‘The Army's After Action Review (AAR) is arguably one of the most

successful organisational learning methods yet devised…’

‘…. Yet, most every corporate effort to graft this truly innovative practice in to their culture has failed because, again and again, people reduce the living practice of AARs to a sterile technique.’ Peter Senge

REFLECTIVE LEARNING

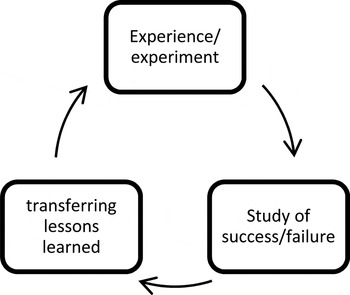

At its simplest level, learning from experiences has three basic components (see figure 1 below):

Figure 1. Learning from experiences: three basic components.

Unfortunately, many organisations get stuck in the planning and acting phase of their learning and spend little time on reflection, either on an individual or organisational level, which risks repeating the problems of the past. Where they see gaps in understanding, many organisations also tend to focus on ‘chalk and talk’ lectures, rather than individual or group study of experiential success or failure,Footnote 1 which is thought to be one of the most effective ways of learning business and professional skills.

WHY CARE ABOUT REFLECTIVE LEARNING?

Training and development promotes competitive advantage in organisations, particularly in knowledge intensive firms, such as law firms. It equips employees to carry out their roles and manage complex situations. It safeguards productivity and insulates organisations against skills shortages. It facilitates agility, the ability of the organisation to adapt to changing business environments, and it serves as an important symbol, sending the message to employees that their organisation values them and wishes to invest in their development, improving their commitment to that organisation.

In KM terms, training and learning not only encourages the sharing of existing knowledge, it also creates new knowledge for both those undertaking the training and those teaching. Those teaching consolidate their knowledge as they explain their existing knowledge to others and they assimilate some of the knowledge of the trainees with their own knowledge as they answer the trainees' questions, which often come from a new and challenging perspective.

WHAT IS AN AAR?

The After Action Review (AAR) is a form of structured debrief created by the US Army in the 1970s to learn the lessons of real and simulated engagements. It is a form of professional discussion of an event, focusing on performance standards. It aims to enable soldiers to discover for themselves what happened, why it happened, and how to sustain strengths and improve on weaknesses to drive continuous improvements.

AAR is low tech, flexible, simple and easy to understand. It provides valuable learning, bespoke to a particular organisation, which, as a side effect, strengthens team cohesion and open communication.

A US Army AAR focuses on four questions:

-

1. ‘What was the intent?’

What was the desired outcome? What was the strategy? How was it supposed to be achieved?

-

2. ‘What actually happened?’

What was the “ground truth”? What were the actual events which played out in the heat of the battle, with the inevitable misunderstandings and confusion?

-

3. ‘Why did it happen?’

How did all the decisions, reactions and events combine to produce this particular outcome?

-

4. ‘What could be improved next time?’

What can be learned from the above three results? How can actions be altered in the future to more closely match what actually happened with what was intended?

During AAR the participants identify their own learning points. This means that the results are more accurate than top-down critiques.

When are AARs appropriate?

AARs take professionals away from their day jobs, so it is tempting to only review the biggest matters/projects which have failed. In fact there is much to learn from what created a success and valuable learning within common smaller matters/projects.

The following library projects could be suitable for AARs:

-

• Multiple matters, representative of those which recur regularly where you have an opportunity to investigate ideas for efficiency gains.

-

• Larger library projects or IT/IM/KM projects, particularly those which have incurred large or unexpectedly small costs or taken a long or unusually short period of time (such as an office/library move, introduction of a new IM/KM IT system or a re-organisation of some sort);

-

• single matters where a large client or client which is representative of a large group of clients (whether internal or external) was particularly happy or unhappy with the outcome.

When and where?

The foremost thing to remember in instituting an AAR project is that it will need to be a living practice focussed on honest conversation, not a sterile box-ticking exercise. Holding a face-to-face meeting (or, if necessary, by video conference if face-to-face is impractical) and candid discussion are key parts of AAR. A significant part of the learning is in each individual's tacit knowledge gained through his/her interactions with others. A ‘lessons learned’ form will not be anywhere near as effective.

The meeting should be held shortly after the end of the project/matter/event or at milestones within a longer project. At this point events are still fresh and learning can be applied straightaway. Between two to four weeks after the end/milestone is ideal. People have then had time to reflect, but events are still fresh.

Review meetings are likely to take no less than 2 hours and more detailed projects may take a day or even two. For your first AAR, err on the side of caution with a longer meeting. If the project does not justify a day away from your desk, you could split the meeting over two or more lunchtimes, although this is less satisfactory than a longer period. The meetings can be held anywhere reasonably private. This could be a meeting room at your firm or a hired room outside your offices. No specialist equipment is needed, so it could even be held in a private room at your local restaurant, coffee shop or pub: anywhere where the discussions will not be overheard.

Who should organise the AAR?

The key players in the project/matter/event will need to be involved in organising the AAR, as only they will know who should be involved, how long the discussions will take and whether there are likely to be an particular difficulties. Apart from their involvement, the organisation of the AAR can be undertaken by someone within the Knowledge and Information team, who understand the nature of AAR.

Who needs to attend?

All AARs will need:

-

1. an independent facilitator who is trained in AAR – this can be an outsider or a properly trained member of your staff; and

-

2. key players involved in the matter/event/project.

Depending on the size of the meeting, you may also need to include:

-

3. administrative help to document or record discussions, to allow the conversation to flow; and

-

4. senior uninvolved personnel to join any discussions concerning firm-wide policies or finance issues.

The Atmosphere of the AAR meeting

The AAR meeting must be dynamic, candid, non-judgmental and professional. In discussing the facts, participants should be encouraged to view the discussion as a frank, respectful dialogue, rather than a debate or lecture and avoid generalisations and unrelated aspects. Participants should be reminded that no single person has all the information or all the answers. There can be tactful and civil disagreement without disrespect. The spirit of the meeting must be one of shared learning and investigation rather than blame, including an individual's own self-criticism.

Law firms can be hierarchical organisations, so a reminder of the army's maxim of ‘leave your rank at the door’ can be useful. The facilitator should also encourage individuals to focus on facts, events and behaviours, rather than personalities and individuals.

The meeting itself

In implementing your AAR system, remember to revisit the basics of AAR as implemented by the US Army. There are four key questions which need to be asked:

-

1. What ought to have happened?

-

2. What actually happened?

-

3. Why did it happen?

-

4. How can you sustain strengths and improve on weaknesses to drive continuous improvements?

An independent facilitator is useful to draw out facts and learning points. He/she should not analyse what is said or offer a critique but to encourage participants to reach their own conclusions.

In US army AARs, discussions are facilitated by an experienced officer who is specially trained to help the participants tease out the ground truth and learning points. All levels of participants attend and they are encouraged to ‘leave rank at the door’. Dialogue is encouraged and participants are encouraged to accept that no one person has all the information or all the answers, and ‘disagreement is not disrespect’. The Army recommends that half the AAR time is spent on the first three questions and half on the last one, demonstrating the value they have found in reflective learning.

What ‘ought’ to have happened?

In order to agree upon what ought to have happened, it can be useful to refer to your firm's standard terms of practice, KPIs, best/good practice documents and what data suggests usually happens in other similar matters, as well as talking to those who regularly work on similar projects.

What actually happened and why?

Finding the ‘ground truth’, i.e. what actually happened, should be easier within a library or law firm, compared to what happened on the battlefield. What may be more difficult is ‘why’.

The facilitator and participants need to tease out why whatever occurred, happened in that way. At this point it may be useful to divide the discussions into key themes amongst smaller groups.

It may also be useful to use analysis tools such as ‘5 Whys' or ‘Ishikawa/fishbone diagrams’ to get to the root cause of events (see Box 1). For example, if a budget was exceeded substantially, it is not sufficient to note that ‘X ought to have done Y’ and tell X to work harder and more accurately in the future. The participants must get to the root cause of why X did not do Y. This could at first glance be related to lack of knowledge, poor processes, lack of time, inaccurate forecasting or many other causes, but an organisation must also look for actionable reasons why the right knowledge/process/time was not available to X.

Box 1.

Root Cause Analysis Tools

5 Whys

‘5 Whys’ is the simplest method of structured root cause analysis. It simply requires an investigator to continue to ask ‘Why?’ until the root cause, not partial cause, of a problem emerges.

-

• Write down the specific problem - describe it completely to help the team focus on the right problem.

-

• Ask ‘Why does this problem happen?’ and write the answer down below the problem.

-

• If the answer you just provided does not identify the root cause of your problem, ask ‘Why?’ again and write that answer down.

-

• Keep looping back to ask ‘Why?’ until the team can think of no more causes and are in agreement that the problem's root cause is identified. You will know when you have reached this point because asking ‘Why’ again will seem redundant. This may take fewer or more times than five Whys.

5 Whys – template

Fishbone/Ishikawa diagram

The Fishbone/Ishikawa diagram is similar to the 5 Whys, but more useful where there are multiple competing causes, or multiple data which needs tracking or trends which need identifying.

In this case, the root causes are still sought, but they are categorised into multiple headings, which are chosen to suit the project or issue.

The following six headings are common: equipment, process, people, materials, management, and environment. Service industries sometimes use the following four: policies, procedures, people, and plant/technology.

Sometimes it is tempting to list “they forgot” or “time pressure” or “they made a mistake” as the root cause, but you are always looking for actionable causes and considering how an improved process or system could avoid this problem in the future. For example, if time pressure is a factor, one can then ask why employees were suffering from time pressure? Are there enough employees? Are there enough support staff? Is IT up to the task? Are there seasonal variations which can be mapped and staffing levels adapted to suit these changes in a cost-effective way? Why did employees prioritise other work above this task? How do rewards and recognition affect the way employees prioritise their work? If an employee made a mistake, what process, system or policy allowed this mistake to occur?

The aim of the Fishbone Diagram is to get lots of ‘causes’ along each bone and look for common themes. For each cause, the team asks ‘Why’ and attaches that cause to the bone too.

What will we do differently next time?

Try to distil answers into concise specific practical consensually agreed statements. It isn't enough to identify what went right or wrong. As part of turning the lesson identified into a lesson learned, you must identify the practical actions which need to be taken in the future. A new workflow may be useful, or a change to KPIs or best/good practice documents or addendum to a database document (say, to a precedent or practice note for legal practice).

Again, it may be useful to divide the discussion into key themes within smaller groups.

Drawing out all participants and viewpoints

All view points of the event are valuable and the facilitator must make sure that a dominant personality doesn't take over the narrative or skew the conclusions. Quiet participants are often thoughtful and have valuable insights to offer and must be encouraged to participate in a non-threatening way.

Sometimes the facilitator will find he/she is struggling with too few useful contributions. In this situation they can try asking the following:

-

• What are the top 5 lessons you personally have learned from this experience?

-

• What are the top 5 best practices of other people which you have witnessed during this project?

-

• If you were to give this project a score out of 10 (where 10 is perfect and 1 is a total disaster), what would that score be and what would have made the score a little higher?

The meeting aims to discover actionable reasons for outcomes, so the facilitator must encourage the group to delve deeply into each participant's answers. Again, the root cause analysis tools are a great way to encourage meaningful discussion.

The facilitator must also ensure that the improvements which are suggested are real learning points, not one person's opinion. Suggestions for changes to a process or document need to be considered and validated by those who have the most expertise or experience in that area (and remember that this person could be a junior member of staff – you are looking for someone who undertakes the work/uses that document/process regularly). If there is no one like this at the AAR (and there really ought to be) this step will need to take place after the AAR meeting itself is over.

Some individual learning is tacitlyFootnote 2 absorbed by those involved in the AAR straightaway, but it also needs to be recorded in some way to pass lessons on to the rest of the organisation and draw out common themes across a number of AAR. It is therefore important to have a note-taker available throughout the session. Some people find a neutral note-taker is helpful: someone who perhaps has a different perspective. Others find someone with experience of the project is a better note-taker because they can better understand the narrative and jargon and so not interrupt the flow with questions. Some people find it helpful to write out the questions for discussion on flipchart sheets before the session, so the discussions can flow more freely and people are kept to the point of the session and time isn't wasted. You will know which tactic will suit your review.

Although each individual will learn their own lessons, adding the knowledge they gain through the discussions to their existing knowledge, the lessons will need to be analysed so they can be explained to those outside the meeting and so that processes and knowledge artefacts (KPIs, precedents, standard practices or contract, documents in databases etc) can be changed. In trying to pin down the lesson, it can help to imagine you are trying to teach the change to another person.

Videos of discussions would capture rich, non-verbally expressed knowledge, but this must always be balanced against the need for participants to feel comfortable in being completely candid.

In general, there is a balance to be found between confidentiality of the discussions, to encourage openness, as against the need to share the lessons learned with the rest of the firm. Where that balance lies will depend on the culture of your firm. It may be that a neutral uninvolved third party can take the responsibility of distilling the lessons into a suitable format for sharing, which may change over time, as employees get used to AARs. For AARs concerning legal practice, a PSL is ideal. For IM and KM projects, a suitably trained member of IM/KM staff will work.

Whatever method is used to record the lesson, disseminating the lessons learned is crucial. A lesson documented is not a lesson learned and candid participation will wane if lessons are not seen to be learned.

What should happen after the meeting?

As suggested above, one area where many organisations get stuck with this method of learning, is in its failure to step beyond identifying the lesson and moving to embed the necessary changes. If we refer back to our diagram of learning through experience, we can see that the AAR meeting itself addresses the second aspect of the cycle, but there is much to be done after the meeting to ensure that the lessons which have been identified are transferred through the wider organisation and any changes necessary are embedded.

Figure 2. Learning from experiences: transferring lessons learned.

Changes which need to be made must be allocated to particular individuals for action. A PSL may be an appropriate person to undertake this for technical legal matters, or a fee earner.

Those individuals will need to be accountable for appropriate follow-on action. Firstly, they will need to validate the proposed lessons. Not every lesson will be applicable outside that project. Some will be contradictory and some will have been tried before and didn't work.

For those lessons which do need a follow-up, some will require processes to be updated and some will necessitate changes to artefacts of knowledge, such as KPIs, standard terms of contract, precedents, practice notes, knowledge databases etc.

Lastly, anyone needing to access the new improved process or precedent etc must have easy access to it. It is important that anyone seeking knowledge only needs to look in one place for it and not have to check a separate database of lessons learned in addition to their usual knowledge/precedents/notesdatabase. You may want (depending on the nature of the change) to broadcast it through internal channels such as blogs and newsletters or talk relevant people through the changes in a training event. It can be helpful to tell the story of how the lesson came to be learned (details can be anonymised) and why the knowledge is important. You will need to draw on all your usual knowledge about successful change management to ensure that the lesson is transferred across the organisation.

Lastly, a plea to remember to break silos in sharing your lessons learned. You may learn particularly technical knowledge which is only relevant to your team/department or you may learn something which could be of use to everyone. Project management and client care lessons are often relevant to everyone and court and civil process lessons can relevant across different litigation departments.

WHAT BARRIERS TO SUCCESSFUL AAR WILL YOU FACE?

Given the simple nature of AARs and the opportunity to improve outcomes, one would expect AARs to be successfully implemented in a number of organisations. Yet, as Peter Senge says, many corporate efforts have failed.Footnote 3

There are a number of reasons for this. Even where organisations aren't tempted to reduce AAR to a form-filling, box ticking exercise, often they still get stuck at documenting lessons. A lesson documented is not a lesson learned. The identification and documentation of the lesson is a stage towards learning the lesson. The lesson needs to be analysed and disseminated, and then the changes to practice need to be embedded.

Some organisations, particularly the risk averse, also tend to focus on avoiding failures or stray into blame, rather than looking at the wider learning available from partial and whole successes.

Strong leadership by example is necessary to overcome the natural preference for individuals not to have their behaviours come under scrutiny, for fear of negative comments. There is the potential for AAR to make a considerable difference to law firms' practice and learning loops, but a firm will need to find ways to overcome a natural reluctance to examine practices and embed new practices in a useful way.

For a successful AAR programme you will need the support of senior staff. Whilst this may not be a problem with involving senior IT/KM/IM staff, it can cause problems in AARs concerning legal practice. If senior fee earners do not show commitment to the project, then more junior members of staff will question why their time should be taken up in this way. Once everyone starts to see personal benefits from their own lessons learned they will become more enthusiastic about the programme, but even then, if senior support is weak, this will become a barrier to participation, as staff prioritise alternatives over the AAR.

Similarly, if people find themselves subject to attack or blame during these meetings, they will stop contributing openly and fully. Leadership can make a massive difference here, so it may be worthwhile investing in some suitable training for leaders, so that they are fully cognisant of all the benefits of AARs and so support them.Footnote 4

SUMMARY

AARs are one of the most underutilised methods of learning and as such offer a significant opportunity for competitive edge if implemented well in your organisation compared to your competitors. Hopefully, this article will have given you the tools to become ‘AAR Champions’ in your organisation and transform its practice for future success.