Introduction

In 1996 a remarkable document was issued by some of the United States’ most influential moral and political philosophers. Coming from different philosophical traditions, Ronald Dworkin, Thomas Nagel, Robert Nozick, John Rawls, Thomas Scanlon, and Judith Jarvis Thomson intervened in a court case as amici curiae in support of the respondents. The plaintiffs were five doctors, three terminally ill patients, and an assisted-dying lobby group. They raised the fundamental questions of whether Americans have a constitutional right to end their lives and whether it is permissible for someone to assist them, if they request that assistance of their own volition. They sought to interpret assisted suicide as a liberty interest. The Philosophers’ Brief, as it has come to be known, zooms quickly in on the paradigmatic patient case that was used in these court proceedings: a terminally ill patient who is in agonizing pain or otherwise suffering intolerably. Among other things, the philosophers write:

Denying that opportunity to terminally-ill patients who are in agonizing pain or otherwise doomed to an existence they regard as intolerable could only be justified on the basis of a religious or ethical conviction about the value or meaning of life itself. Our Constitution forbids government to impose such convictions on its citizens.Footnote 1

The Solicitor General representing the U.S. government in the case conceded, despite his slippery-slope concerns, that “a competent, terminally ill adult has a constitutionally cognizable liberty interest in avoiding the kind of suffering experienced by the plaintiffs in this case.”Footnote 2

Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with the Solicitor General’s concerns, invoking worries about an extension of assisted dying to include euthanasia as well as concerns about an extension of the class of eligible people to include those who are mentally ill, poor, or elderly.Footnote 3 The question of access thresholds that is at the center of current debates on medically assisted dying (MAiD) was clearly uppermost also on the minds of the U.S. Solicitor General and the Supreme Court justices at the time. However, this focus also shows nicely the extent to which that document was a document of its time. It assumes as true what needs to be shown, namely, (1) that decisionally capable mentally ill people, the poor, and the elderly should have their agency removed when it comes to life-and-death decision-making, by virtue of their mental illness, poverty, or age and (2) that voluntary euthanasia should be treated differently from assisted suicide.

Why people seek death

The Canadian government produces an annual report on MAiD. It reports the following on the nature of suffering of MAiD recipients:

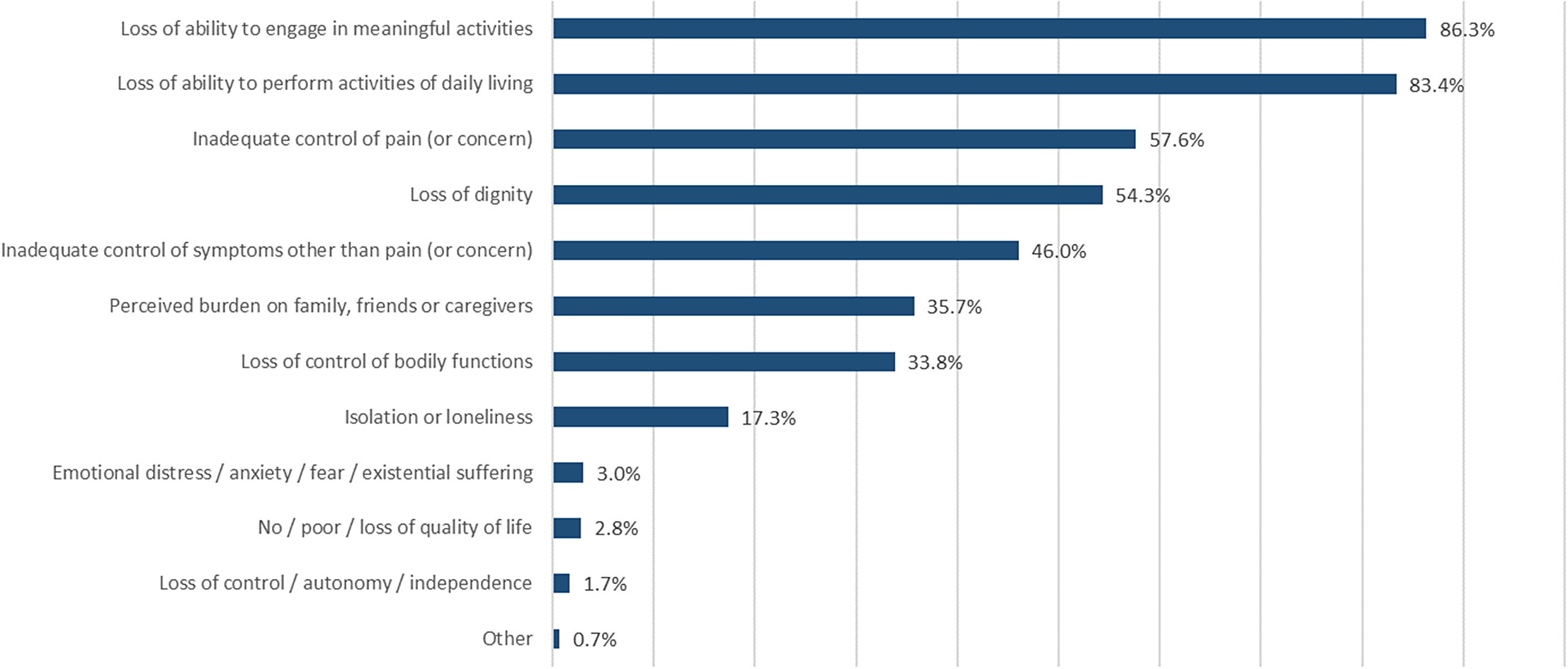

The most commonly cited intolerable physical or psychological suffering reported by individuals receiving MAID in 2021 was the loss of ability to engage in meaningful activities (86.3%), followed closely by the loss of ability to perform activities of daily living (83.4%). These results are very similar to 2019 and 2020 results, indicating that the nature of suffering that leads a person to request MAID has remained consistent over the last three years.Footnote 4

A closer look in Figure 1 at the self-reported nature of MAiD recipients’ suffering yields illuminating results.

Figure 1. Nature of Suffering of Those Who Received MAID, 2021Footnote 5

The majority of MAiD recipients in Canada, as in most other jurisdictions permitting MAiD, are cancer patients. However, and this might surprise some, uncontrolled pain is not motivating many of the intolerable-suffering-related MAiD requests; rather, it is suffering of a different nature. Inadequate pain control or anxiety about the possibility of inadequate pain control is reported as the nature of suffering by 57.6 percent of recipients. While this is a significant number of patients, this figure suggests that more than 40 percent of MAiD recipients are not primarily motivated by the experience of pain or concerns about pain, but by other rationales.Footnote 6

A Belgian study offers results similar to that reported by Canada. Among the reasons why people requested euthanasia, 56.7 percent mentioned pain.Footnote 7 Also, like in Canada, about 40 percent did not want to become a burden on their family, something that John Hardwig considers a sound ethical justification—an obligation, actually—for ending one’s life.Footnote 8 Apparently, the sacrifices loved ones may have to make in order to care for a family member weigh heavily on many people’s minds who consider such assistance. Under any other circumstances this would be considered a noble, selfless gesture, but not so when MAiD is in play. One can hold this view and be highly critical of societies that fail to provide reasonable support services to their elderly and other populations requiring labor-intensive care.

Suicide pacts between married couples have been reported in the literature, where the main reported motive of a healthy partner is to avoid surviving the loss of an often longtime partner from ill health.Footnote 9 Italian researchers report the case of a suicide pact involving a ninety-two-year-old man and his ninety-one-year-old wife: “[T]here was a suicide note, which reported that the woman wanted to end her life and that the man would have followed his wife. In particular, the woman was reporting ‘I don’t want to live anymore,’ while the man ‘forgive me, if she dies, then I want to kill myself because I want to end my life with her.’” Footnote 10 In the Netherlands several hundred, mostly elderly, people requested MAiD because they were reportedly “weary of life.”Footnote 11 About 30 percent of doctors in that country have, at one point or another, received requests for MAiD in the absence of severe disease. Again, it is neither terminal illness nor concerns about pain management that are the motivating factors in these kinds of requests. Oftentimes, advocates opposed to MAiD, especially those writing from a palliative-care perspective, conflate pain and suffering and insist that euthanasia is an unnecessary option because pain can efficiently be controlled by good palliative care.Footnote 12 Even if pain could efficiently be controlled, this would not put an end to autonomous people’s requests for MAiD.

The purpose of this brief look at why people might choose to seek an assisted death is not meant to be comprehensive, which would be unrealistic for the purpose of this essay, but to show that such requests cannot be reduced to the issues of pain management and terminal illness. They are more closely linked to people’s desire to live self-directed lives, which includes the desire to have a self-directed, as-comfortable-as-possible death, when one is ready for it and when one desires it. Assisted-dying campaigners concerned about honesty in public policy discourse might want to consider updating their campaign literature. It does not currently reflect the motives that many people report across jurisdictions for why they desire MAiD.

Most jurisdictions that permit assisted dying limit eligibility to decisionally capable people who are terminally ill and who experience unbearable or intolerable suffering. Given the absence of “terminal illness” as a clinical category, this is typically understood as within six months of an illness-caused death. This would be true for many jurisdictions, including Australia, and various states in the United States. There are exceptions to this, including Belgium, the Netherlands, and (more recently) Canada. Noteworthy, perhaps, the majority of doctors in a large sample of medical doctors surveyed on behalf of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences think that doctor-assisted suicide can be justifiable even in nonterminal cases.Footnote 13 Only 10 percent of respondents thought that terminal illness should be a necessary condition for a person to become eligible for physician-assisted suicide, while 72 percent considered assisted suicide to be justifiable in patients who are not terminally ill. There remains a wide gap between the rationales people seeking MAiD mention for their decision and the regulatory systems governments typically have put in place to address the issue.

While one empathizes with the scenario that motivated The Philosophers’ Brief, namely, that of a dying patient who experiences intractable pain, this actually motivates only slightly more than half of all MAiD requests. Limiting access to this group of patients might unfairly discriminate against others who have different but possibly equally valid motives. A closer look at the reasons why people request an assisted death reveals that neither intractable pain nor terminal illness is what motivates many people to seek an end to their lives. This gap between the imagery that fuels many assisted-dying activist groups’ campaign activitiesFootnote 14 and many people’s actual reasons might explain why there is a growing international debate not so much over whether MAiD should be legalized or decriminalized, but over the question of who should be able to access it. The U.S. Supreme Court justices who were opposed to assisted dying because of concerns that the “wrong” kinds of people might be assisted in ending their lives or by concerns that their lives would be ended by an act of assisted suicide rather than by an act of euthanasia, aided by a permissive regulatory system put in place by a negligent state, would have reason to feel vindicated, except that perhaps they were mistaken in their opposition.

Reasons for wanting to die are individual

Suicide is legal in most liberal Western democracies as well as in a large number of other jurisdictions not known to hold the right to self-determination in high regard, such as Qatar, Egypt, and China, to name but a few. There are good ethical reasons for this. Some have to do with the absence of a good justification for threatening to punish people who unsuccessfully try to end their lives. If death did not deter them from trying to end their lives, what kind of punishment could possibly have the desired deterrence effect? Interestingly, a global survey compared countries that have criminalized suicide with countries that have decriminalized or legalized suicide to determine whether the criminalization of suicide has a deterrence effect. The researchers conclude that “laws penalizing suicide were associated with higher national suicide rates.”Footnote 15 Of course, correlation must not be confused with causation; it is possible that there is no causative effect here and that restrictive regulatory regimes are more indicative of the kind of society that is associated with above-average suicide rates.

Another ethical reason is that it has long been acknowledged that suicide can be rational.Footnote 16 It is not necessarily so, but a suicide can be an expression of an autonomous choice made by a person with decision-making capacity who has a sufficient understanding both of the consequences of their action and of the alternative courses of action that are available to them at the time of their decision-making.Footnote 17 Glenn Graber suggests that rational suicide is possible, “if a reasonable appraisal of the situation reveals that one is better off dead.”Footnote 18 Implied here is a rejection of the view that suicide can never be rational, because nobody can know death and, in the absence of that knowledge, we are unable to take a considered view on whether we would really be better off dead. Jennifer Radden notes that, typically, suicidal people are not acting irrationally or involuntarily.Footnote 19 In a similar vein, Susan Stefan states that the vast majority of people who are suicidal are decisionally capable.Footnote 20

Aiming to prevent the suicides of the minority who happen to be decisionally incapable is ethically uncontroversial. However, and pace suicide-prevention efforts, aiming to prevent suicides of those who have decision-making capacity ought to be controversial. The interference required is strongly paternalistic in nature and that requires a significant degree of justification in any liberal society. It could, for instance, be ethically defensible to interfere with the exercise of occurrent autonomy in order to protect long-term autonomy, say, in the case of someone who quite likely, on reflection, would regret their decision to end their life. However, in cases where the acting person would remain committed to ending their life, such interference would merely have increased their suffering by lengthening it.Footnote 21 To illustrate this, consider the case of the late Adam Maier-Clayton, a twenty-seven-year-old successful business school graduate. Reportedly, he “battled anxiety, mood disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder since he was a child. He says his debilitating pain feels like parts of his body are being burned by acid. Despite a host of treatments, some of them experimental, his agony has only worsened in recent years.”Footnote 22 Maier-Clayton did not suffer from an illness defined as terminal. Supported by his father, he campaigned for a change in legislation to make him eligible for an assisted death. In his view, “If someone is suffering for years and years like myself, then what are you protecting them from? You’re not protecting them. You’re confining them to pain.”Footnote 23 Eventually, Maier-Clayton ended his own life. His obituary reads: “Our loving son Adam has died of rational suicide after suffering from an exotic neurobiological illness with no known cure… . Adam became a standout advocate for broadening eligibility to Medical Assistance in Dying for those suffering intolerable, incurable pain due to physical or mental illness.”Footnote 24 Lack of access to MAiD forces decisionally capable people like Maier-Clayton to investigate ways to end their lives on their own, with all the pitfalls that that entails. (I will describe below these pitfalls.)

Authors such as Radden and Stevens readily acknowledge that decisionally capable people will have individual reasons why they would rather be dead than to continue living. To them, this is not necessarily evidence of lack of capacity. Reasons for wanting to end one’s life are individual in nature, which is reflected also in the studies I mentioned above. Such reasons have to be individual in nature precisely because one’s considered views on whether one considers one’s life unbearable are very personal reasons.Footnote 25

The decision to end one’s life is not one that is typically taken lightly by the person deciding to end their life. Our life is among the most precious things we have. It permits us to gather experiences, form relationships, and is a necessary condition for creating meaning for us. People tend not to end their lives frivolously. As Geoffrey Miller notes: “There is no way to escape the hardwired fears and reactions that motivate humans to avoid death. Suffocate me, and I’ll struggle. Shoot me, and I’ll scream. The brain stem and amygdala will always do their job of struggling to preserve one’s life at any cost.”Footnote 26

Even if one accepts that all decisionally capable people should be able to end their lives as they see fit, without outside interference, it is still unclear why anyone should be permitted to assist them, even if they ask for it. There seem to be two aspects to this issue. One is whether anyone should be permitted to assist them. If we answer this question in the affirmative, a second question is whether a good society might even have an obligation to ensure that such assistance is available.

The moral case for a self-directed (and assisted) death

Various authors from different philosophical traditions make the moral case for legalizing or, at least, decriminalizing self-directed (assisted) deaths in liberal societies. Let me first briefly lay out these well-known arguments and then address in the remainder of this essay both traditional as well as currently popular counterarguments against the case for a permissive MAiD regime.

The most obvious approach in favor of MAiD is liberal or libertarian in nature. People with decision-making capacity are seen to have a liberty right to end their lives. The argument here relies heavily on an autonomous-person-based account, presuming that suicide was chosen both rationally and voluntarily. An autonomous decision requires voluntariness, an ability to reason about one’s situation, and the capacity to appreciate one’s situation. This last entails insights into one’s situation, one’s options, and the consequences of acting on those options. The autonomy view holds that, in some contested sense, we own our bodies and that we have a right to dispose of them as we see fit. A professional volunteering to assist us should thus be able to do so. A Royal Society of Canada expert panel report concludes that “the commitment to autonomy … , thus quite naturally yields a prima facie right to choose the time and conditions of one’s death, and thus, as a corollary, to request aid in dying from medical professionals.”Footnote 27 Of course, this does not settle the issue of whether such a right triggers a corresponding obligation on others (for instance, health-care professionals) or whether it might merely provide license to volunteering third parties to respond to such requests.

Another question is, if we were to accept that there is an autonomy-based right to an assisted death, whether that should entail access to voluntary active euthanasia versus merely a right to receive a prescription for medication that will facilitate an easier suicide. A prohibition of active euthanasia discriminates unfairly against people who suffer from disabilities that would prevent them from ending their own lives with the help of, for instance, prescription medication. Other reasons that support including voluntary euthanasia among ethically defensible assisted-dying modes will come to light below, when we compare various costs of different MAiD-delivery options.

Consequentialists provide different moral reasons for respecting people’s choices who have decided that, intractably so, their experienced quality of life on balance is such that they do not wish to continue living. Quality of life is the key consideration, here, and the objective is to minimize harm. I agree with Peter Singer that a paradigm shift is necessary in modern medicine, if one wants to assign to the medical profession qua profession the obligation to be supportive of people’s choices on grounds of minimizing harm. This paradigm shift would require that health care move its moral foundations from a pro-life ethic to a quality-of-life ethic.Footnote 28

Our perception and evaluation of our own well-being are what matters. As we have seen, quality-of-life considerations cannot be reduced to mere questions of pain management. If the surveys mentioned above are anything to go by, quality-of-life assessments are also always of a deeply personal nature. For that reason, assessment made by a clinician of a patient’s suffering-related claims “is also characterized as requiring reflection, a position of ‘decentering’, and situating the patient’s experiences at the center of care while remaining neutral and withholding judgment.”Footnote 29

Wayne Sumner notes persuasively that for all practical purposes consequentialist and autonomy-based accounts tend to converge when decisionally capable people are concerned because they are the best judges of their quality of life.Footnote 30 The ethically relevant criteria to ground a right to MAiD are autonomous choice (entailing decisional capacity and voluntariness), an intractable condition that renders the decider’s life not worth living in their own considered judgment, and a decision that remains stable over time. These criteria may give rise to legitimate questions about the status of (mature) minors, but I will set that aside for the purpose of this essay.Footnote 31

John Stuart Mill had it right in his On Liberty that we are sovereign when it comes to our bodies.Footnote 32 It is not unreasonable to interfere briefly to assure ourselves that the person who wants to end their life has decision-making capacity and that there is no coercion in play, but otherwise we have no business preventing their death. Respecting autonomous, self-regarding, end-of-life choices should be uncontroversial in a good society. Autonomy requires decisional capacity, so it is necessary to ensure that the choice someone makes is a considered choice that is their own. Nobody should be pressured into requesting MAiD; hence, voluntariness also is an uncontroversial necessary condition. The personal conditions that motivate the decision to request MAiD should be intractable at the time of decision-making. The final condition is one already established in jurisdictions that grant eligibility for MAiD in the absence of terminal illness, namely, the requirement that the wish to see one’s life ended is stable over time. This is, in part, informed by studies showing that the majority of people who try to end their lives, and fail, regret their attempts. However, in one study that followed about 400 people whose suicide attempts ended in failure, 21.6 percent responded that they wished the attempt had succeeded.Footnote 33 This is not an insignificant number of people; others can be identified through applying judiciously the proposed access criteria.

It is not a terribly challenging conceptual step from supporting someone’s right to a self-directed death to acknowledging also that whoever assists that person should also be able to do so. It does not seem plausible to criminalize someone’s conduct who volunteers to assist someone else in doing something that is not illegal in their jurisdiction. If I am exercising my legal right to do A, then having someone assist me in doing A should, all other things being equal, also be legal. Someone could argue that this cannot be applicable to medical professionals, if their profession is opposed to assisted dying.Footnote 34 To those finding this kind of argument persuasive, I want to say that some medical associations (for instance, the Canadian Medical Association) consider assisted dying part of the provision of professional health-care services.Footnote 35 No conflict is seen to arise between providing assisted dying and professional ethical obligations. I think, at a minimum, that volunteering doctors willing to oblige those asking for MAiD could reference these policy stances to justify their actions, if called upon to explain themselves.

I leave open for the time being, if we grant that persons have a liberty right to access MAiD, whether that triggers by necessity a corresponding obligation on other parties (for instance, health-care professionals) to assist or whether it provides merely a justification for a volunteer to assist if they wish. (More on that below.)

Why voluntary euthanasia is preferable to lay suicide as well as to assisted suicide

Let’s consider some concerns highlighted in the following kinds of questions users asked on Quora, a popular social question-and-answer website with about 300 million monthly active users, in a thread addressing the query, “Why is suicide so hard?”Footnote 36

-

• Why is suicide hard to complete?

-

• Is there really no quick and painless way to commit suicide?

-

• Is death by hanging painful?

-

• What’s the easiest and most painless suicide?

-

• What is the easiest suicide method, having the highest success rate and least pain?

-

• How can I commit suicide without fail and pain?

Martin Philips, a Quora user, comments in his response: “Because society and the government view you as a slave … they have taken away all the peaceful, dignified and certain ways to kill oneself. Leaving only dangerous, uncertain and traumatizing methods.”Footnote 37 Philips is not wrong; drugs that could be used to facilitate a peaceful death are inaccessible unless one meets the socially approved justificatory standards mentioned above. This has predictable, harmful consequences. At the time of writing this essay, a report from Canada was making global news. Kenneth Law, a fifty-seven-year-old, reportedly sent more than 1,200 packages with poisonous substances to people globally who wanted to end their lives. He ran a number of websites where he sold equipment designed to facilitate suicide.Footnote 38 People all over the globe, it seems, used his concoctions to attempt suicide.

MAiD, for many who have decided to end their lives, is preferable to an unaided suicide, and that is so for very good reason. A Swedish survey suggests that young men who try to end their lives unaided end up doing so in violent ways:

Poisoning was the most usual method (77.9%), followed by cutting or piercing (7.9%). Attempted suicide by hanging was evident for 37 men (3.1%) and jumping from a height for 25 men (2.1%). The three most frequent suicide methods were poisoning (45.2%); hanging/strangulation (24.3%) and firearm use (11.2%)Footnote 39

A survey of the most common suicide methods in different Asian countries reports that hanging is the most popular suicide method in nine of the seventeen countries reviewed. This is followed by poisoning and jumping off high buildings in Singapore and Hong Kong, possibly due to the density of high-rises in those countries.Footnote 40

Many other surveys in the academic literature report similarly unpleasant ways to die. Compare the horrors of dying by firearm use, strangulation, poisoning, or jumping off skyscrapers with the comparably peaceful deaths afforded to those of us who meet the relevant local regulatory guidelines and are eligible for an assisted death. A journalist writing for a conservative Canadian daily newspaper details the MAiD process in that country and quotes doctors and family members of deceased MAiD recipients who describe death by lethal injection nearly uniformly as “a peaceful transition to the afterlife without any witnessed suffering.”Footnote 41 Those of a nonconsequentialist bent might want to argue that people capable of ending their lives themselves should not be permitted to die by means of voluntary euthanasia, but that they should kill themselves and not ask for the direct termination of their lives by a health-care professional. Consequentialists will not be moved a great deal by attempts to draw a morally relevant line between assisted suicide and euthanasia.Footnote 42 Ethical distinctions between assisted suicide and voluntary euthanasia seem to matter only to those opposed to assisted dying.

Unfortunately, and relevant to the argument advanced in this essay, the success record for self-administered MAiD—that is, people swallowing a cocktail of lethal drugs—is decidedly more mixed, when compared to euthanasia. Higher failure rates; a higher rate of complications; and longer, drawn-out deaths have been reported in drug-assisted suicide. To quantify “longer, drawn-out,” up to ten hours have been reported, leading Canadian authorities to require that a doctor and nurse be in attendance so that a lethal injection can be administered if the MAiD recipient who has opted for an assisted suicide has not died after an agreed-on time frame.Footnote 43 What this suggests is that, on current means available, death by lethal injection is highly preferable both to the violent methods people use when they have no access to MAiD and to a self-administered death involving a lethal cocktail of prescription drugs.

Another reason is worth repeating in this context. As in the case of assisted suicide, MAiD policies that deny access to voluntary euthanasia unfairly discriminate against people who are unable to end their lives themselves, due to their disability or other reasons, and who would depend on an act of euthanasia to exercise their autonomous end-of-life choice.Footnote 44 Incidentally, this is also the rationale given by Canada’s Supreme Court in the case that led to the legalization of assisted dying in that country.

Addressing reasons against permissive access regimes

Concerns about abuse

One of the state’s core responsibilities is to ensure the safety and security of its citizens. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, we have reason to consider the possibility that someone whose life was ended by another person did not ask for their life to be ended. It possibly was murder. The danger of abuse is what opponents of MAiD tend to focus on when they criticize existing assisted dying regulatory regimes or when they campaign against the legalization of assisted dying. In their view, the prohibition of assisted dying is the best guarantee to prevent such abuses.

The assumptions underlying this empirical claim are questionable. Assisted dying has always taken place and takes place in jurisdictions when it was or where it remains illegal.Footnote 45 It occurs in myriad clandestine ways, hidden away from public scrutiny. It seems that the way forward under those circumstances should be to regulate the concerning practice tightly and to ensure maximal transparency in public reporting.Footnote 46

Given that a person’s life is what is at stake here, careful consideration should be given to how the abuse of MAiD can be minimized. However, one thing should be clear from the outset; the objective could not plausibly be to eliminate abuse entirely. This would be an unrealistic objective. Regulatory regimes would have to become too restrictive to achieve this. Overly restrictive regulatory regimes come with at least two types of costs or harm:

-

(1) One is simply that people who should be able to receive assistance and who would request it if they were permitted to, cannot access it. The harm here is the suffering caused to suicidal people by their continuing to live, as well as to people in society who have to deal with the fallout of failed and successful suicide attempts.

-

(2) The second type of cost is arguably caused by assisted dying occurring in a clandestine manner due to its illegality. There are all sorts of avoidable harms caused by this, ranging from botched attempts at rendering assistance to cases where unwanted assistance was rendered. The latter situation is known to arise when assisted dying is illegal and people are unable to communicate freely their wishes due to the legal context. Misunderstandings happen.

Any regulatory regime reviewed by a jurisdiction must consider the cost—in this case, unnecessary suffering—that an overly restrictive, burdensome access regime will cause. What is oftentimes lost in discussions about this issue is that maintaining the status quo is not a morally neutral starting point. The costs and benefits of not acting and keeping an existing restrictive regulatory regime must be balanced against the costs and benefits that enacting a different regulatory regime would entail. A case in point, in terms of the cost or harms caused by keeping a restrictive-access regime’s status quo, are the types of suicides described above as well as the personal cost incurred by people who continue to live a life they consider unbearable.

The view that aiming for a zero-risk regime is unrealistic might sound iconoclastic to some, but it is, in reality, the norm when other policy decisions are made. Let me provide just one example. Modelers investigated whether an increase of the speed limit on the Trans-Israel highway (a six-lane toll road) would lead to a decrease or increase in traffic accident deaths.Footnote 47 The authors suggest that it would lead to a large rise in the number of dead or injured travelers. Of course, increased speed limits also result in time saved for the vast majority of surviving travelers; that benefit is what policymakers have to balance against increases in the number of dead travelers. Public policy decisions often require trade-offs of this sort. It is not necessarily the case that maximum safety does—or should—win the argument over other considerations. In the case of the highway, certain sections of it were built out to six lanes and discussions are ongoing about whether there should be a further increase to ten lanes.

Slippery-slope concerns

Slippery-slope arguments are typically raised in various forms in this context. They have been analyzed and critiqued in great detail. For instance, in the case of Canada’s legislation, it has been shown that the evolution toward a more permissive regulatory regime was not evidence of a slippery slope, because successive legislative changes brought the country’s (still unconstitutionally restrictive) policies closer to the eligibility criteria laid out in the Canadian Supreme Court judgment that led to Canada’s legalization of assisted dying in the first place.Footnote 48 As is often the case, that has not stopped contributors to this debate from repeating their slippery-slope concerns, as if the case to the contrary had not been made, and it has not stopped academic journal editors from publishing this point of view, as if uncontroversial historical facts do not matter to the argument. In Belgium, where assisted dying became available to decisionally capable underage patients (usually referred to as “mature minors”) who are terminally ill, the decision was made after extensive public consultations, by a carefully considered act of parliament that is supported by the vast majority of Belgians.Footnote 49 While one may disagree with the criteria laid out by Canada’s Supreme Court or those applicable in Belgium, none of them constitutes a slippery slope. The gradual evolution of MAiD regimes from restrictive to more permissive is in and of itself not evidence of a slippery slope. Neither is an increase in the number of people who avail themselves of assisted dying. By the latter logic, a public service taken up by an increasing number of people would have to be considered a lamentable slippery-slope state of affairs. One needs to be opposed to assisted dying to begin with in order to find per se a fault in such developments. Given the exceedingly low quality of our natural dying processes,Footnote 50 if anything, one ought to express surprise about the relatively small number of people who avail themselves of MAiD.

Invariably, in this context, the Nazi “euthanasia” program is brought up. A possible argument could proceed roughly as follows. There was a writer by the name of Adolf Jost who published in 1895 a fifty-three-page argument in favor of a person’s right to a self-determined death and a state obligation to implement this right.Footnote 51 A few decades later, two other German writers, Karl Binding and Alfred Hoche, paved the ideological way for the Nazis’ version of a “euthanasia” program, resulting in the mass murder of people with disabilities and others they considered not worthy of living on economic, ethnic, or other grounds.Footnote 52 It is then suggested that these are all extensions of scope resulting from Jost’s arguments. None of that is true. There is a wide gap between an argument for assisting in a self-directed-death request made by a decisionally capable adult and the murder of people who did not ask for their lives to be ended.Footnote 53

Slippery-slope endpoints, for our purposes, are broadly defined as unwanted, unintended, and undesirable events that occur as a result of a prior slippery-slope policy or regulatory decision. In the case under consideration, the permissive regime I propose is deliberate and it is morally desirable. It would not qualify as a slippery-slope type of event.

An important implication of extending the scope of MAiD along the lines proposed in this essay is that not everyone eligible for assisted dying would qualify for the label “patient.” As just one example, recall from above the reported Italian case of a suicide pact involving a ninety-two-year-old man and his ninety-one-year-old wife. In the eyes of some, this would be a paradigmatic slippery-slope case. The justices of the U.S. Supreme Court were concerned that anyone other than someone who is terminally ill should be able to access assisted dying. They considered this to be a slippery slope so dangerous that they refused to decriminalize assisted dying even for the unbearably suffering terminally ill who request it. They were mistaken.

Social determinants of health

Arguably, the strongest and most sustained opposition to permissive MAiD regimes comes from writers and activists whose arguments are based on varieties of what one can label “social determinants of health” arguments. They play out in various forms, depending on the category of patients concerned. These types of arguments could also be deployed if nonpatients were considered eligible for assisted dying.Footnote 54 The general argument is that there is a risk that people would ask for an assisted death not because their illness is rendering their lives not worth living in their own considered judgment, but because of their inability to receive the assistance they require to enjoy a life they would consider worth living.

Here is how this argument plays out in cases of competent patients with mental health issues. It is pointed out that they oftentimes are unable to find professional help when they need it most. This is a result of systemic underinvestment in mental health services ranging from psychiatrists and psychologists to psychotherapists and specialized social workers. The argument then continues by labeling such patients as vulnerable, pointing to the consequences that lack of these services has on the ability of such patients to function well in society. For instance, it appears to be the case that mental illness increases the risk of people becoming unhoused.Footnote 55 Some mentally ill unhoused people might then ask for an assisted death because their quality of life is such that they would rather be dead than continue the life they are living. However, because they are vulnerable and because something could be done to improve timely access to services, including appropriate housing, so goes the argument, they should not be eligible for MAiD.

Another category of patients where a similar analysis has been put forward are people with disabilities. Here, again, critics point to the demonstrable lack of available support services and accommodations that result in many people with disabilities experiencing a lower quality of life than would otherwise be the case. One can easily see, for example, how a person who acquires disability later in life would experience a significant impact on their cash flow due to lost job opportunities. This has an immediate impact on their ability to live their lives as they knew it, ranging from their inability to maintain social connections due to limited mobility and likely higher costs of living in the face of lower levels of income. The argument sometimes is expressed along the lines that it is not the disability, but the social determinants of health, that renders someone’s life not worth living in their considered judgment. Perhaps in reality it is a mixture of both. Like in the case of mental illness, the anti-choice position here, too, argues that people who find themselves in such circumstances are vulnerable and must not be eligible for an assisted death.

Some disability rights activists express the fear that granting such people access to assisted dying would also imply that society does not think the lives of people with disabilities are as valuable as those of people who are not disabled. They oftentimes subscribe to something called the “mere difference” view, which worries that solely the social determinants of health can render the life of a person with mental illness or disability not worth living.Footnote 56 Mere difference, as the label suggests, could mean that someone who is quadriplegic is merely someone who is different, in the same way that some people have brown eyes and others have blue eyes.

It is worth noting both with regard to mental illness and to disability that the claim that it is solely the social determinants of health and never the nature of the illness that renders a patient’s life not worth living in their own considered view, is very much a contested claim. For the purpose of this analysis, I will assume that the “mere difference” view is true. It seems to me that if the mere difference view were true, an argument that would succeed in establishing a right to an assisted death in those circumstances would also be successful in the case of nonpatients. After all, if the mere difference view is true, it would follow that the low quality of life experienced by these people is not caused by their health condition but by other factors.

If it were true that all mental illness and disability cases are cases of mere difference, where the allocation of additional resources for services and accommodations of various kinds could lead to the elimination of all assisted dying requests from people with mental illness and disabilities, should one not make the eligibility to assisted dying for such people subject to the reliable and comprehensive provision of such services and accommodations? This is essentially the argument made by anti-choice activists and allied academic writers on this issue. They are appalled that society would consider making vulnerable people from these groups of patients eligible for assisted dying while not providing needed services and accommodations to them.Footnote 57

This argument has a certain emotional appeal used to maximum effect by political pressure groups such as Not Dead Yet.Footnote 58 A word of caution is perhaps in order, when it comes to arguments over the inclusion of people with disabilities among the categories of people who should be eligible for assisted dying. Activist groups such as Not Dead Yet have achieved a fairly high public profile, but it is not clear that they represent many or even the majority of people with disabilities.Footnote 59 Their language is suitably theatrical and in equal measure misleading: “[T]he disabled community is reaping the consequences of a society that is so apathetic toward disabled people’s basic needs that it can’t even be bothered to provide us with suicide prevention. We are dirt.”Footnote 60

Arguments presented by opponents of assisted dying might look familiar to readers knowledgeable of the literature on assisted dying. Opponents of assisted dying, when the focal point of the argument is the pain and suffering of the terminally ill, never tire of arguing that MAiD should never become an option until everyone who could benefit from palliative care and who is asking for it has access to high-quality palliative care. One can find polls sponsored by activist groups where the surveyed public is asked whether they would want palliative care or euthanasia, as if this was a plausible scenario of alternatives to begin with. As if anybody would have said, “I hate palliative care, so let’s legalize euthanasia.” Assisted dying has since been legalized in many imperfect jurisdictions. The reasons were obvious. While nobody is opposed to the provision of high-quality palliative care, the establishment of a perfect palliative care system could not possibly be a necessary condition for the legalization of assisted dying.

One rationale in support of this conclusion is that there might never be a perfect health-care system. It is an unrealistic requirement. Furthermore, one should not hold decisionally capable people who are requesting an assisted death hostage to the establishment of this perfect system, seeing that it may not come in their lifetime, if ever. This view was also expressed by a Canadian judge in her landmark Carter v. Canada decision that paved the way for the Canadian Supreme Court’s decision on MAiD: “[T]he argument that legalization should not be contemplated until palliative care is fully supported rests … on a form of hostage-taking… . [T]his argument suggests, the suffering of grievously-ill individuals who wish to die will serve as leverage for improving the provision of adequate palliative care.”Footnote 61

The same argument holds true vis-à-vis anyone else who is decisionally capable, understands the consequences of their choice, and who makes an autonomous choice to ask for an assisted death. If one wants to reduce the number of people asking for MAiD, the proper course of action surely should be to improve their social determinants of health—especially if one holds the “mere difference” view—rather than remove their agency to make important self-regarding choices involving life and death.

Some might agree with this analysis but remain skeptical with regard to one of its premises, namely, that a decision to end one’s life under conditions of arguable social injustice is substantially autonomous. This skepticism is not well-founded. On legal grounds this matter is already decided. People like the woman in the example described below are, all other things being equal, legally capacitated. Let us consider at this point a tragic, extreme real-life situation. It involves a fifty-one-year-old woman who reportedly chose an assisted death because she suffered from severe sensitivities to particular common chemicals and cigarette smoke. She “chose medically-assisted death after her desperate search for affordable housing free of cigarette smoke and chemical cleaners failed.”Footnote 62 There is reason to doubt some of the reported details of the story because, based on the published information, this person would not have been eligible for MAiD at the time when it happened in the country that she lived in. However, again, let us assume for the sake of the argument that this is all there is to the story. She was a relatively impoverished patient living in a charity-run accommodation, with severe sensitivities to the cleaning agents used in the property as well as to the cigarette smoke coming through the ventilation system into her apartment. She tried unsuccessfully to get accommodated by her landlord and government officials.

In a good society, this person would have been accommodated. In the real world, landlord and government officials mostly ignored her plight. She asked for and received MAiD. At the same time, this patient made quite clear that she would not have requested an assisted death had it not been for her social determinants of health, which entailed her inability to move to what she (and supportive doctors familiar with the case) considered appropriate accommodation.

Cases like these are tragic. However, a simple thought experiment will help us in determining whether the availability of MAiD was morally objectionable. Let us take at face value what has been reported about this patient and her views on this matter. If one wants to establish whether the availability of the provision of assisted dying, on her request and after extensive capacity assessments took place, was morally problematic, one should ask the following question: Would she have been any better off if assisted dying had not been available to her? Evidently, the availability of assisted dying had no impact on whatever other government and landlord assistance was available to her. If one were to remove assisted dying from the equation, she would still have found herself in the very same situation that triggered her request in the first place. She would have been worse off for not being able to request an assisted death. That does not diminish the tragic nature of the situation and it can support the view that the social determinants of health that contributed to her decision were the result of living in an unjust society. In a good society, where either government or her landlord had acted and had provided her with suitable accommodation, she might not have chosen an assisted death. In either situation she was not worse off for the availability of assisted dying; rather, she was better off for it in her real, reported situation and she would have been no worse off for its availability if appropriate housing and services had been provided to her and she had chosen to continue living.

It follows that the availability of assisted dying to people who report that their social determinants of health have caused their request for an assisted death is not morally objectionable. The anti-choice argument here was deployed along lines similar to the historical anti-choice arguments, vis-à-vis palliative care, that I described above.

It seems to me that this same analysis is also applicable to the case of non-patients. If intractable factors other than health result in someone decisionally capable wanting to end their lives, where it is beyond their capacity and those in their social context to change that status quo, they are in circumstances morally equivalent to those of people with health issues such as those discussed above. It is inconsequential that health problems are the cause of the wish to die in their instance and other reasons cause nonpatients to want to end their lives when the intractable basis for the request is a quality of life so low that those concerned, after careful considerations of their options, do not wish to continue living.

Competence assessments: The strong paternalists’ last stance

Most of us, even if our lives are not exactly great, do not consider, let alone attempt, suicide. Despite this fact, much has been made by opponents of permissive access regimes of the alleged difficulty in assessing someone’s decisional capacity or competence, should they express the desire to end their lives. To them, the wish to see one’s life ended is in itself evidence of a high risk of diminished decisional capacity. Some argue, given that human lives are at stake, that capacity assessments ought to be risk-related. Given the value we justifiably ascribe to human life, it is easy to see how a risk-related standard of competence might be the tool a determined strong paternalist would need to justify permanently withholding access to an assisted death. One simply declares that the person asking for an assisted death is irrational or unreasonable. Indeed, some opposed to permissive assisted-dying regimes have made just that case again.Footnote 63 Arguments about standards of competence have a history going back several decades. Joel Feinberg rightly reminds us that there is a morally relevant difference between demands to respect irrational choices made by irrational agents and unreasonable choices by autonomous, competent individuals: “Part of the point of calling such choices ‘unreasonable’ is to suggest that they reflect judgments of comparative worthwhileness that we would not make were we in the chooser’s position.”Footnote 64 The problem with this argument is that, in reality, we are never in the chooser’s position, because our values and life histories are bound to differ.

Allen E. Buchanan and Dan W. Brock are well-known proponents of risk-related standards of competence. They argue that “the standard of competence ought to vary in part with the expected harms and benefits to the patient in accordance with the patient’s choice.”Footnote 65 The problem with such an approach is that competence then ceases to be something that one objectively has because, as Gita S. Cale notes, “understanding competence as related to outcomes (and risk) requires the unjustified introduction of normative values into the assessment of competence, and thus, confuses the kind of competence an objective (and non-paternalistic) standard of competence aims to assess.”Footnote 66

Mark Wicclair also cautions against risk-related standards of competence. He rightly points out that “there is a danger that standards of understanding, reasoning, and so forth will be set arbitrarily and unattainably high by those who believe that paternalism is justified when perceived risks are great.”Footnote 67 Paul S. Appelbaum reports that, typically, “[l]egal standards for decision-making capacity for consent to treatment … generally … embody the abilities to communicate a choice, to understand the relevant information, to appreciate the medical consequences of the situation, and to reason about treatment choices.”Footnote 68 This is in line with the relevant policy established for the Netherlands by that country’s Regional Euthanasia Review Committees: “Decisional competence means that the patient is able to understand relevant information about his situation and prognosis, considers any alternatives and assesses the implications of his decision.”Footnote 69 Notably absent here is any suggestion that there should be different levels of competence required, depending on the risk involved in the decision.

This matters for decisions on access thresholds to MAiD. Paternalistic providers, tasked with assessing the competence of a person requesting an assisted death, might be tempted to declare the person incompetent, especially when there is no evidence of pain or terminal illness. What they might consider to be unreasonable, based on their own values as opposed to the facts of the request, could quickly turn into the label “decisionally incapable.”Footnote 70 Neil John Pickering and colleagues conclude quite rightly that risk-related standards of competence are nonsense because “there is no rational form of relationship between the risk of a choice and the degree of capacity needed to make it. Such a relationship is, however, necessary for risk relativity to make any rational sense.”Footnote 71

I think, despite the significant literature arguing in favor of risk-related standards of competence, that the matter at hand can be addressed in a manner that avoids the strong paternalism charge. The criteria described above for the Netherlands seem a defensible blueprint for other jurisdictions wanting to take their citizens’ right to self-determination seriously.

Role of health-care professionals

At this point, it is time to revisit the question of what the proper role of health-care professionals is in this context. Depending on cultural context, there exists great variation in terms of health-care professionals’ support for assisted dying and there exists even greater variation in terms of health-care professionals’ support for assisted dying for patients who are not terminally ill. Undoubtedly, if assisted dying was made legal for people who, by most definitions of “health,” do not qualify as patients, many health-care professionals might be reluctant to render assisted dying to such persons. Because some argue that doctors have a professional obligation to provide assistance in jurisdictions where that assistance is legal and where doctors are the designated providers of such services,Footnote 72 it does not seem unreasonable to ask whether doctors should have that kind of obligation toward people who are not patients.

It seems to me that if doctors are the professionals, in a given society, who are tasked with the provision of assisted dying and they are the monopoly provider of such services, as is usually the case with these professions, they arguably have an obligation to provide these services.Footnote 73 It seems implausible for a particular profession and its members to hold a societal monopoly over the provision of certain services to members of society, only to then see that many or most professionals decline to provide those services.Footnote 74

On the one hand, societies have good reasons to hand over the provision of such services to professionals. These reasons are related to the uncontroversial state function of ensuring the safety and security of citizens and residents. Precisely because professions are tightly regulated and monitored, this provides a good rationale for tasking (medical) professionals with the provision of assisted dying. It adds additional layers of security to the practice in question.

On the other hand, it is understandable that doctors might object to being tasked with the responsibility of ending the lives of people who are not patients and who have merely made an otherwise-motivated, well-considered autonomous choice to want to end their lives. It is at least arguable that absent someone being a patient, the provision of such a service no longer falls under the category “health care.” Of course, a society could adopt an expansive definition of health, along the lines envisaged by the World Health Organization.Footnote 75 On such an account, nearly everyone is a patient.

It seems that, at a minimum, volunteering doctors should be able to provide this service in jurisdictions that have adopted such a permissive regime. If doctors are the designated professional monopoly providers of this service in a particular jurisdiction, they ought to provide it. However, I think it is worth serious consideration whether an assisted-dying profession as tightly regulated as the health-care professions are might be a possible regulatory and policy alternative to tasking doctors with the provision of these services to people who are not patients.

Conclusion

The reasons why decisionally capable people desire to see their lives ended do not map easily onto the current regulatory frameworks that determine access thresholds to MAiD in liberal democracies. Good societies ought to respect and support the end-of-life desires and choices of their citizens. If a decisionally capable person has made a considered choice to seek an assisted death, suicide is legal, that request is stable over a reasonable period of time, and it is voluntary, a good society ought to assist such people in ending their lives as peacefully as is feasible. Depending on the jurisdiction, that may include at a minimum the legalization of assisted suicide and euthanasia, so that willing professionals may assist those in need, or it may include a state-guaranteed provision of such services. Once a decision is reached that a person is eligible, their request should be granted. No distinction should be drawn between assisted suicide or voluntary euthanasia. The only relevant consideration should be which life-ending method brings about the death of the decisionally capable person who requested it with the least discomfort.

Acknowledgments

I owe a great deal of gratitude to Bob Baker and Alberto Giubilini, who read earlier drafts of this essay and whose detailed critiques resulted in a fair number of substantive changes. I suspect they might still not be persuaded by my views on slippery slopes, but I responded to their concerns to the best of my ability.

Competing interests

The author declares none.