In memoriam Ruth Macrides (1949-2019)

Ödemiş and the Cayster valley in the Byzantine period

Ödemiş (in modern Greek “Οδɛμήσιο”, Italian “Odemisio” and in French maps “Eudémich”), second largest township of the province of Izmir, lies on a fertile plane c. 113 km southeast of Izmir, close to the Bozdağlar chain, ancient Tmolus, not far from the Küçük Menderes river, ancient Cayster (map 1). During the Byzantine period Ödemiş was located near the road linking Sardis, the capital of Lydia, converging with the coastal eastern Aegean metropoleis, i.e. Ephesus resp. Smyrna. The character of the Cayster valley is little known in Byzantine world,Footnote 1 as most of the archaeological surface structures were perhaps of kerpiç (mudbrick) and few architectural remains of marble, especially churches, were preserved. This inner Aegean landscape was always an agricultural centre with fertile water sources (especially in Palaiopolis) and therefore, Byzantine economy of the region was isolated and based on agricultural products. There were few large cities, but numerous rural minor sites, including some höyük (mound) sites. Most influential Graeco-Roman site in this part of the Cayster valley was Hypaepa (Ὕπαιπα), located c. four km northwest of Ödemiş and 56.7 km southwest of Sardis which is also mentioned in the Tabula Peutingeriana (Segment VIII 5). Hypaepa was formerly the seat of a bishopFootnote 2 and corresponds to the village of Ottoman “Dabbey” or “Datbeyi” and modern Günlüce.Footnote 3 Some other minor Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine sites in Ödemiş and the rest of the Cayster valley were Pyrgion (Birgi), Neicaea or Nicaea (between Türkönü [Ottoman “Ayasuluk”] and Kurucuova), Palaiopolis (Beydağ), Thyraea (Tire), Arcadiupolis (Arkacılar) and Coloe (Kiraz). At the end of the seventh century A.D. Ödemiş and the entire Cayster valley was assigned to the theme ThrakesionFootnote 4 that included the territory of Lydia. Thrakesion is known to have been dominated by small-scale landed property and relatively dispersed estates between the seventh and 12-13th centuries A.D.Footnote 5

Map 1: Map of the Cayster valley during the Byzantine period with the referred places in the text (underlined when possesing an archaeological museum).

During the 19th and 20th centuries several orientalists and ancient scholars visited and reported about Ödemiş and the Cayster valley which were collected by Andreas Külzer extensively.Footnote 6 Other activities in Ödemiş related to Byzantine archaeology that were not widely known in scholarly literature are as follow: First excavations were done in Ödemiş by a local Ottoman Greek from Smyrna, Demosthenes (Emmanuel) Baltazzi, before the year 1885,Footnote 7 and also the French engineer Paul Gaudin carried out some excavations in Ödemiş in 1905. In the course of the British project of the study of five Medieval castles between 1992 and 1996 one of the focus was the Cayster valley where all the project's sites are to be found, including Yılanlı Kale which lies 15 km north-east of Ödemiş.Footnote 8 Between the years 2011 and 2015 a field survey project was carried out in Hypaepa by the Yüzüncü Yıl University in Van where Byzantine evidence was barely reported. It is obvious that Hypaepa had enlarged its urban territories during the Byzantine period and survived until the 12th-13th century A.D., until the first Turkomen came to the area.Footnote 9 In recent years between 2002 and 2019 there have been several new finds in the Cayster valley in terms of Byzantine archaeology which remain as scholarly unknown: Palaiopolis is briefly excavated both by the University of Trakya in the 1990s and by the local museum of Ödemiş in 2009 where its cidatel with a Roman temple, two Byzantine basilicas and a Post-Byzantine church of 1850s were examined in detail.Footnote 10 The second and larger basilica in Palaiopolis features three phases, dating from the fifth-sixth centuries A.D., 12th-13th centuries and a later one. In the first phase of the second basilica an extensive floor mosaic with the geometric and floral decoration of the Early Byzantine period was found. Beside several other finds, a very well preserved prothesis, a naos with 35 burials as well as a diaconicon with three graves were excavated and a fragmentary inscription with the name of the city was discovered in the fill of the church.Footnote 11 A further church with an extensive mosaic floor was discovered in 2002 in Yolüstü (Ottoman “Bezdegüme”) village, c. five km east of Ödemiş where a rescue excavation was carried out by the directorship of the museum of Ödemiş in November 2012. This church measures 3 x 8 m x h. 0.65 m and dated to the fifth-sixth century A.D.Footnote 12 In 2017 the museum of Ödemiş carried out a rescue excavation in another Early Byzantine church in Ödemiş where they have discovered some architectural plastic elements.Footnote 13 Neicaea was known as a mineral deposit of minium (red lead) which was a bright orange red pigment that was widely used in the Middle Ages for the decoration of manuscripts and for painting.Footnote 14 At the acropolis of Neicaea Victor Schultze, a German church historian and archaeologist, noted an extensive basilical church in 1926Footnote 15, accidental re-discovery of which was reported by the Turkish press in 2017. During the construction of a new hospital south of the museum of Ödemiş a late antique villa complex has been discovered in October 2014.Footnote 16 In June 2012 in Potamia, c. three-four km north of modern Bademli, on the southern slope of its acropolis an olive oil workshop of Late Hellenistic-Roman period has been discovered which was transported to the garden of the museum.Footnote 17

The museum of Ödemiş and its Byzantine sigillographical collection

The local archaeological museum of Ödemiş is the fifth local museum in the Turkish province of Izmir, after Selçuk-Ephesus, Bergama, Çeşme and Tire, and the youngest one. Its collection begins officially in 1983, but its exhibition was opened in 1987, on a building site donated to the community of Ödemiş by Mr Mutahhar Şerif Başoğlu, a jurist and local collector in Ödemiş. Local finds from the Cayster valley that were previously kept in the museums of Izmir, Tire, Istanbul and Ankara were transferred to the new museum, which preserves some important Byzantine sculptural and few epigraphic material. So far only few Byzantine and Post-Medieval finds have been published from the museum of Ödemiş.Footnote 18 A large collection of Byzantine inscribed instrumenta, including, among others, bronze and lead weights as well as bronze crosses etc., were studied by E. Laflı and will be published soon. A small collection of Byzantine architectural plastic elements and epigraphic finds are being exhibited in the garden of the Çakırağa mansion in Birgi which is an offshoot section of the museum of Ödemiş.

The museum of Ödemiş possesses at least 27 Byzantine lead seals, most of which originate as acquisition to Ödemiş between 1990 and 2015. Between the years 1990 and 2015 25 lead seals were purchased from eight different salesmen: 12 seals from Mr Mehmet Özpınar, a local cobbler in Ödemiş, three seals from Mr Hasan Beden, a known numismatic collector in Izmir who deceased in 2013, each with one seal from Mr Mehmet Adnan Düzalan, a local antique dealer in Ödemiş, from Mr Mehmet Türkan, from Mr Adem Demirel, from Mr Tuncay Üstel, from Mr Hasan Gümüş, a school teacher in Ödemiş, and from Mr Celil Karakuş. Salesmen of three seals were, however, not registered in the inventory. Especially in the year of 2009 a total of 12 seals in total were purchased and inventoried by the museum.

No exact provenances of these seals are known, except no. 3 below which is supposingly found in the village of Aydoğdu that situates six km far from Kiraz, i.e. Byzantine Coloe, which is located 29 km east of Ödemiş. As the museum had originally the status of the private collection of Mr Başoğlu and had therefore a very heterogeneous assemblage, most of the acquired seals originate most likely from the Cayster valley or the other countryside inland of the eastern Aegean coast. As their measurements, state of preservations and material seem to be similar to each other, most of them came perhaps together from the same context.

At least 13 of these lead seals are currently being exhibited in the museum, i.e. nos. 1–3 and 6, and the rest are kept in the depots of the museum. No fewer than two seals were transferred to the museum through legal courses in 2016 which are kept in a specific section, and therefore excluded from our research.

Only seven seals from this collection, however, are the focus of this paper, as most of the rest are not legible, and these selected seven Byzantine seals have been treated and interpreted below sigillographically for the first time.

Catalogue of seven selected lead seals from Ödemiş

1. Imperial lead seal of Anastasius (figs. 1a-b)

Figs. 1a-b. Obv. and rev. of the imperial lead seal of Anastasius.

Acc. no. 1854 (on p. 69 in the inventory).

Provenance. Purchased on November 5, 1991 from Mr Mehmet Özpınar for 20.000 TL ($US 4.5) and inventoried on November 25, 1991.

Position. In the exhibition showcase, F2-2/13.

Measurements. Diam. 21 mm, th. 4 mm and wg. 15.7 gr.

State of preservation. The seal has breaks at the ends of the channel.

Obv. Bust of the emperor Anastasius, facing, beardless, with a crown (probably with a cross at the top) and pendilia. He wears divitision and chlamys, which is fastened in front of the right shoulder by a fibula with long cords, decorated with pearls.Footnote 19

The circular inscription is partially legible:

Transcription. [D(ominus) n(oster) A ]nasta [sius p ]erp(etuus) Aug(ustus).

Rev. Dancing winged Victoria/Nike above a globe, the head turned right, holding a laurel-wreath in both hands.Footnote 20

Dating. A.D. 491-518.

2. Monogramatic lead seal of Megas (?) stratelates (figs. 2a-b)

Figs. 2a-b. Obv. and rev. of the monogramatic lead seal of Megas (?) stratelates.

Acc. no. 1831 (on p. 44 in the inventory).

Provenance. Purchased on July 13, 1990 from Mr Mehmet Özpınar and inventoried on May 31, 1991.

Position. In the exhibition showcase, F2-2/11.

Measurements. Diam. 25 mm, th. 2 mm, h. of central My on obv. 6 mm and wg. 13.1 gr.

State of preservation. Heavy outbreaks at the ends of the channel.

Obv. Simple name-monogram with a large central My, combined with an Alpha at the bottom and probably an Epsilon at right. In the Alpha a Lambda, perhaps even Omicron and Ypsilon can be placed, and in the Epsilon also a Sigma and Gamma. Usually in monograms Iota is not written separately, and therefore it can be set in every vertical line. Perhaps there was no letter above the My where only unclear vestiges are placed. The combination  could read Μɛσσαλίου, the combination

could read Μɛσσαλίου, the combination  Εὐμαλίου, Ἀμɛλίου, Εὐλαμίου, the combination

Εὐμαλίου, Ἀμɛλίου, Εὐλαμίου, the combination  Μɛγάλου, the combination

Μɛγάλου, the combination  Μɛλιγαλᾶ. We prefer the name Megas, but that is only a preliminary hypothesis.Footnote 21

Μɛλιγαλᾶ. We prefer the name Megas, but that is only a preliminary hypothesis.Footnote 21

Rev. This damaged cross monogram presents a title or an office. In the vertical line we read  and

and  in the horizontal line probably

in the horizontal line probably  and

and  ligated with

ligated with  (sigma);Footnote 22 we should interpret the monogram as στρατηλάτου.

(sigma);Footnote 22 we should interpret the monogram as στρατηλάτου.

Translation. (Seal of) Megas(?) stratelates.

Prosopographic comments. In this time stratelates can be a high ranking military commanderFootnote 23 or only a title, yet again high ranking.

Dating. C. end of sixth-first half of the seventh century A.D.

3. Monogramatic lead seal of Ioannes anthypatos (figs. 3a-b)

Figs. 3a-b. Obv. and rev. of the monogramatic lead seal of Ioannes anthypatos.

Acc. no. 2003/2 (formerly 2812; on p. 39 in the inventory).

Provenance. Found in the village of Aydoğdu that is located six km far from Kiraz, purchased on January 16, 2003 from Mr Adem Demirel for 15.000.000 TL ($10.- US) and inventoried on July 31, 2003 by Mr Yılmaz Akkan, a staff of the museum of Ödemiş.

Position. In the exhibition showcase, F2-7/9.

Measurements. Diam. 24 mm, th. 5 mm, h. of let. 1 mm and wg. 12.2 gr.

State of preservation. The seal is struck off-centre, with small parts of the field lost. A break at the upper end of the channel.

Obv. Cruciform monogram with a name. At left  at right

at right  at the bottom Omega, at the top an Ο is visible, but the υ above is lost. This is a quite commonly attested monogram (type no. 249 of Zacos and Veglery) and should be probably read as Ἰωάννου.Footnote 24

at the bottom Omega, at the top an Ο is visible, but the υ above is lost. This is a quite commonly attested monogram (type no. 249 of Zacos and Veglery) and should be probably read as Ἰωάννου.Footnote 24

Rev. Cruciform monogram, probably representing a title or office. In the center a dominant Theta, at left a Pi, at right a Ny, but ligated with a relatively modest Tau (above the left vertical line of the Ny), at the bottom Alpha, at the top Omicron, probably together with a (lost) Ypsilon. The solution of the monogram should be ἀνθυπάτου representing the office or title of anthypatos. A similar monogram is not attested to our knowledge.

Translation. (Seal of) Ioannes anthypatos.

Prosopographic comments. Anthypatos is the translation of Latin proconsul. The province of Asia was still in this time governed by a (civil) proconsul / anthypatos. –Though anthypatos can also be a title in the seventh century A.D., in our case we prefer to interpret it as the office.Footnote 25

Comparandum. A nearly contemporary seal of a Ioannes anthypatos (only with text on both sides) was published by Zacos and Veglery.Footnote 26

Dating. Ca. first half of the seventh century A.D.

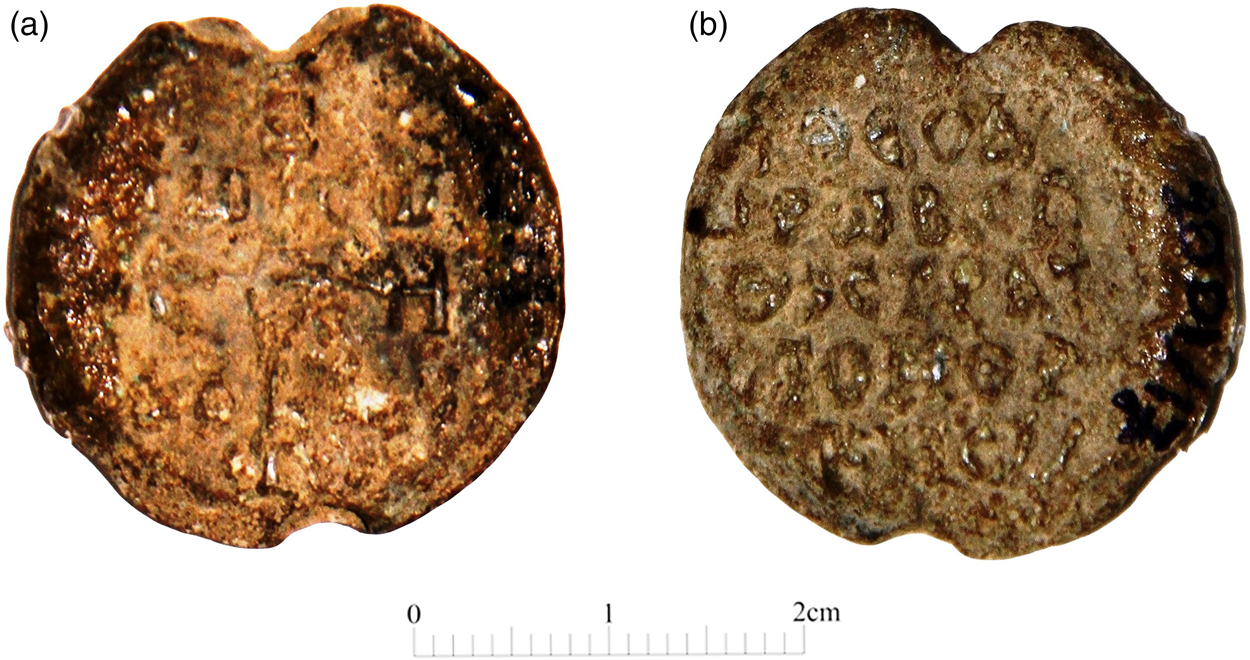

4. Lead seal of N.N., spatharios and komes kortes (figs. 4a-b)

Figs. 4a-b. Obv. and rev. of the lead seal of N.N., spatharios and komes kortes.

Acc. no. 1818.

Measurements. Diam. 26 mm, th. 4 mm; h. of let. – obv. 3 mm, – rev. 2 mm and wg. 10.9 gr.

State of preservation. The imprint is strongly off-centre and much of the upper part is lost.

Obv.

Rev.

Transcription. [Κύριɛ or Θɛοτόκɛ β]ο[ήθη] τ(ῷ) σῷ δούλῳ [ΝΝ] σπαθα(ρίῳ) (καὶ) κόμιτι κόρ(της).

Translation. Lord, help your servant N.N., spatharios and komes kortes.

Sigillographic comments. The letters are of different size; some Omicra are quite small, though the siglum for καὶ, S, is very tall. The abbreviation sign, which is an oblique line, is long. On the obv. at the beginning of the third line there seem to be traces of an H, pointing to βοήθη instead of βοήθɛι. The cross under the obv. legend is a rare phenomenon, especially when there is no further one at the end of the rev. legend.

The name of the seal's owner is completely lost – probably it was a long name; possibly the man had the title of β(ασιλικὸς) σπαθάριος.

Prosopographic comments. There are attested imperial kometes of korte, “comes of the tent”, i.e. a kind of chief of the staff; but in our case this person was a thematic “comes of the tent”, probably of Thrakesion.Footnote 27

Dating. Ca. first half of the eighth century A.D.

5. L ead seal of Theodoros, imperial spatharios and strategos of Thrakesion (figs. 5a-b)

Figs. 5a-b. Obv. and rev. of the lead seal of Theodoros, spatharios and strategos of Thrakesion.

Measurements. Diam. 28 mm, th. 4-5 mm and wg. 12.3 gr.

State of preservation. Outbreaks at the ends of the channel.

Obv. Traces of a cruciform invocative monogram, probably Laurent V, with the usual tetragram: Θɛοτόκɛ βοήθɛι τῷ σῷ δούλῳ.

The Beta of the monogram at the bottom is relatively small. At the top we assume to have a small Tau and an Omicron. At left there was probably a Kappa (including the Epsilon) and the Eta at right is clearly visible.

Rev.

Transcription. + Θɛοδώρῳ β(ασιλικῷ) σπ[α]θ(αρίῳ) (καὶ) στρατ[η]γ(ῷ) τ(ῷ)ν Θρ[ᾳ]κησ(ίων).

Translation. Mother of God, protect your servant Theodoros, imperial spatharios and strategos of Thrakesion.

Prosopographic comments. The title of (imperial) spatharios was modest for an important commander like the strategos of Thrakesion, but in the second half of the eighth and early ninth centuries A.D. there are also other similar examples for this case.Footnote 28

When the important magisterium militum per Thracias was abolished, some regiments were transferred to southwestern Anatolia. This region did not need a strong army for centuries, but after the progress of the Arab invasions around A.D. 694/695 it became necessary to defend also these provinces by a high ranking strategos; thus, this military command was called “Thrakesion”.Footnote 29

Comparanda. There are two very similar seals, one in Dumbarton OaksFootnote 30 and one in Istanbul.Footnote 31

Dating. Second half of the eighth century A.D.

6. Lead seal of Leon (?), patrikios protospatharios and strategos of Thrakesion (figs. 6a-b)

Figs. 6a-b. Obv. and rev. of the lead seal of Leon (?), patrikios protospatharios and strategos of Thrakesion.

Acc. no. 1815 (on p. 30 in the inventory).

Provenance. Purchased on July 10, 1990 from Mr Mehmet Adnan Düzalan and inventoried on May 30, 1991.

Position. In the exhibition showcase F2-2/9.

Measurements. Diam. 27 x 21 mm, th. 3 mm, h. of let. 3 mm and wg. 16.65 gr.

State of preservation. The seal is struck off-centre, the upper part, especially the first line of the rev., is nearly lost. In addition to this the lower part of the reverse is partially damaged.

Obv.: Invocative monogram of the type Laurent VIII with the usual tetragram. The ligature O-V at the top is lost, but the Rho is visible. The Beta at the bottom is very large, reaching nearly the central Theta; the two loops are not connected. This type was frequent in the later eighth century A.D.

Transcription. Κύριɛ βοήθɛι τῷ σῷ δούλῳ.

Rev.

Transcription. [+ Λέον]τ(ι)(;) πατρ[ι]κ(ίῳ) (πρωτο)σπαθ(αρίῳ) (καὶ) [σ]τρατ(ηγῷ) [τ]ῶ[ν Θ]ρᾳκ(η)[σ(ίων)].

Translation. Lord, help your servant Leon, patrikios, protospatharios and strategos of the Thrakesion.

Sigillographic and prosopographic comments. The name Leon is not sure, but the vestiges seem to point in this direction. In the fourth line there could be traces of a quite narrow Tau, in contrast to the Tau before. This person was a high ranking commander of Thrakesion; Asia and Lydia belonged to the same thema.

Comparandum. A seal in Dumbarton Oaks (acc. no. 58.106.3156)Footnote 32 offers some similarities to our type, as its rev. legend calls Leon patrikios and strategos of Thrakesion. This seal is probably elder than our one, but it is not clear if this person was the Leon patrikios and strategos of the Thrakesion who was killed in A.D. 758/759 in the Bulgarian war.Footnote 33

Dating. Late eighth century A.D.

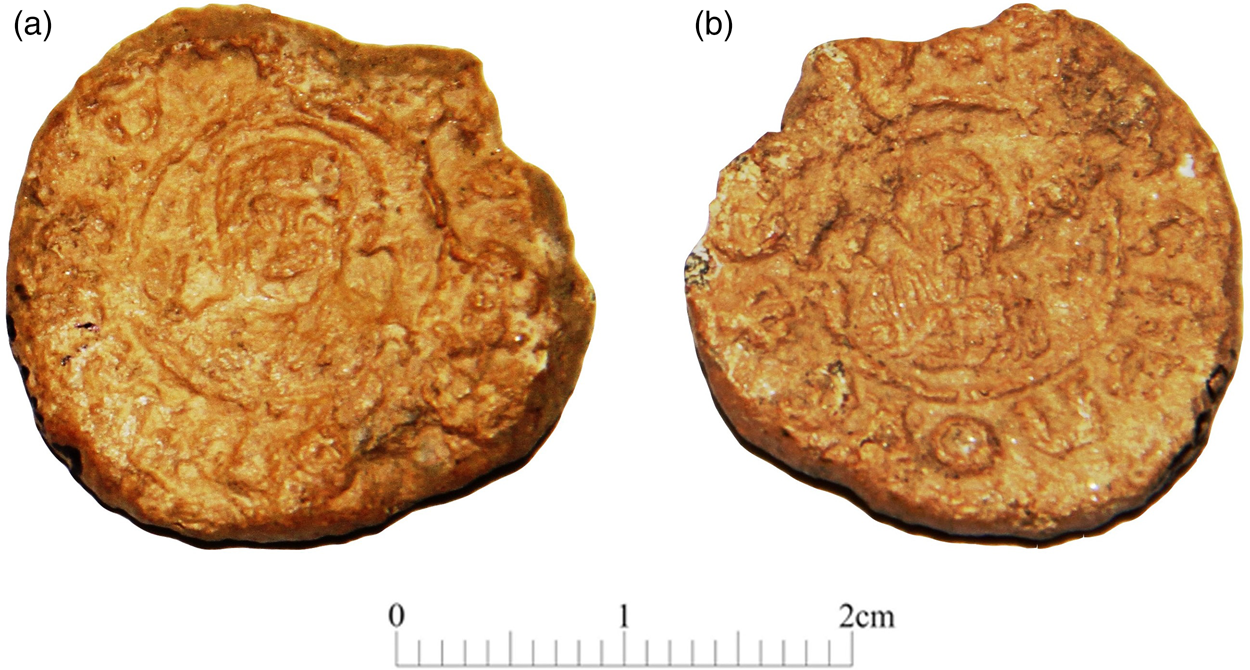

7. Lead seal of Konstantinos (?) (figs. 7a-b)

Figs. 7a-b. Obv. and rev. of the lead seal of Konstantinos (?).

Acc. no. 1882 (on p. 97 in the inventory).

Provenance. Purchased on August 27, 1992 from Mr Mehmet Özpınar for 40.000 TL ($5,80 US) and inventoried on November 24, 1992.

Position. In the exhibition showcase F2-2/14.

Measurements. Diam. 20 mm, th. 4 mm, h. of let. 3 mm and wg. 11.1 gr.

State of preservation. The surface of this seal is heavily crumbled.

Obv. In the central circle appears the bust of a virgo orans, the type of Theotokos of Blachernae (without the bust of Christ). The sigla are not visible; we therefore would prefer only  / Θ.

/ Θ.

Around the figure there was a circular inscription, beginning at the top with a cross, but not a single letter can be read with certainty; perhaps there was an invocation of the Theotokos.

Rev. In the central circle there is a male bust, probably a bearded bishop with the Gospels in his left hand whereas his name is not clear through the unclear traces of the lettres. Therefore his identification remains as unidentified.

Also here the circular inscription started at the top preceded by a small cross. Some letters seem to offer the verb σκέποις; the three letters before that, the beginning of the legend, could perhaps offer the name Konstantinos.

Transcription. It is only hypothetical:  Κω[ν(στατῖνον)] σκέποιςc ΦE..V.

Κω[ν(στατῖνον)] σκέποιςc ΦE..V.

Dating. Second half of the 11th/beginning of the 12th century A.D.

Other Byzantine lead seals and sigillographical instrumenta from the museum of Ödemiş

A further 18 Byzantine lead seals from the museum of Ödemiş which were not presented above are as follows: Acc. nos. 2001/17 (A) (formerly 2771; diam. 28 mm and th. 4 mm), 2005/13 (A) (formerly 2884; diam. 15 mm, th. 6 mm and wg. 5.9 gr), 2007/4 (M) (formerly 2932; diam. 28 mm), 2009/01 (M) (formerly 2943; diam. 13 mm; obv. a cruciform monogram, rev. inscription in five lines), 2009/03 (M) (formerly 2944; diam. 20 mm; rev. inscription in four lines), 2009/04 (M) (formerly 2945; diam. 25 mm and th. 6 mm; obv. a cruciform monogram, rev. inscription in three lines), 2009/05 (M) (formerly 2946; diam. 25 mm; obv. a cruciform monogram, rev. inscription in four lines), 2009/07 (M) (formerly 2949; diam. 19 mm and th. 6 mm; obv. a cruciform monogram, rev. inscription in three lines), 2009/08 (M) (formerly 3040; diam. 26 mm and th. 3 mm; obv. a cruciform monogram, rev. inscription in three lines), 2009/10 (M) (formerly 3041; diam. 20 mm and th. 6 mm; obv. a cruciform monogram, rev. inscription in four lines), 2009/11 (M) (formerly 3042; diam. 26 mm; obv. a cruciform monogram, rev. inscription in three lines), 2009/12 (M) (formerly 3043; diam. 17 mm; obv. a cruciform monogram, rev. inscription in three lines), 2009/13 (M) (formerly 3044; diam. 18 mm; rev. inscription in five lines), 2009/15 (M) (formerly 3046; diam. 22 mm; rev. inscription in six lines), 2009/16 (M) (formerly 3047; diam. 17 mm), 2015/61 (formerly 2015/2M; diam. 31 mm; rev. inscription in six lines), 2015/62 (diam. 23 mm) and 2015/63 (diam. 23 mm). A lead seal bearing on the obv. a winged and nude Eros standing right, legs crossed over, resting on torch sitting on altar (?) (acc. no. 2007/26, formerly 2928; diam. 19 mm, th. 2 mm and weight 3.19 gr; rev. no decoration) as well as few other earlier seals have been excluded from this study, as they belong to the Roman period.

Two last Byzantine sigillographical instrumenta in the museum of Ödemiş are the fragments of a steatite casting mould for a magical amulet and other instruments with the acc. no. 1746 (figs. 8a-9c).Footnote 34 Measurements of the plate 1 are l. 31.0 cm, w. 13.0 cm, th. 2.1 cm; and the plate 2 are l. 27.2 cm, w. 14.1 cm, th. 2.0 cm. These steatite mould plates were acquired by the museum for 40.000 TL ($US 28) on September 23, 1988 from Mr İlhami Boz and inventoried on November 1, 1991. Both of them are currently being exhibited in the showcase O2-1/1 of the museum. On the plate 1 the upper right and left bottom edges are broken and missing. Except for some scratches and little missing chips, both are very well preserved. They are fashioned from a pale greenish gray steatite or soapstone which is a talc-schist and type of metamorphic rock.

Fig. 8a. Obv. of the steatite casting mould plate 1 for a magical amulet and other instruments.

The plate 1 was a casting mould for the obv. of a magical amulet, two reliquary crosses and six other instruments forms of which were carved in linears on the stone (figs. 8a-b). The obv. of the magical amulet on this plate consists of a figure in the middle of a medallion that looks like a crudely executed head of Medusa which is surrounded by a crude inscription with  that reads (with errors) as Ἅγιος Ἅγιο(ς) Θ(ɛὸ)ς Κ(ύρι)ο(ς) Σαβαώθ. Similar inscriptions are known.Footnote 35 Its center represents probably a human head, from which serpents radiate in every direction (fig. 8b). In the study of Campbell Bonner such a type is interpreted as “uterine symbol derived from the octopus version”.Footnote 36 Though there are many such magical amulets preserved, no exact parallel is known.Footnote 37

that reads (with errors) as Ἅγιος Ἅγιο(ς) Θ(ɛὸ)ς Κ(ύρι)ο(ς) Σαβαώθ. Similar inscriptions are known.Footnote 35 Its center represents probably a human head, from which serpents radiate in every direction (fig. 8b). In the study of Campbell Bonner such a type is interpreted as “uterine symbol derived from the octopus version”.Footnote 36 Though there are many such magical amulets preserved, no exact parallel is known.Footnote 37

Fig. 8b. Obv. of the magical amulet.

The plate 2 has the reverse of the magical amulet, a cross with the inscription of  and two other instruments (fig. 9a). The amulet features four underlined lines of an horizontal inscription that reads

and two other instruments (fig. 9a). The amulet features four underlined lines of an horizontal inscription that reads  (fig. 9c). Its last line intends probably Ἀμήν, but the rest remains enigmatic. This central inscription is surrounded with another circumscription in a circular ring that reads:

(fig. 9c). Its last line intends probably Ἀμήν, but the rest remains enigmatic. This central inscription is surrounded with another circumscription in a circular ring that reads:  starting with + Κ(ύρι)ɛ βο(ή)θ(ɛι) τ(ὴ)ν δ(ούλην), but the rest is enigmatic. This amulet has perhaps some relationships to Saint Sisinnios of Parthia who was sometimes mentioned in similar contexts. Rest of the surface of these plates was polished. The back of the moulds are left unworked (fig. 9b). The dating of these plates is problematic; some similar material is assigned to the Early Byzantine period, but we would rather prefer a later period, perhaps seventh-eighth century A.D.Footnote 38

starting with + Κ(ύρι)ɛ βο(ή)θ(ɛι) τ(ὴ)ν δ(ούλην), but the rest is enigmatic. This amulet has perhaps some relationships to Saint Sisinnios of Parthia who was sometimes mentioned in similar contexts. Rest of the surface of these plates was polished. The back of the moulds are left unworked (fig. 9b). The dating of these plates is problematic; some similar material is assigned to the Early Byzantine period, but we would rather prefer a later period, perhaps seventh-eighth century A.D.Footnote 38

Figs. 9a-b. Obv. and rev. of the steatite casting mould plate 2.

Fig. 9c. Rev. of the magical amulet.

Conclusion

These seven seals range from the fifth to the eleventh/twelfth century A.D. (table 1, p. 37). The first is an imperial seal from the early fifth century; the last, probably a private seal, is from the second half of the eleventh or beginning of the twelfth century. All the others stem from the seventh or eighth century, with a clear majority of military personalities, whereas there is only one civil governor present. As these seals were most probably found in the Cayster valley they point to a certain importance of this fertile region, as an agricultural and commercial source and route for Byzantine Ephesus, Smyrna, Sardis and Constantinople.

Table 1: Byzantine sigillographical evidence from the museum of Ödemiş.

Notes and acknowledgements

Some abbreviations in alphabetic order: acc. no.: accession number; diam.: diameter; h.: height; h. of let.: height of letters; l.: length; obv.: obverse; p.: page; rev.: reverse; th.: thickness; w.: width; and wg.: weight.

This collection was studied with an authorization granted by the directorship of the museum of Ödemiş on September 22, 2011 and enumerated as B16.0.KVM.4.35.74.00-155.01/555. The necessary documentation was assembled on November 18, 2011. The map was prepared by Dr Sami Patacı (Ardahan) in 2017 who also took the photographs in 2011, whom we would like to express our gratitude. The former director of the museum of Ödemiş, Mrs Sevda Çetin, the new director of the museum, Mrs Feride Kat and the former curator of this collection, Mrs Ayşen Gürsel assisted us on several issues and we would like to thank them sincerely. We also would like to thank Dr Gülseren Kan Şahin (Sinop) for improving our figures, Dr Paweł E. Nowakowski (Warsaw) for some references and the editors as well as anonymous peer reviewers of the BMGS, especially Professor John Haldon (Princeton, NJ) for making various comments and suggestions.