Introduction

Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP) is a therapeutic modality that addresses the relevance of spiritual well-being and the role of meaning in face of an existential crisis. It is a short-term intervention with robust evidence of efficacy, developed by William Breitbart (Breitbart, Reference Breitbart2002; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Gibson2010, Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2015; Applebaum et al., Reference Applebaum, Kulikowski and Breitbart2015; Da Ponte et al., Reference Da Ponte, Santo and Santos2018b). MCP was developed to help patients with advanced cancer to sustain or enhance a sense of meaning, peace, and purpose in their lives, even in the end of life (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Gibson2010, Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2015; Applebaum et al., Reference Applebaum, Kulikowski and Breitbart2015; Van der Spek et al., Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-Kraan2016; Da Ponte et al., Reference Da Ponte, Santo and Santos2018b).

Breitbart et al. highlighted the central role of meaning as protective against depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2000, Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Gibson2010, Reference Breitbart, Poppito and Rosenfeld2012; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Rosenfeld and Breitbart2002; McClain et al., Reference McClain, Rosenfeld and Breitbart2003; Da Ponte et al., Reference Da Ponte, Santo and Santos2018b). Also, patients who experience a stronger meaning after a cancer diagnosis have a higher psychological well-being, less distress, and better adjustment and quality of life (QoL) (Tomich, Reference Tomich2002; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Cohen and Edgar2004; Lee, Reference Lee2008; Park et al., Reference Park, Edmondson and Fenster2008; van der Spek et al., Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-Kraan2013, Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-Kraan2016; Devoldre et al., Reference Devoldre, Davis and Verhofstadt2015; Da Ponte et al., Reference Da Ponte, Santo and Santos2018b).

MCP is mainly grounded on Viktor Frankl's work (Spiegel and Bloom, Reference Spiegel and Bloom1981; Frankl, Reference Frankl1992; Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Bloch and Smith2003; van der Spek et al., Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-Kraan2016; Da Ponte et al., Reference Da Ponte, Santo and Santos2018b). For Frankl, human beings have the freedom to find meaning in their existence and to choose their attitude facing suffering (Frankl, Reference Frankl1975, Reference Frankl1992; Breitbart, Reference Breitbart2002; van der Spek et al., Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-Kraan2013; Applebaum et al., Reference Applebaum, Kulikowski and Breitbart2015; Da Ponte et al., Reference Da Ponte, Santo and Santos2018b). Meaning, or having a sense that life has a meaning, involves the conviction that one is fulfilling a unique role and purpose in a life that comes with a responsibility to live up to one's full potential (Breitbart, Reference Breitbart2002).

MCP was first developed in a group format (Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy — MCGP) in 2002. It is a manualized eight-week intervention with 1.5-h sessions, which utilizes a combination of experiential exercises and discussion focused around meaning and advanced cancer (Breitbart, Reference Breitbart2002). The first randomized control trial evidenced benefits in enhancing spiritual well-being and a sense of meaning that persisted, which may have grown, after treatment ended (Breitbart, Reference Breitbart2002). Further studies suggested that more severe forms of despair may respond better to existential approaches (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2015).

Individual MCP (IMCP) emerged in Breitbart et al. (Reference Breitbart, Poppito and Rosenfeld2012) to avoid attrition in the group format. IMCP follows the same framework of MCGP, and it had shown efficacy in improving spiritual well-being, a sense of meaning, overall QoL, physical symptom distress, anxiety, and desire for hastened death (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Poppito and Rosenfeld2012, Reference Breitbart, Pessin and Rosenfeld2018). However, IMCP showed no significant differences at the 2-month follow-up, which may reflect the unique benefits of a group-based intervention in this population, such as a sense of universality and belonging, a feeling of helping oneself by helping others, and seeing how others have coped successfully (Breitbart, Reference Breitbart2002; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Poppito and Rosenfeld2012).

After the expansion of MCP for advanced cancer and in the assumption that MCP was applicable for a human being facing suffering, other versions were developed.

MCP for Cancer Caregivers (MCP-C) emerged in Applebaum et al. (Reference Applebaum, Kulikowski and Breitbart2015) to address existential concerns experienced by cancer caregivers. Evidence showed its efficacy especially in prolonged grief disorder (Breitbart, Reference Breitbart2002; Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Krisjanson and Hack2006; Applebaum et al., Reference Applebaum, Kulikowski and Breitbart2015, Reference Applebaum, Buda and Schofield2018; Da Ponte et al., Reference Da Ponte, Santo and Santos2018b). Applebaum et al. (Reference Applebaum, Buda and Schofield2018) adapted MCP-C for a self-administered web-based program as a way to provide a flexible support program; this modality had a potential to improve the sense of meaning and purpose among caregivers and to protect against burden (Antoni et al., Reference Antoni, Lehman and Kilbourn2001; Applebaum et al., Reference Applebaum, Buda and Schofield2018).

van der Spek et al. (Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-Kraan2013, Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-Kraan2014) adapted MCGP for Cancer Survivors (MCGP-CS), with the goal of sustaining (or enhancing) a sense of meaning or purpose to cope better with cancer consequences (Tedeschi and Calhoun, Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun2004; Ussher et al., Reference Ussher, Kirsten and Butow2005; Henoch & Danielson, Reference Henoch and Danielson2009; van der Spek et al., Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-Kraan2013, Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-Kraan2014). MCGP-CS proved to be effective in improving personal meaning, psychological well-being, and mental adjustment in cancer survivors in the short term and in reducing psychological distress and depressive symptoms in the long term (van der Spek et al., Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-Kraan2016).

Meaning-Centered Grief Therapy for parents who had lost a child was developed by Lichtenthal and Breitbart (Reference Lichtenthal and Breitbart2015); meaning reconstruction was the key to help manage prolonged grief symptoms. Studies supported its feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness (Neimeyer, Reference Neimeyer2000; Lichtenthal, Reference Lichtenthal2010; Lichtenthal et al., Reference Lichtenthal, Applebaum and Breitbart2011, Reference Lichtenthal, Currier and Keesee2013, Reference Lichtenthal, Catarozoli and Masterson2019; Lichtenthal and Breitbart, Reference Lichtenthal and Breitbart2015).

MCP-palliative care was developed by Rosenfeld et al. (Reference Rosenfeld, Saracino and Tobias2017) as a brief intervention for enhancing meaning at the end of life (LeMay, Reference LeMay2008). The pilot study showed its feasibility and acceptability, and the potential to help cope better with the challenges of confronting death and dying (Rosenfeld et al., Reference Rosenfeld, Saracino and Tobias2017).

Vos and Vitali (Reference Vos and Vitali2018) conducted a meta-analysis to determine the effects of MCP on improving QoL and reducing psychological stress; this study revealed that immediate effects were larger for general QoL than for meaning in life, hope and optimism, self-efficacy, and social well-being and that increases in meaning in life predicted decreases in psychological stress.

Da Ponte et al. (Reference Da Ponte, Ouakinin and Breitbart2017) adapted the MCGP manual to Portuguese. The difficulties raised were about the comprehensibility of existential issues and “meaning” (of life), which seemed culturally determined. The pilot study of MCGP validation to the Portuguese language showed several dropouts, which could jeopardize the feasibility of the study, so the authors adapted MCGP to a four session version (Table 1). Preliminary results demonstrated benefits in increasing spiritual well-being and QoL and in decreasing depression and anxiety (Da Ponte et al., Reference Da Ponte, Ouakinin and Breitbart2018a).

Table 1. Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy — four sessions version (duration: 1.5 h; weekly periodicity)

The goal of the present article is to analyze the content of an MCGP-4 session version, carried out in a Portuguese sample, to:

• identify what was easier to reach for the participants, or which topic the psychotherapy may have more influence;

• understand the process of MCGP itself, in particular, the possible association between the techniques and any therapeutic changes.

Methods

The study was conducted in the Oncology Unit of Centro Hospitalar Barreiro-Montijo, after the approval of the Institutional Ethical Committee, and the Portuguese National Commission of Data Protection, in accordance with the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Adult cancer patients who reported distress to their oncologist were informed that they could participate in a psychotherapy validation study (MCGP), with the goal of reducing distress. The inclusion criteria were motivation to participate and cognitive capacity to understand informed consent, evaluated by the psychiatrist who conducted the study and who was also the therapist.

The MCGP-4 session version adapted to the Portuguese language (Table 1) was performed, and each group had a mean of five participants. Although the recording of the sessions was approved by the ethical committee, the therapist chose to transcribe the sessions for reasons of a therapeutic relationship.

The narrative analysis was done using the Edwards (Reference Edwards2016) methodology, based on Lieblich and Tuval-Mashiach's (Reference Lieblich and Tuval-Mashiach1998) The Narrative Research Analysis to establish the categories and dimensions as well as to understand the process of MCGP itself, particularly the possible association between the techniques and therapeutic changes. The qualitative analysis was done to assess any associations among the different categories (Figures 1 and 2). The descriptive analysis was done of the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics.

Fig. 1. Qualitative analysis framework of MCGP sessions (apsychiatrist and psychologist).

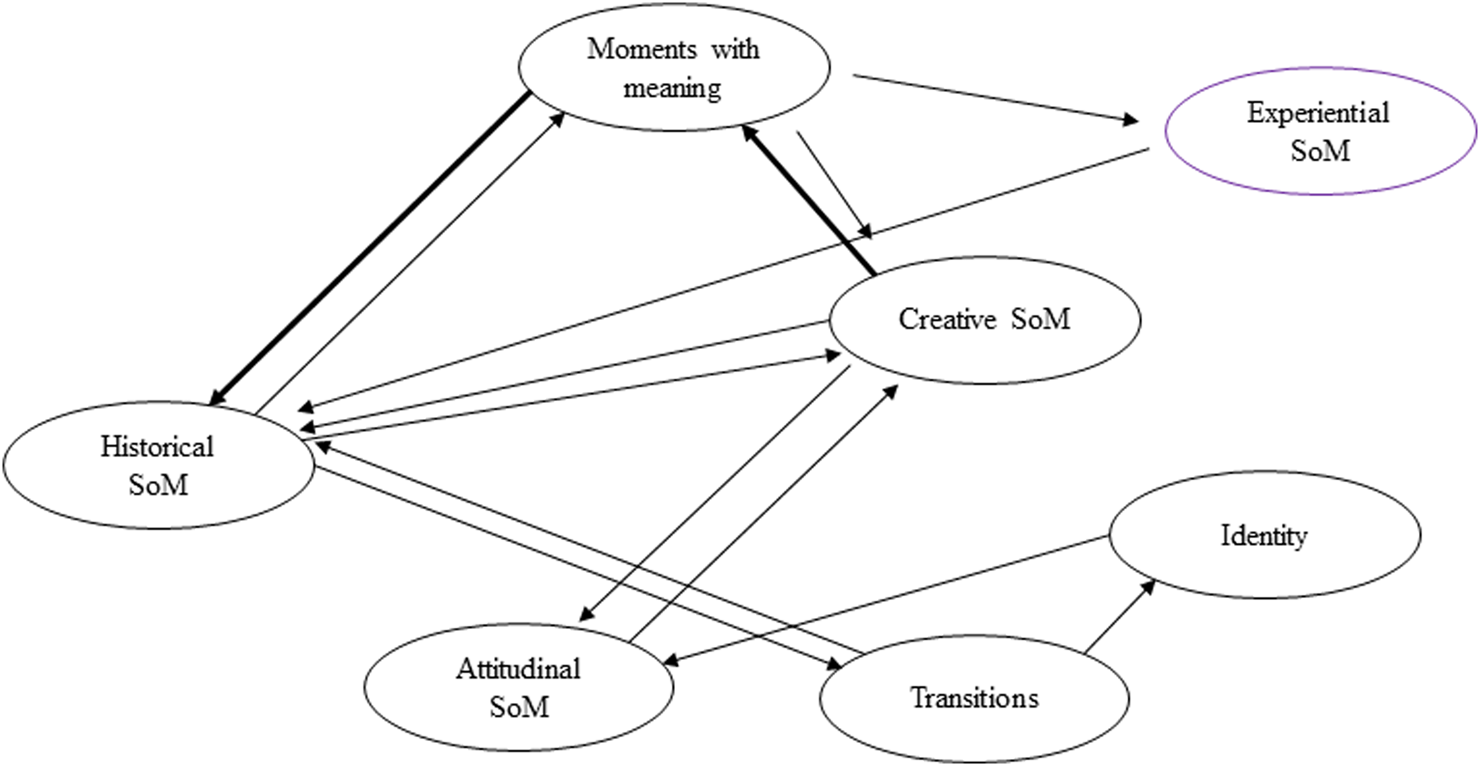

Fig. 2. Patterns established between categories (the bold line means that the relation occurred twice between categories; SoM: sources of meaning).

Results

The sample had 24 participants (Table 2), with a mean age of 63.43 years. Most of the participants were female (n = 18; 75%), with a median academic degree (high school: 54%); the majority were retired (79%) and married (62%).

Table 2. Sample socio-demographic and clinical characterizations

CT: chemotherapy; HT: hormonal therapy; n/a: not applicable; RT: radiotherapy

Breast cancer was the most frequent (16 cases; 67%); of all participants, 71% had localized cancer, 83.33% were assigned to surgery, and 58.33% to chemotherapy (CT).

62.5% had a personal psychiatric history, and 70.83% were, at the time of the study, under psychiatric/psychological follow-up. The main reasons for follow-up were anxiety (34%) and depression and anxiety (25%), as described by the participants.

The framework of MCGP, in which each session had a specific theme, gave an opportunity to build the narrative analysis (Table 3) according to the sessions’ themes; seven categories were defined: 1. Moments with meaning (MwM); 2. Identity before and after cancer diagnosis, 3. Historical sources of meaning (SoM), 4. Attitudinal SoM, 5. Creative SoM, 6. Experiential SoM, and 7. Transitions. In each category, dimensions were defined, which, in some categories, corresponded to sessions' sub-themes (2.1. Identity before cancer, 2.2. Identity after cancer; 3.1. Past legacy, 3.2. Present and future legacy; 4.1. Attitude in face of past limitations, 4.2. Attitude in face of limitations since cancer diagnosis; 5.1. Courage, 5.2. Responsibilities; 5.3. Unfinished issues; 6.1. Love, 6.2. Beauty, 6.3. Humor; 7.1. Life project, 7.2. Changes in seeing life and illness, 7.3. Better understanding of the SoM, 7.4. Hopes for the future). When the themes or sub-themes of the sessions were developed, they were then assigned topics — according to the Edwards (Reference Edwards2016) methodology — into categories: 1. MwM, 2. Identity before and after cancer diagnosis, 3. Historical SoM, and 6. Experiential SoM. The relationship pattern established among the different categories is shown in Figure 2.

Table 3. Narrative analysis of MCGP session content

a Sessions' themes.

b Sessions' sub-themes.

c Topics.

Category 1 — moments with meaning

In this category, 10 dimensions emerged (Table 3): 1. wedding, 2. births, 3. deaths in family, 4. illness diagnosis in the family, 5. war, 6. family moments, 7. moments with friends, 8. pets, 9. the moment of cancer diagnosis, and 10. personal achievements.

The most discussed dimensions were “births,” “illness diagnosis in family,” “family moments,” “moments with friends,” “the moment of cancer diagnosis,” and “personal achievements.” In dimensions “births” and “moments with friends,” the participants gave examples of positive experiences, remembering “the miracle” of birth and “laughing with friends.” In “moments in family,” they shared the feeling of being “the only one,” as being valued by those they love, and the support they received in moments of fragility, like those after cancer treatments. The dimension “impact of an illness diagnosis in the family” was described as an intense moment of suffering, as important or more than the moment of the diagnosis of their own cancer — “when my son was diagnosed with cancer” — or as a moment of happiness when family members recover. Another dimension that raised some powerful sentences was “the moment of cancer diagnosis”: “it was like I was waiting for something bad, and when I had the diagnosis, I was relieved”; “someone had told me that I had asked to have cancer; maybe I had.” In “personal achievements,” the examples reflected goals reached, such as the first trip to New York, or gaining financial independence. The dimensions “wedding,” “war,” and “pets” were less explored, but they were described as moments of responsibility, to others or itself, and love.

In terms of patterns of relations, the category “MwM” established relationships with almost all other categories, particularly with the category “historical SoM” (Figure 2). In fact, the relation with this last category was established more than once, showing the importance of this pattern. MwM were present when participants shared their “childhood” (dimension “past legacy” — category “historical SoM”) and “achieved goals” and “values to pass to others” (dimension “present and future legacy”) (Table 3). MwM were also present in the categories “creative” and “experiential SoM.” In the first, the relation is bilateral and, inclusively, occurred more than once; when participants shared their marriage or going to war, these were also moments of “responsibility” and “courage.” The relation with “experiential SoM” was established when participants shared their moments of “love” for family or pets or experiencing the “beauty” of “nature.”

Category 2 — identity before and after cancer

Identity before and after cancer diagnosis was divided into dimensions “identity before cancer diagnosis” and “identity after cancer diagnosis” (Table 3). In the dimension “identity before cancer diagnosis,” there were two main topics that emerged: what the participants felt as their “positive” and “negative characteristics” before cancer. In “positive characteristics,” participants described themselves as “normal, cheerful, being in a good mood, without financial or family problems” or “someone at peace with life.” As “negative characteristics,” they mentioned their difficulty in living life to its fullest, as “a person that doesn't have time for anything” or “I overvalued things and I was always anxious.” In “identity after cancer diagnosis,” there were two topics that, although they were not time consuming, generated negative feelings — what participants felt as cancer negative consequences in their personality (“negative changes”) and in their body (“focus on the body”), considering themselves as “more depressed, more pessimistic and more nervous than before; less independent, less active.”

But, the topics most present were “the identity remains” and “value what really matters,” as participants felt that “I didn't change, the fundamental is here but with some physical changes” or “nothing has changed, just my health”; “I'm the same person, but I value life more; now I have time for myself” and “I learned to enjoy every day.”

Identity before and after cancer only established relations with “attitudinal SoM” and “transitions” (Figure 2). When participants shared “identity before” (“negative characteristics”) and “after cancer diagnosis” (“the identity remains” and “value what really matters”), they were also exploring their “attitude in face of limitations before and after cancer diagnosis”; when participants shared their “life project” and “changes in seeing life and illness” (category “transitions”), they were referring to “identity before and after cancer.”

Category 3 — historical sources of meaning

Historical SoM had two dimensions, according to the session content: “past legacy” and “present and future legacy” (Table 3). In the dimension “past legacy,” the topics mainly explored were “family relations” and “childhood,” as participants remembered the love and care they received, independently of adverse conditions — “my childhood was hard … I had to start working early to help at home”; “my parents got a divorce when I was 6 years old.” Other topics explored, but without the same importance, were “traditions,” “education,” and “family name” — participants shared moments of spending Christmas with family, the transmission of values like respect and solidarity, and the transmission of their name from one generation to another. In the dimension “present and future legacy,” the two main topics were “achieved goals” and “values to pass (to others),” with the examples being the goal of being a good parent or a competent professor, and transmission of values such as integrity and respect, to their children and grandchildren.

Historical SoM were similar to MwM, as it was a category with many interactions (Figure 2), establishing relations with the categories “MwM,” “creative,” and “experiential SoM” and “transitions.” The dimension “past legacy,” namely the topic “childhood,” constituted “MwM,” such as the dimension “present and future legacy,” especially the topic “achieved goals”; this last dimension, on the other hand, was related to “responsibility,” in “creative SoM.” Categories “historical” and “experiential SoM” were connected by the dimension “love” (“experiential sources”) that was present on “past legacy” (historical SoM) — topics “family relations,” “traditions,” or “family name.” The dimension “present and future legacy,” namely the topic “values to pass,” was related to dimensions “life project” and “changes in seeing life and illness” in the category “transitions.”

Category 4 — attitudinal sources of meaning

In “attitudinal SoM,” the two main dimensions (Table 3) were “attitude in face of past limitations” and “attitude in face of limitations since cancer diagnosis.” In terms of “past limitations,” the most frequent examples were family deaths and separations, and financial losses: “my divorce was the most horrible thing that happened to me”; “I have had serious economic difficulties; I was alone and I had to start all over again.” In terms of “attitude in face of limitations since cancer diagnosis,” participants shared the effort “to play with the situation (cancer),” while others embraced new projects, such as trying painting classes, “I thought that I couldn't do so many things … to devalue obstacles and finding solutions.”

Attitudinal SoM (Figure 2) established relations with the category “creative SoM,” through its dimension “identity before and after cancer diagnosis.”

Category 5 — creative sources of meaning

In “creative SoM,” moments of “courage” and “responsibility” were the main dimensions (Table 3). Participants shared moments in life when they needed to have “courage” to “be the mother of a child with ADHD,” “take the driving license test” or to make hard decisions, e.g. “going to the Navy,” or “to ask for a divorce and knowing that I would raise my daughters alone.” In “responsibility,” participants shared the responsibility to their children, pets, and also for themselves and their disease. The third dimension, “unfinished issues,” was less explored but nonetheless mentioned examples of wishes of traveling.

In terms of patterns established, “creative SoM” was an important category, relating especially to “MwM,” and also to “historical” and “attitudinal SoM” (Figure 2). The dimension “courage” was present in the dimension “past legacy” of “historical SoM” when participants described their childhood memories. The dimensions “courage” and “responsibility” were present in participants’ life decisions or in their personal achievements. Courage was also present in “attitude in face of past limitations and since cancer diagnosis,” in category “attitudinal SoM.”

Category 6 — experiential sources of meaning

In experiential SoM, dimensions were classified according to the session content, in “love,” “beauty,” and “humor” (Table 3). Love and beauty were more prominent in terms of relationships, topics emerged of “family love,” “pets,” and “religion.” In “beauty,” the main examples were related to nature, as “listening to the sea; the smell of flowers in the spring.” The dimension “humor” was not as explored, but some participants considered that “dark humor is the best; I joked about the catheter (for CT), calling it a little bomb.”

Experiential SoM were related to “MwM” and “historical SoM” (Figure 2). The most frequent dimension of this category was “love” that was present in moments of love for family, friends, or pets, and in traditions or family name (dimension “past legacy” — category “historical SoM”).

Category 7 — transitions

In this category, the most important dimensions were “changes in seeing life and illness” and “hopes for the future” (Table 3). In the first, participants reflected how MCGP helped them “to live life to its fullest” and the benefits of identifying themselves with other group members, feeling that there they are not alone. In “hopes for the future,” all participants had the “hope to live more years.” Dimensions “life project” and “better understanding and use of the SoM” were not so explored. Life project examples were “making a photo album” or “to be at peace and not to have conflicts.”

Transitions were related to categories “historical SoM” and “identity before and after cancer diagnosis” (Figure 2). Life project was a dimension that, by its nature, was related to the “past, present and future legacies” (historical SoM). The dimension “changes in seeing life and illness” (transitions) established a connection with “identity before and after cancer diagnosis,” especially in its dimension “to value what really matters.”

Discussion

The perception of both mental and physical disability and their diagnostic value strongly vary in different social and cultural groups (Kim and Schulz, Reference Kim and Schulz2007; Sutkevičiūtė et al., Reference Sutkevičiūtė, Stančiukaitė and Bulotienė2017). In our study, examples of “MwM” were the socially expected norms (i.e. “wedding,” “births,” or “deaths in family”).

In the dimension “identity after cancer diagnosis” (category “identity before and after cancer diagnosis”), some participants felt like cancer caused “negative changes” in their personality, which, after the psychotherapeutic work, turned out to be “value what really matters.” Despite this, there was a difficulty to change the association between physical capacity (focus on the body) and personality as, for some of the participants, the body was their identity. This was also reported in the study of Leng et al. (Reference Leng, Lui and Huang2019), which described the main changes occurring post diagnosis: “shift in occupational goals, physical pain, physical appearance, and a shift from independence to dependence and interdependence.”

Gil et al. (Reference Gil, Fraguell and Benito2018) studied the new issues that arose when applying adapted MCGP to Spanish-speaking advanced cancer patients (Fraguell et al., Reference Fraguell, Limonero and Gil2017). The “emergent themes” were classified as threat, benefit of group therapy, sadness, uncertainty, loss of social role, and the importance of a patient's current routine (Gil et al., Reference Gil, Fraguell and Benito2018). The most widespread feeling verbalized by participants was threat, which overlapped with the study of van der Spek et al. (Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-Kraan2013) in Dutch patients, where “threat to identity” was one of the main factors related to meaning. In the case of our study, “threat to identity” was approached in a superficially way in “identity before and after cancer.”

Creative SoM established a pattern between its dimension “courage” and the category “MwM,” given that most examples of moments of life with particular meaning were moments of courage. The other finding was in the dimension “responsibility,” where participants felt responsible for themselves and their disease, in accordance with the westernized model of patient autonomy (Leng et al., Reference Leng, Lui and Chen2018).

In conformity to others studies, as in ours, it was easy for participants to provide examples for “experiential SoM” when asked to list three ways in which they connect with life, namely through the sources of love and beauty (van der Spek et al., Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-Kraan2013; Fraguell et al., Reference Fraguell, Limonero and Gil2017; Leng et al., Reference Leng, Lui and Chen2018). In the dimension “love,” the theme of religion came up as participants reported their relationship with God — this can be explained by the Portuguese catholic culture (Table 2).

In the category “transitions,” the sharing of experiences with other participants who are coping with the same illness supports the benefit of the model of identification in group therapy (Breitbart, Reference Breitbart2002; Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Grabsch and Clarke2007; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Poppito and Rosenfeld2012, Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2015; Limonero et al., Reference Limonero, Tomás-Sábado and Gómez-Romero2014; Fraguell et al., Reference Fraguell, Limonero and Gil2017).

As already mentioned, the patterns established among the categories (Figure 2) were very clear; “MwM” and “historical SoM” were essential themes for participants. The authors interpret this finding, considering that these categories imply a concrete way of thinking and, therefore, simple to understand; also, it was evident that the dimension “past legacy,” in “historical SoM,” gave an opportunity to share effortlessly and, in the majority, pleasant memories. Basically, it was around these two categories that psychotherapy worked. Another example was the dimension “courage” of “creative SoM,” which used moments from the “past, present, and legacies” (historical SoM) and “limitations before and after cancer diagnosis” (category “attitudinal SoM”) as mechanisms for reaching and/or enhancing meaning. However, other studies have shown different results. Fraguell et al. (Reference Fraguell, Limonero and Gil2017) and Rosenfeld et al. (Reference Rosenfeld, Cham and Pessin2018) demonstrated strong evidence that improvement due to MCGP is mediated by the acceptance of cancer diagnosis and prognosis, despite the sense of a crisis that often accompanies the knowledge of these aspects. Lethborg et al. (Reference Lethborg, Kissane and Schofield2019) investigated the therapeutic processes used in Meaning and Purpose therapy (Lethborg et al., Reference Lethborg, Schofield and Kissane2012), a type of psychotherapy with focus on meaning, and possible associations between the intervention and therapeutic changes; the common patterns emerged showed an increase focus on meaning and, at the same, a decrease on suffering. Although this cannot be directly compared to the results of our study, it is evident the similarity to our patterns of association between the categories “MwM” and “historical SoM” and all the other categories.

Although one of the limitations of this study can be the narrative analysis itself, because it used the session themes as categories and sub-themes as dimensions, this has decreased the subjectivity of codification and further diminished by the multi-layered analytical task carried out by both participants and therapist and independent contributors. Another limitation of this study was the use of the qualitative analysis to establish the relations among the categories; however, due to the diversity of variables, the use of the quantitative analysis would be impossible.

Our narrative analysis concluded that “MwM” and “historical SoM” were more impactful for the participants, constituting the MCGP processes of changes in our Portuguese sample. However, the authors point out that these results are certainly influenced by the Portuguese culture, which is inclusively supported by the conclusions of MCGP adaptation to the Portuguese language (Da Ponte et al., Reference Da Ponte, Ouakinin and Breitbart2018a), as well as the vast literature about the influence of the culture on the concept of “meaning” of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognize the collaboration of Ofélia da Ponte, Family doctor, MD, Family Health Unit Golfinho, Faro, Algarve Administration of Health, Portugal; Humberto Santos, General Practitioner, Family Health Unit Castelo, Sesimbra, Portugal; and Joana Gomes, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Doctor Nélio Mendonça, Funchal, Portugal.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.