Of all the major business firms that emerged in colonial India, Tata arguably came closest to embodying the ideal type of the modern industrial corporation. Pioneers in textiles, steel, hydroelectric power, chemicals, and automobiles, the Tatas are known for decisively shedding their past as traders in cotton and opium and exchanging it for the mantle of economic nationalism. In 1949, N. S. B. Gras wrote in the pages of the Bulletin of the Business Historical Society (predecessor of this journal) that founder Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata “was once a merchant, like his father, but unlike his father he became a great industrialist.” In the course of this transformation, Tata “spread out to establish many companies of high quality and strategic importance—the foundation of modern Industrial India.” At a time when the field of business history was in its infancy, Gras urged future scholars to cast a wide net beyond the United States, for example, by comparing Tata with the great Japanese zaibatsu. “Perhaps,” he concluded, “we have in America no exact parallels to these oriental enterprisers.”Footnote 1 In a similar vein, Dwijendra Tripathi's authoritative history of Indian business ascribes Jamsetji Tata's “towering, almost unique, position” among his contemporaries to a willingness to take on “gigantic industrial projects,” thereby breaking free of the prevailing “trade-industry nexus.”Footnote 2

The path taken by Tata from trade to industry reflects the characteristic features of a vibrant “alternative business history of emerging markets” (Asia, Africa, and Latin America): the importance of individual entrepreneurship for overcoming market constraints, a flexible organizational structure not conforming to the classic “M-form,” sustained diversification, and the persistence of family and kinship ties.Footnote 3 Yet, in certain crucial ways, Tata stands out as a singular case worthy of further comparative study. The firm tended to separate ownership and control, employed professional managers and talented nonrelatives in leadership positions, relied on more transparent methods of financing than its competitors, and maintained social and economic ties beyond the minority Parsi (Zoroastrian) community to which they belonged—a noteworthy cosmopolitan ethos in a business environment segregated by race, caste, and regional identity.Footnote 4 As Tirthankar Roy has argued, “cosmopolitanism and the strength of weak ties in port cities” like Bombay, rather than community networks, enabled innovative and risk-taking entrepreneurial behavior like that of Jamsetji Tata.Footnote 5

Few as they were in number, India's industrialists did emerge from the colonial port city, posing a challenge to long-standing Eurocentric accounts of the origins of modern capitalism. Max Weber's General Economic History (1923) firmly held that “capitalism in the west was born in the industrial cities of the interior, not in the cities which were centers of sea trade.” Neither the Parsis nor the Jews, similar religious minorities exempt from the ritual restrictions of caste and guild systems, could make the leap from profiteering to the rational organization of production.Footnote 6 The Weberian notion of “pariah capital” had informed both Marxian and Cold War modernization theories of Indian capitalism until the mid-1970s, when it came under serious scrutiny.Footnote 7 Rajnarayan Chandavarkar, among others, highlighted the dynamism and variation of entrepreneurial response to common structural constraints in a colonial economy. Far from an “obvious, logical progression,” the decision to enter factory production was “only one possible outcome” of diversification, and an unlikely one at that.Footnote 8 Roy's recent synthetic history posits a smooth “interdependence between trade, finance, and industry” in colonial India, with revenues from agricultural exports funding the purchase of foreign machinery and expertise for the mills. Yet Roy also acknowledges how rare it was for merchants to make the “unconventional” or “off-beat” decision to start a factory.Footnote 9

The dominant emphasis on complementarity between trade and industry in the current literature, while convincingly refuting earlier normative assumptions of a clear-cut transition from mercantile to industrial capitalism, leaves little room for discontinuities or tensions at the level of the firm. Nor does it adequately explain why some firms took very different paths than others. Tripathi's survey acknowledges that the “convincing leap forward into modern industries” during the late nineteenth century did not lead to substantial diversification until the interwar period. Marwari groups were generally “slow to move away from purely commercial lines,” while the millowners of Ahmedabad “felt more secure sticking to a familiar sector” due to their “trading and moneylending background.”Footnote 10 The Tatas appear as an exception or outlier, their trajectory dictated by idiosyncratic entrepreneurial choices. A more precise reconstruction of “what they perceived to be their options and why they made certain choices rather than others at particular moments of time” is needed.Footnote 11

This article provides an archivally grounded understanding of Tata's expansion across multiple spatial scales, from the global to the national, arguing for the continuing importance of trade well after the initial entry into manufacturing in the late 1870s. It focuses on two little-known trading companies, R.D. Tata & Co. in Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Kobe, and Tata Limited in London, which remained legally separate from the parent firm in Bombay but worked closely with it. Tata's diffuse structure conforms to William D. Wray's description of Japanese shipping conglomerates in the same period, whose overseas branches were “a kind of spatial extension of the firm,” or a porous and dynamic “outer boundary.”Footnote 12 Owing to a lack of available records, the activities and financial performance of Tata & Co. and Tata Limited have so far proved difficult to reconstruct. Successful at first, they became “something of a side-show in relation to the firm's manufacturing ventures.”Footnote 13 How and why this happened remains unexplored.

Such “adjunct” trading companies, acting in a semiautonomous capacity from parent firms in India, have not been the subject of a stand-alone analysis.Footnote 14 As Geoffrey Jones has argued, trading companies reduced “search, negotiation, transaction, and information costs,” correcting pervasive “reputational and informational asymmetries” faced by merchants competing on the global stage.Footnote 15 In a South Asian context they have been difficult to define and to distinguish from other types of business organization in long-distance trade. Rajat Ray's influential model of the “bazaar” posits a typical banker or merchant whose “bargaining strength” against European capital lay in deploying local knowledge of inland or coastal trades outward across the Indian Ocean.Footnote 16 Gujaratis in East Africa, Chettiars in Southeast Asia, and other “settled diasporic populations” drove Indian globalization until the growth of limited foreign investment by multinational firms in the post-independence period.Footnote 17 The “adjunct” trading companies of the Tatas expand this typology, indicating another way of being global for Indian business in the early twentieth century.

Tata & Co. and Tata Limited performed several distinct intermediary functions (remitting profits, distributing products, and securing external financing for industrial investment), all the while increasing the parent firm's exposure to volatile global markets. Financial intermediation was by far their most important and contentious function. Chikayoshi Nomura has identified the “scarcity of long-term capital” as the fundamental constraint on industrial and corporate development in colonial India.Footnote 18 Trading booms in commodities such as raw cotton, jute, or pearls, as well as occasional military contracts, could provide windfalls of short-term capital but failed to overcome this constraint in the long run. The managing agency system, which pooled the resources of extended business families, arose partly in response to the weakness of the share market and the formal banking system.Footnote 19 Within diversified and loosely organized groups such as the Indian managing agencies, parent firms often acted as “in-house banks” and were expected to advance substantial loans to cover losses and keep affiliates afloat.Footnote 20 Not all firms were willing or able to do so, nor did families speak with one voice. Only careful firm-level studies can fully elucidate these dynamics.

In the Tata case, intense disagreements broke out within the family over the relationship between the trading and industrial branches and the necessity of diversifying beyond India. A unified strategy of expansion could not take shape as long as advocates of trade in commodities remained enmeshed in the governance of the principal managing agency in India. Family itself became a site of fierce contestation over the future of the business, where personal and financial relations could not be easily disentangled. Just as strong community ties are now recognized as a possible obstacle to entrepreneurship, the role of family remains ambiguous. At the aggregate level, it may reduce uncertainty and enhance trust in “high-risk environments,” or even serve as an essential prerequisite for overcoming developmental lags.Footnote 21 But if capital in India “chased individual family names” above all else, family became an outsized source of risk.Footnote 22 A tarnished or devalued name could not be written off like any other bad asset.

Through speculation and commodity price shocks, Tata repeatedly suffered heavy losses that have not yet found their way from the account books into the historical record. The insolvent position of the overseas trading companies only came to light in the aftermath of a series of financial crises, providing the only fragmentary evidence of their workings that has survived in the corporate archive. The global deflationary shock of 1920 and 1921 and the onset of the Great Depression a decade later ultimately restricted the scope of the firm's activities beyond India and highlighted the importance of cultivating a reputation for fiscal probity—a key factor in Tata's long-term resilience.Footnote 23 The pursuit of respectability may also be seen in the marginalization of Marwari partners and upcountry selling agents, stereotyped as unreliable and customarily prone to speculation. If Tata became a dominant player in a protected national economy by the time of independence in 1947, this was due to the contingent failure of an earlier strategy of expansion rather than a foregone conclusion.

Houses Built on Sand: The Making of a Business Empire

The origins of the Tata family fortune are shrouded in myth and rumor, particularly in relation to the opium trade. Founder Jamsetji Tata, born in 1839, belonged to a Parsi priestly family from the small town of Navsari in Gujarat. His father, Nusserwanji, first accumulated capital as a contractor during the British occupation of the Persian Gulf port of Bushire in early 1857.Footnote 24 Young Jamsetji was brought into the father's firm soon after. In 1859 Nusserwanji opened a branch in Hong Kong, importing Indian cotton and opium and exporting Chinese tea, silk, and gold. Jamsetji helped establish yet another branch in Shanghai.Footnote 25

Parsi traders like the Tatas owed their success in the China trade to their inheritance of the “maritime tradition” of the Indian Ocean, which saw them “connecting Aden with Canton in their own ships.”Footnote 26 The famed Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy led the way in forming lucrative partnerships with Jardine Matheson & Co. and other British firms, dealing in opium and cotton. The relationship became more unequal over time, as Indian merchants used bills of exchange issued in London to remit their profits.Footnote 27 Parsis had at their disposal various strategies to combat the problem of trust and the volatility of markets. Family networks helped to restore credit and ensure the survival of firms in times of crisis, such as the sudden fall in cotton prices after the end of the American Civil War in 1865.Footnote 28 It is even plausible to speak of a “loosely organized Parsi company at work” in mid-nineteenth-century Bombay.Footnote 29 Sending “their own agents and relatives” abroad as trusted intermediaries may have helped overcome the problem of remittances that had plagued Jeejeebhoy's generation.Footnote 30

At the same time, because Parsi merchants could never secure full control over the movement of commodities “from field to factory or port,” they depended on Marwaris and other intermediaries to connect them with upcountry markets.Footnote 31 The only non-Parsi associated with the Tatas’ early trading companies was a Marwari, Cheniram Jesraj, who served as their opium broker and would later hold the selling agency for the four Tata textile mills.Footnote 32 Marwaris came to be regarded with suspicion by the colonial state and commercial rivals alike due to their secretive family-based business culture. Marwari speculation, encompassing a complex array of futures and forward contracts, was seen as distorting “true” market practices.Footnote 33 But at this early stage, even companies organized on the joint-stock principle and trading on the formal Bombay share market took “recourse to the bazaar and to social networks” when necessary.Footnote 34

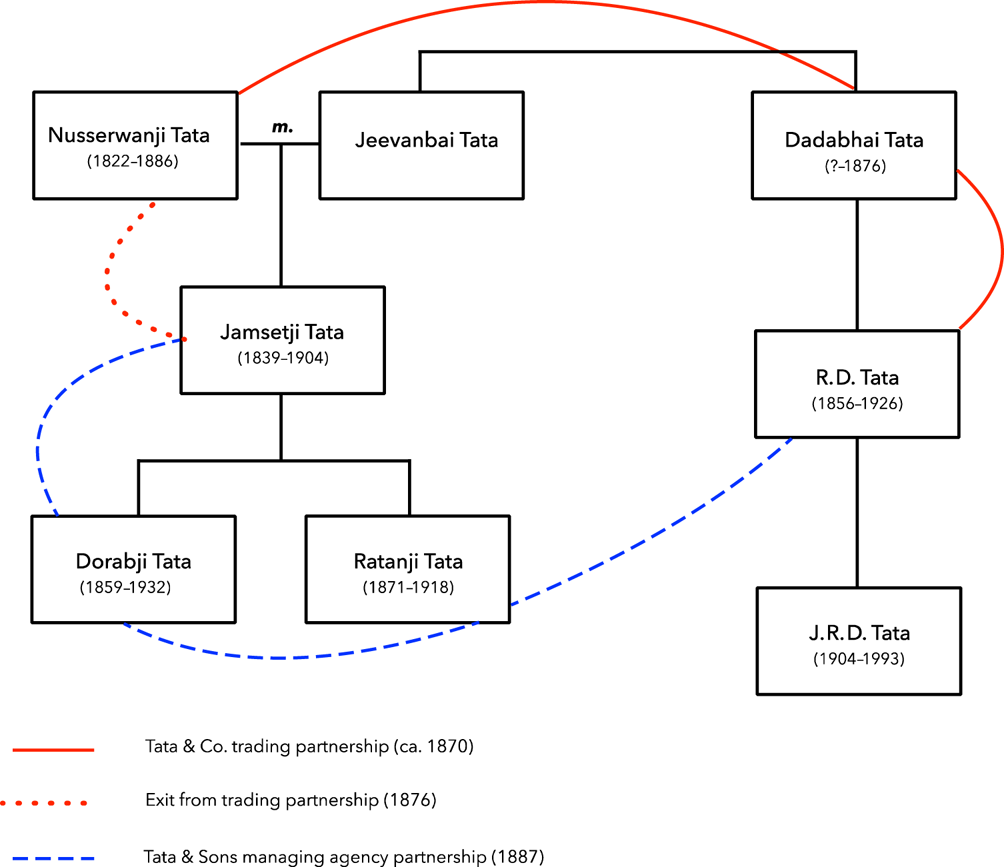

After the cotton crash of 1865, which nearly ruined the Tatas, another fortuitous military commission came to their rescue. Nusserwanji rebuilt his fortune through a contract to supply the expeditionary force deployed from British India against the ruler of Abyssinia in 1868. He then traveled to Japan and China, reopening a branch of his old firm in Hong Kong with the assistance of his brother-in-law Dadabhai Tata, who had remained active in the opium trade. This was the origin of Tata & Co. Upon Dadabhai's death in 1876, Nusserwanji and Jamsetji withdrew from the firm, but the father rejoined in 1880. Jamsetji “regarded the branch to be too remote for efficient supervision,” turning his attention to cotton manufacturing in India. It was only in 1883, when Dadabhai's son Ratanji Dadabhoy (R. D.) took over, that the business of Tata & Co. was put on a sound footing.Footnote 35 R. D. continued to trade in opium, petitioning against regulations proposed by the Hong Kong Legislative Council in 1887 along with six other Parsi and Jewish merchants.Footnote 36 That same year, the two sides of the family were brought closer together upon the formation of Tata & Sons as a managing agency controlling the Tata textile mills in India, with R. D.'s and Jamsetji's sons Dorabji and Ratanji as partners (see Figure 1). Tata & Sons, while legally distinct from Tata & Co., was deeply connected to its trading counterpart by more than blood. The mills required new markets for the export of cotton, which meant bypassing the effective monopolies of British trading and shipping companies.

Figure 1. Simplified Tata family tree, showing formation of trading and agency partnerships between ca. 1870 and 1887. (Source: F. R. Harris, Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata: A Chronicle of His Life, 2nd ed. (London, 1958), 36–40 and appendix C, “Genealogy of the Tata Family.”)

In the early 1890s, Indian merchants leveraged their position as intermediaries between the East and West Asian cotton trades to gain access to the Japanese market, threatening British dominance of the seas.Footnote 37 Tata & Co. was the first Indian trading company to secure a foothold in the port city of Kobe, in 1891, signing a contract with the Naigai Men Company for the import of raw cotton.Footnote 38 In the absence of a direct shipping route to Japan, Indian merchants were forced to contend with a European cartel led by the British Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O), which controlled the route via Hong Kong, charged high fixed prices, and set a maximum limit of bales per month that could be transported. Seizing the opportunity to reduce the transaction costs of his Bombay mills and strike a blow for India's commercial and strategic autonomy, Jamsetji Tata proposed a new shipping line as a joint venture between his firm and the Nippon Yusen Kaisha (NYK) in 1893. R. D. Tata's office in Kobe assisted in the negotiations for lower rates and a minimum quantity of freight. “If we secure anything like a hundred thousand bales of cotton,” Jamsetji wrote, “and, say, about two thousand chests of opium, it will be greatly to the advantage of our trade, to excite our opponents to lower their rates as low as possible.”Footnote 39 The inclusion of opium is significant because the P&O had reserved for itself the exclusive right to ship the drug.

The new Tata Line was short lived, undercut by a ruthless price war with the P&O (referred to by Jamsetji as the “war of freights”) and by the hostility of the British government. Jamsetji's fellow Bombay millowners “deserted” him in the hour of need, following the appearance of anonymous accusations in the press.Footnote 40 One of the gravest charges, strongly refuted by Tata & Sons in the Indian Textile Journal, was that “this line had been started from interested motives,” given Tata & Co.'s participation in the cotton export trade. The relationship had to be thoroughly disavowed:

Capital has been made of the resemblance between the titles of the two firms coupled with the fact that one partner of our firm [R. D.] is also partner in Messrs. Tata & Co. Beyond this, there is or has been no connection whatever between these two firms, whose line of business is entirely distinct. . . . It is not contended that we are putting Messrs. Tata & Co. on especially favorable terms as compared with other shippers.Footnote 41

Given the close collaboration between the two branches in securing the agreement with NYK, this line of defense proved ineffective. Tata & Co.'s presence in China and Japan afforded an indispensable foothold in the race for new markets, even as it threatened the security and credibility of Tata & Sons in Bombay. This tension would recur as the family pursued an ambitious program of industrial expansion over the following decades.

The Promise and Peril of Expansion

At the time of his death in 1904, Jamsetji Tata was close to realizing a long-held dream of building India's first iron and steel plant. Where successive attempts by the British colonial state and expatriate firms had made little progress, Tata saw an opening for Indian business to take the lead. Because capital was scarce in India for an enterprise of such unprecedented scale and complexity, Tata and his sons Dorabji and Ratanji initially turned to the City of London, over the strenuous objections of Indian nationalists. They approached both British and American financiers and wealthy Indians but did not offer the latter favorable terms because “if that were done, Indian capital would find profit in subscribing with a view to immediate selling out in England.”Footnote 42

London bankers showed no interest, a stance commonly attributed to racial prejudice or commercial narrow-mindedness.Footnote 43 But an even greater obstacle was the City's reluctance to back concerns in India and preference for China, Latin America, and other areas of Britain's informal empire.Footnote 44 The conflict that mattered was not along racial lines but between metropolitan capital and the colonial state. R. D. Tata, who assisted with the negotiations, was informed by contacts in London that “Rothschild [and others] will have nothing to do with a country whose Government will not allow them to make money.”Footnote 45 He learned that “Indian concerns, however promising, have gone out of fashion in the London market,” and “Chinese concerns are just now in the fashion.” Because British concessionary operations in China often encountered “obstruction from Mandarins whom the Japanese alone know how to manage,” R. D. was advised to use his influence in Japan to ensure that “a Chinese concern supported by Tata” and run by Japanese managers “would be hospitably received” in London. But the idea went nowhere, not least because prospective British partners feared competition with Tata & Co. in East Asia.Footnote 46

When the Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO) was publicly floated in 1907, all eight thousand original shareholders were Indians. Most accounts of the origin of TISCO center on the eagerness of these investors to come forward out of purely patriotic sentiment, or (more cynically) on the ability of the Tatas to exploit nationalist sentiment for their own ends.Footnote 47 The majority of shares were held by a small “exclusive group” of princely rulers and Bombay millowners seeking alternative investment opportunities during a slump in the Chinese cotton market. None had experience in long-term financing for a major industrial enterprise, which helps explain why the Tatas turned to London first.Footnote 48 The importance of Tata & Co.'s connections with China and Japan in the failure of those negotiations has been overlooked.

The viability of the new company likewise did not depend only on guaranteed rail orders for steel from the colonial state but also on the export of pig iron to East and Southeast Asia.Footnote 49 Due to low input costs for coal and iron ore, TISCO was much more competitive in pig iron, rapidly becoming the world's cheapest producer.Footnote 50 The shipping arm of the Mitsui zaibatsu, the Mitsui Bussan Kaisha, was granted a monopoly on the company's foreign sales of pig iron up to 1913, with Tata & Co. once again facilitating the deal.Footnote 51 Three years later, TISCO management decided that Mitsui was making disproportionately large profits and proposed appointing a salesman of their own “attached to the Tata firms in the East [Tata & Co.], and the Tata firms acting as Agents with the help of the salesman should push on the sales of the company's pig [iron] in China, Japan and other countries.”Footnote 52 The establishment of TISCO thus entailed an expansion of overseas trading activities, in both the financing and operational phases. It also anticipated the later drive to centralize and vertically integrate selling agencies.

At the same time, the relationship between the trading and industrial branches grew strained under the weight of family conflicts between R. D. Tata and Jamsetji's sons. R. D. argued that Tata & Co. should obtain TISCO's selling agency in Calcutta, while Dorabji viewed this linkage as a source of unnecessary risk and believed the firm was already overextended.Footnote 53 Their trusted adviser B. J. Padshah, a brilliant polymath who dabbled in mathematics and theosophy and had served as Jamsetji's right-hand man, mediated between the two sides.Footnote 54 He duly informed R. D. that “the general policy is one of curtailment in all departments . . . wherever possible & that on the chief ground that the brothers wish to feel that they are not burdened with too much responsibility.” Padshah then proposed a radical solution to break the impasse:

Tata & Sons live on Mill commissions; there is not much room for new partners there; I, therefore, revert to an idea which I have encountered in several minds since the death of Jamshedji—the amalgamation of Tata & Co. & Tata & Sons, under the style of Tata, Sons & Co. (The word Sons will largely add to the goodwill of the firm. The Marwaree seems an incongruous element in such a firm).Footnote 55

It is telling that Tata & Co.'s Marwari agents, who had played such a vital role in the China trade, would be excluded on the grounds of respectability. To place the firm on a sound footing, the Tata name had to remain unblemished.

Padshah's proposal for amalgamation rested on the three partners holding equal shares. Even though Dorabji and Ratanji would “bring into the firm bigger credit than you, and bring in the large profits of mill agencies,” he assured R. D., “you will be bringing in the great agency business of Tata & Co. including the new schemes” then underway.Footnote 56 R. D. planned a wide range of unrelated investments in new mills, real estate, and mines in India and Singapore. Padshah sought to dampen his enthusiasm for continual diversification: “YOU are extending everywhere and starting but on new lines everywhere, and your assets have no liquidity.”Footnote 57 For Padshah, the Tatas’ future would only be secured by treading carefully between unbridled expansion, championed by R. D., and Dorabji's conservative instincts. This required the constant management of family conflicts by an insider who was not a member of the family.

While the personalities involved may seem to fit crude stereotypes (R. D. the exuberant speculative trader, Dorabji the austere pragmatic industrialist), the problem was one of corporate governance. Making R. D. a partner in the original managing agency agreement in 1883 while he retained control of a semiautonomous trading company made formulating a coherent strategy of expansion at the level of the firm extremely difficult.

The Tata model stands out by contrast with Godrej, a contemporary Parsi family group manufacturing locks and safes. Founded by two brothers, Ardeshir and Pirojsha, the group entered new lines, including vegetable oils and soaps, in the 1920s and eventually became a diversified industrial conglomerate. The third brother, Manchersha, focused exclusively on trade, working with R. D. Tata in Kobe and Paris before starting his own separate company dealing in pearls and precious stones.Footnote 58 Manchersha steadfastly refused to become a partner in the brothers’ firm, only offering small loans when short-term capital was needed. In return he demanded that “regular interest is given to me till I live, so that there won't arise any occasion for me to beg in my old age.”Footnote 59 Traders could be conservative as well as risk-taking, and their degree of involvement in industrial ventures varied considerably.

As a result of the exchanges between R. D., Dorabji, and Padshah, the parent firm in Bombay was renamed Tata Sons and a new subsidiary was established in 1907. Headquartered in London, Tata Limited was simultaneously an independent trading company dealing in jute and pearls, the main selling agency for the Tata mills’ cotton in Europe, and a procurement channel for machinery, technical expertise, and market information for TISCO.Footnote 60 It also performed the role of London banker for the textile mills, remitting profits on cotton shipments to the Levant, Egypt, and Europe. Until then, these profits had been routed through third parties such as the Ottoman Bank at Istanbul, the Imperial Ottoman Bank at Smyrna, the Banque d'Orient, and the Crédit Lyonnais.Footnote 61 The new company thus built on existing contacts without introducing any significant organizational innovations or safeguards. Operating on a similar scale to Tata & Co. in China and Japan, Tata Limited was equally vulnerable to speculation and rogue activity by managers on the spot.

Boom and Bust: The 1920–1921 Crisis

The outbreak of World War I provided Indian business with new opportunities for expansion. Tata in particular stood to benefit from the curtailment of imports and the encouragement of domestic industries for defense purposes. TISCO's entire steel output was placed at the disposal of the government. Rails shipped from India to Egypt and Mesopotamia proved vital to British military success, as the Viceroy Lord Chelmsford recognized after the war.Footnote 62 In London, the Ministry of Munitions approached Tata Limited to inquire about the manufacture of antigas respirators from coconut shell charcoal at the newly opened Tata Oil Mills.Footnote 63 For Padshah, the risks of rapid diversification could now be mitigated by adopting a core developmental mission:

If the Tata firm become[s] an organ of public service widely recognized, if the Tata firm include[s] more & other than Tatas, if the Tata interests include so many ordinarily conflicting businesses, that a parallelism between Tata interests & the interests of the general public cannot be avoided, if Tata finance be the finance of a large wealthy & able group (preferably international), what is there to fear?Footnote 64

Shedding his earlier caution, Padshah proposed entering a range of new sectors, including wool and silk mills, hydroelectric power generation for coalfields, aluminum and cement manufacture, irrigation, land reclamation, railways, tramways, and aerial transport.Footnote 65

The success of the Tatas’ postwar expansion depended on securing stable long-term financing. Padshah promoted the creation of the Tata Industrial Bank for this purpose, inspired by similar institutions in Germany and Japan. The bank was meant to bridge the gap between the financial connections nurtured by Tata Limited in London and the diversifying portfolio of Tata Sons in Bombay. For example, a planned joint investment between the bank and Tata Limited in a dyes company would not only be “very remunerative in itself” but would also help TISCO “with inside knowledge about dyes manufacture at Sakchi [Jamshedpur], a project which the Directors of the Steel Company have been anxious to bring into existence.”Footnote 66 Unlike R. D.'s entrenched preference for commodity trading, Padshah promoted investments in essential infrastructure: “Urbanization of rural localities will bring urban civilization into villages—electric power and light and transport, roads, motor lorries, schools, hospitals, well-built cottages, stores and thus breathe new life into villages.”Footnote 67

The bank did not fulfill these lofty ambitions. Shareholders grew concerned that its investments were predominantly Tata-related instead of contributing widely to the growth of new industries and that it did not employ enough Indian branch managers.Footnote 68 The incursion of formal banking into the domains of rural moneylenders and shroffs (traditional bankers) provoked widespread resentment.Footnote 69 Rival financiers mobilized against the new venture, seizing on the wave of public criticism to engineer the amalgamation of the Tata Industrial Bank with the Central Bank of India in 1924.Footnote 70 Industrial expansion continued to be financed mainly with private funds, rather than through banks or the share market, well into the following decade.Footnote 71

The swift downfall of the Tata Industrial Bank did not take place in a vacuum. It was one act of a larger drama, as the postwar deflationary slump brought the entire firm to the brink of ruin.Footnote 72 Tata Limited was especially hard hit, facing a chronic shortage of liquidity as commodity prices came crashing down.Footnote 73 In April 1921, the company drew a three-month bill of exchange from the London investment bankers Kleinwort & Sons, backed by £82,415 in future jute sales to twenty-one German spinning companies. Significantly, Tata Sons in Bombay provided the guarantee, agreeing “to hold ourselves liable for all the consequences of their [Tata Limited's] default or failure to meet such engagements.”Footnote 74 By November the company's position had worsened. Another request for a three-month bill of £26,000 was backed by 7,125 unsold bales of jute held in two warehouses in Barcelona and Bilbao. Tata Limited assured the bankers that “we hope to dispose of it within the next three months or at all events we trust that there will be very little left at the expiration of that period.”Footnote 75 The global jute market completely collapsed at the end of the year, forcing Tata Limited to call up its remaining capital and transfer key assets to Bombay.Footnote 76

Shortly thereafter, “serious irregularities” in the account books came to light. The managing director, H. F. Treble, had kept Tata Limited's cotton dealings “concealed from Bombay and camouflaged in the Balance-Sheets . . . because his own personal transactions had been irregularly financed through the firm.” An investigation revealed that auditors had failed to spot any discrepancies because they had only checked “the cash payments and receipts in the Commission Account,” which did not cover trade. Treble had then deliberately destroyed incriminating records to cover his tracks.Footnote 77 The company's diffuse structure prevented effective oversight and monitoring. Tata Limited consisted of two separate departments, one dealing with procurement and services for TISCO and the mills and the other with trade in jute and other “produce” (rice, yarn, and oils). The jute department was “practically run as a separate one, sending their own cables, attending to letters etc. without the aid of the general office.”Footnote 78 This type of structure could not accommodate the dual functions of independent trading and servicing affiliate companies, leading to principal-agent problems.

Tata Limited was also forced to operate under the untenable contradiction of being legally distinct from Tata Sons while collecting agency commissions on its behalf. The decision to register a separate company in London in the first place was taken because “the partners did not desire to run any risk of rendering themselves liable for assessment on any part of their respective Bombay profits” by the British income tax authorities. Tata Limited was therefore advised “to conduct the business of the company as not to present any appearance of an agency” and to ensure that its correspondence with Bombay reflected this fiction.Footnote 79 All of Tata Limited's paid-up share capital was provided by Tata Sons. The directors in Bombay refused to distribute new shares after the crisis, deciding instead that “the whole of the capital, in whichever form, should remain in the hands of Tata Sons Ltd.” By the end of the 1930s the company's total deficit stood at £120,368, including £77,538 owed by D. P. May and £8,009 by the Anglo-India Jute Company (two former trading partners).Footnote 80 After a brief recovery, it suffered consistent annual losses (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Tata Limited annual net profits and losses (in £) after financial reconstruction by Tata Sons. (Source: “Proposed reconstruction of Tata Ltd., London [Shares],” n.d., box 502-03, T53-DES-T71-1, file no. 374, Tata Central Archives, Pune, India.)

The challenges faced by Tata Limited were far from unique. Jones has noted that “one of the greatest threats to a trading company was from unauthorized speculative dealing by their staff,” especially in distant branches under minimal supervision. Well-known British firms such as Balfour Williamson and Jardine Matheson experienced similar problems in their New York offices, with “ritual denunciations of speculation” permeating their correspondence.Footnote 81 The real significance of Treble's fraud was that it confirmed Dorabji's suspicions about trading in general:

My feeling always was against undertaking any business that had to be carried on at a great distance from the head-office as I always felt that we could not have the requisite control over it. That is why I always felt shy of the China & Japan business especially after the losses incurred by our representatives in those places. . . . I shall be a crore, if not more, rupees to the bad including the losses made by Tata Ltd., London, during the last 3 years. And I believe that the cause is that we are doing much more business than we ought ever to have undertaken, and for which we are dependent on outsiders for management.Footnote 82

Because they played into existing family conflicts and debates over strategy, the failures of the Tata Industrial Bank and Tata Limited signaled a shift in the firm's overall orientation. Whereas the bank called into question the Tatas’ nationalist credentials, Tata Limited severely damaged the family's financial reputation at a moment when TISCO was desperate for long-term capital.Footnote 83

Following “the stoppage of all trading business,” Tata Limited faced dwindling revenues from agency commissions and pervasive information asymmetries as Tata companies experimented with alternative ways of distributing products and capturing markets. The Tata Hydro-Electric Companies refused to pay full commission for transactions in debentures and securities on the London money market. TISCO's newly formed sales department in Calcutta left Tata Limited “entirely at sea as to their requirements, method or policy” regarding the sale of pig iron in Europe.Footnote 84 The crisis of the early 1920s marked the first step toward a dual strategy of vertical integration and domestic expansion.

The Emerald Necklace: Winding Up Tata & Co.

The chain of events leading to the Tatas’ complete withdrawal from overseas trade began with R. D. Tata's death in 1926. The ensuing investigation of Tata & Co.'s balance sheets revealed a substantial amount of debt. R. D.'s “insolvent” estate could not cover the Rs 2.5 lakh (250,000) gap between assets and liabilities. The company's largest creditors included the Yokohama Specie Bank (YSB) and Taiwan Bank in Japan, the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC), and the National City Bank of New York.Footnote 85 These powerful financial institutions “had been mislead [sic] relying on [the] Tata name, and if Tata Sons took up the attitude that they had nothing to do with R.D. Tata and Co., they would be justified in law but would leave a bad impression on the minds of the Bankers in different parts of the world.” The “similarity of name” acted as a virtual guarantee for investors. As one Marwari merchant from Calcutta put it, “I always thought that so long as Tata Sons Ltd., was there, it would be quite safe to trade with R.D. Tata & Co. Ltd.” This meant that Tata Sons had no choice but to assume the debts and “do their best to avoid a forced liquidation.” Otherwise, their industrial interests would be adversely affected:

In Japan and the United States and even in Shanghai, people do not know the difference between R.D. Tata & Co. and Tata Sons Ltd. Already there are reactions on us. Tata Iron and Steel loan which we wanted to negotiate through the National City Bank of New York, finds difficulty because of R.D. Tata & Co. mess up. Our Tata Iron & Steel Co. pig iron negotiations in Japan were also questioned because of what had happened to R.D. Tata & Company.Footnote 86

Keen to safeguard their most lucrative market for pig iron exports, the Tatas needed to maintain good relations with Japan from a position of relative weakness.Footnote 87 The Japanese banks drove a hard bargain and forced Tata Sons to guarantee Tata & Co.'s losses up to 85 percent.Footnote 88

After the liquidation agreement was signed in 1930, Tata & Co. ceased all trading and went out of existence after settling its debts. It is important to emphasize the contingency of this outcome. When British trading companies failed in the same period, they were often bailed out by London banks with deeper pockets than the Tatas in Bombay. For example, Lloyds Bank undertook the reconstruction of the “hopelessly insolvent” Grahams, gradually liquidating bad assets and providing “substantial unsecured credit.”Footnote 89 With fewer resources and no comparable access to the London market, especially after the failure of Tata Limited, the Tatas could not follow the same playbook. Nor could they sustain commercial linkages between India and Japan in the changing political and economic context of the Great Depression. Chairman Nowroji Saklatvala was furious that “the Japanese Banks who owe practically their whole position in India to the Tatas and in a great measure to poor R.D. have shown no gratitude for all that has been done for them.”Footnote 90

Table 1 Tata & Co. Liquidation Accounts (as of August 11, 1932)

Source: R. D. Tata & Co., Ltd. (Liquidation), n.d., box no. 502-23, T53-DES-RDT-1, file no. 240, Tata Central Archives, Pune, India.

a Including Yokohama Special Bank (800,000 yen), Taiwan Bank (480,000 yen), Hong Kong Shanghai Bank, and National City Bank of New York.

b From other shareholders including Tarachand (amount not known), Narandas (150,000), J. M. Sethna (10,000), R. H. Kanga (3,200), N. D. Tata (16,000), M. J. Bilimoria (1,200), Jaganaath (6,400), H. V. Dalai [sic] (1,200), B. A. Bilimoria (5,600), Brijmohan & Raradutt [sic] (9,000), R. D. Tata (12,000), Somnath Rupjidas (20,000), and Shaik Abdul Latiff [sic] (11,000). Numbers represent closest estimate based on surviving documentation.

Apart from the repercussions of Tata & Co.'s collapse on financing for the steel company through formal banking channels, the “position of our Marwaris” was left “considerably shaken.”Footnote 91 Marwari names abounded on the list of the company's shareholders and debtors, including Cheniram Jesraj, the Tatas’ stalwart collaborators since the days of the opium trade. Their debts were settled by recourse to informal assets held by families, such as an emerald necklace worth Rs 50,000/- given by “Mr. Sitaram's grand-mother” to be used as collateral in case a “dispute between C.J., and Messrs. R.D. Tata Co. Ltd” should arise.Footnote 92 For many years, Tata directors in Bombay had expressed unease at their companies’ dependence on Marwaris and used the crisis as an opportunity to enact a clean break. The Empress Mills at Nagpur sought to dispense with their Marwari selling agent, Jamnadhar Potdar & Co., due to the accumulation of “doubtful debts” on the company's balance sheets. They were to be replaced with a “special representative” deputized from Bombay.Footnote 93 Meanwhile, leading Marwari groups such as the Birlas took the entrepreneurial leap from commodity trading to industry by purchasing controlling shares in British jute and coal companies.Footnote 94

The process of marginalizing local merchants and intermediaries within Tata companies has so far been understood as driven by internal organizational innovations, most notably TISCO's sales department. In the 1930s, the steel company established its own network of depots and stockyards and enacted prohibitions on resales and forward contracts, which increased its bargaining power over its erstwhile dealers. Nomura persuasively argues that the closer connection “between urban-based merchant-capitalist financiers and inland markets” produced the conditions of possibility for collective action by Indian business in support of a developmental and protectionist nation-state.Footnote 95 The Tatas’ turn to domestic markets cannot be explained strictly through the changing balance of power between big industrialists and smaller merchants within India. It also resulted from the failure of an earlier strategy of global expansion, based on active partnership and cooperation between semiautonomous trading and industrial branches.

Conclusion

With their records lost and their contributions written out of officially sanctioned histories, Tata & Co. and Tata Limited have been largely forgotten. In the mid-1950s, the firm began to assemble its own archive under the auspices of the Department of Economics and Statistics, culminating in a comprehensive official history entitled The House of Tata. When the manuscript was circulated to the top brass for comments, Tata director A. D. Shroff felt it necessary to point out that “for a long time, side by side with manufacturing activity, Tatas also carried on trade.” Since the firm had tentatively resumed “investing in concerns which are interested in trade,” Shroff insisted, “adequate reference should be made” to the company's trading past.Footnote 96 Few subsequent historical accounts have taken up the task. The role of “adjunct” trading companies in the development of Indian capitalism has been obscured.

Maintaining a closely knit yet widely dispersed network of agents and intermediaries (many but not all of them family members) enabled the Tatas to participate in global markets beyond the constraints imposed by imperial power and commercial rivalries. This network was called upon at critical moments, such as in the financing of TISCO and the flotation of the Tata Industrial Bank, typically seen as exclusively industrializing ventures. The trading companies did become a source of unacceptable risk to the reputation and financial stability of the parent firm until they were marginalized or liquidated in the aftermath of global financial crises, first in 1920 and 1921 and again a decade later during the Depression.

While family disputes and anxieties about trust and reputation were common among businesses engaged in long-distance trade, they had specific implications for the scale and scope of Indian capitalism in the late colonial period, paving the way for a sustained drive to capture internal markets just as a protected national economy was taking shape. The contingency of this shift may be illustrated by comparative reference to the Japanese experience. Many sogo shosha (diversified trading conglomerates) also went bankrupt in the 1920s. Others, like Mitsui Bussan (the Tatas’ erstwhile partner in the pig iron trade), demonstrated remarkable resilience, diversifying geographically and cultivating new sales networks. After World War II, trading companies embedded in the large keiretsu groups contributed significantly to the reconstruction of the Japanese economy. Unlike in India, where the state was committed to protectionist industrialization, “trade and financial intermediation” were “fully supported by the [Japanese] government.”Footnote 97

Based on the evidence presented here, it is plausible to imagine an alternative path for the Tata trading companies: one in which they were saved from bankruptcy and more closely integrated into the structure and operations of the parent firm despite the adverse winds of state policy. This might have allowed the Tatas to become more competitive in overseas direct investment (ODI) from the 1950s to the 1980s, when their chief rivals, the Birlas, took the lead in promoting joint ventures in Africa and Southeast Asia.Footnote 98 Tata's reemergence on the world stage in the mid-2000s, through a series of high-profile acquisitions (Corus Steel and Jaguar Land Rover in Europe) and the steady expansion of Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) in North America and China, calls for deeper and more comprehensive explanations.Footnote 99 This article suggests that business historians of India and other emerging markets might fruitfully examine firm-level case studies in depth to determine breaks and continuities in the latest phase of globalization, itself entering another extended moment of crisis.