INTRODUCTION

Agility is the call of recent times and attaining superior agility has become indispensable for almost every organization to survive in persistently changing and competitive environments. Prior researches have defined organizational agility as a dynamic capability that promotes effective integration and assimilation of organizational resources, such as knowledge and technological assets, and can boost up firm’s performance for a longer time frame (Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj, & Grover, Reference Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj and Grover2003; Tallon & Pinsonneault, Reference Tallon and Pinsonneault2011; Zelbst, Sower, Green, & Abshire, Reference Zelbst, Sower, Green and Abshire2011). Previous studies have also documented various factors namely, organizational capabilities, effective governance, culture, human resources, etc. as important contributors to agility (van Oosterhout, Waarts, & van Hillegersberg, Reference van Oosterhout, Waarts and van Hillegersberg2006; Tseng & Lin, Reference Tseng2011). However, very little research support the systematic assessment of these factors in context to agility (Ashrafi, Xu, Kuilboer, & Koehler, Reference Ashrafi, Xu, Kuilboer and Koehler2006; Cai, Huang, Liu, Davison, & Liang, Reference Cai, Huang, Liu, Davison and Liang2013; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015b). In recent times, organizations function in a fast-moving, volatile, and competitive business environment and deal with immense pressure to sustain forces from various stakeholders. Therefore, it is imperative that firms continually transform their assets, infrastructure, and strategies to adapt into internal as well as external environmental changes, as per the needs of stakeholders.

Presently, the contribution of information technology (IT) has been widely accepted as a key element for the survival and growth of business firms (Bhatt & Grover, Reference Bhatt and Grover2005). Drawing on the resource-based view (RBV) theory, business houses have acknowledged greater IT capability as an underpinning of generating firms’ ability to identify and act in response to market-related changes (Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj, & Grover, Reference Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj and Grover2003; Tallon, Reference Tallon2008; Lu & Ramamurthy, Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011). IT capability is defined as the ability of the firm to organize and employ IT-based resources in coordination with other organizational capabilities to better realize IT’s business value (Bharadwaj, Reference Becker2000). Another stream of research highlights on the knowledge-based view (KBV) theory, which focuses on proper acquisition of knowledge assets to realize enhanced business value which is an important factor of organizational agility (Becker, Reference Bharadwaj2001; Dove, Reference Dove2002; Ashrafi et al., Reference Ashrafi, Xu, Kuilboer and Koehler2006). From the KBV perspective, the knowledge management (KM) capability is defined as an organizational capability that deals with effective mobilization and deployment of knowledge-based resources along with other organizational resources to gain superior business/economic value and sustainable competitive advantages (Grant, Reference Grant1996; Chuang, Reference Chuang2004; Kearns & Lederer, Reference Kearns and Lederer2004).

Although literature supports IT as an enabler of agility (Roberts & Grover, Reference Roberts and Grover2012), the contradicting role of IT as an impeding factor toward organizational agility cannot be overlooked. According to Lu and Ramamurthy (Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011: 932), ‘IT may hinder and sometimes even impede organizational agility.’ Hence, these mixed observations imply the necessity of precisely understanding the role of IT toward exploring the development process of agility. Following Overby, Bharadwaj, and Sambamurthy (Reference Overby, Bharadwaj and Sambamurthy2006), ‘agility’ is a very complex construct and to investigate about its enablers, it needs to be broken down into its constituent parts, such as ‘sensing agility’ and ‘responding agility.’ Based on these arguments quick and innovative responses may be treated as primary elements for organizational agility and IT capability has the ability to transfer high velocity of information so as to rapidly sense and generate appropriate responses regarding unprecedented market changes (Lu & Ramamurthy, Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011). Some information system (IS) research scholars have suggested the role of a complementary organizational capability along with IT capability to attain enhanced agility and KM capability in particular is the most suitable complementary capability that is highly essential to foster firm’s innovation (Darroch, Reference Darroch2005; Kamhawi, Reference Kaplan, Schenkel, Von Krogh and Weber2012). In this view, both IT and KM capabilities should be thoroughly studied as critical antecedents of organizational agility.

Notwithstanding, various IS literature argue that firms’ continual investment in IT and KM resources make them agile for unfolding persistent market changes, there is a lack of agreement about how IT and KM capabilities contribute toward enhanced organizational agility. According to RBV concept, some scholars claim that business process, and market responsive/capitalizing agilities are important components of firm’s internal and external business operations, respectively (Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj, & Grover, Reference Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj and Grover2003; Lu & Ramamurthy, Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011). Since, both of these elements refer to efficient and prompt response to market-related threats (Tallon, Reference Tallon2008), they need to be thoroughly studied for linking IT capability and organizational agility. Moreover, based on the theory of KBV, past literature has emphasized on the importance of effective KM or intellectual ability to gather and process wide-ranging information to recognize and anticipate external changes (Dove, Reference Dove2001). The essence of studying KM capability and agility association holds good for addressing rising customer needs with continual observation and quick improvement of product/service offerings.

The traditional RBV and KBV theories mainly depict only the internal operational mechanisms used by a firm for creating competitive advantage; thereby it overshadows the importance of the external business environment (Aragon-Correa & Sharma, Reference Aragon-Correa and Sharma2003; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a). Hence, a more integrated analysis representing the influence of contextual factors on the internal business operations is needed to respond to changing business environment (Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang, & Chow, Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a). Based on prior researches, external factors such as environmental uncertainty (diversity, dynamism, hostility), nature of competition, information intensity, industry-type, organizational climate, etc. may be considered as potential moderators to influence the IT-organizational performance linkage (Yayla & Hu, Reference Yayla and Hu2012; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014). However, very few studies have incorporated these factors to assess IT–KM–agility connection. So far, limited studies have investigated the joint effects of IT and KM capabilities on the organizational agility taking into account of the exogenous variables (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Huang, Liu, Davison and Liang2013; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a). Moreover, the literature supports very little research done on empirically investigating the relationship of IT and KM capabilities with agility in contemporary business environments (Ashrafi et al., Reference Ashrafi, Xu, Kuilboer and Koehler2006; Kohli & Grover, Reference Kohli and Grover2008; Lu & Ramamurthy, Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Huang, Liu, Davison and Liang2013; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a).

Addressing these research gaps, the present study tends to focus on an empirical analysis that explicitly discusses on the prominent influence of environmental factors, namely environmental diversity and environmental hostility on the IT–agility and KM–agility associations. The central theme of our study is to develop and test a research model that thoroughly assesses the relationship of IT and KM capabilities with the market responsive and business process organizational agilities. Therefore, this study addresses the following research questions:

Research question 1: Do IT capability and KM capability facilitate business process and market responsive organizational agilities?

And, if so;

Research question 2: What is the moderating effect of contextual variables, namely, environmental diversity and environmental hostility on the IT–agility and KM–agility associations?

REVIEW OF LITERATURE AND HYPOTHESES BUILDING

Organizational agility

According to Lu and Ramamurthy (Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011), organizational agility represents a firm’s capability to cope with unexpected internal and external business environmental changes by means of rapid and innovative responses. These types of responses reflect the characteristics of agility and foster organizational growth by assisting firms to acknowledge market-related changes as opportunities. Agility also facilitates swift and easy business processes refinement approaches to deal with volatile and imminent market changes (Dove, Reference Dove2001; van Oosterhout, Waarts, & van Hillegersberg, Reference van Oosterhout, Waarts and van Hillegersberg2006).The present study investigates two organizational agility constituents namely, market responsive (externally focused) and business process (internally focused) agilities.

Market responsive agility

The market responsive agility represents the ease at which the needs and preferences of customers are identified and accordingly existing products and/or services are modified or new products and/or services are launched to meet the customers’ expectations (Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj, & Grover, Reference Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj and Grover2003; Lu & Ramamurthy, Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011; Panda & Rath, Reference Panda and Rath2016). The data from external environment guide the senior executives to transform the internal data into meaningful information and make suitable decisions regarding new product and/or service developments. Therefore, this type of agility exhibits the intellectual characteristic, that is a competitive and growth-oriented entrepreneurial mind-set to transmit strategic decision making in unanticipated market environments (Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj, & Grover, Reference Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj and Grover2003).

Business process agility

Business process agility underpins the inevitability of a firm to recognize feasible business environmental changes, opportunities, and threats with pertinent reconfiguring abilities of assets, infrastructure, business processes, etc. to provide quick and decisive responses to customers and other stakeholders (Mathiyakalan, Ashrafi, Zhang, Waage, Kuilboer, & Heimann, Reference Mathiyakalan, Ashrafi, Zhang, Waage, Kuilboer and Heimann2005). This type of agility is a fundamental and rare form of organizational capability that facilitates reengineering of internal business functions to adapt into persistent market-related changes (Raschke, Reference Raschke2010). It also denotes swiftly and physically remodeling of the internal business processes corresponding to changes in market or customers’ demands (Panda & Rath, Reference Panda and Rath2016). Firm’s business process agility highlights on effective assimilation of business operations that facilitate implementation of innovative ideas and decisions.

IT capability and RBV of the firm

Numerous management researchers have been fascinated by the concept of RBV, which primarily explains the ability of the firm to deliver sustainable competitive advantage by virtue of firm-specific rare, unique/inimitable, nontradable, valuable, and nonsubstitutable resources (Finney, Campbell, & Orwig, Reference Finney, Campbell and Orwig2004; Hooley & Greenley, Reference Hooley and Greenley2005). In addition, these unique resources should be able to add value to the firm. According to Bharadwaj (Reference Becker2000), the RBV of the firm ascribes greater financial performance to a diverse range of organizational resources and capabilities. Understanding the fact that IT is a prerequisite for the firm’s survival and growth, the RBV perspective of IT emphasizes on the firm’s IT investments to generate unique IT resources and capabilities so as to enhance the overall effectiveness.

Following these arguments various IS researches have represented IT capability as an important organizational capability which is imperative for realization of greater business value (Rai & Tang, Reference Rai and Tang2010; Fink, Reference Fink2011; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014). Bharadwaj (Reference Becker2000) has explained about three key components namely, human IT resources, IT infrastructure, and IT enabled intangibles as pivotal factors to study IT capability. The human IT resources comprise of technical and managerial personnel with appropriate skills. Tangible physical IT resources like computers, hardware, etc. consist of the IT infrastructure, and customer orientation, elevated synergy, knowledge assets, etc. indicate intangible assets enabled by IT. Literature suggests extensive analysis on the impact of IT capability on augmented corporate performance (Bharadwaj, Reference Becker2000; Tallon, Reference Tallon2008). Still there are only few studies that explain the contribution of IT capability toward enhanced agility in contemporary business environments (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014; Chen, Wang, Nevo, Benitez-Amado, & Kou, Reference Chen, Wang, Nevo, Benitez-Amado and Kou2015). Drawing on the RBV rationale, previous IT capability-related studies have illustrated the interrelatedness among the technical, managerial, or human resources as vital IT capabilities (Bharadwaj, Reference Becker2000; Bi, Kam, & Smyrnios, Reference Bi, Davidson, Kam and Smyrnios2011; Bi, Davidson, Kam, & Smyrnios, Reference Bi, Kam and Smyrnios2013). Following Byrd and Turner (Reference Byrd and Turner2001), technical IT capabilities in combination with appropriate IT infrastructure mediate the association of IT capability with competitive advantage. They have also investigated managerial IT capabilities exhibiting an imperative impact on the technical expertise with effective employment of hardware, software, and proper network-sharing to decrease the threat of technological inflexibility which may hamper the organizational agility.

Link between IT capability and agility

In order to foresee the imminent market changes an effective IT governance model collectively sets strategic goals between business and IS executives and thereby, assists firms to deploy IT for resolving business-related issues (Weill, Subramani, & Broadbent, Reference Weill and Ross2002; Weill & Ross, Reference Weill, Subramani and Broadbent2004). It is essential for business executives to concentrate on flexible IT planning which in turn facilitates smooth internal operations and therefore, fosters development of new and innovative products and services. The research conducted by Weill, Subramani, and Broadbent (Reference Weill and Ross2002) and Lu and Ramamurthy (Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011) propose that there exists a correlation between IT capabilities and organizational agility. Based on the RBV theory, application of unique, rare, and inimitable technical and managerial IT skills have the ability to create long-run competitive advantages and help the firm in dealing with uncertain market changes. Therefore, the following hypotheses are formulated exhibiting the IT capability–agility relationship.

Hypothesis 1: IT capability has a significant positive effect on business process agility.

Hypothesis 2: IT capability has a significant positive effect on market responsive agility.

KM capability and KBV of the firm

Previous studies conducted by Balogun and Jenkins (Reference Balogun and Jenkins2003) and Huizing and Bouman (Reference Huizing and Bouman2002) suggest that the KBV of the firm is an extension of the RBV rationale and assesses knowledge as the most important organizational resources. According to Ariely (Reference Ariely2003), this elucidation of ‘knowledge’ as a ‘resource’ provides evidence for the theoretical relationship between the RBV and the KBV. Since knowledge resources (intangible resources) are difficult to imitate, these are considered as central elements for sustainable differentiation and hence, ensure sustainable competitive advantages (Wiklund & Shepherd, Reference Wiklund and Shepherd2003).

Although, RBV considers knowledge as a source of firm’s competitiveness, some KBV researchers argue that RBV does not explain the firm’s specific knowledge needed to effectively integrate, coordinate, and mobilize firm’s resources and capabilities and therefore, fails to differentiate between diverse knowledge-based capabilities (Kaplan, Schenkel, Von Krogh, & Weber, Reference Kamhawi2001; Theriou, Aggelidis, & Theriou, Reference Theriou, Aggelidis and Theriou2009). Hence, the knowledge-based theorists suggest that firms need to emphasize on knowledge creation, application, protection, and knowledge transfer in order to build up strategic assets for higher levels of performance (Curado, Reference Curado2006).

Myriad of IS researchers have contended that effective KM plays an integral role in generating augmented business values (Dove, Reference Dove2002; Khalifa, Yu, & Shen, Reference Khalifa, Yu and Shen2008). Following Tseng (Reference Tseng and Lin2010), KM facilitates easy access to real-time knowledge on products, markets, competitors, etc., and thereby, fosters agility. Since, the literature suggests only a few studies that have empirically investigated the KM–agility connection (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Huang, Liu, Davison and Liang2013; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a), the present research takes the previous literature a step further and extends the existing concept of KM–agility linkage by meticulously examining their corresponding critical dimensions.

According to Gold, Malhotra, and Segars (Reference Gold, Malhotra and Segars2001) and Zaim, Tatoglu, and Zaim (Reference Zaim, Tatoglu and Zaim2007), knowledge infrastructure and knowledge processes are two critical constituents of KM capability, where the knowledge infrastructure can be measured from the technical, structural, and cultural viewpoints and knowledge processes start with knowledge creation and completes with knowledge utilization. Since, in most of the IS literature the KM capability has been documented from the process point of view (Tanriverdi, Reference Tanriverdi2005; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Huang, Liu, Davison and Liang2013; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015b) therefore, in this research also it has been studied as a process-related construct.

Link between KM capability and agility

On the basis of KBV concept, generally KM capability promotes agility by creating and developing innovative responses for firms dealing with uncertainty. According to Nonaka (Reference Nonaka1994), an efficient deployment of KM assists in processing implicit individual knowledge to get converted into explicit knowledge. Further, Gold, Malhotra, and Segars (Reference Gold, Malhotra and Segars2001) have suggested that firms orchestrated with KM capabilities have the ability to assimilate the transformed knowledge with the firms’ existing knowledge to generate another new knowledge that fosters managerial practices (Tanriverdi, Reference Tanriverdi2005). Therefore, innovative responses get emerged and facilitate firms’ smooth operations in persistent volatile market situations. In this context, the three types of KM capabilities namely product, customer, and managerial KM capabilities play an imperative role in assisting firms to cope with the market turbulence. For example, customer KM capability represents the ability of the firms to identify changing customers’ demands by acknowledging their taste and preferences and after recognizing these demand changes the product KM capability of the firms comes into action, where firms upgrade or modify their existing products and services development processes or create new products and services altogether. In order to fit into the continually changing business environment, the managerial KM capability delineates the firm’s ability to promptly react to these changes by making suitable transformations in the overall business processes. Therefore, the present study posits the following hypotheses illustrating the KM capability–agility connection.

Hypothesis 3: KM capability has a significant positive effect on business process agility.

Hypothesis 4: KM capability has a significant positive effect on market responsive agility.

IT capability–KM capability–agility linkage

Prior IT capability and agility-related researches report that IT capability acts as either an enabler or a disabler of organizational agility. For example, according to Fink and Neumann (Reference Fink and Neumann2007), IT fosters agility by generating positive operational and strategic outcomes. Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014) and Lu and Ramamurthy (Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011) have also underpinned IT capability as an enabler of various forms of agility: such as market capitalizing agility, business process agility, entrepreneurial agility, operational adjustment agility, etc. However, another group of researchers have explained the impeding role of IT capability in realization of greater agility. For instance, Rettig (Reference Rettig2007) has documented that data integration and process automation brought by IT may create rigidity by making change difficult for the organization and obstruct agility. Some studies have highlighted IT capability as an enabler as well as a disabler of agility. For example, Overby, Bharadwaj, and Sambamurthy (Reference Overby, Bharadwaj and Sambamurthy2006) explain that IT broadens the reach and richness of firm’s knowledge and business operations to augment agility, however, inefficient technology management and improper IT utilization impede agility.

Previous literature suggest that so far, limited researches have quantitatively examined the KM capability and agility relationship and most of the prior studies are qualitative in nature. For instance, Ashrafi et al.’s (Reference Ashrafi, Xu, Kuilboer and Koehler2006) qualitative research on KM capabilities demonstrates a positive influence on enterprise agility. In another qualitative research, Nazir and Pinsonneault (Reference Nazir and Pinsonneault2012) have explained the positive influence of knowledge integration, which is a KM capability-related construct on the sensing and responding firm agility. On the other hand Mao, Liu, and Zhang (Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a) have empirically investigated the effect of KM capability on organizational agility and established a positive relationship between them. Another research conducted by Cai et al. (Reference Cai, Huang, Liu, Davison and Liang2013) posit that KM capability is positively associated with operational adjustment and market capitalizing agility. Based on these previous researches the current study finds a motivation to empirically investigate the joint effects of IT and KM capabilities on firm agility along with the moderating influence of external environmental actors on these associations.

Environmental factors as moderators

Following the concept of ‘fit’ proposed by Venkatraman (Reference Venkatraman1989), greater volume of information and superior information processing capability are vital for an agile organization which effectively sense and efficiently respond to unanticipated environmental changes. Based on this logic, IT and knowledge capabilities are expected to be more dynamic in an unstable environment and accordingly firms may invest in terms of money, time, and effort in building these necessary capabilities to attain agility (Tallon, Reference Tallon2008). If the environment is rather stable and predictable huge investments relating to development of IT and knowledge capabilities produce fewer returns (Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a).

Some researchers have criticized the traditional RBV and KBV theories for highlighting only the internal mechanisms of the organization and understudying the effects of exogenous variables on the organizational effectiveness (Rueda-Manzanares, Aragon-Correa, & Sharma, Reference Rueda-Manzanares, Aragon-Correa and Sharma2008). A theoretical framework proposed by Aragon-Correa and Sharma (Reference Aragon-Correa and Sharma2003) exhibits environmental factors as moderators which influence the effective deployment of organizational capabilities for environmental strategy. Stoel and Muhanna’s (Reference Stoel and Muhanna2009) empirical investigation involves the moderating effect of environmental conditions on the IT capability and firm performance relationship.

According to Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014) an appropriate match between the internal mechanisms and exogenous variables is needed to realize superior organizational performance. Following Newkirk and Lederer (Reference Newkirk and Lederer2006), the research work conducted by Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014) suggests that ‘environmental factors’ primarily constitute environmental ‘hostility,’ ‘dynamism,’ and ‘complexity.’ They have studied these variables as moderators to empirically examine the IT capability–business process agility association in their research. However, as opposed to their prediction, they have found that environmental ‘dynamism’ does not show any significant positive moderating effect on this linkage.

Another study conducted by Mao, Liu, and Zhang (Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a) suggests that ‘environmental uncertainty’ characterized by ‘dynamism,’ ‘heterogeneity,’ and ‘hostility’ moderates the IT capability–KM capability–agility relationships. But, they have examined ‘environmental uncertainty’ and ‘organizational agility’ as first-order factors and hence, did not establish individual moderating effects of ‘dynamism,’ ‘heterogeneity,’ and ‘hostility’ on these connections. Bridging this gap, the present study investigates environmental factors in terms of two moderators namely ‘environmental diversity’ and ‘environmental hostility’ and focuses on examining their distinctive significant effect on the unique IT capability–business process and market responsive agilities relationships and KM capability–business process and market responsive agilities associations.

Environmental diversity

According to Wade and Hulland (Reference Wade and Hulland2004), firms need to redesign their business operations by applying varied and intricate knowledge to adapt in diverse environmental circumstances by means of adequately dealing with a wide range of stakeholders namely, customers, suppliers, and other external competitors. IT assists the top management to recognize the importance of building a strong IT capability and properly integrating it with the business processes (Kearns & Sabherwal, Reference Kearns and Sabherwal2007). Firms with superior IT and KM capabilities accurately gather, analyze, distribute vital information, and thereby successfully attain higher organizational agility. In practice organizations often encounter lots of challenges due to uncertain environmental factors such as product diversity, complexity in new product development process, high market competition, fluctuating competitors’ pricing schedules, unpredicted customers’ tastes and preferences, etc. (Newkirk & Lederer, Reference Newkirk and Lederer2006; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a). Therefore, it may be presumed that environmental diversity greatly contributes in the strategy-making process by assessing the organization’s IT and Knowledge capability effectiveness (Wade & Hulland, Reference Wade and Hulland2004; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a). Hence, based on this rationale, the following hypotheses are formulated.

Hypothesis 1a: The relationship between IT capability and business process agility is positively moderated by environmental diversity.

Hypothesis 1b: The relationship between IT capability and market responsive agility is positively moderated by environmental diversity.

Hypothesis 3a: The relationship between KM capability and business process agility is positively moderated by environmental diversity.

Hypothesis 3b: The relationship between KM capability and market responsive agility is positively moderated by environmental diversity.

Environmental hostility

Following Zahra and Garvis (Reference Zahra and Garvis2000), a hostile environment represents the existence of adversely affecting external forces in a firm’s internal operational environment. These unfavorable elements may include inefficient staff, excessive tax load, unsupportive government policies, unapproachable technology, vulnerable infrastructure, sluggish economic growth, etc. (Rueda-Manzanares, Aragon-Correa, & Sharma, Reference Rueda-Manzanares, Aragon-Correa and Sharma2008). These factors may create a hostile business environment which prevents firms from effectively utilizing IT and other organizational resources (such as knowledge assets) and thereby, proper IT capability and KM capability development is diminished (McArthur & Nystrom, Reference McArthur and Nystrom1991). Underdeveloped IT and KM capabilities slow down firm’s growth in terms of decreased innovation and investment in processes, thereby impede firm’s ability to rapidly identify and swiftly respond to market as well as customer-related demand changes. Therefore, firms that attempt to build up IT and knowledge capabilities by means of devoting time and necessary funding in a hostile environment may experience little return on their investments (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a). The research work conducted by Stoel and Muhanna (Reference Stoel and Muhanna2009) suggest that although firms effectively develop higher order IT capability, a hostile business environment obstructs their ability in making better strategic decisions relating to customization of product/services to suit individual customer, quick and effective response to changing customers’ and competitors’ strategy, effective organizational reengineering to better serve market place, etc. Following these arguments a hostile environment hinders firms’ ability to generate augmented organizational agility. Therefore, on the basis of this logic, the following hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis 2a: The relationship between IT capability and business process agility is negatively moderated by environmental hostility.

Hypothesis 2b: The relationship between IT capability and market responsive agility is negatively moderated by environmental hostility.

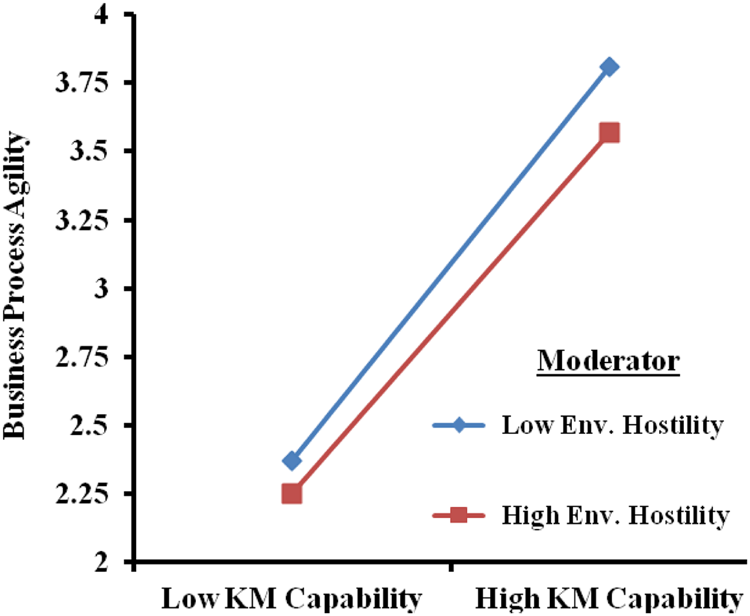

Hypothesis 4a: The relationship between KM capability and business process agility is negatively moderated by environmental hostility.

Hypothesis 4b: The relationship between KM capability and market responsive agility is negatively moderated by environmental hostility.

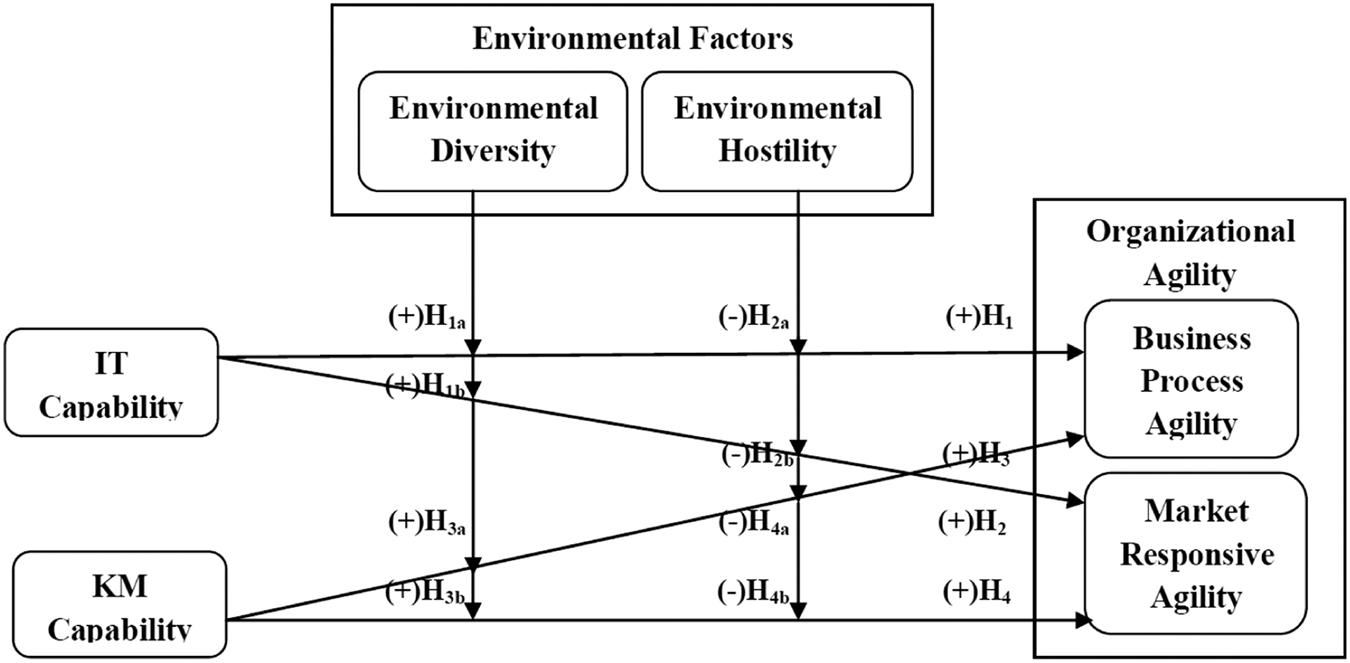

The conceptual research model representing all these above mentioned hypotheses is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The research model showing the relationship of information technology (IT) and knowledge management (KM) capabilities with business process and market responsive agilities

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Sample selection and data collection

In order to diminish the perplexing effect of industrial variation, this study was conducted on privately owned financial units such as Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of India (ICICI) bank, Housing Development Finance Corporation (HDFC) bank, insurance companies, and other financial services providing groups operating in the states of Odisha and West Bengal, in eastern India. In this context, the IT–KM–agility-related research is found to be very thin on the ground. Additionally, previous literature suggests that IT and KM capability may have a varied influence on agility in different countries. Therefore, it is important to study the effects of IT and KM capabilities on attaining superior organizational agility taking these units as target samples. According to Lu and Ramamurthy (Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011) and Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014), a matched-pair field survey is ideal for investigating IT–agility linkage. Addressing the future research avenues suggested by Mao, Liu, and Zhang (Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a), the current research utilizes this type of study to accumulate primary responses from the top management senior business and IT executives as the target informants.

In total, 930 numbers of structured questionnaires (700 no. of questionnaires for privately owned banks; 160 no. of questionnaires for insurance companies; and 70 no. of questionnaires for other financial groups, i.e., stock brokerages, consumer finance companies, and credit unions) were distributed, out of which 656 numbers of questionnaires were found to be usable for further analysis containing 325 and 331 responses from IT and business executives, respectively. The business executives were contacted in person and the e-mail addresses of IT executives were collected from them. Then, the IT executives were e-mailed questionnaires with detailed information regarding the procedure to answer the survey questions. Those IT executives who had not responded after the very first e-mail, reminder e-mails were sent to them after 15 days. In this case, an issue of nonresponse bias might take-place. Hence, regarding this issue, a statistical test namely ‘t-test’ has been conducted on all the studied constructs between the early (i.e., the responses collected immediately after the initial e-mail invitation was sent) and late (i.e., the responses collected after the reminder e-mails) responses. However, the results could not explain significant differences (since all ps >.05), and ascertain the absence of nonresponse bias problem. Eliminating the unmatched items and missing data, the final sample size was calculated to be 300 with a response rate of 32.25%. Table 1 illustrates the detailed sample profile.

Table 1 Sample profile (N=300)

Note. Others include stock brokerages, consumer finance companies, credit unions, credit card companies, etc.

IT=information technology.

Instrument development

Based on prior literature, the present research utilizes a 5-point Likert-type rating scale, containing both the extreme points as 1=‘strongly disagree’ and 5=‘strongly agree’ to accumulate responses for the multi-item constructs. All these studied measures have been adapted from prior researches which establish their validity, however, to check their validity in context to this study a series of tests relating to construct validity and reliability have been performed.

Measures for IT capability

Previous studies conducted by Bharadwaj (Reference Becker2000) and Lu and Ramamurthy (Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011) suggest that efficient deployment of IT infrastructure is necessary for the firms which reflects the firms’ ability to manage data management services, IT architectures, shared communication networks, portfolio application and services. Hence, IT infrastructure capability is considered as the first indicator. IT business spanning capability and IT proactive stance (Lu & Ramamurthy, Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011) are taken as the second and third item, where the former represents effective IT resources utilization to achieve business objectives and the later one delineates a firm’s ability to proactively explore diverse ways to identify and embrace innovative IT applications or make the best utilization of the existing IT assets to generate business opportunities. IT executives have been targeted as appropriate respondents for this construct.

Measures for KM capability

Following Tanriverdi and Venkatraman’s (Reference Tanriverdi and Venkatraman2005) and Tanriverdi’s (Reference Tanriverdi2005) research the current study identifies effective management of product knowledge, customer knowledge, and managerial knowledge (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Huang, Liu, Davison and Liang2013) as the three fundamental dimensions of KM capability. The product knowledge depicts the knowledge relating to new product development and its operationalization, the customer knowledge deals with necessary knowledge needed to comprehend the customers’ demands, buying behaviors, market situations, etc. and lastly the managerial knowledge entails knowledge involved in overall firm governance. For this construct, business executives have been set as suitable informants.

Measures for organizational agility

Organizational agility is operationalized taking business process and market responsive agilities as the two critical dimensions consisting of three indicators each. The business executives have been selected as the target participants for both these constructs.

Business process agility

Lu and Ramamurthy (Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011) and Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014) have suggested that business process agility is a crucial form of organizational agility and depicts how promptly firms respond to the changing market environment by modifying their internal business operations. Based on their research, the present study explores three critical indicators for this type of agility namely, customization of product/services to suit individual customer, scale up/down variety of products/services to better serve customers, and finally, introduction of new pricing schedules in response to change in competitor’s prices.

Market responsive agility

According to Bi, Kam, and Smyrnios (Reference Bi, Davidson, Kam and Smyrnios2011), Lu and Ramamurthy (Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011), and Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014) market responsive agility represents continuous environment scanning to comprehend the necessity of new products and services development corresponding to changing customers’ preferences and competitors’ strategy. Owing to these prior researches the present study examines this form of agility in terms of quick and effective response to changing customers’ and competitors’ strategy, quick development and marketing of new product/services, and effective organizational reengineering to better serve market place as the three critical indicators.

Measures for environmental factors

In this research environmental factors are studied as formative construct consisting of two reflective dimensions namely, environmental diversity and environmental hostility. Both IT and business executives have been selected as target participants for these factors.

Environmental diversity

Environmental diversity is measured by three items adopted from Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014) namely diversity in customer buying habits, diversity in nature of competition, and lastly diversity in product lines and nature of service provided to customers.

Environmental hostility

According to Newkirk and Lederer (Reference Newkirk and Lederer2006), a hostile business environment can be detrimental to an organization. The present work measures environmental hostility in terms of three items adopted from Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014) which are threat from scarce supply of man power, threat from tough price competition and competition in product/service quality, and finally threat from tough product/service differentiation. A detailed list of all the studied latent constructs along with their indicators is presented in Table 2.

Table 2 List of latent constructs along with indicators

Note. IT=information technology; KM=knowledge management.

While administration of the primary survey, data relating to various control variables such as firms’ age and firms’ size have been collected. These two control variables were selected based on past researches conducted by Bi, Kam, and Smyrnios (Reference Bi, Davidson, Kam and Smyrnios2011; firm size and firm age), Lim, Stratopoulos, and Wirjanto (Reference Lim, Stratopoulos and Wirjanto2012; firm size), Mao, Liu, and Zhang (Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a; organization size and organization age), Tallon and Pinsonneault (Reference Tallon and Pinsonneault2011; firm size). According to Spector and Brannick, ‘The distinguishing feature of control variables is that they are considered extraneous variables that are not linked to the hypotheses and theories being tested’ (Reference Spector and Brannick2011: 288). Based on these thoughts in this study the control variables have not been included as part of the hypotheses testing.

EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

Validation of instruments

Initially, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the accumulated data utilizing SPSS (20.0), out of which six numbers of factors were extracted through ‘principal component analysis’ method involving ‘varimax’ rotation. These extracted factors explained about 68% of variance. Afterwards, using the AMOS (20.0) tool a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) along with the interaction–moderation analysis have been conducted. The extracted six-component model consists of IT capability and KM capability as first-order factors and treated as the two exogenous variables. Organizational agility as well as environmental factors are exhibited as second-order constructs, where business process agility and market responsive agility represent the two endogenous variables and environmental diversity and environmental hostility denote the two moderators.

Generally the AMOS software is used for covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) and the researchers use the AMOS Graphic to effectively, accurately, and efficiently analyze the interrelationships among the latent constructs. Since the present research is of confirmatory in nature and involves theory testing, CB-SEM analysis is more appropriate comparing to variance-based structural equation modeling (SEM) (Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt2011). According to Astrachan, Patel, and Wanzenried (Reference Astrachan, Patel and Wanzenried2014), comparing to the variance-based SEM (e.g., partial least squares-SEM), the CB-SEM is the more widely used approach in SEM. Further, Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt (Reference Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt2016) suggest that CB-SEM analysis requires larger samples than partial least squares-SEM. According to Kline (Reference Kline2015), the sample will be considered as small if the size is <100; medium if the size ranges between 100 and 200; and large if the size is >200. Therefore, a sample size of 300 as determined in this study would be considered as large sample size. Although, there is an increasing trend of use of partial least squares-SEM by IS researchers, the CB-SEM approach using the AMOS would be more appropriate in this study. In order to confirm the construct reliability, construct validity, and good data fit, various tests have been performed which are explained in the subsequent sections.

Test for construct reliability

Reliability indicates the internal consistency of the items and evaluates the extent to which these items are free from random error. According to Hair, Black, Babin, and Anderson (Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010), the composite reliability and Cronbach’s α values ideally reflect the internal consistency of the unique and distinct items assigned under each construct. After the analysis, as shown in Table 4, the calculated composite reliability and Cronbach’s α values were found to be above the recommended value of 0.7 and thereby, confirms the higher reliability of the items studied under each construct. Similar test has also been conducted by Lu and Ramamurthy (Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011) to examine the reliability of their studied variables.

Test for construct validity

For this test, two separate tests such as the convergent and discriminant validity of items have been conducted.

Test for convergent validity

Following Hair et al. (Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010) the estimated average variance extracted (AVE) values for each latent construct greater than the standard value of 0.5 confirms the convergent validity of the items. As illustrated in Table 4 the calculated AVE scores certainly represent that every latent construct is well interpreted by its observed variables. A test of significance, that is a t-test has also been conducted to determine the t-statistics values which are found to be significant (since, all ps <.001) for all the factor loadings and thereby, establish the convergent validity criterion. Similar test has also been conducted by Bi et al. (Reference Bi, Kam and Smyrnios2013) to examine the convergent validity of the measures. In addition, as shown in Table 3 the factor loadings of discrete items on their assigned constructs are calculated to be highly significant. Moreover, the standardized estimates derived from CFA confirm that the convergent validity issue is not a probable threat for the latent constructs.

Table 3 Results showing exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and descriptive statistics

Note. The bold values have been obtained by EFA, utilizing SPSS (20.0). This extraction process involves ‘principal component analysis’ and ‘varimax’ rotation. However, the significance level of these values are not determined in EFA rather it is confirmed in confirmatory factor analysis. Only the values greater than 0.5 (the bold ones) have been considered for EFA. IT=information technology; KM=knowledge management.

Test for discriminant validity

Discriminant validity is estimated when the distinctive and unique values of the individual measures converge at their specific accurate scores. The AVE values represent the discriminant validity of the constructs and according to Gefen, Straub, and Boudreau (Reference Gefen, Straub and Boudreau2000), the square root of the AVE for each construct should be greater than the interconstruct correlation. Table 4 ascertains that all the studied constructs satisfy the discriminant validity criterion. Moreover, the maximum shared square variance and average shared square variance values are also considered as determinants of discriminant validity (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010) and as shown in Table 4 the maximum shared square variance and average shared square variance values are calculated to be less than the AVE values. Hence, it is proved that there is no discriminant validity issue for the constructs. Similar test has also been conducted by Panda and Rath (Reference Panda and Rath2016) to examine the discriminant validity of constructs.

Table 4 Results showing confirmatory factor analysis, correlation, and reliability of latent constructs

Note. Diagonal elements in bold are the square roots of average variance extracted (AVE).

ASV=average shared square variance; IT=information technology; KM=knowledge management; MSV=maximum shared square variance.

***p<.001.

Test for common method bias (CMB)

The current study has been carried out taking two categories of respondents such as business and IT executives to gather responses relating to various measures. As mentioned in the earlier sections both IT and business executives have been targeted for some items, such as environmental diversity and hostility. In such case CMB may be an issue. Although the participants have been assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of the survey, still a CMB test has been performed to diminish the threat of apprehension about assessment.

To examine the extent of CMB three types of tests have been conducted. First, Harman’s single-factor test in SPSS, second CFA in AMOS, and lastly common latent factor in AMOS. In the Harman’s single-factor test an exploratory factor analysis has been conducted containing all the 18 items by constraining the number of factors extracted to be 1 and the amount of variance extracted for this single factor was only 31%. According to Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), if CMB was an issue it would have extracted more than 50% of variance. This proves the absence of CMB problem. Afterwards a CFA has been performed on this single-component model (Kearns & Sabherwal, Reference Kearns and Sabherwal2007) and the results culminated in a poor fitting model where all the critical indices were calculated to be below their threshold values. For example: χ2=1,213.02, df=92, CFI=0.45, NFI=0.48, and GFI=0.52, IFI=0.42, AGFI=0.41, RMSEA=0.23. These fit indices certainly reveal that the studied variables are free from the issue of CMB. Similar tests have also been conducted by Lu and Ramamurthy (Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011) to test CMB. Lastly, again an exploratory factor analysis was conducted by taking all the 18 items in SPSS and then a CFA was carried out on the six-component model in AMOS. After that the standardized regression weights were calculated. Then a common latent factor was brought into the model and again CFA was performed. A comparison of the standardized regression weights of the model with common latent factor and without common latent factor represented a very small difference (i.e., less than 0.2). Therefore, it is ascertained that CMB is unlikely to be a potential threat to the data used for this study. Panda and Rath’s (Reference Panda and Rath2016) research also supports these approaches to examine the CMB of the studied constructs.

In order to validate both the measurement and structural models multiple data fit indices named as goodness of fit index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), incremental fit index (IFI), comparative fit index (CFI), relative fit index (RFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and ratio of χ2 to degrees of freedom (χ²/df), etc. were estimated. According to Hair et al.(Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010), the standard values of GFI, NFI, IFI, CFI, RFI, and TLI higher or equal to 0.90, RMSEA value below 0.08, and the ratio of χ²/df value below 3.0 or for larger sample size a higher value of 5.0 appropriately explain a good fit. All these fit indices were found to match the ideal values for both the measurement and structural models as exhibited in Table 5.

Table 5 Fit indices of measurement and structural model

Note. CFI=comparative fit index; GFI=goodness of fit index; IFI=incremental fit index; NFI=normed fit index; RMSEA=root mean-square error of approximation; RFI=relative fit index; TLI=Tucker–Lewis index.

Hypotheses testing

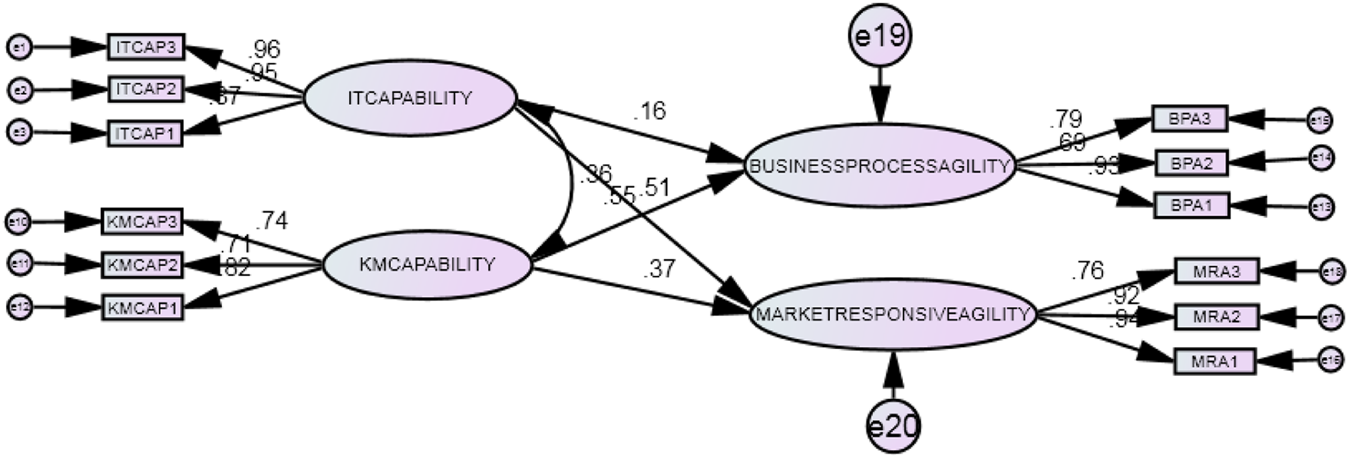

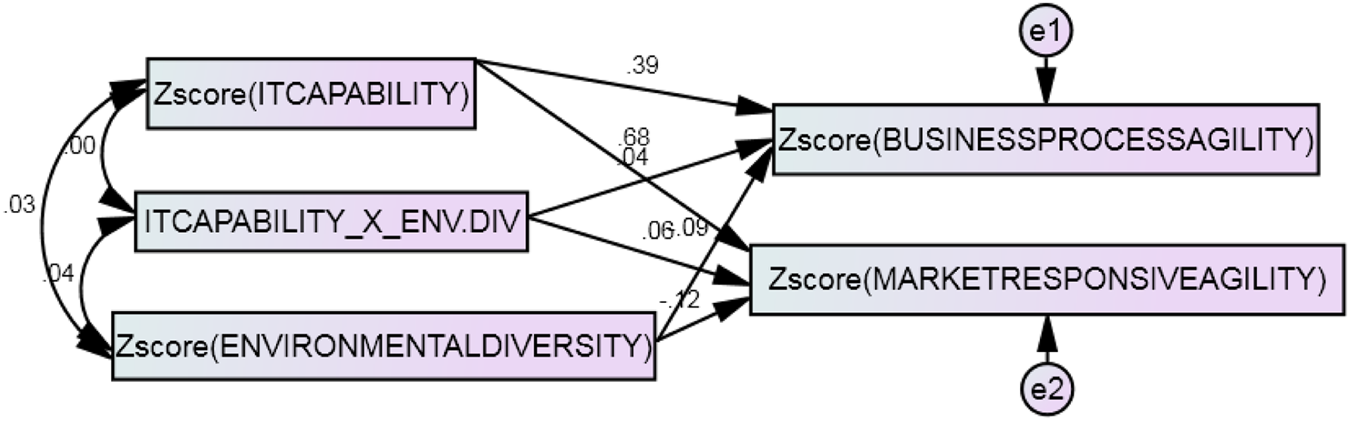

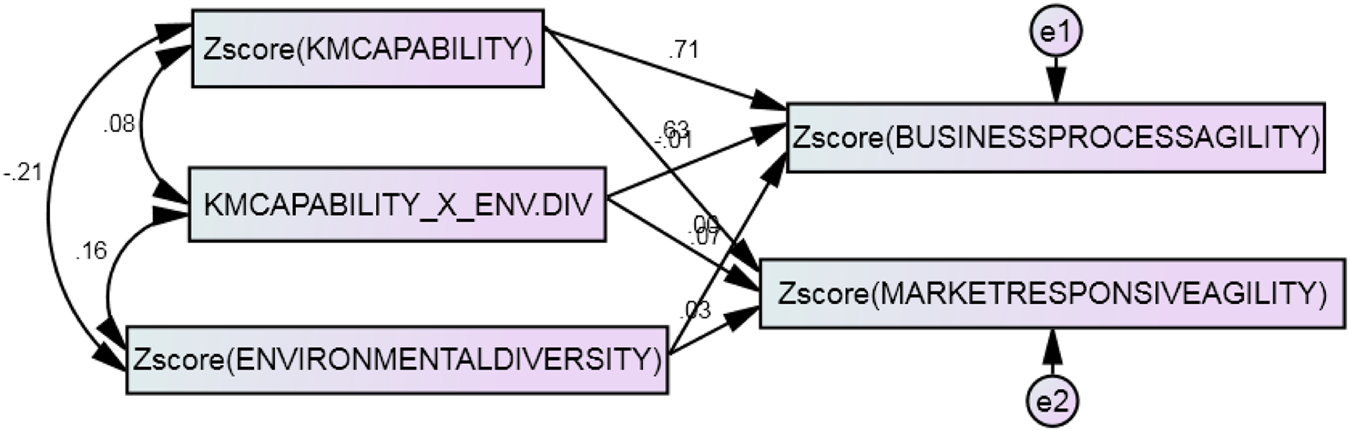

The current study has used the SEM approach to test the formulated hypotheses, where the results are derived on the basis of the path coefficients of the subconstructs. Similar SEM approach has also been followed by Panda and Rath (Reference Panda and Rath2016) and Tanriverdi (Reference Tanriverdi2005) to test the IT capability–organizational agility and IT relatedness–KM capability–firm performance associations, respectively. The Figure 2 represents the IT capability–KM capability–agility structural linkage and the interaction–moderation effects of environmental factors are shown in Figures 3–6.

Figure 2 Path diagram showing information technology (IT) capability-knowledge management (KM) capability–organizational agility structural linkage

Figure 3 Interaction effect of environmental diversity and information technology (IT) capability on business process and market responsive agility

Figure 4 Interaction effect of environmental hostility and information technology (IT) capability on business process and market responsive agility

Figure 5 Interaction effect of environmental diversity and knowledge management (KM) capability on business process and market responsive agility

Figure 6 Interaction effect of environmental hostility and knowledge management (KM) capability on business process and market responsive agility

Following Rai, Patnayakuni, and Seth (Reference Rai, Patnayakuni and Seth2006), in a regression model the path coefficients of the subconstructs can be considered as their β coefficients. Based on this concept from the Figure 2 it may be observed that the regression lines drawn from IT capability and KM capability toward both business process and market responsive agilities are showing positive path coefficients (structural link=0.16 and 0.51, p<.001 for IT capability and both business process and market responsive agility linkage; structural link=0.55 and 0.37, p<.001 for KM capability and both business process and market responsive agility relationship). Hence, Hypotheses 1–4 are supported. The interaction effects of environmental diversity and hostility with IT capability on business process and market responsive agility are presented in Figures 3 and 4. Figure 3 represents the positive relationship established between the interaction of environmental diversity and IT capability on both types of agility (structural link=0.04 and 0.05, p<.001), henceforth the proposed Hypotheses 1a and 1b are supported. On the other hand from Figure 4 it is apparent that the interaction of environmental hostility and IT capability is only showing a negative effect on market responsive agility (structural link=−0.04, p<.001), but with business process agility it represents a positive association. Therefore, it is inferred that the postulated Hypothesis 2b is supported and Hypothesis 2a is not supported.

The interaction effects of environmental factors and KM capability are exhibited in Figures 5 and 6, where in Figure 5 environmental diversity and KM capability interaction is showing a negative linkage with business process agility, but with market responsive agility it is showing no effect. Hence, both the formulated Hypotheses 3a and 3b are not supported. It is evident from Figure 6 that the interaction of environmental hostility and KM capability is showing a negative influence on business process agility (structural link=−0.04, p<.001), whereas the interaction is having no effect on market responsive agility. Therefore, it is suggested that the proposed Hypothesis 4a is supported but Hypothesis 4b is not supported. Results showing these hypotheses testing are illustrated in Table 6. The graphs exhibiting the interaction–moderation effects are plotted in the Figures 7–10.

Figure 7 The strengthening role of environmental diversity on the positive relationship between information technology (IT) capability and business process agility

Figure 8 The strengthening role of environmental diversity on the positive relationship between information technology (IT) capability and market responsive agility

Figure 9 The dampening role of environmental hostility on the positive relationship between information technology (IT) capability and market responsive agility

Figure 10 The dampening role of environmental hostility on the positive relationship between knowledge management (KM) capability and market responsive agility

Table 6 Results showing hypotheses testing

Note. IT=information technology; KM=knowledge management.

***p<.001.

DISCUSSION

Theoretical contribution

This research is based on various IT–agility, KM–agility, and IT–KM–agility-related theories (Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj, & Grover, Reference Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj and Grover2003; Tallon, Reference Tallon2008; Lu & Ramamurthy, Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Huang, Liu, Davison and Liang2013; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a). The research model represents the IT capability–agility (both business process and market responsive) and KM capability–agility (both business process and market responsive) relationships. In addition, the RBV and KBV theories have been adopted to conceptualize the IT capability and KM capability, respectively. Although the extant literatures suggest myriad of studies on the IT capability–agility and KM capability–agility connections, very few studies have jointly investigated the IT and KM capabilities’ effects on organizational agility following the RBV and KBV theories. Further, most of the previous IT and KM capability-related researches have been predominantly conducted in advanced countries such as United States of America (Bharadwaj, Reference Becker2000; Lu & Ramamurthy, Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011; Tallon & Pinsonneault, Reference Tallon and Pinsonneault2011), China (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Huang, Liu, Davison and Liang2013; Liu, Ke, Wei, & Hua Reference Liu, Ke, Wei and Hua2013; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a), and Australia (Bi et al., Reference Bi, Kam and Smyrnios2013), and so far no such studies have been conducted from a developing country perspective. Extending these previous researches, in addition to IT capability, KM capability, and organizational agility (both business process and market responsive), the research model contains contextual factors such as environmental diversity and hostility. Therefore, the adoption of such theories in context to a developing country such as India is well justified. These theories have been operationalized through the proposed research model and the combined effects of IT capability and KM capability on agility have been tested trough the SEM approach along with the moderating influence of environmental factors on these relationships.

The key inferences highlight that firms efficiently deploy IT and KM resources so as to enhance their capabilities to deal with changes in customers’ demands and competitors’ strategies. However, in the face of a highly diverse environment, where firms experience more diversity in customers’ buying habits, nature of competition, product lines, and nature of services, firms tend to better utilize their IT capabilities than KM capabilities. When firms encounter threats from scarce supply of man power, tough price competition, and product/service differentiation, IT capability acts as a disabler of market responsive agility, whereas these hostile environmental elements positively influence the business process agility. This means that firms make optimum utilization of their IT resources to deal with internally oriented activities such as customization of product/services, scale up/down variety of products/services, and introduction of new pricing schedules to cope with customers and competitor-related changes. However, they lack the ability to effectively employ IT resources to adapt into externally oriented activities such as quick and effective response to competitors’ strategy, quick development and marketing of new product/services, and effective organizational reengineering to better serve market place. This situation reverses in case of deployment of KM resources, that is, a hostile environment adversely influences firms’ abilities to deal with business process-related activities and it has no influence on firms’ responsiveness toward externally oriented changes. A plausible explanation for this is the resource constraints and uneven emphasis on both IT and KM resources between the business and IT units in developing countries. These critical findings provide better theoretical insights from a developing country perspective and indeed greatly contribute to the contemporary IS literature. The three-folded theoretical contributions are presented in the subsequent paragraphs.

First, this study empirically validates the positive effects of both IT and KM capabilities on organizational agility and thereby, supports the latest researches conducted by Mao, Liu, and Zhang (Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a) and Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014). Moreover, the findings provide additional evidence in supporting IT capability as a pivotal element in fostering business value and hence, can be treated as an enabler of agility (Lu & Ramamurthy, Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011). The inferences certainly address to the future research proposals suggested by Lu and Ramamurthy (Reference Lu and Ramamurthy2011) about connecting other resources with IT capability to enhance agility. According to Overby, Bharadwaj, and Sambamurthy (Reference Overby, Bharadwaj and Sambamurthy2006) and Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj, and Grover (Reference Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj and Grover2003), the agility strategy should not be limited to implementing IT and its capabilities because when IT capability gets imitated or replicated by other organizations, firms may get reduced competitive advantages. Hence, it is desirable that firms need to focus on other organizational capabilities such as knowledge capability to realize augmented agility. Therefore, the current study infers that the integrating effects both IT and KM capabilities are fundamental to attain superior agility.

Second, this study highlights the understudied KBV concept and extends the research by focusing on both the RBV and KBV theories. IT capability is certainly an inevitable aspect for enhanced business value, yet the significance of KM capability cannot be ignored. The findings also suggest that overall KM capability has more positive effect on agility compared to IT capability (structural link KM capability–both agilities=0.92>structural link IT capability–both agilities=0.67) which is consistent with other prior studies (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Huang, Liu, Davison and Liang2013; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a). Since, IT capability usually deals with the technology and its value, hence fails to provide the necessary implicit and explicit knowledge required for agility. Therefore, based on the RBV and KBV rationale, this study underpins the importance of effective IT capability investment along with building and optimizing KM capabilities to achieve greater agility.

Third, bridging numerous shortcomings of the traditional RBV and KBV concepts, this study tends to match the organization’s internal mechanisms with exogenous variables, namely environmental diversity and hostility. After a detailed analysis on the moderating effect of environmental factors on the relationship between IT capability–agility and KM capability–agility, it is obtained that environmental factors have more influence on the IT capability–agility relationship (since, three out of four proposed interaction–moderation-related hypotheses, i.e., Hypotheses 1a, 1b, 2b are supported) than KM capability–agility linkage (since, only one out of four proposed interaction–moderation-related hypotheses, i.e., Hypothesis 4a is supported). These findings suggest that a less hostile and more diverse environment create avenues for better IT performance to realize superior agility which are certainly consistent with prior researches (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Jin, Wang, Nevo, Wang and Chow2014; Mao, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Mao, Liu and Zhang2015a). Likewise, a less hostile environment is necessary for effective management of knowledge capital to attain greater process agility.

Practical contribution

The findings of this study provide numerous implications for management practices. First, the study underpins the significance of both IT and KM capabilities in realizing superior firm agility. Therefore, it is imperative for the managers and other decision makers to make necessary investment plans so that organizations achieve competitive advantages with leveraged IT and KM capabilities. Clearly for rational investment decisions, firms need to recruit and retain high-skilled and knowledgeable IT managers who proficiently develop apposite IT and knowledge competencies in order to attain augmented performance. Well-developed knowledge capabilities certainly facilitate technology to make a firm agile and foster its ability to readily identify and respond to unprecedented changes in the business environment. The inferences also suggest that although IT infrastructures are crucial, yet firms need to focus on effective integration of IT and business processes with an outlook to proactively explore different approaches to recognize and embrace innovative IT applications. Moreover, it is required that firms establish an efficient KM process so that the implicit knowledge gets converted into explicit knowledge. Then by combining this with the existing knowledge firms certainly create another distinctive new knowledge that fosters managerial practices. Hence, based on the findings, firms need to keep track of the changing customers’ demands and accordingly upgrade or modify their existing products and services for a better fit and thereby, acquire effective managerial KM practices.

Second, although the findings support that KM capability has more influence on agility, yet the management practitioners need to comprehend the significance of establishing, standardizing, and optimizing internal as well as external KM processes. This indicates obtaining, transferring, and utilizing knowledge from customers, partners, and suppliers. In order to attain greater agility it is also essential that the managers and decision makers promote a knowledge-sharing ambiance for the employees where they can freely share their customer-oriented and product-related knowledge. By doing so, the overall organizational knowledge gets continually updated and the organization makes appropriate strategic plans to deal with unanticipated changes.

Third, from the interaction–moderation analysis it is apparent that before making any investments in IT and knowledge resources, managers, and decision makers need to gauge a firm’s multifaceted external environment. Since, firms may have no influence or control over the external actors, a better understanding of these will be beneficial in making appropriate decisions. Our results indicate that the return on investment can be maximized only when the knowledge capability is developed in a less hostile environment and IT capability is established in a low hostility and high diversity environment. For example, firms that operate in a business environment comprising of a supportive government with favorable policies and legislation, and devoid of the pressure from unnecessary tax burdens, superior IT, and knowledge capabilities are expected to produce improved agility which in turn lead to enhanced performance. Managers need to focus on attaining sustainable competitive advantage with strong IT and knowledge capabilities to meet changing customer requirements and readily respond to market changes. Thus, firms learn to cope with the nuances of different environments.

Most of the previous studies have investigated IT–agility and KM–agility linkages either based on RBV or KBV concepts. However, this study combines these two theories to operationalize both IT and KM capabilities and empirically investigates their roles toward enhanced business and market responsive agilities and thereby, strongly contributes to the current IS literature. The findings suggest that IT and KM capabilities have positive effects on both the agilities, yet KM capability has more influence than IT capability. In addition, this research provides a more integrated analysis on the influence of contextual factors on the internal business operations. From the moderation analysis it is apparent that environmental factors possess more moderating influence on IT–agility linkage than KM–agility connection. To be specific, our research suggests that environmental factors (both environmental diversity and hostility) exhibit greater impact on the IT capability–agility (both business process and market responsive agilities) relationship compared to the KM capability–agility (where only environmental hostility demonstrates the influence on the KM capability–business process agility linkage). This implicates that in the face of a complex environment, firms equipped with superior IT capability have the ability to more efficiently collect, process, and disseminate market and customer-related information to attain greater business process and market responsive agilities. Additionally, managers need to carefully deal with diverse and hostile external environments for effective management of the IT-related activities. Furthermore, the research inferences recognize the significant contribution of firm’s IT and knowledge assets toward realization of greater operational efficiencies and suggest that firms need to effectively integrate the process of IT and knowledge capabilities development with the strategic business planning so as to obtain enhanced operational excellence. Putting all together, it is concluded that while IT is imperative for organizations to realize augmented agility, other organizational resources such as knowledge capabilities need to be established and formalized to quickly recognize and readily respond to unanticipated business changes. By doing so, firms develop adaptability toward a changing environment and accomplish sustainable competitive advantages in the long-run.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The study has encountered some limitations which are: first, the study was conducted in the states of Odisha and West Bengal in eastern India and confined to the privately owned financial groups only, which may restrict its generality. However, since the respondents suitably represent the whole population and possess a thorough understanding of the business operations, therefore, the findings may be extended for a larger context. Further, this study exhibits the value of this regional sampling and insists that it will help grasp the characteristics in emerging markets. Second, the IT and knowledge capabilities have been examined at a firm-level, while developing capabilities to realize superior agility are instigated at the individual business processes-level in distinct units or departments. Third, even though capability building and attaining agility are long-term processes, this study is based on a cross-sectional survey design. Fourth, this study has utilized different categories of respondents, that is, business and IT executives to collect the responses which may create a risk of apprehension about assessment and social desirability bias. However, the respondents were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their answers and the Harman’s single-factor test suggested that along with the CMB this particular issue was not found to be a serious concern for the study.

Future researches may examine the moderating influence of other external factors (i.e., market orientation, business strategic orientation, information strategic orientation, etc.) on the capability–agility association. Further research also may be extended to better understand IT and knowledge capabilities as enablers of greater agility and agile firms’ ability to establish superior IT and knowledge capabilities. Other research perspectives may include investigating both the capabilities toward enhanced agility at a business process-level as well as a firm-level. Since, the term ‘effects’ implies the causal IT–KM–agility linkage, therefore, instead of a cross-sectional research design a longitudinal or experimental research is desirable to examine this causation. The integration of RBV and KBV concepts also needs further investigation. The hypothesized research model may be studied in different cultures where the informants’ perceptions regarding environmental factors may vary. Responses accumulated from similar kind of participants of other industries holding different ownership structures, that is, public sectors financial enterprises, public or private-owned transportation, manufacturing, and telecommunication companies, etc. may be explored.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees of the journal for their extremely useful suggestions to improve the quality of the article.