This section is intended for occasional contributions from on-the-ground practitioners in Geneva and national capitals. Our hope is that this category will inspire other practitioners to submit notes and articles – typically in the range of 2,000 to 10,000 words – to the World Trade Review. As with all notes and articles submitted to the World Trade Review, manuscripts in this category will be reviewed by independent referees. However, the focus is intended to be practice oriented and at least one of the two referees will be a fellow practitioner.

1. Introduction

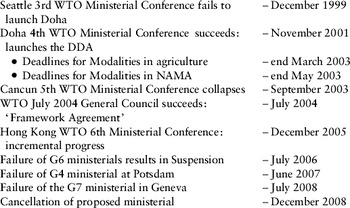

The WTO Doha Round negotiations were launched in November 2001, in Doha, Qatar in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attack on the US. The event was a significant success for the newly formed WTO after the dramatic failure of the Seattle Ministerial Conference held in December 1999 to launch the new round. However, this initial success was to be marred by several subsequent failed ministerialFootnote 1 meetings and missed deadlines. The Doha mandate called for modalitiesFootnote 2 in agriculture to be agreed by March 2002, and in NAMA (non-agricultural market access or industrial tariffs) by the end of May 2002. By December 2008, the establishment of full modalities, in the agriculture and the NAMA negotiations, was still to be achieved by the WTO.

The attempt by WTO members to secure a ‘framework agreement’ by the time of the Cancun Ministerial Conference, in September 2003, was frustrated by the collapse of the Cancun meeting. The limited objective of WTO members to at least agree on a ‘framework’ for modalities was finally achieved in the July 2004 Framework Agreement. Building on this success and learning from the Cancun collapse, the WTO reduced its expectation to achieve full modalities at the next WTO Ministerial Conference held in Hong Kong, China, and merely made some incremental advances on the July 2004 Framework Agreement. However, since then the various attempts to achieve full modalities in agriculture and NAMA have been unsuccessful. A group of six (G6) WTO members (US, EU, Japan, Australia, Brazil, and India) attempted to advance the modalities negotiations among themselves in early 2006, only to result in another failure for the WTO by July 2006. Pascal Lamy, the Director-General of the WTO, who hosted and chaired the G6 ministerial meetings in July 2006, in Geneva, decided to suspend the Doha negotiations.

A smaller group of four members (EU, US, India, and Brazil – G4) then began a process of negotiation amongst themselves in an attempt to make a breakthrough on the vexed issues of agriculture and NAMA modalities during the first half of 2007. The G4 Ministerial meeting held in Potsdam, Germany, from the 19–23 June 2007 collapsed on the third day of the scheduled four to five day meeting. After the collapse of the Potsdam G4 Ministerial meeting, the WTO Director-General, Pascal Lamy, called on the chairs of the WTO negotiating groups to resume the multilateral negotiating process of the Doha Round.Footnote 3

The chairs of agriculture and NAMA had produced several draft texts since June 2007, leading to their third draft texts produced on the 10 July 2008. These texts were to become the basis for the finalization of the negotiations on agriculture and NAMA modalities at the end of July 2008. After several missed informal deadlines, the chair of the WTO Trade Negotiating Council (TNC), Pascal Lamy, called for a final negotiating process, based on the chairs texts, to be held from the 21 July, with about 30–40 Ministers invited to participate in the process. However, this attempt to conclude the negotiations on agriculture and NAMA was to fail again with the collapse of the G7 (EU, US, Japan, Australia, China, India, and Brazil) ministerial, and the consequent failure of the WTO to conclude the negotiations on the modalities of agriculture and NAMA at the end of July 2008. The G7 ministers and several other small groups that met in July produced some incremental, but very controversial advances, on the agriculture and NAMA modalities negotiations.

Section 2 of the paper will briefly discuss the ‘Lamy Package’ that emerged out of the G7 ministerial meetings and the subsequent reports of the chairs of agriculture and NAMA on the July 2008 modalities negotiations. The paper will then update the reader on the developments in the WTO negotiations post-July 2008 up to the end of December 2008. Attempts by Pascal Lamy to invite ministers to Geneva to continue the negotiations that collapsed in July were to fail. There were intense bilalteral and trilateral negotiations between the US, India, and China that were facilitated by Pascal Lamy in several teleconferences. However, as Pascal Lamy intensified his efforts, US Congressional Leaders sent letters to President Bush urging him not to support a ministerial negotiation in Geneva at the end of December. The USTR (United States Trade Representative), Susan Schwab, was to increase the pressure on China, India, and Brazil to participate in sectoral negotiations (i.e., on specific sectors such as chemicals, industrial machinery, health care products, etc.) in the industrial sector and negotiate further market opening for US exporters. At the same time, several developed countries, including Japan and Canada, were seeking greater exemptions from the July agriculture texts for their sensitive agricultural sectors.

These events illustrate the way in which imbalanced texts can persist in WTO negotiations and the pressures exerted by the US (and other advanced countries) to maintain a high level of ambition in areas of interest to the developed countries, whilst reducing the ambition in areas of interest to developing countries. Pascal Lamy had no option but to cancel his proposed ministerial meetings scheduled for the end of December 2008, thus creating another failure for the WTO.

Section 3 of this paper will discuss the reasons for the failure of the July 2008 ministerial meetings. It suggests three reasons for the failure of the ministerial meetings at the end of July. The first reason offered for the failure is the persistence of protectionism within the EU and the US, and their attempts to raise the bar of the level of ambition for developing countries, particularly the major emerging markets that have been perceived as significant competitors with the EU and US. Several writers have argued that the history of the GATT reflects: the marginalization of developing country interests, the assertion of the major economic powers of their own market access interests in foreign markets, and the persistence of protectionism in the major developed country markets.Footnote 4 This has resulted in an ‘asymmetry of economic opportunity’ against developing countries and the persistence of unbalanced texts in favour of developed countries in the GATT up to the Uruguay Round.Footnote 5 This paper evaluates the validity of this view during the Doha Round and during the period leading up to and including the July 2008 ministerial meetings. It argues that there has been a continuity in the tendency toward protectionism in the EU and the US since the onset of the Doha Round. In addition, the EU and US have increased the collaboration between them, accommodating each others interests and pursuing an aggressive market opening agenda vis-à-vis the major emerging markets that have been perceived to be their competitors in global markets. This paper thus contributes to the thesis advanced by several writers of the persistence of ‘asymmetry of economic opportunity’ in favour of developed countries in the WTO.

The second reason that is offered for the failure is the resurrection of the ‘principal supplier’ approach and power politics of the earlier GATT period (in the form of the G7), that resulted in the collapse of each phase of the process in the past, when it was employed at Potsdam in June 2007 (G4), in July 2006 when the failure of the G6 ministers led to the suspension of the round by the DG, and at the collapse of the Cancun ministerial meeting where the majority of members were not represented in the Green Room.Footnote 6 The moving deadlines for the date of the ministerial meetings from before Easter to after Easter, to the third week of May, to mid-June, and then end July 2008 created a great deal of uncertainty. In contrast, the July 2004 Framework Agreement was negotiated in a more inclusive multilateral process, resulting in a successful outcome. Similarly, the Green Rooms, chaired by Pascal Lamy, at the Hong Kong ministerial meeting at the end of 2005, were able to make some incremental advances on the July 2004 Framework Agreement, due to the inclusiveness of the meetings.

This paper will relate the current debate in the WTO on the inclusiveness of the decision-making process during the July 2008 ministerial meetings to the earliest debates in the International Trade Organization (ITO) and GATT. During the latter debate on decision making in the ITO, developing countries had voiced strong opposition to weighted voting that was favoured by the US and came out in favour of the more inclusive consensus method of decision making. However, the principal supplier method of tariff negotiations by which a country could only be requested to make tariff cuts on a particular product by the principal supplier of that product to that country, which the US insisted upon, locked out developing countries from most of the GATT negotiations.Footnote 7 This paper will thus review the debate in the recent Warwick Commission and the earlier Sutherland Report on the decision-making procedures and the inclusiveness of WTO negotiations. It will be argued that the formation of the G7 group of members by the Chairman of the WTO Trade Negotiating Committee (TNC) during the July 2008 ministerial meetings was a return to the principal supplier principle favoured by the US in the earliest days of the GATT.

The paper will argue that the principal supplier method is an obsolete (or ‘medieval’) method of decision making, and was a contributory factor to the failure of the WTO ministerial meetings in July 2008. The G7 ministerial meetings called by the Chairman of the TNC, Pascal Lamy, during the July 2008 ministerial meetings failed to achieve the objective of negotiating the breakthrough in the agriculture and NAMA modalities negotiations that WTO members had hoped for. Some agreements reached in the G7 on elements of the modalities – the so-called ‘Lamy Package’ – did not have the support of all the members of the G7,Footnote 8 and the G7 did not enjoy the support of the majority of WTO members that felt that their issues were marginalized in the negotiations (discussed below). The paper thus calls for a more inclusive method of decision making that recognizes the role of the many developing country coalitions that have been created during the Doha Round.

The third reason ascribes the failure to the imbalanced nature of the texts, both within NAMA and between NAMA and agriculture. The promise of the Doha Round was that the trade distorting subsidies and prohibitive tariff barriers in developed countries, that undermined developing country agriculture, would be substantially reduced. In NAMA, the industrial tariffs of developed countries still retained high peaks and tariff escalation but were relatively low, whilst developing countries had relatively high bound tariffs. Developed countries were thus expected to make a major contribution by reducing their agriculture subsidies and opening their agriculture markets and developing countries were expected to reciprocate in a proportionate manner by reducing their relatively higher bound tariffs in NAMA. However, with each revised set of texts produced by the chairs, the agriculture text was perceived to contain only insignificant commitments by the developed countries in agriculture, whilst the NAMA text provided for relatively onerous market opening into developing countries, particularly the larger emerging economies.

This was partly ascribed to the role of the chair of the NAMA negotiating group, who, by his own admission, attempted at the very outset, in his first draft text, to determine the level of ambition himself.Footnote 9 The criticism made by the NAMA 11 group of developing countriesFootnote 10 was that these views, reflected in the first draft NAMA text, coincided rather closely with those of the major developed countries, and failed to represent their views. In sharp contrast, the agriculture chair consistently maintained a bottom-up process that included the views of all the different groups in his different draft texts. Two recent academic papers attempt to theorize the role of the chair in WTO negotiations. Jonas TallbergFootnote 11 provides a ‘rational institutionalist theory’ of the role of the chair in international negotiations. He argues that the chairs that play these roles are vested with ‘asymmetric’ power to influence the negotiations. After applying this theory to the role of the chairs in the WTO, he argues that there was ‘no evidence of the chairs having systematically biased outcomes’. However, this thesis is contradicted by the work of John Odell,Footnote 12 who has undertaken an extensive study of the role of the chairs in WTO negotiations and provides several examples of sub-optimal or inefficient outcomes as a result of injudicious use of the brokerage methods or the bias of the chair. This paper will argue that, whilst the basic theory advanced by Tallberg is a useful framework for our analysis, his finding that there was ‘no evidence of the chairs having systematically biased outcomes’ is incorrect. In addition to the evidence provided by Odell, the analysis belowFootnote 13 of the role of the chairs in the July 2008 ministerial meetings provides further evidence of sub-optimal or inefficient outcomes as a result of injudicious use of the brokerage methods or the bias of the chair. This paper will argue that this inefficient role of the chairs in the July 2008 ministerial meetings was to become a significant contributory factor for the collapse of the July 2008 ministerial meetings.

Section 3 will thus undertake an assessment of the collapse of the end July ministerial meetings and advance three main reasons for the collapse (discussed above) with reference to the theoretical and conceptual debates in the academic literature.

Section 4 concludes the discussion on the analysis of the collapse of the July ministerial meetings and makes some recommendations for WTO members to address the underlying causes of the collapse. The paper concludes by calling on developing countries to continue to work, in 2009, for a successful conclusion of the Doha Round based on its development mandate.

2. The WTO July Ministerial Meetings and the ‘Lamy Package’

This section will begin by describing the events that led to the collapse of the G7 Ministerial Meetings at the end of July 2008. It will then set out the main elements of the ‘Lamy Package’. The subsequent reports of the chairs of agriculture and NAMA are then briefly summarized.

What happened during the 11 days of the July 2008 (19–29) modalities negotiations?

After two days of opening statements, in the WTO TNC and Green Room, Pascal Lamy constituted the G7 Ministerial (USA, EU, Japan, Australia, China, India, and Brazil), which was to dominate the negotiations until their collapse on 29 July. The negotiations were held in different formats. They began with the TNC, then Green Rooms (about 31 members), and then the creation of the G7 on Wednesday, 23 July. The TNC and the Green Rooms were held every day. However, on Monday, 28 July, members waited all day and night for a Green Room meeting which did not materialize. The G7 had been meeting throughout the night. And when the G7 convened again the next day (Tuesday, 29 July), it finally collapsed over their inability to agree on the Special Safeguard Mechanism.Footnote 14

The last TNC meeting after the collapse of the Ministerial meetings was held on Wednesday, 30 July. Pascal Lamy reported on the failure of the negotiations to reach full modalities.Footnote 15 He argued that the G7 were not able to find convergence on the Special Safeguard Mechanism (SSM) and thus were not able to get to the next set of issues which would have begun with the Cotton issue. He stated that the failure was a collective responsibility and that the progress made in all groups needed to be preserved. In this regard, he stated that the chairs of the negotiating groups would be submitting their reports.

The Lamy Package

The ‘Lamy Package’Footnote 16 that was submitted to the ‘Green Room’ on Friday night (25 July) proposed compromise in several elements of the agriculture and NAMA modalities texts.

On the overall trade distorting support (OTDS) for the US, it was proposed by Brazil, India, and China that the US should go to the bottom of the range ($13 billion dollars). The US offered $15 billion dollars and then later $14.5 billion (about the middle of the range). In exchange the US called for a ‘peace clause’ (assurances that their programmes should not be subject to legal challenges) and significant market access in agriculture, NAMA, and Services.Footnote 17 Brazil accepted the US offer on OTDS.

On NAMA, the ‘Lamy Package’ proposed coefficients in the middle of the NAMA chair ranges.Footnote 18 The package proposed a coefficient of 8 for developed countries.Footnote 19 For developing countries it proposed a coefficient of 20 for the first group of developing countries that opt for a lower coefficient and higher flexibilities;Footnote 20 22 for the second group that take the normal flexibilities; and a coefficient of 25 for the third group that opt to take no flexibilities. Brazil negotiated hard in the G7 for the flexibilitiesFootnote 21 that were provided to the first group to be extended from 14% of lines and volume to an extra 2% of trade volume. This was included in the Lamy Package.

On anti-concentration,Footnote 22 the EU and US (together with Japan and Australia) insisted on 30% of lines per chapter to be exempted from flexibilities, whilst Brazil, India, and China were only prepared to accept a 10% exclusion.Footnote 23 The Lamy text proposed that 20% of lines, or 9% of value per chapter, be excluded.

On sectorals, the Lamy Package changed the language on sectorals, from the 10 July NAMA Draft Text, that called for sectorals to help ‘balance the overall results of the negotiations on NAMA’ to providing a carrot of ‘increased coefficients for those that participate in sectorals and calls for these countries to commit to participate in at least two sectoral initiatives’. This proposal was opposed by both India and China and thus re-negotiated.Footnote 24 The new language restates the non-mandatory nature of sectorals and that participation in the negotiations of the terms of at least two sectorals of their choosing shall not prejudice the decision of the member to participate in such a sectoral. The resistance of India and China to make sectorals mandatory did succeed in preventing the attempts by the US and the EU to create a mandatory linkage between the participation of developing countries in sectorals and the core NAMA modality (formula and flexibilities).

The agriculture and NAMA chairs report on the collapse

The chairs of the agriculture and NAMA negotiations submitted their reports of the July 2008 modalities negotiations on the 12 August. The chair of agriculture in his reportFootnote 25 states that whilst there was a credible basis for conclusion of many issues, there was disagreement on other very significant issues. He goes on to state that he is not in a position to record the convergences in precise textual language as the circumstances have changed. Therefore, he states that the existing texts remain. Throughout his report he refers to the reports of the G7 and Green Room discussions and package that were reported on without attempting to convert any of this into textual language.

The Chair of NAMA in contrast states that convergence was reached on the NAMA modalities by the G7 and states that ‘the majority of members meeting in Green Room format indicated that, while they had reservations over particular issues, they could live with the proposed compromise outcomes on these elements of the NAMA modalities’.Footnote 26 He then cites three members (South Africa, Argentina, and Venezuela) that did not provide explicit support. He goes on to include the numbers in the ‘Lamy Package’ on all the issues including the coefficients, flexibilities, anti-concentration, and sectorals in textual form. On the sectorals, the new negotiated language after the first Lamy text was negotiated with India and China is included.

After the collapse of the July 2008 ministerial meetings, Pascal Lamy was to relentlessly pursue the objective of concluding the modalities negotiations. However, his efforts failed to persuade some of the major players to narrow their differences on the remaining issues and return to Geneva to conclude the negotiations on agriculture and NAMA modalities. We briefly discuss these efforts below to provide an update for the reader.

Another failure in December 2008

The G20 Leaders meeting in Washington on the 15 November 2008 instructed their Trade Ministers to conclude modalities by the end of the year.Footnote 27 Pascal Lamy sent a faxFootnote 28 to all delegations on the 1 December, urging them to keep trying to conclude the modalities negotiations by the end of the year. He called for members ‘to have ministers in town in a window of time somewhere around the 13–15 December 2008’. Later Pascal Lamy postponed the proposed Ministerial meeting to the 17–19 December.Footnote 29

The chairs of agriculture and NAMA released draft modalities texts on the 6 December 2008.Footnote 30 The chairman of the agriculture Negotiations also submitted three working documentsFootnote 31 on issues where significant differences remained between members – namely, the SSM, designation of Sensitive Products, and the Creation of new TRQs. Pascal Lamy explained that significant differences still remained on the key issues of Sectorals, the SSM, and Cotton, and including some country-specific issues in NAMA, on Argentina, South Africa, and Venezuela.

Pascal Lamy then began a series of video conferences with Ministers from the US (Susan Schwab), India (Kamal Nath), and China (Chen Deming). In a series of teleconferences held between the US and China, and US and India, on the issues of sectorals, the SSM, and cotton, the USTR, Susan Schwab, demanded that China participate in at least two sectors of interest to the US, of which at least one had to be chemicals. Susan Schwab required the participants in these sectoral negotiations not to leave the negotiations until zero for zero modalities were agreed.Footnote 32 She also demanded a safe harbour or ‘peace clause’ (a commitment not to raise subsidy disputes against the US on product specific commitments during the implementation period) for the US in agriculture. A new demand by the US for a price cross-check mechanism for the SSM was also rejected by India. The US was also reported to have had no new proposals to make on reducing its trade distorting cotton subsidies. However, by Friday, 13 December, all efforts to make movement in these bilateral and trilateral video conferences had failed to narrow the gaps that remained between the major players and the Director-General, Pascal Lamy, cancelled the proposed ministerial meeting.Footnote 33

3. Assessment of the collapse of the July 2008 Geneva Ministerial Meetings

What was the cause of the collapse?

The Lamy text (produced on Friday night, 25 July) proposed a 140% trigger on the SSM for developing countries – allowing developing countries to exceed their current bound rates only if imports on a product increased by 40% or more, in which case developing countries could exceed their bound rates by 15%.Footnote 34 India rejected this proposal and insisted on a 115% trigger instead.

Another compromise text tabled on Tuesday morning (29 July) proposed a 115–120% trigger for India with 33% increase in bound tariffs and another trigger of between 130% and 140% and a 50% increase in tariffs. India was prepared to accept the 120% trigger. China could not accept the compromise. The US refused to move from the 140% trigger. Pascal Lamy could take the process no further and the meeting collapsed. The US stated that ‘any safeguard must distinguish between the legitimate need to address exceptional situations involving sudden and extreme import surges and a mechanism that can be abused’.Footnote 35

The proximate cause of the collapse was the SSM but the negotiations could have broken on several other issues, including cotton, NAMA, new tariff quota creation, tariff simplification, bananas, geographic indicators (GIs), the relationship between the Trade Related Intellectual Rights Agreement (TRIPS) and the Conference on Bio-diversity (CBD), fishery subsidies, rules (anti-dumping), preference erosion, tropical products or duty free quota free market access (DFQFMA) for the least developed countries (LDCs)!

We offer three main reasons for the failure of the July Ministerial meeting: the increasing protectionism within the EU and the US, and their attempts to raise the bar of the level of ambition for developing countries, the resurrection of the ‘principal supplier’ approach and power politics of the earlier GATT period, and the imbalanced nature of the texts and the role of the chair. In the discussion below, we discuss the theoretical issues and concepts that have emerged in the academic literature to describe each of these concerns and then discuss them in the context of the failed July ministerial meetings.

The discussion below turns to the first reason advanced by the paper for the collapse of the July 2008 ministerial meetings: that of increasing protectionism in the US and EU and assertion of their narrow mercantilist interests. The discussion below will begin with a historical overview of this trend and proceed to evaluate the July 2008 ministerial meetings in this context.

(1) Increasing protectionism and aggressive demands of US and EU

A historical perspective of EU/US protectionism in the GATT/WTO and asymmetrical outcomes

The history of the GATT suggests that the interests of developing countries were largely ignored leading to imbalanced texts that reflected the interests of the dominant economic powers. The original GATT 1947 was based on the principle of MFN (most favoured nation treatment, i.e. that all members shall be treated equally), and thus made no special provisions for the different levels of economic development of developing countries.

Developing countries however had raised these concerns during the negotiations on the ITO Charter that was later rejected by the US Congress.Footnote 36 Developing countries continued to urge developed countries to address their particular development concerns in the GATT. This was to lead to a study of these issues that produced the Haberler Report in October 1958. The Haberler Report found that there was some substance in the feeling of disquiet among primary producing countries that the present rules and conventions about commercial policies are relatively unfavourable to them.

WilkinsonFootnote 37 observes that by the mid-1960s the evolution of the GATT led to two different experiences. For the industrialized countries, ‘liberalization under the GATT had seen the volume and value of trade in manufactured, semi-manufactured and industrial goods increase significantly’. In addition, ‘they had also managed to protect their agricultural and textile and clothing sectors through a blend of formal and informal restrictions’. To give effect to this, there were a number of GATT waivers to protect developed country agricultural markets and the exclusion of textiles and clothing from liberalization in developed countries. For developing countries this meant that the products of interest to them were excluded from liberalization.Footnote 38

US perceptions of the increasing competitiveness of the European Union, Japan, and East Asia and their economic ‘convergence’ with the US, were to lead to increasing US protectionism in the 1970s and the 1980s. Syvia OstryFootnote 39 calls the arsenal of non-tariff measures that were put in place in the 1970s mainly against Japan, but which had the effect of blocking other developing country exports into the US and the EU, the new protectionism. The 1980s saw increasing use of trade remedy laws in the US and the EU and increasing resort to unilateral trade measures by the US. By the time of the Uruguay Round, the US and the EU had begun to establish a common agenda, vis-à-vis the rest of the world. During the Uruguay Round, the US and EU were able to find accommodation of each others interests in the Blair House AccordFootnote 40 that was agreed between them on 20 November 1992. Even in the final stages of the Uruguay Round negotiations, during the first week of December 2003, the EU and the US continued to negotiate among themselves, in Brussels, prompting the then Director-General of the GATT, Peter Sutherland, to urge the EU and the US to report to the other ‘over 100 participants’ in Geneva ‘whose interests must also be assured and accommodated’.Footnote 41 As the US and the EU continued to negotiate between themselves almost until the day the Director-General called the end of the negotiations of the Uruguay Round on 15 December 1993, many other members, especially the developing countries, complained they were not in a position to assess the offers the EU and US were making against their own and that the agreements reached between the EU and the US continued to reduce the ambition on many issues of interest to developing countries, including agriculture, textiles, leather, cotton, and tropical products.Footnote 42

Another close observer of the Uruguay Round argued that the lack of real market access gains for developing countries in developed countries agriculture markets and the onerous commitments they made in the TRIPS agreement on intellectual property led to the perception that developing countries ‘had given more than they got’ and therefore the Uruguay Round Agreements were imbalanced in favour of developed countries.Footnote 43 Wilkinson has argued that this imbalance has been endemic to the GATT system, and with each Ministerial Conference of the WTO since the Doha Round was launched, this asymmetry of economic opportunity in favour of the major developed countries has been reinforced.Footnote 44 Thus failed Ministerial Conferences are perceived to be a symptom of this basic asymmetry of economic power that is embedded in the institutions of the system.Footnote 45 We now turn to an evaluation of the Doha Round negotiations up to the period December 2008 and evaluate the validity of the above trends in the GATT of US/EU protectionism and the dominance of their narrow mercantilist interests.

An evaluation: the Doha Round up to December 2008

Since the launch of the Doha Round and the lead up to the Cancun Ministerial Conference, WTO members missed the deadlines to agree on the modalities in the agriculture and NAMA negotiations. This was mainly due to their failure to meet the demands of the mandate to substantially reduce agricultural protection. As the Cancun Ministerial Conference approached, the EU and US began to negotiate a bilateral agreement to accommodate each others interests that was to result in the EU–US joint text.

The EU–US joint text tabled on 13 August 2003 galvanized developing countries into action to prevent another ‘Blair House’ type agreement that would accommodate the interests of the EU and the US and reduce the ambition of the Round once again. In addition, the joint text agreed by the EU and the US on agriculture took the negotiating process further back by agreeing to a mere ‘framework’ for the agriculture negotiations just a few weeks prior to the Cancún Ministerial. The EU–US joint text on agriculture was strongly challenged by a range of countries, including Australia, Brazil, Argentina, South Africa, and many other former US allies who had coalesced around the common objective of securing freer global agriculture markets. Developing countries, led by Brazil, China, India, South Africa, and some others, established a broad-based alliance that grew into the G20 group of developing countries coalition on agriculture.

In addition, a group of developing countriesFootnote 46 argued that the real danger of a joint push by the EU and other developed countries (notably the US)Footnote 47 to seek additional extensive concessions from developing countries in the NAMA and Services negotiations was that the development content of the Round would be turned on its head, with the developed countries making more inroads into developing country markets and with developing countries still facing high levels of protection and distortions in global markets for products of export interest to them. This united front was further consolidated in Hong Kong where Ministers of the NAMA 11 group presented joint proposals in the negotiations on NAMA.Footnote 48 This group was able to also establish a strong link between the level of ambition in NAMA with that in agriculture in the final text of the Hong Kong Declaration.Footnote 49

The closing of ranks by the EU and the US was to become more visible again in the Potsdam G4 (EU, US, Brazil, India) ministerial meeting (held on 19–21 June 2007), both to accommodate each others concerns, and to jointly apply pressure on Brazil and India. Reflecting on the collapse of the negotiations after Potsdam, the Foreign Trade Minister of Brazil, Celso Amorim, was to remark that the collaboration of EU and US during the Potsdam meeting reminded him of the EU–US Joint Text in the pre-Cancun period and he thus referred to the collaboration of the EU and US in Potsdam as Cancun II.Footnote 50

After Potsdam, the EU and US intensified the joint coordination of their positions, on agriculture, NAMA, Services,Footnote 51 and Environment.Footnote 52 On agriculture, the EU began to work more closely with the US bilaterally to build convergence in their positions on specific issues. On NAMA, the EU and US presented two new proposals on the 5 December 2007. The first proposalFootnote 53 called for a high level of ambition for developing countries. The second proposal by the EU and US called for the restriction of the existing flexibilities that were already provided for developing countries in paragraph 8 even further.Footnote 54

The first reason for the collapse of the Ministerial meetings stems from the lack of political support in the EU and the US (and other developed countries) for agricultural reform and the persistence of protectionism. To this must be added their perceptions of the increased economic power of the emerging markets, which gave rise to increased collusion between them to raise the level of ambition for developing countries in NAMA and Services. Part of this was due to an increasing clash of paradigms between the developed and developing countries, namely the increased assertion of commercial interests (the reality) or the need for ‘new trade flows’ against the livelihoods of farmers in developing countries and the industrial development prospects and jobs of workers in developing countries.

There are many factors that have contributed to this increasing protectionism within the EU and the US, including the dwindling political fortunes of the leadership in the major capitals (US, Japan, France, UK, Italy, Germany, and Canada) and their fear of increased competition from the new emerging economies. MesserlinFootnote 55 explains this phenomenon as the result of ‘increasingly thinner governing majorities, creating difficulties for governments resisting vested interests’.

In the United States the failure of the US President to veto the 2008 US Farm Bill and to re-new Trade Promotion Authority after its expiration on 1 July 2007, and the rejection of the fast track procedures by the US Congress demanded by President Bush, on the Columbia FTA, has been argued to have ‘destroyed the credibility of the United States as a negotiating partner in the eyes of the rest of the world’.Footnote 56 The strong anti-trade rhetoric of the Presidential candidates also did not help to restore confidence in the ability of the US Administration to provide leadership and deliver on its Doha obligations.Footnote 57

An additional factor for the current tension in the Doha negotiations stems from the perceived threat to the competitive positions of the traditional industrial economies from the newly emerging economies, especially the rise of the so-called BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, and China). To these economies could be added several more, including Mexico, South Africa, Argentina, and Malaysia. At the UNCTAD XII conference, held in Accra, Ghana, the Secretary General of the UN, Ban Ki Moon, stated that the developing country share of world exports have risen from 30% to almost 40%. A recent report by Goldman SachsFootnote 58 stated that, since 2001, the US share of world gross domestic product has fallen from 34% to 28%, whilst the BRICs countries share has risen from 8% to 16%. In this same period, China's reserves have rocketed from 200 billion dollars to 1,800 billion dollars, Brazils from 35 billion to 200 billion dollars, and India's from 50 billion to 300 billion dollars'.

In a rare display of public frustration with the US negotiating position, after the collapse of the July G7 ministerial meetings, Mandelson, the then EU Commissioner, stated in his weblog, ‘when the negotiations resumed during the day before the final collapse, and Pascal Lamy presented a new compromise proposal on the SSM, the Indians and Chinese express reservations and the US rejects the proposals outright, much to Lamys understandable frustration’. He went on to criticize the US approach in the negotiations as follows: ‘the dollar-for-dollar approach does not add up in any way… in a development round a dollar-for-dollar approach is never going to add up’.Footnote 59 The USTR was clearly under pressure from the US business lobbies that were to reject the compromise on sectorals that was finally agreed by the G7 ministers and recorded as such by the Chair of the NAMA negotiations in his report on the July ministerial meetings. The National Association of Manufactures of the US (NAM) criticized the report of the NAMA chair for weakening the level of ambition on sectorals and urged the USTR to refuse to accept the report as a basis for negotiations. The NAM stated that ‘given the weakness of the present across the board industrial tariff cutting proposal balance is only possible if the key countries of Brazil, China and India were to participate in negotiating sectoral agreements that would eliminate duties in major industrial sectors’.Footnote 60

Again, in the period July 2008 to December 2008, the USTR Susan Schwab did not seem to have much room to maneuver. Even as Pascal Lamy was working for a ministerial meeting to resolve the outstanding issues in the negotiations, the US Congress was working against this initiative. On 2 December, the chairs of two Congressional Committees, from both the House and the Senate wrote a letter to President Bush, which stated that: ‘In July of this year we commended your administration for walking away from a lopsided WTO package that we in Congress would not have been able to support … We strongly urge you not to allow the calendar to drive the negotiations through efforts to hastily schedule a ministerial meeting.’Footnote 61 US lawmakers from both sides of the aisle applauded the cancellation of the proposed ministerial meeting by Pascal Lamy and stated that they will work with the incoming Obama Administration in the New Year to seek solutions to the many ‘issues that have so far remained elusive’.Footnote 62

The discussion above thus points to the continuity of increased protectionism by both the US and the EU that has been re-invigorated in the current Doha Round by the perceptions of the increasing competitiveness of the newly emerging developing countries. The attempts by the US and the EU to co-ordinate their positions, accommodating their own interests and then seeking aggressive gains from other economies, especially the emerging markets, have been a strong feature of the Doha Round negotiations since Cancun and must be regarded as a major contributing factor to the collapse of the WTO July 2008 ministerial meetings and the failure of the December 2008 meetings to conclude the modalities negotiations.

It is not just the increased co-ordination of the EU and the US per se that is a cause of concern for developing countries but their considerable joint economic power and leverage, which is often used to foist their own interests and positions on the rest of the membership, especially the developing countries. Developing country alliances in the Doha Round have emerged as a counterbalance to this overwhelming negotiating leverage that the EU and US bring to bear on the system when they co-ordinate their efforts.

Thus Wilkinson's observations (discussed above) of the persistence of asymmetry of economic opportunity in the GATT/WTO since the early GATT rounds continues to retain its validity up to the end of July 2008 ministerial meetings and the failure of the WTO in December 2008. We now turn to the third reason for the collapse of the July 2008 ministerial meetings. The historical debate on the methods of decision making in the GATT will be briefly assessed and the principal supplier principle method of negotiations employed in the GATT will be evaluated. We will then evaluate the method of negotiations employed in the July 2008 ministerial meetings in this historical context.

(2) The principal supplier principle

The debate in a historical perspective

A recent evaluation of the state of the WTO undertaken by the Warwick CommissionFootnote 63 called for greater flexibility in the voting system. The Commission called for the concept of ‘variable geometry’ to replace the more rigid ‘single undertaking’ concept that was deployed in the Uruguay Round, and that has since become the conventional approach in the Doha Round. The Warwick Commission points to the earlier practices in the Tokyo Round where various agreements were reached on the codes on standards, import licensing, anti-dumping, subsidies and countervailing measures and customs valuation'. The Commission urges WTO members to seriously consider ‘critical mass as part of the decision-making procedures for delineating the WTO agenda’.

However, an earlier report,Footnote 64 established by the previous Director-General of the WTO, Dr Supachai Panitchpakdi, supports the consensus approach to decision making that is generally followed by the WTO, and suggests ways in which this could be improved. The Sutherland Report recommended that in an attempt to reduce the resort to blocking measures (such as a veto by a single country to prevent consensus) by some countries, there should be a responsibility by the country seeking to block a decision to declare in writing that the matter is one of vital national interest to it. This recommendation if implemented could help the WTO to strengthen the consensus approach to decision making and help the critics who have felt frustrated by the efforts of large members to block consensus, where the underlying reasons are extraneous to trade issues.

The Sutherland Report also addressed the call by some members to develop a differentiated (plurilateral) approach to those issues on which only a subset of members are able and willing to deepen liberalization and rule-making. The Report took a cautious approach to this possibility, suggesting further deliberation. It was judicious in taking this approach, as WTO members are currently divided on this issue and many are suspicious that this would create a two-speed and two-track system, compromising the principle of inclusiveness. The previous Director-General was concerned about the serious criticisms that the WTO faced as a result of the perception amongst civil society and developing country groups about its lack of transparency and inclusiveness in its decision making and imbalanced outcomes.Footnote 65

The issue of voting method is an old debate in the GATT and has it origins in the early negotiations on the proposed International Trade Organization (ITO) that was to be part of the Bretton Woods institutions after the War. During the negotiations on the proposed ITO after the Second World War, the issue of the voting method was one of the few issues on which the developing countries were more successful. For decision making in the ITO, the US delegation proposed the same method of weighted voting that was used in the recently created International Monetary Fund (IMF). A similar proposal was made by the UK, to take into account the economic size of the country in its share of the vote – a system of weighted voting. Developing countries voiced their opposition to such a system of voting as they feared that this would institutionalize their secondary status. A number of developing countries,Footnote 66 voiced strong opposition to weighted voting and came out in favour of consensus. As a consequence, the ITO did not adopt a system of weighted voting. This decision was to be adopted by the GATT that adopted the consensus approach to its decision making.

The principal supplier approach also had its origins in the early ITO/GATT debates. During the negotiations on the ITO, many members had preferred a system of bargaining that was formula based – across the board tariff negotiations – but the US Congress indicated that this would be unacceptable to them. The UK supported this method, as it would have led to the levelling of high US tariffs. The US delegation however argued for a system of reciprocal bargaining over specific tariff lines that required a product-by-product, principal supplier method of tariff negotiations by which a country could only be requested to make tariff cuts on a particular product by the principal supplier of that product to that country.Footnote 67 This meant that for any particular product the importing country negotiates its tariff rate with its principal supplier and not with all suppliers of the same product. Developing countries at the time were seldom principal suppliers of any product, except raw materials that entered industrialized countries duty free. Only at the 4th Geneva Round of GATT in 1956 was this rule modified to allow developing countries to negotiate collectively in requesting concessions. However, they were still effectively prevented from requesting concessions in any products that they did not produce in large quantities. Thus, the principal supplier rule had the effect of locking out developing countries from the tariff cutting negotiations.

The current debate in the WTO on the formation of small informal groups that become the main decision making forums or that shape the main content of the deals has significant resonance in the debate in the GATT since its inception. The negotiating method employed in July 2008 harked back to the principal supplier approach utilized in the old GATT. We discuss this further in the section below.

An evaluation: the G7 in the July 2008 ministerial meetings

The third reason for the collapse of the Ministerial meetings is ironically due to the ‘medieval process’Footnote 68 that saw the EU/US sticking to old habits of setting up imbalanced small groups that cut the main deals, without consideration for the smaller players, and the marginalization of their issues in the negotiations. The G7 was a surprise after the failure of the G4 (and earlier G5 and G6 informal ministerial groups) in Potsdam. The package that emerged on Friday night, 25 July 2008 (see discussion above) was not agreed and did not address the issues of interest to the majority of members. It was not supported by India and China and gained no legitimacy amongst the majority of members.

The African Ministers who were not represented in the Group of 7, also expressed their concerns in a statement made in July by stating that, ‘we are deeply concerned that in the Group of Seven (G7) not one African country was represented in a round that purports to be about development’ and that ‘most of the issues of importance to the African continent were not even discussed, especially cotton’.Footnote 69 Reflecting their dissatisfaction with the G7 process, the G33 group of developing countries, whilst they continued to support the positions that India and China expressed (India and China were represented in the G7) on the SSM, called for the issue of SSM to be returned to the WTO agriculture Negotiating Group, chaired by Crawford Falconer as soon as possible.Footnote 70

Thus, the G7 ministerial meetings called by Pascal Lamy during the July 2008 ministerial meetings failed to achieve the objective of negotiating the breakthrough in the agriculture and NAMA modalities negotiations that the Director-General, Pascal Lamy, had hoped for. Some agreements reached in the G7 on elements of the modalities – the so-called ‘Lamy Package’ – did not have the support of all the members of the G7.Footnote 71 In addition, the ‘Lamy Package’ did not enjoy the support of the majority of members that felt that their issues were marginalized in the negotiations. In addition, the Director-General, Pascal Lamy, did not succeed in resolving any of the issues of interest to the smaller developing countries in smaller side meetings that were on his so-called ‘to do’ list!Footnote 72 Cotton did not get onto the agenda at all. The banana negotiations unraveled. The issue of duty free quota free market access (DFQFMA) for LDCs was not addressed. There were several more difficult issues on NAMA that included South Africa, Argentina, and Venezuela that also remained unresolved.

We now turn to the third reason for the failure of the July and December 2008 attempts to conclude the modalities negotiations: the persistence of imbalanced texts against the interests of developing countries. The next section will begin by discussing the theory and role of the chair in WTO negotiations and proceed to consider the role of the NAMA chair in contributing to the imbalanced texts in the negotiations on modalities in July and December 2008.

(3) Imbalanced texts and the role of the chairs: theory and practice

Theory on the role of the chair

In a recent comprehensive study of the role of the chair in international negotiations, Jonas TallbergFootnote 73 attempts to develop a ‘rational institutionalist theory’ of the role of the chair in international negotiations and describes this role as ‘formal leadership’. In his consideration of these three roles of the chair in WTO negotiations he argues that the role of representation is seldom required. Thus, the role of the chair in the WTO negotiations is adequately described as that of agenda management and brokerage. He argues that the chairs that play these roles are vested with ‘asymmetric’ power to influence the negotiations. This power comes from their privileged access to information about the real preferences of members and the support of the secretariat, and their control over the negotiating process. However, this asymmetric power is conditioned by the rules governing decision making and the design of the chairmanship. He argues that the chairs' scope to influence the negotiations is much wider, if the method of decision making is that of majority voting, than the tougher methods of consensus or unanimity, where the interests of all parties have to be considered.

After applying his theory to the three different institutional settings of the EU, the WTO, and the multilateral environmental agreements, Tallberg argues that in both the latter cases, formal leaders positively enhanced the efficiency of the negotiations by transforming competing proposals into single texts and forging agreements. In addition, in these cases he argues that there was ‘no evidence of the chairs having systematically biased outcomes’.Footnote 74 However, the extensive research undertaken by OdellFootnote 75 of decision making in the GATT/WTO provides several examples of sub-optimal or inefficient outcomes as a result of injudicious use of the brokerage methods or the bias of the chair.

In a studyFootnote 76 undertaken of the role of the NAMA chair, in the NAMA negotiations, between the Potsdam G4 ministerial meeting in June 2007, and the July 2008 ministerial meeting I have argued that his role reflected all the above errors. His failure to provide efficient formal leadership was contrasted with that of the chair of agriculture, in the agriculture negotiations who displayed a capacity to listen carefully to the views of different members, to act in an objective manner, to make judicious use of the tools of brokerage (providing alternative options, single texts etc) and the appropriate timing of single texts, and a fierce independence from the influence of any of the major developed or developing country groups in the WTO.

The remainder of this paper argues that the events of July 2008 support the evidence provided by Odell that there is significant evidence of inefficient outcomes in the GATT/WTO negotiations as a result of the failure of the chairs to listen carefully to members, their inability to act in an objective manner due to their loyalty to national interests, their poor judgement of the use and timing of the tools available to them to build consensus (two or three options, single draft text), and their incorrect weighting of the views of the different groups of members (EU, US, developing country groups).

An evaluation of the role of the chairs in the July 2008 meetings

The NAMA 11 group of developing countries that represented a significant group of emerging market economies criticized the various draft texts of the NAMA chair that emerged in the period before the July 2008 ministerial meeting for ignoring their views and reflecting the preferences of the chair. This position was enunciated as follows by the South African Statement to the TNC on 22 July: ‘Our experience in the NAMA negotiations over the last two years is that the texts that have emerged at various points have consistently ignored the positions and views we have expressed as the NAMA 11.’ Furthermore, the statement notes that whilst the ‘the agricultural negotiations have been conducted through a carefully constructed “bottom-up” process through which the positions of all WTO Members are found in the agricultural modalities text, the NAMA modalities text is highly circumscribed and prescriptive. The text sets out a narrow range of coefficients, and offers flexibilities that have a double constraint in terms of the percentage of tariff lines and trade volumes that can be covered.’ The statement goes on to state that ‘we have witnessed a range of demands that would result in an outcome where many developing countries that are required to reduce their tariffs are being required to accept reduction commitments that are deep and in excess of the cuts to be borne by developed countries. These demands are inconsistent with the Doha development mandate and cannot be a basis for concluding the Round.’Footnote 77

In a statement made to the TNC on the 26 July, Argentina stated that without significant changes to the ‘Lamy Package’ it would be very difficult for Argentina to support it. Argentina argued that the package was ‘poor in agriculture and substantially unbalanced in NAMA’. Argentina argued that the implications of the proposed formula in NAMA would mean less than full reciprocity in reverse for developing countries, as the formula required developing counties to make a deeper cut in their tariffs than developed countries.Footnote 78

Minister Amorim, the Foreign Trade Minister of Brazil, also criticized the imbalanced texts, between agriculture and NAMA and within NAMA. Summing up Brazil's views on the agriculture text, he arguedFootnote 79 that the text was ‘built on a logic of accommodating exceptions rather than seeking ambition, with almost 30 paragraphs in the text establishing specific carve-outs for specific countries’. In contrast, he argued ‘the NAMA text was built on the logic of forcing countries, especially developing ones, out of comfort zones’ and he referred to the attempts to extract an ‘additional price’ in the NAMA negotiations from developing countries through the anti-concentration clause and ‘disguised mandatory sectorals which would overload the negotiations and make a conclusion impossible’.Footnote 80

Thus, the statements above point to significant dissatisfactionFootnote 81 amongst some major developing countries and developing country groups on the lack of balance between the agriculture and NAMA texts and in particular the ‘additional price’ or increased level of ambition that developing countries in NAMA were being asked to pay in the negotiations, than the relatively lower level of obligations that developed countries were willing to commit to in the agriculture negotiations. In NAMA, the chair was believed to have taken sides with the developed country demandeurs by setting the level of ambition in NAMA even before the level of ambition in agriculture had been agreed (discussed above) and by adding the anti-concentration clause and ‘disguised mandatory sectorals’, when the Doha mandate called for sectorals to be voluntary.

The ‘Lamy Package’ was seen by many developing countries to be attempting to reinforce the basic imbalances contained in the agriculture and NAMA texts as the Argentinian statement suggests. In a memorandumFootnote 82 written to Trade Ministers earlier in July, Pascal Lamy, the Director-General of the WTO and the chair of Trade Negotiating Committee (TNC), attempted to equate the contributions that were being asked of developed countries in agriculture with that of developing countries in NAMA. Referring to the commitments of developed countries to cut their farm subsidies by 70% (this is misleading as the much lower actual spending of developed countries than their bound rates will mean insignificant or no real cuts in subsidies) and farm tariff cuts of about 50% (this is also misleading as a significant part of developed country tariffs will be allowed to remain prohibitive due to the many exceptions and flexibilities that have been provided in the agriculture text), he then urges developing countries to make a contribution by opening their markets ‘in exchange for greater market opportunities’ that will be provided to them by the developed countries. This view should be contrasted with the views of a large body of developing countries that believed that the balance between the two texts was against developing countries.

The events that led to the failure of the attempt to conclude the modalities negotiations in December 2008 (described above) were to underline the persistence of the imbalanced texts and the undue pressures exerted by the US (the EU, Japan, and Canada continued to support the US demand for a high level of ambition in sectorals) to maintain a high level of ambition in areas of interest to the developed countries, whilst reducing the ambition in areas of interest to developing countries. At the TNC meeting held on the 17 December 2008, the G20 group of developing countries stated that ‘since July 2008 the gap between agriculture and NAMA has increased’.Footnote 83 The G20 statement went on to state that: ‘We observe with great concern the continuous reduction of the level of ambition in agriculture, particularly on Market Access and Domestic Support. Layers of exceptions are added for developed countries – in preserving high levels of ‘water’ in domestic support entitlements; in failing to move ahead on cotton, a central issue for a truly Development Agenda; in increasing the number of sensitive products; in avoiding tariff capping and full and fair tariff simplification; and in creating new TRQs.' The NAMA 11Footnote 84 Group of developing countries have opposed the demand by the US and other developed countries to make sectorals, especially in sectors of interest mainly to the developed countries, mandatory. The NAMA 11 argued that the demand to make sectorals mandatory is not consistent with the mandate that requires developing countries to enter into such sectoral negotiations on a voluntary basis. Conceding to the demands of the US/EU would have deepened the ‘asymmetry of economic opportunity’ that has characterized GATT/WTO agreements thus far.Footnote 85

The discussion above suggests that the perception amongst a large number of developing countries was that the texts were imbalanced against the interests of developing countries and that the chairs of NAMA and the TNC suffered from some errors of judgement that would bias the outcomes in favour of the developed countries. In the conclusion below, we will summarize the three reasons advanced in this paper for the collapse of the July 2008 ministerial meetings and then make some policy recommendations for WTO members.

4. Conclusion: policy recommendations

The paper has argued that one of the important reasons for the failure of the end July Ministerial meetings has been the persistence of protectionism within the EU and the US. As the negotiating process continued both the EU and US, working closely together, increased the pressure on developing countries, particularly the major emerging markets, to open their markets, in agriculture, NAMA, and Services, whilst ensuring that they accommodated their particular sensitivities. The second reason for the failure of the end of July ministerial meetings was argued to be the return to a small group approach (the G7) reflecting the power politics, and ‘principle supplier’ approach of the past. The G7 Ministers failed to agree to the ‘Lamy Package’, and Pascal Lamy declared at the TNC on the 29 July that the G7 Ministers had failed to reach agreement on modalities on agriculture and NAMA. Pascal Lamy stated that he was not ‘throwing in the towel’. He called for the progress made during the course of the Ministerial Meetings to be ‘preserved’ and for the membership to begin a process of reflection.Footnote 86 The third reason for the failure that the paper offers is the imbalanced draft texts, particularly between agriculture and NAMA, with the NAMA text failing to reflect adequately the views of the members. This is partly ascribed to the role of the chair of the negotiating group who by his own admission decided at the very outset, in his first draft text, to determine the level of ambition himself.

We make three recommendations to address the underlying causes of the collapse of the July 2008 ministerial meetings.

Firstly, the success of the next attempt to advance the Doha negotiations will also require that the EU and US take account of the development interests of the large and smaller developing countries and not simply try to advance their own commercial interests. Fairness and balance in the negotiations will require that the large number of exemptions the developed countries have demanded to accommodate their agriculture sensitivities are reciprocated in providing similar flexibilities to developing countries to protect their poor farmers and industrial workers.

Secondly, the WTO would need to think carefully about how it constitutes small groups in the future to advance the negotiations. China, India, the US, and the EU can claim to be part of any small group that is created to broker a deal because of their size but the interests of the rest of the membership have to be represented in any negotiating group. The model of small groups which includes members simply on the basis of their economic and political weight or ‘principal supplier approach’ is not suited to the diversity of economic interests and the political expectations of members to be represented and included at every stage of the negotiating process.

The WTO since the onset of the Doha Round, and particularly after Cancun, has evolved a rich tapestry of alliances or groups, especially amongst the majority of developing countries. These groups can play a constitute role in building joint negotiating positions and convergence among the membership. Pascal Lamy, the then Commissioner of the EU, had acknowledged the positive role of developing country groups in the WTO; after Cancun, when he compared the G20 to a Trade Union legitimately representing its members, and subsequently in Hong Kong, where the deal was brokered in the ‘Green Room’ that included representatives of the different groups, including the G33, the ACP, Africa Group, and the LDCs. Thus, it is only fair that the ACP, Africa Group, the G33, the NAMA 11, the Cotton 4 and the LDCs are also represented in any future negotiating group.

Thirdly, both Tallberg's and Odell's studies (discussed above) of the role of the chairs suggest that formal leaders can positively enhance the efficiency of the negotiations by transforming competing proposals into single texts and forging agreements. This positive and efficient role of the chairs in WTO negotiations can be restored in the WTO by studying the more successful efforts of previous chairs that have enjoyed wide support amongst the membership, such as that of the chair of the agriculture negotiations, in the period before and including the WTO July 2008 ministerial meetings. In addition, the WTO could develop a code of conduct for the chairs of the negotiating groups, based on its own rich experience of the performance of previous WTO chairs.

Developing Countries should continue to strive to conclude the Doha Round on its development mandate. Developing countries must again pickup the pieces of the failed ministerial meetings at the end of July 2008 and the failure again at the end of December, as they have done at each stage of the Round, after the collapse in Cancun, then again after the suspension of the Round in July 2006, and once more after the G4 Potsdam collapse in June 2007. They must reflect and learn from their experiences. They must rebuild their technical and organizational capacity and strengthen their alliances. And they must march on to the next phase of the struggle to achieve a fair, balanced, inclusive, and development oriented outcome in the Doha Development Round. They should not rest until the promises of development in the Doha mandate have been fulfilled.

Appendix 1