But be not satisfied by merely setting your names to a constitution—this is a very little thing. . .

The seeds of knowledge must be sown broad-cast over our land—light must be increased a thousand-fold—and woman ought to be in this field: it is her duty, her privilege to labor in it, “as woman never yet has labored.”

By spreading correct information on the subject of slavery, you will prepare the way for the circulation of numerous petitions, both to the ecclesiastical and civil authorities of the nation.

Angelina Grimké, An Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States (1837, 57, 58).

Participation shapes the politics of the present, and because much participation is about facilitating and organizing the participation of others, it shapes the politics of the future. By joining in politics, women and men acquire skills, contacts in networks, and beliefs (including confidence and felt efficacy) that enable deeper engagement in the movements, battles, and processes that come later. Shaping political participation is a crucial mechanism by which various institutions, policies, and processes generate behavioral legacies. Institutions and policies ranging from social movement activities (Calhoun Reference Calhoun2012; Lee Reference Lee2002; McAdam Reference McAdam1990; Reference McAdam1999; Parker Reference Parker2009b; Szymanski Reference Szymanski2003) to social and welfare policies (Campbell Reference Campbell2002; Reference Campbell2003; Mettler Reference Mettler2007; Soss Reference Soss1999) to referenda (Smith Reference Smith2002) have been shown to have durable implications for subsequent political activity.

This dynamic of participation begetting participation is particularly evident and important in studies of women's political activity. Research suggests that women's political disadvantages stem from an aggregation of factors such as income, family and caregiving burdens, social expectations, and other dynamics that collectively point in the same causal direction: toward reduced opportunities and resources for political participation (for a classic treatment and summary, see Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Scholzman and Verba2001). In the face of these hurdles and constraints, the participatory lessons and opportunities in social movements may be particularly significant for women in democratizing societies. In many democratic settings, the institutions, liberties, and norms that enable women's political activism have emerged only in the last century. Still, the history of women's political participation demonstrates that mass political activity often boldly precedes formal voting rights and other social, political, and economic liberties recognized in law (Flexner and Fitzpatrick Reference Flexner and Fitzpatrick1996). In the United States, nearly a century before they enjoyed widespread suffrage rights and decades before their role in the public sphere was legitimated, women circulated thousands of petitions and gathered millions of signatures on petitions for various political causes (Lerner Reference Lerner1980; Szymanski Reference Szymanski2003; Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003). This activism—the circulation and signing of petitions, particularly in the antislavery movement—forms the subject of our inquiry and permits a revealing investigation of women's participation in democratic politics, especially in the United States.

From the 1820s through the 1850s, women and men in the United States began to petition their government at increasing rates, especially for issues that were perceived to carry a spiritual dimension: against the removal of the Cherokee from their ancestral lands, against slavery and its territorial spread, for Sabbatarianism (for prohibition on the delivery of mail on Sundays), for temperance and prohibition, and others (Morone Reference Morone2004; Portnoy Reference Portnoy2005; Szymanski Reference Szymanski2003). These movements bequeathed to modern social scientists a narrative and statistical database of stunning proportions: tens of thousands of petitions in state and national archives from this period alone, with likely millions of signatures. Combined with organizational and associational records, diaries, and other census information, petition data allow a highly elaborate portrait of political activity—especially women's activity—in democratic politics before and after universal suffrage.

Scholars in history and women's studies have long claimed that participation in these early causes formed the basis for political awakenings and organizational skills (Berg Reference Berg1978; Flexner and Fitzpatrick Reference Flexner and Fitzpatrick1996; McPherson Reference McPherson1967; Reference McPherson1975; Lerner Reference Lerner1980; Marilley Reference Marilley1996). The evidence for this proposition is abundant and methodologically varied, ranging from biographies of important women to observations of contemporaries. Yet although antislavery activism and petitioning in general have been studied in this literature, the role of women as canvassers—those who launched individual petitions and gathered signaturesFootnote 1 —has received far less attention. In this article, we provide perhaps the first comprehensive statistical analysis of women's canvassing and petition organizing, an assessment that uses actual petitions in lieu of surveys about petitioning or canvassing.

Examining a new and unique dataset of more than 8,500 petitions sent to the U.S. House of Representatives from 1833 to 1845, we demonstrate that in 1836–37, when Congress “gagged” antislavery petitions by tabling them and the sisters Angelina and Sarah Grimké began to give public lectures and to canvass petitions—all the while encouraging women to circulate petitions themselves (Grimké Reference Grimké1837)—women subsequently became much more active in antislavery canvassing. Women began to circulate two kinds of petitions in greater numbers: (1) petitions signed by other women only and (2) petitions signed by both men and women, in which the names of male and female signatories appeared in separate columns. We focus on the first of these categories in this article and examine the second category at more length in the Supplementary Appendix. We find that petitions canvassed by women had 50% or more signatories than did petitions on the same topics, passed through the same localities at the same times, but canvassed by men. This explosion of women's petitioning was followed by broader women's activity in other causes and in the antislavery cause specifically.

We interpret and extend this pattern in three ways. First, our study offers new statistical documentation not merely of women's participation in antislavery but also of the success of women canvassers in the massive recruitment and organization of others’ participation. As is well known, women's petitioning activity in the antislavery movement occurred not only before women's suffrage but also before the movement for suffrage rights itself (DuBois Reference DuBois1978).

Second, we postulate and provide evidence for several concrete mechanisms by which women canvassers gathered more signatures than men and by which women's canvassing experience enabled later political activity. These mechanisms—persuasion, network formation, and organization—are applicable to political science and social science research more generally, especially as they are shaped by canvassing activity (with or without petitions). We provide evidence from diaries and other archival data that women's canvassing activity entailed persuasion, network formation with other women (including consciousness raising), and organization. Many of the participants were teenagers active in politics for the first time, and women canvassers invested significant time and energy in trying to persuade others to sign petitions as they covered entire communities and neighborhoods. Although our evidence on the point is qualitative rather than quantitative, our account supports recent scholarship suggesting that walking facilitates mobilization in social movements (Knudsen and Clark Reference Knudsen and Clark2013), yet also suggests that walking's effect in politics may be explained by the kinds of activities that go with it. Although space constraints permit only a limited presentation of this data here, we believe that the combination of personal narrative with quantitative data is an important and underutilized strategy in behavioral political science research (Walsh Reference Walsh2004; Reference Walsh2006; Reference Walsh2012).

Third, we examine the post-petitioning careers of women who canvassed in the 1830s and 1840s. We do this first qualitatively, by demonstrating that pivotal signers of the Seneca Falls Declaration of 1848—commonly regarded as the chief originating moment of the women's rights movement in the United States—had been antislavery petitioning canvassers a decade earlier. Second, we extend an independent sample of post–Civil War activists based on the work of the historian James McPherson (Reference McPherson1975), who compiled a sample of 284 pre–Civil War abolitionists who remained active in politics and reform after 1865. McPherson's sample included activists who were instrumental in social welfare lobbying and the movements for African American and other minority rights, women's rights, and other causes. Some went on to found organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). And among McPherson's sample of activists, women were four times more likely to have served as canvassers in the crucial petitioning period of 1833 to 1845 than men.

Our study demonstrates how door-to-door canvassing both politically educates and socially empowers its participants. By immersing citizens in the process of persuasion, by facilitating contacts with others (those already mobilized and those not yet mobilized but potentially active in the future) and raising consciousness, and by involving citizens in political organizing, canvassing can shape later activism. These patterns may be accentuated when canvassing is undertaken by women and others whose identities and work are marginalized by the political system. Our study also points to a new research agenda in political science and related disciplines, one centered on large-scale petition data (quantitative and qualitative), because the petition is an institution and practice that presage wider activity. We note, however, that contemporary forms of petitioning (such as e-petitioning) that do not involve interpersonal persuasion and contact-making may not have the effects we describe here. In a contemporary context, our findings may apply more to interpersonal petitioning and door-to-door canvassing for nonpetitioning campaigns (fundraising, getting out the vote). We conclude with reflections on the larger significance and the utility of quantitative and qualitative data such as that we have collected.

PETITIONING, CANVASSING, AND MOBILIZATION: THE MECHANISMS OF POLITICAL EMPOWERMENT

We define a petition as an organized request for political redress or policy of some sort, which contains two essential elements: a “prayer” (or request or expression of grievances) and a signatory list presenting those persons who have affixed their name in approval of the prayer.Footnote 2 Petitioning is one of the most important activities in democratic politics, especially in the United States, where it is mentioned in the Declaration of Independence and enshrined as a right in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Yet, although petitions have been occasionally studied in political science, they are usually studied through survey instruments (Bingham, Frendreis and Rhodes Reference Bingham, Frendreis and Rhodes1978; Blake, Mouton, and Hain Reference Blake, Mouton and Hain1956; Caren, Ghoshal, and Ribas Reference Caren, Ghoshal and Ribas2011; Helson, Blake, and Mouton Reference Helson, Blake and Mouton1958), or through experiments (Margetts et al. Reference Margetts, John, Escher and Reissfelder2014; Suedfeld, Bochner, and Matas Reference Suedfeld, Bochner and Matas1971). The study of petitioning using signed petitions themselves is quite rare. Methodologically, our study follows in the line of pioneering work by Lee (Reference Lee2002), who examined the dynamics of public sentiment on civil rights by collecting and examining a large dataset of letters sent to the U.S. president.

Mechanisms of Canvassing and Enabling Activism

Our study focuses on canvassing, which we define as the act of searching for and obtaining signatures in assent of a petition's prayer, and/or organizing the work of other canvassers. Canvassing in this general sense can mean walking or driving a petition door-to-door, and it can also mean organizing or attending a meeting at which the petition is available for signature or obtaining signatures at public places (a crossroads, a market, a shopping or public center). The formative power of canvassing in American women's petitioning was expressed through several interconnected mechanisms.

Persuasion

By virtue of their embedment in moral reform and evangelical efforts and their distance from the party sphere—where men were mobilized but where citizens often perceived corruption and vain self-interest—women were often more persuasive antislavery canvassers than men (Marilley Reference Marilley1996, 16; Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003, 3, 185). Women's experience in the day-to-day moral and ethical persuasion required by antislavery petitioning, moreover, trained them in tactics of political rhetoric and, in a sense, campaigning (not for a party, but for a cause). Persuading women to sign something as public and controversial as an antislavery petition often meant persuading their husbands, fathers, or brothers as well (Flexner and Fitzpatrick Reference Flexner and Fitzpatrick1996, 48; Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003, 109). Canvassing required women to formulate and express arguments on behalf of the antislavery cause, to listen to objections and questions, and to exhibit patience with those who expressed doubts or who disagreed with the petition's prayer. Women in the 1830 s were particularly adept at meeting these challenges given the boost in literacy and education in the decades before (Berg Reference Berg1978; Cott Reference Cott1997, 101, 103; Kerber Reference Kerber1980, 193) and the fact that many had participated in evangelical circles and had acquired familiarity with Scripture. Ironically, women's very separation from politics in the antebellum era gave them moral authority to contest both slavery's institutions and, eventually, their exclusion from public voice (Cott Reference Cott1997, 205–06). Door-to-door mobilization often relies on these same mechanisms, and it constitutes training in political rhetoric, in the practice of argument.

Network Formation and Consciousness

Women who were canvassing petitions made contact with other women, many of whom were newly introduced to the possibility of women entering into the public sphere. Petitioning allowed these women to forge important ties to one another and to raise consciousness of their status as women whose voices and liberties were restricted and for whom the petition was thus so crucial. Women who saw female antislavery canvassers at their door came to the realization that other women thought and imagined their political and religious lives in ways similar to theirs. The sheer number of these interactions ensures that, if only a small proportion led to new social ties and consciousness, the resulting transformation was nonetheless significant.

Petitioning was one of the only avenues available to women to participate in political discourse, which explains why they found the gag rule both insulting and an infringement of their liberties, and thereby helps account for the timing of the canvassing explosion. With the rise of universal white male suffrage and the emergence of the Jacksonian party system and patronage, men were not only officially counted in politics but also structurally invited into the public sphere.Footnote 3 By the 1830s, petitioning was widely perceived by women as their primary (if not their only) public voice in American politics (Boylan Reference Boylan2002, 159–62; Grimké Reference Grimké1837). When the gag rule was passed, antislavery leaders such as the Grimké sisters, Maria Chapman-Weston, and William Lloyd Garrison (who was heavily influenced by the black abolitionist Maria Stewart) wrote important essays, books, and public letters urging women to take up antislavery petitioning (Chapman Reference Chapman1839; Angelina Grimké Reference Grimké1837; Sarah Grimké Reference Grimké1838) and gave widely publicized and controversial public speeches that provided examples of courage and radical action (Flexner and Fitzpatrick Reference Flexner and Fitzpatrick1996, 41–44; Marilley Reference Marilley1996, 25–29; Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003, 8, 34, 120–22). Women's canvassing exploded in part out of indignation with the gag rule, in part out of a commitment to demonstrate anew their numbers and will to Congress, and in part out of the realization that, by drawing attention to and protesting the gag rule, they could turn Northern opinion ever further against slavery and its supporting institutions. The gag rule, then, cast women's separation from the public sphere in stark relief and, in so doing, provided spiritual, rhetorical, and emotional fuel for women's expanding organizational activity, particularly in mobilizing other women.

Organization

The process of leading a petition campaign involved (and remains) far more than collecting signatures. Coordinating the work of others, calculating signatures, getting the petition's prayer printed, planning the collection of signatures, and other activities required a new kind of organizational work (Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003, 50–51), one less associated with reform organizations and more associated with the idea of a mass campaign. Women had already been involved in benevolence and moral reform societies (Berg Reference Berg1978, 6; Boylan Reference Boylan2002), yet the scale, controversy, and public exposure of antislavery petitioning appreciably surpassed those of earlier efforts (Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003, 22–27, 185).

The mechanisms have importance for understanding not only nineteenth-century mobilization but also contemporary participation. Yet the lessons we draw are less about petitioning generally and more about the act of canvassing. Although electronic petitioning has experienced considerable growth (Margetts et al. Reference Margetts, John, Escher and Reissfelder2014; Scherer Reference Scherer2013), we believe that it may not have the same formative effect as earlier petitioning campaigns, in part because the process of gathering signatures rests less on the work of canvassers than on the hub-spoke networks created by electronic mail systems. Hence the relevance of canvassing is probably historically contingent. Although more research needs to be done, our initial hypothesis is that the formative effects of canvassing today are more likely to be seen in door-to-door, in-person canvassing (to solicit contributions, to mobilize and organize the activity of others (e.g., the account of Freedom Summer in McAdam Reference McAdam1990), to get out the vote, or to collect signatures on traditional petitions) than in launching an electronic petition.

Contemporary Relevance of the Mechanisms: Feedback and Mobilization

Petition canvassing bears relevance not only to American political development but also to more general understandings of political participation, especially petitioning and women's political activity. All three mechanisms just discussed offer new, petition-based contributions to the feedback effects literature whereby current participation confers skills and contacts that enable future participation (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Scholzman and Verba2001; Mettler Reference Mettler2007; Parker Reference Parker2009a; Smith Reference Smith2002; Soss Reference Soss1999).Footnote 4 Second, a study of petitioning permits a direct empirical study of recruitment dynamics. An essential part of political participation is getting others to participate. The attempt to induce another citizen to make a financial contribution, to sign a petition, or to turn out to vote is one of the most common and vital forms of political participation. Politics is shaped not merely by voting but also by getting others to turn out; not merely by giving but also by inducing others to give; not merely in signing but also in gathering signatures (Brady, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Brady, Schlozman and Verba1999). The study of petitions allows for analysis of the recruiter as well as the recruited.

DATA AND STUDY

The data and setting for this study comprise two linked investigations. Our first investigation is an examination of antislavery petitioning in the 1830s and 1840s, based on an original database of antislavery petitions and related qualitative evidence on petitioning in 1830s and 1840s. Our second investigation is an examination of women's and men's activism after 1845 (the Seneca Falls Declaration) and especially after the Civil War, based on the work of McPherson (Reference McPherson1975).

At few junctures in the political history of any nation was women's petitioning more vibrant than during the antislavery campaign of the antebellum U.S. republic. From the 23rd Congress (1833–35) onward, abolition societies began to transmit antislavery petitions to the national legislature, particularly the House of Representatives. These petitions often conveyed rather moderate demands, not asking for full-scale abolition of slavery but instead requesting the elimination of slavery in the District of Columbia, the prohibition of slavery in the territories, and the refusal of statehood to any prospective state whose constitution permitted chattel slavery. The campaign was spurred to new intensity when the House, led by pro-slavery Southern Democrats, adopted the “Pinckney resolution” in 1836 and began to systematically table the petitions. This institutional procedure quickly acquired the title of “gag rule” and endured until 1844 when it was repealed (Miller Reference Miller1995).

At the start of the 25th Congress (1837), women had not yet made a significant entrance into petitioning activity: “[M]ass petitioning campaigns by American women were still new in 1837” (Van Broekhoven Reference Van Broekhoven, Yellin and Horne1994, 181). Yet the gag rule changed this dynamic: Many women in the Northern states were particularly incensed and threatened by what they saw as an attempt to block one of their only channels of political voice. At the same time, the sisters Sarah and Angelina Grimké made a lecture tour, speaking in churches on the necessity for women to combat slavery in public discourse. Although controversial at the time—it was nearly unprecedented for women to lecture openly in American churches or before legislatures—the Grimké sisters’ tour helped legitimate women's political voice in a way that seemed to many radical Protestants to be consistent with the advancement of evangelical Christian values of the time. Critically, Angelina Grimké argued that canvassing petitions was more important and valuable than signing them or signing an antislavery society constitution (see the epigraph and Grimké 1837).

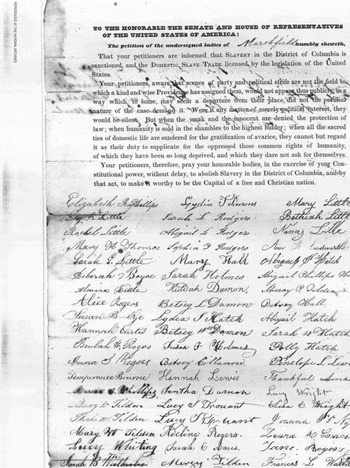

Examples of the petitions comprising our database appear in Figures 1 and 2. Both petitions demonstrate the novelty of women's petitioning the national legislature, but in different ways. In addition to republicanism, an important trope dominant in the petitions of the time was deference to antebellum cultural norms, particularly among women petitioners. The prayer of the petition from women of Marshfield, Massachusetts (see Figure 1)—one printed in a form that was portable among many contexts—shows that female petitioners were clearly aware of gender categories in antebellum America that mapped gender onto the public/private distinction.Footnote 5

FIGURE 1. Women's Antislavery Petition, Massachusetts, 25th Congress

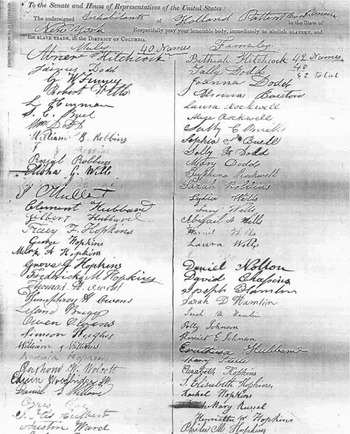

FIGURE 2. Gender-Separated-Column Antislavery Petition, New York, 25th Congress

To petition Congress was, for many women of the early Republic, a calculated but significant political risk. “Scenes of party and political strife,” the petitioners in Figure 1 recognized, were “not the field to which a kind and wise Providence has assigned them.” As historian Nancy Cott (Reference Cott1997) and others have emphasized, antebellum political culture was characterized by “separate spheres” for men and women; women were discouraged from leaving the sphere of private domesticity to enter the sullied world of politics. To make matters more risky, anti-abolitionist violence was common in the nineteenth-century North (Richards Reference Richards1970). Consistent with this cultural dichotomy, antislavery petitions often separated women's and men's signatures in distinct columns (see Figure 2). For women to petition Congress was an explicit transgression of cultural boundaries, which is why the women addressed the cultural propriety of their petition at its very outset (Figure 1; see also Boylan Reference Boylan2002; Flexner and Fitzpatrick Reference Flexner and Fitzpatrick1996; Portnoy Reference Portnoy2005; Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003).

To examine the development of petitioning and antislavery activism in this period, we embarked on a multiyear project to create an electronic database of all slavery-related petitions sent to the U.S. House from the 23rd through the 28th Congresses (1833–45). The resulting database of 8,647 petitions comprises all known petitions currently housed that were sent to the U.S. House of Representatives on slavery-related issues during these Congresses. There are reliable accounts of petitions sent to later Congresses (in the late 1840s and 1850s) having been lost (Miller Reference Miller1995, 307), in some cases even burned by archive employees to heat their rooms during cold winters, but our consultation with archivists suggests that the collections of antislavery petitions to the 23rd through 28th Congresses are intact. Because Anglo-American parliamentary traditions during this and preceding periods emphasized petitioning to the lower house of a bicameral legislature (Bowling and Kennon Reference Bowling and Kennon2002; Zaret Reference Zaret2000), we exclude a focus on the Senate here.

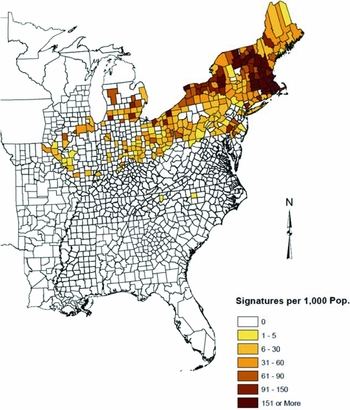

The data have an interesting, yet selective and concentrated geographic distribution. Figure 3 offers a county-level map of signatures per 1,000 county residents from petitions sent to the 25th Congress (1837–39), using county-level boundaries from 1840. We observed a concentration not only in well-known antislavery “hotspots,” including Massachusetts and western New York (which later hosted some of the early women's rights mobilizations), but also in New Hampshire, Vermont, Ohio, and southern Michigan. There are few Southern petitions outside of a handful from border-state mountain regions, but slavery-related petitions were commonly sent to Southern legislatures during this period (see Supplementary Appendix, Table A1). Antislavery activism in the South was culturally discouraged and sometimes prohibited (e.g., the interception of abolitionist materials in the postal system). The absence of Southern antislavery petitioning may have had long-term consequences for regional differences in American women's political mobilization and remains a subject for future research.

FIGURE 3. Geographic Distribution of Antislavery Petition Signatures to U.S. House, 25th Congress (signatures per 1,000 population)

There are several unique features of these data, especially as they regard political participation and women. First, open political activism on subjects of national debate was relatively if not entirely novel for the American women who participated in the antislavery campaign.Footnote 6 Women antislavery petitioners were, as Eleanor Flexner and Ellen Fitzpatrick have described them, “the first detachment in the army of ordinary rank-and-file women who were to struggle for more than three-quarters of a century for equality” (1996, 48). The petitioning and canvassing activity we describe was not, in other words, a result of hardened predispositions for activity in the antislavery realm or even the petitioning realm. Instead, after the gag rule passed in 1836, the 25th Congress (1837–39) brought thousands of women into national politics and legislative petitioning (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998; Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003). Our data show, for the first time, the scale of this transformation.

Second, the petitions were being sent to a Congress that was known to table them. While women continued to try to influence policy makers (Marilley Reference Marilley1996, 16), they were also aware that they were shaping Northern public sentiment. After passage of the gag rule, women petitioned in greater numbers to demonstrate their commitment, to protest against the restriction of their petition-expressed voice, and to continue to try to sway policy makers and even Southern slaveholders (Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003, 2, 13). Still, signing a petition was a very public act, less for the legislature that received the petition and more for the communities and networks in which the petition circulated or was laid out for citizens to peruse and sign (Portnoy Reference Portnoy2005; Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003).

Third, the petitions were highly localized, being sent from townships and occasionally entire counties. This feature allows the refinement of statistical controls based on geographic features of the data. And unlike voters who choose among candidates, petition signatories endorse specific policy requests (or express specific grievances). Because petitions with different policy topics circulate through towns and counties at the same time, the resulting array of petitions can look like a “poll” of sorts, though with obvious external validity limitations.

We used this data in two ways. First, we examined predictors of how many signatures appeared on a petition and, at the county level, calculated the per capita rate of petition signing. Because many counties and localities saw numerous petitions in the space of a few years, the sample permitted the assignment of fixed effects to the town or city of the petition's geographic origins, thus controlling for all static effects that vary by place. Examining the differences in various kinds of petitions among those circulated through the same town within a two-year period allowed us to better identify the predictive effect of the canvasser, because women canvassers either collected only women's signatures or collected men and women's signatures and separated them into gender-specific columns. Second, we examined several sources of data on later nineteenth-century women's activism in other reform movements, and we traced the presence of antislavery petition canvassers (for petitioning from 1833 to 1845) in these later activities.

IDENTIFICATION OF CANVASSER AND MEASUREMENT OF SIGNATURES

Our research strategy required two measurement strategies. First, when examining signature aggregates, we needed to identify whether the canvasser (whomever he or she may have been individually) was female or male. Second, for purposes of tracking canvassers to later careers, we needed to identify the particular individuals who canvassed.

Identifying the canvasser of a petition is not self-evident, because the person canvassing the petition does not usually identify her- or himself as such in the signatory list. To identify the canvasser of the petition as a woman, we used petitions circulated only to women, which were commonly known to have been circulated by women and by women only in the early nineteenth century (Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003), because men of the time generally considered it beneath their status to request and collect women's signatures. As a supplementary exercise, we also examined petitions in which the signatures of men and women appeared in separate columns, which are commonly regarded to have been circulated by both women and men or by women alone (see the Supplementary Appendix).

To identify the canvasser of a petition for purposes of tracing her later activist career, we took interpretive advantage of a common pattern of nineteenth-century signatory lists, in which the main canvasser's name was the topmost in the field of signatures. In many instances, there is evidence from other archival data, such as the placement of Maria Weston-Chapman's name on the top of two petitions from the women from Boston that were tabled in 1838, where it is known from her papers that she was canvassing at the same time these petitions were sent to Congress (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998, 90); the known work of Sarah C. Rugg as a canvasser and her presence as the top name on a petition of women from Middlesex County, Massachusetts (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998, 91); and the presence of Priscilla and Phebe Weston's names at the top of several petitions from Massachusetts, where it is known from the Weston-Chapman Papers that they were canvassing at the same time. Our examples of matches between topmost names and known canvassers in our data include Charlotte Woodward, Mary Ann McClintock, and Gerrit Smith.

The first potential problem with this strategy is that, particularly for large petitions, a team of women may have canvassed the petition, and the topmost women's name was probably the organizer of those other efforts as well as one among several canvassers. Hence we probably missed other canvassers by using this measurement strategy. Identifying these other canvassers would be difficult unless we knew, from other archival evidence, that their names were placed systematically in a certain area of the petition. However, by using this strategy we picked up those women who were the most organizationally active among the canvassers. In addition, our strategy probably resulted in the undercounting of canvassing and, given our career-tracing strategy followed later, underestimated the force of women's canvassing on their later political development.

The other concern with this strategy is that the top name in the list might be picking up a merely prominent person whose name is affixed to the petition in order to attract others’ signatures. For women in particular, we found little if any evidence of this pattern. For one, the restrictiveness of the “woman's sphere” meant that the vast majority of women petition canvassers were not publicly recognizable even in local contexts (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998). Many canvassers, such as Mary Ann McClintock and Charlotte Woodward of western New York or Lydia Carpenter of Boston, started petitioning as teenagers and became more widely active only a decade or more after conducting their antislavery petitioning. Moreover, in-depth studies from locales such as antebellum Rochester, New York (Hewitt Reference Hewitt1984), demonstrate that activists in antislavery and other causes came disproportionately from the middle and lower rungs of the socioeconomic ladder, rather than from the most prominent local families. Within one large city (Boston), our archival research shows that the topmost name was indeed that of the petition canvasser and organizer (e.g., Maria Weston Chapman). Second, our examination of diary evidence also suggests that where mothers wrote of their daughters canvassing (e.g., Mary Avery White Papers [see Appendix Table A2]), we would also find the daughters’ names in the top line of signatures in petitions from the same or nearby communities. This is consistent with other evidence in which the canvassers of antislavery petitions were as young as 11 to 14 years of age and their names appeared first in the signatory list (again, for example, Charlotte Woodward or Lydia Carpenter; see Appendix Figure A1). Finally, examining a wide range of archival sources and secondary literature, we found at least 20 instances in our sample in which the first name in the list can be identified as a canvasser in other records, yet we were unable as yet to find a single instance where the identifiable canvasser of a petition is not the topmost signature on the relevant petition in our database. We cannot rule out the lack of a correspondence existing between topmost names and canvassers, but archival evidence suggests that the measurement error is small to nonexistent.

There is, to be sure, no perfect indicator that permits us to verify in every case the exact canvasser of the petition. We note two factors that suggest that ours is a reasonable measurement strategy. First, despite these verification constraints, similar if not more daunting problems of verification affect other measures of participation. When it comes to nonpolitical acts measured in surveys, most analyses are based entirely on self-report. Even for electoral participation, reported vote choice (which candidate or position on a ballot was chosen) is subject to error. And previous political science analyses using petitions (Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2008) suffer from the same problems as those we note here. Second, if anything, it is quite likely that our measure and our data underidentify the biographies and presence of women canvassers. Many antislavery petitions were sent to state legislatures (for which we do not have records), and many petitions sent to Congress in the period 1847 to 1860 were lost or destroyed, which means that in tracing women's later careers as activists we are likely understating the presence of women canvassers who later became activists in related causes.

Another measurement issue comes in the assessment of the number of signatures gathered. Each petition comes with a summary of the number of signatures (e.g., “Petition of Charlotte Woodward and 167 other women from Warsaw, New York. . .” in which case the number of names is 168). We checked counts on a random sample of 100 petitions from the 25th Congress and found not a single case of erroneous correspondence between the listed number and the number that we could count. Undoubtedly in a sample of more than 8,000 petitions there may well be some disparity between the reported total and the actual, but we doubt that the error is systematic.

Some persons wrote the signatures of others, and in some cases entire signatory lists were copied (see Supplementary Appendix Section II.B). Might it be that signatures were forged? It is well known that, in an age of much lower literacy, many family members had others sign for them (Van Broekhoven Reference Van Broekhoven, Yellin and Horne1994). Yet historians agree that forgery—the signing of another person's name without or against his or her consent—seems very unlikely to account for differences between women's and men's canvassing, not least because especially among women, the pursuit of “truthful testimony” was a chief motivation in their work. Men and women alike were often apprehensive about having their names on a document circulated publicly and eventually sent to Congress (and for which a copy was often posted publicly after the original was sent to Washington). Those (especially women) caught up in the Second Great Awakening that began in the 1820s, led by the preacher Charles Grandison Finney, felt that their god was watching their every move, every sentiment, every thought, and every emotion (Stewart Reference Stewart1997; Van Broekhoven Reference Van Broekhoven, Yellin and Horne1994). If the forging of names is a concern, it is more likely that our subsequent analyses understate the added efficacy of women canvassers.

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF PETITIONS AND WOMEN'S CANVASSING

When women canvassed in the 1830s and 1840s, they generally went door to door with two kinds of petitions: women-only petitions and petitions with gender-separated columns. The women-only petition is a marker for where women circulated without men, whereas the separated column petitions indicate women's involvement, but it is often unknown what work-sharing arrangement existed between the men and women who likely cooperated in circulating the petition.

As our summary statistics in Table 1 suggest, only two in ten petitions in the sample were produced by women canvassers circulated to other women, but another 26.7 percent likely involved the work of women, because women were active in circulating petitions with gender-separated columns (as in Figure 2). More than six in ten petitions in our sample came from the pivotal 25th Congress, which was the first full Congress after the passage of the gag rule and at the beginning of which the Grimké sisters made their remarkable and auspicious entrance into political lecturing.

TABLE 1. Descriptive Statistics for Slavery-Related Petitions, 23rd–28th Congresses (1833–45)

Total number of petitions = 8,647. Source: National Archives, Record Group 233

We examined predictors of the number of signatories on a petition (Table 2) and the number of signatures per capita population in the county of origin (Table 3). In each least squares regression we added a full battery of fixed effects for each and every unique geographic location (township, city or, where these are unavailable, county) from which petitions were sent. With this basic set of controls added, we also added a control that codes for the petition's prayer —essentially, what the petition was asking for (see Supplementary Appendix, Section I, for a more detailed description of prayer coding). Some petitions asked for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. Others requested that slavery not be permitted in new territories or in new states admitted to the nation. Still other petitions requested that the gag rule itself be stopped or that particular territories such as Texas or Florida not be admitted as states (or as slave states).

TABLE 2. Regression of Total Petition Signatures on Petition Characteristics (antislavery petitions sent to U.S. House, 1833–45)

Notes: Fixed-effects regression with petition as unit of analysis; each fixed effect corresponds to smallest identifiable unit of village, township, city, or county from which petition was sent. Robust standard errors in parentheses; standard errors are clustered on geographic indicator variable used for fixed effect. For first three models, excluded Congress is 23rd and 24th (combined because of small number of petitions). Excluded canvassing category is male canvasser and separated columns (often canvassed by women but sometimes with the cooperation of men). For analyses of gender-separated-column petitions, see Appendix. The asterisk denotes that the letters preceding the symbol are a word stem, so that “Christ*” would pick up all prayer language with “Christ,” “Christian,” “Christianity,” etc. Same with “republic*” and “republic,” “republican,” etc.

TABLE 3. Regression of Total Signatures per 1,000 County Residents on Petition Characteristics (antislavery petitions sent to U.S. House, 1833–45)

Notes: Fixed-effects regression with county-congress as unit of analysis; each fixed effect corresponds to county of origin. In first two models, Southern and border states excluded because of absence of antislavery petitions; Plains states excluded because of small population and absence of petitions). Included states for first two models: ME, VT, NH, MA, CT, RI, DE, NY, NJ, PA, OH, MI, IL. Robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered on county. Excluded canvassing category is male canvasser and separated columns. For analyses of gender-separated-column petitions, see Appendix.

With controls for cross-sectional unit and time (each Congress or two-year period), our regressions amount to a differences-in-differences estimate of the influence of women canvassing to women on the level of signatures. (The baseline category is that a petition has been circulated wholly or partially [gender-separated columns] by a man.) Hence in Table 2 the fixed-effects coefficient estimates represent the added signatories on a petition with a woman canvasser, compared with all other petitions that went through the same township, locality, or county in the same Congress. In Table 3 the fixed-effects estimates represent the added signatories per 1,000 county residents with each Congress-specific increase in the percentage of petitions with women canvassers, compared to other Congresses within the same county.Footnote 7

In our fixed-effects statistical models, we find striking differences in petitions circulated by women, beginning particularly in the 25th Congress. Petitions that did not involve women circulating to other women exhibited a mean number of signatures in our sample of 84.9 names. In general (Table 2, full model), petitions circulated by women among women garnered 76 more names on average than did other petitions circulating through the same geographic location at the same time, a 90% increase over the baseline. Yet as reported in the Appendix, it was during the 25th Congress (1837–39) that these effects became apparent, not before. Compared to petitions in the 23rd and 24th Congresses, women-only petitions circulated in the 25th Congress averaged nearly 100 more signatories than did male-only petitions circulated through the same localities.

An important caveat here is that a large portion of the effect from women-only petitions comes from some very large petitions circulated with many thousands of names attached. When the samples are adjusted by excluding petitions with more than 1,000 signatories (Table 2, restricted models) or when the signatory aggregates are logged, the added effect of women-only petitioning persists, but drops by nearly half, to 42 additional signatures per petition.

Our county-level panel regressions (Table 3) demonstrate that, once we control for population, increases in the percentage of women-only petitions are associated with an increase of one antislavery petition signature per 1,000 in a two-year period, an effect that is statistically differentiable from that of gender-separated column petitions. The average level of antislavery petition signatures per 1,000 county residents is 13.7 per Congress in our sample. Each percentage increase in the composition of county petitions that were women-only petitions leads to 0.89 to 0.97 more signatures per 1,000 residents. Because the standard deviation across Congresses of the percentage of petitions that were woman-to-woman is 10.88 percentage points, this means that a one standard deviation increase in the percentage of petitions women-to-women was associated with 9.7 to 10.6 additional signatures per 1,000 county residents, an increase of 70 to 77% from baseline.

MECHANISMS AND LEGACIES OF CANVASSING: WOMEN'S SUFFRAGE AND POST–CIVIL WAR REFORM

Why Did Women Canvassers Gather More Signatures? Persuasion and Political Place

Our petition data suggest, then, that beginning in 1837, women canvassers gathered significantly more signatures than did men passing through the same towns and asking for the same requests (“prayers”). Women's greater efficacy in gathering signatures stemmed from a number of factors, not least their persuasive capacity and their greater legitimacy gained from two sources: (1) their experience in moral reform and evangelical energies and (2) their separation from the party sphere, which was increasingly considered a source of corruption.

As evidence that persuasion was a critical pathway to women's canvassing success, we note that women's canvassing was far more efficacious when the prayer of the petition contained a protest against the gag rule. Figure 4 presents the marginal effect of the percentage of county petitions canvassed by women (in terms of additional signatures per 1,000 county population) as a function of the percentage of county petitions whose prayer focuses on the gag rule. (Numerical results for the marginal effects are presented in Appendix Table A5a, and the underlying regression appears in Appendix Table A5b.) When a county's percentage of petitions with a gag-rule focus is at its mean for the 25th Congress (= 14.68), an additional percentage point of petitions canvassed by women is associated with 1.27 additional signatures per 1,000 county residents. When the county percentage of petitions with a gag-rule focus is 50% (the 95th percentile of the variable, whose maximum is 83.3%), an additional percentage point of petitions canvassed by women is associated with 3.46 additional signatures per 1,000 county residents. The marginal-effects plot demonstrates that the effect of women's canvassing is positive and statistically differentiable from zero for all values of the gag-rule focus variable.

FIGURE 4. Marginal Effects of the Interaction between Women's Canvassing and Petitions Calling for Repeal of the Gag Rule

One question is whether the effect we observe is due to women canvassing or simply more women signing. Our canvassing-centered interpretation is consistent with the observations of contemporaries and other scholars who, studying particular contexts and particular organizations, concluded that women were more effective canvassers, not least because men's political labor was usually paid, whereas women's work was unpaid and more heavily motivated by their spiritual and moral commitments. One scholar, focusing her study on Rhode Island and using primary source documents from Pennsylvania, found that the introduction of female canvassers “immediately tripled the number of petition names secured previously by paid male agents” (Van Broekhoven Reference Van Broekhoven, Yellin and Horne1994: 184). Our aggregate estimates over a 12-year period are much lower than a 200% increase, yet are consistent with the idea that it was female canvassers and not female signatories who accounted for the difference.

Yet at the micro-level, what did canvassing entail? Although we can report only limited features of the archival record here, historical evidence from diaries and letters suggests that women's exhaustive search and recruitment strategies, their circulation in neighborhoods, and their use of rhetoric and persuasion were both challenging and empowering. Table 4 presents some excerpts from our archival research in an important collection of antislavery papers from the Weston sisters of Massachusetts.

TABLE 4. Evidence from Letters between Women Canvassers

Source: Weston-Chapman Papers, Anti-Slavery Collection, Boston Public Library, Boston.

Political Education and Network Formation in the Work of Petition Canvassing

The secondary literature and our archival research suggest that the work of planning a local petition campaign, putting together the petition document, and circulating the petition spatially both opened women to new contacts and networks and developed their skills.

Solicitation and Persuasion

As shown in Excerpt 1 of Table 4, antislavery petitioning was controversial, both because Northern public opinion was not yet behind the radical “immediate abolition” program that many antislavery activists advanced and because women were so active in the movement, stepping boldly outside the “women's sphere.” This latter feature, in particular, differentiated women's petitioning activity from other antislavery activity and from temperance and other benevolence activity, and women active in the cause were quick to note this difference (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998, 91; Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003).

Walking, Traveling, and Network Formation

In the summary of historian Julie Roy Jeffrey, “canvassing with petitions was done door to door, in the same way that women sometimes circulated papers, almanacs and other antislavery material” (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998, 89). Maria Weston Chapman referred to the history of women's antislavery petitioning at this time as “the history of their progress door to door” (Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003, 1, 105). And at a time when paved roads and modern sidewalks were still a thing of the future, women such as Deborah Weston could walk 20 miles or more per week in pursuit of signatures (Excerpt 3).

As Anne and Deborah Weston describe (Excerpt 2 and 3), women regarded the various component activities of petitioning as particularly physically and emotionally taxing. Maria Child remarked that petitioning “was the most odious of all tasks” (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998, 90). Wrote one Sarah Rug, “I have just circulated two petitions, & sent them on, I thought I had got through this unpleasant part of the business for a while; but lo & behold another is forthcoming; so we must make up our minds to keep at the work. . .. You know my sister what humbling work it is, to circulate petitions, & repeat them so often” (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998, 91). The practice of canvassing reinforced ties to other women (Excerpts 1–3, Table 4) and therefore the perception of separate spheres, which had by the 1830s become the basis for public behaviors (Cott Reference Cott1997, chapter 5).

Gathering and Organizing

An important part of the work of petitioning came before and after door-to-door canvassing. In sending blank petitions by mail to other towns and their antislavery sympathizers or societies, in recruiting volunteers to join the canvassing effort, and in following up to see whether certain people had signed the petition (Table 4, Excerpt 2), women did most of the organizational work of the petitions they prepared. Many young women were encouraged and, in a way, subsidized by their mothers (see Diary of Mary Avery White, Appendix). And after the signatures were harvested, women did the hard work of making a backup copy of the petition, gluing different pages of signatures together, and sending the petition to elected officials.

All three of these activities were important features of the antislavery movement whose scope was probably unprecedented in political participation for American women. American women's earlier work in local benevolent societies would not have entailed the level or scope of political work associated with canvassing (Boylan Reference Boylan2002), especially the coordination of petitioning campaigns across localities. And far more than in this earlier work, canvassing, even and especially to other women, who were often reluctant to sign without the approval of their husbands or elders, represented a departure from their previous world of a “separate sphere.”

Historical evidence points to numerous cases where women who were canvassers during the 25th Congress petitioning drive subsequently occupied important activist and fundraising roles in local antislavery organizations (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998; Van Broekhoven Reference Van Broekhoven2002). Many large cities harbored antislavery societies that coordinated much of the work of petitioning; “for societies like Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, which coordinated the work of local groups, the project demanded time, energy, skill, and the ability to direct and supervise effectively” (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998, 88).

These organizing experiences had long legacies. To begin with, many of the founders of the women's rights movement and women's suffrage movement in the United States had their start in antislavery activism, especially petitioning (Lerner Reference Lerner1980; Sklar Reference Sklar2000). Examining the Declaration of Sentiments signed in Seneca Falls, New York—a document commonly regarded as the originating moment of the women's rights and women's suffrage movement—reveals that several pivotal signers had been canvassers in the antislavery petitioning surge of 1837–41. (Like the Declaration of Independence of 1776, the Declaration of Sentiments also mimicked structurally the form of a petition of grievance, with a list of complaints and a signatory list.) More than half of the signers were from a small Hicksite Quaker network in New York (Wellman Reference Wellman1991; Reference Wellman2004), but there is evidence to suggest that critically active members of this network rounded up the signatures of others. Prominent among these was Mary Ann McClintock, one of the five women who planned the Seneca Falls convention. McClintock had just arrived in western New York in 1837, and although she and her husband had founded antislavery societies in the early 1830s, she does not appear on congressional petitions until 1837 and later (notably, her husband does not appear at all in our list of canvassers). Another Seneca Falls signer who had previously canvassed for antislavery signatures was Charlotte Woodward, whose petitioning work most likely represented her very first political work, inasmuch as she was 10 or 11 years old when she canvassed antislavery petitions in western New York (1839) and later signed the Seneca Falls declaration when she was 18.

In many of these cities and towns, women who were active in the explosion of petitioning in the 25th Congress were later active in debates over temperance, over women's rights and suffrage, and over emancipation and abolition in the 1850s and 1860s. These women include Abby Kelley of Rochester, New York (Hewitt Reference Hewitt1984, 105), who along with other petitioners and canvassers later became active in Rochester temperance and suffrage societies (the Ladies’ Washingtonian Total Abstinence Society); Maria Weston Chapman of Boston, who from 1839 to 1858 edited an antislavery book called the Liberty Bell and who through trips to Haiti and Paris solicited support for the American antislavery cause from luminaries like Alexis DeTocqueville (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998); and Elizabeth Buffum Chace (Chace Reference Chace1891, 43), Sophia Little, and Phebe Jackson of what Deborah Bingham van Broekhoven has called “the Rhode Island anti-slavery network” (Reference Van Broekhoven2002, 170–71), who would work in the 1850s and 1860s on issues of women's rights and prison reform. All of these women and more are in our list of identifiable canvassers.

Statistical Evidence from a Sample of Post–Civil War Activists

In his milestone effort The Abolitionist Legacy, James MacPherson showed how abolitionists who were active in antislavery activity before the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 remained militant in a wide array of moral and political reform causes through the end of the nineteenth century, including the women's suffrage campaign (McPherson Reference McPherson1975, chapter 17) and the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP; chapter 20).

McPherson's study was premised on a review of hundreds of archival collections and a sample of 284 post–Civil War abolitionist reformers. We used this sample for several reasons. First, this sample is independent; indeed it was published in 1975, about 30 years before our data-gathering effort took shape. Second, we can rely on the judgment of a well-known and established scholar who has, again independently, measured whether individuals who were active in pre–Civil War abolitionism remained active in post–Civil War reform politics.

We searched for women's names in our petition database using both the last name in the McPherson database and by maiden name; we searched for men using their last name. Where possible, we used available biographical records or consultations with historians to establish the match of names in our database and the names of the reformers in McPherson's study. We counted as an “activist” the status of having been listed in McPherson's database. This raises the question of who counts as an activist or reformer or organizer and who does not. The advantage of using MacPherson's data in this regard is that the founding, maintenance, and leadership of organizations were some of the central criteria he employed in constructing his list (Reference McPherson1975, 6–10).

We limited McPherson's sample to those who were old enough to have canvassed in the period 1833–45. A large proportion of those without birth or marriage dates were thus dropped from analysis. We employed a cutoff of 1830 for birthdate and 1845 for marriage date, yet moving this cutoff by five years in either direction did not change the number of names we could locate. We were able to locate the names of 15 postwar reformers, 8 women and 7 men, who served as identifiable canvassers in our database. Controlling for the preponderance of men in McPherson's data, women were 4.5 times more likely to have been identifiable petition canvassers in our database (p = 0.003 by an exact test), and their odds of having served as canvassers from 1833 to 1845 were seven times as high as those of men (p = 0.003 in an exact logistic regression).

Were Women Canvassers Simply Predisposed to Later Organizational Activity?

The Importance of Timing, Young Women, and Petitioning as a Necessary Mechanism. It is possible that some of the women in our sample were predisposed to become antislavery canvassers and, later on, organizers in other reform movements. Instead of petitioning serving to empower women for activism, perhaps these women were highly participatory well before their antislavery canvassing. Hence petitioning may have been merely epiphenomenal to their general tendency toward political activity. If so, this would render problematic any causal claim that antislavery petitioning generated later activism. Although we cannot rule out some degree of predisposition—ours is an observational study and we are unable to perfectly observe the cognitive and emotional formation of these women's political careers—there are three reasons to doubt that predisposition was so strong as to render insignificant the formative power of canvassing.

A first reason concerns timing. Our data show that women's role in canvassing changed substantially in 1837, after imposition of the gag rule and prominent women's speeches and writings such as the Grimké's (see the epigraph). Given that some antislavery petitioning was occurring before 1837, a predisposition account would predict that these women would have been just as active before 1837, yet they were not.

Second, many of the women in our sample were quite young, teenagers or younger, when they started antislavery petition canvassing. These women simply had no possibility of earlier experience. Among the many examples include Charlotte Woodward, who canvassed in western New York and then signed the Seneca Falls Declaration, and one Lydia Carpenter of Rehoboth, Massachusetts, who was 11 when she canvassed an antislavery petition in Massachusetts (see Figure A1 in the Supplementary Appendix). In both of these cases and others, we can find no evidence that the mothers of these girls canvassed. The juxtaposition of their youth and the gag rule seems to point to an awakening in 1836–37. (Note that our estimated relationship cannot, however, be ascribed to age-related sample attrition, because we control for age in the exact logistic regression (Table 5b).)

TABLE 5. The Preponderance of Women among Abolitionist Canvassers Who Became Post–Civil War Reformers

Notes: McPherson's total sample of abolitionists amounts to 284 persons, of whom 216 are male (76.1%) and 68 (23.9%) are female. More than half of this sample cannot be used because the subjects were plausibly too young to have canvassed from 1833 to 1845 or because birth or marriage data are missing. Dependent variable scored 1 if subject was an identifiable petition canvasser from 1833 to 1845 in National Archives Sample of Antislavery Petitions Sent to House.

Sources: National Archives, Record Group 233 (Records of the U.S. House of Representatives) and McPherson (Reference McPherson1975, 395–405).

Third, we believe that McPherson's sample selects for predisposition. (We cannot, of course, say that he controls for all of it.) And among those petitions canvassed by individuals in the McPherson database, women's average number of signatories was again higher than that of men. Women in the McPherson data gathered an average of 281 signatures across their petitions, whereas men gathered an average of 167. The sample size of McPherson canvassers for whom precise signature data are later available is so small as to render the difference statistically insignificant, yet we note that one of the petitions for which we cannot track down exact signatures is a rolled and sealed petition that likely contains more than 1,000 signatures and perhaps many thousands more. In perhaps the best example of the difference, a husband and wife from the McPherson database had strikingly different canvassing success in 1837: James Gibbons collected 122 signatures in his petition from New York City, but his wife Abigail collected 520 at the very same time.

It is true that the women canvassers in our data were also active in other forms of antislavery activity, such as founding societies. Yet the qualitative and quantitative evidence make clear that petitioning was a necessary, and probably the most important, component of this formative experience. After 1837, with the passage of the gag rule and the advocacy of the Grimké sisters, women understood that petitioning was unique (see Table 4 Excerpts; Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998; Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003) and that it was their “momentous duty. . .to petition our national Legislators. . .[as it] is the only mode by which females can publicly make known their grievances” (Philanthropist, December 5, 1837; quoted in Van Broekhoven Reference Van Broekhoven, Yellin and Horne1994, 183). Our work provides evidence for the unprecedented degree of women's political engagement with national political issues from 1837 to 1841; only the anti-Cherokee removal campaign (Portnoy Reference Portnoy2005), which attracted a smaller number of signatures and a handful of canvassers (Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003: 185, note 4), would qualify as a precedent. Temperance petitioning was also common but involved state legislatures, and women's participation in that campaign was not nearly as revolutionary in the early Republic. Before the antislavery petitioning explosion of 1837–41, women were not so openly engaged in the political sphere and were instead active in benevolence and moral reform societies (Flexner and Fitzpatrick Reference Flexner and Fitzpatrick1996, 48). Their activities did not enter the formal realm of U.S. congressional politics. And where they were active in organization building in the early 1830s, petitioning was recognized to be a new form of activity (Boylan Reference Boylan2002; Hewitt Reference Hewitt1984; van Broekhoven Reference Van Broekhoven, Yellin and Horne1994, 181). The timing of these patterns shows that any effect we observe cannot be the result of already politically mobilized women choosing petitioning as one of many other things that they wished to do in the 1830s. If some women self-selected into activism, petitioning was nonetheless a necessary throughway to activism that they took in their political lives.

In an ideal quasi-experiment, we could compare women who were active in canvassing from 1833 to 1845 to those women who were not, and ask whether those who had canvassed had careers in activism different from those who did not canvass. The difficulty here is that the population of women who did not canvass is massive (many millions of individuals), and their lives, like most women's lives in the nineteenth century, are poorly documented. What we are able to do, given the limitations of the data, is to use an independent sample in which subjects have been preselected for activism and organization building (McPherson Reference McPherson1975, 6–10, 395–408) and to demonstrate that, among these activists, women were far more likely to have canvassed petitions in a historical period (1837–41) that is known to be formative for them.

For several reasons, our study probably underestimates the force of canvassing. It is difficult to trace women biographically, important records of other petitions (to Congress from the late 1840s and 1850s, or to New York State, where a large archival fire destroyed records in 1913) have been lost, and women's contributions to nineteenth-century reform movements have often been systematically understated.

LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

Political participation is not merely about trying to influence policy but also about trying to induce others to participate and give voice. A crucial advantage of studying petitions is that, in many cases, they lend themselves to analysis of those who requested others to participate (sign and canvass), as well as those for whom the requests met with success (the signatories). To date, we believe that this is the first social-scientific study to examine the differential work of petition canvassers—not only as signature gatherers but also as those organizing the effort of mass petitioning—as well as the first to follow canvassers in their later careers.

In this article we claim that petitioning can empower those engaged in canvassing to become more active in leading and organizing reform movements, including those other than the ones for which they originally canvassed. Canvassing involves its participants in the essential work of persuasion, it introduces them to others who may think like them (facilitating new consciousness and new networks), and it entails organizing activity that is portable to other political causes. Our historical study demonstrates that the explosion of women's antislavery canvassing from 1837 to 1841 worked through these mechanisms to shape patterns of activism and organization that endured long past abolitionism itself. For American women, the canvassed antislavery petition became both a political training ground and a meeting place where dialogues, contacts, and identities were forged.

It is of course difficult to generalize how petition canvassing shapes later activism by studying one movement. Yet important contributions to the study of mobilization have, like our endeavor, focused on the rich data contexts of particular movements to form hypotheses and lessons for more general study. In addition, the American antislavery movement was controversial and consequential as few movements have ever been. It helped set an agenda for the abolition of slavery (McPherson 1998; Stewart Reference Stewart1997).Footnote 8 It contributed to women's activism in pressing for women's rights and especially suffrage rights (Flexner and Fitzpatrick Reference Flexner and Fitzpatrick1996; Lerner Reference Lerner1980; Yellin and van Horne Reference Yellin and Van Horne1994). It helped train men and women, white and black, in activism for decades of later reform efforts (McPherson Reference McPherson1967, Reference McPherson1975). Our analysis demonstrates that, in the context of one of the most consequential movements of American and even world political history, women were active in petition canvassing as never before; that women regarded canvassing as the most novel and arduous of their tasks; and that (conditional on having lived long enough) these petition canvassers stayed active in politics for decades if not a half-century.

Our study demonstrates the added utility of combining qualitative data from women's letters and diaries with quantitative data on their activity (see Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Scholzman and Verba2001 for a modern example). Our hope is that, although certainly constrained by space limits, the qualitative evidence examined in the article helps establish most plausible mechanisms that can account for the larger aggregate patterns observed. To be sure, there are many uses for qualitative and historical research other than the examination of mechanisms (e.g., Lee Reference Lee2002; Walsh Reference Walsh2004, Reference Walsh2007, Reference Walsh2012). Yet when particular individuals can be studied through their narratives as well as in their status as “data points” in a larger quantitative exercise, the context of information is correspondingly richer than without the narrative evidence.

To be sure, the quantitative and qualitative endeavors in this article are limited by their nonlaboratory setting. It is not possible to truly randomize, in a prospective fashion, the “treatment” of having canvassed an historical petition. Diaries and personal reflections can be themselves contaminated by many biases, including over- or under-estimation of personal efficacy, imperfect or biased recall, or nonrandom preservation of records. We cannot observe emotions and motivations with the precision of, say, a psychological experiment or even a study based on participant observation.

Yet the turbulent, high-stakes settings of historical politics create conditions for the study of activism and mobilization than can rarely, if ever, be replicated in the laboratory or in a field experiment setting. For one, the act of signing a petition as controversial as that calling for the partial abolition of slavery, in a context as charged as that of the 1830s United States, is difficult if not impossible to reproduce in a laboratory, a survey, or even an ethnographic setting. Put differently, although experiments and surveys allow for controls and measurement, the historical significance of the context we are studying amounts to a form of external validity that few if any experiments or surveys can match.

Second, the development of an “activist” or organizer is a process that probably takes many years and perhaps decades. When it comes to founding organizations, initiating reform agendas, and leading others to invest and sacrifice in movement politics, the kinds of actions taken are not easily observed or measured in the laboratory or survey setting. The process by which people become active in political movements is a crucial one, and it is not surprising that many of the most celebrated studies of movements in the social sciences (e.g., Calhoun Reference Calhoun2012; Clemens Reference Clemens1997; Lee Reference Lee2002; McAdam Reference McAdam1999; Parker Reference Parker2009b) have thus used a mix of quantitative and qualitative data drawn from data-rich historical contexts. The study of petitions and petitioners can serve centrally to advance this enterprise.

PRIMARY SOURCES

Chapman-Weston Papers and Anti-Slavery Collection, Boston Public Library, Boston.

Mary Avery White Diary, typescript, Mary Avery White Papers, Worcester, MA.

Oneida County Historical Society Pamphlet Collection, Oneida County Historical Society, Utica, NY.

Petitions to the Massachusetts General Court, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston.

Petitions to the U.S. House of Representatives, Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, Record Group 233, National Archives, Washington, DC.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S000305541400029X

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.