Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 July 2005

Congenital arteriovenous fistulas between the thoracic arteries and the systemic veins are rare, and in clinical terms may mimic patency of the arterial duct. We present a neonate with a large arteriovenous fistula between the left sixth intercostal artery and the left brachiocephalic vein, to the best of our knowledge a unique site of drainage. To our knowledge, ours is also the earliest presentation and treatment of a thoracic arteriovenous fistula.

This unique arteriovenous malformation illustrates a potential pitfall when assessing a neonate with congestive heart failure as well as the importance of a full preoperative anatomical diagnosis in congenital heart disease. No single imaging modality provided comprehensive information. Cineangiocardiography, however, elegantly demonstrated the abnormal anatomy and gave the surgeon the necessary information to affect a cure.

An antenatal ultrasound scan at 26 weeks showed a thoracic vascular anomaly, possibly an aneurysm of the arterial duct. A female infant was born at 38 weeks gestation, weighing 3,755 grams. The clinical diagnosis was patency of the arterial duct. A magnetic resonance scan, however, suggested another vascular anomaly.

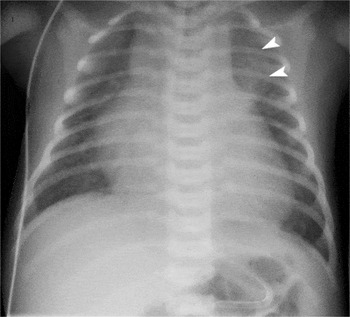

She was transferred to Green Lane Hospital at 7 days of age, after development of high output heart failure. There was a sinus tachycardia of 190 beats per minute. A continuous murmur was heard over the whole praecordium, loudest over the left infraclavicular region. An electrocardiogram showed right axis deviation and right ventricular hypertrophy. A chest radiograph showed cardiomegaly, pulmonary plethora and an unusual left superior mediastinal contour (Fig. 1). An echocardiogram showed a small persistently patent arterial duct, and a large arteriovenous fistula connecting the descending thoracic aorta to the left brachiocephalic vein.

Figure 1. Chest radiograph. There is generalised cardiomegaly and pulmonary plethora. The malformation is seen as the abnormal opacity extending from behind the heart into the left upper zone (arrowheads).

A cineangiocardiogram performed on the following day demonstrated a large left 6th intercostal artery arising from the left posterior aspect of the descending thoracic aorta and connecting to a fistula draining to the left brachiocephalic vein (Fig. 2). This produced a large left-to-right shunt. The left brachiocephalic vein, superior caval vein, right atrium, right ventricle, and intrapericardial pulmonary arteries were all enlarged. The fistula was not considered suitable for embolisation due to its large calibre and single moderate proximal stenosis.

Figure 2. Frames from a left intercostal angiogram, shown (a) in posteroanterior and (b) in left anterior oblique 70 degree projections. The aorta (Ao) is partly opacified. The intercostal artery (I) is proximally dilated, with a 3 millimetre diameter connection (arrowhead) to the fistula. There was a posterior locule (L), and a 20 by 22 millimetre diameter cavity that was 26 millimetre in length. This cavity drained to the left brachiocephalic vein (LBCV) which connected to the superior caval vein (SVC) and the right atrium (RA).

Despite medical therapy she remained in congestive heart failure. Surgery was performed semi-urgently the following day via a left thoracotomy. This confirmed the origin of the malformation from the intercostal artery. The patent arterial duct was ligated, and the malformation excised without complication. Pathological examination confirmed an arteriovenous fistula composed principally of a single large dilated vascular channel with a rather loose fibromuscular wall. The child made a full recovery and remains well at the age of 6 years.

A left praecordial murmur is usually indicative of persistent patency of the arterial duct. Findings were atypical in our patient, with the murmur being maximal in the left infraclavicular region. Any such unusual examination findings should alert the clinician to the possibility of an alternative pathology.

Congenital thoracic arteriovenous fistulas have been described, but are rare.1–6 These anomalies are characterised by abnormal connections between the arterial and venous systems, with a lack of normal capillary development. They have no capacity for involution or cellular proliferation.7 Since the first report made on clinical grounds in 1933,1 as far as we are aware there have been six angiographically proven reports of congenital fistulas arising from the descending thoracic aorta.2–6 All six fistulas drained to the azygous or hemiazygous venous systems. Of these six, four cases clearly involved the intercostal arteries, and five were in females. If the malformation is large, the patient may present early in life with congestive heart failure. Other potential presentations include atypical “endocarditis” and embolic phenomenon.

As far as we know, our report is unique, as it is the only known reported case to drain to the brachiocephalic vein. Our patient is also the youngest diagnosed and surgically treated. We do not know why there is a preference for drainage to the axygos venous system, except possibly due to the close spatial relationship of these vessels.

Chest radiograph. There is generalised cardiomegaly and pulmonary plethora. The malformation is seen as the abnormal opacity extending from behind the heart into the left upper zone (arrowheads).

Frames from a left intercostal angiogram, shown (a) in posteroanterior and (b) in left anterior oblique 70 degree projections. The aorta (Ao) is partly opacified. The intercostal artery (I) is proximally dilated, with a 3 millimetre diameter connection (arrowhead) to the fistula. There was a posterior locule (L), and a 20 by 22 millimetre diameter cavity that was 26 millimetre in length. This cavity drained to the left brachiocephalic vein (LBCV) which connected to the superior caval vein (SVC) and the right atrium (RA).