Sometime near the end of 1950, when Morton Feldman and John Cage lived in the same apartment building on New York's Lower East Side, the twenty-four-year-old Feldman paid a visit to his friend's top-floor loft. Famously, the two composers had built a rapport the previous winter after encountering one another at a performance of Webern's Op. 21 by the New York Philharmonic, each fleeing the scene as Webern's music gave way to Rachmaninoff; their professional relationship grew stronger in the months thereafter, leading Feldman to rent an apartment on the second floor of Cage's tenement. Although his productivity had flagged since the start of their friendship, Feldman experienced an epiphany on that evening in late 1950 that shaped the course of his emergent career while opening new avenues for those around him. Accounts of the event differ in detail, but all agree in one respect: at some point, he walked to a different room of Cage's apartment and sketched a passage of music in a spontaneously devised style of graphic notation.Footnote 1 He soon harnessed the notation to compose a series of works entitled Projections (1950–51), the earliest known graphic scores to emerge from the postwar avant-garde.Footnote 2

The Projections would help to launch a vast repertory of experimental music distinguished by the latitude it offered performers in shaping the sonic realization of notated scores. Described in later years with marked terms such as “indeterminate,” “aleatoric,” and “improvisatory,” that repertory comprised works as different in character, ideology, and philosophical orientation as the individuals who set them onto paper. In fact, disagreements and misunderstandings animated the postwar development of experimental notation from the start. Before the ink was dry on Feldman's graph, Cage began to promote his friend's new notation in the language of his own philosophy of non-intention, a nascent framework of thought with which the Projections bear a complex and puzzling relationship. Although Cage's emerging ideas on chance were largely incompatible with Feldman's artistic outlook, the striking leeway the Projections offered to performers may have helped to inspire Cage's budding doctrine, if inadvertently. Feldman chose to align the Projections instead with abstract expressionism, an art whose creative paradigm of subjective engagement stood at odds with the Zen-inspired philosophy of aesthetic detachment promoted by his better-known colleague. Yet the forces influencing his graphic notation were still more diverse, for they included Edgard Varèse and Stefan Wolpe, older figures who loomed large over his maturation as a composer. Attributable neither to a single act of appropriation nor to one of solitary invention, his new notation emerged instead from the transformation and creative synthesis of many ideas circulated by older modernist artists in his milieu.

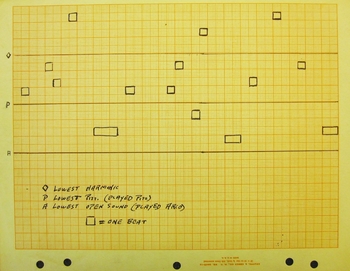

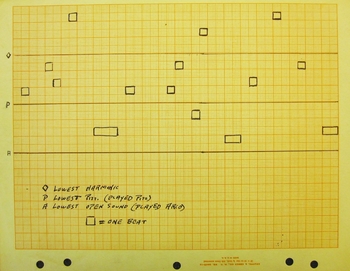

Reversing the historical tendency toward ever-greater specificity in musical notation, Feldman designed the Projections within a framework that hindered, rather than strengthened, his ability to specify compositional details with the nuance of a composer writing in conventional notation. The sketch shown in Example 1 offers a glimpse of his new notation in what appears to be an embryonic stage.Footnote 3 Now housed among the papers of the late pianist David Tudor, the close friend and collaborator of both Feldman and Cage, this page suggests a kinship with the first work of the Projections, a piece scored for solo cello.Footnote 4 Although its notational design is inchoate in comparison with the works that followed, the sketch demonstrates the kernel of Feldman's new idea. Time, measured on the horizontal axis, is parceled out with some measure of control; pitch, however, is indicated only in relative terms above a line corresponding to the player's lowest available sound. Compare the sketch to Example 2, which shows the first page of Projection 1, its apparent offspring.

Example 1. Feldman, undated sketch. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (980039). Used by permission of C. F. Peters Corporation and the Morton Feldman Estate.

Example 2. Feldman, Projection 1 (1950), 1. Copyright © 1962 by C. F. Peters Corporation. Used by permission.

Here, a crude form of meter has emerged. Each square on the grid still corresponds to one “beat” (or, as Feldman would write in the work's performance instructions, one “ictus or pulse”), but these beats are now grouped into collections of four, akin to measures in common time.Footnote 5 Pitch in Example 2 remains largely unspecified, as it does in Example 1, but now the vertical space within each large box is divided into three bands, corresponding respectively to a performer's high, medium, and low registers, leaving the player free to select any note within the register indicated. Feldman would ultimately change his means of designating articulation across the various works of the Projection series, but Projection 1 approaches the matter as the sketch in Example 1 does, with separate strata in the score denoting whether sounds should be articulated via pizzicato (P), arco (A), or harmonics (◊).

Feldman's breakthrough with graphic notation and subsequent completion of his Composition for Cello (Projection 1)—as the first work of the series was initially titled in manuscript—likely transpired in December of 1950. Yet no primary source can confirm the date of either event with precision. Although they could have occurred in close succession, an equally plausible scenario has the composer laying aside his initial sketch and only later reworking it into final form. Thanks to an important piece of correspondence, however, the chronology of events that followed the composition of Projection 1 is quite clear, even if those same events would render the rationale behind Feldman's notation increasingly opaque.

Cage “Broadcasts His Faith”

After Feldman had written Projections 2–4 during the first half of January 1951, Cage began to promote the pieces, introducing audiences and critics to the music while creating the impression that a coterie of younger composers stood in his shadow, sharing in his artistic ethos. A revealing letter from Cage to Tudor provides a snapshot of these promotional efforts as they were unfolding. Referring to his conversations with three influential tastemakers of the early 1950s—the critics Virgil Thomson, Arthur Berger, and Minna Lederman—Cage wrote,

Virgil tells me that he's not convinced about Morty, that he is too much the ‘anointed one’ (oil dripping off his shoulders). However, I'm more or less generally broadcasting my faith in his work and to the point of fanaticism. I spent a troublesome hour & ½ arguing with Arthur Berger re: Morty's and Xian's [Christian Wolff's] music because Arthur has to review the concert next Sunday. And then another hour with Minna Lederman, who began to take the music more seriously when I explained Suzuki's identification of subject and object vs. the usual cause and effect thought. She even invited me to dinner to talk further.Footnote 6

A charming and persuasive speaker, Cage met with some measure of success in these endeavors, or so his experience with Lederman suggests.Footnote 7 But how accurate was his representation of Feldman's music? The question requires an examination of the shared ideals that drew these two figures together at the outset of the 1950s as they bonded over their mutual enthusiasm for Webern and the radical vistas his music opened for them.

In the earliest year of the friendship, Cage and Feldman each harbored dreams of a new music freed from the past, a quixotic vision soon to be shared by many of their contemporaries in the European avant-garde. Questions over the nature of musical continuity held particular interest for both composers even before the start of their friendship. For example, Feldman's composition teacher of the mid to late 1940s, Stefan Wolpe, accused him of willfully “negating” his musical ideas rather than developing them, thereby sabotaging the rhetorical basis of his work's continuity in time.Footnote 8 With this in mind one might imagine the specific appeal that Webern's symphony held for Feldman upon his exposure to the piece, its fractured Klangfarbenmelodie offering a radically new, anti-thematic treatment of the sonic continuum. Likewise, Cage had been concerned with the nature of musical continuity immediately prior to meeting Feldman; in composing the first movement (1949) of his String Quartet in Four Parts, for example, he intentionally treated harmonies as static, non-contingent entities.Footnote 9 Yet Cage's growing resistance to musical rhetoric and teleology was linked to another, more famous trajectory in his development: his incremental abandonment, since the mid-1940s, of an aesthetic grounded in subjective expression and gradual turn toward one rooted instead in the values of emotional detachment and psychological quiescence. Important here are the words “incremental” and “gradual,” for many of the stylistic traits apparent in Cage's music during 1949 and 1950 prefigure those in his later body of chance music. Yet the Cage whom Feldman visited on that winter night in late 1950 had not fully accepted non-intention as an artistic paradigm, a conceptual development that would be accompanied by his adoption of the I Ching as a compositional tool between 21 January and 9 February 1951.Footnote 10 In fact, according to Cage's later remarks on the subject, Feldman's Projections helped to spur that adoption.Footnote 11

It was just prior to that moment that Cage wrote the aforementioned letter to Tudor detailing his behind-the-scenes politicking on behalf of the Projections.Footnote 12 Even at this juncture, he had begun to interpret Feldman's new notation in the context of Zen Buddhism: Lederman, he indicated, became more receptive to Feldman's music when its absence of conventional rhetoric (“the usual cause and effect thought”) was explained with recourse to the philosophy of Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, the great exponent of Zen whose writings had occupied Cage's thought during the preceding year. Such references to Eastern philosophy were further integrated into Cage's discourse after he fully embraced the role of chance in composition and began to publicly promote his new vision of a music stripped of ego, will, and agency. In so doing, he continued to draw upon Feldman's graph to make his case. This process is captured vividly in the first public talk he is known to have given after his turn to chance, the “Lecture on Something,” which was delivered at the Artists’ Club at 39 East Eighth Street on 9 February 1951.Footnote 13

The talk's outward subject was, in fact, Feldman. Cage spoke of his friend's willingness, via graphic notation, to passively “accept” sounds arising in performance rather than to script every note on the page:

Feldman . . . takes within broad limits the first [sounds] that come along. He has changed the responsibility of the composer from making to accepting. To accept whatever comes regardless of the consequences is to be unafraid or to be full of that love which comes from a sense of at-one-ness with whatever.Footnote 14

Such a reading of Feldman's music implied something more than an indiscriminate attitude toward musical continuity, however; it suggested a silencing of the self. Because the graphically scored works were shaped in part by outside actors whose choices the composer ostensibly accepted, they stood for Cage as a perfect demonstration of the interpenetration of art and life.Footnote 15 Cage even extended Feldman's purported “acceptance” of outside sounds to include extraneous noises:

[A]t the root of the desire to appreciate a piece of music, to call it this rather than that, to hear it without the unavoidable extraneous sounds—at the root of all this is the idea that this work is a thing separate from the rest of life, which is not the case with Feldman's music.Footnote 16

But had Feldman himself actually endorsed the state of aesthetic impartiality, the “at-one-ness with whatever,” claimed for him by Cage? Had their mutual quest for new sonic continuities truly morphed, for Feldman, into an attitude of catholic “acceptance” regarding all sonic content? And was the unusual notation of the Projections—their openness toward pitch, in particular—conceived in this spirit?

Most evidence suggests the contrary. In numerous essays and print interviews dating from the latter 1950s until his death, Feldman expounded upon his own conviction in an art grounded in the subjectivity of its creator, and in so doing articulated his implicit rejection of chance as a musico-philosophical doctrine.Footnote 17 In a revealing letter of 1975, he wrote that his graphically notated music of the early 1950s “on its own terms controlled the ‘experience’”—a decidedly un-Cagean phrase emphasizing the retention, not repudiation, of compositional authority and intent.Footnote 18 Even if the notation of such pieces allotted performers certain discretion in shaping the realization of the works, Feldman implied that it nevertheless permitted the composer to direct the listener's “experience” just as if the music had been written in conventional notation. The compositional means by which that control was exerted—the notation's specific “terms”—were simply different.

Feldman, however, was less forthcoming about his intentions at the start of his career, and the only major lecture he is known to have given during the era has not survived. The testimony of others nevertheless supports his later assertion that he disagreed with Cage's philosophy of non-intention from the outset. Christian Wolff, who took informal composition lessons from Cage at the time Feldman was writing his Projections and Intersections, has in years since recalled “expression” and “intuition” as being components of Feldman's early aesthetic.Footnote 19 Likewise, Henry Cowell's 1952 profile of the emergent New York School identifies Feldman as “more subjective” in his aesthetic orientation than the others.Footnote 20 Ironically, it was Cage himself who best revealed the disjuncture between the caricature he drew in the “Lecture on Something” and Feldman's own understanding of his graphic notation. When Cage produced a print version of the lecture for publication in 1959, he prefaced the text with a telling anecdote: “In the general moving around and talking that followed my Lecture on Something (ten years ago at the Club), somebody asked Morton Feldman whether he agreed with what I had said about him. He replied, ‘That's not me; that's John’.”Footnote 21

In light of the scarcity of sources documenting Feldman's attitudes about his Projections at the time he composed them, this pithy rejoinder of 1951 speaks volumes. Having conceived his first graphic works before, not after, Cage's full embrace of chance, Feldman was likely driven by goals of an essentially stylistic nature. Chief among these was his need to enact new and unheard sonic “continuities” by eschewing familiar musical relationships, and especially those patterns of pitch inscribed to his memory by the force of habit. Although long identified as a foundational principle linking the composers of the New York School at the outset of their affiliation, this effort to rid music of familiar continuities was not, however, coterminous with the essentially philosophical doctrine of Cagean non-intention.Footnote 22 Yet its capacity to serve such an end, recognized by Cage from the start, raises a valuable question. Having removed pitch from the calculus of composition, how could Feldman subsequently claim to “control the experience” of his music? The answer resides not the notation's limitations, but in its strengths, including the new feeling for musical space it engendered in the composer.

Varèse, Wolpe, and Musical Space

Despite Cage's close association with Feldman in the public eye, other role models in the budding composer's life may have exerted greater influence over his turn toward graphic notation. The first of these was Edgard Varèse, whom he met while studying with Stefan Wolpe during the 1940s. Although he never took formal composition lessons with Varèse, Feldman came to view the expatriate Frenchman as his greatest musical mentor.Footnote 23 In the formative years of Feldman's aesthetic development, Varèse's distinctively spatialized conception of musical composition and concomitant interest in graphic notation appear to have left a strong mark on the young composer.

Evidence of that influence is apparent in the title Feldman assigned to his new works, for “projection” was a term at the core of Varèse's musical thought.Footnote 24 Tellingly, however, Feldman never drew attention to this bit of shared terminology in print. In Varèse's usage, “projection” was a fluid concept that functioned on both literal and figurative levels.Footnote 25 Literally, the term denoted the physical conveyance of sound in space, the process of its transmission outward from a vibrating source. Convinced that this acoustical phenomenon constituted an essential, if neglected, aspect of musical experience, he alluded to it often in his lectures and writings. Most famously, he recalled his youthful exposure to Beethoven's Seventh Symphony at the Salle Pleyel in Paris:

Probably because the hall happened to be over-resonant . . . I became conscious of an entirely new effect produced by this familiar music. I seemed to feel the music detaching itself and projecting itself into space.Footnote 26

Throughout his career, Feldman displayed a closely related concern with the acoustical decay of musical sound, a concern apparently piqued by his early exposure to Varèse's notion of projection. He recalled an impromptu exchange on the street during the 1940s in which the older composer offered a piece of cryptic advice, telling him to be mindful of the time required for sound to travel from the concert stage to the audience. It was a transformative moment for Feldman, awakening him to what he would elsewhere characterize as the “acoustical reality” of music. “From then on,” he recalled, “I started to listen.”Footnote 27

Feldman, like Varèse, spoke of his music in evocative, if imprecise terms, and his rhetorical style was likewise defined by a strain of idiosyncratic spatial metaphors. For Varèse, the acoustical experience of projection produced a sensation of sound “leaving us with no hope of being reflected back,” an impression “akin to that aroused by beams of light sent forth by a powerful searchlight.”Footnote 28 Compare these words to Feldman's description of acoustical decay as a “departing landscape,” the sensation of sounds “leaving us rather than coming toward us.”Footnote 29 We should bear in mind these rhetorical parallels when considering the “Lecture on Something,” for in that talk Cage informs us that Feldman spoke not of “sounds” in his graph music but instead, enigmatically, of “shadows”—a visual metaphor of departure and absence, or projection into space.Footnote 30 The quality of sonic departure and decay indeed pervades Feldman's works of 1950, which are more texturally sparse than those of the late 1940s. Bracketed by periods of silence, his sounds are often provided ample time to “project,” their decay stretching like shadows across voids that sometimes span entire measures.

For Varèse, however, the term projection carried shades of meaning beyond the one explored above, for it also spoke to the abstract relationship among sounds in a compositional framework. Just as the materials of music are projected acoustically in the space of a concert hall, they are also projected compositionally within the vertical and horizontal space of a score. In this figurative sense, the term resonates with other action-oriented words in Varèse's prose meant to convey the dynamic interplay of his materials as entities in a compositional arena.Footnote 31 Despite the vagaries embedded in its design—or perhaps because of them—Feldman's new notation drew his attention to the spatiality of that arena, laying out before the composer's eyes the shape of his materials in a more explicit manner than conventional notation could allow. Through his experience with the Projections his creative method would grow increasingly oriented toward visual experience.

In the months immediately before Feldman composed the works, Varèse had been lecturing in Germany. Upon his return to the United States, he was invited to speak before the Artists’ Club, the same venue where Cage would deliver the “Lecture on Something” a few months later. Long drawn to the visual arts, Varèse obliged, and in November 1950 spoke to a crowd so large and enthusiastic that some of the painters in attendance grew concerned about the structural integrity of the loft that housed the meeting.Footnote 32 His talk carried the same title as his recent lectures in Frankfurt, Berlin, and Munich: “Music, an Art-Science.”Footnote 33

One would expect that Feldman witnessed the event, and oral history thankfully confirms the fact: in a 1988 interview with Olivia Mattis, Cage recalled that he, Feldman, and Wolpe together attended Varèse's lecture at the Artists’ Club.Footnote 34 There they had the opportunity to hear the older composer speak on his notion of sound projection, including his youthful discovery of the concept at the Salle Pleyel.Footnote 35 Moreover, the lecture included a plea for the development of “new notation” to serve the needs of a technologically enriched music.Footnote 36 In his other talks and essays, Varèse sometimes went so far as to characterize this new notation as being specifically “graphic” in character. For example, in an earlier lecture of 1936 he remarked:

And here it is curious to note that at the beginning of two eras, the Mediaeval primitive and our own primitive era (for we are at a new primitive stage in music today), we are faced with an identical problem: the problem of finding graphic symbols for the transposition of the composer's thought into sound.Footnote 37

Such references to graphic notation in Varèse's lectures were typically couched in the future tense and tethered to his long-standing wish to compose electronic music, a wish soon to be realized in the tape interpolations (1952–54) for Déserts. Although it remains unclear whether Varèse drew upon graphic sketches in conceiving of that specific work, his use of such notation in representing the later Poème électronique (1957–58) is well documented.Footnote 38 Feldman appears to have taken his mentor's advice in a different direction, producing the postwar avant-garde's first-known graphic scores intended for use in performance by instrumentalists. Was Varèse's lecture the prompt? Alongside Feldman's appropriation of the term “projection” as the title for his new series of works, the timing of his turn toward graphic notation offers compelling, if inconclusive, evidence.

It is appropriate that Feldman's introduction to Varèse should have come through the hands of his teacher, Wolpe, for Varèse and Wolpe shared much in common.Footnote 39 This was particularly the case after the latter settled in New York City in 1938 and began to deploy chromatic pitch collections within what he called “constellatory space,” drawing upon principles of symmetry and asymmetry.Footnote 40 During the 1940s, when Feldman studied with him, Wolpe's agenda was “to break up hierarchical, thematic space, and create a mobile, permeable, open space in which a variety of shapes and actions can move freely,” according to Austin Clarkson.Footnote 41 Apart from his contact with Varèse, then, Feldman surely had ample opportunities to discuss the spatialization of sound in composition lessons with Wolpe during the period preceding his epiphany regarding graphic notation.

Despite the commonalities between Wolpe and Varèse, Feldman responded in different ways to each, publicly professing his admiration of Varèse throughout his career while conveying ambivalence toward Wolpe. To be sure, he valued his former teacher's fluid notion of “shape” in music, a concept he later found useful in describing the character of a given gesture or harmonic voicing.Footnote 42 To Wolpe, however, such shapes existed in a dialectical relationship with one another in the musical continuum, their interaction ultimately generating both conflict and coherence. It was his commitment to the idea of dialectical renewal that led Wolpe to object to Feldman's music during his composition lessons of the 1940s, precipitating their frequent arguments.Footnote 43 Although he juxtaposed unlike musical materials in his own work, Feldman had little interest in using these oppositions in the manner his teacher prescribed. As a result, Wolpe criticized his musical approach as one of “negation” alone.Footnote 44 Feldman embraced this assessment: “I learned for myself how to do without synthesis,” he later wrote, “without the whole idea of ‘unified opposites’.”Footnote 45 In this respect, he saw an ally in Varèse, whose conception of form and syntax—insofar as Feldman grasped it—could not be contained within the dialectical models Wolpe preached. By the 1960s, Feldman would define his own aesthetics of time and space in contradistinction to the terms “dialectical” and “rhetorical” in numerous essays and interviews.Footnote 46

Ironically, however, Wolpe's methods served as a powerful influence on Feldman, if by way of negative example. They may, in fact, have helped to spur his development of graphic notation. In an essay written late in his life, Feldman explained how his teacher's love of binary logic filtered into his own musical thought. But whereas Wolpe concerned himself with the dialectical synthesis or reconciliation of opposites, Feldman treated them as “hurdles” or “obstacles to be jumped.” In a startling passage, he wrote:

I took this overall concept with me in to my own music soon after finishing my studies with Wolpe. It was the basis of my graph music. For example: the time is given but not the pitch. Or, the pitch is given but not the rhythm. Or, in earlier notated pieces of mine the appearance of octaves and tonal intervals out of context to the overall harmonic language. I didn't exactly think of this as opposites—but Wolpe taught me to look on the other side of the coin.Footnote 47

The passage suggests that Feldman's interest in the juxtaposition of unlike material during his student years was at once an offshoot of Wolpe's dialectics and also a corruption of it.Footnote 48 Moreover, the statement affirms that the notational design of the Projections (“the time is given but not the pitch”) and the format of Feldman's later free-duration music (“the pitch is given but not the rhythm”) are indebted to the same mode of thought. Faced with a compositional barrier, he chose not to wrestle with the problem in the course of composing his music, as his teacher might have, but rather to “jump the obstacle” entirely. In the case of the graph works, Feldman sought to escape the rhetorical implications of pitch relations (his “obstacle”) by eliminating them as a compositional concern, looking instead to the “opposite side of the coin”: a music defined foremost by timbre and texture.Footnote 49

Wolpe was not merely Feldman's teacher during the 1940s, but the hub of his musical life.Footnote 50 It was he who introduced Feldman to Varèse, and in all likelihood he who stoked Feldman's enthusiasm for Webern; indeed, Wolpe himself had studied with Webern a little more than a decade before taking on Feldman as a student. Furthermore, when Feldman attended Mitropoulos's performance of Webern's Op. 21 in January 1950 and bumped into John Cage, it was not the first time their paths had crossed: Cage had previously attended one of the informal gatherings held by Wolpe and his wife Irma for their students at their Cathedral Parkway home.Footnote 51 It stands to reason that the music and thought of all four of these composers—Wolpe, Webern, Varèse, and Cage—helped to shape Feldman's conception of the Projections. In the music of Webern, he was exposed to a fragmentary, non-thematic treatment of musical continuity, a delicacy of timbre, a sparseness of texture, and a pervasive pianissimo, all qualities he would adopt in several works composed during 1950 and 1951. Through Wolpe's tutelage, he was encouraged to think in terms of dialectical oppositions, a framework that led him inadvertently to conceive of a notational format in which pitch logic is removed from the terms of composition. Varèse fostered his appreciation of the phenomenon of “projection” and, with it, his recognition of the value inherent in sound-qua-sound, apart from its utility in building musical arguments. Varèse and Wolpe moreover shared a spatialized conception of music in keeping with the one Feldman himself would cultivate through the Projections, with Varèse even going so far as to proselytize on behalf of graphic notation. And what of Cage? Despite his subsequent misinterpretation of Feldman's graphic works, Cage's enthusiastic presence in his friend's life in 1950 no doubt fostered an atmosphere conducive to radical experimentation, as both composers sought out new methods to subvert old continuities, musically and historically.

Feldman Reclaims the Narrative

Soon after harnessing the I Ching to compose works in fixed notation, Cage began to produce music that was, in his famous formulation, “indeterminate with respect to its performance,” a conceptual orientation that offered him an alternate route to the goal of non-intention. The first of these indeterminate works, 1951's Imaginary Landscape No. 4 for twelve radios, was dedicated to Feldman.Footnote 52 If Feldman had unwittingly assisted his friend's philosophical transition to non-intention through his proto-indeterminate Projections, it was nevertheless Cage's philosophical notion of indeterminacy, not his younger colleague's aesthetic view, that received the greatest public exposure thereafter. Perhaps for that reason Feldman sought to reframe the story of his music's genesis and meaning in a set of LP liner notes written in 1962, twelve years after the Projections were conceived. In that text, he linked the Projections not with Cage's Zen-inspired poetics of aesthetic detachment but rather with the model of willful, creative action provided by what he termed “the new painting.”Footnote 53 The essay marked his earliest attempt in print to draw attention to the role of abstract expressionism as a model for his musical aesthetics and methods.Footnote 54

Feldman's comments on the Projections merit quoting in full:

The new painting made me desirous of a sound world more direct, more immediate, more physical than anything that had existed heretofore. Varèse had elements of this. But he was too “Varèse.” Webern had glimpses of it. But his work was too involved with the disciplines of the twelve-tone system. The new structure required a concentration more demanding than if the technique were that of still photography, which for me is what precise notation has come to imply.

Projection II for flute, trumpet, violin and cello—one of the first graph pieces—was my first experience with this new thought. My desire here was not to “compose,” but to project sounds into time, free from a compositional rhetoric that had no place here. In order not to involve the performer (i.e., myself) in memory (relationships), and because the sounds no longer had an inherent symbolic shape, I allowed for indeterminacies with regard to pitch.Footnote 55

Feldman's striking claim to cross-disciplinary influence from visual art overshadows his careful, but terse, dismissal of the musical role models most important to his maturation as a young composer. Varèse, he acknowledges, possessed “elements” of the “new sound world” that he sought in composing the Projections, but his music is brushed aside for being too personal or idiosyncratic—that is, “too ‘Varèse.’”Footnote 56 The remark is curious in light of the provenance of the term “projection,” a word Feldman deployed in this very same statement to define the raison d’être of his own works (“to project sounds into time. . .”). Webern had “glimpses” of this imagined sound ideal, Feldman tells us, but his music was hamstrung by its methodological rigor (“the disciplines of the twelve-tone system”). In a biographical précis preceding the passage quoted above, Feldman cites Wolpe, too, but gives him none of the credit he would allot to him later in life. “All we did was argue about music,” he recalls of his lessons, “and I felt I was learning nothing.” Indeed, the negative references to musical “rhetoric” and “relationships” in the quoted passage strike to the heart of their differences.

In the same statement, Feldman also addressed Cage's presence in his life at the time the Projections were composed, reflecting on the asymmetry that defined their early relationship. After describing Cage's expansive top-floor loft (a space affording “a magnificent view”), Feldman wrote, “I too moved into that magic house, except that I was on the second floor, and with just a glimpse of the East River. I was very aware at the time of how symbolically I felt that fact.”Footnote 57 He credited Cage with providing him with much needed “appreciation and encouragement,” but reminded readers that the source of his creativity resided in his own intuition, not the influence of others: “I sometimes wonder how my music would have turned out,” he wrote, “if John had not given me those early permissions to have confidence in my instincts.” In fact, Feldman explicitly downplayed the possibility that any meaningful musical exchanges transpired with Cage, instead directing attention to the formative role of visual art:

There was very little talk about music with John. Things were moving too fast to even talk about it. But there was an incredible amount of talk about painting. John and I would drop in at the Cedar Bar at six in the afternoon and talk with artist friends until three in the morning, when it closed. I can say without exaggeration that we did this every day for five years of our lives.Footnote 58

To the contrary, Feldman was exaggerating with this claim, and in more than one respect.Footnote 59 Justifiably eager to disentangle his work from his friend's Zen-influenced interpretations, he had begun a process of disowning the very possibility of Cage's influence while aligning his music instead with the discourse associated with abstract expressionist painting. In subsequent years he would rail against the notion that Cage had shaped the direction of his music in 1950, insisting, “my music didn't change when I met Cage, in fact it's the opposite: his music changed when he met me.”Footnote 60 More accurate still is the proposition that these two composers changed each other, if in ways that resist easy summary.

Although Feldman's ambivalence toward his friend may have been well founded, some of his subsequent efforts to assert his creative autonomy were misleading. Despite the abundance of evidence proving that he composed the Projections nearly a year after his association with Cage began, he made a forthright claim for the opposite order of events in an interview of 1973. He recounted,

In the Winter of 1950 I went to Carnegie Hall to hear Mitropoulos conduct the New York Philharmonic in the Webern Opus 21 . . . I'd already composed my graph pieces, the first of their kind, but I was vastly unknown. . . . At intermission I went out to the inner lobby by the staircase, and there was John Cage.Footnote 61

The claim reads less like a slip of memory than an ill-conceived exercise in biographical revisionism aimed to assert his independence from a better-known colleague.

Painting and Feldman's “Abstract Sonic Adventure”

Feldman's willingness to take liberties with the historical record might raise doubts about the veracity of his other claims regarding the Projections, including his testimony about the importance of “the new painting” to his conception of those works. By drawing attention to visual art as the key source of his inspiration, was he merely diverting attention from the musical figures looming over his development at the time he conceived his graphically notated music? In fact, by examining his words carefully we can see that he never claimed painting as an influence on the genesis of his graphic notation or on the series of Projections as a whole. As his 1962 liner notes indicate, it was Projection 2, not Projection 1, that marked his “first experience” with a conception of musical composition modeled upon visual art. Indeed, evidence hints that Projection 2 signaled a new beginning for Feldman. In the collection of his manuscripts at the Paul Sacher Foundation, all five works of the Projection series are preserved in neat copies within a small notebook of graph paper where the composer apparently transferred them after drafting them elsewhere. Yet Projection 2 does not begin on the page following the first work. Instead, it appears upside down at the notebook's opposite end, which can thereby serve as the book's front; the remaining Projections then follow in order.Footnote 62 Scored for a mixed quintet of flute, trumpet, violin, cello, and piano, Projection 2 marked the start of Feldman's engagement with graphic notation as a means to control ensemble texture and timbre on a global level, and as a result the work's style is noticeably different from that of Projection 1, scored for solo cello. It stands to reason that this change in instrumentation itself may have pushed him to conceive of the graph format anew in terms of painting.

Other evidence clearly confirms that Feldman had begun to draw parallels between musical composition and painting at least as early as 2 February 1951, a month after he composed Projection 2. It was on that date—a week before Cage would deliver the “Lecture on Something”—that Feldman himself spoke before the assembled painters at the Artists’ Club, giving a talk entitled “The Unframed Frame.” Although the text of the lecture has not survived, the few available clues regarding its content are illuminating. Brief notes written in a private journal by the club's founder, Philip Pavia, record the following message from Feldman's lecture: “music needs a plane as in painting.”Footnote 63 The search for such an “aural plane” would, in fact, occupy his attention for much of his career, serving as an important heuristic device in his creative process.Footnote 64 Three pages of undated, handwritten text preserved in one of Feldman's sketchbooks from the period of the Projections also speak to his early efforts to reconcile the temporal continuity of music with the sense of spatiality he witnessed in visual mediums, including painting.Footnote 65 Such an association would have been easily cultivated in the artistic laboratory of the Artists’ Club, where space itself served as a frequent, if nebulous, topic of conversation, and moreover one in which Feldman's musical colleagues and mentors participated alongside visual artists.Footnote 66

Employing his new notational format to compose small chamber works, Feldman exploited the visual potential of the graph to its fullest. Christian Wolff, a witness to his creative process, recalled, “He used to put sheets of graph paper on the wall, and work them like paintings. Slowly his notations would accumulate, and from time to time he'd stand back and look at the overall design.”Footnote 67 The visual relationships among instrumental parts in the score constituted the building blocks of such a design. Although Feldman initiated the Projection series with a work for unaccompanied cello, the format served him best as a means of realizing what was an inherently visual conception of ensemble texture and timbre. As he himself would later describe:

What I do is sensitize the whole thing and then I tie it together. It's like a painter. What's a painter got? Form and amounts—touch, frequency, intensity, density, ratio, color. It's just the spatial relationship and the density of the sounds that matters. Any note will do as long as it's in the register.Footnote 68

His manuscript paper on the wall, the composer would attend to these spatial relationships among individual voices and their various combinations, often using the term “weight” to describe the combination of timbre, register, and density that lay at the forefront of his creative concerns.Footnote 69 Whether stacking blocks of sound atop one another, staggering them across the page like cantilevers, or juxtaposing them in dialogue or confrontation, he erected coarse spatial relationships that resulted in audible gestures. Such passages are especially apparent in Projection 2 and Projection 5, the works scored for ensembles, where his gestures are seemingly drawn with broader strokes. If, as he implied, “the new painting” had become his chief model upon composing the second work of the series, these gestures are perhaps best understood as musical analogues to the kind of dense, painterly brushstrokes that inspired imitation among younger painters of Feldman's generation as the 1950s progressed. See, for example, the gradual manipulation of sonic weight that begins in the fifth “measure” of Example 3, taken from Projection 2. Following a characteristic period of silence, the composer staggers his instruments’ individual entries and cut-offs over two bars, ultimately allowing the once-thick sonority to dissipate into a spatter of short, isolated notes, many marked pizzicato.Footnote 70 Silence follows, bracketing this event in space and time.

Example 3. Feldman, Projection 2 (1951), 6. Copyright © 1962 by C. F. Peters Corporation. Used by permission.

Specific control over pitch would have been superfluous to such an experimental approach to the compositional act, adding little to Feldman's effort to intuitively balance sonorities on the basis of their weight, and perhaps saddling his “direct, immediate, and physical” creative process with undue deliberation. The vagueness in the graph's design stoked his drive for spontaneous expression, providing a more direct conduit to the work at hand.Footnote 71 Its inherent imprecision shared little with the imprecision of Cage's later notational experiments, intended to mask subjective expression, but instead resembled the loose form of control in a gestural artist's application of paint, where a less constrictive method was thought to draw the artist closer to the work by eliminating obstacles to its execution. In this respect, Feldman's case is comparable to that of Jackson Pollock, another artist who adopted a seemingly crude creative method in hopes of disabling the force of acquired habit and transforming his approach to the medium. Accused by some of abdicating control, Pollock objected, insisting instead on the primacy of a subjective voice within his work.Footnote 72

Feldman's own insistence on such creative agency was poorly understood during his lifetime and remains stubbornly so today, even when his distance from Cage is acknowledged. To Paul Griffiths, for example, the Feldman of 1950–51 was a young musician “willing to join in [Cage's] pursuit of non-intention.”Footnote 73 To Richard Taruskin, he was a composer aspiring to “achieve l'acte gratuit, the wholly unmotivated gesture.”Footnote 74 Neither of these descriptions is entirely wrong, but both ignore what Feldman called “the opposite side of the coin”: the fact that his graph enabled his creativity in certain respects while restricting it in others, affirming and renouncing in equal measure. Through its affirmations, the new notation sowed the seeds of a highly personal style rooted in a spatialized approach to the compositional act and distinguished by a special reverence for sonority.

In a different sense, however, Taruskin's l'acte gratuit is apt, for Feldman showed little patience when the motivations of others interceded in his work. In offering performers the ability to shape the content of his Projections, he was not soliciting their expressive input; indeed, the avoidance of such a culturally conditioned response in the domain of pitch was a central goal. To this end, the graph proved a failure: within three years he would abandon the format, frustrated in part by performers who took unforeseen liberties in interpreting his notation. Having relinquished his music to the world, he watched unhappily as it was transformed in the hands of others, from the musicians who brought too much of themselves to bear upon its interpretation, to the persuasive colleague whose “broadcast of faith” entailed much the same. In a sense, this transformational process would continue in the decades that followed, as newly developed forms of experimental notation were harnessed by composers to contrasting ends, justified through divergent rationales, and subjected to myriad interpretations.

With this history in mind, Feldman's choice of title for his first series of graphic scores seems particularly fitting: the etymology of the term projection extends back to the practice of alchemy, where it was associated with transmutation, or the process of change that converts one substance into another. To unconditionally situate the Projections at the start of graphic notation's process of postwar “transmutation,” however, would be to conceal the intergenerational conversations that ushered Feldman's works into existence—conversations, like those that followed, rife with misunderstandings and conceptual leaps. As a whole, this transformational process reveals less about the “acoustical reality” of music—so prized by Feldman—than about its social reality. Music may be physically altered by its transmission through a concert hall, but so, too, is it transformed as it passes along the trajectories that link the agents of its inspiration to those of its conception, realization, promotion, appropriation, and study. Along the circuitous course of these projections, Feldman's Projections occupy but a spot.