An Overview

Mothers are instrumentalized as vehicles for “lifestyle”-oriented health-promotion messages, while simultaneously they are made invisible as persons and agents by these messages. This includes cisgendered, reproductively able females, and people who are other than cisgendered, reproductively able females and are mothers. “Mother” is therefore not defined biologically in this article, but as a familial and social role. I focus here on two problematic aspects of health-promotion materials regarding feeding the children of Britain. The first is that health-promotion campaigns around “lifestyle” issues dehumanize mothers with their imagery or text, which stems from the ongoing undervaluing and objectification of mothers and women. Campaigns use imagery that is symptomatic of the chronic sexualization of women in typically nonsexual contexts (for example, feeding one's children). This sexualization serves to objectify mothers qua women, to exclude mothers who do not fit the mold depicted in the imagery, and to remove mothers generally from the position of agential interlocutor. Mothers are sexualized in these messages to the detriment of the goal of health promotion, which in this case may be to change something about mothers’ knowledge or behavior regarding feeding their children. The second, however, is that these campaigns place unjustified demands on mothers, which stem from a misinterpretation of the maternal duty to benefit. The demandingness of the recommendations from public health-promotion campaigns goes well beyond what this maternal duty requires.

To support these claims, I begin with an analysis of some recent or ongoing campaigns from Great Britain. Mothers are frequently the target of “lifestyle”-focused messages (and in this article, those related to childhood obesity). This is partly due to the normative values and ideas contained in the concept “mother,” including assumptions about gender roles within families, and to an understanding of the nature of maternal duty. The idea of “mother” projected in health-promotion campaigns is very limited—usually presented in stereotypical ways as heterosexual and cisgendered, and predominantly white and middle-class. This means two things. First, in campaign imagery, others who claim the role “mother,” including Black and Minority Ethic women, lower-income women, lesbians, men, trans-women, and grandparents, are rarely if ever represented.Footnote 1 Mothers are seldom pictured as complete individuals. Rather, when pictured, it is as a fragment of a female body, from neck to waist, with the emphasis on breasts. This has political implications for the visibility and recognition of the many people who are mothers but do not fit this imagery. Second, for those mothers who do match with some of the identifying traits (who are white, heterosexual, or cisgendered women, for example), the imagery is objectifying and enclosing. In both cases, mothers are not treated as active participants in a discussion about healthy habits; the exclusionary, enclosing, objectifying, and stereotyping imagery renders them inert within the campaign (though they may react strongly online or elsewhere).Footnote 2 In addition to being represented by parts of a female body, mothers are sometimes spoken to in the first person in these campaigns, but frequently spoken about in the third person (for example, “Mum's milk is best for baby”). These features indicate that mothers are not treated as interlocutors within health-promotion messages, but rather are treated as recipients of (being told) or as a medium for (passing on) instructions.

Following this analysis, I will provide a brief discussion of “lifestyle drift” in British health promotion, which moves responsibility from relatively powerful collective agents (government, corporations) to individuals or to groups that are relatively disempowered. In shifting responsibility thus, specific causal stories are required about health states or behaviors to support the move from an empowered agent to a (contextually) disempowered agent. This is followed by an analysis of maternal duty. Following Fiona Woollard and Lindsey Porter, I argue that mothers have a general duty to benefit, which takes the form of a hypothetical imperative, rather than a specific duty to do each act that appears beneficial for their child (Woollard and Porter Reference Woollard and Porter2017). These arguments support shifting the focus of responsibility for so-called lifestyle issues away from mothers and back toward policymakers. Moral demands that are too high for mothers, which go beyond their general duty to benefit, may be met by systemic or policy-level changes. To the extent that we think that there is a countervailing governmental duty to ensure certain features of food (and other) systems via regulations and policies, there may be a requirement upon governments to provide less tokenistic measures toward achieving good childhood nutrition than producing campaigns.

The British Context

First, readers may be interested in why I am discussing mothers and not “parents.” In Britain, mothers are the de facto primary feeders of their families, and as such, are widely considered to hold primary responsibility for feeding choices and behaviors. Further, as Quill Kukla (writing as Rebecca Kukla) writes,

Although we rarely make this role explicit, mothers serve as a crucial layer in [the health-care] system. For instance, as a culture, we take mothers to be primarily responsible for nutrition, basic care, fostering appropriate self-care practices, protecting children from the risks and harms of daily life, and organizing and sustaining appropriate contact with more formal medical institutions, through keeping children vaccinated, arranging for timely checkups, and judging when a visit to the doctor or emergency room is necessary. (Kukla Reference Kukla2006, 157)

Despite some progress in equalizing child-care responsibilities between mothers and fathers, mothers are still most frequently responsible for the lion's share of childcare responsibilities, and especially feeding. This reflects normative and gendered assumptions about mothers’ roles within the family and in society. Mothers are still expected to be the primary care-providers for children, and mothers’ undervalued and underrecognized affective labor continues to be exploited.

Rates of breastfeeding among British mothers is relatively low, with only 36% breastfeeding at six months, as compared to 49% in the US and 71% in Norway (PHE and Unicef UK, 2015). There are many reasons for this, including type of employment and workplace practices, cultural acceptability of breastfeeding in public and within families, and attitudes toward formula-feeding (PHE and Unicef UK, 2015). Research from England indicates that the group least likely to initiate or continue to breastfeed past six weeks is young mothers who are white, less-educated, and living in disadvantaged communities outside of London; older mothers, Black and minority mothers, those who are better educated, and those who live in more prosperous communities or in London are more likely to initiate and maintain breastfeeding (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Rosemary Tate and Dezateux2005; Oakley et al. Reference Oakley, Renfrew, Kurinczuk and Quigley2013). In Britain, similar social factors are relevant to rates of obesity. That is, children and women who are from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, who live in less well-off communities, and who are less educated are more likely to be overweight or obese (PHE 2018a).

These contextual factors have affected the aim and direction of PHE and National Health Service (NHS) campaigns around breastfeeding, and childhood obesity generally. The combination of such demographic data with sociocultural expectations of mothers are, unsurprisingly, reflected in health-promotion campaigns. In childhood obesity messages, it is consistently “mom” who is referred to or targeted in relation to food and feeding. In the academic literature around childhood eating habits and body weight, it is nearly always mothers who are interviewed and studied, and this is true even when the title of the study says “parents” (see Clark et al. Reference Clark, Goyder, Bissell, Blank and Peters2007). Mothers appear to be the main decision-makers about and responsible parties for food shopping, cooking, and packing lunches. So, interestingly, many studies that set out in principle to consider “parents” ultimately focus almost exclusively on mothers. This research phenomenon is likely connected to the reality of childcare imbalances within heterosexual partnerships, as well as gendered assumptions about care and maternal nature that serve to maintain those imbalances.

Invisible Instruments

Consider, then, the ways in which health-promotion campaigns from PHE and the NHS approach mothers about feeding their children. As we will see, in campaigns about childhood obesity, mothers are seldom respectfully addressed as equals to the speaker, nor as agents, and sometimes represent only the oblique targets of a campaign. A variety of nonpropositional content is conveyed in these health-promotion campaigns, including particular judgments regarding (good) motherhood, values around food, gender, and family, and body image or beauty ideals for women. Although presumably having a health intent, some of these campaigns and their judgments do not have a clear or primary health message. Campaigns may be intended to respond to demographic information about who in Britain breastfeeds and who is less likely to, but the campaign messages created end up reinforcing stereotypes of various kinds, as I will discuss, and excluding and enclosing mothers generally within limited images of who are mothers.

To begin, the Change4Life/Start4Life campaign series in Britain has been running long enough to have had multiple campaign iterations and to have honed their target audience. They currently aim to target behavior change by providing parents (mothers) with information. From their website: “We know that what happens during the first few years of life (starting in the womb) has lifelong effects on many aspects of health and wellbeing—from obesity, heart disease and mental wellbeing, to educational achievement and economic status. We also know that parental behaviors impact heavily on their child's behaviors. Parents’ health can act as an enabler or barrier to nurturing their children's development” (PHE n.d.). In many iterations of the Change4Life campaigns, children were the initial target audience of the videos and other materials. This child-centric approach was meant to encourage children to pressure their mothers to change family behaviors (O'Reilly Reference O'Reilly2016, 7).Footnote 3 However, this approach via the child is problematic because, among other things, children are not the decision-makers in the family when it comes to food budgets, meal-preparation time, family schedules, or housing choices, all of which have important influences on food purchasing and meal options. Through trying to change the demands of children, Change4Life tried to influence the entire family's behaviors, without recognizing the limited agency that children have within family dynamics and the various restraints that families face in their decision-making.

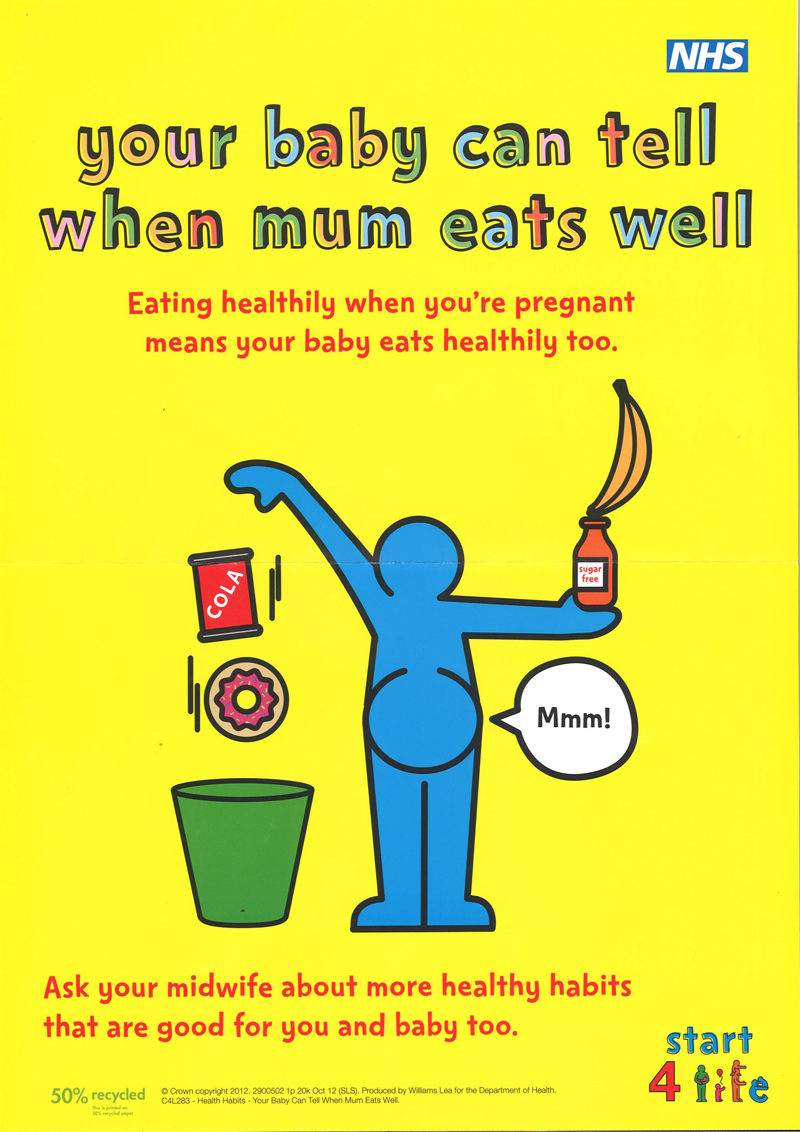

Although children were the initial target of these campaigns, mothers are the true intended target audience. It is evident that mothers are a priority group for Change4Life and Start4Life, as the rationale for the campaigns include that parents’ food-related behaviors from the womb onward affect a child's health, and that pregnancy and early years (up to age five) is a key time of intervention (PHE n.d.).Footnote 4 However, instead of being addressed directly in poster and video campaigns, mothers are spoken about to a child audience. Despite being the adult in the room and (in the case of posters) being able to read, mothers are bypassed by messages, as these directly address their fetus, infant, or child. Campaigns from Change4Life, for example, tend to speak about “Mum” in the third-person, or in a mixture of third- and first-person (Figure 1).

Figure 1. “Your baby can tell when mum eats well!” (NHS Change4Life n.d.)

A video from the Change4Life campaign series, entitled “Me Sized Meals,” begins with the lines, “Mum loves me, and thinks lots of food will make me big and strong. But she gives me enough to feed a horse!” (NHS UK Reference Kingdom2009). In such campaigns, mothers are positioned as the (guilty) bystanders of messages that are traveling past them or through them to their children about their feeding behaviors. Although mothers are necessary for the uptake of the advice or behavior change promoted by campaigns, they are appealed to only obliquely as the audience of the messages. In these textual sideways glances, health-promotion campaigns simultaneously pass judgment on mothers’ behaviors, hold them responsible (possibly blameworthy), transform mothers into tools of health promotion, and also disregard their humanity and agency as decision-makers under conditions of constraint.

Though not tied to achieving good health status (rather, to undermining health), some health-promotion messages reinforce dominant beauty ideals in the text and imagery they use, such as those that encourage women to breastfeed in order to “get your body back.” Multiple examples of such campaigns (for example, Figures 2, 3, and 5) combine different values related to feeding children (including preventing childhood obesity via breastfeeding) and to women's bodies (including obesity prevention during and after pregnancy, and that women must be thin and beautiful) into messages that on the surface seem to have little to do with health. In one campaign from NHS Chelsea and Westminster, which featured high heels and party dresses, mothers were encouraged to “be a yummier mummy” (Figures 2 and 3). This was ostensibly a breastfeeding campaign, but focused on messages emphasizing middle-class values in a neighborhood that is socially and economically diverse (to wit, Grenfell Tower is part of a council housing estate in the borough of Kensington and Chelsea). This campaign encouraged mothers to breastfeed in order to get their figures back sooner and to be able to spend extra money on shoes because of saving on food expenses. The campaign was roundly criticized (Pemberton Reference Pemberton2018), but exemplifies that mothers are encouraged, by “validated sources of authority, such as the NHS” (PHE n.d.), to lose weight rapidly after giving birth in spite of the possible ill effects of attempting to do so. This is ostensibly in order to avoid the specter of obesity for themselves and their children, but also to become once again the beautiful object of male desire.

Figures 2 and 3. “Be a Yummier Mummy” (NHS Chelsea and Westminster Foundation Trust n.d.)

Although I do not presume in this article that mothers are cisgendered females with certain biological reproductive functions, health-promotion campaigns repeatedly do, and present a very limited image of who mothers are in their campaigns. Thus, the different kinds of people, besides cisgendered, reproductively able females, who are mothers in virtue of taking up this role are made invisible by these campaigns. This has a double effect: first, it excludes mothers who do not fit the strict picture of a mother as a cisgendered female; second, it encloses cisgendered females who do (even vaguely) fit the picture into objectified images of motherhood that are defined by and subject to the dominant white heteropatriarchal gaze. In this image, a mother is not just someone who has children and cares about them, but she is also an object of male sexual attraction and receptivity to her male partner, as well as to other men.

The “Be a Star” campaign by NHS Salford highlights the problematic use of gendered stereotypes about women and motherhood in alleged health campaigns (Figure 4). This campaign used local mothers from Salford, which is west of Manchester in the north of England, and styled them as models, singers, or actresses. The campaign was focused on “showcasing the beauty, confidence and pride that comes with breastfeeding, as well as providing breastfeeding information” (NHS Salford 2008). Just one of nine campaign posters is presented here, but it shares similar textual and visual messages with the others. This campaign exhibits numerous problematic features: speaking about mothers in the third person, this time from an (implied) male partner's voice; associating the decision to be a mother and to breastfeed with deservingness of love (“just when I thought I couldn't love her any more, our son arrived . . .”); expressing that valuable options for women's employment are celebrity, singer, or model; and reinforcing that women's ultimate value lies in their appearance (“look at my girlfriend—she's gorgeous”).

Figure 4. “Be a Star” Campaign (NHS Salford 2008).

This treatment of women is hardly new. Its roots lie in the identification of women and mothers with body, nature, and food—in other words, biology—which is contingent but also culturally pervasive. These associations are highlighted when women's bodies are dismantled, in health-promotion campaigns around childhood obesity and breastfeeding, to depict only a torso, from hip to shoulder, with a focus on breasts and tummy (Figure 5). The body of a mother is a tool: a tool for carrying and birthing, then feeding children; a tool for providing beauty of a set kind in the world; a tool for satisfying the desires of male Others. Though some mothers are at ease with the reproductive utility, beauty, and eroticism their bodies have to offer, this is in spite of such instrumentalizing and objectifying imagery, and not because of it.

Figure 5. “Breastfeeding Fact No. 4” (NHS Heart of Birmingham Primary Care Trust n.d.)Footnote 5

There is much more that could be said about these campaigns in light of the socioeconomics and demographic make-up of different regions in Britain (for example, Birmingham is very ethnically and racially diverse, but the bodies in the “Breastfeeding Fact” campaign are all white; Salford is a relatively low socioeconomic area, yet the career options given for women are model, actress, or celebrity; and so on). Unfortunately, I cannot do justice to such analyses here. This is not merely to include race and class on a laundry list of issues, but to note that these are substantial and important aspects of British social context that require dedicated and careful analyses, but that lie beyond the scope of this article.

The current analysis is focused on the use of stereotyping imagery and messages within health-promotion campaigns that enclose “mother” within a problematic set of gendered and bodily (sex, reproductive) expectations. These campaigns are inappropriate from a (trans-inclusionary) feminist and moral point of view, and tactically inexplicable. Campaigns that rely on gender or beauty values to deliver a health message end up participating in the culture of chronic sexual objectification of women in typically nonsexual contexts, such as mothering or feeding one's children, and in the exclusion and rendering invisible of all kinds of mothers.

When mothers as persons and agents are made invisible in health-promotion messages, it is to the detriment of the goal of health promotion—in this case, to change something about knowledge or behavior regarding feeding children. A variety of studies has established that objectification and exclusion undermine agency, by (at least temporarily) destroying one's sense of oneself as a subject and agent, and making one feel or become invisible or passive (Young Reference Young1980; Fredrickson and Harrison Reference Fredrickson and Harrison2005). In some of these campaigns, a person sees herself represented as simply a body, or a tool, intended for the use of other people. Even if these other people are one's children (as in some breastfeeding campaigns), the mind and humanity of the mother is erased. In other cases, a person doesn't see herself at all. A mother's feelings, reasons, and motivations are made invisible, and a particular mother's body is instrumentalized in feeding children, satisfying the male gaze, or maintaining itself as an object of beauty. This process of dehumanization of mothers undermines the self-regarding attitudes that are central to agency, and therefore the uptake of health-promotion advice for behavior change (MacKay Reference MacKay2017).

It is thus that in a variety of health-promotion campaigns around childhood obesity or feeding practices for children, mothers are made into instruments and objects—both as (hetero)sexual objects of desire or beauty, and as objects of utility (via biology)—and become invisible as persons. Neither approach presents mothers as intellectual or responsible agents of choice or care, nor as a reasoning audience. In either case, mothers are not approached as full persons.

Responsibility and Causes

Having presented some examples of campaigns in Britain about mothers’ feeding choices for their children, in this section I will discuss what responsibilities mothers actually have for making specific kinds of choices when feeding their families. First, I provide a brief discussion of “lifestyle drift” in British public health and policy generally, as the concept—and problem—has a long history in this context. “Lifestyle drift” describes the tendency of policies intended to address problems with “upstream” (structural, environmental, political) causes to end up targeting “downstream” (individual or relatively disempowered) actors. This term has become familiar recently, as increasing numbers of collective problems appear to be addressed via a model of individual consumer choice and behavior change.

Interestingly, in public health, there is a strong tradition of collective responsibility, and generally what could be considered a consensus among public-health researchers and practitioners that downstream-focused initiatives cannot provide the important upstream changes required for long-lasting improvements in health (MacKay and Quigley Reference MacKay and Quigley2018). British research into the social determinants of health is particularly strong, reaching back at least as far as Maud Pember Reeves's book, “Round About a Pound a Week,” which examined the lives of working-class poor families, with a special focus on mothers’ abilities to feed their families (Pember Reeves Reference Pember Reeves1913/1980). Over one hundred years ago, Pember Reeves reported that families with at least one member working (typically the father) could scarcely afford to feed themselves properly and faced a greater number of illnesses and a higher rate of infant and childhood mortality than other socioeconomic groups.

Sixty-five years after Pember Reeves reported these findings, Michael Marmot began the Whitehall Study of British civil servants. He and his team reported that there was a strong connection between social class (as defined by income) and mortality from a wide range of diseases (Marmot et al. Reference Marmot, Rose, Shipley and Hamilton1978). However, the Whitehall II Study, published thirteen years later, found no reduction in the inequity of social class and disease susceptibility, despite their work and the work of others to promote the idea that social-class systems had a measurable impact on individual health (Marmot et al. Reference Marmot, Stansfeld, Patel, North, Head, White, Brunner and Feeney1991). Whitehall II reported on the kind of risk behaviors now associated with “lifestyle diseases” (smoking, diet, and exercise) and found clear differences between the better-off cohort and the worse-off, which were attributed in part to the effects on the worse-off of leading intolerably stressful lives.

More recently, and as mentioned above, it is now well established that socioeconomic status, obesity, and diet quality are linked. Studies and statistical reports from Britain and other jurisdictions show that one group of people who are more likely to be or become obese are those with lower educational attainment, less secure employment or financial stability, and less secure housing (for example, Rich Reference Rich2011; Chaufan et al. Reference Chaufan, Jarmin Yeh and Fox2015; Warin et al. Reference Warin, Zivkovic, Moore, Ward and Jones2015; PHE 2018a). Women in the lowest income group in Britain are almost twice as likely to be obese as women in higher income groups (NHS Digital 2018a); low-income mothers are also more likely to miss meals so that their children can have enough to eat (McIntyre et al. Reference McIntyre, Theresa Glanville, Raine, Dayle, Anderson and Battaglia2003). Data reported in April 2018 by the NHS states that one in every six children in year six at school (children who are approximately ten years old, or in sixth grade) is obese (according to BMI classification), and that the gap between the prevalence of obesity for the most deprived and least deprived groups of children has steadily increased over the past ten years (NHS Digital 2018b). As mentioned above, white women in lower socioeconomic categories in Britain are also less likely to initiate or maintain breastfeeding. Despite the close relation between food insecurity, poor nutritional quality, and low income level, childhood obesity gets far more attention in popular culture and media reports than childhood poverty, and seems to be the subject of a great deal more social and political concern (Bell, McNaughton, and Salmon Reference Bell, McNaughton and Salmon2009). There is still a dearth of evidence to support the wide-reaching claims about the health benefits of breastfeeding, but it is very clear that poverty is bad for one's health.

In the face of considerable evidence of the link between lower breastfeeding, higher obesity, and poverty in Britain, the overwhelming emphasis on feeding choices as “lifestyle” issues presents a puzzle. Plenty of evidence suggests that income and resources, including transport options and local availability of affordable and healthy food, affects food choices, eating behaviors, and overall health (Lang and Caraher Reference Lang and Caraher1998). The view that governments and other systems-level actors (corporations, say) are accountable has not found political favor. Rather, a story inflected with the value of individual responsibility was established early on in health-promotion circles (Williams and Fullagar Reference Williams and Fullagar2018), and health promotion in Britain has favored “an emphasis on individual processes, the main focus of which is seen to be ignorance” (Lang and Caraher Reference Lang and Caraher1998, 203). Structural or systems-level issues are cashed out as a knowledge problem, the solution to which is education and empowerment. That said, the values and beliefs of public-health professionals regarding feeding choices are not necessarily reflected in the campaigns created by public-health agencies; they are sometimes consulted in the creation of campaigns, but sometimes not. At the level of government and policy, however, there is a great deal of evidence to suggest that this remains the dominant approach to health promotion (for example, Kukla Reference Kukla2006; Brownell et al. Reference Brownell, Kersh, Ludwig, Post, Puhl, Schwartz and Willett2010; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2012; Carey et al. Reference Carey, Malbon, Crammond, Pescud and Baker2017; MacKay and Quigley Reference MacKay and Quigley2018; Williams and Fullagar Reference Williams and Fullagar2018).

In the following, I will argue that issues of obesity and poor nutrition among children are improperly framed as individual expressions of failures of maternal duty, rather than as failures of a system to function correctly, and have been for some time. This particular framing permits British governments to maintain an individualistic, consumer-oriented approach to problems in social and food systems, and to maintain the status quo of power relations between privileged and less-privileged groups (Williams and Fullagar Reference Williams and Fullagar2018). The following analysis explores the ways in which responsibility for obesity is shifted from the public and collective agents of government or corporations (those with primary agency over the food system) to the private and individualized actors of families, and within families, to mothers specifically. Though conceptualized to some degree as a (relatively disempowered) group, mothers are left to face systemic challenges of the food system on their own, and are evaluated one by one for their efforts.

First, however, I will discuss the selection of causal narratives used to justify this shift in responsibility. In cases of lifestyle drift, an argument for something's being a matter of individual consumer choice is employed to forestall or waylay a collective change. A ready example is the New York City soda-size restriction measures, which ultimately failed (Bateman-House et al. Reference Bateman-House, Bayer, Colgrove, Fairchild and McMahon2018). In this case, a change in the sizes of cups available at soda fountains, which may have resulted in an environmental change such that individuals would consume less soda overall, was argued down on the basis of inappropriately limiting individual choices. Soda companies have been aggressive in defending individual consumer choice as a keystone of freedom and personal expression. What was intended as an environmental change became framed (and defeated) on individual grounds, in turn shaping how obesity and eating habits are perceived. That is, rather than thinking of drinking too much soda simply as a result of having cups that are too big, how much soda one drinks became a firm matter of individual autonomy and rational choice. Thus, if a person experiences negative effects from drinking large amounts of soda, it is the individual's fault through the choices they made (so the story goes), and not a problem with the environment.

Part of what is revealed by this example is a guiding “ethos of personal responsibility” (Young Reference Young2011, 10). In the debate around health, feeding, eating, and food-purchasing, behaviors are presented as personal choices that one simply needs to improve. Responsibility for health issues (especially, it seems, obesity and certain kinds of cancer) is typically framed in either/or terms; either it is an individual responsibility, or it is a collective responsibility (Young Reference Young2011, 4). This seems not to allow for the more reasonable thought that the two areas of collective and individual responsibility dynamically interact with each other. Rather, on this view, instances of obesity or poor nutrition are simply the fault of each individual for not heeding nutrition information and changing their behaviors appropriately.

This reveals the selection of a specific causal story, the choice of which Robin Zheng has recently argued is presented as empirical, but is in fact heavily normative. Causal explanations, especially of social phenomena, Zheng argues, depend on certain kinds of value judgment, including about moral responsibility (Zheng Reference Zheng2018, 324). When we decide that X is a problem, we tend to seek the party who is culpable, but in order to discover who is responsible, we must figure out why X is happening in the first place. However, selection of some one factor among the many interconnected contributors as “The Cause” of X, Zheng argues, involves normative judgments, not only empirical judgments. So, the selection of The Cause of a health concern relies on our judgments about things like moral goodness, in addition to (or perhaps in place of) things like disease etiology and epidemiological findings. Lisa Gannett has further argued that scientific attention to specific individual-level causes (like genetics, epigenetics, or behavior), as opposed to wider environmental factors for disease, has been driven in part by political and funding priorities of governments, who are motivated to reduce spending and avoid “nanny-state” interventionism (Gannett Reference Gannett1999).

This indicates that our judgment about what is The Cause of X is not entirely revisable based upon further empirical evidence, and that who we then select as responsible, based upon the assigned causes, is likewise not easily revised with the introduction of new evidence. In the case of obesity, at least, this process reveals a fundamental attribution error (Zheng Reference Zheng2018, 326). That is, in shifting the focus of obesity and feeding behaviors from environments or structures to individuals, we have relied on a Victorian-era correspondence bias that presumes that one's behavior or outward appearance reveals deep and stable character traits. We have succumbed to a kind of whole-body phrenology, as it were, assuming that the body's appearance can tell us about ability, attitude, knowledge-states, and beliefs. Evidence shows, for example, that at work or at school, people with larger-than-average body size suffer from negative stereotypes and stigmas that assume them to be lazy, incompetent, unambitious, and unintelligent based only upon body size (Puhl and Heuer Reference Puhl and Heuer2009; Reference Puhl and Heuer2010; Abu-Odeh Reference Abu-Odeh2014). This is an important argument, given that a central position among many health experts and policymakers is that their recommendations are (or would be, theoretically) open to revision based upon appropriate empirical findings. Zheng's argument contends, rather, that even as the evidence of collective responsibility and structural etiology piles up, we shall continue to find individuals responsible for obesity and poor nutrition due to the influence of our moral (and other) judgments about certain individuals.

As a result of the individual attribution of responsibility for eating behaviors and body weight, the goal of health-promotion efforts has largely been the “empowerment” of individuals, to help them to “make healthier choices.” Nutritional quality, eating habits, feeding choices, and body size are all considered to be individual matters and individual failings. So, the causal story about X (obesity, poor nutrition) has become one of a failure of an individual's specific duty to do Y, whatever Y is. The way this individualistic and consumer-focused interpretation of responsibility cashes out in families is that mothers are held responsible for the body weight of family members, and especially children. However, though mothers have a duty to benefit their children, there is no specific duty to do Y when it comes to taking appropriate care of a child's health. The specific-act interpretation of a mother's duty to benefit is exceedingly demanding and inappropriate.

The Imperfect Maternal Duty to Benefit

As discussed above, mothers tend to be the primary feeders of the family, and feeding choices for children, from even before pregnancy for cisgendered females, is framed as a central maternal responsibility. This role, in tandem with the generally individualizing trends of lifestyle drift in health promotion, means that concerns about childhood obesity are being translated into worries about failures of specific maternal duty and the association of these failures with risks to children's health (Lee Reference Lee2008). Readers may be familiar with the sensationalist claim that “feminism caused the obesity crisis” by removing mothers from the home and family and encouraging them to seek careers, which in turn (it is claimed) led to an overreliance on convenience foods and a loss of food knowledge in the next generation, and so on (Sanderson Reference Sanderson2017). This narrative has deep roots, going back at least to the late nineteenth century, as industrialization meant more women were working. James Walton presents an intriguing account of the attacks upon fish and chips by British Medical Officers of Health (Walton Reference Walton1989). These officers saw a rise in consumption of fish and chips as a worrisome part of a larger negative lifestyle trend, which they alleged resulted from women's joining the workforce; it meant they were no longer cooking properly at home for their families.

In the current public discourse, the alleged risks to children posed by “irresponsible” mothers (where “irresponsible” is employed as a code word, and could mean working, single, poor, “indulgent,” lazy, black, or minority, for example) range from the loss of potential benefits from home cooking or breastfeeding, to becoming an overweight or obese child, to serious cases of malnutrition or neglect. Various researchers have found that society (and public health) considers mothers to be blameworthy for failing in their perceived duties toward their children if their children are not fed in the “right way,” that is, if they are not breastfed for the government-recommended amounts of time, or are not provided with just the right amount of healthy, home-cooked foods (Kukla Reference Kukla2008; Bell et al. Reference Bell, McNaughton and Salmon2009; Hartley-Brewer Reference Hartley-Brewer2015).

In a recent infographic from Public Health England (Figure 6), data is presented about how frequently people are eating outside the home, and features images of “unhealthy” foods, like doughnuts and hamburgers. The information is presented in the passive voice, and no person is labelled as accountable, but it is reasonable to read this graphic as pointing the finger at mothers. This would seem particularly true in the first panel, discussing children's out-of-home eating behaviors. As mentioned, mothers are still the primary feeders of British families, and as we see from the discussion above, if families are eating out of the home “too frequently,” the assumption is (I think) that mothers are not cooking for them.

Figure 6. “Food and drink environment” (PHE 2018b).

This indication of the duties that mothers are presumed to have presses us to ask what kind of duties mothers actually have regarding feeding their children, given that society and public health place certain demands upon them and want to hold them accountable. In pursuing this question, I follow Woollard and Porter in thinking that mothers have a general duty to benefit their children, rather than a specific duty to do Y beneficial thing. Writing specifically about breastfeeding, Woollard and Porter argue that mothers are treated as if they have a defeasible duty to breastfeed, which implies accountability such that failure to breastfeed is open to censure, and that this view of breastfeeding is unwarranted (Woollard and Porter Reference Woollard and Porter2017, 516). Indeed, mothers are under increased pressure to breastfeed of late, as breastfeeding one's baby is promoted as being one way of preventing childhood obesity and is also promoted as helping mothers lose weight they have gained during pregnancy (see Figures 3 and 5). Claims about there being a range of general benefits to breastfeeding an infant have increasingly become tangled with the use of breastfeeding as a prevention mechanism for childhood obesity. Ellie Lee and Frank Furedi argue that “a process of cultural transmission seems to have turned provision of health information about the benefits of breastfeeding into hostility about formula use” (Lee and Furedi Reference Lee and Furedi2005, 70), on the as yet under-studied grounds that formula-fed babies may be at greater risk for obesity later in life (Bergmann et al. Reference Bergmann, Bergmann, Von Kries, Böhm, Richter, Dudenhausen and Wahn2003; Oddy et al. Reference Oddy, Mori, Huang, Marsh, Pennell, Chivers, Hands, Jacoby, Rzehak, Koletzko and Beilin2014). What mothers eat before pregnancy, during pregnancy, and when breastfeeding is also now considered a matter of public-health concern, due to findings from research into epigenetics that has suggested that “obesity genes” can be activated in the gestational process, or even before (Dabelea and Crume Reference Dabelea and Crume2011; Dovey Reference Dovey2015).

Woollard and Porter argue that “the claim that a duty to benefit someone implies a defeasible duty to carry out a particular act that will benefit them—for example, that a duty to benefit one's child implies a duty to breastfeed—trades on an ambiguity in the notion of a duty” (Woollard and Porter Reference Woollard and Porter2017, 516). This ambiguity lies in that “by saying ‘You have a duty to . . . , ’ we may intend either to state a general principle or to declare that a person is required to do something on a particular occasion” (Hill Reference Hill1971, 64). Woollard and Porter argue that the claim that a mother has an imperfect duty to benefit her child fits the description of a “general principle,” as illustrated by the claim, “you have a duty to help others (sometimes)” (Woollard and Porter Reference Woollard and Porter2017, 516). Insofar as general principles can often be fulfilled in various ways, via various acts, they enable moral agents to fulfill the principle according to their discretion. Such a general principle does not imply a duty to carry out each specific act that may help another, and insofar as mothers have a general duty to benefit, it is not the case that they have a duty to carry out each specific act that might benefit their child. Such maximizing terms as “duty to benefit” or “benefiting one's child” are rarely apt, because it is not possible to do all of the things that might benefit one's child, nor is it necessary in practical terms. Rather, as a general principle, the duty to benefit provides a moral reason to do an act, which can be defeated by other reasons to not do this act or to do other acts.

However, British health-promotion material focused on feeding children frames acts that fall under the general duty to benefit as acts connected to a specific duty. Public health-promotion campaigns appear to take the approach that mothers have duties relating to specific acts with regard to feeding their children, which might include a duty to breastfeed, to provide specific foods, or to make home-cooked meals. As these acts are interpreted as connected to specific maternal duties, not doing the required act is grounds for blame. Insofar as act-specific duties are carried by individuals, they further reinforce the individualizing causal story of obesity or poor childhood nutrition. Failure to discharge the duty is an individual failure, which permits the act of blame instead of triggering mechanisms of collective responsibility. We see expressions of blaming mothers in popular media and in health-promotion campaigns (Hartley-Brewer Reference Hartley-Brewer2015; Bergstein Reference Bergstein2018; Loria Reference Loria2018). This is unjustified, however, since the duty to benefit one's child is a general one. To interpret the duty to benefit as specific is to place inappropriately high moral demands on mothers. Under a general duty to benefit, the demandingness of public-health expectations for mothers’ behavior exceeds what maternal duties actually require.

This misinterpretation of a mother's duty toward feeding her children goes largely unnoticed or unremarked upon in the public discourse around childhood obesity and feeding behaviors. Despite being inappropriately demanding upon mothers, act-specific interpretations of the duty to benefit are frequently promoted in various campaigns. A corollary of this is that mothers’ feeding behaviors are analyzed predominantly on a case-by-case basis. This means that instances of a mother's not breastfeeding (at all or for long enough) or not providing home-cooked meals or fresh (enough) foods, are evaluated one mother at a time and in the context of her consumption habits or knowledge (Kukla Reference Kukla2006), in isolation from wider structures and systems influencing the context of her choices.

One problem with this, clearly, is that it does not reflect the structural and multifactorial nature of feeding behaviors. Mothers in less socioeconomically advantaged groups frequently have to make trade-offs. Evidence suggests that most mothers know what an optimal diet for their children would be composed of, yet many find their food-based decision-making constrained by other features of their lives, such as work schedules and budgets (Dowler Reference Dowler1998; Lang and Caraher Reference Lang and Caraher1998; Kukla Reference Kukla2006; Rich Reference Rich2011). Tim Lang and Martin Caraher report that “women perform a role as negotiators and mediators in domestic food culture,” balancing, as they must, “concerns about healthy eating with those of taste, waste, and value for money” (Lang and Caraher Reference Lang and Caraher1998, 206). They may reasonably choose to spend money on utility bills over healthier or fresh food; choose to allow their children more time for sleep over time it would take to cook a meal; choose pleasure over displeasure of taste; choose ease of mealtimes and enjoyment of each other's company over difficulties that may arise from arguing about what's for supper; and so on, each of these being reasonable in their own context. Lang and Caraher and Emma Rich report just these kinds of trade-offs being made by mothers who are making good decisions within their context (Lang and Caraher Reference Lang and Caraher1998; Rich Reference Rich2011).

Individualistic approaches such as we see resulting from lifestyle drift in public health set mothers up to fail against structural problems. The hegemony of individual responsibility for obesity, including mothers’ responsibility for childhood obesity, and the corresponding health-promotion strategy focused on “empowerment” leaves mothers in the impossible situation of each having to somehow overcome systemic problems (for example, decisions about bus routes and schedules; the location of grocery stores) by herself. This is symptomatic of a tendency in government responses and public discourse to improperly frame food and eating behaviors as failures of act-specific duties, rather than as either (a) successful discharges of the general duty to benefit under constraint, or (b) failures of some collective duty. There may indeed be a collective duty upon society to ensure the requirements for a minimally decent life to all members, including the necessities of life, which has been overshadowed by the ethos of personal responsibility. Via lifestyle drift and the individualistic values that underpin it, the government projects its own responsibilities onto people living under unjust structures, thereby shifting the burden of responsibility. In this context, a government may consider its duty to its citizens to be discharged by taking the individual approach, focused largely on empowerment and providing information via health-promotion campaigns, even while ignoring the wealth of evidence demonstrating the structural etiology of obesity and other chronic disease.

Before moving on, it may be important to investigate whether the argument for the general principle to benefit applies only to some kinds of behaviors, or whether there any specific maternal duties. One might be tempted to say that in addition to the general principle of the duty to benefit, there are specific duties, for example, to vaccinate or to educate one's child, based upon our considered moral beliefs about the treatment of children and the independent value of vaccination or education. Woollard and Porter suggest that one could defend specific duties of this nature. They write, “it is clear that parents can have duties to perform some specific acts. For example, parents clearly have a defeasible duty to feed their children. It also seems plausible that parents in modern democracies have a defeasible duty to teach their children to read” (Woollard and Porter Reference Woollard and Porter2017, 517). However, they argue that the strength of these duties must be defended by those who wish to establish that they are required. The general principle of a duty to benefit cannot be understood as a maximal duty, as it is implausible to suggest that a mother must do every act that would benefit her child. Though clearly a variety of beneficial acts must be performed, there is no set list of specific acts that can be given, only a broad and general list. So, “while there are clearly some beneficent acts that parents have a duty to perform, it can't simply follow from the fact that an act is beneficial that the mother has a duty to do it” (517).

Vaccination provides an interesting case, because it may plausibly fall under a core category of acts that could be described as “those that ensure the life and health of a child,” providing the strongest possible reasons to carry them out. Yet I would argue that if there is a duty to vaccinate one's child it is fully captured under the general duty to benefit, rather than being an independent or specific duty. This is because it is not possible for every mother to fulfill this duty, because not every child can be vaccinated. Children with compromised immune systems because of chemotherapy, for example, cannot be immunized, and they further lose immunity to infectious disease in relation to the length of time under treatment (New Zealand Ministry of Health 2014). Children with anaphylactic allergy to vaccine ingredients (such as egg) are also unable to receive immunizations with those ingredients (Australian Government Department of Health 2017). This is precisely why it is crucially important to maintain population vaccination levels consistent with herd immunity (for example, for measles, approximately 95% vaccination in the population). We know that there are people in our community who are unable to be vaccinated, so it would seem that there are very good moral and practical reasons that everyone who may be vaccinated is vaccinated, but it also seems that the mother of a child who cannot be vaccinated is not failing in a specific duty to vaccinate. Rather, in such a case, a mother is fulfilling the general duty to benefit by not having the child vaccinated. What this demonstrates is that because there are innumerable mitigating circumstances and unique contexts between mothers and children, the general duty to benefit captures the central range of maternal (and paternal) obligations toward benefiting children. As such, it may be possible to establish certain duties regarding vaccination or education, or indeed other things, on separate grounds, but not via a specific duty to benefit.

Conclusions: Respect and Responsibility

There is no one person or group to blame for “lifestyle” diseases, such as obesity. Rather, we need to accept collective responsibility for the various systems we participate in that support unjust and harmful practices, policies, and attitudes. My argument supports such collective responsibility, and shifting the focus of responsibility for “lifestyle” issues away from mothers and individual consumers and back toward policymakers. The moral demands that are too high for mothers may be met by systemic or policy-level changes. In the current case, policy-level change is called for at least in the systems of food procurement, production, and sale; housing maintenance and affordability; wealth distribution; employment and education; and urban design and public transportation. To the extent that one holds there is a collective, governmental, or corporate responsibility with regard to long-term health issues that arise in part from these structures, much less tokenistic measures than health-promotion campaigns that target individual mothers are required. If health-promotion campaigns continue to be produced, however, as a part of more broadly reaching initiatives, those in charge of design need to think carefully about the text and imagery. These decision-makers should plainly justify why the representation of mothers as enclosed, objectified, and instrumentalized, or their total exclusion, is necessary or appropriate means for reaching the aims of health promotion. In the absence of such justifications, the imagery and messages in campaigns about feeding children must become more inclusive, more diverse, and more respectful of the mothers—as complex, feeling, and rational persons—who make up the target audience of the interventions. Mothers must become participants, not instruments, in health promotion.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Northern Bioethics Network hosted at Lancaster University, the Philosophy Department at Liverpool University, the audience at the conference for the Society for Applied Philosophy held in Utrecht, and colleagues at Sydney Health Ethics for providing helpful comments on this article as it developed. Thank you to Garrath Williams for helpful conversation and comments on an early draft, and to two anonymous reviewers whose constructive comments helped shape the final version.

Kathryn L. MacKay is a Lecturer at Sydney Health Ethics, University of Sydney, Australia. Her research focuses on issues of human flourishing at the intersection of feminist theory, ethics, and political philosophy. She is particularly interested in questions related to power, health and well-being, identity and group relations, and personal and group agency. She is currently working on the role of mothers in health-promotion strategies, and the nature of compassion and its possibilities for providing answers to challenges such as climate change, socioeconomic inequality, and chronic disease. Kathryn.mackay@sydney.edu.au