In 1673–74, Yacine Bubu, lingeer of Kajoor, helped the Muslim cadi, Njie Sall overthrow her nephew’s government and kill him. She then insisted that another nephew be named ruler of Kajoor. Once Njie Sall’s disciples killed her next nephew, she sent word to yet another nephew to come and defeat Njie Sall and his forces to retake the throne of Kajoor.

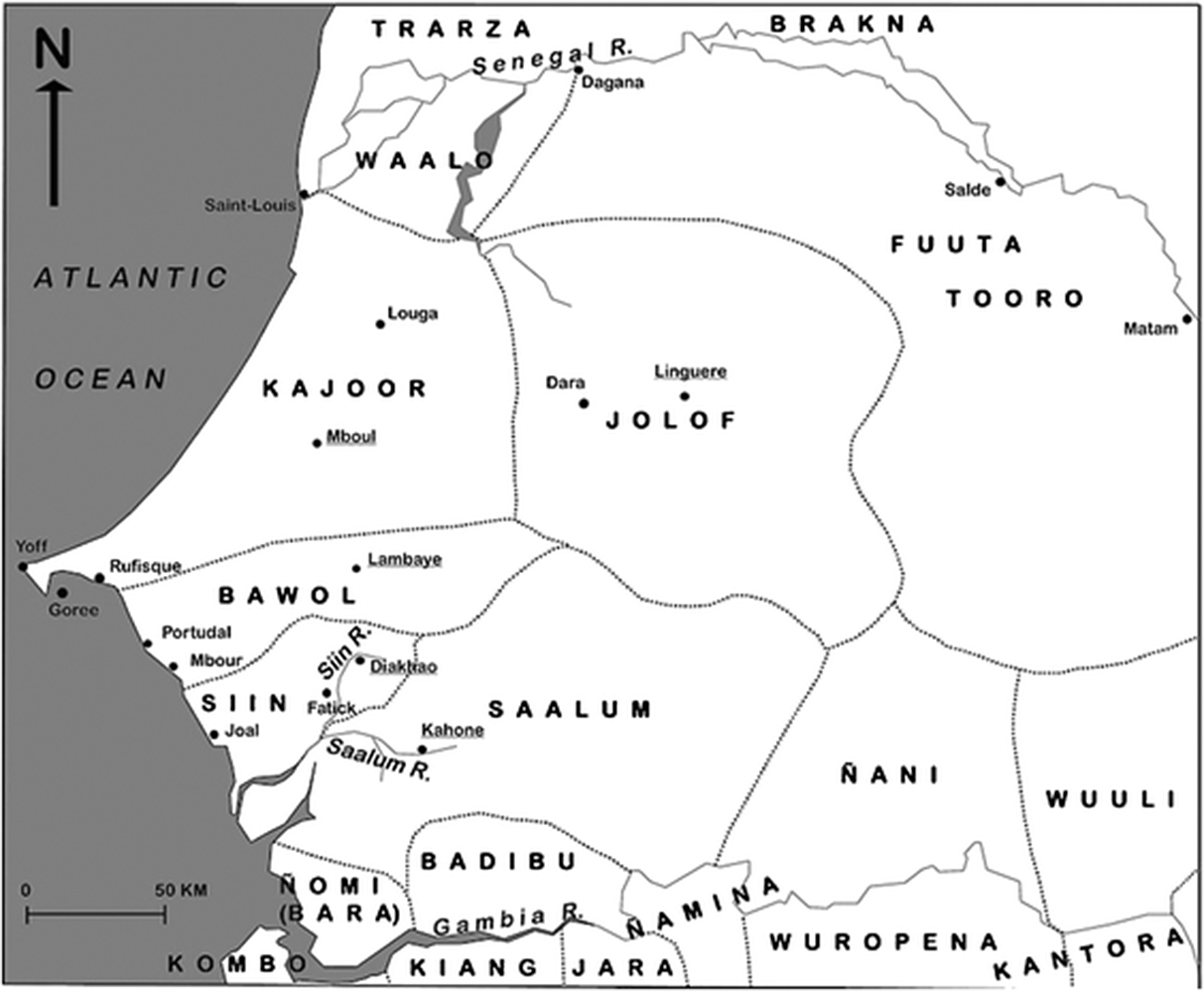

Map 1. The Senegambia region in the 17th century.

This article seeks to right a wrong, an ontological violence, that often accompanies the writing of histories beyond Europe. The telling and retelling of this episode in history has excluded the name of one of the major actors, Yacine Bubu, lingeer of Kajoor, during the Shar Bubba Jihad of 1673–74. In this article I argue that the misunderstanding of the position of the lingeer and the reliance on the writings of outsiders (French and Arab observers) produced a male-normative interpretation of the Sharr Bubba Jihad as it unfolded in Kajoor. Male-normative discourses devalue women, thereby creating a sphere of understanding where portraits of power and authority are devoid of women, and reality is one in which women are, at best, parenthetical. More pointedly, this dismissal of Yacine Bubu amounts to ontological violence because it results not only in the exclusion of one person but the excision of the institution of lingeer because it does not fit into the vice-grip of European epistemology.

I attempt to correct this first through an exposition of how the prevailing academic history is complicit in the continual colonization of African history through an obsession with written sources at the expense of oral, archeological, and historical linguistical sources, among others, which leads to a foreshortening of African history and a denial of African historical realities. Secondly, I explain how Eurocentric discourses relegate African women to ancillary bearers of children, hewers of wood, and drawers of water in opposition to the nuanced descriptions of historical sources and the experiences of Africans themselves. I further explain that the relationships between gender and authority in African histories do not align with the European “template” explaining the position and role of lingeer. Thirdly, I give the details of the Sharr Bubba Jihad in Kajoor through a rereading of the sources, saying her name, and contextualizing the role of the lingeer in Kajoor and the other Senegambian kingdoms.

Background on Sources

The catalyst for this jihad in Kajoor was a brazen transgression of Kajoor’s constitution.Footnote 1 Most secondary sources on this episode argue that the jihad had its roots in present-day Mauritania and was all about Nasr al-Din’s ambition. Religion was secondary, though not a minor part of it all. As Lucie Colvin correctly states, the people of Kajoor were already Muslims. The jihad’s purpose was to reform the practice of Islam. These points are clear thanks to over five decades of historical study of precolonial Senegal. There are considerable secondary sources on seventeenth-century Kajoor. The pioneering work by Senegalese, French, and a few American and Canadian historians is built upon the existing oral record and the biased, yet informative writings of Arab, Portuguese, and French chronicles of this period. Yet even in these celebrated secondary works, the lingeer’s role is largely dismissed or diminished.

Following the French visitors’ version of the events, Boubacar Barry and Philip Curtin attached this episode of jihad to the broader regional jihad of Shar Bubba using, among others, the report of the seventeenth-century French commercial agent Louis Moreau de Chambonneau.Footnote 2 Using both oral accounts and written accounts, Lucie Colvin analyzed the episode along with two other jihads in order to point out why they were unsuccessful.Footnote 3

For precise details on this jihad, the oral record has proven invaluable. Though oral sources are more widely accepted since the 1960s, some American and European historians continued to cast aspersions on oral sources as late as the end of the twentieth-century, saying that the oral sources are unreliable for various reasons, chief among them that they are simple inventions.Footnote 4 On the face of it, much of this criticism is, to me, laughable, more of which will be discussed below. In his explanation for the use of oral resources, Assan Sarr cites Toby Green’s suggestion that we see oral sources as an archetype instead of a stereotype.Footnote 5 Sarr goes on to state how issues around land use, ownership, and control are available in the oral record in ways they are not in the archival record. In much the same way, the interior movements, context, and personalities of Kajoor during the Sharr Bubba jihad are mostly absent in the written sources. Without the oral record, there would essentially be no sources for this article.

Collected from the geuwel (oral historians/griot) at the end of the nineteenth century, I am using two written collections of the oral tradition, as mentioned above. The earliest one is that of Yoro Dyao, who was a translator and canton chief for the French Colonial Service.Footnote 6 Dyao was a notable from Waalo before entering the French Colonial service. Tanor Latsukaabe Fall produced the second collection, which is the product of research and work from various sources, including Dyao’s collection and other geuwel. Footnote 7 Fall was from the royal family of Kajoor and was named for the eighteenth-century ruler of Kajoor and Bawol, Damel-Tegne Latsukaabe Fall. Both oral sources have small variations, but give essentially the same information, with Fall’s work giving more details. Dyao and Fall’s perspectives include a reverence for the system and the power which it afforded women.

In the oral record, Lingeer Yacine Bubu’s jihad seems like a rather brief episode. It takes approximately three pages in both oral histories consulted. Both Dyao and Fall place this jihad beginning in 1683. The reports of French observers, however, present it differently. The French accounts put it at 1673. I am going with the dating of the French sources at 1673. Regarding the details of the event, I focus on the oral record because it names Lingeer Yacine Bubu and gives details of her major role in the jihad.

Re-Presenting African Historical Narratives

Knowledge production in the West is rooted in Western European traditions and often operates within the limitations of those traditions. Two of these limitations that have negatively impacted the presentation of the African past are the centering of Western European history/experience as the standard/norm and the insistence on the use of written historical sources. The trend toward establishing the European history/experience as a standard lends itself to assigning a value to the past and cultures of non-European societies. This problematizes all academic discourse involving non-European peoples and corrupts the formulation of social theories and critiques.Footnote 8 More particularly, it assigns all non-European women the same place in their histories that European women have in their histories.

In her article “Under Western Eyes, Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses,” Chandra Talpade Mohanty bravely confronts Western feminist theorists’ tendency to essentialize and standardize their experiences as universal in their attempts to analyze the issues of so-called Third World women. Discussing the Western trend towards universalization of their experiences in feminist discourse, Mohanty writes, “It is possible to trace a coherence of effects resulting from the implicit assumption of ‘the west’ (in all its complexities and contradictions) as the primary referent in theory and praxis.” Expanding on the tendency to assign a value to non-European cultures/peoples, she continues, “Rather than claim simplistically that ‘western feminism’ is a monolith, I would like to draw attention to the remarkably similar effects of various analytical categories and even strategies which codify their relationship to the Other in implicitly hierarchical terms.”Footnote 9

Writing particularly about Africa, Nkiru Nzegwu calls out the debilitating tendency in academia to devalue and even deny the experiences of African women prior to European conquest and colonization. She boldly writes, “Nowadays, the teleological ethos and ethics that fostered their (Igbo women) agency are deemed ahistorical and represented as falsehoods by a Western intellectual scheme that cosmologically reconstitutes all cultures as deficient and degenerate.”Footnote 10 She goes on to assert that, in this epistemic vice-grip, progress is only imagined as mimicry of the West, as revealed and led by a supposedly superior Western agency. From this standpoint, so-called international agencies establish a narrative of development with the goal of creating African and Asian replicas of Western European states, economies, and societies through the delegitimization of indigenous non-European societies/states, cultures, and past.Footnote 11 These and other writers lament the intellectual and cultural bridle of academia that produces, whether knowingly or not, exclusionary discourses inhibiting any level of objectivity, having chosen to embrace the familiar yet confining “standard” understanding of life through the prism of a colonized and colonizing reality.Footnote 12

The second limitation of Western traditions is Western historians’ obsession with written sources. Western scholars, such as Finn Fuglestad, disparage oral sources – writing that they are “official propaganda” and “not history,” which can be said of every school history textbook.Footnote 13 Donald Wright writes about how oral history was useless to him in his quest for discovering the history of Niumi/Barra, a former kingdom on the coast of the Gambian River. As one reads further in his article, it becomes clear – by his own admission – that he expected too much from his oral sources. Mentioning that some of his informants were literate seems to imply that he also expected some sort of imaginary “noble savage” authenticity from his informants.Footnote 14 This is emblematic of the issues surrounding the use of oral sources and of the larger issue with the writing of African history. If a scholar brings a Eurocentric understanding of history to the study of non-European people, he/she can only operate in dysfunction. Europe and/or the West is not a template for the world and, as such, cannot be analyzed in the same manner as non-European entities. The academic historian must recognize that African societies/cultures are in constant negotiation with European cultures/languages/political arrangements because there is a clash that many Westerners often try to ignore.Footnote 15 This clash plays itself out in the evolving epistemologies and, although it may never be fully reconciled, it must be recognized as central to any honest intellectual/academic analysis.

Once we position the clash centrally, understanding the trends in the study and writing of African history makes sense. Africanists who focus on the so-called precolonial era often bemoan the foreshortening of the study of “precolonial” African history because of the focus on modern history.Footnote 16 Richard Reid posits that two (of the many) reasons for this is (1) hyper-valuation of the colonial encounter and (2) the insistence on written sources. Insisting on only or primarily written records even in the study of so-called modern history delegitimizes the African reality of thousands of societies without written languages. Furthermore, it delimits the African past – before conquest and colonization – to what Reid calls “mere prologue.”Footnote 17 In other words, “history” only begins when the Arabs or Europeans show up with their writings, which holds the field of history back in the foolishness of Hugh Trevor-Roper’s proclamation.Footnote 18 Beyond the mundane concerns of reliability for the sake of an imagined objectivity on which Trevor-Roper and others insist, Jean Boulègue, Derek Peterson, and Giacoma Macola have demonstrated how important perspective is in creating historical knowledge.Footnote 19

Oral sources and the written documents that they feed help complete a view of the past by nourishing the narrative with African indigenous perspectives that would otherwise be conspicuously absent from academic history. Today, we have a significant and growing archeological record at our disposal in addition to the oral record, much of which has been recorded on paper in various versions. In the focus of our present study, previous historians ignored the oral record, which resulted in their dependence on the views of Arab and European men who wrote from an outsider’s perspective. As such, they mention Yacine Bubu’s intervention. Yet their positions as men eclipsed a woman’s perspective, resulting in little information on each lingeer. Though Dyao, Fall, and others who wrote oral histories received their information from griots and griottes as well as family members, most of those who wrote their histories in European languages were men. So even the oral passed mostly from the mouths and through the pens of men.Footnote 20

Thanks to the pioneering work of Jan VansinaFootnote 21 and others, Western historians have been coming around to the reality that studying the history of oral societies requires that we not only take oral sources seriously, but that we also see them as the foundational and essential sources for African histories.Footnote 22 There is still considerable push-back to the reliance on oral sources as well as disputes as to how much we should rely on them. Opposition to oral sources as sources in African history emanates from a perspective with intellectually limiting, high ideological walls that are foundational to the construction of what Fugelstad calls “Europeanized African history.”Footnote 23

Introducing oral sources in academia as integral to the study of the African past seizes the cultural and intellectual power to create knowledge from a Eurocentric epistemology rooted in written documents and places it within the reach of the host cultures while exposing the myth of the historian’s objectivity. Adding archeology and linguistics to the list of potential sources insists on an expansion of the definition of history, thereby creating a new context for the presentation of the African past. Within this new context, the griot becomes a public intellectual; magic/sorcery becomes real and possible; time is no longer linear; the so-called precolonial African history becomes simply African history (hopefully with its own pertinent periodization); colonial/postcolonial history becomes a brief recent historical episode; conquest/colonization becomes rape, pillaging, and looting; and the “modern” African state becomes an inappropriate and illegitimate creation of a self-obsessed Europe.

Gender, Power, and Authority in Africa

Women have been conspicuously absent from academic study of the African past. As mentioned above, the attempts to standardize European history as a template for human experience, coupled with the fixation on written resources, go a long way in explaining the marginalization of women in African history. A third explanation for the continued absence of women in much of African history is the Western scholars’ large-scale miseducation on the roles of women in African societies. The prevailing narrative that African women were powerless bearers of children and tireless workers emanates from Western scholars impressing realities of European history into African histories.Footnote 24

The Western paradigm of authority is well understood in the Western academy. Traditionally, this Western paradigm of authority influenced the ways historians understood and wrote (or did not write) about women in African history. The results are male-normative, patriarchal statements of authority in the African kingdoms, which are not representative of the reality as presented in the oral literatures. Over the past four decades, beginning with the work of Kamene OkonjoFootnote 25 on the dual-gender authority system and continuing with the work of Oyeronke Oyewumi, Nwando Achebe, Flora Kaplan, Beverly Stoeltje, Imke Weichert, Nkiru Nzegwu, and a host of other scholars, the dual-gender authority system as the norm for centuries in Africa has been presented to the Western academy.Footnote 26 However, there is more work to be done in order to inform those on the frontlines of feminism and gender politics. With the new information on precolonial African women, the narrative of the perpetually poor and powerless African woman can be eradicated as a part of African history, and African women’s current situation can be seen as a consequence of imported European male-chauvinism and the vagaries of toxic capitalism.Footnote 27

In her work A History of African Motherhood, Rhiannon Stephens writes about the ideology of motherhood. In explaining this ideology of motherhood, Stephens takes us beyond the biological comprehension of motherhood and into the social and cultural realities that form the basis of authority structures in so-called precolonial African societies. To be a mother was more than just bearing children.Footnote 28 Sometimes it did not (or does not) even include bearing children. This is based on the idea of “public motherhood,” a term coined by Chikwenye OgunyemiFootnote 29 and used in Lorelle Semley’s work, Mother is Gold, Father is Glass. Semley’s use of the term is all inclusive of the biological mothers, queen mothers, and spiritual women leaders. In this understanding of motherhood, women understood their production and management of agricultural and human resources as positions of power. Men, comprehending the inherent importance of women to the establishment and maintenance of society, negotiated with the women in the evolution of these positions of power and authority.Footnote 30

To reiterate highlighting the economic importance, the power of these women resided in their production of human resources (children), nourishing and early education of said human resources, food production, home building, and home maintenance. This power translated into authority as societies gave way to monarchies. Many African monarchs formed an authority structure that practically negotiated the organic tension between male power and female power realized in a dual-gender authority system, operating through the principle of complementarity.

Though Africa is the world’s second largest continent and diverse, gender complementarity is evident in many of her “precolonial” cultures and societies. As we will see below, what I call an African Gender Ethos, rooted in the principle of gender complementarity, emerges from the literature in which men and women are biologically complementary in that they come together to create life, thereby continuing the existence of humanity. This ethos is the ideological/philosophical foundation for African dual-gender authority systems. In the African Gender Ethos, women are the source of life and, as such, the conquerors of death. Comparably, in many African cosmologies, earth, the source of plant life, is often seen as a goddess. Secondly, the African Gender Ethos presents women’s mediation and calming influences in opposition to men’s roughness/violence. Lastly, the African Gender Ethos highlights the power of post-menopausal women’s lived experiences as exhibited in spiritual superiority, knowledge of medicinal plants, and pliability to navigate complicated socio-political situations.Footnote 31

Writing about the women presentation in the Mande epics, David Conrad explains that one of the names of Sunjata, Son-Jara, is representative of an “essential truth of the Mande intellectual system … that human existence and survival depend on the strength of women.” He goes on to cite Sarah Brett-Smith’s assertion that women’s power to give birth is seen as powerfully defeating death. This ability to produce life is “the ultimate in human power.”Footnote 32 He goes on to further discuss women as the source for the epic Mande heroes:

If, in the kuma koro or ancient speech, men are the instruments of conquest and destruction, those who can kill but not bring forth new life, women are the sabuw (sources, providers) of all that these men accomplish. Traditional narrative presents the men as instruments (sometimes lethal) that may go astray at any time, requiring guidance by mothers and sisters who provide them with their martial power and lead them to their destined paths.Footnote 33

This focus on women as the source of all provides context for the fear of women that undergirds Mande insistence on male domination as well as the inclusion of women authority in their political systems.

In the Ashanti Empire, gendered authority is complementary and is replicated at the village, provincial, and imperial levels, with each male ruler (ohene) having a female co-ruler (ohema). This gendered authority is rooted in the abusua (matriclan), which has a male leader (abusua panin) paired with a female leader (obaa panin). Previously, the ohema has been translated as queen-mother. This is grossly inadequate and misleading. Queen-mother is an English term referring to the mother of the sitting monarch. More about the term is discussed below. I use the term female-ruler to explain ohema and other political positions for women in the African dual-gender political systems. The ohema is expected to give wise counsel to the ohene and provide a necessary counter-balance to his masculine weaknesses as he protects her and all of society from feminine physical weaknesses.Footnote 34

Much like women in Mande philosophy, Asante women’s ability to bear children is seen as a uniquely important power. Women are the only ones who can give blood to the children. If there are no women to give birth to the children, the matriclan dies, and by extension the tribe/nation is decreased and moved a step further to extinction. As mothers, post-menopausal women are expected to give their children guidance and counsel. Thus, the ohema’s role is ceremonial, spiritual, and actual in counsel. She is charged with spiritual cleansing of the wayward and the organization and upkeep of the ohene’s wives and children.

In reference to the women in the former kingdoms/governments of the Senegambia, Fatou Camara explains it as follows:

Life, fertility, and prosperity are born of an alliance between the masculine and the feminine. Instead of being opposed to one another, the two genders are partnered with the goal of realizing harmony and success. As in the image of the earth and the sky, the sun and the moon, dryness and wetness, the man and the woman, the sexual pairs are the motors of life and the source of equilibrium on earth as in the cosmos. Using this concept, a woman can be the sole head of state (as in the image of the primordial mother, progenitor of the world who gave birth to the first couple). However, a lone man embodying sterility must partner with a woman in order to have a prosperous reign.Footnote 35

In the dual-gender system, men have leadership positions that encompass specific roles. Women in turn have leadership roles that cover roles outside the control of men. Together these roles make a whole and, as such, hold society together. There is always tension between the two leadership roles, but the tension is part of what makes it work. The dual-gender system also allowed the exposition of leadership skills to be utilized and honed, expression of women’s concerns (and, by extension, that of their children), and the effective completion of adequate authority for all of society through a complimentary authority structure.

The women in these roles are usually older because age is treasured in African societies and cultures. Semley discusses how there is a reverence and fear for the post-menopausal women who are public mothers not only because of their perceived mystical powers but also because of their longevity, which lends credence to a belief that they have somehow mastered life. This mastery of life often elicits fear and awe as some elderly women are depicted positively and others negatively – as “witches” – because of their potentially dangerous spiritual powers. Semley goes on to state, “Public Mothers do not simply nurture the broader society but also embody the complexities of power, its contradictions, and its limits.”Footnote 36

In many traditional African contexts, women elders are often referred to as mothers whether or not they have ever borne children. Because of a linear conceptualization of time and human relationships, Western cultural norms do not recognize the perpetual childhood of the individual in relation to older people in the community. Traditionally, African societies tend toward a circular conceptualization of time and space, emphasizing a perpetual overlapping of the spirit and physical world, creating human relationships in which one’s ancestors are always parental, always near, and always in contact.Footnote 37

The traditional African worldviews also arrange people in relation to age. The oldest people look up to the ancestors. The adults look up to the elders. The young adults look up to older adults, and children look up to them all. Looking up to elders is not a passing admiration for their longevity and experience. Looking up to the elders is a lifestyle in which the longevity elicits systematic respect and recognition, requests to drink from the elders’ wells of wisdom and experience, and the guidance of the community. If younger people disrespect the elders, they disrupt the spiritual and societal alignment and thereby invite chaos and punishment. Unfortunately, people have manipulated this gerontocratic sociopolitical arrangement to retain power and exclude younger and more talented people. Since young Africans drink from other fountains of knowledge beyond that of the elders, elders sometimes see this “new” knowledge as a threat to their power. However, as history has shown us with the introduction of Islam, Christianity, and other foreign cultural agents, Africans have deftly managed to introduce change while maintaining the continuity of their social orders. Traditionally, there were no nursing homes in these societies, but economic realities have made them a necessity as more African women work outside the home. Even now, home health aides are preferable to nursing homes as these “homes” can result in the marginalization of the aged. Most aged Africans requiring long-term care still live and receive that care from family members. Being an elder in traditional African cultural contexts usually involves less neglect and more respect than in comparable Euro-American cultural contexts. Now our discussion turns to how the African Gender Ethos negotiates with Islam in seventeenth-century Kajoor.Footnote 38

Kajoor, Islam, and the Coming of Jihad

Located in the extreme west of central present-day Senegal, prior to 1549, Kajoor was a province in the Jolof Empire (see Map 1). Northern Kajoor has very fertile soil known in Wolof as joor; from this the region took its name, Kajoor. Kajoor included the coastline from the mouth of the Senegal River to the peninsula called Le Cap-Vert. More pointedly, it was the Jolof Empire’s outlet to the coast and the lucrative trade with Europeans.

Waalo was to the north, Bawol was to the south, and Jolof was to the east. All of these kingdoms, along with Siine and Saluum, were previously an Empire under the rule of the buurba Jolof. Jean Boulègue questions the validity of the Empire of Jolof, citing military conflicts between Jolof and the various provinces recorded by French and Portuguese observers. Using archeological resources in addition to oral and written sources, Francois Richard offers an expanded view of central governmental authority beyond the neat definitions that exist in the Western paradigm. In my work on the Layennes, I make a similar argument while discussing the Lebou government, remarking that it defies the confines of Western labels. In short, the Wolof, Seereer, and Lebou understanding of power/empire contained contests for power in the constituent parts.Footnote 39 With this in mind, the oral record relates that the Jolof Empire consisted of Bawol, Kajoor, Jolof, Waalo, Siine, and Saluum, which again were all provinces of the wider Jolof Empire. In instances of disagreement between the oral and written sources about domestic issues, I accept the oral record. The Europeans observers were strangers who did not know or understand the people. Their accounts must be read in the context of their unfamiliarity with the place and the people. Their recording of wars between parts of the Jolof Empire does not mean the empire did not exist or that it existed tenuously: it just did not exist within the confines of the European understanding.

The Jolof Empire was once a part of the empire of Mali, which had been a part of the empire of Ghana. As such the Jolof Empire was a part of the trans-Saharan trade that had been the primary source of exported and imported goods for sub-Saharan Africa for over a millennia. The shift of significant parts of this trade to the Atlantic coast reshuffled economic and political power. Prior to this shift, the trans-Saharan trade introduced Islam to the region in the eighth century. Islam spread to become the primary religious identity of the area. Historians have no record of pre-Islamic religion for the Wolof people. Clearly, there are elements of a pre-Islamic religion evident today, as in the seventeenth century, but no traces of an organized religion other than Islam. When Mali disintegrated in the fifteenth century, Jolof became independent of any political overlords. During the previous centuries, Islam flowed down from the trans-Saharan trade routes into the heart of the Jolof Empire and beyond.

Around 1549, Kajoor proclaimed her independence along with Bawol. From that time forward, the Empire disintegrated further until Jolof was just another kingdom among equals. Though Jolof tried a few times to reconquer the province, it never succeeded and became a poor, isolated kingdom. The increasing trade with Europeans on the Atlantic coast of Kajoor was a primary factor in the disintegration of the Jolof Empire. Ajoor aristocracy grew wealthy from this trade. This wealth enabled Kajoor and the other provinces who had access to trading networks the desire and ability to break away from Jolof.

Kajoor, like the surrounding kingdoms, had a society with a strict hierarchy. At the bottom were domestic slaves known as jaam. Above them were the endogamous occupational groups known collectively as the ñeeño. The ñeeño were divided into three main categories: jef lekk (those who eat from their work); sab lekk (those who eat from their words i.e., geuwel, also known as griot); and ñoole who served food, entertained, and were courtesans of the nobility.Footnote 40

Above the ñeeño were the géér who were socially the top of the ladder because of their supposedly pure Wolof blood. Politically, there was another breakdown between the gor, or free people, and the jaam. The gor were further divided between the garmi or those active in political power and the badoolo, which means literally “without power.” The garmi were the royal matrilineages. In order for a man to be dameel, he had to be from the Fall patrilineage and one of the royal matrilineages. The royal matrilineages were the Seno, Wagadu, Gelwar, Bey, and Geej. During the period that we are discussing, the Geej was not one of the matrilineages. Latsukaabe added the Geej family to the royal matrilineages in order to justify naming his mother lingeer in the 1690s. The jambur was a group of notables chosen from the laman families who were the original owners of the land.

In addition to the divisions among the free people, there was another division among the slaves too. The jaami buur were slaves of the royal family. The jaami badoolo were slaves of the commoners. The jaami buur sometimes exercised more power than free people as they formed the core of the dameel’s bodyguard and later, under Dameel-Tegne Latsukaabe, became the standing army of the state. Though technically beneath all the gor on the social scale, the jaami buur played direct roles in the politics of Kajoor because of their access to power.Footnote 41

Amidst all these social and political distinctions, the matrilineages – known as meen – and the patrilineages had strong roles in the state. One’s matrilineage and patrilineage both determined an individual’s social status and hence his/her political status. One of the primary designations for an individual to be gor was that neither he/she nor any of his/her predecessors were ever in involuntary (jaam) servitude or in one of the occupational endogamous groups (ñeeño). The permanence of family status further indicates the importance of the entirety of a family’s matrilineage and patrilineage in the composition of the individual. These two halves of an individual also structured social relationships with family members.

In Kajoor, royal authority is exercised by the dameel (king) and the lingeer (female ruler). This is not unique to Kajoor. Both the Seereer kingdoms of Siine and Saluum and the Wolof kingdoms of Waalo, Jolof, and Bawol also have lingeer. Though there were variations in nature and disposition of power, all these kingdoms had the lingeer as the female ruler of the kingdom.

In Kajoor, the chosen (elected) king chose his lingeer, but she had to be the oldest woman of his matrilineage. Thus, it was either his mother, his maternal aunt, or his sister who was named lingeer. There is no word for cousin in Wolof. Cousins are referred to as sisters/brothers, and an individual would know his or her mother’s or father’s cousins as aunts and uncles. Thus, in the Western arrangement of familial relations, the lingeer could also be a cousin of the sitting male ruler.

As noted above, this dual-gender authority setup is not unique to the peoples of the Senegambia area. It is found throughout Africa and other parts of the world. It emanates from the philosophy that life is composed of both male and female, which comprises the African Gender Ethos discussed above. This idea is further evident in the family relations of the peoples of the Senegambia region. For example, one’s aunt and uncles are known as either being from the paternal line or the maternal line. The paternal aunt is known as the bajaan, a contraction of baye jigeen, which literally translates as female father. The maternal uncle is known as nijaay, which is said to be a deformation of ni yaay, meaning like a mother.Footnote 42 Tanor Latsukaabe Fall writes that among the Wolof, an individual feels closer to his matriclan and shares hopes and personal desires with the members of his matrilineage as opposed to those of his patrilineage.Footnote 43

These Wolof/Seereer understandings of gender and family relations, particularly relating to power, were not a part of Islamic ideas about power and its usage. As a result, Muslims had to negotiate practically which Wolof cultural traits to keep, adapt, and/or discard. In the seventeenth century, this often meant that Islamic villages stood outside of the strict confines of the traditional social and political structures. Islamic local leaders were known as seriñ. By the seventeenth century, all the Wolof were Muslims, however the seriñ were Islamic scholars who had their own clients known as talibés, students in Arabic. Increasingly, reform-minded seriñ sought to garner more political autonomy and/or state power. Ultimately, they were all defeated and/or co-opted into the state apparatus in Kajoor.Footnote 44

Lucie Colvin spent a great deal of her article on jihad in Kajoor demonstrating that the Wolof were thoroughly Islamized prior to the jihads. Her argument is based on particular facts. Islam came to the region centuries prior to the first jihad. Most people identified as Muslims. European observers, starting with the Portuguese in the mid-fifteenth century, reported that the Wolof were Muslims.Footnote 45 This idea that “Islam noir,” however, is somehow inferior to some mythical, perfect form of Islam was evident in some of the French contemporary reports, particularly that of Chambonneau. That idea gained currency as the French increased their contact with the kingdoms of that region. Paul Marty based all his writings on Islam in the French colonies on this theory of an inferior “Islam noir.”Footnote 46 The idea is racist and incorrect.

The Wolof were and, for the most part, still are Muslims. As Colvin points out, there was a clear distinction between those who were clients of the Muslim leaders, the seriñ, and the rest of the population. We can now turn to how Islam was positioned in the society. The seriñ and their clients were like states within the state. They had their own villages, which were largely autonomous. Neither the seriñ nor their clients were required to provide soldiers for the dameel’s wars. They were also protected from domestic raids for slaves.Footnote 47

With a seemingly choice situation, why would the Muslims want to revolt? The jihads were calling for purification of Islam and a Muslim government, as opposed to a government of Muslims. There were Islamic communities headed by seriñ who administered their areas according to the dictates of sharia, as they understood it. The seriñ were originally from neighboring Futa Tooro, where Islam was foundational to the state or from present-day Mauritania. Futa Tooro was an ethnocentric Islamic state founded by the Denianke rulers in the late fifteenth century with the Haalpulaar’en migrations from Futa Jalon to Futa Tooro under the leadership of Tenguella. They were solidly Islamic, as were their Toucouleur relatives hailing from the medieval state of Tekrur, which was Islamic from the eleventh century. As such, Islam was integrated into the sociopolitical structure of the Haalpulaar’en states.

The Wolof states did not have such a strong integration. When members of the Wolof nobility joined the Islamic communities, they lost their rights as nobles.Footnote 48 Though most people identified as Muslims, a tension existed between those who received Islamic education and the nobility who received training on how to exercise power successfully.Footnote 49 Nasr al-Din’s call to jihad in the 1670s exacerbated these tensions.

In the 1660s, an Islamic preacher from the Zawaya Berber ethnic group named Ashfaga took the name/title Nasr al-Din, meaning “defender of the faith.” He began preaching Islamic reform in present-day Southern Mauritania, igniting the Shar Bubba Jihad. Sending forth missionaries, his preaching spread across the Senegal River into the kingdoms of Futa Tooro, Kajoor, Bawol, Jolof, and Waalo. He called for submission to Allah for the common people. For the rulers, he preached that they should “changing their life by observing the five prayers better, limiting themselves to three or four wives, getting rid of their griot (geuwels/gawlo) and the other people of pleasure around them, and that Allah wanted them to stop pillaging their subjects, selling them into slavery, and killing them, and other nice things.”Footnote 50

The rulers of these kingdoms did not submit. Beginning in 1673, Nasr al-Din’s preaching turned to violent conquest. After sending emissaries three times to the saltigué (ruler) of Fouta, Nasr al-Din and one of his military commanders Ennahouy Abdilby invaded Fouta Tooro. The saltigué fled in the wake of al-Din’s forces. Al-Din replaced him with Ennahouy Abdilby to rule as a vice-roy or governor under al-Din. The last conquered country, Waalo, has the most documented resistance. Fara Kumba, the brak (male ruler) of Waalo, mounted an unsuccessful resistance to Al-Din and his troops.Footnote 51 Nasr al-Din stated that he did not want to rule the conquered nations. He preferred that the kings submit to his words and follow in the Islamic reform. Instead, he was forced to fight and conquer them.Footnote 52

In Waalo, Al-Fadel ibn Muhammad al-Kaoury defeated and killed the brak. He offered command of the kingdom to one Kinary who was of the royal family.Footnote 53 Kinary suggested that he offer it to a more capable candidate, Yerim Koodé, who accepted and took the title buur jullit or the ruler/king who prays or master of prayer in Wolof. The new title distinguished from the traditional title of brak for the ruler of Waalo.Footnote 54

Unlike the governor of Fouta Tooro, the new buur jullit was of the royal family and, more importantly, the brother of the lingeer of Waalo, which gave him legitimacy.Footnote 55 The lingeer is the female ruler of the Wolof and Seerer kingdoms. Though the names of the male rulers vary, the name of the female ruler is lingeer in all the kingdoms. We will discuss the significance of the lingeer below.

Before taking Waalo, al-Din’s troops took Jolof, Kajoor, and Bawol. In Jolof, the troops of Nasr al-Din took over Jolof lead by their commander al-Fadel ibn Abu Yadel. The command of Jolof was given to Suranko, a man of Jolof who had been blind. According to Hamet, Suranko had a dream in which he would recover his sight and have command of Jolof.Footnote 56 This dream was obviously fulfilled when Ibn Abu Yadel conquered the country.

In Kajoor, the story presented in Hamet’s account and Chambonneau’s account differ significantly from one another and from the oral tradition of Kajoor. Ismaël Hamet translated the account of Walid al-Dimani in his Chroniques de la Mauritanie sénégalaise in 1911. Saad Bou copied the source, which was originally written in the early eighteenth century. Louis Moreau de Chambonneau’s documents are dated 1673–1677. Al-Dimani simply says that Kajoor was conquered and command of the country was given to Njie Sall (Andjai Sella).Footnote 57 He does not even give the name of the military commander who conquered it. He also adds that Bawol was conquered and the rule given to Habib Allah Sella, which may be Sall. Chambonneau writes that the dameel (male ruler) of Kajoor was killed. A new dameel was named, but soon fell prey to the songs of the geuwel (griot) who sang of his ancestors and of his cousin who had lost his life to the jihad. The geuwel sang so convincingly that the new dameel took them into his service again. Slowly the new dameel prayed less. Eventually al-Din heard of it and sent a vice-roy (presumably Njie Sall) to handle it. The new dameel fled from Njie Sal’s troops into Bawol to save his life.Footnote 58

According to both collections of oral tradition, at the death of Biram Yacine Bubu (the son of Yacine Bubu), his younger cousin Deché Maram Ngalgu succeeded him to the throne. Deché removed his aunt Yacine Bubu from the position of lingeer. The lingeer is always the sitting dameel’s mother, aunt, or older sister – and the oldest woman of his matrilineage. Yacine Bubu was qualified to remain as lingeer because she was Deché’s aunt. Deché removed her in favor of his mother Maram Ngalgu, who was Yacine Bubu’s younger sister. That decision upset the notables and the princes of the royal family because it went against the constitution.Footnote 59

The lingeer should be the oldest able-bodied woman of the dameel’s meen (matrilineage). Though Dyao and Fall do not elaborate on the underlying reasons for Yacine Bubu’s anger, Bamba Mbakhane Diop explains it by citing the formal custom that the lingeer must be the oldest member of the matrilineage. Yacine Bubu was the older sister. Deché went against the constitution to enthrone his mother.Footnote 60

Yacine Bubu decided not to take it lying down. She allied with an “influential marabout, the cadi” (Islamic judge), Njie Sal, through marriage. Dyao says Yacine Bubu’s daughter Anta married Njie Sall.Footnote 61 Fall says that Yacine Bubu married Njie Sall herself.Footnote 62 They could mean the same thing as the Wolof see marriage as a union of families. So, Fall’s assertion that Yacine Bubu married Njie Sall could simply mean that her family joined his in marriage.

Yacine Bubu’s slave army and the military partners of her son Biram Yacine Bubu joined the forces of Njie Sall and defeated Deché Maram Ngalgu. Just as the Arab and European sources do not mention Yacine Bubu, the oral sources do not mention Nasr al-Din or the advance of the jihad in the neighboring kingdoms. The oral tradition mentions that Njie Sall wanted to rule on his own, but Yacine Bubu insisted that he name her nephew Ma Faly Gueye as the dameel. This setup worked a few months. Then the disciples of Njie Sall caught Ma Faly drinking alcohol one day and assassinated him.Footnote 63

Yacine Bubu clearly wanted power to remain in the hands of the royal family, as her next actions displayed. Njie Sall had a theocratic state in mind with himself at the helm. Both oral sources imply this and Hamet wrote that al-Din left Kajoor under the control of Njie Sall. Yacine Bubu did not allow this to happen. Here again, the sources diverge in their details. Dyao says that Yacine Bubu took the reins and sent a secret message to Makhoureja Jojo Juuf, buur (ruler) of Saluum, another neighboring kingdom. The message said “come quickly and avenge the assassination of the one whose kindness made me forget (for a brief period) your poor dead brother Biram Yacine. I will help you regain his title from the hands of these violators and it is you who will wear this title of dameel. You are the rightful heir.”Footnote 64

Fall writes that Yacine Bubu was livid after the assassination. He then goes on to say that, after a secret meeting of the assembly of notables, it was decided to invite Makhoureja Jojo Juuf to come and avenge the death of his brother and be elected dameel. The importance is that Fall implies that Yacine Bubu was active in the decision to invite Makhoureja in, but it does not explicitly say it. Dyao, however, gives her full agency as lingeer to act in such a way. From this reading, we see that Yacine Bubu’s actions were decisive in this jihad. Why was this ignored in all the secondary sources that covered this episode?Footnote 65

Yacine Bubu and the Sharr-Bubba Jihad

Ignoring the importance of the lingeer leads to gross misinterpretation of the events of this jihad. Philip Curtin writes about the incident, ignoring certain details of the oral record. The oral record recounts that Njie Sal initially had no intention of giving up the throne. Curtin writes that Njie Sal ruled as al-Din’s viceroy, totally ignoring Njie Sal’s illegitimacy and obvious military weakness, but adding that it was al-Din’s policy to find a suitable member of the royal house to rule in al-Din’s name. Curtin goes on to say that Ma Faly proved to be “unworthy,” leading to al-Din ending Ma Faly’s reign.Footnote 66

The oral record, working from a clear understanding of the Ajoor paradigm of power, gives agency to the lingeer Yacine Bubu. It was she who chose to ally with Njie Sal with the express purpose of regaining her position as lingeer. It was she who insisted on Ma Faly being dameel. Njie Sal’s disciples assassinated Ma Faly after he was caught drinking, but it was again Yacine Bubu who decided to end Njie Sal’s rule. Chambonneau points out that Nasr al-Din did not have a strong force once he entered Fouta Tooro.Footnote 67 It is highly likely that Njie Sal had been acquiring disciples in Kajoor, but, clearly, he knew he did not have enough support to overthrow the dameel. He allied with Yacine Bubu either out of a need for military support or legitimacy.

Having a lingeer ask to be his ally was like placing a gift in his lap. The oral record and secondary sources are remarkably silent on the role and significance of the lingeer. These sources all simply say that it was a position held by the mother, aunt, or older sister of the sitting dameel or buur. We can only assume that the secondary sources did not fully understand the power and importance of the lingeer. All the kingdoms of the region had a lingeer, including Waalo, Kajoor, Bawol, Siine, and Saluum. It was not simply a ceremonial position. In Kajoor, the dameel had to be of royal blood from his patrilineage and his matrilineage. The matrilineage was the kingship tie that supplied partisans in this king network. The position of lingeer was a symbol of honor for the matrilineage and all the support that came with it.Footnote 68

The lingeer was also much more than a symbol. In some Senegambian kingdoms, she was a member of the royal council and had the authority to convene the council. Her opinion was a counterweight to that of the sovereign. She also had an army comprised of her slave soldiers and clients as well as fighting members of the matriclan. The lingeer’s income came from a province which paid taxes to her.Footnote 69 She was the head of all the women of the kingdom. Thus, as men went to the sovereign or his appointees when there were problems, the lingeer presided over all the issues involving women.

The lingeer is not a queen. Queens are the wives of kings in the Western monarchal systems. Their power is ceremonial except in certain circumstances, and their power is dependent upon their husbands. If a king allows his wife to have power, she has it; otherwise her power is in her ability to produce sons to sit on the throne after her husband is dead. If a queen’s husband dies and leaves an under-aged heir, she can act as a guide for a young heir, though a man is usually chosen as the regent. If a king dies and leaves only female heirs, then his daughter can become a queen with the same powers and rights of the king. In the European monarchy, there is no place for a woman sharing power with a man.

The lingeer is not a queen-mother, though this term is often used to describe such a position. As stated above, the queen-mother is the mother of the sitting monarch in the European system. She has no power beyond the ceremonial. Her status is lower than that of her son’s wife who is the sitting queen. Queen-mothers are respected and her level of actual power is dependent on how much the sitting monarch allows her to have.

The lingeer is the other half of power in a dual-gender system of authority that is practiced in various manners throughout Africa.Footnote 70 As such, the lingeer is the “mother” of the kingdom. From this foundational information, we can clearly see that the lingeer was an important position to which women aspired. Only the oldest woman of one of the garmi families was eligible to be named lingeer, and this, under the condition that a man of her meen was chosen as dameel. Like the queen of the Western tradition, in Kajoor the lingeer’s position depended on that of her son, nephew, or brother. If he ceased to be dameel, she could continue as lingeer only if another dameel was chosen from her meen, which was the case with Yacine Bubu. However, if a dameel was chosen from another meen, the lingeer would change.

In Waalo, Kajoor’s neighbor to the north, the lingeer was elected independent of the brak and kept her power until death.Footnote 71 Whether chosen by the male ruler or not, unlike the European queen, the lingeer possessed power that was hers alone. The lingeer had access to an income derived from the state, governing decisions over a province, and access to military power. There are examples of lingeer throughout the Wolof and Seereer kingdoms that did remarkable things, but the fact that they had power to exercise is not at all remarkable. It is a central tenet of the system. We have examples of the Lingeer Jambur-Gel, noted for her insistence on the importance of the matrilineage in succession as well as her cruelty to the badoolo; Lingeer Njombot (ca.1811–1846) and her influence in choosing a brak of Waalo as well as her insistence on marrying who she wanted; and her sister Lingeer Ndate Yalla (ca. 1814–1856) and her influence in Waalo just before the conquest.Footnote 72 There are accounts of noteworthy lingeer of Kajoor such as Lingeer Ngone Dieye (r. 1695–?), who intervened regularly during the reign of her son Latsukaabe in attempts to curb his excesses with the French.Footnote 73 There are other lingeer mentioned in the history of the kingdoms of Siine and Saluum. A lingeer’s prerogative was to protect the meen, or matriarchy, and, in doing so, to secure the future of the kingdom. Yacine Bubu actions are representative of that responsibility.

Yacine Bubu

“The mother of the late Damel had been removed from her office as lingeer, or chief woman of the kingdom, by the reigning Damel, Detie Maram. Her following joined the religious rebels and the invading army.” This is Philip Curtin’s description of Yacine Bubu. He clearly takes the time to mention the Damel’s name, yet relegates Yacine Bubu to “mother of the late Damel” and “chief woman.”Footnote 74

This ontological violence is no different than reports of Sandra Bland’s death attempting to relegate her to the non-descript collectivity of Africana women who are and have been on the receiving end of violence (ideological, mental, emotional, and physical) from an epistemic paradigm that consistently devalues feminine bodies, particularly non-white ones.Footnote 75 This article has sought to correct this violence. So, we say her name: Yacine Bubu.

Curtin minimizes her role in the success of the jihad. Neither Al-Yadali, the Arab chronicler, nor Chambonneau mention Yacine Bubu. Curtin’s reliance on these sources explains why he chose not to give her the credit. Also, reading Curtin’s footnotes, it appears he did not consult the notebooks of Yoro Dyao or the work of T.L. Fall. However, Curtin references Brigaud’s Histoire traditionelle du Sénégal and thus had access to the details of the oral history, yet he neglected to mention Yacine Bubu’s name.Footnote 76

The accounts of T.L. Fall and Yoro Dyao, however, do mention her and what she did to make the jihad successful and how she ultimately brought it down. The oral sources are more potent in this case because they were passed down through the centuries from people who were on the inside of Kajoor; further, the information that they provide cannot be found in the written sources of outsiders. All historical sources have their weaknesses. Clearly, as chronicles of the royal establishment, the oral sources have limitations. They do not mention the participation of the badoolo in the jihad as we cull from the Arabic sources and those of Chambonneau. They do not mention Nasr al-Din or the interesting history of his proclamation of jihad. They also do not mention the dameel’s reaction to the call to jihad. However, the oral record gives us the detail of how this jihad started and ended in Kajoor. Knowing the chronicles’ purpose and weaknesses, we must acknowledge its primary strength, which is centered in on the locality of this multi-monarchy jihad.

As members of the Wolof aristocracy, Dyao and Fall left room for the importance of their native institutions. The lingeer is one of those institutions. The lingeer as a woman with power and authority to rally a military force behind a dubious Muslim leader is not presented as anything particularly remarkable. The details of the story are presented plainly, and then the chronicles move on to the next dameel discussed. The failure of the other scholars to see these significant events seem to be the result of ethnocentrism (if not White supremacy) and the consequent sexism. I do not judge them harshly knowing they are only the products of the world that produced them. (I only pray future scholars are kind to me for my shortcomings.) However, a deeper search could have revealed more about the jihad’s details.

Intellectual captives of their narrow experiences within a Eurocentric or American paradigm and/or patriarchy, while not understanding the position of lingeer, previous scholars understated the prestige and power of our central character, Yacine Bubu. Translating lingeer as “queen” or “queen-mother” contributes to the confusion, for she was neither. The position of lingeer does not exist in Western monarchies nor does any comparable position. The term “chief woman” does, in many ways, capture this lack of understanding without engaging it. Through jumping this hurdle of understanding, I have attempted to shed new light on this episode and by extension the entirety of African political history. Yacine Bubu was not only powerful and a pivotal figure in this episode, but she also acted decisively to prevent the disintegration of Kajoor into an Islamic state. As lingeer, mother of the state, and protector of the matrilineage, this was her responsibility.