1. Introduction

Students in immersion reach a higher competence level than those in traditional (non-immersion) instruction as far as practical knowledge of the language, willingness to speak, and attitude towards other languages are concerned (Lyster Reference Lyster2007, Bergroth Reference Bergroth2015). However, Canadian studies (Genesee Reference Genesee1987; Harley Reference Harley1993, Reference Harley, Doughty and Williams1998) have revealed challenges with grammatical accuracy, suggesting that immersion methodology still requires development (Lyster Reference Lyster2007). Finnish immersion research has been multifarious (Bergroth & Björklund Reference Bergroth, Björklund, Tainio and Harju-Luukkainen2013), but grammatical competence has hitherto gained less attention.

This study aims to explore how Finnish-speaking immersion students express grammatical gender (henceforth gender) in noun phrases (henceforth nps) at the end of primary school (12 years old) and at the end of secondary school and immersion (15 years old)Footnote 1 compared to non-immersion students. The analysis is restricted to gender within NPs, which thus excludes gender agreement in predicate complements. Canadian immersion learners of French (Harley Reference Harley, Doughty and Williams1998; Lyster Reference Lyster2004, Reference Lyster2010) use inaccurate gender, implying that it cannot be acquired only through communication, in which communicatively expendable categories like gender tend to be ignored (N. Ellis & Wulff Reference Ellis, Wulff, VanPatten and Williams2015). Also, gender is often challenging for learners of Swedish as a second language (L2), even through the advanced stages (Hyltenstam Reference Hyltenstam, Hyltenstam and Lindberg1988, Reference Hyltenstam and Harris1992), so this is also likely to resonate with Finnish-speaking immersion students learning L2 Swedish.

Housen & Simoens (Reference Housen and Simoens2016) distinguish between feature-related (caused by inherent properties of a linguistic construction, e.g. frequency), context-related (caused by differences in learning conditions, e.g. immersion vs. traditional instruction) and learner-related (individual characteristics, e.g. age) factors behind Second language acquisition (SLA). This study views gender from all three perspectives. An analysis of the production by L2 learners offers valuable information about which aspects of gender and gender agreement are most challenging and, hence, what explicit instruction should focus on, i.e. regarding feature-related factors. Comparisons between immersion and non-immersion students emphasise context-related factors, and between younger and older immersion students, they highlight learner-related factors. Didactic interventions appear to help the learners focus on gender, leading to increased accuracy (Harley Reference Harley, Doughty and Williams1998, Lyster Reference Lyster2010). It is thus vital to analyse Finnish L2 learners of Swedish in order to establish a comprehensive picture of their ability to mark gender. It is also crucial to study immersion students separately from other L2 learners as this intensive and long-lasting learning programme combines rich input and meaningful interaction that makes it different from other methods.

2. Gender in second language acquisition

2.1 Gender in Swedish

Swedish nouns are either uter (indefinite article en) or neuter (indefinite article ett; Teleman, Hellberg & Anderson Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999a); Swedish is said to be less complex than, e.g. Norwegian (three genders; Faarlund, Lie & Vannebo Reference Faarlund, Lie and Vannebo2006). Corbett (Reference Corbett, Dryer and Haspelmath2013) claims that gender always has a semantic core but Svenska Akademiens Grammatik [Grammar of the Swedish Academy] states that, in Swedish, it usually lacks connection to the meaning of the word and semantic weight, as it causes shifts in the meaning of a noun only in rare cases (e.g. en plan ‘open place, plan’, ett plan ‘plane, floor, aeroplane’). Many nouns referring to humans are uter, but, e.g. barn ‘child’ is neuter. Nouns ending in -ing (e.g. en tidning ‘a newspaper’) are uter, but in most cases, there is no way to tell gender from the form of the noun, so one must learn the gender by rote (Teleman et al. Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999a; see also Audring Reference Audring, Garbo, Olsson and Wälchli2019). Approximately 75% of all nouns in Swedish are uter; this distribution holds true for both oral and written, formal and informal discourse (see Bohnacker Reference Bohnacker, Håkansson, Josefsson and Platzack2003 for an overviewFootnote 2 ). Even L2 Swedish learners appear to be sensitive to input frequencies and use uter by default (Bohnacker Reference Bohnacker, Håkansson, Josefsson and Platzack2003; see also Section 2.3).

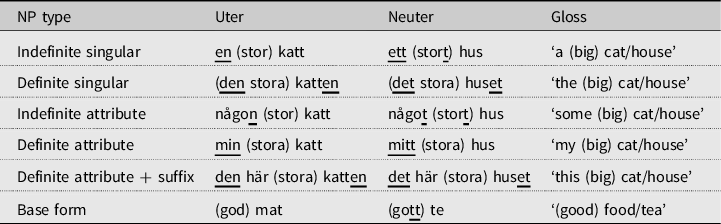

Gender is inherent in nouns (Teleman et al. Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999a), manifested in Swedish by different grammatical morphemes (Table 1). The letter n often recurs in gender marking in uter, as the letter t does in neuter. Gender marking is especially consistent in neuter (see Audring Reference Audring, Garbo, Olsson and Wälchli2019). All examples are singular as modern Swedish lacks gender marking in plural (Teleman et al. Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999a). In this article, we distinguish between simple gender markers (e.g. indefinite article) and gender agreement occurring in NPs with more than one gender marker.

Table 1. Swedish NPs with gender markers at the phrase level. Gender markers are underlined.

In indefinite singulars, gender is marked by an indefinite article (see Table 1). In contrast, the definite singular form is built by adding a definiteness suffix to the noun (henceforth suffix; Teleman et al. Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999a:96–101, 407);Footnote 3 gender marking is polyfunctional and intertwined with a definiteness marking. The suffix occurs in both countable and uncountable nouns, whereas an indefinite article is mostly used only with the countable ones. The definite front article (den, det, henceforth definite article) only occurs in definite NPs with an adjective attribute (henceforth adjective). Thus, these Swedish NPs can rightly be called ‘asymmetrical and abstruse’ (Philipsson Reference Philipsson, Hyltenstam and Lindberg2004:125, our translation). The adjective attributes in Table 1 are marked with brackets as they always are optional. In semantically definite NPs, adjectives are syncretic for uter and neuter (the suffix -a) (Teleman et al. Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999a). Many definite (e.g. possessive) and indefinite pronominal attributes (henceforth pr attributes) also inflect for gender, and some are constructed with a definite noun; thus, these NPs have two gender markers.

Uncountable nouns (mat ‘food’, te ‘tea’) occur frequently in the indefinite singular without an article. Countable nouns have this base form when the referent class is more important than its individual entity (e.g. bil ‘car’ in Har du bil? ‘Do you have a car?’; Teleman et al. Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999a, b). This form is especially common in Swedish (Pettersson Reference Pettersson and Gårding1976). In such NPs, the only element marking gender is the potential adjective. Certain PR attributes, such as the possessive pronouns hans/hennes/deras ‘his/her/their’, and all genitive attributes (e.g. Annas katt/hus ‘Anna’s cat/house’) are indeclinable too. As the NPs are constructed with definite adjective and indefinite noun forms, they do not manifest gender.

2.2 Usage-based grammar and challenges of grammatical gender

The usage-based approach sees SLA as a cognitive process of determining linguistic constructions in the input, using the same processes as in any cognitive activity, i.e. input is the most important source for SLA. These constructions are form-meaning mappings without any strict dichotomy between lexicon and grammar, with a fluctuating grade of abstraction (a continuum from concrete utterances to abstract productive formulae like [possessive attribute + indefinite noun]) and complexity (a continuum from morphemes, such as gender markers, to words and longer utterances, such as whole NPs). In time, learners more or less consciously discover regularities in constructions and start varying them with their communicative needs as a starting point, ultimately discovering the abstract formulae behind them. They abstract on how the parts link together and contribute to the construction’s meaning. That is, grammar is an implicit, cognitive organisation of a learner’s actual language experience that develops by adding new constructions to the inventory (Bybee Reference Bybee, Robinson and Ellis2008, Nistov, Gustafsson & Cadierno Reference Nistov, Gustafsson, Cadierno, Gujord and Randen2018).

Input frequencies are crucial for SLA: the more a learner confronts a construction, the more entrenched and accessible its mental representation becomes for language use, and the learner’s perception system begins to expect certain constructions in certain contexts (N. Ellis & Wulff Reference Ellis, Wulff, VanPatten and Williams2015, Audring Reference Audring, Garbo, Olsson and Wälchli2019). Frequent sequences can be acquired as if they are independent of a general pattern; thus, they can help the learner analyse similar, less frequent forms (Bybee Reference Bybee, Robinson and Ellis2008, N. Ellis & Wulff Reference Ellis, Wulff, VanPatten and Williams2015, Wray Reference Wray2012, Prentice et al. Reference Prentice, Loenheim, Lyngfelt, Olofsson, Tingsell, Gustafsson, Holm, Lundin, Rahm and Tronnier2016). However, high-frequency elements such as gender markers tend to have low salience; and are thus difficult to notice in the input (Goldschneider & DeKeyser Reference Goldschneider and DeKeyser2001, Bybee Reference Bybee, Robinson and Ellis2008, N. Ellis Reference Ellis2016). Both immersion and communicative non-immersion language learning emphasise understanding the message more than form (Jaakkola Reference Jaakkola, Kaikkonen and Kohonen2000), and hence, learners may not perceive the grammar (DeKeyser Reference DeKeyser2005). This is why highly frequent grammatical morphemes such as articles and suffixes are difficult to acquire in an L2: one cannot acquire what one has not noticed (Goldschneider & DeKeyser Reference Goldschneider and DeKeyser2001).

SLA in immersion begins early on, mostly occurring spontaneously as an internalisation of rules when the learner focuses on meaning. Thus, parallels are seen between first and second language acquisition, although the first language (L1) impacts how L2 learners notice constructions in the input (N. Ellis & Wulff Reference Ellis, Wulff, VanPatten and Williams2015). One’s experience with the L1 can hamper SLA, especially in the earlier stages of acquisition, if the L1 lacks, e.g. grammatical morphemes occurring in the L2 (Jarvis Reference Jarvis2002, Bybee Reference Bybee, Robinson and Ellis2008, Collins et al. Reference Collins, Trofimovich, White, Cardoso and Horst2009). As Finnish lacks grammatical gender (Karlsson Reference Karlsson2017), Finnish-speaking L2 learners of Swedish may also have difficulty noticing gender markers in the input.

According to DeKeyser (Reference DeKeyser2005), challenges acquiring L2 grammar are explainable by meaning, form or a combination of the two. As a highly abstract notion, gender is often used as the epitome of a construction with a challenging meaning, especially for L2 learners whose L1 lacks it (DeKeyser Reference DeKeyser2005). Although gender is said to always be rooted in semantics, it is doubtful whether it is possible to formulate clear and concise rules for this without many exceptions and advanced grammatical terminology for L2 learners (see R. Ellis Reference Ellis2006). The fact that uter is more frequent than neuter in Swedish also impacts acquisition; L2 learners are likely to use uter as the default gender (Bohnacker Reference Bohnacker, Håkansson, Josefsson and Platzack2003).

Challenges with form are mainly connected to formal complexity. In our study, complexity occurs in NPs with gender agreement, i.e. with several morphemes that need to be put in the right places (see DeKeyser Reference DeKeyser2005). Due to allomorphic variation, however, certain letters recur in uter and neuter, which might ease acquisition (see Audring Reference Audring, Garbo, Olsson and Wälchli2019). Challenges in the relationship between form and meaning are connected with redundancy (occurrence of semantically expendable morphemes) or opacity (different forms having the same meaning; DeKeyser Reference DeKeyser2005). As Table 1 above indicates, redundancy is typical of Swedish NPs with gender agreement. Opacity can be detected in the fact that both indefinite articles and suffixes are polyfunctional (see Audring Reference Audring, Garbo, Olsson and Wälchli2019): gender and definiteness are intertwined. Moreover, gender marking is particularly due to the high frequency of the base form often neutralised in the input (Pettersson Reference Pettersson and Gårding1976), which impedes the feature’s consistency (see Audring Reference Audring, Garbo, Olsson and Wälchli2019) and makes it difficult to notice in the input. An L2 learner might know a word without knowing its gender, for example if they have encountered it only in its base form in the input. Learners in non-immersion, however, also learn vocabulary by reading word lists, which is likely to make gender more salient (Toropainen, Lahtinen & Åberg Reference Toropainen, Lahtinen and Åberg2020). In short, many factors connected to gender contribute to the challenges experienced by L2 learners of Swedish.

2.3 Previous research in the acquisition of gender in Scandinavian languages

Gender appears to be rather unproblematic for L1 learners, although they cannot explain how they choose accurate gender (Tucker, Lambert & Rigault Reference Tucker, Lambert and Rigault1977, Corbett Reference Corbett1991). Svartholm (Reference Svartholm1978) and Plunkett & Strömqvist (Reference Plunkett and Strömqvist1990) found that young Swedish children acquiring their L1 rarely make mistakes in gender. This is because their first NPs are definite singulars, in which the definiteness suffix is also marked for gender; they acquire gender when acquiring the communicatively central definiteness marking. Their NPs are not especially complex; for example, they do not produce NPs with adjectives (Andersson Reference Andersson and Strömqvist1994). L2 learners, conversely, often act rather arbitrarily when expressing gender (DeKeyser Reference DeKeyser2005). Next, we summarise the central results from previous research in Swedish and other Scandinavian languages as L2s.

A recurring result from studies with different elicitation methods and with informants with varying L1s is that the suffix is mastered at a higher level of competence than other gender markers irrespective of the gender, as many definite forms are acquired as wholes (Andersson Reference Andersson1992, oral data from 16 informants with 10 different L1s and different ages of onset; Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998, written data from 342 Finnish-speaking students in upper secondary school). Similar results have been found in L2 Norwegian (n=500, Ragnhildstveit Reference Ragnhildstveit2017, Reference Ragnhildstveit2018). The second easiest gender marker is the indefinite article, whereas adjectives and definite articles reach lower scores (Andersson Reference Andersson1992, Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998).

Previous studies have found that the uter gender is mastered at a higher level of accuracy than the neuter (Andersson Reference Andersson1992, Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998). Uter nouns used by Andersson’s (Reference Andersson1992) adult informants are relatively accurate, but they tend to overuse them more than children, as they are able to draw conclusions from the input. Overuse of the uter gender has also been documented in L2 Danish (Braüner Kappelgaard & Bruun Hjorth Reference Braüner Kappelgaard and Bruun Hjorth2017). Studies with informants with different L1s (Andersson Reference Andersson1992, Ragnhildstveit Reference Ragnhildstveit2017) did not manifest sharp differences between the language groups. Andersson (Reference Andersson1992) also states that children who started learning before the age of three mastered gender better than those who started later, but the latter also used more complex language, i.e. they had more potential for inaccuracies.

Lahtinen (Reference Lahtinen1998) also stated that only 6% of inaccuracies in NPs with agreement were of the type where one of the elements has inaccurate gender (e.g. *ett stor katt ‘a big cat’ or *en stor-t hus ‘a big house’). Gender agreement within an NP was also touched upon by Glahn et al. (Reference Glahn, Håkansson, Hammarberg, Holmen, Hvenekilde and Lund2001), whose informants (adult L2 learners of Swedish, Norwegian and Danish (n=47)) produced an [indefinite article + adjective] in an oral test. Informants with all three L2s mastered gender agreement to a lesser extent than the semantically motivated number agreement, and uter appeared to be a default gender, overused in both articles and adjective attributes.

3. Data and method

3.1 Data collection and informants

The data consist of 200-word written narratives (entitled ‘My dream journey/holiday’). Informants were Finnish-speaking 6th graders (12 years old, n=137) and 9th graders (15 years old, n=163) enrolled in Swedish immersion (henceforth IM6 and IM9). The starting age for immersion varies in different parts of Finland (Bergroth Reference Bergroth2007), but all immersion students in this study had started learning Swedish at daycare. The proportion of instruction in Swedish varied in different grades (Bergroth & Björklund Reference Bergroth, Björklund, Tainio and Harju-Luukkainen2013), but IM9 received 50% of all its instruction in Swedish. The standards set for competence in Swedish vary in different municipalities, but they are higher than in the non-immersion instruction context: pupils have to reach B-level on the CEFR scale in order to reach a level of ‘good’ at the end of secondary school (Bergroth Reference Bergroth2015).

The texts by immersion students are compared to those by 16-year-old Finnish-speaking 1st graders in upper secondary schools (henceforth CG, n=93). They have received non-immersion instruction in Swedish since the age of 11,Footnote 4 so they have been learning Swedish at school for six years. In Finland, 1st graders in upper secondary schools are the youngest non-immersion L2 Swedish learners to write longer texts and are therefore comparable to IM9. CG had received instruction in around 450 Swedish lessons in the comprehensive school (Government Decree 422/2012, FNBE 2014a), and they are expected to reach CEFR level A.2 in writing to reach a score of ‘good’ at the end of secondary school (FNBE 2014b). This is also likely to be their level after the first year in upper secondary school, as ‘good’ on the test in Swedish in the Matriculation Examination (i.e. the national final exam of the upper secondary school in Finland) corresponds approximately to a level no higher than a ‘low B1’ (Juurakko-Paavola & Takala Reference Juurakko-Paavola and Takala2013). During the first year in upper secondary school, CG had taken three of the six obligatory coursesFootnote 5 in Swedish (FNBE 2015).

Although Swedish is one of the official languages of Finland, students in non-immersion settings learn Swedish, de facto, as a foreign language. Teaching materials and teachers are their principal sources of input as the students typically lack everyday contact with Swedish. Finnish immersion students, conversely, learn Swedish mainly as a result of communication. Both informant groups started learning English at the age of nine. Hence, IM6 and IM9 learned Swedish as their L2, whereas CG students learned Swedish as a third language (L3).

3.2 Method

Both NPs with accurate and inaccurate gender are included in a traditional analysis of obligatory occasions (see R. Ellis & Barkhuizen Reference Ellis and Barkhuizen2005). In an analogy with Andersson (Reference Andersson1992) and Lahtinen (Reference Lahtinen1998), we use the informants’ gender markings as our starting point, compare them to the target language forms and classify them as accurate/inaccurate. As gender is an inherent language category (Teleman et al. Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999a), it is possible to judge gender accuracy, although the form produced by a learner would not exist (e.g. en *katten includes both an indefinite article and an unnecessary suffix, but both manifest accurate gender).

In this study, accuracy and inaccuracy refer only to gender, i.e. the analysis does not take definiteness into account.Footnote 6 Gender and definiteness, however, are practically intertwined, as articles, suffixes and many PR attributes inflect for gender. In the following, we do not consider whether the NPs of informants otherwise follow the grammatical norm; e.g. the NP den här *katt ‘this cat’ (the accurate form being den här katten) is classified as accurate as far as gender is concerned, although it lacks a suffix, as the gender can be interpreted from the PR attribute. NPs without a gender marking, e.g. NPs with a base form (see Section 2.1 above) and inaccurate NPs with omitted grammatical morphemes, have been left out of the analysis as the gender cannot be interpreted in them. The NP på *strand ‘on beach’, for example, includes an obligatory context for definite form, but as the NP lacks all gender markers, it cannot be analysed from the grammatical gender’s perspective. L2 learners’ NPs may also have additional, non-accurate elements, such as the suffix in samma *dag-en ‘same day’ (the accurate form being samma dag); this means NPs include an accurate gender marker that does not occur in standard Swedish. As the gender can be interpreted, these NPs are included in the analysis as [PR + suffix].

NPs with gender markings have been classified by marker (e.g. suffix, indefinite article, see Section 4.1 below), gender (Svensk Ordbok 1999 is used as the norm) and accuracy. The frequency of the different gender markers (e.g. suffix) and gender agreements (e.g. [definite article + suffix]) were calculated at the group level by dividing the number of certain types of nouns by the total number of nouns. The accuracy of a specific gender marker or type of gender agreement was calculated at the group level by dividing the total number of accurate (regarding noun gender) occasions by the total number of obligatory occasions (regarding noun gender) of that type. It is expected that the informants in different grades represent different competence levels. Then again, there is always individual variation, i.e. certain informants can be at a low level after a long learning time. Furthermore, accuracy does not always signify mastery. Individuals with only uter nouns in their repertoire can reach high levels of accuracy, as uter is remarkably more frequent in the language than neuter, i.e. a certain pseudo-accuracy might occur.

Pearson’s χ2 was used as a statistics test to calculate the statistical significance of the differences between the different types of gender markers and informant groups as it does not require Gaussian distribution. Our limit value of significance level is p<.05. Acquisition sequences were established in line with the principle wherein an accuracy hierarchy delivers an acquisition sequence in which a high accuracy implies early acquisition and, consequently, an easy construction (Collins et al. Reference Collins, Trofimovich, White, Cardoso and Horst2009). The central research questions (RQs) and related hypotheses (Hs) are:

-

RQ1: Which gender markers are most common in the data?

H1: The suffix is the most common gender marker in all groups, as definite singulars are so frequent in the texts by L2 Swedish learners (Nyqvist Reference Nyqvist2018a, b).

-

RQ2: Is uter easier than neuter?

H2: All groups reach higher accuracy in uter than in neuter and also overuse the uter gender (Andersson Reference Andersson1992, Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998).

-

RQ3: What kind of accuracy differences are there between the informant groups?

H3: IM9 and CG reach the same accuracy level, as previous research has shown that L2 learners in formal instruction are able to reach a high accuracy level in gender in written data (Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998).

-

RQ4: What kind of accuracy hierarchy is there between NPs with simple gender markers and NPs with gender agreement?

H4: All groups have higher accuracy with the simple gender markers (Andersson Reference Andersson1992, Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998, Ragnhildstveit Reference Ragnhildstveit2017).

-

RQ5: Is gender agreement more common in the data than its absence?

H5: When NPs with accurate gender agreement and NPs with gender agreement with inaccurate gender (e.g. Table 3 below) are added, agreement is more common than non-agreement in all groups (see Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998).

4. Results

The data consist of 10451 singular NPs. Of these, 3968 occur in IM6, 4384 in IM9 and 2099 in CG. About three-quarters of nouns produced by IM6 and CG are uter; these groups show similarities in common Swedish use (see Teleman et al. Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999a; see also Bohnacker Reference Bohnacker, Håkansson, Josefsson and Platzack2003). IM9 uses more uter nouns than the other groups (89%). In Section 4.1, we present frequencies for the different types of gender marking in our data. In Section 4.2, we deal with normative analysis.

4.1 Frequencies for gender marking

Table 2 summarises frequencies for different types and combinations occurring in the data, including the NPs without gender markers. As the table shows, the distribution of the different gender markers is rather similar in all three groups, suffixes being the most common, i.e. H1 holds. This was predictable due to the high frequency of definite singulars in the previous analysis of definiteness marking from the same data (Nyqvist Reference Nyqvist2018a, b). NPs without gender marking (e.g. base forms, NPs with indeclinable PR attributes; see Section 2.1 above) are also frequent mainly because base forms are so common in Swedish (Nyqvist Reference Nyqvist2013, Reference Nyqvist2018a, b). A minority of these occurrences are produced by omitting a suffix or an indefinite article, an inaccuracy typical for Finnish-speaking L2 learners of Swedish (Nyqvist Reference Nyqvist2013, Reference Nyqvist2018a, b).

Table 2. Frequencies (f) for different ways to mark gender in the data.

IM6 = Swedish immersion 6th graders; IM9 = Swedish immersion 9th graders; CG = Finnish-speaking 1st graders

The proportions of PR attributes (mainly possessive pronouns, e.g. min katt ‘my cat’) and indefinite articles also rise above 10%, but the other NP types, especially those with several markers, are low frequency. NPs with definite articles are especially rare (Axelsson Reference Axelsson1994; Nyqvist Reference Nyqvist2013, Reference Nyqvist2018a, b).

4.2 Normative analysis

In this section, we present our data from a normative perspective and omit the gender-neutral NPs. Hence, our analysis builds on 2845 NPs in IM6, 3393 in IM9 and 1546 in CG. Of these, 76% are uter in IM6, 81% in IM9 and 77% in CG, i.e. the uter-neuter distribution is similar to that reported in Teleman et al. (Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999a:59 ; see also Bohnacker Reference Bohnacker, Håkansson, Josefsson and Platzack2003). Thus, the informants are unlikely to avoid neuter nouns. First, we treat NPs with simple gender markers (Figure 1), and second, we treat the most common types of gender agreement (Figure 2). Complete statistical data are given in Tables A1–A6 in the appendix.

Figure 1. Accuracy scores for simple gender markers in the three informant groups.

Figure 2. Accuracy scores for the most common types of gender agreement in the three informant groups.

Figure 1 shows accuracy differences among these gender markers, but the accuracy hierarchy is similar in all groups. Suffixes (katt-en ‘the cat’, hus-et ‘the house’) have the highest accuracy in all groups (≥ 89%), similar to the findings of Andersson (Reference Andersson1992), Lahtinen (Reference Lahtinen1998) and Ragnhildstveit (Reference Ragnhildstveit2018). Definite singulars are also frequent in a corpus study on texts in L2 Swedish teaching materials (Nyqvist Reference Nyqvist2013); they occur in wordlists and paradigms, which may have prompted their acquisition in the control group. They are used significantly more accurately (Table A1) than other simple gender markers in both IM9 and CG (p<.01 in all cases in both groups) and significantly more accurately in IM6 (89%) than indefinite articles (83%), adjectives (60%) and definite articles (56%) (p<.001 in all cases).

Also, PR attributes (mainly possessive pronouns, e.g. min katt ‘my cat’, mitt hus ‘my house’) (≥ 87% in all groups) and indefinite articles (en katt ‘a cat’, ett hus ‘a house’) (≥ 82% in all groups) have high accuracy (e.g. Andersson Reference Andersson1992, Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998). However, PR attributes are used significantly more accurately than indefinite articles in immersion groups (p<.05 in both groups). Both are rather common in our data but also in the teaching materials in Swedish (Nyqvist Reference Nyqvist2013). Indefinite articles also occur in wordlists and paradigms. Adjectives (lång tid ‘long time’, vacker-t väder ‘beautiful weather’) reach significantly lower accuracies (≤ 76% in all groups) than the three easiest types of gender markers (suffixes, PR attributes and indefinite articles) in all groups (p<.001 in all cases in IM6; p<.001 in PR attribute vs. adjective in IM9 and CG; p<.05 in indefinite article vs. adjective in IM9; and p<.01 in CG).

The definite article (den stora katt ‘the big cat’, det vackra land ‘the beautiful country’) shows the lowest accuracy (≤ 65% in all groups) and is significantly more difficult than the suffix and PR attributes in all groups (p<.05 in all groups) and is also significantly more difficult than the indefinite article in IM6 and CG (p<.001). Our analysis focuses on gender, but it should be noted that NPs with a definite article as the only gender marker are usually formally incomplete (as the definite article usually occurs with an adjective attribute and a definite noun with a suffix). Hence, it is not surprising that inaccurate gender also occurs.

In most gender markers, CG reaches a higher accuracy than IM6 and IM9, whereas accuracies for IM6 are lower than for both IM9 and CG for most of the studied morphemes (Table A2), i.e. H3’s suggestion that IM9 and CG reach similar accuracies is falsified. CG reaches significantly higher scores than IM6 and IM9 for the three easiest markers (p<.001 and p<.05, respectively, for suffixes; p<.05 and p<.01, respectively, for PR attributes; p<.05 for indefinite articles in both groups). IM9 also reaches higher accuracy than IM6 in suffixes (p<.001).

When accuracies for uter and neuter are compared (Table A3), uter is typically significantly more accurate than neuter, i.e. H2 holds (p<.001 for suffix, PR attributes and indefinite article in all groups; p<.01 for adjectives in IM9; p<.05 in CG; p<.01 for definite article in IM6). Differences are nonsignificant for adjectives in IM6 and definite articles in IM9 and CG, in which accuracies for uter are also low. As neuter nouns reach a lower accuracy level, it can also be concluded that overuse of the uter gender is more common than vice versa (as in Andersson Reference Andersson1992, Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998).

In sum, NPs with simple gender markers build a similar accuracy hierarchy in all three groups. Suffix, PR attribute and indefinite article are mastered at high levels. Uter is easier than neuter, and CG usually reaches a higher accuracy than IM6 and IM9. Figure 2 summarises the accuracy scores of the most frequent types of NPs with gender agreement.

Our data show several types of constructions with gender agreement. Those in Figure 2 have at least some occurrences in IM6, IM9 and CG (see Section 4.1 below). As Figure 2 shows, different groups have different accuracy hierarchies. In IM9, the accuracy is highest (82%) in [PR attribute + suffix] (den där semester-n ‘that holiday’, det där hus-et ‘that house’), and it is significantly higher than in [indefinite article + adjective] (en stor katt ‘a big cat’, ett stor-t hus ‘a big house’) (69 %) and in [PR attribute + adjective] (någon stor katt ‘some big cat’, något stor-t hus ‘some big house’) (53%) (p<.05 and p<.001, respectively). Accuracy for [PR attribute + adjective] is also significantly lower than that for [definite article + suffix] (78%) and for [indefinite article + adjective] (69%) (p<.01 and p<.05, respectively). In IM6, the accuracy is highest (79%) in [definite article + suffix] (den stora katt-en ‘the big cat’, det stora hus-et ‘the big house’). In CG, [PR attribute + adjective] (någon stor katt ‘any big cat’, någo-t varm-t land ‘any warm country’) is most accurate (86%). However, the differences between the types are nonsignificant in IM6 and CG (see Table A4).

Differences between IM6, IM9 and CG are mainly nonsignificant (Table A5), except that CG reaches a significantly higher level of accuracy than IM9 (86% vs. 53%) in [PR attribute + adjective] (p<.05), as IM9 overuses uter more than CG does. It should be concluded, however, that H3 is falsified from this perspective, as IM9 and CG do not reach the same accuracy: the formal instruction received by CG appears to have added to the salience of gender agreement.

Uter nouns also tend to be significantly more accurate than the neuter ones (Table A3) in gender agreement (p<.05 in all cases in both IM6 and IM9 and for [indefinite article + adjective] and [PR attribute + suffix] in CG). Accuracies for neuter nouns are particularly low (≤ 29% in IM6, ≤ 33% in IM9) in immersion. Thus, it can be concluded that H2 holds and that overuse of uter is also more common than overuse of neuter in gender agreement.

Comparing simple gender markers and gender agreement (Table A6), accuracies tend to be higher for the less complex constructions, i.e. H4 holds. In all three groups, the suffix (katt-en ‘the cat’, hus-et ‘the house’) has a significantly higher accuracy (≥ 89% in all groups) than [definite article + suffix] (den stor-a katt-en ‘the big cat’) (≥ 78% in all groups) (p<.05 in IM6, p<.001 in IM9 and CG). The indefinite article (en katt ‘a cat’, ett hus ‘the house’) in immersion is significantly more accurate (≥ 82%) than [indefinite article + adjective] (en stor katt ‘a big cat’, ett stor-t hus ‘the big house’) (72%, 69%; p<.01 in both groups).

In IM6, a PR attribute as a simple gender marker (någon katt ‘some cat’, något hus ‘some house’) is significantly more accurate (87%) than both [PR attribute + suffix] (den där katt-en ‘that cat’, det där hus-et ‘that house’) (73%) and [PR attribute + adjective] (någon stor katt ‘some big cat’, något stort hus ‘some big house’) (63%) (p<.01 in both cases). The difference in IM9 is significant only in PR attribute (87%) vs. [PR attribute + adjective] (53%) (p<.001), and in CG, it is significant only in PR attribute vs. [PR attribute + suffix] (92% vs. 79%, p<.01). The only simple marker with an accuracy lower than that of [definite article + suffix] (den katt-en ‘that cat’, det hus-et ‘that house’) (≥ 78% in all groups) is the definite article (≤ 65% in all groups) (den katt ‘that cat’, det hus ‘that house’), and the difference is significant in IM6 (79% vs. 56%) and CG (83% vs. 50%) (p<.05 and p<.01, respectively).

An NP with more than one gender marker often includes both uter and neuter elements. In the following, we will study the different combinations of gender markers. Tables 3 and 4 illustrate the combinations occurring in [indefinite article + adjective], and the NPs (e.g. en stor katt ‘a big cat’) represent all NPs with the same construction, i.e. they are types, not tokens.

Table 3. Different versions of an [indefinite article + adjective] in uter NPs.

IM6 = Swedish immersion 6th graders; IM9 = Swedish immersion 9th graders; CG = Finnish-speaking 1st graders

Table 4. Different versions of an [indefinite article + adjective] in neuter NPs. Brackets mark the optional adjective attribute.

IM6 = Swedish immersion 6th graders; IM9 = Swedish immersion 9th graders; CG = Finnish-speaking 1st graders

In uter nouns, the accurate form is most common in all groups. The most common type of inaccuracy in immersion is the consistent use of the neuter form – agreement is more common than no agreement. Thus, the data do not differ from Lahtinen (Reference Lahtinen1998), and H5 holds. The lack of agreement is most common in CG (11% of NPs), where the most common inaccuracy is the use of the neuter form of the adjective. This also sometimes occurs in immersion. In IM9 and CG, there are also sporadic occasions of an inaccurate indefinite article.

Neuter nouns clearly deviate from uter ones. Accurate agreement is most common only in CG, whereas most informants in immersion consequently overuse the uter. Hence, the data do not diverge from the results of Lahtinen (Reference Lahtinen1998), and H5 holds. Also, H2 holds, as agreement with accurate gender is more common in uter, but H3 is falsified: IM9 and CG do not reach the same accuracy. The uter form of the indefinite article occurs sporadically in both IM6 and CG, and an inaccurate form of the adjective has one occurrence in both IM9 and CG. Lack of agreement, again, is most common in CG.

Tables 5 and 6 summarise the different combinations in [definite PR attribute + suffix] and [definite article + suffix], i.e. two types of definite NPs.

Table 5. Different versions of a [definite PR + suffix] and a [definite article + suffix] in uter NPs. Brackets mark the optional adjective attribute.

IM6 = Swedish immersion 6th graders; IM9 = Swedish immersion 9th graders; CG = Finnish-speaking 1st graders

Table 6. Different versions of [definite PR + suffix] and [definite article + suffix] in neuter NPs. Brackets mark the optional adjective attribute.

IM6 = Swedish immersion 6th graders; IM9 = Swedish immersion 9th graders; CG = Finnish-speaking 1st graders

Accurate agreement is the most common in all three groups, and the consequently inaccurate gender occurs only in IM9. Hence, H5 holds. Non-agreement with an inaccurate PR attribute/definite article is relatively common in IM6 and CG but rare in IM9, and the inaccurate suffix is exceptional in uter nouns, as definite singulars are often acquired as unanalysed wholes: the fact that informants occasionally produce an [indefinite article + suffix, e.g. en katt-*en ‘a the cat’] supports this perception (Nyqvist Reference Nyqvist2013, Reference Nyqvist2018a, b). Because nouns generally have an accurate suffix in NPs with non-agreement, they may be acquired as unanalysed wholes (see also Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998, Ragnhildstveit Reference Ragnhildstveit2018).

Neuter nouns also deviate from uter ones in definite NPs. Accurate agreement is most common in IM6 and CG, but the percentage surpasses 50% only in CG; i.e. IM9 and CG do not reach the same level, which falsifies H3. The type with a consequent inaccurate gender marking is most common in IM9, but it is also common in the two other groups. This is not surprising, as overuse of the uter is common in the data (Andersson Reference Andersson1992, Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998). Hence, gender agreement is more common than lack of it and H5 holds. Still, lack of agreement is more common than in uter. In non-agreement, an inaccurate form of the PR attribute/definite article is common in all groups.

In sum, IM6, IM9 and CG have different profiles in gender agreement. Uter is also easier than neuter in these more complex NPs, but differences between the groups lack statistical significance. By contrast, accuracies for gender agreement are generally significantly lower than those for simple gender markers – NP complexity is a crucial part of the acquisition process. In many cases, the form of the adjective is the typical challenge.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Gender is often presented as challenging for L2 learners due to its semantic opacity and minimal communicative weight. In addition, gender markers are polyfunctional morphemes with low salience. This has been found, e.g. in Canadian immersion studies (Harley Reference Harley, Doughty and Williams1998; Lyster Reference Lyster2004, Reference Lyster2010), but previous studies in L2 Swedish (Andersson Reference Andersson1992, Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998) have shown high accuracies, and the actual study with teenaged informants in immersion and non-immersion settings points in the same direction.

The suffix is the most common gender marker in all groups due to the high frequency of definite singulars (Nyqvist Reference Nyqvist2018a, b), which confirms H1. It is also the most accurately used of all simple gender markers, i.e. the result is in harmony with previous research (Andersson Reference Andersson1992; Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998; Ragnhildstveit Reference Ragnhildstveit2017, Reference Ragnhildstveit2018). Accuracies for NPs where gender is marked with a suffix, indefinite article or PR attribute are high in all informant groups, while accuracies for adjectives and definite articles as sole gender markers are lower. Two factors may explain this. First, the suffix is a bound morpheme, whereas other simple gender markers are syntactical constructions. Second, the most accurate gender markers, especially suffixes, show a higher frequency in the input than the less accurate types, which means that learners have encountered them more often. Hence, according to usage-based grammar, learners might acquire definite singulars as unanalysed wholes, which adds to their accuracy. Axelsson (Reference Axelsson1994) has also suggested that Finnish learners of L2 Swedish are especially sensitive to suffixes due to their L1.

All groups reach a higher accuracy in uter than in neuter, which confirms H2. The uter gender is also overused, which is natural from the usage-based point of view, as a majority (approximately 75%; see Bohnacker Reference Bohnacker, Håkansson, Josefsson and Platzack2003) of all nouns in Swedish are uter; this distribution holds true for both oral and written, formal and informal discourse. This result also confirms the previous research (Andersson Reference Andersson1992, Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998).

The results likewise show that NPs with more than one gender marker are significantly less accurate, which confirms H4. Definite NPs with an adjective, i.e. the most typical context for definite articles in Swedish, have been challenging for L2 learners in previous studies due to their high complexity (Axelsson Reference Axelsson1994; Nyqvist Reference Nyqvist2013, Reference Nyqvist2018a, b; see also DeKeyser Reference DeKeyser2005). Thus, it is not surprising that accuracies are also lower when analyses focus on gender. NPs with suffixes are also among the easiest of the more complex NPs, which strengthens the interpretation that the suffixed nouns are acquired as wholes. Overall, however, agreement is more common than non-agreement in all groups, especially with uter nouns, which confirms H5; these complex NPs consequently have inaccurate gender marking more often than gender marking with both uter and neuter elements. Hence, feature-related factors (Housen & Simoens Reference Housen and Simoens2016) such as complexity, frequency and salience, which are also central to usage-based grammar (Goldschneider & DeKeyser Reference Goldschneider and DeKeyser2001, DeKeyser Reference DeKeyser2005, Bybee Reference Bybee, Robinson and Ellis2008, N. Ellis & Wulff Reference Ellis, Wulff, VanPatten and Williams2015) are crucial in the acquisition of gender.

When IM6, IM9 and CG are compared, CG, i.e. the non-immersion group, usually reaches the highest accuracies. This result falsifies H3 and also shows that rich input alone is not sufficient for the acquisition of gender in L2 Swedish. However, a common trait for the three groups is that accuracies for neuter nouns are most often significantly lower than those for uter nouns. Similar results have been reached in previous studies (Andersson Reference Andersson1992, Lahtinen Reference Lahtinen1998). In the actual data, accuracies for neuter nouns are higher in non-immersion, and one explanation might be that, from the beginning, learners in non-immersion are taught that Swedish nouns have two genders. They also see indefinite articles in wordlists and paradigms in their teaching materials, which enhance their ability to notice the phenomenon. In more naturalistic SLA, the learners might never explicitly receive this information – anyway, they do not receive it at the beginning of their acquisition at immersion daycare. In Swedish, uter is substantially more common than neuter, and thus, immersion learners may not realise that the target language has two genders in the early stages of acquisition (see Bohnacker Reference Bohnacker, Håkansson, Josefsson and Platzack2003). The differences between IM6 and IM9 are mostly nonsignificant, i.e. context-related factors appear to be more crucial than learner-related ones (see Housen & Simoens Reference Housen and Simoens2016). However, it is important to note that all these results deal with grammatical accuracy and do not tell anything of the practical communicative competence in the language, which is essential in immersion.

Inaccuracies in gender rarely put comprehensibility in danger, but they label the speaker as an L2 speaker. Hence, in the future, it will be important to study the effect of pedagogical interventions on the acquisition of gender in immersion, as previous research (Harley Reference Harley, Doughty and Williams1998, Lyster Reference Lyster2010) has shown that didactic interventions help learners to focus on gender. As our informants’ inaccuracies concentrate on neuter nouns and complex NPs, it will be important to find ways to enhance the salience – and, thus, the noticing of gender markers – and to study the impact of these kinds of interventions.

For example, a teaching experiment could attend to the low frequency of neuter nouns and certain NP types with study materials, providing input where these NPs occur often, as higher frequency strengthens memory representations (e.g. N. Ellis & Wulff Reference Ellis, Wulff, VanPatten and Williams2015, Audring Reference Audring, Garbo, Olsson and Wälchli2019). Written input is especially profitable for developing implicit knowledge (Kim & Godfroid Reference Kim and Godfroid2019), and the salience of construction can then be enhanced, e.g. by using different fonts. Even Swedish researchers (Prentice et al. Reference Prentice, Loenheim, Lyngfelt, Olofsson, Tingsell, Gustafsson, Holm, Lundin, Rahm and Tronnier2016, Håkansson, Lyngfelt & Brasch Reference Håkansson, Lyngfelt, Brasch, Bianchi, Håkansson, Melander and Pfister2019) have proposed an increased focus on pattern recognition for effective L2 instruction, and it would be interesting to study the effect of this in acquisition. Gender has often been used to show an infamously difficult structure, but if the rich input and meaningful communication typical of immersion are combined with effective explicit instruction, it is likely that the learners will reach a high level of competence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Nyqvist received funding from the Turku Institute of Advanced Studies when writing this article. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, as well as the school teachers and students, and the parents of the students for their collaboration.

Appendix. Statistical data

Table A1. Comparison of accuracies for different types of NPs with simple gender markers.

IM6 = Swedish immersion 6th graders; IM9 = Swedish immersion 9th graders; CG = Finnish-speaking 1st graders

Table A2. Accuracy scores for simple gender markers and comparisons between informant groups.

IM6 = Swedish immersion 6th graders; IM9 = Swedish immersion 9th graders; CG = Finnish-speaking 1st graders

Table A3. Accuracy scores and comparisons between uter and neuter nouns in different groups.

IM6 = Swedish immersion 6th graders; IM9 = Swedish immersion 9th graders; CG = Finnish-speaking 1st graders

Table A4. Comparison of accuracies for different types of NPs with gender agreement.

IM6 = Swedish immersion 6th graders; IM9 = Swedish immersion 9th graders; CG = Finnish-speaking 1st graders

Table A5. Accuracy scores for gender agreement and comparisons between informant groups.

IM6 = Swedish immersion 6th graders; IM9 = Swedish immersion 9th graders; CG = Finnish-speaking 1st graders

Table A6. Accuracy scores and comparisons between NPs with simple gender markers and NPs with gender agreement.

IM6 = Swedish immersion 6th graders; IM9 = Swedish immersion 9th graders; CG = Finnish-speaking 1st graders