“They over-make nyanga.” Bekene Eyambe, a lively woman in her sixties, was referencing the excessive sartorial patterns and bodily practices of the French-speaking Cameroonian women of the 1960s (interview, Buea, November 8, 2011). Nyanga is a Cameroonian Pidgin English (or Cameroonian creole) term for varied ideas about beauty and stylishness (Nkengasong Reference Nkengasong2016:33). Bekene is an English-speaking resident of Buea, originally from the neighboring town of Kumba, and I interviewed her on a rare sunny day in the middle of the rainy season in front of her house, which hugs the side of a major street in her neighborhood. During the interview, she busily fried puff puff, or beignets, a sweet dough fritter that is popular throughout the West African region. Anglophone women, Bekene claimed, made “their own nyanga” in the 1960s by wearing minimal cosmetics and donning African-style attire. But she noted the economic underpinning of nyanga: “It depends on your money how much you do nyanga. When money [is] not there . . . you [for example] cut your hair short.” Bekene looked up from frying puff puff at one point during the interview and used one hand to shield her eyes from the sun. She pointed to the street and asserted that female students of all cultural backgrounds who attended the nearby university sometimes walked by in what she considered immodest dress: “Today they do not have respect when they dress. They do naked themselves.” The implication that contemporary Cameroonian women, regardless of their cultural backgrounds, “over-make nyanga” sheds light on how individuals in metropolitan Cameroon have long connected diverse external bodily practices to inner psyche, shaping varied ideas about culturally constructed forms of feminine aesthetic purity, or, in other words, “authentic” black beauty.

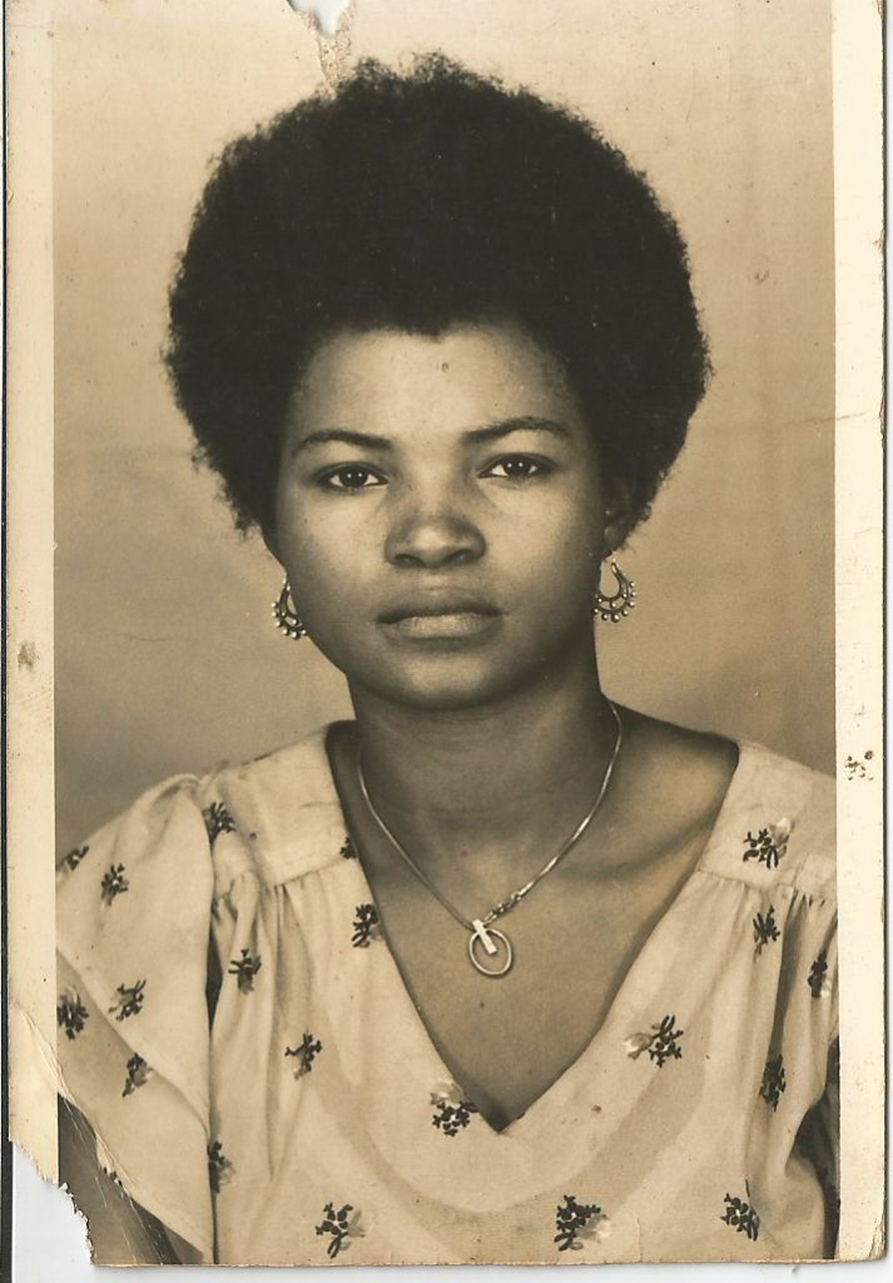

Figure 1. Natural beauty? Although the photo was taken in a photo studio in Victoria (modern-day Limbe) in 1975, her bodily aesthetics—her afro, minimal cosmetic wear, and western-style clothing—are reminiscent of hybrid understandings and reflections of beauty rituals and sartorial practices in 1960s Anglophone Cameroon. Photo owned by historian Walter Gam Nkwi.

This study contributes to debates on bodily practices and performances, underscoring the importance of how emotional expressivity and “natural” body manipulation and behaviors drive discourse on an “authentic” beauty, supposedly not always characterized by artifice. Bekene’s commentaries about women’s excessive sartorial practices and their relationship to money illuminate contradictory nationalist and cultural identities present in 1960s Cameroon, a West/Central African country with the legacies of both British and French rule. Two federated states aligned with these European legacies during this period. Further, Bekene’s assertion that various women “over-make” nyanga hints at the complex nature of mastering natural beauty. Within this context, the idea of women’s bodies as architecture reflects the double-bind they faced. While many Cameroonians applauded women’s engagement with new beauty trends, excessive nyanga—possibly demonstrating undisciplined bodily practices and inclinations—might betray representations of suitable feminine ideals within the dominant Cameroonian cultural ethical frameworks.

Using print records and oral interviews, this study examines how Anglophone urban elites negotiated local and global ideas about culturally constructed forms of African authenticity, or, simply, “natural” black beauty. References to women’s experiences with consumer culture and newly constructed bodily practices and attitudes are highlighted to examine emergent ideas about cosmopolitan African womanhood in Cameroon during the 1960s, an era of rising (Anglophone) nationalism in the country. Formally-educated Christian urbanites, such as freelance female journalists, who often worked as civil servants, sought to discipline women’s bodily practices and emotional expressivity in order to regulate the boundaries of perceived feminine respectability and to define a woman’s “natural” beauty within a metropolitan setting. They described a “natural,” or “pure,” black African aesthetic that was informed by both disciplined internal qualities, such as an appropriate level of emotional confidence, and external merits relating to judicious bodily practices and decorum, such as restrained cheery dispositions. Such individuals drew from disparate ideas and influences across time and space to discipline women’s bodily practices and attitudes. Those sources included indigenous, or local, values; the legacy of Western-originated Christian missions; English-speaking Cameroon’s close social, educational, and political ties to Nigeria during British rule; ongoing pan-Africanist discourses related to the 1960s “black is beautiful” movement; and a growing global capital market that resulted in the influx of various toiletries from Europe. Within this context, Anglophone urbanite elites considered “natural” beauty a feeling and a bodily inclination that signified social and racial progress. While a woman might judiciously engage in consumerism by curbing the excessive purchase and use of cosmetics—thus preserving dominant understandings about standards of respectability for women—she might also “master” “natural” bodily practices by manipulating olfactory preferences to fabricate a pleasant bodily odor through moderate perfume use. However, as a Foucauldian notion of discourse suggests, women were not passive bodies on which acts of disciplinary forces were acted (Foucault Reference Foucault1979:136). This study applies a logic similar to Shirley Tate’s in her work on ideas about contemporary black beauty, which suggests black women can widen the boundaries of black beauty, mediating varied “discourses of belonging and exclusion while simultaneously articulating subjectivity and agency” (2007:300) to discourse on black natural beauty in 1960s Anglophone Cameroon.

Discourses on “natural” beauty blossomed in English-speaking regions of metropolitan Cameroon in the 1960s. Contemporary Cameroon was under German colonial rule from 1885 until the end of the First World War. At that point, a League of Nations mandate—reclassified as United Nations trust territories after the Second World War—divided Cameroon between Britain and France. France controlled the bulk of the territory, but Britain controlled a smaller portion, some of which it governed from Nigeria, until 1954. At that time, the British government gave the Southern Cameroons an autonomous House of Assembly in Buea; the city became the capital of the West Cameroon State after independence in 1961. In that year, the Southern Cameroons merged with the area of Cameroon that France had controlled. Although cultural identifications crossed the border between the two federate states, for example, in the Bamenda (western) Grassfields, during the federal period, which concluded in 1972, Anglophone Cameroonians defined bodily practices to sharpen ideals of Anglophone cultural and national identity within urban spatial boundaries. Like Bekene, many emphasized distinctions in the ideals of Anglophone and Francophone Cameroonian identities in their response to globally circulating ideas about sartorial trends, aesthetic practices, and changing attitudes (Mougoué Reference Mougoué2016:8–9, 11, 14). Various individuals (re)defined new bodily practices against the backdrop of a hopeful temporality in which women enjoyed increased access to formal education and employment. Such women drew from a vast repertoire of international experiences and knowledge that their social positioning afforded them, facilitating rapid changes in gender norms.

Attitudes toward the appearance of the skin and of bodily practices shift and reveal evolving social, national, and cultural identities. Hildi Hendrickson (Reference Hendrickson1996) maintains that, by taking the body surface as a category of analysis, much can be learned about individual and social identities. Tony Ballantyne and Antoinette Burton remind us that women’s bodies in particular “have been a subject of concern, scrutiny, anxiety, and surveillance in a variety of times and places across the world” (2005:4). Nira Yuval-Davis concluded that intense societal scrutiny on women’s daily actions reflect a perception of women as the “authentic” representatives of the nation because they “produce nations, biologically, culturally, and symbolically” (1997:2). Sylvia Tamale contends that, in African societies, “[w]omen’s bodies constitute one of the most formidable tools for creating and maintaining gender roles and relations” and that “[a]lthough the texts that culture inscribes on African women’s bodies remain invisible . . . they are in fact critical for effecting social control” (2011:216). In 1960s English-speaking Cameroon, women’s everyday actions, such as their cosmetic and sartorial practices, figured importantly in symbolizing dimensions of the national cultural values in the early post-independence period.

Nyanga offers an opportunity for a temporal and analytical extension of Lynn Thomas and Walter Nkwi’s focus on emergent forms of African womanhood in colonial sub-Saharan Africa, highlighting continuities and fractures in the way urbanites in the 1960s strived to (re)define ideal womanhood. As Thomas and Nkwi show, formally-educated urban Africans employed varied idioms such as the “modern girl” or “women of newness” to envisage an ideal feminine figure that reflected the progressiveness of African cultural values during and after colonialism. Thomas’s work on beauty in South Africa in the 1920s and 1930s describes Christian mission-educated black South Africans’ representations of the “modern girl” as intersecting with local and global ideas about feminine bodily practices and standards. She asserts that “some social observers saw African young women’s school education, professional careers and cosmopolitan look as contributing to ‘racial uplift’” in segregationist South Africa. But some accused the “modern girl” of sexual immorality because of “their engagement of international commodity cultures,” cosmetic use, provocative clothing, and singlehood (Thomas Reference Thomas2006:461, 462, 464). Nkwi documents a similar figure, the “woman of newness,” among the Kom people 1920–61 in the Bamenda Grassfields, which were at the time located in the British Southern Cameroons. Traveling to and working in more economically robust coastal towns, such as Victoria (modern-day Limbe), Buea, and Kumba, facilitated such women’s engagement with new economic activities, global commodity cultures, hygienic practices, and Western-style clothing (Nkwi 2014:1, 6). Similarly, in 1960s urban Anglophone Cameroon, formally-educated women—unlike those Nkwi studied, long Christianized—who entered formal professional employment drove many urbanites to associate certain bodily practices and behavior with “racial uplift” (Thomas Reference Thomas2006:46), nationally and even into the diaspora.

The consumption of new commodities such as toiletries and cosmetics has shaped feminine subjectivity and (re)defined social identities beyond the artifice of ideal womanhood. Judith Butler contends that “[t]he figure of the interior soul understood as ‘within’ the body is signified through its inscription on the body, even though its primary mode of signification is through its very absence, its potent invisibility” (2002:172). In other words, the psyche, or internal drive, is “a sense of stable contour,” a form of enclosure, that can be “achieved through identificatory practices” (Butler Reference Butler2011:xxii). From this mindset, individuals might experience external appearance as an internal feeling by using commodities that are vessels of various gendered identificatory practices. For instance, Timothy Burke argues that “[b]ecause toiletries work on or through the body, they function in one of the most intensely contentious aspects of modern identity. The material body is often in plain sight, but the social body, as an artifact of the self and a canvas for identity, is both indispensable and invisible” (1996:4). Likewise, Constance Classen, David Howes, and Anthony Synnott assert that artificial fragrances enlist “smell . . . to create and enforce class boundaries [and] ethnic and gender boundaries” (1994:8). As this study shows, scrutinizing olfactory practices and somatic pleasures is one way in which the disciplining of women’s bodily practices emanates suitable feminine bodily presentations and particular social positionings.

Methods

Women’s columns in English-language Cameroonian newspapers, oral interviews, and lexical knowledge provide an opportunity with which to examine how formally-educated Christian Anglophone urbanites policed women’s bodily practices and attitudes in the 1960s. Ericka Albaugh and Kathryn de Luna describe “language change and movement” as “a lens through which to understand other historical process” (2018:9). Nkwi examines the lives of “women of newness” by employing the use of kfaang, “which among the Kom people connotes newness—innovation and novelty in thinking and doing, and the material indicators and relationships that result from it” (2014:1). Following these models, I use historical linguistics, the history of the development of languages, to excavate how 1960s urbanites questioned and reframed an existing social order in patriarchal and Christian urban spaces based on their lexicon and vernacular phrases, including both local terms such as “nyanga” as well as standard English terms.

I draw on newspapers with the caveat that, while they were privately owned, political elites funded them, and they had strong ties to political parties as well as funding from these parties. John Ngu Foncha, simultaneously Prime Minister of West Cameroon and Vice President of the Federal Republic of Cameroon, founded the Cameroon Times, and his main political rival, E. M. L. Endeley, founded the Cameroon Champion.Footnote 1 West Cameroon papers with less obvious political ties were equally permeable to state propaganda, although, unlike most papers of East Cameroon—most of which did not have women’s advice columns—they were not government-owned. However, as this article reflects, I found no distinction in the rhetoric of the women’s columns that appeared in these newspapers regarding bodily practices. Note that men wrote more published letters to the “women’s” columns than did women, which suggests that both men and women were readers. Those letters may reflect that, at that time, men were better educated than women were. Indeed, male teenagers in 1964 West Cameroon, for example, were five times as likely to have had a primary education as girls their own age. However, even boys had only a 34.6 percent rate of participation, and only 2.3 percent of teenage girls and boys had technical, secondary, or higher education.Footnote 2 Thus, the columns provide a specific and limited set of views on cosmopolitan African womanhood in the early period of independence.

Oral interviews conducted in 2011 and 2015 with formally-educated women in Buea in their fifties and older, such as Bekene, complement and sustain my findings from the newspaper sources. These women were in their late teens and early twenties during the 1960s.Footnote 3 Their anecdotes about their engagement with new beauty practices illustrate that ideas about bodily conduct and aesthetic rituals resonated in varied terminology and reveal the experiences of Anglophone Cameroonians who endeavored to shape what emerged as a distinct hybrid cultural identity.

Women, Gender, and Hygiene

British Rule

Many male and female letter writers, journalists, and interviewees were highly literate and had formal schooling; they were often Christian mission-educated in Cameroon or Nigeria, although some were Western-educated. Protestant groups such as the Jamaica Baptist Missionary Society and the English Baptist Missionary Society were active in the period of British rule from the mid- to late 1880s. The Basel Mission Society, a Christian missionary society founded in Germany, was active in Anglophone Cameroon from the late 1880s to the mid-1900s. The American Presbyterian Mission also had a presence. Thus, many African women first encountered European rule at a Christian mission station or in missionary schools designed to produce “good” Christian wives for Christian African men educated in mission schools for boys. Curricula included religious education, cookery, and housekeeping (Adams Reference Adams2006:1, 3, 4). Bodily practices focused on maternal and infant health care (Burke Reference Burke1996; Hunt Reference Hunt1999).

Missionaries linked cleanliness, virtue, and godliness for both sexes (Burke Reference Burke1996:17–34; Hunt Reference Hunt1999:122, 130), but judged women more harshly for failing to live up to standards of hygiene. Laura Burton (1987), an American Baptist missionary, documents accounts of unannounced cleanliness checks in the homes of the wives of male seminary students in Cameroon in the waning days of European rule. Such associations between domestic cleaning, personal hygiene, and apposite moral comportment were taught in the neighboring Belgian Congo (Hunt Reference Hunt and Hansen1992) and also in settler Rhodesia (Burke Reference Burke1996). This history led to many of the formally-educated Christianized individuals in Anglophone Cameroon asserting in the 1960s that embracing “natural” beauty was akin to accepting a gift from God.

But Christian mission-educated Africans shaped hybrid (urban) identities by renegotiating the meaning of new everyday practices within colonial settings. As Melinda Adams points out, “African women were not just passive recipients of missionary and colonial doctrine, they were also active agents who reinterpreted and reshaped these messages.” For example, Cameroonian women in the British Southern Cameroons used baking and sewing skills learned in missionary domestic science classes for profit (Adams Reference Adams2006:3). Hunt describes “the creolization and transcoding” of bodily practices in the Belgian Congo (1999:10); Nkwi observes that adopting new everyday (hygienic) practices allowed “women of newness” to enter “a new social stratum in [British-ruled] Kom” (2006:6). The reworking of varied hygienic practices created real social power. Also, like their European-ruled counterparts, urban women (and men) in 1960s English-speaking Cameroon would renegotiate varied ideas about dirt and hygiene, driving new everyday practices.

Post-Independence

Anglophone Cameroonians in the post-independence era retained ideas gained from their mission education linking health and cleanliness to godliness, virtue, and moderate natural bodily aesthetics as a celebration of God’s original creation, all traits that marked the trope of a hybrid respectability in metropolitan regions. Like their counterparts throughout colonial and postcolonial Africa, educated urban elites saw themselves as having a special role in defining morals and respectability and, relatedly, in defining the nation, a crucial function given West Cameroon’s relationship to the hegemonic Francophone East Cameroon State. Thus, they scrutinized the behavior of formally-educated urban Anglophone women from high school age on up, endowing them with the responsibility for modeling respectability while simultaneously exhibiting the progressiveness of Cameroonian societies by embracing new global cultural trends. Nonetheless, educated urbanites condemned the “free” or “loose” urban woman as westernized and sexually loose because she wore wigs and short skirts, used makeup excessively, and had sex outside of marriage. A respectable woman would avoid cosmetics or use them minimally, eschew wigs, and dress modestly, mirroring an ideal “natural” beauty through self-confidence, social etiquette, and controlled bodily practices (Mougoué Reference Mougoué2016:9–10). The complications are clear in columnist Ruff Wanzie’s 1964 advice regarding facial expressions: a respectable woman smiles just enough to please without being labeled overly social and sexually loose (1964a:4). Further, as in Jehanne Teilhet-Fisk’s study showing the role of local and global influences on transitioning ideas of “natural beauty” in contemporary beauty contests in Polynesia (1996:195), I found disaggregated ideas about the meaning of suitable aesthetic purity in 1960s metropolitan Cameroon.

Newspaper readers and writers as well as the educated urban women I interviewed were a minority of the urban population, and they focused their policing of women’s behaviors on their own demographic. To be specific, rural West Cameroonians outnumbered urbanites by a ratio of 8.4 to 1, and only 9 percent of West Cameroon teenagers (ages fifteen to nineteen) had technical, secondary, or higher education.Footnote 4 While much of this education took place in Nigeria, some individuals were educated in the United Kingdom and United States, reflecting the ties of West Cameroon to Anglophone West Africa and Anglophones globally; the West Cameroon State had few institutes of higher learning and even fewer for women (Elong Reference Elong, Ndlovu-Gatsheni and Mhlanga2013:148–49). Educated Anglophone Cameroonians thus drew from international experiences and cultural knowledge that crossed time and space, to (re)frame ideas about women’s bodily practices and attitudes.

“Foreign and Odd”: Pan-Africanism and “Natural” Black Beauty

In addition to the Anglophone West African culture, Anglophone Cameroon was part of a global 1960s pan-Africanist community that advocated for natural African aesthetics to reclaim cultural identity and racial pride following British rule. As Sarah Banet-Weiser asserts in her examination of how stages of U.S. beauty contests in the 1990s reflect concepts of national identity, “[p]ageants are not only about gender and nation, they are also always (and increasingly visibly) about race and nation” (1999:21–22). These assertions can be applied to 1960s metropolitan Cameroon; the interplay of race and gender, along with ideas circulating locally and globally about racial politics, fostered anxiety about racialized beauty ideals. The “black is beautiful” movement began in the mid-1960s in the United States and spread across the Atlantic. Proponents advocated the celebration of often-stigmatized bodily symbols associated with blackness—dark skin, tightly curled hair, and large behinds—as a way to reclaim black self-esteem (Pinho Reference Pinho2010:76), convey “the spirit of self-love and exuberance,” and “forge a unified black identity” (Craig Reference Craig2002:20, 23). In Cameroon, Ethiopia, Uganda, Malawi, Zambia, Zanzibar, and elsewhere, transatlantic connections and awareness of the racial politics shaping a larger pan-Africanist discourse (Thomas Reference Thomas2006:47; Mougoué Reference Mougoué2016:15) were evident in the condemnations urbanites and leading political figures made in newspaper letters and political speeches (Ivaska Reference Ivaska2002; Hansen Reference Hansen and Allman2004). Wearing miniskirts, wigs, nail polish, or lipstick, or attempting to lighten one’s complexion, came to be understood as racial and cultural betrayal. Under the influence of Christian missionary ideals, these new aesthetic rituals were associated with both Western decadence and immorality and/or lack of Christianity, and seen as a hindrance to black social progress, which was posited as the goal of a unitary black culture (Mougoué Reference Mougoué2016:16).

As the letters examined below suggest, men seemed to be the loudest voices denouncing women’s cosmetic and beauty rituals. Lengthy commentaries by a gentleman in Buea identified as David Benato and a journalist named Tarh serve as the organizational framework that allows us to analytically envision—in the intellectual mindset of the men—how issues of pan-Africanism defined some men’s ideas of authentic black beauty. In May 1969, Benato wrote to the editor of the Cameroon Telegraph and blatantly declared, “There is something seriously wrong with our sense of beauty, or with our standards of beauty.” He explains, “Our women have a very strange notion of beauty. . . They think beauty must be foreign and odd.” He pleads:

Mr. Editor if your “Women’s Page” is going to make a contribution to our culture, then its editor should come back home [metaphorically speaking] . . . coming back home does not mean casting away everything that is foreign. It is important for us to admit that we are all suffering from an inferiority complex. At the same time, we are passing through a period of transition. We must admit that the Whiteman’s educational system brainwashed us to hate even our very selves. That is why we want . . . the white woman’s hairstyles, and the white woman’s hair for wigs. That is why our women want the Whiteman’s red face and complexion . . . white woman’s miniskirts and strange sex ways. And that is why our modern men sit back and pretend to admire these oddities . . . This is the time for our women leaders to come out frankly and boldly to condemn strange makeup and fashion that are foreign to our nature. (Benato Reference Benato1969:7)

Benato identifies specific practices and conduct—“strange sex ways,” for example—as visible markers of “foreign” cultural and racial invasion. Further, by looking to leading female figures, Benato implies the social stratification that informed just who was responsible for disciplining women’s beauty practices. He suggests that women of high social positioning—individuals who most likely had obtained formal education—should play a primary role in monitoring and regulating the behavior and actions of their counterparts.

Two other male journalists made similar cases about women’s beauty practices in their columns. On June 15, 1971, Thomas Tataw Obsenson, the popular journalist of the “Ako-Aya” columns for the Cameroon Outlook during the late 1960s and early 1970s, linked women’s new beauty rituals to racial betrayal. He asserted that women whitened their skins because “Europeans are forming this hatred for our colour for their own purposes. How else can I explain this when many dark Cameroon beauties have suddenly become ‘white’ . . . Let us be proud of our colour and not imitate foolish things” (Ako-Aya Reference Ako-Aya1971). Ako-Aya implies that women mindlessly follow European beauty trends and senselessly change their appearance to fit ongoing western beauty trends, thus making themselves vulnerable to external factors and complicit in buttressing European racist doctrines. The journalist who wrote “Tarh’s Commentary” in the Sunday News, who was simply known as Tarh and sometimes penned part of his columns in Pidgin English, likewise expressed his disdain for skin lightening, saying he had learned of the practice only recently:

I very much believe in nature. . . I have often wondered how some girls who had such beautiful black faces suddenly have such pale faces and in my ignorance, I often blurt out, “How sister, you sick?” and they reply “No, I no sick, why you de’ ask?” . . . Ignorant fool that I am who never takes a hint . . . continues this disastrous conversation. “I de ask because your face change small like person we e sick.” “You no like am?” she asks. “No I no like am because I be like face for person we e sick.” End of smile. A frown spreads on her face. She turns her back on me and walks away. I have never understood why. . . whenever we happen to meet again, they refuse to speak to me . . . I don’t know about the warping of their psychology but it certainly makes them act funny at times. (Tarh Reference Tarh1971:4)

Despite the hilarity of Tarh’s alleged ignorance of skin whitening practices, his anecdote illustrates how men strived to foster social power by disciplining women’s beauty practices publicly on the streets and through print media. Ako-Aya uses terms such as “foolish,” and Tarh references terms such as “sick” to describe women’s use of “strange” beauty products and rituals as hindering black social progress and sullying the image of ideal “natural” black beauty. Tarh’s questioning of the psychological nature of women who engage in such practices further shows how he associates external bodily practices, skin whitening, with internal qualities, feelings of racial shame.

Tarh condemns women’s new hair practices as well. He writes about hair dyeing: “[S]ome women even dye their natural hair . . . I go ahead and ask them why they have dyed their hair. They look at me disgustingly and say ‘that is the colour of my hair!’ [I] can’t tell her that only the other day her hair was black, so I say I am sorry and walk way. Another friend lost.” He shares an exchange about “natural” hair that took place with an African American gentleman one day:

I recall that when Black Americans started to wear their hair natural, one of them was involved in an argument with me and he said it was unnatural for Africans to straighten their hair with a hot steel comb to make it less “kinky.” “Bullshit” I told him as they say in America. If white women can stay under a hair dryer for hours with their hair in rollers so they can put some “kinkiness” into their hair, I see no reason why girls can’t use a hot comb to get some kinkiness out of theirs . . . I wouldn’t approve of anything [other] than hot combs like women processing their hair to be like the Whiteman’s hair. (Tarh Reference Tarh1971:4)

The fact that Tarh disagrees with the black American gentleman about “natural” beauty practices reflects divergent pan-Africanist discourses on suitable racial aesthetics throughout Africa and in the diaspora (see for example: Rooks Reference Rooks1996:3, 6). As Maxine Leeds Craig writes, between 1962 and 1972, African Americans “explicitly and self-consciously reconsidered what being black meant” through orientation toward Africa, through recognition of the beauty of black skin and hair texture, rejecting stigmatizing language, and adopting new names and rituals. But while by 1965 many Black Americans saw straightened hair as an emblem of racial shame (2002:15–16), Tarh implies that the process that women use to achieve the “whiteman look,” rather than the result, delineates the boundaries of racial betrayal. He suggests that a woman might use hot combs to achieve straightened hair, but wearing a wig visibly indicates racial betrayal.

In condemning specific beauty practices that sullied “authentic” black physical attributes, the preceding referenced men engaged in what Shirley Tate terms “anti-racist aesthetics” (2007:303). Although Tate’s work on “anti-racist aesthetics” referenced contemporary black identities in the diaspora, I temporally extend her concept of anti-racist aesthetics to 1960s Anglophone Cameroon. Tate argues that anti-racist aesthetics “is a cultural criticism of a negative black aesthetic”; the ideology emphasizes that black individuals can be “beautiful just as [they] are naturally” (2007:303). From this perspective, men such as Tarh, Benato, and Ako-Aya believed that black women might combat European racist ideologies by mastering an authentic beauty that recaptured black racial pride, on the exterior and interior. Thus, ending the use of “foreign” aesthetic wares such as wigs was one way in which women might contest European racist doctrines. However, as Tate observed, the anti-racist aesthetic position is socially constructed with limited (and problematic) boundaries of definition: “the only authentic black hairstyles would be dreadlocks, afro, cane-row and plaits. By extension, the only authentic blackness would be a dark-skinned one” (2007:303). Similar to their diasporic counterparts, some men described Afros and dark skin—“dark Cameroon beauties” as Ako-Aya framed it—as the “natural” appearance of black African women.

Unsurprisingly, the anti-racist discourse in 1960s urban Anglophone Cameroon was couched within transnational racial politics. It reflected the pan-Africanist struggle to achieve racial pride through exterior bodily practices and emotional, or internal, qualities. Women’s (unapproved) aesthetic practices might increase the internalization of feelings of black racial inferiority generally. Benato opines at length about the historical roots of racial shame among the global black community:

The story began many years ago when white men treated the black man as beasts and tried to justify slavery. As a reaction, Afro-Americans began to imitate white men to aspire to whiteness . . . They have red skins, stretched hair, red lips . . . Is this the standard of beauty we in Africa want to set for ourselves? . . . I am sure many of our women indulge in these strange beauty ideas ignorantly. If they know the origin, they will really come back home . . . We abuse our Creator when we commit such distortion on our persons [bodies]. I should like to know what the Church and religion say about these distortions . . . Let us do something to save our Afro-American colleagues who are now fighting for selfhood, manhood, and equal rights. (1969)

Benato ties African women’s endeavors to achieve standards of beauty based on white norms to the history of slavery in the United States and to feelings of self-hatred. He blames beauty rituals of both black Americans and Africans for the disintegration of black pride. He invokes “the civil rights movement that was raging in the United States at the time to suggest that West Cameroonian women and men must also regain their personhood and black pride” (Mougoué Reference Mougoué2016:18). Through the practice of approved “authentic” beauty practices, natural black beauty would inform higher racial self-esteem and, in the words of Ako-Aya, encourage Cameroonians to be “proud of [their] colour” (1971).

But, while anti-racist aesthetics are about recapturing black aesthetic pride, the different suggested practices women can engage in to capture and preserve this pride are complex and reveal much about the socially constructed nature of authenticity. Marc Epprecht’s treatment of sexuality in postcolonial Africa discusses the concept of “un-Africanness.” He argues that the notion has evolved because of colonial rule and political and cultural nationalism. What it means to be authentically African often repeats colonial stereotypes about Africans (2008). Benato’s statements and those of Ako-Aya and Tarh suggest their acceptance of discriminatory factors shaping (African) black authenticity. While such men condemn women’s new beauty practices, they simultaneously refashion, or remake, new contradictory ideas about “natural” beauty. Benato invokes religion as the barometer for moral responsibility— “the Church” as he states it—reflecting the Christian undertones of aspects of pan-Africanist discourse. In an earlier presented excerpt, he acknowledges that Cameroonian cultures are changing, yet he limits beauty ideals to forms that eschew perceived cultural betrayal. He foregoes calls for “casting away everything that is foreign” but calls on advice columnists to condemn “strange makeup and fashion” that are “foreign” (1969:7) to Cameroonian cultures while simultaneously embracing Christianity as an emblem of African authenticity.

The fact that men’s voices were the loudest in denouncing women’s beauty rituals reveals the masculinist domination of pan-Africanist discourse in the mid twentieth-century. Benato, for instance, feels that his role is to enlighten women on the origin of their beauty practices. He presumes that women beautify themselves for men only, and that the male voice therefore has the only authority on how women should beautify themselves. He candidly claims men have failed to discipline women’s beauty practices: “We men have taken too long to tell some of our women that most of them [who use] makeup and who think they are fashionable look like masquerades. . . Many men see nothing beautiful or normal about a woman who comes along with stretched hair” (1969:7). The preceding statements revealed what other scholars have identified as a masculinist Pan-Africanist discourse designed “to restore masculine pride, power, and self determination to black men” (Reddock Reference Reddock2014:66). As Ashley Farmer asserts, the pan-Africanist agenda of the period was rife with “patriarchal interpretations of black nationalist ideologies” (2017:11–12). The male-dominated rhetoric that Benato employed emphasized black women’s subordination by encouraging submission to male authority in order to “prevent the degeneration of African cultural identity, and” thereby black pride and culture worldwide (Mougoué Reference Mougoué2016:18–19). Yet, as the next section shows, some viewed beauty practices more moderately than Benato, who calls them “strange.” His lamentation that women don excessive cosmetics foreshadows how some individuals sought to discipline women’s excessive beauty practices by curbing them.

“A Pole-Cat-Like-Odour”: Disciplining Excessive Bodily Practices

While some men tied ideas about authentic black beauty to pan-Africanism, some women, such as columnist Ruff Wanzie, tied issues of natural beauty to disciplined behavior and bodily practices that were not excessive but respectably moderate. By highlighting issues of jovial demeanor and olfactory preferences, this section probes how such individuals shaped ideas about the proper instantiation of the moral hygienic ideal and aesthetic purity. But the judicious economics buttressing issues of “natural beauty” illuminates how they (re)defined proper ethical systems to integrate women’s changing experiences with consumer culture and new beauty practices.

Ruff Wanzie believed that a woman’s controlled jovial comportment in social gatherings and in public spaces reflected a naturalness and beauty beyond the use of cosmetics. She cautioned women against being too forthright and extroverted, thus calling on women to curb excessive bodily practices to preserve respectability; overly extroverted women would be labeled sexually loose. Wanzie cautioned readers in April 1964, “[w]hen a woman is social and smiles to all for courtesy’s sake, people will always misinterpret her for a loose woman” (1964a:4). In the same month, she wrote that the “expression on a woman’s face is more important than the clothes she wears . . . A smile says, ‘I like you very much. You make me happy. I am glad to see you.’ The smile should be a real smile that comes from within . . . Preserve a right mental attitude of courage, frankness, and good cheer.” A proper Cameroonian woman, Wanzie writes, is never too occupied to display appropriate conduct by remembering the names of acquaintances: “Remember the wise saying of the ancient Chinese which says, ‘A man without a smiling face must not open a shop.’ A simple way to make a good impression is to SMILE, and people will like you.” Instead of arguing for cosmetics, Wanzie encourages women to look within themselves when in public; this larger rhetorical symbolism exemplifies how inner qualities, such as a proper mental attitude—as she says, “[t]hought is supreme”—might reflect a women’s appropriate bodily disposition (1964b:5). She invokes a Chinese saying to make her case. In doing so, she draws from her formal educational background and social positioning—as a teacher in the Catholic Primary School in Victoria and as a freelance journalist for the Cameroon Times—to bolster her authority (interview with Simon Dikuba by Eileen Manka Tabuwe, Buea, June 17, 2016). Yet, she seeks to empower her female counterparts by encouraging them to garner satisfaction in the power of their demeanor and appearance while adhering to what she believes are dominant societal expectations that African women show restrained public behavior. Thus, Wanzie endeavors to empower women within perceived established boundaries of Cameroonian femininity and conventional hetero-feminine ways, urging women to restrain excessive bodily practices.

A 1964 letter to the women’s column at the Cameroon Times likewise warns against women’s exorbitant bodily practices by targeting excessive smiling and the (moral) hygiene ideal: “When women smile broadly they kill. [But] [d]o they really kill? What makes men’s heart leap to their throats when a woman smiles? Everybody, as far as I have seen, appreciates smiles from those whose teeth are very neatly kept” (Muma Reference Muma1964:3). The writer was a reader identified as Celtus Muma, based in Bafut, a town in Anglophone Cameroon’s Northwest Region. He called for dental hygiene, stating, “Dirty teeth cause tooth ache… and awful mouth odour. . . Whoever keeps his or her teeth dirty should be ashamed.” Muma calls on readers to look to “the chemists and the hospitals” for drugs to cure body odor. While these criticisms are gender neutral, he also opines, “[s]ome women pride themselves with wearing very neat external dresses but they have very dirty underwears. Women should keep their underwears very neat always.” Muma’s comments illuminate how ideas about cleanliness can be moralized into a particular brand of purity. His focus on the figurative and symbolic appearance of dirt suggested the internal and external qualities of culturally constructed forms of feminine aesthetic purity. Mary Douglas asserts that because uncleanliness suggests a disruption of order—“matter out of place”—it is symbolic, implying both the existence and the contravention of an established order or system. Thus, dirt and its lack denote social status and social order. Accordingly, if “dirt is essentially disorder,” and, if the movement to eliminate dirt is really about “re-ordering our environment” (Douglas Reference Douglas1966:2–3), monitoring women’s “dirty” bodily practices was one way to regulate “bad” women who challenged dominant gendered behavior and strayed beyond the perceived boundaries of feminine respectability. As Dorothy Hodgson and Sheryl McCurdy assert in their work on twentieth-century African women who challenge gender boundaries: “Many women are labeled ‘wicked’ because they . . . directly or indirectly challenge normative expectations of ‘respectability’; they are no longer the ‘good’ wives or daughters they are supposed to be” (2001:6). The absence of dirt—literally and figuratively—reflected, from Muma’s perspective, an honest, natural, and respectable woman who did not challenge dominant gender norms and social relations.

Muma’s proposal that Cameroonians purchase toiletries to combat foul body odor elucidates the economic underpinnings of “mastering” “natural” bodily practices. Cameroon opened the country’s economy to international market forces, private-sector development, and an influx of European/foreign import, which no doubt included toiletries and various beauty products, in the early decades of independence (Tesi 2017:50–52, 64–65, 67–70). Muma’s advice commodifies women’s struggles as resolvable by using such consumer products even as he emphasizes local understandings of hygienic practices. While suggesting that women consult chemists most Cameroonians would not have been able to afford, he also suggests, “[t]here are chewing sticks cheaply sold everywhere, and I see no reason why both men and women should keep their teeth dirty” (1964:3). Chewing sticks—twigs from the tree Salvadora Persica—are a traditional West African means to clean teeth, freshen the breath, and ultimately prevent tooth decay and gum disease. By encouraging women to purchase products from chemists and to visit hospitals to cure systemic causes of body odor, he promotes hybrid hygienic practices that underlie the economics of beauty practices. That he does not suggest the use of soap and water, as was emphasized during the ferment of Christian missionary education during European rule (Burke Reference Burke1996:170), reveals the temporal changes in attitudes about proper bodily practices.

A vehement letter by a woman in Victoria responding to Muma questioned his focus on women’s bodily practices. The reader, who identifies herself as Esther Nkongho, described Muma as “out of his senses at the time he was writing his article” (1964:3). She castigates him for suggesting that “only women’s breaths stink.” “If he says so then he is so mistaken for some girls and even fellow men cannot withstand the breaths that come out of some men’s mouths.” She likewise counters his description of women’s dirty underwear with men’s “practices of wearing a clean nylon shirt out with a torn or dirty or brown singlet underneath,” saying that she will bring him “back home,” meaning to reality, to recognize this. She concludes, “both sexes are victims of these dirty practices, and his article should have reflected both sexes and not only women.” Nkongho implies that Muma’s letter is based on self-aggrandizing and own-sex-aggrandizing fantasies. She accuses him of holding only women to standards of cleanliness. Simultaneously, she agrees with Muma that cleanliness is necessary and amounts to more than what appears on the surface. However, most columnists and letter writers writing about hygiene focused on women, as the following analysis evinces.

Female journalists’ statements about women’s body odor and the use of perfumes similarly revealed much about excessiveness, gender norms, and the economic stratification of achieving fabricated ideas of “natural” beauty. As Constance Classen, David Howes, and Anthony Synnott assert, “olfactory preferences and aversions tend to take root deep in the human psyche, [such that] evoking or manipulating odor values is a common and effective means of generating and maintaining social hierarchies . . . Such olfactory social codes often pass unnoticed by us, for they tend to function below the surface of conscious thought.” Thus, toiletries such as perfumes, as materials inscribed on the body, can be “a political vehicle or a medium for the expression of class allegiances and struggles.” As they point out, “[w]hile men are allowed to smell sweaty and unpleasant without losing any of their masculine identity, women who don’t smell sweet are traitors to the ideal of femininity and objects of disgust” (1994:8, 161, 164).

Ruff Wanzie certainly believed that women needed to prioritize what Classen, Howes, and Synnott phrase as “ideal olfactory image” (1994:8) to please their husbands. In an April 1966 column in the Cameroon Times, she counsels, “lasting marriage happiness depends largely upon honesty, and attractive figure, work, [and] cleanliness as from the start [of the marriage]” (Wanzie Reference Wanzie1966:3). She cautions her readers,

Any woman who seeks appeal in the eyes of the man who loves her must take care not to offend his visual, olfactory, hearing and touch sense always. When a man hears the sweet melodious voices of his wife, touches the smooth well-kept body and sniffs the rose perfume [on] his wife, he becomes naturally aroused and stimulated but when he sniffs her and her body odour is offensive, he feels disgusted or repelled. Women must insist on personal neatness of all parts of the body always so as to maintain that first impression as from [the] start. (1966)

Proclaiming that “[c]leanliness is the well-known feminine charm and therefore must be maintained by all women,” Wanzie recommends “rose smelling scents” as “suitable for women” but cautions “they are not used as camouflage but to supplement [a] clean appearance” (3). Undeniably, cleanliness was central to Wanzie’s views on femininity. To Wanzie, bodily cleanliness is an allure, or magnetism, that keeps a husband physically attracted to his wife and therefore content in his marriage. Perfumes, therefore, must not mask unhygienic practices and “dirty” bodily practices. Within this context, Wanzie extends ideas of dirt and hygiene to include fabricated ideas about gender norms, and, in this case, how a woman’s body “naturally” smells. To Wanzie, cleanliness is about more than being free from dirt or stains. By smelling good, her female readers showed their cleanliness both internally (through sound and virtuous minds) and externally (through good conduct), thus upholding respectable behavior and bodily practices.

A woman who overused beauty products, by contrast, would be criticized in women’s advice columns. In her September 1968 column in the women’s advice section of the Cameroon Voice, journalist Cecila Mengot cautions against transgressing cultural definitions of the clean, proper, and “natural” state of a woman’s body. She writes, “Nature has not been a fool to impart the knowledge of making up [using cosmetics], and it’s really fair to have this knowledge being put into a positive use and not to make nature regret his imparting into us such a gift” (1968:3). She criticizes “the way our flappers, mothers, sisters and aunts do in the field of make-up.” Mengot explains: “before they leave the shops or markets they [women] must have spent about three hundred francs in buying their dearly loved perfumes. Normally it’s factual that perfumes are to be used. But when the perfume is used in an improper way it creates a second meaning for itself.” She instructs:

Perfumes are, for one to sprinkle on either clothes, rub in the armpits in order to attain sweet smell, but when one takes it as a point of rubbing then, it would mean that the person in particular would have had a second definition, like having a pole-cat-like-odour being the reason of the lady or girl in particular using the said [perfume], in such an improper way. Therefore, dear women folks let’s avoid the way of using perfume in an improper manner in order that we should not be labeled with unpleasant titles which we don’t deserve. Hullo, ladies project your beauty by yielding to useful advices. (1968)

Mengot’s advocation for sensible perfume use supports Classen, Howes, and Synnott’s assertions that “deodorants suppress unwanted odours while perfumes and colognes allow for the creation of an ideal olfactory image” (1994:8). Excessive perfume use would mar this ideal olfactory image, violating codes of nature and the “natural” state of a woman’s body. In this manner, Mengot emphasizes that heavy perfume use signifies the devaluing of nature and in turn the devaluing of the natural body. Thus, while a woman should use perfume to enhance her natural state and beauty, it goes against the understanding of the natural state of a woman’s body if she uses it excessively. Ultimately, although Mengot advises women to purchase body care products—just as Wanzie and Muma did—she presses them to limit their use so as not to blemish their “natural” bodies and to avoid social stigma.

Mengot’s use of the words “polecat” and “flapper” demonstrates an understanding of Western metaphors and imageries about gendered cleanliness and bodily practices and behavior. Contrary to the use of the term in North America and Western Europe, in 1960s urban Anglophone Cameroon, “flapper” was synonymous with the phrase “free woman”; flappers were not historical, but contemporary figures—single women, or “free women,” who were sexually loose and challenged gender norms. The word “polecats”—another word for skunks—was long a slang term, in British literature, for women, or prostitutes, drenched in cheap perfume and presumed to be lecherous “because of their rank smell” (Damrosch Reference Damrosch1999:614). Thus, Mengot suggests that heavy perfume use signifies sexual looseness and an improper femininity that contravenes sexual norms. However, as the following section shows, the historicization of the local term “nyanga” demonstrates that women exercised agency and took pleasure in engaging in new bodily practices, albeit circulating negative stereotypes about some beauty practices.

Nyanga: Pleasure Politics and Agency

Oral evidence suggests that urban Anglophone Cameroonians believed that the traits defining inner beauty—self-confidence, good self-esteem, and suitable bodily comportment—reflected a natural, modest, and respectable outer beauty, signaling to the world the social and economic progression of Cameroonian elite subcultures and hybrid understandings and agency of defining natural beauty. Equally important, women expressed pleasure when engaging with new beauty rituals, simultaneously exerting and shaping their own ideas of beauty standards, similar to their diasporic and continental counterparts. For instance, Noliwe Rooks concludes that throughout history, African American women have exerted agency in defining their own beauty ideals, rather than being passive consumers of beauty products and marketing; they “constructed identities for and meanings about their own bodies” (1996:15). In his examination of the Spring Queen festival in Cape Town, South Africa, from the 1970s to 2005, Peter Alegi similarly observes that black contestants were not “passive dupes,” concluding that the event “provided a rare opportunity for factory women to publicly assert their human dignity, enhance their self-esteem, and claim equal rights as women and workers.” He documents their reports of “‘fun,’ camaraderie, and pride” in competing to be Spring Queen (2008:32–33).

Women exerted agency in shaping beauty standards against a hybrid Anglophone Cameroonian culture. The British Southern Cameroons were administered from Nigeria until 1954, and the legacy was a blended Anglophone Cameroonian culture in the 1960s, shaped and defined by the cultural, language, and political values hailing from both Nigeria and Britain and by the legacy of Christian missionary activities (Mougoué Reference Mougoué2017:408). Individuals educated in Nigeria learned indigenous Nigerian languages—including Hausa, Ibo, and Yoruba—and adopted colloquial Nigerian Pidgin English terms, slangs, and expressions (Todd Reference Todd1982:88). While Pidgin English emerged on the Cameroon coast as the language of commerce and lingua franca during the Atlantic Slave Trade (1400–1800), many lexical terms derived from indigenous languages in neighboring Nigeria persisted in Anglophone Cameroon, among them “nyanga,” meaning stylishness, beauty, elegance, and coquetries (Nkengasong Reference Nkengasong2016:33).

Several women I interviewed, many of whom were in their late teens and early twenties in the 1960s, explained that various aesthetic and bodily rituals were “nyanga.” When I interviewed her at her home in Buea, Fidelia Ngum, at the time in her late fifties, told me, “Women used an iron comb to straighten their hair because the hair would become relaxed . . . These are the things we did to look nyanga” (interview, Buea, November 4, 2011). While scholars debate the multiple Bantu origins of the word nyanga, scholarship mostly suggests it emerged in English-speaking Cameroonian towns in the 1960s and derives from a Hausa word meaning “finery” and “decorations.”Footnote 5 Cameroonians have widened its semantic field, using it to mean “putting on airs and graces,” “dressing up,” “pretending to be better off than one is,” “bragging,” “showing off,” or having too much confidence in one’s elegance (Nchare Reference Nchare2017; Todd Reference Todd1982:122). This gives the word a suggested element of social and economic mobility—much like kfaang—facilitating the opportunity to traverse social and aesthetic boundaries through either respectable or disrespectable bodily practices. Thus, nyanga also has negative connotations. For instance, my interviewees in Buea differentiated between “good” and “bad” nyanga based on public comportment, social etiquette, self-confidence, and other potentially unsuitable dispositions. In her late fifties, Annie Kamani, my research assistant in 2011 and 2015 and based in Buea since the 1960s, told me that sitting immodestly was nyanga in a negative sense (interview, Buea, August 1, 2015). Thus, excessive cosmetic use might be “bad” nyanga.

Notwithstanding nuances in understanding of nyanga, interviewees clearly sought agency and pleasure in making their own nyanga. Fidelia Ngum recalled that women did nyanga to stay up to par with fashion and with each other: “If woman did not follow fashion, it was her problem. No one would force you. But people would say, ‘this one is not really [she shook her head disapprovingly to visually demonstrate people’s reactions of the time] . . . look at her hair . . . she is not putting on what others are putting.’ To look sharp, [women] must follow others’ [model]” (interview, Buea, November 4, 2011). Fidelia underscored her agency and pleasure in engaging in nyanga; she describes the impact of hair products and cosmetics thus: “You feel so happy and happy. I was modern because I was beautiful. I . . . felt beautiful. I used product in my hair, hold it, style[d] it, make-up myself.” Nyanga would continue to be part of the vast circulating repertoire of global, continental, national, and local lexicons from which Anglophone urbanites such as Fidelia would draw to shape discourse and rhetoric about beauty and bodily practices and performances in the 1960s. Interviewees used the term to express their agency and pleasure in engaging in new bodily practices and attitudes even as they acknowledged limitations on their behavior.

Conclusion

Women’s experiences with newly constructed bodily practices and attitudes reveal emergent ideas about cosmopolitan African womanhood in Cameroon during the 1960s, an era of strong Anglophone Cameroonian nationalism characterized by women’s increasing access to formal education and formal employment. Formally-educated Christian urbanites, such as freelance female journalists and male letter writers, sought to discipline women’s bodily practices and emotional expressivity in endeavors to regulate the boundaries of perceived feminine respectability and to define a woman’s “natural” beauty within a metropolitan setting. Drawing from past/contemporary and global/local influences about bodily practices, they described a “natural,” or “pure,” black African aesthetic that reflected both disciplined internal qualities, such as an appropriate level of emotional confidence, and external merits relating to bodily practices and decorum. Not all individuals agreed on what defined “natural” black beauty. Female journalists called for moderate beauty practices while men mostly condemned Western-originated practices, framing their disapproval in the pan-Africanist discourse.

While nyanga continues to signify stylishness and too much stylishness, the word has evolved to encompass a variety of meanings related to style in present-day Cameroon. It has traversed Anglo-Franco linguistic boundaries, reflecting the blended nature of Cameroonian identities. In the mid-1970s, after federalism was dissolved and Cameroon became a unitary republic, Franglais, or Camfranglais, became a common lingua franca in urban areas where English and French speakers lived (DeLancey, Mbuh & DeLancey Reference DeLancey, Mbuh and DeLancey2010:181–82). Nyanga survived this transition and became the name of a contemporary Francophone Cameroonian magazine. The magazine advertises itself as the magazine for “100% Cameroonians” and aims to celebrate success and promote excellence. It covers humanitarian, political, and cultural topics, and likewise highlights lifestyle trends and advertises fashion trends such as shoes, purses, cell phone covers, and various accessories. Clearly, understandings of nyanga now extend to knowledge of global politics and humanitarianism while simultaneously continuing to emphasize the importance of keeping up with aesthetic trends. In this manner, Cameroonians continue to reframe nuances in understandings of beauty and bodily practices in modern-day Cameroon, thus continuing to refashion Cameroonian identity in a postcolonial, changing world.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the following individuals for their comments and feedback on earlier drafts of this article: the organizers and participants of the summer school and international conference, Politics of Beauty: Discourses and Intersections in the Global Sphere, that took place at the University of Cambridge in 2016; special thanks to Shirley Tate and Sarah Banet-Weiser for their additional and detailed feedback on the work. I also thank the Baylor philosophy writing group, the anonymous reviewers of this article, and Benjamin N. Lawrance.