The general theme of the 2021 conference is ‘Building Bridges’, and it certainly seems to me an important value in academic life to try to reach across the boundaries of our disciplines. I want, here, to offer an example of this kind of reaching across. Specifically, I want to consider a historical example of an attempt to build a bridge from art to philosophy by way of using visual metaphors to express philosophical arguments.

This aspiration was first widely popularized by the humanists of Renaissance Europe, who took the idea from the rhetorical theorists of classical antiquity, and especially from Cicero and Quintilian. They had suggested that, if you wish to convey an argument with maximum persuasive force, what you need to do (I quote Quintilian) is to learn to speak and write with so much vividness that ‘you not only say what is true but in a certain sense reveal it to the sight’. You need, in other words, to find some means of helping your audience literally to see the point.

But how can you hope to do that? This is where the classical rhetoricians introduced the so-called figures and tropes of speech, especially the master tropes of simile and metaphor. We still speak in English of these figures of speech as imagery, the implication being that they are forms of language which make you see things. A further proposal was subsequently put forward by the rhetoricians of the Renaissance. They maintained that the most potent means of getting an audience to see what you are arguing is to offer them not merely verbal but actual images. You need, that is, to provide illustrations of your argument, presenting it not as a written or spoken text but rather in the form of a picture. This suggestion likewise left an imprint on the English language. We still refer to illustrations inserted into texts as figures, just as I have done in this text.

As these ideas were increasingly pursued, they gave rise to two major developments in the earliest age of the printed book in Europe. One was the creation of the hugely popular genre known as emblem books, of which countless were published from the mid-sixteenth century onwards, first in Italy, then in the Netherlands, then everywhere. These were works of moral theory and religious instruction in which some edifying lesson, usually written in verse, was placed on one side of a page, while a picture of the lesson to be learned appeared opposite.

The other development was the inclusion in printed books of what came to be called frontispieces. This was originally an architectural term used to refer to the decorated entrance to a building, but in the late sixteenth century the word also began to be used to describe the entrance to a book in the sense of being an introduction to its argument. What enabled this development in book production was the new technology of etching and engraving, which allowed highly detailed images to be produced on a small scale. But what encouraged this innovation was the cultural imperative to get people to see what you want them to believe.

One of the pioneers in this use of art to write philosophy was Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes published two major treatises on political philosophy, his De cive of 1642 and his Leviathan of 1651, both of which he wrote in Paris while in exile from the English civil wars. Each is prefaced by a complex iconographical frontispiece, and it is on these that I now wish to concentrate, using them as a key to try to unlock Hobbes’s theory of the state.

Figure 1, first of all, shows the frontispiece of Hobbes’s De cive. This was the work of Jean Matheus, the printer of the book. You might wonder, however, if there is any reason to suppose that Hobbes was involved in, or even approved of, this attempt to portray his argument. The answer is I think that he must have been deeply involved. Figure 2 shows the frontispiece of the manuscript copy of De cive that Hobbes presented to his patron, the earl of Devonshire, in 1641, some months in advance of its printing, and as you can see it is the same design. But surely Hobbes would hardly have offered it to his patron if he did not approve of it himself.

Figure 1. Frontispiece of Hobbes’s De cive (as printed in 1642).

Figure 2. Frontispiece of Hobbes’s De cive (manuscript copy 1641).

Let me return from this pen drawing to the published etching of 1642. As you can see, it is organized around a portrayal of the normative as well as the spatial sense of standing above or being under someone else. The image is divided by an entablature on which the word Religio is emblazoned. All human life, the frontispiece is telling us, takes place under religion, and we need to remember that our conduct will eventually be judged by the heavenly figures who stand above.

As well as focusing on above and below, the design is also preoccupied with the idea of sides, and especially with the rhetorical claim that in politics there will always be two sides to the question. To the left and right we see two figures representing opposed points of view. The question at issue between them is the one that Hobbes regards as central to political philosophy. Should we subject ourselves to Imperium, political power, or should we insist on living a life of Libertas, personal freedom?

What if we choose subjection to supreme power? We are shown that we can hope for a life based on justice. The figure marked Imperium is presented as a sovereign wearing a closed imperial crown, holding the sword of penal justice in her left hand while carrying the scales of distributive justice in her right. We also learn that, if we assign the power to wield the sword to such a ruler, we can hope to gain security and prosperity, the kind of life illustrated in the landscape within which the figure of Imperium is placed. In the background we see a sunlit city on a hill, while in the foreground men with scythes peacefully harvest the fruitful fields.

What if we instead choose Libertas? If we turn with that question in mind to the Renaissance emblem-books I have mentioned, we usually find the condition of personal freedom celebrated as obviously the best form of life. Figure 3, for example, shows the happy and smiling image of Libertà from Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia of 1611. She holds a sceptre to show that freedom should rule. Her pilleus or cap of liberty signifies her independence from servitude. Her flowing garments emphasize her freedom of movement. And she is shown together with a cat. The accompanying verse reminds us that cats love liberty; they show us the value of going one’s own way.

Figure 3. Libertà from Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (1611).

Hobbes’s frontispiece, by contrast, displays liberty as an unwanted and burdensome state. This was, I think, iconographically unprecedented. We are warned that, if we choose not to submit to a sovereign who can offer us protection, we shall have to stand ready to protect ourselves. So the hunched and frowning figure of Libertas is shown in a posture of self-defence, a bow in her left hand and an arrow in her right. Gone is any connection between the possession of liberty and the enjoyment of happiness.

To live in liberty, the image additionally warns us, is to commit ourselves to what Hobbes regarded as a primitive as well as a dangerous way of life. We need to recall that this was the generation in which Europeans for the first time saw images of native American peoples. Figure 4, for example, shows one of Theodore de Bry’s illustrations for Thomas Hariot’s Report on the new found land of Virginia, published in 1590, showing the earliest portrayal for Europeans of a native American chief. We see him front and back, standing in a fanciful landscape in which four hunters with bows and arrows are shooting at a stag. The frontispiece of De cive copies several features of de Bry’s landscape, but at the same time transforms it into something much more sinister. Again we see four hunters, three similarly armed with bows and arrows. But in this case they are shooting at two fellow human beings who are running for their lives, while a fourth stands ready to strike them down with a club.

Figure 4. Illustration by Theodore de Bry for Thomas Hariot’s Report on the new found land of Virginia (1590).

As I began by saying, the idea of a frontispiece is that it offers a visual summary of the book you are about to read. So what summary is Hobbes offering us here? It is, surely, that although a life of liberty may seem instantly appealing, you would be very unwise to choose it. Submission to supreme authority may not be your intuition, but is nevertheless in your best interests.

After Hobbes published De cive, he returned to his scientific interests, and especially to his attempt to produce a purely materialist theory of mind and the world. But, in 1649, when he was still in exile in Paris, the English brought to an end their civil war by executing their king and declaring England a republic. Hobbes felt an urgent need to comment on these revolutionary developments, and he turned at once to write Leviathan, which he published a year before he finally decided to go back home.

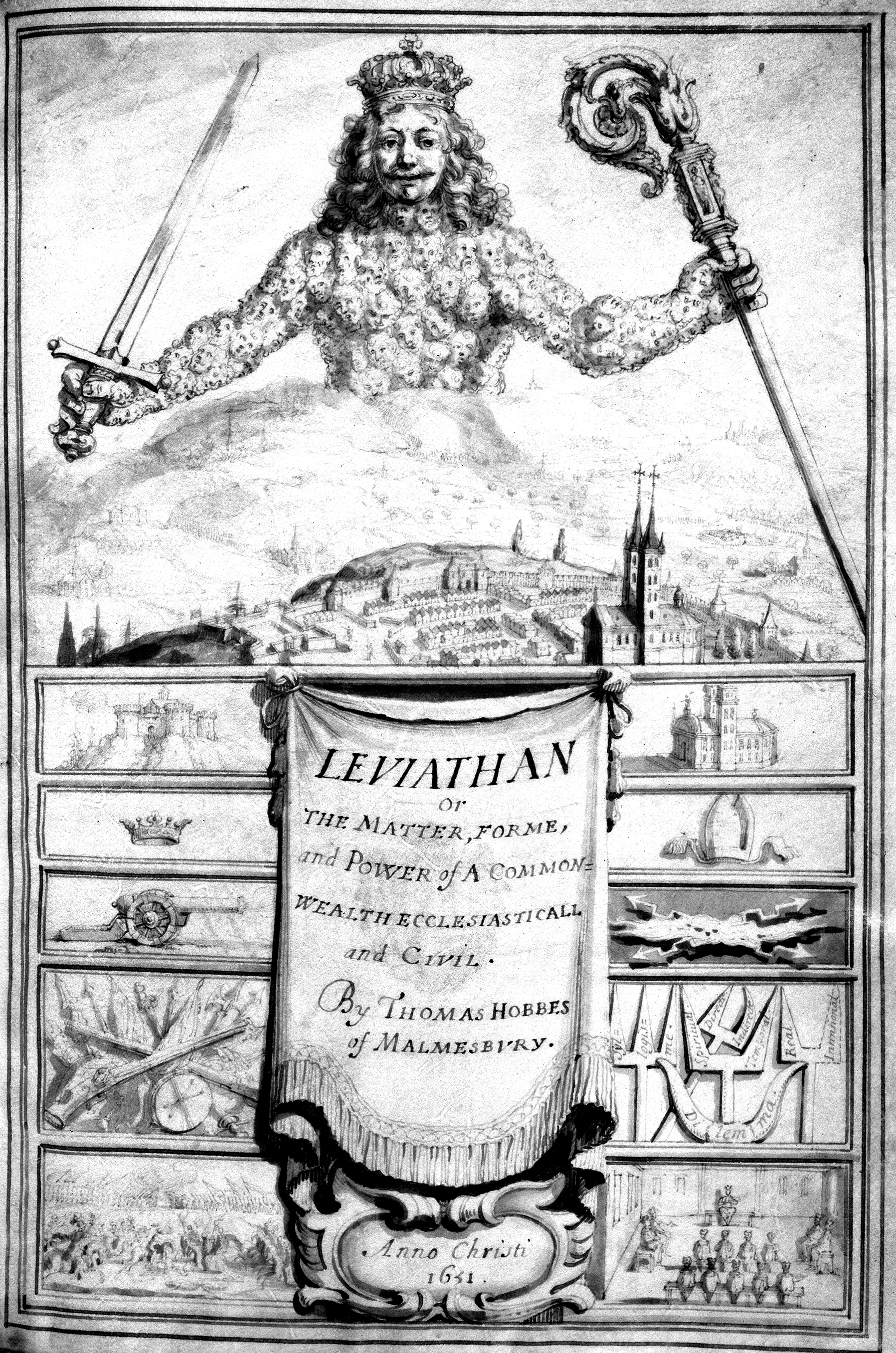

As shown in Figure 5, Hobbes again offers us a frontispiece summarizing the argument of his book. This is a folio-sized etching, the work of Abraham Bosse, one of the leading French engravers of the time. Let me first underline that, as in the case of De cive, Hobbes must certainly have given his approval to this design. In Figure 6 we see the frontispiece of the unique manuscript of Leviathan, now in the British Library, which Hobbes presented in 1650 to the future King Charles II, who had by then arrived in Paris in exile from the republic in England. As you can see, this is basically the same design as the published one. But Hobbes would hardly have offered his future sovereign an image of which he did not approve, so I think we can safely conclude that he endorsed the published version, and probably had a hand in creating it.

Figure 5. Frontispiece of Hobbes’s Leviathan by Abraham Bosse (as printed in 1651).

Figure 6. Frontispiece of Hobbes’s Leviathan (manuscript 1650).

I now want to focus on this version, and at the same time on the contexts within which we need to place it if we are to make sense of what we see. One of these contexts is supplied by Hobbes’s earlier frontispiece for De cive, and here what strikes me most of all is his complete repudiation of so much of his earlier visual argument.

It is true that both frontispieces display a representation of supreme political power. But one change is that the representations are differently gendered. In De cive we see supreme power or Imperium as female, no doubt to maintain symmetry with Libertas, who needs to be female because in Latin the word is feminine in gender. By contrast, the head of the colossus in the frontispiece of Leviathan, with his moustache and beard, is emphatically male. A further and crucial change is that in De cive it was important that there are two sides to the question: subjection or liberty. But in the Leviathan frontispiece this dialogical way of thinking has been entirely given up. We are now being shown that there is no alternative but to submit to government.

A yet more dramatic change relates to the place in Hobbes’s argument of the Christian religion, and especially the Christian church. In the De cive frontispiece, the idea of a Day of Judgement dominates the whole of human life. But here it has disappeared without trace. No one stands above the head of state, and the verse quoted from the book of Job at the top of the frontispiece confirms that ‘there is no power over the earth that can be compared with him’. The world of politics has been wholly secularized.

Recall too that in the De cive frontispiece the figure of Imperium holds only the symbols of civil power – the sword and the scales of justice. But here the head of state holds not only a sword but at the same time a crozier or pastoral staff, a symbol of ecclesiastical power. We are now being told that there is no such thing as ecclesiastical power as opposed to pastorship. Power is shown as political by definition. We are looking, in short, at an image of the modern idea of the secular state.

I next want to consider the broader visual context that the genre of emblematic frontispieces may be said to provide. One strong convention was that of showing the titles of books as being worthy of protection and support. These supporters were usually portrayed as military figures, often placed next to classical pillars to remind us that they are pillars of strength. Almost invariably they were also shown – in a further visual metaphor – as standing by the title of the book, reminding us that to ‘stand by’ someone means to offer them loyal and protective support.

Figure 7 shows an illustration I have taken more or less at random from a large number of possible examples. We see the frontispiece of George Chapman’s translation of Homer’s Iliad, first published in 1611. Here we return to the idea that in war as in politics there will always be two sides to the question. The rival heroes, Hector and Achilles, both stand next to classical pillars, and are armed and opposed to one another. But at the same time the visual metaphors tell us that they are pillars of strength who are standing by the title and guarding it. Although they are opposed to one another, they are both supporters of the book.

Figure 7. Frontispiece of George Chapman’s translation of Homer’s Iliad (1611).

Let us see what happens to this convention in the Leviathan frontispiece. If we focus on the lower half of the image we again encounter two pillars, each of which takes the form of a sequence of framed pictures. But where we would expect to be shown figures supporting the title, what we see are the deadliest enemies of stable government. On the right we are shown the divisive power of the Church, represented at the top by a Cathedral and a bishop’s mitre. Underneath we see the thunderbolt of excommunication, and below it the sharp and deadly weapons of syllogistic logic. At the base of the pillar, in another crucial visual metaphor, we see the lowest depths to which the Church can bring society – the usurpation of sovereignty by an ecclesiastical court. On the left we are shown the equally divisive power of faction, beginning at the top with the castle and coronet of an overmighty aristocrat (paralleling the overmighty leaders of the Church). Underneath, we see a cannon ready to blow up the commonwealth (paralleling the thunderbolt of excommunication). We also see a bundle of sharp and deadly military weapons, as well as the lowest depths to which the state can be brought by faction – two armies colliding in civil war.

How can we hope to deal with such dangerous enemies? The answer generally given by the political writers of the age was that, in a much-used phrase, they must at all costs be kept under. And this is precisely what we are shown in a further visual metaphor. The forces of disorder will always be there. But so long as there is a single bearer of power, we can hope that these forces can be prevented from destabilizing the peace. If the sovereign alone wields the sword, the forces of faction can be kept under the surface of everyday life. And if the sovereign at the same time holds the crozier, the Church can be similarly brought under the control of the state.

I want to end by returning to the dominating figure of the colossus in the upper half of the frontispiece. Who or what are we looking at? He has usually been identified as a sovereign or king. But, in Hobbes’s political theory, sovereigns are natural persons, men or women, and what we see here is not a natural person at all. Rather we see a multitude of individuals who have come together as a single body – a body politic – by way of subjecting themselves to a single head – a head of state. What we are looking at is Hobbes’s attempt to render visual the abstract idea of the sovereign state.

Finally, if we look more closely we find that Hobbes is also telling us what attitude we should adopt towards sovereign power, and here he offers us an image that seems to me of enduring moral significance. On the one hand, sovereign power keeps the peace, and is therefore entitled to respect. So the people are shown, in a further visual metaphor, looking up to their head of state. On the other hand, we are shown that sovereigns are emphatically not entitled to reverence, as would commonly have been assumed in Hobbes’s time. If this were so, the first act you would need to perform in the presence of your sovereign would be to remove your hat. But not a single person here has done so.

Furthermore, as the frontispiece also shows, it is we who create the state. It consists of nothing other than us, the body of the people, united under an agreed executive head. And notice that by the body of the people Hobbes means everyone. It is usually said that only men are portrayed, but if you look more closely you can see that many women are present, most of them wearing bonnets, and some of them accompanied by children. So if, for any reason, we, the people, cease to support the state – if we decide to walk away – what will be left? Nothing but a severed head, as had just happened in Britain.

Hobbes’s final message seems to me to be directed at those who, for the time being, have been granted authority to use the power of the state. They are nothing more than our authorized agents, whom we have agreed to support. They must therefore take care to govern for the good of everyone. They need to remember that their power has been given to them by us all, and that we retain the power to walk away.

About the Author

Quentin Skinner has been Barber Beaumont Professor of the Humanities at Queen Mary University of London since 2008. Previously he taught at the University of Cambridge. He was first appointed there in 1965, and was Professor of Political Science from 1979 to 1996 and Regius Professor of History from 1996 to 2008.