It likely comes as no surprise that most of the literature on antiliquor legislation in the United States places prohibition at its center. The success of the dry movement in bringing about an amendment to the constitution banning alcohol production and sales, coupled with the spectacular failure of enforcement, has long been seen as a story worth telling. In this telling, however, dispensaries often merit nothing more than a passing mention.Footnote 1 Scholarly explorations of United States liquor dispensaries appear only in chapters in prohibition state histories,Footnote 2 the lone exception being South Carolina’s statewide dispensary system, which was a more significant and contentious than the local-option varieties adopted by its neighbors.Footnote 3

Placing prohibition at the center of anti-alcohol history obscures important pieces of the dispensary story in two ways. First, it relegates the dispensary to a brief experiment on the way to the inevitable adoption of prohibition. Second, in celebrating the activities of the Anti-Saloon League, Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and other dry campaigners, it characterizes dispensary supporters as merely “intellectuals and anti-prohibitionists” who “failed to gather sustained popular support for their recommendations.” This failing, scholars suggest, is the primary reason the dispensary option lost out, as in the American political system “ideas and information … are ineffective insofar as they are not promoted by organized groups able to overcome barriers to collective action.”Footnote 4

Yet dispensaries were more than just a scholarly-inspired speed bump on the way to an inevitable dry nirvana. Between 1891 and 1907, roughly one-third of state legislatures debated local and state dispensary plans. Seven states passed laws or held popular referenda establishing dispensaries, and in five of these state-run liquor stores existed for well over a decade. As Schrad points out, “The dominance of the prohibition option did not become fully established in the public discourse until about 1906.”Footnote 5 Scholars’ prohibition-centric focus leaves us few tools to explain either the timing or placement of the dispensary alternative. In fact, it makes it difficult to understand how, with limited public support, the dispensary option gained any policy traction.

Further, the deeper scholarly discussions we do have about the dispensary movement give the lion’s share of attention to the state monopoly system created in South Carolina.Footnote 6 While that story certainly merits such focus, it is not a good case from which to generalize to the dispensary movement as a whole. South Carolina’s system was the only state monopoly implemented prior to federal prohibition; each of the other states that had dispensaries saw them develop as a patchwork of municipal liquor stores. States other than South Carolina that did debate liquor monopolies considered and then rejected modified versions of the South Carolina scheme.

This article addresses these limitations, arguing that state-run liquor stores thrived in states that had a legislative history of local option. Within these states, the communities that adopted prohibition were most often those where prohibition had already been tried and then rejected because it did not prohibit and because prohibition cost the town in question revenue from liquor taxes. Similarly, the states that considered dispensary systems prior to federal prohibition were also those that were retreating from statewide prohibition. Dispensaries, then, were most often attempts by communities to create an alternative to prohibition that would both stem the illegal supply of liquor and recoup some of the lost revenue from this source.

Early Dispensary Experiments

The dispensary was an American adaptation of the “Gothenburg system” named for the Swedish city where it was first widely adopted. Gothenburg proponents argued that liquor dealers’ desire for continued profits incentivized them to push alcohol, even to those manifestly unable to control the urge to drink. To ensure the continued viability of their enterprise, the liquor trust would stop at nothing, including giving kickbacks to police to look the other way and using their saloons as staging grounds to get out the vote for public officials who would support liquor sales. The result was a liquor trust that gained money and influence at the expense of the suffering and addiction of others.

Dispensary advocates argued that complete prohibition, while ideal, was nonetheless unworkable in practice. If alcohol sales were outlawed, illegal liquor sellers with the same profit motives would spring up where licensed saloons used to operate, and these dealers would have similar motives to gain economic and political advantages as were possible in the legal system of liquor sales. Instead, they sought to remove the lure of profit by removing liquor sales from private hands and setting them in municipality-run retail outlets staffed by disinterested managers. Profits would go not to the liquor trust but to a public fund to promote the general welfare.Footnote 7

The Gothenburg plan received its first United States convert in 1891, when a municipal dispensary was adopted in Athens, Georgia. Athenians had grown tired of the lawlessness associated with their saloons and voted for prohibition in 1885. This county prohibition law initially made no exception for medicinal use, but concerns of local physicians led Athenians to opt for

a slight modification of the law to meet such cases as our physicians think need liquor to preserve their health… . Let each grand jury instruct the Ordinary to issue license to such drug stores as they see fit and proper to fill liquor prescriptions for regular practicing physicians in good standing residing in Clarke County. Then, require such drug stores to keep a list of every order they fill, with the name of the party who buys it and the physician that prescribes it. This record must be laid before the grand jury for critical examination, and they can judge as to whether any druggist or physician is abusing the privilege. If it is seen that any man has used an unnecessary amount of liquor, or a drug store has sold too much, or a physician is suspiciously liberal … then this body can instruct the ordinary to withhold further license.Footnote 8

Though seemingly a sensible nod to public health, this modification accomplished quite the opposite. Athens’ liquor dealers used this loophole to create a new type of business, the drugstore bar room, a dodge that was quickly exposed and lampooned:

Dr. Setemup is a regular practicing physician and the law gives him the privilege to prescribe and furnish liquor to his patients. He opens a drug store and invests the larger part of his capital in whisky and beer. Col. Thirsty feels that there is a vacuum attached to his anatomy and at once repairs to Dr. S. for “prescription.” The doctor proceeds to examine the throat of his new patient … decides that he needs a stimulant and writes one extending over several months… . It is not unreasonable to estimate that this little business will net its enterprising proprietor over $5,000 per annum— and all that he is required to pay for this privilege is … $100 physician’s tax to the city. Occasionally our vigilant Chief of Police will docket a few cases against Dr. Setemup; but it is a most amusing legal farce. The Doctor employs a lawyer, the witnesses swear that the liquor was sold to them under prescription … and the culprit is acquitted… . Thus, the work goes on from day to day… . The city loses its revenue from the liquor business, but there is no dimunition in the number of whisky drinkers or the amount of liquor sold.Footnote 9

Exposés pointing at both the continued access of easy liquor and the loss of municipal revenue continued unabated for another year, at which point the Weekly Banner opined, “This system of licensing drug stores to sell liquor is doing a great deal to break down the enforcement of the law… . Let us have our local (prohibition) bill amended so as to establish a dispensary in Athens… . Then let the city refuse to grant licenses and break up the blind tigers at any cost.”Footnote 10

The resulting bill created a bit of a stir as some Georgia lawmakers worried that Athenians were in fact more interested in recouping lost revenue than in controlling the liquor traffic, and would be tempted to increase dispensary sales accordingly. Once reassured that “the object (is) to kill the blind tigers,” and that “all the (University of Georgia) professors, the chancellor, the ministers of Athens, and all the prominent men in Clarke County (are) in favor of the bill,” the legislature acquiesced.Footnote 11 The result was

a public dispensary, presided over by an honorable man who is regularly elected and qualified and held amenable for violation of his duty by the mayor and council who fix his salary. Under this arrangement whisky can be had by any responsible person, not a minor, and not disgustingly habituated to its use without prescription being necessary. Under no circumstances can the purchaser drink it at the place of purchase. The city buys nothing but the purest brands and the profit is so fixed as to merely cover the cost of handling it. One of the most honorable church members of the city dispenses it, and so orderly is the place that a lady can go in and make a purchase for family use with as much security and as little embarrassment as if she should buy it from the best regulated drug store in the land… . [T]hey do not pretend to prohibit… . They merely propose to regulate the sale.Footnote 12

One municipal liquor store in a small southern college town might not have led any further, except that the goings-on in Athens caught the attention of South Carolina Governor Benjamin Tillman. Tillman was pushed to consider a dispensary system because of an 1892 state referendum that gave a majority to statewide prohibition. Fearful that enactment of such a law would create what one of his supporters called “the prohibition vortex, only fit to distract and disturb our social as well as political welfare,”Footnote 13 Tillman searched for a way to take the liquor issue out of politics. He seized on the Athens dispensary as a model and bullied his state legislature (most of whom owed their political careers to his farmers’ movement) to pass a “prohibition” bill that actually permitted alcohol sales—but only when done through state stores. When defending his scheme, Tillman echoed the experiences of Athens’ dispensary. He pointed out both that liquor was the cause of myriad personal and social troubles and that experience showed “the human family cannot be legislated into morality. All classes, men and women alike, feel, at times, the need of stimulants, and many who are never guilty of excess in their use resent any law infringing on their personal liberty.”Footnote 14 Focusing his attention on saloons as spaces in which urban whiskey rings could breed undue political influence (likely supporting his enemies), Tillman substituted a system of state-run liquor stores (dispensaries) that would permit only off-site consumption, thereby forcing men to “go elsewhere to consume it.”Footnote 15

Tillman also explicitly moved to undo the tax advantages urban saloons gave their constituents, decrying that “the liquor men live in the towns, they make money selling the liquor; the towns make money; the country suffers; the country pays for it; the country pays increased taxes for it.”Footnote 16 Dispensary profits went instead to rural South Carolinians—half going to the state and one-quarter each to the county and the state’s schools. By openly remarking on the financial repercussions of the dispensary, Tillman waded in more boldly to the question of profits that Athenians had soft-pedaled when making their plea to the Georgia legislature. In Tillman’s mind, those “fanatical unreasonable people who cry aloud against the iniquity of government’s sharing in the blood money from husbands and fathers addicted to whiskey” were misguided. In fact, local, state, and federal governments had long been addicted themselves to the revenue taxes liquor brought into their respective treasuries. Given this, Tillman asserted that “it is far-fetched, unreasonable, then—hypocritical in fact—to pretend that any disgrace can attach to the revenue feature.”Footnote 17

Both pro- and anti-Tillmanites divined that the governor’s promise of temperance and tax relief widened the groups that would form the dispensary’s constituency, although they viewed this alliance differently. The editor of the pro-Tillman Columbia Register praised the governor’s foresight, opining, “the passage of the dispensary bill will not weaken the Reform movement to any great extent. The prohibitionists will come over. The great majority of our white voters reside in the country and have no interest in sustaining the saloons. Liquor licenses do not lessen their taxes, and if they can procure all the whiskey required, and have the profits thereon returned to them, they will be content with the existing order of things.”Footnote 18 The State, meanwhile, heaped scorn on the bill’s supporters: “Some silly prohibitionists have supported this measure. Believing the sale of liquor to be criminal they have made the state and themselves partners in the alleged crime. Believing that men ought not to be allowed to drink they have aided in directing that the state shall sell them all the liquor they can pay for. Believing the profits of liquor selling to be the wages of the devil they have made a bid for a share of the profits… . It is a scheme to fill an empty treasury. That’s all.”Footnote 19

Despite Tillman’s claims of having merely borrowed the dispensary model from Athens, there were important differences in the two. Most prominent, the South Carolina model was a statewide enterprise imposed from above. In contrast, the Athens dispensary was a municipal concern resulting from a compromise between temperance advocates seeking the next best option after a failed prohibition experiment and other local leaders who sought to recoup lost revenue from alcohol. As the dispensary movement spread across the South, it was the municipal model that took the lead.

The Southern Municipal Dispensary Movement

Municipal dispensaries next appeared in North Carolina with an 1895 petition to the state legislature from the town of Waynesville. Similar to Athens, Georgia, Waynesville had adopted prohibition some years earlier and was dissatisfied with its results. Working directly from the Athens dispensary law, Waynesville’s state representatives sought a special local act that would permit their town to establish a dispensary of their own.Footnote 20 Once in operation, the Waynesville dispensary provided inspiration for other North Carolina towns to follow the same course in dealing with their liquor problems. “The new system,” wrote the Chatham Record, “is preferable to so-called prohibition with its drug stores and blind tigers.”Footnote 21 Summing up the annual report of Waynesville’s dispensary commission in 1897, the Waynesville Courier noted the $3,112 profit taken in by the town. While it was “sad to contemplate so much money being spent for liquors,” the editor argued it was better spent in the town dispensary than in saloons or blind tigers.Footnote 22

The 1897 and 1899 North Carolina legislative sessions fielded an ever-growing number of petitions from towns across the state asking for permission to create their own dispensaries. Typically these petitions included a substantial number of signatures and were accompanied by appointed representatives sent to Raleigh at their own expense to urge their towns’ cause before the legislature.Footnote 23 Although it is difficult to determine the makeup of these delegations, they appear to have been composed of civic leaders, as these would likely have been the people who could have afforded both the time and money required to make such appeals. Too, the specifics of their legislative testimony occasionally made clear their social position. One striking example comes from D. T. Oates, leader of the dispensary delegation from Fayetteville. In his appearance before the committee, he reviewed the petition of the dispensaries’ opponents and concluded its signatories were all “Negroes and drunkards would not get whiskey from the dispensary. He went over all the names, saying of them ‘he is a loafer, he is a drunkard, he was a bar keeper, he is a minor’ and the like.”Footnote 24

Municipal petitions and delegations were supported by more general petitions that give a sense of the positive light in which antiliquor forces held the dispensary. For example, the Baptist Young People’s Union of North Carolina wrote the legislature to

most humbly and sincerely petition your honorable body, to use every lawful and reasonable means within your power to pass the bills now pending for the establishment of dispensaries in certain towns and counties in North Carolina, and to use every honorable means to suppress the traffic that is cursing our State, blighting her young manhood, weakening all her citizens, crippling her schools and impeding the progress and usefulness of every church and Christian enterprise in North Carolina.Footnote 25

North Carolina dispensaries also found an ally in the head of the state Anti-Saloon League, J. W. Bailey. Although Bailey had no illusions that it was the final solution to the liquor problem, he viewed campaigns for dispensaries as necessary first steps to both eliminate saloons and build local sentiment for the antiliquor cause. So strong was Bailey’s belief, “when the dispensary issue was about to be carried to the floor of the (1905 state Anti-Saloon League) convention, he … threatened to resign if that alternative was not endorsed.”Footnote 26 Bailey’s efforts paid off, as he reported with pride that “the following towns have been carried by the Anti-Saloon League … for the dispensary (Elm City, Raleigh, Oxford, Wilson).”Footnote 27

Alabama was the next state to welcome the dispensary movement. It began there in 1898 with a local act establishing a dispensary in Clayton that followed along the same lines as the Athens, Georgia, law. After observing its operations for several months, the editor of the Clayton Record declared it “no longer an experiment … it is working admirably in all respects, morally and financially.”Footnote 28 Following Clayton, a dispensary was opened in Dothan, where again it received positive reviews in the local newspaper as the editor cited unnamed “prominent citizens” of the town who agreed that “the dispensary is the thing to solve the long troublesome liquor question.”Footnote 29

At this point matters took a slightly different turn from the singular reliance on legislative special acts that created dispensaries in Georgia and North Carolina as the legislature took up a statewide dispensary bill. This was not a state monopoly like South Carolina; instead it enshrined the dispensary within the already existing Alabama local-option system. Thus, county or municipal elections gave citizens the choice of voting for saloons, prohibition, or dispensaries, rather than having to appeal to the legislature.

The legislative prodispensary effort was aided greatly by the fact that “temperance forces in Alabama at that time were feeling a good deal of discouragement. The license system, the oldest form of liquor regulation, was far from satisfactory. High license fees, though they reduced the number of dealers, had the unfortunate effect of also concentrating control of the liquor traffic in the hands of a few political powerful men. Local option … was a disappointment; most of the counties had voted wet in the local option elections. The dispensary system was recognized by the temperance advocates as a compromise with evil, but it seemed almost a necessary compromise.”Footnote 30 Sensing the dispensary as a potential avenue for closing Alabama’s saloons, dry campaigners urged “immediate and vigorous action in its support [by] friends of temperance and good order.”Footnote 31 For their part, most of the secular Alabama newspapers favored the dispensary bill as well. As one example, the editor of the Alabama Courier (Athens) thought the dispensary system would pay for that city’s debt, making it “one of the most progressive towns in the state.”Footnote 32

The state dispensary bill became law in 1900 and spawned the development of dispensaries across Alabama. At its most expansive, the Alabama dispensary system included seventy-seven liquor stores placed in twenty-six of the state’s sixty-six counties. As dispensaries became more numerous, “they gained new friends among the stern moralists who approved the cold, crude, repellent atmosphere which made these distributing centers anything but a poor man’s club. The dispensary, they noted with approval, stripped the tinsel ad glamour from the buying and selling of whiskey.”Footnote 33 There was also the financial aspect, as in many towns the only expenses were the small rent and dispenser’s salary. Beyond this, more money was available for schools, roads, and other community improvements. According to the Alabama Courier, one (unnamed) dispensary town “abolished city taxation and used half the dispensary proceeds to put in a sewerage system.”Footnote 34 In Dothan, one citizen familiar with the city’s finances remarked that “if it had not been for our dispensary, our schools could not be absolutely free school as they are now.”Footnote 35

Why Only the South?

One of the most notable aspects of the municipal dispensary movement was that its location was limited to the three southern states discussed above and a much smaller number in Virginia. Studies of the southern prohibition movement have demonstrated that southern reformers saw the dispensary as a compromise that would take the liquor question out of politics and thereby prevent African Americans from asserting their political voice to decide the issue.Footnote 36 Too, southern evangelicals saw the dispensary as a way to control access to youth who might be tempted by the more alluring aspects of the saloon.Footnote 37

Although the uniquely southern obsessions with white supremacy and evangelicalism shed light on reformers’ motives, they likely would have been concerns across all the southern states, yet only a handful of those states adopted municipal dispensaries. To better account for the presence of the municipal dispensary movement in only some southern states, it is necessary to examine their history with special local legislation. Every single one of the dispensaries in Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia, as well as the first wave of liquor stores in Alabama, was enacted by a special act of the state legislature following a petition from the town in question. Southern legislatures’ openness to special local legislation was not to be found in legislatures outside that region. Szymanski (2003) points out that “with few exceptions, narrow temperance laws had ceased to be a source of new local licensing regimes in the North by the 1880s.”Footnote 38 Not only were northern state legislatures reluctant to use such measures, the constitutions of several northern states “included … limitations on the legislature’s capacity to pass local laws and issue special charters.”Footnote 39 Western state constitutions too carried some of these same limitations.Footnote 40

Within the south, Blakey (1912) documents that states varied in their openness to honoring municipal requests for special legislation around liquor issues. Not surprisingly, states with histories of endorsing local legislative requests continued to do so when dispensaries became the request (Table 1).

Table 1. Special Antiliquor Legislation in the South

Source: Leonard Blakey, The Sale of Liquor in the South, p. 39.

Table 2. Status of Towns Before Adoption of Dispensary

Sources: Alabama, Georgia, and North Carolina Auditors Reports.

Explaining Which Towns Adopted Dispensaries

Saying that towns in certain states would have the support of their state legislatures should they request liquor dispensaries tells us very little about why some towns asked for dispensaries in the first place. Although there was considerable variation among these places, one thing the majority of dispensary towns did have in common was a previous experience with local prohibition (see Table 2). We’ve seen above the quotes from both Athens, Georgia, and Waynesville, North Carolina, that referenced blind tigers and drugstores dispensing liquor under prohibition regimes and the worry that prohibition was therefore not prohibiting. These themes were echoed in other dispensary towns. “If prohibition would prohibit the Record would favor it,” opined the editor of the Clayton, Alabama, paper, “but for practical purposes … a dispensary is the thing.”Footnote 41 “Of course it cannot be denied that whiskey purchased at the dispensary makes men drunk,” allowed the Athens (Georgia) Banner. “Whiskey always makes people drunk when it is imbibed to an excess. Numbers of people get drunk from time to time out of a population of 12,000. They do so under prohibition, dispensary or barrooms.”Footnote 42 Given that all systems of liquor control were likely to fail at bringing about total abstinence, dispensary supporters pitched their preferred solution in terms of what was expedient, rather than what was ideal. As a dispensary supporter in Bainbridge, Georgia, put it, “While the great battle is waging to rescue your erring fellow man from the tortures of the drunkard’s death, … would you stand all the day idle, waiting for total prohibition? To establish a dispensary to prevent drunkenness is right.”Footnote 43 At its best, the dispensary assured that “the liquor evil is chained and the municipal authority which should be as good as the best element of society prescribes just what lengths the evil may be permitted to roam.”Footnote 44 In considering the workings of the dispensary in Fayetteville North Carolina, Reverend A. J. McKelway noted, “The adoption of dispensaries brought only pure liquor on which the tax had been paid, and the distilleries, having no outlet for their illicit trade, shut up shop. Statistics showed that drunkenness and the crimes resulting therefrom decreased… . The consumption of liquor was diminished … and merchants testified that the difference went into legitimate channels of trade.”Footnote 45

These isolated quotes give the impression that dispensary supporters were those people who lived in towns where local prohibition had been tried and found unsatisfactory because it did not prohibit. Adding to this impressionistic data are state auditors’ reports from Georgia, North Carolina, and Alabama. These show that the majority of dispensary-only towns in each state were dry prior to their adoption of municipal-run liquor stores.

Another piece of the dispensary argument in Athens was that prohibition’s failure to prohibit also led to lost liquor revenue. Residents of other dispensary towns made this claim as well, although they did so carefully, since appearing to be too enamored of liquor profits could lead to accusations that one was “blinded by the glare of gold.”Footnote 46 While it was true, wrote one Georgia man, that some people could use dispensary money to “send your children to school and educate them … this merely shifts taxes from one man’s shoulders to another’s. It takes the money from the poor degraded man who spends it for drink and relieves the strong wealthy citizen who spends for his farms and houses at reduced prices, at sheriff’s sales where whiskey and bad management have ruined men.”Footnote 47 Pointing out the hypocrisy that occurred when “we sell them the liquor and then put an apple on the Christmas tree,” another writer exclaimed, “Great God! How can a Christian people be so unconcerned about the lives and souls of the unfortunate for the paltry dollar?”Footnote 48 Failure to rectify this moral lapse would mean “a reckoning day is coming by and by. Our town may build, our county may pave roads from the money from this source but the tears of the wife whose support we have robbed and the cries of the children whose bread we have snatched by selling the father whiskey will cry out against us and the reverberation will be felt in generations yet unborn.”Footnote 49

While most advocates were cautious to speak openly about the profits a dispensary might bring, those who did venture into that conversation were quick to emphasize the social good achieved with liquor money. “Let the city have a dispensary,” argued a Bainbridge, Georgia, man. “Use the funds for paying the taxes of the city and for the building of an academy large enough to accommodate every boy and girl in reach of it and employ a sufficiency of first-class teachers to teach all branches of ABC’s on up to a first class law school; and let the children of our county go to Bainbridge to college instead of Athens, Macon, Oxford and other places.”Footnote 50 As dispensary profits added up, it became more and more unimaginable for any city, county or state to do without them. For citizens in dispensary towns “the profits go to support the country schools and to pay the expenses of the city government. If this revenue is abolished … every man who pays ten dollars in tax must pay fifteen … or the city must reduce the force of teachers, firemen and policem … who are so necessary to our welfare.”Footnote 51 Meanwhile, citizens in nondispensary counties looked on with envy at their neighbors. “We are very tired of seeing thousands of dollars going out of Sumter County to aid the schools and treasuries of other counties when we need this revenue.”Footnote 52

Again, as these quotes are only suggestive and taken by themselves, it’s difficult to know if they were representative. To explore this question further, I examined state auditor records that reported the amount of liquor taxes paid by county for the year before they adopted prohibition (Table 3). Liquor taxes paid to the state were pegged to the number of liquor dealers, and thus it’s likely that counties with greater state taxes also had greater local taxes as well. Although not conclusive, these data support the anecdotal evidence given in the quotes above: towns that supported the adoption of dispensaries were those that saw the most lost revenue from liquor.

Table 3. Average Liquor Taxes Paid in Year Prior to Adoption of Prohibition

The State Monopoly: Why Only South Carolina?

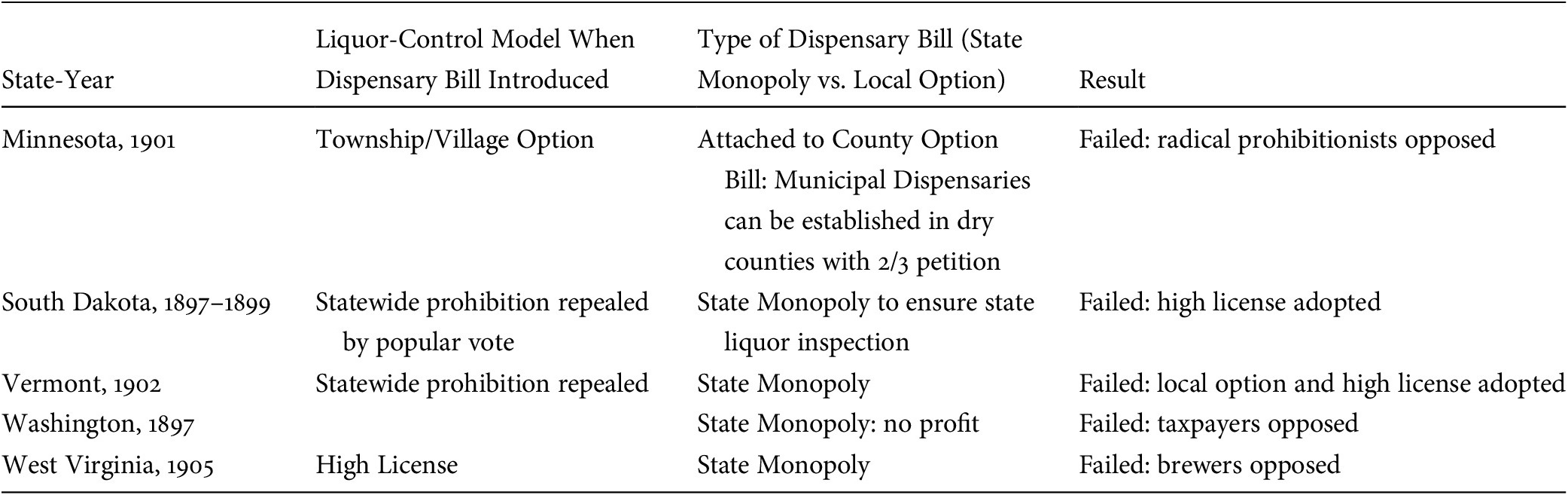

While four southern states were inaugurating municipal dispensaries during the 1890s, outside the South several state legislatures saw bills introduced that would, if adopted, usher in some kind of statewide dispensary system (Table 4). Washington’s proposed dispensary bill did not make it out of committee; however four other states saw bills adopted by at least one part of their legislature.

Table 4. States Considering Dispensary Bills Outside the South, 1897–1905

States Using the Dispensary as a Political Tool (Minnesota and West Virginia)

In two states bills were proposed in which the dispensary was the means to a different political end. In Minnesota, the goal was to split supporters of a proposed county-option bill. Rather than take up the bill directly, language was inserted that allowed “each county in the state the privilege of saying whether it will have saloons or not. In case a county votes not to have saloons upon the petition of 80 percent of the voters of a town in that county a dispensary may be opened.” Thus, antiliquor forces were forced to choose between half a loaf or none. The state Prohibition Party and its supporters chose no loaf, “condemning the dispensary feature… . No body of Christian men should go on record as indorsing the sale of liquor by the government.”Footnote 53 Although the dispensary bill “was opposed by many prohibitionists,” it was “warmly advocated by the Anti-Saloon League. The prohibitionists want strict prohibition. The Anti-Saloon League is willing to take its chance on the county option measure.”Footnote 54

With dry opinion divided on the dispensary feature, wet forces were able to muster enough votes to defeat the county option bill in the Senate. In writing its epitaph, the Prohibition Party newspaper left no doubt as to where the blame for its failure lay: “Those who attached the dispensary feature to the county option idea must bear the responsibility for its death. A large amount of work has been done in the past few years in behalf of a county option law. The Good Templars and the Scandinavian Total Abstinence Association have secured more than 50,000 signatures to petitions for it. But neither they nor the Christian people of the state generally desire that the state shall go into the business of manufacturing drunkards directly. The partnership is already sufficiently close without putting our Commonwealth behind the bar.”Footnote 55

In West Virginia, a state dispensary bill modeled on the South Carolina system was taken up by a legislature for whom “most of the alcohol-related bills … had more to do with … milking the liquor trade for money than with destroying the industry.”Footnote 56 Although “the idea of a dispensary-based regulatory structure had the unique trait of appealing to absolutely no one on either side of the liquor debate,”Footnote 57 West Virginia’s legislators pushed ahead with their plan, at least until the state’s Governor admonished them publicly. “I am not favorably impressed by the practical workings of that system (in South Carolina), nor do I think the time propitious for enacting such radical change in our license system.”Footnote 58 The Governor continued by reading into the public record, the sordid details of the legislative scandal: “I find the following … given the most prominent position in the … Daily Dispatch of Parkersburg, February 13, 1905: “Men in high Official Circles Betray Public Trusts and Sell Their Honor. Liquor Dealers … Produce Money to Defeat Legislation… . Legislators expecting to reap a harvest from the liquor men of West Virginia through the bluff to pass the dispensary bill.” In response, it was said, “saloon men with wallets full of money hurried to Charleston and they spent the cash freely. Of course, the bill was not passed.”Footnote 59

States Repealing Prohibition: South Dakota and Vermont

Two far more legitimate efforts to adopt state dispensaries were undertaken in South Dakota and Vermont. In each case the primary dispensary advocates were the state Anti-Saloon League which saw in the dispensary the best possible fall-back position following the repeal of statewide prohibition. The South Dakota League was the more successful of the two. Following prohibition’s repeal in 1896, the League quickly transitioned to the dispensary as their preferred way forward asserting at their 1897 meeting: “The Anti-Saloon League stands for the utter annihilation of the beverage sale of liquors, but as a step in their direction we favor the dispensary system for legitimate purposes only.”Footnote 60 Throwing their weight behind a state dispensary system, the SDASL was able first to convince lawmakers to place a dispensary amendment in the state constitution subject to voter approval, and then convince voters to approve its enactment in November 1898.Footnote 61

When the state legislature convened in 1899, it did so seemingly with the obligation to enact a dispensary law. Believing this to be mandated, the state anti-saloon league prepared a bill that pushed the envelope as close to prohibition as possible, providing “for but one dispensary in each county and an election must be held before even one dispensary can be established.”Footnote 62 For their part, representatives of the liquor interests tried “to have the legislature resubmit the dispensary amendment without taking other action on the ground that it will cost from $1,000,000 to $2,000,000 to put it into effect, and that the state cannot incur this indebtedness under the constitution.”Footnote 63 The state Senate, seeking a middle ground, passed a bill establishing a state dispensary board and county boards without resorting to a vote first, and leaving manufacturing in private hands. When the Senate bill reached the House, “Rev. Carhart, president and representative of the Anti-Saloon League, appeared before the committee and declared it was unconstitutional to him in its scope and character.”Footnote 64 Apparently the league misjudged the situation, reasoning that the state would eventually have to enact a bill to conform to the vote of the people and therefore assumed that it would be their law that would ultimately prevail. With Anti-Saloon League support removed, however, the liquor interest’s argument of monetary ruin ruled the day. Senate leaders didn’t pass a dispensary bill claiming there would need to be “a direct appropriation from the state to the amount of at least $25,000 to put the law into operation … the state had no fund to be used in executing a dispensary law, because it could not exceed the two mills tax provided in the state constitution.”Footnote 65 Blame for the dispensary bill’s failure was laid at the feet of the SDASL. “These people wanted, not a dispensary, but a prohibition bill,” wrote the Mitchell SD Capital. “But the people did not vote for prohibition, and the state had just emerged from an unsatisfactory experiment with that proposition.”Footnote 66

In Vermont, the catalyst for repeal was an insurgent campaign run from inside the state Republican party. Arguing that “the patronage of prohibition was part of the political machine … since much of the revenue coming into towns and cities was reaped from … dubious penalties and fees,”Footnote 67 Percival Clement, a hotel magnate, sought the governorship on a local-option platform. Clement lost by only three thousand votes, a total close enough to force the new Republican governor, John McCullough, to pronounce “the verdict of the State (is) in favor of … framing a local-option and high license law and submitting the same to the people for their adoption or rejection.”Footnote 68 The Vermont dry forces tried in vain to forestall high license, with “the Anti-Saloon League taking the lead drafting the Battell Bill as a substitute for the license measure.”Footnote 69 Ultimately, the League was unsuccessful.

Setting aside the overtly cynical schemes proposed in Minnesota and West Virginia, it seems as if dispensaries were only meaningfully proposed when dry forces acknowledged prohibition had failed, either at the municipal level across the south or at the state level in South Dakota and Vermont. The dispensaries, it seems, were not preferred by dry campaigners to local option when the momentum was moving forward toward prohibition, but they were preferable when the momentum was moving back toward the saloon.

Standing in stark contrast to the majority of dispensary proposals was the South Carolina experience. In the Palmetto state, the dispensary was adopted not as prohibition was declining in popularity, but shortly after a majority vote supported enacting a statewide dry law. Governor Tillman’s aim in proposing the dispensary system was not to prevent the reemergence of saloons, but rather to prevent the liquor question from dividing white voters and weakening his political coalition.

Further, it cannot be emphasized enough the unusual degree of control Governor Tillman had over the state’s political apparatus. South Carolina’s 1892 legislature was firmly in the control of Tillman’s faction of the state Democratic party, and the Democratic party was the only meaningful one operating in the state. Tillman would need every bit of this legislative control to keep the dispensary system running. A riot in Darlington would force him to call out the state militia to enforce the dispensary law, and when the militia would not respond, Tillman resorted to arming his political supporters in defense of the system. Tillman would also force out a state Supreme Court justice that refused to give legal cover to the dispensary, eventually replacing him with another who would.Footnote 70 It is frankly impossible to imagine most governors with healthy legislative majorities successfully going to such lengths, let along those governors presiding at the head of shaky alliances in South Dakota (where the Populist governor was constantly at odds with the Republican dominated legislature) and Vermont (the Republican party had two distinct factions separated by their position on the liquor question).

The End of the South Carolina Dispensary

Although it remained the only state liquor monopoly, the South Carolina dispensary seemed firmly entrenched, even if its operations looked only vaguely like those originally enshrined into law. Most citizens understood the state was in the liquor business and as with all businesses, certain allowances were necessary to secure a profit. Thus, if a county dispensary did not take the names of its customers, advertised its wares in the local newspaper, or permitted some drinking around the back of its establishment, most citizens were prepared to look the other way if it meant better roads, longer school years, and, most important, less taxes. Of course, there were some prohibitionists who pointed out the folly and moral compromise the dispensary demanded, but most had accepted the dispensary for the business it was—that is, until it became the site of an enormous government scandal.

This chapter in dispensary history has been well documented elsewhere, so I won’t elaborate on it too much here.Footnote 71 The important piece of the story for the larger dispensary movement was that it placed governmental corruption at the center of the dispensary debate. Graft was found to be common throughout the South Carolina system, starting with the Board of Directors, which was charged with certifying the state’s liquor purchases and therefore was often the target of illegal solicitation by liquor dealers. One informer testified that in “the Columbia Hotel, while the state board of control was in session, I saw money change hands between members of the state board and liquor drummers.”Footnote 72 Further revelations included much “Old Joe’ whiske” … bought from an Atlanta concern in carload lots for $36.00 a drum, whereas the same goods were sold in single drum lots to Atlanta saloons for $28.00. Another firm made a “Christmas present” to a member of the board of a carload of very handsome furniture worth about $1,500 ($37,500). Finally, an Augusta brewery, after a long failure to secure orders, put its business in the hands of a friend of one of the dispensary board of directors. At the direction of their representative the brewery raised the price $125 per car, which amount was paid to the agent to be divided, as understood, with the director.”Footnote 73

Local dispensers also encouraged such practices, reminding liquor companies that “if you want the goods sold communicate with the county dispenser of each county and let him know what he may expect, if anything, for special courtesies. It is an old proverb as true as holy writ: ‘Whose bread I eat, whose song I sing. The county dispensers order what they want and sell what they get.’”Footnote 74 Freed from any restraints, liquor dealers favored dispensers with all manner of gifts, as for example this from a Louisville whiskey dealer: “Desiring to contribute something toward good cheer for the holidays … please accept them with the compliments of the season, and in the hope that whenever you partake of these liquors you will give us a kindly thought… . Thanking you for preference shown all our brands.”Footnote 75

As the magnitude of the corruption became public, South Carolinians demanded the state legislature do away with the dispensary. “The opponents of the Dispensary ought to get together,” wrote the Charleston News and Observer as the state began its 1907 legislative session, “and stick together until this blot has been removed from the state. It has … wasted the people’s money.”Footnote 76 Even Ben Tillman, the dispensary’s most ardent champion, admitted defeat. “I am very much disgusted with the present situation in Dispensary matters. If we cannot lift the system to a better level and restore confidence among the people, it is doomed.”Footnote 77

The end came in February 1907, when the South Carolina legislature eliminated the state dispensary system and put in its place a local-option dispensary system. “The chief advantage of their bill,” explained its author Mr. Carey in the Charleston News and Courier, “is its placing the power outside of the hands of the State and under the control of the individual counties… . There is much less opportunity for graft because the counties will overlook the management, and it will be on so much smaller scale that they will be able to do so. It means prohibition where it is wanted, and for the county that desires it will see to it that the law is enforced… . However, where the dispensary is voted in, it will mean revenue to the county, and, for this reason, the county will guard very strictly against blind tigers.”Footnote 78

Essentially what South Carolina had done was copy the formula of its neighboring states, all of which had significant municipal dispensary systems in place. In Georgia, twenty-two of the twenty-nine remaining wet counties were dispensary counties; in Alabama, twenty-six of the forty-three wet counties had dispensaries, and in North Carolina, seventeen of the twenty-six wet counties had dispensaries.

The End of Southern Municipal Dispensaries

Outside South Carolina, the dispensary system’s corruption became another talking point in the push for statewide prohibition in all three states as dry advocates argued the dispensary neither “work(s) for temperance or sobriety,” nor as a money-making scheme since “there was not much money after all the … grafters and not the taxpayers reaped the profits.Footnote 79 One such instance of grafting occurred in Uniontown, Alabama, where an investigation has been brought about by the annual report of the dispensary at Marion. The yearly report of the Marion dispensary showed that it had done $39,000 worth of business during the year and that the profits to the city of Marion were something like $13,000. This report caused the citizens of Uniontown to inquire what profits that city had derived from the dispensary. The yearly report of the Uniontown dispensary showed that sales for the past year had amounted to $52,000. This report further showed that of this amount the city of Uniontown had been paid about $5,000. It is believed that the people of Uniontown and Perry County will ask for the holding of an election to vote upon local option. If this election is held it is almost certain that Perry County will go for prohibition.Footnote 80

Even in cases where outright fraud was not evident, observers became quick to blame liquor boards for using their positions to influence voters: “At the regular monthly meeting of the (Union Springs, Alabama) City Council an ordinance was passed appropriating 40 percent of the profits of the dispensary to the county for the improvement of the roads. This action on the part of the Council was the result of the prohibition fight now on in the county, and it is thought by many to have been done to try to influence some of the country voters, the majority of whom are conceded to be for prohibition.”Footnote 81

Dispensary corruption claims were important in that they provided further evidence in support of one of southern dry’s arguments against liquor.Footnote 82 Equating the dispensaries’ political influence with that already evident in the saloon, dry activists argued that each was an inevitable extension of a “huge political machine” Footnote 83 that “cursed and blighted the great commonwealth.”Footnote 84 To rid themselves of the hold of the liquor trust, dry activists argued for a “bold, fearless stand taken for state prohibition,”Footnote 85 which would eliminate both saloons and dispensaries once and for all.

In advocating for statewide prohibition, dry activists essentially did an end run around the municipal dispensary movement. Seeking less to change opinions in the many towns in which local dispensaries still had a good deal of support, instead prohibitionists sought to martial votes against all forms of the liquor traffic at the state level and leverage these against those places that permitted liquor sales but were in the minority. You can see the results of this effort in comparing the vote totals of citizens and their representatives in state legislatures, as statewide prohibition was enacted, first in Georgia and Alabama in 1907, then in North Carolina the following year (Table 5). In each state, dispensary counties gave at best lukewarm support to statewide prohibition, a level far below their counterparts in already dry counties.

Table 5. Support for Statewide Prohibition

North Carolina held a prohibition election in 1908. Georgia and Alabama enacted statewide prohibition in 1907 through a vote of the state legislature.

Following the adoption of prohibition in Georgia, North Carolina, and Alabama, the dispensary lived on as a local concern in both South Carolina and Virginia, where a few counties kept stores, mostly those along state borders that could take advantage of their newly dry neighbors.Footnote 86 Oklahoma briefly attempted to revive the idea, establishing a statewide medicinal dispensary system after voters had adopted a state constitution that enshrined prohibition. Upon its adoption, Oklahoma Governor Charles N. Haskell was clear to draw a distinction between Oklahoma’s liquor stores and those recently closed in South Carolina. “We call our system dispensary because we couldn’t think of another word. ‘Medicinal’ would describe it better. We don’t even sell liquor in drug stores and the bottles for a town of five thousand wouldn’t half fill an ordinary bookcase. Practical! That’s what the Oklahoma system is.”Footnote 87 Haskell’s practical system closed two years later, amid charges of graft and corruption.Footnote 88 Its end marked the final curtain call for the country’s first dalliance with the dispensary.

Conclusion

I say “first” because following the repeal of federal prohibition, the political pressure of the proliquor lobby, the increasing belief that prohibition did not prohibit, and the need for greater federal, state, and local taxes that liquor sales could provide led to the readoption of state liquor stores in many states, a system persists to the present day.Footnote 89 In this postwar period the municipal option that had spawned the initial dispensary movement was no longer available as liquor control was left in the hands of the states in the hopes of preventing the reemergence of saloons to once again nurture urban political machines. Ironically, then, it was the outlier of the first dispensary movement—the South Carolina state dispensary—that became the closest United States approximation of the second.

Critics of national prohibition echoed arguments of municipal dispensary supporters from the earlier generation when they pointed out that the federal law was unenforceable, an enormous financial drain in lost tax revenues, and led to a “widespread and scarcely or not at all concealed contempt for the policy of the National Prohibition Act.”Footnote 90 Upon repeal, the most prominent source of liquor policy going forward was John D. Rockefeller Jr., a self-described teetotaler who supported the Anti-Saloon League in both state and national work. As Rockefeller came to the realization that the evils brought by prohibition outweighed its benefits, he determined to “undertake through various competent associates a thorough and complete study of the various methods which have been tried … looking toward the control of the use of alcoholic beverages … giving the points in favor of and against each method.”Footnote 91

The result was Towards Liquor Control, a volume that argued for each state to take over as a public monopoly the retail sale for off-premises consumption of spirits, fortified wine, and beer above 3.2 percent alcohol. Along with an analysis of the monopoly system’s proposed benefits, the book also included a text of a model law should states wish to enact it. This law was also pushed during meetings of the National Municipal League and eventually published in the National Municipal Review in January 1934. Levine (1985) describes what happened next: “State legislators faced with difficult political choices, and with little personal experience in the subtle question of liquor regulation, turned to the authoritative and virtually unchallenged plans of the Rockefeller commission and National Municipal League… .The monopoly law was taken almost verbatim by fifteen states.”Footnote 92

The adoption of state liquor monopolies by fifteen states meant that the majority of states instead settled on private sales with license fees. While determining the distinguishing factors between states that supported monopolies and those that did not is beyond the scope of this article, the current study offers a potential way forward in that effort—namely, studying the role played by temperance organizations and lost liquor revenue to assess the role they played in bringing about postrepeal outcomes.

One commonality across the two eras is that both periods saw a turn toward the dispensary/monopoly model as a response to prohibition’s demise. This insight is often lost in histories that center prohibition’s triumph because they often conclude with state or national prohibition. This makes it seem as if dispensaries came before prohibition, when in fact the typical order of anti-alcohol legislation seems to have been a local option leading to prohibition, which then led to the dispensary or state monopoly. Further, the dispensary option seems quite a bit more durable than its more exciting alternative of prohibition. Municipal dispensaries were rarely eliminated prior to the development of state prohibition, and the majority of state monopoly regimes put in place following national repeal remain in place today almost eighty-five years later.

Looking beyond liquor, it will be interesting to watch the unfolding and long-term future of dispensaries as the primary method of marijuana legalization. It is of course possible that marijuana, a drug that has never had the cultural acceptance that liquor attained, will see its legal status rolled back over time. The above analysis suggests that it is possible for dispensaries to be seen as providing both enough control and enough profits to hit the sweet spot, regardless of our attitudes toward the substance in question. Regardless of the outcome, this suggests that policy scholars will continue to pay close attention to dispensaries in the future.