1. Introduction

Being involved in “virtual world games” (Kaplan & Haenlein, Reference Kaplan and Haenlein2010), as a form of social media, has become a part of people’s daily lives around the globe (Yee, Reference Yee2006). Kaplan and Haenlein (Reference Kaplan and Haenlein2010: 61) defined “social media” broadly as “a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation and exchange of User Generated Content.” They also distinguished six types of social media: “collaborative projects,” “blogs,” “content communities,” “social networking sites,” “virtual game worlds,” and “virtual social worlds.” They positioned virtual game worlds (e.g. World of Warcraft [WoW]) and virtual social worlds (e.g. Second Life), among other types of social media, at the highest level concerning “social presence” and “media richness.” They defined social presence as “the acoustic, visual, and physical contact that can be achieved … between two communication partners” and media richness as “the amount of information they allow to be transmitted in a given time interval” (Kaplan & Haenlein, Reference Kaplan and Haenlein2010: 61), asserting that virtual game and social worlds “try to replicate all dimensions of face-to-face interactions in a virtual environment” (Kaplan & Haenlein, Reference Kaplan and Haenlein2010: 62). Virtual game worlds, known as massively multiplayer online games (MMOGs), provide highly interactive two- or three-dimensional persistent virtual worlds within which thousands of players can interact, collaborate, and compete simultaneously. They provide gamers with “access to theme-based virtual worlds, real time communication through text chat, opportunities for role-play, guild membership, status advancement, problem solving, and content creation” (Peterson, Reference *Peterson2011: 57). MMOGs provide second language (L2) learners with access to a vast number of native or more competent interlocutors of the target language (TL), who will have real-life interactions with the learner for a genuine purpose. Due to their design, massively multiplayer adventure/role-playing games afford more player–player and player–computer interactions and their contents include more narratives and language use compared to other game genres (Reinhardt & Sykes, Reference Reinhardt and Sykes2012).

Due to their characteristics, commercially developed off-the-shelf (COTS) or “vernacular” (Reinhardt & Sykes, Reference Reinhardt and Sykes2012) MMOGs have increasingly been considered as promising venues for L2 learning and socialization (Peterson, Reference Peterson2010a; Thorne, Black & Sykes, Reference Thorne, Black and Sykes2009). The notion of L2 learning in the context of MMOGs is well grounded in the definition of computer-assisted language learning (CALL) as “any process in which a learner uses a computer and, as a result, improves his or her language” (Beatty, Reference Beatty2010: 7). Aligned with Beatty’s definition of CALL is the concept of “naturalistic CALL,” which refers to “students’ pursuit of some leisure interest through a second or foreign language in digital environments in informal learning contexts, rather than for the explicit purpose of learning the language” (Chik, Reference Chik2013: 835–836). It opposes the concept of “tutorial CALL” that “refers to the implementation of computer programs (disk, CD-ROM, web-based, etc.) that include an identifiable teaching presence specifically for improving some aspect of language proficiency” (Hubbard & Bradin Siskin, Reference Hubbard and Bradin Siskin2004: 457). Naturalistic CALL underlines the opportunities social media in general and COTS MMOGs in particular can afford for “informal education,” defined by Coombs and Ahmed (Reference Coombs and Ahmed1974: 8) as “the lifelong process by which every person acquires and accumulates knowledge, skills, attitudes and insights from daily experiences and exposure to the environment—at home, at work, at play.” In the same vein, the rationale for incorporating recreational MMOGs in L2 learning and pedagogy can be provided by Lave and Wenger’s (Reference Lave and Wenger1991) situated learning theory (or legitimate peripheral participation model), which suggests that learning takes place in its non-educational form as one is involved in performing meaningful tasks situated in an authentic sociocultural context. According to this argument, “learning is situated; learning is social; and knowledge is located in communities of practice” (Brouwer & Wagner, Reference Brouwer and Wagner2004: 33).

According to Statista (https://www.statista.com), as of July 2014, there were an estimated 23.4 million active monthly MMOG subscribers worldwide. Only one game – WoW – had around 10 million global subscribers in the fourth quarter of 2014. Studies (e.g. Steinkuehler, Reference Steinkuehler2004; Yee, Reference Yee2006) found that massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) are popular across different genders, age groups, and ethnicities. A survey of 30,000 MMORPG players between 2000 and 2003 revealed that “Not only do MMORPGs appeal to a broad age range (Mage=26.57, range=11–68), but the appeal is strong (on average 22 hours of usage per week) across users of all ages” (Yee, Reference Yee2006: 309). These figures indicate the emergence of a new form of online social setting that holds promise for second language acquisition (SLA). Getting immersed in such multilingual and multicultural social settings – like in any other real-life situations – can involve the development of behavioral, social, cultural, and linguistic skills. According to Thorne (Reference *Thorne2008: 308), “What students do online and outside of school involves extended periods of language socialization, adaptation, and collective transformation that result in highly complex, modality and interlocutor specific language practices.” Finding out if, how, and to what extent playing COTS MMOGs contributes to the developmental process of L2 learning and socialization can enhance our understanding of SLA as a naturally occurring phenomenon in non-educational, real-life situations. This valuable insight can, in turn, transform our L2 teaching practice by expanding its borders beyond the boundaries of educational settings. As Thorne (Reference *Thorne2008: 322) speculated, “For the growing number of individuals participating in MMOG environments, the international, multilingual, and task-based qualities of these social spaces, where language use is literally social action, may one day make them de rigueur sites for language learning.”

As “unorthodox language-learning tools” (Rankin, Gold & Gooch, Reference *Rankin, Gold and Gooch2006), MMOGs have attracted the attention of SLA scholars (e.g. Cornillie, Thorne & Desmet, Reference Cornillie, Thorne and Desmet2012; Peterson, Reference Peterson2010a, Reference Peterson2010b, Reference *Peterson2011, Reference *Peterson2012a, Reference *Peterson2012b; Sundqvist & Sylvén, Reference *Sundqvist and Sylvén2014; Sykes & Reinhardt, Reference Sykes and Reinhardt2013), who have investigated MMOGs’ potential for L2 improvement. Although so much more of L2 development has yet to be explored in the context of MMOGs, findings have been promising so far. However, notwithstanding various findings concerning COTS MMOGs’ L2 learning affordances, the literature lacks an integrated conception that can describe (a) which aspects of L2 learning have been researched in MMOG contexts, (b) which approaches and methodologies have been adopted to investigate these aspects, and (c) what the findings suggest concerning the interrelationships among salient features underlying L2 learning processes within and beyond the MMOG context. Accordingly, the current study was conducted as a scoping review (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) of prior empirical studies to discover how this broad topic has been approached in the literature and what the findings suggest in relation to the wider framework of L2 learning processes. This type of review aims to “map rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available” (Mays, Roberts & Popay, Reference Mays, Roberts and Popay2001: 194).

2. Previous reviews of computer games

Several scholars (e.g. Chiu, Kao & Reynolds, Reference Chiu, Kao and Reynolds2012; Connolly, Boyle, MacArthur, Hainey & Boyle, Reference Connolly, Boyle, MacArthur, Hainey and Boyle2012; Cornillie et al., Reference Cornillie, Thorne and Desmet2012; Ke, Reference Ke2009; Peterson, Reference Peterson2010b) have reviewed computer games and their contribution to the development of different sets of skills and knowledge. For example, Peterson (Reference Peterson2010b) examined the key findings from seven studies (published between 2001 and 2008) that focused on digital games and simulations in language education. He categorized the studies according to whether they analyzed “web-based simulated virtual worlds,” “3D web-based simulated virtual worlds,” “stand-alone commercial simulation games,” “massively multiplayer online role-playing games” (MMORPGs), and/or “game- and simulation-based training systems.” For the MMORPG category, Peterson reviewed Thorne’s (Reference *Thorne2008) study, which investigated language-learning opportunities in WoW, and found that participation in MMORPGs affords L2 learners with extensive exposure to the TL in a motivating and learner-centered environment – a setting that encourages negotiation of meaning, collaborative dialog, and interpersonal relationships.

Connolly et al. (Reference Connolly, Boyle, MacArthur, Hainey and Boyle2012) undertook a systematic literature review encompassing 129 papers (published between 2004 and 2009) with empirical evidence regarding the effects of playing computer games on learning and engagement. The results indicated that “playing computer games is linked to a range of perceptual, cognitive, behavioural, affective, and motivational impacts and outcomes” (Connolly et al., Reference Connolly, Boyle, MacArthur, Hainey and Boyle2012: 661). The review also showed that knowledge acquisition (or content understanding), as well as affective and motivational outcomes, was the most significant result of gameplay.

Cornillie et al. (Reference Cornillie, Thorne and Desmet2012) carried out a database search to identify general trends in digital game-based language learning research over three decades and found that, between 2001 and 2010, most of the research on digital gaming was design based – that is, studies mainly focused on the conceptual design or development of a particular type of game-based language-learning environment. They also reported a growing number of empirical studies investigating the use of digital games in the domain of language learning.

Chiu et al. (Reference Chiu, Kao and Reynolds2012) completed a meta-analysis (i.e. a statistical method for summarizing and synthesizing the results of previous quantitative research to obtain a single index of the outcome with greater statistical power) of 14 studies that investigated the overall effects of digital game-based learning in an English as a foreign language (EFL) setting. They examined the effects of “drill and practice” games versus “meaningful and engaging” ones. In the former, players modify actions through trial and error to improve their scores, whereas the latter type of game involves higher order thinking activities such as exploration, hypothesis testing, and constructing objects. Chiu et al. (Reference Chiu, Kao and Reynolds2012) found a medium positive effect size in favor of digital game-based learning in the EFL setting. Their analysis also yielded a large effect size for meaningful and engaging games, but a small effect size for drill and practice games.

To date, no single review was located as focusing specifically on COTS MMOGs in the field of second or foreign language learning. The reviews conducted so far were more inclusive concerning the type of games, learning domains, or both. Connolly et al. (Reference Connolly, Boyle, MacArthur, Hainey and Boyle2012), for example, included empirical studies that had examined the positive impacts and outcomes of both digital and non-digital games with various purposes (entertainment, game for learning, serious games), genres (e.g. role-playing, strategy, and adventure), platforms for delivery (e.g. video console, PC, and online), and subject disciplines or curricular areas (e.g. health, language, and math). Moreover, the reviews that focused on the role of digital games in the field of second or foreign language learning adopted either a broader (e.g. Cornillie et al., Reference Cornillie, Thorne and Desmet2012) or more limited (e.g. Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Kao and Reynolds2012) scope concerning types of games. Cornillie et al. (Reference Cornillie, Thorne and Desmet2012) reviewed the studies that addressed – theoretically or empirically – the role of digital games (including MMOGs) for language learning, whereas Chiu et al. (Reference Chiu, Kao and Reynolds2012) examined the research over the effects of playing only digital educational games on language learning in an EFL setting. The literature suggests that previous syntheses did not thoroughly address MMOGs – in particular, COTS MMOGs as the focus of the current review – from an SLA perspective. Therefore, a more focused review is required to map L2 learning research in the context of recreational MMOGs regarding the topics investigated, the theoretical perspectives adopted, the approaches implemented, and the results obtained. More importantly, a review is warranted to provide some insights into the underlying processes of L2 development in the context of MMOGs by drawing on the findings of the current literature.

3. Method

The current study is a scoping review. This type of review aims to “map rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available, and can be undertaken as stand-alone projects in their own right, especially where an area is complex or has not been reviewed comprehensively before” (Mays, Roberts & Popay, Reference Mays, Roberts and Popay2001: 194). Unlike a systematic literature review, which “might typically focus on a well-defined question where appropriate study designs can be identified in advance,” a scoping review “tends to address broader topics where many different study designs might be applicable” (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005: 20). Moreover, while a systematic literature review seeks to answer questions from “a relatively narrow range of quality assessed studies,” a scoping review “is less likely to seek to address very specific research questions nor, consequently, to assess the quality of included studies” (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005: 20). Moreover, unlike a meta-analysis, a scoping review does not seek to summarize and synthesize the results of quantitative research studies using statistical techniques. As a scoping review, our study proposes to discover the extent, range, and nature of L2 research in the context of MMOGs.

3.1 Search procedure

First, five electronic databases – the U.S. Department of Education’s Education Resources Information Center, EBSCO’s Academic Search Complete and its Communication Source, ProQuest’s Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts, and the American Psychological Association’s PsycINFO – were searched using the combinations of keywords listed below. Some key journals were also hand searched, to ensure the effectiveness of the search procedure, including CALICO Journal, Computer Assisted Language Learning, International Journal of Game-Based Learning, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, Language Learning & Technology, and ReCALL. Next, a manual search was undertaken of the reference lists of the papers identified in the first step. Then, Google Scholar and Thomson Reuters’ Web of Science were used to locate articles that have cited the studies found in the first step. Finally, the abstracts and, in some cases, the main body of all papers were scanned to shortlist them for the review.

3.2 Search terms

The following composition of search terms was used by an expert to search the five electronic databases listed previously:

(DE “Video Games”) OR (DE “Computer Games”) OR AB ((game* or gaming) n2 (digital or online or video or simulation or computer* or mobile or multiplayer* or immersive or massive* or multiuser)) or mmorpg* or muds or moos or mmog or muve)

AND

(DE “Second Language Learning”) OR (DE “Bilingual Education” OR DE “College Second Language Programs” OR DE “English (Second Language)” OR DE “English for Special Purposes” OR DE “English Language Learners”) OR ((AB (language W1 (learn* OR acquisition OR second))) OR TI (language W1 (learn* OR acquisition OR second))) OR AB (esl OR efl OR ell) OR TI (esl OR efl OR ell) OR DE “Second language acquisition”))

The keywords were used independently and combined in order to locate as many publications as possible. The search was completed on December 4, 2015, and resulted in an initial selection of 348 papers.

3.3 Inclusion criteria

The papers had to (a) be published in the English language; (b) include empirical evidence (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed method) about L2 learning within or beyond the contexts of COTS MMOGs; and (c) be published after 2000. We excluded the studies conducted in the context of (a) synthetic immersive environments, or “visually rendered spaces which combine aspects of open social virtualities with goal-directed gaming models to address specific learning objectives” (Sykes, Oskoz & Thorne, Reference Sykes, Oskoz and Thorne2008: 528); (b) online virtual worlds (e.g. Second Life and ActiveWorlds), which are “more open-ended and/or predominantly socially-oriented virtual worlds” (Cornillie et al., Reference Cornillie, Thorne and Desmet2012: 247); and (c) simulation video games (e.g. The Sims and SimCopter), which lack two defining characteristics of a “game” as being rule-governed and involving competition (see Prensky, Reference Prensky2001). The Sims, for example, is a life simulation game series that focuses primarily on socialization (through simulating real-life situations and scenarios) rather than competitive, rule-governed, and objective-based gameplay. The games in this series are largely sandbox games (i.e. they lack any defined goals and rules or structures); therefore, players are free (from the structures and directions typically present in mainstream video games) to decide what to do, when, and how in the game setting.

Thirty-one studies (24 journal articles, three conference proceedings, two dissertations, one master’s thesis, and one book chapter) met the inclusion criteria. An overview of the studies is provided in the Appendix.

3.4 Coding of papers

The papers were coded by the first author according to their (a) purpose, (b) research paradigm (e.g. quantitative, qualitative, or mixed method), (c) theoretical (or conceptual) framework, (d) data collection procedure, (e) data analysis techniques, and (f) findings. To evaluate the quality of coding, a sample of five papers (16% of 31 articles) was coded independently by a second coder. A simple percentage agreement calculation found the inter-rater agreement to be 96%.

4. Findings

4.1 Research goals

Most of the studies had multiple research foci. As Table 1 shows, L2-related motivational and affective outcomes, L2 skills (predominantly vocabulary) acquisition, communicative competence (or discourse management strategies), and L2 production were the most frequently addressed topics in the papers. Other topics (including L2 literacy practices, skilled linguistic action and values realizing, practicing autonomy, L2 learning strategies, opportunities for negotiation of meaning, and the linguistic complexity of game-presented texts and game-external websites) were dealt with by one or two studies and accounted for 20% of the total frequency (i.e. 53).

4.2 Research paradigms, theories, and methodologies

Most (19 or 61%) of the studies were qualitative; there were only four quantitative and eight mixed-method studies. The qualitative works were mainly case studies that utilized a virtual ethnography approach, whereas the quantitative ones chiefly comprised quasi-experimental research.

Ten studies did not refer to any theoretical assumption underlying their hypotheses or choice of research methods. Some (e.g. Dixon, Reference *Dixon2014; Palmer, Reference *Palmer2010; Zheng, Young, Wagner & Brewer, Reference *Zheng, Young, Wagner and Brewer2009) adopted more than one theoretical perspective to frame their research. In 21 studies, we identified 13 theoretical frameworks, of which Vygotsky’s (Reference Vygotsky1978) sociocultural theory was the most frequently cited.

We also examined two significant features of research methodology – data collection and data analysis – within the papers. Thirteen data collection tools (see Table 2) were applied, with interviews (21%), observation (18%), chat logs (16%), and questionnaires (12.6%) the most widely utilized. We also pinpointed 16 different data analysis techniques, among which discourse analysis (19%), descriptive statistics (16%), paired/independent samples t tests (16%), and constant comparative analysis (12%) were the most frequently used.

Table 2 Data collection tools used in the papers

The studies also varied with respect to the number of participants, ranging from one (in Lee & Gerber, Reference *Lee and Gerber2013) to 86 (in Sylvén & Sundqvist, Reference *Sylvén and Sundqvist2012) (M=18.03, Mdn=7). The participants were of different age groups (10–37 years old, M=20.6, SD=5.1) and L2 proficiency levels, ranging from beginner to advanced levels. In 87% (27) of the studies, the participants were English as a second language (ESL) or EFL learners from diverse first language (L1) backgrounds. In about 10% (three) of the studies, the participants were learning other languages than English (i.e. Italian and Spanish); and one study (Thorne, Reference *Thorne2008) describes the intercultural communication between a Russian and an American learning each other’s native languages.

4.3 Findings of the papers

To synthesize the findings of the 31 studies, we borrowed the data analysis strategy from the grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008). We combined the papers’ main findings – as reported in the original papers – and created a textual database of approximately 20 pages. We implemented open coding as “breaking data apart and delineating concepts to stand for blocks of raw data” and axial coding as “the act of relating concepts/categories to each other” (Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008: 198) to code the findings. Then we allocated codes with a similar focus to a single category. Due to their multiple research foci and naturally different results, some papers were assigned to more than one category. The coding led to the identification of five main categories: design features of MMOGs, MMOGs’ social and affective affordances, opportunities afforded for second language and culture learning, and L2 learning outcomes.

4.3.1 Design features of MMOGs

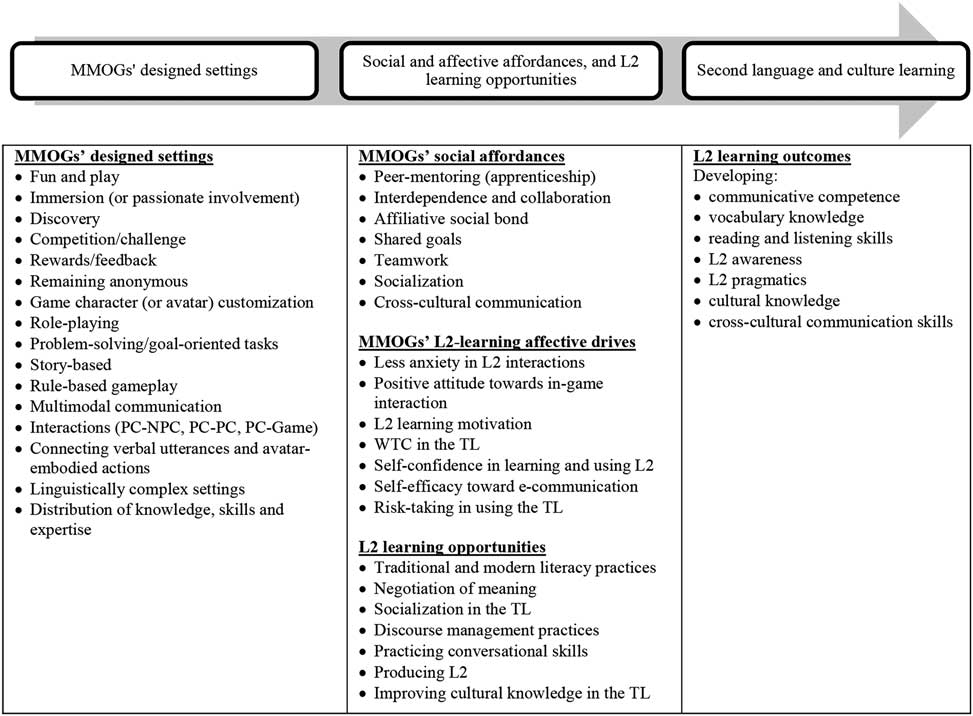

Some studies highlighted and characterized a range of MMOGs’ design features (see Figure 1), which help create an engaging multimodal communication setting. By drawing on these elements, some scholars elaborated on the social and affective affordances that MMOGs provide for L2 game players. They considered, for example, a range of MMOGs’ design features that allow gamers to remain anonymous (through adopting and customizing digitally embodied characters known as avatars) (e.g. Peterson, Reference *Peterson2011, Reference *Peterson2012a; Reinders & Wattana, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2014, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2015b), to use multiple routes for and modes of communication (e.g. Rama et al., Reference *Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012), to practice autonomy in governing their gameplay (Chik, Reference *Chik2014) and language learning (Bytheway, Reference *Bytheway2014), and to connect “verbal utterances and avatar-embodied actions” (Newgarden, Zheng & Liu, Reference *Newgarden, Zheng and Liu2015: 38) in their interactions.

Figure 1 Hypothetical relationships among the themes identified in the papers’ findings.

The linguistic environment of MMOGs, as one of these design features, was investigated by Thorne, Fischer and Lu (Reference *Thorne, Fischer and Lu2012). Their examination of the texts used in WoW’s quests and three of the most frequently visited WoW-related websites attested to the richness of the language in terms of readability, lexical sophistication, lexical diversity, and syntactic complexity. They argued that these linguistically complex texts “are attended to because they are highly relevant to the actions, decisions, and problem-solving at hand” (Thorne, Fischer & Lu, Reference *Thorne, Fischer and Lu2012: 298), reasoning that such texts are functionally tied to the game’s activities and serve the players’ immediate and situated game-playing needs. Their argument corroborates the “multimodal,” “text,” and “situated meaning” principles advanced by Gee (Reference Gee2003) in relation to video games.

The multimodal principle posits that “in video games, meaning, thinking, and learning are linked to multiple modalities (words, images, actions, sounds, etc.) and not just to words” (Gee, Reference Gee2003: 108). Drawing on the similar construct, Hattie and Yates (Reference Hattie and Yates2013: 115) asserted that “we all learn well when the inputs we experience are multi-modal or conveyed through different media.” According to text principle, “Texts are not understood purely verbally (i.e. only in terms of the definitions of the words in the text and their text-internal relationships to each other) but are understood in terms of embodied experiences” (Gee, Reference Gee2003: 107). Moreover, according to the situated meaning principle, “The meanings of signs (words, actions, objects, artifacts, symbols, texts, etc.) are situated in embodied experience. Meanings are not general or decontextualized. Whatever generality meanings come to have is discovered bottom up via embodied experiences” (Gee, Reference Gee2003: 107).

4.3.2 MMOGs’ social and affective affordances

Several studies have underscored the significant roles that design features of MMOGs play in promoting some positive social norms in the game environment such as peer mentoring, interdependence, collaboration, and teamwork. Embracing these social norms within the game environment seems to have created an L2 learning environment that affords positive social and affective drives theorized as being crucial for L2 development.

The studies revealed that MMOGs’ social context encourages communal L2 learning practices (Chik, Reference *Chik2014), inspires expert–novice interactions (Rama, Black, van Es & Warschauer, Reference *Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012; Thorne, Reference *Thorne2008), affords multiple routes for and modes of communication in the game world (Rama et al., Reference *Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012), and creates an “affiliative social bond” among participants in that sphere (Thorne, Reference *Thorne2008). These affordances help to create socially dependable, low-anxiety environments in which L2 learners can partake in collaborative game activities and socialize confidently in the TL. Chik (Reference *Chik2014), for example, observed that experienced gamers provided novice players with advice on both gaming strategies and using L2 gaming for language-learning purposes. As she noted, more experienced players regularly shared helpful resources such as walkthroughs, video tutorials, fan fiction, and fan art on interest-driven websites. Thorne’s (Reference *Thorne2008) research on intercultural communication within WoW also highlighted the establishment of an affiliative social bond between the gamers that sustained the participants’ in-game collaboration and expanded their social interactions to out-of-the-game contexts.

Bytheway (Reference *Bytheway2014: 9) observed that WoW provides highly semiotic interactive contexts characterized by particular in-game cultures that “encourage creativity, decrease anxiety, force interaction, demand cooperative and autonomous learning, increase motivation, and reward curiosity.” Her findings are supported by Peterson (Reference *Peterson2011, Reference *Peterson2012a), who studied linguistic and social interactions in the context of two MMOGs. Participants in Peterson’s studies affirmed that interactions through personalized avatars increased the level of immersion in and engagement with the games’ social environments. Peterson found that interacting through personalized avatars, which offer gamers the opportunity to remain anonymous throughout gameplay, reduces identifying social cues, facilitates gamers’ self-expression, enhances risk-taking in TL use, and motivates the gamers to socialize actively with other players. In the same vein, Reinders and Wattana (Reference *Reinders and Wattana2014, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2015b) contended that anonymity due to the absence of an open public sphere in the game helped to lower language learners’ communication anxiety and increased their self-perceived communicative competence. They concluded that the affective affordances of the game environment were the main reasons that participants felt more willing to use English in the game setting. Zheng, Young, Brewer and Wagner (Reference *Zheng, Young, Brewer and Wagner2010) also recognized that MMOG players, compared with non-players, developed higher levels of self-efficacy toward using English with native English speakers (NESs) and exhibited a more positive attitude with respect to learning the TL.

4.3.3 L2 learning opportunities

Sixteen papers highlighted different opportunities afforded within and beyond MMOG contexts for practicing and developing L2 skills. Sorted according to the number of times these opportunities have been acknowledged, these include opportunities for (a) negotiation of meaning, (b) discourse management practices, (c) increased production of L2, (d) traditional and modern literacy practices, (e) socialization in the TL, (f) intercultural communications, and (g) practicing conversational skills.

Researchers have found that verbal interactions in the world of MMOGs promote opportunities for negotiations of meaning, which is shown in the SLA literature (e.g. Smith, Reference Smith2004, Reference Smith2005) as being facilitative of L2 learning processes. Dixon (Reference *Dixon2014) identified “requesting” and “checking” as the most commonly implemented communication strategies in the negotiations of meaning, which were triggered mostly by player-produced and game-environmental inputs. Peterson (Reference *Peterson2012a), too, found that L2 learners overcame in-game communication challenges through involvement in the co-construction of meaning, observing that learners employed “continuers” (e.g. confirmation check, requests for assistance, and requests for clarification) as negotiation-of-meaning tools in order to maintain interactions. In addition, Thorne’s (Reference *Thorne2008: 321) analysis of naturally occurring dialogs in the context of WoW showed that “both participants provided expert knowledge, language-specific explicit corrections, made requests for help, and collaboratively assembled successful repair sequences.” These findings appear promising in view of the interaction hypothesis (Long, Reference Long1981) or approach (Gass & Mackey, Reference Gass and Mackey2007), suggesting that conversational modifications between an L2 learner and other interlocutor(s) with a view to resolving a communication breakdown are beneficial for L2 development.

Additionally, some scholars (e.g. Peterson, Reference *Peterson2011, Reference *Peterson2012b; Rama et al., Reference *Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012; Reinders & Wattana, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2011) underlined the opportunities for utilizing adaptive discourse management strategies to communicate effectively during gameplay. Peterson (Reference *Peterson2011, Reference *Peterson2012b) identified various approaches – such as the use of acronyms and contractions, combinations of keyboard symbols, strings of dots to signal a pause or show uncertainty, quotation marks to attract attention and display emphasis – and inferred that the application of these strategies “facilitated the consistent production of coherent TL output” (Peterson, Reference *Peterson2012b: 89). Through an analysis of learners’ in-game utterances, Rama et al. (Reference *Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012) also observed the occurrence of frequent pauses and use of abbreviated and orthographically and stylistically non-standard language. They believed that, “For language learners, this affords valuable leeway for pauses to formulate utterances and inculcates an acceptance of errors, qualities that may facilitate the performance of communicative competence within this context” (Rama et al., Reference *Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012: 332). Such studies suggest that learners adopt innovative discourse management strategies to meet the demands of in-game communication, such as focusing on meaning, catching up with the rapid pace of communication, and compensating for the absence of paralinguistic features.

The amount of L2 produced within game interactions can indicate how far the learners are comfortable and confident in their social interactions with other playing characters (PCs) (Rankin et al., Reference *Rankin, Gold and Gooch2006). It also indicates the degree of opportunities a game context provides for L2 learners to produce language output that is, according to Swain’s (Reference Swain1985) output hypothesis, crucial in the process of L2 development. Reinders and Wattana (Reference *Reinders and Wattana2011, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2015a) showed that gameplay had positive effects on the quantity of L2 interaction (as measured by the number of words and length of turns) via text- and voice-based chat. These results may differ for students possessing different levels of L2 proficiency. For example, in Rankin et al.’s (2006) study, advanced ESL students generated 6 and 2.5 times more chat messages than the high-level beginners and the intermediate students, respectively. Rankin, Morrison, McNeal, Gooch and Shute (Reference *Rankin, Morrison, McNeal, Gooch and Shute2009) also revealed a non-significant difference between advanced ESL students and NESs as regards the number of chat messages produced. This suggests that, unlike low proficiency L2 learners, advanced students are highly encouraged in the game to initiate and sustain social interactions with other gamers.

Studies (e.g. Li, Reference *Li2011; Ryu, Reference *Ryu2011) also acknowledged the opportunities that MMOGs offer for developing traditional and modern literacies. Li (Reference *Li2011: 147) conceptualized literacy from a sociocultural perspective, defining it as “effective functioning in situated social practices through meaning making across various modalities (texts, images, symbols, numerals, sound, movement and so forth) in a multimodal environment.” He observed that reading and decision-making were respectively the first- and second-most frequently occurring literacy activities, and information seeking was the only literacy practice that took place both within and around WoW gameplay. Ryu (Reference *Ryu2011) also sought to discover how non-native English speakers (NNESs) develop multi-literacies as they communicate asynchronously in the context of CivFanatics, a beyond-game affinity space for players of Civilization. Ryu observed that participants had a chance to improve their traditional literacy through using different types of text (e.g. descriptive, argumentative, narrative) to describe their experiences, argue for their gaming strategies, and create stories based on gameplay. Ryu’s study also highlighted the opportunities for practicing other types of literacy, including “multimodal literacy,” “gaming literacy,” “multilingual literacy,” and “multicultural literacy.”

Some scholars (Palmer, Reference *Palmer2010; Rama et al., Reference *Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012; Rankin et al., Reference *Rankin, Morrison, McNeal, Gooch and Shute2009) also acknowledged that participation in MMOG virtual communities provided opportunities for L2 socialization as a developmental process that involves “learning to use language in socially and pragmatically appropriate, locally meaningful ways, and as a means of engaging with others in the course of – indeed, in the constitution of – everyday interactions and activities” (Garrett, Reference Garrett2008: 190). For example, in an ethnographic case study, Palmer (Reference *Palmer2010) investigated the process of L2 socialization in the virtual community of WoW through monitoring the participants’ pragmatic development in the Spanish language. She observed that the participants improved their abilities to socialize with Spanish gamers by performing a range of appropriate pragmatic moves. Rama et al. (Reference *Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012: 337) also concluded, “As sociocultural contexts characterized by shared proclivities rather than language ability, MMOGs provide unique contexts for language learning and socialization that are a marked contrast to the insulated communicative environments of many language classrooms.” Opportunities for transcultural and intercultural communication within MMOGs’ social settings are also highlighted by some scholars such as Thorne (Reference *Thorne2008) and Zheng et al. (Reference *Zheng, Young, Wagner and Brewer2009). They argued that bi- and sometimes multilingual communication settings of MMOGs provide opportunities for intercultural (and transcultural) communications among gamers located in diverse geographic locations. Zheng et al. (Reference *Zheng, Young, Wagner and Brewer2009: 504) discovered that “Fundamental to the acquisition of pragmatics, syntax, semantics, and discourse practices during the collaboration was the dyad’s socialization in framing and structuring their development of both linguistic and cultural knowledge and the codetermination of context and language.” Finally, Rankin et al. (Reference *Rankin, Gold and Gooch2006) emphasized that MMOG play enhanced the opportunities for intermediate and advanced ESL students to practice and improve their conversational skills as they were using the TL in their interactions with other PCs.

4.3.4 L2 learning outcomes

Communicative competence and vocabulary knowledge were the most frequently acknowledged L2 learning outcomes achieved through involvement in collaborative interactions within and beyond MMOGs. Conversely, very few studies reported L2 learners’ improvement in other language-related skills, such as reading, writing, listening, and speaking (e.g. Kongmee, Strachan, Montgomery & Pickard, Reference *Kongmee, Strachan, Montgomery and Pickard2011; Reinders & Wattana, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2011; Sylvén & Sundqvist, Reference *Sylvén and Sundqvist2012), and L2 awareness (Lee & Gerber, Reference *Lee and Gerber2013).

The review also suggests that meaning-oriented verbal interactions during MMOG play help L2 learners to develop communicative competence through practicing different discourse management strategies. Peterson (Reference *Peterson2012a), for example, discovered that L2 learners managed their in-game communications through the appropriate use of positive politeness strategies, informal language, small talk, humor, and lengthy leave-takings. Rama et al. (Reference *Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012) found that playing WoW prioritizes sociolinguistic competence (i.e. socially appropriate language use) and strategic competence (i.e. proper use of communication strategies) as the two salient components of communicative competence (Canale & Swain, Reference Canale and Swain1980). As they asserted, “Play in MMOGs favors these forms of communicative competence, which places emphasis on contextualized meaning rather than grammatical and lexical correctness of standard language forms” (Rama et al., Reference *Rama, Black, van Es and Warschauer2012: 330). The L2 learners in Palmer’s (Reference *Palmer2010) study also developed abilities to socialize with and integrate into the Spanish virtual communities in WoW by enriching their repertoire of pragmatic knowledge and performing a range of appropriate pragmatic moves including “a host of new greetings, goodbyes, and requests for help” (Palmer, Reference *Palmer2010: 307). As with Palmer (Reference *Palmer2010), Peterson (Reference *Peterson2012a), and Rama et al.’s (2012) studies, Rankin et al. (Reference *Rankin, Morrison, McNeal, Gooch and Shute2009) also found that social interactions in the game environment helped ESL students improve their “communicative performance,” defined as “the student’s ability to know what to say and when to say it based on the context” (Rankin et al., Reference *Rankin, Morrison, McNeal, Gooch and Shute2009: 166). Similarly, Reinders and Wattana (Reference *Reinders and Wattana2011) found that, although L2 interaction during the gameplay did not improve the accuracy and complexity of the students’ discourse, it encouraged them to use various discourse functions (e.g. greetings and questions) and practice different discourse management strategies (e.g. clarification requests, confirmation checks, and self-corrections) to communicate effectively within the game.

On the topic of improvement in L2 vocabulary as a key learning outcome, Rankin et al.’s (2006) study revealed that the students achieved a higher level of accuracy in defining L2 vocabulary words when the words were introduced more frequently in the conversations with non-playing characters (NPCs). Rankin et al. (Reference *Rankin, Morrison, McNeal, Gooch and Shute2009) undertook an investigation with 18 advanced ESL students randomly assigned to three conditions (i.e. attending class instruction, playing EverQuest II on their own, and with NESs). As they evaluated the participants’ recognition of the correct meaning of L2 vocabulary in the context of game tasks, the authors found a significant difference in post-test scores for the three groups. The students who collaborated with NES players performed better than the other two groups, who performed pretty much the same. However, the post-test scores for sentence usage revealed a significant difference for the students who received traditional classroom instruction. Sylvén and Sundqvist’s (Reference *Sylvén and Sundqvist2012) research confirmed Rankin et al.’s (2009) findings concerning the positive impact of gaming on the learners’ receptive L2 vocabulary knowledge, but their results depart from what Rankin et al. (Reference *Rankin, Morrison, McNeal, Gooch and Shute2009) discovered about the impact of gaming on L2 learners’ vocabulary usage (or production) skills. Specifically, Sylvén and Sundqvist (Reference *Sylvén and Sundqvist2012) found significant differences between non-gamers, moderate gamers, and frequent gamers in terms of L2 vocabulary recognition and production skills.

5. Discussion

Our review sought to ascertain how SLA is researched in the context of MMOGs, and what prior research findings suggest with regard to the affordances of these unconventional settings as venues for L2 learning and pedagogy. Figure 1 provides a conceptual framework that depicts projected relationships among the themes identified through our analysis. It is worth noting that there are many overlaps among the elements illustrated in Figure 1, and that the relationships between them should not be conceived of as merely linear and directional.

MMOGs’ design features were found to help to provide low-anxiety L2 learning environments (e.g. Reinders & Wattana, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2014, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2015b) that are collaborative (Voulgari & Komis, Reference Voulgari and Komis2011), socially interactive (Cole & Griffiths, Reference Cole and Griffiths2007), semiotically rich (Thorne & Fischer, Reference Thorne and Fischer2012), and linguistically complex (Thorne et al., Reference *Thorne, Fischer and Lu2012). Performing a broad range of activities using the TL, learners get involved in different types of interactions (with other PCs, NPCs, and the game context), which seem to hold opportunities for L2 learners to develop L2 literacies and increase their cross-cultural communication skills. Furthermore, small and large “communities of practice” (Wenger, Reference Wenger1998) emerge to accomplish increasingly challenging targets that warrant a high level of collaboration among PCs. Socializing and interacting with native or more competent speakers of the TL in an “affinity group” that is “bonded primarily through shared endeavors, goals, and practices” (Gee, Reference Gee2003: 197) appears less or non-intimidating for learners.

As Reinders and Wattana (Reference *Reinders and Wattana2015b: 50) speculated, gameplay in such an environment appears to initiate “a virtuous cycle of lowered anxiety, resulting in more L2 production, leading to greater self-satisfaction, and resulting in more motivation, which in turn led to a further lowering of affective barriers.” We further infer that a similar relationship can be found between the affective factors and the L2 learning opportunities identified in the context of MMOGs. L2 learners will likely take greater advantage of the possibilities as they grow increasingly self-confident in using the TL. Moreover, the more opportunities they seize to enhance their L2 skills, the more competent they can become in their L2 communications. In a logical sequence, this process can result in developing higher levels of self-efficacy beliefs, willingness to socialize, and positive attitudes towards L2 learning and gameplay. This chain of theorized impacts can be justified in light of willingness to communicate (WTC) theory (MacIntyre, Dörnyei, Clément & Noels, Reference MacIntyre, Dörnyei, Clément and Noels1998), suggesting that “interaction in a non-threatening environment conducive to authentic language use, will lead to increased self-confidence, decreased anxiety, and increased willingness to practise and use the L2” (Reinders & Wattana, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2015b: 43–44).

In addition to developing positive affective and motivational drives toward L2 learning and socialization, we found that L2 learners can enrich their repertoire of vocabulary knowledge and enhance their communicative competence. Conversely, in spite of a large quantity of L2 interactions and production during gameplay (Rankin et al., Reference *Rankin, Gold and Gooch2006; Rankin et al., Reference *Rankin, Morrison, McNeal, Gooch and Shute2009; Reinders & Wattana, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2011, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2015a), no significant improvement was observed in the learners’ discourse in terms of accuracy and complexity (e.g. Palmer, Reference *Palmer2010; Reinders & Wattana, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2011; Zheng et al., Reference *Zheng, Young, Brewer and Wagner2010). This finding appears to partly contradict assumptions underlying interactionist approach theorizing that “[n]egotiation for meaning, and especially negotiation that triggers interactional adjustments by the native speaker or more competent interlocutor, facilitates acquisition because it connects input, internal learner capacities, particularly selective attention, and output in productive ways” (Long, Reference Long1996: 451). The first hypothesis is that very few if any communication breakdowns occur during interactions, and, when they do occur, they are not negotiated, as in Peterson’s (Reference *Peterson2012b) study. The second hypothesis is that even when negotiations of meaning do take place, they do not entail interactional adjustments; or, in some cases of interactional adjustments, the learners may fail to notice the gap in their interlanguage. The role of “noticing” or “selective attention” in the process of L2 learning is emphasized in Schmidt’s (Reference Schmidt1990, Reference Schmidt1992) noticing hypothesis, and also reflected in a learning principle established by Hattie and Yates (Reference Hattie and Yates2013: 115), which states that “When the mind actively does something with the stimulus, it becomes memorable.” Finally, the third hypothesis concerns the lack of opportunity or motivation for reviewing, practicing, and eventually internalizing new forms of language having been provided (through interactional adjustments) and noticed by the learners.

MMOGs afford multiple routes and modes of communication that can inspire the liberal and innovative use of language. During gameplay, language is utilized parsimoniously – through using the least morphological characters – for communicating in the most efficient manner. This likely explains, at least partially, why vocabulary and communicative competence were identified as the most frequently developed L2 skills in the context of MMOGs, yet L2 development falls way behind in terms of accuracy and complexity. Highly time-sensitive and goal-oriented verbal interactions – or in Reinders and Wattana’s (Reference *Reinders and Wattana2011: 16) terms, “the demands for simultaneous communication flow” – during gameplay encourage a form of communication that is unorthodox in language form, succinct in nature, and innovative in style. Example features of this communication style comprise the replacement of letters with numbers and symbols, the innovative spelling of words, the omission of articles, and the use of contractions and abbreviations. Thus, L2 research in immersive multiplayer games cannot be addressed comprehensively (Palmer, Reference *Palmer2010; Rankin et al., Reference *Rankin, Morrison, McNeal, Gooch and Shute2009) when language is perceived strictly as “the only linguistic mode instead of part of a multimodal ensemble of modes” (Newgarden et al., Reference *Newgarden, Zheng and Liu2015: 23) of communication. Adopting a more liberal perspective toward the concept of language is warranted. For example, “from an ecological perspective, ‘movement, process, and action’, things that people do … are inextricably integrated with language, i.e., they are part of languaging” (Newgarden et al., Reference *Newgarden, Zheng and Liu2015: 23). This view aligns with complexity and dynamic systems theory (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, Reference Larsen-Freeman and Cameron2008), which rejects the SLA research approaches that conceive of L2 development as merely “the taking in of linguistic forms by learners” (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, Reference Larsen-Freeman and Cameron2008: 135).

6. Future research

Considering that most of the reviewed studies were qualitative, adopting an optimum combination of different research paradigms appears warranted. We contend that qualitative work has set the stage well for more quantitative investigations, which could present quantifiable indicators of L2 learning in MMOG settings. That is, future research needs to invest more in quantitative (e.g. controlled experimental or quasi-experimental) studies in order to substantiate what has been explored in earlier qualitative work and verify SLA scholarly theory concerning the affordances of MMOGs for second language and culture learning.

The second issue that needs to be addressed concerns the quality of research in the current literature. Our review revealed that about 57% of qualitative studies failed to report (or implement) measures ensuring the “credibility,” “neutrality or confirmability,” “consistency or dependability,” and “applicability or transferability” (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985) of their data analysis and findings. In some cases (Alp & Patat, Reference *Alp and Patat2015; Kongmee et al., Reference *Kongmee, Strachan, Montgomery and Pickard2011; Rankin et al., Reference *Rankin, Gold and Gooch2006; Thorne, Reference *Thorne2008), the researchers did not even mention the approach(es) they adopted to analyze the qualitative part of their data. Similarly, quantitative studies were found to suffer from methodological deficiencies such as inappropriate sampling procedures and failure to implement measures required to ensure the validity and reliability of their data collection and data analysis tools and methods.

Related to concerns about the quality of the studies is the absence of a theoretical or conceptual framework. About 32% of the studies did not refer to any theoretical framework (or assumptions) underlying their hypotheses and choice of research methods. Correspondingly, a general limitation that applies to the whole body of research in this area is that a very limited range of theories has been drawn upon to examine L2 learning behavior in MMOG settings. Vygotsky’s (Reference Vygotsky1978) sociocultural theory was cited in nine (circa 29%) of the studies, with some researchers simply citing the theory without actually incorporating its principles, constructs, or methodology. Due to the interdisciplinary nature of L2 research in the MMOG environment, adoption of an eclectic range of theoretical perspectives is warranted to encompass multiple aspects of the phenomenon, which are in constant and dynamic interaction with one another in a complex system.

Finally, it is noteworthy that along with distinctive MMOG-related variables (e.g. type and genre), there also exists a range of different factors associated with L2 learners (e.g. age, gender, personality, L2 learning and gameplay motivation, learning styles, and L2 proficiency). To capture the dynamics of L2 learning in MMOG ecologies, a reasonable approach might be to incorporate all variables into a learning model particularly formulated to explain how, to what extent, and under what circumstances playing an MMOG can contribute to one’s L2 development. Such an approach echoes complexity and dynamic systems theory (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, Reference Larsen-Freeman and Cameron2008), which “aims to account for how the interacting parts of a complex system give rise to the system’s collective behavior and how such a system simultaneously interacts with its environment” (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, Reference Larsen-Freeman and Cameron2008: 1). One of the most daunting challenges facing researchers in the future would be the multiplicity and potential conflation of different variables (e.g. game- and learner-related) that explain the phenomena under investigation.

7. Limitations

A scoping review “can provide a rigorous and transparent method for mapping areas of research” (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005: 30). Adopting this methodology allowed us to present an overview of the current research on “vernacular” MMOGs in the field of SLA, and determine the volume, variety, nature, and characteristics of the primary research conducted so far. Equally, though, the current study also features some limitations due to the nature of scoping reviews. Arguably, the most serious issue is that the quality of evidence in the primary research included in our study is not critically assessed. Results from different types of sources (e.g. peer-reviewed academic papers, conference proceedings, postgraduate theses and dissertations) were grouped and reported without allocating more weight to one particular source over another. Therefore, the current study, as a typical scoping review, “cannot determine whether particular studies provide robust or generalizable findings” (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005: 27).

Moreover, because of the small number of quantitative studies in this area of research, meta-analysis was impossible to conduct. Presumably, this should be regarded as a limitation of the current state of research that warrants more quantitative investigations. The four quantitative studies and the quantitative sections of the eight mixed-method studies differed in terms of, for example, their design, focus, and participants. They covered a wide range of topics too. There were only a few studies that investigated similar topics such as vocabulary acquisition, quantity of L2 production, self-efficacy toward L2 use, and communication strategies.

Finally, some researchers (Rankin et al., Reference *Rankin, Morrison, McNeal, Gooch and Shute2009; Reinders & Wattana, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2011, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2014, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2015a, Reference *Reinders and Wattana2015b) had modified the games by, for example, including some instructions and quests to ensure the appropriateness of the MMOGs to the learning contexts under study. Although these five studies do not fall 100% under the scope of naturalistic CALL, we had to synthesize and report their results with those obtained from the research papers in which L2 development was investigated in original (or unaltered) versions of the games.

8. Conclusion

MMOGs have ignited some degree of optimism – among SLA scholars – that such socially and semiotically rich contexts can afford learners with authentic opportunities to socialize in the TL. This perspective has inspired researchers to investigate how the affordances of MMOGs might be harnessed for the improvement of L2-related skills. This review revealed that MMOGs encourage learners to get actively involved in L2 socialization and collaborative interactions with other PCs to perform a variety of goal-oriented tasks within and beyond game contexts. The findings do appear to suggest that playing MMOGs in the TL helps improve receptive L2 vocabulary knowledge and transform L2 learners into more resourceful communicators who venture to utilize various discourse management strategies to communicate effectively in their interactions. The current review also showed that most of the studies are qualitative, very limited aspects of L2 learning have been researched, the quality of studies needs to be improved, and that more innovative research models need to be designed to explore the cognitive processes underlying SLA in such dynamic and complex environments. Second language and culture learning within and beyond MMOGs’ settings need to be studied more thoroughly by conducting a balanced combination of research paradigms and adopting more diverse theoretical perspectives within a dynamic system that encompasses both game- and learner-related variables.

Ethical statement

There are no ethical issues to declare for this review paper.

About the authors

Nasser Jabbari received his PhD in TESOL at Texas A&M University, USA. His primary research interests include both naturalistic and tutorial CALL. His current research focuses on the psycholinguistic and sociocultural processes underlying L2 learning and socialization in the multilingual and multicultural contexts of massively multiplayer online (role-playing) games (MMORPGs).

Zohreh R. Eslami is a professor in ESL education, Department of Teaching, Learning, and Culture at Texas A&M University, USA, and the Liberal Arts program chair at Texas A&M University, Qatar. Her research interests include intercultural pragmatics, instructional pragmatics, pragmatic development, L2 reading in content areas, technology and language learning/teaching, and ESL teacher education.