The formation of a new cabinet involves many decisions: Which parties form the cabinet? Which parties and individuals get to control which ministry? And what policy program does the cabinet agree upon? While these questions have been at the centre of scholarly attention for decades (for reviews see, for example, Laver Reference Laver1998; Laver and Schofield Reference Laver and Schofield1990; Müller Reference Müller, Landmann and Robinson2009), another crucial decision has been largely overlooked by political science research: How are government ministries designed – that is, which ministries and office holders are in charge of what policy areas? While coalition researchers usually treat ministries as exogenous payoffs to be distributed, this article casts serious doubt on this assumption by showing that the makeup of ministries is often reformed in the context of coalition formation.

A few examples illustrate that the design of government portfolios is sometimes changed drastically. In 2016, the incoming British Prime Minister Theresa May created a new Department for Exiting the European Union charged with managing the Brexit process. In 2010, the Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orbán reduced the number of ministries from fourteen to eight by creating some ministries with extensive jurisdictions, for example a Department of Finance and Economics. Below the level of such comprehensive reforms involving the creation and termination of entire ministries, individual competencies are frequently shifted between existing ministries. For example, the jurisdictions for energy, consumer protection, urban development and digital infrastructure were reassigned to new ministries at the beginning of the third German cabinet headed by Angela Merkel in 2013.

This article introduces a comparative research project that systematically studies such reforms of portfolio design across nine Western European democracies. We define portfolio design as the distribution of competencies among government ministries and office holders (that is, ministers and junior ministers). We argue that such reforms are substantively relevant phenomena that should affect policy making and policy outputs, and are theoretically important for various strands of political science research, most importantly the literatures on deliberate institutional design and coalition research. We discuss the scarce existing literature and argue that a systematic study of portfolio design should take a comparative approach without neglecting the in-depth expertise of individual countries.

Towards this end, we introduce a new comparative dataset covering portfolio design changes in nine Western European democracies from 1970 until 2015. Based on these data, the article investigates two fundamental research questions. First, how frequent are changes in portfolio design, and thus how realistic is the assumption of ministries as exogenous payoffs that is central for the literature on portfolio allocation (for example, Bäck, Debus and Dumont Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011; Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996, 49)? Secondly, can political events related to changes in the government explain the timing of portfolio design reforms, which would suggest that such reforms are an integral part of the government formation process? Our empirical analysis first demonstrates that these reforms occur frequently, on average roughly once a year. Furthermore, changes in portfolio design are much more likely after adjustments in the party composition of the cabinet and the prime minister, whereas changes in the cabinet's ideological position or the relative size of cabinet parties yield only weak additional effects. These findings suggest that portfolio design is indeed driven by a political logic and can be considered a distinct strategy that government parties employ to adapt the distribution of competencies to their advantage. We discuss several implications of these findings for the literatures on institutional design and coalitions in the concluding section.

Why study portfolio design?

Thus far, the design of cabinet portfolios has received little scholarly attention. This omission is surprising given the central role that ministries play in modern democracies. In this section, we outline three reasons for studying the politics of portfolio design: (1) the substantive importance of ministries in policy making, (2) the theoretical relevance of deliberate institutional reform as a strategy of political actors and (3) the theoretical and methodological relevance of the changes in portfolio design for the study of coalition politics.

First, portfolio design should affect government policy because ministries play a dominant role in the policy-making process. Ministries enjoy ample leeway in the drafting stage of new legislation and its subsequent implementation (for example, Andeweg Reference Andeweg2000; Huber and Shipan Reference Huber and Shipan2002; Knill and Tosun Reference Knill and Tosun2012; Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1994; Peters Reference Peters2010; Schnapp Reference Schnapp2004). Even though individual ministries are constrained (to varying degrees) by collective decision making in the cabinet and central coordination by the prime minister (Dahlström, Peters and Pierre Reference Dahlström, Peters and Pierre2011; Peters, Rhodes and Wright Reference Peters, Rhodes and Wright2000; Rhodes and Dunleavy Reference Rhodes and Dunleavy1995), there is little doubt that ministries have a crucial impact on everyday decisions and enjoy disproportionate influence on major policy decisions within their jurisdiction (Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1994; Müller Reference Müller, Laver and Shepsle1994). Accordingly, changes in the design of portfolios, especially the reallocation of jurisdictions from one ministry to another, should affect policy making.

This effect is independent of what position one takes on the much-disputed question of the extent to which the political leadership (that is, the minister) is able to steer policy within her department. If minsters are strong, they can put their own stamp on policy decisions so that changes in portfolio design should affect policy making due to the impact of individual ministers, especially if jurisdictions are shifted between ministries controlled by different parties. If, however, policy making is dominated by the ministerial bureaucracy, differences in the preferences of bureaucrats, established links to policy networks and interest groups, as well as ministry-specific ways of framing problems and possible solutions should lead bureaucrats in different ministries to perceive and address policy problems differently (for example, Sabatier and Weible Reference Sabatier, Weible and Sabatier2007; Scharpf Reference Scharpf1997, 39–40; Smeddinck and Tils Reference Smeddinck and Tils2002, 262–66). This effect should be particularly visible if policy decisions must balance conflicting goals. For example, energy policy involves a fundamental trade-off between economic prerogatives and environmental concerns. It is plausible to expect this trade-off to be addressed differently depending on whether energy policy is drafted in a Ministry of Economics or a Ministry of the Environment.

Beyond the expected policy impact, changes in portfolio design are often symbolic political events that are used to signal the government's specific issue emphasis (Derlien Reference Derlien1996; Mortensen and Green-Pedersen Reference Mortensen and Green-Pedersen2015). Examples include the creation of super-ministries such as the Ministry for Economics and Labour in Germany in 2002, the creation of the Department for Exiting the European Union (‘Ministry for Brexit’) in Britain in 2016, and the establishment of environmental ministries in many countries in the 1980s. Both the influence of ministries on policy making and the political signalling effect make reforms of portfolio design substantively relevant phenomena.

Secondly, reforms of portfolio design constitute a distinct, but thus far largely ignored, strategy that political actors can use to pursue their substantive interests. Rational choice institutionalist research, in particular, claims that actors reform institutional rules if they expect a different institutional setup to be more suitable for reaching their substantive goals (for example, Diermeier and Krehbiel Reference Diermeier and Krehbiel2003; Ostrom Reference Ostrom2005; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1990, chap. 4). Empirical research has found support for this claim in the design of electoral systems (for example, Benoit Reference Benoit2004; Benoit Reference Benoit2007; Gallagher and Mitchell Reference Gallagher and Mitchell2005; Renwick Reference Renwick2011; Vowles Reference Vowles1995), parliamentary organization (for example, André, Depauw and Martin Reference André, Depauw and Martin2016; Binder Reference Binder1996; Dion Reference Dion1997; Schickler Reference Schickler2000; Sieberer and Müller Reference Sieberer and Müller2015; Zubek Reference Zubek2015) and political regime types (Cheibub Reference Cheibub2007; Przeworski Reference Przeworski and Mainwaring1992). Surprisingly, however, very little empirical research has explored the internal organization of the executive branch by testing whether these theoretical arguments also apply to the distribution of competencies between ministries. Given the substantive importance of ministries, this question is essential for a general understanding of institutional reform as a deliberate strategy of political actors in parliamentary democracies.

Thirdly, portfolio design is directly relevant to the study of coalition politics because it challenges the standard assumption that ministries are exogenous payoffs to be distributed in coalition formation, and because it points to an additional mechanism of mutual control within the cabinet. Coalition research treats ministerial positions as key payoffs in the coalition formation game, either for the office benefits they entail or for the influence they exert over policy (Druckman and Warwick Reference Druckman and Warwick2005; Laver and Schofield Reference Laver and Schofield1990; Raabe and Linhart Reference Raabe and Linhart2014). Thus, an established strand of research analyses how many ministries are allocated to individual coalition partners, as well as which ministries are assigned to which party (for example, Bäck, Debus and Dumont Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011; Carroll and Cox Reference Carroll and Cox2007; Ecker, Meyer and Müller Reference Ecker, Meyer and Müller2015; Falcó-Gimeno and Indridason Reference Falcó-Gimeno and Indridason2013; Laver Reference Laver1998; Laver and Schofield Reference Laver and Schofield1990; Raabe and Linhart Reference Raabe and Linhart2015; Verzichelli Reference Verzichelli, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008; Warwick and Druckman Reference Warwick and Druckman2006).

This research usually assumes (often implicitly) that portfolios are fixed and that their design is exogenous to the allocation process. One justification for this assumption is the need to hold some aspects constant in order to increase the traceability of the assignment process, especially for modelling purposes (Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996, 49–50). While this argument is methodologically valid, it can be problematic if political actors frequently and deliberately alter the makeup of ministries in the allocation process. This would suggest that the design of government portfolios is an essential element of the government formation process that deserves explanation. Previously available data and the new empirical evidence we present below indicate that this may well be the case.

Moving beyond the allocation process, the design of cabinet portfolios can also contribute to the literature on coalition governance in three ways (for example, Carroll and Cox Reference Carroll and Cox2012; Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2011; Strøm, Müller and Bergman Reference Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008; Thies Reference Thies2001). First, the allocation of related jurisdictions to various ministries controlled by different parties can be conceptualized as an additional mechanism through which coalition partners control each other and reign in ministers from other parties (Saalfeld and Schamburek Reference Saalfeld, Schamburek, Raunio and Nurmi2014). Secondly, portfolio design can be used to strengthen the prime minister's position by creating parallel structures in his or her office to oversee policy making within ministries (Fleischer Reference Fleischer, Dahlström, Peters and Pierre2011) or by allocating jurisdictions to specific ministers in order to reduce preference heterogeneity and thus the danger of agency loss (Dewan and Hortala-Vallve Reference Dewan and Hortala-Vallve2011). Thirdly, portfolio design also matters for the analysis of individual ministerial careers because prime ministers and other government leaders (for example, leaders of smaller coalition partners) can remove or grant competencies as a means of punishing or rewarding individual ministers (Indridason and Kam Reference Indridason and Kam2008).

Conceptualizing and measuring portfolio design

Despite its substantive and theoretical importance, the politics of portfolio design is largely uncharted territory. Prior studies have mainly focused on the number of ministries as a rough indicator of portfolio design, in both comparative analyses (Davis et al. Reference Davis1999; Indridason and Bowler Reference Indridason and Bowler2014; Verzichelli Reference Verzichelli, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008) and single-country studies (for Denmark: Mortensen and Green-Pedersen Reference Mortensen and Green-Pedersen2015; for Germany: Derlien Reference Derlien1996; Lehnguth and Vogelgesang Reference Lehnguth and Vogelgesang1988; Saalfeld and Schamburek Reference Saalfeld, Schamburek, Raunio and Nurmi2014; for the UK: Heppell Reference Heppell2011; Kavanagh and Richards Reference Kavanagh and Richards2001; Pollitt Reference Pollitt1984; White and Dunleavy Reference White and Dunleavy2010). These studies show that cabinet size varies enormously both between countries and over time. A brief look at a sample of twenty-nine European democracies since 1945 (or the date of democratization, if later) shows that in an average country, the number of ministers in the largest cabinet was almost 80 per cent higher than in the smallest one. In nineteen of twenty-nine countries, the difference was at least 50 per cent; in seven it was 100 per cent or more. These differences stem from frequent changes in cabinet size: Only 37 per cent of all cabinets in this sample contain the same number of ministers as the previous one, whereas 28 (34) per cent witness a decrease (increase) in cabinet size.Footnote 1

However, changes in cabinet size are only the tip of the iceberg; they mask frequent shifts in jurisdictions between established ministries. Such changes have so far only been documented in a limited number of single-country studies. A study of Britain finds that 125 government departments were involved in reconfigurations from 1950 to 2009, while the net change in the number of ministries was much smaller (White and Dunleavy Reference White and Dunleavy2010, Figure 6). In Germany, thirty-eight reforms of portfolio design between 1957 and 2015 affected 147 ministries. Of those changes, only a small minority involved the creation (six) or termination (thirteen) of a ministry, whereas 128 were jurisdictional shifts between established ministries (Sieberer Reference Sieberer2015).

Such single-country studies have obvious merits for understanding the country analysed and can dig much deeper with regard to data collection and context-specific explanations. However, they are inherently limited with regard to their generalizability and compatibility with existing comparative work (especially in the area of coalition research). Furthermore, single-country studies cannot assess the impact of institutional factors that are stable within countries such as second-order rules on how portfolio design can be reformed, the prevailing cabinet format, or the power of prime ministers and heads of state in government formation (Amorim Neto and Strøm Reference Amorim Neto and Strøm2006; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009; Strøm, Müller and Bergman Reference Strøm, Müller and Bergman2003). To alleviate these problems, we outline a cross-national design below that allows us to go beyond single countries while remaining attentive to crucial country-specific peculiarities with regard to data collection. Before we do this, the next section develops theoretical expectations on the conditions under which reforms of portfolio design should occur.

Explaining changes in portfolio design

The core theoretical claim of this article is that portfolio design reforms are driven by a ‘political logic’ – that is, that parties and politicians change the design of government portfolios according to their political preferences.Footnote 2 One way to test this core expectation is to study the timing of reforms.Footnote 3 If portfolio design is changed for political reasons, reforms should cluster temporally after events that change the preference constellation among the relevant political actors. Changes in the cabinet are the most important events in this respect. However, cabinets can change in various ways. By distinguishing between different types of changes, we can go beyond the simple expectation that the preference constellation in the cabinet matters for portfolio design reforms and identify which changes are decisive.

For this purpose, our analysis focuses on four events: a change in party composition, a change in the person of the prime minister, a change in cabinet ideology and a change in the partisan fragmentation of the cabinet. The first two affect cabinets on a very fundamental level by exchanging at least some of the relevant actors. Thus, they are the most likely to trigger reforms. In contrast, changes in cabinet ideology and the partisan fragmentation of the cabinet provide a gradual measure of the magnitude of changes in the cabinet. At the same time, these two measures are largely contingent on changes in the cabinet's party composition – that is, they are usually stable in the absence of changes in cabinet composition.Footnote 4 Thus, these variables allow us to test whether the magnitude of changes in the cabinet yields any additional effect on portfolio design reform beyond the fact that the cabinet changes at all. In the empirical analysis, we address the dependence between the different change measures by estimating models for single events as well as a joint model. Our hypotheses address each potential event in turn.

First, changes in the cabinet's party composition should make portfolio design reforms more likely. New cabinet parties may want to structure government portfolios differently than their predecessors to reflect changes in the government's policy priorities, for example by creating independent departments for policy areas that are high on the government's issue agenda (Mortensen and Green-Pedersen Reference Mortensen and Green-Pedersen2015). Thus we expect:

Hypothesis 1

Changes in portfolio design become more likely when the party composition of the government changes.

Secondly, a change to a new prime minister constitutes a key event for any cabinet because the preferences and personality of prime ministers have a strong substantive and symbolic impact on their cabinets.Footnote 5 For example, prime ministers often differ in their leadership style and the way they solve conflicts within the cabinet (Helms Reference Helms2005; Poguntke and Webb Reference Poguntke and Webb2005; Timmermans Reference Timmermans2003). Therefore, a new prime minister could aim to change portfolio design as an aspect of coalition governance to his or her liking. This argument is particularly strong in countries like Germany, where portfolio design is the prerogative of the head of government. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

Changes in portfolio design become more likely when the prime minister changes.

Hypotheses 1 and 2 focus on changes in the cabinet's composition. In the following, we analyse two factors that go beyond binary reform measures to capture the magnitude of change that takes place. For one, changes in portfolio design could depend on the ideological differences between the current cabinet and its predecessor (Dahlström and Holmgren Reference Dahlström and Holmgren2019). Ideological shifts between cabinets are often associated with changes in the issue positions and priorities of the cabinet parties. Parties might thus feel the need to change the design of government portfolios in ways that reflect these new priorities. For example, the new Danish centre-right coalition government in 2001 established an independent Ministry for Refugees, Immigrants and Integration and stripped down the competencies of the Environment and Energy Department (for example, moving ‘energy’ to the Economics Department). Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

Changes in portfolio design become more likely when the ideological position of the cabinet changes.

Moreover, changes in the relative size of parties within the cabinet could have an additional effect on portfolio design. Ample research shows that party size is a crucial predictor of the distribution of office and policy payoffs within coalitions (for example, Bäck, Debus and Dumont Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011; Warwick and Druckman Reference Warwick and Druckman2006). Beyond a strong orientation towards proportionality, several studies show that small parties are slightly overpaid with regard to the number of portfolios (Browne and Franklin Reference Browne and Franklin1973; Warwick and Druckman Reference Warwick and Druckman2006). One way to allocate more offices to small parties is to adapt portfolio design, for example by splitting ministries or moving policy jurisdictions to ministries controlled by small parties (Sieberer Reference Sieberer2015). Changes in the relative sizes of cabinet parties can be measured via the partisan fragmentation within the cabinet, leading to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4

Changes in portfolio design become more likely when the fragmentation in the cabinet changes.

Studying portfolio design comparatively

In this section, we outline our approach to studying portfolio design comparatively across nine Western European democracies. While our conceptual definition of portfolio design and its reform is quite straightforward, measuring it empirically is a rather complex task that requires in-depth field knowledge to gather and correctly code the relevant information. First, the power to determine portfolio design is granted to different actors – the head of state in some countries, the head of government in others, and the legislature via lawmaking in yet others. Secondly, in many instances the documents outlining portfolio design are not readily available but have to be identified via archival work, especially for earlier periods. Thirdly, reforms include both substantive changes and minuscule administrative or purely technical changes (such as correcting typos) that are not always easy to distinguish. Finally, some ministerial jurisdictions are country-specific; their relevance is hard to judge without in-depth knowledge of the respective political system.

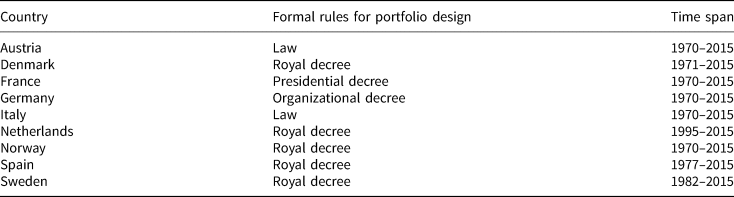

To deal with these challenges, we collected data in a decentralized way as a team of country experts based on joint coding instructions. This strategy achieves an optimal balance between country-specific expertise and conceptual coherence. We analyse portfolio design reforms in nine West European countries over up to forty-five years (from 1 January 1970 to 31 December 2015): Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain and Sweden (see Table 1). This set of countries provides substantial variation in institutional setup and party system characteristics, for example, regarding the power and role of prime ministers (Strøm, Müller and Bergman Reference Strøm, Müller and Bergman2003), formal powers of heads of state (Amorim Neto and Strøm Reference Amorim Neto and Strøm2006), the government formation process (Laver and Schofield Reference Laver and Schofield1990, 210), the types of governments that are formed (Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm2000) and the format of the party system (Mair Reference Mair, LeDuc, Niemi and Norris2002).

Table 1. Countries, sources for changes in portfolio design, and time span

Note: in Spain, data collection starts with transition to democracy. In Sweden and the Netherlands, the relevant documents to code portfolio design are not readily accessible before 1982 and 1995, respectively.

We code changes in portfolio design as instances in which the distribution of competencies among departments (ministries) changes or the distribution of competencies among office holders (ministers and junior ministers) is modified. Thus, mere cabinet reshuffles without an alteration of policy responsibilities are excluded. By contrast, changes in the number of departments and/or office holders do constitute a change in portfolio design because new or discarded offices and/or office holders gain or lose competencies, respectively. In addition, moving officeholders (most notably junior ministers) with fixed competencies between departments also counts as a change in portfolio design. As Table 1 indicates, the formal rules in which portfolio design is codified, and thus the data sources for our coding, vary across countries. The empirical analysis below controls for these differences.

Based on these data sources, the country experts identified all changes in portfolio design during the period of investigation and provided a short description of the reform (Which departments were involved? Which competencies were affected?). In a second step, we excluded purely technical reforms and instances with no (or very minor) changes in policy jurisdictions. Moreover, consecutive changes within a few days that were clearly part of a single process are treated as one reform and dated with the earliest available date to capture the starting point of the reform process.Footnote 6 In total, we identified 339 changes in portfolio design in our sample.Footnote 7 In Appendix A, we describe three randomly selected reforms from our dataset in greater detail, showing that these changes were substantial and had the potential to affect policy processes and outcomes.

Empirical results

This section presents the empirical results on the frequency and timing of portfolio design reforms. It shows that the ‘fixed structure’ assumption – that ministerial portfolios are exogenously designed – is often violated.Footnote 8 Furthermore, the timing of reforms suggests that political motives play a major role. More specifically, we find that changes in portfolio design are much more likely after changes in the party composition of the cabinet (Hypothesis 1) and the identity of the prime minister (Hypothesis 2), whereas changes in the cabinet's ideological position (Hypothesis 3) and its fragmentation (Hypothesis 4) have only weak additional effects.

The Frequency of Changes in Portfolio Design

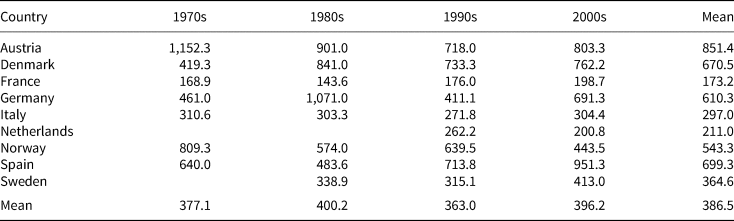

Table 2 shows the average time (in days) that a given portfolio design is in place across countries and over time. The data indicate that the distribution of competencies between departments or office holders changes frequently: on average, the portfolio design is changed about once a year (mean duration: 387 days). Yet the frequency varies substantially across countries. Reforms occur most often in France, where a given design changes (on average) about twice a year (mean duration: 173 days), and the Netherlands (mean duration: 211 days). By contrast, changes are least frequent in Austria, where portfolio designs are (on average) in place for more than two years (mean duration: 851 days).

Table 2. Mean duration (in days) between changes in portfolio design

Note: reforms from 2011 to 2015 are grouped into the ‘2000s’ category.

This cross-country variation does not seem to be linked to the second-order rules of how portfolio design is changed. In Austria and Italy, changes in the competencies between different departments are regulated by law, which requires approval by a parliamentary majority and thus arguably involves more veto players than in countries where reforms are possible via decrees.Footnote 9 However, the two countries differ markedly with regard to reform frequency. While portfolio design is rather stable in Austria, it changes frequently in Italy. Moreover, there is substantial variation across countries that use decrees to change the competencies between different departments and office holders.

There is also no clear time trend in our data beyond some country-specific patterns. Changes in portfolio design become more likely over time in Austria and, to a lesser extent, in Norway, whereas reforms in Denmark were more frequent in the 1970s than today. Yet, by and large we see no clear temporal trends that are worth noting.

Explaining the Timing of Changes in Portfolio Design

This section employs event history analysis to test our hypotheses on the timing of reforms. We use Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the ‘hazard rate’, that is, ‘the instantaneous probability that an event occurs given that the event has not yet occurred’ (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones Reference Box-Steffensmeier and Jones1997, 1427). In our context, the hazard rate describes the probability that the portfolio design currently in place will be reformed at a specific point in time depending on various covariates, most notably the occurrence of the four events identified above. As these events can occur at different times during a given portfolio design, they are modelled as time-variant covariates. At the beginning of each observation (that is, day 1 of a new portfolio design), the variables for all four events are coded 0. After an event (for example, a change in prime minister) occurred, the respective variable takes a value of 1 (for dichotomous variables) or the value of the magnitude of the change (for continuous variables).

To test Hypotheses 1 and 2, we use two dichotomous variables that indicate changes in the cabinet's party composition (Hypothesis 1) and the prime ministership (Hypothesis 2). To measure changes in the cabinet's policy position (Hypothesis 3), we calculate the position of each cabinet as the seat share-weighted average of cabinet parties' left–right positions as measured by expert surveys (on a 0–10 scale) and then use the absolute difference between the positions of the current cabinet and its predecessor. To measure the change in fragmentation within the cabinet (Hypothesis 4), we use the absolute difference in the effective number of cabinet parties from the previous to the current cabinet (Laakso and Taagepera Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979). The data on these four variables are taken from the ParlGov database (Döring and Manow Reference Döring and Manow2018).

Beyond these key variables used to test our hypotheses, we also include a time-varying covariate that captures the occurrence of general elections. Elections are key turning points for parties to change their issue positions and issue emphasis (Walgrave and Nuytemans Reference Walgrave and Nuytemans2009), which could also trigger portfolio design reforms. Election dates for legislative and (in France) presidential elections are taken from the Parline database of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (https://www.ipu.org) and various national data archives.

Furthermore, we include control variables that identify caretaker cabinets, coalition cabinets, the formal rules for changing portfolio design, changes in economic conditions and the time period. Caretaker cabinets usually expect only a short tenure in office, and could thus have a lower probability of portfolio design changes. By contrast, reforms should be more frequent under coalitions compared to single-party cabinets because the political logic outlined above suggests that parties use portfolio design to divide policy jurisdictions among the coalition partners. Data for both variables are taken from the ParlGov database. Thirdly, changes in portfolio design could be less likely in countries where such reforms require laws (1) rather than decrees (0) because the need for parliamentary approval arguably involves more veto players. Fourthly, we account for annual changes in the unemployment rate using data from the Quality of Government dataset (Teorell et al. Reference Teorell2018). Increasing unemployment may point to poor performance of the current institutional setup and could trigger changes in portfolio design. Finally, we include dummy variables for decades to test whether portfolio design reforms have become more frequent over time.Footnote 10 Overall, we have data on 327 portfolio designs.Footnote 11

We test our hypotheses using Cox proportional hazard models. As the four events we are interested in are empirically related, we first estimate separate models for each event before turning to a full model with all four. Statistical tests show that the crucial model assumption of proportional hazards is violated in all model specifications (Grambsch and Therneau Reference Grambsch and Therneau1994); Harrell's rho tests (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones Reference Box-Steffensmeier and Jones2004, 135) are used to identify the variables causing this violation. In each specification, the relevant variables are interacted with (the log of) time (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones Reference Box-Steffensmeier and Jones2004, 136–37). Additional robustness tests that include country-fixed effects to address any remaining country-specific variation yield equivalent results (see Appendix B).

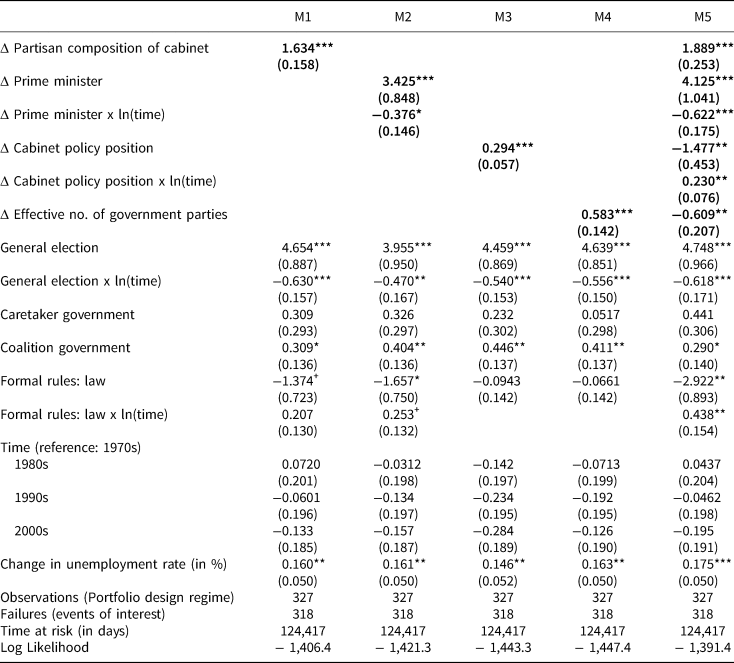

Table 3 shows the regression results for the five model specifications. Models 1 to 4 test our four hypotheses separately, whereas Model 5 includes all variables of interest. Positive coefficients indicate an increase in the hazard rate, and thus a higher likelihood of a portfolio design change.

Table 3. Analysing the timing of changes in portfolio design

Note: standard errors in parentheses. + p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Models 1 to 4 support all four hypotheses when tested in isolation: all events have a statistically significant positive effect on changes in portfolio design. Yet, hypotheses on the magnitude of change (Hypotheses 3 and 4) are largely contingent on changes in the cabinet's party composition (Hypothesis 1). The full Model 5 accounts for this interdependence by including all four events in a joint model. The results indicate that two event types are dominant: changes in party composition (Hypothesis 1) and changes in the person of the prime minister (Hypothesis 2) both have statistically significant and strong positive effects. The negative interaction term with time indicates that the positive effect of a change in prime minister on the hazard rate diminishes over time – that is, new prime ministers mainly implement portfolio design reforms early in their tenure. In contrast, we find little evidence of additional effects of changes in the cabinet's ideological position (Hypothesis 3) or in its fragmentation (Hypothesis 4). Against our hypotheses, the coefficients of both variables are negative and statistically significant; however, as we show below, they are substantively weak.

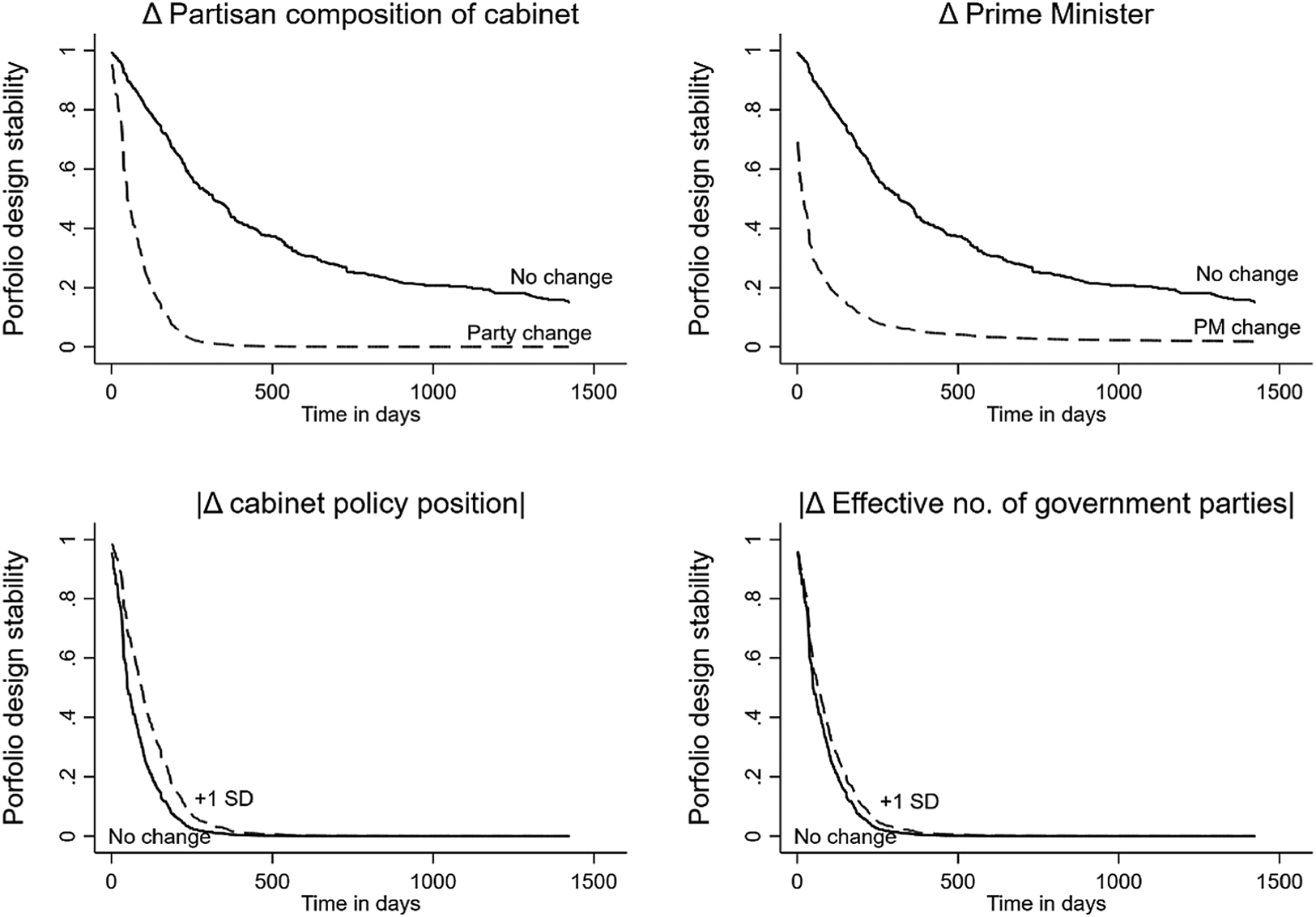

To interpret these effects in a more meaningful way, we simulate and plot survival functions based on the results of the full model for different analytically meaningful scenarios (Ruhe Reference Ruhe2016).Footnote 12 Putting the remaining covariates at their means (continuous variables) and modes (categorical variables),Footnote 13 the graphs in Figure 1 show the probability that a given portfolio design will remain in place (‘survive') over time depending on the values of our key covariates. The dashed lines indicate the probability of portfolio design stability in the aftermath of the four simulated events. The solid lines indicate survival functions if the respective event had not occurred.Footnote 14

Figure 1. Predicted stability of portfolio designs

Note: all estimates are based on Model 5 in Table 3, while the remaining covariates are held constant at their mean or mode, respectively. For the (changes in) continuous variables, curves show the stability for ‘no change’ (zero; roughly the mean) and an increase by one standard deviation. Plots based on the scurve_tvc command by Ruhe (Reference Ruhe2016).

Figure 1 shows that a reform of portfolio design is much more likely after a change in the government's party composition (Hypothesis 1; upper left panel in Figure 1). According to the simulation, only about 1 per cent of the portfolio designs are still in place one year after a change in the party composition, while without such a change about 46 per cent of portfolio designs remain unchanged. A similar pattern emerges for Hypothesis 2 in the upper right panel of Figure 1. When a new prime minister enters office, the chances that a given portfolio design will remain in place decrease dramatically. One year after the event, only about 6 per cent of the portfolio designs are still unchanged (compared to 46 per cent without a change in the identity of the prime minister).

According to the model, both variables have very strong effects: it is almost certain that the portfolio design will be reformed within one year after changes in the cabinet's party composition or the prime ministership. However, this result is in line with previous research. Verzichelli (Reference Verzichelli, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008) finds that only about one-third of all cabinets have the same number of ministers as their predecessors. This measure underestimates changes in policy responsibilities because it only captures net changes (for example, it ignores reforms that create and abolish the same number of ministries) and neglects the transfer of policy jurisdictions between ministries. It is therefore not too surprising to find even more frequent changes using our more fine-grained data.

Against our hypotheses, changes in the cabinet's policy position (Hypothesis 3; lower left panel) and fragmentation (Hypothesis 4, lower right panel) decrease the chances of portfolio design reform when controlling for partisan and prime ministerial change. However, both effects are substantially weak. Changing the cabinet's policy position by one standard deviation (0.8 points on a 0–10 scale) decreases the predicted probability of a reform having occurred after one year by roughly 1 percentage point (from 1 to 2 per cent). The effect of changes in the cabinet's fragmentation has roughly the same magnitude. Thus, the overall assessment of Hypotheses 3 and 4 is ambivalent. While both variables have the expected unconditional effects in Models 3 and 4, the full model suggests that these findings are due to the simultaneous occurrence of more fundamental changes such as a new prime minister and a novel partisan composition of the cabinet. These findings indicate that binary measures of fundamental changes are sufficient for explaining reforms in portfolio design, whereas gradual measures of the magnitude of changes in the cabinet have no additional effects.

Turning to the control variables, the probability of portfolio design reforms is substantially higher after general elections and for coalition governments. Both findings are consistent with a political logic in which elections are decisive events and the distribution of benefits among multiple cabinet parties is a major driver of reforms. The formal rules on how the portfolio design can be changed (decrees vs. laws) also affect reform frequency: portfolio designs that can only be changed by laws are somewhat more stable than those that can be altered by decrees. The control variable on caretaker status and the decade dummies do not have statistically significant effects. Finally, there is evidence that economic performance affects portfolio design change: the probability of reform increases with increases in the unemployment rate, which can be interpreted as an institutional reaction to performance deficits.

Conclusion

As the first systematic comparative study of changes in the design of government portfolios in Western European democracies, this article provides two core insights. First, reforms of portfolio design are frequent (339 cases in nine countries over a period of forty-five years). This finding casts serious doubt on the standard assumption of coalition researchers that ‘the administrative structure of the state changes only very occasionally in the real world’ (Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996, 271). Secondly, these reforms occur after political events, most notably changes in prime minister or a government's party composition. These findings suggest that changes in portfolio design follow a political logic that is driven by preference alterations among the relevant political actors.

Our findings have important implications for the general literature on institutional design and for coalition research. For one, the patterns of change are consistent with previous research on purposive institutional design, which demonstrates that reforms of electoral systems, parliamentary organization and political regime types can be explained with reference to political actors’ goals and strategies. While the timing of reforms suggests a political logic for portfolio design as well, timing data cannot provide direct evidence to support this argument because it does not capture which actors benefit from these reforms.

In future work we seek to explore this question in greater detail. For example, do parties use changes in portfolio design to increase their payoffs in the portfolio allocation process, either in quantitative terms (for example, Sieberer Reference Sieberer2015; Warwick and Druckman Reference Warwick and Druckman2006) or qualitatively by allocating responsibilities in accordance with parties' substantive priorities (for example, Bäck, Debus and Dumont Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011)? And do government parties deliberately allocate policy jurisdictions to different departments to keep tabs on their coalition partners on highly divisive issues, as research on coalition governance suggests (for example, Carroll and Cox Reference Carroll and Cox2012; Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2011; Strøm, Müller and Bergman Reference Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008; Thies Reference Thies2001)? These questions point to more specific motivations of why cabinet parties seek particular changes in portfolio design. More targeted theoretical models based on such motivations yield hypotheses on the conditions under which specific changes should occur, and on the beneficiaries of such reforms. Obviously, there is much more to be done to understand why and how political actors use portfolio design to achieve various political goals – and the findings of this article indicate that such analyses based on a political logic of portfolio design merit attention in future research.

Secondly, the frequency of reforms casts serious doubt on the validity of assuming that government portfolios are exogenous to the government formation process, as the vast majority of studies on the allocation of government portfolios does (for example, Bäck, Debus and Dumont Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011; Carroll and Cox Reference Carroll and Cox2007; Ecker, Meyer and Müller Reference Ecker, Meyer and Müller2015; Falcó-Gimeno and Indridason Reference Falcó-Gimeno and Indridason2013; Laver Reference Laver1998; Laver and Schofield Reference Laver and Schofield1990; Verzichelli Reference Verzichelli, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008; Warwick and Druckman Reference Warwick and Druckman2006). Our findings suggest that the design of portfolios is not exogenous but should be conceptualized as an important outcome of the government formation process. Thus, they highlight the need for an integrative analysis of different decisions taken during coalition formation. These decisions include the partisan composition of the cabinet, its policy program, portfolio allocation, and also portfolio design. Recent work has begun to endogenize some aspects such as the choice of formateur that have previously been taken as exogenous when explaining portfolio allocation (Bassi Reference Bassi2013; Cutler et al. Reference Cutler2016). Our findings suggest that the design of cabinet portfolios constitutes another dimension we need to consider in moving towards an integrative analysis of government formation as a multidimensional bargain (Dewan and Hortala-Vallve Reference Dewan and Hortala-Vallve2011).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge financial support by the Austrian Research Association (ÖFG) and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under grant P25490. A previous version of the manuscript was presented at the 2017 ECPR General Conference in Oslo. We thank all participants for helpful feedback and suggestions and Teresa Haudum for excellent research assistance.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MOMRJK and online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000346.