Introduction

Depression is highly prevalent in primary care in the UK (Baker, Reference Baker2018). According to the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), depression (major depressive disorder; MDD) is diagnosed from experiencing over a period of at least 2 weeks, five or more defined criteria including sadness, lack of interest, disturbed sleep, poor concentration, sense of worthlessness and functional impairment. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is one of the first-line treatments for depression (NICE, 2018). According to the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies–Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic service user Positive Practice Guide (IAPT-BAME PPG, 2019), improving outcomes in therapy can be achieved by using cultural adaptation or cultural responsiveness. Culturally adapted therapy enhances existing therapy by adapting the language, values and techniques. Culturally responsive therapy makes adaptations in relation to evidence-based therapies and the specific culture and context of the service user. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2018) guidelines recommend being respectful and sensitive to the cultural diversities that co-present with depression. They also recommend providing comprehensive information on depression and its management when planning and implementing treatment, including how families can support the person. The IAPT-BAME PPG (2019) recommends that therapists apply flexibility in using disorder-specific models. They also advise that therapists collaboratively adapt treatment with the client. They further suggest that collaborative learning through the Kolb cycle (Kolb, Reference Kolb1984) and supervision should be used to enhance this adaptation.

Why was this adaptation needed?

The current adaptation was prompted by the client’s own request as part of her understanding of her main problem and the issues that had a bearing on this. The client’s familial issues presented as a major factor and were prominent throughout therapy. The client referred to ‘my parents’ culture’ and how ‘the needs of family come first’. In line with these references, she expressed the need for overall family support and their involvement in her therapy. This client’s own explanatory model of her cultural need was in line with the concept of familism. According to the Collins English dictionary, ‘familism’ has been defined as ‘a social structure where the needs of the family are more important and take precedence over the needs of any of the family members’. For example, studies on familism in Latino subjects show that it is considered a key cultural value necessary for building identity, sense of self-worth and close relationships with family members, especially parents (e.g. Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Cumba-Avilés, Sáez-Santiago, Beach, Wamboldt, Kaslow, Heyman, First, Underwood and Reiss2006; Falicov, Reference Falicov1998; Piña-Watson et al., Reference Piña-Watson, López, Ojeda and Rodriguez2015). Research also shows that familism can be a factor in depression (Duarté-Vélez et al., Reference Duarté-Vélez, Bernal and Bonilla2010; Campos et al., Reference Campos, Ullman, Aguilera and Dunkel-Schetter2014). Although research on familism in relation to African populations is limited, a report by Mwaura (Reference Mwaura2015) suggests that family cohesion and support systems can be important in the acquisition of identity and inclusion. Therefore, in line with these ideas, this case study responded to the client’s expressed cultural need, and the aim was to integrate familism into her CBT formulation. Prior to the study, informed consent was sought from the client in line with the Service Governance and Ethics Committee guidelines. The client was given full information on the purpose of the study and extent of confidentiality and she gave written consent for publication.

Case introduction

The case

The client was a 22-year old black African-British female referred by her GP and presenting with chronic MDD which had persisted for several years. She was employed part-time but was on sick leave for a few months. She had tried various courses of therapy with minimal improvement. The client was also prescribed 100 mg of Sertraline which she reported was not helping.

Presenting problem

At assessment, the client’s description of her main problem was consistent with MDD. She reported low mood, lack of motivation, procrastination, self-critical thought processes and hopelessness. This was impacting on her engagement at work and with family. She also reported unhelpful family attitudes and behaviours towards her symptoms and seeking mental health support.

Measures

The following measures were used. Depression symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scale, a reliable and valid diagnostic measure of depression (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001). Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment-7 (GAD-7) scale, a valid and efficient tool for GAD (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006). Functional impairment due to symptoms was assessed using the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS; Mundt et al., Reference Mundt, Marks, Shear and Greist2002). Outcomes were measured in line with the IAPT (2014) manual. The PHQ-9 scores range from 0 to 27, with a clinical caseness cut-off of 10, and a reliable change index of 6 points. The GAD-7 scores range from 0 to 21 with a clinical caseness cut-off of 8, and a reliable change index of 4 points. Recovery was defined as a score shift from above to below the clinical cut-off following therapy. Qualitative information about the therapy process was gathered using a patient experience questionnaire where the client reported what aspects of therapy were most helpful.

Assessment

A CBT assessment was conducted with the client in order to develop a shared understanding of her problems. Suicidal risk was also explored to ensure her safety. The developmental pre-disposing factors were also explored. The assessment included suitability for CBT including recognition of unhelpful cognitive and behavioural precipitating factors, and engagement issues. At assessment, the client scored severely on the PHQ-9 and moderately on the GAD-7. The client’s goals were to manage her low mood and self-critical thought processes, and to build the motivation to engage with family and go back to work.

Case formulation

The client problem was formulated with the Beck longitudinal formulation (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979). This consisted of four parts: early experiences, core beliefs, rules for living and maintenance factors. The client’s early experiences consisted of her being raised by parents who pushed for achievement and compared her with her siblings. The client reported core beliefs around being ‘not good enough’ and ‘a failure’. She reported developing rules around working hard in order to feel good enough and to please others, especially her parents. This was then maintained in her day-to-day activities where she set high benchmarks. In line with this she constantly engaged in self-critical and compare-and-despair thought processes, especially when she fell short of her own or her parents’ benchmarks. This led to procrastination and avoidance of socialising, music writing and engaging with work.

Integration of familism

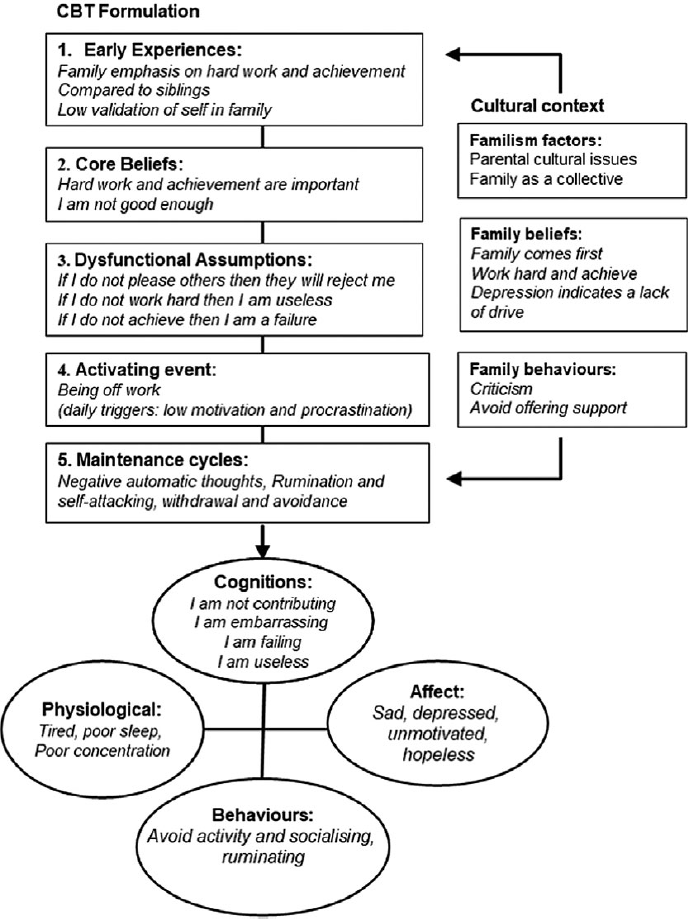

Cultural responsiveness was guided by the formulation and the client. In this adaptation, the cognitive behavioural model of the client’s thoughts, feelings and behaviours was integrated with the client’s perceived familism factors. This was achieved by her father attending the seventh session. In this integrated model the father would attend the session as head of the family and then negotiate with the rest of the family. The aim was to use factual evidence to inform the familial factors which were contributing to the maintenance of her symptoms. This culturally responsive formulation is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Culturally responsive CBT case formulation of the client’s depression [adapted from Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979) and Moorey (Reference Moorey2010)]. The cognitive behavioural model was integrated with the client’s perceived cultural domain of familism.

Course of therapy

Following assessment, the client was offered 12 sessions of individual CBT. The study was conducted by an accredited CBT therapist supervised by two accredited senior CBT therapists. At session 6 (interim review), the client did not show any reliable change as measured on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7. The client also identified her own perceived cultural factors. She reported that her parents had immigrated from Africa and had related cultural beliefs and values. She discussed her family attitudes towards her depression symptoms and seeking mental health support as main issues. She reported that in her ‘parents’ African culture’, there was a stigma attached to seeking mental health support. She also reported associated themes around family needs coming first and ‘culturally’ driven expectations to ‘contribute to the family’, ‘be successful’ and ‘portray a positive image as part of the family’. The client reported that she was currently not fulfilling these roles within the family. She also reported that therapy was not progressing because she did not have family support and requested their involvement. She identified involving her father, as the head of the family, as most helpful as he would have the authority to realign the rest of the family. The rationale was to assess family attitudes and offer psychoeducation on her symptoms. Following this, the client’s father attended the seventh session. During this session, the therapist adapted a professional and evidence-based stance. The plan was to assess his understanding and attitudes towards the problem. His explanatory model of the client’s problem was that it was due to a lack of drive. During the discussion, the father adopted a receptive curious stance. Following psychoeducation, he reported having a better understanding of depression. His new explanatory model was that depression consisted of symptoms that needed to be managed. The father also reported a better understanding of the utility of the prescribed medication, CBT and the need for family support to aid recovery. The agreed plan was that he would discuss with the wider family in order for them to decide the best ways of offering support.

The treatment plan is outlined below.

Sessions 1–2: Assessment and engagement;

Session 3: Psychoeducation and socialisation to CBT model;

Sessions 4–5: Activity-scheduling and behavioural experiments;

Sessions 6–9: Cognitive restructuring (including involvement of family member in seventh session);

Sessions 10–11: Challenging client assumptions;

Session 12: Therapy blueprint;

Three-month follow-up: Long-term effects of treatment.

Outcomes

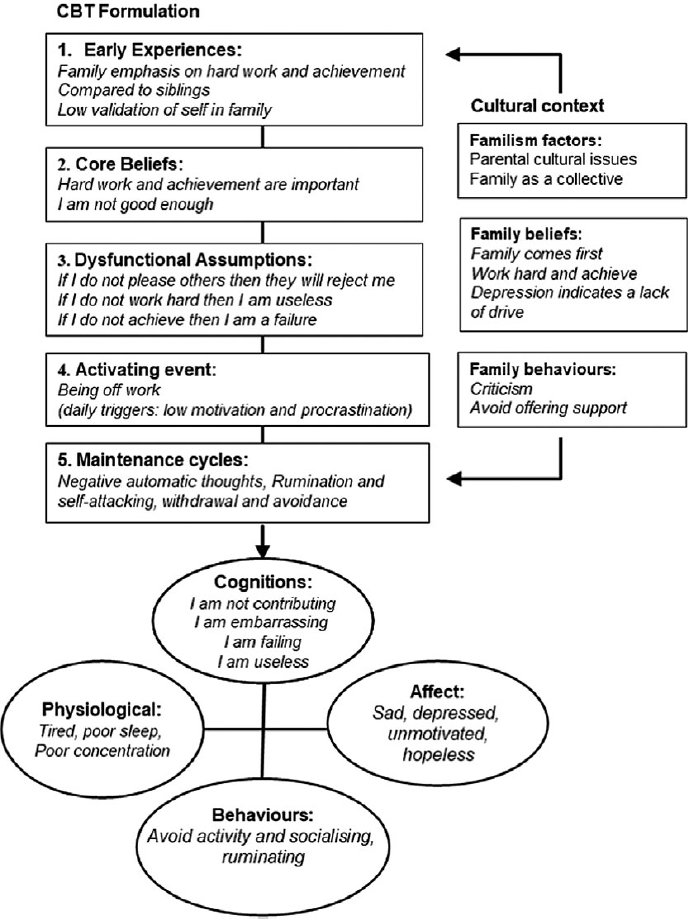

Prior to her father attending session 7, the client showed minimal change as indicated by her scores on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7. Following this session, the client attained reliable improvement (Fig. 2). By the end of therapy, the client had also returned to work. Reliable change was sustained at the end of therapy and at 3-month follow-up.

Figure 2. Client progress through therapy as shown by her scores on the PHQ-9 (![]() ) and GAD-7 (

) and GAD-7 (![]() ). The seventh session indicates when client’s father attended. The client’s scores were fluctuating between sessions 1 and 7. Only after session 7 did they dramatically and consistently improve. FU indicates the follow-up session.

). The seventh session indicates when client’s father attended. The client’s scores were fluctuating between sessions 1 and 7. Only after session 7 did they dramatically and consistently improve. FU indicates the follow-up session.

Client reported qualitative outcome

According to the client, her father attending the seventh session marked a turning point in her recovery, which correlated with a change in her family’s attitudes and behaviours towards her symptoms. She reported that the family were no longer critical of her symptoms and that they had started offering more support and encouragement. For example, the client compared that prior to attending the session her father would express disappointment at her not attending work. He now offered encouragement and helped her plan her daily activities in a graded way. She also observed a similar pattern with the rest of the family. The client reported that this validation by her family helped enhance her own self-validation, mood and motivation.

Discussion

This case study illustrates the effective adaptation of culturally responsive CBT to treat chronic depression in the context of familism. This responsive treatment plan was achieved through listening to the client’s expressed cultural needs and integrating these into her CBT formulation. Through collaboration, shared learning and use of supervision, a culturally responsive intervention was implemented. This entailed involvement of the head of the client’s family with whom the evidence base on the symptoms and interventions for depression were discussed. It is possible that receiving information from a professional was accepted in the father’s culture and he agreed to an action plan for the whole family. This led to attitude and behavioural change within the whole family, which paralleled improvement in the client’s depression symptoms. The processes of change that occurred in this intervention which involved the client’s father may be compared to those seen in couples cognitive behavioural therapy (Dugal et al., Reference Dugal, Bakhos, Bélanger and Godbout2018). This model shows some elements of change in depression symptoms. These include problem clarification, better communication, feeling supported, and reduction of conflict and criticism. It is possible that all these processes of change took place between the client and her father and further translated to the wider family. In line with her CBT formulation, this dual shift promoted her self-acceptance and ability to challenge her dysfunctional thoughts about herself, the world and future. It also led to a lift in mood, goals clarification and motivation.

The issue of culture and cultural adaptation is a complex one. For example, research suggests that stereotypical assumptions may contaminate the process of cultural adaptations if therapists pigeonhole clients and assume that all stereotypes apply to all individuals from a certain culture (Benuto and O’Donohue, Reference Benuto and O’Donohue2015). The recommendation is that therapists are mindful of this. According to Sue and Sue (Reference Sue and Sue2016), a culturally responsive therapist is constantly mindful of their own cultural biases and tries to understand the different cultural beliefs and values of their clients, Therapists also need to be mindful of diminishing from the fidelity of the evidence base during cultural adaptations of therapy. For example, Waller and Turner (Reference Waller and Turner2016) emphasised the importance of preventing therapist drift by using the formulation to guide any adaptations. They also suggested that any adaptation not guided by the model can present a barrier to therapy progress. This is also supported by research which advocates that cultural adaptation of CBT should be driven by individualised case formulations (Hinton and Patel, Reference Hinton and Patel2017; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015). In line with this, the IAPT-BAME PPG (2019) shows that cultural adaptation and responsiveness in CBT can be effectively simplified and achieved. Furthermore, Zigarelli et al. (Reference Zigarelli, Jones, Palomino and Kawamura2016) suggest that effective cultural responsiveness does not diminish from the fidelity of evidence-based treatment. Based on this evidence, the current study implemented effective cultural responsiveness by using a formulation-driven and client-led approach. In line with this, the client’s idiosyncratic factors were formulated with the Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979) model. Cultural responsiveness involved the systematic incorporation of her familism domain. Overall change was achieved from the complimentary nature of familism and the cognitive behavioural model in an additive effect. This suggests that, in line with the cognitive behavioural model, the client’s distorted view of herself, the world and the future were being maintained by familism factors. Therefore, aligning and integrating familism enhanced the effectiveness of CBT for this client.

Limitations

As with all case studies, this illustration is based on a single individual case. Therefore, these findings cannot be generalised to general populations. Furthermore, given the complexity of the subject of culture, it must be noted that this case has been presented in a simplified form with focus on this single case. Outcome measures and client-reported outcomes indicate a correlation between meaningful change and the adaptation of the client’s CBT formulation. However, other possible factors such as maturation, concomitants or spontaneous remission cannot be ruled out. Despite these limitations, the current case study illustrated the effective use of cultural responsiveness as led and evaluated by the client.

Clinical implications of this case

This case illustrates the importance of using a formulation-driven and client-led approach in the delivery of culturally responsive CBT. It also highlights familism as a cultural adaptation domain. Using this approach can be effective for the treatment of chronic depression.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and encouragement of Daniela Antonie (clinical lead) at Newham Talking Therapies. Thanks also goes to the client for her consent.

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

There are no known conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BPS. In line with this, ethical approval was sought from the East London Foundation Trust board of Ethics committee (GECSE). Client consent and data management was conducted in line with their recommendations.

Key practice points

(1) Considerations for creating a therapy environment where clients are able to define and express their cultural needs from the outset.

(2) Considerations for therapist responsiveness to a client-led integration of their perceived cultural need into CBT formulations.

(3) Considerations for familism as a cultural adaptation domain in CBT for chronic depression.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.