Standard narratives of Singapore's colonial history often write of the city-state's success story in light of Raffles’ predictions (and contributions to) its rise as a colonial emporium and its significance as a port of call for traders, travellers and officials in the age of high imperialism. But what did it mean for Singapore to be regarded as a great colonial emporium in the East? In what ways was Singapore represented in the British imperial imagination? Singapore, by the early 1900s, was one of the world's busiest ports and a significant hub for shipping within the British Empire. This article examines Singapore from the vantage point of imperial maritime connections, particularly when it was host to imperial tours, including royal visitors and the Royal Navy. Arguably, Singapore's inclusion as a port of call in two important voyages of empire, that of the Royal Tour (with a fleet led by the HMS Ophir) in 1901 and in the 1923–4 Cruise of the Special Service Squadron, also known as the ‘Empire Cruise’ (led by the HMS Hood), brings such maritime connections to the fore.

Both cruises stopped at Singapore as one of the key ports of call in Asian waters. Tours of empire were not everyday events; but rather were heralded as exceptional demonstrations of British imperial reach and also as an illustration of the connectivity of the British Empire via the seas. Each tour held a slightly different purpose and composition in terms of ships and travellers, but was nonetheless regarded as significant in presenting and projecting British power overseas. These tours were expressions of British propaganda and pageantry in the early 1900s and can be examined as a means to understand Singapore's place within the Empire and in the broader imperial imagination.

The voyages reaffirmed Singapore's place as a hub within a British world (and maritime) network. This study of imperial tours also demonstrates a connection between past and present; the idea of Singapore as a hub, and as a ‘success story against the odds’ is expressed in these tours and is also very much present in present-day narratives of Singapore's journey to nationhood. Given the increased interest in understanding and contextualising Singapore's colonial history, this study presents new possibilities for thinking about the city-state's maritime connectivity in the ‘age of empire’ and how its colonial port status was celebrated in the early twentieth century.

Singapore as a colonial port city

After its beginnings as an EIC trading post and a subject of Anglo–Dutch contestation, Singapore by the mid-1800s emerged as one of the great colonial Asian ports of the British Empire.Footnote 1 As centre for the intra-Asian trade as well as the lucrative East–West trade routes, it has been described as holding a ‘Janus-faced’ role as a regional entrepôt and imperial outpost.Footnote 2 By the time of its change of status to a crown colony, Singapore — as the primary port in the Straits Settlements — boasted a flourishing population, a sizeable business community, a key role in steam shipping (and as a coaling station), and the main trading centre for goods from the Malay Peninsula. Increasingly, Singapore also took on significance in relation to the defence of British imperial interests in the East. Like many other important colonial ports such as Kolkata (Calcutta), Colombo and Hong Kong it also had a commercial infrastructure that featured not only prominent and influential trading communities (with far reaching networks) but also the presence of major financial institutions; this allowed a seamless conduct of business for the agency houses and merchants based in Asia. Its community was similar to that of other colonial ports, such as Calcutta, Colombo and Hong Kong, where transient cheap labour sustained the functioning of the port and city. Governance was handled by a small ‘settler’ community of European elites and much of the business of the colony was orchestrated by Asian (quite often Anglophone) elites, while a number of trading communities moved goods not only in the lucrative East–West route but intra-regionally.

As Mark Frost and Yu-Mei Balasingamchow observed of Singapore in the late nineteenth century in Singapore: A Biography:

globalisation had arrived and it came with a series of clichés by which European writers tried to capture its impact. Just as today, speechwriters in Singapore seem fixated by the idea of their island as a ‘hub; so colonial writers over a century ago displayed a parallel talent for literary triteness. By the 1800s, Singapore was the ‘Charing Cross of the East’, the ‘Clapham Junction of the East’, the ‘Liverpool of the East’ …

You only had to take some major port or transport junction in Victorian Britain, tack on the words ‘of the East’ — and there you had a description of late 19th-century Singapore.Footnote 3

So, what we have then is a fascination with wanting to not merely describe Singapore as an important seaport or maritime junction, but to see it as somehow mirroring the imperial centre in terms of development and trade characteristics. While we can say this trend of dubbing Singapore the ‘someplace — of the East’ devalues such terms, at the same time, it reinforces the fact that the port city was viewed in a manner that was shaped by empire; with a consciousness of its place with an imperial framework. Undoubtedly, place-making was an integral part of colonialism; the colonial encounter was not only about power and economics but culture, ideology and shaping the landscape.Footnote 4 Also, the dubbing of Singapore as the ‘Liverpool of the East’ was not so much for the benefit of a local audience, who may well have not travelled beyond Asian waters, but for a British (or Western) audience. Liverpool was of course the so-called ‘Second City of Empire’, and such a connection reaffirmed Singapore's importance in relative terms.Footnote 5 In 1858, the catchphrase appeared in parliamentary debates over Singapore's status (and that of the Straits Settlements vis-à-vis India) and the Encyclopedia Britannica of 1860's entry on Singapore likewise describes it as the ‘Liverpool of the East’ by virtue of its status as a trading emporium.Footnote 6 Singapore did hold an important place in the British maritime sphere; nearly all ships travelling the East–West route would pass or call into Singapore, if only briefly. Gregg and Gillian Huff note that ‘all shipping in the British Empire's (and the world's) main East–West trade routinely passed within a few miles of Singapore. Singapore therefore set a precedent for all empire shipping.’Footnote 7

Singapore's importance as a colonial port city was reinforced via technologies such as the steamship, the telegraph, rail, and the opening of the Suez Canal. In her exploration of the opening of the Canal, Valeska Huber explains that the advent of more regular steam services led to changing perceptions of not only travel, time and space, but also of places and ports of call; for Western travellers the exotic was no longer as distant or perhaps as different as it once had been.Footnote 8 And Frost and Balasingamchow echo this observation with a reflection that such technological transformations also irrevocably changed the social, political and even intellectual milieu of port city life. ‘For new European arrivals, it was no longer necessary to invest time in adapting to a life in “exile” and especially in trying to understand local languages and customs, since home was now only a fortnight away.’Footnote 9 With this came a new influx of travellers to Singapore too — tourists wanting to explore the port, expatriates travelling for work, and British officials posted to the colony as part of their imperial careering.Footnote 10 Early Singapore was the subject of many travelogues (and later travel guides) and some tropes such as the ‘idyllic kampung’, the industrious Chinese or romanticised views of plantations appear in many accounts in the nineteenth and into the early twentieth century.Footnote 11 In this article, however, the focus is not on the intrepid traveller's gaze, but on the narratives which emerged as a result of imperial tours and official visits; some tropes overlap while others are clearly a reflection of a preoccupation with the grandeur of the official cruises and of presenting Singapore as a product of empire. It is to the idea of imperial propaganda that this article now turns.

Promoting the empire and the monarchy

While discussing propaganda and empire, this article derives inspiration from the works of John MacKenzie, a pioneer in his scholarship on imperial culture in the British Empire. In Propaganda and Empire Mackenzie discusses a new intellectual and social milieu emerging in the late 1800s. He describes it as an ‘ideological cluster that formed out of the intellectual, national, and world-wide conditions of the later Victorian era, which came to infuse British life’.Footnote 12 This ‘ideology of empire’ (to give it a name) according to Mackenzie consisted of elements such as a reverence for national heroes, a devotion to royalty, renewed militarism and also ideas relating to Social Darwinism. These combined to create a ‘new type of patriotism’ which drew special significance and vigour from Britain's imperial cause. As an example of scholarship emerging as a fresh appraisal of the culture of empire, Robert Aldrich and Cindy McCreery in Crowns and Colonies explain that royal or imperial tours placed the links between the colonial empires and the institution of the monarchy on public display.Footnote 13 It is conceivable then, to consider cruises of the empire as extensions of this new patriotism; such tours provided avenues for an expression of British imperial responsibilities and were framed in terms of imperial pride and concern for their subject peoples. For instance, the tour of the HMS Galatea to the Cape in 1867 was exemplary of the royal tour; here Prince Alfred, the second son of Victoria, travelled not as a royal passenger but as the captain of the Galatea.Footnote 14 This tour bridged both naval and royal responsibilities and was used and commemorated in turns, as a chance for local hosts to demonstrate loyalty (Britishness) or for the local populace to demonstrate their difference from the colonial authorities.Footnote 15

In a study on the monarchy and empire titled Royal Tourists, Charles Reed contends that the royal tour had particular significance as an event where meanings of empire (and the monarchy) were made and remade by those involved in these tours.Footnote 16 And likewise, for those places visited as part of any royal tour, the visible affirmation of imperial connections and of how a colonial city and its subjects represented itself to these important visitors was also insightful.Footnote 17 Such tours had a role to play in the late Victorian period and into the Edwardian years as they served an important role in imperial propaganda. Mackenzie's Propaganda and Empire traces such impulses and links them to popular culture. He notes the way that symbols of empire made their way into homes in the metropole via ephemera and advertising. Postcards and later film clips captured images from the tours of empire; the places and people of empire formed one aspect of this popular culture manifestation of empire. He reflects that ‘imperialism made spectacular theatre, with the monarchy its gorgeously opulent centerpiece’.Footnote 18 While Queen Victoria often resisted such displays (apart from her crowning as Empress of India), by the 1880s the role of the royal family in empire was increasingly ceremonial and visible. And once in a port, the treatment of the royal family often demonstrated the desire to fuel popular support for the British Empire.

Later manifestations of imperial propaganda included the posters and films produced and distributed by the Empire Marketing Board. These included not only images of empire builders and places of the empire but gave Britons a taste of its far reaches. For instance, the empire and its maritime linkages is most evocatively rendered through the poster series of the Empire Marketing Board's campaigns of the 1920s and 1930s (see fig. 1). In these posters maritime connections feature as an integral component of the British imperial system and its ideological basis. Britain's Birthright, a 1924 film depicting the Empire Cruise — and once again exemplifying the idea of imperial propaganda — will be discussed later in this article.

Figure 1. ‘Highways of Empire’ poster in the booklet ‘A Year's Progress’ (1927) Empire Marketing Board. CO/323/982/3. Reproduced by permission of the National Archives UK.

The Royal Tour of 1901 on the HMS Ophir

In 1901, the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York, the future King George V and Queen Mary, embarked on a worldwide tour of the empire. The tour was designed by Joseph Chamberlain and the Duke himself and it was to be the most ambitious tour of empire to date. The tour was intended to inaugurate the new Australian Parliament and also to convey Britain's appreciation for the support rendered in aid of the imperial war that was ongoing (or rather, dragging on with little resolution) in South Africa.Footnote 19 As part of their responsibilities as royal tourists the Duke and Duchess took part in a number of events including durbars, troop inspections and were entertained by indigenous peoples.Footnote 20 This tour had a particular significance for three reasons; it was at the dawn of a new imperial century, the empire was still expanding (it grew further in the wake of the First World War), and the cruise followed shortly after the death of Victoria (in fact, the tour was framed as very important as a way to fulfilling the late queen's wishes). The royal couple spent months at sea, travelling on the HMS Ophir and accompanied by a number of vessels. The fleet visited many key territories including Australia, New Zealand, Mauritius, South Africa, Canada, stopping also in Aden, Ceylon and Singapore.Footnote 21 The tour would not only celebrate but consolidate imperial bonds. It was described as a royal odyssey which ‘practically girdled the globe’.Footnote 22 Naturally, a tour envisaged on this scale and duration was followed with great public interest both at home (in the metropole) and throughout the empire.Footnote 23 There were chroniclers onboard the ship, in addition to the local press present at each port. Seasoned journalist and former servant of the British Raj, Sir Donald Mackenzie Wallace, travelled as part of this voyage and published the official account of the voyage on behalf of the royal couple.Footnote 24 It is to his account of the tour that we now turn.

Wallace is an interesting raconteur as he represents the ‘official’ or sanctioned account of the royal party; his was a privileged view as a friend to the prince. It is through his eyes that readers have a glimpse of shipboard life and an introduction to Singapore. The rigours of life at sea and of the warm climate were a common refrain in his work. For instance, after leaving Colombo most passengers opted to sleep on the deck owing to the heat, but found their plans disrupted due to torrential rain.Footnote 25 Wallace expressed some frustrations with the weather, ‘We have all had enough of the tropics, but we must possess our souls in patience, for we have still a long run almost parallel with the Equator, to the Straits of Malacca, and we shall not get south of the line till after we have passed Singapore.’Footnote 26 The approach to Singapore was regarded with some excitement, but mixed reactions. Wallace recorded on 19 April, ‘We are now entering the Straits of Malacca, and for the next twenty-four hours our course lies along the Sumatra coast. It is not nearly so picturesque as we expected, for the mountains soon retreat from the shore and run down the other side of the island.’Footnote 27 Wallace observed that it was squally all day and then there was a brilliant thunderstorm that night, preventing anyone from sleeping on deck.Footnote 28 Singapore was designated as a key port of call because it was there that the fleet would need to coal.Footnote 29 In recognition that the day would be busy with coaling, all on board were informed that the Commodore had decided that the Saturday would be considered Sunday, with a muster of all hands and a morning service.Footnote 30

At first sight Singapore is described as ‘embedded in evergreens’ and soon the fleet (and the HMS Ophir) was likewise embedded at the coaling station. The Royal Highnesses were transferred to Johnston's Pier on a steam-launch where officials and the ‘leading inhabitants’ were ready to receive them. The royal couple were then driven by open carriage with a mounted escort to Government House.Footnote 31 Wallace commented on the hot and steamy weather but found favourable words for the good views from Government House (today's Istana), including the beautiful park of green lawns intersected by red roads and magnificent views of the park, the surrounding ‘jungly’ country and the harbour.Footnote 32 Fittingly, the royal couple arrived at the Borneo dock, this being a reference to a frontier of empire but still within the reach of British imperial influence.

The arrival of the HMS Ophir was heralded by the Singapore Free Press as ‘the greatest Imperial event since the founding of these [Straits] Settlements’.Footnote 33 Frost and Balasingamchow argue that this event was evidence of the rise of the Asian (Anglophone) elites within the port city of Singapore. In this instance, they focus on Sinhalese jeweller and philanthropist de Silva who was tasked with organising displays and overseeing the crafting of lavish gifts for the royal couple (De Silva's expertise in jewellery meant he secured several commissions to make pieces for elites and Malay Royalty).Footnote 34 The handiwork of his master craftsmen was featured in the metropolitan presses of the time and arguably established his status as a local (yet Anglophone) elite. Certainly, local elites were brought to the fore in this reception of the monarchy and imperial bonds, but the power relations at play and the ceremonies also pointed to imperial notions of British rule and dominance.

If this tour was about the monarchy being made accessible to the empire and to colonial subjects, it was also about the way in which local elites (and rulers) were often forced into submission, into rituals recognising British power. For instance, durbar-like ceremonies were adopted beyond the British Raj and local rulers were often expected to take part.Footnote 35 And according to some press accounts, a durbar was also held in Singapore during the Duke and Duchess’ visit; here traditions from the Raj were transferred to Singapore as part of a larger ‘imperial’ experience.Footnote 36 The royal procession paraded through the town, and was cheered and applauded. Wallace described this as unplanned, a spontaneous gathering; for the reader is meant to perhaps see this as evidence of the goodwill the royals (and empire) engendered in the colony. The royal couple were treated to opulent fanfare such as night-time processions, children's fetes, polo matches and dinners. According to Wallace, long-time residents declared that this eclipsed anything ever seen in Singapore before.Footnote 37 What we should bear in mind again, is the notion of the royal tourist and the way that local populaces were often brought into the spectacle and drama of the pageantry of empire. This also led to issues of protocol and social expectations; one anecdote (recounted after the visit) speaks of collective concern and rather ingenious improvisations when it was discovered, to much chagrin, that guests lacked sufficient gloves to greet the royal couple in a proper manner.Footnote 38

A feature of the visit was the local Malay rulers and chiefs (and retinue) from the Federated Malay States arriving to call on the royal couple. This is significant as British control in Malaya — realised through the Federation of the Protected States in 1896 — had grown and continued to expand.Footnote 39 A portrait of Malay rulers is featured in Wallace's account of the royal tour. The special audiences of the Malay elites and rulers corresponds to Frost and Balasingamchow's contention that the indigenous, local elites were given a high profile during this visit. At the same time, it also points to what other scholars (such as Reed in Royal Tourists) describe as elites being co-opted, and sometimes pressured, to take part in audiences with the royal visitors.Footnote 40 In Wallace's account we also have the imperial ‘official perspective’ on local elites, who were co-opted into the British system but still regarded with some fascination (it is timely to consider David Cannadine's Ornamentalism and his ideas on the ‘cult of monarchy’ and imperial social hierarchies in this regard).Footnote 41 Wallace detailed the audiences of the local community with their Royal Highnesses and observed that the array of British subjects were, in his words, a motley assortment of all nationalities and faiths.Footnote 42 He pointed out that their names were as varied as their nationalities and that some were ‘very un-English’, citing Indian, Chetty, and Arab names among others. After seeing them all presented to their Royal Highnesses, Wallace reflected: ‘we feel proud to think they all glory in British Nationality, or at least British protection and British justice’.Footnote 43 Handel's chorus ‘From the East to the West’ was sung by the choir as a high point of the event; reaffirming once again the empire as a unifying force.

Wallace described the audience of the Malay rulers as a picturesque gathering, with groups kept carefully apart (here, Wallace may have wished to impress on his reader his awareness of unrest between different Malay states or even moreso to perpetuate stereotypes of the rivalries and conflicts in the Malay Peninsula that British rule kept in check). Wallace described these groups as dressing in their ‘national costumes’ and that these clothes were bright and pleasing in colour, but too tight to drape gracefully and so aesthetically being ‘more curious than beautiful’.Footnote 44 The royal couple were presented with a rich array of gifts, many handcrafted in the region, including walking sticks with ivory, gold and diamonds, an album of photos, an ornate kris, and a silver model of a Malay river house.Footnote 45

Audiences between the royals and local elites were an opportunity for Wallace to recount some of the power dynamics at play in this part of the Empire. For instance, some local rulers were depicted as more amenable to British imperial values and rule. Wallace discusses the differences between various Malay rulers, identifying some as being old school in preserving ancient court costumes, never learning English. Such rulers are described as scheming against the British at every opportunity, and these rulers are contrasted against others, such as the Sultan of Perak, who was described as educated in English, dressing in a more modern style with some hybrid-European dress and expressing appreciation of the influence of the British.Footnote 46 Wallace mused on the meeting with ‘Tungkee’ Ali, a descendant of the Malay chief who had ceded the island of Singapore to Raffles many years ago.Footnote 47 Wallace reflected that even Raffles as ‘far-sighted as he was’ could not have forseen what Singapore would become in three-quarters of a century.Footnote 48 In Wallace's assessment:

the little group of squalid huts has grown in to a fine city … the chief market of the civilized and developed hinterland, the centre of a vast circle of international trade, and a great naval stronghold, forming a most important link in the chain of coaling and refitting stations which connect England with China and Japan.Footnote 49

Here progress is linked alongside strategic economic and naval/military considerations connecting Britain to its interests in the Far East.

During the stay in Singapore Wallace describes sauntering in the park near Government House where ‘several thousand Malays of the lower classes’ were also strolling around. Here we see the locals being on display for the royal visitors. Wallace noted, ‘They have been collected to show their Royal Highnesses what ordinary Malays are like before they adopt European costume and habits.’Footnote 50 Wallace gives a description of the general populace as all ‘milling around’, enjoying the sights, and the royal couple travelling by horse and carriage through the city. (The reflections later were of children gleefully waving in delight not because of their royal visitors but because they had a day off school!) (see fig. 2)Footnote 51 The Chinese, he observed were to be found in all social classes from the barely clad rickshaw puller to the European hybrid-styled rich merchant. Sikh policemen (a ubiquitous reminder of the connections of empire) are described as ever vigilant in observing the crowd.Footnote 52

Figure 2. Duke of Cornwall and York in Singapore. CO1069/487 (1) Reproduced with the permission of the National Archives UK.Footnote 53

The local press gave extensive coverage to this royal visit and on a few occasions, the links to Raffles’ legacy were highlighted as explaining the success of this colonial port city. Wallace explained that it was the officers who assisted in this miracle of transformation ‘in the lusty bantling of Sir Stamford Raffles’ and who had created the well-developed settlement and brought profound change to the Malay Peninsula.Footnote 54 And the explanation is that ‘into the midst of a war-hardened, desperate population a few British officers were thrown, as one might cast a dog into the sea, leaving it to the dog to find its way or to go down.’ According to the news report, when Wallace asked how these Britons prevailed, the British officers claimed they then swam patiently and obstinately for a long time before finding their way; this account was described as ‘no-less splendid’ a story than that of Britons pacifying Upper Burma.Footnote 55 This against-the-odds story seems a dramatic flourish and certainly made the case for the remarkable success of Singapore as a leading entrepôt. Importantly, such a story of British pluck and determination would have had a readership back in the metropole and was reminiscent of popular jingoistic refrains found in imperial adventures such as those written by Rudyard Kipling or Henry Rider Haggard. On their departure, the Royal Highnesses and their party were transported via ‘gaily decorated Malay boats’ back to the main flotilla and the HMS Ophir. Footnote 56 (What is notable is that the ‘against the odds’ story of Singapore expounded in this account of the royal tour has very much become part of the national story of Singapore's triumph, albeit with a different cast of characters, as exemplified in Lee Kuan Yew's memoir, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story, 1965–2000.)

What do we make of this visit and official accounts thereof? In the Royal Tour of 1901 Singapore was but one stopover in a much larger tour of the empire but at the same time, its connectivity as part of the larger British world system is brought to the fore. Later press accounts (1910) would describe this tour as evidence that King George knew his dominions thoroughly.Footnote 57 Singapore was highlighted as a settlement worthy of its royal visitors as it was an important maritime hub, but also because it provided a vantage point for observing the Malay Peninsula (its economic hinterland). Singapore formed an important port of call for the royal visitors and it gave light to reflections on the notion of British benevolence and determination; benevolence in the treatment of ‘un-English’ subjects of Empire and at the same time praise for the determination which had transformed Singapore from jungle to a charming and well-developed settlement.

‘Cruise of the Special Service Squadron’: ‘Empire Cruise’ of 1923–4

Another example of Singapore's connections in the British imperial world was its inclusion as a port of call in the Special Service Squadron Cruise, better known as the Empire Cruise of 1923–4.Footnote 58 This cruise, which took place in the lull between what would be two world wars, saw the British Empire at its fullest territorial extent this, tempered, however, with a concern that the Empire was over-stretched and needed support. The driving motivation for this cruise then, was to make a visible demonstration of British naval might, but at the same time to encourage the dominions to do their part in bolstering their naval defences rather than relying only on the Royal Navy. Journalist and author V.C. Scott O'Connor travelled with the fleet to give an ‘on the spot’ account of this world-encompassing voyage.Footnote 59 He recounts:

On November 29th, 1923, on a cold grey morning, there weighed anchor at Devonport and Spithead six of His Majesty's ships, ‘Hood’, ‘Repulse,’ ‘Delhi,’ Dauntless,’ ‘Danae’ and ‘Dragon’ whose destiny it was to voyage around the world, to meet our kinsmen overseas, to carry to them a message of peace and goodwill, and to revive in their hearts and in ours the ties that bind us to them.Footnote 60

The aim of this cruise, in short, was to demonstrate British naval power but in doing so — in putting on a good show — to spur on further support for the British Empire. The ten-month cruise took HMS Hood and its battle cruisers and light cruisers some 38,000 miles around the world from West to East.Footnote 61 In this instance there were no members of the royal family on the tour, but King George sent messages via his Admirals conveying his fond memories of the Royal Tour of 1901, and of his high regard for Singapore.Footnote 62 This cruise was more a demonstration of naval power than a royal progress;Footnote 63 a common link, however, was the significance of travelling the waters and demonstrating British control over major ports and oceanic networks. It was also a chance to ‘show off new advances’ in relation to mechanisation; the HMS Hood boasted a hydroplane by Thornycroft & Co.Footnote 64 And importantly, in Scott's view, it was time to show that Britain had emerged from the strains of the First World War and was ushering in a new era of confidence in the Empire.Footnote 65

This tour had different aims — it reaffirmed Singapore's place in the imperial context as a port worthy of not only visiting but of staying for some days. Again, the cruise was chronicled by those on board the ships as well as locally based journalists. O'Connor's The Empire Cruise (1925) provides a detailed description of the fleet, with specific details as to the tonnage, guns, and the HMS Hood as the focus of particular adulation as the fastest (and most powerful — and expensive) ship in the world.Footnote 66 This cruise was also captured on a six-part film series, Britain's Birthright (now held in the Imperial War Museum archives) so that viewers back in the metropole could witness the fleet in action. The film's opening intertitle reads ‘In recent years the British Realms beyond the sea have seen little of the Royal Navy on which their security depends’; the cruise remedied this absence.Footnote 67 This film, just like the earlier royal cruise, was heavily didactic, demonstrating to a home audience and the subjects of empire alike that British naval might was still a force to be reckoned with and that the colonies and dominions also had a role to play in sustaining this strength.

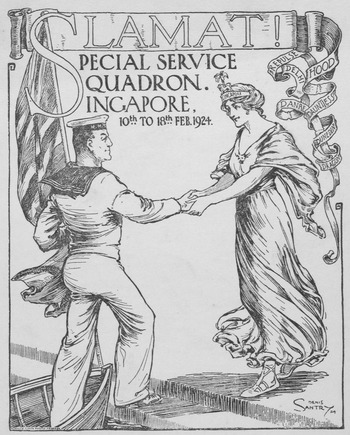

The battle cruisers sailed from Port Swettenham (Port Klang), arriving in ‘Singapur’ (sic) in heavy rain on 9 February 1924. They were joined by HMS Hawkins, Carlisle, Bluebell and Petersfield under Admiral Sir Arthur Leveson, the commander-in-chief of the China station.Footnote 68 The following day the fleet dressed ship, joined in this by every merchant ship in honour of the occasion. The Vice-Admiral, Rear-Admiral and all of the Captains for the Special Service Squadron (accompanied by personal staff) landed and enroute to meet the Governor of the Straits Settlement Sir Lawrence Guillemard, they were driven through crowded streets, lined with flags and troops. Singapore gave a resounding welcome to the visiting squadron, as demonstrated through the poster ‘Slamat!’ ‘Welcome!’ (see fig. 3). This poster reflects the celebration of empire. In the poster we see a British sailor (the Jack Tar as a symbol of not only naval but also imperial masculinity) being welcomed by a personification of Singapore.Footnote 69 Here the allusions are classical, Singapore is sandalled, and wearing a diadem (tiara) adorned with a palm and lion. This image is imperial and regal, there is little of the local present apart from the selamat greeting. The cartoonist, Denis Santry was an Irish-born architect living in Singapore and a partner in the prominent Swann and MacLaren firm. Featuring Santry's work may lead us to muse whether this was a deliberate shift from highlighting images of the antiquarian and exotic (think of 1901) to celebrating a modern colonial port.

Figure 3. Poster advertising the Singapore leg of the Special Service Squadron World Cruise (1924). National Heritage Board, image accession no: 2008-02359. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

This warm welcome is recorded in Britain's Birthright, which shows the docks gaily decorated with flags and lined with curious onlookers, an intertitle stating, ‘Vice-Admiral Field came ashore in his barge under a battery of admiring eyes’ with the crowded waterfront captured on screen.Footnote 70 In keeping with naval tradition, guns rang out, HMS Hood sounding 17 guns, and in reply HMS Hawkins saluted with 15 guns.Footnote 71 As McCreery reflects, ‘if during the Pax Britannica the guns of large warships (as opposed to small gunboats) were fired in anger relatively rarely, there were fired for ceremonial purposes often’.Footnote 72 Onlookers would have been suitably awed. Visitors to the HMS Hood were greeted in a similar manner, for instance the Sultan of Kelantan and Tunku Makhota (eldest son of the Sultan of Johor) were honoured with a 17-gun salute. Special guests to the fleet were greeted with a guard of honour and entertained onboard the HMS Hood. As would be anticipated of such an event, speeches extolled admiration for the power of the Royal Navy, and in turn, thanks was given in appreciation of Singapore's generosity as a host.Footnote 73 The similarities here to the Royal Tour of 1901 are striking; local dignitaries, Asian elites and the wider populace were drawn to participate in the celebrations. The fleet hosted some 29,000 visitors to their ships and in exchange enjoyed sports and other social activities.Footnote 74

The rank and file crew were also included in the festivities. There were dances and dinners and luncheons. Sailors from the squadron marched through the streets of Singapore and enjoyed the facilities of the Squadron Club, established to provide accommodation, food and refreshment for men when ashore.Footnote 75 Here was the strength and goodwill of the Navy on show. O'Connor described the reading room and entertainment in this Club in the highest terms as he believed it ‘illustrated the real feeling of the British dwellers in this far-off land towards our men’.Footnote 76 Similarly the local press opined, ‘we cannot speak for the rest of the Empire, but we accept the visit to Malaya as primarily an act of comradeship, an opportunity to establish a more human and personal touch with the Navy.’Footnote 77

This cruise and visit to Singapore also led to observations on the port-city's status within the British Empire, as both a centre for trade and a geopolitically strategic site. Its rapid development was highlighted for the reader. O'Connor reflects:

The city of Singapur [sic] is little more than a hundred years old. It is fast growing into one of the great cities and seaports of the world and it has already a population of nearly half a million souls, of whom three hundred thousand are Chinese. It is the most cosmopolitan place imaginable; but three elements stand out from the forest of its life — its common language, which is Malay; its Chinese industry and capacity for business; and, we may claim without pride, the constructive genius of our people.Footnote 78

O'Connor goes on to explain Singapore's success: ‘For it is we who imagined Singapur and made it’ — this prosperity was reliant on the justice and humanity established by the British and on the Navy's role as guardian of world peace. In this light, O'Connor mentions Singapore's strategic importance as on par with Gibraltar and Constantinople as an island that straddled ‘East and West’.Footnote 79 Despite these strategic assessments of Singapore, O'Connor was not without a touch of romance in his writing. He described the ‘luminous waters’ of the causeway between Singapore and Johor as giving a momentary likeness to ‘the other causeway’ which carried men across the waters in Venice.Footnote 80

Singapore was described as an exemplar of progress. Britain's Birthright similarly focused on Singapore's rapid development claiming that the port, when bought for Britain in 1819, had been ‘uninhabited’ but now was a ‘great modern city boasting fine modern buildings’, and to reaffirm this success, viewers were treated to scenes of the town hall, a bustle of cars and rickshaws as well as a statue of Raffles in the distance.Footnote 81 Once the fleet departed Singapore, interest in the cruise remained strong; the local press followed the progress of the Empire Cruise until its completion in September 1924.Footnote 82

Reflecting on cruises and Singapore as a hub

Both cruises explored here, albeit briefly, provide illustrations of Singapore's role as a port city of the British Empire, and of deep sustained connections to a larger network of imperial maritime outposts. Singapore's progress ‘from the vision of Raffles’ to a thriving port city is a common refrain in accounts relating to both cruises. The irony of course should not be lost that by 1901 there was concern that Britain's empire was showing signs of being stretched thin; by the time of the Empire Cruise, the empire itself was at its geographically largest expanse but fault lines (already apparent decades earlier) were rapidly widening; in the tours of 1901 and 1924 the maritime realm served as a unifying force. These cruises played a significant role in generating imperial propaganda; they celebrated the monarchy and British naval prowess throughout the empire. Ports of call were important not only from a logistical standpoint — for coaling and stocking supplies — but in demonstrating most effectively the expansive maritime reach of the British world system. From an official viewpoint on the ground (at the least) being part of the cruise itineraries was regarded as evidence of Singapore's importance as a hub within the British maritime empire.

Whether hosting royalty or the Royal Navy, issues of loyalty, progress, identity and connections to empire came to the fore during these tours. Parades and presentations, gifts and dinners all served to reinforce the sense of an ongoing relationship between the monarchy and metropole and its deferential imperial outposts. The co-opting of local communities (from elites to masses) in these celebrations demonstrates the continued importance — to the British and colonial administration — of empire's pageantry. That Singapore remained a premier port was a source of pride to not only the British but Singapore's colonial establishment and local elites. The British revered their ultramarine tradition as a cornerstone to their imperial identity and ideology; touring the great ports of Empire served to reinforce this conviction.

By examining two of the most prominent cruises of the empire, we have an illustration of how Singapore was viewed as a prized asset in a larger maritime network, one that was bonded not only by naval force but the movement of goods, people, and ideas such as loyalty to the empire. These cruises were intended to promote unity and a sense of connection; perhaps it is with this in mind that describing Singapore as the ‘Liverpool of the East’ evokes a certain image of an imperial outpost that embodied not only the progress and growth of Empire but a lasting connection to British maritime power.

Did these cruises give rise to a much longer history of Singapore being described as the quintessential ‘hub’ of the East? Certainly the empire cruises set the tone of the era for describing the people and places of the empire. As scholars, we should not be too quick to dismiss these terms or frames of reference for Singapore, however laden they are as evidence of a colonial past, as their legacy in fact continues — the National Museum of Singapore, for example, has a section in its permanent gallery on Singapore as the ‘Liverpool of the East’. Similarly, Turnbull's classic tome A history of modern Singapore, 1819–2005 offers a chapter on ‘The Clapham Junction of the Eastern Seas’ (1914–1941). And more recently, in light of Singapore's move to become a knowledge economy, the term ‘the Boston of the East’ was coined by former prime minister Goh Chok Tong in 1996; the reference here may not be colonial but it is unmistakably aspirational.Footnote 83 Singapore has also been described as the ‘Venice of the 21st Century’.Footnote 84 So while terms such as ‘Liverpool of the East’ were bandied about in the age of high imperialism, and have been set aside, the urge to describe Singapore as a hub remains pervasive in the modern nation-state.

We may see the links to Liverpool as a nostalgia for remembering Singapore's eminence as a colonial port city, but the references to Singapore as the ‘something (city/place) of the East’ reaffirm its long history as a hub in Asia replicating services and facilities not found elsewhere in ‘the east’. What is most salient for our discussion is to remember that Liverpool was closely associated with shipping, transport services, and industry, not glamour, but with a very distinct function and role in relation to Britain's global (and imperial) reach.Footnote 85 And while Singapore may no longer describe itself as the ‘Liverpool of the East’ its history as a colonial port city warrants further study as narratives of this maritime and imperial past continue to find echoes in the present.