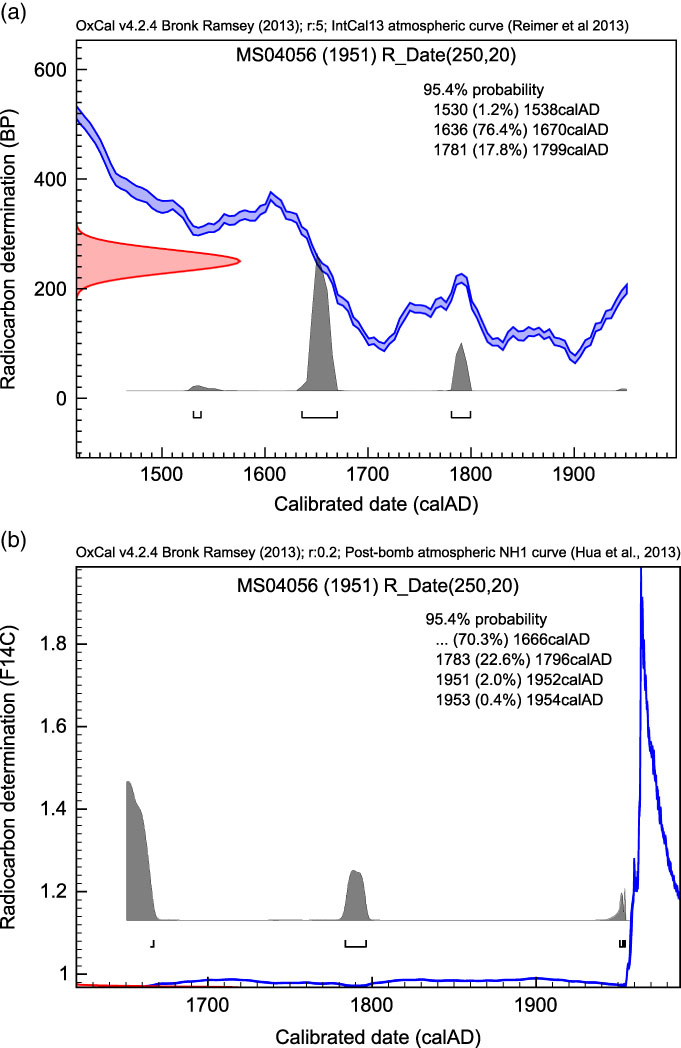

The two samples signed before the influence of nuclear bomb testing (MS-02948, signed in 1948, and MS-04056, signed in 1951) gave pre-bomb dates as expected, of 221±20 BP and 250±20 BP, respectively. While calibration with IntCal13 gives feasible dates for MS-02948, the calibrated date for MS-04056 demonstrates the difficulty of dating materials at the boundary between the IntCal and bomb calibration curves. Figure 1a shows the date calibrated with IntCal13, where the dates are clearly too old for the specimen (ranging from the 16th to 18th centuries), especially as no synthetic component was detected within the textiles fibers by FTIR or PLM.

Figure 1 Sample MS-04056, dating to 1951, calibrated using IntCal13 (a) and post-bomb 13 NH1 curve (b).

Of the 16 post-bomb artworks (dating from 1959 onwards), a total of 9 gave calibrated date ranges of 1–5 years before the date of painting. Four of these paintings also gave calibrated date ranges that could be excluded as they were after the date of acquisition by the museum. The calibrated time periods from the ascending slope of the curve were excluded for three other samples on the assumption that it was unlikely that 14–15 years (MS-02190), 18 years (MS-00418), or 32–33 years (MS-03594) had passed since the harvesting of the plant and the completion of the artwork.

It is likely that the minimum time period between the harvesting of the crop and the final dating of the painting would be around 2 years, to allow for harvesting, lengthy processing (retting) of fibers that constituted a raw material unobtainable for a further 12 months, spinning into thread, weaving, sizing and priming in bulk, cutting and stretching, packaging, sale and transport to an artists’ supply shop, stock retention, purchase by the artist, and (sometime later) selection by the artist of a canvas for a given subject. This is consistent with the findings of Hendriks et al. (Reference Hendriks, Hajdas, McIntyre, Küffner, Scherrer and Ferreira2016, Reference Hendriks, Hajdas, Ferreira, Scherrer, Zumbühl, Küffner, Wacker, Synal and Günther2018) who reported calibrated dates of 4–5 years before completion of three paintings from the early 1960s.

Two samples were observed to have longer time lags between the harvesting of the crop and the completion of the painting, MS-02663 (6–8 years) and MS-02115 (8–10 years), which could indicate either long-term storage of the canvas by retailer or artist, or extended reworking of the paintings by the artists. Traces of oil were observed by FTIR on both these canvas samples prior to dating, most likely from binders such as linseed oil, rather than petroleum-derived, 14C-dead sources. While it is expected that this oil would have been removed during pretreatment, the possibility that trace levels remained cannot be completely excluded. However, it is highly unlikely that oil that was significantly older than the canvas remained in sufficient quantities after pretreatment to have resulted in the extended time lags between harvesting and painting observed in these instances.

Three samples, however, gave pre-bomb dates of 270±25 BP (MS-02548), 276±25 BP (MS-02575), and 307±24 BP (MS-02781). The calibrated date ranges are not consistent with artworks from the 20th century, and may indicate residual contamination of the fibers after pretreatment (especially as PVA was detected on both MS-02575 and MS-02781, and oil on MS-02548). The dates are consistent with a synthetic component to the fiber of around 40%, but it is unlikely that either oil or PVA was present in such high quantities, and neither FTIR or PLM detected the presence of synthetic fibers in any of these canvases. In other circumstances, forgers have been known to apply new paint to old canvases in order to foster an appearance of age: this would lead to a much older 14C date than the proposed date of painting. In these instances, however, it is more likely that the artists were working on older canvases.

One sample in particular, MS-02577, requires further consideration. The painting is signed 1966, but the canvas fibers give a calibrated date range of 1965–1966 calAD (95.4% probability). It is highly unlikely that the crop would have been harvested and an artist’s canvas manufactured and used within such a short time period. One possibility is that the “canvas” was an inferior, rapidly produced textile, especially as the fibers were identified by PLM to be cotton, unlike the majority of other canvases in this study. The δ13C value of –22.9‰ is also an outlier compared to the measurements on all the other samples. Although this sample was one of the more heavily contaminated canvases, most chemicals applied to the canvas would either have been of a similar age to the canvas fibers (e.g. plant-based oils in paints or varnishes) or 14C-dead (e.g. some varnishes, waxes or PVA), the presence of which would have resulted in an artificially old age. It would be extremely unlikely, if not impossible, for contamination to have produced a date too close to the time of completion of the painting.

The narrow timeframe between the calibrated date range and the date of the painting could, instead, be due to assumptions made within the calibration curve itself. The atmospheric 14C measurements used within the calibration curve dataset are deliberately taken in clean-air regions to exclude potential anthropogenic/industrial contributions, but it is unlikely that all potential canvas-fiber crops are grown in such remote locations. Just a small (e.g. 0.5%) contribution of 14C-dead contamination in an area of heavy industry could potentially be sufficient to shift the calibrated date by 1 or 2 years. This particular piece dates to just after the peak of the bomb curve in 1963, and the height of the period of atmospheric nuclear testing, and so it might also be possible that the date could be affected by the steep tropospheric gradients in atmospheric 14C at that time.

The assumption that the canvas fiber was locally grown may also not be justified in a global economy. High-quality artists’ materials purchased in Scandinavia are very likely to have been imported from one of the traditional artists’ colourmen, none of whom were based in Scandinavia. Companies such as Winsor & Newton, founded in the 19th century, had established large export markets worldwide during that period and continued to trade during the mid-20th century, from factories then largely based in the UK. Scandinavian or Norwegian manufacturers of canvas might not have concentrated exclusively on artists’ materials, and might have treated their products for alternative end-uses such as packaging or sail-making.

Taking the δ13C value, the identification of the fibers as cotton, and the calibrated date into consideration, it is likely that this canvas was made from fibers from a different geographical region, with different growing conditions, to the other canvases in this study. The Bomb13 NH1 calibration curve was chosen arbitrarily for this study given that the artworks were all by Scandinavian artists, and hence well within the NH1 region above 40°N (as defined by Hua et al. Reference Hua, Barbetti and Rakowski2013). However, the location of the artists is not necessarily a reliable indicator of the location of the canvas fiber crop, and this particular canvas may have originated in the NH2 region (between 40°N and the mean summer intertropical convergence zone), or even the NH3 region (the Northern Hemisphere Intertropical Convergence Zone), as defined by Hua et al. (Reference Hua, Barbetti and Rakowski2013). Gunderson, the artist of MS-02577, was known to travel widely in Europe in the 1940s and 1950s, including as far south as Portugal, parts of which would fit into the NH2 region. It is therefore not impossible that he sourced his canvases made from fibers grown in different regions to his contemporaries in Scandinavia. Calibration of the date for this sample using the Bomb13 NH2 curve (Figure 2) gives potential dates of 1963 (9.1%) and 1964 (7.4%) as well as 1965–1966 (79.0%), and hence a more feasible lag between the harvesting of the crop and completion of the painting of up to 3 years.

14C dates on a wider selection of works by the artist responsible for this painting, as well as the two with considerable time lags between the dates of the canvas and the finished artworks (MS-02663 and MS-02115), could provide useful insight into different working regimes of these artists compared to those whose paintings had the more common time lag of 2–5 years from the age of the canvas fibers.

It is important to note that 14C dating within the bomb-pulse period, and the transition into the period in the early 1950s, can be challenging, due to both the resolution involved (calibrating to within a single calendar year in some instances) and the difficulties in establishing calibration datasets at such resolution. For consistency, all dates within this study were calibrated using default settings in OxCal with IntCal13 and post-bomb atmospheric curves NH1 and NH2. However, in some instances the use of other calibration packages e.g. Calib or CaliBomb (Stuiver et al. Reference Stuiver, Reimer and Reimer2018), or previous datasets such as IntCal09, may result in slight variations in calibrated calendar year date ranges. Even within OxCal, using a finer resolution than the default value of 0.2 year, will further refine the calibrated dates. These issues must be considered carefully when dating materials post-1950, and it is vital that supporting information is taken into account when calibrating and interpreting dates.

CONCLUSION

The majority of the post-bomb artworks in this study demonstrated a time lag of 2–5 years between the harvesting of the crop utilized in the canvas and the completion and (optional) signing of the piece. This is a realistic time frame for harvesting, processing of fibers, retail, and selection by the artist of a canvas for a given subject. However, several artworks gave older, pre-bomb dates despite the apparent lack of synthetic fibers in the canvas, that are unlikely to be entirely due to the presence of trace levels of residual contamination from substances such as PVA. Thorough analysis of samples prior to dating—preferably by FTIR and microscopy—is recommended to identify potential sources of contamination that may affect the date of a canvas.

This study demonstrates the importance of applying the correct calibration curve to samples of modern art, and the appreciation of potential geographical origins of canvas fibers, especially in relation to the dataset used to define the calibration curve itself. Samples dating to the early 1950s and the switch from pre-bomb (e.g. IntCal13) to bomb-curve calibration data sets appear difficult to calibrate reliably. Different calibration software packages (e.g. OxCal, Calib) can also provide slightly different calibrated date ranges for the same date using the same calibration dataset depending on the default resolution settings, which may be significant for samples such as these where precision can be measured to just 1 or 2 calendar years. The museum acquisition date (as well as the date of death of the artist, or any date beyond which (s)he could not paint) can be particularly useful for identifying the correct calibrated date period for a sample, by potentially eliminating either the ascending or descending slope of the bomb curve. 14C dating may be less informative for a painting with no associated information, but may still be useful for identifying potential modern forgeries, by demonstrating the production of a fundamental component of the artwork after the death of the suggested artist or acquisition of the piece.

Given the common time lag of 2–5 years between a canvas and the completion of a painting, 14C dating appears unlikely to be suited to identifying the precise chronology of a specific artist’s corpus. But the identification of shorter or considerably larger time lags may indicate a different approach by an individual artist from their peers, or a deviation from their normal practice, and in some instances may justify further canvas analysis and/or dating of the artist’s corpus to provide more information about their mode of working.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The radiocarbon dating was funded by NRCF grant NF/2013/1/5 Investigating the potential of bomb-pulse radiocarbon dating to study culture heritage and modern art (short-form title Modern Art), and undertaken by FB while employed at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit. Bhavini Vaghji and Joanna Russell are thanked for their assistance with canvas pre-screening by FTIR and PLM, respectively. Christopher Bronk Ramsey is thanked for helpful discussions about calibrating modern 14C dates.