Childhood maltreatment is a potent and common form of early trauma (Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2005; Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Alink, & van IJzendoorn Reference Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Alink and van IJzendoorn2015). Exposure to childhood maltreatment has been shown to compromise healthy development across critical domains (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti2016), with detrimental effects persisting into adulthood (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos2012). Adding to this concerning picture, research suggests that childhood maltreatment not only produces negative outcomes for individuals during their own lifetime but also has consequences extending to the next generation (Roberts, O'Connor, Dunn, & Golding, Reference Roberts, O'Connor, Dunn and Golding2004). Studies have long observed that parents who have experienced childhood maltreatment are more likely to have children likewise exposed to maltreatment (Egeland, Jacobvitz, & Sroufe, Reference Egeland, Jacobvitz and Sroufe1988; Pears & Capaldi, Reference Pears and Capaldi2001), a phenomenon referred to as intergenerational transmission of maltreatment (Thornberry, Knight, & Lovegrove, Reference Thornberry, Knight and Lovegrove2012).

Although a wide range of transmission rates has been documented (Oliver, Reference Oliver1993), literature suggests that roughly one third of individuals maltreated as children go on to perpetuate maltreatment in the next generation, an estimate about six times higher than for the general population (Kaufman & Zigler, Reference Kaufman and Zigler1987). Parents maltreated as children have also been found to demonstrate heightened maltreatment potential (DiLillo, Tremblay, & Peterson, Reference DiLillo, Tremblay and Peterson2000; Rodriguez & Tucker, Reference Rodriguez and Tucker2011) as well as disrupted parenting behaviors more broadly (Bert, Guner, & Lanzi, Reference Bert, Guner and Lanzi2009), which can contribute to maladjustment and psychopathology in the next generation, thereby transmitting to children negative sequelae of maltreatment in addition to maltreatment itself. Together, a better understanding of what facilitates intergenerational transmission of maltreatment and its sequelae is needed to inform critical efforts to interrupt such transmission.

Since the phenomenon of intergenerational transmission was proposed, studies have sought to explore relevant mechanisms. Classic explanatory frameworks have included social learning theory (Bandura, Reference Bandura1973), through direct modeling of abusive behavior, and attachment theory (Ainsworth, Reference Ainsworth1979; Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1978), through disrupted working models of relationships that influence subsequent relationships, including with one's children (Zeanah & Zeanah, Reference Zeanah and Zeanah1989). Caregiver mental health may represent another key pathway. Maternal depression has been associated with maltreating behaviors in early childhood (Windham et al., Reference Windham, Rosenberg, Fuddy, McFarlane, Sia and Duggan2004), potentially by reducing emotional resources to respond to caregiving demands. Furthermore, maternal depression is relatively easy to detect by self-report or clinical interview and also amenable to intervention, making it a tractable risk factor from a public health perspective. In this study, it is proposed that maternal depression in the perinatal period, occurring at the earliest intersection between generations, may fundamentally contribute to maltreatment and its sequelae in the next generation. Emerging findings from a separate stream of literature, that is, perinatal mental health, may be relevant for this hypothesis.

Perinatal mental health research is concerned with the study of prevalence, risk factors, and consequences of mental disorders during the perinatal period, common of which is postpartum depression (Wisner, Parry, & Piontek, Reference Wisner, Parry and Piontek2002). Of relevance, women who have experienced maltreatment as children are found at greater risk for postpartum depression (Alvarez-Segura et al., Reference Alvarez-Segura, Garcia-Esteve, Torres, Plaza, Imaz, Hermida-Barros and Burtchen2014; Choi & Sikkema, Reference Choi and Sikkema2016). While maltreatment history is a risk factor for psychopathology across the life course (Widom, DuMont, & Czaja, Reference Widom, DuMont and Czaja2007), it may particularly kindle depression in the postpartum period, a time fraught with hormonal shifts (Hendrick, Altshuler, & Suri, Reference Hendrick, Altshuler and Suri1998), physical recovery from childbirth (Brown & Lumley, Reference Brown and Lumley2000), and heightened demands of caregiving (Campbell, Cohn, Flanagan, Popper, & Meyers, Reference Campbell, Cohn, Flanagan, Popper and Meyers1992) that may also reactivate own early memories of caregiving. In turn, postpartum depression is recognized for its short- and long-term impacts on child outcomes (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Sikkema, Vythilingum, Geerts, Faure, Watt and Stein2017; Murray & Cooper, Reference Murray and Cooper1996), even beyond later maternal depression in the child's life (Hay, Pawlby, Angold, Harold, & Sharp, Reference Hay, Pawlby, Angold, Harold and Sharp2003; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Arteche, Fearon, Halligan, Croudace and Cooper2010). This may be due to disturbances in maternal caregiving behavior and exposure to depressed maternal affect during a critical time for child development (Field, Reference Field2010), which could set a long-term foundation for negative interactions and increased vulnerability to emotional/behavioral problems. Thus, while there is likely no single factor underlying intergenerational transmission of maltreatment (Dixon, Browne, & Hamilton-Giachritsis, Reference Dixon, Browne and Hamilton-Giachritsis2005), maternal depression is expected to be an important conduit for transmitting negative outcomes to children, particularly during sensitive developmental windows such as the postpartum period.

Prior work with longitudinal cohorts has examined how the timing of maternal depression affects child outcomes (Barker, Reference Barker2013). To date, research has not disentangled timing effects of maternal depression in relation to intergenerational transmission of maltreatment (e.g., whether postpartum depression contributes critically to this transmission pathway or whether this is better explained by maternal depression across development broadly). A better understanding of timing effects would inform when interventions should best be targeted. According to a sensitive window hypothesis, maternal depression during the first year of life is expected to be uniquely impactful above and beyond later exposure(s) (Bagner, Pettit, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, Reference Bagner, Pettit, Lewinsohn and Seeley2010; Bureau, Easterbrooks, & Lyons-Ruth, Reference Bureau, Easterbrooks and Lyons-Ruth2009). This may be why treating maternal depression in early childhood has been suggested to reduce later maltreatment (McCann, Voris, & Simon, Reference McCann, Voris and Simon1992). However, no studies have formally examined postpartum and ensuing depression in the pathway between maternal childhood maltreatment and long-term child outcomes, including child victimization and later psychopathology. Alternatively, as early depressive episodes are known to kindle or increase risk for further episodes (Monroe & Harkness, Reference Monroe and Harkness2005), it could be that cumulative exposure to maternal depression is most noxious.

Furthermore, how intergenerational pathways vary across sex differences and maltreatment types has not been well examined. Growing literature suggests boys may be more sensitive to early environmental adversity (Rutter, Caspi, & Moffitt, Reference Rutter, Caspi and Moffitt2003), including maternal psychopathology in the perinatal period (Choe, Sameroff, & McDonough, Reference Choe, Sameroff and McDonough2013; McGinnis, Bocknek, Beeghly, Rosenblum, & Muzik, Reference McGinnis, Bocknek, Beeghly, Rosenblum and Muzik2015). In addition, literature on intergenerational transmission has tended to examine maltreatment exposure aggregated as a whole (Berzenski, Yates, & Egeland, Reference Berzenski, Yates, Egeland, Korbin and Krugman2014), whereas certain forms of maltreatment may be more likely than others to be transmitted via postpartum depression to the next generation. Comparative analyses would highlight forms of childhood maltreatment most likely to be carried forward into the next generation and thus most relevant for perinatal intervention.

To address these gaps in literature, this study drew on a large British longitudinal cohort of mothers and their twin children in which intergenerational continuity of maltreatment has been previously reported (Jaffee et al., Reference Jaffee, Bowes, Ouellet-Morin, Fisher, Moffitt, Merrick and Arseneault2013). The current aim was to test the mediating role of postpartum depression between maternal childhood maltreatment and a cascade of negative child outcomes, specifically child exposure to maltreatment, internalizing symptoms, and externalizing symptoms: (a) before and after adjusting for effects of later maternal depression, (b) comparing across sex differences, and (c) examining the relative role of maltreatment subtypes. Postpartum depression was expected to significantly mediate the relationship between maternal childhood maltreatment and child outcomes, above and beyond later maternal depression; to differentially affect female and male children; and to be particularly influenced by particular maltreatment subtypes such as emotional abuse (Minnes et al., Reference Minnes, Singer, Kirchner, Satayathum, Short, Min and Mack2008).

Method

Sample

Participants were mothers and children involved in the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study, which tracks the development of a birth cohort of British children. This cohort sample was drawn from a larger birth register of twins born in England and Wales in 1994–1995. Full details about the sample are reported elsewhere (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2002). Briefly, the E-Risk sample was constructed in 1999–2000, when 1,116 families (93% of those eligible) with same-sex 5-year-old twins participated in home visit assessments. Families were recruited to represent the UK population of families with newborns in the 1990s, based on (a) residential location throughout England and Wales and (b) maternal age, with overselection of teenaged mothers and underselection of older mothers having twins via assisted reproduction. Higher risk households were deliberately oversampled to compensate for their selective loss from the register due to nonresponse and likely attrition over time.

At follow-up, the resulting sample of households represented the full range of socioeconomic conditions in the United Kingdom, as captured by a neighborhood-level index (ACORN; A Classification of Residential Neighborhoods, developed by CACI Inc. for commercial use in the United Kingdom). ACORN utilizes census and other survey-based geodemographic data to classify neighborhoods across the United Kingdom into five categories ranging from “wealthy achievers” (Category 1; 26% E-risk families vs. 26% United Kingdom), “urban prosperity” (Category 2; 5% vs, 12%), and “comfortably off” (Category 3; 30% vs. 27%) to “moderate means” (Category 4; 13% vs. 14%) and “hard-pressed” neighborhoods (Category 5; 26% vs. 21%). The ACORN distribution of households participating in the E-Risk study closely matched the nationwide distribution across all categories (Odgers et al., Reference Odgers, Caspi, Russell, Sampson, Arseneault and Moffitt2012), though it underrepresented the “urban prosperity” category (e.g., young professionals) because such households are likely to be childless.

Procedure

Home visit assessments began in 1999–2000 when children were 5 years old, and follow-up assessments reported in this article were conducted when children were 7 (98% participation), 10 (96% participation), and 12 (96% participation). An overview of procedures at each assessment is publicly available (Medical Research Council, 2017). Informed consent was initially obtained from mothers and assent given by the children through their 12-year assessment. At all phases, procedures were approved by the Joint South London and Maudsley and the Institute of Psychiatry NHS Research Ethics Committee.

Measures

Maternal childhood maltreatment

Mothers were administered the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) as part of a structured face-to-face interview. The CTQ (Bernstein & Fink, Reference Bernstein and Fink1998) is a widely used 28-item scale that retrospectively measures exposure to maltreatment before the age of 18, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. An overall maltreatment score was available as a continuous variable (with possible scores between 25 and 125), as were continuous scores for each of the five maltreatment subtypes (with possible scores between 5 and 25). Continuous scores were used for all main analyses. As in previous E-Risk research (Jaffee et al., Reference Jaffee, Bowes, Ouellet-Morin, Fisher, Moffitt, Merrick and Arseneault2013) and for descriptive purposes, dichotomous variables were created to reflect moderate to severe exposure to each of the childhood maltreatment subtypes, as per CTQ manual cutoffs (Bernstein & Fink, Reference Bernstein and Fink1998), and substantial exposure to any childhood maltreatment was determined by moderate to severe exposure to at least one or more maltreatment subtypes.

Maternal postpartum depression

At the first assessment, mothers were interviewed by a trained clinician regarding their lifetime depressive symptoms up to when the twins were 5 years old, using the standardized Diagnostic Interview Schedule based on DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Mothers who met criteria for lifetime major depressive disorder were then asked to refer to the Life History Calendar (LHC) in order to specify the timing of their depressive episodes. If mothers did not meet criteria for lifetime major depressive disorder, their score on all reference periods was entered as zero. The LHC is a reliable visual method for recalling the occurrence, timing, and duration of life events, including psychopathology (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Moffitt, Thornton, Freedman, Amell, Harrington and Silva1996). Specifically, the reliability of recalling depressive episodes using the LHC method was separately evaluated using a 1-month test–retest and determined to be high at 93% (Kim-Cohen, Moffitt, Taylor, Pawlby, & Caspi, Reference Kim-Cohen, Moffitt, Taylor, Pawlby and Caspi2005). Mothers were asked to indicate whether they had experienced depression during various reference periods, including the first year following the twins’ birth (i.e., postpartum year). For postpartum depression, maternal reports of depression specifically during the postpartum year were extracted into a dichotomous variable.

Later maternal depression

Later maternal depression was assessed in study mothers using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule and LHC together across subsequent assessments. A variable was created to reflect the cumulative number of periods in which the mother was depressed between 1 and 10 years of the twins’ lives (1 to 4 years, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 years), with cumulative periods modeled categorically (ordinally) in all main analyses. This variable did not include maternal depression at 12 years to minimize conflation with reported child outcomes at 12 years. For descriptive purposes, a dichotomous variable reflecting any later maternal depression between 1 to 10 years was also derived.

Child exposure to maltreatment

Child exposure to physical and sexual maltreatment by an adult was assessed using a validated structured interview protocol (Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, Reference Dodge, Bates and Pettit1990) administered to mothers at each phase of assessment (5 years, 7 years, 10 years, and 12 years of twins’ lives). Details of this measure have been previously reported (Arseneault et al., Reference Arseneault, Cannon, Fisher, Polanczyk, Moffitt and Caspi2011; Jaffee et al., Reference Jaffee, Bowes, Ouellet-Morin, Fisher, Moffitt, Merrick and Arseneault2013; Polanczyk et al., Reference Polanczyk, Caspi, Williams, Price, Danese, Sugden and Moffitt2009). Briefly, standardized questions were designed to sensitively and validly elicit information about potential maltreatment (e.g., “Do you remember any time when your child was disciplined severely enough that he or she may have been hurt?” or “Next, I want to ask specifically about harm to your child of a sexual nature.”). At each phase, any positive reports were probed by the interviewer for further details about the incident and to rule out accidental harm or harm from peers. This narrative information was documented in a dossier along with maternal narratives and any referrals made. Each dossier was maintained over phases of assessment and then independently reviewed at 12 years by two clinical psychologists to reach consensus about likelihood of maltreatment occurrence between birth and 12 years of age. Initial interrater agreement between coders exceeded 90%, and discrepancies were resolved through consensus review. Child exposure to harm was indexed in a three-level categorical variable: none, probable, and definite. Examples of probable harm included instances in which a mother reported spanking her child and leaving marks or bruises, where sexually inappropriate behavior from an adult was suspected and resulted in preventive action, or where social services had been contacted due to concerns about child maltreatment. Examples of definite harm included instances where children sustained serious injuries from neglectful or abusive care, were discovered to be subject to inappropriate sexual contact from an adult, or were already registered on a child protective registry. A dichotomous variable was created to reflect likely maltreatment exposure (probable or definite) versus no such exposure, as in previous research (Jaffee, Caspi, Moffitt, & Taylor, Reference Jaffee, Caspi, Moffitt and Taylor2004).

Child internalizing and externalizing symptoms

Child internalizing and externalizing symptoms were measured at 12 years using the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991b; Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001) for mothers and the Teacher Report Form (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991a) for schoolteachers. Mother and teacher ratings were summed to provide an overall measure of child symptomatology across settings (Cairns, Mok, & Welbury, Reference Cairns, Mok and Welbury2005) and in order to incorporate multiple sources of variance, as children may behave or express emotions differently across settings. Continuous scores on withdrawn and anxious/depressed subscales were combined to form the overall internalizing problems scale, while continuous scores on aggressive and delinquent behavior subscales were combined to form the overall externalizing problems scale. Given combined mother–teacher ratings and use of a UK-based sample, overall raw scores were used and reported for all analyses.

Covariates

Maternal age in years reflected the mother's age when twins were born. Maternal socioeconomic status was indexed using a standardized composite of family income, education, and social class indicators measured at the first assessment. These correlated indicators were found to load significantly onto a single latent factor (Trzesniewski, Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, & Maughan, Reference Trzesniewski, Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor and Maughan2006). Based on cohort-wide distribution of scores on this latent factor, mothers were divided into three tiers reflecting overall socioeconomic standing. For this study, this variable was recorded to reflect increasing levels of socioeconomic disadvantage. Regarding descriptive child characteristics, categorical information on child sex (male vs. female) and twin zygosity status (monozygotic vs. dizygotic) was also obtained at the first assessment.

Analytic strategy

Main analyses

Descriptive analyses were initially conducted in SPSS (SPSS IBM v.23, Armonk, NY) to understand patterns of childhood maltreatment and depression as experienced by study mothers, and to characterize outcomes experienced by study children. Then, structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using Mplus v.7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2014) to test the hypothesized interrelationships between maternal childhood maltreatment, maternal postpartum depression, and child outcomes. SEM allows for associations to be simultaneously evaluated rather than estimating multiple independent regressions, and also permits estimation of both direct and indirect effects (Bollen, Reference Bollen1987). Data from both twins were included in the SEM analyses. To account for nesting within mothers, the data set was structured at the family level so that each twin's data were included as variables within the same family case, with elder versus younger twin variables distinguished accordingly. Twin outcomes on a same variable (e.g., externalizing symptoms) were mapped as indicators with equal factor loadings onto one latent outcome variable, as consistent with the common fate model for dyadic data (Ledermann & Kenny, Reference Ledermann and Kenny2012; Peugh, DiLillo, & Panuzio, Reference Peugh, DiLillo and Panuzio2013), with factor mean and variance set to zero and one, respectively. As a sensitivity analysis for this twin-based approach, a similar structural model was initially tested where only one child from each pair was randomly selected for a singleton analysis without latent twin variables.

To test continuity of maltreatment and related sequelae across generations, preliminary path analyses were conducted using maximum likelihood estimation to examine maternal childhood maltreatment scores as a predictor of each individual latent child outcome. Next, an overall structural model was used to test the extent to which postpartum depression mediates the association between maternal history of childhood maltreatment and child exposure to maltreatment and subsequent child internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Given the inclusion of categorical variables (e.g., postpartum depression) in the overall model, all subsequent analyses used weighted least squares means and variance adjusted estimation. Specifically, maternal childhood maltreatment was predicted to influence postpartum depression; postpartum depression was predicted to influence child harm exposure between birth and 12 years; and child harm exposure was predicted to subsequently influence child internalizing and externalizing symptoms at 12 years. Direct paths were also estimated between maternal childhood maltreatment and child outcomes, and between postpartum depression and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms, to explore any influences above and beyond the hypothesized pathway. Child internalizing and externalizing symptom residuals were allowed to covary. Within each twin pair, children were expected to be interchangeable, that is, meaningfully different on outcome variables based on order of birth (elder vs. younger). This assumption was explicitly tested using a chi-square difference test, which revealed no significant worsening of model fit for a nested model when outcome means and variances were specified as equal across elder and younger twins, so this specification was preserved throughout model testing. All possible indirect effects of maternal childhood maltreatment on child outcomes were queried.

SEM results were evaluated sequentially. First, to assess overall model fit, comparative fit indices (CFI/Tucker–Lewis index; with acceptable values >0.90) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; with acceptable values <0.08 and associated 90% confidence intervals [CIs]) were examined as statistical tests of the goodness of fit of the overall model (Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow, & King, Reference Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow and King2006). Second, the direct effects of maternal childhood maltreatment on child outcomes were examined. Third, the mediating effect of postpartum depression was evaluated. After this initial evaluation, maternal age and socioeconomic disadvantage were entered as covariates for all endogenous variables in the model. Fourth and finally, paths were added structurally to test the extent to which later maternal depression might carry the mediating effect of postpartum depression on child outcomes. This final model was again evaluated for overall fit as well as its direct and indirect effects. All effects were interpreted using standardized coefficients depending on the scale (continuous or categorical) of the independent variable.

Testing for moderation by child sex

To probe for potential differences in susceptibility to maternal risk across child sex, multiple-group testing was performed with the final model to determine whether structural pathways differed across male and female children. Chi-square difference tests were conducted to compare a model in which all structural paths leading to child outcomes were constrained across male and female groups, against a model in which these parameters were free to vary. In each model, pathways between maternal variables (e.g., maternal trauma to postpartum depression) were fixed as equal across groups, as they were not theoretically suspected to differ across male and female children. All other parameters were free to vary. If the chi-square difference statistic was nonsignificant, the more restricted sex-neutral model was considered acceptable given no substantial worsening in fit; conversely, a significant result would suggest that imposing parameter restrictions led to significantly worsened model fit, such that the sexes should be considered separately.

Examining role of maltreatment subtypes

To evaluate the relative impact of specific forms of maternal childhood maltreatment on child outcomes, both directly and indirectly through postpartum depression, a structural model based on the adjusted final model was tested to account for maltreatment subtypes using five predictor variables decomposed from the overall maltreatment variable (physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect). Intercorrelations between maltreatment subtypes were automatically factored into the model given their specification as exogenous variables.

Results

Missing data

Among the 1,116 E-Risk families, a small subset had CTQ data completed by an individual other than the mother (e.g., father or grandparent). These cases were excluded from the present study because the CTQ data would not reflect maternal trauma, leaving 1,038 families with CTQ data completed by the mother herself. Of these, 22 cases had missing maternal data (8 on postpartum depression and 14 on CTQ) and were excluded from analysis as weighted least squares means and variance adjusted estimation would handle this data using pairwise deletion, resulting in a final sample of 1,016 mothers and their children. The subsample with missing data did not differ significantly from the final analytic sample on socioeconomic categories, child sex, twin zygosity, or maternal age.

Descriptive findings

Sample characteristics are summarized in Table 1 for mothers and Table 2 for children. Of note, 18% (N = 180) of mothers endorsed clinical depression in the postpartum year, and the majority of these depressed women (83%, N = 150) reported at least some depression in later years, while 17% of mothers (N = 30) reported depression only in the postpartum year. Almost one in four mothers (24%, N = 248) experienced at least one type of childhood maltreatment at the moderate/severe level. The most common maltreatment subtype was emotional neglect (16%), followed by emotional abuse and sexual abuse (both 11%); physical abuse was reported by 8% of mothers, and 6% reported physical neglect. Among the children, there was a relatively even balance across gender as well as across identical versus fraternal twins. One in five children was determined to have experienced likely harm before 12 years of age.

Table 1. Maternal sample characteristics

Table 2. Child sample characteristics

Among mothers who reported postpartum depression, 40% (N = 72/180) had at least one child who was later exposed to maltreatment, compared to 22% (N = 188/836) among mothers without postpartum depression. Even in cases of discordant maltreatment exposure where only one twin was exposed to maltreatment, paired-sample t tests indicated the twin who was exposed to maltreatment had slightly higher but not significantly different internalizing or externalizing scores than the nonexposed twin, suggesting that a shared context where at least one child is being maltreated has consequences for both twins.

Structural model findings

Continuity of maltreatment and related sequelae across generations

In individual path analyses, maternal childhood maltreatment significantly predicted children's harm exposure (B = 0.32, p < .001), internalizing symptoms (B = 0.33, p < .001), and externalizing symptoms (B = 0.35, p < .001), supporting continuity of maltreatment and related sequelae in the next generation. These significant paths persisted even when adjusted for maternal age and socioeconomic disadvantage, which would be later added to the full structural model.

Mediating effect of postpartum depression on child outcomes

The main structural model with postpartum depression (Figure 1; significant paths shown, with standardized coefficients) fit the data well, χ2 (20) = 60.06, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.04, 90% CI [0.032, 0.058], CFI/TLI = 0.99/0.98, explaining 15% of variance in child harm exposure, 20% of variance in child internalizing symptoms, and 24% of variance in child externalizing symptoms (all p < .001). With regard to direct effects, maternal childhood maltreatment significantly predicted postpartum depression (B = 0.22, p < .001). In turn, postpartum depression significantly predicted child exposure to harm (B = 0.22, p < .001), which in turn predicted child internalizing (B = 0.27, p < .001) and externalizing symptoms (B = 0.34, p < .001). Maternal childhood maltreatment also had significant direct paths to each child outcome (p < .001; see Figure 1 for standardized coefficients).

Figure 1. (Color online) Main structural model with postpartum depression as mediator. Rectangles represent observed variables; ovals represent latent variables on which younger and elder twin scores have been regressed (paths not shown to improve readability). Solid lines represent paths with coefficients significant at p < .05* or p < .001***, with only significant paths shown in the model.

In terms of mediating effects, there was a significant indirect effect of maternal childhood maltreatment on child harm exposure through postpartum depression (B = 0.05, p = .002). For child internalizing symptoms, total indirect effects of maternal childhood maltreatment through the hypothesized model were also significant (B = 0.11, p < .001). Decomposition of specific indirect effects showed significant mediating pathways through the combined pathway of postpartum depression → subsequent child harm (B = 0.01, p = .011) and through child harm exposure alone (B = 0.07, p < .001). The indirect pathway through postpartum depression without child harm exposure was nonsignificant. For child externalizing symptoms, total indirect effects were similarly significant (B = 0.12, p < .001) and decomposition of specific indirect effects again showed significant mediating pathways through postpartum depression → subsequent child harm (B = 0.02, p = .004) and through child harm exposure alone (B = 0.09, p < .001). The indirect pathway through postpartum depression without child harm exposure was nonsignificant.

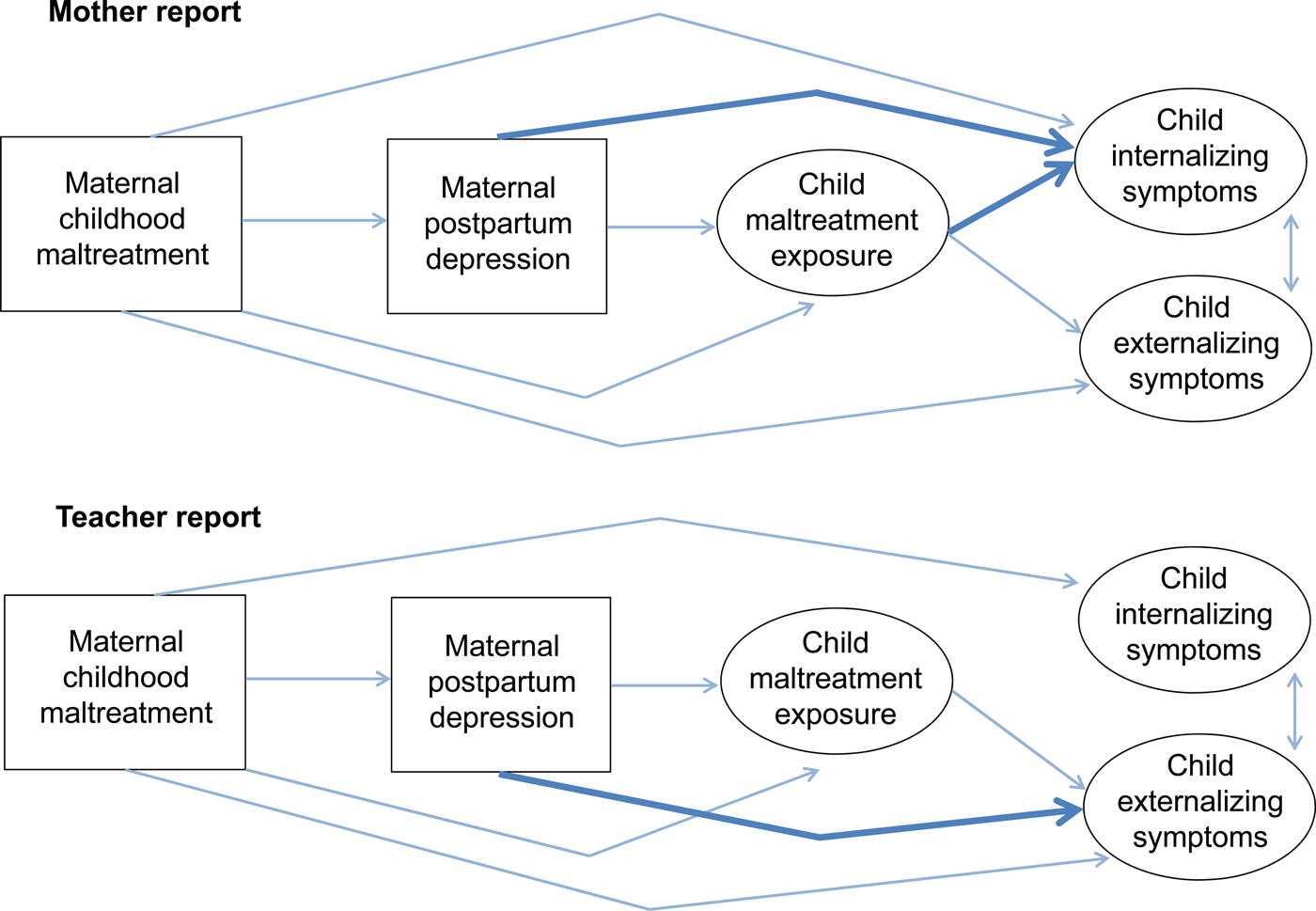

Sensitivity analyses

First, an analysis using only one randomly selected child from each twin pair revealed the same pattern of significant direct and indirect effects (not shown) as in the twin-based model; thus, the more comprehensive twin-based approach was conserved in subsequent analyses. Second, the comprehensive model was examined separately based on mother-only versus teacher-only reports of child symptoms, as opposed to combined reports. Each model continued to fit well, though minor pathway differences were found by informant (as shown in Figure 2). Specifically, when mothers reported on child symptoms, all model pathways were significant as before, but postpartum depression also predicted child internalizing symptoms directly, and thus significantly mediated between maternal childhood maltreatment and child internalizing symptoms above and beyond child harm exposure. When teachers reported on child symptoms, the pathway from child harm exposure to internalizing symptoms was not significant; however, postpartum depression predicted child externalizing symptoms directly, and thus significantly mediated between maternal childhood maltreatment and child externalizing symptoms above and beyond child harm exposure. While these results were used to contextualize main findings (see Discussion), combined reports across mothers and teachers were used in subsequent analyses as a comprehensive measure of child symptoms across settings was desired and different reporters are able to provide complementary evidence about children's emotional/behavioral problems (Cairns et al., Reference Cairns, Mok and Welbury2005).

Figure 2. (Color online) Sensitivity analyses of mother-only versus teacher-only informant reports. Rectangles represent observed variables; ovals represent latent variables on which younger and elder twin scores have been regressed (paths not shown to improve readability). Solid lines represent significant paths. Of note, bolded lines represent significant paths that were different across child outcomes as measured by mother-only versus teacher-only reports.

Adjusting for sociodemographic factors

The model retained good fit even when maternal age and socioeconomic disadvantage were added as covariates, χ2 (26) = 64.769, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.038, 90% CI [0.027, 0.050], CFI/TLI = 0.99/0.98, and the overall pattern of significant direct and indirect effects remained the same. In addition, socioeconomic disadvantage significantly predicted each of the child outcomes (B = 0.11, p = .010 for harm exposure; B = 0.16, p = .002 for internalizing symptoms; and B = 0.26, p < .001 for externalizing symptoms), while maternal age was a significant predictor of child harm exposure (B = –0.12, p = .004) such that younger mothers had a higher risk of later child harm. This adjusted model explained 19% of variance in child harm exposure, 22% of variance in child internalizing symptoms, and 30% of variance in child externalizing symptoms (all p < .001).

Exploring the potential role of later maternal depression

When later maternal depression was included structurally in the adjusted model so it followed postpartum depression and was also allowed to predict each of the child outcomes (see Figure 3; significant paths shown, with standardized coefficients), the resulting model continued to fit the data well, χ2 (30) = 96.35, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.047, 90% CI [0.036, 0.057], CFI/TLI = 0.98/0.97. In this model, maternal childhood maltreatment significantly predicted postpartum depression (B = 0.32, p < .001). Postpartum depression then significantly predicted later maternal depression (B = 0.66, p < .001), which in turn predicted child harm exposure (B = 0.18, p = .027), internalizing symptoms (B = 0.20, p = .016), and externalizing symptoms (B = 0.15, p = .033); however, postpartum depression was no longer a significant direct predictor of child outcomes. Maternal childhood maltreatment continued to have significant direct paths to each of the child outcomes (p < .001; see Figure 3 for coefficients). Socioeconomic disadvantage predicted later maternal depression (B = 0.131, p = .004), though not postpartum depression.

Figure 3. (Color online) Adjusted structural model including later maternal depression. Rectangles represent observed variables; ovals represent latent variables on which younger and elder twin scores have been regressed (paths not shown to improve readability). Solid lines represent paths with coefficients significant at p < .05* or p < .001***, with only significant paths shown in the model.

In terms of mediating effects, there was a significant total indirect effect of maternal childhood maltreatment for child harm exposure (B = 0.07, p < .001), specifically through the pathway that included both postpartum depression and later maternal depression (B = 0.04, p = .032). For child internalizing symptoms, there was a significant total indirect effect of maternal childhood maltreatment (B = 0.10, p < .001), through the specific pathways of postpartum depression → later maternal depression (B = 0.05, p = .021) and through child harm exposure only (B = 0.05, p = .004), but not solely through postpartum depression. The indirect pathway through postpartum depression → later maternal depression → child harm exposure was also marginally insignificant (B = 0.008, p = .080) after adjusting for covariates. For child externalizing symptoms, there was a significant total indirect effect of maternal childhood maltreatment (B = 0.11, p < .001), with specific pathways through postpartum depression → later maternal depression (B = 0.03, p = .039), postpartum depression → later maternal depression → child harm exposure (B = 0.01, p = .046), and through child harm exposure only (B = 0.06, p < .001), but not solely through postpartum depression. With the inclusion of later maternal depression, the model explained 20% of variance in child harm exposure, 24% of variance in child internalizing symptoms, and 34% of variance in child externalizing symptoms (all p < .001).

Testing the moderating effects of child sex

Means and variances were allowed to vary across male and female children; as expected, boys on average had higher externalizing symptoms than girls. When the moderating effect of child sex on structural paths was tested, chi-square difference tests revealed a significant worsening in model fit from the freed model (in which all structural paths to child outcomes were allowed to vary across males and females) to the more constrained model (in which these paths were set as equal), χ2Δ (17) = 29.41, p = .031. However, follow-up difference tests that constrained paths from either (a) maternal childhood maltreatment to child outcomes (direct effects) or (b) postpartum or later maternal depression to child outcomes (mediator effects) were nonsignificant, suggesting these paths were comparable across male and female children, at least when adjusting for all paths considered. Significant worsening in fit was found only when (c) paths from maternal demographic covariates to child outcomes were constrained across male and female children, χ2Δ (6) = 18.43, p = .005. Inspection of unconstrained path coefficients between groups revealed that in this model, maternal socioeconomic disadvantage predicted child harm exposure among males (p = .005) but not females (p = .993); internalizing symptoms for females (p = .005) but not males (p = .282); and externalizing symptoms for both sexes (p < .001). Younger maternal age at birth significantly predicted child harm exposure only for females (p < .001). These findings suggest some differential susceptibility of male versus female children to contextual risks but not to the overall intergenerational transmission of maltreatment through maternal depression.

Examining maltreatment subtypes

When all maltreatment subtypes were entered instead of overall maltreatment in the final structural model with covariates (Figure 4), the resulting model fit the data well, χ2 (46) = 104.94, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.036, 90% CI [0.027, 0.045], CFI/TLI = 0.98/0.96, and explained comparable variance in child outcomes as the overall maltreatment model, with similar pathways. Among subtypes, maternal histories of emotional abuse and sexual abuse were significant predictors of postpartum depression (B = 0.24, p < .001 for emotional abuse; B = 0.12, p = .005 for sexual abuse) above and beyond the other subtypes. In addition, maternal history of emotional neglect had significant direct paths to child harm exposure (B = 0.12, p = .017), child internalizing symptoms (B = 0.10, p = .042), and marginally externalizing symptoms (B = 0.07, p = .060). Maternal history of physical abuse had a significant direct relationship with child externalizing symptoms (B = 0.14, p < .001).

Figure 4. (Color online) Examining the relative contribution of maltreatment subtypes. Rectangles represent observed variables; ovals represent latent variables on which younger and elder twin scores have been regressed (paths not shown to improve readability). Solid lines represent paths with coefficients significant at p < .05* or p < .001***, with only significant paths shown in the model.

Discussion

Summary and integration

This study examined the mediating role of postpartum and subsequent depression in the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment and its psychological sequelae. It drew on a large birth cohort that was nationally representative of household conditions across the United Kingdom, in which mothers were not selected for their trauma histories or depression risk. The fact that almost one in five of mothers endorsed clinically significant depression in the postpartum year and nearly one in four had been exposed to at least one substantial form of childhood abuse or neglect supports the prevalence of these exposures at a population level and a need to understand how such exposures might affect outcomes in the next generation.

As expected, maternal childhood maltreatment was associated with greater risk for postpartum depression. Mothers who reported postpartum depression had nearly twice the prevalence (40% vs. 22%) of having a child exposed to later maltreatment. In SEM analyses, postpartum depression significantly mediated the relationship between maternal childhood maltreatment and child harm exposure, with subsequent influences on child internalizing and externalizing symptoms at 12 years. This mediating effect persisted even when accounting for socioeconomic disadvantage, suggesting that structural links observed between maternal childhood maltreatment, postpartum depression, and child outcomes were not simply explained by underlying levels of environmental adversity. These core results integrate findings from two separate streams of literature toward a more nuanced framework of intergenerational transmission, where (a) history of childhood maltreatment has been associated with increased risk for postpartum depression (Alvarez-Segura et al., Reference Alvarez-Segura, Garcia-Esteve, Torres, Plaza, Imaz, Hermida-Barros and Burtchen2014; Choi & Sikkema, Reference Choi and Sikkema2016), and (b) postpartum depression has been associated with a range of long-term child psychological outcomes (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Pawlby, Angold, Harold and Sharp2003; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Arteche, Fearon, Halligan, Croudace and Cooper2010). In this study, postpartum depression was linked to child outcomes mainly through risk of child harm, a cascade consistent with literature on maternal depression in the perinatal period (Pawlby, Hay, Sharp, Waters, & Pariante, Reference Pawlby, Hay, Sharp, Waters and Pariante2011; Plant, Jones, Pariante, & Pawlby, Reference Plant, Jones, Pariante and Pawlby2017).

Contrary to the sensitive window hypothesis, results indicated the mediating effect of postpartum depression from maternal childhood maltreatment on child harm and subsequent outcomes was carried by later maternal depression, consistent with recent literature (Agnafors, Sydsjö, deKeyser, & Svedin, Reference Agnafors, Sydsjö, deKeyser and Svedin2012; Sanger, Iles, Andrew, & Ramchandani, Reference Sanger, Iles, Andrew and Ramchandani2015). Most women with postpartum depression experienced at least some depression in later years, highlighting the persistent nature of maternal depression beyond the postpartum period. Some mothers who continue to be depressed may directly engage in abusive behavior, perhaps due to limited emotional resources in response to child misbehavior (Shay & Knutson, Reference Shay and Knutson2008); however, an alternative is they may be less able to actively monitor child safety or effectively protect the child from a violent partner or abusive acquaintance. The stronger effects of later maternal depression relative to postpartum depression might be explained in various ways. First, its occurrence is more proximal to child symptoms being assessed; developmental plasticity may have allowed intervening events to continue shaping outcomes beyond the postpartum period (Champagne, Reference Champagne2010). Second, it could be that cumulative exposure, as indexed by later maternal depression following postpartum depression, is particularly harmful (Halligan, Murray, Martins, & Cooper, Reference Halligan, Murray, Martins and Cooper2007; Hay, Pawlby, Waters, & Sharp, Reference Hay, Pawlby, Waters and Sharp2008). Third, an interaction effect may exist where early exposure to postpartum depression may sensitize children with genetic vulnerabilities to develop psychopathology but only when encountering later stressors such as continued maternal depression (Starr, Hammen, Conway, Raposa, & Brennan, Reference Starr, Hammen, Conway, Raposa and Brennan2014), representing a Gene × Environment × Environment interaction.

Moreover, findings suggested the overall intergenerational transmission pathway was robust to sex differences. Differential susceptibility of boys to maternal depression or history of childhood maltreatment was not supported in the current data, despite prior evidence of potential sex differences (Choe et al., Reference Choe, Sameroff and McDonough2013; McGinnis et al., Reference McGinnis, Bocknek, Beeghly, Rosenblum and Muzik2015). Lack of findings could reflect timing of child outcomes assessed. Another British longitudinal cohort (Quarini et al., Reference Quarini, Pearson, Stein, Ramchandani, Lewis and Evans2016) also revealed no sex differences related to maternal postpartum depression for child depression outcomes at 12 years; rather, potentially latent differences emerged at 18 years, with male children showing greater vulnerability following maternal postpartum depression.

When different maternal childhood maltreatment subtypes were considered together, emotional abuse emerged above and beyond other subtypes as a significant predictor of postpartum depression. While consistent with prior literature (Minnes et al., Reference Minnes, Singer, Kirchner, Satayathum, Short, Min and Mack2008), the present study extended this finding by examining its implications for child outcomes. Literature increasingly recognizes the uniquely harmful effects of emotional maltreatment (Hibbard et al., Reference Hibbard, Barlow and MacMillan2012; Spinazzola et al., Reference Spinazzola, Hodgdon, Liang, Ford, Layne, Pynoos and Kisiel2014). Given that maltreatment subtypes often co-occur rather than occur in isolation, a history of emotional abuse may also indicate the early maltreating environment was particularly noxious, containing a strong psychological component in addition to external harm. For clinicians, inquiring about childhood emotional abuse and neglect in addition to reports of past physical or sexual abuse may yield nuanced insights about mothers and children at greatest risk. Studying additional dimensions of maltreatment exposure, including the timing, severity, duration, and multiplicity of these experiences (Teicher & Parigger, Reference Teicher and Parigger2015), and how they uniquely perturb neurodevelopmental systems that may affect later psychopathology and/or parenting may illuminate further opportunities for prevention.

It must be noted that maternal childhood maltreatment continued to predict child outcomes above and beyond the maternal depression pathway, suggesting only partial mediation. This confirms how intergenerational transmission is a multifactorial phenomenon. Other mediators of this transmission could include hostile or controlling parenting styles, maternal substance abuse, or mental health disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder. Broader contextual factors such as domestic violence, household food insecurity, and neighborhood environments previously investigated in the E-Risk cohort (Belsky, Moffitt, Arseneault, Melchior, & Caspi, Reference Belsky, Moffitt, Arseneault, Melchior and Caspi2010; Jaffee, Caspi, Moffitt, Polo-Tomás, & Taylor, Reference Jaffee, Caspi, Moffitt, Polo-Tomás and Taylor2007; Jaffee, Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, & Aresneault, Reference Jaffee, Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor and Arseneault2002) may also be relevant, though our goal was to specifically ascertain timing effects of maternal depression. Algorithms of combined risk developed using computational learning methods (Mair et al., Reference Mair, Kadoda, Lefley, Phalp, Schofield, Shepperd and Webster2000) may be a promising direction for comprehensive prevention efforts, in which maternal depression and other contextual factors should be included as key indicators.

Furthermore, while not the focus of this study, it must be acknowledged that even in the presence of maternal risks, there was still substantial discontinuity in the transmission of maltreatment and related child outcomes. Mechanisms for resilience have been previously described in the literature (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti2013). Of relevance to the postpartum period, resilient child outcomes may be more likely when depressed mothers with maltreatment histories draw upon memories from early positive interactions with caregivers as they interact with their infants (Lieberman, Padrón, Van Horn, & Harris, Reference Lieberman, Padron, Van Horn and Harris2005) and when they continue displaying positive affect towards their infants despite some negative parenting behavior (Martinez-Torteya et al., Reference Martinez-Torteya, Dayton, Beeghly, Seng, McGinnis, Broderick and Muzik2014). Understanding how to promote these relational capacities in the presence of depressive symptoms may yield novel directions for intervening with mothers at risk.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First of all, study assessments did not index severity of postpartum depression beyond threshold for diagnosis, which would capture a range of symptomatology and potentially be more informative in predicting later outcomes (Fihrer, McMahon, & Taylor, Reference Fihrer, McMahon and Taylor2009). Given the study's initial focus on specific maternal risk factors such as depression, comprehensive psychiatric evaluation was not undertaken; thus, other mental health morbidities such as posttraumatic stress disorder or anxiety that could also influence risk transmission were not measured from the outset. Maternal childhood maltreatment was also measured retrospectively with the CTQ, which may be subject to underreporting (Brewin, Andrews, & Gotlib, Reference Brewin, Andrews and Gotlib1993) though has been found to correspond well to other sources of maltreatment information (Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge, & Handelsman, Reference Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge and Handelsman1997) and should be considered a reasonable index of actual exposure. Similarly, mothers reported on postpartum depressive episodes as part of a retrospective clinical interview. Though this validated measure has been shown to increase accuracy of recall (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Moffitt, Thornton, Freedman, Amell, Harrington and Silva1996), recollection of prior depressive episodes may be biased by current mood and functioning at time of assessment. Findings would benefit from replication and extension using cohort studies with prospective data on maternal risk factors starting before birth. Our results converge with a recent study examining antenatal and postpartum depression in the transmission of negative outcomes in a prospective cohort (Plant et al., Reference Plant, Jones, Pariante and Pawlby2017).

Second, as the E-Risk study was conducted in the United Kingdom, results and policy implications may not be generalizable to other settings. For example, maternal and child health care systems in the United Kingdom are nationally managed, such that average British mothers may have greater access than mothers in the United States to supports and services throughout the course of their children's development, potentially mitigating intergenerational risks. In addition, the use of a twin-based sample could also limit generalizability to singleton families, despite sensitivity analyses using only one randomly selected twin from each pair. For instance, mothers of twins may experience higher levels of depression (Thorpe, Golding, MacGillivray, & Greenwood, Reference Thorpe, Golding, MacGillivray and Greenwood1991). However, findings from this study resonate with others that have observed intergenerational links between maternal childhood maltreatment, maternal mental health, and child psychological outcomes in nontwin families (Plant et al., Reference Plant, Jones, Pariante and Pawlby2017; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Chen, Slopen, McLaughlin, Koenen and Austin2015).

Third, there was potential for informant bias as mothers reported on their own maltreatment history and depression as well as children's outcomes, albeit at different time points. We attempted to mitigate this by separately testing the model using only mother or teacher reports of child symptoms. Results suggested that the proposed intergenerational pathway to child externalizing symptoms was robust across informants and particularly salient when teachers reported these symptoms, while the pathway to child internalizing symptoms was only significant when mothers reported these symptoms. Differential pathway results may reflect how externalizing symptoms are more obvious across settings, while mothers may be more likely than teachers to observe subtle internalizing symptoms within home contexts. Drawing on multiple informants and/or objective child assessments in future studies will clarify whether current findings for child internalizing symptoms are better explained by informant bias or actual contextual variation. In addition, child harm exposure over time was documented carefully by trained clinicians but did rely on caregiver self-report, which may result in biased estimates, though formal child registries may also underestimate actual cases compared to sensitively elicited personal reports (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Kemp, Thoburn, Sidebotham, Radford, Glaser and MacMillan2009).

Fourth, this study did not explicitly rule out genetic mediation of intergenerational transmission, in which genetic factors shared between mothers and their children predispose them similarly to elicit maltreatment from their environment and/or demonstrate overall psychological vulnerability. For example, difficult temperament, a putatively heritable characteristic, may elicit both negative parenting behavior and parental depression (Dix & Yan, Reference Dix and Yan2014). To examine genetic versus environmental mediation, studies could draw upon adoptive mother–child cohorts (McAdams et al., Reference McAdams, Rijsdijk, Neiderhiser, Narusyte, Shaw, Natsuaki and Eley2015) or recruit egg donor in vitro fertilization samples where the mother carries the pregnancy without being genetically related to the child (Thapar et al., Reference Thapar, Rice, Hay, Boivin, Langley, van den Bree and Harold2009), to examine whether evidence converges across these types of studies. Fifth and finally, while postpartum depression appeared to partially link maternal trauma and child outcomes, it could reflect causal effects of maternal depression prior to birth (e.g., during pregnancy), though we were not able to explicitly test this in our study. Future research should factor in the previously observed role of antenatal depression in intergenerational transmission (Plant, Barkerm Waters, Pawlby, & Pariante, Reference Plant, Barker, Waters, Pawlby and Pariante2013; Plant et al., Reference Plant, Jones, Pariante and Pawlby2017) and test relative contributions of antenatal, postpartum, and later maternal depression to refine timing of interventions, as well as potentially synergistic effects of combined maternal depression and maltreatment histories.

Implications

For treatment and prevention, this study has highlighted the predictive utility of postpartum depression for the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment and its sequelae. Elevated maternal depressive symptoms at any point after birth appear to increase risk of intergenerational transmission, and these symptoms may appear as early as the postpartum period. Postpartum depression could serve as a useful early marker, that is, part of a clinical endophenotype, for intergenerational risk, one amenable to detection and intervention. This aligns with national recommendations (Siu & the US Preventive Services Task Force, Reference Siu2016) to screen for postpartum depression when follow-up options are available. Postpartum interventions may be strategic as mothers may be open to treatment and support during this time (Leis, Mendelson, Tandon, & Perry, Reference Leis, Mendelson, Tandon and Perry2009). For example, efforts have been made to incorporate depression treatment into home visiting programs (Ammerman et al., Reference Ammerman, Putnam, Altaye, Stevens, Teeters and Van Ginkel2013), but program effects appear to be attenuated by maternal histories of maltreatment (Ammerman, Peugh, Teeters, Putnam, & Van Ginkel, Reference Ammerman, Peugh, Teeters, Putnam and Van Ginkel2016), suggesting that depressed new mothers with trauma histories may require specialized attention and integrated interventions that simultaneously address trauma and mental health. Among psychotherapeutic options, one example is mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, which was developed to prevent depression relapse (Morgan, Reference Morgan2003) and may be especially effective for individuals with childhood trauma (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Crane, Barnhofer, Brennan, Duggan, Fennell and Russell2014). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy has demonstrated promise for preventing perinatal relapse in women with prior depressive episodes (Dimidjian et al., Reference Dimidjian, Goodman, Felder, Gallop, Brown and Beck2016). Mothers with trauma histories could benefit from such intervention, but it is unknown whether effects would extend beyond the postpartum period into later years.

Identifying and treating maternal depression in the earliest years may be an important way to interrupt cycles of trauma and improve maternal and child outcomes: an efficient strategy from a public health standpoint. However, postpartum depression may be most predictive of poor child outcomes within a course of maternal depression that is ongoing or recurrent, often including depressive episodes that onset before and/or during pregnancy. Research increasingly suggests that postpartum depression is not a homogeneous condition (Kettunen, Koistinen, & Hintikka, Reference Kettunen, Koistinen and Hintikka2014; Vliegen, Casalin, & Luyten, Reference Vliegen, Casalin and Luyten2014). For a subset of women, such as those with maltreatment histories (Nanni, Uher, & Danese, Reference Nanni, Uher and Danese2012), postpartum depression may reflect more chronic lifelong vulnerability for depression. These mothers should be clinically distinguished from those experiencing a more “classic” state of postpartum depression associated with hormonal shifts and acute life transition. While both groups require support and intervention, this study suggests there is a two-generation impetus for targeting mothers with chronic trajectories. Given the likelihood of recurrent depression, mothers with maltreatment histories should be monitored for depressive symptoms beginning in pregnancy and at later points in their child's life, and treated accordingly when symptoms elevate. Obstetric/gynecological and pediatric settings offer a prime opportunity to detect ongoing maternal depression and related risk factors that could affect child development (Earls, Reference Earls2010).

Conclusion

This study found that postpartum depression, especially when followed by recurrent maternal depression, plays a mediating role in the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment. Mothers who have experienced childhood maltreatment are at increased risk for postpartum depression, and their postpartum depression may also be more persistent and difficult to resolve, with downstream consequences for children's well-being. This study contributes to a growing body of evidence that children's risk for exposure to maltreatment and subsequent mental health problems can be predicted as early as the perinatal period, offering a promising window of opportunity for prevention. Some gaps in knowledge remain, including whether and how targeting early maternal depression can yield enduring effects for children, or require maintenance throughout childhood. Nonetheless, interventions that address both depression and trauma in the context of caregiving are critically needed for mothers in the perinatal period (Ammerman et al., Reference Ammerman, Peugh, Teeters, Putnam and Van Ginkel2016; Muzik et al., Reference Muzik, Rosenblum, Alfafara, Schuster, Miller, Waddell and Stanton Kohler2015) and may assist ongoing efforts to interrupt intergenerational cycles of maltreatment.