Introduction

Alderney, a small island in the Channel Islands, located 60 miles from England and 8 miles from France (Figure 1), has a long history of military activity and occupation. However, it was its occupation by the Germans during World War II (WWII) which had the most dramatic impact on its landscape and population. In June 1940, the British government decided it could no longer defend Alderney and the island's 1500 residents were evacuated to mainland Britain (Sanders, Reference Sanders2005). In July 1940, the island was occupied by German forces. For Adolf Hitler, Alderney represented a strategically advantageous position; it was a possible vantage point from which to invade Britain and it later became part of the Atlantic Wall (Forty, Reference Forty1999; Bonnard, Reference Bonnard2013).

Figure 1. Map showing the location of Alderney in relation to Britain, France and the other Channel Islands.

To facilitate the large-scale construction of fortifications, thousands of workers were sent to Alderney. While some worked for Organisation Todt (OT, a German civil and military engineering group) and were paid for their services, the majority were forced and slave labourers transported from concentration and labour camps throughout Europe (Pantcheff, Reference Pantcheff1981; Carr & Sturdy Colls, Reference Carr and Sturdy Colls2016). Between 1941 and 1945, around 6000 labourers were sent to the island (numbers reviewed in Sturdy Colls & Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsforthcoming). The German garrison, which consisted of the army, navy, air force, and, later, SS guards, totalled more than 3000 by 1944 (Pantcheff, Reference Pantcheff1981; Davenport, Reference Davenport2003). Hundreds of bunkers, trenches, gun emplacements, personnel shelters, anti-tank walls and obstacles, tunnels, and other fortifications were built by these labourers over this short period.

Purpose-built camps were constructed to house most of the workers, the main four being Sylt, Norderney, Helgoland, and Borkum, named after German Frisian islands. These camps were initially overseen by OT and the prisoners were guarded by Wehrmacht soldiers. Later, in March 1943, Sylt became an SS concentration camp and an official sub-camp of the Neuengamme concentration camp in Germany. Sylt housed around 1000 political prisoners sent from Neuengamme and Sachsenhausen concentration camps and assigned to SS Baubrigade (Building Brigade) I (Figure 2). Existing buildings, such as evacuated houses and military forts, were also taken over for the purposes of internment and to house the German garrison. The appalling living and working conditions, beatings, torture, and ill-treatment resulted in the deaths of an unknown number of workers (most of whom were housed in Sylt, Norderney, and Helgoland camps); official records indicate that around 400 people died, but witness testimonies and archaeological evidence suggest this number should be around 700 (Bunting, Reference Bunting1995; Sturdy Colls & Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls, Colls, Ch'ng, Gaffney and Chapman2014, and Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsforthcoming). In the absence of source material and detailed investigations, many of the individuals sent to Alderney remain anonymous and their experiences poorly documented.

Figure 2. Map showing the main locations of marks discussed and other key sites used during the German occupation.

In 2010, an archaeological project was launched, its aim being to locate and record sites connected to the German occupation in Alderney, especially sites connected to forced and slave labour. The project succeeded in observing an abundance of mark-making practices (results outlined in Sturdy Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls2012, Reference Sturdy Colls2015, Reference Sturdy Colls and Dziuban2017; Sturdy Colls & Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls, Colls, Ch'ng, Gaffney and Chapman2014, and Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsforthcoming). From 2014 to 2017, a survey was undertaken to record this complex range of engravings, marks, drawings, paintings, and impressions. It revealed that the workers and their overseers left behind a complex body of markings that attest to their existence on the island.

This article outlines the results of this survey and considers the contribution that such marks can make to our knowledge about the events of the Nazi occupation. The various ways it can be used to recall individual and collective experiences will be discussed and the role of this evidence in providing an alternative form of identification and proof of life will also be explored.

Literature Review

Studies of mark-making practices

Historical mark-making practices have been documented by archaeologists in domestic, industrial, and conflict settings. In settings as diverse as Pleistocene rock art from Indonesia (Aubert et al., Reference Aubert, Brumm, Ramli, Sutikna, Saptomo and Hakim2014), Native American rock art (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Drummond and Russ1998), the Classical world (Baird & Taylor, Reference Baird and Taylor2011), or Japanese internment camps (Burton & Farrell, Reference Burton, Farrell, Mytum and Carr2012), archaeologists have used the analysis of marks as an important means to investigate past peoples. Studies in contemporary archaeology have been quick to embrace its potential to aid our understanding of society. As Frederick and Clarke (Reference Frederick and Clarke2014: 54) have observed, ‘records of presence, protest, politics and place, all sorts of mark-making practices are part of our everyday spaces of work, leisure, home and travel’. Mark-making may include any writing, impression, motif, and/or drawing recorded onto or within a surface as a result of both sanctioned or illicit activities. Sanctioned marks could include operational instructions and/or descriptions together with military motifs, slogans, or artwork (Cocroft et al., Reference Cocroft, Devlin, Schofield and Thomas2006). Illicit marks include graffiti, which could include names, numbers, symbols, drawings, slogans, artwork, instructions, and a variety of other mark types. The line between sanctioned and illicit graffiti may not always be clear to the observer unless the permission status is known (Daniell, Reference Daniell2011). Additionally, scholars have moved beyond the negative connotation of graffiti creation as the illicit daubing of public or private spaces, towards an understanding of its value as an ethnographic source (Daniell, Reference Daniell2011).

Much of the literature and research concentrates on using marks to understand the types of individuals occupying a site and reasons for mark creation (Giles & Giles, Reference Giles, Giles, Oliver and Neal2010; Lennon, Reference Lennon and Ross2016). Occupational policies and practices of specific historical societies have also been a focus (Merrill & Hack, Reference Merrill and Hack2013), often demonstrating that a range of individuals occupied sites over specific periods. Research has also been directed at obtaining anthropological details, such as measuring the size and shape of hand sprays (Mackie, Reference Mackie2015) and stencils (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Hall, Randolph-Quinney and Sinclair2017) to determine an individual's age and/or sex on Palaeolithic rock art. Additionally, fingerprint (Králík & Nejman, Reference Králík and Nejman2007), palm print (Åström, Reference Åström2007), footprint (Roberts, Reference Roberts2010), and footwear impressions (Bennett & Morse, Reference Bennett and Morse2014) on artefacts or material surfaces have been explored as proof of existence and/or to gain intelligence about those involved in an object's creation. Regarding contemporary conflict, scholars from a wide range of disciplines have begun to analyse the role that mark-making has played in military activities, protest, and resistance (e.g. Ismail, Reference Ismail2011; Merrill & Hack, Reference Merrill and Hack2013; Drollinger et al., Reference Drollinger, Falvey and Beck2015; Taş, Reference Taş2017).

The literature about marks as a medium to prove and authenticate the identity of its author is limited, most probably because information and detail about the markings’ author is missing. However, some studies have been successful when it was military personnel or prison inmates who left the markings. Excavations of the WWI Larkhill training trenches on Salisbury Plain have uncovered graffiti carved into chalk tunnel entrances, detailing the names, service numbers, and unit details of individual soldiers (Brown, Reference Brown2017). The level of detail provided in the carvings has enabled researchers to trace these soldiers to enrolment lists in Australia through service records held by the Australian War Memorial. Some scholars have focused specifically on mark-making dating to the Holocaust and oppression during WWII, most notably from Gestapo prisons and camps (Huiskes, Reference Huiskes1983; Czarnecki, Reference Czarnecki1989; Myers, Reference Myers2008; Jung, Reference Jung2013). Markings made during periods of incarceration (Casella, Reference Casella, Beisaw and Gibb2009, Reference Casella2014; McAtackney, Reference McAtackney2011, Reference McAtackney2014, Reference McAtackney2016; Agutter, Reference Agutter2014), quarantine, and marginalisation (Bashford et al., Reference Bashford, Hobbins, Clarke and Frederick2016; Hobbins et al., Reference Hobbins, Frederick and Clarke2016) have also been examined in terms of their potential to identify individuals but also as a means of demonstrating emotions and assertions of identity. These approaches are an important advance in archaeological interpretation, suggesting new ways to identify individuals, trace their origin, and map their story during times of conflict. In the context of this investigation, the authors used similar approaches to categorize the types of marks encountered in Alderney, interpret the reason for their creation, and outline the information gathered about the individuals who made the marks.

History of occupation on Alderney

Except for the work outlined here, no current literature relating to Alderney's occupation focuses on mark-making practices. Instead, the literature concentrates on the fortifications that were built or altered on the island, discussing their structural development and history before, during, and after the German occupation (Kendrick, Reference Kendrick1928; Migeod, Reference Migeod1934; Davenport, Reference Davenport2003; Gillings, Reference Gillings2009; Driscoll, Reference Driscoll2010; Monaghan, Reference Monaghan2011; Stephenson, Reference Stephenson2013). Less attention has been paid to the experiences of those who were imprisoned and forced to build these installations, or of the garrison who were stationed there (Sturdy Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls2015). The camps that housed the labourers have also often been omitted or mentioned only briefly in these military-focused publications. That is not to say that there have been no publications about the German occupation of Alderney. Alongside books that have centred on providing an ‘official history of the Occupation’, in which the labourers are again mentioned only briefly (Cruikshank, Reference Cruikshank1975), a body of literature has developed in opposition to this, in an attempt to raise awareness of forgotten aspects. This literature ranges from an account by one of the leading post-liberation British investigators on Alderney (Pantcheff, Reference Pantcheff1981) to accounts by or about survivors (Packe & Dreyfus, Reference Packe and Dreyfus1990; Bonnard, Reference Bonnard2013), and rather more sensationalist accounts that have sought to liken the events in Alderney to those that took place at death camps in Europe (Steckoll, Reference Steckoll1982; Freeman-Keel, Reference Freeman-Keel1995). Others have followed a rather more academic approach by reviewing the available documents and/or undertaking archaeological research connected to the labourers' experiences and perpetrators’ actions (Sanders, Reference Sanders2005; Carr, Reference Carr2010; Sturdy Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls2012; Sturdy Colls & Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls, Colls, Ch'ng, Gaffney and Chapman2014, and Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsforthcoming). In particular, the Alderney Archaeology and Heritage Project has sought to locate and document the surviving fortifications, camps, and other sites connected to the occupation to provide new information about the people who were sent to the island and the role that architecture played in their daily lives (Sturdy Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls2012, Reference Sturdy Colls2015; Sturdy Colls & Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls, Colls, Ch'ng, Gaffney and Chapman2014, and Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsforthcoming).

Methodology

Drawing on existing works on mark-making practices and inspired by the rarity of investigations into the forced and slave labourers sent to Alderney, the aim of the survey described here was to record surviving marks (Table 1) on or within archaeological features on the island and to examine their uses for interpreting the history of Alderney's occupation. To achieve this, a non-invasive, interdisciplinary method was developed to systematically search key strongholds and military installations identified on the island (Figure 2). These areas were selected on the basis of archive studies, the perceived potential for marks to survive, and accessibility.

Table 1. Marks recorded on Alderney, classified by content.

A systematic walkover survey was undertaken, in accordance with guidelines outlined by the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists (2014a), across the pre-defined survey areas shown in Figure 2. Based on an initial desk-based assessment (Chartered Institute for Archaeologists, 2014b) and previous research visits, bespoke surveying forms were devised using Fieldtrip GB (EDINA, 2014), a mobile mapping and data collection tool selected because of its ability to facilitate recording of feature characteristics, spatial and positional information, and photographs of the marks identified during the walkover survey.Footnote 1

Desk-based research was subsequently undertaken to identify the origins and possible meanings of the marks. With regard to the occupation-era marks, this involved the analysis of archive documents, photographs and testimony, and searches of Holocaust-era victim lists, missing persons records, and military archives to gather more information about the people whose names were recorded.

The main sources used were:

– the database of Gedenkstätte KZ-Neuengamme (Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial), the parent camp of the SS concentration camp Sylt where records connected to the transfer and deaths of SS prisoners were housed

– the International Tracing Service (ITS) Archive, the largest archive of records relating to Holocaust victims and survivors, based on enquiries filed by individuals and family members after WWII

– the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) Holocaust Survivors and Victims Resource Center Database (HSVRCD), a database containing survivor and victim records from numerous Holocaust-era camps and wartime and post-war archives

– numerous other archive materials connected to the OT and SS labour programmes.

Results

Overview

From the nine locations surveyed during this study (Figure 2), twelve categories of mark-making were identified (Table 1) and 371 individual examples of mark-making were observed. As some examples included multiple types of content, e.g. writings, drawings, symbology, etc., 463 different marks were documented in total (Table 1). Of these, the most common marks were writings (n = 154), diagrams, pictures and artworks (n = 76), room/building labels (n = 59), and names (n = 49). As Figure 3 shows, engraving was the most common means of mark creation (n = 208), particularly among the marks that could be attributed to the forced and slave labourers. While pencil and stencil marks were most common with regard to more recent graffiti and military marks, not all the marks could be conclusively dated. Those that had datable evidence illustrate mark-making practices before, during and after WWII. Given the focus of this article, only examples that are likely to date to the occupation period or which could be associated with incarceration are discussed here.

Figure 3. Method and proportion of mark creation identified on Alderney (n = 463).

Names

The survey revealed forty-nine names located on a range of fortifications on Alderney. The largest name clusters were found at Fort Grosnez (Figures 4a to c) and Fort Albert (Figure 4d), with other individual examples within additional bunkers and fortifications (Figures 4e and f). Other engravings, likely to be names, were also found at Fort Albert, although these proved difficult to decipher as they were predominantly etched into brick.

Figure 4. Examples showing the dates, names, and/or initials recorded during the surveys in Fort Grosnez (a–c), Fort Albert (d), and Frying Pan Battery (e–f).

Most of the recorded name-based graffiti was found at Fort Grosnez and was written in the Cyrillic alphabet. It is known from historical sources and testimonies that many workers sent to Alderney were from Russia, Ukraine, and other Eastern European territories (The National Archive, TNA, HO144/22237). Therefore, it seemed likely that these names belonged to forced or slave labourers. This was confirmed by further research in the archives outlined below.

At Fort Grosnez, three of the engravings were probably created by the same person, given the similarity in the text style and the commonalities in the inscriptions. The first read ‘Коля Михайленко' (Kolia Michailenko), the second ‘Михайленко [Michailenko] 1944’ (Figure 4a) and the third ‘Николай’ (Nikolai), the full name for which Kolia is a short version.

Three Nikolai Michailenko appear on transport lists at Neuengamme concentration camp, but none appear on any of the few known lists of transports to Alderney. As it is possible that these documents could have been destroyed, known transport routes to camps were examined by searching the ITS and HSVRCD to determine whether any of these three individuals could have been sent to the island. One Nikolai Michailenko appears to be the most likely person to have been on Alderney. From July 1942 until February 1943, he was in a sub-camp of Buchenwald called Halle before being transferred to Neuengamme. This places him in Neuengamme just before the transfer of SS Baubrigade I prisoners to Alderney. There are no further records of his whereabouts until he was re-registered at Neuengamme and then Buchenwald in August 1944. Therefore, a gap exists in which he could feasibly have been sent to Alderney. The dates of his presence in Neuengamme at either end of this period coincide with known transports to and from Alderney, and transfers to Buchenwald from Alderney were common. Whichever Nikolai Michailenko made the inscription, the fact that his name appears in the Neuengamme database means he would have been an inmate at the SS concentration camp of Sylt and a member of the SS Baubrigade I, as opposed to a labourer in one of the OT camps.

Three other nearby inscriptions read: ‘Здесь работал Костя Беляков 1944 вpt' (translation: Kostia (Konstantin) Beliakov worked here 1944) (Figure 4b), ‘Haase’ accompanied by the date ‘1944’ (Figure 4c), and ‘1944 [?] Щербаков Сергей' (1944 Shcherbakov Sergei). Although no further information could be found regarding Sergei Shcherbakov, it can be assumed that he was in the same working party as Nikolai Michailenko, given that these inscriptions were both written into the same concrete.

ITS and HSVRCD searches revealed a Konstantin Bjelakow who was sent from Alderney to Sollstedt/Buchenwald on 12 September 1944 (List of Transfer from 1. SS Baubrigade Island Alderney to Sollstedt, 1.1.30/3411088/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM). He was then registered in Buchenwald on 22 September 1944 as a political prisoner with the number 88069 (Personal File of Konstantin Bjelakow, 1.1.5.3/5549032/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM).

Hans Haase also appears on this transport list from Alderney to Sollstedt/Buchenwald. Although it cannot be definitively proven that this individual made the inscription ‘Haase 1944’, he was on Alderney at the time it was made and no other inmates with the surname Haase appear on any known records. All other ‘Haase’ registered in Neuengamme died in 1943 and could thus not have been on Alderney in 1944.

Records regarding Hans Haase are plentiful. He was born in Dresden on 3 March 1919. His father was a cereal-handler, and, after the war, a request was submitted to the ITS for information about his whereabouts by a childhood friend (Personal File of Hans Haase, 6.3.3.2/112706273, /ITS Digital Archive, USHMM). Having been arrested in 1938, Hans survived incarceration as a political prisoner throughout the war but died in Sachsenhausen concentration camp less than a month before it was liberated (USHMM HSVRCD, Sachsenhausen Deaths). He spent time in Sachsenhausen (prisoner number 42038), Buchenwald (prisoner number 88469), Flossenberg (prisoner number 2419), Sollstedt, and Mittelbau camps. In Sachsenhausen, where he had three separate periods of incarceration, he was registered as a protective custody prisoner (Schutzhäftling). It was from here that he was transported to Alderney with SS Baubrigade I.

One of the names discovered during the survey evidently belonged to a German soldier, a Gefreiter (Lance Corporal) E. Mitzscherling stationed on Alderney, as shown by his military title (Figure 4e). This engraving was found in concrete near the entrance to a bunker at Frying Pan Battery (Figure 2). Unfortunately, in the absence of a first name or any further details, the Deutsche Dienststelle (formerly the Wehrmachtsauskunftsstelle or WASt, the agency that holds the records for former Wehrmacht members) was unable to provide further information about the soldier's background.

A number of other partial names were located during the survey. No further information could be gleaned about whether these individuals were labourers, guards, or post-war visitors to the island. These include ‘Hans Reissig’, whose name was found in a bombed coastal command post bunker at West Battery and an inscription ‘Harry was here 1945’ found at Frying Pan Battery (Figure 4f).

Footwear impressions and handprints

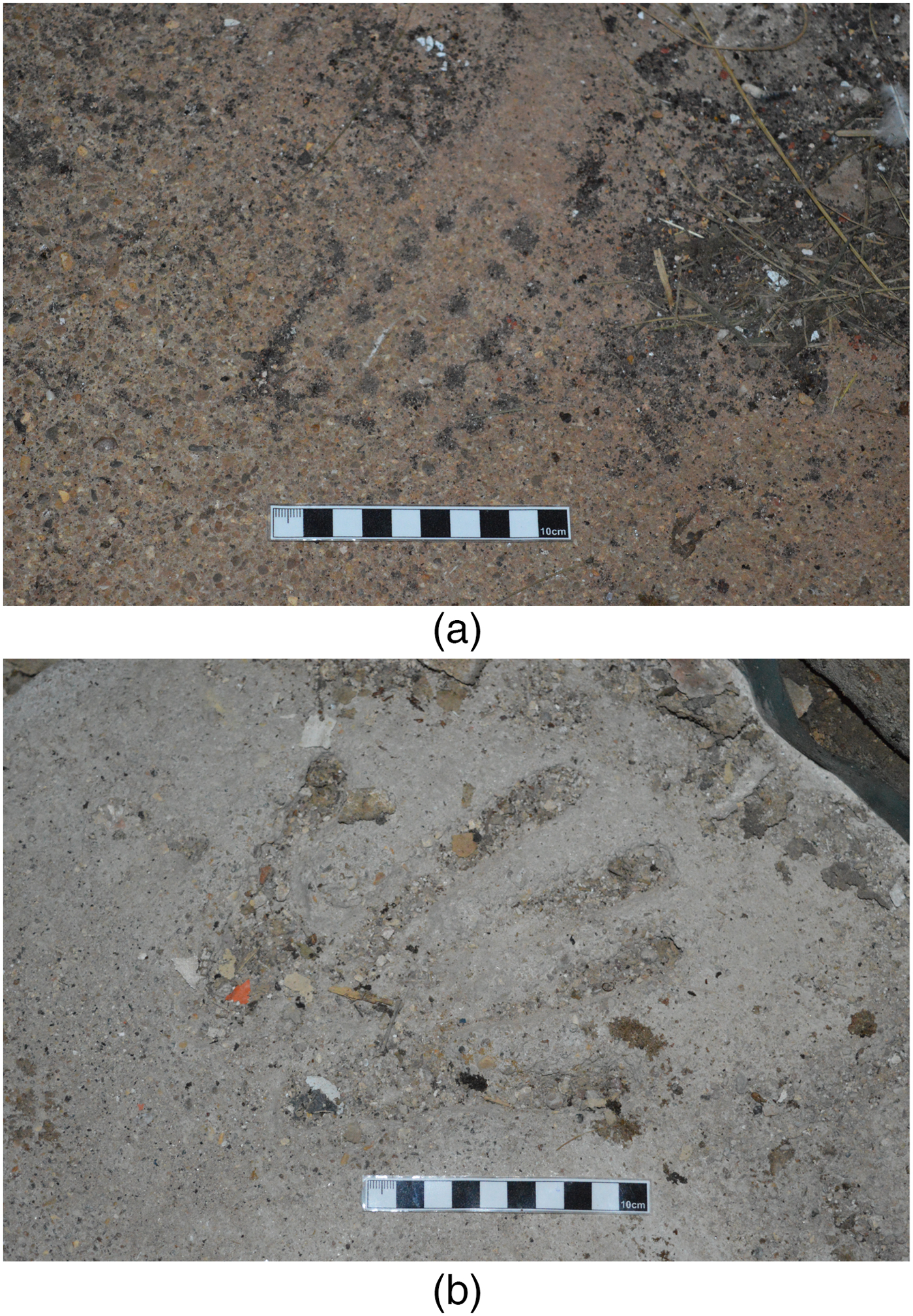

Aside from names, footwear impressions and handprints were discovered and represent traces of human presence on Alderney during the occupation. Footwear impressions were recorded in the floors of a WWII-era bunker in Fort Tourgis and in a bunker at Longis Bay (Figure 5a). A handprint was observed in WWII-era concrete at Fort Albert (adjacent to the engraving ‘Lee’) (Figure 5b) and a partial handprint was found in a chute under the camp laundry at the SS concentration camp of Sylt.

Figure 5. Examples of footwear (a) and handprint (b) impressions created in wet concrete, indicating the presence of human life at the time of concrete deposition.

Time-keeping

Fifty-three examples of time-keeping marks were encountered during the survey (Table 1), the majority within the prison cells at Fort Tourgis. Several tallies were recorded, providing evidence of how inmates held in the cells kept track of time. The presence of engravings which list the first letters of the German days of the week (MDMDFSS: Montag, Dienstag, Mittwoch, Donnerstag, Freitag, Samstag, Sonntag), along with an apparent date system, suggests that at least some German prisoners were housed here (Figure 6a). As the fort was used as a jail in Victorian times, during the German occupation, and in 1945 by the British liberating forces (to house German soldiers arrested after liberation of the island in May 1945; Davenport, Reference Davenport2009), it is difficult to determine what era most of the other marks date to.

Figure 6. Tallies and dating mechanisms created by German prisoners in the cells inside the walls of Fort Tourgis (a) and artworks found within the same building (b–c).

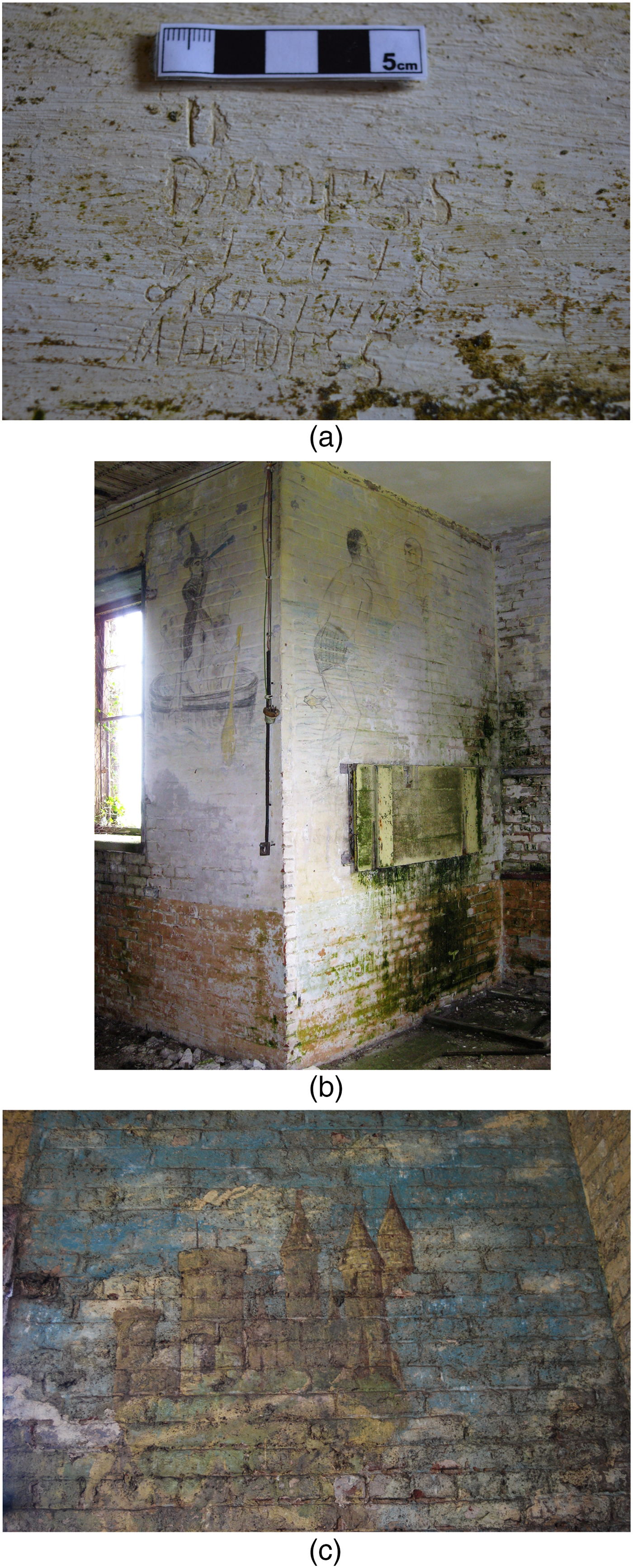

Artworks

Seventy-six instances of art-based graffiti were noted on Alderney, but these were predominantly made post-occupation. Most of these marks were documented in Fort Tourgis and within bunkers elsewhere on the island. A set of paintings located within the garrison living areas at Fort Tourgis demonstrate humour: one painting shows a man with his hands below the water being blamed by his female companion for the actions of an overzealous crab (Figure 6b). A romantic painting of a castle features on another wall (Figure 6c), while dancing couples and a person in a boat (Figure 6b) are themes of the other two works. Local historians have suggested that these were created during the occupation—and perhaps the Bavarian style of the castle might be an indicator—but, in the absence of other evidence, this cannot be confirmed. Other examples can be attributed to German soldiers from their content and the fact that they were observed immediately after the islanders returned to Alderney after the war: for example, a painting of a sailor playing the accordion survives in Strongpoint Südhafen, accompanied by slogans written by the German marine corps (illustrated in Davenport, Reference Davenport2003: 144).

Instructions and military motifs

The easiest marks that date conclusively to the occupation of Alderney are the examples of permitted marks made by German soldiers. Most commonly, these took the form of German operational instructions and slogans within fortifications. Some of the surviving statements documented were functional (operational instructions, warning signs, labels, and other signage) and illustrate the purpose and operational practicalities of the structures they appear in. Lamp recesses, shell loading points, and room designations were observed alongside hazard indicators and warnings within forts, a naval battery, casemates gun positions, and bunkers (Figure 7a).

Figure 7. Examples of operational instructions (a), military slogans and quotes (b), original German military motifs (c–d), and symbols created post-war (e).

Other graffiti expressed military sentiments. For example, a quote by Prussian army Field Marshall August Graf (Count) Neidhardt von Gneisenau (1760–1831) was located at the entranceway to the major strongpoint of Fort Grosnez (Figure 7b). It reads:

‘Laßt den Schwächling angstvoll zagen! Wer um Hohes kämpft muß wagen; Leben gilt es oder Tod! (Let the weakling say fearfully! Who fights for God must dare. It is life or death!) Gneisenau.’

This quote would have been widely known by soldiers in the German army. Another exhortation, in Strongpoint Südhafen expresses a similar sentiment:

‘He knows no honours outwardly shown, only his hard duty. With earnest eye and pale cheek he goes quietly to his death… Late or early, he is simple and brave, undaunted in storm. Unpretentious infantry! May God protect you!’

Nazi party motifs were found within the bunkers and at the forts where the German garrison were stationed. Examples are highlighted in the form of a Third Reich Eagle (Figure 7c)—whose paint has been refreshed to restore and preserve it by the current owner of the bunker—and a swastika above the entrance to Fort Albert, one of the main living quarters and military strongholds of the German garrison. Swastikas, names, and dates were also observed at Fort Albert, most prominently around gun positions (Figure 7d). These could be distinguished from several post-war swastikas observed during the survey which were most commonly created with spray paint (Figure 7e).

Construction dates

The systematic mapping of graffiti also allowed us to examine the construction dates of some of the fortifications. An examination of the large anti-tank wall that runs along the south coast of the island revealed dates inscribed into the top of each section (Figure 8). The first complete and visible date is 16 April 1942 (Figure 8a) and the last 26 October 1943 (Figure 8b). Initially it was assumed that they were construction dates. However, an examination of Royal Air Force aerial photographs demonstrated that most of the wall had been erected by 30 September 1942 (National Collection of Aerial Photography, NCAP, ACIU 05118). Hence, perhaps these dates represent the dates that the final construction works on each section were completed or another milestone deemed worthy of permanent marking. Due to the varied information contained in the inscriptions and the fact that the labourers working on construction projects changed frequently, it is likely that different sets of engravings were created by different individuals, potentially from different countries according to their choice of date separators (IBM, n.d.; Figure 8c). Other fortification construction and repair dates were also noted across the island, many, as mentioned above, in conjunction with the names of their creators.

Figure 8. The first (a) and last (b) clearly visible dates inscribed into the concrete of the anti-tank wall on Longis Common. Another example (c) shows the use of alternative date separators.

Proof of Life

The wide range of marks recorded during the archaeological survey on Alderney individually and collectively offers the opportunity to identify new and corroborative information regarding the occupation of the island in WWII. These marks provide proof of life of the forced and slave labourers imprisoned there as well as of the German military personnel responsible for the island's defence.

As Casella (Reference Casella, Beisaw and Gibb2009) has argued, the creation of marks during periods of confinement provides a form of testimony to the existence of individuals in a given space and time. This evidence may be general—in terms of confirming the presence of anonymous individuals or groups in a given space—or it may be precise, making the identification of specific people possible. On Alderney, both types of evidence were provided by marks that could be attributed to the occupation period. Probable and speculative identities have been suggested for three slave labourers, while several other names have been highlighted for future research and ongoing comparison with any new documentary evidence that may emerge. In missing persons cases and conflict scenarios alike, the value for family members and society as a whole of identifying what victims experienced and where this occurred has been widely acknowledged (Holmes, Reference Holmes, Morewitz and Sturdy Colls2016; Sturdy Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls, Morewitz and Colls2016). This is particularly true in long-term missing persons cases, where individuals are thought or known to be deceased, and where finding a grave may not always be possible (Sturdy Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls2015). After the fall of Hitler's Third Reich, large-scale concerted efforts were made to trace living and deceased individuals who had been the subject of Nazi persecution and displacement. Most commonly, this occurred through agencies such as the ITS, national, government-led initiatives and other survivor and community organisations. These searches relied on witness testimonies and documents as well as, to a lesser extent, the identification of human remains. Many searches continue to the present day, others have stagnated due to a lack of information or the passing of survivors. While detailed records have been compiled about the victims who spent time in the larger, better-known internment camps, information about individuals sent to the tens of thousands of smaller camps remains limited. Likewise, the role that landscape studies and material culture can play in searches for missing persons and in enhancing historical narratives regarding Nazi persecution has only recently been acknowledged (Sturdy Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls2015). Therefore, marks made by individuals during periods of confinement and persecution may offer new ways of tracing individuals and provide a form of what Bashford et al. (Reference Bashford, Hobbins, Clarke and Frederick2016: 52) have termed ‘anti-authoritarian’ memorialization. For the events on Alderney, since only a small number of transport lists and other records exist about exactly who was sent there to undertake forced and slave labour, these marks have provided the only confirmation of several individuals' existence on the island, their mark-making offering proof of life not available by other means. Thus far, the individuals identified are SS concentration camp prisoners, as opposed to OT workers. This reflects the availability of records concerning these two groups of labourers. Researchers attempting to undertake similar studies at other sites should be aware of how the availability of ante-mortem and other documentary records will affect their ability to create biographies for persons named within markings.

Aside from individual identities, the marks observed provide evidence about unnamed individuals and groups. The ethnic diversity of the forced and slave labourers housed on Alderney was presented: in some examples, this was evident in the names and the script in which they were written, in others the clues were subtler, as indicated, for example, by the use of date separators. Handprints and footprints made hastily or accidently into the wet concrete leave anonymous traces of those involved in the construction of fortifications, but they could yield further biological information about individuals if methods used in rock art studies (Mackie, Reference Mackie2015; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Hall, Randolph-Quinney and Sinclair2017) were to be applied. In general, traces of the forced and slave labourers who were sent to Alderney are, perhaps unsurprisingly, discrete and few. As they were living and working under permanent scrutiny of OT, the Wehrmacht or SS guards, the workers had little opportunity to leave behind evidence of their existence. Additionally, the creation of these marks would have carried a substantial risk. Punishments were levied against both SS prisoners and OT workers for any perceived misdemeanour; leaving evidence of one's presence on the island and defacing military installations would have generally carried harsh penalties given the occupiers’ desire for order and secrecy. Therefore, the mental and physiological demands of creating marks should not be underestimated (Casella, Reference Casella2014: 111).

The motivation behind the creation of marks is often ‘a need to materially acknowledge one's presence’ in a location (Casella, Reference Casella2014: 109), hence the prevalence of names and other personal information at sites of confinement. These marks are almost always made illicitly. Mark-making can be a deeply personal and performative act, the intention being to rehumanize oneself and/or to provide a coping mechanism following or during a period of oppression (Casella, Reference Casella, Beisaw and Gibb2009; Frederick, Reference Frederick2009). Certainly, the labourers on Alderney were subject to harsh living and working conditions which served to dehumanize and oppress them. Placed into usually overcrowded camps, starved and forced to undertake harsh labour, they were further dehumanized by being allocated a prisoner number (in both the SS and OT camps), being obliged to wear a striped uniform (in the case of the SS prisoners) and, in the case of the prisoners from Eastern Europe, being referred to as ‘Russian’ regardless of their nationality. The prevalence of names, often accompanied by dates, indicates a desire by the prisoners to leave their mark. The use of Cyrillic script in many cases is interesting to note, given that only those familiar with Cyrillic would be able to read them. The anonymity of these marks—and others where only partial names or initials were present—perhaps suggests that their creation was intended as a personal act and/or as a communication to other labourers rather than as a message to the outside world. The creation of tallies and calendars to monitor the passage of time is also likely to have been a coping mechanism designed to provide order to a prisoner's day. These tallies made up most of the marks within the prison cells at Fort Tourgis, while names were totally absent. This suggests that the labourers were more concerned with highlighting their presence on the island than those confined to the prison cells (who were most likely military personnel).

The making of marks can also provide evidence of an individual or group's existence to the outside world (Frederick & Clarke, Reference Frederick and Clarke2014). In the context of graffiti found within prisons, Palmer (Reference Palmer1997) and Casella (Reference Casella, Beisaw and Gibb2009) have argued that graffiti sometimes creates a dialogue, ‘powerfully forging links between the inmate authors and their (un)intended audience’ (Casella, Reference Casella, Beisaw and Gibb2009: 174), and this can be extended to include other sites of confinement. In relation to the labourer experiences on Alderney, the provision of full names and an indication of why marks were being made (e.g. ‘Kostia [Konstantin] Beliakov worked here 1944’) suggests that at least some of the labourers wanted their existence on the island to be documented. The exact motivation behind leaving their name or other marks cannot of course be fully known in the absence of other sources. However, some possibilities include a desire by individuals to be remembered, a belief that they would not survive, a form of proof to the outside world (including their family) of their presence, and a means of providing evidence of the incarceration and ill-treatment of individuals during the occupation more broadly. Similar acts reifying these motivations have been observed at Holocaust sites and other sites of violence and incarceration around the world (Huiskes, Reference Huiskes1983; Jung, Reference Jung2013; Sturdy Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls2015: 265–286).

Whether motivated by a desire to rebel or a desire to send a message to the outside world, the majority of the marks that did exist were not seemingly hidden from view. Some individuals on Alderney even wrote their full names—something which scholars examining other sites of confinement have noted as being relatively rare (Agutter, Reference Agutter2014)—and they did so in prominent locations which were easily visible. They could, therefore, have potentially been identified by their overseers; hence they must have thought that it was worth the risk. For the labourers who spoke Ukrainian or Russian, the use of the Cyrillic alphabet would have afforded them some protection, but they still risked being caught in the act of mark-making. Interestingly, the marks observed during the survey were not destroyed by the Germans, even though they would have been visible. It is impossible to know why this was the case; but, regarding the names etched into brick at Fort Albert, perhaps the occupiers did not notice them. For the more visible names at Fort Grosnez, the Germans might have been unconcerned with the fact that the outside world could eventually read the names of ‘Russian’ workers, given that they were generally open about workers being sent to Alderney to build fortifications.

The choice of material onto which graffiti is placed can also reveal information about its creators and their motivations. It will, of course, also influence its potential to survive (McAtackney, Reference McAtackney2011); the medium used for the graffiti can therefore also be indicative of whether an individual aspired to create a permanent or temporary record of their existence. In Alderney, the placement of all the documented marks created by the labourers on or within fortifications could suggest a desire for permanence since all these structures were built to last and were made of either concrete or brick; they provided a ‘durable statement of “I was here”’ and a more reliable means of providing proof of life (Casella, Reference Casella2014: 112). However, the placement of marks on or within the fortifications (usually engraved into wet concrete) may have also been opportunistic. The rapid creation of a handprint versus some of the more detailed inscriptions in concrete or brick illustrates that some labourers had more time or freedom to create marks compared to others. Of course, it should be remembered that further graffiti may have existed within the camps in which the labourers were housed, but such marks were destroyed before Alderney was liberated by the British forces.

The symbolic value of marking the fortifications that the labourers were forced to build was likely not lost on their comrades. As Frederick (Reference Frederick2009: 212) recalls, ‘graffiti is regularly interpreted not only as a record of human presence and the social construction of space but as a function of efforts to make claims over space’; hence, this act of rebellion allowed the labourers to perform an act of resistance and lay claim to one of the structures through which their overseers tried to oppress them. Compared to other sites of confinement that have been studied in a similar way to Alderney, acts of resistance combined with expressions of religious and political identity were rarely encountered on Alderney. In fact, the only recorded instance of religious expression was in the form of a Star of David engraved into a bunker at the Norderney camp.

Marks that could be definitively and speculatively attributed to military personnel stationed on Alderney suggested, perhaps unsurprisingly, different motivations for their creation when compared to those made by forced and slave labourers. Expressions of allegiance to the Nazi party were most common, and military slogans highlighted the military's apparent commitment to the Third Reich. However, these sentiments stood in contrast to the reality of combat and life for most soldiers on the island. Despite building hundreds of military installations on Alderney, the Germans only engaged in one military skirmish. Therefore, the sentiment ‘it is life or death’ expressed in many of the military slogans recorded was simply a rhetorical device. As well as the permitted marks made by soldiers, a number of illicit marks created by individual or specific groups of soldiers were also observed. Swastikas, names, and dates identified around gun positions at Fort Albert may represent motifs made during periods of boredom, a state many soldiers reported experiencing in post-war testimonies (Figure 7d).

Finally, the recorded marks have also provided valuable information about the wider events of the occupation of Alderney, thus confirming and supplementing existing historical narratives. When coupled with historical sources and other archaeological evidence, marks dating to the occupation period give an insight into the distribution of prisoners across the island, the work they were allocated, and the periods in which certain prisoner groups were in different locations. This is particularly important given that the Nazis destroyed much of the documentation relating to the construction programme. Such insights would prove useful in other mass violence and conflict scenarios to understand patterns of movement and population density. Although not the subject of this article, the post-liberation markings recorded also offer the opportunity to evaluate the re-appropriation of the island by the British, and comparative studies with mark-making practices in the other Channel Islands may reveal further information about forced and slave labour in the region.

Conclusion

The history of the occupation of Alderney remains contested and incomplete. Even after seventy years of investigations, many questions remain. The examination of mark-making practices carried out by individuals who were incarcerated has provided important complementary information which, as Agutter (Reference Agutter2014: 106) has argued, moves us ‘away from dry historical facts and sensationalism to the stories of individuals, their personalities and their experiences of being incarcerated’. Although there were challenges and limitations to our study, the identification of individual names, dates, artworks, engravings, and other markings made during periods of internment has provided new details about individuals and their personal and collective experiences. Some of this information, including evidence confirming the presence of some people on the island, was not available through other means, while other findings complemented existing sources. As our research within a project dedicated to understanding the history and archaeology of the occupation of Alderney progresses, we hope that further results will come to light. The study presented here adds to a growing body of literature concerning the value of examining mark-making practices, particularly in conflict scenarios and instances of confinement. By examining the contents and purpose of a wide range of marks, it is possible to realize the potential of these traces as indicators of a wide spectrum of details, human actions, and emotions that in turn can provide a diverse range of proof of life.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was received from Staffordshire University. The authors would like to thank the States of Alderney for granting access to some of the restricted fortifications on Alderney and their support of the university's educational research programme during these surveys. Our thanks go to numerous Alderney residents for allowing us access to their property and personal archives to support the wider research initiative. Thanks are also due to Daria Cherkaska for the transcriptions and translations of the Cyrillic text, numerous staff members and students from Staffordshire University who took part in the survey work, and to Will Mitchell for his assistance with the figures. Special thanks are owed to Steven Vitto and William Connelly at the United States Holocaust Museum's Holocaust Survivor and Victims Resource Center for their assistance in researching individual names discovered during the archaeological fieldwork, which led to the identification of the individuals named in this article.

Abbreviations for archival sources

- HSVRCD

Holocaust Survivors and Victims Resource Center Database, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington DC, USA

- ITS

International Tracing Service, Bad Arolsen, Germany

- NCAP

National Collection of Aerial Photography, Edinburgh, UK

- TNA

The National Archives, Kew, UK

- USHMM

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington DC, USA