Wars are costly. How countries plan to pay for these costs affects the proclivity of war. While scholars agree that finance and economics are important factors in explaining war onset, there is disagreement on the exact role. To add to this debate, this study focuses on how the dynamics of the sovereign credit market can inform states about adversaries’ intentions and resolve during interstate disputes. These signaling dynamics can reduce information asymmetry between states and decrease the probability that disputes escalate to wars. Market actors can facilitate shared expectations between states about the risk of conflict and help avoid unnecessary military tension. While other scholars have connected finance to peaceful outcomes, most have focused on finance’s ability to directly constrain states’ behavior through a coordinated effort. For example, Polanyi argued that financiers have incentives to prevent war, and he attributed the Hundred Years Peace (1816–1914) to the constraining power of finance (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1944). In this study, I argue that finance’s effect on war is not solely through constraining states. Instead, finance provides a means to signal information between states. The contribution of this study to the interdependence and war research is demonstrating the strategic importance of nonstate actors—financial intermediaries—rather than treating finance as a passive decision maker in international relations.

This article reevaluates the relationship between finance and war, in general, and during the Hundred Years Peace, in particular. In the context of these theoretical expectations, I examine the lending of the Rothschild bank to Austria and other European powers in the nineteenth century. I analyze the Rothschilds’s assessments of European interstate crises and determine whether the Rothschilds’s actions affected interstate crisis outcomes.

While this article’s empirical approach has a historical focus, the argument and subsequent findings have implications on contemporary international relations. The signaling effects of lenders are borne out of market imperfections and state-market relationships. Financial actors are often implicitly assumed to be operating in competitive market conditions, thus most research has ignored the potential information advantages enjoyed by some market actors. Limited economic competition can provide some financial actors the incentives to gain information advantages in the market. These information advantages can have repercussions on crisis bargaining between states in asymmetric information environments. While politics can limit economic competition, this article shows how limited economic competition affects politics, specifically the onset of war.

Interdependence, Finance, and War

Emmanuel Kant, Adam Smith, and David Ricardo connected economic exchange and peace, which inspires modern research on interdependence and peace (Anderson and Souva Reference Anderson and Souva2010; Barbieri Reference Barbieri2002; Dafoe Reference Dafoe2011; Gartzke Reference Gartzke2007; McDonald Reference McDonald2009; Oneal and Russet Reference Oneal and Russet1999). There is varied treatment of these complex relationships. For some, economic exchange and interdependence are mechanisms that help explain why democracies do not fight each other, while others have viewed economic exchanges as a confounding factor in the democratic peace (Gartzke Reference Gartzke2007; McDonald Reference McDonald2009).

Similarly, there is disagreement on how economic exchange leads to peace. Some argue that interdependent states avoid conflict because of the opportunity costs of fighting and fear of lost trade (Hirschman Reference Hirschman2013). Conversely, Copeland argues that expectations of lost trade may exacerbate conflict (Copeland Reference Copeland2015). Others have argued that opportunity costs have an indeterminate effect on peace because if a state is reluctant to go to war because of trade losses, this will embolden adversaries to push for more concessions in crisis bargaining (Gartzke et al. Reference Gartzke, Li and Boehmer2001; Morrow Reference Morrow1999). Instead, interdependence and economic exchange provide states with policy tools with which to signal to each other (Gartzke et al. Reference Gartzke, Li and Boehmer2001; Morrow Reference Morrow1999).

While this liberal and commercial peace literature has led to important empirical implications for the study of war, economic actors are often only given a passive role in this analysis. States remain the focal point. There are exceptions, as some scholars have examined how economic exchange motivate domestic groups to attempt to influence war policy (Kirshner Reference Kirshner2007; McDonald Reference McDonald2009; Simmons Reference Simmons, Mansfield and Pollins2003). Like opportunity costs, domestic groups constraining (or encouraging) governments’ war policies should have an indeterminate effect on the likelihood of war. If a domestic group is constraining one government from pursuing war, an adversarial state may be emboldened to make more aggressive demands from the constrained state. For example, while domestic groups successfully pressured the French government to maintain the stability of the franc at the expense of a deterrent mobilization against Nazi Germany in the 1930s, Nazi Germany was emboldened by France’s unwillingness to mobilize (Kirshner Reference Kirshner2007: 115).

When exploring the role of economics in war, some have focused more on financial exchange, particularly on the relationship between sovereign credit and conflict. Credit is shown to be crucial for security issues, including fiscal capacity, outcomes of enduring rivalries, positions in global leadership, war outcomes, and crisis bargaining (Kinne and Bunte Reference Kinne and Bunteforthcoming; Queralt Reference Queralt2016; Rasler and Thompson Reference Rasler and Thompson1983; Schultz and Weingast Reference Schultz2003; Shea Reference Shea2014, Reference Shea2016; Slantchev Reference Slantchev2012; Zielinski Reference Zielinski2016). Credit provides economic and political benefits to sovereigns, especially for wars. As a result, the sample of states observed in wars behave differently in the credit market given the importance of credit to war (Shea and Poast Reference Shea and Poast2018). For example, Shea and Poast (Reference Shea and Poast2018) demonstrate that states at risk at war will default less to ensure their access to credit if war begins.

Given the economic and political benefits of credit for war, some scholars have argued that investors can use their leverage to influence government decisions, specifically to constrain states from going to war (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1944). Polanyi connects the haute finance to the century of relative peace from 1815 to 1914, arguing that finance’s peace interest generally prevented war on the European continent during this time. Financial interests are a constraining, pacifistic force within a society, though these interests are not always successful in constraining a government from going to war (Kirshner Reference Kirshner2007). The influence of finance, or any pluralist group depends on its organizational capacity to affect government policy (Simmons Reference Simmons, Mansfield and Pollins2003).

Flandreau and Flores reconstruct and reevaluate Polanyi’s argument by focusing on “prestigious” financial intermediaries with competitive advantages in the lending market (Flandreau and Flores Reference Flandreau and Flores2012). These prestigious banks have incentives to provide a credible certification of a state’s creditworthiness because of their long-term motivations to provide accurate credit risk assessments. Therefore, prestigious banks only provide certification to states that do not risk deviating from creditworthy behavior and, as part of that, are not at risk to go to war. I extend this logic, arguing that these signaling dynamics should not only inform bond buyers about states’ creditworthiness as a function of international conflict, but these signaling dynamics should extend to other states as well. As a result, the financial actions of financial intermediaries with informational advantages affect states’ crisis decision making.

Signaling Dynamics of Finance in Interstate Crises

War increases budgetary pressures, shortens leaders’ time horizons, and creates economic instability. As a result, states’ risk of default increases. To avoid investment losses, finance has incentives to avoid lending to states likely to go to war and generally oppose aggressive foreign policies (Kirshner Reference Kirshner2007). Withholding credit could constrain states because of the lack of credit or more expensive credit should decrease a state’s value for war. Poorer credit access should decrease the probability of victory, increase costs, or both.

States accepting higher costs in the credit market or being shut out of the credit market completely, however, will not always decrease the probability of conflict. While the decreased value for war may make one state wary of war, it may simultaneously embolden an adversarial state to demand more in negotiations. Morrow makes a similar argument related to the relationship between trade and war, while Gartzke, Li, and Boehmer argue generally that any factor that discourages aggression by one party encourages aggression in others (Gartzke et al. Reference Gartzke, Li and Boehmer2001; Morrow Reference Morrow1999). As a result, investors’ ability to directly constrain the outbreak of war is limited at the dyadic or systemic level. Instead of constraining, finance signals information about states’ resolve and intentions. This information dynamic has a direct effect on the probability of war.

To illustrate the signaling role of finance, consider a crisis game akin to Fearon and others’ bargaining models of war (Fearon Reference Fearon1995; Gartzke Reference Gartzke1999; Powell Reference Powell2006). A state, R, makes a demand of some portion of a disputed good from another state, S. S decides to accept the offer or start a war. Each state’s utility is a function of how much of a disputed good it controls at the end of the crisis. Under this framework, bargaining can resort to war because of states cannot credibly commit to a negotiated settlement or because states’ private information about resolve, coupled with incentives to misrepresent this information (Fearon Reference Fearon1995; Powell Reference Powell2006). My argument will focus on the latter explanation. Suppose S has incentives to claim it is resolved (has low costs) to secure a better offer from R, but R understands that weakly resolved states have incentives to claim they are resolved. There is some danger that R makes a high demand to a resolved S, and war begins.

Previous works analyze this canonical crisis framework, focusing on how states’ institutions or policies may reduce information asymmetry (Schultz Reference Schultz2001; Slantchev Reference Slantchev2011). This study adds to this line of research by examining how a nonstate actor, finance, can reduce asymmetry between states and thus reduce the likelihood of war. For example, suppose state S asks for a loan from a lender before state R makes its demand from S.Footnote 1 Lenders are profit motivated and thus will base decisions on profit expectations. A crisis ending in war would increase the risk of S defaulting on any loan, thus lowering expectations of profit. Conversely, a crisis ending in peace would offer the lender an opportunity to profit from the loan. Therefore, the lender will base decision of its beliefs of the likelihood of war and the risk of default. If the lender has some knowledge of SIs resolve to fight, lending behavior may help reveal information to the other state involved in the crisis.

There are three scenarios of interest that will inform R of S’s resolve: (1) The lender provides a loan to S because the lender knows that S is unresolved and will concede to high demands from R. The crisis will end peacefully, and the risk of default does not increase. (2) If the lender knows that S is resolved to fight, and expects that R will make an unacceptable offer, then the lender will withhold its loan. Under this scenario, R should only make low demands after observing no lending. (3) If the lender knows that S is resolved to fight, but expects that R will only make low (and thus acceptable) offers, then the lender will provide a loan. In the last scenario, we may observe war lending, as the lender’s expectation of RIs offer is uncertain, and R cannot perfectly determine whether S is resolved or not.

In these three scenarios, lenders have limited ability to affect the onset of a crisis. Finance might reveal information about state S that emboldens state R to make demands where it otherwise would not. The opposite is also true, where information about state S deters state R from making demands in the first place. Similarly, finance constrains war in limited scenarios. While loans may lower SIs costs of war, making war a more attractive option for S, this lessens the probability that R makes high demands. Thus, finance can directly constrain wars if credit lowers the costs of war to the point where no offer is acceptable to S or that the lack of credit access reduces a state’s value for war below zero, making every offer acceptable. The latter scenario is plausible if states fight over relatively low-stakes issues. For example, if we conceptualize the remilitarization of the Rhineland in 1936 and occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1939 as demands from Germany on France and Great Britain, these demands were not important enough for France or Great Britain to intervene given the high costs of fighting. However, as Germany increased its demands (i.e., the invasion of Poland), these demands were too much for either great power to accept and war began despite poor financial conditions. Therefore, if states are fighting over some good valuable enough, finance will have an indeterminate effect on the probability of war through the constrain mechanism. Where loans influence war in these situations is through information signaling, assuming the lender has some informational advantage with which to observe a state’s resolve.

Do investors have informational advantages about states’ intentions and resolve? Individual investors have little incentive to acquire information about sovereigns if there are opportunities to free ride on the information acquisition of other investors. This creates collective action problems if all investors have the same incentives. Yet, there are incentives for some financial intermediaries to acquire information about states to build or maintain their own reputations in the credit market (Flandreau and Flores Reference Flandreau and Flores2012). These intermediaries—designated as “prestigious” intermediaries—work to establish reputations of being “right,” which ultimately mitigates moral hazard problems in information acquisition in the sovereign credit market. Prestigious intermediaries’ incentives to acquire information decreases the probability of poor investments (Chemmanur and Fulghieri Reference Chemmanur and Fulghieri1994b). And better investments allow the intermediary to gain even more market control, which acts as a feedback mechanism to motivate prestigious intermediaries to acquire information.

To acquire information, financial intermediaries often engage in a type of monitoring called relational banking, which is the intimate investigation of customers to gather private information (Boot Reference Boot2000). Relational banking reduces the costs of monitoring, as the creditor extracts proprietary information from the borrower that facilitates future lending. In addition, relational banking reduces the transaction costs of exchange, provides a source of incumbency advantage, and brings flexibility to often rigid financial agreements (ibid.).

Prestigious intermediaries’ information acquisition produce externalities for not only uninformed investors but also other states. States are aware of these prestigious intermediaries’ information advantages. If states can use prestigious intermediaries’ informational advantages to learn about adversary’s intentions and capabilities, this may decrease the likelihood of war. If we assume that the costs of war make war ex post inefficient and that leaders are rational, then states are more likely to prefer a negotiated settlement to war under conditions of complete information (Fearon Reference Fearon1995). Given that prestigious intermediaries want states to avoid war to protect investments, prestigious intermediaries have incentives to share information with states to reduce information asymmetry between adversaries.

Lenders are not the only actors that have incentives to collect information in international relations. States have incentives to collect as much information as possible from other states to reduce asymmetric information and avoid the possibility of inefficient crisis outcomes. However, states do not always have incentives to share information with other states, as asymmetric information can also help bargaining positions. States may want to exaggerate their strength or resolve so they can demand more during crisis bargaining, or at least to deter larger demands from other states. Revealing private information may lessen the attractiveness of these bluffing strategies for states.

The information asymmetry dynamic between adversarial states in an interstate crisis is similar to the information dynamic between a state and lender in the sovereign credit market. Lenders want to lend to states that will uphold their debt obligations, but all states have incentives to claim they will repay their debt. This is a problem for states, as a lack of credibility will lessen the likelihood of loans.

States can engage in some costly activities that help distinguish themselves from poor creditworthy states. Repayment of debts during difficult times, creating electoral penalties, or establishing central banks may help states credibly promise debt repayment (McGillivray and Smith Reference McGillivray and Smith2008; Poast Reference Poast2015; Schultz and Weingast Reference Schultz2003; Tomz Reference Tomz2007). Alternatively, states may share exclusive, private information to lenders to increase credibility in the lending market. Lenders benefit from this private exchange, as it provides a first mover advantage in the market. Prestigious intermediaries with privileged information receive added profits in the form of the run-up value of loan and underwriting fees. More importantly, the private information allows lenders to develop a reputation of being “right,” which provides long-run profits and helps consolidate market control (Chemmanur and Fulghieri Reference Chemmanur and Fulghieri1994a).

If states do not provide prestigious intermediaries privileged information, prestigious intermediaries will refrain from lending. Without any privileged information prestigious intermediaries risk damaging their reputation in the market. States could turn to other lenders in the market for loans, but in a consolidated or near-monopolistic market, loans from nonprestigious intermediaries are more expensive for states and tend to undersubscribe because uninformed market actors will be dubious of investments not involving prestigious intermediaries (Flandreau and Flores Reference Flandreau and Flores2009). Prestigious intermediaries’ actions as a result of gaining that information may signal states’ true resolve. The problem for states trying to discern a signal from prestigious intermediaries’ behavior is that all types of intermediaries will want to avoid war, as the financial sector is averse to war (Kirshner Reference Kirshner2007). Therefore, there exists potential equilibria where prestigious intermediaries will provide false information to states to decrease the probability of war. Even a completely informed investor has incentives to use cheap talk to attempt to reduce tensions between states.

To increase the credibility of their statements, prestigious intermediaries can lend or withhold lending to states that are in interstate crises to strengthen their informational claims. If prestigious intermediaries do not like war, and if they believe that states are likely to enter war, then prestigious intermediaries are less likely to lend in equilibria where war is likely. However, if the risks of war are low, then prestigious intermediaries have incentives to lend. Whether prestigious intermediaries lend or not affects the credibility of the information the prestigious intermediaries share with states. While lending can add to the credibility of prestigious intermediaries’ information, prestigious intermediaries do not make lending decisions to increase their credibility. Instead, investors lend when they expect repayment. While not necessarily intentional, prestigious intermediaries’ actions provide insight into leaders’ decisions to enter or escalate conflict, signaling through lending and certification actions. Consistent with this argument, Flandreau and Flores argue that prestigious banks’ behavior provides valuable signals to bond buyers about the creditworthiness of states (Flandreau and Flores Reference Flandreau and Flores2012). Extending this logic, these signaling dynamics should not only inform bond buyers about states’ creditworthiness as a function of international conflict but these signaling dynamics should extend to other states as well.

For their part, state leaders have political incentives to learn from finance’s signals. Leaders that push their states into unsuccessful wars risk being removed from office (Debs and Goemans Reference Debs and Goemans2010). So if information from finance allows leaders to avoid suboptimal policy outcomes, leaders will listen. Leaders also have incentives to share private information with finance to facilitate loan transactions. Credit access not only improves a state’s chances of winning a war, credit also increases leaders’ likelihood of maintaining power (DiGiuseppe and Shea Reference DiGiuseppe and Shea2015, Reference DiGiuseppe and Shea2016; Morrison Reference Morrison2009). Credit provides leaders more resources with which to satisfy constituents and also provides a means to mitigate the influence of domestic opposition. Therefore, leaders have incentives to cultivate relationships in the financial market and pay attention to finance’s information.

By no means is the signaling dynamics surrounding finance and war a necessary explanation for war or peace. Leaders may have beliefs about their adversaries that deter them from war without needing finance to intervene. Alternatively, there are other ways that states may reduce information asymmetry (Gartzke et al. Reference Gartzke, Li and Boehmer2001). In addition, finance is not a sufficient explanation for war or peace because information asymmetry must exist between adversarial states for signaling to be effective. Therefore, I conceptualize finance as a contributing factor within the asymmetric bargaining dispute (Levy and Goertz Reference Levy and Goertz2007). When is finance most likely to contribute to reducing information asymmetry? As discussed in the preceding text, finance only gains information advantages when imperfect competitive conditions exist in the credit markets. In addition, I expect that signaling is important when states are in dispute of relatively high value. Finally, finance’s signaling may work differently for different states. In the illustrative example, finance’s signal comes from the decision to lend or not. However, some states are creditworthy enough to secure loans despite the risk of war (Shea and Poast Reference Shea and Poast2018). For these states, the lender may seek ways to offset the risk of lending with higher interest rates, which may also signal to adversarial states.

When lenders’ signals do reduce information asymmetry between states, the likelihood that states avoid war increases. This argument is consistent with mediation research that focuses on the role of third-party states in crisis bargaining (Favretto Reference Favretto2009). This research examines the effect of mediators’ presence on crisis outcomes, usually through some signaling mechanism. However, it is not always clear why these mediators are better informed than some of the states involved in the crisis or why the mediators are motivated to become involved in the crisis. In the theoretical framework of this study, prestigious intermediaries are better informed because of relational banking and are motivated by potential profits and losses. Instead of assuming that information and motivation are a given, these components are a function of the investors’ profit motives.

The Rothschilds and European Crises, 1815–66

This study challenges Polanyi’s explanation for the Hundred Years Peace. Rather than constrain state behavior during this era, finance sent signals during interstate crises. The following section tests whether these signaling dynamics alleviated information asymmetry between states, subsequently reducing the likelihood of war. Following Flandreau and Flores, the analysis focuses on the Rothschild Bank because of its dominance of the sovereign lending market for most of the nineteenth century (Flandreau and Flores Reference Flandreau and Flores2012). The Rothschild Bank, a family-operated bank, emerged after the Napoleonic Wars as the leader in sovereign lending in Europe. The bank built its financial empire by fulfilling the credit needs of states across Europe; this was done by transferring monies from sovereign to sovereign, or from sovereign to military fronts efficiently (Corti Reference Corti1928b; Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998). The Rothschild Bank was profit motivated and saw a continental war as the greatest threat to their profits. The analysis will focus on the Rothschild’s lending behavior as a function of their profit motives and examine the bank’s effect on war.

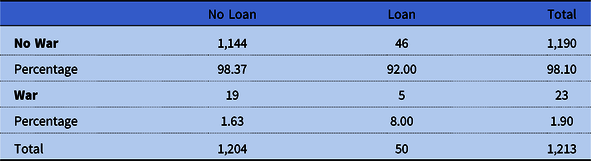

In a general sense, this relationship between finance and war is difficult to entangle. To demonstrate this complexity, Table 1 examines the country-years of all European states from 1816 to 1866, cross-tabulating whether they experienced a war or not (as coded by the Correlates of War data [Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, d’Orazio, Kenwick and Lane2015]) and whether a country received a loan from the Rothschild Bank in a given year (t) or the year before (t − 1) (data drawn from Rothschild Archive [2018]). These descriptive results suggest Rothschilds’s loans were associated with a higher risk of war. There are two explanations for this. Finance may want wars to occur, and thus enables them to occur. While consistent with Marxist–Leninist explanations of war, it contradicts finance’s supposed aversion to war (Kirshner Reference Kirshner2007). More plausibly, only the most creditworthy states can afford war and these same states attract loans. Thus a selection effect drives both wars and loans to be associated with each other (Shea and Poast Reference Shea and Poast2018).

Table 1. War and Rothschild loans

χ 2 = 10.44; p-value = 0.001.

Besides selection effects, the other difficulty to examining the general association between finance and war is distinguishing the meaning of nonevents. For example, without further analysis it is impossible to infer whether the states did not fight a war because (1) finance constrained them, (2) signals from finance helped avoid war, or (3) the states were never at risk of war to begin with. Similarly, Table 1 cannot demonstrate whether a state was denied a loan or did not need a loan in the first place. Therefore, to determine whether finance can affect the onset of war, the analysis should focus on cases that plausibly could have led to war. In addition, the cases should involve states in constant need of loans. To satisfy these conditions, this study will focus on the Rothschild bank’s involvement with Austria. Austria was at the epicenter of European affairs for most of the nineteenth century. Metternich’s system of repressing revolutions across Europe, while concurrently counterbalancing against France, involved Austria in most crises that plausibly could have led to war. As evidence of this, of the five cases in Table 1 that involve both war and loans, Austria represents four of them (the other being France’s involvement in Spain in 1823).

The second reason to focus on Austria is its financial solvency’s dependence on Rothschild’s lending. A cursory examination of Austria’s economic and fiscal conditions suggests that Austria was not a creditworthy state. High fiscal and economic instability, coupled with currency debasement and foreign policies, increased uncertainty around repayment (Mitchell Reference Mitchell1975). Austria also lacked democratic institutions or an independent central bank to increase its credibility in the market (Poast Reference Poast2015; Schultz and Weingast Reference Schultz2003). Austria was not only able to secure credit, but secured it at favorable conditions from the Rothschild Bank. In addition, the Rothschild Bank could have easily divested in Austria (as they eventually would in the 1860s), which makes Austria a most likely case to be constrained by finance. In other words, if the Rothschild bank constrained states from going to war, we would most likely observe that mechanism with Austria.

The empirical analysis utilizes a Causal Process Observations (CPO) approach to establish the empirical sequence of decision makers’ decisions to avoid war. This approach “provides information about context or mechanism” regarding an observation within a case (Brady and Collier Reference Brady and Collier2010: 252). There are several scholarly examples utilizing a CPO approach, all of which leverage the approach to test competing explanations against each other. For example, Haggard and Kaufman (Reference Haggard and Kaufman2012) examine the role of inequality in democratic transitions. More recently, Shea and Poast (Reference Shea and Poast2018) examine whether sovereign default is a by-product of war, particularly losing a war.Footnote 2

The CPO method is useful in examining rare events such as war, and can also identify complicated causal processes (Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2012: 5). With this approach, I can weigh evidence that states were either constrained from entering war because of their financial situation or whether finance offered information that allowed states to avoid wars. The approach has several additional advantages. First, the theoretical argument discussed in the preceding text expects that in some scenarios wars do not emerge and would thus be missed by methodologies that focus only on observable wars. Second, a case design allows the analysis to distinguish between signaling mechanisms and constraining mechanisms, effects that are not easily separable in noncase methodologies (Dafoe and Kelsey Reference Dafoe and Kelsey2014; Schultz Reference Schultz and Weingast1999).

To identify the cases that plausibly could lead to war, I used the Correlates of War data on militarized interstate disputes to identify any interstate crisis in which Austria was a principal participant from 1816 to 1866 (Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, d’Orazio, Kenwick and Lane2015).Footnote 3 This lead to eight cases.Footnote 4 For each case, I derived multiple observations by unraveling the empirical sequence of strategic decision making in a crisis. First, I examined whether Austria, or other relevant states, asked for loans from the Rothschild Bank. Then, I determined the Rothschild’s assessment of those loans and whether they are a function of the likelihood of war. I determined whether a loan was offered to Austria, and then assessed whether the Rothschild’s lending behavior affected whether there was war or not. If the Rothschild bank did have an effect, the analysis determines whether the effect followed a signaling mechanism or a constraining mechanism. Table 2 lists a summary of the cases.

Table 2. Austrian crises, 1821–66

The cases in Table 2 provide an interesting mix of crises that avoided war and crises that ultimately ended in war. In the cases that avoided war, there is support for this study’s hypothesis that finance’s effect on war onset operates through signaling, not constraining mechanisms. The cases the ended in war suggest further scope conditions under which the hypothesis is valid. The following sections provide more information on the cases, by focusing on within-case observational analysis. The CPO approach has two goals: (1) establish the plausibility of the hypothesis and (2) further refine the theoretical argument.

In sum, the crises that end short of war show ample evidence in support of this study’s theoretical expectations. The Rothschild’s operations in Europe helped European powers, most notably Austria, avoid continental war thanks to reduced information asymmetry between states. The cases that end in war highlight possible scope conditions, including the importance of leadership change in creating information problem. I examined these crises in more detail, starting with the cases that nearly end in war. Then I examined the three crises that do end in war.

Background: Austria and the Rothschild Bank

The Rothschild Bank facilitated loans to Austria for much of the early nineteenth century because the Rothschild family members were able to collect information about Austria’s willingness to meet its loan obligations. To acquire information about their sovereign clients, the Rothschilds spent a great deal of effort to develop relationships within the major political capitals in Europe. No relationship was as developed and as important as the Rothschilds’s relationship with Metternich, whom the Rothschilds referred to as “uncle,” both as a term of endearment and as a code name in correspondence (Cowles Reference Cowles1973: 83).

Metternich had incentives to freely provide information to the Rothschilds because it helped maintain Austria’s access to credit. The importance of this cheap credit cannot be exaggerated. Internationally, credit allowed Austria to maintain a foreign policy outside of its means. Domestically, credit helped Metternich isolate one of his main domestic rivals, finance minister Count Kolowrat (minister from 1826 to 1848). Kolowrat led an antiwar coalition within the Austrian elite, given his beliefs that war would have ruinous effects on the Austrian economy (Schroeder Reference Schroeder1994: 777). However, with a continued supply of inexpensive credit, Kolowrat was politically isolated, giving Metternich a free hand to administer foreign policy.

Metternich also benefited from a two-way exchange of information, taking advantage of the Rothschilds’s impressive communication network. During the early nineteenth century, the Rothschild Bank’s information acquisition efforts were supported by a network of couriers that attempted to not only outpace competitor investors but also diplomatic information services. The Rothschild Bank had offices in major cities across Europe (London, Paris, Frankfurt, Vienna, and Naples). Between these offices streamed a heavy volume of correspondence. They even developed a color-coded system to indicate the market news (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998).

The Rothschilds’s relationships with political leaders and their information network allowed the intermediary to effectively gauge states’ willingness and ability to repay its loans. During this time, Rothschild’s investments performed well (Flandreau and Flores Reference Flandreau and Flores2009). Gentz noted that the Rothschilds “are gifted with a remarkable instinct which leads them always to choose the right, and of two rights, the better” (Sweet Reference Sweet1941: 218). The Rothschilds strategically used this information to convince investors of these states’ creditworthiness, and they were fully aware that investors looked to the Rothschilds for cues in investments (Flandreau and Flores Reference Flandreau and Flores2009). The following analysis shows that states looked to the Rothschilds for cues as well, which affected the outcomes of interstate disputes.

1821–24 Austrian Intervention in Italy

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Rothschild Bank favored the Holy Alliance’s goals of containing France and limiting revolutionary measures to promote continental financial stability. The Holy Alliance’s ability to act against revolutionary sentiment required military intervention, which in turn required additional sovereign credit. The Rothschild Bank obliged, allowing Austria, and the rest of the Holy Alliance to effectively “police” Europe (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998: 127). The interventionist policing began in 1821, when Austria sought to strike down a revolution in Naples. The Rothschild Bank fully supported this intervention, as it reduced the revolutionary threat in Europe and increased the bank’s business with Austria. The intervention not only led to increased business with Austria, but it created a need for credit for Naples to stabilize its internal politics.Footnote 5 After the intervention, a formal loan was also set up with Austria.Footnote 6

Markets paid attention to the Rothschild dealings. The Rothschilds were careful about how they announced these deals to avoid speculation in the markets. The brothers would even restrict their travel. “Wherever we go now, people think it is a political trip,” Carl Rothschild exclaimed (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998: 139). But it was not only market actors who paid attention to Rothschild behavior. Jean-Baptiste de Villèle—prime minister of France at this time—noted that “The Rothschild courier is causing our bonds to rise again…. He is propagating the news that there will be no intervention” (Nichols Reference Nichols2012: 129). Both French and Austrian officials knew the power of Rothschilds’s couriers, as each government used this service to send news from the Verona Congress to their respective capitals, where the great powers were negotiating over intervention in Italy. Villèle’s close attention to the Rothschilds was not without criticism, as one French official observed, “Surrounded by gentlemen of the Bourse, whose stock-jobbing was deranged by the sound of cannon, [Villèle] was frightened by the cries of the ruin speculator” (ibid.: 129).

The Rothschild Bank’s enthusiasm to lend to Austria for these interventions was motivated by their belief that France and Britain would stay out of Italy. As a display of this confidence, the Bank launched part of the new Austrian loans in the French and London markets, along with the Austrian market. This type of financial transaction was unique at this time, and laid the foundation for Austrian finances to be more interdependent of Britain and France. In addition, it allowed the Rothschilds to sell shares to political figures in those countries (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998: 153). These transactions not only increased the Rothschilds’s confidence in France and Britain’s noninvolvement, but would also signal to Austria that the other great powers were not resolved to go to war.

The Rothschilds’s involvement in French and British politics also helped reduce the uncertainty of great power involvement. In Britain, Metternich formally appointed Nathan Rothschild as general consul representing the Austrian government. And while Nathan was criticized for being “indifferent” to his ceremonial duties, he had “done more than all his predecessors put together” in terms of extracting information (Corti Reference Corti1928b: 277–78). In reference to French Cabinet members, James Rothschild—who would also be bestowed a consul position with the Austrian government boasted: “I call on the king, whom I see whenever I wish, and I inform him of my observations. As he knows that I have a lot to lose, and that all I desire is peace, he has every confidence in me, listens to me and takes account of all that I say to him” (Lottman Reference Lottman1995: 26). When the Rothschilds passed information to leaders, they could credibly claim that their sources of information where at the highest levels of government. This prompted criticism, as illustrated by the newspaper Le Constitutionnel question of “By what right and under what pretext does this king of finance concern himself with our affairs?” (ibid.: 28). Whereas others saw the benefits of the Rothschilds involvement. Describing James Rothschild, the German writer Heinrich Heine noted that “[t]he prophets of the stock exchange, who know exactly how to decode the facial expressions of the great baron, assure us that the swallows of peace are nesting in his smile” (ibid.: 29).

Austria’s aggressiveness in Italy was bolstered by Rothschilds’s enthusiasm to lend. An Austria finance minister reported to Metternich that “even our financiers, led by Rothschild and Parish, are anxious to see our troops across the Po at the earliest possible moment, and marching on Naples” (Corti Reference Corti1928b: 229).

1830–39 Revolutions in Belgium and Italy

Initially, it appears that the Rothschilds’s fears about contagious revolutions came true in 1830 when revolutions in France, Belgium, Poland, and a number of Italian and German states erupted. Of all the revolutions, the two major events that threatened to escalate into a continental war were in Italy and Belgium. An important component of crisis bargaining was an open line of communication between France and the Holy Alliance, which the Rothschilds provided. Indeed, the Rothschilds’s role in these crises were so important that Metternich appointed James Rothschild as the representative of Austria’s position in Paris over his own ambassador (Corti Reference Corti1928b: 430). In addition, the Rothschilds’s enthusiasm to lend to all parties, including cash advances on loans, provided credibility to their signals that war was unlikely.

Belgium 1830–39

In 1830, revolutionary sentiment reached Brussels. The revolutionaries organized a national congress, put Leopold I into power, and declared its independence from Netherlands. European powers feared that France would attempt to intervene in Belgium to either reestablish a sphere of influence or more forcefully annex Belgium (Helmreich Reference Helmreich1976). In addition, members of the Holy Alliance had treaty obligations with the Netherlands, and may have been compelled to intervene to reestablish Dutch control. Prussia considered intervention to incite war with France, which appeared inevitable and had better-now-than-later incentives (Schroeder Reference Schroeder1994: 674–75). Austria and Russia appeared motivated to crush the Belgium revolt to deter revolutionary sentiment both at home and abroad. The regime change in also France in 1830 created uncertainty in Europe as to French intentions for Belgium.

Despite the uncertainty of intentions and resolve between great powers, the Rothschilds were able to ascertain states’ intentions and communicate these intentions between capitals. States again relied on the Rothschild courier network to rely messages to each other because this system was quicker than official diplomatic couriers and did not need to follow the same formal customs (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998: 232). James Rothschild’s roles as Austrian “ambassador” to France and Paris insider also helped facilitate information between capitals: “I am satisfied since I find ministers all for peace, and I hope that matters will come right. The king wants peace” (Corti Reference Corti1928a: 10). To James, it seemed unlikely that King Philippe of France would seek a war with the great powers after the king worked so hard to get the other powers to recognize him as a legitimate ruler (ibid.). With this perspective, James helped draft a crucial communique from France to Austria, outlining international arbitration over Belgium (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998: 238).

The Rothschilds walked a fine line of support for both sides of the conflict. The intermediary provided loans to the members of the Holy Alliance and France.Footnote 7 Austria received loans in 1830 (30 million gulden at 4 percent) and 1831 (36 million guldens at 5 percent, and covertly borrowed 20 million francs [ibid.: 250]). The French government borrowed 80 million francs in 1830 at 4 percent.Footnote 8 Most notable about the French loan was that ambassadors from Russia and Prussia “were personally interested in taking a share of the loan,” which demonstrated their confidence that the likelihood of war between the major powers was low (ibid.: 249). If these states did intend war, they would be forced to “turn to other bankers” (ibid.: 231). The Rothschilds also made loans directly to the Netherlands and Belgium.Footnote 9 Surprisingly, it was the French government, not the Rothschilds that warned that it would be “madness for us to give the Belgians money just at this moment and to giving them every facility in making war” (ibid.: 252). This did not deter the Rothschild Bank’s lending. Even when learning about military preparations in Brussels, James asserted that, “as long as the major powers are opposed to war, [Belgium] can’t do anything” (ibid.: 388–89). Salomon Rothschild vowed that Belgium “may count on [the Rothschilds] only as long as [Belgium] follows a policy of wisdom and moderation” (Corti Reference Corti1928b: 172). Once Belgium received its credit payments, the Rothschilds could do little to punish the state for violating its promise.Footnote 10 As James Rothschild astutely observed to his brother: “My dear Nathan, we do not have troops to force the government to do that which it does not want to do” (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998: 363). However, the Rothschilds information acquisition and ability to signal to great powers across Europe reassured them that peace would prevail.

Besides the Rothschilds’s access to the inner circle of the great powers, and its courier network to pass information along between states, the other evidence that suggests that leaders paid attention to the Rothschilds was the placement of certain officials in government. King Philippe’s first prime minister was Jacques Laffitte, who used bellicose rhetoric to adversaries abroad to placate revolutionaries at home. While the Rothschilds understood the political strategy to “keep the public mind occupied,” and communicated this to Metternich, they could not completely persuade the other capitals of France’s benign intent. James went to the French king, suggested to oust Laffitte for the more moderate Casimir Perier, which would assuage Austria and the rest of the Holy Alliance. The king accepted Laffitte resignation a week later (ibid.: 240).

Another important historical note is that in 1835, the Austrian emperor, Francis II died, creating unease across Europe. It was not initially clear if the succession would go smoothly, or if it did, what new policy directives would emerge. With reassurances from Metternich of stability, the Rothschild Bank actively supported Austrian securities in the Paris market, reassuring other states that the status quo would be maintained by the new Austrian regime (Corti Reference Corti1928a: 73–75). The Austrian ambassador to Paris praised the Rothschilds for their intervention in the market: “the attitude of the House [Rothschild] on this occasion … has contributed in no small measure to maintaining confidence among the public, and to checking ungrounded and unnecessary public panic” (quoted in ibid.: 75).

Italy 1830–32

After the revolts in Paris and Brussels, revolution appeared imminent in Italy after Pius VIII died in November 1830, weakening the papal regime’s ability to prevent a revolt (Schroeder Reference Schroeder1994: 691–99). The papacy lost control in the Italian territory Modena, and then called upon Austria to intervene. Unlike the intervention in 1821, it was more likely that France would offer resistance to Austrian intervention. France wanted to limit the influence of the Austrian intervention to allow for regime change in Italy or at least break Austria’s ties with the papacy. France mobilized 80,000 troops and warned both Vienna and the papacy against an intervention (ibid.: 693).

Despite the bluster from France, the Rothschilds did not appear worried about French intervention in Italy. James Rothschild wrote to his brothers that “even if Austria had intervened in the Modena affair, nothing would have happened, for it is realized that Austria would have been perfectly right in doing so, as [King Philippe] is too weak. No one wants anything but peace” (Corti Reference Corti1928a: 10–11). With the help of another loan from the Rothschilds, Austria sent forces to both Modena and Bolagna (ibid.: 15–16).

France made threats of retribution for Austria’s actions in Italy in 1830, but James Rothschild had developed a close enough relationship with French officials to view these threats as noncredible. Constant back channel communication between the two powers—facilitated by Salomon and James Rothschild in a similar way as the Belgium crisis—limited the risk of the continental war. James Rothschild was asked to craft messages and broker meetings between foreign dignitaries (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998: 236–37). For example, James would read Metternich’s messages to General Sebastiani, the French naval minister at that time. In response to one particular message in 1832, Sebastiani states that he “was pleased with everything I had heard from the good gentleman [Metternich]” and that “he had given orders in Italy to be accommodating to Austria in all matters” (Corti Reference Corti1928b: 406). With his relationship with France, James Rothschild could “regard the course of events [of 1830–32] much more calmly, according to all the information” despite the rumors of an impending war (Corti Reference Corti1928a: 29–30). James inferred the subsequent mobilization in France were more designed to “keep the country quiet than in order to make war” and relayed that message to Metternich (ibid.: 15).

The Rothschilds understood that the new French regime was attempting to find a peaceful solution while pandering to domestic interests sympathetic to the revolutions in Italy. Cognizant of this two-level problem, the Rothschilds constantly reminded Metternich of the new French regime’s perilous domestic situation. James Rothschild noted that the king favors peace, but if threatened “he would no longer be master of his house and the [French] people don’t want to be threatened like little children” and also stressed that the talk of war in France was designed to “keep the public mind occupied” (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998: 239).

After Austria occupied Bologna, the French government drafted the threat “evacuez immediatement.” The Rothschilds realized this message may provoke a escalatory response from Metternich and eventually convinced the French to remove that phrase from the correspondence to Austria (Corti Reference Corti1928a: 21–22). Instead, France conveyed, through the Rothschilds, that while it was upset with Austrian intervention in Modena, France would only become military involved if Austria entered Piedmont (an area considered a buffer between France and Austria), and did not make withdrawal from Italy a condition of peace for the Austrians (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998: 493). Metternich reassured France that Piedmont was not part of its strategy. Even after the French occupied the area of Arcana in February 1831, the risk of war remained relatively low as evidenced from the relatively calm credit markets (ibid.: 237). Metternich also followed the Rothschilds’s suggestion and publicly supported the Perier government in France.

1848–49 Austrian Intervention in Italy

Revolutions broke out again in Europe in 1848, including in Austria and France. Metternich was forced to flee Austria and Louis Napoleon Bonaparte (Napoleon III) took power in France. The postrevolution Austrian government appealed for a new loan from the Rothschilds in March 1848. Unable to adequately assess the risks of these new regimes, Anselm Rothschild dismissed the loan as “a great nonsense” and “a stupid project” (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998: 472). Even without a loan, Austria intervened in Italy, where revolutions were simmering. The Rothschilds also denied the French government a loan in April because it was unsure whether the loan would be used to intervene in Modena where Austria had again occupied. The Rothschilds were particularly worried that Napoleon III would follow the same expansionist foreign policy as his uncle. When Napoleon III was elected in December 1848, James Rothschild stated that what “interested us the most [is] whether we will have peace” in Italy (ibid.: 475).

France did intervene in Italy, but on the side of Austria and the papacy. This move helped reassure the Rothschilds that a great power war was not imminent. As Nat Rothschild noted, “when troops begin to move bondholders are frightened; in this case it is for the re-establishment of order, and I trust it will produce a good effect” (ibid.: 477). Soon afterward, the Rothschilds, assured that the risk of continental war was low because of the French–Austrian alliance, restarted loan negotiations with the Austrians. In September 1848, a 71 million gulden loan in treasury bills was issued. The Rothschilds were contracted to facilitate a loan for Piedmont, so that Austria would be paid an indemnity for its 1848 war. In addition, the Rothschilds approached the new French regime about the possibility of a new loan (ibid.: 475–77).

1850 German Confederation

In the wake of the 1848 Revolution, Prussia saw an opportunity to consolidate power over the other German states, and enacted the Erfurt Union. This union was designed to be a loose federation system, with Prussia acting as the epicenter. The union never came into fruition, as its development faced a quick response from Austria and Russia. Even France continued its support of the status quo, and threatened action against Prussia. Prussia subsequently abandoned the union and agreed to reinstate the German Confederation under Austria’s control (Taylor Reference Taylor2001: 101).

Given France’s support of Austria in Italy, the Rothschilds were confident that Austria’s demands on Prussia to abandon the Erfurt Union would not culminate in a continental war. As a result, the Rothschilds continued their financial dealings with both Austria and France during this time (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1998: 478).

Crimean War

Since the Napoleonic Wars, there were a number of crises that nearly transitioned to war. The following three crises all ended in war. The Crimean War was fought primarily between Russia on one side and Britain and France on the other, over the issues of Russian influence over the declining Ottoman Empire and access to the Black Sea. Although the Rothschild Bank relinquished some of it monopoly as a sovereign creditor after the 1848 revolutions, the intermediary remained important to governments’ war finance. For the Crimean War, the Rothschild Bank facilitated substantial loans to Britain, France, Austria, Prussia, and Turkey (Corti Reference Corti1928b; Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999) The Rothschilds once again believed that war was unlikely, as they believed that the unified front of Britain and France would deter Russia (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999: 70–72). However, without the close connection between the former Holy Alliance states, the Rothschilds were largely unaware of Russia’s intentions or resolve. When news of war broke out, it left the Rothschilds feeling “completely demoralized” (ibid.: 72).

The Rothschilds’s surprise at the beginning of the war was a result of the Rothschilds’s lack of network in Russia. Without inside information, the Rothschilds believed that Russia should have been deterred by Britain and France’s threats. Indeed, soon after fighting began, Russia made several concessions to its adversaries, but the fighting inexplicably continued (ibid.). If the Rothschilds had made more financial inroads in Russia, the bank may have credibly demonstrated France and Britain’s resolve.

Although Austria was not militarily involved in the Crimean War, it did mobilize for war to provide credibility to its diplomacy (Corti Reference Corti1928b). Austria’s military spending increased almost as much as France from 1852 to 1855 (42 percent increase for Austria compared to 53 percent increase for France) (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999). The Rothschilds issued an Austrian loan in 1852 (£3.5 million at 5 percent) to help support its expected military spending (Rothschild Archive 000/401B/11). During the war, Rothschilds, along with a consortium of other banks, issued an additional 34 million gulden loan (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999: 76). The Rothschilds’s lending appeared motivated by an attempt to stabilize Austrian finances and assurances that Austria would not fight (ibid.: 76). The return of Metternich to Vienna in 1851 as an advisor to Franz Josef helped assure the Rothschilds that Austria would not rush into war (Corti Reference Corti1928b).

1859 Italian Unification

Piedmont’s strategy for Italian unification started as early as 1856. Needing funds for mobilization, Piedmont’s Prime Minister Cavour requested a loan from the Rothschilds, but with the rationale that their rail system needed expansion. In a letter to the treasury secretary, Cavour warned that the loan cannot “give rise to the opinion that we require it in preparation for war…. If therefore you speak with Rothschild about any proposal for a loan avoid saying anything that might lead him to suppose that we are contemplating a terza riscossa [third resumption of war]” (Corti Reference Corti1928b: 343).

By the time Austria intervened in Italy again in April 1859, France was expected to intervene on the side of unification supporters. Prima facie, this should have deterred the Rothschild Bank in taking a vested interest in this conflict. Indeed, early warnings of French intervention in December 1858 caused a depression in rentes, the French debt security. This prompted Napoleon to claim that “I have not got the bourse [French financial market] behind me, but France is on my side” (ibid.: 347). James Rothschild made several attempts to ascertain from Napoleon III whether the government intended to support Piedmont if Austria intervened in Italian affairs again. While the French emperor made several personal assurances to James that France did not intend to interfere, public statements both in the press and during diplomatic events clouded assessments with regard to French intentions. At the same time, Napoleon made no objections when the Rothschilds informed him they intended to float another loan to Austria in 1859 (Corti Reference Corti1928a: 345–48).

There are several reasons why the Rothschilds may have expected France’s role in the war to be limited. First, Napoleon exaggerated the level of support of the French people. James Rothschild stated that “The Emperor does not know France. Twenty years ago a war might have been proclaimed without causing any great perturbation … but today everybody has his railway coupons or his three percents” (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999: 91). In other words, more people in France had a financial stake in peace in France.

There was also French resistance given that French geopolitical interests in Piedmont were unclear. France faced far more formidable threats from Prussia and Britain (Kennedy Reference Kennedy1987: 168). This may have led the Rothschilds to believe that even if France intervened, the war would be short. The Rothschilds ended up financing all sides of the conflict (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999: 99).

While the evidence regarding the Rothschilds’s expectations of French involvement is mixed, there is clearer evidence that the Rothschilds were ultimately surprised by Austrian actions. The Rothschilds believed that Austria would not initiate a war against Piedmont if Piedmont had French support (ibid.). Austria initiated conflict in April 1859, and war followed. Austria initiated the conflict with the belief that both Russia and Prussia would lend support. However, Russia was wary of engaging French forces so soon after the armistice of the Crimean War and Prussia wanted to see a weakened Austria to accelerate the unification of Germany (ibid.: 98–99).

This war did not lead to disaster for the Rothschild Bank as each of the three participants repaid their debt obligations. The lending business of both war preparation and postwar settlement, the Italian unification era were some the most profitable years in the history of the Rothschild Bank (ibid.: 93–94). However, this profit may be attributed more to luck than to smart investing. The Rothschilds’s difficulty in evaluating the geopolitical situation in 1859 can be attributed to increased competition in the lending markets, which temporarily lessened its influence in European capitals. In addition, other firms gained access to new communication technology. The telegraph and railroads allowed competitors to communicate across Europe in a manner that only the Rothschilds once could. James Rothschild protested that “the telegraph is ruining our business” (ibid.: 64). However, changing technology is not the entire explanation, as evidenced by the Rothschilds quick recovery in the market. The fortunate outcomes of its investments in 1859 helped reposition the Rothschilds on top of the world’s credit market in the 1860s. For example, in 1860, the Rothschilds showed their importance to international relations. New unrest emerged in Naples and Austria again mobilized to hold onto some influence in Italy. This new conflict risked not only France’s reinvolvement but also Britain’s (Corti Reference Corti1928a: 355). A Saxon foreign minister wrote to his counterpart in Austria, Count Rechberg, that the “great financiers of Paris and especially the Rothschilds, seem to be engineering a panic and are shrieking from the housetops that war between the two great sea Powers [Britain and France] is inevitable” (ibid.: 355).

At the same time, the Austrian government was negotiating a 25 million gulden loan with the Rothschilds. The Rothschilds lent their name to the new loan to provide support to this loan and existing Austrian securities, but the bank provided no capital to the endeavor. While the Rothschild involvement in a consortium of investors would provide some boost to the value of the loan, the Rothschilds refused to directly invest their capital to limit their risk exposure. In addition, the Rothschilds denied loans to the king in Naples (ibid.: 355–56). The risk that Austria would again face French resistance in Italy was too great for the Rothschilds. In the end, Austria stayed out and Naples was assimilated into the rest of unified Italy (ibid.: 358).

1864–66 End of Credit for Austria

When the Holstein Crisis emerged in 1864, the Rothschilds sought to sell its Austrian debt obligations off even though the Prussia–Austria alliance was expected to easily win its war against Denmark (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999: 129). Immediately after the war, the alliance dissolved because of disagreement over the ownership of the Holstein territory. In 1865, Austria requested a loan from the Rothschilds to begin new war preparations. Instead of lending to Austria, the Rothschilds preferred to lend to either Prussia or Italy to purchase Holstein or Venice, respectively, from Austria. The Prussian minister von der Goltz reported to King William that “the House of Rothschild is determined to bring its whole influence to bear to prevent Prussia from going to war” (Corti Reference Corti1928a: 371). Bismarck added that the Rothschilds had initially wanted to work with Prussia on a loan, but after discussions with the King William, changed their minds given their assessment of war (ibid.: 372).

After being rebuked by the Rothschild Bank, Austria attempted a mollified approach. In 1865, Prussia and Austria agreed to a temporary division of the Holstein territory (Moul Reference Moul2005: 156). Concurrently, Austria engaged in negotiations with Italy over control over Venice. Austria offered to cede Venice to France for no cost, who would then cede it to Italy. However, Italy wanted Venice directly ceded from Austria to increase the prestige involved in the transaction. Austria refused, as its leaders believed that this deal would deal a serious blow to the credibility of Austria (Morgan Reference Morgan1990: 328–29). The negotiation breakdown prompted Italy and Prussia to form an alliance, designed to attack Austria.

As war appeared likely in 1866, each of the participants approached the Rothschilds for loans. Each was eventually rebuffed. The Rothschilds, along with many other observers believed that Austria would win the war (Kennedy Reference Kennedy1987: 185). In regard to Italy, the Alphonse Rothschild articulated the relationship between lending and peace, “[A]s long as peace is not concluded, Italy cannot count on use for money; once peace is signed, then we shall see” (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999: 150).

The Rothschilds restricted their lending to Austria with the belief that its interventionist foreign policies would lead to war. James Rothschild summed up the intermediary’s thoughts on the war with this statement: “it is the principle of our house not to lend money for war; while it is not in our power to prevent war, we at least want to retain the conviction that we have not contributed to it” (ibid.: 91).

Understanding the importance of finance, Bismarck paid close attention to the financial situation in Austria. This was evidenced by Bismarck promoting a Rothschild agent, Gerson Bleichroder, as a key confidant on foreign affairs (Stern Reference Stern1977: 17, 21–29). Just as Metternich called on the Rothschilds to act as ambassadors during the 1830’s crises, Bleichroder would help Bismarck directly tap into the Rothschilds’s information network (ibid.: 27). Although Bleichroder and the Rothschilds’s utility was more of a function of profits than Prussia’s national success, Bismarck realized that the Rothschilds played a key role in the outcome of the crisis. For example, knowing that Bleichroder would report to the Rothschilds on any new development, Bismarck thought it best to “advise [the Rothschilds] early and often that Prussia intended to exploit Austrian weakness for the sake of its own greatness” (ibid.: 35). Bismarck hoped that this would discourage a Rothschild loan to Austria and also fully inform Austria and France of Prussia’s intentions (ibid.: 37, 60).

Bismarck knew that Austria’s inability to secure a loan would signal a lack of support in the capitals of Paris and London. In a diplomatic report, Bismarck underlined a quote from an Austrian official that stated that “because of its lack of credit the Austrian government would temporarily have to give up its great power position” (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999: 135). Of course, Prussia also had to worry about its own finances. Bismarck was dismayed that Prussia had to “postpone making full preparations for war in order first to carry through the financial operations…. It is in the nature of things that the House [Rothschild] should not welcome the possibility of war” (ibid.: 140). While the Rothschilds had preliminary negotiations with Prussia regarding a loan, they backed out when the Prussian ambassador to France confirmed Bleichroder’s reports to James Rothschild that Prussia was preparing for war (ibid.: 139–40).

Austria and Prussia’s inability to secure a loan from the Rothschild Bank should have signaled Prussia’s resolve to Austria and viceversa. Bismarck was so confident that Austria would be deterred by Prussia that he ordered his banker not to sell any foreign securities “because of some premature fear of war” (Stern Reference Stern1977: 65). However, Austria was bolstered by a neutrality pact it had signed with France. In addition, Austria eventually secured a loan in Paris with the help of the French government and without Rothschild support, and immediately became less interested in selling Holstein (ibid.: 68). While Austria welcomed the loan, it realized that without the Rothschilds’s involvement that the loan did not have the same international effect. The loan that Austria secured provided better terms than the stringent terms offered by James Rothschild. However, the Austrian ambassador to Paris, Mulinen, summarized the reasons why Austria would consider a worse deal: the alternative financiers did “not have the prestige of Rothschild-Baring” (Steefel Reference Steefel1936: 34). In another letter Mulinen noted that the Finance Minister “Baron Becke is of the opinion that our financial fate is in [Rothschild’s] hands and that if we don’t succeed with him, we won’t accomplish anything of consequence with the others. We must, then, make the sparks fly and, especially, flatter old man James” (ibid.: 30).

France helped Austria with a non-Rothschild loan, hoping that Austria would provoke a war with Prussia, leaving one of the French adversaries weakened (Steefel Reference Steefel1936). At the least, the result of the loan increased Austrian expectations that France would provide defensive assistance (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999: 138). France provided no assistance. Austria was defeated and subsequently isolated from Western Europe. The Rothschilds limited their losses by selling Austrian securities before the war and took satisfaction that Austria was “forced to admit that the House of Rothschild, especially its eldest representative, James in Paris, had been proven right in their warnings against going to war” (Corti Reference Corti1928a: 375). Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph later called Austria’s decision “very honorable, but very stupid” (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999: 138).

Discussion and Conclusion

The preceding analysis focused on investors’ assessments of risks of major power war and whether these assessments had any impact on the emergence of war. The preceding analysis finds that, in all cases, the Rothschild Bank’s lending behavior was a function of their assessments of great power activities. In most cases, the Rothschilds’s assessments signaled to the great powers about the intentions of other states. The strength of the signaling effects varied across crises: high in 1820–30, lower in the 1850s. In the crises that stayed short of war, the Rothschild Bank’s signaling proved useful in creating shared assessments about intentions and resolve between powers. Great powers were able to navigate through several interstate crises without dragging the whole continent into war. The signaling dynamics generated from Rothschild lending before 1848 helped Europe stay out of war.

The cases that did end in war offer insights that should help refine the theoretical expectations of this study. For example, the Crimean War is consistent with the general theory here, but suggests important scope conditions. For example, the financial power of France and Britain, coupled with their credible central banks, may have dampened the signaling power of finance. Despite the risk of war, the Rothschild Bank was still willing to lend to these states given the high likelihood of repayment. However, finance still evaluates the expected return of investments to states as a function of the risk of war even in the richest, most creditworthy states. The onset of the Crimean War reduced the value of British and French bonds by 15 percent (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999: 72). More recently, the 2003 Iraq War negatively impacted US treasury bills (Rigobon and Sack Reference Rigobon and Sack2005). So while finance may still lend to a small number of select states at risk of war, finance’s behavior may still offer signals. The analysis suggests the need to examine other types of lending behavior besides the admittedly simple dichotomy of lending/no lending. For example, lenders may still be willing to lend a state about to go to war if that state has a central bank, but the lender may seek ways to offset the risk of lending. This may result in higher interest rates on loans offered. Alternatively, the Rothschild Bank sought to bring in other banks on some loans to spread out risk.

The question remains as to why Russia did not completely decipher the importance of the Rothschild’s signals before the Crimean War. For one, the Rothschilds were never able to extend their influence and information network into Russia. This was not an issue for the Rothschilds in previous crises given the solidarity of the Holy Alliance before 1848. Before that date, the Rothschilds simply looked to Austria for information on Russia’s intentions and resolve. When Metternich was ousted from Austria, the Holy Alliance weakened, the Rothschilds were effectively blind to Russia’s intentions, specifically related to the Ottoman Empire. This suggests that the importance of alliances as conduits of information from finance and how finance’s role war can be limited when alliances fall apart. Future research should consider how finance and alliances intertwine.

The war in 1859, along with the crises in 1848–49, also prove informative for identifying scope conditions. Before 1848, the Rothschilds carefully cultivated their relationships in these great powers to gain access to the main conduits of information. Sudden changes in leadership in these regimes left the Rothschilds in the proverbial dark after the revolutions in 1848. Over time the Rothschilds regained their positions of influence in these regimes and found themselves in the center of the subsequent crises. The case analysis was partially designed to allow for theoretical refinement. The 1848–49 and 1859 cases suggest that future exploration of finance’s signaling role in interstate crisis bargaining should consider leadership change as an important scope condition.

The signaling role of prestigious financial intermediaries in interstate crises does not necessarily refute or undermine all previous arguments that connect finance to war. For example, the Rothschilds operated in a Europe that was not quite financially interdependent, and thus theories of financial interdependence and conflict should not apply in these cases (Gartzke et al. Reference Gartzke, Li and Boehmer2001). It is interesting to note that the Rothschilds took steps to increase financial interdependence across. The bank subscribed Austrian loans in Paris and London to not only increase the pool of potential subscribers but also to offer favorable bond purchases to important political leaders in those capitals. The Rothschilds recognized the importance of independence for not only minimizing risk of securities but also for great power politics. Future research should focus more on the role of nonstate financial actors’ role in interdependence’s effect on war.

This study demonstrates that investors’ effect on international crises involve signaling dynamics. The case analysis showed several instances where the European powers, most notably Austria, avoided continental war thanks to reduced information asymmetry between states. The preceding argument and analysis explores an intricate intersection of security and international finance issues. The actions and strategies of states had a tremendous effect on investors well-being, evidenced by the reaction of markets to the news of war (Chadefaux Reference Chadefaux2017). Conversely, states were not directly affected by the actions and strategies of investors, but only through the signals lenders offered. Even the Rothschild Bank, the most dominant lender in the nineteenth century, could not directly constrain European powers from pursuing military strategies. The Rothschilds were aware of their limitations and instead focused on their advantages: information acquisition and dissemination. The Rothschilds use of information and signaling helped inform states of their adversaries’ intentions and resolve, which provided stability in Europe for much of the nineteenth century. This finding shows that the signaling aspect of investors’ behavior greatly affected state behavior.

This article offers an alternative theoretical explanation to the Hundred Years Peace. However, the signaling theory should have broader implications on current international relations issues. Some actors have such a dominant position in the current sovereign credit market that their behavior not only signals to other investors but should inform states as well. For example, during a rather tense crisis between North and South Korea in December 2010, Standard and Poor’s (S&P’s) declared that tensions would not likely end in war, and as a result, South Korea’s credit rating would remain the same. However, S&P’s warned that any military escalation on the Korean peninsula would result in a drastic credit downgrade from the rating agency. With this announcement, stability returned to the South Korean bond market after weeks of anxiety, and bond prices returned to normal levels (Macfie Reference Macfie2010; Yoon Reference Yoon2010).

The audience of S&P’s declaration is not limited to bond market investors. Instead, the credit rating agency’s assessment of conflict risk on the Korean peninsula informs states as well. S&P’s assessment of conflict risk provided states shared expectations about the risk of conflict and made it easier to avoid unnecessary military tension. Given that sovereign credit comprises 20 percent of the global financial asset (Tomz and Wright Reference Tomz and Wright2013), further research should focus on finance’s signaling dynamics in international relations.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Matt DiGiuseppe, Bob Kaufman, Jack Levy, Pat McDonald, Paul Poast, Scott Wolford, and participants at the Texas Triangle International Relations conference and the American Political Science Association annual meeting for their valuable feedback.