Introduction

The city of Saguntum was a strategic Iberian trade centre located on the hill of the castle in present-day Sagunto, in in the southern foothillss of the Sierra Calderona, about 30 km north of the city of Valencia. The topography of Saguntum ensured that it became a privileged acropolis throughout its history. The city went through several building phases over the centuries, leaving behind the remains of numerous buildings and fortifications. It is therefore not surprising that the term castle has been used to describe the nature of this site and its current citizens are proud of the name of Sagunto, inherited from the Classical tradition.

Hannibal's attack and conquest of Saguntum at the outset of the Second Punic War (218–202 bc) led to the city's growing popularity, as recorded in Classical texts. Saguntum suffered a long siege and, despite its request for help, Rome's protection was not offered to the city.

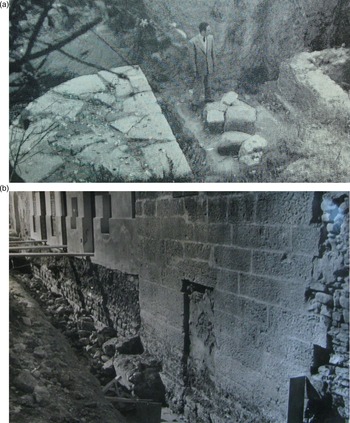

The city's strategic location and excellent terrestrial and maritime communications are especially relevant. The main coastal road, the Via Augusta in the imperial period, and the route from the coast to the Celtiberian interior of the Iberian Peninsula, make Saguntum a privileged enclave. Grau Vell, Saguntum's Mediterranean trading port, was located only 2 km away. The topography of the castle and the bed of the river Palancia influenced the city's development, determining its urban boundaries during the early Roman imperial period. Saguntum lies on several terraces along the margin of the river, which ascend to incorporate the theatre, the forum, and the western area at the top of the castle (Aranegui-Gascó, Reference Aranegui-Gascó and Dupré Raventós1994; Reference Aranegui-Gascó, Ribera i Lacomba and Jiménez Salvador2002) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Sagunto in Spain.

Main constructions mentioned in the text: (1) Circus; (2) Solar de Quevedo (Quevedo site); (3) the bridge; (4) plaza de la Morería (Morería Square).

After the war against Carthage, the city was reconstructed with the help of Rome. This favoured the expansion of urbanized areas and, during the era of Augustus, Saguntum was one of the main Roman cities in Hispania; even in the later Roman Empire it held great economic and political power on the Mediterranean coast. A period of important social, cultural, and urban change took place in Saguntum. Similarly, a change in the administrative status of other Hispanic cities took place took place after the implementation of the colonizing policy of Caesar and Augustus.

Saguntum's legal system as an allied city was modified, at least by 56 bc (Cicero, Pro Balbo, 9.23), when it became a Roman colony, as deduced from the legends figuring on coinage (Ripollès & Velaza, Reference Ripollès and Velaza2002). Under the reign of Augustus, the city was a Roman city, as can be observed on coins, particularly on an inscription dated in 4–3 bc (CIL II2/14, 305, Alföldy, Reference Alföldy2012)(CIL II2/14, 305, Alföldy, Reference Alföldy2012) and from a quote by Pliny (‘Saguntum … a town with Roman citizenship, famous for its loyalty’; Natural History 3,20). Furthermore, urban and stylistic changes, influenced by the presence of Augustus in Tarraco between 15 and 12 bc, are also visible in some cities in Hispania. Saguntum plays a significant role in the strengthening of monumentality at this time, as attested by a building programme undertaken both inside and outside the city walls.

The New Urbanism in the Early Imperial Period

The new city was organized along several roads, oriented from north to south, which crossed the town. One of them, located in front of the circus, connected the porta triumphalis with the public square that will be described below. Further archaeological investigations identified an original stretch of road to the east of the municipality, in Plaza de la Morería (Benedito-Nuez, Reference Benedito-Nuez2015; Ferrer-Maestro et al., Reference Ferrer-Maestro, Benedito-Nuez and Melchor-Monserrat2018). Another segment was found in Avenida País Valencià. These roads were parallel to the Via Augusta; they were connected to the city wall so as to give access to the upper town, where the theatre and forum were located. These roads spread over an area of more than 60 hectares, their irregular layout due to their adjustment to the local topography.

In the present-day city of Sagunto, some new streets still overlap with Roman streets. So far, research has focused on the northern part of the city, especially on a N-S street (the cardo) that went through Carrer del Castell and Carrer Major. This is the area where the hermitage of San Miguel can be found. At this point, the N-S street would have cut the E-W axis (the decumanus), which probably gave access to the eastern part of the city. This E-W road ran through Carrer Major, crossed Plaza Mayor, and went down Carrer de Cavallers to the Teruel gate, that is, the western access to the city (Aranegui-Gascó, Reference Aranegui-Gascó2004; Hernández-Hervás, Reference Hernández-Hervás and Ripollès2004). The remaining streets are parallel to the cardo and the decumanus, and the space was divided into different insulae. As previously seen in Plaza de la Morería, public buildings (temples) or private buildings (domus and mausolea) occupied each insula. From the early imperial period onwards, the embellishment of the area outside the city walls would become a clear political objective intended to include the periphery into the urban fabric (Benedito-Nuez, Reference Benedito-Nuez2015).

The Circus

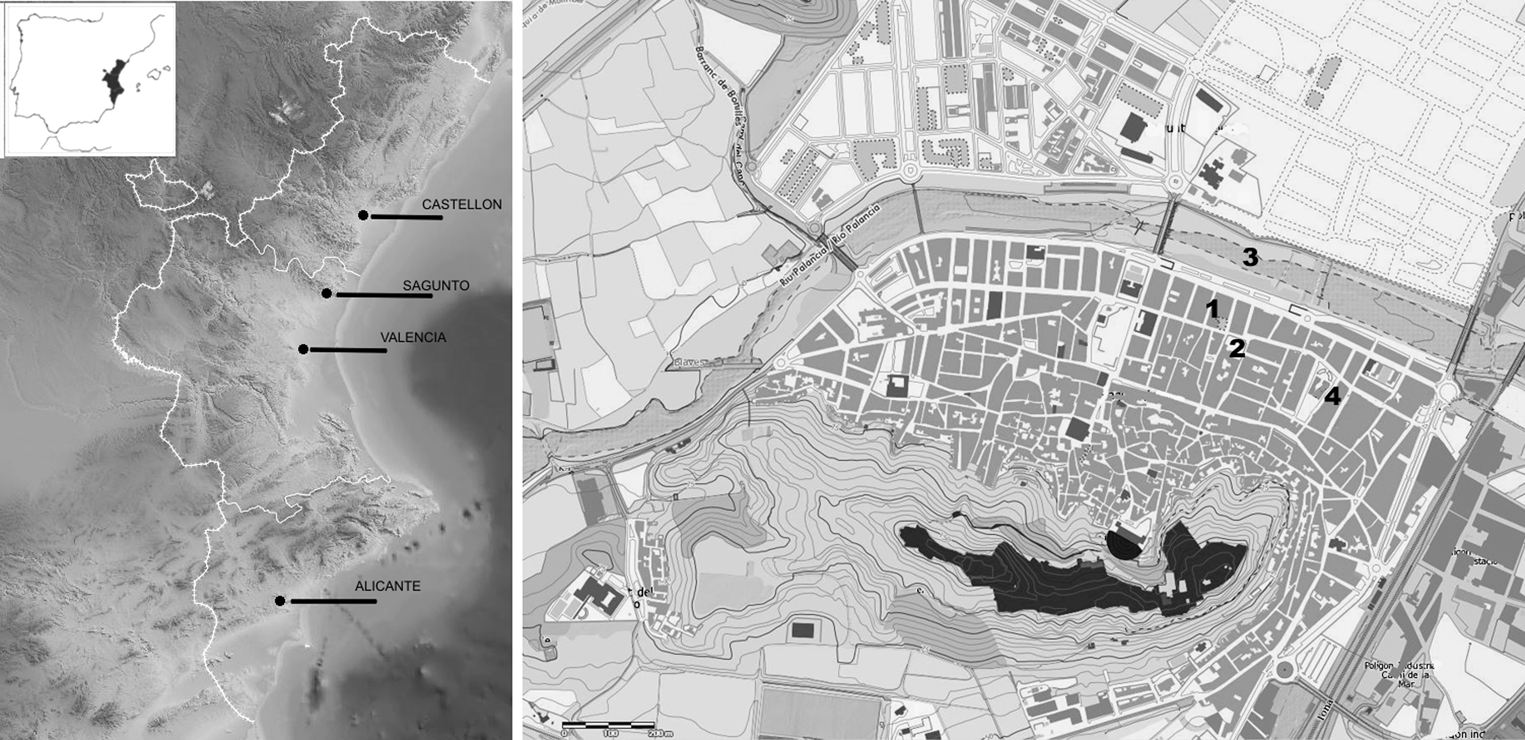

The Roman circus was built in the suburbium of Saguntum's traditional heart, outside the walled perimeter of the city. It extended along the southern bank of the river Palancia and was oriented East-West. It was an area with good communications but was also dangerous because of the floods of the river. Astonishingly, the remains of the circus were never declared a historical monument. Unprotected by the authorities, they disappeared in the 1960s when the plot was classified as land suitable for building (Melchor- Monserrat et al., Reference Melchor-Monserrat, Benedito-Nuez, Ferrer-Maestro, García, Buchón and López Vilar2017). The Roman circus has a considerable importance within the monumental urban plan of Sagunto. Its presence is attested in the writings of erudite travellers and chroniclers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and in 1888 the local historian A. Chabret identified the porta triumphalis, the spina, the euripus, and some hydraulic pipes (Chabret-Fraga, Reference Chabret-Fraga1888). Another notable historian of Sagunto, Santiago Brú, described it in detail in the twentieth century (Brú i Vidal, Reference Brú i Vidal1963) (Figures 2a-b).

Figure 2. a and b. Spina of the circus (Bru, Reference Brú i Vidal1963), wall of the opus quadratum of the circus (archive of the Saguntine Archaeological Centre).

A broad chronology that takes account of the dimensions of this building can be established, starting in the middle of the second century ad (e.g. Hernández-Hervás et al., Reference Hernández-Hervás, López Piñol and Pascual Buyé1996; Pascual Buyé, Reference Pascual Buyé, Nogales and Sánchez Palencia2002; Aranegui-Gascó, Reference Aranegui-Gascó2004). It coincides with a time of intense building activity in the city, with an extraordinary impact documented by archaeological investigations (Melchor-Monserrat & Benedito-Nuez, Reference Melchor-Monserrat and Benedito-Nuez2005a; Benedito-Nuez, Reference Benedito-Nuez2015; Machancoses López & Jiménez Salvador, Reference Machancoses López, Jiménez Salvador and López Vilar2017; Ferrer-Maestro et al., Reference Ferrer-Maestro, Benedito-Nuez and Melchor-Monserrat2018). Similarly, Corell's study of the inscriptions of Sagunto (Corell Vicent, Reference Corell Vicent2002) established a link between the circus building and a fragment of a monumental inscription found on the castle hill. This inscription, which dates to the third century ad, commemorates a donation for the celebration of theatrical or circus performances: ]C / [- - -]nses / [- - -] MCCL / [ (CIL II2/14, 376, Alföldy, Reference Alföldy2012).

In previous research (Melchor-Monserrat et al., Reference Melchor-Monserrat, Benedito-Nuez, Ferrer-Maestro, García, Buchón and López Vilar2017), the proximity of the circus to one of the main communication arteries has been highlighted. It has been claimed that its location broke up the architectural project of Augustus' time, since the layout of the Via Augusta was cut at the exit of the bridge giving access to the city (Olcina Doménech, Reference Olcina Doménech1987; Aranegui-Gascó, Reference Aranegui-Gascó2004). This odd spatial configuration would have been an obstacle in terms of closeness to the theatreand forum. Perhaps we should consider that building the bridge and detour of the Via Augusta was necessary to avoid creating problems of access to the circus. As is known, viaducts and roads linked to entertainment buildings were built in other Hispano-Roman cities to give quick access to the city, making it possible to increase the number of visitors coming from other towns.

In Saguntum, a branch went from the Via Augusta, at the location of a suburban villa known as Muntanyeta de l'Aigua Fresca, to reach the bridge that gave access to the circus. By means of a photogrammetric restitution process, using photographs taken during the Italian bombings of 1937 and 1938 in the Spanish Civil War, and orthophotography of the Valencian Cartographic Institute in 2012, it has been possible to work out a plan of the circus during its first quarter of a century of existence. The spina, the limits of the cavea (dashed lines), and even traces of the building that surrounded the tribunal iudicum can be clearly distinguished in the images (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Location of the circus overlaid on a present-day aerial photograph of the area (after Melchor et al., Reference Melchor-Monserrat, Benedito-Nuez, Ferrer-Maestro, García, Buchón and López Vilar2017).

The cavea would have been 11 m wide and 474 m long. Taking into account the end of the spina and the cavea, and comparing the space between the meta and the carceres in other Hispanic circuses, a working hypothesis can be suggested. It starts from the idea that the maximum length of the circus should be between 270 and 290 m. Moreover, the photograph taken in 1938 allows us to specify the length of the foundation as 237 m, while its total width would have been between 68 and 70 m (Melchor-Monserrat et al., Reference Melchor-Monserrat, Benedito-Nuez, Ferrer-Maestro, García, Buchón and López Vilar2017).

Bearing all these issues in mind, let us note that the surroundings of the circus were urbanized. The city was growing towards the lower areas, practically reaching the river Palancia, as suggested by the significant discoveries in the Morería and Quevedo sites (Melchor-Monserrat & Benedito-Nuez, Reference Melchor-Monserrat and Benedito-Nuez2005a, Reference Melchor-Monserrat and Benedito-Nuez2005b; Machancoses López & Jiménez Salvador, Reference Machancoses López, Jiménez Salvador and López Vilar2017; Ferrer-Maestro et al., Reference Ferrer-Maestro, Benedito-Nuez and Melchor-Monserrat2018). These archaeological investigations revealing the remains of hydraulic infrastructure, public and domestic buildings, and place of worship with at least one excavated temple, have been crucial for our understanding of the ancient urbanism of Saguntum.

The Bridge

It has been suggested that several viaducts were built over the course of the river Palancia. These connected the entrance gate to Sagunto as an urban space surrounded by burial areas, where some of the most popular monuments were located. However, studies remain scarce; C. Aranegui-Gascó and M. Olcina Doménech (Reference Aranegui-Gascó and Olcina Doménech1983) described some remains and mentioned the problems related to the access to the city, in particular whether three bridges connected with the Via Augusta. One was in front of the circus, the second might be located under the railway bridge, and the third, to the west, would be linked to the Teruel road.

So far, preserved remains have been few and correspond to one of the viaducts, which links the circus with the Via Augusta. The most outstanding elements of this bridge are the abutments used to support the arches, whose ruins are scattered all over the riverbed. It is even more difficult to establish the chronology of the other bridges, set under the railway and near the road to Zaragoza, because detailed research is scarce (Benedito-Nuez, Reference Benedito-Nuez2015; Ferrer-Maestro et al., Reference Ferrer-Maestro, Benedito-Nuez and Melchor-Monserrat2018).

Information from the nineteenth century can shed some light on the bridge next to the circus: its ruins were then partially visible, as Enrique Palos reported: ‘… the half circle of the eastern part [of the circus] … in the middle of which two piers are identified. They undoubtedly formed part of the bridge leading to Rome … At the end of the circus, towards its upper part, two arches of another old bridge can be seen, while three piers with two arches can be observed in the riverbed’ (Palos y Navarro, Reference Palos y Navarro1804; authors’ own translation).

In addition, photographs of the 1960s kept in the archives of the Saguntine Archaeological Centre show excellent masonry work, with the core of the bridge's piles were filled with opus caementicium (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Pier of the Roman bridge on the northern bank of the river Palancia (archive of the Saguntine Archaeological Centre).

The Public Square

As part of the embellishment and monumental planning of the Saguntine municipium in the second century ad, new public and private buildings continued to be established in the city. This included a huge monumental building or enclosure built on the southern flank of the circus. It was erected on the Quevedo site, which is located between Carrer Horts, Carrer del Remei and Carrer Ordóñez The remains were discovered in the area of the old orchards of the Trinity Convent, which were cleared in the 1980s. These remains consist of a wall built in opus quadratum and a large entrance made of squared ashlars and flanked by pillars.

The oldest references to this site can be found in drawings made by Mariangelo Accursio in the sixteenth century. It is known that this outstanding Italian humanist, who was active in Spain between 1525 and 1529, drew the facades and ten inscriptions, seven of which are preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Sagunto (CIL II2/14, 337 to 346, Alföldy, Reference Alföldy2012). The epigraphic evidence indicates that the monument was dedicated to three members of the Sergii family, one of the most influential families in Saguntum, before the construction of the circus (Corell Vicent, Reference Corell Vicent2002). The site housed the Roman temple of Diana, according to the seventeenth-century historian Escolano cited by the politician and writer Pascual Madoz in his well-known Diccionario (Reference Madoz1848). The chronicler Chabret-Fraga (Reference Chabret-Fraga1888), an eyewitness, writes that the remains of a mosaic destroyed by excavation works were found in the garden of the former monastery of the Trinity. Only a fragment half a metre long could be identified. It had a white background with a black border resembling a meander design (SAV, 1873).

The latest archaeological excavations carried out on the site at the end of 2014 revealed a portico, an entrance with two monumental pillars,, and a sewer. The beginning of the sewer, which may have been paved, would have been in the centre of an open space (Melchor-Monserrat & Benedito-Nuez, Reference Melchor-Monserrat and Benedito-Nuez2005b). The main entrance would probably coincide with a street that would reach the area of the porta triumphalis of the circus from the walls. At the same time, the road axis that today corresponds to Carrer Horts would have separated the circus from the square (Ferrer-Maestro et al., Reference Ferrer-Maestro, Benedito-Nuez and Melchor-Monserrat2018). Despite the relevance of the findings, the latest archaeological investigations on the site have not yet been published (Figure 5 a-b).

Figure 5. a and b. Opus quadratum foundations and walls of the largest public square documented in Sagunto.

The Temple

Classical texts refer to the existence of a temple dedicated to Venus (Polybius, Histories 3.97.6–8) and to a second temple dedicated to Diana (Pliny, Natural History 16.216). In recent studies, a building located on the forum has been identified as a temple to Heracles (Aranegui-Gascó, Reference Aranegui-Gascó1992, Reference Aranegui-Gascó2004) although no inscription linking this space with the worship of a god has been found. Other scholars state that other temples existed in the area (Beltrán-Villagrasa, Reference Beltrán-Villagrasa1956; Etienne, Reference Etienne1958) but so far no evidence has come to light.

The remains found in the excavations of Morería, on the east side of the N-S road, have been related to a temple, even though no epigraphic evidence has been discovered and the building has not yet been interpreted in all its complexity (Melchor-Monserrat & Benedito-Nuez, Reference Melchor-Monserrat and Benedito-Nuez2005a; Ferrer-Maestro et al., Reference Ferrer-Maestro, Benedito-Nuez and Melchor-Monserrat2018). Nonetheless, this building is of great archaeological value. It includes a massive masonry foundation 1.53 m wide; the walls have the same width and are made with large cobbles from the river and limestone ashlars. The opus quadratum technique, bedded ashlars, and traces of a spout and gutter have only survived in the north-western corner of the building. The eastern facade measures 8.47 m and stands on a podium. Unfortunately, only the eastern half could be excavated (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Archaeological excavations of the medieval walls that covered the remains of the temple next to the Roman road entering Saguntum.

Along with these architectural remains, fragments of ornamental elements that decorated the interior of the building were recovered during the excavation: smooth panels, moulded pilaster slabs, friezes with vegetal motifs, mouldings, and fragments of a opus sectile pavement. These elements were made with marble of Buixcarró, Broccatello, Rosso antico, and Luni-Carrara types (Ferrer-Maestro et al., Reference Ferrer-Maestro, Benedito-Nuez and Melchor-Monserrat2018).

The Honorary Arch

In the section above on ’The new urbanism in the Early Imperial Period’, we pointed out that between the first and second centuries ad there was a profound transformation of the main public spaces in the town. They extended beyond the walled limits of the town, which undoubtedly demonstrates the importance of the monumental landscape erected outside the walls. This image of Saguntum was completed by the construction of an honorary arch, which was discovered in the excavations carried out in Plaza de la Morería. Due to its exclusive nature, this honorary arch is of great significance in the research conducted on the Roman municipality and its surrounding territory.

In the literature on Roman arches, research has tended to focus on analysing the documentation that is available from an archaeological perspective and from the epigraphic and literary evidence. These studies have generally addressed issues related to the historical context of arches, their architectural definition, and theirfunction.

Studies undertaken by Rossini (Reference Rossini1836), Graef (Reference Graef and Baumeister1888), Frothingham (Reference Frothingham1915), Kaehler (Reference Kaelher1939), Mansuelli (Reference Mansuelli1954), Pallottino (Reference Pallottino and Bianchi Bandinelli1958), Arce Martínez (Reference Arce Martínez1987), De Maria (Reference De Maria1988), Wallace-Hadrill (Reference Wallace-Hadrill1990), Gros (Reference Gros1996), Beard (Reference Beard2007), and Kontokosta (Reference Kontokosta2013), are the most frequently cited works concerning Roman arches, including analyses of the epigraphic and literary records and the archaeological evidence for these monuments. In general, research has addressed issues related to their historical context, their architectural definition, and their function as urban embellishment and propaganda.

Such arches were built in the monumental centres of the cities, especially in the forums, and in areas where communication routes crossed a river or a territorial boundary. In the Iberian Peninsula, there are different types of arches with different ideological connotations. In some cases, they were the result of public initiatives, whereas in other cases, it was the will of the citizens themselves that led to their erection. The model followed was born in Rome in the Republican era, and was extended by Augustus throughout the provinces of the empire (Dupré Raventós, Reference Dupré Raventós1998: 159). Sadly, only a few of these arches have survived to the present day.

In Hispania, architectural remains are not common: the arch of Cabanes, in Castellón (Valencian Community), erected on the Via Augusta, seems to have been a private commission (Abad Casal, Reference Abad Casal1984; Abad Casal & Arasa i Gil, Reference Abad Casal and Arasa i Gil1988). The extra-urban arch of Berà (Catalonia) was also built on the Via Augusta, some 20 km from Tarraco, at the end of the first century bc (Dupré Raventós, Reference Dupré Raventós1994a). Similarly, the Martorell arch is located on the north-eastern boundary of the territory of Tarraco, at one end of a bridge known as Pont del Diable that crosses the Rubricatus (now the river Llobregat) (Dupré Raventós, Reference Dupré Raventós and Dupré Raventós1994b; Gurt & Rodà, Reference Gurt and Rodà2005). In the central part of the emblematic Alcántara bridge in Cáceres that crosses the Tagus in Extremadura, an arch dedicated to Emperor Trajan was built built (Blanco Freijeiro, Reference Blanco Freijeiro1978; Liz Guiral, Reference Liz Guiral1988). The arch of Medinaceli, in Soria, Castile and Leon, is located at the top of the Jalón valley, near the road that linked Caesaraugusta (Zaragoza) with Augusta Emerita (Mérida) (Blanco Freijeiro, Reference Blanco Freijeiro1981; Abascal & Alföldy, Reference Abascal and Alföldy2002; Abad Casal, Reference Abad Casal2004). This monument was part of the wall that surrounded the city at the end of the first century ad. The tetrapylon of Capera, present-day Cáparra (province of Cáceres, northern Extremadura) was raised next to the forum, probably in the Flavian era (García y Bellido, Reference García y Bellido1972–74; Nünnerich-Asmus, Reference Nünnerich-Asmus1996a and Reference Nünnerich-Asmus1996b; Cerrillo, Reference Cerrillo Martín de Cáceres2006). The arch of Myrtilis Iulia in Mértola, Portuguese Alentejo, is located at the access gate to the forum, in the area of the citadel (Martins Lopes, Reference Martins Lopes2014: 51).

The origin of some isolated architectural remains of other arches is not clear. For example, the monument of Ciempozuelos, near Titulcia the Community of Madrid, presumably located on a route that has not been identified archaeologically, is known from Classical itineraries (Nünnerich-Asmus, Reference Nünnerich-Asmus1996–97). In the city of Edeta, now Llíria in the Valencian Community, the remains of an entrance arch to the city are dated to the end of the first century ad. They are located in the area called Pla de l'Arc, next to the road leading to Sagunto, and epigraphic fragments of an honorary nature have been found nearby. Tradition has considered that the pillar corresponds to a Roman arch but, as recently suggested, it could belong to one of the sides of an arch-shaped door of a public building (Escrivà, Reference Escrivà and Olcina-Doménech2014). The keystones of the arch at Corduba, Córdoba, probably formed part of a monumental entrance to the city's forum (Marcos Pous, Reference Marcos Pous1987; Márquez, Reference Márquez1998; Monterroso Checa, Reference Monterroso Checa2011), although the arch may have flanked a religious building (Márquez, Reference Márquez1998: 175).

The remains found in Málaga (Community of Andalusia) and in Italica in the province of Seville are scarce. Only the winged victory figures of the keystones have survived at both sites (García y |Bellido, Reference García y Bellido1949, Reference García y Bellido1972). Apart from these constructions, the arch adorning the access to the forum of the city of Lucentum, present-day Alicante, is of great archaeological value. Such an arch, which may have closed the W-NW inside of the public square (Olcina Doménech et al., Reference Olcina Doménech, Guilabert, Tendero, Àlvarez, Nogales and Rodà2014: 826; Olcina Doménech et al., Reference Olcina Doménech, Guilabert, Tendero and López Vilar2015: 258–59) stands out due to its location. As for the Trajan arch in Mérida, it may correspond to the monumental access to the provincial forum (Arce Martínez, Reference Arce Martínez1987). In Tarraco, there is an arch located in the forum that is related to Augustus' victories on the peninsula (Dupré Raventós, Reference Dupré Raventós and Dupré Raventós1994b; Mar et al., Reference Mar, Ruiz de Arbulo, Vivó, Beltrán and Gris2015).

Other arches are known from epigraphic fragments (Figure 7). Jérica is located 40 km from Sagunto, in the interior of the province of Castellón. In this locality, there was a Roman arch that could have been built during the Antonine period, its exact location remaining unknown (Abad Casal, Reference Abad Casal1984). Inscriptions alluding to the construction of arches and statues have been found in urban centres but, according to Beltrán Lloris Lloris (Reference Beltrán Lloris1980), the inscription from Jérica, which belongs to a tombstone, is different. Jérica is not a municipality given that no inscription referring to any magistrate has ever been found. Nonetheless, the area was home to a wealthy family since it spent a large sum of money on a private construction (Ferrer-Maestro, Reference Ferrer-Maestro1984–85).

Figure 7. Jérica inscription. The text reads: ‘Quintia Proba built an arch for herself, Porcio Rufo and Porcio Rufino, and decorated it with statues for the sum of forty thousand sesterces’ (CIL II2/14, 745, Alföldy, Reference Alföldy2012). Municipal Museum of Jérica.

In May 2018, the Institute of Iberian Archaeology of the University of Jaén announced that it had located the arch of Ianus Augustus in Mengíbar in the province of Jaén. It was erected at the end of the first century bc at the point where the Via Augusta crossed the Baetis (Guadalquivir), which is the territorial boundary between the provinces of Baetica Ulterior and Citerior. So far, it is only known from epigraphic sources (Sillières, Reference Sillières1981).

Outside the Iberian Peninsula, the Sergii arch in Pola (Pula, Croatia) deserves special mention among many other similar monuments. It was built by members of this family at the end of the first century bc in front of one of the entrance gates to the city (Traversari, Reference Traversari1971).

There are many examples of arches at at milestones and crossroads in Italy. The arch of the Gavi in Verona was built around the middle of the first century ad on a section of the Via Postumia, outside the city walls, a few metres from the Porta Borsari (Tosi, Reference Tosi1982). An arch was built in Pisa in memory of Gaius and Lucius Caesar in ad 6 (Arce, Reference Arce Martínez1987). In Pompeii, arches were erected on the roads, and fountains were built nearby, as in Sagunto (Giuntoli, Reference Giuntoli1989). In Rome, the variety and purpose of the arches are well known.

In the city of Sagunto, the excavations led by members of our research group in Plaza de la Morería have documented the existence of an arch located near the temple (Figure 8). It is an honorary construction that fits in with the monumentality of the lower part of the city during the High Empire. The remains of this arch have been found at the junction of the Morería and Grau Vell roads; the former is oriented north-south, leading towards the river Palancia, whereas it has been suggested that the latter started at a harbour in Grau Vell, entered the city, went past the circus, and then continued northwards towards the municipium of Bilbilis and the city of Caesaraugusta (Zaragoza), along the route that is today's Calle Huertos. The construction of the arch coincides with the building of a new monumental complex set in a sacred area in the lower part of Saguntum. It is dominated by a temple, and the design of a porticoed pavement next to the road paved with grey dolomitic limestone slabs reinforces the character of the road as a main artery.

Figure 8. Plan of the Morería site with foundations of the arch (1/1'), temple (2), and; building of the second century ad (3).

It is not known what the arch looked like since only a heavy foundation has survived. It was formed by two large, rough and unrefined architectural or sculptural pieces made of opus caementicium and ashlars, and limestone mouldings. Its span measured 3.5 m. The foundation would have gone across the road,, coinciding with the end of the portico, forming a kink in the orientation of the road.

The excavation of the foundation of the arch began at the south-western corner of the eastern pillar because it was likely to provide more information about the monument. After removing between 30 and 40 cm of soil, several epigraphic fragments related to this monument were found in the fill next to its base (Figures 9 and 10). They are the fragmentary remains of three monumental inscriptions of the end of the first and the beginning of the second century ad, dedicated to some prominent public figure. Corell and Seguí (Reference Corell and Seguí2008: 77–80) believe these fragments relate to an imperial inscription, but other scholars point out that the inscription was by a consul or a senator (Ferrer-Maestro et al., Reference Ferrer-Maestro, Benedito-Nuez and Melchor-Monserrat2018: 371). The inscription reads: [---] · co[(n)[suli) · p(atri) p(atriae)] ? [---] · P[---]s · d(e) · s(ua) [· p(ecunia) · f(ecit)] ?

Figure 9. Eight fragments of a Buixcarró marble plaque. The epigraphic design is delimited by a straight cyma that measures 3.7 cm visible at the bottom. Both the front and the back faces are polished. Dimensions: a) (13) × (17) × 3.1–2.6 cm; b) (9) × (13) × 2.5–2.2 cm; c) (11.5) × (17) × 2.4–2.0 cm; d) (3.7) × (5) × 2.9 cm; f) (8.5) × (15.5) 2.3 cm; g) (1.9) x (5) ×2.4 cm;. Inscribed letters: line 1: 5.7 cm high; line 2: 4.3 cm high. Archaeological Museum of Sagunto.

Figure 10. Foundation of the eastern pillar of the arch, next to the slabs of the road in the Plaza de la Morería, Sagunto. Above the pillar, the wall of the eastern facade of the temple is visible.

Archaeological excavations revealed the foundation trench of the arch, which reached a depth of 1.55 m on the eastern side of the piece of opus caementicium. It was intended to provide the building with a firm foundation. The top of the foundation was flat; two bluish-grey dolomitic limestone slabs consisting of headers survived on the western side of the road and a similar slab survived on its eastern flank. The dimensions of the slabs vary. On the western side, there were originally 6 slabs on the road that would delimit a space 3.04 m long and 2.99 m wide. The two slabs still in situ were 1.80 × 1.03 m, and 1.30 × 1.01 m respectively. On the eastern flank of the road, 6 slabs delimited a space 3.65 m long and 2.80 m wide. The remaining slab is 1.40 m long and 1.06 m wide, with a moulding preserved on its western side.

The imprints of five slabs of the eastern foundation and four of the western foundation have survived. These elements were arranged in alternating headers and stretchers. Thus, there is no doubt that this was the type of construction used for both pillars (Figures 11 and 12).

Figure 11. The caementicium blocks that make up the foundation of the arch located next to the road. They were found in the excavations that were carried out in Plaza de la Morería, Sagunto.

Figure 12. Stratigraphy of the Morería site. The numbers refer to the stratigraphic units. 1001–1005: contemporary and modern period; 1047: medieval period; 1075 interior of the temple; 1116: sewer; 1136: temple; 1246: ustrinum; 1266: fourth to eighth century deposit; 1289–1290: arch foundations; 1300: early Islamic period; 1446: street portico.

Figure 13. General plan of the Morería, excavations: (1/1') arch; (2, 3 and 4) domus of the third century AD.

A reconstruction of the arch, based on the foundations found in the excavations and on information from several well-known arches (Pola, Berá, etc.) can be proposed. The structure of the entablature can also be compared with that of arches from the early imperial period, specifically the first half of the first century ad. The elements may include a cymatium moulding, an unadorned architrave, a corbel cornice, and a pediment.

Conclusion

The honorary arch of Sagunto is a clear example of the public or private construction of local monuments in Roman cities. These projects followed, modestly, the pattern set by the great official monuments built in the provincial capitals. The city under scrutiny here, Saguntum, was arranged in terraces on a hillside, following the urban model that architects implemented in the capital of the province, Tarraco. This happened at a time in which the relationship between the provinces and Rome reached a new political dimension. The incorporation of Roman architectural and epigraphic elements dates the arch of Sagunto to the Flavian period and the reign of Trajan, which can be regarded as the last period of its construction.

The latest archaeological work carried out in the areas outside the walls of the municipality of Sagunto has enabled new monumental remains to be documented in detail, thus providing more precise information on the urban planning of Saguntum during the High Roman Empire. To the east, in Plaza de la Morería, archaeologists have discovered an excellent stretch of road and the foundations of a temple; the remains of the largest public square identified to date in the town were found on the Quevedo site, next to the Convento de la Trinidad. These remains were discovered in the 1980s, although the most recent excavations were carried out in 2014. The Roman circus extended in an East-West direction along the southern bank of the river Palancia. Its remains have been known since the eighteenth century thanks to several scholarly reviews. The first to conduct archaeological excavations was Chabret in 1888, and the last interventions were carried out in 2009, which combined excavation work, consolidation, improvement and enhancement of the circus gateway to be included in a landscaped square.

In this new stage, the civitas of Sagunto included the lands lying adjacent to the river Palancia. This extension of the town perimeter has also been related to the implementation of new access roads. The process of monumentalization, as we have mentioned in previous articles, could coincide with that of other Hispanic cities, as a result of the peace process following the Sertorian and civil wars. Indeed, in the time of Augustus, Sagunto received the municipal statute; construction in the town was then extended from the ford onwards and the layout followed several roads that crossed the land at the foot of the castle. We know that one of them linked up with the bridge that stands in front of the circus. These findings, together with the presence of several public infrastructures, such as sewers and fountains, define a better urban planning of the lower part of the town during the first and second centuries ad.

The construction of these buildings was financed by the municipal authorities and by significant amounts of money contributed by individuals. There is a great deal of literary evidence describing the participation of rich citizens in imperial times. A magnificent example of an immense fortune in the town in the second half of the firstcentury is the 4 million sesterces that Voconius Romanus, a citizen of Sagunto, received from his mother (Pliny, Epist. 10.4.2). Moreover, we know that arches were erected in the monumental centres of the towns and there is documentary evidence of an arch in the Morería over the roadway near the temple.

The Roman arch in Sagunto represents the interest of the local elite classes to build monuments in Roman towns and cities. These projects undoubtedly followed, in a modest way, the pattern set by the great official monuments built in the provincial capitals. Accordingly, the city was arranged in terraces on a hillside, following the urban model that architects implemented in the capital of the province, Tarraco. This happened at a time in which the relationship between the provinces and Rome reached a new political dimension. With the adoption of Roman architectural and epigraphic elements, the Sagunto arch points to the Flavian period and the reign of Trajan as the latest possible date of construction.

To sum up, the Sagunto arch is a simple arch, erected in a pre-eminent position at the entrance of the Morería road. This road, oriented North-South towards the hill of the castle, would have been visible from the N-S cardo. Its construction includes a slight kink in the road near the temple.

The destruction and dismantling of the monument must have taken place in the middle of the fourth century or in the fifth century ad. A deposit of silt over the foundations of the arch, made of bluish-grey limestone fragments, has been dated to that period. These fragments may have been deposited there when the ashlars that made up the monument were extracted and reshaped.

At that point, the public buildings that contributed to the popularity of the city during the High Empire were abandoned. The previous urban configuration was no longer followed, and was replaced by new models of urban architecture that transformed a large domus located in the lower part of the city. At the same time, the new constructions transformed the city's suburbs. All these changes resulted in Saguntum presenting a different aspect. The infrastructural elements of this part of the city soon became cluttered and clogged. Clear examples include a fourth-century road and sewer filled with sedimentary deposits. However, the temple's floor plan remained intact until the twenty-first century, when its southern corner was dismantled. Within this framework of urban transformation, a progressive occupation of the public thoroughfare, changes in the road surface, and a rise in the street's level took place. Clay and rubble pavements became widespread. The extension zone occupied by housing led to the closure of the road portico and the subsequent use of the pavement in the area of the arch.