Part I Chronological history of French music from the early Middle Ages to the present

1 From abbey to cathedral and court: music under the Merovingian, Carolingian and Capetian kings in France until Louis IX

Music for much of the Middle Ages is mostly treated as a trans-national repertoire, except in the area of vernacular song. Nevertheless, many of the most important documented developments in medieval music took place in what is now France. Certainly, if the concept of ‘France’ existed at all for most of the Middle Ages, it did not encompass anything like the modern hexagone: French kings (or, more properly, ‘kings of the French’) usually did not directly control all the territories they nominally ruled, and southern territories in particular sought to maintain their political and cultural distinctiveness. Still, it can be useful to consider medieval music in relation to other developments in French culture. From the intersections of chant and politics in the Carolingian era, to the flowerings of music and Gothic architecture, to the growth of vernacular song in the context of courtly society, music participated in broader intellectual and institutional conversations. While those conversations did not generally have truly national goals, they took place within what is now France, among people who often considered themselves to be, on some level, French.

The Gallican rite of Merovingian France (c. 500–751)

As the Roman empire gradually disintegrated, its authority was largely replaced by local leaders and institutions. The Christian church took up some of the empire’s unifying functions, but it too was geographically fractured as communication became more difficult. A distinct Gallican liturgy can be seen even before the conversion of Clovis, the first of the Merovingian kings, around the year 500. In light of future events, it is interesting to note that the earliest document attesting to Gallican liturgy is a letter by Pope Innocent I, dated 416, requesting that the churches of Gaul follow the Roman rite, but surviving texts attest to the persistence of the local liturgy.1

While the existence of a Gallican rite is clear enough, what it sounded like is harder to determine.2 No musical sources survive, since Gregorian chant effectively suppressed Gallican melodies before the advent of notation in the ninth century. Some texts and descriptions give hints, and traces may remain within the Gregorian liturgy, but teasing out the details is difficult, and scholars do not always agree on methods or results.3 What evidence survives suggests less a single coherent rite than a heterogeneous body of materials whose specific contents may vary from place to place, perhaps sharing a basic liturgical structure but using different readings or prayers. Though it largely disappeared, Gallican chant provided the Frankish roots onto which the Roman rite was grafted to create what we know as Gregorian chant. This new hybrid was inextricably linked to Carolingian reforms.

The Carolingian renaissance and the creation of ‘Gregorian’ chant (751–c. 850)

While the effective power of the Merovingian kings declined over the seventh century, that of the mayors of the palace who ruled in the king’s name increased, until in 751 Pépin III (the Short, d. 768) definitively took the royal title himself. He sought to enhance his new royal status in part by a renewed Frankish alliance with Rome.4Pope Stephen II travelled to Francia, making the first trip of any pope north of the Alps, and in 754, at the royal abbey of Saint-Denis, he anointed Pépin and his sons. By the end of the century Pépin’s son Charles, later known as Charlemagne (r. 768–814), was the most important ruler in the West, controlling much of what is now France, Germany and Italy, and he was crowned by the pope in Rome on Christmas Day 800.5

The Carolingians took their role as protectors of the church seriously, seeking to reform religious life through the better education of clerics.6 The cultural flowering that resulted, often called the Carolingian renaissance, built on both Merovingian and Gallo-Roman roots. Monastic and cathedral schools were created to foster basic Latinity, which could be passed by parish priests to the laity, and to provide further education in the liberal arts and theology. Both patristic texts and classical works by authors such as Cicero, Suetonius and Tacitus, largely neglected in Frankish lands for a couple of hundred years, were copied in the new script known as Carolingian minuscule, developed at the monastery of Corbie.7 Not only were older texts copied, but Carolingian masters wrote new commentaries on both sacred and secular texts, as well as poetry and treatises on a wide variety of subjects. Through all this can be seen not only a concern for proper doctrine, but also an increased emphasis on the written word.

The church was also the primary beneficiary of many developments in the visual sphere.8 Liturgical manuscripts and other books were often highly decorated, both on the page and in their bindings, which may include ivory carvings or jewels. New churches, cathedrals and monasteries were built and supplied with elaborate altar furnishings, such as chalices and reliquaries. Few examples survive of textiles and paintings, but ample evidence exists of their use. Charlemagne’s court chapel at Aachen is a superlative example of visual splendour in the service of both religion and royal power.

The importing of the Roman liturgy and its chant into the Frankish royal domain was an important part of the Carolingian reforming agenda. Roman liturgical books and singers circulated in Francia as early as the 760s. The effort to displace the existing Gallican liturgy in favour of the Roman, however, was never as successful as the Carolingian rulers might have liked. The number of documents that mandate the Roman use suggests a general lack of cooperation on the part of the Franks, and the surviving books attest to far greater diversity in practice than Carolingian statements would suggest.9 Moreover, melodic differences between the earliest sources of Gregorian chant and later Roman manuscripts show that Gregorian chant is in reality a hybrid, created through the interaction of the rite brought from Rome and Frankish singers. Susan Rankin compares Gregorian and Roman versions of the introit Ad te levavi, arguing that the Gregorian version shows a Carolingian concern for ‘reading’ its text in terms of both sound and meaning to a greater degree than the Old Roman melody does.10 This fits within the Carolingian reforming ideas already seen. In any case, Gregorian chant eventually became more than just another local liturgy: it was transmitted across the Carolingian empire and beyond, and given a uniquely divine authority through its attachment to Gregory I (d. 604), Doctor of the Church, reforming pope and saint. The earliest surviving Frankish chant book, copied about 800, uses his name, and an antiphoner copied in the late tenth century provides what becomes a familiar image: Gregory (identifiable by monastic tonsure and saintly nimbus) receiving the chant by dictation from the Holy Spirit in the shape of a dove.11

The need to learn, understand and transmit this new body of liturgical song led to developments in notation and practical theory that are first attested in Frankish lands.12 The earliest surviving examples of notation come from the 840s, and the first fully notated chant books were copied at the end of the ninth century. A system of eight modes may have been in use as early as the late eighth century, as witnessed by a tonary, which classifies chant melodies according to mode, copied around 800 at the Frankish monastery of Saint-Riquier. Treatises explaining the modes and other aspects of chant theory appear in the ninth century; early examples include the Musica disciplina of Aurelian of Réôme, a Burgundian monk writing in the first half of the ninth century, and Hucbald (d. 930), a scholar and teacher from the royal abbey of Saint-Amand. In addition to chant books and treatises on practical theory, the earliest surviving copy of Boethius’s treatise on music, a fundamental source for the transmission of ancient Greek speculative theory to the Latin West, was copied in the first half of the ninth century, perhaps at Saint-Amand. The proper performance of chant, as aided by these tools, was an essential element in the education of clerics in Carolingian times and beyond.

Monastic culture under the later Carolingians and the early Capetians (c. 840–c. 1000)

By his death Charlemagne ruled much of Western Europe, but the later ninth century and the tenth century were marked by a return to local concerns, even while the authority of monarch and church were acknowledged. This attitude may be reflected in the flowering of musical creativity associated with individual religious institutions. Even as Gregorian chant took hold, new chants were created to enhance local saints’ cults, and new genres such as sequences and hymns allowed additions to established liturgies. Just as glosses became important in the second half of the ninth century as a way of commenting on texts, tropes were created to enhance existing chants, adding words and/or music to explain or expand upon the original.13 For instance, the notion of Jesus’ birth as the fulfilment of prophecy is underlined in this trope added to the Christmas introit found in a manuscript from Chartres (chant text underlined):

Polyphony, which will be discussed in the next chapter, likewise began as a way to enhance chant. While these practices can be found all over the Christian West, and some specific examples were transmitted widely, these additions to the central Gregorian repertoire were not standardised, but rather locally chosen, and often locally composed.

A major factor in the fracturing of the Carolingian empire was the common practice of dividing territory among all male heirs, rather than passing on a title only to the eldest. When Charlemagne’s son Louis the Pious died in 840, he left three sons. At the Treaty of Verdun in 843, they agreed on a division of the empire, and Charles the Bald, the youngest, inherited most of what is now France. The notion of a unified kingdom, however, was difficult to maintain as areas such as Brittany, Gascony, Burgundy and Aquitaine each held on to their own culture and traditions, and often their own laws and language. The Frankish kingdom was further challenged by Viking raids, which became more numerous from the 840s. In 845 the Vikings reached Paris, and from the 850s winter settlements can be found in the Seine valley. In 911, Charles the Bald’s grandson Charles the Simple ceded the area around Rouen, creating what eventually became the duchy of Normandy. A further crisis came in 888, when, for the first time since Pépin III became king in 751, there was effectively no adult Carolingian candidate to take the throne. After a century of conflict, Hugh Capet was elected king in 987. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that Frankish culture was located more within individual religious institutions than at a royal court.

Monasteries were particularly important sites for the creation of new types of chant, and for the study and transmission of learning in general. From Alcuin, an English monk who was Charlemagne’s chief advisor and was named abbot of Saint-Martin of Tours in 796, to Suger (c. 1081–1151), abbot of Saint-Denis and confidant of Louis VI, and beyond, churchmen were key advisors to kings. New monasteries flourished even as royal power waned, and old ones were reformed and better endowed by local patrons, who requested in return prayers for their souls and those of their relatives. The best-known reform house was founded at Cluny in 910 by William the Pious, duc d’Aquitaine.15Cluny and its many daughter houses fostered proper celebration of the Office, reinforcing the idea that a monastery’s primary work is corporate prayer. Cluniac houses, like Benedictine monasteries, cathedrals, chapels in royal palaces and other churches, were adorned with new buildings and decorations to enhance the liturgy, which was preserved in notated and sometimes decorated manuscripts. Reforming impulses also led to the formation of new orders, most notably the Cistercians in the twelfth century, and the Franciscans and Dominicans in the thirteenth. These tended to take a more austere attitude towards chant, but they too copied liturgical books.

A number of Frankish abbeys can be associated with specific musical developments. The library of the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Gall, in modern Switzerland, still holds a number of the earliest surviving manuscripts containing musical notation, as well as standard works such as Boethius’s Consolatio philosophiae, classical authors such as Cicero, Virgil and Ovid, and vernacular texts.16Saint-Gall was also the home of major early creators of tropes and sequences such as Notker and Tuotilo, and an early example of the Quem quaeritis dialogue can be found there.17 Another early centre of both troping and Latin song, as well as liturgical drama and early polyphony, was the abbey of Saint-Martial in Limoges, founded in 848. The cultural flowering associated with this monastery in the late tenth century and eleventh century included an attempt to proclaim its namesake, a third-century bishop, as an apostle. This effort, spearheaded by Adémar de Chabannes, who wrote a new liturgy for Martial, was ultimately unsuccessful, but it did enhance the fame of the abbey and its value as a pilgrimage site.18

Saint-Denis, just outside Paris, had been a royal abbey since Merovingian times, and served as burial site of many French kings.19Pope Stephen II and his schola cantorum stayed there in 754, and demonstrations of the Roman chant and liturgy probably took place at the abbey at that time. New efforts to foster Denis’s cult in the ninth century led to the conflation of the third-century bishop of Paris with the fifth-century theologian Pseudo-Dionysius, in turn linked to Dionysius the Areopagite, a Greek disciple of Paul. The octave or one-week anniversary of this enhanced Denis’s feast was celebrated by a Mass with Greek Propers, the only one of its kind. In the twelfth century Abbot Suger, a close advisor and friend to Louis VI who had been educated at the abbey, built one of the earliest manifestations of the new Gothic architectural style there, replacing a Carolingian church. Aspects of the building reflect principles of Pseudo-Dionysian thought, and a mid-eleventh-century rhymed office for Denis emphasises ‘the light of divine wisdom’ as described in the theology of Pseudo-Dionysius.20Saint-Denis did not cultivate polyphony, as the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris did, but its widespread practice of melismatic embellishments of chant can be seen as an attempt to move the singer or listener to the immaterial world, reflecting the belief that vocalisation without words approximated angelic speech and the Divine Voice.21

The Capetians and the age of cathedrals (987–c. 1300)

The focus on individual institutions as sites for musical developments continued under the early Capetians. While monasteries continued to serve an important role, urban cathedrals received increased attention, especially in the royal heartland still known as the Île-de-France. The election of Hugh Capet (r. 987–96) did not immediately lead to a resurgence of royal authority across the land, but it increased over the course of the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Primogeniture was still gaining acceptance and was not uncontested, so the early Capetians formally crowned and associated their eldest sons with them in their own lifetimes. This stability of succession allowed them time to build power. They also encouraged a new ideal of kingship: while coronation had long been seen as a sacrament, and the notion that the monarch is defender of the church had long roots, the early Capetians went a step further to build an image of the king as holy man. This can be seen in Helgaud of Fleury’s life of Robert the Pious (r. 996–1031), and in the widespread belief in the king’s touch, by which scrofula and other illnesses were said to be cured.22 The strongest manifestation of the sacralisation of kingship was the canonisation of Louis IX in 1297.

The early Capetians directly controlled only the area around Paris, but they gradually extended their geographic control westwards and southwards, and this culminated in the reclaiming of Normandy from the English kings in 1204. Philip Augustus (r. 1179–1223) further enhanced the position of Paris as his royal capital, building a new wall to protect recent growth. An economic recovery, beginning in the second half of the eleventh century, also benefited the French kings: the agricultural riches of northern France, including the royal domain, began to be realised, and trade between these areas and markets to the north, south and east was strengthened. Urban areas, especially Paris, became transportation hubs. Because cathedrals, unlike monasteries, tend to be located in cities, they benefited from this economic activity through the patronage of kings, nobles and townsfolk. New buildings were created in the new Gothic style, which encouraged liturgical and musical developments as well.

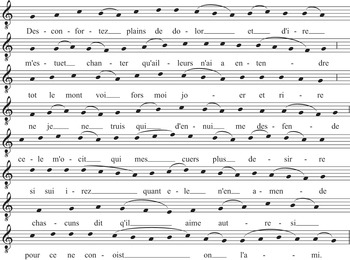

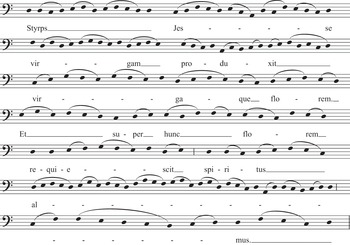

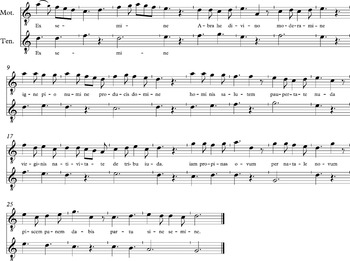

After the cathedral in Chartres burned in 1020, Bishop Fulbert (d. 1028) began work on the current building, which was also dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The Marian cult already active there was enhanced, with a new focus on the Nativity of the Virgin.23 The liturgy fashioned for this new celebration combined chants for Advent and Christmas from the traditional Gregorian repertoire with newly composed material, including three responsories attributed to Fulbert himself. The best-known of these outlines the lineage of Mary through the Jesse tree, which is spectacularly expressed in glass at the west end of the cathedral (see Example 1.1).24

The shoot of Jesse produced a rod, and the rod a flower; and now over the flower rests a nurturing spirit. [V.] The shoot is the virgin Genetrix of God, and the flower is her Son.

This melody begins by hovering around its final, D, dipping down to A at the word ‘Jesse’, in the process emphasising Jesse as the root of this genealogical tree. It then rises a little, centring on F with hints of G at the two appearances of the word virga (rod), showing how the branch lifts away from the root, but by moving downwards again links the branch to that root, as well as to the flower it produces. When the Spirit rests on that flower, it releases a luxurious melisma on the word almus (nurturing), which both rises to A, the highest note of the chant, and falls to the octave below before cadencing on the final. The effect is one of a gradual ascent, but one that is thoroughly grounded, like the Jesse tree itself. A similar process operates in the verse, which explains the image described in the respond: the melody rises to A on dei (God), then falls to flos (flower), showing how Christ ultimately serves as both culmination and source of the Jesse tree. Fulbert, or whoever composed the music, did not choose the perhaps obvious path and create a melody that rises inexorably from beginning to end through an authentic range (or that might even extend its range to show the scope of the tree’s ascent), but by using a plagal mode, with a relatively limited compass that envelops its final, he followed a different path, one that emphasises stability and rootedness.25

Example 1.1 Fulbert of Chartres, Stirps Jesse, responsory for the Nativity of the Virgin, respond only

Notre-Dame of Paris, at the heart of Philip Augustus’s capital city, is perhaps the best-known Gothic cathedral. It was renowned for its cultivation of polyphony, which will be discussed in the next chapter, but chant and other forms of monophonic song continued to be central to its liturgical life.26 Its canons had connections outside the cathedral, most notably at the abbey of Saint-Victor and the nascent university. Saint-Victor was a major centre of Augustinian reform in the twelfth century, balancing rejection of the world with serving the laity and seeking to create clerics who would teach ‘by word and example’.27 Its canons translated their reforming doctrine into liturgical song through a substantial group of sequences, many associated with Adam (d. 1146), who served as a canon and precentor of Notre-Dame before retiring to the abbey. Philip, chancellor of Notre-Dame from 1217 to 1236, wrote a number of conductus texts (for more on the conductus see below), though it is uncertain whether he wrote music, and indeed several are linked to melodies by Perotin, who will be discussed in the next chapter. Since Philip’s position brought him into contact with the university, it is not surprising that some of his conductus refer to student conflicts in the early thirteenth century.28

The growth of the University of Paris reflected a renewed concern for the proper education of clerics. Paris became the centre of a new cadre of clerks, associated with noble and royal households, educated at cathedral schools and universities and often remunerated in part through the acquisition of church benefices. University-trained clerics also enhanced the rosters of monasteries, cathedrals and other sacred foundations. This educated non-noble class, whether based at church or court or moving between the two, provided a number of the creators and performers of the written musical tradition, monophonic and polyphonic, in both Latin and the vernacular. Music as an abstract mathematical art was one of the seven liberal arts, but Joseph Dyer argues that it and the other disciplines in the quadrivium were effectively eliminated from the curriculum at the University of Paris by the mid-thirteenth century in favour of other subjects, especially Aristotelian logic.29 There is evidence, however, that university students had significant contact with practical music-making, through their early education, the liturgical practices of colleges and relationships with cathedral canons and singers of the Chapelle Royale. Peter Abelard and Peter of Blois are known to have written songs in Latin, and Abelard also composed hymns and six planctus. In perhaps the best-known witness to university-related music-making, the theorist known to us as Anonymous IV, probably a monk of St Albans in England, tells us about sacred music in Paris, especially Notre-Dame polyphony, on the basis of his experience as a university student.

Cathedrals were not the only witnesses to the Gothic style. After Louis IX (r. 1226–70) bought the Crown of Thorns from the Byzantine emperor in 1241, he built a chapel within the royal palace to house it. The Sainte-Chapelle is a masterpiece of colour in glass and paint that visibly links the French kings to those of the Old Testament and both to Christ the King.30 These connections were made in the liturgy for the chapel as well, perhaps most notably in the Offices created to celebrate Louis IX after canonisation:

The King of kings, laying out a kingly wedding feast for the king’s son, offers him, after the race in the stadium, the delights of heaven in glorious exchange. [V] In exchange for the kingdom of earthly things, Louis has the celestial kingdom as reward.31

In this responsory, Louis is explicitly linked to the New Testament parable, and both Christ (by analogue) and Louis are offered celestial kingship for their earthly work. The responsory is less melismatic than many examples, perhaps in part so that it can reflect the rhyming text.32 Its fourth-mode melody is restless, beginning with a leap from D to A and cadencing on various pitches before the extended melismas on glorioso commercio (glorious exchange, referring to Louis’s exchange of earthly rule for spiritual delights) close on E, as though finding at last in heaven the rest the saint could not find on earth.

Secular monophony and the growth of courtly song (c. 1100–c. 1300)

To this point we have focused mostly on music for the church, but other forms of Latin song appear as early as the ninth and tenth centuries. Particularly associated with the abbey of Saint-Martial is a group of songs variously called carmen, ritmus and especially versus. While many of these pieces are sacred or even para-liturgical, they also include planctus or laments, such as those on the death of Charlemagne and on the battle of Fontenay (842), satirical songs and so forth. These songs are mostly syllabic and usually strophic in form, with a single melody used for multiple stanzas of text, though the planctus and lai share the paired-verse form of the sequence, where a new melody is used for each pair of verses.33 From the twelfth century Latin songs called conductus appear in Aquitaine and Paris; these are likewise strophic and largely syllabic, though sometimes melismas appear at the beginning and/or the end of the stanza. The conductus can be either monophonic or polyphonic, with all voices moving together homorhythmically.

Peter Abelard wrote six planctus, though their melodies are written only in unheightened neumes that cannot be read, except for this lament of David on the deaths of Saul and Jonathan:

Songs in the language now known as Occitan or Provençal began to appear at the turn of the twelfth century. The relative autonomy of the southern territories and their generally more urban culture may have allowed greater scope for the creation and transmission of vernacular song than was possible in the north. Some have also suggested influence from Arabic songs, by way of Spain, but that cannot be proved. Created by poet-composers known as troubadours, these songs flourished into the thirteenth century, though southern culture was largely cut off by the Albigensian Crusade in the 1220s. Troubadours included both noble amateurs and professionals of lower rank: Guillaume IX, duc d’Aquitaine (d. 1127), and Bernart de Ventadorn (d. c. 1190–1200), who may have been the son of servants of the comte de Ventadorn,35 give an idea of the range possible. Others came from the urban merchant class, and several ended their days in the church; one is known to us only under the name Monge (Monk) de Montaudon. Several women wrote songs, though only one melody, by the comtessa de Dia, survives.

Stylistically, troubadour songs are much like their Latin counterparts: a single melody is used for multiple stanzas of poetry, and mostly syllabic text-setting allows that text to be heard clearly. While laments, crusade songs and satirical songs exist, the most common subject is love, specifically the kind of sacralised devotion known as fin’amors, often translated into English as ‘courtly love’. This is in many ways comparable to the Marian devotion that also flowered in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and it can be difficult sometimes to determine whether the subject of a given song is the Virgin or an earthly lady. While erotic feelings can exist within fin’amors (or within a mystical spiritual context in Marian devotion), they usually cannot be consummated, because the lady is married, of higher social status, or otherwise unavailable. She can, however, be worshipped, and deeds can be done in her name. As Bernart de Ventadorn writes, ‘Fair lady, I ask you nothing/Except that you take me as your servant.’36 On the other hand, the lady’s rejection can be a mortal blow for the poet, as Bernart says elsewhere:

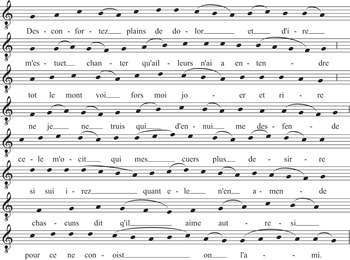

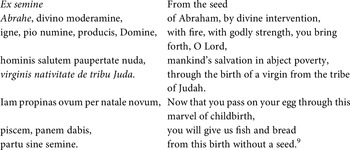

Perhaps more importantly, songs can be sung to and for her, and many examples speak of the narrator’s compulsion to sing. Troubadour songs therefore are in some ways less about love than about singing about love, especially in the high-register examples known as cansos (or grande chanson courtoise).38Gace Brulé (d. after 1213), a minor noble from Champagne and a trouvère, provides one of many examples (see Example 1.2).39

Disconsolate, full of pain and sorrow, I have to sing for I cannot direct my attention elsewhere; I see everyone, except me, play and laugh, nor do I find anyone who can protect me from distress. She whom my heart most desires is killing me, so I am distressed as she offers no redress. Each one says that he loves in this way; one cannot discern a lover by that.

The melody of this song is typical of troubadour and trouvère song in many ways: strophic with a refrain, it sets the text with mostly one note per syllable, sometimes marking the cadences at ends of lines with short melismas. This kind of setting allows the performer to focus on declaiming the text. Lines 1–2 and 3–4 receive paired melodies, which draw the ear to link the lover’s sad state to his separation from those around him. (This reading reflects only the first stanza, which usually seems to be most carefully set to the melody.) The next section rises into the upper range as he sings of how his desire is killing him, but then falls as he realises she will not save him.

Example 1.2 Gace Brulé, ‘Desconfortez’

In the short final stanza or envoi, the poet names himself and refers directly to his song:

This self-referential aspect, foreign to chant and early polyphony, may be reflected in the manuscript transmission of the songs: they often appear in collections organised by author, frequently including author ‘portraits’ and even short ‘biographies’ (vidas). The vidas cannot be trusted for strict documentary veracity, but they demonstrate an interest not only in the songs but in the lives of the individuals who created them, an attitude far removed from the fundamentally anonymous nature of chant and sacred polyphony.

The surviving sources of troubadour song come from the mid-thirteenth century and beyond, considerably later than the main flowering of composition. Some manuscripts come from Occitan areas, but many were copied elsewhere, in northern France, Catalonia and especially Italy. Only four of about forty surviving sources or fragments include musical notation. The notation used, like that for chant, generally gives no information about rhythm, much less other nuances of performance, such as the use of dynamics or instrumental accompaniment. This lack of notational specificity has created difficulties for scholars and modern performers, but it seems to suggest a kind of performative flexibility that could not be written in any system available to thirteenth-century scribes.40 Texts are generally unstable, and where a melody appears in more than one manuscript, there are nearly always variants that show a similar lack of concern for fixity and suggest not only oral transmission but also the possibility that scribes intervened in the copying of melodies as well as texts, creating and fixing problems in transmission and ‘improving’ readings according to their lights.41

While many examples of troubadour song are in the elevated style of the canso, lower-register poetry such as that of the pastourelle also exists, set to popularising melodies reminiscent of dance styles. Such songs were probably performed metrically, whether or not they are so written, and they may well have had some form of improvised instrumental accompaniment. The higher-register songs, on the other hand, may have been performed without accompaniment, facilitating the rhythmic flexibility that allows greater expression of the text.42

From the late twelfth century poet-composers known as trouvères appear in northern lands, working in French dialects. The shift may not be directly attributable to the influence of Eleanor of Aquitaine (c. 1122–1204), as has sometimes been argued, but it is worth noting her extensive family connections to secular song: her grandfather, Guillaume IX, duc d’Aquitaine, was the first documented troubadour, while her descendants included two trouvères, her son Richard, King of England, and Thibaut de Navarre, grandson of Marie de Champagne, one of Eleanor’s daughters by Louis VII and a major literary patron in her own right.43 Paris and the royal court, however, were less important for the development of trouvère song than Picardy and Champagne, and in the thirteenth century Arras became an important centre of trouvère activity among members of the merchant class, notably the poet and composer Adam de la Halle (b. c. 1245–50; d. 1285–8?). Most of the basic formal and stylistic features of trouvère songs are similar to those already outlined for the troubadours, but by the mid-thirteenth century a shift of emphasis may be seen, away from the high-register grant chant courtois and towards less elevated and more popularising styles and genres such as the pastourelle and the jeu-parti.44

Trouvère song survives in written form much more strongly than its southern counterpart. This may be in part because it flourished rather later, so it benefited from the growing book culture of Paris and the Île-de-France during the thirteenth century. It is not surprising, then, that not only more sources exist, but more sources with musical notation, and that therefore far more songs survive with melodies intact. Where Elizabeth Aubrey calculates 195 distinct melodies for 246 troubadour songs, approximately 10 per cent of the surviving poems, surviving in four sources with notation,45Mary O’Neill cites ‘some twenty substantial extant chansonniers’ of trouvère song containing approximately ‘1500 songs [that] survive with their melodies’.46

Ample evidence exists in literature, sermons and other texts for dance music, ceremonial music, popular song and so forth, but few traces of these remain.47 Courtly song and dance were often performed by minstrels or jongleurs, whose activities went beyond music to include storytelling, conversation and other forms of entertainment. Minstrels and heralds also sometimes served diplomatic or messenger roles, since they tended to travel from place to place; in the process, they could facilitate the movement of musical styles and genres. In a song written around 1210 the troubadour Raimon Vidal outlines a fictional journey from Riom at Christmas time to Montferrand (with the Dalfi d’Alvernhe), Provence (and the court of Savoy), Toulouse (where the narrator receives a suit of clothes), Cabarès, Foix (where the count is unfortunately absent) and Castillon, finally arriving at Mataplana in April.48 There is no reason to believe that similar travels were not undertaken by actual musicians.

Music can also be found in dramatic genres, from debate songs and dialogue tropes to more fully developed plays.49 Latin liturgical dramas such as those found in sources from Saint-Martial in Limoges and Saint-Benoit in Fleury, near Orléans, were completely sung, mostly using chant and chant-like styles. The Play of Daniel, one of the best-known examples today, was created by students of the cathedral school in Beauvais in the early thirteenth century for performance in the Christmas season, perhaps in conjunction with Matins on the Feast of the Circumcision (1 January).50 Vernacular religious drama tended to use spoken dialogue along with a wide range of musical styles, from chant to instrumental music. The only French secular drama that survives with a substantial body of music is Adam de la Halle’s Jeu de Robin et de Marion, probably intended to entertain troops from Arras spending Christmas in Italy around 1283. The melodies it contains use the style of popular refrains like those also found inserted into narrative poems, so they may have been borrowed rather than newly composed.

Christopher Page traces a ‘powerful secularising impulse … in many areas of cultural life’ as in other areas of culture during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.51 The ability to write and sing songs becomes an essential attribute of the courtier, a manly art suitable for indoor display in front of women.52 Indeed, this ideal of the noble who can sing and play is common within romance, and this image surely not only reflects lived reality but in turn influenced the training and self-image of young nobles who read and heard such tales. Employing minstrels or jongleurs could also enhance the reputation of a nobleman, because it showed his generosity and ability to entertain his courtiers; those travelling entertainers in turn could carry songs and tales about his prowess to other lands.53

By the thirteenth century clearly secular forms of music were much more likely to be written down and discussed by both courtiers and churchmen than they had ever been. Sacred and secular, however, were frequently intertwined throughout medieval culture: liturgy and politics served each other at the Sainte-Chapelle as at Charlemagne’s court, court functionaries from Alcuin to Machaut were educated in schools tied to the church and rewarded with ecclesiastical positions, and the languages of fin’amors and Marian devotion continually overlapped. Our neat categories do not always fit the medieval reality.

It is easy to believe that the story of French monophony ends at this point, and indeed polyphony has taken over most readers’ attention well before the end of the thirteenth century. Nevertheless, monophony continued to be performed, and it probably dominated the average person’s daily experience well into the early modern era. Monophonic dance music and popular song surely flourished – it simply was not usually written down. Gregorian chant remained the foundational musical experience of choirboys, so it served as the roots, both literally and figuratively, from which polyphony grew. New chant continued to be composed when needed, for instance by Guillaume Du Fay for a new celebration at Cambrai Cathedral in the 1450s. Since the primary tale of music history, however, is the story of compositional innovation in the written tradition, we turn the page towards a polyphonic future.

Notes

I am grateful to William Chester Jordan and Daniel DiCenso for comments that kept me from several inaccuracies in areas outside my area of specialisation. The members of my research group here at Loyola, as usual, forced me to clarify my thoughts. All remaining errors are my own.

1 et al., ‘Gallican chant’, Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online (accessed 22 May 2014).

2 Specialists in this area emphasise the fundamental heterogeneity of Merovingian liturgy; see, for example, the introduction to Missale gothicum, ed. , Corpus Christianorum Series Latina, 159D (Turnhout: Brepols, 2005), 190–3.

3 For example, see , ‘Toledo, Rome and the Legacy of Gaul’, Early Music History, 4 (1984), 49–99.

4 There had already been extensive contact between Rome and Francia by this time. See , ‘Carolingian music’, in (ed.), Carolingian Culture: Emulation and Innovation (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 275–7; and , The Christian West and its Singers: The First Thousand Years (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), especially chapters 8–17.

5 Charlemagne was clearly considered to be an emperor, but apparently he avoided taking that title, perhaps wishing to emphasise that he ruled a new, Christian empire rather than simply taking on the mantle of the Romans. See , The Carolingians: A Family who Forged Europe, trans. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993), 122–3.

6 See , ‘The Carolingian renaissance: education and literary culture’, in (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History, vol. II: c. 700–c. 900 (Cambridge University Press, 2008), 709–57. See also the work of , especially The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751–987 (London and New York: Longman, 1983), and Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

7 , The Carolingians and the Written Word (Cambridge University Press, 1989); and David Ganz, ‘Book production in the Carolingian empire and the spread of Carolingian minuscule’, in McKitterick (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History, vol. II, 786–808.

8 , ‘Emulation and invention in Carolingian art’, in (ed.), Carolingian Culture, 248–73; and Lawrence Nees, ‘Art and architecture’, in McKitterick (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History, vol. II, 809–44.

9 , ‘The making of Carolingian Mass chant books’, in et al. (eds), Quomodo cantabimus canticum? Studies in Honor of Edward H. Roesner (Middleton, WI: American Institute of Musicology, 2008), 37–63.

10 Rankin, ‘Carolingian music’, 281–9.

11 The role of Gregory I is summarised in , Western Plainchant: A Handbook (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 503–13.

12 See Rankin, ‘Carolingian music’, 290–1; and , ‘Some thoughts on music pedagogy in the Carolingian era’, in , and (eds), Music Education in the Middle Ages and Renaissance (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 37–51.

13 On the origins of glossing, see McKitterick, The Frankish Kingdoms, 289.

14 Text ed. and trans. in , ‘Liturgy and sacred history in the twelfth-century tympana at Chartres’, Art Bulletin, 75 (1993), 506.

15 McKitterick, The Frankish Kingdoms, 281.

16 Many of the Saint-Gall manuscripts have now been digitised as part of the Virtual Manuscript Library of Switzerland. See www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en (accessed 22 May 2014).

17 This is the mid-tenth-century manuscript St-Gall, Stiftsbibliothek, MS 484; see , ‘On the dissemination of Quem quaeritis and the Visitatio sepulchri and the chronology of their early sources’, Comparative Drama, 14 (1980), 46–69.

18 , The Musical World of a Medieval Monk: Adémar de Chabannes in Eleventh-Century Aquitaine (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

19 , ‘The cult of Saint Denis and Capetian kingship’, Journal of Medieval History, 1 (1975), 43–69; and , A Tale of Two Monasteries: Westminster and Saint-Denis in the Thirteenth Century (Princeton University Press, 2009).

20 The reference to divine luce comes from the verse of the Vespers responsory Cum sol nocturnas, quoted in , The Service-Books of the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis: Images of Ritual and Music in the Middle Ages (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), 230. The seventh responsory speaks of ‘the angelic companies’, another Pseudo-Dionysian concept. Reference SpiegelIbid., 232.

21 Reference SpiegelIbid., 245–8.

22 Spiegel addresses the creation of the idea of the holy king in ‘The cult of Saint Denis’. On scrofula, see , ‘The King’s evil’, English Historical Review, 95 (1980), 3–27.

23 , The Virgin of Chartres: Making History through Liturgy and the Arts (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010).

24 Example 1.1 is edited from Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS fonds latin 15181, fol. 379v; image accessed from http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8447768b/f766.item (accessed 22 May 2014). The manuscript is the first part of a two-volume early fourteenth-century noted breviary from Notre-Dame of Paris according to the CANTUS database (cantusdatabase.org). Spelling is as given in the manuscript, except that abbreviations have been silently expanded and i/j and u/v have been given their modern forms. Slurs indicate ligatures in the source. This chant is also edited in Fassler, The Virgin of Chartres, 414 (text and translation) and 415 (music).

25 This reading is independent of Fassler’s, which rightly stresses the music’s support of the structural units of the text, along with emphasis on key words. Ibid., 125–6.

26 , Music and Ceremony at Notre Dame of Paris, 500–1550 (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

27 The phrase docere verbo et exemplo is common in Augustinian literature. This paragraph is largely based on , Gothic Song: Victorine Sequences and Augustinian Reform in Twelfth-Century Paris (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

28 , ‘Aurelianis civitas: student unrest in medieval France and a conductus by Philip the Chancellor’, Speculum, 75 (2000), 589–614.

29 , ‘Speculative “musica” and the medieval University of Paris’, Music and Letters, 90 (2009), 177–204.

30 , Visualizing Kingship in the Windows of the Sainte-Chapelle (Turnhout: Brepols, 2002), v.

31 , The Making of Saint Louis: Kingship, Sanctity, and Crusade in the Later Middle Ages (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008), 105, 261.

32 The melody is given as the first responsory for Matins in , ‘Ludovicusdecus regnantium: perspectives on the rhymed office’, Speculum, 53 (1978), 316–17.

33 For the intersections among these three genres, see , Words and Music in the Middle Ages: Song, Narrative, Dance and Drama, 1050–1350 (Cambridge University Press, 1986), 80–2.

34 This melody is from a thirteenth-century English source, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 79, fols 53v–56. Stevens, Words and Music in the Middle Ages, 121–6.

35 Bernart’s origin is based on untrustworthy sources and has been questioned; for a summary of the issue see , The Music of the Troubadours (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 9.

36 From the seventh stanza of ‘Non es meravelha s’eu chan’: , and (eds and trans.), Songs of the Troubadours and Trouvères: An Anthology of Poems and Melodies (New York: Garland, 1998), 64–5.

37 From the seventh stanza of ‘Can vei la lauzeta mover’: Rosenberg, Switten and Le Vot (eds and trans.), Songs of the Troubadours and Trouvères, 68–9.

38 On the self-referentiality of songs, see for instance , Courtly Love Songs of Medieval France: Transmission and Style in the Trouvère Repertoire (Oxford University Press, 2006), 56–62.

39 Example 2.1 is edited from Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS fonds français 845, fol. 38r; image accessed from http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000955r/f85.image.r=845.langEN (accessed 22 May 2014). Spelling is as given in the manuscript, except that abbreviations have been silently expanded, apostrophes are given when appropriate, and i/j and u/v have been given their modern forms. Slurs indicate ligatures in the source. See (ed.), Songs of the Trouvères (Newton Abbot: Antico Edition, 1995), xv (text and translation) and 13 (music).

40 The various theories are summarised in Aubrey, The Music of the Troubadours, 240–54. has made the fullest study of the question of instrumental participation in Voices and Instruments of the Middle Ages: Instrumental Practice and Songs in France, 1100–1300 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986).

41 See Aubrey, The Music of the Troubadours, 51–65; and O’Neill, Courtly Love Songs, 53–92.

42 Aubrey discusses the genres of troubadour song in chapter 4 of The Music of the Troubadours, 80–131.

43 The best introduction to Eleanor is , Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of France, Queen of England (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009).

44 O’Neill, Courtly Love Songs, especially chapter 5, 132–73. In chapter 6, 174–205, however, O’Neill argues that to some degree Adam de la Halle attempts to reverse this movement, returning to an older aesthetic.

45 Aubrey, The Music of the Troubadours, 49.

46 O’Neill, Courtly Love Songs, 13, 2.

47 has mined this area particularly well in The Owl and the Nightingale: Musical Life and Ideas in France, 1100–1300 (London: Dent, 1989).

48 This song is discussed in , ‘Court and city in France, 1100–1300’, in (ed.), Antiquity and the Middle Ages: From Ancient Greece to the 15th Century (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1990), 209–12, and in Page, The Owl and the Nightingale, 42–60.

49 Most of this paragraph draws from et al., ‘Medieval drama’, Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online (accessed 22 May 2014). See also , ‘Liturgical drama and community discourse’, in and (eds), The Liturgy of the Medieval Church (Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2001), 619–44.

50 , ‘The staging of The Play of Daniel in the twelfth century’, in (ed.), The Play of Daniel: Critical Essays (Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1996), 15–17.

51 Page, The Owl and the Nightingale, 3.

52 Page, Voices and Instruments, 3–8.

53 Page, The Owl and the Nightingale, 42–4.

2 Cathedral and court: music under the late Capetian and Valois kings, to Louis XI

The period extending from the end of the twelfth century to the middle of the fifteenth marks the highpoint of French influence on European music. French composers contributed brilliantly to contemporary genres after 1450, but it was in the earlier period that northern French composers steered a path forward in an environment that paradoxically admitted both constant renewal – a normal participatory music-making – and an aesthetic of authority and fixity, the legacy of Carolingian liturgical chant. The coordination of active musical creativity with constructivist techniques of polyphonic elaboration in rational synthesis (is that what ‘French’ is?) created the fundamental profile of what we recognise as ‘Western’ music in the first place.

The Notre-Dame school

In the years from 1163 to 1250, a new cathedral of Notre-Dame was built on the central island in Paris. Remarkably, the construction paralleled the development of a new polyphonic music, the first to be regulated by metrical rhythm. Much of what we know about the so-called Notre-Dame school of composers comes from a music treatise penned perhaps in the 1270s by ‘Anonymous IV’, an unnamed English student who had once studied in Paris.1 He records the achievements of two composers, Leonin, organista, author of a great book (magnus liber) of organa, and Perotin, discantor, who made ‘better clausulae’ than Leonin.

Extant musical manuscripts confirm that the first great achievement of the Notre-Dame composers lay in a collection of two-part organa (settings of the Gregorian cantus firmus plus one added voice, the duplum). For the most part, three plainchant genres were subject to elaboration: the Gradual and Alleluia from the Mass, and the Great Responsory from the Divine Office. As monophony, these are ‘responsorial’ chants, alternating virtuosic solo passages with unison choral passages. In the new organa, segments originally delivered by the soloist provide the cantus firmus, as another soloist sings new music above. Segments originally delivered by the choir remained the domain of the choir.

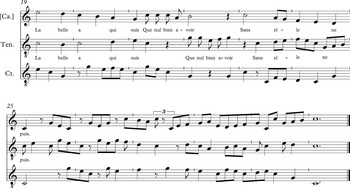

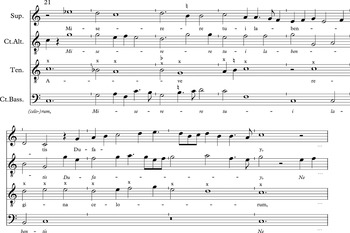

Theorists distinguished two styles of polyphony, organum purum and discant. Broadly speaking, the two styles respond to two patterns of text declamation in the original plainchant. Segments of syllabic text were set in organum purum, sustaining the individual pitches of the cantus firmus in the long tones of the tenor, above which the added voice would rhapsodise freely. Melismatic segments were set in faster-moving discant, one or two notes in counterpoint against the cantus firmus. At first probably unmeasured, by around 1200 discant segments exhibited metrical rhythm based on a regular pulse. In these isolated discant segments of Leonin’s two-part organa, a fateful step towards a fundamental prerequisite of Western music occurs: the ability to control polyphonic voices in rhythm. Examples 2.1a and b illustrate excerpts from a Notre-Dame organum purum and discant, extracted from the organum Alleluia Nativitas for the Nativity of the Virgin.2

Example 2.1a Alleluia Nativitas, organum purum (beginning) by Leonin(?)

Example 2.1b Alleluia Nativitas, discant on ‘Ex semine’ (beginning) by Leonin(?)

Craig Wright has shown that Leonin may be identified with a canon at the cathedral of Notre-Dame who lived from around 1135 to after 1201.3Anonymous IV credits Leonin as the best organista, a specialist in organum purum. Does he mean a skilled singer capable of negotiating a new work as a performance unfolds or a figure closer to what we would label a ‘composer’, someone who literally puts together a work, which is then notated and transmitted as an entity? The question is currently debated.4

Anonymous IV has much more to say about Perotin (d. c. 1238?). First, his superior skill as discantor produced better clausulae (phrases), discant segments that can replace corresponding segments in Leonin’s settings. Such ‘substitute clausulae’ utilise the same snippet of chant, but exhibit increasing rhythmic sophistication. Our most complete source of music of the Notre-Dame school, the Florence Codex, finished in 1248 for the dedication of Louis IX’s Sainte-Chapelle, has a fascicle of no fewer than 462 of these two-voice substitute discant segments.5Example 2.1c illustrates a modernised reworking of Example 2.1b, presumably by Perotin.6

Example 2.1c Alleluia Nativitas, discant on ‘Ex semine’ (beginning) by Perotin(?)

Unlike most chansonniers of the troubadours and trouvères, manuscripts of polyphony in this period lack composer attributions, but thanks to Anonymous IV seven specific works preserved in the extant manuscripts can be attributed to Perotin. Two highly sophisticated four-part works can even be dated: the Viderunt (Gradual for the third Christmas Mass) of 1198 and the Sederunt (Gradual for St Stephen’s Day) of 1199. Three of the attributions involve a second genre cultivated by the Notre-Dame school, the conductus, a freely composed setting of strophic Latin poetry in one to three voices. Several conductus texts can be attributed to Philip the Chancellor (b. c. 1160–70; d. 1236), a direct contemporary of Perotin, and in fact Beata viscera, a monophonic conductus, is a collaboration between them.

The early motet

Notre-Dame organa and conductus soon receded from compositional history, but a third genre, the motet, became the crucible for all advances in polyphony for at least the next 125 years. Unfortunately, our informant Anonymous IV is completely silent on its origins. The usual musicological narrative links the earliest motets to the active development of discant in the early thirteenth century: the initial step that created the motet was the application of a poetic text to the most modern rhythmised music of the time, pre-existing discant clausulae.

Consider again the Alleluia for the Nativity of the Virgin (Example 2.1a). Our earliest source, W1 (c. 1230), transmits a rudimentary discant setting the words ex semine (Example 2.1b), modernised in the Florence Codex (Example 2.1c).7 Indeed this modernised clausula saw double duty in a work that Anonymous IV attributed to Perotin, the three-voice Alleluia Nativitas, with the addition of a triplum voice. Both as a two- and three-voice form we can count this segment one of the ‘better clausulae’ composed by Perotin. The text, probably by Philip the Chancellor, fits Perotin’s music and makes the segment into a motet (Example 2.2).8

Example 2.2 Perotin(?) and Philip the Chancellor(?), motet Ex semine Abrahe/Ex semine

In explicating the mysteries of the birth of the Virgin Mary, Philip framed his text with the words of the cantus firmus, and skilfully incorporated bits of text from elsewhere in the Alleluia verse (these connections are set in italic type). Note that the poetic impulse behind the motet has a different emphasis from that of a purely occasional conductus text. Because of its ultimate origins in liturgical organum, the motet’s text glosses the original liturgical context of the parent organum; indeed, it is possible that early motets, like tropes, were used liturgically.

Besides responding to the liturgical moment, a poet faced a special challenge, for it happens that the discant clausula was not a kind of music suited to traditional poetic forms, which build strophes out of regular patterns of rhyme and syllable count. The melody of the cantus firmus is usually broken into groups of two or three notes, separated by rests and set in rhythmic ostinato, as in Example 2.2. Phrases in the duplum voice play off the recurring patterns, now bridging across rests, now pausing with the tenor. The text given above divides lines according to their distribution across each statement of the five-note ostinato. One might also print the text observing rhymes, which produces a flood of irregular short lines: neither option produces an orthodox piece of poetry, because musical exigencies generated ad hoc poetic designs.

Thomas Payne argues that the creation of the motet was a product of collaboration between Perotin and Philip the Chancellor: its conceptual beginnings lie in surviving organum prosulas (texting just the duplum of the four-voice Viderunt and Sederunt) whose texts can be ascribed to Philip.10 One might push Payne’s thesis a step further and seek the earliest notation of rhythm itself in the application of text, for this simple means was available well before modal rhythmic notation, first attested in W1.11 The motet texts themselves suggest musical rhythm, a sing-song that results from the alternation of strong and weak word accents organised into lines of specific syllable count, and from the chiming of the frequent rhymes. The texted form of the duplum voice of Perotin’s Viderunt is thus a surviving remnant of compositional process: each phrase of text preserves the rhythms of a phrase of music right from the start – a true collaboration of a skilled musician and a skilled poet. The other two voices, the triplum and quadruplum, did not require separate notation, for they operated closely in tandem with the texted duplum through voice exchange, and could apply the same words. Guided by Philip’s text, performers learned Perotin’s music. Such a scenario allows us to imagine the construction of Perotin’s organum as a ‘work’, even before an efficient notation was devised to fix it onto parchment.

The motet in the mid-thirteenth century

Motets of the early and middle years of the thirteenth century are protean works, products of collective and collaborative creative efforts. The ‘case history’ of motets based on Perotin’s Ex semineclausula in its two forms, a two-voice discant updating Leonin’s Alleluia Nativitas and a three-voice discant taking its proper place in Perotin’s new three-voice Alleluia Nativitas, can serve as a simple example. We have seen that Philip’s poem Ex semine Abrahe was key to the initial fixing of the rhythms of the new work, and thus motet and clausula were interlinked from the beginning. Once the music was set, it was available for further use. For example, the three-voice version appears with a new text for the triplum, again alluding to a liturgical context by borrowing words from the parent Alleluia.12

Crucial to the explosive development of the motet was its quick acceptance of vernacular French texts. Two use Perotin’s discant as their musical source: Se j’ai amé/Ex semine and Hier main trespensis/Ex semine.13 Most often, new vernacular texts are in no way tied to the liturgical context of the tenor cantus firmus, but the tenor text may relate emblematically or ironically to the texts of the upper voices. In general, the direction of development is towards more phrase overlap between the voices than we observe in Example 2.2, a musical characteristic confirmed by poly-textuality (a separate poem for each upper voice) and different verse structures in each text. Often new music as well as new text can replace an existing voice.

Once the motet entered the world of vernacular literature, it began to participate in a highly ramified and interconnected cultural endeavour. Its polyphonic and poly-textual nature made it the ideal form for the synchronous juxtaposition of diverse materials (the French motet can draw upon the wide variety of contemporary trouvère genres, such as the gran chant, chanson de mal mariée, chanson de toile, pastourelle and rondet, as well as the ubiquitous refrain), which in turn stand in dialogue with the sacred associations of the tenor. For example, one could juxtapose a male and a female voice, or different voices that represent different sides of a single persona, or place courtly love conceits side by side with Marian adoration and with earthy pastoral high jinks.14

The French motet epitomises in miniature the most characteristic large-scale literary production of this period: the narrative with lyrical insertions (‘hybrid narrative’). Indeed, the first hybrid narrative, Jean Renart’s Roman de la rose (c. 1210?), which includes forty-six lyrics of diverse genres cited in the course of the narrative, appeared about the same time as the first French motets. The most familiar of the hybrid narratives is Le jeu de Robin et de Marion (c. 1283, seventeen refrains and chansons), a pastoral drama by Adam de la Halle (b. c. 1245–50; d. 1285–8?), working at a French outpost, the Angevin court at Naples. Integration and unity were not artistically desirable traits in this aesthetic: its essence lies in the unexpected and ingenious juxtaposition of dissimilar materials. Intertextual citations, cross-references within and between genres (especially prominent in French motets that cite refrains), can be bewilderingly complex.15

For us today the most elusive aspect of the mid-thirteenth-century motet is its social context.16 Hybrid narratives, such as Renart’s Roman de la rose, often present credible social contexts for the lyrical insertions. No one in a hybrid narrative stands up at a banquet to sing a polyphonic motet, however. The best information we have is the statement of the Norman theorist Johannes Grocheio, writing in Paris around 1300: ‘This kind of music should not be set before a lay public because they are not alert to its refinement nor are they delighted by hearing it, but [it should only be performed] before the clergy and those who look for the refinements of skills.’17 Yet the clerics, in creating works for their peers, proved themselves thoroughly conversant with the vernacular courtly-popular literary culture of the day. In the French motet, the elite clerical culture transforms ‘lewd entertainment’ into ‘spiritual performance’.18

The late thirteenth-century motet

By the end of the thirteenth century the motet had assumed a level of complexity that excluded the casual contribution of a new poem or the revision of a single musical voice, favouring instead skilled individual creators of unique works. The new diversity meant that the mensural system needed to be regularised. For a time, the old ostinato patterns of the Notre-Dame tenors held sway along with the Notre-Dame cantus firmi (cf. Example 2.2). But when a refrain with pre-existing music was incorporated into the upper voices, it meant that the tenor required more flexibility so that the tenor pitches could be adjusted as needed to fit with the refrain, and hence there was a growing urgency for the exact specification of rhythmic values. The new system of mensural notation drew upon the notational figures of Gregorian chant, utilising three traditional shapes, but now assigning them the durations of long (![]() ), breve (

), breve (![]() ) and semibreve (

) and semibreve (![]() ). A definitive and rational mensural notation was codified by the theorist Franco of Cologne around 1280.19

). A definitive and rational mensural notation was codified by the theorist Franco of Cologne around 1280.19

The late thirteenth century was a period of great experimentation. For example, the motet Mout me fu grief/Robin m’aime/Portare incorporates Marion’s well-known opening song from Adam de la Halle’s pastoral drama Jeu de Robin et de Marion as its duplum.

Maintaining the song’s original rhythms, it is the duplum’s phrase structure and irregular repeating patterns (ABaabAB, rondeau-like) that shape the overall structure of the motet, not the tenor. Yet the composer was also able to incorporate a second bit of pre-existing music, a Gregorian cantus firmus carried by the tenor.20 This was but one experiment among many.

Beginning with collective and collaborative creative efforts, the motet underwent enormous expansion in the thirteenth-century creative nexus, more and more delighting in connections that touched every sort of literary and musical creation until the emergence at the end of the century of individual works. The late thirteenth-century motet exhibits a striking variety of organisational techniques, each aiming at a new flexibility in handling long-range structural articulation that had not been possible with the short ostinatos that structured the earliest motets. In the early fourteenth century, by dint of powerful intellectual application, this quest for variety converged in a new approach, which created a concentrated and reflexive form that would overturn the old aesthetic of rupture.

The ars nova and the Roman de Fauvel

Until this point, musical rhythm had been largely based on triple metre (‘perfect time’). The potentialities of duple metre (‘imperfect time’) were first rationally worked out in the early fourteenth century. The new notation, epitomising a dawning new age of music, is a product of the ars nova, a term attested by four witnesses of around 1325. While two music-theory treatises celebrate the new developments, a third treatise and a papal document deride them. Regardless of opinion, the ars nova brought an enormous expansion to the possibilities of organising and notating rhythm, best expressed by the music theorist Johannis des Muris: ‘whatever can be sung can be written down’.21

The most important musical monument of the early ars nova is a version of theRoman de Fauvel found in only one manuscript, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, fr. 146.22 It expands two earlier allegorical hybrid narratives (of 1310 and 1314) critiquing the government of King Philip IV and admonishing his heirs Louis X and Philip V. The revised Fauvel of fr. 146 (c. 1318) incorporates seventy-two miniatures as well as 169 musical insertions, including items of Gregorian chant, newly composed pseudo-Gregorian chant, conductus (some with newly composed music), motets, French refrains, ars nova chansons, lais and satirical or obscene sottes chansons.

Perhaps compiled with the patronage of a prince in the king’s council, the Roman de Fauvel gives satiric artistic expression to the discontent felt by officials of the royal chancery over a government in crisis. It is a topsy-turvy world ruled by Fauvel, a corrupt half-man-half-horse creature; here, the sort of grotesqueries formerly relegated to the margins of a manuscript have been transformed into the principal players, front and centre.23

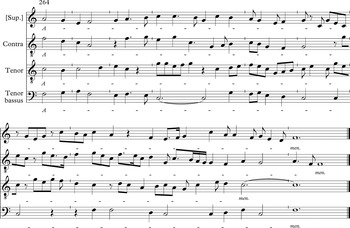

Though we lack certain proof, for no music is attributed in the manuscript, it appears likely that the young Philippe de Vitry (1291–1361) was the principal composer of new music for the Fauvel project. Arguably the most progressive musical work of the entire manuscript is his ingenious motet Garrit Gallus/In nova fert/Neuma.24 The quotation of the opening of Ovid’s Metamorphoses at the start of the duplum voice – ‘In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas’ (‘I am moved to speak of forms changed into new bodies’) – epitomises the work’s message, an expression of the political transformations that threatened society. In this motet Vitry brilliantly succeeds in transferring the essence of this message – the abstract notion of transformation – into the very core of the musical structure. He accomplishes this first through the absolutely unprecedented rhythmic design of the tenor, which transforms itself from perfect to imperfect time and back again, employing red ink for the imperfect notes and rests, an ars nova innovation (Example 2.3). (In the original notation, the note shapes form a palindrome.)

Example 2.3 Periodic structure in Philippe de Vitry(?), motet Garrit gallus/In nova fert/[Tenor]

Further, in composing out the poetic idea, Vitry drew on a new aesthetic of integration. We have seen that the Roman de Fauvel as a whole incorporates both old and new works among the musical insertions. Sometimes they stand in loose juxtaposition with the narrative, an extreme expression of thirteenth-century discontinuity, while at other times they form coherent episodes. In a performative sense, they are ‘staged’.25 The same can be said of the motet. Since its inception, the form had exhibited discontinuities: a stratification of voices and especially poly-textuality, which before had allowed for a refreshing independence in phrase lengths between the different voices. In this motet, Vitry ‘stages’ these discontinuities by coordinating the phrase lengths of both upper voices with the tenor. In Example 2.3, the rests above the tenor talea indicate the placement of rests in the duplum and triplum (there are no other rests in these voices).26 Except at the very beginning and at the very end, rests always recur at the beginning and end of the tenor segment transformed into imperfect time. By means of this ‘periodicity’, the whole musical structure is subject to transformation, not just the tenor. The poetic message is integrated into the deepest structure of the work, permeating it.

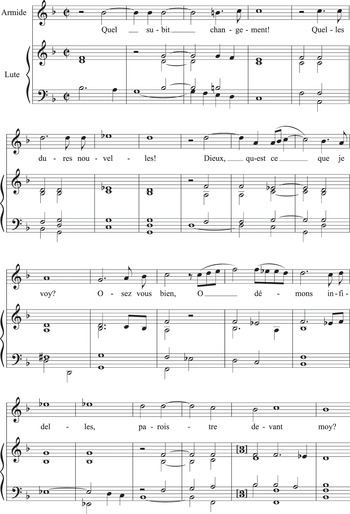

The polyphonic chanson

The motet was not the only genre revolutionised by the Roman de Fauvel. The Roman de Fauvel also turned vernacular song on its head. Although it took longer to accomplish the full measure of change in the chanson than it did in the motet, eventually the transformation set in motion in the early fourteenth century came to fruition with polyphonic chansons in ‘fixed forms’ that saw their first maturity in the 1340s in the works of Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300–1377) and his contemporaries. Ultimately built on thirteenth-century dance genres, the three fixed forms – ballade, rondeau and virelai – each incorporate the text and music of refrain and stanza in a different pattern.

The emergence of the Machaut-style chanson involved at least three steps.27 First, the projection of rhythm through syllabic declamation at times dissolves in melismatic passages. In the monophonic fixed-form chansons inserted into the Roman de Fauvel, melismas can sever the direct tie to the sung dance, for now syllabic declamation no longer animates the rhythm; further, the melismas effectively slow the text delivery, or relegate it to isolated active patches. At the same time, melismatic melody imbues the refrain form with an unaccustomed highbrow artifice.

Another stage of development, which we can follow in early fourteenth-century hybrid narratives, lends the ballade a certain dignity stemming from long poetic lines, as had been characteristic of the most precious chansons of the trouvères. Finally, the chanson takes on polyphony, a new disjunctive polyphony rare in the chanson before Machaut. Earlier essays in the polyphonic setting of refrain lyrics, such as those of Adam de la Halle, exhibit an integrated projection of the poetic structure, too uniform to command sustained compositional interest.28 Rendered fully independent by the new notation, now the tenor operates freely, creating discant-based counterpoint with the texted cantus voice. Other parameters that may be in play, and which may be staged with disjunction or with integration depending on the needs of the moment, include text projection (syllabic or melismatic, normal or syncopated declamation patterns), tonal centres (degree of tonal unity, use of directed progressions) and sonorities.

As with the motet, our role as attentive listeners in coming to terms with this aesthetic is to discover the poetic image that the work reifies. Examples are legion in Machaut: the harsh leaps and unexpected turns, as well as the wholly unorthodox cadence formation of the ballade Honte, paour, represent the contortions a faithful lover must endure; the fragrance of the rose in the rondeau Rose, lis, which is sensed in sonorous descending progressions, now with E♮, now with E♭; the ‘sweet’ opening sonority of the rondeau Douce, viare, which concludes on a soft B♭; one might continue such examples at will.29

Guillaume de Machaut and the Remede de Fortune

The figure of Guillaume de Machaut looms large in any discussion of fourteenth-century music. Equally distinguished as a poet and musician, he was unusual for the care he took in the preservation of well-organised manuscript collections of his works.30

Machaut’s early works were written in the service of John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia (r. 1311–46), son of an emperor and father of another emperor, an itinerant king active in political affairs throughout Europe. A favourable marriage sealed an alliance with King Philip VI of France: in 1332, John’s daughter Bonne married John, Duke of Normandy (the future King John II the Good, r. 1350–64). Bonne spent most of her time at Vincennes, the royal manor just east of Paris. It was here that most of the royal children were born and raised, including Charles (the future King Charles V, r. 1364–80) and his siblings, many of them patrons of music of the next generation.

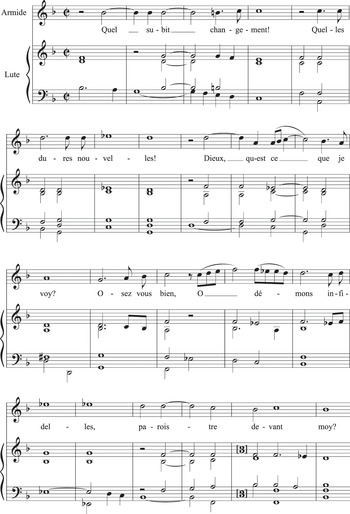

Although full documentation does not survive, it appears likely that Machaut served Bonne at Vincennes at least from around 1340 until she succumbed to the Black Death in 1349. It was at her court that Machaut produced the hybrid narrative Remede de Fortune, a didactic treatise on poetic forms couched in a love story that waxes and seems to wane (one rotation of Fortune’s wheel?).31 The seven interlarded model genres, all supplied with music, include a lai, complainte, chanson royale, duplex ballade, ballade, virelai and rondeau, that is, the three fixed forms (with two forms of ballade) as well as the lyric lai (itself newly ‘fixed’). All of the fixed-form chansons are radically new, to the point that a thirteenth-century courtier would scarcely recognise them as music. Dame de qui toute ma joie vient, the second of the two ballades, is typical of the new style, now holding back and lingering on a syllable, now pushing rambunctiously ahead, always playfully unpredictable and yet affording a satisfying whole (Example 2.4).32

Example 2.4 Guillaume de Machaut, ballade Dame de qui toute ma joie vient, beginning

In the Remede de Fortune Machaut created his own universe, a self-contained world of allusion and intertextual complexity. While he does cite from past authorities such as Adam de la Halle, more frequently he cites himself.33 Like the complete works themselves, it is a world ruled by Machaut, the professional author.

The motet after the Roman de Fauvel

Philippe de Vitry had a particular expressive purpose in mind in composing the motet Garrit/In nova fert/Neuma. In realising that purpose, he hit upon the new concept of periodicity, a systematic coordination of long-range phrase articulation in all voices. Once such a powerful organisational technique was discovered, it soon transformed the motet. In so far as we can tell, all subsequent motets of Vitry, and most of the twenty-three motets of Machaut, are stamped with periodicity, always in the service of a particular poetic image.

As the century progressed, further developments continued to serve a poetic focus. For example, many ars nova motets have two sections, with an additional statement or more of the color (melody of the cantus firmus) in a different rhythmicisation, usually in diminution by one-half. The second section frequently incorporates hocket, the ‘hiccup’ effect of an isolated note in one part emphasised by a rest in the other part, a striking texture that enhances articulation of periodicity in the diminished taleae, thus making relationships clear that had been obscure in the section of long rhythmic values. An early example, Vitry’s O canenda vulgo/Rex quem metrorum/Rex regum (1330s?), leaves the diminished section without text. Yet the unusual texture is justified by a poetic image, announced in the final lines of the duplum, which speak of ‘[the king] whose virtues, mores, race, and the deeds of his son I cannot write; may they be written above the heavens’.34 What more fitting response to follow than pure music, an evocation of the music of the spheres?

After around 1360, motets might appear in three or four sections, with proportional reduction of tenor rhythms, as in Ida capillorum/Portio nature/[Ante tronum], in four sections in the proportions 6:4:3:2.35 Further, the periodicity of the upper voices often extends itself well beyond rests (as in Example 2.3), even to ‘isorhythm’ throughout each talea, in which each iteration is absolutely identical, as regards rhythm, from one talea to the next.36

Isorhythm in this literal sense has often been regarded as a desirable, even inevitable, consequence of periodicity. Paradoxically, however, isorhythm is a symptom of the breakdown of the founding principles of the ars nova motet, for it tends towards disintegration – strophic projection – instead of the integration and accumulation of poetic and musical expression that had been the ideal of the motet since Philippe de Vitry. More and more the motet tends to represent a certain generic model, a series of sections, each culminating in imposing washes of hocket sonorities. The gain was a form of polyphony impressive for public display, since a motet effectively cast in movements, with regular pockets of sublime sonorities, could be appreciated for an overall effect, as an assertion of power. This, along with easy adaptability to dedicatory or celebratory Latin texts in a variety of forms, made the motet useful in state functions in grand architectural settings.37 Later examples of grand political motets include works by Ciconia (a native of Liège) as well as many by Guillaume Du Fay.

Towards a new synthesis

The years from 1360 to 1450 saw palpable increases both in the functions assigned to polyphony and in the diffusion of works. In terms of French music, the period begins with the consolidation of the motet and polyphonic chanson within the French orbit, and the first applications of compositional techniques learned in those genres to sacred art music. It ends with the cultivation over a wide geographical area of a broadened spectrum of forms, for use in a variety of sacred and political contexts, in which the French input, decisive at the beginning, was tempered and merged with streams from the Low Countries, Italy and England in new syntheses, which eventually consolidated into the pan-European ‘international’ style that we associate with the Josquin generation of the late fifteenth century.38

Despite enormous social instability, a number of historical developments contributed to an environment in which musicians and music circulated freely, leading to the diffusion of the advanced French polyphonic style beyond Francophone limits and allowing cross-pollination with indigenous elements. Among these factors were (1) a weakened and unstable central French government under Charles VI and the increased influence of outlying courts; (2) the cultivation and development of sophisticated art polyphony at the courts of the pope and cardinals in Avignon, with a new centre opening in Rome as a consequence of the Great Schism; (3) the international diplomatic missions, with full musical retinues, that gathered at the early fifteenth-century church councils designed to lift the Schism; and (4) an increase in private endowments for polyphony in side chapels of churches, giving rise to service works in sets and cycles. It would be a long and uneven process to establish artistic polyphony at court and church; indeed, the process was far from finished at the end of the period covered in this chapter.

France under Charles VI and the Valois princes