Introduction

The drum kit, an instrument deeply rooted in popular music traditions, is a defining element of many popular music styles. Since the early twentieth century, generations of drummers have explored new musical and technical possibilities of the instrument and, recent years, the drum kit has emerged in contemporary classical music settings as a solo instrument with prescribed notation. In this chapter, contemporary classical music refers to music being written now, or in the past few decades by composers operating within the framework of Western classical music notational traditions. While there is a growing interest in this repertoire today, composers have drawn inspiration from the drum kit since the early developmental stages of the instrument in the early twentieth century. I will present an overview of composed works starting with Darius Milhuad’s La Créations du Monde from 1923 and ending with Nicole Lizée’s Ringer from 2009. I will show that early approaches to drum kit composition began as an assimilation of existing popular music styles with little progression in performance techniques and expression for the instrument. In recent years, many composers have approached drum kit composition by balancing contemporary classical music techniques with the drum kit’s rich traditions, grooves, and styles to make something progressive and new. Through my own commissioning, performances, and research I have contemplated the elements that led to this confluence in contemporary classical drum kit music.

Personal Background

In 1988, I began taking drum kit lessons in my hometown of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Thanks to the exceptional drum instruction of my teacher David Schneider, I embraced a wide range of styles and playing traditions. I went on to play in a variety of bands ranging from punk, progressive rock, and reggae styles. After highschool I decided to pursue a music degree, but I chose to focus on orchestral and concert percussion instead of drum kit. I received a Bachelor of Music degree from McGill University in Montréal and a Master of Music degree from the State University of New York in Stony Brook, both in contemporary classical percussion performance. No longer receiving drum kit instruction, and with little time for playing in bands, I was quickly distinguishing myself as a classical percussionist rather than a drummer.

After my Master’s degree, I returned to Manitoba where I began teaching percussion at Brandon University and playing regularly with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. Around this time, I began to consider if the drum kit could have a greater role in my life of contemporary classical performance. I knew of a few composed works for drum kit such as Frank Zappa’s ‘The Black Page’ and Louis Cauberghs’s ‘Halasana’, and I wanted to expand on what I saw as a limited amount of repertoire. In 2006, I sought out and was successfully awarded my first commission of the solo Train Set by composer Eliot Britton.

In 2007, I met composer Nicole Lizée while performing her chamber work This Will Not Be Televised with members of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. Pleased with my performance, Lizée invited me to play drum kit for various works on her debut album This Will Not Be Televised, released by Centrediscs in 2008. That same year, with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, I commissioned Lizée’s first solo for drum kit, Ringer. Encouraged by these new experiences, in 2010 I returned to McGill University in Montréal to complete a Doctor in Music degree where I wrote my dissertation ‘Defining the Role of Drumset Performance in Contemporary Music’. As of today, through collaborations with composers from around the world I have premiered an extensive collection of contemporary classical drum kit solos, chamber works and concertos. My solo drum kit album Katana of Choice – Music for Drumset Soloist was called ‘a modern classic’ by I Care If You Listen and the title track by Nicole Lizée was nominated for a JUNO (Canadian music award) for best classical composition in 2019. When I consider my broad range of musical training and performance experience it seems natural that I am drawn to an artistic practice that crosses between genres. I draw from this personal experience to articulate broader points about the place of the drum kit in the classical world and the unique skill sets required when approaching the drum kit in contemporary classical music.

Drummer or Multiple Percussionist?

In contemporary classical music practice, the term ‘multiple percussion’ is associated with a body of repertoire for the solo percussionist, which incorporates several instruments played by a single performer. As drum kit repertoire appears increasingly alongside works for multiple percussion, there is a tendency to place such performers and repertoire in the same categories. Drummer Max Roach was said to have brought ‘dignity to an instrument long misunderstood and assaulted by the ignorant’ and set a precedent by referring to himself as a multiple percussionist in album liner notes.1 At the time, this reflected his elevation of drum kit performance and the desire to be considered equal to the other instrumentalists.

As solo drum kit repertoire in contemporary classical music has increased, the discussion of its inclusion in college percussion pedagogy has led some authors to still justify its existence and continue the comparison to multiple percussion. The 2012 dissertation by Kevin Nichols called ‘Important Works for Drum Set as a Multiple Percussion Instrument’ provided an introduction and unique performance perspective to composed drum kit solos such as The Sky is Waiting … (1977) by Robert Cucinotta, One for Solo Drummer (1990) by John Cage, Brush (2001) by Stuart Saunders Smith and others. He noted the lack of studies or method books which ‘investigate the literature for drum set as a multi-percussion instrument’ and expressed his ‘desire to encourage solo drum set performance and composition by making this music and these concepts more widely known and understood’.2 Murray Houllif’s ‘Benefits of Written-Out Drum Set Solos’ encouraged solo repertoire for students as ‘an effective means to learning improvisation’.3 In ‘Drum Set’s Struggle for Legitimacy’, Dennis Rogers argued that written recital pieces can demonstrate that the ‘drum set is a legitimate instrument that is quite acceptable in the percussion curriculum’.4

In this chapter, I use the term drum kit without association to multiple percussion. I do so to distinguish the drum kit as an instrument worthy of its own legitimate considerations, apart from earlier efforts to elevate the instrument’s status. The label of multiple percussion places an unwanted shadow over the popular music styles and the associated players, techniques, and instruments that are the foundation of the instrument.

What, then, clearly distinguishes drum kit from other contemporary or multiple percussion performance? The Encyclopedia of Percussion says that the drum kit is ‘a set of drums, usually bass drum, snare drum, tom-toms, hi-hat, and cymbals’.5 James Blades describes drum kit performance as ‘the advancement of counter rhythms and independence’.6 Jazz drummer Kenny Clarke described his use of multiple limbs as ‘coordinated independence’.7 Combining these ideas, I suggest that the definition of drum kit performance is: the use of coordinated independence of multiple limbs on a collection of drums and cymbals, including but not limited to, bass drum with pedal, snare drum and hi-hat, set up for convenient playing by one person.

Early Drum Kit Composition Via Jazz Assimilation

La Création du Monde (1923) by Darius Milhaud

The earliest approach to drum kit composition appeared in Darius Milhaud’s ballet, La Création du Monde, premiered on 19 October 1923. Like many European composers of the time, Milhaud assimilated the sounds, instruments, and performance practices of the exciting new popular music style from the United States called jazz. Milhaud drew inspiration from the words of the artist Jean Cocteau. In his manifesto, Le Coq et l’Arlequin (1918), Cocteau called for a new sound in French music, dismissing the more ‘Russian-inspired impressionism’ of past composers such as Claude Debussy.8 ‘Enough of clouds, waves, aquariums, waterspirits, and nocturnal scents; what we need is a music of the earth, every-day music’.9 Cocteau encouraged composers to draw inspiration from the new sounds of jazz, bringing together the ‘low-art’ of the cafés and dance halls and exoticism of African culture into a new French modernist approach.

Author Bernard Gendron described Milhaud as a ‘modernist flâneur’ who was ‘more akin to the tourist, the slummer, and the fashion plate, than to the ethnomusicologist’, and Milhaud’s ‘adventures in curiosity and assimilation’ resulted in a very limited reflection and understanding of jazz and along with this, the drum kit.10

The limited understanding of jazz music assumed the term to include a variety of styles and techniques including blues, ragtime, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band’s popular take on ragtime known as Dixieland, Tin Pan Alley songs from New York City and, generally, any music played by dance bands at the time. The drum kit was at the centre of this style.

Despite the confusion during these early days, there was at least one common musical meaning when people in France invoked the term jazz: it meant rhythm and the instruments used to make it. Above all, the drums – la batterie – were not only the most prominent instrument but their mere presence, many believed, made any band into a jazz band.11

Milhaud toured through the United States in 1922 where he searched for what he called the ‘authentic’ elements of jazz.12 Immediately upon returning to Paris, Milhaud began to work on the music for the ballet, La Création du Monde for seventeen instrumentalists including drum kit. The drum kit included snare drum, bass drum with foot pedal, woodblock and cowbell. The ‘grosse caisse à pied, avec cymbale’, meaning ‘kick drum with cymbal’ referred to the ‘clanger’, a predecessor of the hi-hat.13 Milhaud indicated in the music when to activate or deactivate the clanger against the mounted cymbal.14 Ragtime rhythms common in the twenties were imbedded in the music with written out triplet figures, and instructions for rim shots and other jazz idioms were found throughout.

To appreciate how Milhaud assimilated the style, I recommend listening to Baby Dodds’s 1946 recording on Folkways Records for reference of period ragtime performance. Having remained committed to the drum kit instrumentation of the twenties (Dodds never took up the hi-hat, for example) the recorded solo Spooky Drums in particular is a window into early drumming and gives an authentic reference to ragtime rhythms and their placement around the drum kit.

Milhaud was not the only composer to assimilate jazz and, as a result, drum kit elements into the contemporary classical setting. Here is a brief list of other works that followed: George Gershwin, Rhapsody in Blue (originally for the Paul Whiteman Jazz Orchestra, 1924); Mátyás Seiber, Jazzolettes (1928); Igor Stravinsky, Preludium for Jazz Band (1936 / 37); William Walton, Façade, Second Suite (1938); Gunther Schuller, Studies on Themes by Paul Klee (1959); and Leonard Bernstein, Symphonic Dances from West Side Story (1960). While these composers included popular elements of early jazz and, along with it, the drum kit into a contemporary classical work of the 1920s, the music often suffered the fate of the limited understanding of the style. Milhaud himself bemused that ‘the critics decreed my music was frivolous and more suitable for a restaurant’.15 With works such as La Création du Monde we were given an early glimpse of a search for legitimacy of jazz in a classical setting and a hope that the new ‘everyday music’ would provide inspiration and new approaches to composition. It is a familiar theme when exploring the history of compositions for the drum kit and one we know still exists in recent discussions about percussion pedagogy. Jazz did not benefit from being placed in the concert hall, just as the drum kit did not need to be called multiple percussion.

Drum Kit Composition as Homage

Bonham (1989) by Christopher Rouse

Written for drum kit and percussion ensemble, Bonham by American composer Christopher Rouse was ‘an ode to rock drumming and drummers, most particularly Led Zeppelin’s legendary drummer, the late John (“Bonzo”) Bonham’.16 The work was for eight players: one drum kit and seven other percussionists. It was premiered in 1989 by the Conservatory Percussion Ensemble, conducted by Frank Epstein, at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston.

In Bonham, the drum kit opened, and continued throughout much of the piece with an ostinato (repeating pattern) that quoted the iconic John Bonham groove from the song ‘When the Levee Breaks’ from Led Zeppelin IV (1971). The ‘Levee’ groove had been highly sampled by other popular artists such as Bjork, The Beastie Boys, Depeche Mode, Dr Dre, Coldcut, and Eminem. In Bonham, fragments of other Led Zeppelin songs such as ‘Custard Pie’, ‘Royal Orleans’, and ‘Bonzo’s Montreaux’ appeared in aspects of the drum kit music as well as throughout the entire ensemble, but it is the ‘Levee’ groove that defined the piece.

In the case of Bonham, the performer had to become familiar with the elements that made John Bonham’s sound iconic. Rouse recommended in the score that the drummer ‘use the fattest possible sticks to reproduce as closely as possible throughout the entire work the beginning of “When the Levee Breaks”, recorded by Led Zeppelin’.17 This referenced the legendary drummer’s reputation for being a powerful, dynamic player – so powerful, in fact, that he is often credited for being an early influence on the heavy metal drumming that would follow him. Jon Bream in Whole Lotta Led Zeppelin said, ‘no drummer ever created such a monstrous sound, and in Bonham’s force field of rhythm there ranks the basis of the sound now called heavy metal’.18

The drum kit performer should have not only adhered to Rouse’s suggestion of heavy sticks, but must have looked further into the characteristics of John Bonham that resulted in such a powerful sound. For example, Bonham played on large size drums associated mostly with his Ludwig Amber Vistalite set made from acrylic which was being commercially produced as ‘Plexiglas’ in the seventies. Another contribution to Bonham’s unique sound was the experimental recording techniques used by engineer Andy Johns and the band. While some variations on specifics exist, the basic concept was that the drums were placed at the bottom of a staircase, with microphones placed above, one or two floors up. This was ‘distant from the Beatlesque, cloth-covered drumhead sound that was de rigueur at the time’, which produced more clarity and articulation.19 Instead, the drums were given room to resonate while the microphones captured the natural power of John Bonham’s performance style.

The John Bonham sound on ‘When the Levee Breaks’ was a combination of the drummer’s distinct power and feel combined with his choice of instrument and the groundbreaking recording techniques that captured it all. Christopher Rouse’s suggestion for the ‘fattest possible sticks’ could not alone reproduce this complex sound. The drummer approaching Bonham should rather be educated in the important elements described above that formed the Bonham sound and draw from as many influences as possible to even come close.

The popularity and success of Rouse’s work, Bonham, was rooted in the adoration and idolization of a drumming icon that is common among generations of musicians. Placing Bonham grooves within the classical percussion ensemble context was an homage to this drummer and the music of Led Zeppelin. This type of composition remains popular within the classical percussion ensemble community because it allows players to explore drummers and styles that often have been separated from the typical focus in Western classical music. Similar approaches for drum kit and percussion ensemble include John Beck’s Concerto for Drum kit and Percussion Ensemble (1979), written for ‘Tonight Show’ drummer Ed Shaughnessy, and Larry Neeck’s Concerto for Drum kit and Concert Band (2005) featuring a rock groove in the style of Sandy Nelson, a jazz-waltz influenced by Joe Morello and a Gene Krupa, up-tempo swing.20

While recorded history has endless examples of drum solos, the drum kit as concerto soloist was indeed a new role found in the above works. What kept these works tied to their predecessors such as Milhaud is that the music was still copying styles and therefore not exploring new performance practices of the drum kit. The only thing new for drum kit was the performance context itself. We still ran the risk of displaying the traits that Gendron described in Milhaud’s case as ‘his excessively formalistic approach … his underestimation of performance at the expense of composition … his simplistic schemes of classification, and his virtual ignorance of the cultural and social context’.21 In the case of Bonham, the limitation was in the impossibility of recreating the drumming style of John Bonham. By placing such a reproduction of an iconic groove into the formula of contemporary percussion ensemble composition we have missed the true significance and brilliance of the original performance of John Bonham with Led Zeppelin and run the risk of sounding like a gimmick or simplifying the greatness of this performance.

As I have stated before, it is the drum kit’s roots in popular music and its rich traditions, iconic players, grooves, and styles that remain tied to the instrument at all times. It is what the previous composers were counting on as they quoted jazz or rock tradition. It took an artist equally versed in rock and contemporary classical music to create the first drum kit solo that seemed to be progressive rather than repeating the past.

Genre Cross-Over in Drum Kit Composition

The Black Page (1976) by Frank Zappa

The legendary rock bandleader Frank Zappa was able to cross over to contemporary classical traditions by writing chamber works for Ensemble Intercontemporain and conductor Pierre Boulez, among others and was said to ‘somehow manage to work with these many, many influences … for many composers this would be a really big danger, to get lost in all those things you could do … but he’s really original at using all these influences’.22 Zappa did not approach writing with regards to labels and class and he ‘refused to rank his own works or engage in debates regarding the difference between “popular” and “serious” music. It was all one to him’.23

Written for drummer Terry Bozzio, The Black Page was an ambitious solo expressing the melodic potential of the drum kit featuring an excessive use of nested polyrhythms and complex patterns demanding unusual crossing of limbs and rapid movement around the drum kit. The typical function of the bass drum foot changed. No longer the timekeeper and foundation, the bass drum was equally involved with the hands in the thematic and melodic material. While not indicated in the score, Bozzio added a constant quarter note pulse with the hi-hat foot in the original recording, a feature adopted by all future performances, and one that has remained standard practice today.24 This simple addition created a stable, familiar framework for the rhythmic complexity. Even with these complexities the solo still had an accessibility through an overall sense of groove that never strayed too far from the familiar. The performer and listener can hear a connection to the iconic drum solos of the past such as Gene Krupa’s solo in ‘Sing Sing Sing’, Max Roach’s ‘The Drum Also Waltzes’ or John Bonham’s many live solos with Led Zeppelin.

Because of the notational complexity and technical challenges mixed with rock sensibilities, The Black Page was a true crossover work and demonstrated a confluence between musical influences and new potential for drum kit composition. Just as important, the solo encouraged a new level of performer equally comfortable in contemporary classical music notation and rock-based drumming. Terry Bozzio described his progression since working with Frank Zappa and The Black Page:

Apply theory, harmony, and melody orchestration … to the modern drum kit, because it has evolved to the point where we can do those things. I see no difference between an organist who plays lines with his feet and four different voices with his two hands and the contrapuntal possibilities that are extant on the modern drum set.25

Complexity in Drum Kit Composition

Ti.re-Ti.ke-Dha (1979) by James Dillon

James Dillon was born in Glasgow, Scotland in 1950, and spent considerable time living in London. As a teenager in the sixties, he was drawn to rock and played in a rhythm and blues band called Influx.26 Dillon eventually pursued post-modern composition, but he did so on his own terms, receiving formal education at a university level for only two years before leaving disillusioned. Even so, by the mid-seventies Dillon was considered a part of the New Complexity school of composition and his music was described as ‘close to if not beyond the limits of performability, justified by reference to the fearsome intellectual discourse which is said to lie behind those torrents of notes’.27 While this style of composition often held a reputation of being elitist or overtly formalist, Dillon said that composing in the seventies was a time ‘to claw my way back to where music still has meaning and not present some kind of second-hand experience’.28

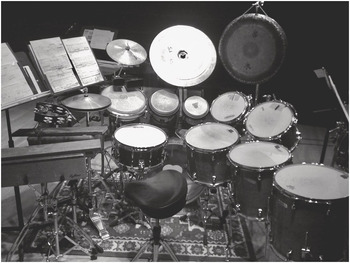

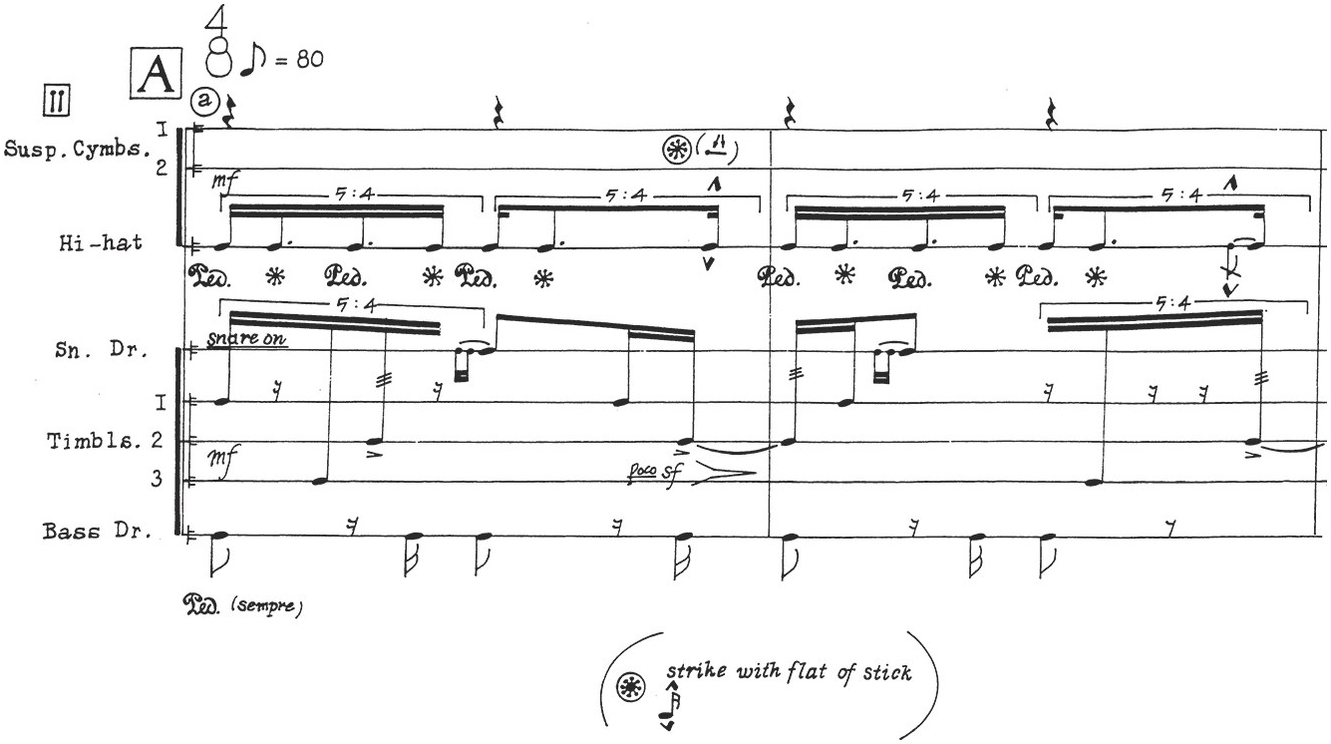

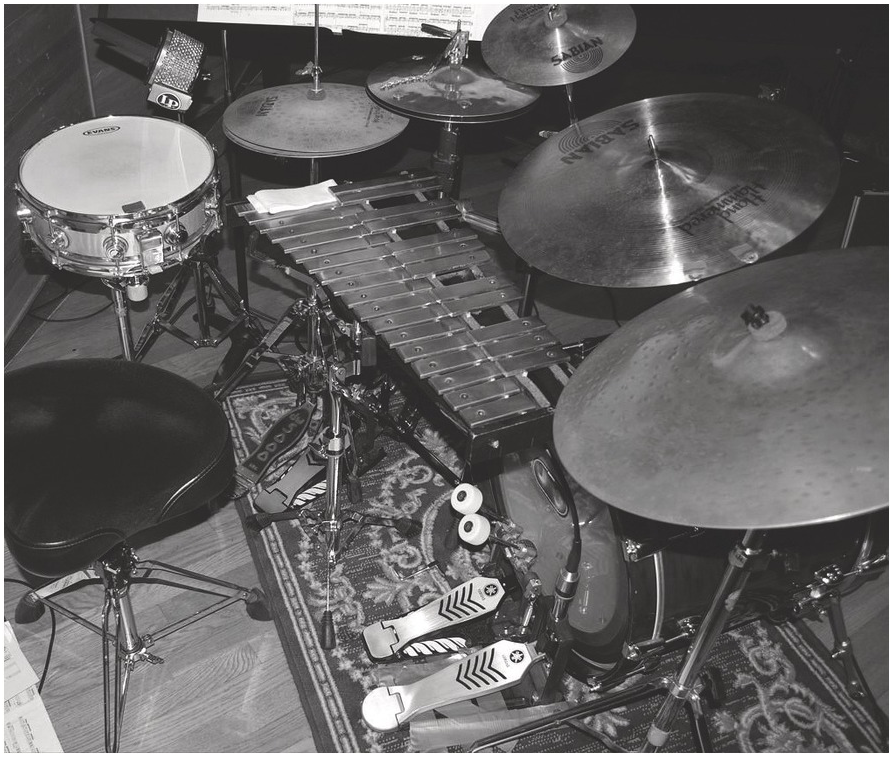

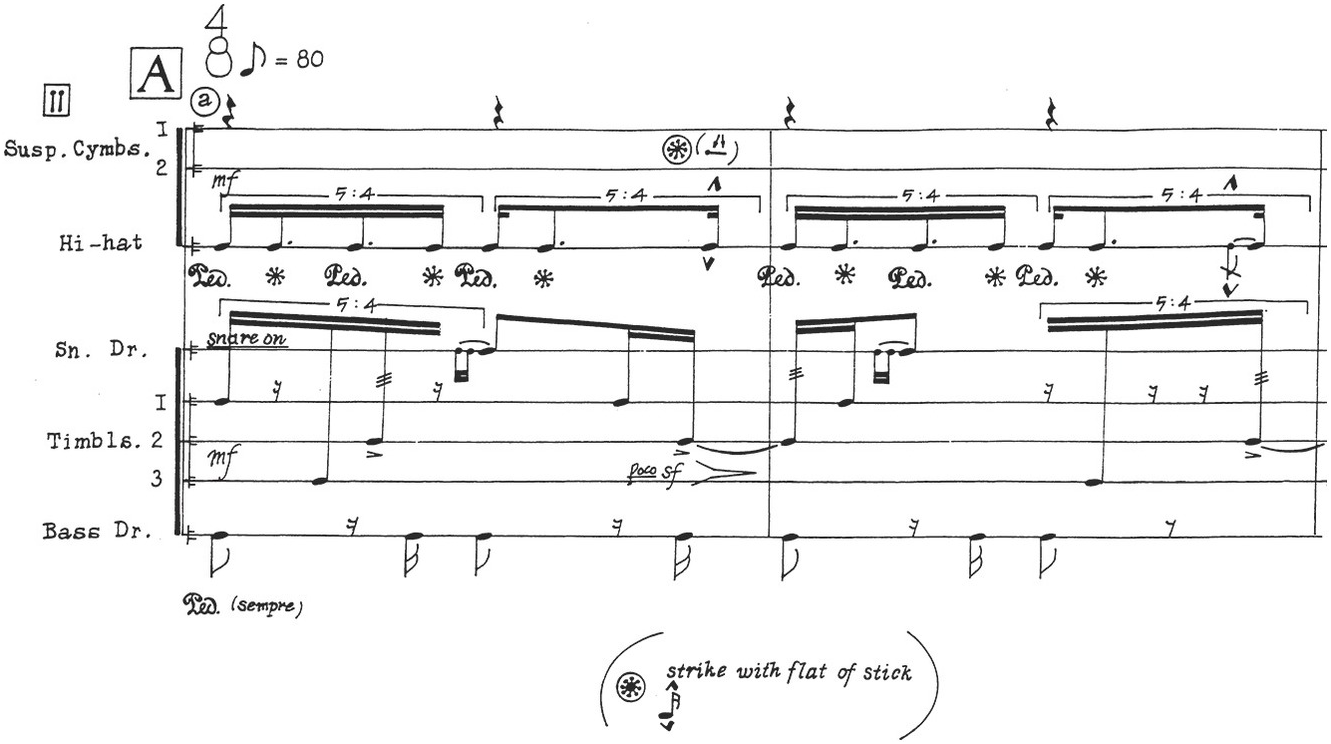

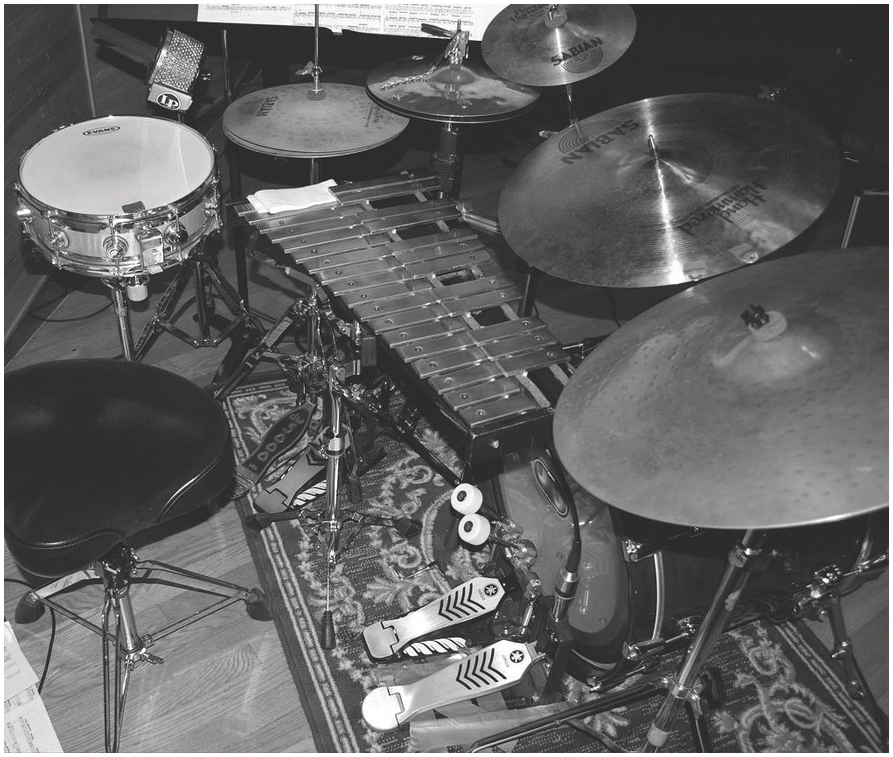

In 1979, Dillon wrote Ti.re-Ti.ke-Dha in celebration of the ‘International Year of the Child’.29 It was premiered by percussionist Simon Limbrick in South Bank, London, 1982.30 The complete list of instruments in Ti.re-Ti.ke-Dha extended beyond the common drum kit to form a massive setup with additional suspended cymbals (one screwed tightly and struck only at the dome), cowbells, hi-hat (with a collection of sleigh-bells attached to top), log drums, snare drum, three timbales, five tom-toms, bass drum with pedal, tam-tam and a bellstick (Figure 6.1). Balancing efficiency and playability with the unusual instrumentation and complex polyrhythmic material resulted in one of the most challenging works in contemporary drum kit repertoire. How each individual interpreted and solved these challenges is part of what made a performance unique. To illustrate, the following section presents two examples of setup challenges and recommended solutions.

The timbales had a far greater involvement in the music than the traditional tom-toms (which only enter at measure 82). Dillon’s recommended layout in the score recognized that they needed to be easily reached, placing them directly in front of the player with the tom-toms to the right. The timbales’ size and inability to be mounted on traditional drum kit hardware posed logistical issues. Also, the timbales had similar timbres to the tom-toms causing some difficulty in making a distinction between the two voices. As shown in Figure 6.1, replacing the timbales with a set of bongos and a travel conga offered a bright, short attack, distinct from the thunderous, resonant tom-toms. Not only sonically effective, they were compact and fit efficiently onto the drum kit.

Dillon also specified two log drums, each producing a single pitch. Generally placed on a flat surface, such as a trap table, the log drums did not attach to any type of hardware. Balance was also a problem since the log drum characteristically featured a ‘warm sonority with limited carrying power’.31 Since Dillon specified the use of snare drumsticks throughout the piece the sound produced from attacking the log drum was lacking in tone and volume. Shown in Figure 6.1, the solution was to attach a piece of ‘purpleheart’ wood onto, and extending beyond, each log drum to allow for a resonant attack area and mount each on a snare drum stand. A thoughtfully chosen setup improved efficiency of motion around the drum kit and clarified some of the dense layers of complexity which Dillon placed into his work.

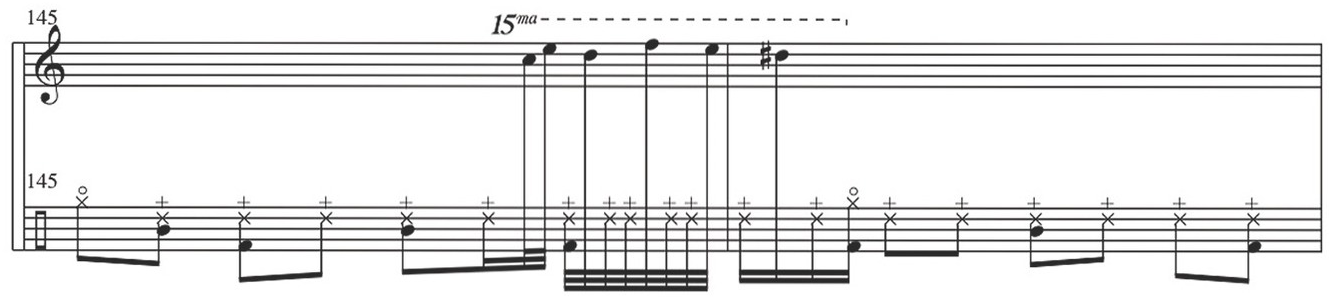

Dillon employed three common hi-hat practices: loud foot attacks that splashed the cymbals together, dryer foot closing ‘chick’ sounds and playing the hi-hat with sticks. Traditionally used as a time keeping device or for accentuating the pulse, Dillon extended these techniques to be part of the upper layers of thematic material and linear movement (Figure 6.2). The constant execution of these complex foot techniques combined with polyrhythms was an exercise in multiple limb independence, polyrhythmic proficiency and physical balance. A drummer relies on a basic balance when performing and as Grammy-award winning drummer Paul Wertico stated, ‘it’s usually easier to feel balanced when playing simpler exercises. Grooves that require complex counterlines and polyrhythms can sometimes make you feel as if you’re going to fall over’.32

Figure 6.2 Foot techniques: closed HH with foot (𝆯); open HH with foot (𝆮); HH struck with stick (𝆜); repeating bass drum pulse, mm. 1 and 2. James Dillon: Ti.re-Ti.ke-Dha. Edition Peters No.7242 © 1982 by Peters Edition Limited, London.

While large drum kits, foot variations and polyrhythmic playing were all common tools of the modern drummer, James Dillon put these elements to the extreme in Ti.re-Ti.ke-Dha. Challenges with the setup, notational complexity and even basic balance demanded a unique combination of performance skill, much like The Black Page did a few years prior. Also similar is Dillon’s ability to combine New-Complexity style notation (more common with contemporary percussion performance practice than drum kit) with advanced drum kit techniques and fundamentals.

Recontextualization in Drum Kit Composition

Ringer (2009) by Nicole Lizée

Canadian composer Nicole Lizée has been commissioned by a wide range of artists such as Kronos Quartet, So Percussion, and BBC Proms. Her music has often involved unorthodox instruments such as the Atari 2600 video game console, omnichords, stylophone, and karaoke tapes. Lizée’s music has shown her pervasive interest in the drum kit and its connection to time, groove, popular music styles, and iconic performers. In her works for drum kit, she has expanded upon traditional performance practices through what she called recontextualization:

Referring to the past (or other contexts) but twisting, manipulating to create something new, vital, and meaningful to me (and to the ‘now’), without losing trace of its origins, place in history, functions, etc. but reinterpreting, filtering and distorting all of these – and placing it in a new context.33

I commissioned and premiered the drum kit solo Ringer by Nicole Lizée in 2009. It was recorded for my album Katana of Choice – Music for Drumset Soloist in 2017 and has been performed by other contemporary drum kit players around the world. Lizée referred to iconic drum kit grooves (such as John Bonham’s in ‘When the Levee Breaks’) as ‘classic drumset paradigms’.34 The solo Ringer for drum kit was a recontextualization of such paradigms in which ‘the end result is intended to be at once familiar and alien’.35 This involved the emulations of drum machines and samplers behaving erratically, fragments of classic grooves characteristic of electronica and dance music warped and iconic drummer Steve Gadd’s paradiddle grooves reimagined as rhythmic and melodic themes.

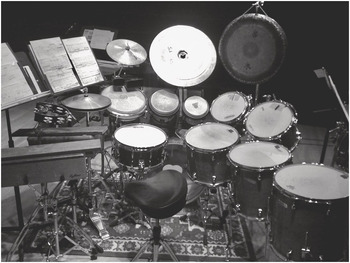

The drum kit in Ringer included kick drum with double pedals, hi-hat and remote hi-hat with pedal (placed to the right of the main kick drum pedal), snare drum, cabasa, cymbals (ride, splash and sizzle) and glockenspiel (Figure 6.3). The arrangement came from personal discussions with Lizée while trying samples of the material during the composers writing of the work and during preparation of the premiere.

Figure 6.3 Drum kit setup for Ringer.

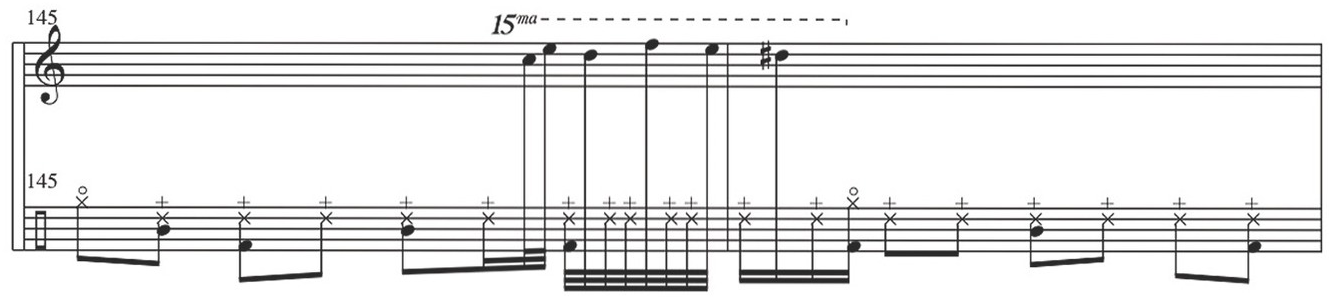

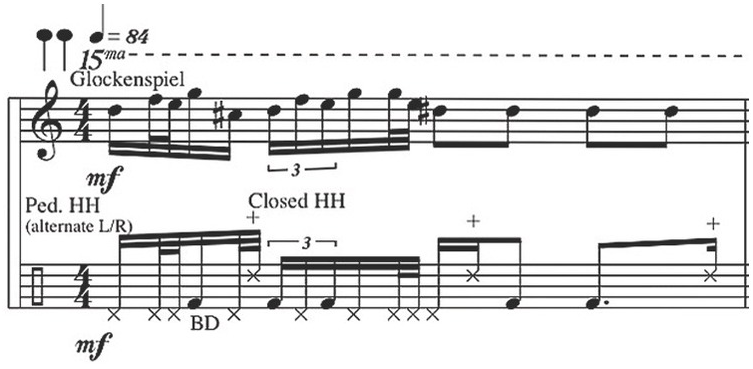

The glockenspiel was placed where the snare drum typically is on a drum kit. By doing so ‘the glockenspiel overtakes or replaces … the snare. In place of what would usually be pitchless accents and articulations, melodic fragments are formed’.36 This was most obvious in the section constructed around drummer Steve Gadd’s paradiddle grooves. Since the seventies, Steve Gadd has been considered one of the greatest drummers of all time, and he has changed how players approach the drum kit and even how the instrument was made. Endorsed by Yamaha since 1976, Gadd’s Yamaha Recording Custom drum kit defined the drum sound of the eighties.37 Gadd also established a signature groove commonly referred to as the ‘Gadd Paradiddle’ based around the sticking of the paradiddle rudiment (R-L-R-R, L-R-L-L) and its multiple variations. In Ringer, the Gadd Paradiddle was morphed and extended around the drum kit, most notably the glockenspiel. Ringer required advanced double bass pedal technique and double hi-hat pedal technique in rhythmic unison with hands (Example 6.2) or completely independent (Example 6.3). Example 6.1 shows ‘melodic fragments’ that were formed on the glockenspiel in replace of snare drum.

Example 6.2 Unison feet and hands in Ringer, m. 1.

Example 6.3 Independent feet and hands in Ringer, m. 202.

Just as James Dillon merged contemporary percussion complexity with drum kit techniques, in Ringer Nicole Lizée showed a confluence between various influences, or a ‘fusing of roles’ where ‘groove and melody synthesize and become one’.38 The inclusion of advanced melodic and rhythmic patterns on the glockenspiel emphasized the performance traditions of a classical percussionist. Typically, such player would have the most experience navigating this instrument since it has appeared most commonly in symphony orchestra repertoire and contemporary classical ensemble settings. Fused into the framework of the drum kit, the performer must be equally experienced in advanced foot techniques and other common drum kit techniques. The presence of rock icon paradigms such as Steve Gadd’s paradiddle required a deep appreciation and understanding of where the material came from and how it was originally played. Then when recontextualized into the new setting for which Ringer presents, the performance still has feeling and groove.

Conclusion

By studying this broad range of works together, I see consistent elements that are required when approaching the drum kit in contemporary classical composition. These are original thought, meaningfulness, and the knowledge of history. Of course, placing the drum kit in the context of the concert hall or within a string orchestra is an exciting premise, but without meaningfully connecting purpose with concepts that move drum kit performance to new places musically, technically, and artistically, the result, as discovered by Milhaud, will be ‘frivolous’.

Today, the drum kit has become a more common addition to ensembles such as Bang On A Can, So Percussion, Alarm Will Sound, my own quartet Architek Percussion, and many others who are performing and commissioning works which blur the boundaries between popular and contemporary classical music. Composers of the past few decades have had a greater opportunity through publications, recordings, online tutorials, and performance footage to learn about the rich history of the drum kit. Since I premiered Ringer in 2009, I have collaborated with a multitude of composers interested in writing for the drum kit. These collaborations have resulted in drum kit performances and recordings by such composers as Lukas Ligeti, John Psathas, Vincent Ho, Rand Steiger, Nicole Lizée, Eliot Britton, John Luther Adams, and many others. Performing this music links an individual to iconic players, grooves, and musical styles that should remain at the core of interpretation, appreciation and, ultimately, performance. It celebrates the evolution of the drum kit, the expressive potential that is possible today, and suggests that new ideas are still to come. I currently teach percussion at McGill University and I am seeing a new generation of players versatile in drum kit and classical percussion performance. I am regularly being introduced to players from around the world promoting the growing interest in this repertoire.