Introduction

How does cabinet composition impact the cabinet decision-making process? While government formation is well-studied (see Laver, Reference Laver1998; Martin and Stevenson, Reference Martin and Stevenson2001), the question of how composition impacts ‘the process through which executive cabinets reach their final governmental outputs’ has received less treatment (Vercesi, Reference Vercesi, Andeweg, Elgie, Helms, Kaarbo and Muller-Rommel2020, 438). This article assesses the relationship between cabinet composition and cabinet decision-making in the arena of cabinet committees: groups of ministers tasked with policy or coordination responsibilities. Committee structure can be a useful and concrete window into dimensions of cabinet decision-making, such as collegiality – how the cabinet process induces inter-ministerial engagement, and collectivity – the distribution of policy influence among ministers. We theorize that these dimensions are correlated with cabinet composition: single-party or coalition, and variants therein.

To assess this, we employ a dataset of 45 cabinets from 11 parliamentary and semi-presidential systems. We draw two overall conclusions. First, cabinet committees in coalitions are significantly more collegial, on average, than single-party cabinets: cabinet committees under coalitions generate more interaction and engagement among ministers than under single-party government. Second, policy influence in cabinet committees under certain types of coalitions – minimal winning and minority – is less collectively distributed than under single-party majority cabinets. These findings provide evidence of two complementary goals of prime ministers and party leaders in managing coalitions: generating trust and informational ties among governing parties while locating influence largely within the smaller core of senior party leaders, who are most responsible for maintaining coalition agreements and promoting an overall governmental interest.

The article proceeds as follows. First, we describe the role of cabinet committees in parliamentary cabinets and review the literature on the relationship between government composition and cabinet decision-making structures. Building on this review, we explicate the theory and hypotheses to be tested. The third section discusses the data used, variable operationalization, and methods. We proceed to the main empirical analysis in the fourth section. Finally, we discuss the results and conclude.

Cabinet committees and coalition management in parliamentary government

Cabinet is the collective executive in parliamentary government, consisting of a prime minister and a set of ministers, most of whom are political heads of government departments (Barbieri and Vercesi, Reference Barbieri and Vercesi2013). Cabinet committees are groups of ministers tasked with coordination, decision-making, or implementation mandates, typically in specified policy fields. These systems began to arise during and after the Second World War as a response to the increasing size and scope of government activity, to reduce the workload of cabinet and effectively coordinate policy across government departments (Andeweg, Reference Andeweg, Weller, Bakvis and Rhodes1997, 69), which Thiebault (Reference Thiebault, Blondel and Muller-Rommel1993, 84) argues ‘constitutes perhaps the most important change affecting governments since the 1950s’.

Thus, cabinet committees can play an important role in strengthening efficient and effective policymaking. However, this role varies across contexts, being particularly central in Westminster cabinets: Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom arguably have the most well-developed committee structures (OECD, 2015, 288). Cabinet committees in these countries are delegated significant authority over policy formulation and decision-making. Canadian cabinet committees, e.g., are ‘extensions’ of cabinet with the power to decide most issues ‘subject to confirmation’ by cabinet (Privy Council Office, 2015); their decisions are rarely challenged, and then only by the prime minister (Savoie, Reference Savoie1999, 128). As well, because of the prevalence of single-party majority governments and constitutional practices favouring executive dominance, prime ministers have essentially unfettered discretion over committee structure and composition. This power means that cabinet committees are likely to be used in more overtly strategic ways to bolster prime ministerial leadership (Catterall and Brady, Reference Catterall, Brady and Rhodes2000).

The importance of cabinet committees varies in other parliamentary contexts in which coalitions are more common. Other actors, such as coalition party leaders, may be more central, and cabinet management may be done more by coalition committees or party–parliamentary mechanisms (Andeweg and Timmermans, Reference Andeweg, Timmermans, Strom, Muller and Bergman2008; Thies, Reference Thies2001). However, cabinet committees in these systems may still be key parts of cabinet decision-making. Of the 12 countries scoring 8 out of 10 or higher on the Sustainable Governance Indicators measure of ‘how effectively… cabinet committees coordinate proposals’, 9 currently have multiparty governing coalitions (SGI Network, 2020). Indeed, written coalition agreements often refer to committee structure and party allocations (Dunleavy and Bastow, Reference Dunleavy and Bastow2001, 13). For example, New Zealand’s 2017 coalition agreement specifies membership for minor party ministers on appointments and legislation committees, and others ‘as agreed between the Party Leaders’ (New Zealand Parliament, 2017, 6). The 2018 German Grand Coalition agreed to proportionally allocate committee places by party, while the 2010 agreement between the UK Conservatives and Liberal Democrats afforded the leader of the latter, as deputy prime minister, essentially a veto over cabinet committee structure and membership. Thus, cabinet committees can be studied in both single party and coalition contexts.

Cabinet committees engage scholarship on decision-making in cabinet governments (see Vercesi, Reference Vercesi2012, Reference Vercesi, Andeweg, Elgie, Helms, Kaarbo and Muller-Rommel2020). While Elgie (Reference Elgie1997, 223) argues that committees ‘do not necessarily damage the prospects of collective government and… may even enhance them’, others argue that robust use of committees constitutes a distinct mode of decision-making with implications for its collective character. Mackie and Hogwood’s (Reference Mackie and Hogwood1984, 311; Reference Mackie and Hogwood1985) pioneering studies of cabinet committees characterized such cabinet systems as generating ‘interrelated but fragmented decision-making arenas’: ‘interrelated’ because committees are constituted by the same actors – ministers – combined in overlapping groups, where these groups fragment rather than integrate the policy-making space at the cabinet level. Vercesi (Reference Vercesi2012, 17) argues that decision-making should be characterized as fragmented or integrated, with cabinet committees constituting an integrating mechanism under a prime minister’s oversight. Finally, and most importantly, Andeweg (Reference Andeweg, Weller, Bakvis and Rhodes1997, 62) identifies collegiality and collectivity as the two dimensions of cabinet government, referring to the distribution of power in cabinet and the centralization of decisions, respectively. In this framing, cabinet committees are labelled on the collective dimension as ‘segmented government’, between ministerial and full cabinet decision-making. While we use ‘collectivity’ in a similar way – a process engaging a whole group as opposed to one member or a smaller subgroup – we use collegiality slightly differently, partly because the distinguishability of Andeweg’s labels is somewhat unclear (Vercesi, Reference Vercesi2012, 14-17). While we recognize the potential for confusion, we believe this terminological choice is justified by our specific context. The general term ‘collegial’ refers to the amicability and closeness of relationships among colleagues, as opposed to antagonism. As below, this term captures more precisely our first measure of cabinet dynamics: the strength of interpersonal engagement among ministers induced by cabinet committees.

In this study, we consider cabinet committees in themselves as variably structuring patterns of collegiality and collectivity in cabinet decision-making, rather than as fitting within a single category such as a ‘segmented’ cabinet. Cabinet committees may reflect rigid segmentation along jurisdictional lines, but they may also reflect a more integrative approach. What is important about cabinet committees is that they are a mechanism through which the articulation of interests and the authority to influence decisions are channelled through subsets of the cabinet. These subsets necessarily bring together several, but not all, such interests, including and excluding ministers in the process. Thus, the question becomes how prime ministers and party leaders allocate ministers within the committee system.

Our basic premise is that a cabinet’s party composition has consequences for its decision-making as reflected in cabinet committees. This is of interest in parliamentary systems because single parties usually do not win legislative majorities and thus cannot form government on their own: coalitions are the norm, particularly in European systems (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012, 87). The question of which coalitions form and why has guided work since at least Gamson’s (Reference Gamson1961) work theorizing that coalition parties receive shares of cabinet positions proportional to their legislative strength. Riker (Reference Riker1962) introduced the concept of ‘minimal winning coalitions’: majority coalitions including no more parties than is necessary. Axelrod (Reference Axelrod1970), Austen-Smith and Banks (Reference Austen-Smith and Banks1988), Laver and Shepsle (Reference Laver and Shepsle1996), and others, considered explicitly the role of policy positioning. Subsequent research has extended in many directions, including coalition stability (e.g., Warwick, Reference Warwick1994), allocation of cabinet portfolios (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011), and formal coalition agreements (Moury, Reference Moury2012; Strom and Muller, Reference Strøm and Müller1999). This literature, especially earlier work, tended to assume that the only outcome of interest is formation itself: formation was the ‘dependent variable’ (Andeweg and Timmermans, Reference Andeweg, Timmermans, Strom, Muller and Bergman2008, 274). We know comparably less about how formation affects cabinet decision-making processes, but case studies are illuminating. Paloheimo (Reference Paloheimo2003, 233), for instance, describes cabinet committees in Finland as essential policy coordination mechanisms in a decentralized multiparty system, while Moury (Reference Moury2012, 77-78) finds that they perform increasingly important representative and substantive roles in the management of Dutch coalitions. In Denmark, ministerial membership on cabinet committees is an important signal of the distribution of power within the executive (Hansen Reference Hansen, Christiansen, Elklit and Nedergaard2020, 119). And in New Zealand, McLeay (Reference McLeay and Miller2010, 200) notes that committee structure is an important aspect of inter-party negotiations because coalition party leaders use committees to ‘influence the interpretation of party manifestos [and] the pace of legislative change, and… ensure that their priorities are recognised’. Thus, there is case evidence that party composition of cabinets has a determinative effect on cabinet committees.

Some cross-case studies also allude to the role of committees. Mackie and Hogwood (Reference Mackie and Hogwood1984, 288) suggest but do not test whether Gamson’s law applies at the committee level or only at the ‘more highly visible’ cabinet level. Frognier (Reference Frognier, Blondel and Muller-Rommel1993, 66-67) compares the effects of single party and coalition governments on cabinet decision-making across several dimensions, finding that ‘committees are used more often by coalition and single-party minority cabinets than by single-party majority cabinets’ to manage conflict. Andeweg and Timmermans (Reference Andeweg, Timmermans, Strom, Muller and Bergman2008) assess the relative prevalence of internal (within cabinet) and external (party or parliament) arenas in managing conflict in coalitions, an approach applied to Central and Eastern European cases recently (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Ilonszki, Muller, Bergman, Ilonszki and Muller2019, 541). These cross-case studies are helpful but systematic theorizing or testing of these claims has been absent. This study is the first to do so quantitatively and cross-nationally.

Cabinet composition and cabinet committee structure: Theory and hypotheses

We theorize that cabinet composition is related to collegiality and collectivity in cabinet committee structure. Since we know that cabinet committees are central arenas for cabinet decision-making in many systems, the party composition of cabinets, especially coalitions, should be reflected in their structure. Our theory is situated against canonical models of coalition formation (e.g., Austen-Smith and Banks, Reference Austen-Smith and Banks1988; Laver and Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996). Austen-Smith and Banks (Reference Austen-Smith and Banks1988) deduced that coalition parties collectively influence policy as a function of their size, while Laver and Shepsle (Reference Laver and Shepsle1996) introduced the influential ‘ministerial government’ model in which equilibrium coalitions form when each party’s ministers are guaranteed control over their policy areas: ministers are autonomous ‘policy dictators’. As Bäck et al. (Reference Bäck, Müller, Angelova and Strobl2021, 4) argue, this is a consequence of ‘the need to divide labour, acquire policy expertise to deal with complex issues and draft feasible legislation’.

While the model is appealing, it has been challenged on several fronts. Warwick’s (Reference Warwick1999a, Reference Warwick1999b) extended colloquy with Laver and Shepsle raises empirical concerns with the ministerial autonomy assumption, as indeed did Laver and Shepsle’s (Reference Laver and Shepsle1994) original volume. Thies (Reference Thies2001) shows that the equilibria predicted under the model are Pareto inferior to those in which ‘managed delegation’ of coalition compromise occurs. Martin (Reference Martin2004) finds that coalition government agendas are ‘accommodative’ to all policy preferences of coalition parties. Indeed, coalition management literature is essentially a response to the ministerial government model: e.g., coalition agreements as a mechanism to ‘tie the hands’ of ministers (Moury Reference Moury2012; Strom and Müller, Reference Strøm and Müller1999) or legislative committee oversight (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Müller, Angelova and Strobl2021). We frame cabinet committees, similarly, as ways to induce compromise and accommodation through cross-ministerial and cross-party ties. This is so even in single-party contexts: cabinet committees in Canada, for instance, are associated with a shift away from a ‘departmentalized’ cabinet system to an ‘institutionalized’ one (Howlett et al., Reference Howlett, Bernier, Brownsey, Dunn, Bernier, Brownsey and Howlett2005).

We also question the assumption of departmentalism from another perspective. The model is at odds with a stream in the public policy and governance literature which emphasizes the role of networks, horizontal bureaucratic and political coordination, centralized policy steering mechanisms, and ‘presidentialization’ within the executive (see Bouckaert et al., Reference Bouckaert, Peters and Verhoest2010; Dahlström et al., Reference Dahlström, Peters and Pierre2011; Elgie and Passarelli, Reference Elgie, Passarelli, Andeweg, Elgie, Helms, Kaarbo and Müller-Rommel2020; Peters, Reference Peters2018; Poguntke and Webb, Reference Poguntke and Webb2005). This literature indicates that most modern policy problems are not neatly divisible into independent departmental jurisdictions; their solutions require collaboration and compromise across broad swathes of government activity. Ministerial autonomy means little if policy choice cannot be translated into policy outcomes. Coupled with the ‘decentring’ of governance under New Public Management in the 1980s and 1990s, policy coordination problems have led political leaders to seek mechanisms to achieve greater cross-government coherence and integration.

Some of these mechanisms are encapsulated in the concept of ‘presidentialization’: increasing autonomy of leaders from parties, legislatures, and even their own executive, in part through the enhancement of ‘centres’ of government (Poguntke and Webb, Reference Poguntke and Webb2005). Among others, Bäck et al. (Reference Bäck, Dumont, Meier, Persson and Vernby2009), Kolltveit (Reference Kolltveit2012), and Poguntke and Webb (Reference Poguntke and Webb2015) uncover some evidence for this trend even in coalition contexts. For example, Poguntke and Webb (Reference Poguntke and Webb2015) find that prime ministers have been ‘increasingly able to mobilize power resources which allow them to govern more independently of their own parties and their coalition partners’ (271). Formally, Dewan et al. (Reference Dewan, Galeotti, Ghiglino and Squintani2015) construct a model in which centralized authority and cabinet exchange of information optimizes policy quality as compared to ministerial autonomy. Our perspective assumes that ministers are not policy dictators. Trends in both policy governance and executive politics suggest that governments, whether they succeed or not, put significant effort into strengthening cross-departmental coordination, often led by enhanced centres of government. While departmentalism certainly exists, other equally compelling trends incentivize policy compromise and coordination among ministers and parties within cabinets. Thus, it should not be surprising that governments make efforts to induce cabinet-level coordination, whether they are coalitions or not. Our theory is an attempt to explain one such effort: cabinet committees.

An important aspect of cabinet formation is the allocation of cabinet committee positions. However, any (real) system of cabinet committees distributes positions unequally, inducing variation in ministerial engagement. For example, a minister who sits on every committee is much more involved in cabinet committee deliberation and decision-making than a minister who sits on one committee. The first minister has more potential influence than the second, within the structure of cabinet committees. We can aggregate minister’s potential influence to characterize key aspects of the overall committee structure which we associate with variation in cabinet composition. In particular, the resulting distributions of influence in cabinet committees reveals two important dimensions: collegiality and collectivity.

Collegiality refers to a pattern of cooperative interaction among colleagues with the development of shared goals and a common ethos. Collegial cabinets are those in which ‘members are closely associated to each other’ (Blondel and Manning, Reference Blondel and Manning2002, 462). In the committee context, we use collegiality to refer to the extent to which committee structure induces interaction among ministers through shared membership. All else equal, the more that cabinet committees induce ministerial interaction, the more collegiality is strengthened. Collegiality is important in the context of government composition and multiparty coalitions in several ways.

First, coalition leaders’ interests in stable, effective government are furthered by collegiality to the extent it enhances policy coherence and inclusion of ministers and parties in cabinet decision-making. Greater collegiality generates centripetal forces in which ministers and parties, often guided by central coordinators in party leaders’ and central bureaucratic offices, are more likely to weight broader coalitional, governmental interests more strongly than in less collegial structures, where pursuing own-party interests may be stronger. As discussed above, portfolio allocation itself encourages fragmentation as parties jealously guard the rewards of portfolio payoffs (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011; Warwick and Druckman, Reference Warwick and Druckman2006). A Green party able to secure the environment portfolio in a coalition, e.g., may not prima facie prefer strong collegiality; yet, its goals are unlikely to be achieved without collaboration and support from other departments and the centre. If ministers and parties are highly intertwined with other ministers and parties within the cabinet committee structure, the attraction of exclusive responsibility for one policy area may be traded off for broader influence in other policy areas.

Second, fostering collegiality reduces political and psychological barriers to interparty cooperation and compromise. While coalition agreements list specific policy goals, their actual implementation is far from guaranteed; moreover, many policy statements are intentionally vague, leaving significant discretion for governments to choose means and ends (Moury, Reference Moury2012). Governments also confront the force of events that necessitate urgent response, sometimes contrary to agreements. Thus, the ability to cooperate and compromise among parties in coalition is central to governments’ ongoing effective functioning. Politically, in terms of ideological division and parties’ desire to maintain distinctive ideological identities, structurally induced collegiality can encourage interpersonal deliberation, communication, and synthesis among differing perspectives. This may help coalition partners to obtain mutual credible commitments to shared goals and joint strategies to ‘sell’ coalition policymaking to party and public constituencies. Psychologically, repeated interaction in small groups such as cabinet committees can encourage social trust and reciprocity to develop, while eroding prior antagonisms. This general phenomenon should arguably be stronger in the cabinet committee and coalition context, where actors already have strong incentives to cooperate.Footnote 1

The second dimension of cabinet committee structure that we investigate is collectivity. This refers to the concentration or dispersion of power in the executive, a long-standing concern in cabinet government studies. On one extreme lies ‘prime ministerial government’, in which effectively all political power rests with the prime minister (Andeweg, Reference Andeweg, Blondel and Muller-Rommel1993). Prime ministers make the most important decisions across all policy areas, often aided by large, capable personal offices, while cabinet is of secondary importance, playing an advisory or representational role. On the other extreme is a ‘cabinet of equals’ model in which all ministers are equally influential. In the context of cabinet committees, collectivity is demonstrated through the distribution of ministerial involvement in the system. A cabinet committee system could have a small number of ministers with high levels of involvement, in which most ministers’ involvement is limited. Conversely, a system could be structured so that minister’s involvement is equalized. No cabinets lie at either extreme in practice: most cabinets distribute committee involvement unequally but not monopolistically. We expect that patterns of clusters in the distribution of power will be evident: a smaller group of cabinet ministers – a ‘core’ or ‘inner cabinet’ – will have more influence than the rest of cabinet (Barbieri and Vercesi, Reference Barbieri and Vercesi2013, 534-35). In coalitions, the core tends to consist of the party leaders and senior party figures, while in single-party governments it includes the prime minister and leading ministers, elevated by competence, political/party standing, or loyalty.

We note here that the theoretical contribution also involves methodological innovation: the use of social network analysis to measure these cabinet committee properties. A social network is ‘a structure composed of a set of actors, some of whose members are connected by a set of one or more relations’ (Knoke and Yang, Reference Knoke and Yang2008, 8). Analysis of political phenomena as networks has been increasingly common, e.g., to study terrorist networks, international trade, and Congressional organization and polarization (see Ward et al., Reference Ward, Stovel and Sacks2011). Cabinet committees inherently form network structures: all actors are easily identifiable, and the networks are relatively small and thus easily verified as complete. This makes network analysis ideal for our purposes.

We use network analysis to measure collegiality and collectivity, framing ministers as nodes and shared committee membership as ties. A collegial cabinet committee structure is one in which there are extensive ties between ministers: many ministers have many ties to each other through shared committee membership. A less collegial structure will have more ministers with fewer ties to other ministers. The more ties ministers have to each other through cabinet committees, the more interaction they experience, and the more collegiality is generated and maintained. Collectivity is measured by the ‘core-periphery’ structure: the extent to which there are highly connected ministers who have strong ties to each other, the core, and less connected ministers who have ties to the core but not strongly to each other, the periphery (Borgatti et al., Reference Borgatti, Everett and Johnson2018, 258).

We illustrate these concepts by depicting three hypothetical ministerial networks in Figure 1. Each node represents a minister; lines between ministers represent shared committee membership. Network (a) is a perfectly collegial network: every member is connected to every other member. Every minister sits on all committees, so they all enjoy the maximum interaction induced by the committee structure. This network is also maximally collective as it has no core–periphery structure of more and less influential ministers. Network (b) is less collegial than (a) but still represents relatively high collegiality: most ministers are members of several committees. However, there is a clear core–periphery structure, with ministers ‘a’, ‘b’, and ‘c’ being much more central than others. Finally, (c) departs significantly from the first two in that it depicts a fragmented committee structure where there are ties between subgroups of ministers but no ties between groups. This network has very low collegiality with ministers having few ties to other ministers, while the distribution of influence is relatively equal among ministers; most ministers have equally low interaction within the cabinet committee structure.Footnote 2 No actual committee structures resemble such a network.

Figure 1. Collegiality and collectivity in example ministerial network structures.

Turning to our core hypotheses, we expect that differences in cabinet composition generate differential incentives that shape committee structure and the predominant purpose of cabinet committees. Actors responsible for cabinet committee structure act strategically and rationally when constructing committees. Since cabinet committees are important arenas for cabinet decision-making and coalition management, their composition ought to reflect variation in the coalition context. As noted earlier, this is sometimes reflected explicitly in the coalition agreements signed by coalition parties. Thus, the assumption that committee structures are products of rational decision-making, and that they are partly determined by coalitional considerations (or lack thereof), is reasonable.

Single-party majority cabinets are the baseline category. They have no incentive to formally recognize other parties and they tend to be associated with systems with strong party discipline and cabinet solidarity. The distribution of influence in single-party majority cabinet committees, therefore, likely depends on aspects such as prime ministerial preferences and styles. In some cabinets, it may be clear to the prime minister that only a few ministers merit central, influential positions. In others, influence within cabinet committees will be more equally distributed. Our assumption is that these idiosyncratic tendencies will cancel, producing a baseline against which to measure systematic effects of other cabinet types, for which we make substantive claims.Footnote 3

The first set of claims concerns the effects of cabinet composition on cabinet committee collegiality and collectivity. Coalitions introduce more uncertainty about and potential friction in cabinet decision-making than single-party majorities. Such inter-party conflict risks government instability or perception of incompetence. Therefore, mechanisms of cooperation and conflict management in cabinet should be more important in multiparty contexts. Moreover, multiparty coalitions inherently decentralize power by moving cabinet and committee allocation distribution choices from a single individual (e.g., a prime minister) to coalition party leaders. Coalition management is aided by meaningfully involving parties and ministers in deliberation and decision-making as much as possible. This inclusivity is not simply a numbers game of appropriately ‘placating’ coalition parties, but about strengthening interpersonal relationships among parties and ministers and seeking enhanced policy coordination. At the same time, we would expect that coalitions also should be less equal, on average, in terms of the distribution of ministerial influence. This is because coalition management also benefits from establishing a core group of coalition leaders to resolve inter-party disputes and maintain intra-party discipline. Thus, there should be a more evident ‘core–periphery’ structure in coalitions than in single-party governments, on average. This leads to the general hypothesis H1:

H1: Multiparty (coalition) governments will be more collegial but less collective than single-party governments.

We also investigate differences among coalition types. The incentives for inducing collegiality in cabinet committees should be somewhat stronger when more parties are in coalition, especially when all parties are needed to maintain majority legislative support (i.e., minimal winning coalitions). We expect cabinet committee systems in oversized and minority coalitions to be similarly driven by coalitional considerations, but at a lower level compared to minimal winning coalitions, since government survival is less dependent on party inclusion. Conversely, minimal winning coalitions generate the strongest incentives to maintain coalition compromises and manage conflict through a core–periphery structure in which party leaders are significantly more influential than other cabinet ministers. Therefore, we expect that government compositions that include more parties, particularly those that are minimal winning, will be less collective than single-party majority governments. That is, strong inner cabinets and distinct hierarchies of influence are more likely in multiparty governments than single-party governments. These expectations generate the following hypotheses:

H2: Relative to single-party majority governments, cabinet committees in multiparty minimal winning coalitions will be more collegial and less collective.

H3: Relative to single-party majority governments, cabinet committees in multiparty minority coalitions will be more collegial and less collective, but minority coalitions will be less collegial and more collective than minimal winning coalitions.

H4: Relative to single-party majority governments, cabinet committees in multiparty oversized coalitions will be more collegial and less collective, but oversized coalitions will be less collegial and more collective than minimal winning coalitions.

Hypotheses H2 through H4 order coalition types, from most collegial and least collective to least collegial and most collective, as follows: multiparty minimal winning, multiparty oversized, multiparty minority, single-party. This ordering, though, is more speculative than the expectation of a significant difference in collegiality and collectivity between single-party and multiparty cabinets, as expressed in H1.

One issue with this categorization is that it may obscure differences in the multiparty composition of cabinets. For example, a coalition with three parties in which there is one dominant party and two minor parties may look more like a single-party majority cabinet than a coalition with three equally contributing parties. In other words, both the number and the relative size of parties in a coalition may matter for committee structure outcomes. We thus separately examine the expectation that the relative size of parties in a coalition has an effect over and above the bare fact of constituting a multiparty executive (Frognier, Reference Frognier, Blondel and Muller-Rommel1993, 44), employing an ‘Effective Number of Cabinet Parties’ (ENCP) measure of the ‘multipartyness’ of a government. This suggests the following hypotheses:

H5: As ENCP increases, the overall collegiality in cabinet committee structure increases.

H6: As ENCP increases, the overall collectivity of a cabinet committee structure decreases.

Data and methodology

This section describes the study’s data and methods. The unit of analysis is the cabinet, as defined in the ParlGov dataset (Döring and Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2020).Footnote 4 The initial universe of cases included parliamentary and semi-presidential systems with functioning cabinet committees, according to Andeweg and Timmermans (Reference Andeweg, Timmermans, Strom, Muller and Bergman2008), SGI Network (2020) and author’s investigation. This list was narrowed by availability issues to 11 countries.Footnote 5 Efforts were made to extract committee data for five recent cabinets: this was achieved for Australia, Canada, Finland, Ireland, Israel, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom while partial data was obtained for Denmark, Iceland, the Netherlands, and Spain. In total, the data set includes 45 cabinets, listed in online supplementary table S1. While the imbalanced and partial country coverage is not ideal, selection bias is minimized as we are not comparing countries but cabinet composition types, across which there is reasonable coverage. The data were collected in phases, most recently in December 2020. Summary statistics for all variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary statistics for model variables

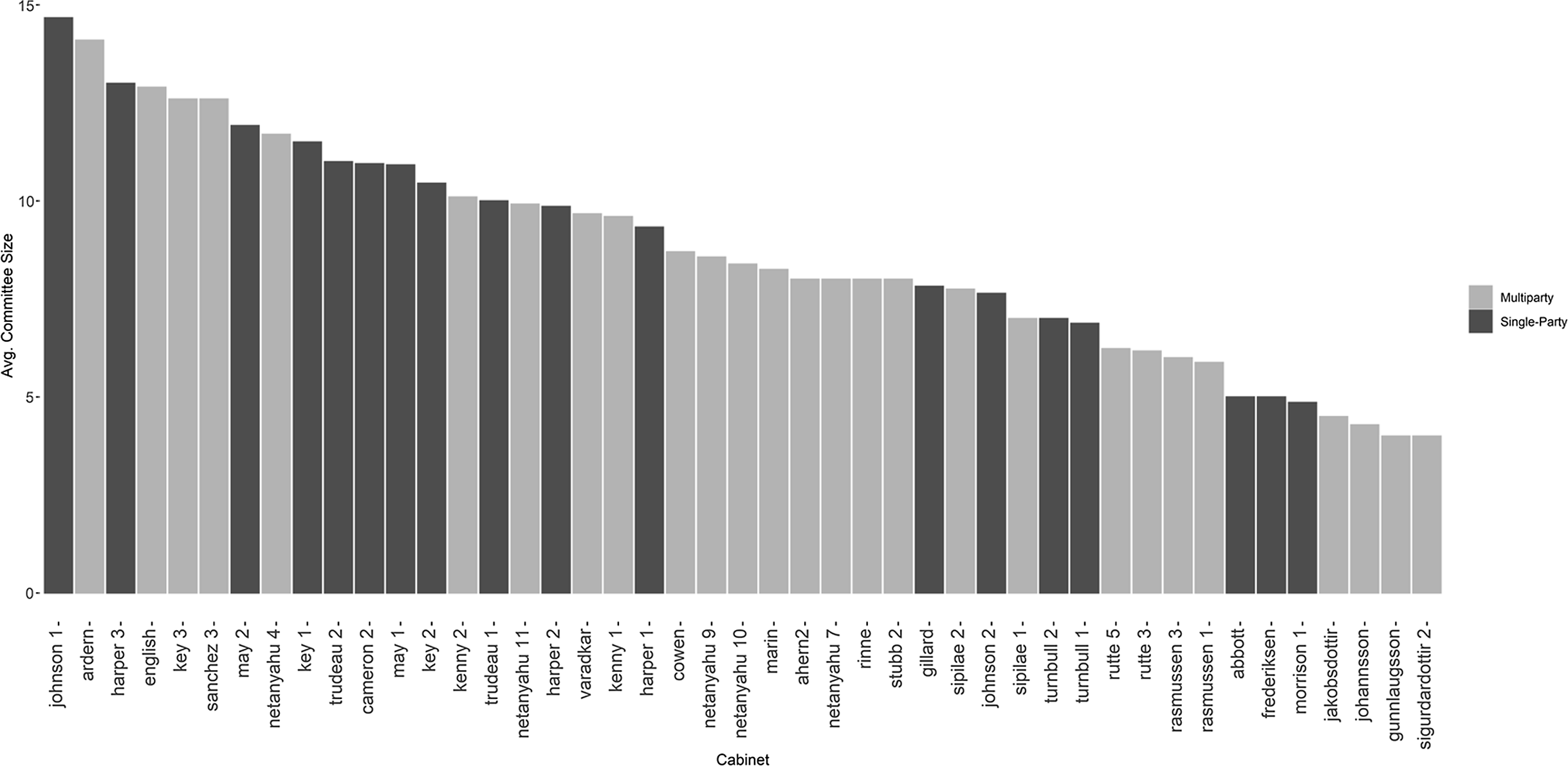

Considerable variation exists among cabinets in terms of number and typical sizes of committees. While space does not permit a full descriptive account of this variation, Figures 2 and 3 depict the number of committees (Figure 2) and average size of committees (Figure 3) for each cabinet in the data set, with single-party/coalition also indicated. Israel’s cabinets are clearly notable in terms of a high number of committees (over 20), while the number of cabinet committees in Finland has been fixed at four. The average number of committees is just under 10. The largest committees in terms of members are mostly found in the Westminster countries, while Scandinavian committees tend to be smaller: the overall mean is 8.7. This is mostly a function of cabinet size: the correlation between the number of cabinet ministers and average committee size is 0.72. Interestingly, within-country variation is generally small, suggesting that characteristics of cabinet committee structure are relatively entrenched within systems. There appears to be no systematic relationship between single-party/coalition status and either number or size of committees.

Figure 2. Number of cabinet committees by cabinet.

Figure 3. Average cabinet committee size by cabinet.

The dependent variables are collegiality and collectivity in cabinet committee structure. To measure collegiality, we measure each committee system’s density: the sum of all ties, excluding self-directed ties, as a proportion of all possible ties (Borgatti et al., Reference Borgatti, Everett and Johnson2018, 174). Density characterizes ‘the extent to which the nodes in a network are connected with each other’ (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Keller and Zheng2017, 3.2). When nodes can have more than one tie to other nodes, as here, calculating the number of possible ties is difficult, since it depends on the maximum number of ties a node can have, which can be indeterminate. We calculate the number of possible ties as the number of ties in the network if all members sat on all committees. This produces the following formula for density, modified from Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Keller and Zheng2017):

Where x i,j is the entry in the i-th row and j-th column of the adjacency matrix, k the number of cabinet committees, and n the number of ministers. This is equivalent to the average degree centrality as a proportion of the highest possible average degree centrality in a network. The collegiality measure theoretically ranges from 0, when no ministers share committee membership with any other ministers, to 1, when all ministers sit on all cabinet committees. The mean collegiality score is 0.17, indicating that 17% of all possible shared committee memberships, on average, are realized.

Our measure of collectivity employs the concept of a core–periphery structure (Borgatti and Everett, Reference Borgatti and Everett2000; Borgatti et al., Reference Borgatti, Everett and Johnson2018). This is evident when some nodes are well connected to each other – the core – and other nodes are connected to the core but minimally to each other – the periphery (Borgatti et al., Reference Borgatti, Everett and Johnson2018, 258). The network analysis program UCINET implements an optimization algorithm which estimates a continuous measure of ‘coreness’ for each node and finds the set of coreness scores that maximizes the fit between the data matrix and the matrix

![]() $\Delta = c{c^T}$

, where

c

is a vector of ‘coreness’ scores for each node,

c

i

$\Delta = c{c^T}$

, where

c

is a vector of ‘coreness’ scores for each node,

c

i

![]() $ \in \left[ {0,1} \right]$

(Borgatti et al., Reference Borgatti, Everett and Freeman2002). These scores are correlated, for all possible core sizes from 1 to n – 1, with an ideal core–periphery structure in which core nodes score 1 and periphery nodes score 0. The largest correlation produced by this algorithm is a measure of how well a core–periphery structure fits the data (Borgatti and Everett, Reference Borgatti and Everett2000, 379). Since the collectivity variable expresses the equality of influence in cabinet committee structure, we subtract the core–periphery correlation from one. The mean collectivity score is 0.15, indicating that the average correlation between the observed data and the ideal core–periphery pattern is 0.85. The general strength of the core–periphery structure, and the corresponding lack of collectivity in cabinets, is notable. Most cabinets look much more like network example (b) in Figure 1 than (a) or (c): a small core group of ‘super ministers’ with a large group of less influential ordinary ministers.

$ \in \left[ {0,1} \right]$

(Borgatti et al., Reference Borgatti, Everett and Freeman2002). These scores are correlated, for all possible core sizes from 1 to n – 1, with an ideal core–periphery structure in which core nodes score 1 and periphery nodes score 0. The largest correlation produced by this algorithm is a measure of how well a core–periphery structure fits the data (Borgatti and Everett, Reference Borgatti and Everett2000, 379). Since the collectivity variable expresses the equality of influence in cabinet committee structure, we subtract the core–periphery correlation from one. The mean collectivity score is 0.15, indicating that the average correlation between the observed data and the ideal core–periphery pattern is 0.85. The general strength of the core–periphery structure, and the corresponding lack of collectivity in cabinets, is notable. Most cabinets look much more like network example (b) in Figure 1 than (a) or (c): a small core group of ‘super ministers’ with a large group of less influential ordinary ministers.

We employ three related measures for cabinet composition. The first two use the standard categories determined by the government’s single or multiparty status and its legislative seat share (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012). The first measure is the dichotomous single or multiparty status. The second measure adds seat share: majority, minority, minimal winning (parties jointly sufficient and individually necessary for a majority), or oversized (parties jointly sufficient for a majority where at least one party is not necessary for a majority). This creates five cabinet types: single-party majority, single-party minority, multiparty minimal winning, multiparty minority, and multiparty oversized. These measures were extracted from ParlGov (Döring and Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2020). Importantly, there is reasonable variation across cases. Single-party majorities, single-party minorities, and multiparty oversized types each constitute 20% of cases, multiparty minority 13%, and multiparty minimal winning 27%. The single-party/multiparty split is 40–60%. The reference category for government type is single-party majority; all effects are relative to the single-party majority effect.

Third, we adapt the Laakso-Taagepera Index (Laakso and Taagepera, Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979) to measure the Effective Number of Cabinet Parties (ENCP) as a weighted measure capturing the number and strength of parties’ contribution to the coalition. ENCP is calculated as

![]() $1/\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^n p_i^2$

, where

$1/\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^n p_i^2$

, where

![]() ${p_i}$

is the proportion of cabinet portfolios held by the i-th party in a cabinet of n parties. Any single-party government has an ENCP of 1; any multiparty coalition will have an ENCP greater than 1. The average ENCP in the dataset is 1.83; the highest is 4.1 (Israel 2013-14).

${p_i}$

is the proportion of cabinet portfolios held by the i-th party in a cabinet of n parties. Any single-party government has an ENCP of 1; any multiparty coalition will have an ENCP greater than 1. The average ENCP in the dataset is 1.83; the highest is 4.1 (Israel 2013-14).

Scores on these measures are shown in Figure 4. Interestingly, no cabinets are simultaneously highly collegial and highly collective. There is a strong negative trend: highly collegial cabinets are low in collectivity, and highly collective cabinets are not very collegial. The hypotheses relating government composition to collegiality and collectivity receive preliminary support: multiparty cabinets seem to be more collegial and somewhat less collective than single-party cabinets. This is also evident in the right panel of Figure 4, which displays collegiality and collectivity by the other two cabinet composition measures. Though there is significant variation among categories in both (a) and (b), on average, multiparty cabinets are more collegial and less collective, with minimal winning cabinets the most collegial and least collective and single-party majorities the least collegial and most collective. Plots (c) and (d) show a less clear trend between the coalition size measure and outcomes.

Figure 4. Collegiality and collectivity scores by cabinet composition measures. Left: Single-Party vs. Multiparty Cabinets. Right: (a) Collegiality Scores by Cabinet Type, (b) Collectivity Scores by Cabinet Type, (c) Collegiality Scores by ENCP, (d) Collectivity Scores by ENCP.

The models include cabinet size, number of cabinet committees, and a cabinet’s ideological positioning and span as controls. Cabinet size is the total number of ministers. Larger cabinets should be less collegial and less collective than smaller cabinets simply as a measurement artefact: the larger a cabinet is, the more possible ties there are between its members. Unless committees become very large or numerous, the average degree centrality in large cabinets will be lower than in smaller cabinets. Not controlling for cabinet size thus contaminates estimates of the independent effect of cabinet composition. We control for the number of cabinet committees for similar reasons. Collegiality and collectivity should vary by the number of committees for a fixed cabinet size, since increasing the number of committees necessarily increases the possible memberships. The number of committees is not highly correlated with cabinet size (r = 0.38), suggesting that they may have distinguishable effects.

We also control for cabinet ideology, assuming ideological positioning may influence structures of cabinet decision-making. Each party’s ideology is extracted from the aggregated expert coding in ParlGov, from 0 (extreme-left) to 10 (extreme-right) (Döring and Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2020). These are used to calculate the mean ideology. For single-party cabinets, these are the score of the party. For coalitions, the mean ideology is weighted by party (Döring and Schwander, Reference Döring and Schwander2015).Footnote 6 Second, we adjust for a cabinet’s ideological span: the range of party ideologies in the government. Inter-party conflict mediation and coordination are more likely to be salient when there is policy divergence among coalition parties (Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005, 97). Thus, the ‘more collegial, less collective’ expectation for multiparty cabinets applies here: the greater the ideological span, the more likely it is that cabinet committee structure induces more inter-ministerial engagement while also creating a smaller core of more influential party leaders to enforce coalition agreements and government priorities. Ideological span is the absolute value of the difference in ideology scores between the lowest and highest scoring parties in a coalition.

We estimate six models for the hypotheses associating government composition to cabinet decision-making: two models with the dichotomous measure to assess H1 and four separate models for government type (H2 to H4) and coalition size (H5 and H6) for both collegiality and collectivity. Cabinet size, number of cabinet committees, and cabinet ideology mean and span are included as controls in all models. The method of estimating the hypothesized effects is ordinary least squares regression with clustered standard errors, by country, with a small-sample correction on degrees of freedom to calculate significance tests, as implemented in the plm R package. Hausman tests were conducted to determine whether country should be treated as a fixed or random effect, resulting in fixed-effects models for all collegiality estimates and the model of collectivity and coalition size. The remaining collectivity models are random effects models. Diagnostics on the models showed no issues with multicollinearity and only minor deviations from normality in the residuals. Two models were found to have significant levels of heteroskedastic errors, but their impact is accounted for insignificance testing by employing robust standard errors.

Results

Results from estimating the six regression models are given in Table 2. Models (1) through (3) estimate the collegiality outcome, (4) through (6) collectivity, for each of the measures of cabinet composition: single-party/multiparty, cabinet type, and coalition size. In addition to the coefficient estimates and standard errors, we report several measures of model performance: R-squared, Adjusted R-squared, and Root Mean Squared Error. For relatively parsimonious models, collegiality models (1) and (2) perform reasonably well, even after adjusting for the number of parameters (the adjusted R2 values). However, the collectivity models demonstrate rather poor fit. This is unsurprising, though, since the need for random effects is an indication that unobserved factors which affect the outcomes and vary between countries but not within countries are present. Variation in collegiality is explained more strongly by the included effects in the model compared to the collectivity outcome. Indeed, F-tests (for the fixed effects models) and Chi-squared tests (for the random models) of joint coefficient significance demonstrate this: the collegiality models show statistically significant results while the collectivity models do not (model (1): F5,29 = 4.90, p = 0.00; (2): F8,26 = 3.38, p = 0.01; (3): F5,29 = 3.55, p = 0.01; (4): X2 (5,45) = 2.33, p = 0.80; (5): X2(8,45) = 9.11, p = 0.33; (6): F5,29 = 1.57, p = 0.20)). Put plainly, collegiality in cabinet decision-making appears to be significantly related to factors which vary by cabinet, within and across countries, while the degree of collective decision-making is strongly variant across countries but not evidently across cabinets within countries, at least in the sample of cabinets in this study.

Table 2. Estimates of cabinet composition effects on cabinet collegiality and collectivity

Entries are ordinary least square coefficients with cluster standard errors in parentheses. Dependent and control variables are standardized. Significance levels: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Comparing the measures of cabinet composition on the R2 and RMSE statistics suggests that the dichotomous and categorical measures are better models than the continuous ENCP measure.Footnote 7 Of the two, the categorical cabinet type models (2) and (5) are marginally better performing than the others, though the differences are small and the models are punished more significantly when adjusting for the greater number of estimated parameters. Overall, the fit measures suggest that these models are reasonable starting points, but that future work should consider the role of systemic factors which vary only across parliamentary systems and expand the set of potentially determinative factors beyond what was available here.

Turning to our hypotheses, H1, the claim that multiparty cabinet committee systems will be more collegial and less collective than those under single party, is supported on the first claim but not the second. Model (1) shows that coalition systems are significantly more collegial than single-party systems (b = 0.75, p < 0.001). The effect is both statistically significant and reasonably large. The estimate for a multiparty effect on collectivity, however, is not statistically significant, though in the expected negative direction. H2 through H4 assert that single-party cabinet committee systems will be the least collegial and most collective, followed by multiparty minority and oversized, with minimal winning coalitions the most collegial and least collective cabinet type. For collegiality, only the multiparty minority effect is statistically significant at the p < 0.01 level, though both the minimal winning and oversized coefficients were significant at the p < 0.10 level. The ordering of cabinet types, in comparison to single-party majorities, does not align precisely with expectations. It appears that coalitions with minority legislative support form cabinet committees with significantly more inter-ministerial engagement than minimal winning coalitions, which were expected to be more ‘vulnerable’ to defection and thus more likely to be broadly collegial. However, the results suggest that it may be more reasonable to consider minority coalitions as being particularly attentive to both the executive and parliamentary arenas because of their inherently tenuous status. Recent work (Bassi, Reference Bassi2017; König and Lin, Reference König and Lin2021) has shown that minority coalitions can be stable and effective equilibria. For example, König and Lin (Reference König and Lin2021, 696) show that such coalitions are more effective when they exclude the median party. Cabinet committees may be another arena in which minority coalitions constitute a distinctive puzzle that remains to be studied.

Our second dimension of cabinet committee structure, collectivity, is confronted with somewhat mixed results for the cabinet types, though the hypotheses are largely supported. The expectation that multiparty minimal winning coalitions will be less collective than single-party majorities, H2, is supported, with the estimate of a 0.75 standard deviation decrease marginally greater than its multiparty alternatives. H3 is also supported vis-à-vis collectivity: multiparty minority cabinets are significantly less collective compared to single-party majorities, but slightly more collective than minimal winning coalitions. While the multiparty oversized estimate in model (5) is not significant, its size and direction are consistent with expectations.

H5 and H6 assert that one-third measure of party composition, Effective Number of Cabinet Parties, should be associated with collegiality and collectivity: larger cabinets should be more collegial and less collective than smaller cabinets. This is not evident in the results. While the coefficient estimate for coalition size on collectivity is statistically significant in model (6), the direction runs counter to expectations; it suggests that larger cabinets are more collective, not less. The correlation between coalition size and collectivity overall is negative. It seems to be the case that, after controlling for the country fixed effects, in any given country, the relationship is somewhat positive. That is, countries which produce larger coalition sizes, such as Israel and Finland, tend to have less collective cabinets, on average, than countries with smaller coalitions (or single parties), but within countries overall the opposite is true. Since the model overall performs poorly and the results are driven by a handful of countries, we are inclined to withhold judgment on these results, for future examination.

The control variables in the models show mostly non-significant effects, unsurprising given the lack of definite expectations for the ideological variables, particularly. Neither the ideological positioning of cabinets nor their ideological divergence is shown to impact their collegiality or collectivity, on average. However, cabinet size is estimated to have a significant and relatively large substantive effect on collegiality, with one standard deviation change in cabinet size producing more than half of a standard deviation decrease. This was expected given the almost mechanical relationship between collegiality and cabinet size: the fact that as cabinets grow larger, the possible number of ties between ministers grows at a disproportional rate to any compensation through larger or more cabinet committees.

Discussion

This study theorizes a relationship between cabinet composition and collegiality and collectivity in cabinet committee systems. Collegial systems are those which induce high levels of inter-ministerial engagement; collective cabinets are those with more equal distributions of influence, rather than a more influential, core group of ministers and a large group of peripheral ministers. While we know much about how and why cabinets are formed and maintained, the contribution of this study is to systematically examine cabinet committees as an important arena of cabinet management, focusing on the key distinction between single-party and coalition contexts.

We constructed a data set of 45 cabinets in 11 countries and employed social network measures and regression models to assess six hypotheses. Our first hypothesis asserts that single-party cabinet committee systems would be more collegial and less collective than coalition committees. We found that coalitions are significantly more collegial, on average, but not significantly less collective. When we differentiated between cabinet types, we find that the collegiality effect is driven by multiparty minority cabinets, though other effects were in the expected direction. The results for collectivity reinforce the notion that cabinet type is a factor, as almost all types were significantly less collective than single-party majorities, with minimal winning coalitions and multiparty minorities most notable. We do not find robust evidence that our third measure of cabinet composition, the ‘Effective Number of Cabinet Parties’, is associated with either dimension of cabinet structure.

While the results are mixed, we find baseline support for the idea that cabinet committees, as one form of cabinet management, vary systematically because of cabinet composition. We expected that if prime ministers and party leaders are rational, they would use cabinet committees, among other tools, in a strategic way to advance their interests. We identified two goals of prime ministers and party leaders in this regard: using committees to generate trust and informational ties among governing parties, while also keeping policy influence largely confined to the smaller core of senior figures, those most responsible for maintaining cabinet stability and promoting an overall governmental interest. Our results provide some evidence that these goals are less imperative for single-party cabinets, particularly majorities.

Certainly, our work is exploratory: we seek to focus scholarly attention on the role of cabinet committees in cabinet and coalition governance. Nonetheless, the article makes three key contributions. First, it addresses the lack of scholarship concerning outcomes of government formation by directly tying the kinds of cabinets formed to specific characteristics of the cabinet decision-making process. It adds a novel answer to the question of why government formation matters. Second, it theorizes and tests hypotheses about this association using an original dataset and quantitative assessment, two aspects that have not been greatly in evidence in the cabinet government literature. The data set, which includes much more information than was used here, such as the actual committee names, chairs, ministerial portfolios, and party affiliations, should help generate future research. The quantitative and network-based approach developed here should encourage cabinet scholars to consider where insights from statistical analysis can complement or support qualitative work. Third, it makes the case for cabinet committees, specifically, to be studied more closely within and outside the coalition context. Despite their importance within the executive in many parliamentary systems, committees have largely been neglected as objects of study. Our demonstration that they can be useful windows into the consequences of government formation will hopefully drive scholars to consider how committees reflect other concerns, such as representation or policy coordination.

At the same time, we recognize that cabinet committee structure is not the only aspect of cabinet government associated with government composition, and its importance varies within and across cases. Interaction within cabinet committees is not the only arena in which ministers interact, thus the extent to which collegiality and collectivity in this arena reflects on cabinet as a whole is of further interest. Additionally, this analysis takes a structural perspective on cabinet governance: it assumes that structure significantly shapes collegial and collective behaviour. It does not account for institutional or political norms, or individual dynamics, that may impinge on or override structure. A cabinet committee structure might be shaped collegially, e.g., while actors might behave otherwise. Future research should seek to include more system-specific institutional or political variables or idiosyncratic variables at the leadership level, possibly strengthening explanations for characteristics of cabinet decision-making. It should also seek to theorize further the relationship between cabinet committees and other mechanisms of cabinet management and develop qualitative accounts of the theorized mechanisms presented here. We cannot provide definitive conclusions, but ideally this study serves as a catalyst for efforts to build our understanding of how party and coalition concerns impact the dynamics of cabinet decision-making in parliamentary systems.

Acknowledgements

I thank the anonymous reviewers of this article for their exceptionally thorough and helpful feedback, and the journal editors for their consideration.

Data Availability

All data are available from the author upon request. Data files will be published on the author’s website and provided to the journal and reviewers as requested. R code to reproduce results will be provided upon request.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773921000345.