‘From the Monkey Mountains’ is the title of a string quartet written in 1925 by the Czech composer Pavel Haas (1899–1944), who lived and worked in Brno, Moravia, where in the early 1920s he studied with Leoš Janáček. This piece is commonly regarded as a turning point in the young composer's career, one which singled him out within the group of Janáček's students. Václav Kaprál, Vilém Petrželka and Osvald Chlubna (to name but the most important members of this group) built in their contemporary chamber works less upon Janáček's latest works than upon the pre-war tradition of Czech high-art music, represented by Antonín Dvořák's disciples Vítězslav Novák and Josef Suk.Footnote 1 Haas, by contrast, combined salient features of Janáček's compositional idiom with avant-garde tendencies that emerged during and after the Great War.

Such an assessment of the significance of Haas's quartet appears in Lubomír Peduzzi's seminal monograph about Haas and in a number of derivative sources, but a more detailed contextualization or critical interpretation of the work is nowhere to be found.Footnote 2 Peduzzi's work, despite its undeniable historiographical value, is marked by some serious methodological limitations. Relying on the old-fashioned notion of linear influence between individual artists, Peduzzi sought to locate Haas in the history of twentieth-century music as a representative of Janáček's compositional ‘school’ whose stylistic development was informed by an illuminating encounter with the music of Stravinsky.Footnote 3 Not only did Peduzzi leave the nature of both composers’ influence largely unexplained, but by attempting to bridge the apparent gap between local tradition (Janáček) and international development (Stravinsky) he also obscured the question of Haas's relationship with the ‘middle-ground’ context of Czechoslovak arts and culture of the time.

In this article, I will relate Haas's quartet to the notion of ‘Poetism’, which dominated Czechoslovak avant-garde discourse in the 1920s. Although I will not undertake a detailed comparative analysis with contemporary French avant-garde discourse, substantial parallels will become apparent to readers who are familiar with the latter. I suggest that the discourse of Poetism played an essential mediating role, enabling Haas to draw on ideas and tendencies similar to those that underpinned the music of Les Six and Stravinsky.

The interpretative framework I use in my reading of the work includes as its cornerstones, besides Poetism, the related notions of the body (or, more broadly, physicality), the grotesque and carnival. Carnival is a particularly characteristic topos of Poetism, the significance of which I will discuss through cultural-critical perspectives of Mikhail Bakhtin (1895–1975). To illustrate the roles played by each of the above in Haas's music, I will use three movements of the quartet as case studies: the first (‘Landscape’), the second (‘Carriage, Horseman and Horse’) and the fourth (‘The Wild Night’). The ‘slow’ third movement, ‘The Moon and I’, which is marked by a contemplative and intimate character, will not be discussed at length, because it is least relevant to the issues scrutinized here. However, I will argue that this movement is complementary to the carnivalesque features of the quartet and that, in this respect, its role in the piece is analogous with that played by contrasting sections within the other movements.

Poetism

The notion of Poetism was introduced in the early 1920s by the avant-garde theorist Karel Teige (1900–51) and the poet Vítězslav Nezval (1900–58), the leading figures of the Prague-based left-wing avant-garde group of artists known as Devětsil.Footnote 4 There were strong links between Brno (where Haas lived) and Prague, the home of Devětsil. As a result, the group expanded from Prague to Brno in 1923, where its members edited the journal Pásmo (1924–6), in which many of their key texts were published.Footnote 5 Other activities of Devětsil in Brno included the organization of art exhibitions, lectures and social events.Footnote 6 Further evidence of Haas's contextual and conceptual affinity with Poetism will be provided over the course of this study.

In the opening of his 1924 manifesto of Poetism, Teige announced (as avant-garde movements typically did) a breakup with preceding artistic tradition and an assertion of ‘new’ art. He argued that art must no longer be the dominion of professionals, tradesmen, intellectuals and academics. The new art, he believed, would be cultivated by ‘minds that are less well-read but all the more lively and cheerful’; it was supposed to be ‘as natural, charming and accessible as sports, love, wine and all delicacies’, so that everyone could take part in it.Footnote 7 Teige's critique of artistic ‘professionalism’ was essentially that of the gap between (old) ‘art’ and ‘life’, which Poetism sought to bridge in order to achieve an interpenetration of the two. Art was supposed to be abolished through its dissolution in life. Teige was eager to make clear that Poetism was not intended to be just another artistic ‘-ism’, but a life perspective, a ‘modus vivendi’, ‘the art of living, modern Epicureanism’.Footnote 8 Its artistic manifestations were supposed to offer noble amusement and sensual stimulation, ‘invigoration of life’ and ‘spiritual and moral hygiene’.Footnote 9 Teige implied that art could help transform human life into the state of ‘poiesis’ (‘supreme creation’).Footnote 10 Thus, all people would eventually become artists in the way they lived their ‘human poems’:

Happiness resides in creation. The philosophy of Poetism does not regard life and a work [of art] as two distinct things. The meaning of life is a happy creation: let us make our lives a work [of art, a creation], a poem well organized and lived through, which satisfies amply our need for happiness and poetry.Footnote 11

The art that strived for fusion with everyday reality, that abandoned galleries and museums, heading for the streets and peripheries of modern cities and aiming to appeal to the crowds necessarily made no distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ artistic regions. It comprised, as Esther Levinger noted, ‘all human activities, whether writing love letters, doing acrobatics, gardening, or cooking’, and even work, which would ‘resemble artistic activity by being free and gamelike’.Footnote 12 Therefore, Poetism, in terms of both form and content, drew on popular urban culture. It sought its sources in circuses, variety shows and cabarets with clowns, acrobats and dancers; in the cinema, offering a hitherto unseen magnificent spectacle; in cafés, bars and music halls, where one could hear jazz and dance to modern popular music; and in the streets and public spaces, regarded as the parade of modern society.

Teige's views on art were underpinned by Marxist materialism. The ‘new’ art was not to be metaphysical, transcendent, ‘high’, elitist, complicated, speculative and intellectual. On the contrary, it should be earth-bound, empirical, sensual, popular, accessible and entertaining. Hence the preference for ‘low’ art forms, which, unlike the dead fossils of ‘old’ art, were (or so Teige believed) throbbing with life. Poetism's shift of emphasis towards everyday experience was paralleled by the abolition of boundaries between body and spirit, by recourse to corporeality and sensuality: ‘Poetism liquidates the discord between body and spirit, it knows no difference between bodily and spiritual art, between higher and lower senses. Here the Christian and ascetic dictatorship of spirit comes to an end.’Footnote 13

Teige thus reclaimed for art the right to appeal to the body. Therefore, strong emphasis was laid on human sensual experience. Quoting Teige's article ‘Pozor na malbu’ (‘Beware of Painting’), Levinger argues:

The Devětsil artists endeavored to arouse an awareness of everyday experience that represented the merger of art and life. They imagined that they could reawaken and reeducate the senses so that people could fully enjoy all sensory data – all sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and touches – but especially sight, for art was all around them, in ‘colorful flowerbeds, posters, flags, road signs, sports clothes, the colored animation of dancing halls, popular festivities, and fairgrounds […] ballet, film, games of reflections, fire-works, parades, and carnivals’.Footnote 14

Teige's understanding of human sensuality was broad enough to include the category of ‘corporeal and spatial senses (a sense of orientation, speed, spatial-temporal movement)’, which comprised ‘sport and its various kinds: automobility, aviation, tourism, gymnastics, acrobatics’.Footnote 15 Teige continues:

The hunger for records, inherent in our mentality, is satisfied by athletics, the passion of victory bursts out in football matches together with the joy of teamwork, with the feeling of tensive harmony, precision and coordination. The poetry of sport, shining above the instructional and orthopedic tendencies of physical education, develops all senses, it yields a pure sensation of muscular activity, the pleasure of bare skin in the wind, the beauty of physical exaltation and intoxication of the body.Footnote 16

This quotation illustrates eloquently the emphasis Poetism laid on corporeality, physical culture and sports. Such celebration of the body, youth and physicality stems from the negation of what was seen as the anaemic spirit-dominated art and culture of the past, aiming to restore the harmony of body and spirit.Footnote 17 When extolling the virtues of the body, Teige invokes the characteristic features of the modern industrial age, such as speed, dynamism, functionality, precision and so on. Bodily health is thus correlated not only with mental hygiene, but also with industrial expansion and technological progress.

Because of its association with dance, music is very well suited for appealing to the body. Of all musical parameters, rhythm is most directly correlated with bodily motion. It follows that music informed by Poetism would be emphatically rhythmic. It was largely owing to its rhythmic vivacity that ‘jazz’ was so popular among the artists of Devětsil. The composer and theatre director Emil František Burian (1904–59) described jazz as an art born of ‘the joy drawn from movement and lively rhythm’.Footnote 18 This common view of jazz was underpinned by equally widespread stereotypical assumptions about its ‘Negro’ progenitors: ‘Dance and dance again is the basis of the spiritual life of these primitives. One could say they live through movement.’Footnote 19

Teige himself seldom referred specifically to music. However, as early as 1922 he co-authored, along with the less well-known Devětsil-affiliated composer Jiří Svoboda (1900–70), an article entitled ‘Musica and Muzika’, which effectively brought into Czech discourse the essential ideas articulated in Jean Cocteau's 1918 manifesto Le coq et l'arlequin.Footnote 20 Like Cocteau, Teige and Svoboda employed iconoclastic, anti-academic rhetoric. The Latin term ‘musica’ in the title refers to the music supposedly marked by the academicism, snobbism and elitism of pre-war arts and culture, while its vernacular counterpart ‘muzika’ denotes the music of ‘the people’.Footnote 21 ‘Muzika’ can be heard ‘in the café, in the restaurant, in the cinema, on the street, in the park, in the Sunday dance hall, at the Salvation Army parade’ or at sports events;Footnote 22 it is ‘passionate, […] richly colourful, strongly moving, […] emotional, and immediately appealing’;Footnote 23 its genres include ‘ragtime, jazz band, […] foxtrot, shimmy, exotic music, couplet [popular song], cake-walk, music in cinema [and] operetta’.Footnote 24 Music of the future, the authors believe, should draw on these rejuvenating resources. Drawing on his own area of expertise, Teige asks: ‘Why should music resist new, academically unsanctioned instruments – jazz band, accordion, the barbarian barrel organ, etc. – when architecture happily makes use of the advantages of modern materials?’Footnote 25

Teige and Svoboda invoke French avant-garde composers as the pioneers of this new direction. Erik Satie is introduced as an influential ‘comedian, humourist, and primitivist’.Footnote 26 Stravinsky is celebrated for his ‘love of the vulgar and the profane’ which made him ‘lead modern music […] towards exoticism in its modern, cosmopolitan sense’.Footnote 27 Georges Auric is described as a lover of ‘musical caricature’ who seeks all that is ‘grotesque and merry’, and as the author of the ‘modernist foxtrot Adieu, New York! as well as other pieces that could be played on a barrel organ’.Footnote 28 Arthur Honegger and Darius Milhaud are also briefly mentioned. In the article's conclusion, the authors lament the ‘conservatism, foolishness and narrow-mindedness’ of Czech critics, who ‘a priori reject such music […] fearing its bold innovations’.Footnote 29

‘From the Monkey Mountains’: reception and Haas's commentary

The critical reception of Haas's quartet at its première is a fine example of the conservative critics’ hostility towards the anti-academic features of ‘Western’ avant-garde style.Footnote 30 The elements of ‘low’, popular music (‘muzika’ rather than ‘musica’) in Haas's work were all the more striking since they clashed with the expectations set by the genre of the string quartet, traditionally associated with ‘high’ art, seriousness and refinement. This clash was further exacerbated in the last movement, when the string ensemble was joined (as if in response to Teige's call for the use of modern instruments) by a percussion set – the hallmark of contemporary ‘jazz bands’.Footnote 31 Many were also dismayed by Haas's use of tone-painting, which was described in terms of ‘caricature’, the ‘burlesque’ and the ‘grotesque’, and perceived by some as the mark of the influence of contemporary ‘international’ or ‘Western’ music (note that the same characteristics were used by Teige and Svoboda with reference to Auric).Footnote 32

It is noteworthy that, despite the chauvinistic undertone of some reviews, no hostility was directed towards Haas himself and there was no mention of his Jewish origin, a factor that was used by French conservative critics against musicians like Milhaud and Jean Wiéner, and that later proved fatal to Haas during the time of Nazi occupation.Footnote 33 National identity was not an issue, since Haas – unlike many Jewish artists and intellectuals in Czechoslovakia at that time – was unambiguously Czech in terms of language, as well as cultural and professional affiliations.Footnote 34 As a recent graduate of Janáček's compositional masterclass, Haas was seen as a young talent, promising to advance the Moravian compositional tradition. Thus, most critics recognized his musical gifts, but his work was nonetheless dismissed as ‘modish’, ‘tasteless’ and ‘unscrupulous’.Footnote 35

In anticipation of the concert, which featured Haas's quartet alongside works by Kaprál and Chlubna, the journal Hudební rozhledy (Musical Outlooks) published short commentaries on each of the pieces. Haas began his own commentary as follows:

The title of the quartet comes from the colloquial name of the Moravian locality in which this composition arose. Although the movements are given programmatic titles [‘Landscape’; ‘Carriage, Horseman and Horse’; ‘The Moon and I’; ‘The Wild Night’], this is not for the sake of some kind of painting, as the listener might easily think. I simply intended to capture several strong impressions evoked by a light-hearted summer vacation in the country. […] I could have entitled the movements plainly with Roman numerals and supplemented those with Italian tempo markings. I did not do that, however, because I wanted to confess openly the actual source of my inspiration and thoughts to the listener.Footnote 36

These claims make clear that – contrary to the expectations of the chamber-music genre – Haas was not writing a serious piece of high art intended exclusively for expert audiences. This work was to be ‘light-hearted’ in character, and its inspiration was very much earth-bound. It should be pointed out that leisure-time activities were a typical source of inspiration for Poetism, and that travel, trips and postcards were among its most characteristic topics, repeatedly exploited in poems and photo collages.Footnote 37

Yet at times the proclaimed rural inspiration is brought into question by elements suggestive of an urban context. This is particularly the case with the last movement (‘The Wild Night’), which, as one reviewer described it, is marked with ‘the atmosphere of a bar’.Footnote 38 These issues will be explored later; suffice it here to say that Haas avoided mentioning other, more urban sources of inspiration. Whether or not the composer had spent his summer holiday in the ‘Monkey Mountains’, it is arguable that he chose this term – once familiar in the patois of Brno – for the title of his quartet to give it a humorous, slightly subversive ring, conjuring up as it does the common association of monkeys with mockery, cheekiness and pulling faces.Footnote 39 In this sense, the title encapsulates the vernacular, grotesque features of the work, which will be discussed below.

The decision to avoid ‘Roman numerals and […] Italian tempo markings’ and use ‘programmatic titles’ instead advertises the piece's anti-academic character and accessibility to the audience. However, Haas seems rather apologetic about the programmatic element. It is not easy to see what he means by claiming that he did not aim at ‘some kind of painting’. Considering the slightly derogatory undertone of this formulation, it is possible that Haas wanted to distance himself from the aesthetic context of Romanticism or Impressionism, with which tone-painting could be associated. Haas later made his position somewhat clearer by claiming that ‘the programme helps greatly to create contrasts and escalations, thus determining the piece's formal structure [and] facilitating the creation of purely musical features’.Footnote 40 This implies that the programmatic or pictorial element is treated with a high degree of abstraction and that it is ultimately subordinate to the considerations of ‘pure music’. This explanation sounds plausible as far as the first movement (‘Landscape’) is concerned. However, some of the other movements (especially ‘Carriage, Horseman and Horse’) are much more overtly pictorial. Again, I suggest, the composer is trying to divert attention away from the more controversial features of his work – in this case the use of ‘caricature-like’ and ‘grotesque’ elements within the rarefied genre of the string quartet.

Haas's commentary also betrays a considerable emphasis on physical movement and sensuality – both of which are musically conveyed by (and correlated with) rhythmic devices. Having stated that ‘movement governs throughout this light-hearted composition’, the composer went on to suggest that the sensual impressions which had inspired the piece had some kind of rhythmic identity:

Whether it is the rhythm of a broad landscape and birdsong, or the irregular movement of a rural vehicle; be it the warm song of a human heart and the cold silent stream of moonlight, or the exuberance of a sleepless night of revelry, the innocent smile of the morning sun …, after all, it is movement that governs everything. (Even the deepest silence has its own motion and rhythm.)Footnote 41

Finally, Haas explained that the use of the percussion set (‘jazz’) in the last movement was ‘neither self-serving nor unnatural’ since it was ‘firmly bound up with the original conception of the piece, which culminates rhythmically and dynamically in its last movement’.Footnote 42 This justification plays down the association of ‘jazz’ with contemporary dance music and modern urban popular entertainment as a whole. In subsequent performances (Prague, 1927; Brno, 1931), the composer had the work played without the percussion part. To my knowledge, there is no archival evidence as to the reasons behind this decision. Nonetheless, Peduzzi argued that ‘the composer […] refrained from the use of the percussion set not so much in response to the critics as in the interests of practicality of performance’.Footnote 43

Rhythms of ‘Landscape’: a Janáčekian perspective

Perhaps the most interesting point made by Haas in his commentary is that concerning the significance of rhythm. He argued that the sensual, pictorial and emotional impressions that had inspired the piece were somehow articulated by means of rhythm, giving rise to a specific dynamic trajectory that is an essential element of the piece's formal design. The apparent emphasis on rhythmic and dynamic categories (those elements which play the most important role in the bodily perception of music, ensuring its direct sensual appeal) is consistent with the Poetist concept of ‘poetry for the senses’. At the same time, however, Haas arguably echoed the ideas on rhythm held by his mentor Janáček.

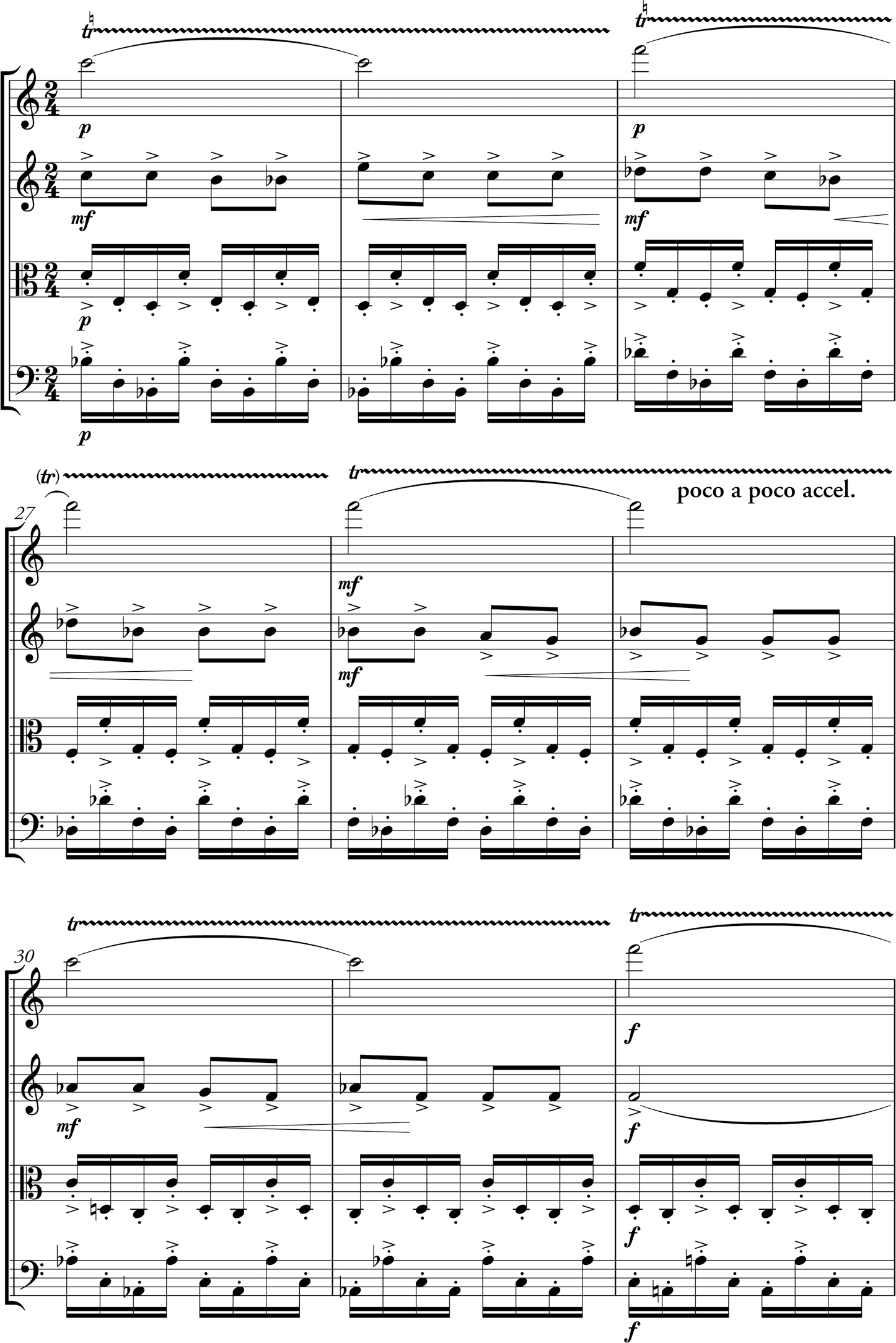

In his theoretical writings, Janáček suggested a theory of metro-rhythmical relations, which he referred to as sčasování (literally ‘in-time-putting’).Footnote 44 One of the most characteristic features of Janáček's theory is the concept of hierarchically organized ‘rhythmic layers’ (sčasovací vrstvy; see Figure 1).Footnote 45 Importantly, Janáček's concept of sčasování had psychological connotations. In his view, each layer was endowed with a specific ‘mood’. There is a striking similarity between the statements Haas made in his commentary and the italicized passage in the following quotation from Janáček's ‘Úplná nauka o harmonii’ (‘Complete Theory of Harmony’):

I have arrived at the significance of sčasování through the study of speech melodies. […] The ultimate sčasovací truth resides in words, the syllables of which are stretched into equal beats, a pulse which springs from a certain mood. Nothing compares to the sčasovací truth of the rhythms of words in [the flow of] speech. This rhythm enables us to comprehend and feel every quiver of the soul, which, by means of this rhythm, is transmitted onto us, evoking an authentic echo in us. This rhythm is not only the expression of my inner spirit, it also betrays the impact of the environment, the situation and all the mesological influences to which I am exposed – it testifies to the consciousness of a certain age. We can feel a fixed mood clinging to the equal beats [i.e. the pulse] of sčasovka [a noun referring either generally to a ‘sčasovací layer’ or, more specifically, to a recurring rhythmic pattern].Footnote 46

Figure 1. Janáček's model ‘sčasovací layers’ stemming from a semibreve ‘sčasovací base’. Leoš Janáček, ‘Můj názor o sčasování (rytmu)’ (‘My Opinion of Sčasování (Rhythm)’), Teoretické dílo: Články, studie, přednášky, koncepty, zlomky, skici, svědectví, 1877–1927 (Theoretical Works: Articles, Studies, Lectures, Concepts, Fragments, Outlines, Testimonies, 1877–1927), ed. Leoš Faltus et al., 2 vols. (Brno, 2007–8), ii/1 (2007), 361–421 (p. 393).

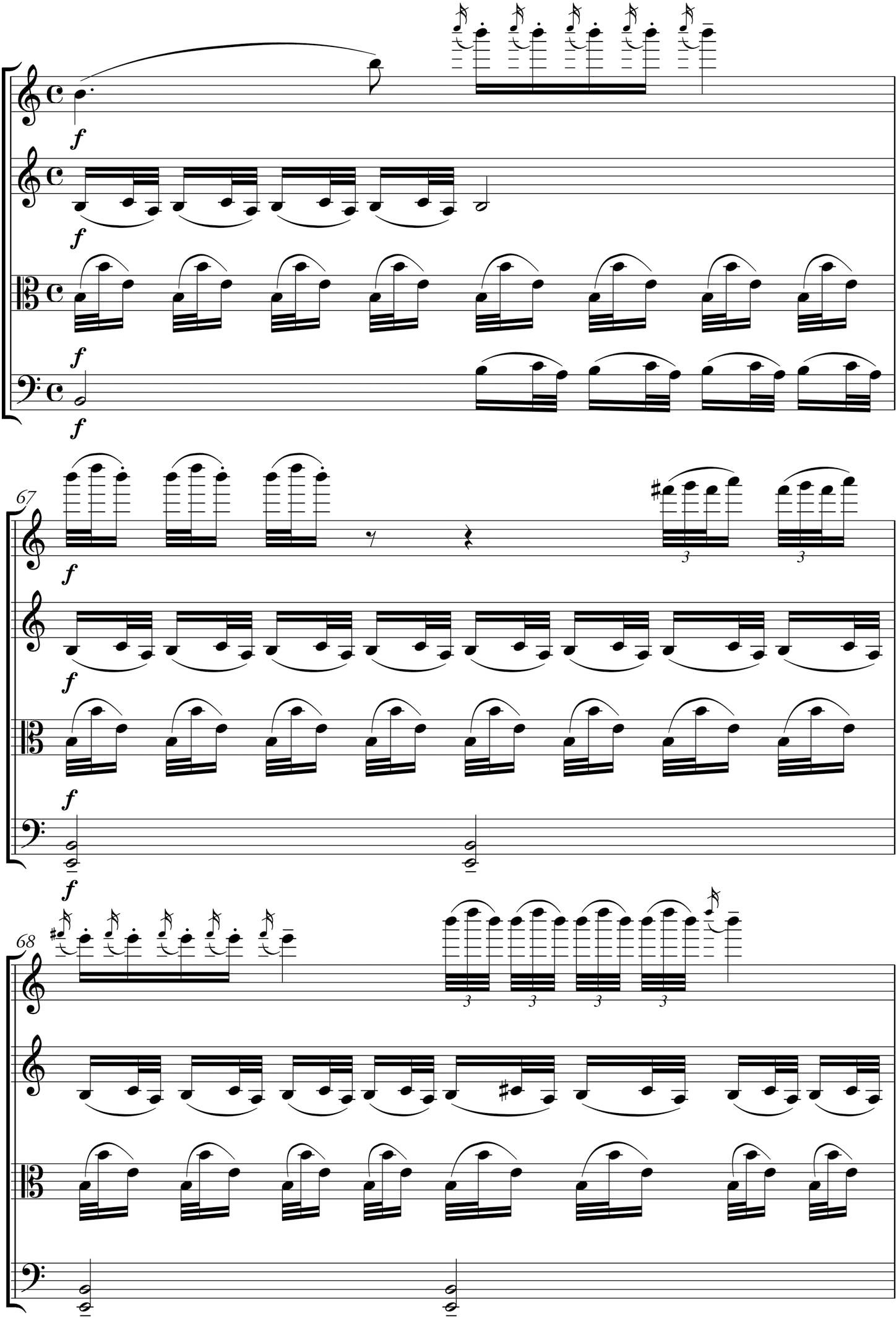

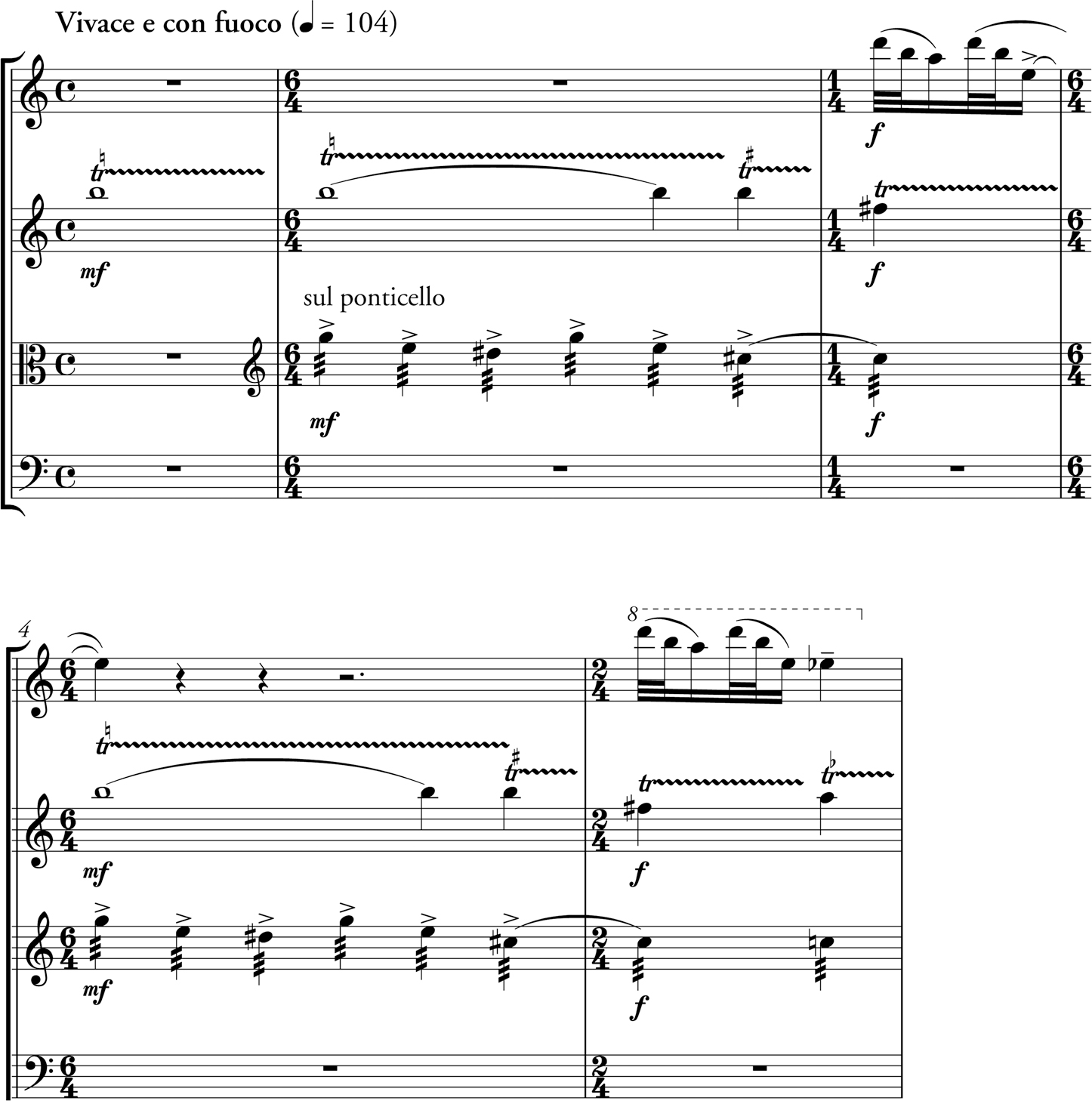

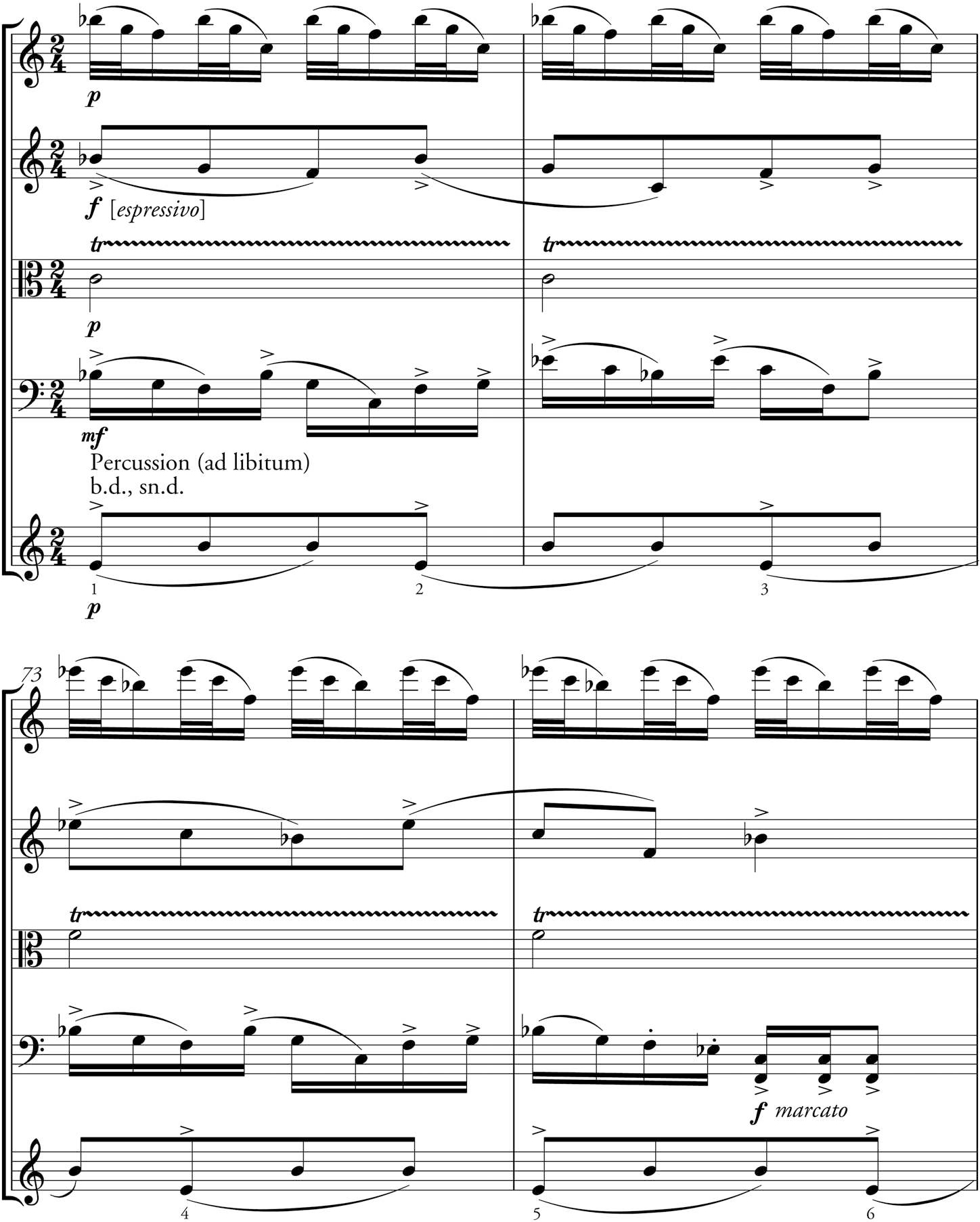

Janáček's notion of rhythmic layers also manifests itself in his compositional practice. Example 1 illustrates Janáček's typical use of stratified textures, consisting of superimposed melodic and rhythmic layers, as well as the strategy of ‘transposing’ fragmentary and repetitive motivic material ‘higher’ or ‘lower’ across the rhythmic strata. Some theorists have used the term ‘montage’ to describe Janáček's technique of manipulation with fragmentary musical material.Footnote 47 ‘Vertical’ montage, based on superimposition and resulting in textural stratification, has already been described. ‘Horizontal’ montage refers to the juxtaposition of discontinuous stretches of musical material, following one another without transition.

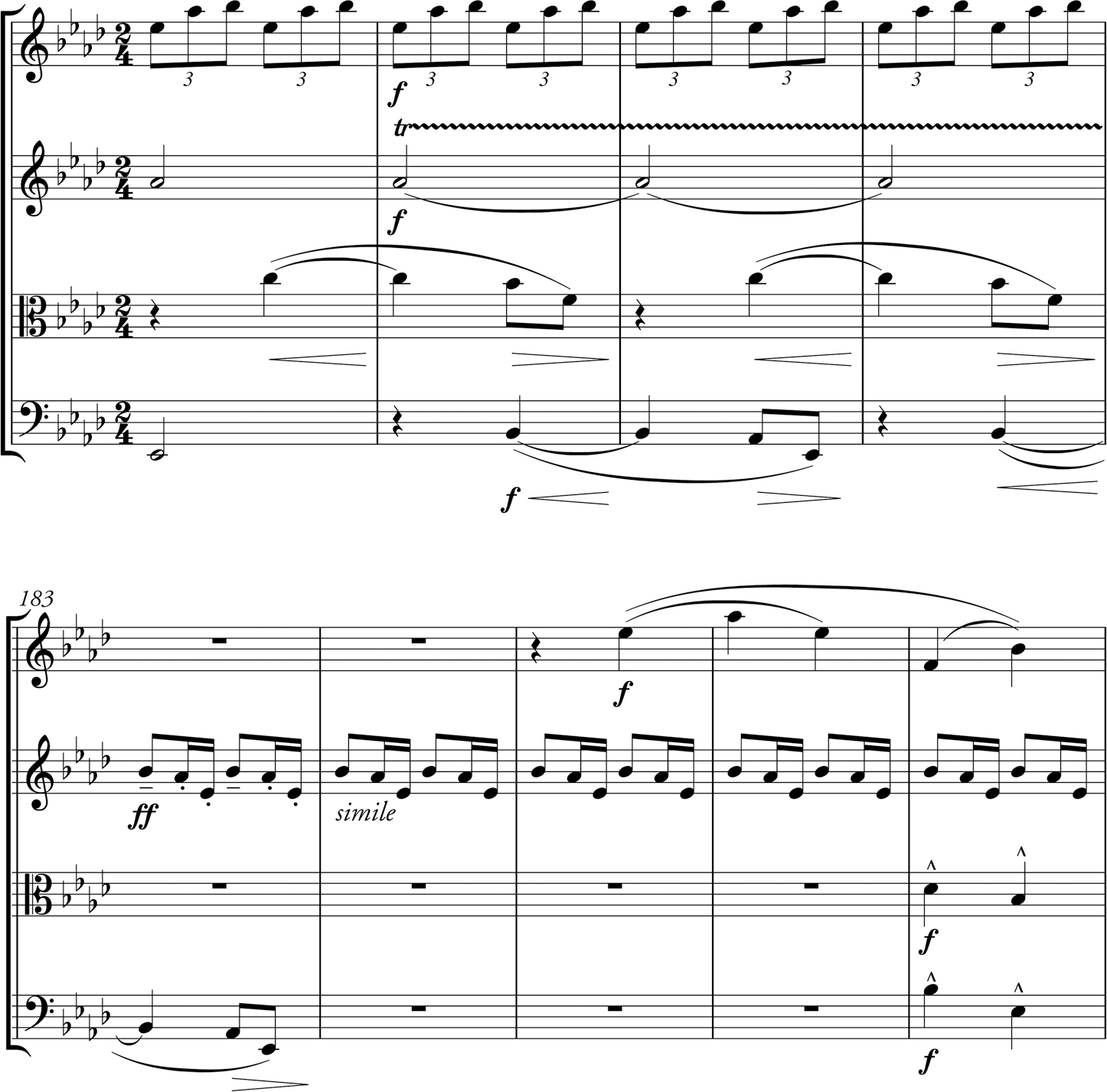

Example 1. Rhythmic strata in Janáček's music. Leoš Janáček, String Quartet no. 1 (‘Inspired by Tolstoy's Kreutzer Sonata’), 1923 (Prague: Supraphon; 2nd edn, rev. Milan Škampa, 1982), second movement, bars 179–87. All subsequent extracts from this work refer to this edition.

Horizontal montage has far-reaching consequences for the formal structure of Janáček's music. The Czech composer and musicologist Josef Berg compared the formal designs of Janáček's late works to a mosaic; he suggested that they are based not on the linear and continuous development of motifs and themes, but rather on a succession of distinct variants of one or several recurring motivic fragments cast in various rhythmic, metric, modal and textural contexts.Footnote 48 Such context is provided primarily by the underlying ostinatos (sčasovky), which often persist throughout whole formal sections. In other words, a particular ostinato pattern invests each section with a distinctive identity and its change often amounts to a significant form-constitutive event.

A number of parallels with the Janáčekian compositional-technical features described above will be observed in the following analysis of the first movement of Haas's quartet, in which I explain how an abstract dynamic trajectory is ‘distilled’ from pictorial rhythmic elements. One of the contemporary critics observed that the first movement ‘depicts the composer's rambling through a hilly landscape’, portraying with ‘apt humour’ the ‘pleasure drawn from movement and events along the journey’.Footnote 49 Haas's mention of the ‘rhythm of a broad landscape’ in his commentary on the quartet arguably refers to the ostinato rhythm at the beginning of the first movement. The opening section bears resemblance to the melodic and rhythmic patterns of the blues: notice the ‘off-beat’ rhythmic pattern in what would be the piano left-hand part (see Example 2) and the chromatic inflections of the solo violin melody hovering above this accompaniment (see Example 3). Once F is established as the ‘tonic’, the chromatic variability of the third and seventh degrees (the ‘blue notes’, in this case A/A♭ and E/E♭ respectively) becomes apparent.

Example 2. Opening ostinato, Pavel Haas, String Quartet no. 2 (‘From the Monkey Mountains’), op. 7, 1925 (Prague: Tempo; Berlin: Bote & Bock, 1994), first movement, bars 1–2, violin 2 and viola. All subsequent extracts from this work refer to this edition.

Example 3. Blues-scale inflections in the opening theme, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, first movement, bars 3–10, violin 1.

Quite remarkable is the way in which the initial ‘blues’ ostinato comes to a stop by means of the gradual augmentation of rhythmic values, only to be replaced by another, more agitated one (see Example 4). In fact, this is a distinctly Janáčekian technique, based on movement across rhythmic layers. As is often the case in Janáček's formal designs, the onset of a new ostinato pattern marks the beginning of a new formal section (marked ‘b’ in the schema shown in Figure 2). The characteristically Janáčekian texture consisting of ostinatos, trills and melodic/rhythmic fragments scattered across the score is even more apparent in Example 5. Moreover, the march-like ‘oom-pah’ accompaniment figure reinforces the music's association with bodily movement. Throughout the whole movement, this passage is most likely to evoke the image of a tourist marching through a hilly landscape. One could even see in the extremely high register of the violin part and in the trill, typically associated with excitement in Janáček's music, signs of the ‘pleasure drawn from movement’ mentioned in the review quoted above.Footnote 50

Example 4. Change of the underlying ostinato, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, first movement, bars 38–40.

Example 5. Janáčekian texture, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, first movement, bar 44.

Figure 2. Rhythm and form in ‘Landscape’.

With a rapid change of texture, the motif that was previously presented in crotchets reappears in semiquavers, transformed into a characteristically short and sharply articulated Janáčekian melodic fragment. Haas's mention of the ‘rhythm of birdsong’ in his commentary undoubtedly refers to the section illustrated in Example 6. The return of the opening ostinato in rhythmic diminution marks the beginning of what might appear to be a recapitulation (see Example 7). In fact, this is another step up the ladder of rhythmic layers, a part of the continuous escalation of momentum which spans the entire first section of the movement. The increasing rhythmic activity is accompanied by textural complication, the employment of extremely high registers and the accumulation of motivic material (the ‘birdsong motif’ gradually becomes submerged in the ostinato).

Example 6. ‘Birdsong’ motif, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, first movement, bars 48–52.

Example 7. Opening ostinato in diminution and ‘birdsong’ motif, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, first movement, bars 66–8.

When the intensification reaches its climax, another rapid cut in tempo, rhythm and texture announces the beginning of a contrasting middle section. This is characterized by homophonic texture, slow tempo (Lento ma non troppo) and a regular, albeit ambivalent metrical pattern: whereas the melody is cast in 3/4 metre, the chordal accompaniment is notated in 6/8 (see Example 8). The regular slow pulse of this section invites another bodily metaphor, as it corresponds with the rate of the human heart during rest (note the composer's mention of ‘the warm song of a human heart’ in the commentary quoted above). The middle section, which is permeated by this regular beat, thus physiologically associates the moment of repose following the escalation of activity in the first part of the movement. At its end, however, the slow pulse is progressively disturbed by outbursts of the first section's ostinato, the assertion of which marks the beginning of the ‘recapitulation’ (see Example 9). This agitated rhythmic pulse persists until the end of the movement, providing a unifying ‘background’ for the recapitulation of the movement's motivic material, including the theme of the slow section. Figure 2 (see p. 76) represents the occurrence of the most extensively used of the ostinato patterns observed above. There are four main rhythmic patterns, which have been arranged in descending order of rhythmic values. The scheme indicates that the changes of the underlying rhythmic pattern delineate the movement's formal sections. Throughout the first section (A), rhythmic values are gradually diminished. Simultaneously, layers of ostinatos are gradually superimposed to increase rhythmic activity and textural density. The momentum suddenly drops in the middle section (B) and is resumed in the final section (A'). Significantly, the resulting dynamic trajectory, which follows the pattern ‘escalation–repose–finale’, is also replicated on a large scale in the succession of the four movements of the piece, which thus, as the composer himself suggested, ‘culminates rhythmically and dynamically in its last movement’.

Example 8. Contrasting middle section, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, first movement, bars 90–7.

Example 9. Intrusion of the ostinato, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, first movement, bars 136–8.

A parallel emerges with the endeavours of Honegger in his symphonic movements Pacific 231 and Rugby, in which formal design is underpinned by metro-rhythmic procedures.Footnote 51 From the perspective of Teige's writings, these works would have been very attractive owing to their connotations of rational ‘construction’, sports, bodily movement and so on. Honegger's Pacific 231 has more immediate relevance to Haas's ‘Landscape’, not least in that it was performed in Brno in 1924.Footnote 52 Arguably, there is a conceptual parallel in the preoccupation with rhythm and momentum. In both cases a particular dynamic trajectory is created by gradual diminution of rhythmic values and increasing density of contrapuntal texture.

A more detailed discussion of the form-constitutive functions of rhythm in this movement cannot be undertaken here, as it is not the primary concern of this study.Footnote 53 However, I wish to conclude the discussion of ‘Landscape’ by arguing as follows: first, Haas, influenced by particular aspects of the aesthetic of Poetism (as epitomized in Teige's notion of ‘poetry for corporeal and spatial senses’), used Janáčekian compositional-technical devices in order to create a formal design determined primarily by rhythm – the musical parameter that is most intimately correlated with physical movement, speed, dynamism and so on. Secondly, Janáček was a crucial source for Haas's use of rhythm as a medium of communicating various emotional and sensual impressions by means of physiological empathy. It is remarkable that Janáček's thoughts on the expressive potential of rhythm, although they were informed by nineteenth-century sensitivity, could still be appropriated by Haas within a strikingly different aesthetic framework informed by Poetism.

‘Carriage, Horseman and Horse’: a grotesque ride

The second movement of the quartet relies on tone-painting much more than the first. As far as its ‘programme’ is concerned, the title ‘Carriage, Horseman and Horse’ and Haas's reference to the ‘irregular movement of a rural vehicle’ in his commentary are the only clues given to the listener. Nonetheless, when guided by the music, one needs no further description to imagine the creaking cart uneasily moving off, gradually picking up momentum, bouncing along an uneven track, getting out of control and finally breaking down. Contemporary critics were put off by the frivolous humour of this movement, which many of them described as ‘grotesque’.

Since the notion of the grotesque is central to the following line of argument, I will proceed by summarizing briefly the main features of the grotesque and its manifestation in music, drawing on studies by Esti Sheinberg and Julie Brown.Footnote 54 The grotesque has been described as a hybrid form, a bizarre and irrational cluster of incongruities in which all kinds of boundaries are blurred – typically those between laughter and horror; merriment and frenzy; sanity and insanity; life and death; animate and inanimate; man, machine, animal and vegetable.Footnote 55 The sense of hybridism, ambivalence and confusion can be conveyed through the juxtaposition of musical elements that are incongruous in terms of style, character or musical syntax.

It has also been argued that grotesque art communicates through the medium of the human body and that sensual perception and physical empathy take precedence over rational, conceptual thought.Footnote 56 The effect of the grotesque is created primarily by violations of an implicit bodily norm, namely through exaggeration and distortion. Sheinberg suggested that hyperbolic distortion of the bodily norm can be musically articulated by using a tempo which is too fast for human motion, a register too high for the human voice, or ‘unnatural’ rhythmic patterns, contrasting with the natural rhythms of the human body (walk, heartbeat and so on).Footnote 57 Musical instances of the grotesque often make use of dance gestures because of their association with bodily movement. Sheinberg suggested the following list of musical features which ‘enhance a feeling of compulsive obsession that relates to the insane, bizarre side of the grotesque and to its unreal, unnatural aspects’: a ‘tendency to triple metre, which enhances the feeling of whirling, uncontrollable motion, sudden unexpected outbursts, loud dynamics, extreme pitches, marked rhythmical stresses, dissonances or distortions of expected harmonic progressions, and many repetitions of simple and short patterns’.Footnote 58

The first example of grotesque exaggeration and distortion in Haas's quartet appears at the very beginning of the second movement (see Example 10). The coarse opening glissandos paraphrase the opening motif of the first movement. The initial notes (E, D, E♭, D♭, C) of what was originally a fluid melody played in the upper register of the violin are now mechanically repeated, encumbered with heavy accents, played in parallel seconds in the lower register of viola and cello, and, most provocatively, disfigured by ‘creaking’ glissandos. As the title suggests, this musical effect may illustrate the squeaking wheels and the horse's neighing. In any case, the movement opens with a grotesque musical image of a body (possibly a hybrid body conflating the animal with the vehicle) distorted and pushed to the extreme. Another level of distortion is added when an incongruent metrical pattern (3/8 + 3/8 + 2/8) is introduced in the accompaniment, creating the sense of irregular or awkward motion. At the same time, the pitches of the initial motif are adapted to yield a pentatonic collection, which, through its traditional association with exoticism, makes the section sound ‘strange’ (see Example 11).

Example 10. The opening glissandos, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, second movement, bars 1–4.

Example 11. Metric conflict and pentatonicism, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, second movement, bars 17–18.

In contrast with the rather static character of the opening, the second section (più mosso) is emphatically motoric. A new, highly repetitive theme suggestive of a horse's trot is introduced in the second violin (quavers), accompanied by semiquavers phrased in groups of three. The resulting cross-rhythms convey the impression of ‘irregular’ and ‘bouncy’ movement. The realm of pitch betrays another incongruity: like the opening theme of the first movement, the ‘horse-trot’ theme consists essentially of a descending blues scale, which is characterized by an inherent ambivalence between major and minor mode. As a result, the musical depiction of the ride oscillates, in Sheinberg's terms, between ‘euphoric’ and ‘dysphoric’ values, traditionally associated with ‘major’ and ‘minor’ modality respectively (see Example 12).Footnote 59 The theme, originally presented in ‘comfortable’ tempo (quavers) and register, is subsequently repeated in double speed (semiquavers) and transposed to an extremely high register, with the ‘bouncing’ effect enhanced by dotted rhythm. Significantly, the composer annotated this section ‘tečkovaný cirkus’ (‘dotted circus’) on the margin of his autograph (see Example 13).Footnote 60 Indeed, this section is marked by a musical idiom which is strikingly similar to that of the music accompanying actual circus performances. Particularly characteristic is the use of stock accompaniment patterns associated with the march or a quick dance in duple metre such as the polka. In keeping with these contextual associations, the passage is marked by the typically clownish mixture of humorousness and silliness. First, the newly added components (dotted rhythm, dance/march topic) further exaggerate the already prominent emphasis on physical movement, which is thus made excessively explicit and satirized.Footnote 61 Secondly, highlighting the ‘inessential’ musical components introduces an element of the banal.Footnote 62 The bars that follow Example 13 are literally filled up by the repetitive accompaniment pattern in order to expand the four-bar ‘dotted circus’ theme into a neat (and in itself pronouncedly banal) eight-bar phrase.

Example 12. ‘Horse-trot’ theme in quavers, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, second movement, bars 24–32.

Example 13. ‘Dotted circus’ theme, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, second movement, bars 42–7.

The exaggeration of the obvious and inessential is a satirical device that invests the sense of merriment with a mocking undertone. However, the same strategy may also serve the purpose of the grotesque, which prevails once such hyperbolic distortion evokes a sense of obsession, insanity and frenzy that overrides the initial sense of humorousness, gaiety and merriment.Footnote 63

This is surely the case in the violent motoric climax that immediately follows the ‘circus’ section, where the ‘horse-trot’ theme is stated in double diminution (demisemiquavers), played by all four instruments in unison. This ‘liquidation’ of the theme leads to a collapse and all movement comes to a stop within a few bars of Tempo I, before the whole process of gradual accumulation of momentum starts again from the opening glissandos, with minor variations to texture and figuration (see Example 14). This is likely to be the very passage that reminded the critics of Honegger's Pacific 231. Indeed, it is arguable that Haas picked up and trivialized the idea of acceleration and deceleration of the supposed locomotive (reduced here to a ‘rural vehicle’) and thus added a parodic dimension to his piece.

Example 14. ‘Liquidation’ of the theme and motoric collapse, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, second movement, bars 51–8.

What the two pieces also have in common is the technique of gradual diminution of rhythmic values, the application of which is also self-consciously trivial (certainly in comparison with Pacific 231). In this case, this becomes the principal means of grotesque distortion: the musical material associated with bodily movement is rendered ‘too fast’ and often simultaneously transposed to registers that are ‘too high’. This process also implicitly suggests the mechanization of the animate: what was initially a comfortable horse's trot has been accelerated into motor-like motion. The theme's gradual rhythmic diminution is reminiscent of the shifting gears of a motor vehicle. This yields a typically grotesque image of a hybrid body conflating an animal with a machine.

Cinematic aspects of the second movement

There are several reasons to draw a parallel between the second movement of Haas's quartet and the medium of film. First, the illustrative character of the music invites visual representation. The movement's title – ‘Carriage, Horseman and Horse’ – immediately suggests a picture, which the music sets in motion or, one might say, ‘animates’. One might even wonder whether Haas was aware of René Clair's 1924 film Entr'acte with music by Satie, in which the image of a funeral vehicle drawn by a camel gains much prominence. Starting in slow motion, the funeral procession gradually turns into a chase after the runaway hearse, racing wildly through the streets of Paris to the accompaniment of Satie's music. This film's absurd humour and satirical undertone is highly characteristic of the subversive spirit of Dada, which was closely related to the sentiments preached by Poetism.

Secondly, the term ‘grotesque’, which was repeatedly used in reviews of the piece, has also been used as a noun in Czech to refer to cartoons and short film comedies known as ‘slapsticks’ in English.Footnote 64 It is thus highly probable that when the Czech critics referred to Haas's music as ‘grotesque’, their understanding of the term was at least partly informed by its connotation with slapstick comedies of the day. Finally, American slapsticks (especially those made by Charlie Chaplin), which gained immense popularity throughout Europe in the 1920s, were celebrated by Poetism as the ultimate form of popular entertainment, outmatching circuses, cabarets and variety shows.Footnote 65

There are several ‘technological’ parallels between the second movement of the quartet and early films and cartoons. Haas inherited from Janáček elements of his ‘montage’ technique, which is essentially cinematic in its juxtaposition of stretches of music divided by ‘cuts’ rather than transitions. The mechanistic metaphor of shifting gears, used above to describe Haas's technique of progressive rhythmic diminution, is also applicable to the speed with which a reel of film unrolls. The technological limitations of early film projectors often rendered movement unnaturally fast and therefore jerky and mechanistic, which enhanced the comical effect of slapsticks. Besides, in the above-mentioned film by Clair, slow, fast-forward and reverse motion was purposefully used (besides other visual effects) to convey the sense of the ever faster and ‘wilder’ ride of the runaway hearse. The repetitive nature of much of Haas's music is suggestive of the ‘loop’ technique widely used in early 1920s cartoons. The movement's trivial narrative is repeated several times with minor variations before the cart joyfully drives off (a moment inviting the obligatory fadeout). The whole movement is roughly five minutes in duration, which just about matches the length of contemporaneous ‘shorties’.

There are also similarities between the types of distortion described above and the repertoire of visual gags used in 1920s cartoons, such as those made by Walt Disney, in which grotesque imagery is virtually omnipresent. Much of the comical effect of Disney's cartoons was based on the images of distorted, dismembered and hybrid bodies mingling animate and inanimate elements. Unlike the bodies of live actors in film comedies, those of cartoon characters have no limits. They can take on hybrid forms, they can move in awkward ways that defy the laws of physics, they can be distorted or even dismembered and still, unlike static pictures to which earlier manifestations of the grotesque were confined, keep moving.Footnote 66 I am not suggesting that Haas was directly influenced by a particular Disney cartoon, but I do argue that his musical illustration relies for its effects, as Disney cartoons do, on the distorted image of the body in motion. It is also worth mentioning that forms of popular entertainment such as sports events, circuses and fairs are commonplace in Disney cartoons, and also influenced the choice of soundtracks. Thus, many of his cartoons were accompanied by circus-like music similar to that invoked by Haas in the ‘dotted circus’ section.Footnote 67

The most profound affinity, however, resides in the emphasis on humour. Poetism celebrated slapstick as the art of laughter, which is universal, non-elitist and unhindered by conceptual intricacies and language barriers. I argue that ‘Carriage, Horseman and Horse’ was conceived as a musical analogue of slapsticks, a humorous mischief to be enjoyed and laughed at, one which is self-consciously simple in order to be as comprehensible as the visual gags of slapsticks. As such, it could even be regarded as a satirical commentary on the metaphysical baggage of Romantic ‘programmatic’ compositions, as an avant-garde statement of rejection of the preceding artistic tradition.

The grotesque, carnival and Poetism: a Bakhtinian perspective

So far, the grotesque has been treated merely as an artistic device. However, the meaning conveyed by the device depends on its particular aesthetic and cultural context. For example, Brown's interpretation of the grotesque in Bartók's music is underpinned by the framework of Expressionism. I argue that Haas's use of the device, informed by the programme of Poetism, necessarily produces different meanings.

For the purpose of her study, Brown regards ‘the grotesque body with its emphasis on distortion and abnormality, and conflations of the comic and the terrifying’ as ‘a perfect figurative manifestation’ of ‘early twentieth-century crises of subjectivity’.Footnote 68 Interestingly, the modern urban industrial world, which had been regarded as the source of alienation, fear and anxiety by the Expressionists, was considered enchanting rather than threatening from the perspective of Poetism. As a world-view, Teige argued, Poetism was ‘nothing but […] excitement before the spectacle of the modern world. Nothing but loving inclination to life and all its manifestations, the passion of modernity […]. Nothing but joy, enchantment and an amplified optimistic trust in the beauty of life.’Footnote 69

Bakhtin offered an alternative notion of the grotesque that is much more compatible with the agenda of Poetism. He shows that the ‘dark’ side of the grotesque, while always lurking in the background, need not always dominate, and that the irrationality and hybridism need not always be threatening. As David K. Danow has explained, Bakhtin differentiated between two concepts of the grotesque according to the presence or absence of the moment of renewal or rebirth: whereas the ‘medieval and Renaissance’ grotesque was endowed with regenerative power stemming from the principle of laughter, the ‘Romantic’ grotesque lost the power of regeneration and became the expression of insecurity and fear of the world.Footnote 70 The latter type of the grotesque is static (the state of aberration, defect and death is final and therefore threatening), whereas the former is essentially dynamic: ‘The grotesque image reflects a phenomenon in transformation, an as yet unfinished metamorphosis, of death and birth, growing and becoming.’Footnote 71 Bakhtin's emphasis on rebirth rather than death is matched by a focus on (immortal) mankind rather than on (mortal) man; as Danow points out, the transcendent laughter belongs to collectives, not to individuals.Footnote 72 This observation also illuminates the difference involved in understanding the grotesque in the subjectivist ‘Romantic’ era (which gave rise to Expressionism).

Influenced by Bakhtin's ideas, Sheinberg construes the grotesque as the ‘positive’ counterpart of what she calls the ‘negative existential irony’: ‘Both have two layers of contradictory meaning, neither of which is to be preferred: both regard doubt and disorientation as the basic condition of human existence. Finally, the main purport of the grotesque, as well as that of existential irony, is its unresolvability.’Footnote 73 The difference, which resides in the mode of coexistence of the unresolvable ambiguities, is encapsulated in the terms ‘infinite negation’ and ‘infinite affirmation’:

The intrinsic irony of the human condition can take two opposing directions: on the one hand, it can continue with its contradictory meanings in a process of infinite negation, resulting in Kierkegaard's concept of irony, which eventually is a nihilistic despair. On the other hand, it can start a similarly infinite line of affirmations, that will eventually accumulate to form the Bakhtinian concept of the grotesque, in which all possible meanings of a phenomenon are clustered and accepted as an experienced reality.Footnote 74

The grotesque, in a Bakhtinian sense, is based on the principle of acceptance of all ambiguities, the outcome of which is an accumulation and an ‘excess of meanings’.Footnote 75 Thus, as Sheinberg explains, Bakhtin did not conceive the grotesque as destructive and nihilistic, but rather ‘as a victorious assertion of all life's infinite “buds and sprouts”’.Footnote 76 It remains to point out that Bakhtin's views on the grotesque are intrinsically linked with his notion of carnival, as his use of the term ‘carnivalesque-grotesque’ clearly indicates.Footnote 77

Renate Lachmann explains the social significance of carnival in terms of the juxtaposition of ‘culture and counter-culture’ – in the case of Bakhtin's study of Rabelais, the juxtaposition of the strictly hierarchical model of medieval society with the ‘folk culture of laughter’.Footnote 78 Typically, carnival stages the world turned ‘upside down’, relativizing and ridiculing the norms and values of the dominant culture. Importantly, the effect of this travesty is not destructive, but regenerative:

The temporary immersion of official culture in folk culture leads to a process of regeneration that sets in motion and dynamically energizes the notions of value and hierarchy inverted by the parodistic counter-norms of the carnival. In this way the culture of laughter revives and regenerates the petrified remains of official institutions and, as it were, hands them back to official culture.Footnote 79

Carnival thus facilitates a mythological death and rebirth through the principle of laughter, its recourse being to all that is material, corporeal, sensual or sexual and to the ‘unofficial, uncanonized relations among human beings’.Footnote 80 Bakhtin, in his study of folk culture in the work of Rabelais, construed carnival as a force which makes it possible ‘to consecrate inventive freedom, […] to liberate from the prevailing point of view of the world’ and which ‘offers the chance to have a new outlook of the world, to realize the relative nature of all that exists, and to enter a completely new order of things’.Footnote 81

The dialectical pair of culture and counter-culture matches Teige's conceptual duality between ‘Poetism’, representing imagination, creativity and playfulness, and ‘Constructivism’, representing logic, rationality and discipline.Footnote 82 If Lachmann's concept of culture and counter-culture is transposed to the sociocultural reality of the 1920s, the industrialized modern society based on inexorable logic, rationality and functionality represents the dominant culture which ‘has succumbed to cosmic terror’, since its structure and approach to work and production is goal-orientated, ‘finalistic’ and ‘directed toward the “end”’.Footnote 83 Poetism, on the other hand, can be construed as the counter-culture of laughter, capable of revitalizing the former.

Teige's characterization of Poetism takes on a distinctly Bakhtinian tone as he describes it as ‘the culture of miraculous astonishment’: ‘Poetism wants to turn life into a spectacular entertaining affair, an eccentric carnival, a harlequinade of sensations and fantasies, a delirious film sequence, a miraculous kaleidoscope.’Footnote 84 Teige further claims that Poetism ‘was born in the climate of cheerful conviviality, in a world which laughs; what does it matter if there are tears in its eyes?’Footnote 85 This quotation implies that Poetism as a life perspective is not turning a blind eye to the difficulties of life. Nonetheless, to put it in a Bakhtinian manner, the irreconcilable contradictions of modern existence are to be accepted through the principle of laughter.

The art of Poetism invited its recipients to participate in a carnivalesque feast, to overcome the ‘cosmic terror’, the frustration and alienation elicited in human subjects by the ‘finalistic’ modern society, to embrace Poetism as a modus vivendi and to be reborn in the state of poiesis.Footnote 86

Haas and the ‘eccentric carnival of artists’ in Brno

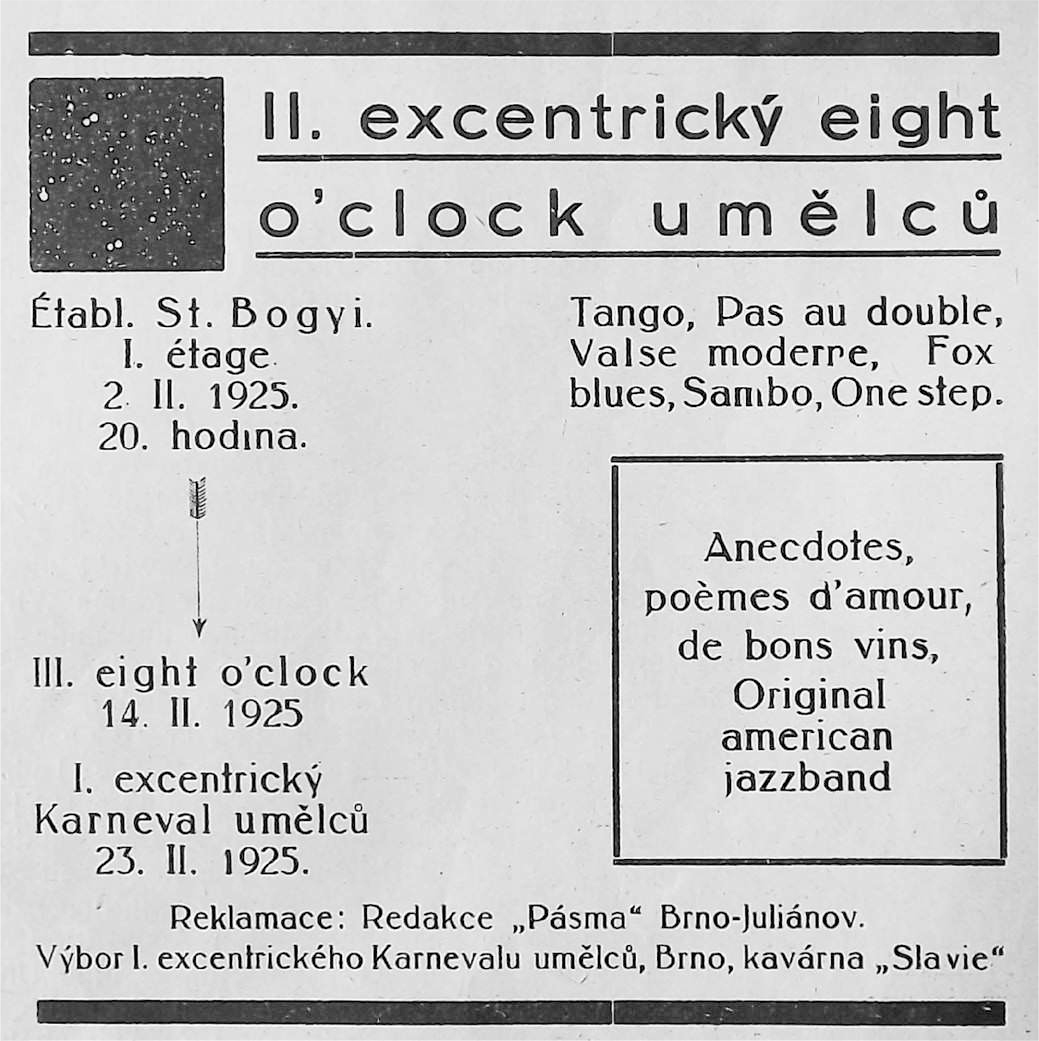

As noted above, the activities of Devětsil in Brno included the organization of social events. Figure 3 shows the advertisement for one of the ‘Eccentric Eight o'Clocks of Artists’ organized as a run-up to the ‘Eccentric Carnival of Artists’. Both of these events took place in 1925, just months before Haas started the composition of his quartet.

Figure 3. Advertisement for the ‘2nd Eccentric Eight o'Clock of Artists’. Pásmo, 1/7–8 (1924–5), 9.

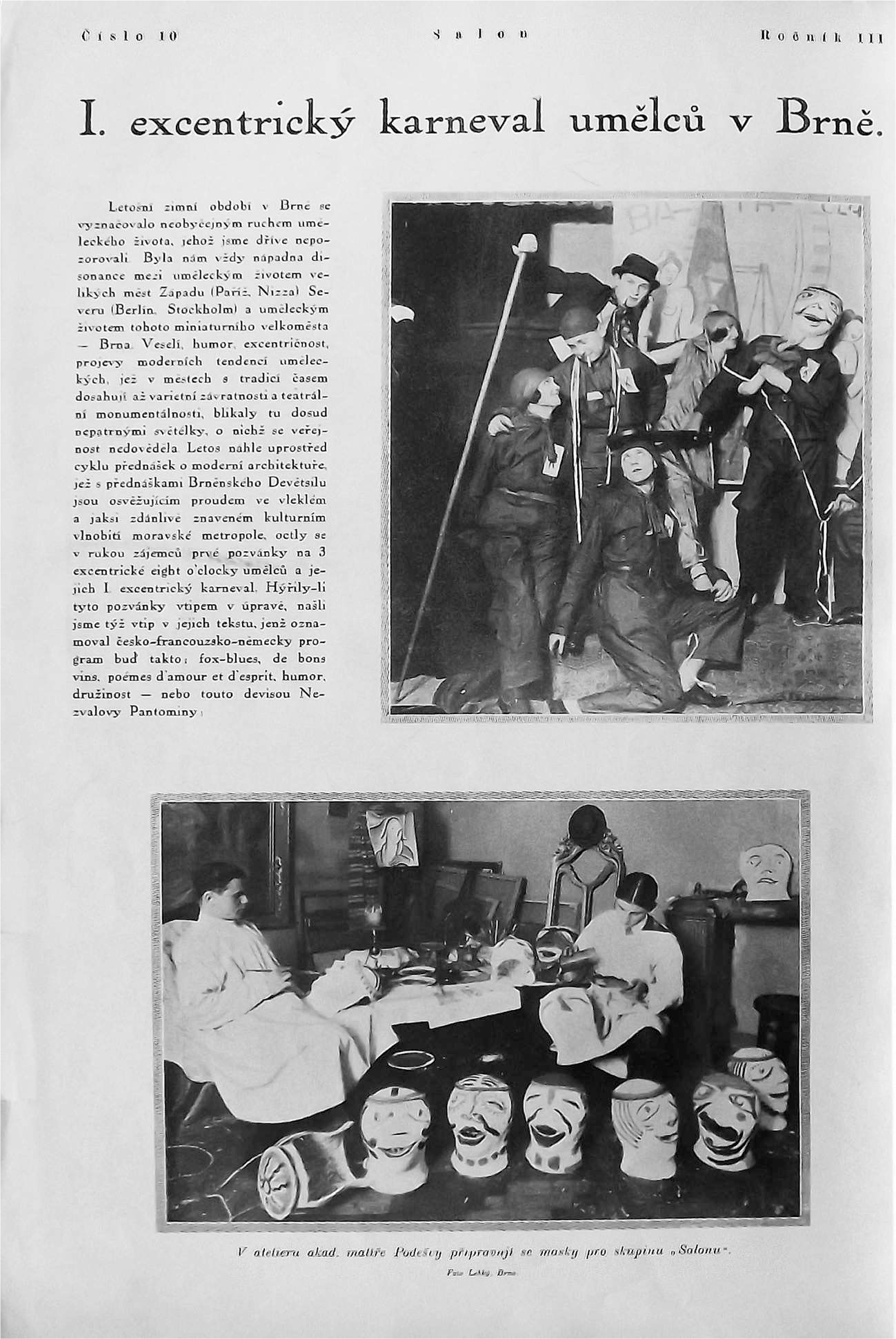

It is noteworthy that the advertisement promises an ‘original American jazz band’. In fact, this is not the only time a jazz band is mentioned in connection with the ‘eccentric’ events of Devětsil. An article reflecting upon the Eccentric Carnival of Artists, published in the journal Salon (the article's first page is shown in Figure 4), reports that invitations to the event included the following lines from Nezval's poem Podivuhodný kouzelník (Miraculous Magician):

Figure 4. First page of ‘1st Eccentric Carnival of Artists in Brno’. Salon, 3/10 (1925), no page numbers. The upper photograph shows members of Devětsil, supposedly dressed up as robots; the lower photo shows the manufacturing of masks. According to the recollection of the Devětsil member Bedřich Václavek (quoted in Macharáčková, ‘Z dějin Brněnského Devětsilu’, 87), the event involved ‘shooting in the manner of the people of the Wild West’, ‘dancing modern dances’ and ‘reciting of Dadaist poems’ (‘stříleli jsme jako lidé z divokého západu […] recitovali dadaistické básně, tančili moderní tance’).

| A básníci už neprosí | (And poets no longer beg |

| za chudou prebendu, | for a modest stipend, |

| ti baví se jak černoši | they have a good time like black men do |

| při řvoucím JAZZ-BANDU.Footnote 87 | with a roaring JAZZ BAND.) |

It is doubtful that either of these events would host an ‘original American jazz band’. An intriguing terminological issue was revealed by the Czech popular-music scholar Josef Kotek, who observed that in the early 1920s ‘jazz’

was not used as a general term denoting the new dance music, but at first just as a name for the massive, hitherto unseen percussion set. […] One can easily imagine the sensation which this rackety instrument [the percussion set] elicited in the limited sonic spectrum of the day. […] In the first years [of the 1920s] the typological and stylistic characterization of new music seems to have been limited to the percussion set.Footnote 88

Indeed, Haas himself referred to the percussion set as ‘jazz’ in his commentary. His decision to use ‘jazz’ in his string quartet gains special significance, considering the emphasis laid on this iconic feature of modern popular music in the advertisements for Devětsil's ‘eccentric’ events.

The Eccentric Carnival of Artists was introduced by a speech, delivered by the Brno-based poet Dalibor Chalupa (1900–83),Footnote 89 who later published a poem entitled Karneval, undoubtedly inspired by the event.Footnote 90 Significantly, this poem was set to music by Haas as the male chorus Karneval, op. 9 (1928–9):Footnote 91

| Karneval | Carnival |

|---|---|

| (Sbor huláká, jazzband lomozí.) | (The choir bellows, the jazz band makes a racket.) |

| Masky | Masks |

| vypouklá zrcadla | Bulging mirrors |

| světelné signály na moři | Light signals on the sea |

| smutní umírají | Sad people die |

| lilie povadla | The lily has wilted |

| maskovaní lupiči v ulicích táboří | Masked bandits camp in the streets |

| lampiony zrají. | Chinese lanterns ripen. |

| (Sbor huláká, jazzband lomozí.) | (The choir bellows, the jazz band makes a racket.) |

| Čtyři levé nohy | Four left legs |

| spirála červenozelená | A red-green spiral |

| a klauni ztratili klíče | And clowns lost their keys |

| v ulici beze jména | In a nameless street |

| S bohem, Beatrice. | Goodbye, Beatrice. |

| (Bubny, činely, výstřel.) | (Drums, cymbals, gunshot.) |

| Harfou proskočil Indián | An Indian jumped through the harp |

| Zvony zvou vyzvánějí zvonivě | Bells bellow blasting blows |

| modrých zvuků lán | A field of bluebells |

| a vítr zvedl vlasy Godivě | And the wind blew up the hair of Godiva |

| činely letí k zenitu | Cymbals fly up to the zenith |

| ztratil se prsten | A ring got lost |

| není tu – není tu. | It's not here – it's not here. |

| (Housle.) | (Violin.) |

| Polibky s pomoranči | Kisses with oranges |

| dekolté | Décolleté |

| malé Javanky tančí | Little Javanese girls dance |

| v náruči Kristinu najdete | Kristina is to be found in [someone's] arms |

| Ó ohně ó planety | Oh fires oh planets |

| den začíná | The day begins |

| Růžová ňadra | Pink breasts |

| brokáty | Brocades |

| žije Mona Lisa | Mona Lisa lives |

| žije Kristina. | Kristina lives. |

| (Passo double.) | (Paso doble.) |

| Motýli | Butterflies |

| bělostné kotníky | White ankles |

| Opiovým snem pluje gondola | A gondola sails through an opium dream |

| Země odletěla | The Earth has flown away |

| a vesmírem tančí | And dances through space |

| dans excentric | Danse excentrique |

| na jazzband hraje kolibřík. | A hummingbird plays the jazz band. |

| [po prstech šlape kostlivý tanečník.] | [A skeletal dancer treads on tiptoes.] |

| […] | […] |

| (Sbor huláká, jazzband lomozí.) | (The choir bellows, the jazz band makes a racket.) |

| Duhové blesky tančí | Rainbow-coloured thunderbolts dance |

| kolotoč na parníku | A carousel on a steamboat |

| Hle, radostí pláčí | Look, crying with joy are |

| vrcholky obelisků | The tops of obelisks |

| Zeppelin letí k pestré obloze | Zeppelin flies to the multi-coloured sky |

| prérie v plamenech | A prairie on fire |

| Překrásná explose | A beautiful explosion |

| Jeden vzdech. | One sigh. |

| (Výstřel.) | (Gunshot.)Footnote 92 |

Chalupa's poem contains a number of the topoi of Poetism. First of all, there is carnival itself, complete with imagery of ‘gondolas’, ‘Chinese lanterns’, ‘masks’ and ‘clowns’. Typical also is the mild eroticism that manifests itself in fleeting references to various female figures (‘Beatrice’, ‘Godiva’, ‘Kristina’, ‘Mona Lisa’), all of which seem to coalesce into a single archetype of feminine beauty. Besides the obligatory element of exoticism (‘an Indian’, ‘little Javanese girls’), there are also references to iconic features of modern civilization (‘jazz band’, ‘steamboat’, ‘Zeppelin’).

Perhaps more important than this catalogue of topoi is the dream-like juxtaposition of individual elements. The imaginative use of wordplay and the free association of images are reminiscent of Apollinaire's poetry, which was highly influential among the Poetists. Thus, the ‘fires’ of Chinese lanterns associate with ‘planets’ and the ‘pink breasts’ of Mona Lisa / Kristina; the ‘multi-coloured sky’, illuminated by the ‘rainbow-coloured thunderbolts’ (perhaps of fireworks), is likened to a ‘prairie on fire’ and a ‘beautiful explosion’ of the Zeppelin; the ringing of bells conjures up the sight of a field of bluebells; a harp becomes a circus hoop through which an ‘Indian’ jumps; cymbals are suddenly animated and ‘fly up to the zenith’; the hummingbird becomes a jazz-band player, etc. This nonsensical, fantastic sequence of images, resembling a Dadaist or Surrealist film scenario, conveys the sense of bewilderment associated with carnival.

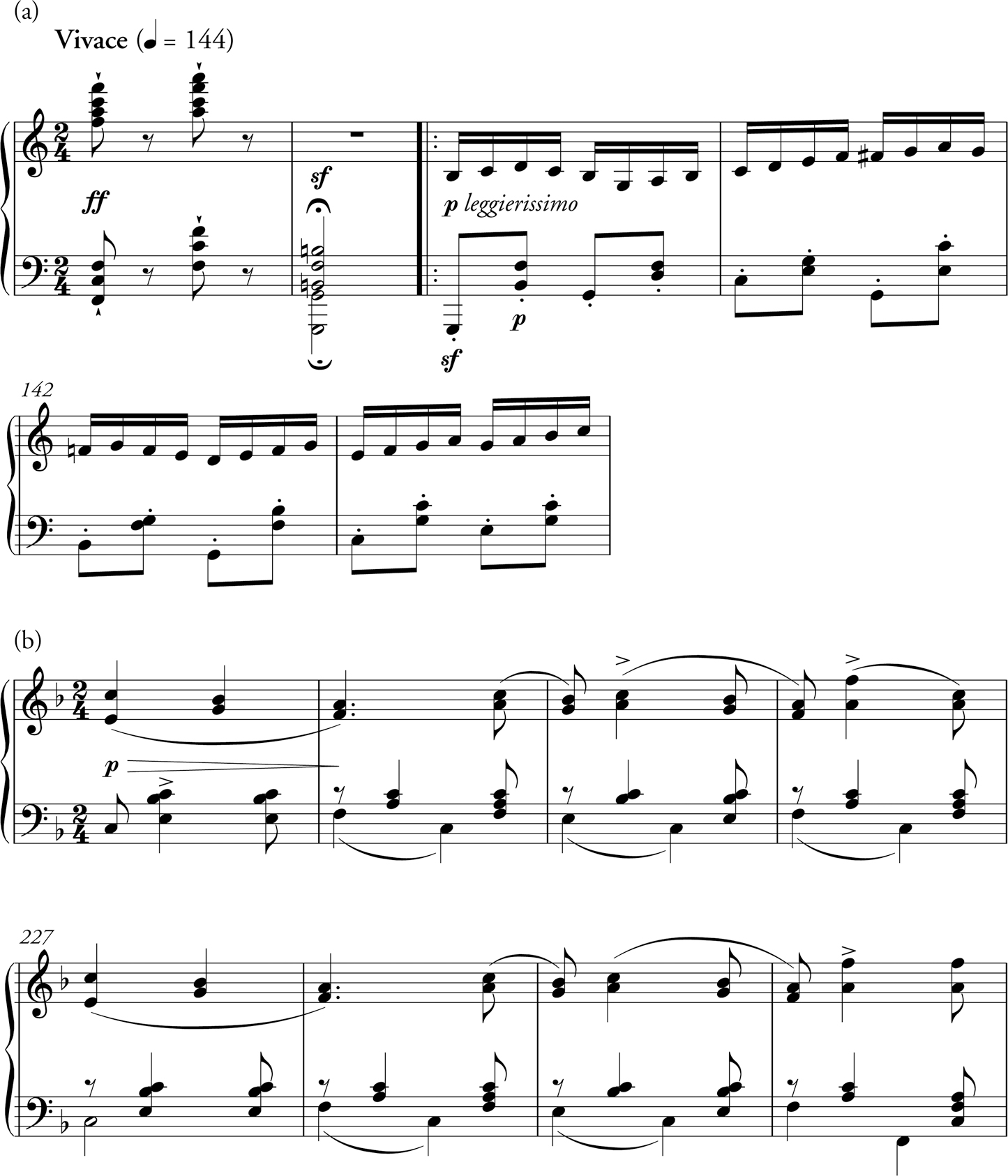

True to the dictum of ‘poetry for the senses’, Chalupa's poem attempts to convey not only visual but also aural sensations – particularly through bracketed illustrative remarks placed between the strophes, such as ‘the choir bellows, the jazz band makes a racket’ and ‘drums, cymbals, gunshot’. In his musical setting, Haas drew on these indications. However, unlike in the string quartet, where he employed an actual ‘jazz-band’ percussion set, in Karneval the composer relied purely on the means offered by the chosen medium – the male-voice choir. Thus he used onomatopoeic words (‘bum – džin’; ‘boom – jin’) in conjunction with repetitive march-like accompaniment patterns to imitate the sound of drums and cymbals; similarly, the lyrics ‘ra-tada-da-ta’ mimic a snare drum. Since the piece is mostly in 2/4, marked ‘tempo di marcia’, these effects are suggestive of a military band rather than a ‘jazz band’. The concluding ‘gunshot’ effect is achieved by tutti declamation of the syllable ‘pa’.

The poem places much emphasis on dance and erratic or spinning movement in general, thus conveying the sense of disorientation and vertigo (the physiological correlative of bewilderment). Of particular interest are the lines ‘A gondola sails through an opium dream / The Earth has flown away / And dances through space / Danse excentrique’. Significantly, Haas replaced the following line (‘A hummingbird plays the jazz band’) with a new line of his own: ‘A skeletal dancer treads on tiptoes.’Footnote 93 By associating ‘danse excentrique’ with ‘danse macabre’, Haas underscored the ‘cosmic’ significance of this carnivalesque whirl, emphasizing the confrontation and intermingling of life and death.

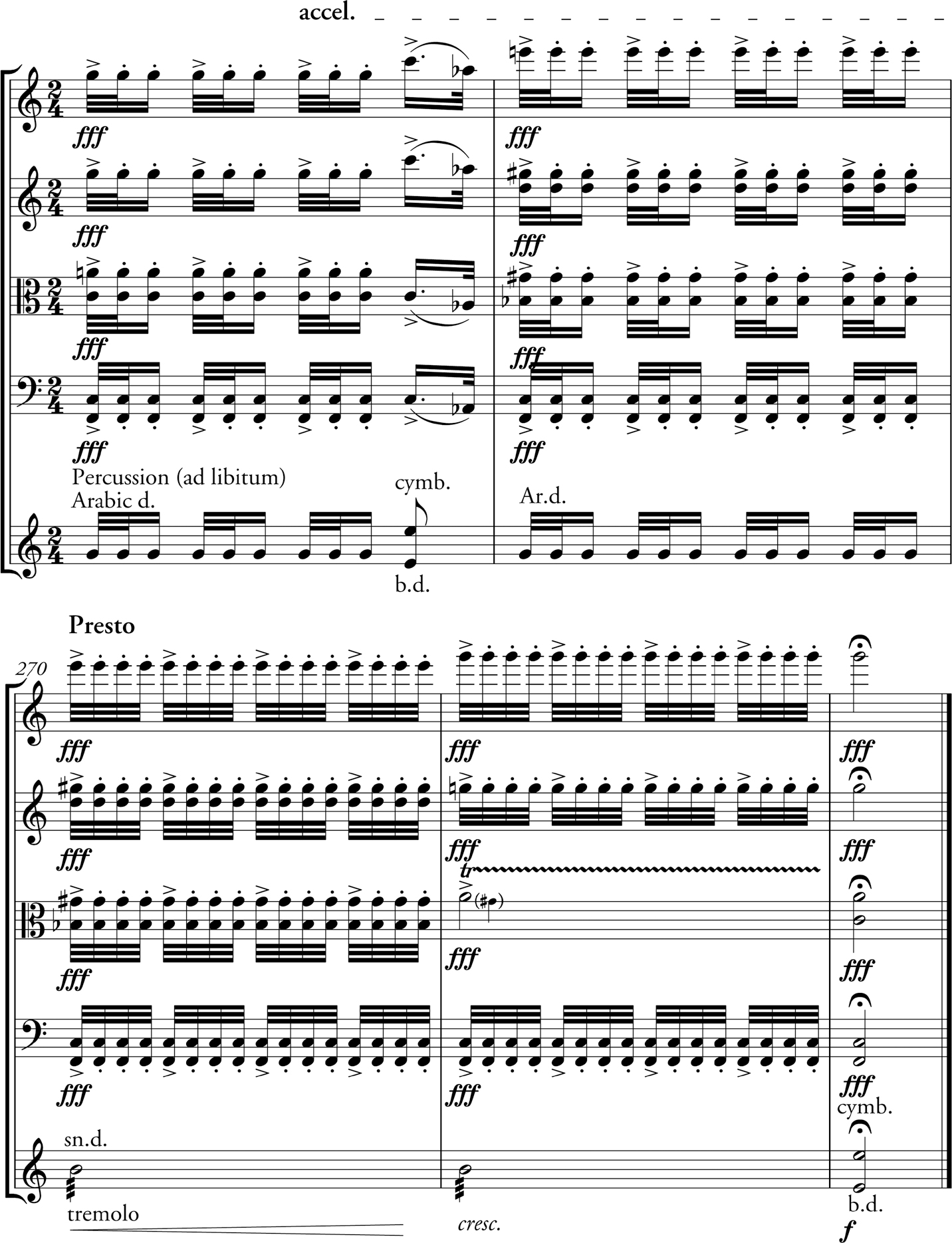

‘Danse excentrique’ (with or without the element of ‘danse macabre’) is an important topic which appears throughout Haas's oeuvre from the mid-1920s to the early 1940s. The earliest example I have found is the ‘rumba’ theme from the last movement of the quartet ‘From the Monkey Mountains’, ‘The Wild Night’ (see Example 15). This theme betrays some significant similarities (namely the ‘angular’ melody with pentatonic basis, and the ‘hopping’ gesture of staccato quavers) to the central theme of the male chorus Karneval (see Example 16). Here, the lyrics ‘four left legs, a red-green spiral’ suggest a kind of ‘eccentric dance’ (the ‘red-green spiral’ may be associated with the colourful outfits of the clowns mentioned in the next line of the poem). This theme, in turn, later became the basis of the third movement of Haas's Wind Quintet, op. 10 (1929), significantly entitled ‘Ballo eccentrico’ (see Example 17).

Example 15. ‘Rumba’ theme, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, fourth movement, bars 19–22.

Example 16. Pavel Haas, male chorus Karneval (Carnival), op. 9, bars 19–21. Two manuscript scores deposited in the Moravian Museum, Brno, Department of Music History, sign. A 22.730b, A 54.252.

Example 17. Pavel Haas, Wind Quintet, op. 10, 1929 (Tempo Praha; Bote & Bock / Boosey & Hawkes, 2nd rev. edn, 1998), third movement, bars 7–10, flute, clarinet and bassoon.

Manifestations of this topic can also be found in Haas's later works. However, a detailed discussion of these works would require adjustments to the interpretative framework used in this article, which is designed to fit specifically the context of the 1920s, underpinned by Poetism. Although the third movement – ‘Danza’ – of Haas's 1935 Piano Suite can still be understood more or less in terms of the life-affirming (Bakhtinian) carnivalesque imagery of Poetism, the second movement of his wartime Symphony (1940–1), which revisits the topic of the ‘danse macabre’, inescapably veers closer to the life-threatening pole of the grotesque.Footnote 94

‘The Wild Night’

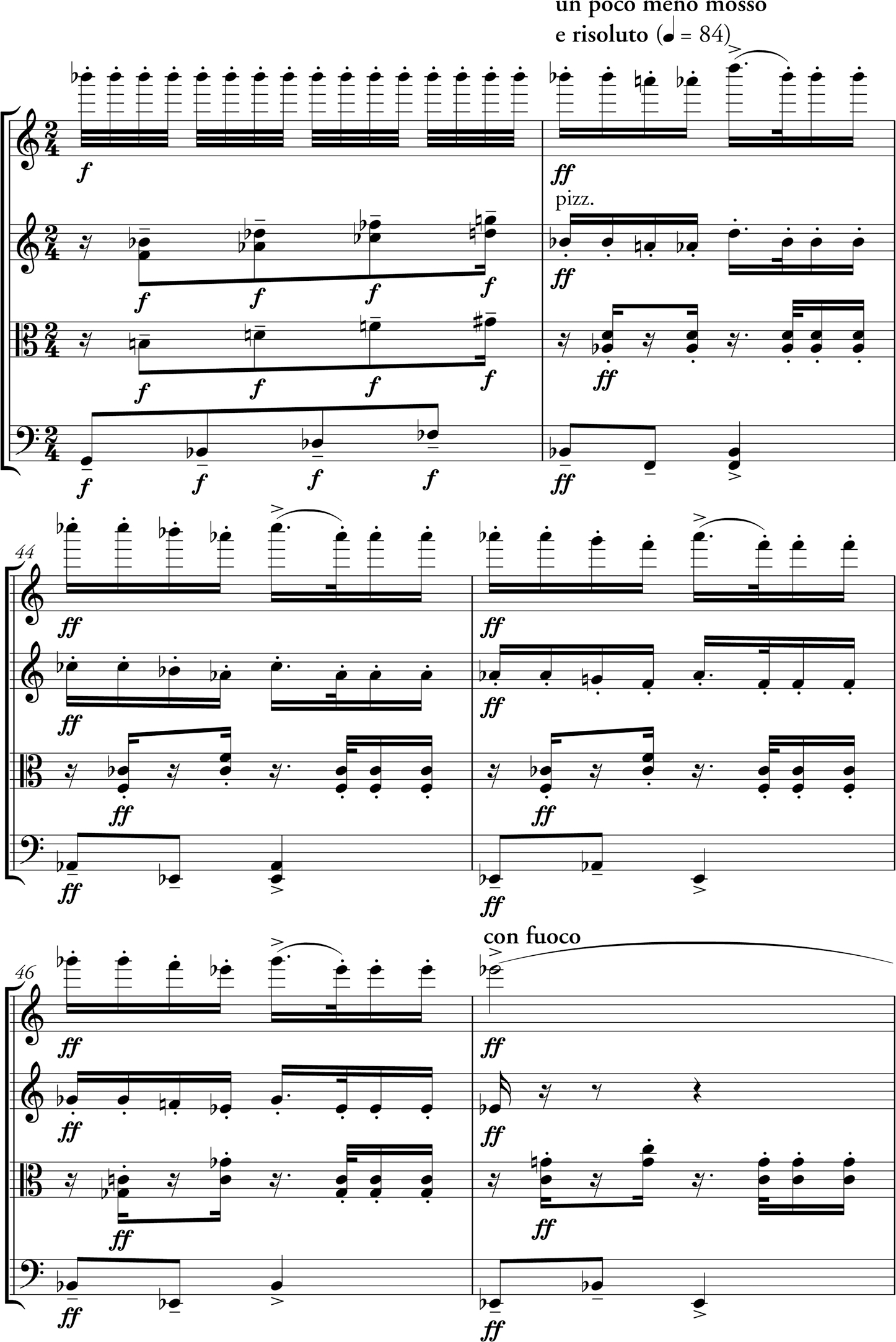

Taking into account its historical and intertextual context, I argue that the last movement of Haas's string quartet ‘From the Monkey Mountains’ – ‘The Wild Night’ – is preoccupied with the topic of carnival. The movement's title and Haas's reference to ‘the exuberance of a sleepless night of revelry’ in his commentary are both consistent with this theme. However, one wonders whether the ‘revelry’ should be imagined as taking place in a village barn (as Haas's commentary implies) or in a city bar (as the contextual evidence suggests). The composer alludes to a variety of incongruent musical idioms linked solely by the topic of dance. There is no trace of ‘jazz’ in the movement's opening. Rather, ‘The Wild Night’ begins with a distinctly Janáčekian introduction (see Example 18).

Example 18. Janáčekian introduction, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, fourth movement, bars 1–5.

Rapid trills, agitated sul ponticello bowing, surges of short motifs, all these are devices typically used by Janáček to evoke dramatic tension. Comparison with a passage from the second movement of Janáček's 1923 String Quartet no. 1 is illustrative (see Example 19). The introduction culminates in a Janáčekian folk dance of frantic, violent character, articulated by heavy accentuation, played sul ponticello and featuring double stops, restless trills and ‘savage’ augmented seconds (see Example 20). The Janáčekian introduction suddenly gives way to what might be called a ‘rumba’ theme, judging from the characteristic 3 + 3 + 2 rhythmic pattern (see Example 21).Footnote 95 This theme displays properties suggestive of the grotesque. It is marked by an ambiguity between major and minor mode resulting, as in the previous movements, from the ‘blues-scale’ inflection of particular scale degrees. Although the major third (G–B♮) dominates at first, the theme concludes with three violent G minor blows. In its subsequent reiterations, the theme is frequently distorted by ending on a ‘wrong’ note, particularly one a semitone away from the expected ‘tonic’. The awkwardness of motion, characteristic of the grotesque, is conveyed by the ‘angular’ melodic design of the theme, which is marked by wide leaps, and by the irregular 3 + 3 + 2 rhythmic pattern encapsulating the incongruity between duple and triple metre.

Example 19. Comparison with Janáček. Janáček, String Quartet no. 1, second movement, bars 132–9.

Example 20. Folk dance allusion, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, fourth movement, bars 10–12.

Example 21. ‘Rumba’ theme, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, fourth movement, bars 19–22.

The third distinct dance topic, polka, appears in what might be called the ‘trio’ section.Footnote 96 By Haas's time, the polka was a rather old-fashioned social dance, which nonetheless was still very popular in the realm of semi-folk dance music associated with brass bands.Footnote 97 Haas's allusion to the dance is made to sound banal by the excess of ‘redundant’ musical material such as repetitions, fillings and stock accompaniment patterns (the alternation of arco and pizzicato in the cello is analogous to the onomatopoeic use of ‘bum – džin’ in Karneval). In this respect, it is similar to the ‘circus’ section of the second movement (see Example 22). Furthermore, Haas may be alluding to a particular scene from Bedřich Smetana's famous opera The Bartered Bride (which retained canonical status in Czech music throughout the interwar period). Following the so-called ‘March of Comedians’, which marks the arrival of a circus troupe in the village, a preview performance takes place, accompanied by ‘Skočná’.Footnote 98 The three-note accompaniment pattern in the viola part (Example 22), which Haas highlights by obstinate repetition, can be seen as a trivial paraphrase of the similarly repetitive motif in the middle section of Smetana's ‘Skočná’ (see Example 23b).

Example 22. The satirical polka, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, fourth movement, bars 152–9.

Example 23. Bedřich Smetana, The Bartered Bride (Prague: Editio Supraphon, 1982, piano reduction), ‘Skočná’: (a) bars 138–43 (opening) and (b) 223–30 (middle section).

Haas's treatment of the ‘rumba’ theme is highly characteristic. As in the second movement, the theme keeps returning in ever shorter rhythmic values. Particularly interesting is the moment when the theme is projected simultaneously in three superimposed rhythmic strata: quavers in the second violin, semiquavers in the cello and demisemiquavers in the first violin (see Example 24). Through its repetitiveness, this section suggests mechanical revolving, which, in turn, evokes a spinning carousel or barrel organ, both of which are typical attributes of the fairground. The multi-layered presentation of the theme resembles an image of wheels within wheels or a view through a kaleidoscope. The semblance of multiple vision suggests disorientation and vertigo, typically induced by excessive spinning motion (such as dancing or riding on a carousel).

Example 24. ‘Rumba’ theme superimposed in different rhythmic layers, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, fourth movement, bars 71–4.

The last stage of the ‘development’ of the ‘rumba’ theme is its liquidation. Example 22 shows the theme subjugated into the metrical context of a polka, devoid of its original 3 + 3 + 2 accentuation. Shortly afterwards, the theme reappears in demisemiquavers, the rapid succession of which is reminiscent of the opening of Smetana's ‘Skočná’ (see Example 23a). The process of the theme's liquidation is finalized by its reduction to a mere rhythmic pulse (see Example 25). Thus, after the theme's rhythmic identity has been washed off, the melodic element is likewise eradicated, and all that remains is the germinal rhythmic motif, which is repeated obsessively. Even the element of pitch is partly suppressed: the instruments are instructed to play col legno, alternating with the percussion. The following ‘furioso’ brings back the ‘polka’ recast into 3/8 metre, which underscores the effect of a dizzying whirl. The motif is progressively shortened until it is ultimately ‘liquidated’ like the rumba theme, whereupon all movement comes to a stop.

Example 25. ‘Liquidation’ of the ‘rumba’ theme, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, fourth movement, bars 164–7; 175–8.

Having pushed the delirious frenzy to the point of collapse, Haas inserts a four-part arrangement of his own song dedicated to a beloved girl.Footnote 99 There could hardly be a greater contrast in terms of the ‘Andante’ tempo marking, the soft colour of the strings playing con sordino, the homophonic texture and the tonal clarity (see Example 26). However, at the end of the song's second iteration, the ethereal vision dissolves with the onset of the concluding ‘furioso’ section, which brings the previously interrupted dynamic escalation to a climax. Once again, all the motivic content is gradually eliminated until there is nothing left but the demisemiquaver rhythmic pulse (see Example 27).

Example 26. Quotation of Haas's early song, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, fourth movement, bars 205–12.

Example 27. Motoric ending, Haas, String Quartet no. 2, fourth movement, bars 268–72.

The carnivalesque mood of ‘The Wild Night’ results largely from the use of highly fragmentary and repetitive material, often superimposed in stratified textures. Not only does the repetition and accumulation of material, which becomes redundant and banal, connote simple-mindedness,Footnote 100 it tends to become ever more obsessive and violent. The exaggeration of stereotypical dance-like accompaniment figures and repetitive rhythmic patterns functions as a means of hyperbolic distortion of the topic of dance and bodily movement in general, conveying the sense of a delirious rapture. This accumulation of momentum is conjoined with distortion and degeneration of the musical ‘bodies’: note the ‘development’ of the rumba theme, which is first stripped of its essential traits and ultimately destroyed. The initial merriment draws ever closer to frenzy and the whirl of dance is exaggerated to the point of collapse, eliciting a hallucination.

Conclusion: the play of polarities and incongruities

The positioning of the contrasting section in the last movement refers to the ‘escalation–repose–finale’ pattern of the first movement, which, moreover, applies to the quartet as a whole. The third movement (‘The Moon and I’), which includes a quotation of the ‘slow’ section of ‘Landscape’, thus appears as a larger-scale ‘repose’ section inserted between two emphatically dynamic movements. However, it is important to realize that the essence of the schema observed here is the juxtaposition of polar opposites. The ‘fast–slow–fast’ model is but one manifestation of this generic principle; other binaries include ‘light/darkness’, ‘joy/sadness’, ‘sincerity/irony’, ‘seriousness/farce’ and so on.

The work as a whole is deliberately heterogeneous in character. The first movement, despite its programmatic inspiration, is rather serious and abstract in its focus on the development of the form-constitutive dynamic trajectory. The second movement, on the other hand, uses similar techniques based on rhythmic diminution to create a farcical musical caricature. The juxtaposition of the two encapsulates Teige's duality of Constructivism and Poetism. Similarly, the contrast between ‘The Moon and I’ and its surrounding movements brings into focus a number of characteristically modernist incongruities. This can be explained by analogy with the contrasting episode within ‘The Wild Night’.

The dominant carnivalesque character of ‘The Wild Night’ is contrasted (yet, in a way, enhanced) by the insertion of Haas's amorous song. This section, metaphorically speaking, throws a spotlight on an individual, singling him out from the crowd, suspending the surrounding rave, and revealing his or her inner subjective experience. This is a moment of authenticity and sincerity; it is devoid of all the irony, masquerade and role-playing inherent in carnival. The section thus offers a statement about the challenge posed by modern cultural reality to the human subject and the viability of subjective expression (here confined to the realm of ‘hallucination’ functioning as quotation marks). However, the resulting effect is not one of Expressionist despair; the carnivalesque celebration of modernity is subtly qualified but not subverted. After all, to paraphrase Teige, Haas's piece was ‘born […] in a world which laughs; what does it matter if there are tears in its eyes?’

Juxtaposition of incongruities (binary or not) is a salient feature of carnivalesque imagery. It is therefore significant that in ‘The Wild Night’ Haas juxtaposes musical idioms that are incongruous in terms of style and that are associated with different sociocultural contexts. Thus, the rumba theme with its ‘oriental’ pentatonicism, ‘South American’ rhythmic pattern and ‘African American’ blues-scale inflection, appears next to the ‘east European’ folk modality of the Janáčekian introduction. Janáček's folk primitives and Smetana's rather old-fashioned comedians and modern cosmopolitan ‘jazz-band’ lovers all take part in the dizzying whirlpool of dance. ‘The Wild Night’ thus appears as a carnivalesque allegory of the perplexing heterogeneity of the modern world, disorientating and potentially threatening, replete with contradictions that cannot be reconciled but that can be rendered harmless through the principle of laughter.

As ‘The Wild Night’ constitutes the climax of the piece, carnival assumes prominence as a point of view, from which all the characteristic and culturally connoted features, contrasts and contradictions of the work are regarded. Thus, carnival functions in Haas's work not only as a prominent topos of Poetism but also as a world-view, a pertinent metaphorical characterization of the particular culture from which Haas's quartet emerged and of which it remains a testimony.