Introduction

Many developing countries with low state capacity face the challenge of illicit activities within and on the margins of their borders, among them, drug hubs. Drug hubs are understood as relatively stable centres of crop cultivation destined for the production of illicit drugs, such as cocaine.Footnote 1 Economies of scale linked to the production of drugs develop in these territories, as do related illegal activities and systems of protection. The latter include both parastatal groups that exercise coercion and violenceFootnote 2 and also the populations that inhabit those territories, which become part of the value chain of illegality.

The origin of illicit economies has generally been understood as a consequence of limited stateness and the presence of challengers to the state. On a subnational level, however, large-scale illicit activities, such as the intensive cultivation of coca, have not emerged in all territories where there is little state presence and capacity to offer basic state services. In Peru, coca has been cultivated since pre-colonial times; at the beginning of the twentieth century it was still cultivated for the legal exportation of cocaine.Footnote 3 Nonetheless, only certain valleys emerged as drug hubs after cocaine was declared illegal in 1978.Footnote 4

This article seeks to explain why the frequent association of low stateness with the origin of illicit activities can be deceptive. Likewise, it argues that the formation of a drug hub can be explained by a particular type of state experience in the territory, transforming the territory and creating the conditions, at a given moment, for the establishment of illegal economies prompted by external factors. Although the territorial conditions produced by a previous state experience are not sufficient to explain, for example, the arrival of drug trafficking in the Peruvian Amazon, they are necessary for understanding why only certain territories of the Peruvian rainforest became areas of high levels of violence and illicit production of coca.

This paper examines the case of the Alto Huallaga valley in Peru from 1960 to 1980 to explain how the territorial conditions for the emergence of a drug hub were created not by the absence of the state but by failed attempts at state developmentalism in the Peruvian Amazon. In the Alto Huallaga, the Peruvian state implemented developmentalist policies of productive transformation of the territory through expansion of the agricultural frontier (i.e. increase in the available arable land) in the tropical Amazon.Footnote 5 Failed attempts at developmentalism also took place in other Andean countries in the 1960s, with colonisation projects and territorial integration of their respective Amazonian territories.Footnote 6 The Chapare in Bolivia and the Putumayo in Colombia also underwent this process. By the late 1970s they, along with the Alto Huallaga, would become the world's most important illegal coca drug hubs.

This article argues that state developmentalism (the result of the uncritical and inappropriate application of ‘scientism’ – an undiscerning belief in scientific method – to social and territorial development) failed in Peru's Alto Huallaga, and led to unintended consequences in the territory that enabled the establishment and expansion of illegal crops, such as coca. One such consequence was the creation of an enclave of thousands of poor Andean peasant families who, having relocated from the Andes to the Amazon, did not achieve self-sufficiency as small-scale farmers, and therefore became dependent on the state. Another consequence was the ecological transformation of the territory from rainforest to a deforested space with degraded land, useless for growing any crop other than coca. Both these conditions would be crucial for the configuration of the Alto Huallaga into a drug hub when the specific re(articulations) of the international drug market took place in the 1970s.

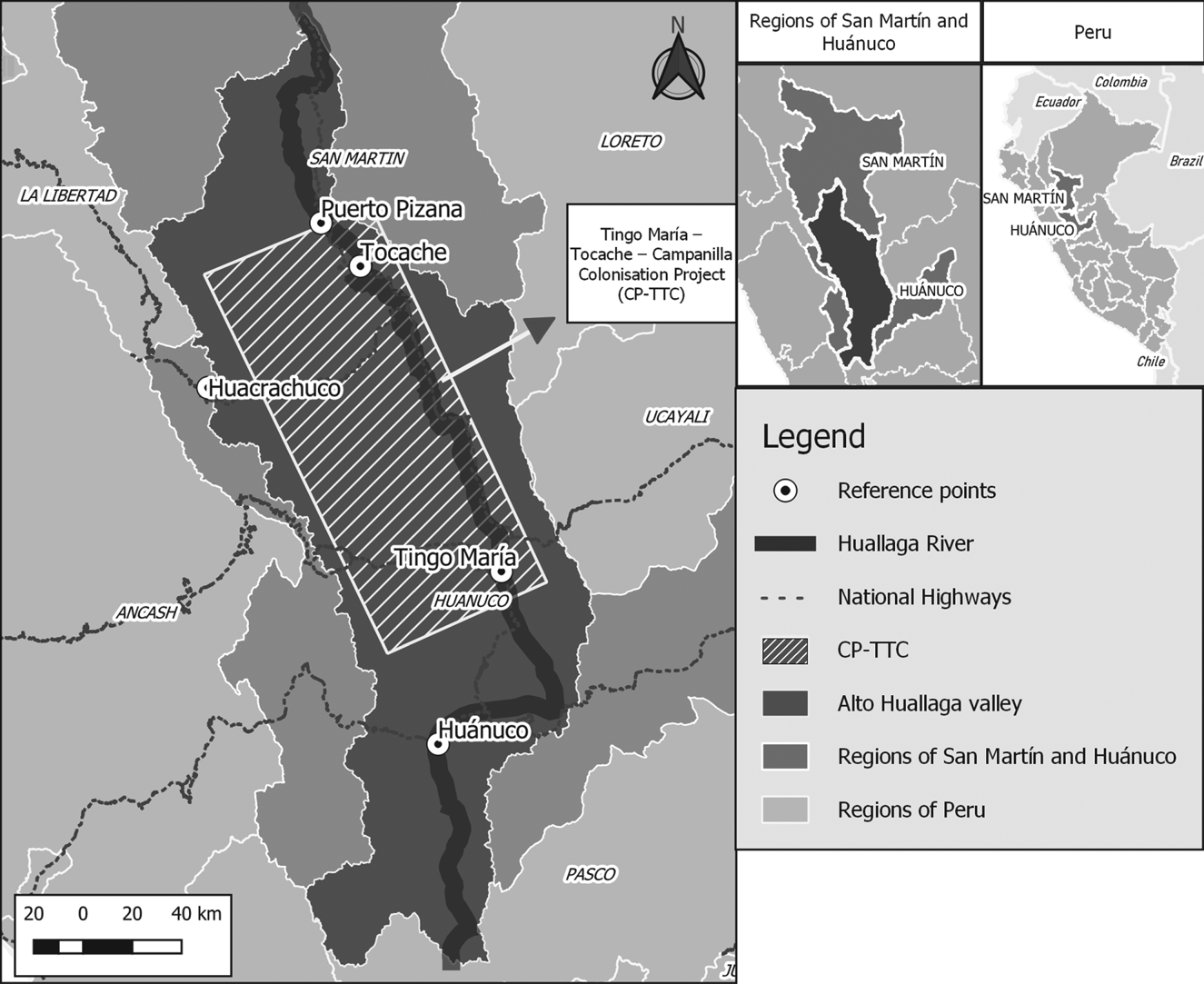

The Alto Huallaga is located in what is called the Selva Alta,Footnote 7 in the Mariscal Cáceres and Leoncio Prado provinces of the regions of San Martín and Huánuco, respectively (Map 1). During the late 1970s, the valley came to produce more than half of the world market's coca and coca paste.Footnote 8 These characteristics have made the Alto Huallaga a popular case study for studies on drug trafficking.Footnote 9 However, studies on the origins and formation of the Alto Huallaga as a centre of drug production remain scarce.Footnote 10 Moreover, while the macroeconomic and social failure of the Peruvian state's developmentalist project in the Alto Huallaga during this period has been discussed,Footnote 11 how the local territory experienced the presence of the state, and what the unexpected consequences of this experience were for the creation of illegal economies, have been less analysed. In particular, the relationship between the failure of this developmentalist project in the Alto Huallaga and the expansion of illicit coca cultivation in the late 1970s, which made the Alto Huallaga the main source of illicit coca in the world until the late twentieth century,Footnote 12 has not been examined.

Map 1: Location of the Alto Huallaga Valley in Peru.

Sources: Drawn by Kelly Gómez, with reference to Aramburú, ‘La economía parcelaria’ and Peruvian geographical data (http://geoservidorperu.minam.gob.pe/geoservidor/download.aspx).

This study follows an empirical case study approach due to the advantages it offers in developing an effective dialogue between theory and evidence.Footnote 13 This approach does not argue that the results of a specific case can be automatically extrapolated to other cases. However, carrying out an in-depth study of a case and contrasting it against theory allows for the problematisation of certain associations, such as that between the origins of illicit activities and the lack of state presence. This problematisation helps refine questions, pose new hypotheses, modify theoretical perspectives on a social phenomenon, offer nuance and detect anomalies and voids in previous theories.Footnote 14 Therefore, even without the development of a systematic comparison, this approach contributes to problematising, through new ideas and perspectives, other cases that share similar ‘contextual characteristics’.Footnote 15 The examination of the Alto Huallaga case can thus shed light on similar cases in the Andes from the second half of the twentieth century. In both Bolivia (Chapare) and Colombia (Putumayo), governments in the 1950s undertook similar colonisation programmes in rainforest areas to promote economic development and expand the agricultural frontier, with consequences similar to those in the Alto Huallaga. Both territories became, a decade later, the biggest centres for illegal coca production in their countries.Footnote 16 In sum, the Alto Huallaga is a ‘telling’ case,Footnote 17 insofar as the particular circumstances surrounding it serve to make us rethink the previously predominant theoretical relationships regarding a phenomenon, and contribute to the future analysis of other cases.

The empirical approach in this case study was mainly research on archive and secondary material. The archive material on the Alto Huallaga during the period studied includes technical documents written by state actors and their advisors during the period 1962–83.Footnote 18 These primary sources were triangulated with other materials, such as the national censuses, technical studies from the Oficina Nacional de Evaluación de Recursos Naturales (National Office for the Evaluation of Natural Resources, ONERN) and the presidential addresses of the period, as well as with interviews with public servants who participated in the Amazon colonisation programme.Footnote 19

The article is organised in seven sections. Following the Introduction, the second section presents the theoretical concepts with which this article approaches the case study. The third section explains the national and international contexts in which the impetus for state developmentalism emerged. The fourth section shows the transformation of the Alto Huallaga through state action and the creation of an enclave of poor settlers. The fifth section examines the establishment of socio-ecological conditions that enabled the expansion of illegal crops. The sixth section analyses how these conditions interacted with the wider context of rising international demand for cocaine to make the Alto Huallaga into an important drug hub. Finally, the seventh section offers the study's conclusions.

Developmentalism in the Amazon and the State Effect

Much of the literature which addresses stateness and illegality has depicted them as mutually exclusive.Footnote 20 That is to say, illegality expands in subnational territories where there is limited state presence or control. Guillermo O'Donnell calls these ‘brown areas’, which, despite being part of democratic regimes, are not completely controlled by the rule of law that governs at a national level.Footnote 21 The origin of territories with a high incidence of illicit activities has therefore tended to be explained as a consequence of limited state capacity,Footnote 22 or of the presence of challengers to the state that counterbalance the impact of state presence.Footnote 23 Drug trafficking has found fertile ground for the development of its activities in these ‘brown areas’.Footnote 24 The existing literature argues that this is in part due to the absence or, at the least, the weakness of the state that allows traffickers to operate without many obstacles, imposing their will either through violence or through the corruption of local government actors. This literature also emphasises the threats that this illicit activity – such as crime, violence and corruption – pose to the state in specific territories.Footnote 25

The emphasis on the mutual exclusion of state presence and illicit activities, however, hides the possible existence of connections between particular forms of state presence and the emergence of these activities. A growing literature exists that argues that illicit activities are not necessarily external to the action of the state, which limits itself to reacting to them. On the contrary, it suggests that there is a synergy between state presence and the production and re-production of these same illicit activities.Footnote 26 More recent studies on crime and urban violence have underlined the complicity of members of the state in illicit activities, through practices of corruption and abuse.Footnote 27 Additionally, the ‘time horizon’ in which the relations between state and illegality are observed must be considered. If the time frame in which the illegal activity is examined is short, explanations that involve large and slow-moving processes are lost.Footnote 28 Overall, the relationship between the origins of these illicit territories and the state's attempts to expand its domain over them has not been sufficiently explored.Footnote 29

This article offers an exploratory contribution to this lacuna in the literature on the origins of coca drug hubs in the Andean region. Our research argues that the origins of these drug hubs cannot be explained only by examining the agency of illegal actors or of criminal organisations, enabled by the apparent absence of the state in the territory at the time of their emergence. We argue that, during the 1970s – when demand for illegal coca increased – the expansion of the illegal coca economy in the Peruvian Amazon took place only in certain territories, such as the Alto Huallaga, despite the Peruvian state's limited presence in the whole region, as evidenced by, for example, the material infrastructure of schools, police outposts and health services.

The difference we seek to highlight in this article is that underneath the appearance of limited state presence lies what Timothy Mitchell calls a ‘state effect’.Footnote 30 The state is not only the visible and measurable structure expressed in schools, armies and social programmes; it is also the invisible powerful ‘effect’ of state practices that underlie those structures.Footnote 31 When the drug traffickers arrived in the Alto Huallaga, the apparently absent state was in fact present through the ‘effect’ of its previous intervention during a decade of failed colonisation, and that ‘effect’ was crucial for the expansion of the coca crop in the Alto Huallaga. As we mentioned before, this ‘effect’ can be observed only by expanding the time frame of the analysis.

As in many other nations, the developmentalism that the Peruvian state undertook in the Amazon from the beginning of the 1960s until the end of the 1970s was characterised by the search for economic development through state intervention.Footnote 32 Thus, the Peruvian state unsuccessfully sought to guide investment in the Amazon in a way that would promote modern agriculture, and thus contribute to a united and common vision of the national economy. As we expand on later, this state programme of developmentalism and modernisation in the Amazon failed not only due to the administrative and financial incapacity of the state to transform the forest into productive territory, but also due to the excessive enthusiasm placed by the state on scientism applied to the development of the territory at the local level.

The application of scientific knowledge undoubtedly leads to an increase in infrastructural capacity in a territory.Footnote 33 However, scientism is characterised by an excessive confidence in the potential of scientific knowledge and instruments to transform local territories. Indeed, many states fail not because of a lack of scientific knowledge, but because of overconfidence in this knowledge, ignoring that this type of scientific knowledge frequently simplifies and standardises complex local realities.Footnote 34 The outcomes have oftentimes ended in catastrophes with high social and environmental costs, such as in the case of ‘forest death’ in Germany, a consequence of the development of scientific forestry in the late eighteenth century. James Scott argues that, after relative success in the medium term for monoculture forest plantations, the German authorities, when faced with declining yields, had to confront the reality that a natural mix – of ‘productive’ trees, amidst other trees, undergrowth and debris – constituted an extremely subtle and complex ecology that provided the vital nutrients for tree growth.Footnote 35

For David Turnbull, the problem with scientism is that it is based on rulers’ confidence that scientific knowledge can travel without difficulty to other contexts, beyond its place of production, beyond its laboratory.Footnote 36 Furthermore, this confidence has led states with far less capacity than the German authorities described by Scott to construct the ‘fantasy’ that they can undertake large-scale territorial and social transformations by reproducing this knowledge.Footnote 37 Scientism creates the illusion that the state, while weak in the past, can now undertake large-scale transformations by relying on the application of scientific knowledge.

No Peruvian leader better embodies state enthusiasm in the 1960s for the ability of scientism to transform significant territories in the Peruvian Amazon than President Fernando Belaúnde Terry. This enthusiasm was probably the result of his training, first as an engineer in France and then as an architect in the United States.Footnote 38 He admired the watershed planning experiment carried out by the Tennessee Valley Authority in the 1930s. This agency, established by the US government in reaction to the Great Depression, became emblematic of a conception of state planning based on science to foster economic development.Footnote 39 Thus, the government of President Belaúnde (1963–8) promoted the application of a set of technical planning instruments that were spread and applied throughout Latin America.Footnote 40 The ‘illusion’ that the Peruvian state could use scientific knowledge to carry out previously impossible transformations in the Amazonian territory legitimised large-scale deployment of the state in the Amazonian region that began with his government and continued until its failure at the end of the 1970s. Financial and technical resources from the networks that disseminated scientism, along with strategies encouraged by the growing international development industry, added to this enthusiasm.Footnote 41

The failure of this attempt at state developmentalism, however, left a ‘state effect’ on the territory, along with interconnected social and ecological components that led to the formation of a drug hub towards the end of the 1970s. In the rest of the article, we seek to explain how the failure of this planning ‘illusion’ and the conquest of the Amazonian frontier produced these articulated socio-ecological conditions in the Alto Huallaga. On the one hand, we have the creation of an enclave in Amazonian territory of thousands of poor Andean peasant families attracted by the state narrative of ‘conquest’ and ‘domestication’ of the Amazonian territory, who could not support themselves. On the other hand, these peasant settlers faced a deforested ecological space, with soil too poor to cultivate any crop besides coca. By the end of the 1970s, the consequences of the state's intervention, combined with the arrival of drug traffickers into the region in the mid-1970s, produced the Alto Huallaga drug hub and the subsequent control of the newly conquered frontier by illegal actors.

Colonisation of the Amazon and Construction of Socio-Ecological Conditions for a Drug Hub

In Peru, the state had long yearned for the ‘conquest of the Amazon’. Under different governments, from the late nineteenth century, the state promoted the colonisation of the rainforest. Laws promoting the colonisation of the Peruvian Amazon in the first half of the twentieth century did not have the expected impact. Indeed, according to the population census of 1940,Footnote 42 the Amazonian regions of San Martín, Madre de Dios, Loreto and Amazonas represented only an estimated 5 per cent of the Peruvian population. Nonetheless, during the 1940s, state interest in connecting the Amazon with the rest of the country grew.Footnote 43

In the second half of the twentieth century, state colonisation reached its peak in terms of investment and programme implementation. These state efforts were in response to both internal and external factors. The colonisation of the rainforest represented an expansion of available agricultural lands as a way of appeasing peasant demands for land in the highlands.Footnote 44 Colonisation also represented the promise of feasible agrarian reform, given the opposition of the elites to structural changes in land tenancy in Andean areas.Footnote 45 In addition to these internal factors, the United States, which feared the onset of communism in Latin America, had an obvious interest. Immediately after the Cuban Revolution, the United States began supporting internal colonisation initiatives in Andean countries, because, at the height of the Cold War, peasant poverty and the Cuban example were seen as possible triggers for the emergence of more pro-communist movements in the hemisphere.Footnote 46

In response, the United States supported development projects through the Alliance for Progress, established by John F. Kennedy in 1961. The Alliance established a substantial ten-year foreign aid programme of US$100 billion for Latin AmericaFootnote 47 managed under the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB). This international financial support accelerated programmes of agrarian reform and colonisation of Amazonian territories in countries such as Bolivia, Colombia and Peru. Their governments intensified the construction of highways, offered expansive programmes of agrarian credit and promoted internal migration programmes that provided property titles and technical assistance for agriculture and livestock breeding. In 1963, Bolivia received US$78 million from the IABD for its colonisation projects, which were concentrated in the Chapare.Footnote 48 Colombia became the second largest recipient of US aid in Latin America during this period.Footnote 49 One of the main programmes in Colombia was the colonisation of the Putumayo, which began in 1964. In just a single year later, hundreds of kilometres of highways were built, around which settlers established their new homes.Footnote 50 The Peruvian state also designed and supported similar programmes in the Alto Huallaga, such as the establishment of a colonisation zone, thanks to a US$127 million dollar loan from the IADB. Paradoxically, these three areas of colonisation became, a decade later, the largest coca and cocaine production centres in their respective countries.

In this international context, Belaúnde was the president who most enthusiastically championed the integration of the Amazon into the national territory as part of a process of what he called the ‘Conquest of Peru by the Peruvians’.Footnote 51 He described the Amazon as ‘a land without men for men without land’, making invisible the indigenous peoples who already lived in those areas. Although this view was already quite widespread and accepted in the country,Footnote 52 the slogan entrenched notions that the Amazon was a vast and rich territory, wasted and poorly used by its original, ‘savage’ inhabitants. For Peru's political elites, the Amazonian territory has commonly conjured up the idea of an uninhabited space full of natural resources waiting to be exploited.Footnote 53 In addition, Belaúnde was very much convinced beforehand of the results to be delivered by the projects of colonisation that he supported, and of their technical and scientific underpinnings.Footnote 54 Thus, he remarked that ‘the profound studies of colonisation, executed with the collaboration of competent international organisms, will allow us, once put in practice, to absorb the great migratory movements that must be produced in order to achieve a better democratic distribution in Peru’.Footnote 55 Despite President Belaúnde's hopeful illusions, those studies provided incorrect information on the agricultural productivity of the Alto Huallaga, and its colonisation encountered various obstacles that hindered its success. That same colonisation later on also created favourable conditions for the development of the Alto Huallaga as a drug hub.

Production of an Enclave of Poor Settlers

Road Infrastructure

The increase in public investment during Belaúnde's presidency was fundamental for the construction of highways, which proved key for the colonisation of the Amazon. Public investment went from almost 5 per cent of public spending between 1960 and 1963 to an estimated 20 per cent between 1964 and 1968.Footnote 56 Public investment in highways and ports increased eightfold between 1960 and 1967.Footnote 57 Between 1955 and 1965, the Amazonian road network grew by more than 440 per cent, while that in the rest of the country grew by only 72 per cent.Footnote 58 Even so, the contrast between Belaúnde's government and previous governments is clear. Between 1964 and 1968, 545 kilometres of highways were built, which represented a 40 per cent increase compared to highway building between 1939 and 1964.Footnote 59 Within this diversity of infrastructure initiatives, the most ambitious was, without a doubt, the construction of the Carretera (Highway) Marginal, which was to enable the colonisation of the Peruvian Selva Alta.

Richard Kernaghan argues that the Huallaga's modern history begins with the construction of the Carretera Marginal.Footnote 60 Its construction incorporated the Alto Huallaga into the country's transport infrastructure and opened it up to migration and large-scale agriculture. This highway was foundational in the construction of this enclave. Until this point, spontaneous colonisation had taken place on the western banks of the Huallaga river. The few improvements to road networks that were made in the first half of the twentieth century in the Amazon privileged the city of Tingo María (on the west bank of the river), making it the point of entry into the Central Amazon.Footnote 61 Indeed, at the beginning of the 1940s, the coast, the highlands and the Amazon were for the first time connected by road with the construction of the Central Highway to Aguaytía and Pucallpa through Tingo María.Footnote 62 Other projects to connect the south of the Amazon (the Cuzco–Puerto Maldonado highway) with the north (the highway that was meant to connect the port at Pimentel with the Alto Marañón) began during that same decade.Footnote 63 These transformations, however, were inconsequential compared to those that came shortly after: the construction of the Carretera Marginal in the 1960s, connecting Tingo María and Tocache along the eastern bank of the Huallaga river (see Map 1).

The Carretera Marginal opened up a new and important agricultural frontier in the Amazon,Footnote 64 connecting the Central Amazon with the coast and the rest of the country in a completely new way. With the construction of this highway, the Belaúnde government incorporated the San Martín region into national colonisation plans, just as Huánuco had been for decades. Thus, the Carretera Marginal was fundamental in opening up the Selva Alta frontier to increased colonisation.Footnote 65

Colonisation Projects

Colonisation projects were not new in the Alto Huallaga. The colonisation of these territories had been undertaken through public and private efforts that date back to the nineteenth century.Footnote 66 The largest state colonisation effort in the Alto Huallaga and the Selva Alta, however, was under Belaúnde: the Tingo María–Tocache–Campanilla Colonisation Project, which began in 1966.

This project covered 456,800 hectares.Footnote 67 Beginning in 1966, it was intended to settle 4,227 families in a designated area between San Martín and Huánuco. Its borders were Campanilla in the north and the estuaries of the Caracol and Rondos rivers in the south, with the Cordillera Oriental as the eastern border and the Cordillera Central as the western one. The project area extended over a large portion of the José Crespo and Castillo districts in the province of Leoncio Prado, the Cholón district in the province of Marañón, both in the Huánuco region, and the districts of Uchiza and Tocache in the province of Mariscal Cáceres in the San Martín region.Footnote 68 The Carretera Marginal was to cut across this area for 175 kilometres.Footnote 69 Total investment in the colonisation project was approximately US$325 million, excluding the construction costs of the Carretera Marginal.Footnote 70 The IADB's loan was about a third of this amount (US$119 million) and the rest was covered by the public treasury.

It was not anticipated that with the construction of the Carretera Marginal families would independently begin to move to the colonisation zones. Yet at the beginning of the project, more than 5,400 families were already settled in the designated area. That is to say, right from the start, 28 per cent of the estimated absorption capacity of migrants for the area had already been met.Footnote 71 The rapid overload of the space designated for colonisation, the settlers’ difficulty in adapting to the tropical climate and, particularly, the discovery of the soil's true quality started to become an issue for agriculture.

Incorrect assessment of the soil quality was certainly a central element in the settlers’ disappointment and the failure of colonisation in the Alto Huallaga. Research conducted by the Estación Experimental de Tingo María (Tingo María Experimental Station, the largest US tropical research facility in the western hemisphere) had supported the implementation of a programme of colonisation, based on its assessment of the productive potential of the area.Footnote 72 The Ministerio de Fomento y Obras Públicas (Ministry of Development and Public Works), in particular the office of the Servicio Cooperativo Interamericano de Fomento (Inter-American Cooperative Service for Development, SCIF),Footnote 73 which had undertaken an assessment of the soil in 1962 and praised the virtues of these territories’ soils for agriculture, added to the enthusiasm for the region's agricultural potential. The SCIF document, Evaluación e integración del potencial económico y social de la zona Tingo María–Tocache, Huallaga Central (Assessment and Integration of the Economic and Social Potential of the Tingo María–Tocache Zone, Central Huallaga),Footnote 74 was key in driving the colonisation of the area on the eastern bank of the Huallaga river. In its introduction, the study optimistically indicates that close to 84 per cent of the soil could be used for the purposes of agriculture and livestock, and that ‘the ecological conditions of the Tingo María–Tocache region are particularly favourable for the development and progress of human, vegetable and animal life’.Footnote 75 This type of conclusion about the agricultural suitability of the territory – overestimating its productive potential – served to legitimise plans to colonise the Alto Huallaga. As can be observed in Table 1, the potential use of land for agriculture in the 1962 study contrasts strongly with the smaller areas indicated as suitable in the 1964–70 and 1972 studies. The same applies to land suitable for livestock breeding.

Table 1. Quality of Soil in the Alto Huallaga (percentages)

Source: Compiled by the authors from SCIF, Evaluación e integración, pp. 46–7; CENCIRA, Diagnóstico socio-económico, pp. 54–5.

Appraisals of the fertility of the Alto Huallaga's soil at the beginning of the 1960s created another illusion for the Peruvian state. The scientific dissemination of agro-ecological analysis and the institutionalisation of certain classifications and methods spread throughout Peru from the US Soil Conservation Service, today the National Resources Conservation Service. However, knowledge of the Amazonian territory, and in particular of its soil, was officially undertaken by the Peruvian state only in 1962 with the creation of the ONERN. Unfortunately, it took this office many years to produce research on the natural resources, including accurate and detailed information on soil quality. At the beginning of the 1970s, experts from the Centro Nacional de Capacitación e Investigación para la Reforma Agraria (National Centre for Training and Research for Agrarian Reform, CENCIRA) reported that the results from the soil studies in the Alto Huallaga were unreliable and could not successfully determine agricultural suitability.Footnote 76 More detailed data began to be gathered in the area only in the 1970s,Footnote 77 and, according to the ONERN's own records, it was not until the beginning of the 1980s that it conducted semi-detailed studies of the area.Footnote 78

Thus, the Tingo María–Tocache–Campanilla colonisation project was implemented based on an overestimation of the soil's fertility in the Alto Huallaga basin. According to Turnbull, state enthusiasm frequently ignores the fact that scientific knowledge is not instantly transferable.Footnote 79 The archaeologist Betty Meggers, whose work may be criticised for its environmental determinism regarding the development of Amazonian cultures, had already warned in the 1960s about the thin layer of fertile topsoil in humid tropical forests.Footnote 80 Nevertheless, her analysis was not able to stop or in any way temper the colonising and developmentalist momentum of the state during that period.

During this colonisation project, the productivity of the land of the Selva Alta went from illusion to nightmare for the settlers, who suffered regularly from crop productivity problems. This situation was made worse by the low yields of crops – such as rice and maize – recommended by the colonisation programmes, due to the overestimation of the soil's fertility. The state prioritised rice because, in addition to its adaptability to different climates and soils, it offered labour opportunities, while maize was privileged for its protein value.Footnote 81 The importance of both crops was so great that, by 1972, they were the main products qualifying for agricultural loans.Footnote 82

Despite the problems of colonisation in the Alto Huallaga, settlers continued to arrive and establish new towns, thanks to the opening up of the frontier and of the Carretera Marginal. CENCIRA's review of the project warned of the numbers of migrants in the colonisation zone. Towards the conclusion of the project, in 1973, 4,227 families were expected to be settled, which meant a total of 23,400 people (with the rule of thumb of five members per family).Footnote 83 However, according to the 1972 census,Footnote 84 the project's rural zone alone had a total of 29,998 inhabitants – an excess of 6,500 people.Footnote 85 What is more, between 1962 and 1966 (the year that the project began) at least 600 families had already occupied land reserved for the colonisation project, without state authorisation.Footnote 86 In sum, the population of the provinces that constitute the Alto Huallaga grew more than tenfold between 1940 and 1981 (Table 2). From 1961 to 1972, in just a single decade, the population of the Alto Huallaga doubled and, by 1981, when coca production peaked, the population had tripled. During these two decades, due to the state's push for colonisation, the Alto Huallaga had the highest population growth rates in the whole Amazon.

Table 2. Population Growth in the Alto Huallaga (1940–81) (inhabitants)

Source: Compiled by the authors from census data (see note Footnote 19).

Following the overthrow of Belaúnde by the Gobierno Revolucionario de las Fuerzas Armadas (Revolutionary Government of the Armed Forces) in 1968, the new government reoriented the colonisation projects.Footnote 87 Between 1968 and 1980 there was a shift in state priorities regarding the Amazon. Thus, although the Alto Huallaga was still important for the state, it ceased to be a priority. The new government focused on state exploitation of oil, mainly in what is today the department of Loreto.Footnote 88 However, this shift in priorities did not mean that the colonisation projects ended altogether. On the contrary, they carried on, although with two main modifications. First, individual and multifamily settlement, including some agricultural cooperatives, a characteristic of the original programme, made way for the model of Cooperativas Agrarias de Producción (Agrarian Production Cooperatives, CAPs) and Cooperativas Agrarias de Servicio (Agrarian Service Cooperatives, CASs).Footnote 89 These were medium- and large-scale cooperatives administered by the state. The second change pushed by the military in the area of colonisation was a reorientation of the project towards meat livestock farming.Footnote 90

Ecological Change in the Alto Huallaga

State colonisation policies in the Alto Huallaga between 1950 and 1980 coincided, from the 1950s onward, with massive deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon.Footnote 91 This deforestation enabled intensive coca cultivation for the illegal cocaine market. In this section, we will see how the state policies discussed above transformed and damaged the Alto Huallaga's ecological space. Following the logic of the governments of those years, in particular that of Belaúnde, Peru's main priority was the expansion of the agricultural frontier and ‘the re-establishment of the man–land balance … with 2,800 m2 (of farming land) per inhabitant’.Footnote 92 The Amazonian forest was seen as an ‘unlimited space for cultivation and stock rearing’.Footnote 93 This expectation was approved of by well-regarded economists of the time, such as Eduardo Watson and Chungsuk Cha, who supported the concept of the Amazonian region as an extractive base. Their ideas were disseminated in a round table organised by the Banco de Crédito del Perú (Peruvian Credit Bank) in 1971.Footnote 94

In the Alto Huallaga, the Tingo María–Tocache–Campanilla colonisation project seriously aggravated deforestation and soil deterioration. The valley's fragile ecology was affected by the type of ‘slash and burn’ migratory agriculture practised on a large scale by the wave of Andean settlers who arrived as part of the colonisation project. Due to the poor quality of the soil for agriculture and the ecological system, productivity was lower than in other territories, and the settlers needed to clear and obtain large plots (of up to 10 hectares) to survive.Footnote 95 Although indigenous peoples also practised ‘slash and burn’ agriculture, theirs was done on a smaller scale (plots of between 0.5 and 1.5 hectares) that guaranteed the regeneration of the forest, and combined agriculture with hunting, fishing and foraging activities.Footnote 96

Furthermore, in the 1970s, the military government of Juan Velasco Alvarado reoriented the colonisation projects towards livestock breeding for meat. Two factors led to this reorientation: first, the realisation that the soil was not as suitable for agriculture as was originally thought; second, the government's economic policy of import substitution industrialisation (ISI) that sought Peruvian self-sufficiency in meat production.Footnote 97

To introduce livestock husbandry on a large scale, the mechanised deforestation of a huge area with bulldozers was necessary: the slash and burn deforestation process begun under the previous colonisation efforts was intensified. Around 1971, the IADB and the World Bank opened lines of credit for large-scale livestock breeding via the Banco de Fomento Agropecuario (Banco of Agricultural Development). By the mid-1970s, loans for livestock breeding activities represented more than 60 per cent of the total debt of at least 15 Alto Huallaga CAPs, CASs and businesses.Footnote 98 The optimal average of deforestation was approximately one hectare per head of cattle.Footnote 99 The fields, once cleared, were first used for the cultivation of annual crops and then converted into pasture. However, the returns from the mechanised clearing were not as expected. At least 2,000 hectares strategically located near roads were already seriously compromised and ecologically damaged.Footnote 100

As a result of the total deforestation of the aforementioned area by the livestock breeding cooperatives, the ecological balance was destroyed. At the beginning of the 1980s, this damage was evident in crop yields in mechanically deforested zones, which were 30 per cent lower than in zones where manual deforestation took place.Footnote 101 Mechanised deforestation produces a greater loss of the already thin layer of fertile soil that humid tropical forests possess, impeding their regeneration. With that layer gone, there is an increase in erosion and in soil acidity.Footnote 102

In sum, during this period, the Amazonian forest was valued primarily because its soil offered opportunities for agricultural activity, and only secondarily for the use of the forest itself. The natural forest was seen as having little value for the state institutions in charge, which considered that the tropical forests were ‘too heterogeneous’ and that ‘very few of the species had actual value, which has given way to selective exploitation’.Footnote 103 However, with time, global concern for the environment found a home in organisations such as the ONERN.Footnote 104 The first warnings began to emerge about the loss of great swaths of natural forests and what this loss meant in terms of alterations to the ecological balance and destruction of the flora and fauna, integral to the ecosystem.Footnote 105 As a result of these concerns, the ONERN commissioned the first ecological map of Peru in 1975.Footnote 106 This map estimated that more than 4.5 million hectares of natural forest in the rainforest region had been destroyed by migratory agriculture during the previous decades. The constant rotation of plots by a high number of settlers, combined with the always-growing demand for land, did not allow the soil sufficient time to rest in order to recover its typically thin fertile layer (due to its tropical characteristics), and thus contributed to ecological deterioration.

It has proven difficult to arrive at a detailed calculation of the deforestation in the Alto Huallaga during this period. However, in 1975, it was estimated that 150,000 hectares per year were being deforested.Footnote 107 Carlos Aramburú and Jazmín Tavera offer an estimate of the deforestation in the Alto Huallaga during this period, by calculating the percentage of agriculture that was practised on deforested zones.Footnote 108 They estimate that, between 1962 and 1972, agriculture on deforested land in the Alto Huallaga rose from 42 per cent to 76 per cent.Footnote 109

Paradoxically, the increase in erosion and acidity of the soil – harmful to rice, maize and livestock – was favourable for coca cultivation, because coca is one of the few crops that adapts well to damaged and acidic soil. Furthermore, coca does not require forest cover (as do coffee and cacao, for example), and so deforestation did not affect its cultivation. Thus, following deforestation, which was financed by state credit and spurred by the settlers’ agricultural practices, coca cultivation became an ideal alternative for the mass of peasants and poor settlers in the damaged land of the Alto Huallaga.

Growth of the Illicit Economy in the Alto Huallaga

This section explains how the socio-ecological conditions created by the failure of state developmentalism in the Alto Huallaga led to the valley becoming, in the 1970s, an ideal space for the new entrepreneurs in the illicit trafficking of drugs, the Colombians, who were responding to the increase in cocaine demand from the United States towards the end of the 1960sFootnote 110 and the impossibility of continuing to import cocaine from the south (Bolivia and Chile). Paul Gootenberg has pointed out that the presence of both coca and cocaine was not new in the area, nor in the country. On the contrary, valleys such as the Monzón in Huánuco (which, together with San Martín, hosted the colonisation project) and others, such as the La Convención and Lares valleys in Cusco, had been producers of cocaine at the beginning of the twentieth century, when it was legal. Not only did expanses of coca cultivation exist in these regions, but there were also significant cocaine factories oriented towards export and run by innovating entrepreneurs.Footnote 111 However, the scale of the illicit expansion of this crop in the peasant economy in the Alto Huallaga in the late twentieth century requires further explanation.

In the first half of the 1970s, demand for labour to work on coca fields rose in the colonised valleys of the Alto Huallaga in response to the increase in demand for illicit cocaine in the United States, coinciding with the time when the depletion of the soil in the Alto Huallaga became evident. The settlers who had depended on subsistence agriculture began to rely on coca cultivation as a source of cash.Footnote 112 The legacy of the colonisation efforts – a huge, and cheap, peasant workforce – in addition to the withdrawal of credit and technical assistance programmes in the Alto Huallaga in the late 1970sFootnote 113 combined with coca's unique productivity in deforested, depleted-soil territories to facilitate the installation of Colombian drug traffickers in the Alto Huallaga.

At the same time, Chile, which had been the pipeline for cocaine from Bolivia and Peru towards the United States, stopped playing that role.Footnote 114 Augusto Pinochet's coup in Chile in 1973, and his alliance with Richard Nixon, led to the arrest of important Cuban drug traffickers and the control of the Chilean ports. The Colombians took advantage of this restructuring of the cocaine market in the south and rearticulated Peru and Bolivia's cocaine market towards the north, to Colombia.Footnote 115 Colombian drug traffickers had already been entering the drug market from the 1960s, working together with Cuban drug traffickers in the refinement of coca for redistribution in the United States.Footnote 116

The increasing demand for cocaine market in the north, and the conditions put in place by the state in the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s, along with the fact that cocaine had been refined in the Tingo María area when its export was legal,Footnote 117 resulted in the production of coca leaf in the Alto Huallaga rapidly increasing throughout the decade. By the late 1970s, the Alto Huallaga had become a drug hub connected with Colombian drug cartels and the growing cocaine market in the United States. The illicit economy rapidly took over the valley and extended to other areas where coca production had previously been scarce or non-existent. Estimates of the cultivation of coca leaf in the valley towards the end of the 1980s vary considerably, ranging from 120,000 to 195,000 hectares dedicated principally to the production of cocaine.Footnote 118

In a deforested valley with low agricultural productivity, coca became the highest yielding crop. Prices for coca leaf destined for the drug trade were six times the prices for the coca destined for the formal market, which was limited given the state regulations. Furthermore, those prices were ten times that commanded by rice or maize, the crops promoted by the state. A study in Huánuco reported that income per family from the sale of coca and its by-products reached US$9,000 a year, whereas during the same period the families obtained only US$200 a year for the sale of rice and maize.Footnote 119 At the time, coca yields competed favourably with those of various other agricultural products that had been introduced in the area: it grew well in impoverished soil, it had a much higher frequency of cultivation (up to four harvests a year), it did not require large-scale investment, it employed a lot of low-skilled labour and it had easy market access.Footnote 120

Market accessibility improved with the arrival of subversive groups that provided effective protection for illegal trade in the 1980s.Footnote 121 The coca boom in the Alto Huallaga attracted organisations such as the Partido Comunista Peruano–Sendero Luminoso (Peruvian Communist Party–Shining Path, PCP–SL) and the Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Amaru (Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement, MRTA), which became active in the area in the early 1980s.Footnote 122 These organisations sought not only income for financing their respective armed struggles, but also political legitimacy. This legitimacy was to be obtained through offering armed protection against state interventions to eradicate coca and confiscate drugs: by protecting the illicit economy against the reach of the state, these subversive groups gained political capital.Footnote 123 The lucrative business of cocaine therefore allowed for the emergence of new leadership that obtained recognition and support from the peasantry, replacing the basic functions that the state had not been able to establish over the previous decades.Footnote 124 With this new leadership, drug traffickers and insurgents filled the void left by the state, imposing their own laws and norms, and administering systems of education, security and justice to the population.Footnote 125 A clear example is that of the drug trafficker Demetrio Chávez Peñaherrera, alias Vaticano, who was in charge of the provision of electricity, the construction of infrastructure and even social control in the town of Campanilla, that is to say, the northern edge of the Tingo María–Tocache–Campanilla colonisation project.Footnote 126 Thus, the Alto Huallaga valley, previously a focal point for targeted colonisation, now hosted wide open fields of coca leaf and centres of coca paste production.

Conclusions

This article has sought to rethink the relationship between stateness and the origins of illegal activities. The case study of the Alto Huallaga has been used to show that it is not necessarily the absence, but rather a particular type of state presence – in this case, former state presence – that created the conditions for the expansion of illicit coca crops when international demand increased in the 1970s. In the Alto Huallaga, the developmentalist project reached thousands of poor peasants in the Andes in the form of a state promise of ‘available land’ in the Amazon. Apart from this promise, the project built a long-distance highway and carried out colonisation programmes that resettled thousands of Andean families in the Amazon. All of this development was supported by a faulty technical analysis of tropical soil. The penetration of highways, the wave of arriving peasants and the complexity of the territory's ecology vastly exceeded the almost non-existent capacity of the Peruvian state in the Amazon, and its illusion of directing development according to its scientistic plans.

The failure of these colonisation projects left as a ‘state effect’ socio-ecological conditions in the territory that facilitated the emergence of a coca drug hub. First, the state created an enclave of poor and peasant labour, with a local economy highly dependent on the state. In 1981, the population of the Alto Huallaga was ten times higher than in 1940, and triple that of 1961. When coca prices rose, a majority of the Andean migrants who were a part of these colonisation projects, and those that settled spontaneously, introduced illegal coca into their crop regimes. Second, the colonisation projects resulted in large deforested areas with low-productivity, damaged soil. In this soil coca grew easily, unlike other crops such as rice or maize, which had been prioritised in the area by the state in previous decades.

This study concludes that a boom in international drug prices is not enough to enrol thousands of peasant families into an illicit market; neither is the existence of illegal entrepreneurs willing to link these peasants’ territories with illicit international markets in a context of weak state presence. Expanding the time horizon in the study of territories of illegality allows us to observe, from a broader perspective, what the state's intervention was and its ‘effect’ on the configuration of conditions that promote the establishment of hubs of illegality.

Reclaiming the Alto Huallaga from the violence of drug trafficking has not been an easy task. The region's shift to growing alternative, licit crops such as cacao, coffee, oil palm and heart of palm has been therefore called the ‘miracle of San Martín’, and it began only in the 2000s. This transformation has been thanks to a – probably unrepeatable – process that coincided with an increase in international prices for alternative crops and changes in drug trafficking routes in the new century. This process has also required enormous financial support from international collaborators, mainly USAID, and a long path of local institutional restructuring, that has included the participation of civil society and of local political elites.Footnote 127

In sum, this article seeks to contribute a more nuanced view of the relationship between the state and the origins of illegality. We have indicated that the Alto Huallaga is not an exceptional case. In cases such as the Chapare in Bolivia or the Putumayo in Colombia, similar state policies were developed, with broadly similar results. This study suggests the importance of examining the role played by state developmentalism and by the exaggerated confidence in scientific knowledge on the part of the governments of these countries (despite the weakness of their states) in the production of relatively similar socio-ecological conditions. However, despite these similarities, a systematic comparative study would require also taking into account the differences from these countries, such as the absence of subversive actors in Bolivia, or the presence of parastatal elites (combatting guerrilla forces) in Colombia. Further research could also productively apply the argument of the ‘state effect’ to other more contemporary forms of illegality, such as illegal mining, logging and different forms of smuggling.