This chapter explores Schubert’s Winterreise from a number of angles. First, under the heading of “Connecting Threads,” I consider overarching elements in text and music. Text and music do not necessarily coincide in all dimensions (such as their timeframe, or their structure), but may gain added power from being non-congruent. Secondly, I examine Schubert’s deployment of the “fingerprints” of his personal style: these too contribute to the intense impact of Winterreise.1 In setting the twenty-four poems of the finished cycle, Schubert not only created an alliance between music newly conceived for the purpose and Müller’s words; he also, importantly, formed an alliance of the words with core features of his compositional style at a ripe stage of its development.

In highlighting the detail of Schubert’s settings, I identify in some songs what I call the “crux,” containing the nub of what is expressed in the poetic text. Where the musical response to the poetry coincides with the crucial words uttered by the voice, such examples are among the most powerful in this category. Under various headings, I pinpoint specific topical references that help form the fabric of text and music.2 The intricacy of that combined fabric means that only a selection of examples can be discussed in detail. Table 10.1 provides an overview of all twenty-four songs for reference.

Table 10.1 Overview of text and music

| Song number/ Title | Key/Tempo | Mood/Musical topics | Motifs/Devices (text) | Motifs/Devices (music) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gute Nacht (Good Night) | d / Mässig | Somber/slow march; hymn-like (F, B flat); dreams (D) |

| Drone/trudging footsteps; neighbor-note motif (“x”); falling third motif (“y”); falling fourths; arpeggiation; minor/major |

| 2 Die Wetterfahne (The Weathervane) | a / Ziemlich geschwind | Ominous; grotesque; dance (Konzertstück) | Wind blowing; her house; mockery; faithlessness | Arpeggiation; trills; motif x; chromatic thread; minor/major |

| 3 Gefror’ne Tränen (Frozen Tears) | f / Nicht zu langsam | Grotesque march; Viennoiserie/dance; recitative | Tears falling; ice/heat; his heart | Semitonal motif; aug./dim. intervals |

| 4 Erstarrung (Numbness) | c / Ziemlich schnell | Antique style/canon, augmentation (mm. 26 ff.) | Ice and snow; frozen/melting; tears; his heart; past/present/memory | Motif x; moto perpetuo; chromatic threads; cadential delaying (v. 2); Neapolitan figure |

| 5 Der Lindenbaum (The Linden Tree) | E / Mässig | Hymnlike (E); storm; lullaby | Linden tree; dreaming; love; wind blowing | Major/minor |

| 6 Wasserflut (Flood Water) | e / Langsam | Slow quasi-march/dirge; lullaby | Ice and snow, wind; burning, melting; tears; her house | Arpeggiation; cadential delaying |

| 7 Auf dem Flusse (On the River) | e / Langsam | Slow march; antique style; lyrical (central episode) | [Water] rushing/still; past/present; memories; his heart | Partimento-type bass; remote modulations; motif x; minor/major |

| 8 Rückblick (A Look Backward) | g / Nicht zu geschwind | Impulsive motion (vs. 1 & 2, v. 5 ); fragility/ lullaby (vs. 3 & 4) | Ice and snow; birds, linden trees; past/present; inconstancy; her house | Rocking octaves; chromatic threads; motif y; hemiola; minor/major |

| 9 Irrlicht (Will-o’-the-Wisp) | b / Langsam | Grotesque march | Illusion (ignis fatuus); mockery; the grave |

|

| 10 Rast (Rest) | c / Mässig | Dirge/antique style/ground; “folk” style (voice, vs. 1, 3) | Freezing/burning; storm; his heart | Chromatic threads; cadential delaying |

| 11 Frühlingstraum (Dream of Spring) | A / Etwas bewegt/Schnell/Langsam | Musical box/ Viennoiserie/dance; dreams; grotesque; lullaby | Dreaming/awakening; birds; illusion; his heart | Motif x; dissonance; rocking octaves; major/minor |

| 12 Einsamkeit (Solitude) | b / Langsam | Dirge, “folk” style; storm (v. 3) | Alienation; gentle breeze/raging storms | Drone/slow footsteps; accompanied recit. |

| 13 Die Post (The Post) | E flat / Etwas geschwind | Horn calls (posthorn) |

| Moto perpetuo |

| 14 Der greise Kopf (The Old Man’s Head) | c / Etwas langsam | Antique style/ground; recit. (v. 2) | Illusion; frost/melting; death | Arpeggiation/ dim. sevenths |

| 15 Die Krähe (The Crow) | c / Etwas langsam | “Folk” style (v. 1, v. 3 ll. 1–2) | Faithfulness; the grave | Moto perpetuo; motif x; drama (v. 2, v. 3 ll. 3–4) |

| 16 Letzte Hoffnung (Last Hope) | E flat / Nicht zu geschwind | “Pizzicato”-style acc.; aria (v. 3, final line) | Wind/fall of a leaf; loss of hope | Arpeggiation/ dim. sevenths; semitonal motif; major/minor |

| 17 Im Dorfe (In the Village) | D / Etwas langsam | Hymn-like/antique style (final line) | Barking dogs; dreams; alienation | Tremolo figuration; 4-3 suspensions; Mozartian buffo style |

| 18 Der stürmische Morgen (The Stormy Morning) | d / Ziemlich geschwind, doch kräftig | March; theatricality/impulsiveness | Extreme weather; his heart | Arpeggiation/dim. sevenths; Neapolitan figure (v. 3 ll. 3–4) |

| 19 Täuschung (Illusion) | A / Etwas geschwind | Waltz/Viennoiserie /barcarolle | Illusion; ice; warm house/beloved soul | Ostinato; motif x; chromatic thread |

| 20 Der Wegweiser (The Sign Post) | g / Mässig | Dirge; antique style incl. “lament bass” and “wedge,” chant (v. 4) | Isolation; death | Trudging footsteps; chromatic thread; remote modulations; Neapolitan figure |

| 21 Das Wirtshaus (The Inn) | F / Sehr langsam | Hymn-like, slow march | Mortally wounded (v. 3, l. 4); the graveyard (“no room at the inn”) | Motif y; dactylic figure; major/minor incl. echo (v. 3, l. 4) |

| 22 Mut (Courage) | g / Ziemlich geschwind, kräftig | March/“folk dance” | Defiance; snow/wind; his heart; singing | Major/minor |

| 23 Die Nebensonnen (The False Suns) | A / Nicht zu langsam | Hymn-like, antique style/sarabande | Illusion; death wish | Major/minor |

| 24 Der Leiermann (The Hurdy-Gurdy Man) | a / Etwas langsam | “Folk” style; grotesque lullaby | Ice; dogs growling; traveler/musician; singing | Drone; ostinato |

Key

Acc. = accompaniment; Capitals for major, lower case for minor keys; aug. = augmented; dim. = diminished; l. = line, ll. = lines; v. = verse, vs. = verses. In “Mood/Musical topics,” “Konzertstück” indicates “brilliant” topic (virtuoso display); “Viennoiserie” denotes stylised Viennese dance figures. In “Motifs/Devices (music),” “chromatic thread” refers to the melodic line; “minor/major” (or vice versa) is indicated only in cases of parallel rather than relative keys; “motif x” refers to its original or inverted form; “Neapolitan figure” is the three- or four-note motif with flattened supertonic and leading-note turning around the tonic note or flattened sixth and augmented fourth turning around the dominant note.

We might pause to consider the characters peopling the narrative of Winterreise. The cycle is remarkable in its intensive focus on the protagonist, so that as listeners we may feel almost as if we experience something of the hardship he goes through on his journey. The landscape itself is a quasi-figure in the narrative, its features vividly delineated; its presence is constantly impressed on our senses, as it is on the protagonist’s. In a work founded on paired opposites, this strenuous winter’s journey represents a negative version of the Grand Tour (in the sense of a photographic negative). In place of the kind of Bildung whereby the traveler on the Grand Tour absorbs the culture of the wider world beyond his own experience, the landscape traversed by the protagonist in Winterreise makes his awareness turn inward onto his private feelings and experiences.3

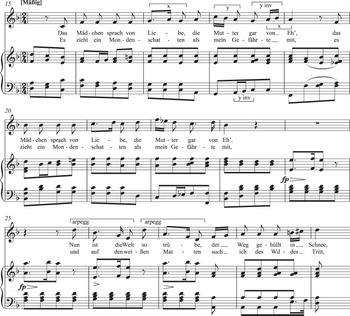

Other characters are figures from the past: the girl he longs for, her mother, and by implication her father, and the bridegroom who has replaced the protagonist in her affections. Those telling lines in “Gute Nacht,” “Das Mädchen sprach von Liebe, / Die Mutter gar von Eh’” (The girl spoke of love, / Her mother even of marriage), accompanied in the music by the turn to the relative major, have the power to remain imprinted on our minds. Indicative of a poetic thread running through the cycle, their import is full of hope, yet weighted with the danger of hope’s defeat. We might recognize their echo in “Die Post” at the start of Part II, when the sound of the posthorn raises hopes doomed to be betrayed. There too Schubert matches the opposing states by contrast of mode, in the parallel minor at the start of verse 2 where the traveler imagines that the post brings him no letter.4

While the girl and her family remain in his memory, the only other characters introduced during the course of the winter journey belong to the present rather than the past. First of these is the charcoal-burner in “Rast,” whose cramped home the wanderer enters for shelter. This character apparently exists only in absentia, or – if he is in residence – as a silent and unseen presence.5 The hurdy-gurdy man introduced in the final song (“Der Leiermann”) provokes speculation as to whether he represents an illusory or a real figure, and whether he functions literally as a traveling performer, or symbolically as a manifestation of Death. The Leiermann’s instrument suggests that he could represent an immigrant, set apart, like the protagonist. Susan Youens characterizes him as the protagonist’s Doppelgänger, a figure traditionally taken to be a premonition of death;6 this chimes with the duality in the constructions of both text and music throughout the cycle.

Connecting Threads

Arguably the most fundamental element linking text and music across the cycle is the intimation that the central figure is a musician. His appeal to the hurdy-gurdy man in the final three lines: “Soll ich mit dir geh’n? / Willst zu meinen Liedern / Deine Leier dreh’n?” (Shall I go with you? / Will you play your organ / To my songs?), can be taken as an indication of the protagonist’s calling rather than as metaphorical. Ian Bostridge has explored the traveler’s possible status as a music tutor in the girl’s household, while emphasizing Müller’s wish to avoid defining the character too precisely.7 Further indication is planted in “Mut!,” where the protagonist sings in defiance of the harsh conditions through which he journeys (and the depressive side of his own feelings): “Wenn mein Herz im Busen spricht, / Sing’ ich hell und munter” (When my heart speaks in my breast, / I sing loudly and gaily).

Another overarching element is the intensity with which the poet’s words portray the winter journey. The effects involved include extreme contrast and the evocation of startling images. Schubert’s setting creates a comparable intensity from across the spectrum at his disposal, including rhythmic profile, melodic shaping, motivic usage, harmony, texture, dynamics, relationship of voice and piano, and function of the piano accompaniment. All these, overlapping with topical reference, have the power to convey what words alone could not achieve, and to enhance or affirm what the words express. Additional details such as a specific contrapuntal device, or fragment of word-painting, can throw a spotlight on the text at individual moments.

Used in these ways, the music may add to the text Schubert’s personal reading of it, especially where the poet has created ambiguity or uncertainty rather than giving explicit definition to his ideas. In “Gute Nacht,” where the girl speaks of love and the mother “even of marriage,” with the move from the tonic minor to the relative major and then into its subdominant (see Example 10.1, mm. 15–23), Schubert allies the major mode with a diatonic chordal style of hymn-like serenity.8 This passage gains a touching hopefulness, expressed musically in the upwards reach of the melody and its sequentially related phrases. Notably absent from Schubert’s setting here is any trace of the bitterness associated with the betrayal that followed those promising signals from mother and daughter. Schubert’s music recaptures the moments of pure hope, untainted by hindsight.

Example 10.1 “Gute Nacht,” mm. 15–299

That excursus into the major throws into sharper relief the return to the tonic minor for the ensuing lines: “Nun ist die Welt so trübe, / Der Weg gehüllt in Schnee” (Now the world is so gloomy, / The road shrouded in snow). Here Schubert’s repeat of the paired lines is unable to move in key, remaining mired in the protagonist’s mood and the surrounding scene. In both text and music, “Gute Nacht” prepares us for many other instances where references to past happiness and comfort are contrasted with present hardship and misery. Schubert’s musical treatment gives love remembered a distinctive profile, as he does variously with the other main themes of Winterreise: loss, loneliness, death, and the winter journey itself. “Gute Nacht” introduces elements in both words and music that will be fundamental to the cycle as a whole.

Altogether a sense of the magnitude of the protagonist’s situation, and of the epic journey he undertakes, issues from the cycle in both text and music. The prolonging of harmonic progressions, as in “Rast,” at the matching ends of verses 2 and 4 in each paired set of verses, corresponds to the prolonged agony the wanderer carries with him. The extended diminished seventh chord heard at mm. 21–23 (see Example 10.2) and again at mm. 51–53, prefacing the approach to the cadence, is exploited for its disturbing properties. Its configuration, with notes crowded low in the piano accompaniment, together with the dissonant appoggiaturas in the voice (arrowed on Example 10.2), contributes to the harsh, grinding effect.

Example 10.2 “Rast,” mm. 20–31

Within each of these passages, the harmony is twice denied resolution before it is accomplished. Delay first sets in with the prolongation of the diminished seventh beyond normal expectations (as indicated on Example 10.2). An escape route is offered by the move to an augmented sixth (marked on the example in m. 23), with potential to trigger the cadential progression towards closure; but the music stalls, forming an interrupted rather than perfect cadence at m. 25. Only after a varied rerun, to a repeat of the last two lines of text, now prolonging the augmented sixth harmony (at mm. 26–29), does it finally resolve in a perfect cadence. In tandem with these proceedings, the vocal line soars beyond the confines of its contours earlier in the song. Schubert adds a tiny, affecting detail to the vocal part in the final version of the passage, inserting an anticipatory note at m. 55, before the upwards resolution of the appoggiatura on the word “regen” (stir).

These tactics lift the music of “Rast” above the level of the quasi-folk style with which Schubert delineated the humble scene in the vocal melody at the start. (That folk-like idiom forms another recurrent feature of the cycle, matching the equivalent element in Müller’s poetry). At the same time, and a measure of Schubert’s mastery, the disruptive surface created here rests on an underlying harmonic logic. Schubert’s dynamics add to the dramatic effect. He marks pianissimo for those uncertain approaches to the cadence, poised in each case on an enigmatic chord. Forte is marked for each of the postponed cadential resolutions, where in verse 2 the storm blows the traveler uncomfortably, even dangerously, along (a sensation he later tells us he welcomes), and where in the painful closing words of the final verse, his heart burns with the serpent that stirs within his breast.

At the opposite end of the spectrum from this drawn-out effect is the sudden stab of pain, as in “Wasserflut” towards the end of verse 1 in the repeated double-verse setting. After climbing precipitately through a tenth (m. 11), the vocal line seems to overshoot its target. What could have been the expected end of the phrase, on the E, is harmonized not with the tonic chord but with a dominant seventh of A minor transformed to a diminished seventh, against which the voice utters an anguished cry (m. 12) on the word “Weh” (woe). The melisma here, tracing the interval of a descending minor third over the sustained dissonant harmony, leaves the music open, responding to the sound of the word, which with its soft ending rather than hard consonant leaves the line of poetry similarly open-ended. (This plangent minor third was predicted at the start of the cycle in the opening three notes of the piano’s RH melody, echoed in the voice, filling in the interval stepwise in what constitutes the recurrent motif marked “y” in Example 10.3.) Schubert’s sensitivity to what Stephen Rodgers has referred to as the “sonic dimension of poetry” is a feature in evidence throughout D911.10

Example 10.3 “Gute Nacht,” mm. 1–11

In “Wasserflut,” with the ensuing repetition of the text, the vocal line plummets towards closure (mm. 13–14), a gesture that can be seen as reflecting the traveler’s volatile mood. At the end of the second half, the vocal line achieves closure on the e″ but approaches it differently, in a passage marked forte. With these strongly projected passages we can imagine the wanderer shouting into the snow-covered landscape as he conjures up first a vision of the snow melting away (verse 2), and finally his hot tears flowing with the brook past his beloved’s house (verse 4). Throughout the cycle Schubert uses the directional curve of his melodic lines (sometimes, as here, looping round as they climb up or plunge down) to dramatic effect. In “Der greise Kopf,” the piano introduction is launched with a precipitate ascent, followed by an abrupt descent tracing the outline of a diminished seventh, a harmony that resonates through the cycle. It featured as the first dissonant harmony at the opening of “Gute Nacht,” associated with the semitonal fall formed by the first two notes of motif y′ (see Example 10.3, m. 2). That two-note fragment creates the lamenting “sigh” figure noted by Youens; it too threads its way through the songs.

Unexpectedly, in “Der greise Kopf,” the voice takes up the piano’s sweeping opening gesture, peaking a third lower. This unlocks the theatrical character of the music that follows. Its expressive zone, drawing on the language of recitative, matches the drama enacted in the words. The traveler thinks jubilantly that he has grown old suddenly, and is horrified to realize that the white sheen spread by the frost over his hair has melted away. This strange reversal of the wish to stay young, resisting the encroachment of old age, is destabilizing and yet understandable in the context of his longing for death. The build up to the crux at the words “Wie weit noch bis zur Bahre!” (How long still to the grave!) is couched in the ominous chromatic language with which Schubert portrayed elements of plot and character in his early dramatic Lieder.11 More ominous still is the octave/unison texture that follows in piano and voice for that crucial line where the traveler contemplates the grave.

Allied to the intensity felt in both text and music at a single moment is the prevailing sense of obsessiveness and circularity characterizing the protagonist’s pronouncements as he reflects on his condition. Schubert’s setting produces an equivalent to this poetic trope. The devices of ostinato and moto perpetuo, hallowed by centuries of use and finding new life in the nineteenth-century Lied, are exploited to this purpose throughout Winterreise (see Table 10.1 for songs employing the techniques). Schubert draws on them in a myriad of ways. (Examples discussed under the heading of “Topical Genres” below include “Gute Nacht” and “Wasserflut”.)

Besides its psychological implications, circularity serves in Winterreise to reinforce the work’s cyclic status, linking individual songs more than casually within the whole structure. Schubert’s compositional choices enable the music to support this element in the poetry, as well as building a strong overall structure in itself. At its most readily perceptible, this process operates where melodic and rhythmic figures heard at the end of one song are picked up at the beginning of the next. As Bostridge puts it, these connections create “an elective affinity between certain songs (the way the impetuous triplets of “Erstarrung” segue into the rustling triplets of “Der Lindenbaum” … [and] the repetitive … dotted figure of the last verse of “Lindenbaum” is transmuted into the opening of “Wasserflut”).”12

Schubert’s Fingerprints

By the time of writing Winterreise, Schubert had the elements of his style well-honed and readily at his disposal. Traces of intertextuality are threaded through in tandem with these Schubertian “fingerprints.” They range from the innermost connections within the cycle through analogies with others of his Lieder; further across his oeuvre to parallels with his instrumental and sacred vocal works; and also, beyond all those, to echoes of other composers. Mozart is in the background to Schubert’s music throughout his oeuvre. Mozartian echoes in Winterreise include the repeated-note patter (on the note D) in “Im Dorfe” at mm. 19–23, with the playful vocal interjections against it, and the bass in parallel with the voice, which sounds like a passage from the Act II finale of Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro.13 The choice of key for a song also sets up associations. By Schubert’s time, the key of “Gute Nacht,” D minor, carried with it an aura of tragedy, horror, and death from its usage in opera and requiem: Mozart again comes to mind.

Beginnings and Endings

Schubert invests the opening and closing music of Winterreise with special significance. Songs 1–5 and 20–24 provide in many respects a microcosm of the cycle. The two bookends (songs 1 and 24) resonate with each other, possessing musical figures rich with import. As Youens put it, the closing measures of “Letzte Hoffnung” present a “gesture with a history that begins in the first measures of the cycle.”14 This certainly applies to the final song. The drone bass at the start of “Gute Nacht,” with its topical reference to rustic culture, evokes the traveler’s footsteps as he trudges across the wintry landscape. In retrospect it can be seen as prophesying the hurdy-gurdy man’s music at the end of the cycle. (As commentators have noted, Schubert plants references to it in the intervening songs.)15 Heard in the opening measures of “Gute Nacht,” this trudging drone has an inexorable quality reflecting the traveler’s intense compulsion to embark on the journey. In one possible reading of the final song, it may indicate the transformation of his journey into a life of eternal wandering.

Within the casing formed by the songs at start and finish, each individual song contains a sharply drawn vignette, in some cases focusing more steadily on a particular scene, in others more hectically dramatic, and typically framed by both piano introduction and postlude. As Youens notes, only one song, “Rückblick,” lacks a postlude.16 The purposes to which these textless opening and closing passages lend themselves are rich with possibilities in relation to structure and expression. When the piano postlude in “Gute Nacht” echoes the voice’s closing phrases, where the traveler wants his beloved to know he thought of her as he departed (“an dich hab’ ich gedacht”), those echoes in the piano are placed in an inner voice within the trudging chords, as if to indicate the persistence of her presence deep in his mind. They convey his ambivalence: while he knows he must leave, he nurtures an abiding reluctance to part from her.

These psychological implications resurface later, for instance in “Rückblick,” where at the end he wants to stand still outside her house (hence, as Youens observes, the lack of a piano postlude, since the music too must stand still).17 Here the crux comes at the end (as in “Erlkönig,” D328): the ensuing silence, shorn of a postlude, is telling. Those last wishful thoughts the protagonist expresses contain the seeds of what would now be called stalking; the urge remains in his imagination, where it contributes to the burden of emotional pressure he carries. The words and music at the end of “Rückblick” tell us that he has not yet managed to separate from her psychologically. When he does so, in Part II (which, as commentators have noted, remains free of direct reference to the beloved after the first song, “Die Post”), it is a sign that his obsession with her has been replaced by an equally strong fixation on a desire for death. The words of Death personified in Schubert’s “Der Tod und das Mädchen” (D531) come to mind, when he reassures the maiden that he comes to comfort and not to punish her. The traveler in Part II of Winterreise, contemplating death, pleads that he is not deserving of punishment: “Habe ja doch nichts begangen, / Dass ich Menschen sollte scheu’n” (I’ve committed no crime / That I should hide from other men).18 The songs towards the close, bringing to the fore intimations planted earlier, suggest that his hopes are increasingly fixed on the release from suffering offered by eternal rest.

Motivic Networking

From the start, with “Gute Nacht,” Schubert’s characteristic fashioning of melodic lines from a few intervallic cells helps to give the opening measures an intensity that not only sets up the mood of the whole cycle, but also introduces significant motivic elements. The motifs packed into those measures suggest in miniature a kinship with the principle of “developing variation” that has been attributed to Brahms.19 The falling fourths (numbered on Example 10.3) already contained in the continuation of motif y and its variant form y′, are detached in mm. 4–5, then heard in diminution and filled-in at m. 52. Schubert’s song melodies, far from spreading luxuriantly, tend to make economical use of tiny seeds that grow into a unified yet variegated line.

The genre of song cycle lends itself to the creation of a network of motivic material linking individual songs and responding to the intertextuality within the poetic sequence.20 While a motif may not necessarily be associated with the same or similar poetic ideas on its recurrence, there may be a shared poetic context among its appearances. A particularly prominent Schubertian fingerprint heard at the beginning of Winterreise is the palindromic neighbor-note motif (marked “x” on Example 10.1) which, together with its inverted form, recurs in voice and piano throughout “Gute Nacht.” The motif is found among songs from earlier in Schubert’s life. The obsessive quality that infuses his remarkable setting of “Gretchen am Spinnrade” (D118; 1814) derives partly from its use in both the spinning piano accompaniment and the vocal line, in its original (here with lower neighbor-note) as well as its inverted form, throughout. Among a plethora of examples in the instrumental works, the late string quartets show a similarly obsessive use of this motif. In Winterreise, its occurrence in a variety of contexts mirrors the protagonist’s obsessive musings at different stages of his journey (see Table 10.1, shown as “motif x”).

Major–Minor Juxtapositions

The most familiar major–minor effect, the echo, where a passage in the major is repeated in the parallel minor (or vice versa), has the power to transform mood as well as mode. This is but one of an array of devices along the spectrum Schubert explored with regard to modal mixture. In his Lieder, he used the major–minor echo with sensitivity to the implications of a variety of textual prompts.21 Some of its most powerful manifestations occur with the reverse Picardy third, a Schubertian specialty (inherited by Brahms) whereby after apparently signaling closure, the major is followed by a minor resolution, as in two of D911’s “dream songs”: “Gute Nacht” and “Frühlingstraum,” conveying the return from the dream-world (or thoughts of it) to reality.

During the course of a song, Schubert’s injection of major into minor-key surroundings ranges from a brief flash of color (as occurs towards the end of “Die Wetterfahne”) to an extended section, as in verse 7 of “Gute Nacht.” Its adaptability as an emotional signifier ranges from the bitter resentment expressed in the final lines of “Die Wetterfahne” (“Was fragen sie nach meinen Schmerzen? / Ihr Kind ist eine reiche Braut.” [Why should they care about my grief? / Their child is a rich bride.]) to the tenderness with which the music in “Gute Nacht” suggests that the traveler imagines her sleeping and dreaming.

Variations and Transformations

In Schubert’s songs, as well as his instrumental works, variation principles at their most sophisticated reflect his vision of a range of possibilities operating at different levels of the music.22 Among the song-structures Schubert builds (exercising some flexibility in relation to Müller’s verse structures), the modified strophic form (as in “Gute Nacht”) and bar form (AA′B, as in “Irrlicht”) can accommodate variations in voice and piano responding to nuances, or more extended changes of mood, in the text. This applies also to more freely built song forms possessing an element of refrain, such as those in “Die Wetterfahne” and “Der Lindenbaum,” with their varied treatment of the recurring passages.

Among Schubert’s characteristic ploys is the playfulness he brings to varying his material. In Winterreise, this is manifested not in the lighter vein of such works as the “Trout” Quintet (D667), but in cruel travesty. The trickery that characterizes the ignis fatuus in “Irrlicht” is established at the start in the piano introduction with its consequent at mm. 3–4 mocking the falling fourths of mm. 1–2. That falling fourth motif is subjected to further mockery in the voice’s entry, first with the dotted rhythm developed into a kind of anti-march figure at m. 5, filtering into a grotesquely leaping figure in m. 6; then on its next appearance turned into a misshapen diminished fourth (m. 9). These proceedings constitute a distortion of Schubert’s customary practice of echoing the piano’s introductory melody in variant form in the voice’s first entry (as in “Gute Nacht,” to the enrichment of the motivic network). In “Irrlicht,” what follows in m. 11 distorts the arpeggio figure from mm. 25–26 of “Gute Nacht.” It is as if in his febrile state the traveler takes on something of the character of the Irrlicht as he describes its effect on him. In the verses that follow, Schubert develops the bar form, featuring a variant A section for verse 2; the B section for verse 3 responds with a new, profound seriousness to the text (its crux in the final lines introducing the first reference to the grave in the cycle). The piano postlude allows the Irrlicht to have the last word.

Like the musical motifs, recurrent motifs in the poetic text appear in different contexts. The memory of the “green meadow” through which the protagonist walked with his sweetheart, recalled in “Erstarrung,” verse 1, triggers a move to the relative major (E♭) at mm. 20–23. His (fruitless) wish in verse 3 to recapture it (“wo find ich grünes Gras?”) again triggers a passage in a related major key, this time the submediant (A♭). “Frühlingstraum” allows him the idyllic vision of green meadows in his dreams, set in a brightly configured A major. The color green appears transformed in Part II. In “Das Wirtshaus,” instead of the association with happier memories of lush meadows, he sees green wreaths (“grüne Totenkränze”) as a sign inviting him into the graveyard: the setting moves at this point from F major into G minor, as it did at the beginning of the song when his steps turned towards the graveyard.

A particular Schubertian speciality is the transformation of lyrical into dramatic and violent expression, found among the late instrumental works at its most extreme in the slow movement of the A Major Sonata (D959).23 In Winterreise, this aspect of the music, like Schubert’s major–minor juxtapositions, is harnessed to Müller’s penchant for binary constructions. In verse 1 of “Frühlingstraum,” the idealized dream scene painted by the poet is matched by the artificiality of the Viennese waltz, fashioned in music-box style, its only chromatic touch a fleeting neighbor-note decoration. Birds reappear grotesquely transformed, when the twittering creatures incorporated gracefully into the opening section’s dance topic find their alter egos in the stormy B section that follows, with the harsh cockcrow, and the ravens shrieking from the roof, marking the abrupt awakening from the dream. Here the elegant neighbor-note motif associated with major-key sweetness in the opening section is embedded within the language of dissonance and distortion, as the music rises hectically in pitch and volume.24

Topical Genres: March, Dance, and Lullaby

Schubert’s contribution to the genres of march and waltz belongs largely to the sociable, popular side of his oeuvre.25 Their infiltration into the late chamber and piano works involves the expression of darker moods. In Winterreise, too, they take on a sinister character. The pressure on the protagonist to pursue his journey, reinforced musically by the recurrent march topic initiated in “Gute Nacht,” and poetically by the winter imagery, has echoes in the forced marches made throughout history. Also recurrent is the dirge or funeral march topic, linked with oppressive ostinato patterns and antique style, and evoked in a variety of contexts, ranging from “Wasserflut” to “Der Wegweiser” (see Table 10.1). The Viennese waltz topic characterizing the A sections of “Frühlingstraum,” with its air of unreality, extends to grotesque effect in “Täuschung,” where it persists manically throughout the song, prefiguring the glittering ball scene in the same key in Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, and confirming the sentiment that concludes Müller’s text: “Nur Täuschung ist für mich Gewinn!” (Only illusion lets me win!).

Besides the handful of songs Schubert produced under the title of “Wiegenlied” (Cradle Song) or “Schlaflied” (Lullaby), this topic is discernible in numerous others of his Lieder. While the final song of Winterreise (“Der Leiermann”) is less obviously a lullaby than that of Die schöne Müllerin (“Des Baches Wiegenlied,” D795/20), it possesses the hypnotic qualities associated with that genre, with its steady harmonic grounding and the repetitive looping figures in the melodic line. But in its angularity and eschewal of comfort, “Der Leiermann” forms a grotesque version of lullaby.26 In more muted form, lullaby is threaded through the cycle. “Wasserflut” mixes its piano LH topic (its dotted-rhythm dirge conveying an aura of funeral march, albeit in triple time) with a distinctly different RH topic, whose hypnotic rocking arpeggio figures signal lullaby, demonstrating the power of music to express two or more contrasting items simultaneously. Bostridge’s argument for non-assimilation of the differing rhythmic elements in the piano LH and RH receives support from the presence of these two topics.27

Schubert has taken his cue for the more restful lullaby topic in “Wasserflut” and in the final verse of its predecessor, “Der Lindenbaum,” from the protagonist’s expressions of yearning for peace and rest (“Ruh”). These form a poetic motif throughout the cycle. In the ABCABC form of “Frühlingstraum,” the C section exhibits lullaby properties as the protagonist reflects on his dreams with a profound sense of loss: “Wann halt’ ich mein Liebchen im Arm?” (When will I hold my love in my arms?). The rocking octaves in the piano accompaniment soothe rather than disturb. Here, as elsewhere, the piano is a sympathetic responder to the protagonist’s mood.

Antique Style

Contributing to the profundity of Winterreise is Schubert’s frequent turning toward antique models of musical material, a phenomenon rife also in the instrumental music of his last decade. In D911, such references appear in a variety of shapes and contexts: some instances are clearly audible on the surface, while others are embedded more subliminally. Their use contributes to the dual-facing impression that pervades Winterreise. Both Müller and Schubert show allegiance to inherited forms of expression, as well as an experimental modernity. The ancient formulae come loaded with meaning. Most loaded of all is the chromatic fourth, the lament bass familiar from Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, and widely used in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century instrumental as well as vocal genres. The chromatically filled-in fourth, or fragments of it, threaded through the musical texture in D911 (see Table 10.1 and Example 10.4) is a constant reminder of the protagonist’s incurable sense of loss. In Part II its traditional association with death emerges more strongly.

Example 10.4 “Der Wegweiser,” mm. 65–83

Linked to antique style is the religioso topic present from the start of the cycle with the turn to F major (and its subdominant B♭) in verse 1 of “Gute Nacht.” The hymn-like veneer added to a variant of the trudging motif in the accompaniment there comes to the surface (like much else) towards the end of the cycle. Graham Johnson sees the key of F major, inflected with subdominant color, that Schubert chose for “Das Wirtshaus” as an anomaly, illogically poised between the G minor songs on either side.28 But we could interpret it as a reference to the original manifestation of that topic in “Gute Nacht,” in those same keys (F and B♭). Seen in this light, in “Das Wirtshaus,” they serve simultaneously as a reminder of the hope of lasting love that was lost at the origin of the journey, and a signal of the hope for death that has replaced it.

Commentators have not failed to notice parallels in the poetic text of “Das Wirtshaus” to the Nativity story, and also in that text, as in the winter journey altogether, to the Passion story. Schubert’s music in “Das Wirtshaus” endows the funereal scene, and the protagonist’s response to it, with dignity, reinforcing the idea conveyed in the words of the preceding song, “Der Wegweiser,” of his purity of character. Whatever the protagonist’s theological stance may be, reference to antique models, and hymn-like style, confer a seemingly genuine aura of the sacred on the music of Winterreise. It gains added gravitas when infused with counterpoint. Among Schubert’s references to antique style, and a personal fingerprint shared across the range of genres he cultivated, is the 4–3 suspension, first heard in “Gute Nacht” together with the hymn-like topic at mm. 16–17 (Example 10.1). This ancient contrapuntal formation becomes a pervasive element thereafter.

Schubert’s penchant for canonic technique contributes to the seriousness evoked in particularly portentous passages of the text. The archaic references in “Der Wegweiser” present the most intense example, ranging from the canonic reflections of the funereal opening phrases between voice and piano, threaded through the minor-key A sections (the brief memory of the traveler’s blameless past in the central B section is free of such artifice), to the building of tension in the final measures, with their combination of chromatic fourth (lament figure) and wedge (chromatic contrary motion), as marked on Example 10.4. Both those figures are weighted with a history of fugal counterpoint. Their inexorable move towards collapse, followed by the unmistakable quotation from “Der Tod und das Mädchen” (the dactylic repeated-note figure associated with death), forms one of the most ominous endings in Winterreise.

Epilogue

Schubert’s scene-painting in Winterreise has a vividness fueled by his evident belief in music’s power to bring words to life – a belief shared by Müller. In joining his art to Müller’s, Schubert conjured up the swinging weathervane (sign of the girl’s faithlessness) in “Die Wetterfahne,” the descent to the rocky depths in “Irrlicht,” the shrieking ravens in “Frühlingstraum,” the falling leaves in “Letzte Hoffnung,” the dogs barking in “Im Dorfe,” the hurdy-gurdy playing in “Der Leiermann,” and much else. Beyond this, Schubert’s settings convey his profound feeling for the central character. Because Schubert was deeply moved by the protagonist’s sufferings, his music for Winterreise, working with the poetry, has the power to move us.

Noticeable in Müller’s text is the evidence of the human urge to leave some trace of a person and a life, expressed in the traveler’s memories of carving names in happier times into tree bark, and his wish, as he makes his winter journey, to etch them on the icy surface of the water. Schubert, writing his name as a composer on the surface of the poetry, allows us access to the depths that lie beneath.