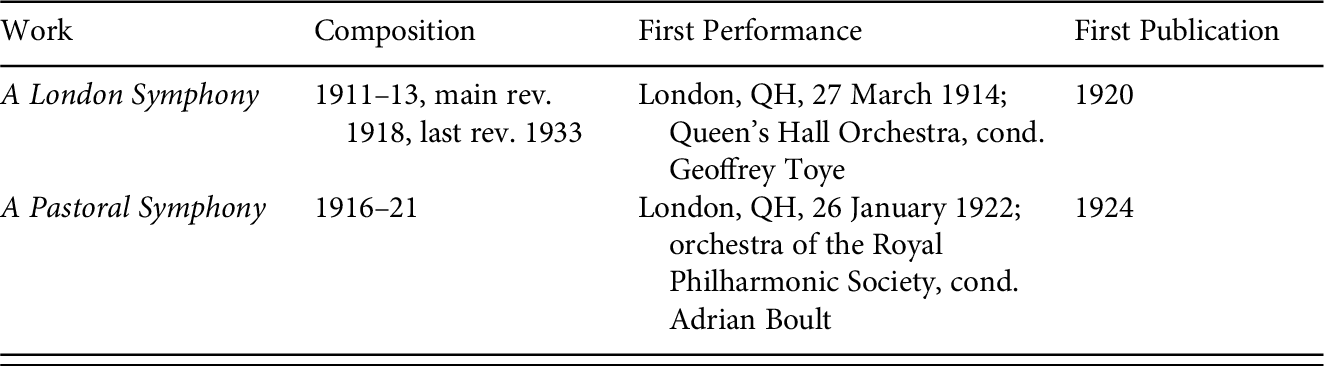

Part II Works by genre

4 History and geography: the early orchestral works and the first three symphonies

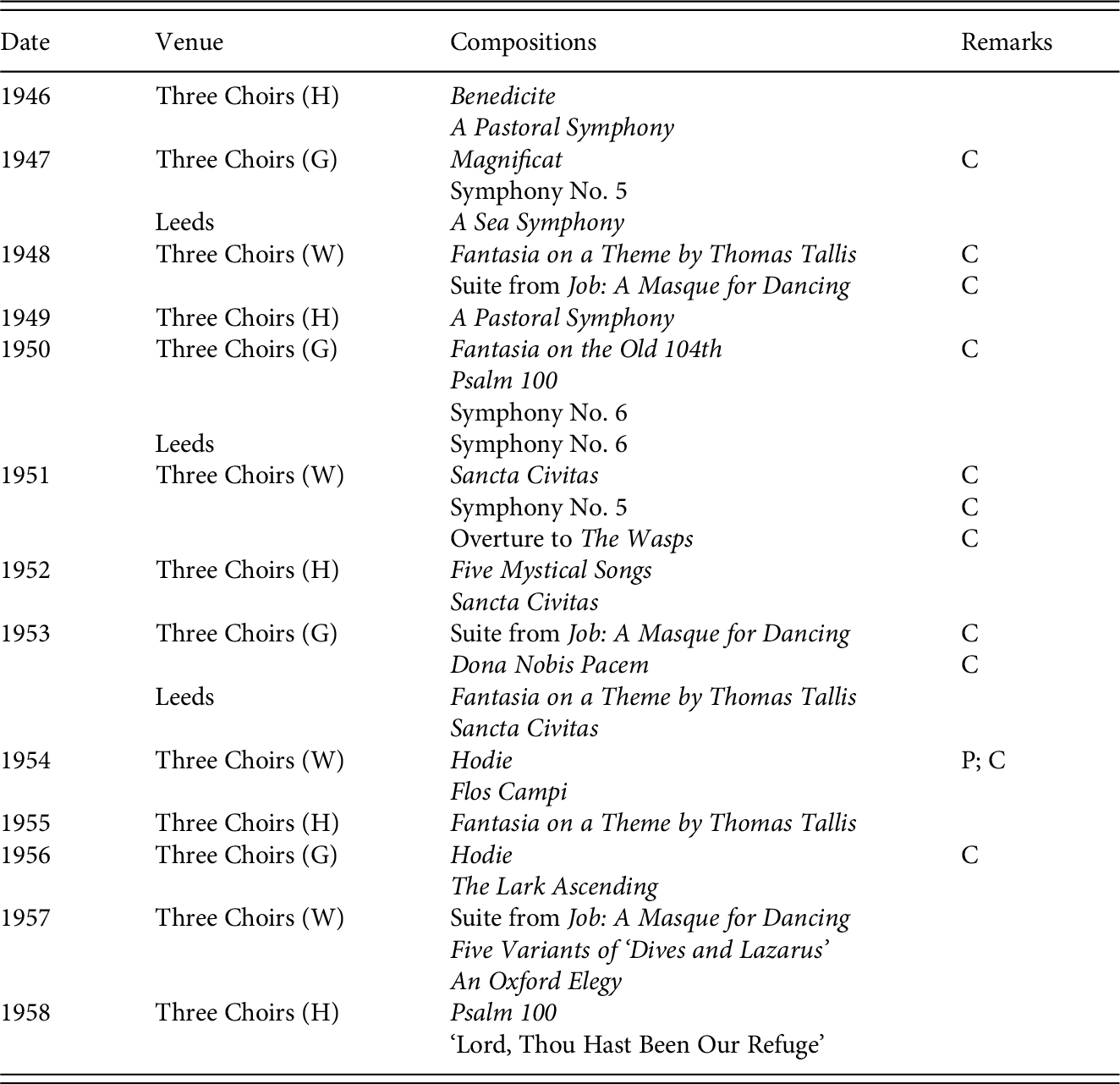

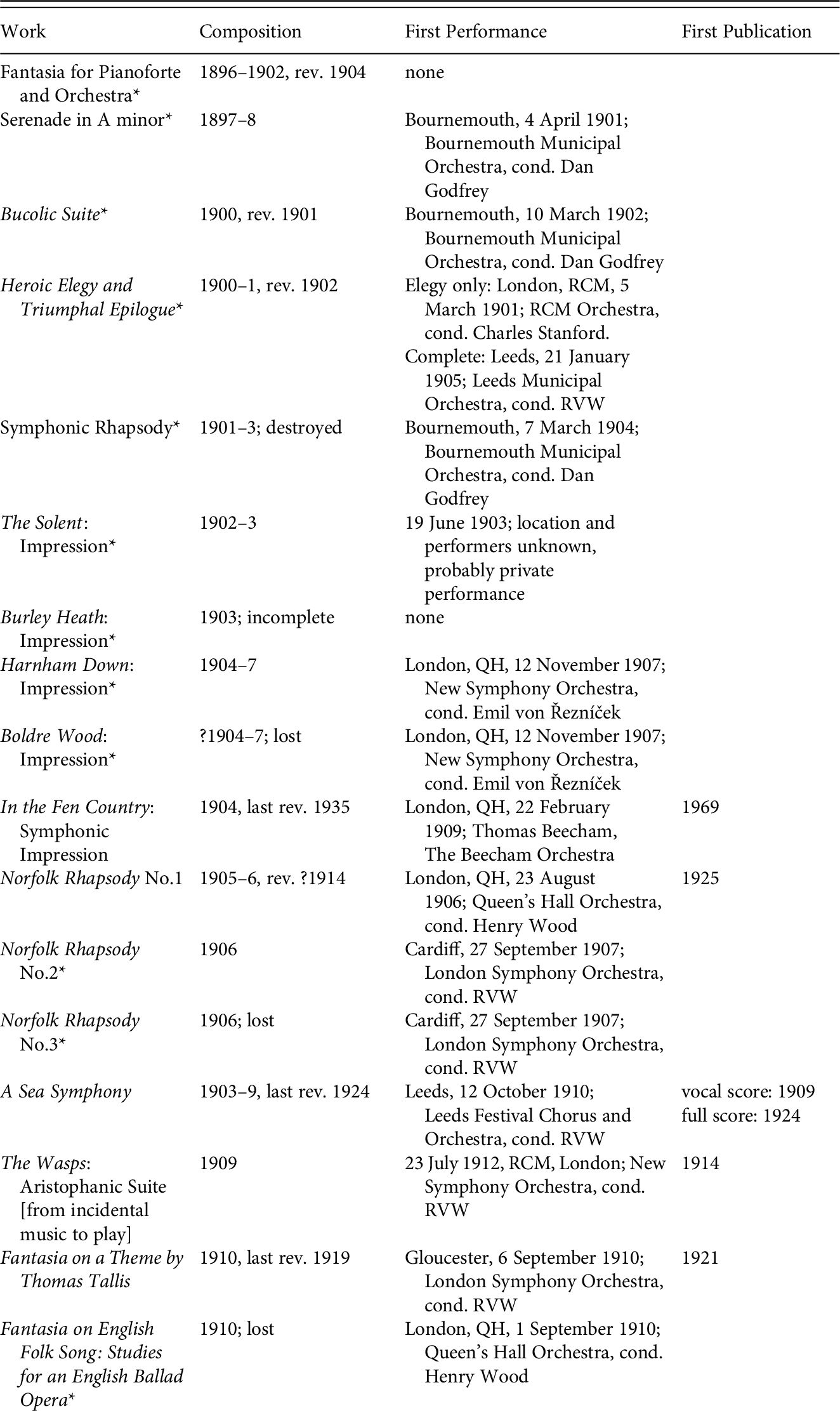

Vaughan Williams’s early development as a composer has been significantly obscured by three interrelated factors, all of which tend to set him off from major contemporaries. Firstly, by 1920, as he approached his fiftieth birthday, he had withdrawn almost twenty substantial works composed in the two decades leading up to 1914, works that with few exceptions had already been performed and had received broadly positive critical attention. Secondly, most of these works were written after the composer had turned thirty, and a number of them after he had already achieved some notable public successes, and thus could be considered to represent at least a first maturity (even if he did not necessarily see it in those terms). Thirdly, most of the withdrawn works are for orchestra or chamber ensembles: that is, not in the genres with which his early emergence as a composer has traditionally been most strongly associated, namely solo song and large-scale choral music (e.g. the Songs of Travel, On Wenlock Edge and Toward the Unknown Region). In fact, Vaughan Williams expended the greater part of his compositional energy during the period from the late 1890s up to 1914 in writing substantial chamber and orchestral works, especially the latter. It is well known that Vaughan Williams was a late developer, but this wide-ranging suppression of works that can hardly count as juvenilia is unusual among composers. The years 1898–1907 were especially rich in projects that were later withdrawn (see Table 4.1, which lists all the composer’s orchestral works up to 1925).1 In the case of the orchestral music, the impact of this cull on our understanding of the composer’s development is partly mitigated by the retention in his public oeuvre of the Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1 and In the Fen Country, both composed before 1907 (albeit later revised), but these two pieces alone cannot represent an extremely varied body of music in its entirety. One other early orchestral work, the Heroic Elegy and Triumphal Epilogue, has now been published and recorded, and there are plans to revive some others; autograph scores survive, in the British Library in most cases, for nearly all the withdrawn orchestral works.

Table 4.1 Vaughan Williams’s orchestral works to 1925

* – withdrawn

rev.– revised

- QH

Queen’s Hall

- RCM

Royal College of Music

- RVW

Ralph Vaughan Williams (Recent performances and publication of withdrawn works are not included.)

Our interest in Vaughan Williams’s development in the orchestral field is rendered especially acute by his later emergence as arguably Britain’s most important twentieth-century symphonist. This process began in the years before 1925 with the first three of the eventual corpus of nine symphonies: A Sea Symphony, A London Symphony, and A Pastoral Symphony, first performed in 1910, 1914 and 1922 respectively. Yet these unusual works further complicate the shape of the composer’s career: with the partial exception of the London, none of them can be straightforwardly integrated into the symphonic tradition, as we shall see further below. For most commentators it was only in the mid-1930s, with his Fourth Symphony, that Vaughan Williams seemed finally to enter the symphonic mainstream. Indeed, all the composer’s pre-1925 orchestral works reflect upon and engage with wider questions of genre facing composers of the period, and particular issues raised by the composer’s own stylistic proclivities – challenges to which Vaughan Williams responded with a high degree of imagination, if not always with a consistent level of success. These works also reflect the composer’s preoccupations with his particular identity as a British composer, and how the embodiment in his music of specific elements of geographical and historical situation – of place, space and time – could contribute to that identity. Indeed, it can be argued that during the period surveyed here Vaughan Williams engaged with such questions, especially those of geography, more intensively than at any other time in his career.

One implication of genre, or at least medium, was practical, specifically the place of the orchestra in British musical life of the early 1900s. Orchestral activities were on a healthier footing than when Elgar began his career, but conditions were still challenging compared to those in some other nations, most notably in central Europe.2 Performance opportunities remained sharply limited, publishing outlets even more so, to the extent that only one of Vaughan Williams’s strictly orchestral pieces, the suite from his incidental music for Aristophanes’ The Wasps, appeared in print before the First World War, and this with the German publisher Schott; several choral–orchestral works, including A Sea Symphony, were published by Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig. Vocal and choral music generally found a readier market, largely because of sales to amateur performers, and so it is perhaps no surprise that the composer’s first published works of any kind were in these genres. Indeed, it seems doubtful that he would have been able to concentrate to the degree that he did on orchestral music if he had not had a small private income to supplement his compositional activities. In terms of securing performances he was heavily reliant on connections from his days at the Royal College of Music, his teacher Stanford in particular, and on the encouragement to younger composers given by Dan Godfrey and the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, and Henry Wood in his Promenade Concerts at Queen’s Hall in London, though Thomas Beecham and Emil von Řezníček also conducted his music on isolated occasions.3

Earliest works

Vaughan Williams’s first sustained engagement with orchestral music began in the second half of the 1890s and came to fruition initially with a number of performances in 1901 and 1902. As can be seen from Table 4.1, the first piece on which the composer embarked, the Fantasia for Pianoforte and Orchestra, was in fact never performed, though he worked on it on and off between 1896 and 1904. The Fantasia was one of a number of early orchestral works that were revised (in some cases more than once) after an initial phase of composition, and sometimes after a first performance; this complicates an already patchy documentary record of compositional and performance history, though we are at least helped by the fact that at this stage of his career the composer often recorded dates of composition and subsequent revision in his manuscripts, a practice unfortunately abandoned in later life. Some works, for example the Symphonic Rhapsody, were apparently withdrawn after a single performance, whereas others, such as the Bucolic Suite and the Heroic Elegy and Triumphal Epilogue, received several. In most cases the works were not withdrawn in a single and definitive act but simply allowed to lapse into obscurity. The biggest obstacle to a full assessment of the pre-1908 works, however, is the fact that for the most part we cannot hear them in performance and must rely on the scores alone; this situation is beginning to change, as was noted above, but it will be some time before a fuller picture can be formed. This would be unfortunate with any composer, but in Vaughan Williams’s case the real impact of his music is often especially difficult to imagine with any accuracy from the page alone.

Nevertheless, the scores alone can still tell us a great deal. The four works composed at the turn of the century show a thoughtful, and at times impressive, handling of late Romantic forms and orchestration, with attractive and at times compelling melodic and harmonic invention that, while not yet steeped in the fully developed modality that would characterize his later work, does contain flashes of the mature Vaughan Williams that would emerge over the next decade. The titles are abstract, or invoke generalized semantic associations rather than a specific programme; while all four works pre-date the composer’s intensive involvement with folksong, they do partake of the kinds of generic pastoral elements well established in nineteenth-century music. Vaughan Williams’s models for the Bucolic Suite and the Serenade seem to have been Brahms and Dvořák primarily (filtered in part through his RCM teachers, Stanford and Parry), along with Max Bruch, with whom Vaughan Williams studied in Berlin. In contrast, as Michael Vaillancourt has noted, the Piano Fantasia and the Heroic Elegy and Triumphal Epilogue suggest the more self-consciously ‘progressive’ central-European stream of Liszt, Strauss and Mahler, in terms particularly of development and thematic transformation within one-movement or cyclic formal structures (the Symphonic Rhapsody, whose manuscript the composer seems to have destroyed, may well have reflected similar influences).4 In terms of orchestration, the composer used a variety of different ensembles, with an often deft and poetic handling of his resources; this is especially true of the Bucolic Suite, which includes a range of percussion, and wind and string exchanges in the second movement that bring to mind Tchaikovsky. Though Vaughan Williams would later write that by the end of 1907 he felt that his music was ‘stodgy and lumpy’, and that it was this that led him to take lessons with Ravel,5 he was certainly capable of a light touch in these early works.

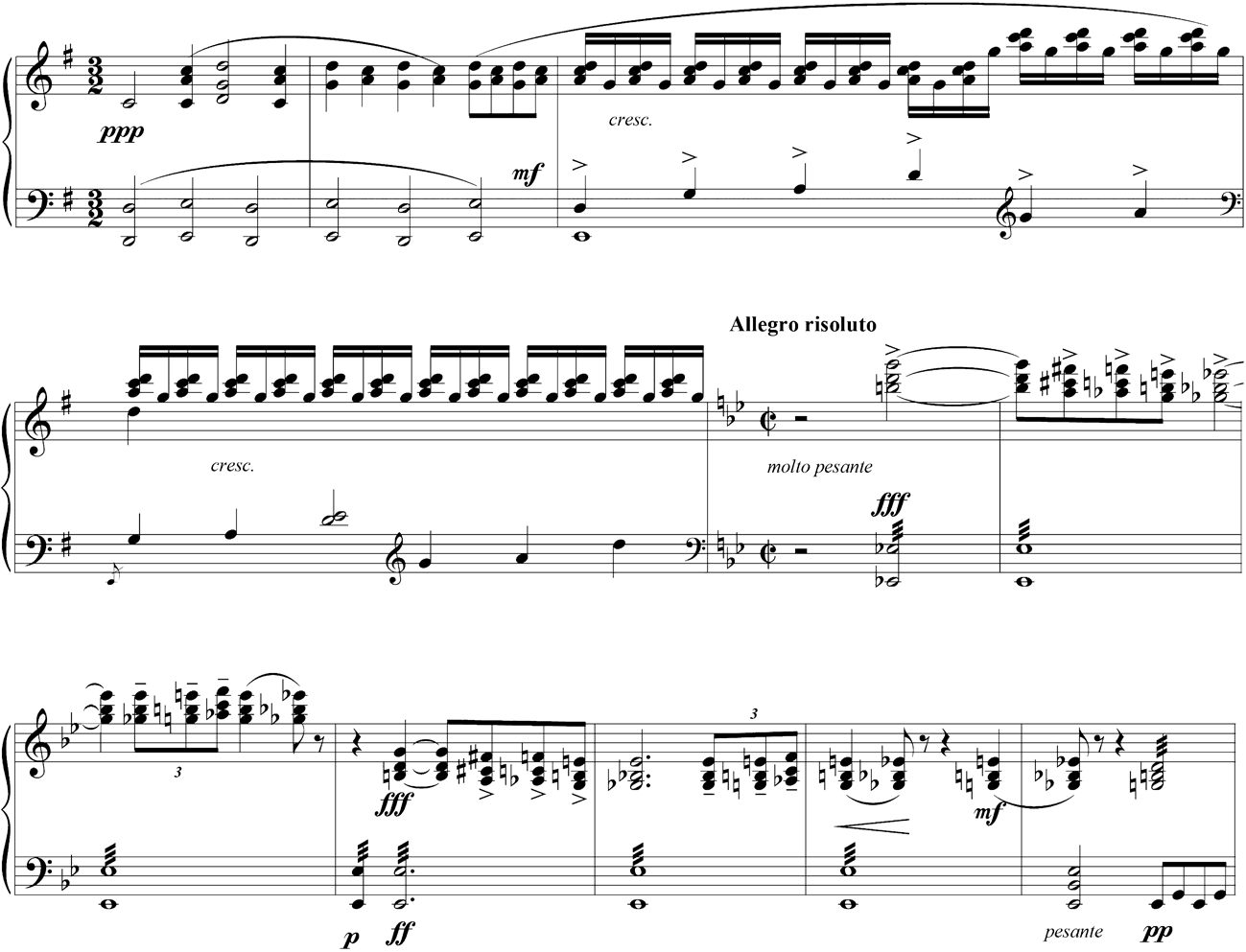

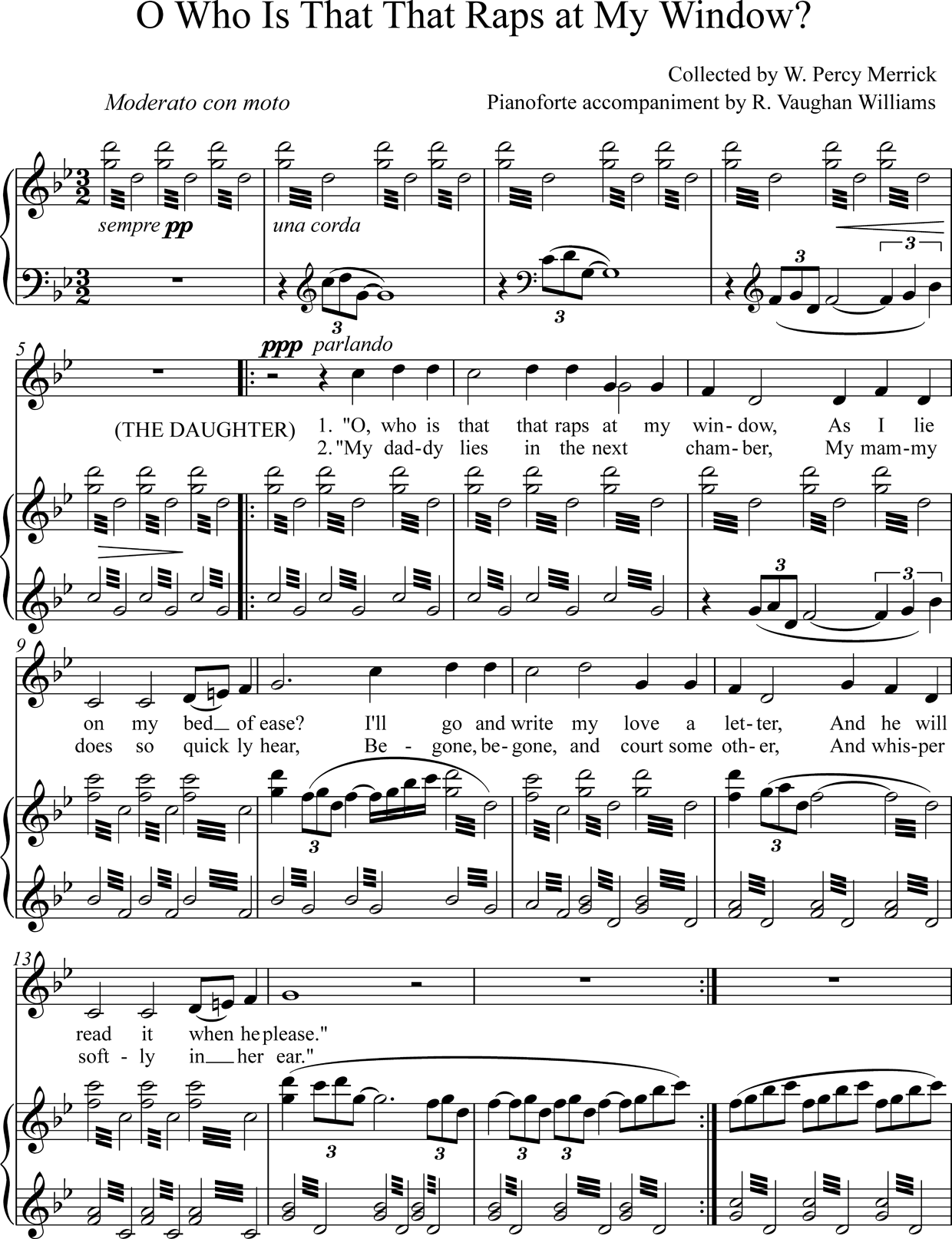

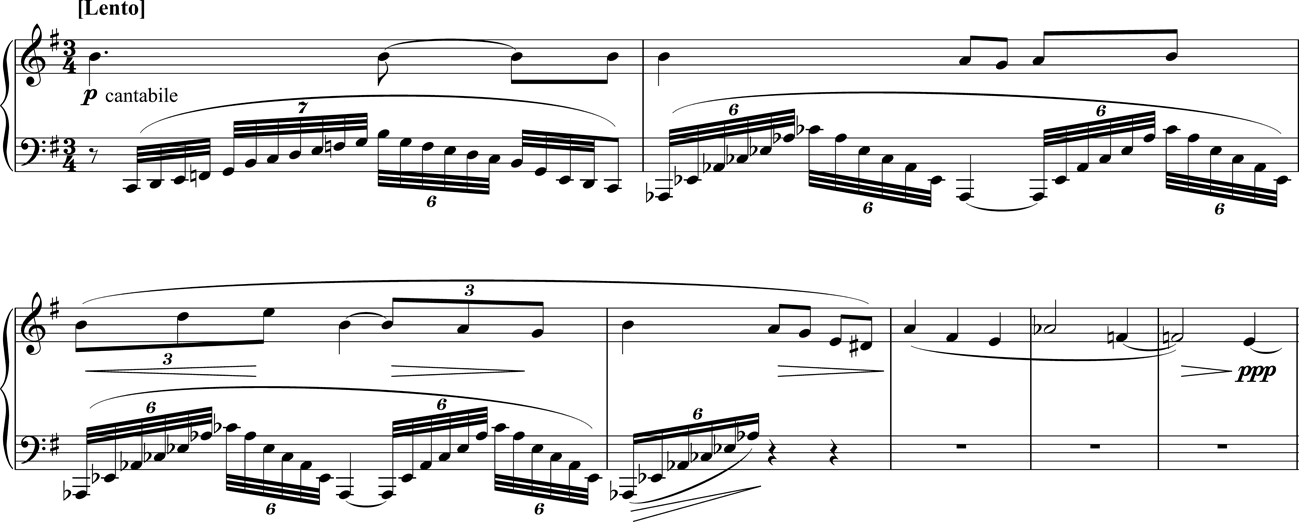

A more monumental tone is evident in the Heroic Elegy and Triumphal Epilogue, which uses the largest orchestral ensemble Vaughan Williams had yet mustered, with triple wind, a large complement of brass, and harps and organ ad libitum (the work was published by Faber Music in 2008 and has now been recorded).6 It is the most obviously impressive of this group of four works, and it certainly received the warmest critical reception.7 There are echoes of Wagner, Sibelius and Tchaikovsky, and several developmental passages call to mind Strauss and Elgar; the brass-heavy final pages in particular, building on earlier fanfare passages, suggest a new level of orchestral ambition. The two movements are separate but share thematic material; they were originally to have formed the second and third parts of a three-movement Symphonic Rhapsody, but it is unclear whether the first movement was even sketched (the title was revived, however, for the later work by that name).8 The relatively unusual choice of B minor as tonic key for the Elegy brings to mind Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, and the first movement of the Russian’s Fourth Symphony may have inspired subsequent tonal motion through a chain of minor thirds, a feature found in several other early works by Vaughan Williams, including the Bucolic Suite and Burley Heath.9 Yet the varied range of influences does not obscure an individual stamp; furthermore, the Triumphal Epilogue contains several striking adumbrations of the later and more consistently individual Vaughan Williams, in particular A Sea Symphony, on which he would begin work fairly soon afterwards. The developmental passages around rehearsal letter R look forward to the Scherzo of the symphony, while the D major melody that launches the Triumphal Epilogue, and returns in grandeur as its peroration (see Ex. 4.1), adumbrates the ‘Token of all brave captains’ theme of the symphony’s first movement. And this latter element has a broader significance: aspiring, gapped D major melodies of this kind would go on to become a staple thematic archetype for Vaughan Williams throughout his career.

Ex. 4.1. Heroic Elegy and Triumphal Epilogue, Epilogue, bars 256–63.

Landscapes with and without figures

As was noted above, the Heroic Elegy and Triumphal Epilogue received positive critical notices, and it was singled out by several critics familiar with other music by the composer as a landmark work confirming his potential.10 But in 1902 Vaughan Williams began to move in new directions, producing over the next five years a series of one-movement pieces that carry programmatic titles specifying particular geographical locations. These works are relatively short, but a number of them seem to have been conceived with the idea of larger multi-movement cycles (in 1903 Vaughan Williams also began work on A Sea Symphony, of which more below).11 Though they all share an intensified interest in modal harmony, combined with more chromatic elements in sometimes experimental ways, the eight pieces divide into two groups according to whether or not they make clear reference to English folksong. This is quoted explicitly, in the form of complete tunes, in the three Norfolk Rhapsodies, and is more loosely evoked in the principal thematic material of In the Fen Country. These four works were the earliest substantial creative fruits of Vaughan Williams’s folksong conversion experience, as it were, of December 1903, when he first encountered this music in a personally compelling manner, and moved beyond scholarly appreciation to active engagement. This found expression not only in composition but in extensive activity as a collector.

The four other works, of which Boldre Wood is now lost and Burley Heath survives only incompletely, were all dubbed ‘Impression’ (the generic designation also of In the Fen Country) and relate to locations in and around the New Forest, the expanse of unenclosed heathland and forest between Southampton and Bournemouth. This was an area that Vaughan Williams knew well, from family holidays and other connections to the area, and he lectured in Bournemouth in 1902.12 The manuscripts for the earliest pair of impressions, Burley Heath and The Solent, indicate that when he began work in 1902 the composer planned a set of four pieces, under the broader title of ‘In the New Forest’; it is not at all clear, however, whether the later Boldre Wood and Harnham Down were originally related to this scheme in any way, or were instead a fresh start at representing this particular geographical locale in music. The Solent and Harnham Down are prefaced by poetic inscriptions, from Philip Marston and Matthew Arnold respectively, but these shed little interpretative light.13 It is a great pity that so many unresolved questions surround these works, as musically they are of considerable interest. As Michael Vaillancourt has noted, they show a new structural compression, harmonic sophistication and subtle attention to orchestral sonority. Though the title ‘Impression’ hints at French influence, more striking in many respects is the anticipation in certain passages in The Solent of the kind of string-writing that the composer would a few years later develop with such distinction and originality in the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. Of course, landscape, and the natural world in general, had a long history of inspiring composers to textural and other kinds of musical innovation, and it is perhaps no surprise that a composer becoming increasingly restless in his search for a style both individual and somehow rooted in a wider national identity should turn to such subject matter.

There is an experimental quality at times in these New Forest works, and the composer’s broader restlessness during this period is reflected in the tally of works left incomplete, or discarded after a single performance, or (more commonly) subjected to multiple revisions. In the latter category is In the Fen Country, which has the distinction of being the composer’s earliest orchestral work to be allowed eventually to form part of his public oeuvre. It was composed initially in 1904, but then subjected to multiple revisions over the next few years, with a final retouching of the orchestration in 1935. The work shares with much of the composer’s music of this period a sometimes awkward combination of Wagnerian or Straussian chromaticism, fleeting echoes of Debussy, and fresher modal perspectives, and at times it relies too heavily on imitation or strained modulations to generate momentum from contemplative musical material. Nevertheless, it contains many compelling and beautiful passages and sustains its sense of musical direction overall. A glowing chordal passage heard at various points, in which high strings answer brass, strikingly anticipates A Pastoral Symphony of some fifteen years later. Although the opening cor anglais solo certainly suggests the kind of generic lonely shepherd heard as far back as Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, the contour of the melody is also undoubtedly shaped by the English folksongs that Vaughan Williams had recently begun to collect, as Elsie Payne has shown.14

A sense of the wide, flat vistas of the Fens, where land, water and sky blur together, is conjured once again in the Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1, the only other orchestral work from the period before the end of 1907, when the composer began his studies with Ravel, to have survived Vaughan Williams’s severe self-criticism. Two further rhapsodies, the three together apparently intended eventually to form a Norfolk Symphony, with the second combining slow movement and scherzo, were eventually deemed unsatisfactory and not performed after 1912.15 The third rhapsody is now lost, but the second survives in a largely complete manuscript and has been recorded.16 All three rhapsodies drew on folksongs collected by the composer in East Anglia during 1905, and were designed in part to bring these tunes to a wider audience, though the composer also published vocal arrangements of a number of them. The rhapsodies are, in fact, the composer’s only orchestral works to present complete folk tunes, with the exception of Five Variants of ‘Dives and Lazarus’ and some folk dance arrangements; indeed, in his later career Vaughan Williams would rarely quote even fragments of specific songs, but rather evolved a melodic language shaped by generic features of English folksong or of certain families of tunes.

The original manuscript of the first rhapsody is unfortunately lost, and so we are unable to reconstruct with any certainty the work as it existed before its publication in 1925, though it seems likely that it was in essentially its final form by the time of a performance in Bournemouth in May 1914. The programme note for the 1906 premiere, however, does indicate that at this date the piece ended rousingly, rather than with the return to the quiet opening stasis that we hear today, and that it originally contained the stirring song ‘Ward the Pirate’, which in the third rhapsody formed the basis of a climactic final section, functioning as a cyclic recall of the opening number.17 The eventual withdrawal of the third rhapsody presumably played a part in the removal of ‘Ward the Pirate’ from the first. The songs that remain in the final version of the first rhapsody are memorable; this is especially true of the ‘The Captain’s Apprentice’, whose elegiac mood opens and closes the work, and to an extent pervades it, despite the boisterous energy of the second main melody, ‘On Board a 98’ (‘A Bold Young Sailor’ is also included). The desolate opening, in which lonely birdcalls keening across a coastal landscape are eventually joined by the more human voice of a solo viola, which weaves an improvisatory solo around the ‘The Captain’s Apprentice’, is truly haunting.18 The rhapsody does not entirely avoid the endemic pitfalls of works of this kind, especially in occasional awkward changes of gear between songs, but it is much more than a medley; Ian Bates has pointed to a number of subtleties of modal treatment in the work, and to various levels of symmetrical structure that suggest a more careful compositional process than is often associated with the term ‘rhapsody’.19 The second rhapsody also begins and ends quietly; slow outer sections, based on the tunes ‘Young Henry the Poacher’ and ‘All on Spurn Point’, frame a central scherzo that focuses on ‘The Saucy Bold Robber’. Though the third rhapsody is lost, reviews suggest that it was essentially a quick march with trio. Why Vaughan Williams withdrew all but the first rhapsody must remain a matter of speculation, though the second rhapsody does not seem to cohere as convincingly as the first (to this listener, at least).

Ravel and after

Vaughan Williams produced an impressive number of orchestral works in the period between 1902 and 1907, but he clearly remained deeply dissatisfied with his achievements (not only in the orchestral field, it should be noted), and it was at the end of 1907 that he travelled to Paris to begin his work with Maurice Ravel. As Byron Adams has discussed in Chapter 2 of this volume, despite a frustrating lack of concrete evidence as to the exact scope of his studies with Ravel, the time he spent with his younger French colleague was clearly transformative, at least judging by the compositional fruit of the next few years. Though this did not manifest itself immediately in the form of independent orchestral works, the substantial score (albeit for a 24-piece orchestra) that the composer wrote in 1909 for Aristophanes’ play The Wasps does show the impact of Ravel’s instruction in ‘how to orchestrate in points of colour rather than in lines’, as Vaughan Williams would later describe his teacher’s primary lesson.20 The suite that Vaughan Williams later drew from this incidental music, scored for a rather larger ensemble than the original, went on to be a successful concert work, and at its publication in 1914 was in fact the first of his orchestral works to appear in print; the Overture proved particularly popular, and in 1925 it was one of the two works that the composer chose for his first venture into the recording studio.21

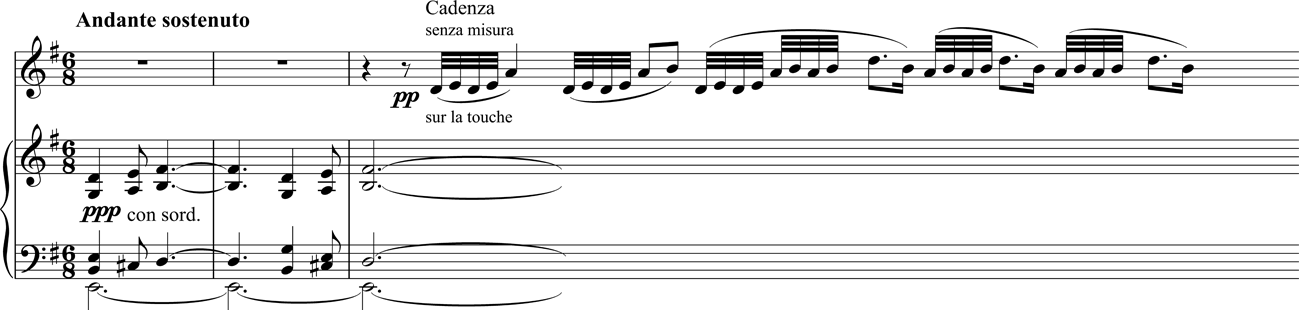

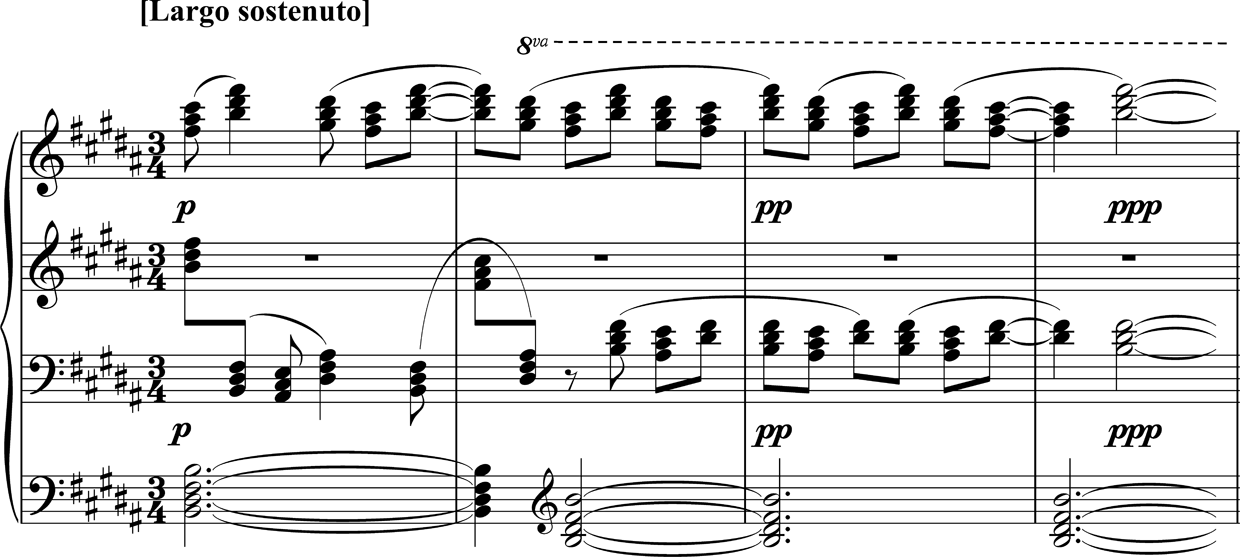

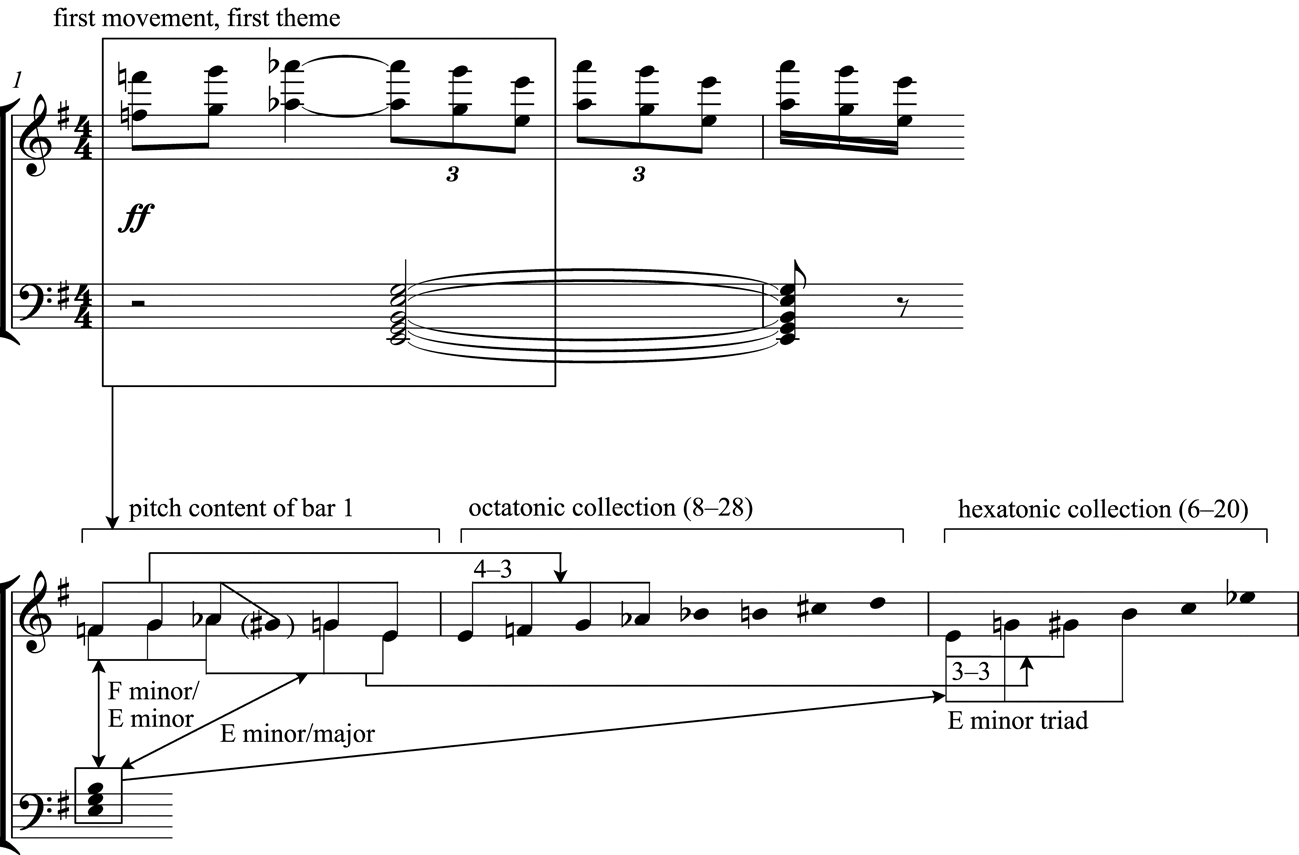

But 1910 would bring what were ultimately more important landmarks. The autumn of that year saw within just over a month the premieres of two crucial works: the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis at the Three Choirs Festival in September, and A Sea Symphony at the Leeds Festival in October, both conducted by the composer. At the end of 1911 Vaughan Williams wrote in a letter to Ernest Farrar that the Fantasia ‘[is] the best thing I have done’,22 and most commentators have endorsed that judgement. Indeed, its stature remains impressive even in the light of the composer’s later accomplishments. The Fantasia is Vaughan Williams’s most widely performed and recorded major work, achieving in particular an international currency that has so far eluded most of his other music – though it was some time before the work took hold in this way and even in England it would not become a staple until the 1930s. It has been widely regarded as the first work in which Vaughan Williams fully realized the individual stylistic synthesis that would form the basis of his mature compositional output. He apparently discovered Tallis’s tune for Psalm 2 during work on The English Hymnal (1904–6), for which Vaughan Williams adapted it as ‘When Rising from the Bed of Death’. Nathaniel Lew has plausibly suggested that the idea of using the tune as the basis of a longer work may have originated in 1906, in connection with the Reigate pageant based on John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (the composer’s first engagement with the Bunyan work, which went on to become a lifelong fascination, of course).23 This remarkable Phrygian-mode tune is certainly richly suggestive in terms of harmonic, rhythmic and other subtleties of construction, as a number of commentators have noted;24 yet the process of revelation that Vaughan Williams drew from it nevertheless constitutes an extraordinary imaginative feat, for which the word ‘visionary’ is for once entirely free of hyperbole. Particularly striking is the manner in which a closed thematic model is daringly broken down to a condition of almost complete quietus, and then gradually reanimated, eventually culminating in a luminous climax. The climax itself, a passionate homorhythmic declamation, confirms the fact that harmonically the work is a profoundly original meditation on the power of unadorned triads: without a single appoggiatura, but instead juxtaposing triads riven by false relations that evoke sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English music, Vaughan Williams creates a climax as intense in its way as anything in Wagner or Tchaikovsky (see Ex. 4.2).

Ex. 4.2. Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, bars Q.17–21.

The rhythmic unison of the climax is especially dramatic because of the array of multifaceted textures that has preceded it. Indeed, perhaps the most immediately striking (and most influential) feature of the work is its new and spacious approach to string sonority. The composer describes the ensemble as ‘double stringed orchestra with solo quartet’. Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro of 1904 had employed the concerto-grosso-like contrast of a quartet with a larger body of strings, but Vaughan Williams adds an intermediary second orchestra, essentially a double-quartet with double-bass added (the two orchestras are thereby of unequal size). The second orchestra is to be placed apart from the first ‘if possible’. These resources are exploited to the full, particularly to create spatially suggestive effects of light and shadow, with wide registral expanses evoking a vertical dimension that complements the recessed textural perspectives. This aspect of the work has understandably been linked by some writers to the experience of being within a Gothic cathedral such as that at Gloucester, where the work was premiered (though there is no direct evidence that the composer was thinking in these terms). Choral antiphony has also been suggested as a model, but the disparity in the size of the ensembles militates against this analogy, at least in terms of true double-choir music; the contrasts between different organ manuals offer a closer parallel. More precise architectural and spatial metaphors underpin the most recent re-examination of the work, in which Allan Atlas suggests that the structure of Gloucester Cathedral may have helped suggest a tension between two different proportional schemes in the Fantasia, between what Atlas identifies as a quarter-half-quarter (or 1:2:1) shape, and various manifestations of the so-called ‘Golden Section’ proportion.25 Any spatial scheme has nonetheless to take into account (as does Atlas) the strong narrative thrust that develops during the work. Anthony Pople has conceived of this in part as an evolutionary historical account of musical style, invoking plainsong, folksong and organum before arriving at Tallis’s polyphony.26 As Pople notes, this particular narrative weakens as the work progresses and Vaughan Williams’s own modern voice takes over; nevertheless, this is the composer’s most self-consciously historicizing work up to this point in his career. One earlier model that Pople essentially dismisses, however, is that of the one-movement Jacobean fantasy, as promoted during this period by the wealthy musical amateur Walter Willson Cobbett through his prize for chamber music: as Pople points out, Vaughan Williams violates a number of the requirements set out by Cobbett.27 Both Atlas and Pople take into account important differences between the original version of the work and the published score of 1921; by the time the latter appeared the composer had subjected the Fantasia to at least two rounds of revision, cutting a total of thirty-three bars from the score, which included a second statement of Tallis’s theme at the end of the work where now there is only one.

Three symphonies

Though the Tallis Fantasia would ultimately eclipse it in fame, it was A Sea Symphony, for orchestra, chorus and soprano and baritone soloists, that established Vaughan Williams as a composer of large-scale works. It was first performed on 12 October 1910 – Vaughan Williams’s thirty-eighth birthday – at the Leeds Festival, conducted by the composer (later in the programme Rachmaninov played his Piano Concerto No. 2). Its long gestation began in 1903 and thus straddles several important junctures in Vaughan Williams’s early development. This is reflected in a disparate range of styles and influences, the latter including Brahms (Ein deutsches Requiem in particular), Parry, Stanford, Elgar, Wagner, Tchaikovsky and (to a lesser extent) Debussy and Ravel, along with folksong and hints of Tudor music. Though many aspects of its compositional chronology remain obscure, we do know that a short-score draft was complete by 1906; at this point the work contained an additional movement, ‘The Steersman’, placed between the Scherzo and the Finale.28

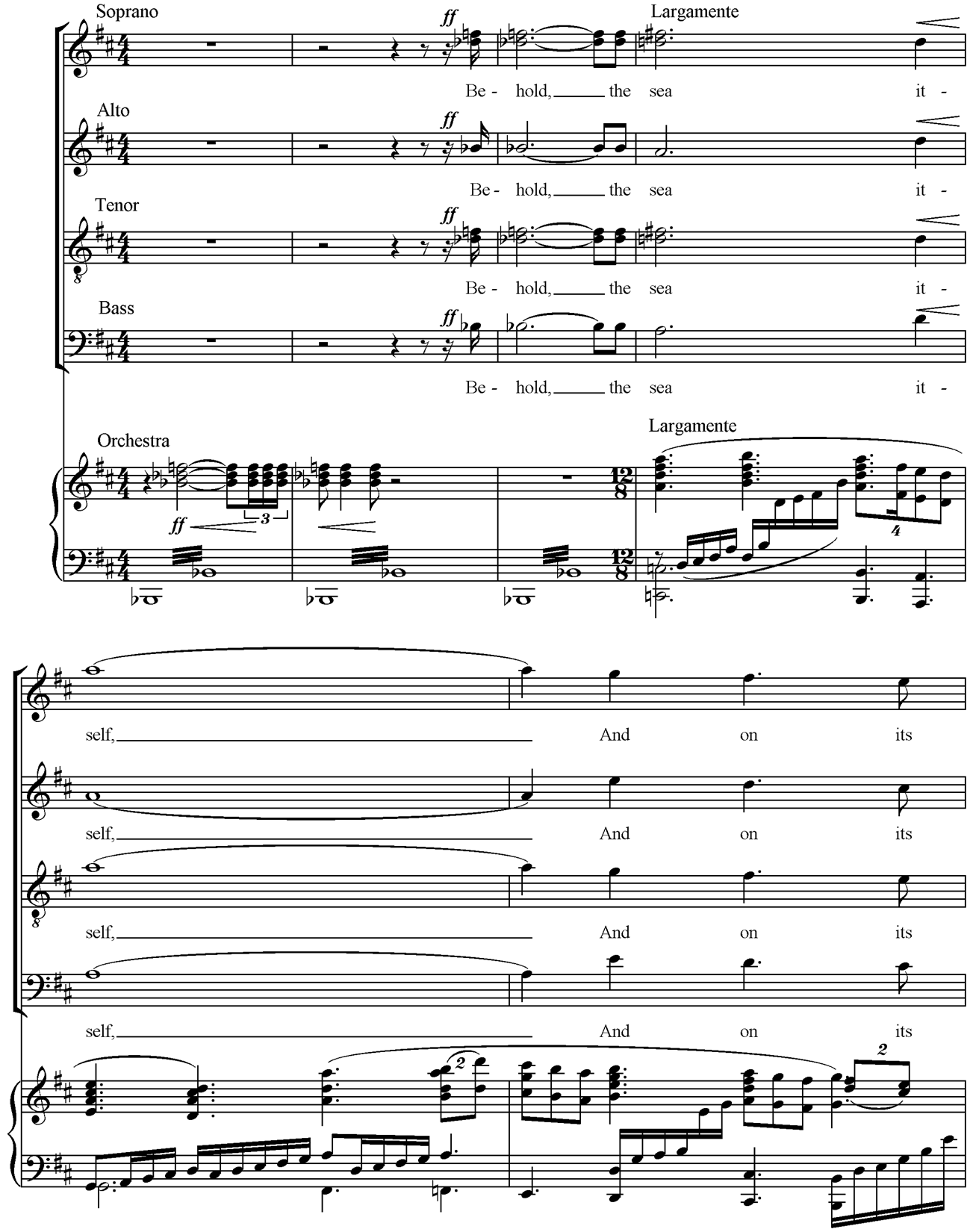

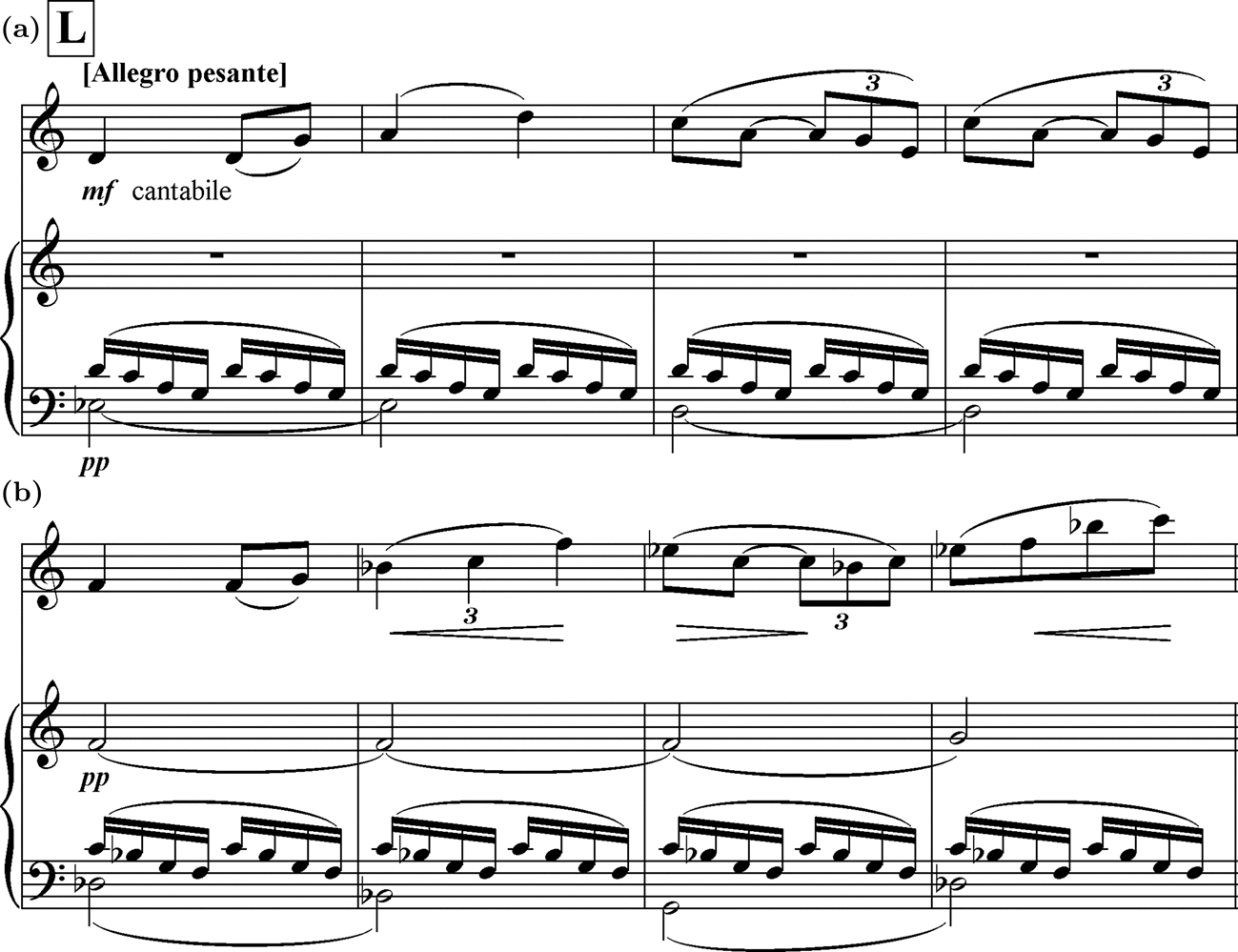

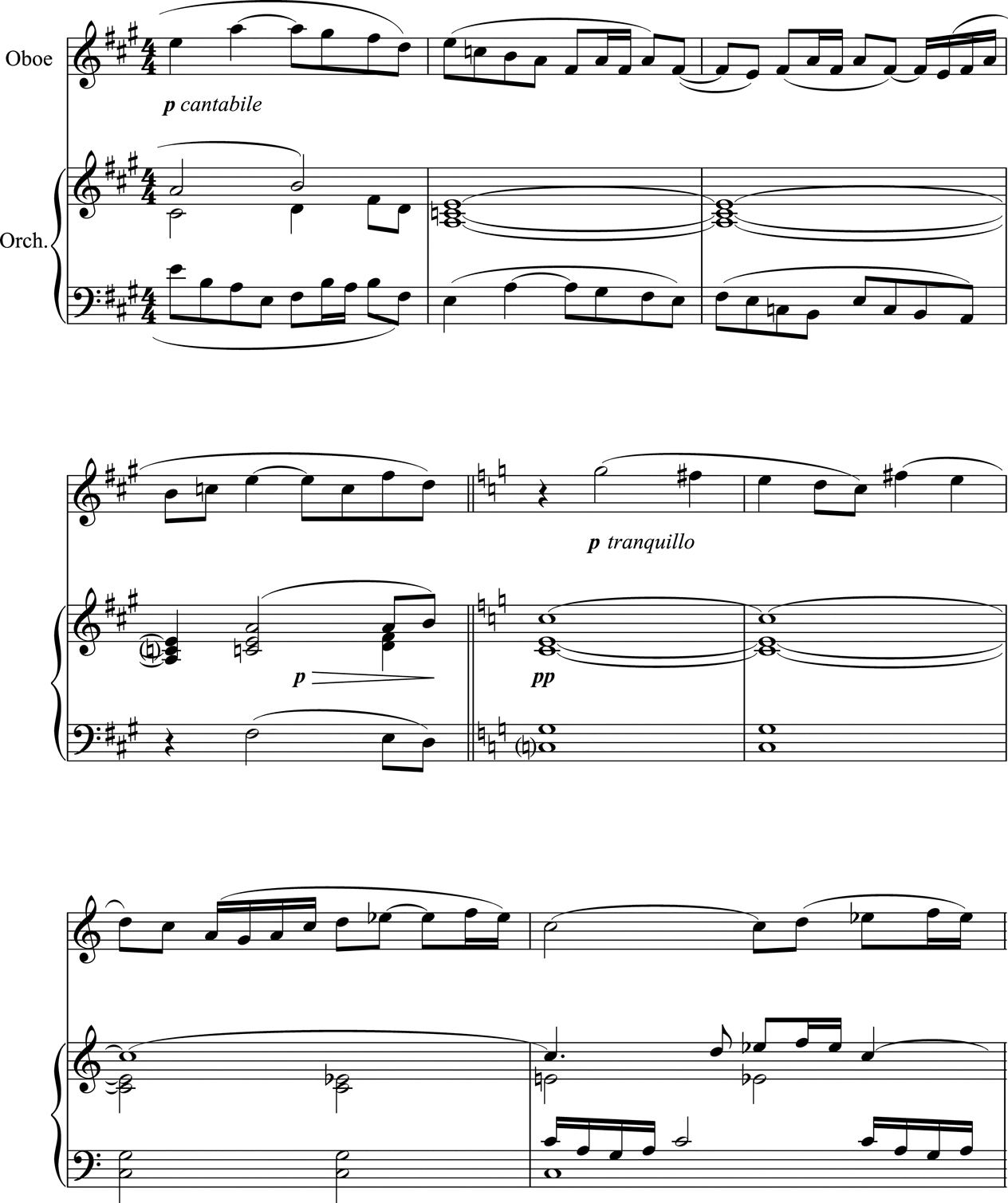

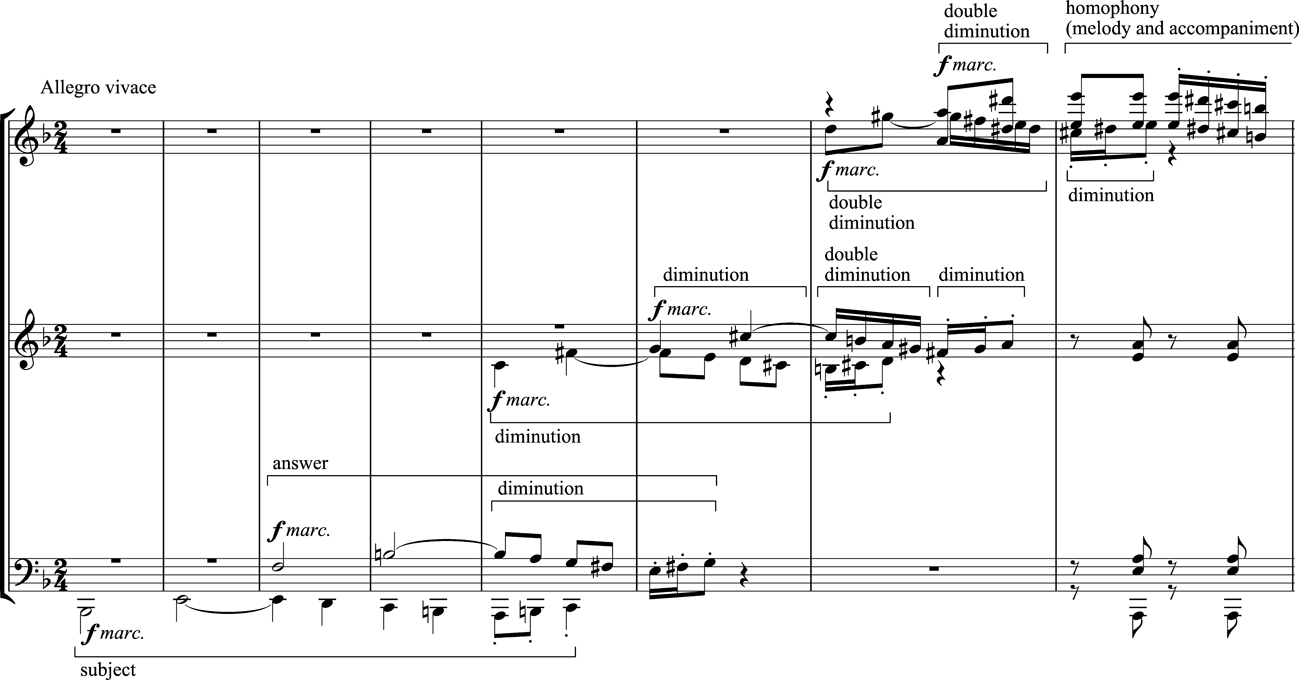

Vaughan Williams had begun to set Walt Whitman (1819–92) in 1902 and would remain preoccupied with his work for the next decade, and to some degree for the rest of his life; Stanford and Charles Wood had already made notable Whitman settings before him, but it was Vaughan Williams in the years before the First World War who would engage most deeply with the American’s transcendent and universalist vision of the modern world.29 In A Sea Symphony Whitman inspired a work of extraordinary originality and ambition. With a running time of around an hour and twenty minutes, it must surely have been the longest British symphony written to date. Its status as a true symphony has been disputed, and it is certainly a hybrid work in terms of genre, combining elements of symphony, oratorio and cantata. It is more fully choral than, say, Mahler’s symphonies with voices, in that the choir or soloists are heard virtually throughout; this necessarily dilutes its ability to pursue some more traditionally symphonic processes, particularly in developmental sections, and the form is sometimes episodic, especially in the massive finale. Yet the tonal and thematic strategies across the work ensure that it is much more than a loose succession of character pieces, and the outer movements in particular generate passages of gripping symphonic momentum. The overall tonal scheme of the four movements, essentially D–E–G–E♭, is unconventional, but hardly unprecedented against the background of Mahler’s ‘progressive tonality’.30 And despite the stylistic disparities, there are moments of dazzling audacity. The exhortation of ‘Behold, the sea itself’ that launches the first movement, ‘A Song for All Seas, All Ships’, is one of these: its dramatic shift from B♭ minor to D major harmony at the word ‘sea’ conjures a visceral sense of space opening up before us, and surely constitutes one of the great opening gestures of musical history31 – a gesture intensified further at its second appearance by the unexpected addition of a C bass note under the D harmony (see Ex. 4.3). In the finale, ‘The Explorers’, the build-up to the prophetic moment of revelation, when the ‘Son of God shall come singing his songs’, is similarly electrifying; the rugged diatonic dissonances here are original and bracing, with the explosive urgency of the bass line pushing it ahead of the upper-voice harmonies, a kind of disjunction that might almost suggest the influence of early Stravinsky, were it not for the fact that it was composed before either The Firebird or Petrushka. The hushed and ambiguous ending, ostensibly in E♭ but with melodic emphasis on C and a low G in the bass undermining the stability of the tonality, is also striking.

Ex. 4.3. A Sea Symphony, ‘A Song for All Seas, All Ships’, bars 42–50.

The enormous last movement is certainly sui generis, and here Vaughan Williams’s reach exceeds his grasp (even if the listener may remain grateful that he reached that far); despite certain recurring thematic and tonal elements that provide landmarks in the soul’s cosmic journey of exploration, the structure remains relatively loose. The second

and third movements are more obviously in line with symphonic expectations: ‘On the Beach at Night, Alone’ is a slow ternary form, and the third movement, ‘The Waves’, is a scherzo. The third movement is the most impressionistic part of the symphony, replete with Debussy-like whole-tone passages among other elements. For the most part, however, the sea functions throughout the symphony as a spiritual metaphor rather than pictorial inspiration, reflecting the poet’s own perspective. The sea was a common theme in British music at this time, with obvious nationalistic resonance, but Whitman’s perspective is a universal one, reflecting his all-encompassing post-Christian sense of spiritual quest, his embrace of both the mystical and the mundane, and his visionary conception of global democracy. Such considerations, along with the poet’s highly original and fluid approach to metre and diction, clearly influenced Vaughan Williams’s choice of texts for the symphony; there is an almost palpable sense in a number of passages of an artist discovering the full extent of his powers for the first time, as Whitman’s exaltation becomes the composer’s own.

Though boldly innovative in a number of ways, A London Symphony is easier to place than its predecessor within the evolution of the symphonic genre since Beethoven, and it represents the culmination of Vaughan Williams’s development as an orchestral composer before World War I. According to Vaughan Williams the work began as sketches for a symphonic poem about London,32 but while it has important programmatic associations, these are subordinate to more traditional elements of musical coherence, including a unified tonal plan and cyclic returns of material in different movements. Nevertheless, one specific programmatic impetus was revealed in 1957, when, in correspondence about the symphony with Michael Kennedy, the composer remarked laconically: ‘For actual coda see end of Wells’s Tono-Bungay’.33 This appears to refer to the final chapter of H. G. Wells’s novel, which traces a journey taken by the protagonist down the River Thames, from some way upstream to the open sea, a progress that is framed in both geographical and historical terms, and which Wells describes as the three movements of ‘a London symphony’. Tono-Bungay was first published in 1908; I have argued elsewhere that it was most likely the initial spur for the symphony, and surely influenced more than just its ending.34 That said, it is not clear exactly when Vaughan Williams conceived of an orchestral work related to London, or made his initial sketches, though the symphony was apparently underway by mid-1911, and finished by the end of 1913.

The symphony made a strong impression at its premiere in March 1914, and confirmed for many Vaughan Williams’s position as the leading figure in the cohort of British composers who had emerged since 1900. Though a more traditional work than A Sea Symphony, it is scarcely less ambitious or original, and lasted almost an hour in the version performed in 1914. Its full impact, however, was initially stifled by the outbreak of war, and it would not be heard in London again until 1918. Between 1918 and 1920, when the work was first published, the composer made draconian cuts, amounting to roughly 25–30 per cent of the original in terms of playing time; additional, though less severe, surgery would be performed before a revised version of the score appeared in 1936.35 Vaughan Williams apparently agreed with those critics of the original version who had, despite generally positive reactions, expressed concerns about its length and prolixity. Of the four movements the first remained virtually intact in the revisions, but the slow second movement, the scherzo (which lost an extended subsidiary section), the finale and the long Epilogue that flows out of the finale were all heavily cut.

But the bold ambition of the work is represented more by breadth and depth of musical complexity than by sheer length, and these dimensions remain impressive even in the revised versions. Vaughan Williams created in this work a Mahlerian, at times almost Ivesian, range of stylistic and social reference.36 Though the composer’s own musical personality sounds strongly throughout, the clear imprint of Debussy, Wagner and even Stravinsky can he heard at various points. More significant in programmatic terms, however, are references to the urban street soundscape, including not only actual music – from modern ragtime inflections in the first movement and barrel-organ and harmonica in the scherzo, to the implicitly pre-modern lavender-seller’s cry of the second movement – but also ambient sound, as it were, in the form of hansom-cab jingles, the chimes of Big Ben, or what seem to be the metallic shrieks and rumbles of trams and trains. And although the detail is intimately particular at times, the perspective is nevertheless implicitly global, not just local or national. The London that Vaughan Williams portrays, as centre of the British empire, is the capital of the modern world, a dimension emphasized by its status as a major port, intimately connected with the boundless sea. Nature, humanity of all classes, the technological challenges of modernity, and relationships with a multi-layered past are brought together in a heady mix. But they are not simply juxtaposed: Vaughan Williams confronts apparently irreconcilable contrasts and conflicts, but also seeks to integrate and reconcile. In this respect the work stands directly in the tradition of the Beethovenian symphonic paradigm, and indeed the grinding semitone dissonances at the beginning of the allegro section of the first movement, which are then taken up again in the finale, seem to evoke directly the opening of the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. A sense of strain, particularly in the last movement, is only fitting: if the symphony seems on the verge of collapsing under its own weight and self-contradiction at times, so did the city, nation and empire that it represents, riven as they were at this time by social and political turmoil (most notably widespread strikes and growing crisis in Ireland).

Programmatic interpretations of this kind must for the most part remain conjectural, since Vaughan Williams himself was ambivalent and inconsistent in shedding light on this aspect of the symphony (in common with most composers of programme music, it must be said). In 1925 he did tentatively acknowledge that the allegro of the first movement represented ‘the noise and hurry of London, with always underlying calm’, and that one might think of the slow movement in terms of Bloomsbury Square on a November afternoon, and of the Scherzo (subtitled ‘Nocturne’) as Westminster Embankment at night. He offered no such clues to the finale, however, or to the Epilogue into which the finale leads without a break. Nevertheless, the Epilogue, which is based on the slow introduction to the symphony, is clearly the ‘coda’ the composer mentions in reference to Tono-Bungay; the Wells connection confirms what is already strongly hinted at in the musical material itself, namely that both the beginning and the ending of the symphony evoke the Thames, and eventually the sea: the speed and turmoil of urban human modernity are thus framed by a mystical and implicitly timeless natural world. More broadly, Wells’s novel portrays a society in decay, and a vision of London (one common at the time) as a vast and uncontrollable – almost unrepresentable – cancer of modern society, a mindlessly churning cauldron of capitalism engulfing its environs and its people. Though Vaughan Williams’s view was surely not quite as bleak, there are many threatening shadows in the symphony, even moments suggesting nightmare, especially in the last movement and in a number of passages cut during the revision process. On the whole, the symphony darkens as it progresses, and the finale negates any notion of the kind of triumphal peroration beloved of many nineteenth-century symphonists, on the model of Beethoven’s Fifth and Ninth symphonies (though of course Brahms’s Fourth, Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique and Mahler’s Ninth all offered powerful precedents for such negation). The work is certainly much darker than Elgar’s portrait of London in his Cockaigne overture of 1901, which is for the most part by turns exuberant and tender.37

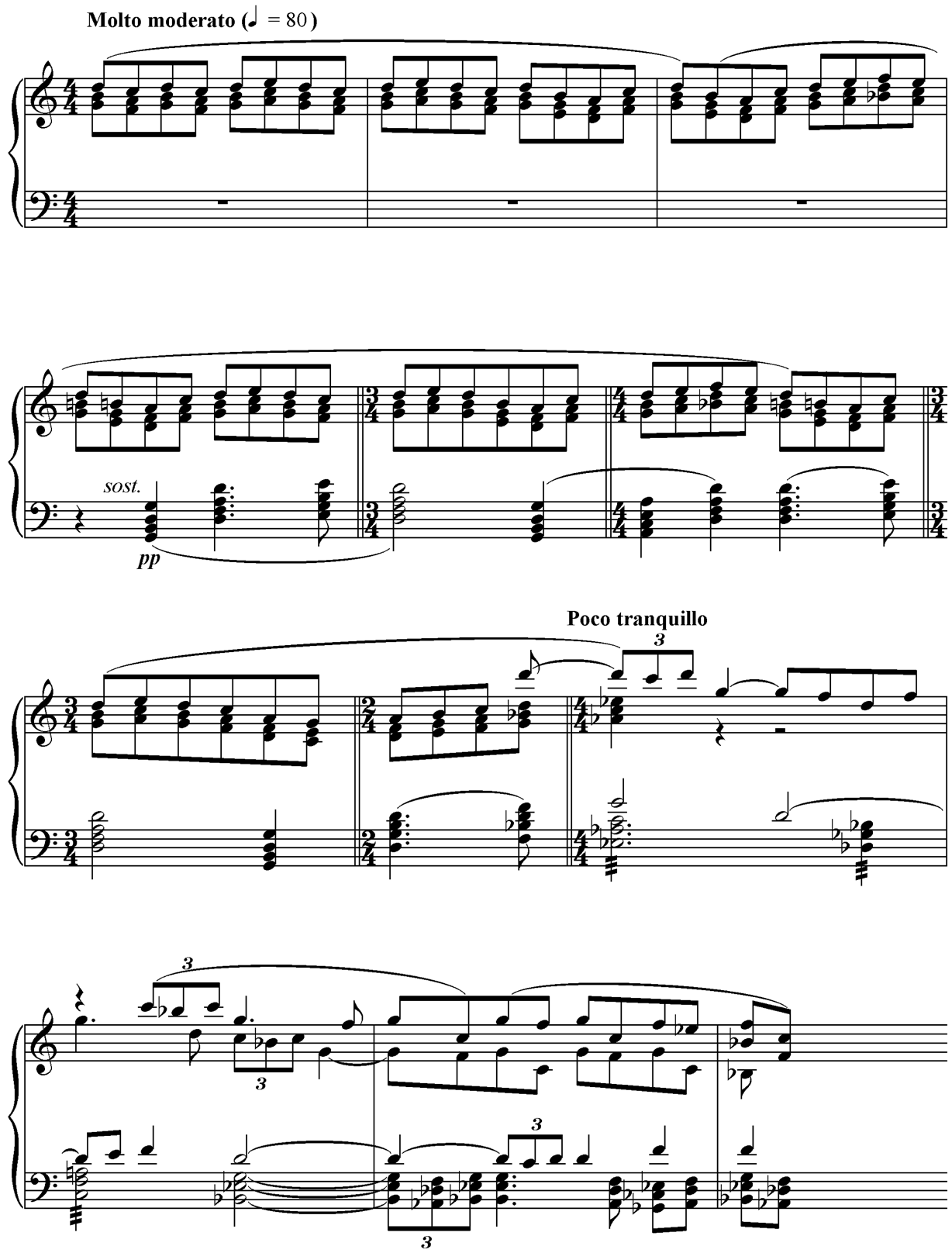

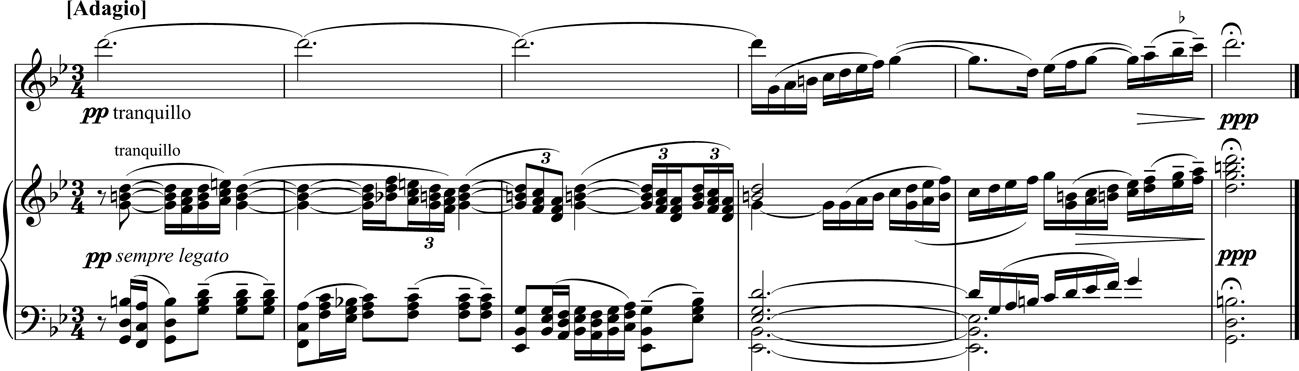

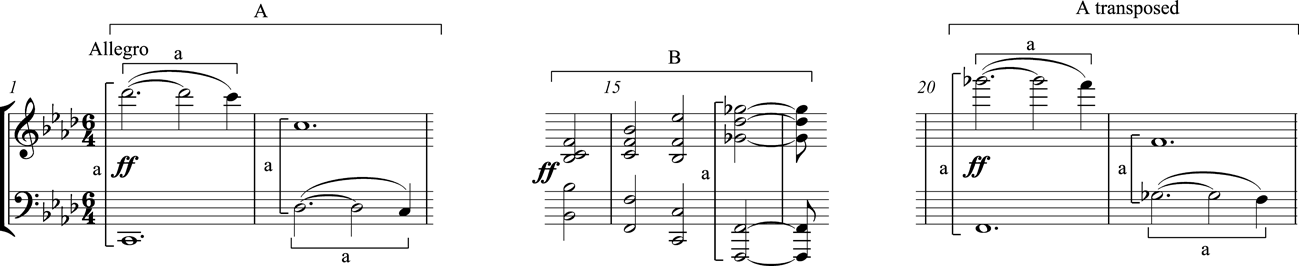

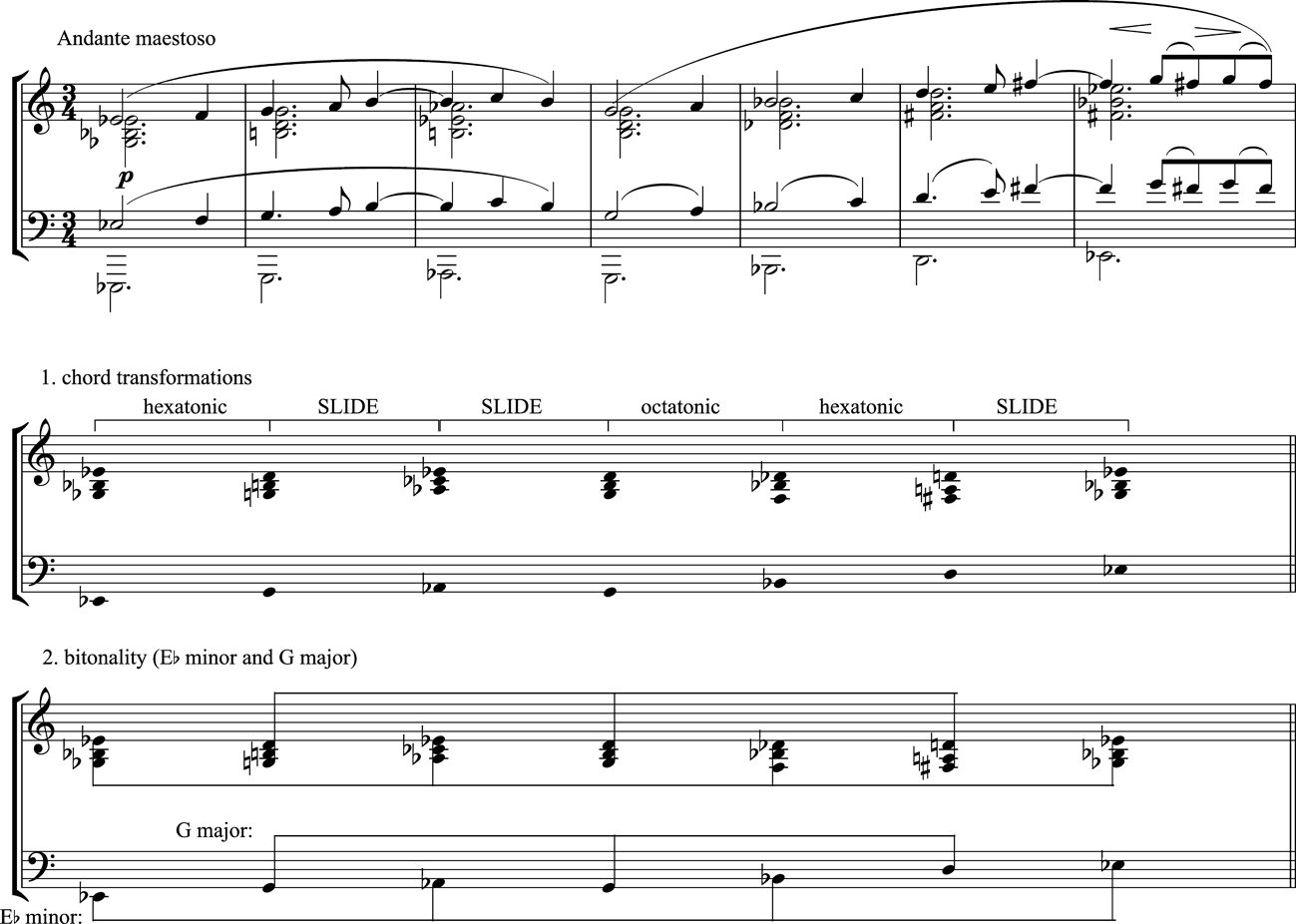

Though the musical means by which Vaughan Williams expresses diversity and conflict are often original, the techniques by which he imposes coherence are for the most part well established in the symphonic tradition. Thus the interaction of tonal, modal and chromatic elements generates both dissonant conflicts, and the framework by which these are eventually absorbed into the overall G major tonality of the symphony.38 E♭ emerges early on as a chromatic alteration of the sixth degree of G, in the form of a keening D–E♭ melodic figure in the slow introduction, and the interaction of scale-degrees 5 and 6, in a number of different tonal and modal contexts, looms large throughout the symphony. At the beginning of the allegro section of the first movement the D–E♭ semitone is verticalized, as a shrill chromatic progression of parallel triads in the upper parts clashes with a thunderous bass line, suggesting the threatening and inhuman dimension of modern city life (see Ex. 4.4).

Ex. 4.4. A London Symphony, first movement, bars 34–44, transition from slow introduction to Allegro.

The bifurcation of the texture here into aggressively independent layers constitutes one of the most conspicuously modernist elements of the score, with clear parallels in the music of Stravinsky and Ives, and a powerful representation of the colliding simultaneities of urban experience. Such heterogeneity takes on a more positive aspect with the populist high spirits of the second-group material, which eventually brings the first movement to a rousing conclusion – a rarity in this composer’s symphonies. But although this mood will return in parts of the deft Scherzo (especially the trio, which echoes Petrushka), the remainder of the symphony is mostly much darker. Twilit melancholy dominates the ternary second movement, and after the Scherzo itself burns out to end in ominous darkness, the finale embarks on an epic and ultimately tragic journey.39 It is tempting to interpret this whole movement, not just the Epilogue into which it eventually leads, in terms of Wells’s Thames progress, which travels through London’s history as well as its geography; a solemn march gives way to more turbulent material, the hectic striving of which fails to achieve closure, and eventually collapses into a return of the opening of the first movement allegro, before giving way to the Epilogue. The niente ending echoes that of A Sea Symphony, and despite its attempt to absorb the symphony’s residual tonal conflicts, it offers more dissolution than resolution. As was suggested above, if the finale seems to strain too hard, and to fall short of the expectations and responsibilities generated by the preceding movements, such qualified failure is not inappropriate as a metaphor for the city and empire that inspired it – it may indeed have been inevitable, given the scale of the task that Vaughan Williams set himself in this work. The composer nevertheless retained an attachment to the symphony throughout his later life, and he conducted it more often than any of his other works.

Vaughan Williams made his first cuts to A London Symphony while on leave from active service in 1918 (he had enlisted in 1914). Though not obviously incapacitated, the composer was deeply marked by the war, not least through the loss of younger friends – most notably George Butterworth, to whom A London Symphony was dedicated upon publication. It is tempting to relate the removal of some of the work’s most apparently subjective passages to the impact of war, representing perhaps a search for some objective, even stoical distance from a pre-war world irrevocably lost. Whether or not this was the case, such objectivity and emotional restraint is a striking feature of the composer’s next symphony, made all the more telling there by isolated outbursts of anguish. A Pastoral Symphony was begun in 1916 and completed in 1921; it was the first major work that the composer completed after demobilization, and its unveiling in London in January 1922 was Vaughan Williams’s first major premiere of the post-war period.

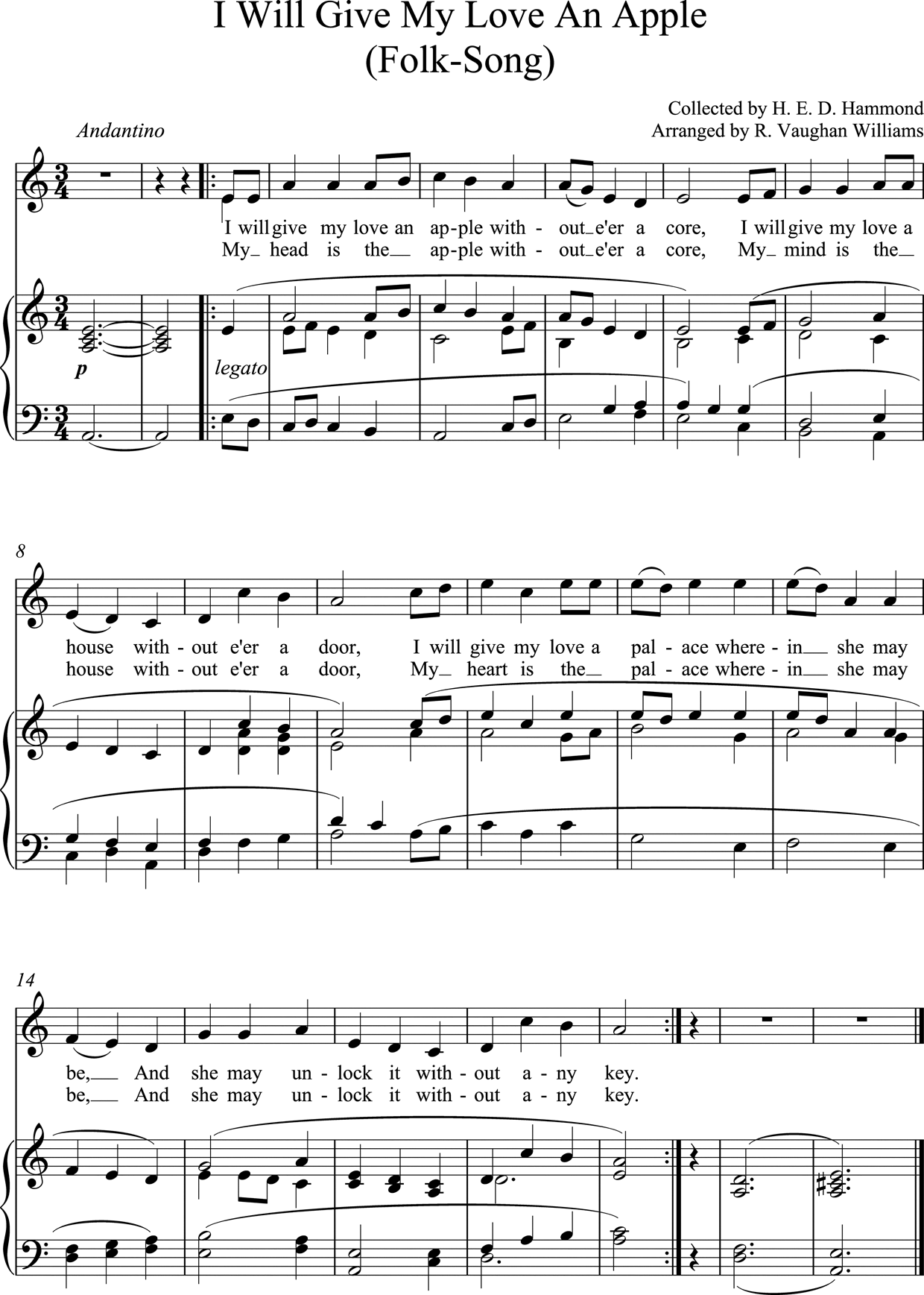

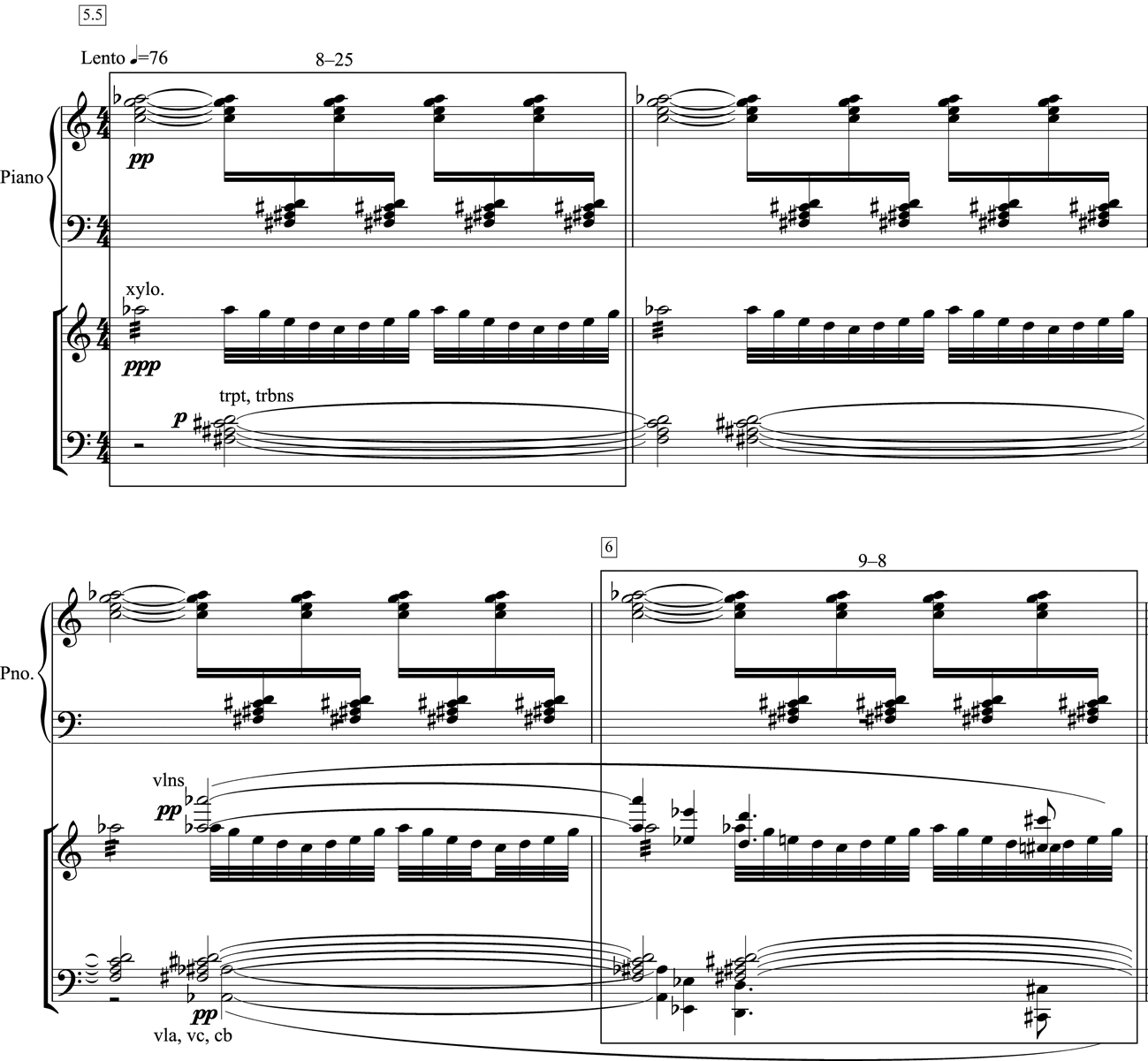

A Pastoral Symphony may lay claim to have been the composer’s most misunderstood work, at least during his lifetime. While its reception cannot detain us here, insensitive critical reactions early on, including from some of the composer’s friends, did much to forge the persistent image, which has only in recent years finally weakened its hold, of Vaughan Williams as a purveyor of insular pastoral nostalgia and meandering rhapsody. The composer himself was perhaps partly to blame (though his reticence was understandable), in that he failed to make clear until much later that the landscape evoked in the work was primarily that of wartime northern France, not the idyllic English vistas assumed by many commentators.40 Yet a degree of musical incomprehension was understandable, not least on account of the genre expectations engaged by the work’s title. Despite its imaginative orchestration – the deftly shifting and melding planes of sonority indicate a new and entirely individual absorption of the example of Debussy and Ravel – the symphony largely eschews traditional symphonic rhetoric. It is subdued in dynamic level for the most part, and employs almost unremittingly slow or slowish tempi; even the Scherzo has a relatively heavy tread for a movement of this kind.

In terms of deeper levels of construction, however, A Pastoral Symphony is in fact the composer’s most rigorously disciplined symphony up to this point in his career. Several recent commentators have demonstrated the tightly knit motivic and formal coherence that underlies the apparently rhapsodic surface of the music; out of melodic material steeped in English folksong yet involving no direct quotation, the composer weaves a subtly compelling and evolving symphonic narrative.41 Like its metropolitan predecessor, the symphony takes G as its fundamental point of departure (though in this case it will not return to end there); through subtle modal interplay, and the drawing-out of the implications of parallel triadic harmonization – a debt to the ‘Nuages’ movement of Debussy’s orchestral Nocturnes is evident at the opening of the symphony – the composer introduces tonal tensions that impel the music forward (see Ex. 4.5).

Ex. 4.5. A Pastoral Symphony, first movement, bars 1–12.

A sense of teleological trajectory, in both the melodic and tonal dimensions, is pursued across the course of the work, even if it goes underground at times, as it were. An important element in this is the inconclusive ending of the first movement, which leaves unresolved the tension between G and C♯ opened up early on in the movement, a tension bound up with the prominent role played by A major as a subsidiary tonal centre in the rotational sonata form.42 In the finale it is D major that emerges as the strongest point of tonal arrival, and a belated resolution of earlier tensions. This coincides with a melodic fulfilment, in that for the first time in the symphony a fully fledged, rounded melodic statement is allowed to reach convincing closure. And yet this sense of arrival and completion is ultimately frustrated, in that the wordless and unaccompanied soprano solo that began the movement returns unchanged at the end, leaving the symphony floating ambiguously on an unharmonized A. The soprano solo is one of two elements in the symphony that seem to reach most obviously out towards a more programmatic level of meaning. It is not difficult to hear in wordless female keening a lament for the war dead; yet there is a remote and ritualized quality to the expression that might suggest instead a natural world oblivious to human suffering. The cadenza for natural trumpet in the second movement has a much clearer significance: it was suggested to the composer during the war by hearing an army bugler practise, and its realistic but gentle evocation of wrong notes has an almost unbearable poignancy – no surprise, perhaps, that the symphony flares into one of its rare moments of protesting anguish immediately following the cadenza. Michael Kennedy is surely right to argue that this symphony constitutes Vaughan Williams’s ‘war requiem’.43

In June 1922, a few months before his fiftieth birthday, Vaughan Williams made his first trip to the United States, having been invited to conduct the American premiere of A Pastoral Symphony at the Norfolk Music Festival in Connecticut, where Sibelius had premiered his tone poem The Oceanides in 1912. The invitation was probably made on the strength of A London Symphony, which was introduced to America in New York at the end of 1920 and was heard with some frequency there during the decade that followed. By the mid-1920s, Vaughan Williams had established himself as an orchestral composer of international standing. Through more than two decades of prolific, yet intensely self-critical, composition (and revision), he had succeeded in making the orchestra, that heavily freighted flagship of nineteenth-century musical culture, a flexible vehicle for his own profoundly original musical visions, including three extraordinarily contrasting symphonies. What no one could have predicted in 1922, however, is that this was just the beginning: that Vaughan Williams would go on to write six more symphonies that would help ensure the continued vitality and relevance of the genre for a tumultuous century and beyond.

Notes

1 Dates of composition and publication throughout this chapter are taken from KC except where otherwise indicated.

2 See , ‘The Symphony in Britain: Guardianship and Renewal’, in (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Symphony (Cambridge University Press, 2013), 376–95at 378–9.

3 Writing after the Second World War, recalled a performance of the Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1 in Berlin on 5 December 1906, conducted by Walter Meyrowitz; though I have found no other record of the event, if it took place it was surely the first performance outside Britain of any of Vaughan Williams’s orchestral works, and quite possibly of any music by the composer, as Foss suggests: see , Ralph Vaughan Williams: A Study (London: George G. Harrap & Co., 1950), 111, n.1.

4 Michael Vaillancourt, ‘Coming of Age: The Earliest Orchestral Music of Ralph Vaughan Williams’, VWS, 23–46 at 33–6.

5 ‘Musical Autobiography’, in Foss, Vaughan Williams, 18–38, at 34; see also Chapter 2 of the present volume. Vaughan Williams gives Reference Vaughan Williams1908 as the year in which he sought out Ravel; it was actually 1907, though most of their work together took place early in Reference Vaughan Williams1908.

6 By the BBC Concert Orchestra, conducted by John Wilson, on the Dutton Laboratories label, CDLX 7237[02], released in 2010.

7 See Vaillancourt, ‘Coming of Age’, 24–5, and KW, 55–7.

8 The inscription that heads the score, ‘Terrible as an army with banners’, is taken from the Song of Solomon, 6:10; its exact significance here, beyond reinforcing the general connotations of saluting a dead hero suggested by the work’s title, remains obscure.

9 Andrew Herbert discusses a broader influence of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony on the genesis of the first movement of A Sea Symphony: see ‘The Genesis of ’s Sea Symphony: A Study of the Preliminary Material’, PhD thesis, University of Birmingham, 1998, vol. i, 83–4.

10 As Vaillancourt points out, early praise for Vaughan Williams centred on his orchestral compositions, rather than the vocal music which later commentators would emphasize – in large part, no doubt, because so many of the orchestral works were subsequently withdrawn. The composer himself emphasized orchestral compositions when asked for information on his works by the critic Edwin Evans in 1903: see letter to Evans written about June 1903, LRVW, 43–4.

11 Writing his brief ‘Musical Autobiography’ around 1950, the composer recalled that before beginning work on A London Symphony, he had ‘sketched three movements of one symphony and the first movement of another, all now happily lost’ (‘Musical Autobiography’, 37). No sketches corresponding to this description would appear to have survived; one nevertheless wonders if the composer, half a century later, was thinking of some of the projects discussed here that advanced rather further than sketches, even if they did not achieve a definitive form.

12 On the Bournemouth lectures see Chapter 11, 231 and 240. It seems likely that a trip to the area in 1898 with Adeline Vaughan Williams played a part in the inspiration for these works. In a letter to his cousin Ralph Wedgwood written in early June of that year Vaughan Williams describes in some detail his reactions to the New Forest landscapes, and his preference at this time for ‘soft scenery to stern uncomfortable scenery’ (see LRVW, 30–1). His later fascination with the Fens and with Salisbury Plain suggests that this view of landscape evolved, or at least broadened to include other possibilities.

13 The main theme of The Solent seems to have haunted Vaughan Williams, cropping up again in A Sea Symphony and in two compositions from the last decade of his life, the music for the film The England of Elizabeth (1955)and, more importantly, the second movement of the Ninth Symphony (1956–8): see , Vaughan Williams’s Ninth Symphony, Studies in Musical Genesis and Structure (Oxford University Press, 2001), 272; and Herbert, ‘The Genesis of Vaughan Williams’s Sea Symphony’, i, 164–79.

14 See , ‘Vaughan Williams and Folk-Song: The Relation between Folk-Song and Other Elements in His Comprehensive Style’, The Music Review 15/2 (1954), 103–26at 112.

15 See , ‘Modern British Composers. x. Ralph Vaughan Williams’, MT 61/927 (May 1920), 302–5at 305. The three rhapsodies were never in fact performed together before the composer abandoned the symphonic scheme, but they were integrated thematically in certain respects, as is discussed below.

16 By the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Richard Hickox, on the Chandos label, CHAN 10001 [01], released in 2002. Pages 15–16 of the manuscript are missing; they were speculatively reconstructed for this recording by Stephen Hogger.

17 See KC, 35–6.

18 James Day notes the similarity (one that has likely struck many listeners) between the opening of the Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1 and the ‘Dawn’ interlude from Britten’s Peter Grimes, which uses strikingly similar textural and timbral effects to portray the same East Anglian coastline. See , Vaughan Williams, 3rd edn (Oxford University Press, 1998), 176. Day does not mention, however, the extraordinary parallel between the text of the folksong, which comprises the confession of a sea captain on trial for his fatal abuse of a young boy taken from the workhouse, and the almost identical story of Peter Grimes (though the captain of the folksong has been wilfully brutal, whereas Grimes’s crimes, and the line between neglect and deliberate cruelty, remain shrouded in some obscurity).

19 , ‘Generalized Diatonic Modality and Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Compositional Practice’, PhD dissertation, Yale University, 2008, Chapter 3.2.

20 In ‘Musical Autobiography’, 35.

21 The recording was released as Vocalion A0249; it has been reissued most recently on the Dutton Laboratories label, CDBP 9790 [01], in 2009.

22 Letter dated 31 December 1911, LRVW, 84.

23 Nathaniel G. Lew, ‘“Words and Music that are Forever England”: The Pilgrim’s Progress and the Pitfalls of Nostalgia’, VWE, 182.

24 See in particular , ‘Tallis – Vaughan Williams – Howells: Reflections on Mode Three’, Tempo 148 (1984), 2–13; and Anthony Pople, ‘Vaughan Williams, Tallis, and the Phantasy Principle’, VWS, 47–80.

25 , ‘On the Structure and Proportions of Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis’, Journal of the Royal Musical Association 135/1 (2010), 115–44.

26 See Pople, ‘Vaughan Williams, Tallis, and the Phantasy Principle’.

27 Ibid., 48–50. Vaughan Williams wrote another fantasia in 1910, this time for full orchestra, that seems to have hewn more closely to Cobbett’s formal prescriptions; unfortunately nothing survives of the work, and our knowledge of it is based primarily on reviews of its first and only performance. The Fantasia on English Folk Song: Studies for an English Ballad Opera was performed at the Proms on 1 September 1910; it seems likely to have been an offshoot of the composer’s work on his opera Hugh the Drover, and was in a single movement with three sections, fast–slow–fast. Michael Kennedy suggests that it may have been reworked for military band in the early 1920s as the suite English Folk Songs, which would go on, arranged for various ensembles, to be one of the composer’s most popular works: see KC, 57–8.

28 For primary information on this and other Whitman settings referred to here, including poetic text sources, see KC. For a more detailed chronology of work on A Sea Symphony see Chapter 2 of Herbert, ‘The Genesis of Vaughan Williams’s Sea Symphony’.

29 See , ‘No Armpits, Please, We’re British’, in (ed.), Walt Whitman and Modern Music: War, Desire, and the Trials of Nationhood, Border Crossings vol. 10 (New York: Garland Publishing, 2000), 25–42; and , ‘“O Farther Sail”: Vaughan Williams and Whitman’, in (ed.), Let Beauty Awake: Vaughan Williams, Elgar and Literature (London: Elgar Editions, 2010), 77–95.

30 Nuanced arguments pro and contra the symphonic status of the work have been advanced recently by Julian Onderdonk, ‘Vaughan Williams and the Austro-German Tradition: Tonal Pairing and Directional Tonality in A Sea Symphony’, paper presented at the annual national meeting of the American Musicological Society, Columbus, Ohio, Reference McGuire2002; and Charles Edward McGuire, ‘Vaughan Williams and the English Music Festival: 1910’, VWE, 235–68. Onderdonk argues in particular that the first movement cleaves more closely to sonata form than has often been taken to be the case.

31 The opening juxtaposition of B♭ minor and D major triads (a harmonic polarity that is recalled at several junctures of the symphony) creates a complete hexatonic collection; hexatonic relationships would go on to play a broader role in A London Symphony.

32 See ‘Musical Autobiography’, 37; here Vaughan Williams also credits George Butterworth, to whom the work was eventually dedicated, with the idea for beginning work on a symphony at this time, which was probably early in 1911. It is impossible to date the progress of the symphony with any precision, but in a letter to Cecil Sharp apparently written in July 1911 the composer refers to being ‘in the middle of a great work’, and Hugh Cobbe is surely right in suggesting that this refers to A London Symphony: see LRVW, 81–2.

33 Letter of 30 September 1957: see KW, 139–40.

34 See , ‘H. G. Wells and Vaughan Williams’s A London Symphony: Politics and Culture in Fin-de-Siècle England’, in , and (eds.), Sundry Sorts of Music Books: Essays on the British Library Collections. Presented to O. W. Neighbour on His 70th Birthday (London: British Library, 1993), 299–308.

35 See Stephen Lloyd, ‘Vaughan Williams’s A London Symphony: The Original Version and Early Performances and Recordings’, in VWIP, 91–117. The original version can be reconstructed from manuscript sources in the British Library (Add. MSS 50317A–D); it was recorded in 2000 by the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Richard Hickox (Chandos 9902). The first movement was left virtually untouched in later revisions, but the other three movements were extensively altered.

36 Surprising though it may seem, this symphony has a strong claim to be the most ambitious musical representation of a modern metropolis composed before World War I. Its closest counterparts in the orchestral arena are Delius’s tone poem Paris: The Song of a Great City (1899), Elgar’s overture Cockaigne: In London Town (1901), and Ives’s ‘contemplation’ (as he called it) Central Park in the Dark (1906); yet while all three works constitute important precedents they are much more modest in scope, with the longest of them, the Delius, lasting only about twenty minutes.

37 Cockaigne was the most significant orchestral portrait of London to have appeared before Vaughan Williams’s symphony. While critical reception has largely taken at face value the work’s undoubted energy and swagger, Aidan J. Thomson has recently suggested that darker undercurrents may be heard: see ‘Elgar and the City: Some New Lines on Cockaigne’, MQ 95/4 (Winter 2012). Such an interpretation may also be considered alongside Elgar’s plans, albeit never realized, for a much darker companion piece, based on James Thomson’s notorious poem ‘The City of Dreadful Night’: see , Elgar: A Creative Life (Oxford University Press, 1984), 349. The more positive side of Vaughan Williams’s own response to city life is suggested by the composer’s landmark Reference Vaughan Williams1912 essay entitled ‘Who Wants the English Composer?’ (Royal College of Music Magazine 9/1 (1912), 11–15; reprinted in VWOM, 39–42), written while he was working on the symphony. Here Vaughan Williams exhorted his composer peers to embrace all the rich musical and sonic diversity of modern English life; he opens with a quotation from Walt Whitman, and seems to share with the poet a willingness, unusual at the time, to see in urban social diversity signs of hope as well as threat. A London Symphony certainly celebrates this aspect of the city, even as it also evokes more destructive forces.

38 See , ‘Tonality on the Town: Orchestrating the Metropolis in Vaughan Williams’s A London Symphony’, in , and (eds.), Tonality 1900–1950: Concept and Practice (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2012), 187–202.

39 Both the Scherzo and the finale were heavily cut in the post-premiere revisions; the Scherzo lost an entire second trio, whose troubled character survives only in the menacing coda of the original version, and the finale (a complex and unorthodox structure even in its final form) originally contained additional episodes.

40 The wartime origins were revealed to Ursula Vaughan Williams (at that time Ursula Wood) in 1938: see UVWB, 121. On the initial critical reception of the work see KW, 155–6.

41 See in particular , ‘Modal and Thematic Coherence in Vaughan Williams’s Pastoral Symphony’, The Music Review 52 (1991), 203–17; and , ‘Landscape and Distance: Vaughan Williams, Modernism and the Symphonic Pastoral’, in (ed.), British Music and Modernism, 1895–1960 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010), 147–74.

42 See Grimley, ‘Landscape and Distance’, 150–2.

43 KW, 155.

5 The songs and shorter secular choral works

Vaughan Williams clearly had a profound relationship with the voice. In an article published in 1902 he wrote that the voice ‘can be made the medium of the best and deepest human emotion’.1 Nearly forty years later, in an article published during the Second World War, he reiterated his belief in the primacy of the voice: ‘One thing, I think, we can be sure of, no bombs or blockades can rob us of our vocal chords; there will always remain for us the oldest and greatest of musical instruments, the human voice.’2 This belief in the fundamental role that the voice plays in expressing emotion through music is something Vaughan Williams was to exemplify throughout his career. His vocal music touches on every genre imaginable, from opera through cantatas, motets, anthems and other sacred works, to unaccompanied part-songs and choral music on a broader scale; from arrangements of folksongs and hymns to solo song, whether as individual songs or as sets of songs or song-cycles accompanied by a range of instruments from piano alone through to orchestra. Even some of his works in orchestral genres give a prominent role to the human voice, from the fully choral first symphony, A Sea Symphony (1909), through A Pastoral Symphony (1924), in which a wordless solo for soprano voice opens and closes the finale, and Flos Campi for viola, orchestra and wordless chorus (1928), to the Sinfonia Antartica (1953), which incorporates a female chorus and soprano solo, both wordless.

Yet in the first edition of his study of Vaughan Williams, published in the Master Musicians series shortly after the composer’s death, James Day makes the somewhat surprising assertion that ‘Vaughan Williams was not a great song-writer’, going on to write: ‘His melodic gift was fertile and original, and his ability to set words aptly and simply was undoubted, but his songs rarely rise above competence, and only very few of them are complete, rounded, successful works of art.’3 This seems a strange way to assess the work of the composer of such well-loved and enduring songs as ‘Linden Lea’ (1902)4 and ‘Silent Noon’ (1904), or the song-cycles Songs of Travel (1905, 1907) and On Wenlock Edge (1911). But such an assessment is perhaps best understood in the context of a recurring attitude not only to Vaughan Williams’s song-writing but to British song in general. Although Vaughan Williams composed solo song – the main focus of this chapter – throughout his life, until quite recently there has been a recurring tendency in literature on the composer to skirt over his small-scale vocal music and concentrate instead on works written for larger, primarily instrumental forces. Even Michael Kennedy’s painstaking and thorough account of Vaughan Williams’s music and its contexts manifests this tendency: rather than highlighting the composer’s love of the voice, for instance, Kennedy explains the prominence of song in his early career as a response to the comparative difficulties of getting new orchestral works performed for British composers of his generation.5 With the exception of Stephen Banfield’s Sensibility and English Song (1985), which pays detailed attention to Vaughan Williams’s song-writing,6 this aspect of the composer’s achievement has had to wait until the last few years to receive its due. Vaughan Williams Essays, edited by Byron Adams and Robin Wells in 2003, includes detailed explorations of Songs of Travel and Four Last Songs,7 while a symposium at the British Library in 2008 explored Elgar, Vaughan Williams and literature, and featured a number of contributions on Vaughan Williams’s songs and other settings of literary texts.8 The re-evaluation of his song-writing has also benefited enormously from the Ralph Vaughan Williams Society’s issue of two important recordings: Kissing Her Hair: Twenty Early Songs of Ralph Vaughan Williams and Where Hope Is Shining: Songs for Mixed Chorus.9

Whatever the state of critical opinion over the years, however, the songs have remained among the most widely performed and recorded of Vaughan Williams’s works. Several general themes permeate the critical literature: that his best-known songs are early works and therefore primarily valuable in pointing the way to the large-scale music of his maturity; that he constantly chose highbrow texts by canonical poets; and that he had a particular aptitude for word setting.10 But were these last two attributes unusual among English songwriters of his or earlier generations? What were the contexts in which songs were produced, particularly in the early years of the twentieth century, the time when Vaughan Williams’s vocal music started to be published and performed beyond an immediate circle of friends or teachers? More generally, was song-writing really a genre in which Vaughan Williams rarely rose above the competent or seldom achieved complete, rounded, or successful works of art? In this chapter I will explore some of the misunderstandings surrounding turn-of-the-century British song culture and a continuing disregard for this genre, aiming to reach a deeper understanding of the context in which Vaughan Williams produced his songs in all their glorious diversity.

English song and the marketplace: royalty ballad and art song c. 1900

In 1902 Vaughan Williams wrote to his cousin Ralph Wedgwood:

I’ve not much to chronicle except that I’ve sold my soul to a publisher – that is to say that I’ve agreed not to sell songs to any publisher but him for 5 years. And he is going to publish several pot-boiling songs of mine – that is to say not real pot boilers – that is to say they are quite good – I’m not ashamed of them – as they are more or less simple and popular in character. They are to come out in a magazine called ‘The Vocalist’ and then to be published at 1/0 – which is a new departure – and I’m to get a penny halfpenny on each copy – so you see I’m on the high road to a fortune.11

Vaughan Williams’s typically self-deprecating attitude towards this publishing deal belies what was in fact a strongly held belief in what he was doing and the music he was creating. Yet he is defiantly unashamed – as he was to remain throughout his career – of simplicity and popularity. The extract also says a good deal about contemporary attitudes to song publishing. For decades there had been considerable press coverage of what were seen as the iniquities of the ‘royalty ballad’ system, whereby publishers paid singers a royalty every time they performed a certain song.12 At the turn of the century, the issue was still current. In 1901 The Times reported on an address by Frank Sawyer to the Incorporated Society of Musicians. Sawyer talked about song publishers and singers, explaining that

there were, unfortunately, comparatively few singers who were also true artists, and the present condition of the song publishing trade intensified the evil. A song publisher was purely a tradesman. He accepted the copyright of a song, not because it was good music, but because he thought it would hit the more or less vulgar taste of a general audience. Having published it, he hired singers like so many sandwich-men to go round the country crying his wares.13

Often royalties were paid not only to singers but also to composers, who if they did not sell their song outright, received a royalty for each copy sold, as in Vaughan Williams’s deal with The Vocalist.14 The Vocalist had been launched in April 1902 and was aimed at ‘all those who consider themselves in the category of singers, whether they be elementary or advanced, amateur or professional’ as well as those ‘interested in musical art, and. . . “fond of singing”’.15 Readers were promised ‘four good new songs’ in each issue.16 The first issue included Vaughan Williams’s ‘Linden Lea’, a setting of words by William Barnes described as ‘a Dorset folksong’. This was Vaughan Williams’s first published work and he was to contribute several articles and songs to the early issues of the magazine.17

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, songs were a part of the programme in every type of public concert, as well as sung in every kind of home – either to family and friends around the ubiquitous piano or, in high-class circles, to invited audiences in lavish music-rooms. Publishers promoted their songs through Ballad Concerts, such as Boosey’s popular series at St James’s Hall, which had started in the 1860s. Study of surviving programmes shows that Ballad Concerts could in fact provide a wide range of vocal music, including songs by canonical composers such as Schubert or Schumann as well as an array of ballads.18 Nevertheless, the attitude in the musical press towards both the Ballad Concerts and the ‘royalty ballad’ remained consistently critical. Vaughan Williams joined in the criticism in his ‘Sermon to Vocalists’, published by The Vocalist in 1902. In this article he addresses amateur vocalists and implores them to use their intelligence when selecting songs, and to choose the sincere rather than the false. He describes the royalty ballad as possessing ‘neither melody nor rhythm’, and asks singers whether they really imagine that it is ‘so called because it is patronized by Royalty?’19

What other songs were being published and heard in London’s concert halls at the beginning of the twentieth century? Although by the turn of the century Vaughan Williams’s teachers Charles Villiers Stanford (1852–1924) and Hubert Parry (1848–1918) were involved primarily with high-profile operatic, orchestral and choral works, they continued to publish songs. Stanford’s An Irish Idyll in Six Miniatures, Op. 77, a collection of songs setting poetry by Moira O’Neill, appeared in 1901; and in 1902 Novello published the fifth set of Parry’s English Lyrics, settings of various British authors, including Shakespeare, Scott and Julian Sturgis.20 Another leading figure was Arthur Somervell (1863–1937), who, like Vaughan Williams, had studied at Cambridge and the Royal College of Music with Parry and Stanford. On 7 March 1901, at St James’s Hall, he gave a concert of his own music that included the popular Cycle of Songs from Maud (Alfred, Lord Tennyson) and Love in Spring Time, which might aptly be termed an anthology, setting as it does poems by Tennyson, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Charles Kingsley.21

Other composers active at this time were primarily songwriters. One of the best known today is Roger Quilter (1877–1953), remembered for his Tennyson setting ‘Now Sleeps the Crimson Petal’ (1904) and his many settings of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English poets. In the summer of 1901 Quilter returned from studies in Frankfurt to accompany a performance of his Four Songs of the Sea (to his own words), at the Crystal Palace. This work was also published, as his Op. 1, in the same year. Quilter was a good friend of one of the most popular songwriters of the 1890s, Maude Valérie White (1855–1937). At the start of the century White had moved to Taormina in Sicily, largely for the sake of her health, but returned regularly to England to organize concerts of her songs. On 20 May 1903, for example, she gave a concert of her ‘tasteful and well-written songs’ at St James’s Hall.22 The selection of songs, typical of White’s diversity, included settings of German, French and English lyrics as well as arrangements of Sicilian tunes. The British poets represented included Burns, Swinburne, Herrick, Shelley and both the Brownings. White’s friend Liza Lehmann (1862–1918) was another important songwriter of the time. Her song-cycle for four voices and piano, In a Persian Garden (1896), which sets parts of Omar Khayyám’s Rubáiyát, in the then fashionable translation by Edward FitzGerald, remained popular far into the twentieth century. On 4 January 1902 it was performed at one of the ‘Popular Concerts’ at St James’s Hall, a series that, despite its name, showcased the ‘highbrow’ end of the song spectrum.23 Lehmann’s songs, like those of White, were also heard at the lighter Ballad Concerts, and she herself clearly divided her compositions into ambitious or serious work, such as her Tennyson cycle In Memoriam (1899), and lighter, more popular and financially rewarding pieces.

The changing reception of Lehmann, White and their music highlights the difficulties of clearly defining the difference between the royalty or drawing-room ballad and the ‘art song’.24 Both these songwriters heard their work performed at a wide range of public and private venues. In their early careers both were regarded as raising the level of the English song and, particularly in the case of White, choosing a better class of lyric to set.25 In 1903 Edwin Evans published an article on Lehmann in his series ‘Modern British Music’ for The Musical Standard, which showcased composers ‘who actually are modern, breathe the modern spirit and write modern music’26 (Vaughan Williams was featured in another article in the series). In these articles, Evans had decided ‘to avoid the vortex of the English song world’ but made an exception for Lehmann, feeling that there were several reasons, such as her introduction of the song-cycle, for writing about her ‘apart from the artistic excellence of her work’.27 Nevertheless, later in their careers both White and Lehmann came to be regarded only as ballad composers, and after their deaths their contribution to British song was almost entirely overlooked and forgotten. The reasons behind this neglect are complex; the fact that they were both women, and therefore not expected to be capable of producing ‘great’ music, undoubtedly played a significant part. But just as important is the fact that they were primarily songwriters, concentrating on a genre so consistently regarded as insignificant. The two issues of gender and genre are of course not unrelated: the prominence and success of female songwriters at the turn of the century undoubtedly contributed to the later downgrading of British song as a genre, despite the indisputable power and beauty of songs by composers as diverse as Parry, Quilter, White and Vaughan Williams.

The early songs: from Herrick to Housman

It is worth highlighting that Vaughan Williams was nearly 30 years old when ‘Linden Lea’ appeared in The Vocalist and he first stepped into this world of song production. ‘Linden Lea’ was, of course, not the first song he had written: there are several songs surviving in manuscript or published later that pre-date what was to become his best-selling song.28 But what do we know about his experience of song in his first three decades? The answer is surprisingly little. Both Ursula Vaughan Williams’s biography of the composer and Vaughan Williams’s own brief ‘Musical Autobiography’ are curiously reticent about his early exposure to song.29 Unfortunately, very few letters to or from Vaughan Williams survive from before the late 1890s, and even then they tend to be unforthcoming about his musical life and experiences.30

As a child at Leith Hill Place, Vaughan Williams learned the piano and harmony from his mother’s sister, Sophy, who taught him theory from The Child’s Introduction to Thorough Bass in conversations of a Fortnight, between a Mother and her Daughter of Ten Years Old, published in 1819.31 When Ursula Vaughan Williams mentions this book, she gives only the first six words of the title, omitting the interesting fact that it was clearly aimed at educating female children. Neither Ursula nor Vaughan Williams himself mention singing as part of the family music-making, other than hymns on Sundays.32 Vaughan Williams’s childhood compositions included operas for his toy theatre, and it seems unlikely that he would have engaged in this genre with no experience of vocal music other than hymns. It is also unlikely that a family clearly interested in music would not have owned and enjoyed songs. Ursula Vaughan Williams records that the family went to the Three Choirs Festivals,33 and here they would certainly have heard songs as well as orchestral and choral works.