INTRODUCTION

The power of human language comes from its links to our conceptual systems. In acquiring language, we acquire a means of encoding perceptual input as objects of thought (Fausey & Boroditsky, Reference Fausey and Boroditsky2008; Frank, Everett, Fedorenko & Gibson, Reference Frank, Everett, Fedorenko and Gibson2008; Gleitman & Papafragou, Reference Gleitman, Papafragou, Holyoak and Morrison2005; Winawer, Witthoft, Frank, Wu, Wade & Boroditsky, Reference Winawer, Witthoft, Frank, Wu, Wade and Boroditsky2007), and a means of combining elemental concepts to form more complex ones (Chomsky, Reference Chomsky2011; Condry & Spelke, Reference Condry and Spelke2008; Murphy, Reference Murphy1990). Language is also the bedrock of cultural transmission, providing an exceptionally powerful and efficient channel for sharing our thoughts and beliefs with others (Anggoro, Waxman & Medin, Reference Anggoro, Waxman and Medin2008; Pinker & Jackendoff, Reference Pinker and Jackendoff2005; Tomasello, Reference Tomasello2000; Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1962; Waxman, Reference Waxman, Medin and Atran1999b). Although research in philosophy and psychology makes it quite clear that there are distinctions between language and thought, they are often so deeply intertwined in our experience of the world that they seem inseparable (Gleitman & Papafragou, Reference Gleitman, Papafragou, Holyoak and Morrison2005; Pinker, Reference Pinker2007). It is unsurprising, then, that some of the most compelling and enduring questions in the developmental and cognitive sciences have focused on identifying the links between language and thought, and how these are shaped over development (Gentner & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Gentner and Goldin-Meadow2003; Waxman, Reference Waxman, Medin and Atran1999b, Reference Waxman and Goswami2002).

Over a half century of research has unearthed at least one striking link between language and one fundamental conceptual process, object categorization. Studies of this link reveal that ways in which objects are named guides learners’ organization of these objects into mental categories. When the same noun is applied consistently to a set of distinct objects, both infants and adults alike are more likely to represent them as members of the same object category (Gelman & Heyman, Reference Gelman and Heyman1999; Keates & Graham, Reference Keates and Graham2008; Lupyan, Reference Lupyan2008; Lupyan, Rakison & McClelland, Reference Lupyan, Rakison and McClelland2007; Waxman, Reference Waxman, Medin and Atran1999b; Waxman & Booth, Reference Waxman and Booth2001, Reference Waxman and Booth2003; Waxman & Hall, Reference Waxman and Hall1993; Waxman & Markow, Reference Waxman and Markow1995). Conversely, hearing different nouns applied to a set of distinct objects draws learners’ attention to distinctions among objects, facilitating their representations as distinct individuals or distinct categories (Dewar & Xu, Reference Dewar and Xu2007, Reference Dewar and Xu2009; Feigenson & Halberda, Reference Feigenson and Halberda2008; Ferguson, Havy & Waxman Reference Ferguson, Havy and Waxman2015; Keates & Graham, Reference Keates and Graham2008; Landau & Shipley, Reference Landau and Shipley2001; Scott & Monesson, Reference Scott and Monesson2009; Waxman & Braun, Reference Waxman and Braun2005; Xu, Reference Xu2002; Xu, Cote & Baker, Reference Xu, Cote and Baker2005; Zosh & Feigenson, Reference Zosh, Feigenson, Santos and Hood2009).

Categorization is a fundamental building block of cognition (Mandler & McDonough, Reference Mandler and McDonough1993; Mareschal & Quinn, Reference Mareschal and Quinn2001; Mervis & Rosch, Reference Mervis and Rosch1981; Murphy, Reference Murphy2004; Sloman, Malt & Fridman, Reference Sloman, Malt, Fridman, Hahn and Ramscar2001; Smith & Medin, Reference Smith and Medin1981), and thus this evidence documenting the power of naming on categorization has garnered considerable attention (e.g. Diesendruck, Reference Diesendruck2003; Gershkoff-Stowe, Thal, Smith & Namy, Reference Gershkoff-Stowe, Thal, Smith and Namy1997; Lupyan et al., Reference Lupyan, Rakison and McClelland2007; Plunkett, Reference Plunkett2008; Sloutsky & Fisher, Reference Sloutsky and Fisher2004; Waxman & Gelman, Reference Waxman and Gelman2009). When we identify two objects as members of the same category, we establish their equivalence, permitting us to identify new members of the category and to make inferences about non-obvious properties from one member of the category to another (Bhatt, Wasserman & Reynolds, Reference Bhatt, Wasserman, Reynolds and Knauss1988; Murphy, Reference Murphy2004; Smith & Heise, Reference Smith., Heise and Bums1992). This seemingly simple feat has tremendous consequences on subsequent learning; for example, by establishing the category dog, we can learn from just one negative encounter to avoid all angry dogs (even ones we have not yet seen), instead of painfully and repeatedly learning from encounters in which each individual dog bares its teeth.

Categorization is also fundamental to word learning. To successfully learn the meaning of a novel word, infants and young children must map a phonological representation to the identifiable category, or referent, to which it refers. In other words, they must understand that the referent of a novel noun like fridge applies not only to the appliance in their own kitchen but also in others’. Recent research suggests that infants have established such mappings; that is, they extend even their earliest words beyond named exemplars to other members of the same object category (Bergelson & Swingley, Reference Bergelson and Swingley2012; Tincoff & Jusczyk, Reference Tincoff and Jusczyk2012). Most of infants’ early words are nouns, and most of these extend beyond distinct individuals (e.g. “Magic”) to categories (doggie). Moreover, infants’ ability to map nouns to object categories serves as a stepping-stone for the acquisition of other kinds of words, including verbs and adjectives, because the meanings of these predicates are informed by the nouns that they take as arguments (Fisher, Gertner, Scott & Yuan, Reference Fisher, Gertner, Scott and Yuan2010; Gleitman, Reference Gleitman1990; Klibanoff & Waxman, Reference Klibanoff and Waxman2000; Waxman & Lidz, Reference Waxman, Lidz, Kuhn and Siegler2006). From this perspective, then, infants’ and young children's early links between language and object categories serve as an engine that catalyzes subsequent language and conceptual development.

Our goal in this paper is to summarize the evidence documenting the emergence of a link between naming and object categorization and how it is shaped in the first few years of life. We begin by describing a foundational study, one that demonstrates the power of naming on object categorization at 12 months of age. We then look ahead in development, pointing to evidence documenting that toddlers increasingly refine this link over the second year of life, as they cull distinct ‘kinds’ of words in the input (e.g. nouns, adjectives, verbs) and link each to a distinct ‘kind’ of referent (e.g. categories of objects, properties of objects, categories of events or relations). Next, we set our sights in a different direction, looking back in development to identify the origin of infants’ links between language and categorization in the first year of life.

This review – looking forward and backward in developmental time – reveals a cascading process in which infants’ earliest language–cognition links provide the foundation for later ones. To foreshadow, we propose that the power of language on cognition is initially grounded in its status as a social, communicative signal. Within the first year, infants home in on its referential status and, in the second year, they begin to tease apart the distinct kinds of words (e.g. nouns, verbs, adjectives) and link them to distinct kinds of reference.

We also discuss several alternative theoretical proposals. Some have attributed the link between language and cognition entirely to lower-level perceptual processes. On one view, ‘labels-as-features’, words promote object categorization simply because infants associate the words that co-occur with objects as perceptual ‘features’ of the objects themselves (Deng & Sloutsky, Reference Deng and Sloutsky2012; Sloutsky, Reference Sloutsky2010; Sloutsky & Fisher, Reference Sloutsky and Fisher2012). On this view, because objects from the same category tend to co-occur with the same labels, naming (like any shared perceptual feature) increases the similarity among named objects and in this way promotes object categorization. However, as will become clear as our review unfolds, this view cannot account for the evidence. First, there is strong evidence that when names are paired systematically with objects, they consistently promote categorization, but that when other engaging sounds (e.g. tone sequences, backward speech) are paired systematically with objects, they engender no such boost to infants’ categorization. Second, this view cannot accommodate the fact that, within the second year of life, different kinds of words highlight different kinds of commonalities among objects. The labels-as-features view has no account for why, at this juncture, nouns highlight category-based commonalities but adjectives highlight property-based commonalities, including color and texture.

Another low-level account focused on processing, ‘auditory overshadowing’, argues that the gap between language and other non-linguistic sounds can be reduced to an effect of auditory familiarity. Here the claim is that because infants are more familiar with the sounds of speech than with other non-linguistic sounds (Robinson & Sloutsky, Reference Robinson and Sloutsky2007,; Reference Robinson and Sloutsky2007b; Robinson, Best, Deng & Sloutsky, Reference Robinson, Best, Deng and Sloutsky2012; Sloutsky & Robinson, Reference Sloutsky and Robinson2008), and because it is less costly to process familiar than novel stimuli, non-linguistic sounds can ‘overshadow’ infants’ ability to process materials simultaneously presented in the visual modality (see also Lewkowicz, Reference Lewkowicz1988a, Reference Lewkowicz1988b). Therefore, although language appears to promote object categorization, it may in fact be merely less disruptive than the other less familiar sounds. While this account can capture some differences between linguistic and non-linguistic sounds, like the labels-as-features above, it is stretched to explain why different kinds of language (e.g. nouns, adjectives) which differ in meaning – but, critically, not in acoustic familiarity – have different conceptual consequences, or why, as we will discuss, a select group of unfamiliar signals also promotes categorization early in infancy.

Another relevant theory, ‘natural pedagogy’, is closer in spirit to our own position, but still differs considerably, especially with regard to the developmental processes underlying the link between language and categorization in the first two years of life. Natural pedagogy asserts that the power of language comes, at least in part, from its social, communicative status, and we agree. But natural pedagogy also claims that other communicative signals (e.g. eye-gaze, pointing) are on par with language vis-à-vis their effects on cognition (Csibra & Gergely, Reference Csibra, Gergely, Munakata and Johnson2006, Reference Csibra and Gergely2009; Csibra & Shamsudheen, Reference Csibra and Shamsudheen2015; Futó, Téglás, Csibra & Gergely, Reference Futó, Téglás, Csibra and Gergely2010; Hernik & Csibra, Reference Hernik and Csibra2015; Marno, Davelaar & Csibra, Reference Marno, Davelaar and Csibra2014; Reference Marno, Davelaar and Csibra2016; Yoon, Johnson & Csibra, Reference Yoon, Johnson and Csibra2008), that human infants are born with an expectation that information conveyed by a pedagogical partner (e.g. a parent) via ostensive, communicative signals is ‘kind-relevant’, and that as a result communicative signals (including, but not limited to, language) bias infants toward establishing categories of object kinds. We agree that infant cognition is guided by the social, communicative status of language in the first year. Where we differ is in our view of the function of language as primarily kind-relevant, and in our view of developmental processes underlying language over the course of this first year. In our view, language ‘parts company’ from the other communicative signals in the first year, as infants pinpoint with increasing precision the range of meaning that can be conveyed with language.

We discuss these alternative accounts at various junctures in this review, as evidence relevant to each account is introduced.

LINKING LANGUAGE AND CATEGORIZATION – A FOUNDATIONAL STUDY

Waxman and Markow (Reference Waxman and Markow1995) offered the first evidence of a link between language and object categorization in infants who were on the verge of producing their first words. They recruited 12-month-old infants to participate in a classic categorization task, one that included a familiarization phase and a test phase (see Figure 1). During familiarization, infants were shown several members of a category (e.g. animal), each accompanied by a phrase. What varied was the particular phrase infants heard. Infants in a Word condition heard a novel noun applied to each object (e.g. “Look! This is a blick! … Do you see the blick?”); those in a No Word control condition heard phrases that drew their attention to the objects but included no novel words (e.g. “Look what's here … Do you like it?”). At test, infants viewed two novel objects simultaneously. One was a novel member of the now-familiar category (e.g. a new animal), and the other a member of a new object category to which infants had not yet been exposed (e.g. a piece of fruit).

Fig. 1. A representation of stimuli and results from Waxman and Markow (Reference Waxman and Markow1995) and Balaban and Waxman (Reference Balaban and Waxman1997).

This design took advantage of decades of research in infant cognition (Colombo & Bundy, Reference Colombo and Bundy1983; Eimas & Quinn, Reference Eimas and Quinn1994; Fantz, Reference Fantz1963; Spelke & Kestenbaum, Reference Spelke and Kestenbaum1986) documenting that if infants notice the commonality among the objects presented during familiarization, then they show a preference for the novel over the familiar test object, and that conversely, infants who fail to detect this category during familiarization show no preference at test.

Building on this logic, Waxman and Markow (Reference Waxman and Markow1995) manipulated the design to consider the contribution of naming. They reasoned that, if novel nouns support object categorization in infants as young as 12 months, then infants in the Word condition should more successfully form categories than those not hearing novel words (No Word condition). Their results supported this prediction, documenting that by 12 months of age, infants have begun to establish a link between object naming and object categorization (for further evidence at 12 months, see Ferguson, Havy & Waxman, Reference Ferguson, Havy and Waxman2015; Fulkerson & Haaf, Reference Fulkerson and Haaf2006; Waxman & Braun, Reference Waxman and Braun2005).

Balaban and Waxman (Reference Balaban and Waxman1997) provided additional evidence for the power of language in slightly younger infants. They compared the effect of novel words versus tone sequences on 9-month-olds’ categorization. Once again, infants in a Word condition heard a naming phrase accompanying each familiarization object. But infants in a Tones condition heard a sequence of sine-wave tones accompanying each object. These tone sequences were carefully matched to match the Word condition in mean frequency, duration, and pause length. They reasoned that, if any consistently applied sound promotes 9-month-olds’ object categorization, then infants in both of these conditions should succeed in forming the category; however, if language exerts a unique effect on categorization as early as 9 months, then infants in the Word condition but not the Tones condition should succeed. The results were clear: infants in the Word condition successfully formed categories, but those in the Tones condition performed at chance level. This documented an advantage for novel words over carefully matched non-linguistic control stimuli in infants as young as 9 months of age.

Together, these studies provided evidence that the link between language and categories is established early, and that it is not built up from associations between words in infants’ existing vocabulary (Smith, Reference Smith, Golinkoff and Hirsh-Pasek2000). After all, infants at 9 and 12 months of age produce only a few, if any, words on their own. Instead, the data reveal that a link between language and object categories is not the result of lexical development, but instead is in place early enough to support infants’ vocabulary development from the start.

Notice that neither the labels-as-features nor the auditory overshadowing accounts can account for both of these results on their own. The labels-as-features account best explains Waxman and Markow's (Reference Waxman and Markow1995) finding that infants who heard a count noun consistently applied to a set of objects more reliably categorize them than do infants in a No Word condition. On the labels-as-features account, for infants in the Word (but not the No Word) condition, the shared novel noun increases the similarity among the familiarization objects, and thereby supports categorization. Infants in the No Word condition did not benefit from this increased similarity and therefore failed to form the categories. But this account cannot accommodate Balaban and Waxman's (Reference Balaban and Waxman1997) finding that novel tone sequences – which were also applied consistently to all familiarization objects – failed to exert this advantageous effect. If any consistently paired auditory ‘feature’ account can increase the similarity of the objects with which it is paired, then both words and tones should exert the same influence.

On the other hand, auditory overshadowing can explain Balaban and Waxman's (Reference Balaban and Waxman1997) finding, but not Waxman and Markow's (Reference Waxman and Markow1995). In the case of Balaban and Waxman (Reference Balaban and Waxman1997), auditory overshadowing would suggest that infants hearing language (but not tones) formed object categories because the tone sequences were less familiar than language. But the auditory overshadowing account cannot explain why certain kinds of language (e.g. “Look at the toma”) facilitate categorization, while other kinds of language (e.g. “Look at this”) fail to do so. In short, each of these alternative proposals can accommodate one set of findings, but neither can explain both.

These results also bear on the proposal concerning ‘natural pedagogy’ (Csibra & Gergely, Reference Csibra and Gergely2009). In Waxman and Markow (Reference Waxman and Markow1995), all infants were introduced to the familiarization objects in conjunction with human speech – a pedagogical cue. Although infants in the Word condition (“Look at the toma”) successfully formed object categories, those in the No Word condition (“Look at this!”) did not. This reveals that by 12 months, infants have precise expectations about the functions of language: novel nouns, but not any referring phrase, refer to object categories. Thus, infants do not interpret all communicative signals as kind-relevant (cf. Csibra & Gergely, Reference Csibra and Gergely2009); rather, by their first birthdays, when infants begin to build their own productive lexicons, they have distinguished naming from other functions of language and link object naming alone to object categorization.

This evidence from 9- to 12-month-old infants, although impressive, also raised new developmental questions. When do infants establish more precise links, mapping certain kinds of words (e.g. nouns) to object categories, but other kinds of words (e.g. adjectives, verbs) to different kinds of meaning (e.g. object properties, event categories)?

SPECIFYING THE LINK: A LOOK FORWARD IN DEVELOPMENT

The links between language and categorization expressed in 12-month-olds do not remain constant across development. On the contrary, infants’ expectations about naming become increasingly precise during their second year. During this time, infants tease apart the nouns from the other grammatical forms (e.g. adjectives, verbs) and map them specifically to object categories rather than surface properties (like color) or actions in which they are involved (like running). Consider, for example, a scene in which a group of horses jumps over a fence. Infants in the second year of life focus on different aspects of this scene, depending upon how it is described. So do older children and adults. For example, nouns (e.g. “Look! They're horses!”) focus our attention on the object category. But verbs (e.g. “Look! They're running!”) direct our attention to the action, and adjectives (e.g. “Look! They're white!”) refer neither to the objects or event, but to a property of the objects. We know that even infants can use the position of a word within a sentence to distinguish among grammatical categories (Hall, Veltkamp & Turkel, Reference Hall, Veltkamp and Turkel2004; Höhle, Weissenborn, Kiefer & Schulz, Reference Höhle, Weissenborn, Kiefer and Schulz2004; Mintz, Reference Mintz2003; Shi, Reference Shi2014; Waxman & Lidz, Reference Waxman, Lidz, Kuhn and Siegler2006; Weisleder & Waxman, Reference Weisleder and Waxman2010) and, by 18 to 24 months, they forge increasingly precise links between distinct grammatical forms and their distinct kinds of meaning. They link nouns to object categories, verbs to actions and relations among objects, and adjectives to object properties.

These more specific links between distinct kinds of words and distinct kinds of meaning unfold in a cascading fashion (see Waxman & Lidz, Reference Waxman, Lidz, Kuhn and Siegler2006, for a comprehensive review). First, by 13 months, infants tease apart the nouns from other grammatical categories and link them specifically to object categories. Next, with this noun–object category link in place, they go on to forge the more precise links for predicates, including adjectives and verbs, whose meaning depends in part upon the nouns they take as arguments.

Until roughly 12 months of age, infants appear to be ‘generalists’ when it comes to linking words and concept. Novel words, be they presented as nouns or adjectives, highlight any kind of commonality among objects (e.g. category-based or property-based commonalities) (Waxman, Reference Waxman, Medin and Atran1999b; Waxman & Booth, Reference Waxman and Booth2003; Waxman & Markow, Reference Waxman and Markow1995). A clear demonstration of this can be found in a study by Waxman and Booth (Reference Waxman and Booth2003), in which they presented 11-month-old infants with a set of four objects (e.g. 4 different purple horses) that shared both a category-based (horse) and property-based (purple) commonality (see Figure 2). At issue was whether infants focused on categories or properties, and whether their focus was shaped by the language they heard as they viewed these objects (Waxman & Booth, Reference Waxman and Booth2003). To assess this, infants participated in either a ‘property’ extension test (e.g. pitting a new purple horse against a new green horse) or a ‘category’ extension test (e.g. pitting a new purple horse against a new purple chair). They reasoned as follows: if infants expect that different kinds of words refer to different kinds of meaning, then their performance in the Noun and Adjective conditions should differ. More specifically, if they map nouns to object categories and adjectives to object properties, then (1) infants for whom the familiarization objects were introduced with a novel noun should successfully extend the noun to another horse but not to other objects sharing only color, but not category membership, and (2) infants who were introduced to novel adjectives should successfully extend them to the object property, but not the category. Demonstrating the infants’ status as generalists at this age, Waxman and Booth (Reference Waxman and Booth2003) found that 11-month-olds who heard either kind of novel word (either nouns or adjectives) focused on either kind of commonality (category- or property-based); they extended the novel word either by property or by category, depending on their test condition. In contrast, 11-month-olds in a No Word condition (“Can you give me that one?”) performed at chance.

Fig. 2. A representation of stimuli and results from Booth and Waxman (Reference Booth and Waxman2003), Waxman (1999), and Waxman and Booth (Reference Waxman and Booth2003).

But infants do not remain generalists for long. By 13 months, they have teased apart the nouns in the input and have begun to link them specifically to object categories, but not object properties. In other words, in the categorization task described above, 13-month-olds extend novel nouns on the basis of category-based, but not property-based, commonalities (Waxman, Reference Waxman1999a). Nevertheless, 13-month-olds have not yet acquired a comparably precise expectation for adjectives. Instead, for most of their second year, infants continue to link novel adjectives to either category-based (e.g. horse) or property-based (e.g. color, texture) commonalities (Booth & Waxman, Reference Booth and Waxman2009; Imai & Gentner, Reference Imai and Gentner1997; Waxman, Reference Waxman1999a; Waxman & Booth, Reference Waxman and Booth2003); only later do they begin mapping novel adjectives specifically to property-based, and not category-based, commonalities (Waxman & Markow, Reference Waxman and Markow1998). Moreover, infants’ expectations for novel verbs appear to follow an even more protracted developmental course: only by 24 months do infants reliably map novel verbs to event categories rather than object categories (Arunachalam & Waxman, Reference Arunachalam and Waxman2010; Arunachalam, Escovar, Hansen & Waxman, Reference Arunachalam, Escovar, Hansen and Waxman2013; Syrett, Arunachalam & Waxman, Reference Syrett, Arunachalam and Waxman2013; Tomasello & Kruger, Reference Tomasello and Kruger1992; Waxman, Lidz, Braun & Lavin, Reference Waxman, Lidz, Braun and Lavin2009; Yuan & Fisher, Reference Yuan and Fisher2009).

By tracing infants’ expectations for novel words through the second year of life, a developmental cascade becomes evident, one in which infants discover that there are distinct kinds of words and that each refers to a distinct kind of meaning. This cascade, in which precise expectations for nouns paves the way for expectations for predicate forms, poses challenges for accounts that appeal to perception alone.

The labels-as-features perspective asserts that words are nothing more than perceptual features of the objects to which they are applied. If this were correct, then it is puzzling that novel nouns highlight category-based (but not property-based) commonalities among objects at 13 months (Waxman, Reference Waxman1999a; Waxman & Booth, Reference Waxman and Booth2003). This outcome reveals that labels do more than simply increase the perceived similarity among objects, otherwise novel nouns should highlight both category- and property-based commonalities equally.

Arguments for auditory overshadowing fare no better in accounting for this developmental cascade. After all, infants in the Noun, Adjective, and Verb conditions in these various experiments were all listening to speech. In fact, they heard the very same novel wordforms paired with the very same sets of objects; thus infants’ familiarity with the wordforms and the objects are held constant across conditions and experiments. The only thing that varied was the grammatical context in which a novel word – the same novel word – appeared. Infants’ distinct responses to different kinds of words in these experiments reveal the insufficiency of an auditory overshadowing account. Infants’ performance is mediated by more than the ‘familiarity’ of speech; they are also sensitive to distinctions among distinct kinds of words and the concepts to which they refer.

Finally, these findings also reveal shortcomings in the predictions of natural pedagogy, highlighting that this proposal requires greater precision. Communicative signals of all kinds – including language, eye-gaze, and pointing – can highlight either objects and events (Liszkowski & Carpenter, Reference Liszkowski and Carpenter2007; Namy & Waxman, Reference Namy, Waxman and Namy2005; Peirce, Reference Peirce, Hartshorne and Weiss1932). But only language can single out which of the myriad possible commonalities, present within a particular set of entities, a speaker is referring to. For infants as young as 13 months of age, language does more than highlight object categories or kinds. By this point, infants use the grammatical form of a novel word to shift their perspective on the scene at hand.

THE ORIGINS OF THE LINK: LOOKING BACK INTO INFANTS' FIRST YEAR OF LIFE

In more recent work in our lab, we have shifted our focus to looking back in developmental time. Our goal is to uncover the origin of infants’ earliest links between language and cognition, and to trace how this link unfolds in the infants’ first year.

As a first step in this direction, Fulkerson and Waxman (Reference Fulkerson and Waxman2007) adapted Balaban and Waxman's (Reference Balaban and Waxman1997) categorization task to examine the effect of language on categorization in 6-month-old infants (see Figure 3). In the familiarization phase, infants viewed eight images from a single category (e.g. dinosaurs) one at a time, in random order on a screen. What varied was the auditory input accompanying each image. Infants either heard a novel word (e.g. “Look at the modi! Do you see the modi!”) or the sequence of sine-wave tones. At test, infants viewed two new images, presented in silence – a new member of the familiar category (e.g. another dinosaur) and an object from a novel category (e.g. a fish). Infants who listened to language during familiarization formed object categories, as witnessed by their reliable preference for the novel object at test. In contrast, infants who listened to tone sequences performed at chance levels. Thus, at 6 months, when infants are just beginning to comprehend their first words (Bergelson & Swingley, Reference Bergelson and Swingley2012, Reference Bergelson and Swingley2013, Reference Bergelson and Swingley2015; Tincoff & Jusczyk, Reference Tincoff and Jusczyk1999, Reference Tincoff and Jusczyk2012), they have already begun to link language and object categories.

Fig. 3. A representation of stimuli and results from Balaban and Waxman (Reference Balaban and Waxman1997), Ferry et al. (Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2010, Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2013), and Fulkerson and Waxman (Reference Fulkerson and Waxman2007).

Armed with this evidence, Ferry, Hespos, and Waxman (Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2010) considered still younger infants, extending this task to 3- and 4-month-olds. The results were surprising, and revealed an advantage for language over tones vis-à-vis categorization even in these very young infants: although 3- and 4-month-olds listening to language successfully formed object categories, those listening to sine-wave tone sequences performed at chance levels, just like at 6 and 12 months (Fulkerson & Waxman, Reference Fulkerson and Waxman2007).

These results reveal strong developmental continuity in infants’ response to language versus tones in the first year of life. They also illuminate a surprisingly precocious link between language and categorization, one that is in place early enough to support infants’ very first forays in language and cognitive development. But why does listening to human language ‘boost’ infant cognition so early in development? It is unlikely that 3-month-old infants understand the meanings of any words (Fenson et al., Reference Fenson, Dale, Reznick, Thal, Bates, Hartung and Reilly1993; Frank, Braginsky & Yurovsky, Reference Frank, Braginsky and Yurovsky2016). Indeed, there is little evidence that they can even parse individuals words from the ongoing stream of language (Aslin, Reference Aslin, de Boysson-Bardies, de Schonen, Jusczky, McNeilage and Morton1993; Bortfeld, Morgan, Golinkoff & Rathbun, Reference Bortfeld, Morgan, Golinkoff and Rathbun2005; Jusczyk & Aslin, Reference Jusczyk and Aslin1995; Seidl, Tincoff, Baker & Cristia, Reference Seidl, Tincoff, Baker and Cristia2015). What is it, then, that underlies the cognitive advantage conferred by language at 3 and 4 months? It must be different than at 12 months, because Waxman and Markow's (Reference Waxman and Markow1995) study clearly demonstrated that, by 12 months, identifying a novel word in the speech stream is critical (recall that infants formed object categories when they heard a novel noun consistently applied to the familiarization objects, but not when they heard the same kinds of phrases with no novel word (e.g. “Look at this!”). If 3- and 4-month-olds do not yet parse distinct words from the continuous stream of speech, then what is the mechanism by which language confers its advantage?

Ferry et al. (Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2010) proposed that, for 3- and 4-month-olds, simply listening to language might promote object categorization. Previous studies have shown that infants prefer listening to human speech over other, non-speech sounds (Shultz & Vouloumanos, Reference Shultz and Vouloumanos2010; Vouloumanos, Hauser, Werker & Martin, Reference Vouloumanos, Hauser, Werker and Martin2010). Of course, a preference for speech cannot explain why infants link speech to their construal of the world (that is, the objects they view in our tasks). Perhaps listening to speech not only engages infants’ attention but also promotes their learning. One intriguing aspect of the studies on infants’ preferences for language is that, early on, infants prefer both human speech and non-human primate vocalizations over other sounds, suggesting that they tune their preferences to human speech over the first months of life (Shultz, Vouloumanos, Bennett & Pelphrey, Reference Shultz, Vouloumanos, Bennett and Pelphrey2014; Vouloumanos & Werker, Reference Vouloumanos and Werker2004, Reference Vouloumanos and Werker2007). Might non-human primate vocalizations also promote 3- and 4-month-olds object categorization?

To address this possibility, Ferry, Hespos, and Waxman (Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2013) examined the effect of listening to two new sounds – non-human primate vocalizations and backward speech – on infants’ object categorization at 3-, 4-, and 6-months. The design was identical to the studies by Fulkerson and Waxman (Reference Fulkerson and Waxman2007) and Ferry et al. (Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2010); what varied were the sounds infants listened to during the familiarization period. For half of the infants, the familiarization images were accompanied by a vocalization from a blue-eyed Madagascar lemur (Eulemur macaco flavifrons); for the others, the images were accompanied by a segment of backward speech (the language stimuli from prior experiments, played in reverse). If the initial link between language and cognition, like infants’ initial preferences, encompasses human speech and non-human primate vocalizations, then 3- and 4-month-olds listening to lemur vocalizations should successfully form object categories. Alternatively, if any complex sound promotes object categorization at this young age, then infants listening to either lemur vocalizations or backward speech should successfully form categories.

These results of this study, testing the breadth of sounds that promote 3- and 4-month-olds’ categorization, were clear. Infants listening to backward speech failed to form categories at any age, echoing the results with sine-wave tone sequences at the same ages as in Ferry et al. (Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2010) and Fulkerson and Waxman (Reference Fulkerson and Waxman2007) with a more complex auditory signal. In contrast, the lemur vocalizations conferred the same cognitive advantage as listening to human language: 3- and 4-month-olds in the lemur condition successfully formed object categories, performing identically at test as infants in Fulkerson and Waxman's (Reference Fulkerson and Waxman2007) study with human speech. Yet this effect was short-lived; by 6 months, infants had tuned the link specifically to language. At 6 months, lemur vocalizations no longer conferred infants any benefit in categorization (Ferry et al., Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2013).

This work offers two insights into the origins of infants’ earliest links between language and cognition. First, at 3 and 4 months, the link is sufficiently broad to encompass vocalizations of both humans and non-human primates. Second, by 6 months, infants tune this initially broad link to the signal that will ultimately carry meaning: human speech.

These results also posed new challenges to alternative accounts for the link between language and cognition in infancy. First, the auditory overshadowing account cannot accommodate the facilitative effect of lemur vocalizations on 3- and 4-month-olds’ object categorization. Lemur calls are certainly unfamiliar to 3- and 4-month-olds, yet they facilitated (rather than hindered) infants’ object categorization. Auditory overshadowing also fails to account for the finding that infants tune out the effect of lemur vocalizations by 6 months. After all, the assumption underlying the overshadowing account rests on the processing load imposed by an unfamiliar versus familiar signal. Yet infants’ exposure to lemur vocalizations likely remains sparse – and therefore constant – between 3 and 6 months.

These results also expose limitations in the theory of natural pedagogy, a theory that has not engaged key developmental questions, including which signals very young infants identify as communicative and how the pedagogical force of these signals changes over the first years. Ferry et al.’s (Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2010, Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2013) results provide clear evidence that what counts as a communicative signal changes with development.

In subsequent work, we have gone further to consider the processes that mediate infants’ interpretation signals like lemur calls and tone sequences over the first year, pinpointing the role of passive and communicative experience.

A CLOSER LOOK: HOW DO INFANTS ‘TUNE’ THE LINK BETWEEN LANGUAGE AND OBJECT CATEGORIZATION?

Ferry et al.’s (Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2013) results documented the first evidence that the link between language and categorization may be ‘tuned’ early in development. Tuning processes are ubiquitous in infant perceptual development (e.g. face perception, speech perception; Krentz & Corina, Reference Krentz and Corina2008; Lewkowicz & Ghazanfar, Reference Lewkowicz and Ghazanfar2009; Maurer & Werker, Reference Maurer and Werker2013; Palmer, Fais, Golinkoff & Werker, Reference Palmer, Fais, Golinkoff and Werker2012; Pascalis, Loevenbruck, Quinn, Kandel, Tanaka & Lee, Reference Pascalis, Loevenbruck, Quinn, Kandel, Tanaka and Lee2014; Quinn, Lee, Pascalis & Tanaka, Reference Quinn, Lee, Pascalis and Tanaka2015; Scott & Monesson, Reference Scott and Monesson2009, Reference Scott and Monesson2010; Werker & Tees, Reference Werker and Tees1984). But the results reported by Ferry et al. (Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2013) document more than just perceptual tuning. Instead, their results were the first to document that infants tune the ‘link’ between language and categorization in the first 6 months of life.

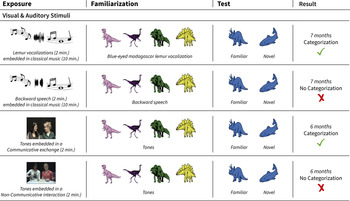

With this effect as a foundation, we have gone on to examine the relative contributions of maturation and experience as infants tune this link (Perszyk, Ferguson & Waxman, Reference Perszyk, Ferguson and Waxmanin press) (see Figure 4).

Fig. 4. A representation of stimuli and results from Ferguson and Waxman (Reference Ferguson and Waxman2016) and Perszyk and Waxman (2016).

How far can experience take us? Documenting the effect of ‘mere exposure’ to non-language sounds

In one recent line of research, we asked whether and how infants’ experience contributed to tuning this link between language and categorization. Perhaps infants’ frequent exposure to human speech in their everyday environments permits them to maintain the link between speech and object categorization while ‘tuning out’ the influence of non-human primate vocalizations, which are likely absent in their environments.

One way to assess the role of experience is to manipulate it experimentally. A signature of experience-based tuning processes is the powerful role of later exposure: once infants have tuned out an earlier sensitivity, this sensitivity may be reinstated if infants are re-exposed to the signal anew, during what is known as a ‘sensitive period’ (Johnson & Newport, Reference Johnson and Newport1989; Kuhl, Tsao & Liu, Reference Kuhl, Tsao and Liu2003; Werker & Hensch, Reference Werker and Hensch2015). Might this signature of experience-based tuning be evident in the link between a signal and categorization? If infants’ experience is essential, then exposing infants to lemur vocalizations might permit them to ‘re-open’ the link to categorization.

Perszyk and Waxman (2016) addressed this question by systematically manipulating 7-month-old infants’ exposure to lemur vocalizations. When infants entered the lab's waiting room, they listened to a 10-minute audio track comprised of instrumental music (e.g. a Bach quartet), interspersed at irregular intervals with several distinct lemur vocalizations. This provided infants with a total of 2 minutes of passive exposure to lemur vocalizations. Importantly, these vocalizations were not connected to any communicative function. Next, infants entered the testing room to participate in the same categorization task while listening to lemur vocalizations (as in Ferry et al., Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2013). If experience is instrumental in tuning the link, then even this brief exposure with lemur vocalizations should be enough for 7-month-olds to reinstate the earlier link between lemur vocalizations and object categorization.

This prediction was borne out. In contrast to their peers provided with no such exposure (Ferry et al., Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2013), 7-month-olds who had been exposed to lemur vocalizations in the lab successfully formed object categories while listening to lemur vocalizations (Perszyk & Waxman, 2016). This identifies infants’ flexibility and a critical role for experience in tuning the link to cognition: even 2 minutes of exposure permitted 7-month-olds to link lemur vocalizations to categorization. Without this exposure, the link had been severed.

But perhaps exposure to any sound – not only those that initially promote categorization – would have been sufficient to promote infants’ categorization. This is the prediction of the auditory overshadowing account. Perszyk and Waxman (2016) provided clear evidence against this possibility by exposing another group of infants to the same classical music audio track but, this time, replacing the lemur vocalizations with segments of backward speech, a signal that fails to promote object categorization at any age (Ferry et al., Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2013). Although infants’ exposure to backward speech or lemur vocalizations was identical in the two conditions, the results were quite different: infants exposed to backward speech failed to form object categories in our task. This striking contrast suggests that exposure may be instrumental in maintaining a link between an auditory signal and categorization only if that signal is part of the initially privileged set of sounds that infants previously linked to categorization. A goal of our ongoing work is to specify the range of signals that are initially privileged in this way.

Can infants interpret otherwise arbitrary sounds as communicative? The power of embedding signals in a social-communicative exchange

In a complementary line of work, we have asked about the developmental fate of signals that fall outside the initially privileged set – like sine-wave tone sequences and backward speech – signals that infants consistently fail to link to object categorization throughout their first year (Ferry et al., Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2010; Fulkerson & Waxman, Reference Fulkerson and Waxman2007). As adults, we can flexibly link many signals to meaning, even unnatural signals like the beeps of Morse code. But what about infants? Might there be some path by which even infants will privilege these otherwise inert sounds to communicative status and link them to categorization? Or does this capacity come only later, after they have established a foundational communicative system, such as language?

We reasoned that if we embedded these sounds in communicative episodes, then infants might interpret them as communicative. At issue, though, was whether by raising them to communicative status, these signals might then (like language) promote infants’ categorization. Our hypothesis was motivated by three other lines of research. First, myriad studies have demonstrated that, even from birth, infants are drawn not only to speech, but also to other communicative stimuli. For example, infants prefer to look at face-like stimuli over non-faces (Farroni, Johnson, Menon, Zulian, Faraguna & Csibra, Reference Farroni, Johnson, Menon, Zulian, Faraguna and Csibra2005; Valenza, Simion & Cassia, Reference Valenza, Simion and Cassia1996) and to look at communicative gestures over non-communicative pantomime (Krentz & Corina, Reference Krentz and Corina2008). Second, beginning around 6 months, infants appear to represent the communicative function of some signals in social interactions (Grossmann, Parise & Friederici, Reference Grossmann, Parise and Friederici2010; Krehm, Onishi & Vouloumanos, Reference Krehm, Onishi and Vouloumanos2014; Lloyd-Fox, Széplaki-Köllőd, Yin & Csibra, Reference Lloyd-Fox, Széplaki-Köllőd, Yin and Csibra2015; Parise & Csibra, Reference Parise and Csibra2013; Vouloumanos, Martin & Onishi, Reference Vouloumanos, Martin and Onishi2014; Vouloumanos, Onishi & Pogue, Reference Vouloumanos, Onishi and Pogue2012). Finally, as discussed with respect to natural pedagogy, a range of communicative signals beyond speech (e.g. pointing and eye-gaze) appear to shape infants’ learning, at least in some contexts. Of particular interest to us, given that we have been investigating object categorization, is the claim that infants encode category-relevant properties of novel objects more effectively in communicative contexts than in non-communicative contexts (Csibra & Gergely, Reference Csibra and Gergely2009; Futó et al., Reference Futó, Téglás, Csibra and Gergely2010; Hernik & Csibra, Reference Hernik and Csibra2015; Wu, Gopnik, Richardson & Kirkham, Reference Wu, Gopnik, Richardson and Kirkham2011; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Johnson and Csibra2008). Together, these lines of research raise an intriguing possibility: if infants are first introduced to the otherwise inert sound as if it, like language, is a communicative signal, this sound may be elevated to communicative status and might subsequently promote infants’ object categorization.

To address this possibility, we turned our focus to sine-wave tone sequences, asking whether they might, in fact, promote 6-month-olds’ object categorization if, just prior to the categorization task, we introduced infants to the tones as if they were a communicative signal. We created a brief (2-minute) vignette depicting a dialogue between two actors. One of the actors spoke in English and the other responded using sine-wave tone sequences. This vignette clearly demonstrated that the tones served a communicative function. After viewing this vignette, infants participated in the categorization task while listening to tone sequences (Fulkerson & Waxman, Reference Fulkerson and Waxman2007). The vignette had a remarkable impact: after observing the tone sequences embedded in a social, communicative exchange, 6-month-olds successfully categorized while listening to tones, something we had not yet seen in any prior study at any age (Ferguson & Waxman, Reference Ferguson and Waxman2016). This suggests that when an otherwise inert signal is introduced in the context of a social, communicative exchange, 6-month-old infants elevate this signal to communicative status and forge an entirely new link between this signal and categorization.

Moreover, this effect is related specifically to communicative information; simply familiarizing infants to the tones – absent any communicative exchange – does not promote their use in categorization. To demonstrate this, we familiarized another group of infants to precisely the same tone sequences, but uncoupled them from the communicative episode, offering no evidence that tones served a communicative function. In this condition, we modified the vignette so that the ‘conversation’ (i.e. the speech and tone sounds) played in the background – as if the sounds were playing on the radio – while the two actors engaged in a separate, cooperative task. Although infants in this condition heard precisely the same tones for precisely the same amount of time, they failed to form the categories in the subsequent categorization, performing instead at chance levels. This contrast between infants’ success in the communicative condition and failure in the non-communicative control condition reveals the power of ‘communicative’ exposure alone in linking the tones to object categorization at 6 months of age.

This outcome provides the strongest evidence to date against auditory overshadowing (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Best, Deng and Sloutsky2012; Robinson & Sloutsky, Reference Robinson and Sloutsky2007b). Ferguson and Waxman (Reference Ferguson and Waxman2016) held the familiarity of the tones constant across both conditions: infants in the two conditions had the exact same amount of exposure to the tones before the categorization task. Familiarity alone, therefore, cannot explain why only those 6-month-olds exposed to tones as a communicative signal later succeeded in categorizing objects while listening to tones.

Our interpretation of the power of communicative experience in linking an otherwise inert sound (e.g. tones) to object categorization is consistent with the proposal for natural pedagogy (Csibra & Gergely, Reference Csibra and Gergely2009). After learning that the tones were communicative, listening to tones seems to have engendered a communicative context that biased infants toward kind-relevant, generalizable information. Nevertheless, this finding also reveals that the theory of natural pedagogy (and any theory relying on infants’ interpretation of communicative signals) must specify how infants ‘identify’ which signals in their environment are communicative in the first place and how their interpretation of these signals is shaped over development. In future research, it will be important to manipulate systematically infants’ experience with an inert sound such as tones, and to subsequently assess its impact on cognition. This will offer a more nuanced developmental view of how a signal becomes communicative and, from this view, ‘pedagogical’.

A DEVELOPMENTAL CASCADE: INFANTS’ EXPECTATIONS ABOUT ‘LANGUAGE’ CHANGES OVER THE FIRST 12 MONTHS

These investigations into the origins of the link – its initial, broad state and the processes by which it is tuned thereafter – sharpen our understanding of how an early link between language and object categorization evolves early in development. We propose that, at 3 and 4 months, an initially privileged set of sounds – encompassing human speech and non-human primate vocalizations (Ferry et al., Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2010, Reference Ferry, Hespos and Waxman2013) – promotes categorization by broadly engaging infants’ attention. By 6 months, this link is tuned to communicative signals through complementary processes of passive exposure (maintaining the links of those signals to which infants are frequently exposed; Perszyk & Waxman, 2016) and social-communicative exposure (capable of privileging otherwise inert signals to communicative status; Ferguson & Waxman, Reference Ferguson and Waxman2016). Later, as infants approach their first birthday, this broad effect of communicative signals begins to be refined as infants discover which ‘kinds’ of language are particularly relevant to categorization (Fennell & Waxman, Reference Fennell and Waxman2010; Hollich, Hirsh-Pasek & Golinkoff, Reference Hollich, Hirsh-Pasek and Golinkoff2000; Marcus, Fernandes & Johnson, Reference Marcus, Fernandes and Johnson2012; May & Werker, Reference May and Werker2014; Namy & Waxman, Reference Namy and Waxman2000; Woodward & Hoyne, Reference Woodward and Hoyne1999). This discovery prompts a shift in attention from those signals that are ‘communicative’ to the ways in which labels alone are ‘referential’. As infants learn about the referential capacities of different kinds of labels, language becomes capable of more than broadly engaging infants’ attention, but also of highlighting different conceptual interpretations of the very same objects (Booth & Waxman, Reference Booth and Waxman2003, Reference Booth and Waxman2009; Waxman & Booth, Reference Waxman and Booth2003). Only with additional evidence can we identify the mechanisms underlying these shifts.

In these ways, although language promotes categorization throughout the first two years of life, the nature of this influence evolves during this period along with the developing capacities of the infant. Proposals that appeal only to infants’ perceptual experience and processing of language (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Best, Deng and Sloutsky2012; Sloutsky & Fisher, Reference Sloutsky and Fisher2012) cannot capture this dynamic, cascading developmental process. Likewise, although we propose that these links between language and concepts are grounded in infants’ representation of language as a communicative signal, proposals that posit an enduring, static bias in communicative contexts (Csibra & Gergely, Reference Csibra and Gergely2009) also fail to capture this developmental trajectory. While the mechanisms posited by both of these views surely have some role to play in relating language to infants’ cognition, neither appears sufficient in explaining the evidence at hand.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

An important goal for future investigations is to identify which other cognitive capacities – in addition to object categorization – are shaped by language in the first year of life. There are reasons to suspect that language may cast a relatively wide facilitative net (Vouloumanos & Waxman, Reference Vouloumanos and Waxman2014); evidence has already begun to accumulate, suggesting that language promotes other fundamental learning processes, including abstract rule learning (Ferguson & Lew-Williams, Reference Ferguson and Lew-Williams2016; Dawson & Gerken, Reference Dawson and Gerken2009; Marcus, Fernandes & Johnson, Reference Marcus, Fernandes and Johnson2007) and associative learning (Reeb-Sutherland, Fifer, Byrd, Hammock, Levitt & Fox, Reference Reeb-Sutherland, Fifer, Byrd, Hammock, Levitt and Fox2011). Identifying the breadth of language's influences – and the cognitive mechanisms that undergird them – will provide insights into the status of infants’ earliest links between language and cognition, and how they are forged early in development, and will ultimately bring into sharper focus how language and thought become entwined.