Six well-formed crosses were found in different locations along the four directions,

which are the signs with which they customarily request peace.

As a multivalent symbol, the sign of the cross became part of cross-cultural exchanges between indigenous groups and Spanish colonial settlers who used it as an instrument of war or as a diplomatic tool. In the Americas, Spanish conquistadors initially used Latin crosses to claim conquered territory.Footnote 1 According to Patricia Seed, Europeans, in general, were “invoking Rome” as they made their imperial claims.Footnote 2 For instance, they “plant[ed] stone pillars or . . . crosses in the center of native villages.”Footnote 3 When Christopher Columbus arrived on the island of Hispaniola in 1492, his men used wooden crosses to claim what they considered should become Spanish possessions.Footnote 4 In 1524, after the Spanish conquest of the Mexica capital, Franciscan friars set a cross in Tlatelolco, and they reproduced this practice over many parts of New Spain, including the Gran Chichimeca and farther north.Footnote 5 Likewise, when Spanish explorer Francisco de Ulloa set anchor along the central Sonoran shore in 1539, he ordered one of his pilots, Francisco de Preciado, to set a cross on top of a hill and to “take possession of the land in the name of Cortés.”Footnote 6

These familiar references to early Spanish uses of the cross to signify possession or conquest meet a striking counterpart in the archival information of the eighteenth century. Through interdisciplinary research, this article combines and integrates ethnographic testimonies and analyses with archival material to study the complexity in the meanings of crosses as part of cross-cultural exchanges between indigenous groups and colonizers during peace negotiations. It argues that the cross and other symbols became important mechanisms for colonial expansion through diplomatic negotiations that emphasized persuasion within a context of violence. These mechanisms allowed for some cultural hybridity to develop.

Following historian Wayne Lee, this article understands culture in the context of armed struggle as a set of “habits, skills, and styles” collectively practiced over a long time span for decision-making, planning, and action. These collective cultural habits are socially reproduced and taught across generations, transmitting knowledge “through symbols and actions.”Footnote 7 By applying this definition to the province of Sonora, this article endeavors to show that indigenous peoples and Spanish colonizers adopted elements of each other's culture as they consolidated hybrid diplomatic practices. According to Stephanie Wood, while the conquest of Mesoamerican groups in central Mexico involved “forceful native Christian evangelism,” it nonetheless required an initial acceptance and negotiation of both Native and Christian rituals and symbols.Footnote 8

To be clear, accomplishing the missionaries’ goals in the farther north involved indigenous and colonial bloodshed.Footnote 9 But the practice of subduing or settling Indians meant a combination of force and accommodation. Borderlands historians who emphasize indigenous agency have noticed the variety of strategies that indigenous peoples created while navigating colonial rule. Raphael Folsom, for instance, suggests that the colonial pact between the Spanish crown and Indian communities was an “ambivalent relationship” that “intertwined roles of violence and negotiation.” Confronted with colonial force, Native communities often shifted strategically from resistance to collaboration.Footnote 10 According to Cynthia Radding, missionaries interacted with indigenous communities by combining “coercion and persuasion,” while Native peoples chose “negotiation, flight, and revolt” as mechanisms to interact with the colonizers.Footnote 11 Susan Deeds proposes that indigenous peoples interacted with colonial settlers through “mediated opportunism.” They chose “mixed strategies” as they adapted to certain “changing cultural and ecological circumstances” but rejected any changes that would compromise what they considered to be a balanced way of life.Footnote 12 With a stronger focus on religion, Brandon Bayne's recent work highlights how indigenous experiences with colonial religious institutions were shaped by “veneration and coercion.”Footnote 13 Colonial expansion into northern New Spain took many forms, but focusing on the subaltern experience, which is what this article will do, shows that indigenous strategies were central to shaping Spanish colonial practices.Footnote 14

Because of its vast territorial extension and its geographical, ecological, and cultural diversity, most of northern New Spain underwent multiple cycles of military conquest challenged by ensuing Native resistance, including the Mixtón and Chichimec Wars, which together lasted nearly a century.Footnote 15 Native/Spanish interactions were conflictive, and colonial expansion across northwestern New Spain involved, among other things, diplomacy through accommodation based on cultural parallels between Christian and precontact Amerindian symbols and rituals.Footnote 16 Native groups and incoming Spaniards created a hybrid culture as they accepted and incorporated portions of each other's rituals and symbols into their own set of beliefs and customs.Footnote 17 This practice became common in places like Sonora, going as far back as the initial Native/Spanish encounters and the early stage of the mission system.Footnote 18

Peace was unstable, as it needed to be negotiated and sustained through a long process of cultural adoption and exchange that was rooted in sacred objects and practices with multivalent meanings traditionally used to invoke spiritual power and healing.Footnote 19 Native communities and colonial authorities sought their mutual recognition by selectively appropriating each other's beliefs and practices, creating a common ground for communication and trust.Footnote 20 In this historical context, the sign of the cross, combined with other symbols, became a widespread mechanism for initiating peaceful interactions.Footnote 21 Studying the multivalent meanings and uses of crosses during diplomatic endeavors sheds light on the perspectives of colonized peoples and colonizers. It highlights the Natives’ range of action and their strategies for interacting with European settlers, including female indigenous mediation. Ultimately, it provides a more nuanced understanding of colonial expansion in northwestern New Spain.

Crosses, Spanish Reducciones, and Pre-Hispanic Patterns

In early modern Spanish tradition, crosses epitomized a way to mark and understand the world. Crosses represented indigenous populated towns to Spanish colonizers, as attested by the “Christian emblem of the cross” set by the missionaries in many town squares.Footnote 22 Moreover, the 1750s map titled “Hanc Sonora Tabulam” and authorized by Sonora governor José Tienda y Cuervo depicted indigenous settlements (‘Ranchería de Yndios Christianos’) with the symbol of a cross over a pile of stones or an earthen mound.Footnote 23 On the same map, Tienda y Cuervo's mapmaker used tilted crosses to represent unpopulated towns (‘Pueblo despoblado’). Spaniards related the Christian cross with the process of reducción (the establishment of a fixed settlement), which involved founding villages or towns populated by Christian Indians “at peace” with the Spaniards (see Figure 1).Footnote 24 The term reducción came “from the Latin root ‘reductio’ meaning to ‘join’ or ‘gather together.’”Footnote 25 Tienda y Cuervo's map, therefore, underscores the importance of indigenous communities as fixed settlements.

Figure 1 Crosses to Mark Fixed Settlements

Source: Partial images taken from José Tienda y Cuervo's map “Hanc Sonora Tabulam, 1750s,” (undated), Museo Naval de Madrid, AMN.008-B-09.

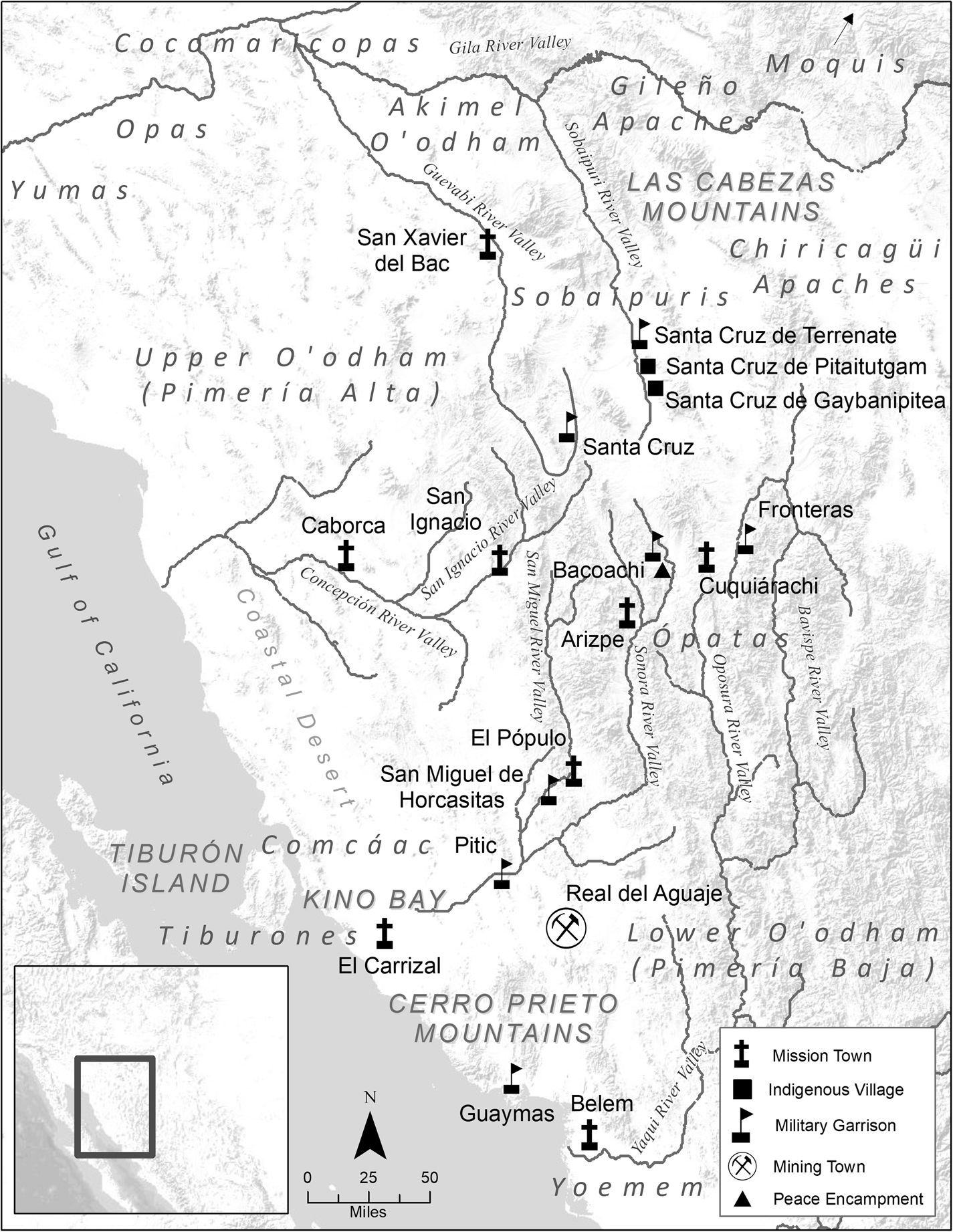

The connection between fixed settlements and peaceful interactions through the sign of the cross is further seen on several Spanish place-names in Sonora, particularly in Sobaipuri territory (see Figure 2).Footnote 26 Missionaries gave some indigenous allied villages the name of Santa Cruz (Holy Cross), with the continuing indigenous name incorporated, such as Santa Cruz de Pitaitutgam and Santa Cruz de Gaybanipitea. Later, the Spanish military used the same name for two garrisons in that area.Footnote 27

Figure 2 The Sonoran Frontier during the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

Source: Map elaborated by Philip McDaniel, from Geographic Information Systems, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, May 3, 2021.

Indigenous peoples in precontact northern Mexico used the sign of the cross but in a different form than Europeans did. Rather than worshipping Latin crosses, they revered equilateral crosses, which I will refer to as Native crosses. This symbol had “nuanced meanings,” but mainly it conveyed different forms of “spiritual power” for ceremonial rites that could protect their communities from diseases, accidents, or enemy attacks.Footnote 28 The Yoemem in southern Sonora, for instance, considered the sign of the equilateral cross as a “sacred” symbol since they “were sun oriented,” and it represented “the cardinal points of the Earth and the center of creation.”Footnote 29 Native crosses were also significant because they ultimately represented and reproduced the four-pattern cult, a widespread custom among precontact societies.Footnote 30 Indigenous peoples in the north performed many rituals and general practices in patterns of four.Footnote 31 For instance, in honor of their prey, the seafaring Comcáac from the coastal desert in central Sonora held a four-day celebration every time they captured a giant turtle. They also used the four-pattern structure during their traditional vision quests, which were expected to last for four days. The Comcáac also made Native crosses with shrub twigs they used as amulets for curing purposes. Likewise, they reproduced this symbol by painting and tattooing it on their bodies to invoke health and protection.Footnote 32

Among agriculturalist O'odham groups from the river valleys in the piedmont, some creation myths highlighted the centrality of the number four as well. For instance, they believed that I'itoi, also regarded as Elder Brother and their creator, had originally caused a great flood because he was angry at his people. According to their belief, water sprouted through a hole in the earth, flooding O'odham territory, and “four children [were] sacrificed” and sent into the hole “to avert that threat.”Footnote 33 Following their creator's arrangement, they used the four-pattern ritual for many of their tasks. Their women tattooed their faces in four-patterns and used elements of four in their agricultural practices; they “dropped in four corn kernels” whenever they cultivated maize. The O'odham people might hear or sing each one of their songs in patterns of four, eight, or even 16 repetitions. Some of their traditional songs and accounts even mentioned the four-pattern and alluded to the four cardinal directions.Footnote 34

The O'odham also used the four-pattern cult in many of their ceremonies, such as marriage rituals and the puberty dance, which was a rite of passage for O'odham women.Footnote 35 Worth highlighting among their rituals is their rainmaking wine festival, called Nawait. In this ceremony, the O'odham drank fermented sahuaro cactus juice until they threw up, which represented the earth absorbing rain moisture, and according to their beliefs, would induce rain. This ritual also required singing that came from “four medicine men [who] sat in [a] circle at north, south, east, and west,” which invoked the form of the Native cross and symbolized the four cardinal points.Footnote 36 The structure of these activities adhered strictly and solemnly to specific patterns and symbols that came together to represent natural and supernatural elements that could convey power and authority, ultimately reproducing the sign of the Native cross.

Hunting and gathering groups from the high mountain ranges, such as the Apaches, traditionally used Native crosses and the four-pattern cult as well. For instance, they believed that they would avoid getting lost when taking an unknown path by painting equilateral crosses on their moccasins.Footnote 37 Among many of their other rituals that involved the sign of the cross were curing practices, cleansing rituals, the puberty dance, and war-related ceremonies for invoking and finding the enemy. Additionally, they used it as part of their ritual when pleading for healers’ services.Footnote 38 Some of these rituals required making the sign of the cross several times by using ashes and pollen.Footnote 39 In practice, these traditions were not that different from the common Christian rituals that involved making the sign of the cross.

The Apaches, specifically, used the Native cross for the snake ceremony, a ritual to cure poisonous snake bites. This ritual required, among other steps, that the healer put pollen on the wounded person “and put it to the directions.” Pollen was also put in the patient's mouth and there was “made a cross of it where he was bitten.” After that, the patient would lie down, and the healer would sit at the patient's side singing, from afternoon to dusk “for four days.”Footnote 40 Some Spanish healing rituals used the Christian cross for similar purposes. For example, during his eight-year epic journey across the North American Southwest in the early sixteenth century, Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca incorporated into his Christian traditions the indigenous healing practices that the Natives taught him along the way. He created a hybrid form of rituals that several indigenous groups later accepted and absorbed into their cultural milieu. Some of the Native healing practices he adopted involved blowing on different body parts for pain relief, incision-making, blood-sucking, and cauterization. Influenced by curing methods of Castilian saludadores (traditional healers), which involved “blessing and breathing upon the patient,” Cabeza de Vaca and his companions “merged Christian and Native rituals as they healed the sick by blowing over them and by cauterizing wounds while also making “the sign of the cross” and praying.Footnote 41 Using cultural parallels among Spanish and indigenous knowledge and belief systems, Cabeza de Vaca's shipwrecked crew became successful and powerful healers.Footnote 42 Comparing these cases suggests that the cultural parallels among Native and Christian crosses used for healing purposes opened the way for hybridized crosses.

Cross-Cultural Exchange and Hybrid Symbols

During Spanish contact, the Native link between their equilateral crosses and the four-pattern cult resembled the colonizers’ link between Christian crosses (Latin crosses) and the Holy Trinity. This parallel became a cultural bridge between the societies that opened the way for diplomatic negotiations.Footnote 43 According to anthropologist James Griffith, there was a “cross-cultural borrowing” between Natives’ ritual number four, considered sacred among several indigenous groups from northwestern Mexico, and the European and Christian significance of the number three as exemplified by the Holy Trinity.Footnote 44 Native groups incorporated Christian crosses as part of their diplomatic rituals and as an extension of their own sanctioned beliefs. Since equilateral crosses were already a sacred symbol to them, it was compatible for them to assimilate the value of the incoming cruciform crosses as symbols of peace that would bring trust and solemnity to their alliances with the Spaniards. Therefore, the adoption of these Christian diplomatic symbols came from negotiated cross-cultural exchanges facilitated by Native/Spanish cultural parallels.

In Sonora, missions arrived before presidios (military garrisons). Thus, the missionaries were among the first consistent groups of European diplomatic emissaries to go into that area and negotiate with the Natives.Footnote 45 The missionaries had two main goals: to Christianize indigenous peoples and to persuade them to go into fixed settlements through the process of reducción.Footnote 46 Since many indigenous peoples of northern New Spain traditionally had “seasonal residence patterns,” going into reducción involved transforming their patterns from semi-sedentary or nomadic into fully sedentary lifestyles.Footnote 47 In theory, this transformation demanded a radical change in Native subsistence practices: seafarers, hunters, and gatherers would fully become agriculturalists and ranchers.Footnote 48 In practice, however, a portion of the people who went into reducciones did so during seasonal visits, incorporating the mission towns as an extension of their seasonal migrating patterns and subsistence practices.Footnote 49 This type of negotiated cultural exchange highlights a blurry line between categories of reduced and non-reduced Indians, suggesting that Indians who limited their interactions with the missionaries to seasonal visits could serve as cultural go-betweens and diplomatic brokers between the people in the mission towns and their brethren in the montes (shrub forests).Footnote 50 Therefore, by analyzing peace negotiations through the hybrid use of crosses, this study focuses thematically on the fluidity in the interactions among Natives and colonizers through cultural exchanges in the examples developed in the following sections.

The cross came to epitomize reducciones and remained as the hallmark for alliances between indigenous communities and priests from Franciscan and Jesuit orders, while Natives and Spaniards merged its symbolism with arches that represented a culturally parallel symbol as well. As several ethnic groups from Sonora interacted with missionaries and received religious indoctrination while going into reducciones during the seventeenth century, they incorporated the Christian cross into their own set of cultural practices and values and used it as a symbol of peace.Footnote 51 For example, in 1694, Upper O'odham bands local to the San Ignacio River Valley welcomed officer Juan Mateo Mange and missionaries Eusebio Francisco Kino and Marcos Antonio Kappus by kneeling along the way with crosses and arches made of branches.Footnote 52 When Kino visited his Sobaipuri allies through seven of their villages along the Guevabi and Sobaipuri Valleys just two years after the O'odham rebellion of 1695, they received him “with crosses and arches placed [along] the road.”Footnote 53 Subsequently, in 1698, Natives from the Concepción Valley received Captain Cristóbal Bernal into their towns in the same manner.Footnote 54

Traditionally, the use of arches had relative parallel meanings among Spaniards and Natives. Reminiscent of Roman arches representing triumph, processional wooden arches became “the most monumental component of the viceregal entry,” since colonial officials received their incoming viceroys in Mexico City with this emblem.Footnote 55 Arches were also a Catholic symbol that represented rainbows, as the Old Testament mentions them as “a sign of God's promise that never again would He send a flood to cover the whole earth.” To the O'odham, and very likely to other indigenous desert dwellers, arches signified rainbows as well, but in contrast, they represented rain that was highly welcomed and desired in an arid environment.Footnote 56 If the depiction of those rainbows looked like the small processional arches elaborated and used by contemporary O'odham, then they must have been “made of branches that [had] been peeled and bent into shape,” and “covered with [many] flowers.”Footnote 57 Since Spaniards understood these Native arches as a sign of welcome, they accepted them as a mechanism for diplomacy, and when combined with Latin crosses, these paired symbols became a quintessential example of Native/Christian diplomatic hybridity.Footnote 58

Crosses beyond Spanish Controlled Territory

By 1699, the sign of the Latin cross had also become widely accepted as a diplomatic symbol for interethnic alliances among several unreduced groups from the Gila River area, beyond Spanish-controlled territory. That same year, Kino sent a cross, a letter, and gifts to the Moqui people in New Mexico to induce them to accept peace and establish an alliance with the Spaniards.Footnote 59 A Sobaipuri chief named Humaric and other members of his group acted as ambassadors. The diplomatic gifts, however, did not arrive at their final destination because a group of Gileño Apaches intercepted and took them as a message for themselves. Through the Sobaipuris, the Apaches sent a request for peace to Kino. As a result, that same year Humaric and others from the Gila River confirmed a peace agreement involving 49 Apaches and Spanish religious authorities. This pact also cemented peaceful relations between Gileño Apaches and other indigenous allies of the Spaniards, such as the Opas, Cocomaricopas, and Akimel O'odham.Footnote 60 Since the Apaches were not closely related to the mission system, this case suggests that non-missionized Indians were adopting these practices and symbols from their indigenous neighbors, underscoring the widespread dissemination of the sign of the cross as a symbol of peace through interethnic cross-cultural exchanges.

Peace by the cross had also become a custom among the Comcáac. In 1700, when Spanish ensign Juan Bautista Escalante visited the mission of El Pópulo, on the ranges of Comcáac territory, their leaders received him by setting “many arches and crosses,” which led to their community house.Footnote 61 These cross-cultural exchanges also extended to unaffiliated Comcáac groups beyond the mission towns. For instance, in August 1709, as Jesuit missionary Juan María Salvatierra visited the Sonoran central coast, he told the local Comcáac bands “that Europeans who . . . honored the cross were men of peace.”Footnote 62 Twelve years later, in May 1721, Jesuit missionary Juan de Ugarte sailed across the Gulf of California from Baja California toward Kino Bay on board a vessel prophetically “blessed” and “Christened” as El Triunfo de la Cruz (The Triumph of the Cross). When he landed, the Comcáac received him peacefully by planting a cross in the sand.Footnote 63

Exchanging Christian crosses as a symbol of peace negotiation became a practice well known during the eighteenth century among several groups beyond Spanish-controlled territory who periodically engaged with the mission system. According to missionary Philipp Segesser's account, written in 1737, several indigenous groups would occasionally seek temporary work within the missions and had their children baptized as they brought them along.Footnote 64 Among the groups in northern New Spain who eventually adopted crosses as diplomatic symbols were the O'odham, Ópatas, Comcáac, Yumas, Cocomaricopas, Moquis, Apaches, and even the Comanches.Footnote 65 The adoption process of this diplomatic ritual among the geographically extended and culturally diverse ethnic groups of northern New Spain provides a glimpse of the role that indigenous peoples had in implanting colonial culture in their own societies, transforming them in the process.

Rebellions, Misunderstandings, and Diplomatic Failures

The introduction and spread of European epidemics among indigenous communities became a reason for rebellion, especially during the early stages of contact. According to historian Robert Jackson, the mission settlement process went through several phases because of the spread of diseases. He claims that permanent agricultural communities existed prior to colonial contact but became depopulated by early epidemics in the region following the Spanish conquest of central Mexico. When the first missionaries arrived in Sonora, they “re-created” these former communities, but the foundation of missions and their congregated lifestyle triggered further spread of disease and decimated them. The missionaries, in response, “repopulated” the missions by bringing in Native groups from further places who seasonally required mission resources to subsist.Footnote 66 However, while many Natives died or fled the missions, others responded to epidemics by choosing rebellion. For example, anthropologist Daniel Reff suggests that in 1616, when news of a smallpox epidemic in Sonora and Sinaloa reached the eastern ranges of the Sierra Madre, the Tepehuan people revolted because their hechiceros (Native sorcerers) advised them to kill all the Spaniards and Jesuit priests in order to avoid punishment through famine and disease.Footnote 67

Because the colonial pact revolved around coercion and accommodation, peace by the cross was generally unstable.Footnote 68 Many Native groups despised colonial rule and life in the missions because of its imposed labor regimes, brutal punishments, and the constant threat of attacks by unincorporated “multiethnic bands” on fixed settlements.Footnote 69 When colonial authorities did not meet the minimum requirements of reciprocity, Indians who had come to accept their presence broke the alliances with them as they chose flight and rebellion over peace as a mechanism “to lessen their burdens . . . and to ransom a part of their dignity.”Footnote 70 Native revolts historically shaped the colonial landscape by showing the vulnerability of Spanish imperial control.Footnote 71 Such was the case with the Ópatas rebelling in 1681, the Yoemem in 1739–41, and the Comcáac in 1749–51. This period also stands out because of the cyclical violence and betrayal between colonizers and indigenous peoples.Footnote 72

Under such unstable circumstances, Christian symbols could be misleading and could serve to attract or distract the enemy. Not long before 1737, the Apaches went to the Fronteras presidio to meet with Captain Juan Bautista de Anza. They “brought with them a cross” to demonstrate “their peaceful intentions.” According to Segesser, they invited Anza “to accompany them to a council, where they wished to swear allegiance to him. Nonetheless, the captain refused because he was unwell at the time, and also because their proposal seemed . . . dangerous [to him].” Under the pretext of bringing the Apaches into Christianity, an unnamed “visiting Spaniard . . . with a few soldiers” is said to have volunteered to go in place of Anza despite “all dissuasion.” The Apaches received them in a friendly manner, but by the time the Spaniard got off his horse, they had killed him and wounded the soldiers, while another group of Apaches simultaneously raided “more than three hundred horses” from the nearby missions of Arizpe and Cuquiárachi.Footnote 73

If the sign of the cross could serve as a distractor, it was because of its extended shared meaning as a symbol of peace that Natives and Spaniards had come to acknowledge by this time. Moreover, this case underscores the role of Indians as historical actors who strategized their interactions with colonizers based on this hybrid symbolism. They could either invoke the peaceful implicit connotations of the cross when seeking to negotiate peace, or they could choose to use it to mislead and gain an advantage over their enemy.

On the other side of the spectrum, Native groups who had established peaceful interactions with colonial authorities had suspicions about trusting their Spanish allies. Even though they had negotiated a particular place for themselves within the colonial pact, they felt threatened and believed that the Spanish would change their prerogatives. Competition among colonizers and mission Indians for natural resources, such as land and water, became a major conflict source, especially during the second half of the eighteenth century under a set of late-colonial economic, political, and military transformations commonly referred to as the Bourbon Reforms. According to Cynthia Radding, the Bourbon Reforms, and Mexican independence later on, created policies that contributed to break the colonial pact that some indigenous groups of northwestern Mexico had negotiated first with Jesuit missionaries, and later with Franciscans. The major issue that brought this rupture was the tendency to prioritize private property against indigenous communal property.Footnote 74

While attempting to promote a stronger, efficient, and more profitable colonial system, enlightened metropolitan authorities put a strain on the colonial pact as their bureaucratic changes became a burden for indigenous communities to bear. In 1748, for example, royal visitor Rafael Rodríguez Gallardo transferred the presidio of Pitic on the fringes of the coastal desert into the San Miguel Valley in the piedmont, near Comcáac and Lower O'odham populated mission towns.Footnote 75 Spanish soldiers displaced the indigenous peoples in places like El Pópulo by encroaching on their mission lands. The Natives protested in reaction, and Spanish authorities suppressed them by arresting 80 Comcáac and Lower O'odham families and deporting their women to Guatemala. With good reason, both groups rebelled and fled El Pópulo and other close-by missions, seeking refuge across Comcáac territory in the rugged mountains bordering the Sonoran coastal plain and on Tiburón Island.Footnote 76

Flight from the missions involved violence against the Spaniards, but it also had religious implications as fugitive indigenous peoples might vandalize church property in the process. For instance, on September 18, 1748, a group of Comcáac raided a Spanish mining camp in central Sonora called Real del Aguaje, where they “killed 43 persons” while they also robbed and “burned the houses.” According to Father Nicolás Perera, the raiders then “desecrated the church,” as they “spilled the holy oils,” and they speared an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe nine times “with infernal fury.” They also took two bundles of rations with them. They used some sacred ornaments as dishware to eat the rations, and when they finished, they burned them.Footnote 77 Thus, Christian ornaments became objects that Natives could use to convey a symbolic language of war.

Peace under the cross, therefore, was tenuous and could be shattered at any given moment. Native people could turn their knowledge and use of the cross against the Spaniards and use it to enforce their view of their relationship with them. In 1756, for example, four Comcáac men were carrying crosses on their way to the presidio of San Miguel de Horcasitas, supposedly to negotiate peace, when they found three unarmed Yoemem transporting fodder. The Comcáac suddenly threw their crosses away, killed the Yoemem, and fled to their traditional stronghold, the Cerro Prieto, comprised of a chain of mountains in central Sonora.Footnote 78 Another event that shows how peace was not always to be brokered by way of the cross took place a year later. As Sonora governor Juan de Mendoza crossed the Gila River Valley tracking down O'odham bands who had fled the missions, he encountered them among the Cocomaricopas, who had allied with them and given them refuge. Both Native groups were on top of a mountain, ready to fight. Mendoza got off his horse, and with his interpreter, advanced to within gunshot range, and “sent them a cross” with a double agenda in mind. He intended the cross to symbolize an “offer of peace” that would also induce the Natives into the “disposition of conquest,” as he claimed. The Indians, however, replied negatively to his request by shooting arrows at the Spaniards.Footnote 79

Peace was not always a given, and this incident illustrates a scenario in which indigenous resistance forced colonial authorities to seek diplomatic alternatives beyond violent means. Despite Mendoza's naive language conveying the idea of peace and conquest as compatible, the fact that he sent the Natives a cross suggests that he was nonetheless aware of his unfavorable position and needed to negotiate peacefully with the fleeing bands. Moreover, this case further highlights indigenous strategies for interacting with colonial officers, since it was the Natives’ choice to accept peace or continue fighting that decided the outcome of this encounter.

Truce by the Cross

Despite the cycles of violence, mistrust, and treachery among Natives and Spaniards that characterized most of the eighteenth century, diplomatic language by the sign of the cross persisted during intermittent moments of peace. Intense conflict among Spaniards and Comcáac escapees from the missions characterized the period that extended from the 1750s to the 1770s. The Comcáac often confederated with other indigenous groups and sought refuge in the Cerro Prieto mountains. During this time, the Spaniards organized recurrent military campaigns and expeditions into this mountainous range with no apparent success.Footnote 80 Peace, nonetheless, was sporadically brokered by the cross.

In 1757, Juan de Mendoza reported, as he prepared for a campaign against the Comcáac, that he had noticed that “many Crosses started to appear, planted in several places along [their] Territory.” For the governor, this constituted part of what he called the “material enigma of requesting peace with humility.”Footnote 81 He toured the Cerro Prieto again, where he found four more crosses, presumably placed in the four cardinal directions. As a positive response to the Comcáac, he turned the symbolism back at them as he decided to plant more crosses in those same places.Footnote 82 For Mendoza, receiving crosses from Indian leaders meant “a very clear petition of . . . holy Catholic faith,” as well as a “faithful and proper sign of vassalage” to the King. He saw the cross as part of an indigenous “garment” in a “remote location” that would serve as “a Door, and foundation for the reducción” of the indigenous peoples of Sonora.Footnote 83 This case underscores Mendoza's acknowledgment of crosses as a Native symbol. Moreover, it shows how the cultural parallels between Native and Christian crosses created a bridge for diplomacy. While each side had its own multivalent perceptions and interpretations of this ritual, in a diplomatic context both sides clearly understood the broader meaning of the sign of the cross, beyond its religious and political connotations, to represent peace through the process of reducción.

In April 1762, an elderly Comcáac woman served as an emissary between Governor José Tienda y Cuervo and Comcáac and Lower O'odham Indians who had allied and fled Spanish settlements seeking refuge in the Cerro Prieto. Carrying a “Santo-Christo” (crucifix), she entered the Comcáac hideaway through the eastern range at the Cajón del Cósari, one of its many narrow canyons.Footnote 84 She eventually contacted Comcáac chiefs Marcos and Chepillo and showed them the cross, explaining to them that “the Governor sent her, to propose a pardon for them if they desired to reduce to the subjection and obedience of the King.”Footnote 85 She further explained that the Spanish governor would supposedly “attend them and help them out of his good heart, and that the same was assured by Father Nicolás Perera, who had given her that Santo-Cristo, so that . . . they would believe that they were being pardoned, as ha[d] been the custom up to th[at] point.”Footnote 86

She encouraged them to trust Spanish authorities and explained that they were safe to come out and negotiate with the governor, who “wanted to accommodate them, give them lands, and good locations, at their pleasure, where they could establish a Town, and live in a Mission, settled and appeased.”Footnote 87 She also extended the same offer to Francisco Siaritaca, a chief among the Lower O'odham, so that he and his people would return to their mission towns. The solemnity of this event is worth telling, as Marcos, in the presence of many of his people, “took the Santo Cristo, and kissed it.” Marcos shared this message with Siaritaca, who replied, “Compadre, I shall do as your mercy does, and with all my People I shall go wherever your mercy goes.”Footnote 88 Their primary concern for accepting peace was “fear and distrust regarding their pardon.” Therefore, among Natives and Spaniards, part of the crucifix's function was precisely to represent a sign of acting in good faith.Footnote 89 As the Comcáac woman was leaving the encounter, Marcos “gave her a Cross made of sticks, which he made himself, and he told her, I will stay with the Santo Christo, that Father Nicolas sends, and as a sign that I want peace, take this Cross, and tell the Governor that we shall not do any harm.”Footnote 90

The cross represented an unspoken covenant between indigenous communities and religious authorities. Because indigenous peoples were prone to mistrust the military, they would rather negotiate peace with the priests. Since fear kept them from coming down the mountains, Marcos further sent Tienda y Cuervo a message through the Comcáac woman, requesting a visit from soldiers so that he and his group could negotiate with them. He stated that he would “meet with his lordship, but that Father Nicolás Perera was to attend so that [they could] reach an accord in his presence.”Footnote 91 According to historian Thomas Sheridan, Nicolás Perera likely knew the Comcáac the best among European settlers.Footnote 92 This case, therefore, reminds us that persuasion was part of the strategies for Spanish colonial expansion in the far north within a context of violence and coercion.

On August 29, 1768, at age 71, Nicolás Perera became the first of 20 priests from Sonora and Sinaloa who died during the controversial Jesuit Expulsion as they were transferred to Mexico City for their exile from the Spanish empire by royal decree.Footnote 93 The 52 Jesuits expelled from this area left a large vacancy, since each of them was responsible for a designated mission and its visiting towns. Replacing them implied the arrival of missionaries from the Colegio de la Santa Cruz de Querétaro (the Holy Cross), who managed to cover eight missions of Pimería Alta and seven of Pimería Baja. In the absence of more missionaries from the Colegio de la Santa Cruz, 11 friars from the Province of San Francisco de Jalisco initially attended the eastern portion of Sonora's missions.Footnote 94 Therefore, the number of priests who could potentially serve as diplomatic mediators was significantly reduced, by half, from 52 to 26. Nonetheless, while Franciscans did not exert the same “methods” and “influence” over Native communities as the Jesuits had, recent scholarly work recognizes “some continuity” under the incoming missionaries. For instance, along the same line as the Jesuits, Franciscans had sway in diplomatic affairs as they promoted and justified Spanish expansion through “new reducciones.”Footnote 95

By the early 1770s, the Spanish military and the Comcáac and Lower O'odham had become exhausted from fighting and engaged in diplomacy by the sign of the cross. While peace negotiations involved the Natives establishing fixed residence, selecting the location was a two-way process that required the mediation of the Franciscan priests.Footnote 96 On April 23, 1770, Spanish officer José Antonio de Vildósola sent an elder Indian woman he had previously taken as a captive to engage in diplomatic negotiations with a group of Sibubapas (Lower O'odham) that was hiding in the Cerro Prieto. Vildósola offered them a pardon if they would establish a camp with their families near the military garrison in Guaymas. He further suggested that “if they had any fear or suspicion to follow through, they could avail themselves of the patronage of Father Don Francisco Joaquín Valdez.” The Sibubapas responded to the offer under their own terms by setting a cross near the mission town of Belem along the Yaqui River Valley on April 29 to accept peace, but also as a request to settle in that mission under the tutelage of Father Valdez rather than in Guaymas with the soldiers, as they had originally been ordered to do.Footnote 97 This case illustrates that peace by the cross had come to epitomize reducciones and missionaries for indigenous people. It reasserts the relevance of the priests’ mediation and the Natives’ mistrust or disdain for the Spanish military.

The two previous cases show that female mediation was crucial. In some instances, captive indigenous women became avid negotiators who brokered diplomacy among their people in exchange for their freedom. Nonetheless, they were not always successful because of the coercion, mistrust, and interference from third parties. In May 1769, for instance, an unnamed O'odham woman taken captive by the Spaniards requested permission from Juan de Pineda, governor of Sonora, to act as a diplomatic emissary between Spanish authorities and her people hiding in the Cerro Prieto mountain range. After mediating among the runaway O'odham for several days, she returned in the company of Francisco, her husband. Francisco presented himself to Pineda, kneeling on the ground, trembling, and carrying a small cross while assuring the governor that three O'odham leaders, Guejuriche, Vipitzi, and Sicubac, along with their relatives, desired to present themselves in peaceful terms.

After sharing the good news, Francisco anxiously requested the immediate release of his wife, two sisters, and daughter. As a precedent, he mentioned a previous case, where captive Comcáac members had successfully negotiated their release by collaborating as peace brokers among their people. Since the negotiation process was not over yet, Pineda responded by giving him limited access to visit his daughter. Because of the governor's halfway concession, Francisco became unwilling to negotiate any further and took a more aggressive stance by escaping to the Cerro Prieto two nights later with his child and the rest of his captive family members.Footnote 98

This case highlights the importance of women's roles in diplomatic practices. Had Francisco not intervened in the ongoing negotiation, his wife might have successfully secured a peaceful resolution for some of the fleeing bands and could have opened the way to release for her and her captive family members by agreeing to reestablish themselves in reducciones. Nonetheless, Francisco's intervention shows that indigenous peoples could balance their power when diplomacy failed by resorting to other strategies, such as flight from Spanish settlements.

Crosses under Military Rule

Because of the escalation of violence and Apache raids from the mid eighteenth century, by the late colonial period Bourbon policies increased military support in northern New Spain.Footnote 99 A set of royal regulations for military garrisons on the northern frontier was in effect by September 1772, establishing an offensive strategy against unsubdued Indian groups.Footnote 100 These regulations added significant pressure to indigenous communities not subject to colonial rule, because they were now more vulnerable to attacks in their own villages.Footnote 101 In this context of coercion, the Comcáac and other groups became more prone to request peace by seeking the mediation of missionary priests, and the sign of the cross persisted as an essential mechanism for diplomacy, as the following case will show.

On January 1773, a Comcáac subgroup known as the Tiburones received Lieutenant Manuel de la Azuela and Franciscan friar Juan Crisóstomo Gil de Bernabé into their territory along the coast in a place known by the Spaniards as El Carrizal. By holding “crosses in their hands,” the Tiburones ratified their “obedience” to Spaniards, requesting missionary presence in that location.Footnote 102 Colonial authorities granted their request, but months later, the newly established mission failed, apparently because of inter-band rivalries, with Gil's life taken at the hands of the Tiburones.Footnote 103 Despite the deplorable outcome, this case illustrates how Natives could negotiate their residence locations when going into peace agreements and assert power over their territory even after the peace negotiations. It also highlights that the sign of the cross continued to have a fundamental diplomatic function, since it provided at least an initial avenue for negotiations between Natives and priests, even after the Jesuit Expulsion and the enactment of the royal regulations of 1772.

On August 26, 1786, Viceroy Bernardo de Gálvez issued a policy that emphasized diplomacy through military efforts by promoting peace negotiations with Indians who were to settle on peace reservations in the proximity of military garrisons.Footnote 104 The first of these encampments was in Bacoachi, a mission and mining town in northern Sonora. Established by the Jesuits in 1650 under the place-name of Jesús del Valle de La Paz (Valley of Peace) in what was once an Upper O'odham village, Bacoachi by this time also housed a Spanish presidio manned by Ópata auxiliary troops who were traditional enemies to the Apaches.Footnote 105 Peace negotiations between colonial authorities, their indigenous allies, and non-reduced Indians were still celebrated through hybrid cultural practices revolving around the sign of the cross.

On November 19, 1786, at Las Cabezas Mountains, several Southern Apache bands celebrated a peace agreement with Spanish officers following a Native ritual that bridged indigenous and Christian values and portrayed multilayered meanings regarding the cross as a symbol of peaceful interactions. At the event were Captain Chiquito, prominent leader of a subgroup known as the Chiricagüi, and another chief who represented the Gileño Apache faction and a portion of the Tonto people. An Apache shaman was also present. The ceremony started with Chiquito shouting to gather his followers, and as they came all together, he asked them to surrender their weapons. Next, the Apaches started moving closer to the Spaniards, and as they got about 30 feet from them, Captain Chiquito “stood and sighed.” His people “started singing a chant as if they were weeping, and he and his son started trembling, and then came two of his daughters covered with a blue cloth, they stood about ten steps behind, crying and trembling.” Next, Chiquito's son, and “heir to the Captaincy,” came out dressed in white.

[He entered] trembling and twirling in the form of the cross until he got dizzy and needed to lean on one of the persons who was singing. Then Captain Chiquito came along twirling in the form of the Cross as well, and in this way he came into [the Spaniards’] Sphere and after being among [them] he raised his hands towards the sky and he lowered them three times. To this signal, the Captain of the Tontos yelled and said that Captain Chiquito [was] now good, and he came to greet all [the Spaniards], and then the whole group of warriors, as well as the Women and Children, [with] their weapons, mingled with [them], and the Captain remained standing and trembling until his dizziness faded away, he then sat [and started his speech].Footnote 106

This case illustrates in detail that the Southern Apaches continued to revere the Native cross and the four-pattern ritual, since the act of twirling in the form of the cross suggests that they were invoking the four sacred directions. Twirling in that fashion was a recurrent practice in Southern Apache rituals, including their main ceremony, the puberty dance. In this celebration, running “around the four ways” was done to invoke the power of one of their deities, Changing Woman.Footnote 107 Spanish commander Domingo Vergara, who recorded this ritual, likely acknowledged it as an indigenous tradition, but its resemblance to the sign of the Christian cross evidently served as a cultural bridge for diplomacy.

The Apaches, in fact, successfully merged the multilayered symbols of both Native and Christian crosses and continued using them during diplomatic rituals even after Mexican independence. In 1836, for instance, an Apache woman went into the town of Santa Rita, New Mexico, carrying a “large wooden cross which she turned round and round, exhibiting it in all directions.”Footnote 108 This incident exemplifies the hybridity between Christian and Native rituals that came through a long process of cross-cultural exchange and negotiation among indigenous groups and colonial people. It suggests the longevity and multivalent meanings of enduring symbols like the Native and Christian crosses revolving around peace negotiations, which indigenous groups and European settlers had developed and preserved throughout Spanish colonial contact and beyond.

Conclusion

Peace came to represent a variety of things among indigenous peoples and European settlers. To Spaniards, it meant living by the Cross and under the authority of Christian doctrine, and it represented spreading Christianity and colonial rule among indigenous groups across the Americas. These goals implied changing indigenous beliefs, subsistence practices, and lifestyles by bringing semi-sedentary or nomadic peoples into reducciones, epitomizing the sign of the Latin cross. While the colonizers certainly did not meet all their goals, they could exchange and negotiate some of these meanings and intentions with the Natives by engaging in diplomatic ceremonies that required them to accept indigenous symbols and rituals. To Natives, peace with Spanish authorities meant accommodating some Christian symbols and rituals within their precontact ceremonies and practices. Following traditions based on reciprocity, they incorporated the colonists into their former interethnic exchanges and alliances, cementing these diplomatic strategies by adopting Christian symbols and merging them with their extended Native cultural systems. As this article has shown, the O'odham and Comcáac groups practiced diplomacy through the hybrid use of arches and crosses in the final years of the seventeenth century and the first years of the eighteenth. Similarly, by the late colonial and early national periods the Apaches practiced rituals that involved both Latin and Native crosses.

By studying the hybrid uses of crosses and the meanings attached to them, this article has focused on fluidity in the interactions among Natives and colonizers through the adoption of this symbol by ethnic groups beyond Spanish-controlled territory. The emphasis on the adoption process of this diplomatic ritual among the geographically extended and culturally diverse ethnic groups of Sonora and beyond provided insight into the role indigenous peoples had in implanting colonial culture in their societies, transforming them in the process. Ultimately, the focus in this article on cross-cultural exchanges based on hybrid symbols such as the sign of the cross illustrates native peoples’ reactions and strategies under colonial presence. It shows that the multivalent meanings of the sign of the cross provided indigenous groups with, depending on circumstances, both an instrument to bring trust into their diplomatic negotiations and a weapon to attract and deceive their enemies. Therefore, by following peaceful and conflictive interactions among Natives and Spaniards through this symbol, it has been possible to show some of the options available to these groups. Their choices often involved female indigenous mediation during peace negotiations, highlighted in some of the examples.

This article has shown a long and nuanced historical process of colonial expansion that intertwined coercion and negotiation. Within a context of violence, Native groups and incoming settlers found a common cultural ground through parallel symbols such as crosses, which served them in solidifying their diplomatic endeavors. The cross came to represent an unspoken covenant between indigenous communities and Spanish authorities, especially with the missionaries, occasionally allowing for colonial expansion through persuasion within a context of military might or religious imposition. It also highlighted the persistence and endurance of indigenous culture, which survived the transformations enacted by the Bourbon Reforms and extended beyond the colonial period.